Abstract

This paper studies how the presence of cross-border as opposed to domestic venture capital investors is associated with the growth of portfolio companies. For this purpose, we use a longitudinal research design and track sales, total assets and payroll expenses in 761 European technology companies from the year of initial venture capital investment up to seven years thereafter. Findings demonstrate how companies initially backed by domestic venture capital investors exhibit higher growth in the short term compared to companies backed by cross-border investors. In the medium term, companies initially backed by cross-border venture capital investors exhibit higher growth compared to companies backed by domestic investors. Finally, companies that are initially funded by a syndicate comprising both domestic and cross-border venture capital investors exhibit the highest growth. Overall, this study provides a more fine-grained understanding of the role that domestic and cross-border venture capital investors can play as their portfolio companies grow and thereby require different resources or capabilities over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The venture capital industry has long been a local industry (Cumming and Dai 2010), with geographic proximity to investment targets deemed necessary to locate and evaluate them (Sorenson and Stuart 2001) and to efficiently provide post-investment monitoring and value adding services (Mäkelä and Maula 2006; Sapienza et al. 1996). Nevertheless, the last decade has witnessed a strong growth in the international flows of venture capital worldwide (Alhorr et al. 2008; Meuleman and Wright 2011). Driven by increased competition in a maturing industry, venture capital investors have more intensively searched for investment opportunities outside their home regions. Moreover, broad-scale economic integration policies in the European Union have further contributed to increasing the speed of internationalization of the European venture capital industry (Alhorr et al. 2008).

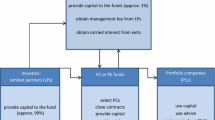

So far, scholars have primarily focused on the drivers of the venture capital internationalization process at the macro or industry level (e.g., Alhorr et al. 2008; Guler and Guillen 2010a; Madhavan and Iriyama 2009; Mäkelä and Maula 2005) and the strategies deployed by venture capital investors to overcome liabilities of distance and liabilities of foreignness (e.g., Bruton et al. 2005; Cumming and MacIntosh 2001; Fritsch and Schilder 2008; Guler and Guillen 2010b; Lu and Hwang 2010; Meuleman and Wright 2011; Pruthi et al. 2009; Pruthi et al. 2003; Wright et al. 2002). Despite increasing interest in the venture capital internationalization process, research on the impact of cross-border venture capital investors on the growth of portfolio companies is scarce. Cross-border venture capital investors are defined as investors that manage the investment from another country than the one in which the portfolio company started its operations (Mäkelä and Maula 2005). The research question we address in this paper is: how does the presence of cross-border, as opposed to domestic venture capital investors, relate to the growth of portfolio companies?

This question is non-trivial as, compared to domestic venture capital investors, cross-border venture capital investors might spur as well as constrain the growth of their portfolio companies. Cross-border investors may contribute to the internationalization and hence to a stronger growth of their portfolio companies by sharing their knowledge pertaining to internationalization and international markets (Fernhaber and McDougall-Covin 2009; Lutz and George 2010) and by legitimizing the unknown company in their home market (Hursti and Maula 2007; Mäkelä and Maula 2005). Nevertheless, cross-border venture capital investors may also constrain company growth. First, they may drive internationalization efforts of the company towards the investor’s home market, which is not always the company’s target market (Mäkelä and Maula 2005). Second, they stop active contribution to their portfolio companies much earlier than domestic venture capital investors when the prospects of companies have fallen (Mäkelä and Maula 2006). Prior studies show that while the probability of a successful exit is lower when venture capital investors invest across borders, it increases when distant venture capital investors syndicate with domestic venture capital investors (Chemmanur et al. 2011; Cumming and Dai 2010; Moser 2010). These studies, however, provide few insights into how different investors influence the growth of their portfolio companies between investment and exit. Moreover, a successful exit from the perspective of venture capital investors is not necessarily successful from the perspective of entrepreneurs or their portfolio companies (Gompers 1996).

This paper aims to compare the growth of young technology-based companies based on the location of their shareholders. Specifically, we distinguish between companies backed by domestic venture capital investors, by cross-border venture capital investors, and by a syndicate comprising both domestic and cross-border venture capital investors. We draw upon the resource based view of the firm and on stage development theories to build a dynamic model on the association between the geographic origin of venture capital investors and portfolio company growth. We hereby address the call by Zahra et al. (2007) to develop a more complete understanding of the role played by different venture capital investors as their portfolio companies develop.

Given the liabilities of newness and the lack of resources that young technology companies face (Vohora et al. 2004), a young company in the early phases of its technical and organizational development is more likely to require a higher level of involvement by a venture capital investor than a company at a later stage (Gupta and Sapienza 1992). We hence hypothesize that companies backed by domestic venture capital investors will initially exhibit higher growth compared to companies exclusively backed by cross-border venture capital investors, as value added from domestic investors will benefit them most in this early stage (Lockett et al. 2008). As companies age, the international knowledge, networks and reputation of cross-border venture capital investors will assist their internationalization, enabling a higher later stage growth. We further expect that companies raising venture capital from both domestic and cross-border venture capital investors will exhibit the highest growth rates, as they combine the complementary benefits of “localness” and of “foreignness”.

We use a sample of 761 technology-based companies from seven European countries that received initial venture capital between 1994 and 2004, and track sales, total assets and payroll expenses in these companies from the year of initial venture capital investment up to seven years after the investment. Random coefficient modelling is used as an appropriate longitudinal technique to model the dynamic nature of growth over time (Bliese and Ployhart 2002; Holcomb et al. 2010). We find broad support for our hypotheses.

Our research contributes to the venture capital and entrepreneurship literature. We argue that the resource needs of companies change over time, and show that different types of venture capital investors may address different resource needs. Domestic venture capital investors are better at supporting a company in its early growth, while the resources of a cross-border venture capital investor are especially valuable in a later phase when international expansion becomes more important. Hence, we provide a dynamic perspective on the resources venture capital investors may provide to their portfolio companies. We furthermore show that bundling the diverse resources from different types of venture capital investors allows overcoming the shortcomings of one particular type of investor.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides the theoretical background and develops hypotheses on the role of domestic and cross-border venture capital investors in portfolio company growth. Section 3 describes the research method. Section 4 presents the main research findings. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes by discussing the results from both a theoretical and a practical perspective.

2 Theory and hypotheses

The resource based view (RBV) of the firm defines a company as a collection of resources and states that the characteristics of the available resources affect the competitive advantage and thereby the growth of a company (Barney 1986, 1991; Penrose 1958; Wernerfelt 1984). Companies that possess more valuable, scarce, unique and imperfectly mobile resources are expected to outperform their resource-constrained peers and exhibit higher growth over time (Barney 1991; Chandler and Hanks 1994; Cooper et al. 1994). While high-tech companies are often based upon proprietary technological know-how, essential resources such as physical capital, human capital, financial capital or organizational resources may be lacking (Clarysse et al. 2007; Heirman and Clarysse 2004; Lockett et al. 2008). A major challenge of a company is hence to identify and acquire a relevant initial resource base (Penrose 1958). While early resource based scholars deemed it important to acquire or develop essential resources within the boundaries of an organization, later researchers have shown that companies may strongly benefit from the resource base of partner organizations (Bruneel et al. 2010; De Clercq and Dimov 2008; Lee et al. 2001; Lockett et al. 2008).

