Abstract

We review and analyze previous literature on succession in family firms from an entrepreneurial process perspective. Through a three-step cluster analysis of 117 published articles on succession in family firms published between 1974 and 2010, we find several themes within which succession can be understood from an entrepreneurial process perspective where both the entry of new owners and exit of old owners are associated with the pursuit of new business opportunities. We identify gaps within each cluster and develop a set of research questions that may guide future research on succession as an entrepreneurial process. Since succession involves implications for individuals, families and firms, we suggest researchers should adopt a multilevel perspective as they seek answers to these research questions. Our review and analysis also underlines the need to focus on ownership transition rather than only management succession, and the importance of carefully defining both succession and family firm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

While research on entrepreneurship and family firms have explored how individuals start, take over and expand their own firms, we know little about how and why individuals leave their firms to the care of others, and what economic impact this has on entrepreneurs, families and firms (Parker and Van Praag 2012; Ronstadt 1986; Wasserman 2003). DeTienne (2010) claims the entrepreneurial process does not end with new venture creation and that entrepreneurial exits should be acknowledged as a core part of the entrepreneurial process. Similarly, it has been argued that succession in family firms should be considered more from an entrepreneurial process perspective (Habbershon and Pistrui 2002; Nordqvist and Melin 2010). For example, succession can be an important component of both entrepreneurial entry (of new owners) and entrepreneurial exit (of old owners) when the succession (that is, the entry and exit) is associated with the pursuit of new business opportunities. However, the consequences of such a perspective have never been systematically elucidated. In this article we seek to draw out the fruitful consequences of filling this theoretical gap by a closer integration of entrepreneurship and family firm research (Aldrich and Cliff 2003; Kellermanns and Eddleston 2006; Salvato et al. 2010; Uhlaner et al. 2012; Zellweger and Sieger 2012). We present an exhaustive review and discussion of research on family firm succession from an entrepreneurship perspective, proposing a novel view on succession as a potential process of entrepreneurial exit and entry.Footnote 1

From the perspective of entrepreneurship research, owners who want to exit from their business essentially have three broad categories of exits: they can (1) decide to sell their firm (Wennberg et al. 2010), (2) hand over the firm to family members and/or relatives (Sharma et al. 2003a) or (3) decide (or be forced) to close down their firm (Shepherd et al. 2009). The first two choices are related to both entrepreneurial exit and entrepreneurial entry (Ucbasaran et al. 2001). In this case, entry (of one or more individuals) involves taking over an established business by acquiring a firm that someone else is exiting, rather than entering a new market or industry (Lumpkin and Dess 1996). Relatively little attention has been given to the choices of individuals taking over existing businesses, as opposed to starting from scratch (Parker and Van Praag 2012). This scholarly neglect is puzzling, given the empirical evidence documenting that newly started firms in general show low growth and high failure rates (Davidsson et al. 2007; Van Praag and Versloot 2007). Similarly to starting up a venture from scratch, taking over an existing firm and rejuvenating that business is a relevant form of opportunity recognition. In this article, we focus on one particular type of business take-over: family firm succession.

Recent statistics reveal the importance of this type of business take-over. The European Union has estimated that in the up-coming 10 years, one-third of Europe’s private firms will have to transfer ownership either within or outside the current owner family (European Commission 2006a). Thus, up to 690,000 firms, mainly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), providing 2.8 million jobs, will be transferred to new owners every year (European Commission 2006b). In Germany, it is estimated that up to 2014 approximately 100,000 family firms will face a succession issue and that a majority of these will not be able to find a successor within the family (Hauser et al. 2010). Similarly, a Swedish report notes that as many as 60 % of all private firms would need to shift ownership during the next 10 years (NUTEK 2004). In the USA, one survey estimates that within the next 10 years, 40.3 % of family firm owners expect to retire (American Family Business Survey 2007) and another survey that 65 % of 364 interviewed chief executive officers (CEOs) plan to leave the firm within 10 years (Dahl 2005 in DeTienne 2010). In Japan, Kamei and Dana (2012) report that firm succession is a major social challenge, with about 70,000 small businesses running the risk of having to close down each year because of the lack of a successor.

The literature on family firm research outlines a view of succession as a complex process, influenced by personal goals of the owners, family structure, ability and ambitions of potential successors and legal and financial issues (De Massis et al. 2008; Le Breton-Miller et al. 2004; Sharma et al. 2003a). Since the majority of private family firms in many countries are likely to change ownership as the owners approach retirement, there is a need to study the conditions surrounding such transfers of ownership as well as their consequences (Bennedsen et al. 2007; Parker and Van Praag 2012).

Hence, the purpose of this article is to introduce an entrepreneurial process perspective on succession in family firms and outline an agenda for future research in this area. We analyze extant literature on succession in family firms from the perspective that when succession is associated with the pursuit of new business opportunities (DeTienne 2010; Shane and Venkataraman 2000), ownership transition can be an important component of both entrepreneurial entry (of new owners) and entrepreneurial exit (of previous owners). We focus on succession as ownership transition, either within an owner-family—such as from one generation to another—or from an owner-family to a new non-family owner (Bennedsen et al. 2007; Wennberg et al. 2011). While articles included in the review may differ in their definition of a family firm, we see family firms broadly as firms that are owned by two or more family members either in a household (spousal couple) or in a biologically linked family (fathers, mothers and children) living in the same or another household.

We seek to make contributions to the literature on entrepreneurship and family firms. By showing that family firm succession can have components of both entrepreneurial exit of a previous owner(s) and entry of a new owner(s) in the pursuit of new business opportunities (DeTienne 2010; Shane and Venkataraman 2000), we provide a rationale for integrating the fields of entrepreneurship and family firm research (Aldrich and Cliff 2003; Kellermanns and Eddleston 2006; Naldi et al. 2007; Uhlaner et al. 2012). We explore the general issue of the potential benefits of such an approach and outline seven key research questions for future research. The overriding importance of the multi-dimensionality of succession is a guiding insight, allowing us to recognize that a multilevel perspective will allow us to grasp how the succession process and succession-related decisions in family firms involve relationships and interdependencies between individuals, families and firms (House et al. 1995; Hitt et al. 2007; McKenny et al. 2013). Another cardinal insight is the importance of considering the role of contextual factors, such as industry characteristics, national culture and institutional frameworks, for different types of successions and their impact on key entrepreneurial outcomes.

Our review also suggests that models on entrepreneurs’ career dynamics in sociology (Carroll and Mosakowski 1987) and economics (Evans and Leighton 1989) would benefit from incorporating our suggested view into their models. What influences individuals’ occupational choices will be better understood by considering succession as characterized both by entrepreneurial entries and exits in which factors at the individual, family, and firm levels interact. In particular, “process models” of entrepreneurship (e.g. Eckhardt et al. 2006; Van de Ven and Engelman 2004) could advance firm-level research by considering succession as selection events among firms (Carroll 1984) and advance individual-level research by considering succession as explanatory mechanisms by which founders may “cash in” on the fruits of their labor (DeTienne and Cardon 2012). Given these complexities, we underline the importance of precision and explicitness in defining both succession and family firms for the rigor and relevance of future research.

Further, since the tradition of succession research has concentrated on management transitions, we suggest a stronger focus on ownership transitions. For family firms, transfer of ownership and management may go hand in hand (Block et al. 2011), which is why most previous studies do not make a clear distinction between ownership and management succession. However, there are significant reasons to examine ownership transitions more closely since they encompass resource management, governance, risk taking and emotional issues among the involved actors that may play a pivotal role in a succession from an entrepreneurship perspective. Indeed, transitions within a business are not complete until the voting stock is passed down as well (Handler 1990; Wasserman 2003).

