Abstract

We posit that entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship are distinct entrepreneurial behaviors that differ in terms of their salient outcomes for the individual. Since individuals are likely to differ in their attitudes to these salient outcomes, and in their entrepreneurial self-efficacy, we hypothesize that a different strength of intention for entrepreneurship versus intrapreneurship will be due to individual differences in self-efficacy and in their attitudes to the outcomes from entrepreneurial, as compared to intrapreneurial, behavior. We find that while self-efficacy is significantly related to both entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions, attitudes to income, ownership, and autonomy relate only to entrepreneurial intentions, while attitude to risk relates only to intrapreneurial intentions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The literature on entrepreneurial intentions has focused almost exclusively on the individual’s intention to become a self-employed owner-manager of a new business venture (see, for example, Bird 1988, 1992; Krueger 1993; Krueger and Carsrud 1993; Krueger and Brazeal 1994; Gupta et al. 2009; Linan and Chen 2009; Thompson 2009; Fitzsimmons and Douglas 2011). Yet entrepreneurial behavior is also found among employees within organisations, where it is known as intrapreneurship (Pinchot 1985) and contributes to corporate entrepreneurship at the firm level (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Morris and Kuratko 2002; Davidsson 2006). Since both individual and corporate entrepreneurship are desirable for economic growth and global competitiveness, it is important to understand both types of entrepreneurship behavior (Burgelman 1983; Honig 2001; Parker 2011). Burgelman (1983) examined the process of internal corporate venturing conducted by intrapreneurs; Honig (2001) considered the different learning strategies of entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs; and Parker (2011) examined factors promoting entrepreneurship rather than intrapreneurship, but to date little theoretical or empirical research has considered the cognitive antecedents of the individual’s intention to become an intrapreneur as compared to the cognitive antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions, an exception being a limited exercise by Monsen et al. (2010).

We know that entrepreneurial behavior takes place at the nexus of the individual and the opportunity, and that there is heterogeneity on both sides of this nexus (Shane and Venkataraman 2000). Heterogeneity among individuals has been well studied in the context of entrepreneurial intentions, with differences in attitudes to outcomes associated with entrepreneurial behavior and the individual’s entrepreneurial self efficacy being acknowledged as the main drivers of differences in entrepreneurial intentions (see, for example, Krueger and Brazeal 1994; Krueger et al. 2000). While some researchers (e.g., Samuelsson and Davidsson 2009) have considered heterogeneity on the opportunity side, the literature has almost totally neglected the individual’s formation of the intention to behave entrepreneurially as an employee within an existing firm. Prior research generally assumes that entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs are essentially similar in terms of their human capital (Parker 2011, p. 27; Menzel et al. 2007, p. 734), and that their risk attitudes and cognitive styles are also rather similar (Hisrich 1990; Hitt et al. 2002). As Honig (2001, p. 22) states, “establishing differences between nascent entrepreneurs and nascent intrapreneurs is… of considerable theoretical and empirical interest”. Previous studies have also examined the individual’s choice between self-employment and employment (Evans and Leighton 1989; Katz 1992; Kolvereid 1996, 1997; Reynolds 1997; Shaver et al. 2001; Douglas and Shepherd 2002; Carter et al. 2003). Such studies have generally proceeded on the basis of this simple dichotomy and have failed to recognise the intermediate case where the individual, as an intrapreneur, can behave entrepreneurially as an employee within a corporate context. Shaver et al. (2001) suggest a framework for analyzing the reasons for starting a new business, but do not consider the reasons for undertaking intrapreneurship. Carter et al. (2003) compared the reasons for career choices of nascent entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs, but excluded those who were in the process of starting a new venture in the context of their employer.

While much has been written about how managers might motivate increased intrapreneurial behavior from employees in the corporate context (e.g., Hamel 2000; Morris and Kuratko 2002), little is known about how employers might best select employees who have a propensity for intrapreneurship. Insight into the cognitive and human capital differences of those intending employment as an intrapreneur might facilitate more efficient matching of individuals with corporate employment roles—some of these roles might require intrapreneurial behavior while others are largely administrative with little scope for individual initiative or creativity (Stevenson 1994). Employers seeking intrapreneurial employees need to understand that recruiting individuals with strong intentions for entrepreneurship may not be the best strategy as they may not dwell long in the corporate context before leaving to become self-employed.

Second, policy makers need to understand that a different policy approach may be required to encourage individuals to create new ventures to introduce innovations as distinct from encouraging existing firms to do this. Public policy to nurture and support fledgling firms may be pushing individuals who are better suited to intrapreneurship into entrepreneurial new ventures and thereby contribute to the waste of public resources (Shane 2009), not to mention the personal cost of entrepreneurial failure. Third, entrepreneurship education that is based on the premise of starting one’s own business may be missing the target for many potential intrapreneurs. In encouraging and equipping students to act entrepreneurially, we may be teaching the wrong things, or at best, the right things in the wrong context. Educational institutions that teach entrepreneurship in one subset of courses, while teaching management, marketing, production, and operations, and so forth, in a corporate context, need to understand that potential intrapreneurs may not be best served by either of these polar perspectives.

While others have maintained a clear focus on intentions toward independent entrepreneurship, in this paper we expand on their work by paying attention to both entrepreneurial intentions and intrapreneurial intentions and investigating the differences between these. We argue that entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship offer distinctly different benefit and cost outcomes. Since individuals are likely to differ with respect to their attitudes toward these outcomes, we might expect individuals to form a preference for one over the other based on their personal attitudes towards the salient outcomes and on their perceived entrepreneurial abilities. Accordingly, the first research question addressed in this paper is whether individual entrepreneurship and corporate intrapreneurship are viewed by individuals as separate and distinct entrepreneurial behaviors. The second main research question is whether the antecedents of intrapreneurial intentions are the same as, or are different from, the antecedents for individual entrepreneurial intentions, and we demonstrate empirically that there are important differences.

In the following sections, we address these questions and test empirically a series of hypotheses suggested by the literature and our analysis. We first examine the relevant literature on entrepreneurial intentions and its antecedents. Next follows a section on theory building and hypothesis development. Then, we discuss our sample and research method, followed by details of our analysis and results. The paper ends with discussion of our contributions, limitations, and implications of our results.

2 Prior research on entrepreneurial intentions

Previous research has investigated the economic and psychological motivations of individuals to behave entrepreneurially (Baumol 1990; Evans and Leighton 1989; Katz 1992; Krueger 1993; Krueger and Carsrud 1993; Eisenhauer 1995; Kolvereid 1996, 1997; Douglas and Shepherd 2000; Shaver et al. 2001; Markman et al. 2002; Carter et al. 2003; McMullen and Shepherd 2006). In this study, we focus on the individual’s formation of the intention to behave entrepreneurially as either a self-employed entrepreneur or an employed intrapreneur. Note that the focus of our analysis is at the intentions stage of the entrepreneurial process rather than at the following behavior stage. It nonetheless involves the individual’s expectations about the outcomes that would be experienced at that later stage in the entrepreneurial process. Note also that our analysis is at the individual level, rather than at the firm level—we do not address the collective intentions or actions of intrapreneurs in the process of corporate venturing (see, e.g., Burgelman 1983).