Venture capital investors are important by providing not only well-needed financial resources, but also intangible resources such as knowledge, access to networks and legitimacy (Fernhaber and McDougall-Covin 2009; Sapienza 1992; Sapienza et al. 1996). Through monitoring and governance activities, they actively foster the growth of their portfolio companies (Carpenter et al. 2003; Vanaelst et al. 2006). Companies can hence spur their growth through access to valuable intangible resources and capabilities provided by venture capital investors. Not all venture capital investors provide comparable resources, however. Compared to domestic venture capital investors, cross-border venture capital investors provide their portfolio companies with more specific resources to grow internationally (Mäkelä and Maula 2005, 2006). Hence, getting venture capital from cross-border investors may impact portfolio companies differently compared to getting venture capital from domestic investors only.

In what follows we elaborate on the processes that explain why different configurations of initial venture capital investors will relate differently to company growth over time. We hereby take a dynamic point of view, acknowledging that the needs of high-tech companies may change as they develop (Lockett et al. 2008; Vohora et al. 2004; Zahra et al. 2006). We argue that portfolio companies first have to refine their opportunities based on market feedback and put essential initial resources into place before they can enter a next phase in which they strive to achieve sustainable returns through market development. There are at least two reasons why we focus on the role of initial providers of venture capital in the subsequent growth of their portfolio companies. First, it is difficult to separate the influence of later-round investors from first-round investors (Sorensen 2007). For example, although later-round cross-border venture capital investors may influence subsequent portfolio company growth, the ability of the portfolio company to attract later-round cross-border venture capital investors may also reflect the value adding of the initial domestic venture capital investor. Second, by focusing on the initial providers of venture capital we minimise selection issues. Indeed, Bertoni et al. (2011) show that value adding effects have a large economic impact immediately after the initial investment, while the economic impact of selection is more modest.

2.1 The role of domestic venture capital investors in a company’s early growth phase

Young high-tech companies face liabilities of newness and smallness (Baum and Silverman 2004; Stinchcombe 1965) driven by an incomplete resource base, including a lack of organizational routines, networks, legitimacy in the marketplace and managerial expertise (Stuart et al. 1999; Vohora et al. 2004). Identifying and shaping new opportunities and subsequently investing in the resource base needed to pursue these opportunities are considered to be the “hallmark of entrepreneurial capabilities” (Arthurs and Busenitz 2006, p. 199). Given their experience and involvement in multiple companies, venture capital investors are instrumental in advancing their portfolio companies by assisting in shaping the opportunity, acquiring essential resources and developing organizational capabilities (Arthurs and Busenitz 2006). We argue that domestic venture capital investors will be more valuable in the initial growth phase than cross-border venture capital investors and hence that portfolio companies backed by domestic venture capital investors will initially exhibit superior growth compared to companies backed by cross-border venture capital investors.

The challenges of early stage high-tech companies are compounded by the fact that they often operate in complex and highly volatile environments (Stuart et al. 1999). This is such that the opportunities, initially identified in the prestart-up phase, have to be tested in the market and redefined depending on feedback received from different parties including potential customers (Arthurs and Busenitz 2006; Vohora et al. 2004). Based on newly acquired knowledge, early stage high-tech companies thus have to continuously re-assess their key strategies (Arthurs and Busenitz 2006; Vohora et al. 2004). For example, early market feedback enables entrepreneurs to evaluate and reassess initial ideas, hereby addressing weaknesses and deficiencies in the initial offering of services and/or products to the market (Vohora et al. 2004). Consequently, the early growth phase is one of continuous experimentation with the opportunity including product specification, market framing and defining marketing strategies. This entails a continuous search for feedback, followed by a repackaging of opportunities, before attaining a sustainable return phase (Vohora et al. 2004).

Next to clearly defining the opportunity and value creation model, the initial resource base has to be developed and organizational knowledge, capabilities and routines have to be shaped (Arthurs and Busenitz 2006; Gupta and Sapienza 1992; Zahra et al. 2006). Critical early resource acquisition activities include purchasing materials, buying or renting facilities and equipment and hiring employees (Newbert 2005). These are necessary to pursue the opportunity and implement a value-creating strategy (Arthurs and Busenitz 2006). Since the resources of young high-tech companies are limited at start-up, they continuously need to identify, acquire and integrate resources in their organization and subsequently re-configure those resources during the early start-up and initial growth phase (Arthurs and Busenitz 2006; Vohora et al. 2004).

Venture capital investors influence the opportunity shaping and resource acquisition processes by providing contacts to relevant external parties for soliciting feedback and by critically reassessing initial ideas based on this feedback (Gupta and Sapienza 1992). We expect that domestic venture capital investors are better positioned to assist their portfolio companies in developing these early strategic processes than cross-border venture capital investors. Geographical distance and investing across boundaries creates an information disadvantage and makes it more difficult to monitor companies closely (Dai et al. 2011). Telecommunication technology does not substitute yet for local presence and face-to-face contacts (Fritsch and Schilder 2008). Moreover, cross-border venture capital investors have been found to devote less time to their portfolio companies due to higher transaction costs (Fritsch and Schilder 2008). In addition they stop investing more promptly if their portfolio companies fail to meet expectations (Mäkelä and Maula 2006). Distance hence results in that cross-border venture capital investors are less closely involved with their portfolio companies. This is especially detrimental in the early development stage where venture capital input is likely to be especially beneficial to shape the opportunity, acquire early resources and develop organizational routines. Worst case, cross-border venture capital investors stop the financial support prematurely, which impacts technology-based companies’ growth significantly as they typically require high upfront investments to develop their technology and products prior to sales generation.

Furthermore, in contrast to domestic investors who initially direct the portfolio companies to domestic and nearby markets which may be easier and faster to conquer, cross-border venture capital investors may push portfolio companies to pursue foreign markets which may be more difficult and slower to conquer (Mäkelä and Maula 2005).

Finally, domestic venture capital investors have a more fine-grained understanding of the legal and institutional environment in which the portfolio company initially operates. As the interaction of new companies with the local environment is especially important to secure vital early resources, domestic venture capital investors are expected to be able to provide more valuable and relevant advice to their portfolio companies in the early development phase. Altogether, young, early-stage high-tech companies will initially benefit more from domestic venture capital investors compared to cross-border venture capital investors, leading to the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Portfolio companies that raise initial finance from domestic venture capital investors initially exhibit higher growth compared to companies that raise initial finance exclusively from cross-border venture capital investors.

2.2 The role of cross-border venture capital investors in a company’s later growth phase

Once an entrepreneurial opportunity has been refined and initial resources have been put in place, high-tech companies enter a new phase in which they strive to attain sustainable returns through market development (Vohora et al. 2004). High-tech companies often have a narrow product scope based on a technology that may quickly become obsolete and for which the domestic market size is limited (Coviello and Munro 1995; Knight and Cavusgil 2004; Litvak 1990; Lutz and George 2010; McDougall et al. 1994; Sapienza et al. 2006). This forces high-tech companies to internationalize, especially in the European context where domestic markets are typically too small to reach a minimum efficient scale (Bruneel et al. 2010; Coviello and Munro 1995; Knight and Cavusgil 2004; Litvak 1990; McDougall et al. 1994). The use of resources and the sale of outputs in multiple countries is hence critical for their further growth (Oviatt and McDougall 1994).