Next, we discuss our view of the entrepreneurial process and then describe our review methodology. Thereafter, we move on to delineate the results in relation to our entrepreneurial process perspective, which leads us in the last section to formulate an agenda for future research and seven research questions.

2 The entrepreneurial process

From a Schumpeterian perspective the initial part of the entrepreneurial process is entry into a new market with goods or services, based on new combinations of existing resources (Schumpeter 1934). At the other end of the entrepreneurial process, exit refers to leaving this market (Van Praag 2003). In contrast, Gartner (1988) and Low and MacMillan (1988) claim that entrepreneurship is a process by which new organizations come into existence, meaning that entrepreneurial entry is seen as the act of starting a new organization. One limitation of these dominant views on entrepreneurship as a process of entering and exiting an organization created by an individual entrepreneur is that it neglects the situation where individuals or teams enter into entrepreneurship by taking over an existing organization. Here, family firm research can enrich general entrepreneurship research in that taking over an existing firm can frequently be a path towards entrepreneurship—for non-family as well as for family members (Parker and Van Praag 2012). Entrepreneurship research has outlined theories related to the firm–individual interface (Davidsson 2004; Sarasvathy 2004; Shane 2003) and called for more studies that account for both entrepreneurial processes and outcomes operating at multiple levels of analysis (Davidsson and Wiklund 2001). Research on family firms has something of a natural multilevel focus, given that succession inherently involves individuals and at least one family and one firm (Le Breton-Miller et al. 2004; Sharma et al. 2003b). Combining entrepreneurship and family firm research allows us to bring together the lens of the entrepreneurial process as composed by entry and exit and the multilevel view of individuals, families and firms common in family firm research (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011; McKenny et al. 2013; Ucbasaran et al. 2001).

From an entrepreneurial process perspective, we define succession as a process in which new owners, from within or outside the owner family, enter the business as owners and add new capital and resources that have consequences for firm processes and outcomes such as innovation, entrepreneurial orientation and growth (Bennedsen et al. 2007; Wennberg et al. 2011). Conversely, the family owners exiting a business commonly do so in order to pass on the firm to new owners, harvest the time, effort and resources they have put into the firm (DeTienne 2010) and perhaps focus their entrepreneurial energy in other organizations (Nordqvist and Melin 2010). Divestment of established companies typically provides the sellers with resources they can invest in new business opportunities (Mason and Harrison 2006).

In the case of passing on a family firm within the same family, this act can be seen as a family’s continued commitment to entrepreneurship, representing both an exit of current owners and the entry of the next generation of managers. In the case of selling the firm to an outside party, this represents an entrepreneurial exit where the family harvests the value of their previous efforts (Wennberg et al. 2011).

Thus, our entrepreneurial process perspective sees succession as a potentially important component of both entrepreneurial entry (of new owners) and entrepreneurial exit (of old owners) when the succession (that is, the entry and exit) is associated with the pursuit of new business opportunities. Entrepreneurship is here usefully defined—building on Shane and Venkataraman (2000)—as one or more individuals’ identification and pursuit of opportunities through the creation of a new organization or the takeover of an established organization with entrepreneurial potential (Parker and Van Praag 2012). Thus, given our focus on succession in family firms, the main business opportunity we refer to is the target of the succession, that is, the firm itself. The new owners see the firm as an opportunity for investing resources, and the previous owners see the firm as an opportunity for releasing resources. Both the new and previous owners may use these resources to create new outcomes (e.g. new ventures, growth and innovation), allowing the succession of the family firm as an entrepreneurial entry and exit to produce new value at different levels (i.e. the individual, the family and the firm).

In sum, from entrepreneurship research we take the conceptual pillars of the opportunity– individual–firm interface and the view of entrepreneurship as a process embracing both entry and exit. From family firm research we take the multilevel process approach to succession involving individuals, families, and firms.

3 Methodology

3.1 Article selection and cluster analysis

In order to identify articles published on succession in family firms, we used the 30 management journals listed in Debicki et al. (2009), whose article was based on reviews of entrepreneurship literature (MacMillan 1993; Shane 1997) and family firm literature (Chrisman et al. 2008). We conducted a three-phase examination of published articles in all issues of these 30 journals, using the publishers’ electronic archives. First, we searched for the keywords succession, successor, predecessor and transition in the keywords and abstracts of the papers, which resulted in the identification of 1,068 papers. Initially, we used the keyword succession on the selected list of journals. We carefully read the most cited papers and identified the terms most commonly referred to in articles focusing on the succession process. This search lead us to include the additional search terms successor and predecessor. We also realized that succession is broadly recognized as a process of transfer of resources (Le Breton-Miller et al. 2004). Therefore, we decided to also include transfer as a keyword. Second, we read all abstracts to exclude research focusing on CEO turnover in large publicly listed firms, retaining only those papers examining succession in private family firms. This sharply reduced the sample to 172 papers. We read these papers and organized a table of contents that included research design, sample characteristics and methods of sampling and analysis. Third, we excluded papers with a predominant practice-oriented focus, such as interviews, book reviews and teaching cases. This further narrowed the sample to 125 papers, all published within the past 35 years. Most were published in the Family Business Review (60.8 %), Journal of Small Business Management (9.6 %), Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice (8.8 %), Journal of Business Venturing (6.4 %), International Small Business Journal (6.4 %) and Small Business Economics (3.2 %). The majority were based on empirical research (72.3 %), with a near equal distribution between qualitative (52 %) and quantitative methods (48 %).

We identified within each article the characteristics highlighted by prior research as salient topics of investigation, which will be explained below. Thereafter, we used hierarchical cluster analysis to categorize extant research based on these specified characteristics.Footnote 2 The cluster method used is the average linkage between groups based on Jaccard’s similarity measure for binary data. In categorizing the corpus of these 125 papers, eight were identified as pure literature reviews and excluded, reducing the final sample to 117 papers. The selection of categorical variables in a cluster analysis is always defined by the researcher (Bailey 1975). It can be either inductive, i.e. exploratory by maximizing the number of categorical variables, or deductive, i.e. based on the current theory on the number and relevance of categorical variables. Following Ketchen and Shook (1996) and using a deductive approach, we drew on three conceptual articles identifying succession as a process operating at several level of analysis (Handler and Kram 1988), realized through different phases (Le Breton-Miller et al. 2004), and involving both firm stakeholders and family stakeholders (Sharma 2004) to select our variables. These three articles identify a set of 15 variables:

-

(1)

level of analysis (4 variables, adopted from Handler and Kram 1988);

-

(2)

phase of succession (4 variables, adopted from Le Breton-Miller et al. 2004);

-

(3)

the family or firm members involved (7 variables, adopted from Sharma 2004).

We used these 15 dummy variables to classify papers in the cluster algorithm.Footnote 3 Cluster analysis with binary variables can be used to divide a sample into groups based on each observation’s possession (or lack) of an attribute—in our case whether they are categorized (or not) into any of the 15 categories identified by earlier research under classification rules 1–3 above (Ketchen and Shook 1996). A common problem in cluster analysis is how to deal with outliers. Hair et al. (2010) suggest that standard scores below 4–5 (D2/degrees of freedom) are acceptable values. Our usage of dummy variables minimized this problem, with no computed dissimilarity values exceeding 1.