The ‘theory of planned behavior’ argues that behavior is best predicted by intentions toward that behavior. Intentions, in turn, depend on beliefs or attitudes towards the outcomes of that behavior, and in general, the stronger these attitudes, the greater the intention to engage in that particular behavior (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975; Ajzen 1985, 1991). Bird (1988, 1992), Krueger (1993), Boyd and Vozikis (1994), and Bird and Jelinek (1988) argue that preceding the act of entrepreneurial behavior is the formation of the intention to behave entrepreneurially. Krueger (1993), Krueger and Carsrud (1993), Krueger and Brazeal (1994), and Krueger et al. (2000) argue that the formation of entrepreneurial intentions by the individual depends on the perceived desirability and the perceived feasibility of the entrepreneurial behavior. The perceived desirability of an entrepreneurial action depends, in turn, on the individual’s attitudes towards the outcomes of that action (Robinson et al. 1991) in conjunction with the magnitude of those outcomes. Attitudes are feelings that individuals have toward objects or situations that are either positive or negative and which vary in degree from ambivalent to very strong. A strong positive attitude to an outcome implies that the individual expects to gain substantial psychic satisfaction from experiencing that outcome, and this militates in favor of the individual subsequently pursuing that action (Douglas and Shepherd 2000).

The salient outcomes of entrepreneurial behavior have been argued to include income, autonomy, exposure to risk, exposure to work effort, and all other net benefits (Douglas and Shepherd 2000). In this paper, for the purposes of potentially distinguishing different attitudinal antecedents of intrapreneurship, we argue that these are also the salient outcomes associated with behaving intrapreneurially. Also, for the purposes of directly comparing entrepreneurial intentions with intrapreneurial intentions, holding all else equal, we assume that the wealth-creating opportunity is the same for both behavioral alternatives—i.e., it might be exploited either by the individual forming a new business entity (i.e., entrepreneurship) or by the individual working within an existing business firm (i.e., intrapreneurship). The quantum of each of the salient outcomes may be perceived by individuals to be higher or lower when a given opportunity is exploited as an entrepreneur, as compared to exploiting the same opportunity as an intrapreneur.

The salient outcomes, or the ‘payoffs’ to entrepreneurial activity (Baumol, 1990), include both monetary and intrinsic benefits and costs associated with entrepreneurial activity (Wiklund et al. 2003). Eisenhauer (1995) called the intrinsic benefits and costs the ‘working conditions’ associated with entrepreneurship. Douglas and Shepherd (2000) specified the intrinsic costs as those relating to risk taking and providing work effort, and specified the intrinsic benefits as autonomy and all other net perquisites. McClelland (1961) argued that a major intrinsic benefit of entrepreneurial activity relates to a sense of achievement, and several other authors consider a range of intrinsic benefits that are (in prospect) or were (in retrospect) expected to be attained as a result of becoming an entrepreneur (see, for example, Scheinberg and MacMillan 1988; Birley and Westhead 1994; Gatewood et al. 1995; Kolvereid 1996, 1997; Shaver et al. 2001; and Carter et al. 2003). Shaver et al. (2001: 8) mention the “fundamental elements of independence and ownership” as salient outcomes of entrepreneurship, and Fitzsimmons and Douglas (2011) found that attitude to ownership of the firm is a distinctly separate construct to attitude to independence. Wiklund et al. (2003) found separate and significant positive effects for attitude to independence and attitude to control, as well for attitude to income and attitude to employee well-being, as determinants of the growth motivation of small business managers.

Several studies have examined the reasons why individuals choose to pursue entrepreneurial self-employment rather than non-entrepreneurial employment situations (e.g., Scheinberg and MacMillan 1988; Birley and Westhead 1994; Gatewood et al. 1995; Shaver et al. 2001; Carter et al. 2003). Although the descriptors differ across this prior research, the reasons typically given include reference to the outcomes of autonomy/independence, increased income, and the intrinsic benefits of associated with owning one’s own business. These intrinsic benefits might include those relating to the pride of achievement, the possession of discretionary power, and recognition by others that one is a business owner (see, particularly, Shaver et al. 2001; Carter et al. 2003). While these studies do not focus on the individuals’ attitudes to these outcomes of entrepreneurship, it can be inferred that individuals have positive attitudes to these outcomes since they are using them as the justification for their selection of entrepreneurial self-employment.

Douglas and Shepherd (2000) implicitly argue that perceived desirability of a career opportunity is a higher-order construct comprising attitudes to income, autonomy, risk exposure, work effort, and other net perquisites, where no particular attitude is either necessary or sufficient for perceived desirability. Rather, it is the combined impact of these, in conjunction with the salient outcomes of the entrepreneurial opportunity, that determines perceived desirability (i.e., maximal utility) or not. The individual’s attitudes toward the salient outcomes of an entrepreneurial opportunity form the weights attached to the quantum provided of each salient outcome by the entrepreneurial opportunity. The opportunity is perceived to be desirable (utility maximizing) if the weighted sum of the salient outcomes (i.e., the expected utility of the opportunity) exceeds that of all other accessible employment and self-employment opportunities. Our focus in this paper is to ascertain whether some individuals would find the opportunity more desirable when pursued as an entrepreneurial, rather than an intrapreneurial, opportunity, or vice versa, due to different weights they place on the salient outcomes—e.g., if the individual is more or less risk averse—and considering that the two different kinds of opportunity exploitation may be expected to provide more or less of the salient outcomes—e.g., the intrapreneurial exploitation alternative may expose the individual to less risk.

An individual’s self-efficacy has also been argued to be a significant driver of entrepreneurial intentions (Krueger 1993; Krueger and Brazeal 1994; Markman et al. 2002; McMullen and Shepherd 2006). Self-efficacy is the strength of an individual’s belief that they can successfully accomplish a specific task or series of related tasks (Bandura 1977). It is related to self-confidence and individual capabilities, which are dependent on prior experience, vicarious learning, social encouragement, and physiological issues (Bandura 1982). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) relates to the individual’s confidence that they can successfully accomplish tasks associated with individual entrepreneurship, and ESE has been found to be related to the formation of entrepreneurial intentions (Boyd and Vozikis 1994; Chen et al. 1998; De Noble et al. 1999; Markman et al. 2002; McGee et al. 2009). In this study, we ask whether ESE is also related to the intrapreneurial intentions.

Only one study of which we are aware, by Monsen et al. (2010), has investigated the intention to participate in intrapreneurship. These authors found that the prospective willingness to participate in intrapreneurship depends negatively on both the amount of risk exposure and the work effort expected, and positively on the share of profits (or bonus) they expect to receive for successful projects. These results align with the predictions of Douglas and Shepherd (2000) for entrepreneurship motivation, although subsequently those authors found that attitude to work effort was not significantly related to entrepreneurial behavior (Douglas and Shepherd 2002). Parker (2011) hints at the influence of the individual’s cognitions on entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions when he notes that the “independence-seeking (individual) is more likely to engage in (entrepreneurship rather than intrapreneurship)” (Parker 2011, p. 22), and that “one might expect” more risk-averse individuals to be more likely to engage in intrapreneurship (than entrepreneurship), since existing firms might be expected to provide a “forgiving environment within which to try a start-up” (Parker 2011, p. 31).