Compared to operating in domestic markets, expanding internationally entails costs that result from unfamiliarity with the foreign markets and from political, cultural and economic differences between foreign markets and the home market, causing liabilities of foreignness (Dai et al. 2011; Zaheer 1995). These liabilities of foreignness are especially difficult to overcome for young technology-based companies, as they often miss the resources and capabilities to deal with international expansion (Clarysse et al. 2007; Zahra et al. 2007). Both internal employees and external board members with varied skills and experiences in international markets may provide useful connections to existing institutions, companies and networks in target foreign markets (Fernhaber and McDougall-Covin 2009).

Cross-border venture capital investors may facilitate the growth of their portfolio companies (Dai et al. 2011; Lutz and George 2010) by limiting their liabilities of foreignness. First, cross-border venture capital investors may provide access to complementary knowledge-based resources in their country of origin; these would typically be unavailable to companies that raise finance exclusively from domestic venture capital investors. For instance, cross-border venture capital investors may be particularly able to provide their portfolio companies with knowledge and information about foreign legal and business issues (Mäkelä and Maula 2005).

Second, cross-border venture capital investors may provide access to their international network, allowing companies to make contact with relevant foreign suppliers, customers, financiers, key executives and other potential stakeholders (Mäkelä and Maula 2005; Sapienza et al. 1996). These relationships are likely to foster the growth of portfolio companies (Yli-Renko et al. 2002). Networks in foreign markets may also increase the ability of portfolio companies to identify new opportunities, which is expected to further enhance company growth (Mäkelä and Maula 2005; McDougall et al. 1994).

Finally, the mere fact of having a cross-border venture capital investor may provide endorsement benefits (Mäkelä and Maula 2005; Stuart et al. 1999). More specifically, cross-border venture capital investors are likely to legitimate their portfolio companies in foreign markets, which is expected to benefit them when they need to mobilize resources from these markets (Hursti and Maula 2007). The arguments above lead to the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

Portfolio companies that raise initial finance from at least one cross-border venture capital investor exhibit higher growth in a later stage compared to companies that raise initial finance exclusively from domestic venture capital investors.

2.3 Combining domestic and cross-border venture capital investors

We further claim that combining domestic with cross-border venture capital investors will be most beneficial for portfolio company growth. We expect that portfolio companies financed through a syndicate comprising both domestic and cross-border venture capital investors will exhibit higher growth rates than portfolio companies that are financed only by cross-border or by domestic venture capital investors.

Partnerships between cross-border and domestic venture capital investors provide portfolio companies access to a broader and complementary knowledge and resource base (Brander et al. 2002; Dai et al. 2011; Fritsch and Schilder 2008). Domestic venture capital investors may have a better knowledge of local market conditions and provide better access to local resources. As they are confronted with lower transaction costs, they may allocate more time to monitoring their local portfolio companies (Fritsch and Schilder 2008). Conversely, cross-border venture capital investors provide knowledge, networks and legitimacy that are particularly relevant in foreign markets. They may provide knowledge about foreign and legal issues (Dai et al. 2011), help in opening doors to foreign customers, suppliers, business partners and financiers (Lutz and George 2010; Mäkelä and Maula 2005), endorse the portfolio company in an international context (Mäkelä and Maula 2005; Stuart et al. 1999) and hence help to reduce the liabilities of foreignness (Mäkelä and Maula 2005). Cross-border and domestic venture capital investors thus offer complementary resources, increasing the resources, skills and information available for the monitoring and decision making of the portfolio companies (Jääskeläinen 2009).

We therefore expect that portfolio companies in which cross-border and domestic venture capital investors form a syndicate will outperform those in which only domestic or only cross-border venture capital investors invest. This leads to the final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

Portfolio companies initially backed by a syndicate of domestic and cross-border venture capital investors exhibit higher growth rates than portfolio companies backed exclusively by either domestic or cross-border venture capital investors.

3 Method

3.1 Sample and data

Data were collected through the VICO project, which is a multi-country project on the financing of entrepreneurial companies in Europe. We use part of the VICO database that contains longitudinal data on 761 venture capital-backed companies founded in one of seven European countries, including Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. The sample covers companies that received initial venture capital financing between 1994 and 2004. This ensures that a variety of investment periods were included in the sample. All companies were independent at start-up (i.e., other organizations may have been minority shareholders, but companies were not controlled by other business organizations) and existed for maximum 10 years at the time of the initial venture capital investment. Furthermore, all companies had to be active in high-tech industries, including aerospace, biotech, energy, ICT manufacturing, internet, nanotech, pharmaceutical, robotics, software, telecom, web publishing and other R&D. The dataset includes companies that eventually fail and hence results are not subject to survivorship bias.

For each venture capital-backed company, we collected detailed yearly financial statement data from the year of investment up until seven years later. Financial statement data were collected through Amadeus and country specific databases. We recorded key items from the financial accounts, including sales, tangible assets, intangible assets, total assets, payroll expenses, cash, equity and financial debt among others. Besides financial statement data, we collected data on the financing rounds in each company. In order to obtain data on venture capital investors that provide financing we combined multiple data sources, including Thomson ONE, Zephyr (a database similar to Thomson ONE, but with a stronger European focus), country specific databases, press releases, press clippings and websites. The data for each venture capital investment include investment year, investment amount, venture capital investor type and venture capital investor age among others. Finally, the number of patent applications and patents granted prior to the initial investment were retrieved for each portfolio company from the PATSTAT database.

Table 1 (Panel A) provides an overview of the companies in the sample by company founding period, first investment year, country and industry. The most important industry is the software industry (34%), followed by the biotech (18%) and the ICT industry (17%). Over 23% of the sample companies come from the United Kingdom, 18% from Germany, 15% from France and 13% from Italy. Belgian companies represent 12% of the sample and Spanish and Finnish companies approximately 10%.

3.2 Variable definitions

3.2.1 Dependent variables

Prior growth studies are often criticized because they do not take into account the multidimensional nature of growth (Delmar et al. 2003; Weinzimmer et al. 1998). The classification of a company as a growing company largely depends on the growth concept used (Delmar et al. 2003). This study takes into account the multidimensional nature of growth by using multiple growth concepts. We track changes in sales, total assets and payroll expenses (all measured in thousands of Euros) from the year of initial venture capital investment up to seven years after the investment (whenever data is available).Footnote 1 We refrain from using accounting-based indicators of profitability, which are inappropriate for young technology-based companies since most of these companies do not generate any profit during their first years of operations (Shane and Stuart 2002).

Sales, total assets and payroll expenses are the dependent variables as they are most commonly used growth concepts in empirical growth research (Delmar et al. 2003). Sales is often viewed as the most appropriate measure of company growth, since it applies to most companies and it is rather insensitive to capital intensity (Delmar et al. 2003). Sales is, however, not always a perfect indicator of growth. Especially in high-tech start-ups, the accumulation of assets and employment rather than sales leads the growth process (Delmar et al. 2003). We use payroll expenses instead of the number of employees as the former measure is highly correlated with the number of employees and has less missing data.