The cluster analysis resulted in a univocal grouping of the articles based on each article’s combination of dummy variables. Each article can only appear in one cluster, based on the most significant aspects in terms of similarity with the other papers. The analysis resulted in four overarching clusters representing the main areas identified in the literature, according to the variables taken into account. The first cluster, the environmental level, contains papers that look at factors external to the organization that are relevant to succession; this cluster has the largest share of disparate topics (i.e. with the largest distance). The second cluster contains papers attending to firm-level factors relevant for succession. The third and largest cluster of articles refers to studies focusing on the individual and interpersonal levels, respectively. To understand and analyze the contribution of these articles, we used Johnson’s (1967) suggestion to reduce the distance between the clusters by refining these into four “homogeneous groups” within the individual and interpersonal level cluster that focus on the different phases of the succession process: pre-succession, planning succession, managing succession, post succession (Le Breton-Miller et al. 2004). The fifth cluster, denoting multilevel studies, contains papers that investigate relations between one or several focal agents and external contingencies in the succession process. The overall breakdown of our corpus of studies is organized in the following clusters which guide the literature review analysis (in parenthesis, the table presenting all the papers relating to the topic):

-

1.

Environmental studies (Table 1);

-

2.

Firm-level studies (Table 2);

-

3.

Individual/interpersonal studies, divided into:

-

4.

Multilevel studies (Table 7);

-

5.

Reviews (excluded from the cluster analysis) (Table 8).

3.2 Categorization of the literature

Tables 1–8 present the four clusters of studies obtained from the analysis and demonstrate the main topics covered in each.Footnote 4 In these tables, which are organized by cluster, we summarize the core aspects of each of the 117 articles reviewed. Since for space and readability reasons we cannot present a detailed review of all 117 articles, in Sect. 4 we do attend to each of the cluster of papers, drawing on our entrepreneurship perspective. This approach allows us to discuss how viewing succession as part of the entrepreneurial process can shed new light on extant research and provide suggestions about how such a perspective could further research on this issue.

Table 1 contains the cluster of Environmental-level studies which focus on investigating the impact of factors external to the firm, such as financial and legal institutions and national cultures that impact ownership transfers or succession. Table 2 contains Firm-level studies, a cluster primarily focusing on the relationship between the firm-level dimensions and succession—for example the development and transfer of resources such as social capital (Steier 2001) or human capital (Fiegener et al. 1994). Table 7 contains Individual/interpersonal-level studies, which is the largest cluster with nearly 70 % of the studies reviewed. This table is subdivided into four clusters (Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, respectively) that constitute sequential phases in the succession process: pre-succession, succession planning, succession management and post succession. Table 7 contains Multilevel studies, comprising a cluster of papers attending to how forces at different levels might engender resistance to succession. Finally, Table 8 includes residual papers excluded from the cluster analysis.

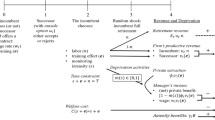

Figure 1 illustrates how the reviewed studies can be related to an entrepreneurial process perspective. The figure highlights how the literature on succession concerns four levels of analysis and four main phases.

An entrepreneur or a team of entrepreneurs—family members or unrelated—participate through a path of entry, firm management and exit. Firms and entrepreneurs have two different lifecycles that often coincide, but may also diverge. This is the exit, when the entrepreneur or the family team decides to sell, pass on or close the business. In the first two scenarios the firm survives and is run by another individual or individuals, who enter the business. The completion of the entrepreneurial process takes the incumbent through the exit process, generating the opportunity for the entrepreneurial entry of a successor. Viewed from this point of view the succession process becomes a part of the entrepreneurial process. The figure also highlights critical issues at the interpersonal, organizational and environmental levels. We now examine each of these critical issues, drawing on the entrepreneurship perspective in order to elaborate upon how this could further theorizing and empirical research on the topic of family firm succession.

4 Discussion and agenda for future research

In this section we discuss the issues of central importance for an understanding of succession as entrepreneurial entry and exit that we have found in the literature review. We also focus on the gaps in research that we view as particularly relevant to address in future research. To help guide future research we formulate a set of key research questions. We believe the pursuit of this research agenda will further the cross-fertilization of theories and concepts between entrepreneurship and family firm research.

4.1 Environmental level: the role of the entrepreneurial context and aggregate effects of ownership transitions

Judged from the articles presented in Table 1, the environmental conditions enabling transitions appear to be an understudied topic. More precisely, our review reveals large areas where ownership transition could benefit from insights from entrepreneurship research in relation to contextual factors. The entrepreneurial context can be thought of as the economic, demographic or institutional factors that shape the phenomenon being investigated. While research on entrepreneurship highlights the programmatic importance of context for entrepreneurial behaviors (Thornton 1999; Zahra 2007), our review indicates that most actual empirical work consists of single-region or single-industry studies.Footnote 5

4.1.1 Industry context

Most of the reviewed studies focus on intra-family succession with hardly any attention being paid to the specific industry context at hand. However, it is well known, for example, that management buy-outs are more common in certain industries than in others (Ucbasaran et al. 2001) and that various types of entry and exit (intra-family, sale to outsiders or management buy-outs) are likely to have different implications for the entrepreneurial performance of family firms (Scholes et al. 2007). Industry structures and demography, such as the age structure of incumbents, may also give rise to new opportunities for individuals interested in entering existing firms facing succession (Shane 2003). Our review did not identify any study that actually investigates and reports how this process varies depending on the industry context.

4.1.2 National context

Our review identified seven cross-country comparative studies (Berenbeim 1990; Chau 1991; Corbetta and Montemerlo 1999; Scholes et al. 2007; Sharma and Rao 2000; Stavrou 1998; Royer et al. 2008) that suggest that national context is important for the evolution of succession, especially in relation to systems of corporate governance (Tylecote and Visintin 2008), firm demographics (Motwani et al. 2006) and cultural–institutional factors (Chau 1991; Kuratko et al. 1993). Yet, most of these studies remain heavily decontextualized since they do not grapple with the impact of specific factors relating to national context in any depth. This indicates that closer attention to the national context and its influence on firm succession could pay off and offer important implications heretofore missed. Entrepreneurial process studies have documented that some cultural traits facilitate the probability of firm formation but do not induce firm growth, and vice versa (Autio et al. 2010). Certain cultures—such as those with strong traditions of long-term orientation and social obligations—may facilitate specific types of succession over others (e.g. Huang 1999; Kuratko et al. 1993). This may also impact firm-level characteristics such as their growth orientation (Davidsson and Wiklund 2001). Further, the type and background of individuals that take over family firms may be driven by external conditions, such as national culture where intra-family succession may be more or less common or legitimate. Institutional aspects at the national level may also impact succession processes. For example, fiscal regimes (Bjuggren and Sund 2002) may influence how transitions occur, which type of transition is chosen, how after a transition the firms develop, as well as which firms are transferred. It has been shown that high taxes on ownership transfers encourage family owners to exit their firms (Henrekson 2005).Footnote 6

4.1.3 Regional context

Understanding the impact of specific regional contexts on economic life represents a promising research area. We need to know more about how a specific social context influences significant decisions regarding entry and exit, how it interacts with the succession process in terms of stakeholders’ involvement, selection of the successor and/or intra- or extra- family succession and how it influences succession outcomes. Such studies could draw on the literature on industrial districts (Becattini 1990; Marshall 1920), innovation milieus (Camagni 1991), regional innovation systems (Braczyk et al. 1998) and clusters (Gordon and McCann 2000; Humphrey and Schmitz 2002). This literature would suggest, for example, that economic factors at the regional level may influence succession at entry and exit since external funding to finance transitions may be lacking in many regions. Demographic aspects may also influence successions since family firms in regions with rapidly aging populations may experience more options for succession processes if the entry of outsiders is considered a viable alternative to intra-family transition.