3 Hypothesis development

We turn now to the development and testing of hypotheses regarding the relationship between attitudes and entrepreneurial self-efficacy and the formation of the intention to become either an entrepreneur or an intrapreneur.Footnote 1 For the purposes of this paper, we define entrepreneurship as the act of starting a new business venture to exploit a new business opportunity. By intrapreneurship, we mean individual entrepreneurial behavior within an employment role in an established organization. Our analysis is at the individual level, whereas ‘corporate entrepreneurship’ is a firm level construct (see, for example, Burgelman 1983; Morris and Kuratko 2002) that occurs due to the collective actions of intrapreneurs within an organisation, and is thus outside the scope of this paper. Measures of corporate entrepreneurship (e.g., Lumpkin and Dess 1996) indicate how organizations act more or less entrepreneurially, but our concern here is with the individual’s formation of the intention to join an organization and to act as an intrapreneur within it.

The first research question is whether entrepreneurship intentions and intrapreneurship intentions should be treated as distinct and separate constructs. We argue that they are because the profiles of the salient outcomes are typically perceived to be substantially different in these alternative modes of exploitation. First, considering income, the individual entrepreneur (as majority owner) will be the residual claimant of the majority of the firm’s profits, whereas the intrapreneur (as an employee, and possibly having a minority ownership share) may be awarded a relatively small portion of the firm’s profits as a performance bonus or dividend, but will expect that most of the profits will accrue to the majority shareholders. Thus, for a given opportunity, the expected income will be substantially greater for the individual if the opportunity is exploited as an entrepreneur as compared to exploiting it as an intrapreneur, other things being equal.

Second, decision-making autonomy for the individual exploiting an opportunity will be substantially greater if the individual were to exploit that opportunity as an entrepreneur rather than as an intrapreneur. As owner-manager of the new venture, the entrepreneur must make all strategic and operational decisions (albeit potentially advised and/or restricted by mentors, investors, bankers, and possibly others), whereas as an intrapreneur, the individual should expect to defer to senior management and/or corporate policies on at least some decisions that would have been made by the individual if he/she were an entrepreneur.

Third, it is argued that ownership of the firm in which one works will confer greater psychic benefits to the individual as an entrepreneur than would non-ownership of a firm to the same person when exploiting the same opportunity as an intrapreneur in an employment position within that firm. Shaver et al. (2001) suggest that ownership is an important driver of entrepreneurial behavior, and Fitzsimmons and Douglas (2011) found empirically that the psychic benefits of business ownership are separate from the psychic benefits of independence, and that these are indeed separate constructs. The expected benefits of business ownership relate to the psychic utility an owner might derive from pride, sense of achievement, power to set strategic direction and tactics, power to hire and fire employees, and so on. Majority ownership may simultaneously expose the individual to psychic costs associated with additional levels of responsibility and stress associated with managing people, making individual decisions, having a wider span of control, and concern for employee well-being (Wiklund et al. 2003). While non-ownership employment situations may also offer pride, prestige, and power, these psychic benefits are likely to be greater in a self-employment majority ownership situation, other things being equal. The psychic costs of the non-owning intrapreneur do not include some that are borne by the owner-manager entrepreneur, but the former is also likely to have lesser authority to control or eliminate irksome working conditions. Thus, we conclude that majority ownership of the firm in which one works will confer greater net psychic benefits than would a non-ownership employment position within the firm, all else being equal.Footnote 2

Fourth, the individual’s exposure to risk will be viewed as greater in the role of entrepreneur as compared to intrapreneur, other things being equal, since the former is the majority owner of the firm that may be bankrupted by undertaking the new venture, while the latter is not. The risk of bankruptcy will be perceived as higher for the entrepreneurial alternative (Stinchcombe 1965; Shepherd et al. 2000) than it would be for the intrapreneurial alternative, since an established firm will have other products or services already generating revenues. The risk of losing one’s job is also likely to be greater for the individual entrepreneur, since the intrapreneur might expect to be re-assigned somewhere else in the organization if the new venture does fail. Within an existing organization, the intrapreneur can expect to seek help from more-senior managers, who might be expected to provide advice and additional resources, if the individual gets into difficulties, which would also cause the individual to perceive intrapreneurship as less risky than entrepreneurship, other things being equal.

Finally, the work effort required is probably perceived to be significantly higher in the entrepreneurship alternative than in the intrapreneurship alternative. Stories abound of entrepreneurs having to work long and hard to keep their new venture alive and to grow in the face of unexpected crises and setbacks (see, e.g., Bird and Jelinek 1988). As an intrapreneur, the individual might expect to seek higher-level approval for the re-assignment of other employees or the recruitment of additional employees to help cope with the workload.

The foregoing analysis outlining the difference in the expected salient outcomes associated with entrepreneurship compared with intrapreneurship therefore suggests the following hypothesis:

H1

Entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship are viewed as distinctly different career alternatives.

Next, we consider the individual’s attitudes to each of the five salient outcomes and note that attitudes are dispositional and likely to be the same across different choice alternatives. Starting with income, we note that the individual’s attitude to income is derived from their desire for goods and services that can be purchased from income. Basic economic theory teaches that the individual’s desire for goods and services is effectively unlimited, and that fulfilment of those desires provides psychic well-being (see, for example, Mansfield 1994: chap. 2). Individuals with stronger desires for goods and services will tend to desire greater incomes, and since both entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship are generally expected to generate higher incomes than ordinary employment, we expect that the formation of both entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions will be positively related to the individual’s attitude to income. We note that Monsen et al. (2010) found that intrapreneurial intentions were positively related to the share of profits or bonus that respondents expected to receive for successful projects. This suggests that the stronger the attitude to income, the more likely individuals are to form the intention to be both an entrepreneur and an intrapreneur. This suggests the following hypotheses:

H2a

The more positive the attitude to income, the more positive will be the entrepreneurial intention;

H2b

The more positive the attitude to income, the more positive will be the intrapreneurial intention.

Next. concerning the individual’s attitude to decision-making autonomy, or independence, we know from ‘self-determination theory’ that the need for autonomy is an innate psychological need (Deci and Ryan 1985, 2000; Gagne and Deci 2005). Prior research in the entrepreneurship domain has indicated that entrepreneurs value independence and decision-making control (e.g., Wiklund et al. 2003), and the individual’s attitude to independence is likely to be positively related to the intention to become an entrepreneur (e.g., Douglas and Shepherd 2002; Shane 2003: 106–108; and Lange 2012), but will this also hold for intrapreneurial intentions? An intrapreneur is likely to be allowed more decision-making independence within the organization than are other employees who are not involved in corporate entrepreneurship projects. Accordingly, individuals are likely to expect greater autonomy in both entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship as compared with ordinary employment, so the more they value decision-making autonomy, the more they are likely to want to become either an entrepreneur or an intrapreneur. This suggests the following hypotheses:

H3a

The more positive the attitude to independence, the strong more positive will be the entrepreneurial intention;

H3b

The more positive the attitude to independence, the more positive will be the intrapreneurial intention.