3.2.2 Independent variables

Independent variables capture the origin of the venture capital investors in the initial venture capital financing round. Companies backed by a single domestic investor serve as the base category against which all other companies are compared. In order to test hypotheses 1 and 2, a dummy variable CBVC is constructed which takes the value of 1 if a company raised venture capital from at least one cross-border venture capital investor. In order to test hypothesis 3, a second dummy variable, Mixed, takes the value of 1 if a syndicate of domestic and cross-border venture capital investors invested. If the results would indicate a stronger growth of companies backed by a mixed syndicate, however, this might either be explained by the difference in origin of the syndicate partners (as hypothesized) or merely by the broader resource base available through the venture capital syndicate (Manigart et al., 2006; Jääskeläinen, 2009). Therefore, a third dummy variable is added in order to disentangle the effects of the origin of venture capital investors from the effects of syndication. The dummy variable SYND takes the value of 1 if a company is backed by a syndicate comprising at least one domestic venture capital investor. Including this dummy allows comparing the growth of companies starting with a syndicate comprised exclusively of domestic investors with that of companies starting with a mixed syndicate.Footnote 2

3.2.3 Control variables

We control for venture capital investor characteristics, industry effects, year effects, country effects and portfolio company characteristics. For venture capital investor characteristics, we include VC investor age, measured as the difference between the investment and founding year of the lead venture capital investor providing initial financing. This measure partially controls for the fact that older venture capital investors may have more experience and may have established a broader network in the venture capital community (Sorenson and Stuart 2001). We further control for the type of venture capital investor. Venture capital investors are often affiliated with other organizations. These affiliations shape their strategies and objectives, which may influence the growth of their portfolio companies. For instance, bank-related venture capital investors may invest in companies, for which they can then provide further financial services, including debt finance (Hellmann et al. 2008). We include four non-mutually exclusive dummy variables, which are equal to one when at least one venture capital investor that provides initial financing is respectively a bank-related investor, corporate investor, university-related investor, government-related investor, and zero otherwise. Independent venture capital investors serve as the reference category.

The industries in which companies operate may significantly influence their growth patterns. We therefore include industry dummies in our models to control for potential industry effects. Industry classifications are based on four-digit NACE codes retrieved from the Amadeus database. We also include year dummies for the wide variety of investment periods included in our sample. Such controls are important since companies may exhibit different growth patterns depending upon the investment period when they received their initial venture capital investment. We further include country dummies to control for potential country effects.

For portfolio company characteristics, we include portfolio company age, measured as the difference between the year of the initial venture capital investment and company founding year, since it is well-established in the growth literature that age effects cause differences in growth patterns. We also control for the initial amount of finance raised by the portfolio companies. This is important since companies that raise more finance are able to mobilize more strategic resources early-on, and as such these companies are likely to develop a competitive advantage over their resource-constrained peers (Lee et al. 2001). In order to control for the number of subsequent investments in the portfolio company, we included a dynamic variable that captures the number of rounds the company has received. To control for possible differences in growth potential between companies, we include the intangible assets ratio, measured as the ratio of intangible assets to tangible assets. Prior research demonstrates that the ratio of intangible assets to tangible assets, as opposed to the absolute level of intangible assets, is a better predictor of growth potential (Villalonga 2004). As an additional control for possible differences in growth potential between the portfolio companies we included the number of patents applied for prior to the initial investment and which were eventually granted. Companies use patents to signal their value and commercial potential to outside stakeholders, including venture capital investors (Hsu and Ziedonis 2008). Hence, the patent stock is likely to represent one important factor on which venture capital investors select. The patent stock at the year of first investment is computed with a 15% yearly decay rate for each company.

There is obviously natural heterogeneity among companies in many extraneous variables besides our controls. Although these extraneous variables are not of any substantive interest, they might have an impact on the growth curve of companies. The strength of the longitudinal research design adopted in this paper is that any extraneous factors (regardless of whether they have been measured or not) that influence the growth of companies but whose influence is constant over time, are eliminated or blocked out as the size of companies is compared on several occasions (Fitzmaurice et al. 2004).

3.3 Econometric approach

Random coefficient modelling (RCM), also referred to as mixed modelling or growth modelling, is used as an appropriate longitudinal technique to study changes in sales, total assets and payroll expenses over time. Many of the standard statistical techniques, including ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions, are not appropriate when data consist of repeated measures that are correlated within companies as it invalidates the basic assumption of independence (Fitzmaurice et al. 2004). In order to deal with longitudinal data, scholars have often used general multivariate regression models that require longitudinal data where all companies have the same number of repeated measures, taken at time points, which are also the same for all companies (Fitzmaurice et al. 2004). These strict assumptions are rarely fulfilled in longitudinal studies and are not required when using a RCM framework (Fitzmaurice et al. 2004). Recent applications of the RCM framework in the management and entrepreneurship literature are available (e.g., Bliese and Ployhart 2002; Holcomb et al. 2010).

It is conceptually convenient to depict RCM as multilevel models (Fitzmaurice et al. 2004). The multilevel perspective is most useful if one assumes that companies randomly vary in terms of their initial size and growth trajectory. We discuss two levels of equations.

The first level in the hierarchy is the individual-level model, which specifies the nature of change for each individual company. The simplest model of individual company change is the straight-line (linear) growth model:

where DV ij is the ith company’s sales, total assets or payroll expenses, at the jth time point. t ij Is a simple count measure representing the successive years after the initial venture capital investment (0, 1, 2,…7) which is used to fit a linear trend to the ith company’s data across time. β1i and β2i are the company specific intercept and linear coefficient, respectively. The values of the βs can vary among companies. The e ij are the residuals. Equation 1 illustrates the flexibility of the RCM framework. Each company can have a different number of time points, data of each company may be measured at different times and each company can have a different growth trajectory (Fitzmaurice et al. 2004). RCM can also accommodate non-linear change. The simplest non-linear model is a quadratic model, which is specified by adding β3i t ij² to Eq. 1:

Group-level models constitute the second level in the hierarchy. Though the above individual regression equations are informative, researchers are usually interested in group effects. Conceptually, the random change parameters from the individual-level model (e.g., β1i , β2i and β3i or company specific intercept, linear coefficient and quadratic coefficient, respectively) are treated as response variables in a second set of models. Considering the quadratic individual change model (Eq. 2), the group level equations are:

where β1, β2 and β3 are the fixed intercepts in the level 2 equations and thus the averages of the individual-level parameters. β1, β2 and β3 indicate the nature of change for the group as a whole, where β1 is the group mean intercept or mean initial sales, total assets or payroll expenses; β2 is the group mean linear change and β3 is the group mean quadratic change or curvature. The β’s are fixed effects, because they do not vary among companies. b1i , b2i and b3i are the level 2 residual terms reflecting individual company differences from the fixed effects.