Research to date is sparse on how variation in the economic, demographic or institutional context may shape the succession process and its implications for entrepreneurial outcomes. Again, succession research could amply the benefit from the growing attention to context in entrepreneurship research (Phan 2004; Zahra 2007). However, the lack of attention to context is most probably attributable to data limitations. Large amounts of time and dedicated resources are needed to design research that can reliably follow individuals and firms over time and compare effects across space in terms of industries, regions, countries or other contextual settings.

While some studies in our review attend to contextual factors for ownership transitions (Bjuggren and Sund 2002; File and Prince 1996; Scholes et al. 2007), they remain rare and fragmented from an entrepreneurial process perspective. Studying succession as both entrepreneurial entry and exit would help to disentangle the different factors associated with ownership transitions in terms of environmental and contextual influences, enabling researchers to pinpoint their impact, for example, on regions, nations or industries with different types of ownership transitions. In sum, this suggests two important research questions regarding how contextual factors shape both the prevalence of ownership transitions as entrepreneurial entry and exit and potential variation in transition outcomes:

RQ1

What are the contextual characteristics that promote variation across nations, regions and industries in terms of likelihood for and type of ownership transitions?

RQ2

How do contextual characteristics affect the entrepreneurial outcomes (e.g. innovation and growth) of different types of ownership transitions?

4.2 Firm level: resources and succession as ownership transitions

The articles presented in Tables 3–6 attend to the firm-level studies dealing with succession. Specifically, this cluster of articles focus on how firm-level resources can be transferred during a succession and how specific governance modes in family firms emerge and change before, during and after a succession. We found that studies dealing with ownership during a succession remain scarce, unlike the bounty of studies dealing with management during a succession. Finally, there is a small but increasingly vibrant body of literature on performance in family versus non-family successions.

4.2.1 Social and human capital

From the entrepreneurial process perspective, the focus on social and human capital during succession is particularly relevant with regard to firm-level factors. For example, family firm owners almost always acquire and retain critical tacit knowledge and are thus potentially better equipped to maintain trust in crucial business relationships with employees, customers and suppliers than outside successors (Scholes et al. 2007). Stavrou (2003) notes that a successor’s intellectual capital in the form of extroversion in relations with the firm’s internal and external stakeholders facilitates the succession process. The multiple case studies by Steier (2001) explain how an owners’ exit puts the firm at risk of losing important social capital associated with the exiting owners—unless the former owners stay on for some time. Focusing on human capital, some studies also describe the critical importance and role of maintaining and developing firm- and industry-specific knowledge (Fiegener et al. 1994; Foster 1995) during succession.

Losing important strategic resources during succession may negatively impact the growth prospects of the firm after succession, since market and innovation capabilities can disappear (Cabrera-Suárez et al. 2001). Alternatively, new owners can often contribute with new resources, such as networks and knowledge, that bring a fresh strategic edge to the business (Nordqvist and Melin 2010). The corpus of research included in our review fails to go beyond a limited insider/outsider view of succession in order to investigate which human, social and/or other resources are important for successors to grow their firms through entrepreneurial activities. It would be valuable to know which specific skills and resources make family successors more or less capable as entrepreneurs than outsiders.

4.2.2 Governance

Entrepreneurship research has focused on how governance structures emerge in new firms as they grow beyond the grip of the founders (Gedajlovic et al. 2004). In contrast, the family firm governance literature in our review (the bottom half of Table 2) has focused on how to handle the family–firm interface (Chua et al. 2003; Corbetta and Montemerlo 1999; Steier et al. 2004). Research on governance changes in relation to succession, as entrepreneurial entry and exit, is valuable for entrepreneurship research seeking to develop a more general model of the individual–firm interface, especially from an evolutionary (Aldrich and Martinez 2001) or life-cycle perspective (Gedajlovic et al. 2004; Hoy and Verser 1994). In our review we did not find any studies that had investigated how governance changes during the transition from old to new owners impact firm innovativeness and growth.Footnote 7 Given the increasing attention that private equity firms show to medium-sized to large family firms as potential investment targets, a better understanding of the implications for firms formerly owned by a family but which have become units of a larger business groups or under the control of private equity firms is needed (Dawson 2009). Does this governance change only mean a better realization of the growth potential, or do the cultural differences create problems of strategic inertia?

4.2.3 Ownership

Our review shows that most studies focus on management succession, with only 19 % of the studies we surveyed explicitly addressing ownership transition. Moreover, even this essential distinction is normally made ambiguous because authors rarely make a clear distinction between management and ownership succession. Although there is a need for such a differentiation—both empirically and theoretically—we identified only three articles that seek to make this distinction (Churchill and Hatten 1997; Gersick et al. 1999; Handler 1994). Generally, the problem of succession seems to be routinely discussed at the management level, while the problem of ownership succession is viewed as essentially a residual unimportant legal problem (Bjuggren and Sund 2002; Howorth et al. 2004; McCollom 1992). Since most previous studies have focused on small or medium-sized family firms, authors have assumed that succession of management and ownership go hand in hand. The co-occurrence of ownership and management succession is a topic that requires more attention in order to provide a better understanding of the complexity of the succession process from an entrepreneurial process perspective. While studies at the family level could generate insights into how family relations affect ownership succession (Dunn 1999; Kaslow 1998) and subsequent performance (e.g. growth, innovation, etc.), there is an absence of research on ownership transitions examining various issues, such as how the potential for entrepreneurial orientation is affected by different types of successions. Further research in this area would be valuable for both theory development and practice (Habbershon and Pistrui 2002; Zellweger and Sieger 2012).

4.2.4 Performance in family versus non-family successions

The literature review also suggests that very few studies have investigated the impact of family versus non-family succession on firm performance. How a firm is affected if a family member takes over ownership—compared to whether an outsider steps in—should be an integral aspect of studies aiming to explore the nature of corporate entrepreneurship in family firms (Kellermanns and Eddleston 2006; Zahra et al. 2004). Recent evidence suggests that outside successors are often advantageous for firm profitability (Bennedsen et al. 2007; Cucculelli and Micucci 2008, Wennberg et al. 2011).

Researchers are faced with many hard methodological challenges in order to effectively isolate the impact of family versus outsider exits and entries on outcomes at the firm level. Block et al. (2011) argue that the strong correlation between family ownership and family management in most family firms might imply that conventional statistical methods and regression analyses are inappropriate. Hence, there is a need for more knowledge on the performance effects of different types of ownership transitions within and outside the family. The premise that family firms most often take a long-term view of firm development (Lumpkin et al. 2010; Zellweger and Sieger 2012) could have implications for the research designs used to investigate the performance effects of firm succession. Performance outcomes measured with parameters too close to the exit and entry point means that no long-term view is taken into account. This discussion indicates a need for empirical research on the process of succession related to corporate entrepreneurship, which we summarize in two research questions:

RQ3

What are the long-term entrepreneurial implications (e.g. survival, growth and innovation) for a firm if there is (1) a transition of ownership within the family or (2) a transition of ownership outside the family?

RQ4

How do resources and competencies brought to the firm by different types of new owners (i.e. family or non-family) affect the firms’ entrepreneurial orientation?

4.3 Individual/interpersonal level: factors influencing entry/exit decisions and their consequences

Tables 3–6 is the largest cluster in our literature review, containing Individual/interpersonal level studies. It is therefore subdivided into four clusters (Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, respectively) that refer to sequential phases in the succession process: pre-succession, planning succession, managing succession and post succession.

4.3.1 Pre-succession

Table 3 summarizes studies that focus on issues which precede succession, such as the willingness and attitudes of family members to taking over a firm. These studies explore emotions, intentions (Birley 1986; Stavrou 1998) and opinions (Birley 2002; Shepherd and Zacharakis 2000) of next-generation family members towards the firm. While these studies reveal reasons explaining why the next generations of family members are positive or negative towards entering the firm, they neglect their intentions for future involvement in the firm. Thus, little is known about the entrepreneurial attitudes of the family members willing to take over the firm, or whether these individuals may prefer to start their own firm.