Now considering the individual’s attitude to the net psychic benefits associated with majority ownership of the firm, we note that, as well as increased decision-making independence, ownership of the firm also serves to satisfy the individual’s need for achievement, power, and recognition. Wiklund et al. (2003) found that the growth motivation of small business owners was positively related to attitude for employee well-being, indicating that ownership of the firm tends to satisfy the entrepreneur’s need to take care of his/her employees. Shaver et al. (2001) argued that independence and ownership are the two main reasons for entrepreneurial behavior, and Fitzsimmons and Douglas (2011) found that entrepreneurial intentions were positively related to the individual’s attitude to majority ownership of the firm, so we expect to find the same here. But we do not expect attitude to majority ownership to be positively related to intrapreneurial intentions—instead, we expect that these variables will be negatively related, since the stronger one’s preference for majority ownership, the less satisfying would be intrapreneurship, other things being equal. Thus, we expect that attitude to majority ownership will be positively related to individual entrepreneurial intentions and negatively related to corporate intrapreneurial intentions, other things being equal, since the individual could be less likely to be able to claim responsibility for firm achievements, would be less likely to be recognized publically for his/her achievements, and would likely have less control of decisions that affect employee well-being. This suggests the following hypotheses:

H4a

The more positive the attitude to majority ownership, the more positive will be the entrepreneurial intention;

H4b

The less positive the attitude to majority ownership, the more positive will be the intrapreneurial intention;

The individual’s attitude to risk has been shown to generate mixed results in the context of entrepreneurial intentions and behaviors. While Douglas and Shepherd (2002) found risk tolerance to be positively related to entrepreneurial behavior, many others have found it to be unrelated to entrepreneurial behaviors (e.g., Brockhaus 1980; Palich and Bagby 1995; Busenitz and Barney 1997). These mixed results indicate that the relationship between attitude to risk and entrepreneurial behavior is more complex. Palich and Bagby (1995) and Busenitz and Barney (1997) argue that risk is often misperceived by nascent entrepreneurs due to overconfidence, the use of heuristics, or optimistic framing of the opportunity (see also Krueger and Dickson 1994; Douglas 2009). At the intentions stage of the entrepreneurial process, we are concerned with the individual’s perception of risk in two alternative modes of opportunity exploitation—one acting as entrepreneur and the other as intrapreneur. Our question here is whether one’s attitude to perceived risk will have a different impact on intentions in the entrepreneurship versus the intrapreneurship mode of exploitation. We note that Fitzsimmons and Douglas (2011) found attitude to risk is unrelated to entrepreneurial intentions, while Monsen et al. (2010) found prospective willingness to participate in intrapreneurship depends negatively on risk exposure. Notwithstanding the prior findings, we expect individuals to be risk averse, and to recognize that entrepreneurship carries more risk than does intrapreneurship, other things being equal. This suggests the following hypotheses:

H5a

The more positive tolerance for risk, the more positive will be the entrepreneurial intention;

H5b

The less positive tolerance for risk, the more positive will be the intrapreneurial intention;

Finally, concerning attitude to work effort, Bird and Jelinek (1988) noted that entrepreneurs often need to work very hard. Douglas and Shepherd (2000) proposed that the individual’s attitude to work effort would be negatively related to entrepreneurial behavior, but their later empirical work failed to find a significant relationship between attitude to work effort and entrepreneurial activity (Douglas and Shepherd 2002). Wiklund et al. (2003) found that attitude to workload was significantly positively related to growth motivation of small business owners in a very large Swedish sample, but this relationship was only significant in one of the three smaller subsamples. Since work effort has physiologically deleterious effects after some point, we assume that individuals generally are averse to greater work effort, other things being equal. Thus, we expect that work-averse individuals will tend to avoid occupations where the work effort demands are heavier, other things being equal. We also expect that an individual contemplating working as either an intrapreneurial employee or as a self-employed entrepreneur would consider the likely work effort requirements of these alternatives in conjunction with the strength of his/her own attitude towards work effort, and we have argued earlier that entrepreneurship is likely to be perceived as requiring greater work effort demands than intrapreneurship. This suggests the following hypotheses:

H6a

The more positive the tolerance for work effort, the more positive will be the entrepreneurial intention;

H6b

The less positive the tolerance for work effort, the more positive will be the intrapreneurial intention.

The impact of entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) on the intention to behave entrepreneurially has been well discussed in the context of individual entrepreneurship (e.g., Chen et al. 1998; De Noble et al. 1999; McGee et al. 2009), but little if any research has investigated the relationship between ESE and the intention to engage in intrapreneurship. As noted earlier, greater ESE implies greater confidence to successfully complete entrepreneurial tasks, while lesser ESE implies lesser confidence to successfully complete entrepreneurial tasks, and we might expect the less-confident individual to want the advice and guidance of others. Moreover, we have argued above (in the context of decision-making autonomy) that individual entrepreneurship is, in general, likely to constitute a more difficult set of tasks than does intrapreneurship. As an intrapreneur, the individual can more readily seek advice and direction from more-senior managers, but as an entrepreneur, the individual needs to be much more self-reliant. Moreover, seeking advice and direction from others takes time and may incur financial and psychic costs. Accordingly, we expect that the greater the individual’s entrepreneurial self-efficacy, the less likely they will be seeking advice from others as to the appropriate action, and the more likely they are to prefer entrepreneurship to intrapreneurship, other things being equal. We nonetheless expect a positive relationship between ESE and intrapreneurial intentions because intrapreneurship is an outlet for the individual’s ESE and there is alternative employment within the firm as a non-intrapreneurial employee. This suggests the following hypotheses:

H7a

The more positive entrepreneurial self-efficacy, the more positive will be the entrepreneurial intention;

H7b

The more positive entrepreneurial self-efficacy, the more positive will be the intrapreneurial intention.

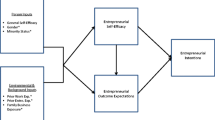

A schematic of our hypothesized model of the antecedents of entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions is shown in Fig. 1. Note that the hypothesized signs for entrepreneurial intentions and intrapreneurial intentions are the same for all independent variables except for the attitude to ownership and to risk, where the expected signs for attitudes to ownership and to risk tolerance are positive for nascent entrepreneurs but negative for nascent intrapreneurs.

4 Sample and method

The sample consists of 414 individuals surveyed at the beginning of their first MBA entrepreneurship course in Australia (n = 46), China (n = 39), India (n = 204), and Thailand (n = 125) between late 2003 and late 2004. These students might reasonably be considered potential entrepreneurs and/or intrapreneurs, since they were approaching a career decision point at which they might either enter into entrepreneurship, intrapreneurship, or some other employment (Shepherd and DeTienne 2005). In their course, they were required to form groups to write a formal business plan for a new venture in the context either of a new firm or an existing firm. The sample for each country was generally similar in characteristics such as age, work experience, and prior educational background, which allowed us to focus on other potential determinants of their intentions.