The unconditional RCM discussed above can be extended by incorporating predictors of change. The key predictors of change in this paper are the cross-border venture capital variable, the mixed syndication variable and the domestic syndication variable. These variables are all measured at the time of the initial investment. We examine whether the individual change parameters (β1i , β2i and β3i ) vary as a function of cross-border venture capital involvement, mixed or domestic syndication. These predictors of change are static covariates which are incorporated in the group-level equations. Considering the individual-level quadratic change model (Eq. 2) above, the group level equations studying change conditional on cross-border venture capital involvement and mixed or domestic syndication then become:

where CBVC i indicates whether cross-border venture capital was raised, MIXED i if the first investment was syndicated with at least one cross-border and one domestic investor, and SYND i indicates whether the first investment was syndicated with at least one domestic investor measured at the time of the initial venture capital investment for the i-th company. β4 represents the cross-border venture capital by intercept interaction and shows how the mean initial sales, total assets or payroll expenses of companies is dependent upon having cross-border venture capital. β7 is the cross-border venture capital by linear trend interaction and indicates how the mean linear trend in sales, total assets or payroll expenses is dependent upon the receipt of cross-border venture capital. β10 is the cross-border venture capital by quadratic trend interaction and indicates how curvature in sales, total assets or payroll expenses is dependent upon the receipt of cross-border venture capital. Similar interpretations hold for coefficients relating to the mixed syndication dummy and the domestic syndication dummy.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 (panel B) provides an overview of our sample, distinguishing between companies that raise financing from a stand-alone domestic investor, a cross-border investor (or multiple cross-border investors), a syndicate of domestic investors and a syndicate with at least one cross-border and one domestic investor. Two particular observations are worth noting. First, cross-border venture capital investors have been active over the entire time frame of our study, although most cross-border investments are concentrated during the dot-com bubble and subsequent years. Second, while previous studies have stressed the importance of domestic investors in order for portfolio companies to raise cross-border venture capital (Mäkelä and Maula 2008), 5% of the portfolio companies in our sample receive first round venture capital from cross-border investors only.

Table 2 gives an overview of the mean values of the control variables. The lead venture capital investor is on average (median) 13.9 years (5.0 years) old when investing in a portfolio company. Portfolio companies are on average 2.2 years (1.0 year) old, obtain €3,150,000 (€860,000) of initial venture capital finance, have 24% (8%) of intangible assets to total assets and hold 0.28 (0.00) patents when receiving the first venture capital investment. In 62.9% of portfolio companies at least one of the venture capital investors providing initial finance is an independent investor. In contrast, only 24.4% of portfolio companies received initial finance from government-related investors, 17.2% from bank-related investors, 14.1% from corporate investors and 6.7% from university-related investors.

Table 3 shows the origin of the cross-border investors in our sample. Most cross-border investors (43%) come from a Continental European country and a similar percentage come from the United Kingdom and Ireland (25%) and the United States (28%). Very few cross-border investors originate from other countries. U.K. and Irish cross-border venture capital investors invest relatively more frequently without local investors compared to U.S. and Continental European cross-border venture capital investors.

Table 4 reports descriptive statistics on sales, total assets and payroll expenses from the year of investment up to seven years after the initial venture capital investment. It confirms that the average venture capital backed company in our sample demonstrates significant growth over time. The large difference between mean and median indicates the distribution of sales, total assets and payroll expenses is skewed towards the higher values. We use the natural logarithm of sales, total assets and payroll expenses in all subsequent analyses, which has the advantage that it functions as a normalizing transformation and decreases the probability that extreme observations will drive our findings (Hand 2005).

Table 4 further indicates the varying sample size for the dependent variables at various points in time. Sample size changes as companies may fail or cease to operate over the time frame of the study. We did not completely eliminate these companies from the sample, as this would introduce survivorship bias (Cassar 2004). Rather, we used as much of the data that is available on the failed companies and hence include observations for the years these companies operated. A second source of missing data is due to the recent time when companies received initial venture capital. For instance, when a company received initial venture capital in 2004, data are simply unavailable for seven years after the initial investment. Our econometric technique takes this into account as we control for the investment year.Footnote 3

4.2 Model development

Any longitudinal study should start with fitting unconditional models, which do not incorporate predictors of change (Singer and Willett 2003). These models provide insights into the pattern of change in the entire sample of venture capital backed companies, which is critical in order to be able to answer questions about the effects of particular covariates on this growth pattern. The results of the unconditional analyses for sales, total assets and payroll expenses are shown in Table 5. Model 1 reports the means model or no change model, which will serve as the baseline model in order to determine whether more complex growth models are needed. Model 2 reports the linear growth model, in which a linear time predictor is introduced to the means model. Model 3 reports the quadratic growth model, in which the quadratic time predictor is added to the linear model.

Successively more complex growth models were evaluated for improvement in model fit over the baseline model by using the −2 log-likelihood (−2LL) statistic (Bliese and Ployhart 2002). The difference in −2LL is tested for statistical significance using a χ2 test. When comparing more complex models with more parsimonious models, the quadratic growth models for sales, total asset and payroll expenses (model 3) have a significantly better fit than their respective linear growth models (model 2) and the no-growth models (model 1). We discuss the quadratic growth model in more detail below. We focus on the sales models, but modelling total assets or payroll expenses yields similar results.

The quadratic growth model specifies a curvilinear change in sales, estimating initial sales, instantaneous rate of change in sales and curvature (which is a parameter that describes a changing growth rate of sales over time). Model 3 indicates that the average portfolio company has positive non-zero sales (5.537; p < 0.001) in the year of the initial venture capital investment. Because the instantaneous rate of change is positive, sales grow by 0.591 (p < 0.001) in the first year after venture capital investment. But the negative curvature (−0.053; p < 0.001) indicates that this growth does not persist, i.e., with each passing year, the magnitude of the growth in sales diminishes. In the next section further complexity to the unconditional quadratic growth models is introduced by including the controlled effect of the presence of at least one cross-border investor, syndication with both domestic and cross-border investors and syndication with domestic investors on sales, total assets and payroll expenses growth in venture capital-backed companies. This allows testing the hypotheses.

4.3 Hypotheses tests

Table 6 models the controlled effect of receiving first round venture capital financing from domestic venture capital investors, cross-border venture capital investors or syndicates with a mix of domestic and cross-border investors on the growth of venture capital-backed companies. We control for the age of the lead venture capital investor at the time of investment, venture capital investor types involved in the initial investment, portfolio company age, country effects, year effects, industry effects, the number of investment rounds in the company, the pre-investment number of patents, the first round investment amount and the relative amount of intangible assets at time of the first investment.

The growth pattern of the dependent variable is summarized in three parameters: the initial size, instantaneous rate of change (linear growth) and curvature (quadratic growth). We fail to find an effect of cross-border venture capital, either exclusively or in combination with domestic venture capital, on the initial level of sales, assets or payroll expenses. This suggests that the initial size of the portfolio company is not related to the probability of being funded by either cross-border or domestic investors (or a combination of both).

However, receiving initial finance from at least one cross-border venture capital investor significantly affects the growth of sales, assets and payroll expenses. Specifically, companies backed exclusively by cross-border venture capital investors exhibit a significantly lower instantaneous growth rate in sales (−0.496; p < 0.01), in total assets (−0.297; p < 0.05) and in payroll expenses (−0.321; p < 0.05) compared to portfolio companies backed by domestic venture capital investors. This provides support for our first hypothesis: companies backed by domestic venture capital investors initially exhibit higher growth compared to companies that raise initial finance exclusively from cross-border venture capital investors.

Companies backed exclusively by cross-border venture capital investors have a lower instantaneous growth rate, but curvature is significantly higher and positive for sales (0.076; p < 0.01) and assets (0.032; p < 0.05). Although the coefficient of payroll expenses curvature has the expected sign, it is not significant. This indicates that although sales and total assets initially increase at a higher rate in companies backed by domestic investors, their sales and total assets growth level off more quickly over time compared to companies backed by cross-border investors. This implies that, as time proceeds, the growth rate of companies backed by cross-border investors will eventually exceed the growth rate of companies backed by domestic investors. This provides support for our second hypothesis: companies backed exclusively by cross-border venture capital investors exhibit higher growth in later stages compared to companies that raise initial finance exclusively from domestic venture capital investors. Figure 1 shows that sales of the mean company, backed exclusively by cross-border venture capital investors, initially grows more slowly after investment than the mean company, backed exclusively by domestic venture capital investors. After six years, sales of companies backed by cross-border venture capital investors fully catch up with those of companies backed by domestic venture capital investors and their growth rates are higher. Footnote 4 This suggests that cross-border investors may be more beneficial in the long run compared to domestic investors, even if the initial growth of their portfolio companies is slower in the early years after the investment.