The studies of the pre-planning phase in Table 3 have also investigated the resources and actions of former owners that may facilitate succession, as well as the role of incumbents, emphasizing their ability to “let go” and leave control to their successor (Cadieux 2007; Hoang and Gimeno 2010). For example, Cabrera-Suárez et al. (2001) discuss the importance of the successor’s ability to acquire the key knowledge and skills of their predecessor in order to maintain and improve organizational performance, and Chrisman et al. (1998) suggest that successor integrity and commitment are considered imperative for pre-succession, while successors’ birth order and gender are of less importance. Another study focusing on succession in family firms run by women highlights the importance of the quality of communication and interpersonal trust within the family for an effective succession (Cadieux et al. 2002). In sum, these studies underscore the importance of understanding the motivations of potential successors, alternatives to intra-family succession and sociological factors that lead family firms to initiate succession.

Published studies on pre-succession related to individuals within a family firm and their relationships bear an intriguing resemblance to research on nascent entrepreneurship. Individual characteristics of firm founders (or successors), such as gender, knowledge and skills, are intimately related both to the chance of successful firm founding or succession (Carter et al. 2003) and the interpersonal relationships between a focal individual and people in their family and social network (Ruef et al. 2003). Research on the pre-succession phase of succession in family firms can benefit from the use of theoretical frameworks on entrepreneurial processes related to nascent entrepreneurship, such as the value of social networks, psychological self-efficacy, goal-setting or opportunity recognition and exploitation. By expanding their conceptual toolbox researchers could make valuable contributions to general entrepreneurship research as well as family firm research.

4.3.2 Planning succession

Our review indicates that extant literature on succession planning rarely takes into account an entrepreneurship perspective. For example, no attention has been given to how formal succession planning could include a systematic analysis of the entrepreneurial opportunities available for the next owner, to which extent these opportunities are more or less feasible to exploit or whether the new owners are from the owning family or from outside the owning family. Within the field of entrepreneurship research, the value of preparing formal business plans has been long debated, and there are arguments both for (Delmar and Shane 2003) and against (Honig and Karlsson 2004) such activities. Studies on how succession planning in family firms is related to key entrepreneurial processes and outcomes could provide interesting input to this debate from a fresh multilevel perspective.

Our review reveals that some studies on succession planning stress the importance of the exiting party granting autonomy and support to the next generation taking over the firm (e.g. Goldberg and Woolridge 1993; Sharma et al. 2003b). Entrepreneurship research has shown that organizational autonomy and support are key to an effective pursuit of opportunities (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Zahra and Sharma 2004). Thus, it is likely that autonomy for the new owners will increase their ability to be proactive and innovative in developing the firm they enter.

4.3.3 Managing the succession

Studies that look at the role of family relations in managing succession could contribute to a better understanding of the role of emotional processes, such as perceived fairness among potential successors and an incumbent’s fear of losing their business (Shepherd et al. 2009). It is only recently that the emotional side of entrepreneurship has attracted the systematic interest of researchers. If managing succession is about managing emotions (Dunn 1999; Sharma 2004), then studying family firms in transition should provide entrepreneurship researchers with ample opportunities to investigate how emotions among old and new owners play a role in the entrepreneurial process and impact key outcomes.

The inclusion of the role that spouses, siblings and children have in the succession process speaks to the importance of viewing succession as involving a team of individuals—rather than the dyad of an incumbent and a successor (Sharma et al. 2003a). Paying systematic attention to such inter-generational teams based on family ties provides opportunities for researchers interested in social psychological dynamics in entrepreneurial teams.

Further, the notion of co-habitation as a period where the incumbent and the successor work together to facilitate the transition suggests the value of recognizing that the entrepreneurial process is something more than a progression through distinct and sequential phases (first an exit and then an entry). Rather succession consists of a more continuous process of socialization during which both the formal ownership and knowledge, along with other entrepreneurial capabilities, such as social networking, are transitioned successively from the previous to the new owners (Steier 2001).

4.3.4 Post-succession

Our critical reading of the literature indicates researchers could take a more explicit entrepreneurship perspective on post-succession in family firms by comparing performance consequences, such as firm growth, innovation and survival, in relation to different types of succession. With reference to entrepreneurial entry and exit, it would be relevant to learn more about what happens to the innovation capabilities and growth trajectories of firms that are passed on within the family and specifically in comparison to firms sold to new non-family owners and firms acquired by other companies. On one hand, it may be expected that new outside owners bring in new resources and capabilities not available within the family and thus inject new entrepreneurial energies to the firm. On the other hand, researchers have observed potential sources that weigh to the comparative advantage of family firms (Carney 2005; Sirmon and Hitt 2003), arguing that many business families over time create unique and rare resources difficult for competitors to imitate. Such resources may be lost if the family leaves the business, with negative implications for the innovative capabilities and growth potential of post-succession firms (Miller et al. 2003).

4.3.5 Family factors

Previous theoretical and exploratory research has examined the role of individuals’ attitudes to and experience of the different phases of succession and the choice between family and non-family ownership transition. However, there is a dearth of theory-testing and of empirical research that investigates the role of family factors and relations on entry and exit decisions (Churchill and Hatten 1997; Vera and Dean 2005), indicating a gap in the literature in relation to the impact of family factors on succession seen as an entrepreneurial process of entry and exit. Entrepreneurship literature shows a mutual influence between family members in the development of both human and social capital. Family structure, parental background and spousal characteristics appear to be significant in relation to an individual’s entrepreneurial behavior (Gartner 1985; Krueger 1993; Schiller and Crewson 1997; Van Praag and Cramer 2001). Scholars can build on this research by focusing on how and why some individuals choose to exit while others take over a family firm, as well as the entrepreneurial consequences of this choice for the firm.

Birth order is one topic that should be more closely examined. Some have argued that most entrepreneurs are first-born children (Robinson and Hunt 1992): a study by Sulloway (1996) found that later-born siblings are more likely to engage in innovation and creative breakthroughs than first-born siblings. Another topic relates to how family relations and conflicts influence the succession decision and how the firm develops in the aftermath of succession (Kellermanns and Eddleston 2004). Family business research often brings up the causes, effects and role of conflicts in family businesses, as well as how they are managed. During the process of succession, such conflicts can play a crucial role (De Massis et al. 2008). While it is claimed that relationship conflicts are detrimental to the entrepreneurial and creative processes, it has been frequently noted that task and cognitive conflicts have in fact positive effects (Jehn 1995, 1997). Consequently, from an entrepreneurial process perspective, it should be particularly interesting to investigate the contribution of different types of conflict in the family’s or individuals’ decision to either enter a new or exit a business, as well as the entrepreneurial implications of this decision.

Aldrich and Cliff (2003) introduced a family embeddedness perspective on entrepreneurship to explain how the discovery and exploitation of opportunities are linked to family structure and relationships. However, studies investigating the role of family embeddedness on entrepreneurial activities’ remain scarce (Cruz et al. 2012). The notion that family structure and relations impact an individual’s ability to discover and exploit opportunities could be used to study how a variety of embeddedness-related factors—such as divorces, number and gender of potential heirs, number of family members and generations involved in the business—influence choices associated with succession as entry and exit. Linked to succession in family firms, the family embeddedness perspective can be used to study how family factors influence both how and the extent to which exiting and entering owners pursue business opportunities post-succession. Further, the ability to draw on the family’s social network, the possible increase (or decrease) in self-efficacy in relation to the family’s prior involvement in a business and the family’s influence on the opportunity recognition and exploitation process are all interesting areas for future investigation (Aldrich and Cliff 2003; Yan and Aldrich 2012). This points to a need for studies that address the following research questions:

RQ5a

How do family structure and relations influence how and whether family members choose to exit the firm, through a transition to family member(s) or to non-family member(s)?