We measured intentions using a 7-point scale ranging from very unlikely (‘1’) to very likely (‘7’) over seven items measuring intentions to engage in a range of entrepreneurial behaviors, including items related to entrepreneurial activity and intrapreneurial activity (Table 1). We employed principal components analysis to investigate the underlying structure of these items, with oblique rotation.

To obtain measures for the entrepreneurial attitudes of the individuals in the sample, we used a conjoint experiment. Respondents were asked to evaluate hypothetical scenarios that offered combinations of income, autonomy, ownership, risk, and work effort. Each of the five salient outcomes was set as ‘high’ or ‘low’ (clearly defined initially) and respondents were asked to rate the attractiveness of each scenario on a 7-point Likert scale anchored by very low attractiveness (‘1’) to very high attractiveness (‘7’). Respondents were led through an initial scenario so that they understood the process (data were not collected), and then were advised to proceed at their own pace, but to continue working forward through the scenarios and not turn back to check earlier responses. To reduce the number of scenarios to a manageable number, we used a fractional factorial design that nonetheless maintains orthogonality among the outcome levels and the part-worth estimates (Hair et al. 2010). In line with the approach of Douglas and Shepherd (2002), each of 16 different scenarios was repeated once during the experiment to allow a test–retest measure of reliability. All respondents viewed the same 32 scenarios but, to avoid order effects in the data, the order of the scenarios was reversed in two versions of the survey, and the ordering of the salient outcomes in each scenario were reversed in two versions, providing four different orderings of the same scenarios and salient outcomes. Further details on the conjoint experimental method can be found in Green and Srinivasan (1978), Shepherd and Zacharakis (1999), Douglas and Shepherd (2002), Monsen et al. (2010), and Hair et al. (2010).

For self-efficacy, we used the entrepreneurial self-efficacy scale developed by Chen et al. (1998). This scale consists of 22 items measuring an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform entrepreneurial tasks, with each item measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from completely unsure (‘1’) to completely sure (‘5’). Following Chen et al. (1998), we calculated the total entrepreneurial self-efficacy score by taking the average of scores on the 22 items.

We included as control variables the respondent’s age, prior income level, total prior work experience, gender, three levels of prior education (Bachelors, Masters, and Doctorate), whether they were previously self-employed, and country of origin (Australia being the base case).

5 Analysis and results

The first research question is whether entrepreneurial intentions and intrapreneurial intentions are viewed as distinct and separate entrepreneurial activities. We asked how likely it was that respondents would engage in each of seven types of entrepreneurial activity (see Table 1). We employed principal components analysis (PCA) to investigate the underlying structure of the items in the survey. Using PCA with oblique factor rotation, we found two factors with eigenvalues above 1.00 which accounted for 73.3% of the cumulative variance. The two distinct factors were identified as those relating to entrepreneurial intentions (four items, α = 0.79) and those related to intrapreneurial intentions (three items, α = 0.77). Accordingly, we find support for Hypothesis 1 and conclude that self-employed entrepreneurship and corporately employed intrapreneurship were viewed by the sample respondents as distinctly separate career options.

Subsequently, two regression models were developed, one to explain entrepreneurial intentions and one to explain intrapreneurial intentions. We used the average score for the four items constituting the entrepreneurial intentions factor, and the average score for the three items constituting the intrapreneurial intentions factor, as the dependent variables in the two regression models. The independent variables were the same for each model, namely the human capital control variables, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and the attitudes toward the salient outcomes of income, autonomy, ownership, risk, and work effort. Similar to the results of Douglas and Shepherd (2002), we find that respondents had significantly reliable responses to the replicated conjoint profiles with an R 2 of 0.87.

We utilized ‘seemingly unrelated regression’ analysis within the STATA package to minimize the overall variance across the two models. The descriptive statistics and inter-correlations for the sample are shown in Table 2, and the regression coefficients for both models are shown in Table 3.

As is evident in Table 3, for the entrepreneurship model, we found significant positive relationships between entrepreneurial intentions and the attitudes to income, independence, and ownership, while attitudes to risk and work effort were found to be insignificant in determining entrepreneurial intentions. In addition, we found entrepreneurial self-efficacy to be positively and significantly related to entrepreneurial intention. Some human capital variables were also found to be significant: age and prior self-employment were positively related to entrepreneurial intentions, while individuals with more prior work experience were significantly less likely to form the intention to start a new venture. Regarding country differences, only the Indian students showed a significant relationship, indicating that they were significantly negatively inclined towards entrepreneurship as compared to the Australians.

The results of the intrapreneurship model are shown in the third column of Table 3. Similar to findings from the entrepreneurial intentions model, we find the individual’s self-efficacy to be significant and positively related to intrapreneurship intentions. Not similar, however, was the impact of attitudes to income, independence, and ownership, where we find no evidence of a relationship between these particular attitudes and an individual’s intention to be an intrapreneur. But we did find a significant negative relationship between tolerance for risk and intrapreneurial intentions, in contrast to the multivariate entrepreneurial intentions model, where we found no evidence of a relationship between an individual’s attitude to risk and entrepreneurial intentions. This suggests that, other things being equal, individuals who are more risk averse will tend to seek the shelter of a corporate environment to conduct their desired entrepreneurial behavior, as implied by Parker (2011, p. 31).

Concerning the control variables, we found that individuals with a prior doctoral education were less likely to form intrapreneurial intentions, and that prior bachelor and masters degrees had no significant effects on either entrepreneurial or intrapreneurial intentions. Regarding country differences, the only significant relationship was for the Thai students who showed a significant negative relationship with intrapreneurial intentions, indicating that they were negatively inclined towards intrapreneurship as compared to the Australians. A summary of the hypotheses, and whether they were supported or not, is provided in Table 4.

6 Discussion

In this paper, we examine the attitudinal and self-efficacy antecedents of the intention to behave in an entrepreneurial manner, where this intention can be directed towards actuality, either as self-employed entrepreneurship or as corporately employed intrapreneurship. Relative to the previous retrospective studies of the reasons entrepreneurs give for taking the self-employment path (e.g., Shaver et al. 2001; Carter et al. 2003), our study is prospective and uses a conjoint experiment to discern the revealed (rather than espoused) attitudes toward the various outcomes of the entrepreneurial experience. Further, we utilize multi-item factors to discern the willingness of respondents to engage in entrepreneurial or intrapreneurial activity, unlike most previous studies.