Portfolio companies initially backed by a mixed syndicate including both cross-border and domestic venture capital investors show a significantly higher instantaneous rate of change in sales (0.505; p < 0.05), total assets (0.329; p < 0.05) and payroll expenses (0.325; p < 0.10) than companies backed exclusively by domestic venture capital companies. Heterogeneous syndicates hence benefit the growth of portfolio companies. Nevertheless, in contrast to total assets and payroll expenses, the curvature for the change in sales of companies backed by mixed syndicates is negative and significant (−0.069; p < 0.05), implying that their steep growth rates level off. Figure 1 shows that, although companies backed by a mixed syndicate have similar first year sales compared to other venture capital backed companies, they develop into the biggest sales generators after seven years. Our findings thus provide strong support for hypothesis 3: a syndicate comprising domestic and cross-border venture capital investors positively moderates the relationship between the presence of cross-border venture capital investors and sales, total assets and payroll expenses growth. Sales, total assets and payroll expenses of companies, backed by a mixed syndicate comprised of domestic and cross-border venture capital investors are higher than those of all other companies during the whole observation period.

4.4 Robustness tests

We fitted several additional models to test for the robustness of our findings and assess the strength of alternative explanations. We focus on three potential concerns. First, as the results may be attributed to matching on the basis of unobservable characteristics, endogeneity is a concern (Shaver 1998). More specifically, cross-border (domestic) venture capital investors may select companies with different growth potential, or alternatively companies with different growth potential may select cross-border (domestic) venture capital investors (Eckhardt et al. 2006). Therefore, we carefully assess this concern. Second, although we focus on the initial providers of venture capital financing, the timing of entry of the cross-border venture capital investor may impact the results. A further robustness check hence estimates the effect of the timing of investment of a cross-border venture capital investor on sales growth. Finally, the observed dynamics might be stronger for more distant cross-border venture capitalists, in line with our theory development. We thus additionally estimate the impact of distance between a cross-border investor and the portfolio company.Footnote 5

We performed two tests in an effort to assess potential endogeneity concerns empirically (besides controlling for a company’s growth potential in our main analyses). First, we analyzed a subsample of companies for which data were available from two to one year before the initial venture capital investment was made. Pre-investment growth rates do not differ between companies exclusively backed by domestic investors, by cross-border investors, or by a mix of cross-border and domestic investors. This implies that, compared to domestic venture capital investors, cross-border venture capital investors do not select companies with higher pre-investment growth rates.

Second, we analyzed failures in greater detail. The proportion of failures in each group is relatively similar, with failure rates somewhat higher for companies backed exclusively by cross-border venture capital investors. This suggests that cross-border venture capital investors (whether they invest alone or in a syndicate with a domestic investor) do not necessarily have access to the highest or lowest quality companies. Additionally, we reran the RCM models, but excluded the companies that eventually failed from the sample. The results remain robust in these modified samples. Overall, these additional tests indicate that it is unlikely that selection is entirely driving our results.

In order to assess the impact of the timing of entry of the cross-border venture capital investor on company growth we estimated three additional models. In a first model, we only considered companies that were exclusively backed by domestic venture capital investors in the first round. Within this subsample, the growth pattern of portfolio companies with only domestic venture capital investors in later rounds are compared to companies that raise venture capital from cross-border investors in a later round. Unreported results indicate that attracting cross-border venture capital in a later round significantly increases company growth, consistent with our main analysis which showed that initial cross-border venture capital investors are associated with a positive effect on growth.

In a second model, the growth of companies initially backed by a mixed syndicate is compared to the growth of companies initially backed by domestic investors that attract cross-border investors in a later round. There are no significant differences in the growth pattern between the two groups of companies. Hence, starting with a domestic venture capital investor and adding a cross-border venture capital investor in a later round leads to a comparable growth of the portfolio company as starting with a mix of domestic and cross-border investors in the initial investment round.Footnote 6

Finally, a third model compares the growth of companies which are initially exclusively backed by cross-border venture capital investors to that of companies initially exclusively backed by domestic investors that attract cross-border investors in a later round. The latter exhibit a higher initial growth and show a lower curvature compared to the former, confirming that initial domestic venture capital investors are associated with a stronger initial growth of their portfolio companies. In all, these additional analyses strongly suggest that, conditional on raising domestic venture capital in the first investment round, the growth of a portfolio company is similar when a cross-border investor is added to the syndicate in the first or in a subsequent investment round.

As a final robustness check, the distance between the cross-border venture capital investor and its portfolio company is analyzed. We reran the RCM models substituting the cross-border venture capital dummy with a dummy that captures whether the cross-border investor originated from an Anglo-Saxon country. In order to fully observe the impact of the geographical, cultural and legal distance between investors and portfolio companies, we excluded the U.K. portfolio companies from this analysis.Footnote 7 The results are broadly consistent with those of the main models and the dynamics are often even stronger. This is in line with our theory as we focus in this analysis on Continental European portfolio companies and Anglo-Saxon investors, for whom the geographical, cultural and legal distances are higher than between portfolio companies and investors operating in different countries within Continental Europe (Mäkelä and Maula 2006).

5 Discussion and conclusion

While it is widely acknowledged that venture capital investors have on average a positive contribution on the growth of their portfolio companies (Puri and Zarutskie 2011), evidence is increasing that not all venture capital is the same. This paper contributes to this stream of research by differentiating between domestic and cross-border venture capital investors. While previous studies indicate that cross-border venture capital is an increasingly important phenomenon, especially for high-tech companies with high growth potential (Mäkelä and Maula 2008), there is little evidence on the relationship between raising venture capital from cross-border investors and the growth of portfolio companies. Based upon a sample of 761 young high-tech companies from seven European countries and using a longitudinal research strategy, we have shown that companies backed by domestic venture capital investors grow initially at a higher rate than companies backed by cross-border venture capital investors. In later years, however, companies backed by cross-border venture capital investors exhibit higher growth rates. Companies backed by a mixed syndicate comprising both domestic and cross-border venture capital investors grow more strongly, both in the short and in the long run, than other venture capital backed companies. We further showed that it generally does not matter for portfolio company growth when a cross-border venture capital investor invests, conditional on starting with a domestic venture capital investor.

Our findings suggest that proximity and knowledge of the local institutional and legal environment are important for venture capital investors investing in young companies. Domestic venture capital investors are better equipped than cross-border venture capital investors to overcome information asymmetries and to provide the resources relevant in the early growth phase. Refining the opportunity and building the early resource base is important in this phase, and domestic venture capital investors are better equipped to provide support in these matters. Cross-border venture capital investors, on the other hand, have a better knowledge of external markets and are able to provide legitimacy to portfolio companies in their home markets. These resources are especially beneficial for more developed companies. Our findings hence provide further support for the view that external parties may provide important resources to support the growth of entrepreneurial companies, but not all parties provide the same resources. Portfolio companies exhibit the strongest growth when combining local knowledge and support provided by domestic investors with international knowledge and legitimization provided by cross-border investors. We hence provide further evidence of the complimentary valuable resources that investors may bring to a heterogeneous venture capital syndicate (Dai et al. 2011).