RQ5b

How do family structure and relations influence how and whether family members choose to enter the family firm or select another career path?

RQ6a

How do family structure and relations influence how and the extent to which exiting family members pursue new entrepreneurial opportunities post-succession?

RQ6b

How do family structure and relations influence how and the extent to which entering family members pursue new entrepreneurial opportunities post-succession?

4.4 The importance of multilevel studies and the definitions of succession and family firm

4.4.1 Multilevel studies

All but one (Davis and Harveston 1998) of the reviewed multilevel studies are conceptual (see Table 8). The articles focus mainly on the relations between different contingencies and the individuals involved in the succession process, suggesting, for example, that a potential interplay between a family firm’s generational stage and the current owner’s characteristics has an impact on the likelihood of engaging in succession planning (e.g. Yan and Sorenson 2006). The small number of studies in this cluster attests to the value of drawing on the research on the entrepreneurial process which has conceptualized firm entry and exit as following a multi-stage selection process. These studies operate concomitantly at several levels of analysis, including the individual, firm, national or social group (Autio et al. 2010; Eckhardt et al. 2006).

Empirical studies of such processes have heretofore concentrated on selection events in terms of their effect on start-up attempts versus realized firms (Delmar and Shane 2003), or the choice to seek versus be granted external funding (Eckhardt et al. 2006). It is noteworthy that the question of succession has not yet been addressed in this research stream. Previous studies on multilevel issues in family firm succession provide theoretical and methodological motivations for empirically scrutinizing the proposed models, including variables from multiple levels of analysis, and theorizing on the multilevel influences in analyses of firm succession on entrepreneurial outcomes.

4.4.2 Defining succession

The large volume of studies on succession would suggest that transitions or successions in family firms are very common phenomena. However, in most countries there is a need for more knowledge about how common ownership transitions and succession actually are as active entrepreneurial choices, compared with other types of firm entry and exit. For example, a recent study found that compared to outside or inside transfers, firm liquidation is a frequent exit route (Wennberg et al. 2010). Since privately held family firms in many countries are likely to shift ownership as owners approach retirement, there is a rather obvious need for studies looking closely at the conditions under which firms might be transferred to new ownership rather than being liquidated.

Following the notion that succession decisions, like other entrepreneurial choices, are embedded in family relationships (Aldrich and Cliff 2003), empirical research would benefit from a clear definition of succession. For example, it would be invaluable to know whether ownership is based primarily on a nuclear family and the immediate extended family, or whether a broader definition must be used to capture what really goes on. While narrower definitions exclude some older family firms where ownership has become more “diluted,” such definitions are advantageous in that they carry strong internal validity. Their greatest benefit is that they would allow scholars to sample firms where intergenerational transfer has not taken place. This is something that should be done, as inferences from “famous” examples of successful firms that have existed over several generations can easily lead to sample selection bias and erroneous conclusions regarding general patterns of intergenerational transfers (Sharma et al. 2003b).

4.4.3 Defining the family

Definitions are also important for entrepreneurship research, which could integrate succession and ownership transition in their models to reach a fuller understanding of the choices and constraints available for entrepreneurs seeking to start, enter or leave a firm (Parker and Van Praag 2012; Ucbasaran et al. 2001). To date, neither research on career dynamics (Carroll and Mosakowski 1987) nor theories of entrepreneurial entry and exit as occupational choice (Evans and Leighton 1989) have considered how explanations at the individual, family and firm levels interact to explain firm entries and exits. Our review indicates that these processes depend on individual entrepreneurs and their family members, the human capital and skills of family members and the characteristics of the firms they own and manage. Here, the multilevel perspective of family firm research may be particularly fruitful (McKenny et al. forthcoming). Such a perspective is also increasingly common in the wider management literature (Hitt et al. 2007; House et al. 1995).

A conservative definition of the family firm based on, for example, the nuclear family and majority ownership provides a possibility to bridge the theoretical gaps between entrepreneurship theory, occupational choice theory and family firm research. Bringing family-level influences into entrepreneurship and occupational choice theory and focusing more on the individual owner in family firm research allow for more contextualized explanations of individual behaviors related to entrepreneurial entry and exit (Zahra 2007). While occupational choice theory has been used in both studies of entrepreneurial entry and exit (Evans and Leighton 1989; Van Praag 2003), our review leads us to suggest a research question that occupational choice theory has yet to address:

RQ7

How do individuals’ family structure and their experience from growing up in a family business influence their likelihood of entry into entrepreneurship?

5 Conclusions

In this article, we examine the research on succession in family firms from the perspective of succession as a process of entrepreneurial entry and exit. Our review of this extensive body of literature shows that most prior research consists of conceptual papers, descriptive investigations and micro studies of firm succession based on small samples or a few illustrative cases. We found that very few articles integrate findings or frameworks from entrepreneurship process research with the issue of ownership transition and succession and that no previous study views succession explicitly as a process of entrepreneurial entry and exit. This dual critique points to abundant opportunities for researchers on succession in family firms who can begin to utilize the theoretical frameworks and empirical findings from entrepreneurial processes studies discussed in this article (e.g. DeTienne 2010; Eckhardt et al. 2006; Shane and Venkataraman 2000; Van de Ven and Engelman 2004). Likewise, researchers of entrepreneurial entry and exit could benefit from including the phenomenon of family firm succession and ownership transitions in their studies.

By showing that succession in family firms can relate to both the entrepreneurial exit of a previous owner(s) and the entry of a new owner(s) in the pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities, this article presents a new approach to combining entrepreneurship and family firm research (Aldrich and Cliff 2003; Kellermanns and Eddleston 2006; Naldi et al. 2007; Salvato et al. 2010; Uhlaner et al. 2012), which in turn offers the possibility of a richer understanding of succession and entrepreneurship in family firms. We present seven broad research questions that can help guide future research and conclude that since the succession process and associated decisions in family firms involve relationships between individuals, families and their firms, theoretical and empirical research in this area should strive to utilize a multilevel perspective (Hitt et al. 2007; House et al. 1995).

While existing succession research has concentrated almost exclusively on management succession, an emphasis on ownership transitions is natural when succession is viewed from an entrepreneurial process perspective. Our review indicates that most published studies fail to make a distinction between ownership and management succession in family firms—most likely by assuming that the transfer of ownership and management go hand in hand. We see many reasons to examine ownership transitions more closely—particularly regarding issues related to resource management, governance, risk-taking, emotions, family structure and relations and autonomy. Researchers need to bear in mind that transitions and successions of businesses are not complete until the voting stock has passed to new hands (DeTienne 2010; Handler 1990; Wasserman 2003).

Our review also suggests that models of the career dynamics of entrepreneurs (Carroll and Mosakowski 1987) and entrepreneurship as an occupational choice (Evans and Leighton 1989) could be developed to link to succession in family firms, as both entrepreneurial entries and exits where factors at the individual, family, and firm levels interact. Almost all models to date in these specific areas tend to have a single-level focus on individual attributes. Process models of entrepreneurship (Eckhardt et al. 2006; Van de Ven and Engelman 2004) can be used to advance firm-level research by considering succession as an important selection event among firms (Carroll 1984), as well as individual-level research by viewing succession as an explanatory mechanism through which founders “cash in” on the fruits of their labor (DeTienne and Cardon 2012).