Consistent with previous work by Douglas and Shepherd (2002), we found that individuals who prefer more income and more independence have higher entrepreneurial intentions. In contrast to Douglas and Shepherd (2002), however, but in accord with Brockhaus (1980), Palich and Bagby (1995), and Busenitz (1999), we find no evidence that more risk-tolerant individuals will have higher entrepreneurial intentions. Instead, we find that lower risk tolerance is significantly associated with intentions for intrapreneurship. This difference may explain the conflicting results in previous studies of the dependence of entrepreneurial intentions on attitude to risk (or risk propensity)—it seems that the impact of risk attitude depends importantly on the type of entrepreneurial behavior contemplated by the individual. Accordingly, we wonder whether past studies may have confounded the relationship of attitude to risk and entrepreneurial intentions by not distinguishing between entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions.

Like Fitzsimmons and Douglas (2011), we found attitude to majority ownership to be significantly and positively related to entrepreneurial intentions, but our hypothesis that intrapreneurial intentions would be negatively related to attitudes to majority ownership was not supported at an acceptable significance level, although the sign was negative. This is, nonetheless, an interesting result, since it demonstrates that the benefits of firm ownership are either not highly valued by intending intrapreneurs, or that the psychic costs associated with firm ownership (such as stress) do not significantly drive individuals to intrapreneurship in preference to entrepreneurship, or that the psychic benefits and costs of majority ownership more of less offset each other for those with relatively strong intentions to become a intrapreneur. Our result does provide further evidence that attitude to independence and attitude to ownership are distinctly separate constructs, as implied by Shaver et al. (2001), and as demonstrated by Fitzsimmons and Douglas (2011).

No significant relationship was found between entrepreneurial intentions and attitude to work effort, similar to Douglas and Shepherd (2002), and supporting the overall conclusion from the replicated studies of Wiklund et al. (2003). And, contrary to Monsen et al. (2010), who found a significant negative relationship between intrapreneurial intentions and the expected level of work effort, we found no relationship between attitude to work effort and intrapreneurial intentions.

Significant positive relationships were also found between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and both entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions, which provides further evidence for the importance of self-efficacy and its relationship to intentions to engage in entrepreneurial behaviors. We note that ESE is significant at a higher level of significance, and has greater effect size, for entrepreneurial intentions as compared to intrapreneurial intentions. Thus, we speculate that individuals who perceive themselves as having greater ESE may be more likely to form the intention to engage in self-employed entrepreneurial behavior rather than corporately employed intrapreneurial behavior, but those with weaker self-efficacy might nonetheless form the intention to be an intrapreneur within the more-protective confines of an existing organization.

Regarding the control variables, we find age influences only entrepreneurial intentions, with older individuals having greater intention to engage in entrepreneurship, but caution the reader that the age range in the sample of MBA students was relatively narrow and hardly representative of the general population in each country. Similarly, the result for prior PhD education should be treated with caution, since the negative preference for intrapreneurship expressed by those with prior doctorates (almost certainly in non-business areas) probably reflects a preference to move from a technical to a managerial (rather than intrapreneurial) role within a firm. One other control variable, previous self-employment experience, exhibited a relatively large effect size and was significantly related to entrepreneurial intentions, but was not significantly related to intrapreneurial intentions.

Finally, it is interesting to note that, while a significant and positive simple correlation was found between risk tolerance and entrepreneurial intention (see Table 2), this relationship was not significant in the multivariate analysis when the impact of the control variables, self-efficacy, and other attitudes were considered. Similarly, intrapreneurial intention was significantly correlated with attitudes to independence and to ownership in the simple bivariate analysis, but was unrelated to these variables in the multivariate analysis. This illustrates the danger of jumping to conclusions on the basis of simple statistical analyses, of course.

7 Summary, implications, and limitations

In summary, we extend the entrepreneurial intentions literature beyond the typical approach that focuses on the intention to start an independent new business venture. Instead we note that many individuals choose to act entrepreneurially within existing firms as intrapreneurs, and that individuals might form intentions to be either an entrepreneur or an intrapreneur. We also offer evidence to refute the general presumption that nascent intrapreneurs are basically similar in attitudinal makeup and self-efficacy to nascent entrepreneurs, perhaps choosing to work as an intrapreneur within an organization because they have not yet discovered a viable new business opportunity, or not yet raised enough money, and/or not yet gained enough experience to go out on their own. Our findings reveal that nascent intrapreneurs tend to be different from nascent entrepreneurs in their cognitive make-up, having lesser entrepreneurial self-efficacy and greater risk aversion, and, consequently, they anticipate that intrapreneurship will be more attractive to them than entrepreneurship, and thus they form stronger intentions for intrapreneurship than for entrepreneurship.

This paper makes several main contributions to the entrepreneurship literature. First, it contributes to the understanding of the cognitive differences between intrapreneurs and entrepreneurs, adding to the findings of Honig (2001), Monsen et al. (2010), and Parker (2011). Second, to our knowledge, it is the first to demonstrate using multi-item measures that entrepreneurial intentions and intrapreneurial intentions are distinctly separate constructs. Third, it is also the first, to our knowledge, to find that the attitudinal antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions and intrapreneurial intentions are distinctly different. We find that risk tolerance is negatively related to intrapreneurial intentions but not significantly related to entrepreneurial intentions, suggesting that the prior ambiguity of this variable as a determinant of entrepreneurial intentions may have been the result of prior failure to recognize this dichotomy of entrepreneurial intentions. We find that attitudes to income, autonomy, and ownership are positively related to entrepreneurial intentions, but are insignificantly related to the formation of intrapreneurial intentions. These findings serve to advance our knowledge of the formation of entrepreneurial intentions, and to indicate that recognition of the heterogeneity on the opportunity side of the individual-opportunity nexus is indeed important (Shane and Venkataraman 2000; Wiklund et al. 2003).

7.1 Implications for educators, policy, and for future research

Educators might choose to incorporate into their course material the recognition that corporately employed intrapreneurship appears to be a distinctly different career alternative as compared to individual entrepreneurship, and that some students might be better suited to one of these alternatives rather than the other. Since attitudes can be changed over time given exposure to education and experience, educators might focus on changing the attitudes of their students to income, autonomy, ownership, and risk, such that more students develop the intention to behave entrepreneurially and/or intrapreneurially. Perception of risk is negatively related to knowledge (Gifford 1993), so the transmission of greater relevant knowledge to students will tend to raise both entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions. Risk management education, particularly in the context of new business ventures, seems a fruitful focus for entrepreneurship educators. Similarly, educators might focus more clearly on building entrepreneurial self-efficacy, since this is one of the major influences on the formation of both entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions.

Policy makers might add a second line of attack in their quest to nurture entrepreneurial business behavior by introducing legislation and incentive-based schemes to foster intrapreneurship rather than to focus almost exclusively on fostering individual entrepreneurship, as they typically do currently (Shane 2009). Programs to build self-efficacy, for example, introduced to the schooling systems and to the public more widely, might serve to increase the incidence of entrepreneurial behavior in both the individual and corporate realms. Programs to support new ventures financially, such as small business loans, grants, and provision of information that would otherwise consume scarce funds, would serve to reduce risk exposure and thus potentially cause intending intrapreneurs to become entrepreneurs instead, and enable potential entrepreneurs to launch and grow their new ventures.