A life cycle model emerges from our results: a young portfolio company benefits from tight monitoring and close interaction with its investors to shape its opportunity and to develop early organizational resources and routines. Domestic venture capital investors perform better in this phase as their geographic, legal and cultural distance with their portfolio company is smaller and their local institutional knowledge is higher. Alternatively, young companies backed exclusively by cross-border investors might be pushed to internationalize too early, while their resources are not yet into place. Portfolio companies benefit from cross-border investors in a later phase (whether they invest in the first or a later investment round), by facilitating entry in international markets through their knowledge and legitimacy. Combining the complementary resources of domestic and cross-border investors is hence relevant for company growth.

These findings are important, as few studies have disentangled the effects of domestic and cross-border venture capital investors on the growth of their portfolio companies. Most studies on the effects of venture capital have studied performance at the venture capital investor or fund level, focusing on portfolio company exit and/or survival, or focusing on post-IPO performance (limiting these studies to the most successful portfolio companies). This study, in contrast, is one of the first to focus on the growth of the portfolio company from the initial venture capital investment throughout the typical lifespan of a venture capital investment. This is important for entrepreneurs, as the goals of investors and entrepreneurs are not always aligned. Understanding how portfolio companies grow after having received venture capital, and how different types of investors contribute differently to company growth, is hence relevant.

The longitudinal analysis in this study offers an important methodological contribution to growth research, which typically measures growth as the difference in size between two points in time, thereby ignoring growth in-between these two points (Delmar et al. 2003; Weinzimmer et al. 1998). Our study demonstrates how different conclusions may be drawn when using different time frames. For instance, if we would have focused on the short term, our analyses would have indicated that first round cross-border venture capital involvement is associated with lower growth as the instantaneous growth rate in sales is lower in companies backed exclusively by cross-border investors. Yet, if we would have focused on the long term, our analyses would have indicated that cross-border venture capital is associated with higher growth as the growth rates of companies backed by at least one cross-border investor increase more strongly over time. Our dynamic approach hence allowed a more fine-grained understanding of the relationship between different venture capital investors and the growth of their portfolio companies. Taking advantage of recent developments in longitudinal data analysis to study the dynamic nature of growth over time is hence a fruitful avenue for future research.

The results on the impact of the timing of entry of the cross-border venture capital investors suggest that there is no significant difference in growth between portfolio companies that obtain cross-border venture capital in the first round (together with a domestic venture capital investor) or in a later round. As the timing of the entry of a cross-border venture capital investor does not seem to impact portfolio company growth, an interesting avenue for future research could be to investigate why some cross-border venture capital investors invest from the first round when they could wait, thereby reducing uncertainty, and invest later-on? What are the benefits of investing in the first round? Further, why do some cross-border venture capital investors invest alone, without syndicating with a domestic venture capital investor in the first round, as this seems to be a suboptimal strategy? We leave these questions for future research.

As with all research, this study also has some limitations. First, cross-border investors may differ from domestic investors in both their selection behavior and their involvement in portfolio companies after the investment. While we have provided descriptive evidence that neither cross-border nor domestic investors have a tendency to select companies that exhibit significant growth before the investment, different types of investors may still select portfolio companies on the basis of unobservable characteristics (Dai et al. 2011). However, the main purpose of this study was to gain an insight into how the presence of a cross-border investor is associated with the growth of portfolio companies. Whether these differences are due to selection or value adding is another question which warrants further study. Second, we acknowledge that understanding how cross-border investors influence internationalization of their portfolio companies, for instance, by analyzing exports, would be interesting. Such data is however not available in the current database.

Despite its limitations, the study provides valuable insights into high-tech entrepreneurs. Given the difficulty to raise finance from outside investors, high-tech entrepreneurs are under pressure to accept finance when and where they can find it. Yet, as we have demonstrated, early finance decisions may have a long-lasting impact on subsequent company growth. While portfolio companies of domestic investors are more likely to exhibit high growth early-on, companies backed by cross-border venture capital investors have more sustainable growth rates in the long run, especially when domestic venture capital investors co-invest with cross-border venture capital investors. Overall, our findings suggest that it might be worthwhile for entrepreneurs to extend their search for finance and target a broad and diverse investor base. Our study also has important implications for public policy makers. Public policy programs that aim to develop a strong local venture capital industry in order to foster the growth of local entrepreneurial companies should recognize that stimulating cross-border investments is beneficial. This not only increases the pool of financial capital available for entrepreneurial companies, but also provides them with complementary resources that help them to develop and grow more strongly.

Notes

The time frame of our study (seven years) covers the typical lifespan of venture capital investments which is between three and seven years.

We also developed count variables measuring the number of venture capital investors, rather than dummy variables. Results remained robust. As the use of dummy variables fits better with the theoretical arguments, we focus on the analyses with the dummy variables in the remainder of the paper. For instance, it may be sufficient to have one domestic venture capital investor investing together with one cross-border venture capital investor to diminish the information asymmetries experienced by the latter.

Traditional longitudinal techniques require either complete data or assume data are missing completely at random (MCAR), implying that an unconditional random process is responsible for the missing data. A major advantage of the RCM framework is that, missing data can be accommodated under the assumption of missing at random (MAR) (Long et al. 2009). MAR is less strict than MCAR and implies that a conditional random process was responsible for the missing data. The conditioning is assumed to be on another variable. In this study, the bulk of missing sales data at the end of the time frame are due to the recent time when companies received initial venture capital. For instance, when a company received initial venture capital in 2004, data is simply unavailable for seven years after the initial investment. MAR still yields unbiased estimates when using the RCM framework as long as the proper conditioning variables are included in the analysis, which is the case in our study as we control for the investment year.

The predicted growth curves for total assets and payroll expenses are not included due to space considerations, but are available from the authors upon simple request.

The additional models are not reported in detail due to space considerations, but they are available from the authors upon request.

There is one exception: companies getting cross-border venture capital in a later round exhibit a subsequent larger increase in total assets. This is not surprising as this larger increase in total assets is likely to reflect the investment by the cross-border venture capital investor.

Inclusion of the U.K. portfolio companies rendered similar results.

References

Alhorr, H. S., Moore, C. B., & Payne, G. T. (2008). The impact of economic integration on cross-border venture capital investments: Evidence from the European Union. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(5), 897–917.

Arthurs, J. D., & Busenitz, L. W. (2006). Dynamic capabilities and venture performance: The effects of venture capitalists. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(2), 195–215.

Barney, J. B. (1986). Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? The Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 656–665.

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Baum, J. A. C., & Silverman, B. S. (2004). Picking winners or building them? Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture financing and performance of biotechnology startups. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(3), 411–436.

Bertoni, F., Colombo, M. G., & Grilli, L. (2011). Venture capital financing and the growth of high-tech start-ups: Disentangling treatment from selection effects. Research Policy, 40(7), 1028–1043.

Bliese, P. D., & Ployhart, R. E. (2002). Growth modeling using random coefficient models: Model building, testing, and illustrations. Organizational Research Methods, 5(4), 362–387.

Brander, J. A., Amit, R., & Antweiler, W. (2002). Venture-capital syndication: Improved venture selection versus the value-added hypothesis. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 11(3), 423–452.