While focusing on the dynamics associated with firm entry and exit, entrepreneurship researchers have often ignored ownership transition in their agenda—or collapsed it as a sub-set in models of firm entry and exit (Van Praag 2003; Wennberg et al. 2010). Researchers in family business and entrepreneurship would benefit theoretically and empirically from a more deliberate integration of insights from each perspective. Such unification of inquiries could significantly improve the fundamental understanding of the predictors, processes and implications of ownership transition and succession.

Empirically, the entrepreneurial process perspective on succession in family firms that we have argued for in this article calls for research designs that follow individuals, families and firms over time. Most studies of entrepreneurship and family firms are still based on cross-sectional studies. Process studies normally focus exclusively on a single level of analysis, eliminating opportunities for understanding how factors at one level of analysis are causally related to the entrepreneurial processes and outcomes at another level. We believe it is high time for future authors to pursue research that integrates core areas of entrepreneurship and family business. This unification will generate both research which simultaneously advances conceptual and methodological rigor and more vibrant insights for both theory and practice.

Notes

We use the phrase potential process of entrepreneurial exit and entry because of the basic truisms that not all startups are entrepreneurial (e.g. Shane 2003) and all successions are not entrepreneurial. We are interested in the general preconditions for entrepreneurship, such as entry, growth and harvest (exit) that can be related to ownership succession and transition.

Cluster analysis consists of multivariate techniques whose primary purpose is to divide a set of objects into groups, based on the similarity of the objects for a set of specified characteristics.

The variables related to level of analysis are individual, inter-personal/group, organizational and environmental; those related to phase of succession are general topics, planning succession, managing succession and post-succession; those related to the family- or firm members involved are incumbent/founder, successor, parent, offspring, manager/employee, shareholder and board of directors.

Almost 50 % of the empirical studies in our review concern the USA, while 10% focus on Canada or the UK.

The fact that we found no studies on the impact of governance change on innovativeness and growth may be because of our choice of search words. Had we included search words such as “business transfers,” “M&A” and “strategic renewa,” it is possible that more studies would have been found. We thank an anonymous reviewer for this point.

References

Asterisk preceding a reference given in the Reference List indicates that the article is one of the 125 articles included in this review

Aldrich, H., & Cliff, J. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(5), 573–596.

Aldrich, H., & Martinez, M. (2001). Many are called, but few are chosen: An evolutionary perspective for the study of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(4), 41–56.

*Ambrose, D. (1983). Transfer of the family-owned business. Journal of Small Business Management, 21(1), 49–56.

American Family Business Survey (2007). Mass Mutual Financial Group, Kennesaw State University. Springfield, MA: Family Firm Institute.

*Aronoff, C. (1998). Megatrends in family business. Family Business Review, 11(3), 181–186.

Autio, E., Pathak, S., & Wennberg, K. (2010). Culture’s consequences for entrepreneurial behaviour. Paper presented at the 2010 Global Entrepreneurship Conference. London

*Ayres, G. (1990). Rough family justice: Equity in family business succession planning. Family Business Review, 3(1), 3–22.

*Ayres, G. (1998). Rough corporate justice. Family Business Review, 11(2), 91–106.

*Bachkaniwala, D., Wright, M., & Ram, M. (2001). Succession in South Asian family businesses in the UK. International Small Business Journal, 19(4), 15.

Bailey, K. D. (1975). Cluster analysis. Sociological Methodology, 1974, 1–54.

*Barach, J., & Ganitsky, J. (1995). Successful succession in family business. Family Business Review, 8(2), 131.

*Barnes, L., & Hershon, S. (1976). Transferring power in the family business. Harvard Business Review, 54(4), 105–114.

Becattini, G. (1990). The Marshallian industrial district as a socio-economic notion. In F. Pyke, G. Becattini, & W. Sengenberger (Eds.), Industrial districts and inter-firm cooperation in Italy (pp. 37–51). Geneva: International Institute for Labour Studies.

Bennedsen, M., Nielsen, K. M., Pérez-González, F., & Wolfenzon, D. (2007). Inside the family firm: The role of families in succession decisions and performance. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2), 647–691.

*Berenbeim, R. (1990). How business families manage the transition from owner to professional management. Family Business Review, 3(1), 69–110.

*Birley, S. (1986). Succession in the family firm: The inheritor’s view. Journal of Small Business Management, 24(3), 36–43.

*Birley, S. (2002). Attitudes of owner-managers’ children towards family and business issues. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(3), 5–20.

*Bjuggren, P.-O., & Sund, L.-G. (2001). Strategic decision making in intergenerational successions of small- and medium-size family-owned businesses. Family Business Review, 14(1), 11–24.

*Bjuggren, P.-O., & Sund, L.-G. (2002). A transition cost rationale for transition of the firm within the family. Small Business Economics, 19(2), 123–133.

*Bjuggren, P.-O., & Sund, L.-G. (2005). Organization of transfers of small and medium-sized enterprises within the family: Tax law considerations. Family Business Review, 18, 305–319.

Block, J. H., Jaskiewicz, P., & Miller, D. (2011). Ownership versus management effects on performance in family and founder companies: A Bayesian reconciliation. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 2(4), 232–245.

Braczyk, H.-J., Cooke, P., & Heidenreich, M. (1998). Regional innovation systems. London: Routledge.

*Brenes, E., Madrigal, K., & Molina-Navarro, G. (2006). Family business structure and succession: Critical topics in Latin American experience. Journal of Business Research, 59, 372–374.

*Brockhaus, Sr, R. (2004). Family business succession: Suggestions for future research. Family Business Review, 17(2), 165–177.

*Brown, F. H. (1993). Loss and continuity in the family firm. Family Business Review, 6(2), 111–130.

*Brown, R. B., & Coverley, R. (1999). Succession planning in family businesses: A study from East Anglia, UK. Journal of Small Business Management, 37(1), 93–98.

*Bruce, D., & Picard, D. (2006). Making succession a success: Perspectives from Canadian small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(2), 306–309.

*Brun de Pontet, S., Wrosch, C., & Gagne, M. (2007). An exploration of the generational differences in levels of control held among family businesses approaching succession. Family Business Review, 20(4), 337–354.

*Cabrera-Suárez, K. (2005). Leadership transfer and the successor’s development in the family firm. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(1), 71–96.

*Cabrera-Suárez, K., De Saa-Perez, P., & Garcia-Almeida, D. (2001). The succession process from a resource-and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 14(1), 37–46.

*Cadieux, L. (2007). Succession in small and medium-sized family businesses: Toward a typology of predecessor roles during and after instatement of the successor. Family Business Review, 20(2), 95–109.

*Cadieux, L., Lorrain, J., & Hugron, P. (2002). Succession in women-owned family businesses: A case study. Family Business Review, 15(1), 17–30.

Camagni, R. (1991). Local ‘milieu’, uncertainty and innovation networks: Towards a new dynamic theory of economic space. In R. Camagni (Ed.), Innovation networks: Spatial perspectives (pp. 121–143). London: Belhaven.

Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 249–265.

Carroll, G. (1984). Dynamics of publisher succession in newspaper organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29(1), 93–113.

Carroll, G., & Mosakowski, E. (1987). The career dynamics of self-employment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32(4), 570–589.

Carter, N., Gartner, W., Shaver, K., & Gatewood, E. (2003). The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 13–39.

*Cater, J., & Justis, R. (2009). The development of successors from followers to leaders in small family firms: An exploratory study. Family Business Review, 22(2), 109–124.

*Chau, T. (1991). Approaches to succession in East Asian business organizations. Family Business Review, 4(2), 161–179.