Researchers might examine samples of identified nascent entrepreneurs and nascent intrapreneurs (e.g., using PSED data; see Carter et al. 2003; Reynolds et al. 2004), and/or of actual entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs, in an attempt to support or disprove the generality of the results reported here. Such research would serve to clarify the importance of self-efficacy and the attitudinal antecedents of intentionality in these two alternative entrepreneurial paths. Future studies should also utilize samples from North America, Europe, and other regions to determine the generality of these results. Another fruitful area for further research is to extend the entrepreneurial intentions literature to include further heterogeneity on the opportunity side of the individual–opportunity nexus. The diversity of entrepreneurial new ventures includes necessity, subsistence, lifestyle, speculative and growth ventures (see, for example, Morris et al. 2005; Barringer and Ireland 2006: 13–14), not to mention the distinction between social and commercial new ventures. We do not yet know whether social and commercial new ventures are seen as distinct and separate entrepreneurial alternatives, or whether intentions for these alternative entrepreneurial actions depend on different attitudes, self-efficacies, or other human characteristics. Thus, there is much scope for further research in the area of entrepreneurial intentions.

As pointed by Thompson (2009), previous studies of entrepreneurial intentions have utilized a variety of metrics and scales, and we too have introduced our own scales for entrepreneurial intentions and intrapreneurial intentions, as indicated in Table 1. Thompson’s (2009) development of a 6-item scale for entrepreneurial intentions is extremely thorough and results in a highly reliable measure of entrepreneurial intention. We note that, whereas the items in our measure focus on the timing (within 2 years or at some later time) and the type of new venture (to exploit a radical invention or introduce a new variant of an existing product), Thompson’s items include two related to timing (‘intend to set up a company in the future’ and ‘have plans to launch your own business’) plus other items relating to opportunity search, accumulating capital, reading books about setting up a firm, and spending time learning about starting a firm. Thus, Thompson has four items measuring the pursuit of actions that might typically precede the action of setting up a new venture, and, accordingly, his measure of intention largely focuses on behaviors rather than the underlying intention which he seeks to measure. In any case, Thompson focuses on the intention to start a new firm. Thus, scope exists for further research to test our four-item scale against Thompson’s six-item scale of entrepreneurial intentions, and to replicate and/or improve upon our three-item measure of intrapreneurial intentions, and/or to modify Thompson’s scale to measure intrapreneurial intentions. Similarly, Linan and Chen (2009) have developed a ‘cross-cultural’ entrepreneurial intentions scale. The efficacy of our scales might be tested against these newer scales in subsequent research projects.

7.2 Limitations

This study is not without its limitations. The use of students as proxies for potential entrepreneurs is subject to criticism, although the appropriateness of soon-to-graduate MBA students as subjects has been well-argued in the nascent entrepreneurship context by Shepherd and DeTienne (2005). We also note that MBA students are not representative of the population as a whole, so they may also differ significantly in terms of their attitudes to the salient outcomes of entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship. Their entrepreneurial self-efficacy is also probably significantly higher than the general population’s. Nonetheless, to the extent that this criticism is valid, we might regard this as a foundation study that needs to be validated by follow-up studies utilizing data from self-identified nascent entrepreneurs and nascent intrapreneurs (such as the PSED data identified by Carter et al. 2003).

A second main limitation is our use of a combined multinational study with an Asian focus. We cannot be sure that the findings generalize to other regions, such as North America and Europe, or to post-socialist countries (Tominc and Rebernik 2007). While two of the country dummies were significant, a thorough analysis of cross-national differences was prevented by small samples in two of the four countries, and this prevented our running separate regressions country by country. Thus, scope exists to test our intentions measures and their cognitive antecedents for cross-cultural applicability, and a comparison with the instrument developed by Linan and Chen (2009) might be conducted. Nonetheless, given the importance of ‘context’ in empirical studies (Johns 2006), there is potentially value in the use of a sample which is not from North America or Europe, as is found in the majority of intention studies.

Notes

We focus on the intention to behave entrepreneurially in either a new venture or within an established firm (as an intrapreneur), and thus we do not explicitly consider the individual’s intention to start a non-entrepreneurial new venture or to seek a non-intrapreneurial employment position. Low scores on our intentions measures may indicate that these non-entrepreneurial options would, however, be preferred. Similarly, for both entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship, we focus on the exploitation of the wealth-creating opportunity, regardless of who may have discovered or invented that opportunity.

Note that by ‘ownership’ we do not mean ‘psychological ownership’ of the new venture concept, which both intrapreneurs and entrepreneurs might be expected to feel, although this is expected to be weaker for the intrapreneur who should expect to share such ownership of the concept with senior managers. In both cases, the psychic benefits of ownership of the concept will contribute to the individual’s net psychic benefits associated with self-employed entrepreneurship or employed intrapreneurship. Note also that we do not infer that majority ownership of the firm is synonymous with entrepreneurship—the latter is a behavioral pattern that is driven by the attitudes to income, autonomy, risk, and work effort, and the net perquisites of ownership (Douglas and Shepherd 2000; Fitzsimmons and Douglas 2011), but none of those attitudes are either necessary or sufficient for entrepreneurship (Douglas and Shepherd 2000)—it is the sum of the products of the attitudes and the outcomes that underlie the formation of the intention to be an entrepreneur (or an intrapreneur, or neither). Thus, an individual might intend to be an entrepreneur without expecting much in the way of net psychic benefits from firm ownership.

References

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action-control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). Heidleberg: Springer.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122–147.

Barringer, B. R., & Ireland, R. D. (2006). Entrepreneurship: Successfully launching new ventures. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 893–921.

Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453.

Bird, B. (1992). The operation of intentions over time: The emergence of the new venture. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 17(1), 11–20.

Bird, B., & Jelinek, M. (1988). The operation of entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurial Theory and Practice, 13, 21–29.

Birley, S., & Westhead, P. (1994). A taxonomy of business start-up reasons and their impact on firm growth and size. Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 7–31.

Boyd, N., & Vozikis, G. S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 18, 63–77.

Brockhaus, R. H. S. (1980). Risk taking propensity of entrepreneurs. Academy of Management Journal, 23, 509–520.

Burgelman, R. A. (1983). A process model of internal corporate venturing in the diversified major firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28, 223–244.

Busenitz, L. W. (1999). Entrepreneurial risk and strategic decision making. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 35(3), 325–340.

Busenitz, L. W., & Barney, J. B. (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in small firms: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 9–30.

Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., Shaver, K. G., & Gatewood, E. J. (2003). The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 13–39.

Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 295–316.

Davidsson, P. (2006). Method challenges and opportunities in the psychological study of entrepreneurship. In J. R. Baum, M. Frese, & R. A. Baron (Eds.), The psychology of entrepreneurship. Mahway, NJ: Erlbaum.

De Noble, A., Jung, D., & Ehrlich, S. (1999). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The development of a measure and its relationship to entrepreneurial action. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 1999, 73–87.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Enquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Douglas, E. J. (2009). Perceptions: Looking at the world through entrepreneurial lenses. In A. L. Carsrud & M. Brannback (Eds.), Understanding the entrepreneurial mind, pp. 1–24. New York: Springer.