Bruneel, J., Yli-Renko, H., & Clarysse, B. (2010). Learning from experience and learning from others: How congenital and interorganizational learning substitute for experiential learning in young firm internationalization. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4(2), 164–182.

Bruton, G. D., Fried, V. H., & Manigart, S. (2005). Institutional influences on the worldwide expansion of venture capital. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(6), 737–760.

Carpenter, M. A., Pollock, T. G., & Leary, M. M. (2003). Testing a model of reasoned risk-taking: Governance, the experience of principals and agents, and global strategy in high-technology IPO firms. Strategic Management Journal, 24(9), 803–820.

Cassar, G. (2004). The financing of business start-ups. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(2), 261–283.

Chandler, G. N., & Hanks, S. H. (1994). Market attractiveness, resource-based capabilities, venture strategies, and venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(4), 331–349.

Chemmanur, T. J., Hull, T., & Krishnan, K. (2011). Do local and international venture capitalists play well together? A Study of International Venture Capital Investments. Working paper, SSRN eLibrary.

Clarysse, B., Knockaert, M., & Lockett, A. (2007). Outside board members in high tech start-ups. Small Business Economics, 29(3), 243–259.

Cooper, A. C., Gimenogascon, F. J., & Woo, C. Y. (1994). Initial human and financial capital as predictors of new venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(5), 371–395.

Coviello, N. E., & Munro, H. J. (1995). Growing the entrepreneurial firm: Networking for international market development. European Journal of Marketing, 29, 49–61.

Cumming, D., & Dai, N. (2010). Local bias in venture capital investments. Journal of Empirical Finance, 17(3), 362–380.

Cumming, D. J., & MacIntosh, J. G. (2001). Venture capital investment duration in Canada and the United States. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 11(4–5), 445–463.

Dai, N., Jo, H., & Kassicieh, S. K. (2011). Cross-Border Venture Capital Investments in Asia: Selection and Performance. Journal of Business Venturing (forthcoming).

De Clercq, D., & Dimov, D. (2008). Internal knowledge development and external knowledge access in venture capital investment performance. Journal of Management Studies, 45(3), 585–612.

Delmar, F., Davidsson, P., & Gartner, W. B. (2003). Arriving at the high-growth firm. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 189–216.

Eckhardt, J. T., Shane, S., & Delmar, F. (2006). Multistage selection and the financing of new ventures. Management Science, 52(2), 220–232.

Fernhaber, S. A., & McDougall-Covin, P. P. (2009). Venture capitalists as catalysts to new venture internationalization: The impact of their knowledge and reputation resources. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(1), 277–295.

Fitzmaurice, G. M., Laird, N. M., & Ware, J. H. (2004). Applied longitudinal analysis. New Jersey: Wiley.

Fritsch, M., & Schilder, D. (2008). Does venture capital investment really require spatial proximity? An empirical investigation. Environment and Planning A, 40(9), 2114–2131.

Gompers, P. A. (1996). Grandstanding in the venture capital industry. Journal of Financial Economics, 42(1), 133–156.

Guler, I., & Guillen, M. F. (2010a). Institutions and the internationalization of US venture capital firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(2), 185–205.

Guler, I., & Guillen, M. F. (2010b). Home country networks and foreign expansion: Evidence from the venture capital industry. Academy of Management Journal, 53(2), 390–410.

Gupta, A. K., & Sapienza, H. J. (1992). Determinants of venture capital firms preferences regarding the industry diversity and geographic scope of their investments. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(5), 347–362.

Hand, J. R. M. (2005). The value relevance of financial statements in the venture capital market. Accounting Review, 80(2), 613–648.

Heirman, A., & Clarysse, B. (2004). How and why do research-based start-ups differ at founding? A resource-based configurational perspective. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(3), 247–268.

Hellmann, T., Lindsey, L., & Puri, M. (2008). Building relationships early: Banks in venture capital. Review of Financial Studies, 21(2), 513–541.

Holcomb, T. R., Combs, J. G., Sirmon, D. G., & Sexton, J. (2010). Modeling levels and time in entrepreneurship research an illustration with growth strategies and post-IPO performance. Organizational Research Methods, 13(2), 348–389.

Hsu, D. & Ziedonis, R.H., (2008). Patents as quality signals for entrepreneurial ventures, Academy of Management Best Papers Proceedings. Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan.

Hursti, J., & Maula, M. W. (2007). Acquiring financial resources from foreign equity capital markets: An examination of factors influencing foreign initial public offerings. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(6), 833–851.

Jääskeläinen, M. (2009). Venture capital syndication: Synthesis and future directions, Working Paper Helsinki University of Technology, Espoo, p. 42.

Knight, G. A., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2004). Innovation, organizational capabilities, and the born-global firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2), 124–141.

Lee, C., Lee, K., & Pennings, J. M. (2001). Internal capabilities, external networks, and performance: A study on technology-based ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 615–640.

Litvak, I. (1990). Instant international: Strategic reality for small high-technology firms in Canada. Multinational Business, 2(Summer), 1–12.

Lockett, A., Wright, M., Burrows, A., Scholes, L., & Paton, D. (2008). The export intensity of venture capital backed companies. Small Business Economics, 31(1), 39–58.

Long, J. D., Loeber, R., & Farrington, D. P. (2009). Marginal and random intercepts models for longitudinal binary data with examples from criminology. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 44(1), 28–58.

Lu, Q., & Hwang, P. (2010). The impact of liability of foreignness on international venture capital firms in Singapore. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 27(1), 81–97.

Lutz, E. & George, G. (2010). Entrepreneurial Aspiration and Resource Provisioning: The Role of Venture Capital in New Venture Internationalization. Working Paper, SSRN eLibrary.

Madhavan, R., & Iriyama, A. (2009). Understanding global flows of venture capital: Human networks as the “carrier wave’’ of globalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(8), 1241–1259.

Mäkelä, M., & Maula, M. V. (2005). Cross-border venture capital and new venture internationalization: An isomorphism perspective. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 7(3), 227–257.

Mäkelä, M. M., & Maula, M. V. J. (2006). Interorganizational commitment in syndicated cross-border venture capital investments. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(2), 273–298.

Mäkelä, M. M., & Maula, M. V. J. (2008). Attracting cross-border venture capital: The role of a local investor. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 20(3), 237–257.

Manigart, S., Lockett, A., Meuleman, M., Wright, M., Landstrom, H., Bruining, H., et al. (2006). Venture capitalists’ decision to syndicate. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(2), 131–153.

McDougall, P. P., Shane, S., & Oviatt, B. M. (1994). Explaining the formation of international new ventures-the limits of theories from international business research. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(6), 469–487.

Meuleman, M., & Wright, M. (2011). Cross-border private equity syndication: Institutional context and learning. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(1), 35–48.

Moser, S. (2010). Does Diversity Among Co-Investing Venture Capitalists Add Value for Entrepreneurial Companies? Dissertation Executive Summary. SSRN eLibrary.

Newbert, S. L. (2005). New firm formation: A dynamic capability perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 43(1), 55–77.

Oviatt, B. M., & McDougall, P. P. (1994). Toward a theory of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(1), 45–64.

Penrose, E. T. (1958). The theory of the growth of the firm. New York: Wiley.

Pruthi, S., Wright, M., & Lockett, A. (2003). Do foreign and domestic venture capital firms differ in their monitoring of investees? Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 20(2), 175–204.