*Chittoor, R., & Das, R. (2007). Professionalization of management and succession performance. A vital linkage. Family Business Review, 20(1), 65–79.

*Chrisman, J., Chua, J., & Sharma, P. (1998). Important attributes of successors in family businesses: An exploratory study. Family Business Review, 11(1), 19–34.

Chrisman, J., Chua, J., Kellermanns, F., Matherne, C, I. I. I., & Debicki, B. (2008). Management journals as venues for publication of family business research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(5), 927–934.

*Chua, J., Chrisman, J., & Sharma, P. (2003). Succession and nonsuccession concerns of family firms and agency relationship with nonfamily managers. Family Business Review, 16(2), 89–107.

*Churchill, N., & Hatten, K. (1997). Non-market-based transfers of wealth and power: A research framework for family business. Family Business Review, 10(1), 53–67.

*Clifford, M., Nilakant, V., & Hamilton, R. (1991). Management succession and the stages of small business development. International Small Business Journal, 9(4), 43–55.

*Corbetta, G., & Montemerlo, D. (1999). Ownership, governance, and management issues in small and medium-size family businesses: A comparison of Italy and the United States. Family Business Review, 12(4), 361–374.

*Correll, R. (1989). Facing up to moving forward: A third-generation successor’s reflections. Family Business Review, 2(1), 17–29.

Cruz, C., Justo, R., & De Castro, J. O. (2012). Does family employment enhance MSEs performance?: Integrating socioemotional wealth and family embeddedness perspectives. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(1), 62–76.

Cucculelli, M., & Micucci, G. (2008). Family succession and firm performance: Evidence from Italian family firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14(1), 17–31.

Davidsson, P. (2004). Researching entrepreneurship. New York: Springer.

Davidsson, P., & Wiklund, J. (2001). Levels of analysis in entrepreneurship research: Current research practice and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(4), 81–100.

Davidsson, P., Delmar, F., & Wiklund, J. (2007). Entrepreneurship and the growth of firms. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

*Davis, P., & Harveston, P. (1998). The influence of family on the family business succession process: A multi-generational perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22(3), 31–33.

Dawson, A. (2009). Private equity investment decisions in family firms: The role of human resources and agency costs. Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 189–199.

*De Massis, A., Chua, J., & Chrisman, J. (2008). Factors preventing intra-family succession. Family Business Review, 21(2), 183–199.

Debicki, B., Matherne, C., Kellermanns, F., & Chrisman, J. (2009). Family business research in the new millennium. Family Business Review, 22(2), 151–166.

Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2003). Does business planning facilitate the development of new ventures? Strategic Management Journal, 24(12), 1165–1185.

*DeNoble, A., Ehrlich, S., & Singh, G. (2007). Toward the development of a family business self-efficacy scale: A resource-based perspective. Family Business Review, 20(2), 127–140.

DeTienne, D. R. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 203–215.

DeTienne, D. R., & Cardon, M. (2012). Impact of founder experience on exit intentions. Small Business Economics, 38(4), 351–374.

*Dimsdale, P. (1974). Management succession. Facing the future. Journal of Small Business Management, 12(4), 42–46.

*Diwisch, D., Voithofer, P., & Weiss, C. (2009). Succession and firm growth: Results from a non-parametric matching approach. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 45–56.

*Dumas, C., Dupuis, J., Richer, F., & St-Cyr, L. (1995). Factors that influence the next generation’s decision to take over the family farm. Family Business Review, 8(2), 99–120.

*Dunn, B. (1999). The family factor: The impact of family relationship dynamics on business-owning families during transitions. Family Business Review, 12(1), 41–57.

*Dyck, B., Mauws, M., Starke, F., & Mischke, G. (2002). Passing the baton: The importance of sequence, timing, technique and communication in executive succession. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(2), 143–162.

*Dyer W., Jr, & Handler, W. (1994). Entrepreneurship and Family Business: Exploring the Connections. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19(1), 71–83.

Eckhardt, J., Shane, S., & Delmar, F. (2006). Multistage selection and the funding of new ventures. Management Science, 52(2), 220–232.

European Commission (2006a). Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Implementing the Lisbon Community Programme for Growth and Jobs—Transfer of business, continuity through a new beginning. COM(2006) 33 Final, Brussels.

European Commission (2006b). Markets for business transfers. Fostering transparent marketplaces for the transfer of businesses in Europe—report of the expert group. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Brussels.

Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1989). Some empirical aspects of entrepreneurship. The American Economic Review, 79(3), 519–535.

*Fahed-Sreih, J., & Djoundourian, S. (2006). Determinants of longevity and success in Lebanese family businesses: An exploratory study. Family Business Review, 19(3), 225–234.

*Fiegener, M., Brown, B. M., Prince, R. A., & File, K. M. (1994). A comparison of successor development in family and nonfamily businesses. Family Business Review, 7(4), 313–329.

*Fiegener, M., Brown, B. M., Prince, R. A., & File, K. M. (1996). Passing on strategic vision: Favored modes of successor preparation by CEOs of family and nonfamily firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 34(3), 15–26.

*File, K. M., & Prince, R. A. (1996). Attributions for family business failure: The heir’s perspective. Family Business Review, 9(2), 171–184.

*Foster, A. (1995). Developing leadership in the successor generation. Family Business Review, 8(3), 201–209.

*Fox, M., Nilakant, V., & Hamilton, R. (1996). Managing succession in family-owned businesses. International Small Business Journal, 15(1), 15–25.

*Galiano, A., & Vinturella, J. (1995). Implications of gender bias in the family business. Family Business Review, 8(3), 177–188.

*Garcia-Álvarez, E., López-Sintas, J., & Gonzalvo, P. (2002). Socialization patterns of successors in first-to second-generation family businesses. Family Business Review, 15(3), 189–203.

Gartner, W. B. (1985). A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation. Academy of Management Review, 10, 696–706.

Gartner, W. B. (1988). Who is an entrepreneur? Is the wrong question. American Journal of Small Business, 12(4), 11–32.

Gedajlovic, E., Lubatkin, M. H., & Schulze, W. S. (2004). Crossing the threshold from founder management to professional management: A governance perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 41(5), 899–912.

*Gersick, K., Lansberg, I., Desjardins, M., & Dunn, B. (1999). Stages and transitions: Managing change in the family business. Family Business Review, 12(4), 287–297.

*Goldberg, S. (1996). Research note: Effective successors in family-owned businesses: Significant elements. Family Business Review, 9(2), 185–197.

*Goldberg, S., & Wooldridge, B. (1993). Self-confidence and managerial autonomy: Successor characteristics critical to succession in family firms. Family Business Review, 6(1), 55–73.

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & De Castro, J. (2011). The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Academy of Management Annals, 5, 653–707.

Gordon, I. R., & McCann, P. (2000). Industrial clusters: Complexes, agglomeration and/or social networks? Urban Studies, 37(3), 513–532.

Habbershon, T., & Pistrui, J. (2002). Enterprising families domain: Family-influenced ownership groups in pursuit of transgenerational wealth. Family Business Review, 15(3), 223.

Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

*Handler, W. (1990). Succession in family firms: A mutual role adjustment between entrepreneur and next-generation family members. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 15, 37–51.

*Handler, W. (1991). Key interpersonal relationships of next-generation family members in family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 29(3), 21–32.

*Handler, W. (1992). The succession experience of the next generation. Family Business Review, 5(3), 283–307.

*Handler, W. (1994). Succession in family business: A review of the research. Family Business Review, 7(2), 133–157.

*Handler, W., & Kram, K. (1988). Succession in family firms: The problem of resistance. Family Business Review, 1(4), 361–381.