Douglas, E. J., & Shepherd, D. A. (2000). Entrepreneurship as a utility-maximizing response. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(3), 231–251.

Douglas, E. J., & Shepherd, D. A. (2002). Self-employment as a career choice: Attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions and utility maximization. Entrepreneurial Theory and Practice, 26, 81–90.

Eisenhauer, J. G. (1995). The entrepreneurial decision: Economic theory and empirical evidence. Entrepreneurial Theory and Practice, 19, 67–79.

Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1989). Some empirical aspects of entrepreneurship. American Economic Review, 79(3), 519–535.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fitzsimmons, J. R., & Douglas, E. J. (2011). Interaction between feasibility and desirability in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(4), 431–440.

Gagne, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 331–362.

Gatewood, E. J., Shaver, K. G., & Gartner, W. B. (1995). A longitudinal study of cognitive factors influencing startup behaviors and success at venture creation. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(5), 371–391.

Gifford, S. (1993). Heterogeneous ability, career choice, and firm size. Small Business Economics, 5, 249–259.

Green, P. E., & Srinivasan, V. (1978). Conjoint analysis in consumer research: Issues and outlook. Journal of Consumer Research, 5(2), 103–123.

Gupta, V. K., Turban, D. B., Arzu Wasti, S., & Sikdar, A. (2009). The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33, 397–417.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis—a global perspective (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Hamel, G. (2000). Leading the revolution. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Hisrich, R. D. (1990). Entrepreneurship/intrapreneurship. American Psychologist, 45(2), 209–222.

Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2002). Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating a new mindset. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Honig, B. (2001). Learning strategies and resources of entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 26(1), 21–35.

Johns, G. W. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 386–408.

Katz, J. A. (1992). A psychological cognitive model of employment status choice. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 17(1), 29–37.

Kolvereid, L. (1996). Organizational employment versus self-employment: Reasons for career choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 20(3), 23–31.

Kolvereid, L. (1997). Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrepreneurial Theory & Practice, 22(Fall), 47–57.

Krueger, N. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 18(1), 5–21.

Krueger, N. F., & Brazeal, D. V. (1994). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 18(Spring), 91–104.

Krueger, N. F., & Carsrud, A. L. (1993). Entrepreneurial intentions: Applying the theory of planned behavior. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 5(4), 315–330.

Krueger, N. F., & Dickson, P. R. (1994). How believing in ourselves increases risk taking: Perceived self-efficacy and opportunity recognition. Decision Sciences, 25(3), 385–400.

Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entreprenuerial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 411–432.

Lange, T. (2012). Job satisfaction and self-employment: Autonomy or personality? Small Business Economics (in press: available online since December 4, 2009).

Linan, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33, 593–617.

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172.

Mansfield, E. (1994). Microeconomics (8th ed.). New York: Norton.

Markman, G. D., Balkin, D. B., & Baron, R. A. (2002). Inventors and new venture formation: The effects of general self-efficacy and regretful thinking. Entrepreneurial Theory & Practice, 27(2), 149–165.

McClelland, D. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton: Van Nostrand.

McGee, J. E., Peterson, M., Mueller, S. L., & Sequeira, J. M. (2009). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: Refining the measure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33, 965–988.

McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 132–152.

Menzel, H. C., Aaltio, I., & Ulijn, J. M. (2007). On the way to creativity: Engineers as intrapreneurs in organizations. Technovation, 27(12), 732–743.

Monsen, E., Patzelt, H., & Saxton, T. (2010). Beyond simple utility: Incentive design and trade-offs for corporate employee-entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34, 105–130.

Morris, M. H., & Kuratko, D. E. (2002). Corporate entrepreneurship. Mason, OH: Thomson South-western.

Morris, M., Schindehutte, M., & Allen, J. (2005). The entrepreneur’s business model: Toward a unified perspective. Journal of Business Research, 58(6), 726–735.

Palich, L. E., & Bagby, D. R. (1995). Using cognitive theory to explain entrepreneurial risk-taking: Challenging conventional wisdom. Journal of Business Venturing, 10, 425–438.

Parker, S. C. (2011). Intrapreneurship or entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 19–34.

Pinchot, G. (1985). Intrapreneuring: Why you don’t have to leave the corporation to become an entrepreneur. New York: Harper & Row.

Reynolds, P. D. (1997). Who starts new firms? Preliminary explorations of firms-in-gestation. Small Business Economics, 9, 449–462.

Reynolds, P. D., Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., & Greene, P. G. (2004). The prevalence of nascent entrepreneurs in the United States: Evidence from the panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics. Small Business Economics, 23, 263–284.

Robinson, P. B., Simpson, D. V., Huefner, J. C., & Hunt, H. K. (1991). An attitude approach to the prediction of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial Theory and Practice, 15(4), 13–31.

Samuelsson, M., & Davidsson, P. (2009). Does venture opportunity variation matter? Investigating systematic process differences between innovative and imitative new ventures. Small Business Economics, 33, 229–255.

Scheinberg, S., & MacMillan, I. C. (1988). An 11 country study of motivation to start a business. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 1988, 669–687.

Shane, S. (2003). A general theory of entrepreneurship: The individual-opportunity nexus. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad policy. Small Business Economics, 33, 131–149.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226.

Shaver, K. G., Gartner, W. B., Crosby, E., Bakalarova, K., & Gatewood, E. J. (2001). Attributions about entrepreneurship: A framework and process for analyzing reasons for starting a business. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(2), 5–33.

Shepherd, D. A., & DeTienne, D. R. (2005). Prior knowledge, potential financial reward, and opportunity identification. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 29(January), 91–112.

Shepherd, D. A., Douglas, E. J., & Shanley, M. (2000). New venture survival—Ignorance, external shocks, and risk reduction strategies. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 393–410.

Shepherd, D. A., & Zacharakis, A. (1999). Conjoint analysis: A new methodological approach for researching the decision policies of venture capitalists. Venture Capital, 1(2), 197–217.

Stevenson, H. H. (1994). A perspective on entrepreneurship. In W. A. Sahlman & H. H. Stevenson (Eds.), The entrepreneurial venture. Boston: Harvard Business School Publications.

Stinchcombe, A. L. (1965). Social structures and organizations. In J. G. March (Ed.), Handbook of Organizations (pp. 149–193). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33, 669–694.

Tominc, P., & Rebernik, M. (2007). Growth aspirations and cultural support for entrepreneurship: A comparison of post-socialist countries. Small Business Economics, 28(2/3), 239–255.

Wiklund, J., Davidsson, P., & Delmar, F. (2003). What do they think and feel about growth? An expectancy-value approach to small business managers’ attitudes toward growth. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(3), 247–269.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A: Example of employment opportunity profile

Appendix A: Example of employment opportunity profile

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Douglas, E.J., Fitzsimmons, J.R. Intrapreneurial intentions versus entrepreneurial intentions: distinct constructs with different antecedents. Small Bus Econ 41, 115–132 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9419-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9419-y