Abstract

This paper empirically examines the role of personal capital in the entry decision for US high-technology entrepreneurs. Our innovative approach utilizes both survey data and data from economics-based field experiments, which enables us to elicit and control for the risk attitudes of individual entrepreneurs in the study. Empirical findings suggest that (1) Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants, (2) credit cards, and (3) earnings from a salaried job are among the most important sources of funds for entrepreneurs in their decision to start up a firm. Our findings support Evans and Jovanovic (Journal of Political Economy 97(4):808–827, 1989) in that wealth appears to have a positive impact on the probability of starting up a firm, even when controlling for risk attitudes; however, risk attitudes do not appear to have a strong role to play in the entry decision overall. Policy implications suggest that firm start-ups are dependent on access to capital in both initial and early stages of development, and that government funding, including SBIR grants, is an important source of capital for potential and nascent high-technology entrepreneurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

We still know relatively little about the economics behind the use of alternative forms of start-up finance, including family lending, mutual guarantee schemes, and credit card finance. It is possible that these can be useful alternative sources of funds that can help entrepreneurs bypass credit rationing, but presently we do not know the precise extent to which this is the case. (Parker 2005)

1 Financing the entrepreneurial decision: an overview of the literature

In their interviews of randomly selected individuals, Blanchflower and Oswald (1998) found that many of those who were not self-employed, claimed that the primary reason they were not was a shortage of capital. It is clear that even if an individual correctly perceives an entrepreneurial opportunity, he may still be constrained from undertaking the opportunity if there is a lack of capital, collateral, or access to capital markets. The issue of collateral is particularly binding in the case of high-technology entrepreneurs whose firm assets are predominantly intangible ideas, copyrights, licenses, or patents and thus not conducive to collateral-based lending. Further, because of the relatively complicated nature of many new technologies and innovations, both bankers and the capital markets will have more than the usual asymmetrical informational problems in assessing the risk of firm projects. As Hart and Moore (1994) put it, the threat of default is high for the investors as they cannot prevent entrepreneurs from withdrawing their human capital from a funded project. This is suggestive that access to capital is an important factor to consider in studying the entry decision.

Regarding the role of risk attitudes, conventional wisdom suggests that while entrepreneurs are more likely to be risk takers, there is actually very limited empirical evidence to suggest that risk attitudes impact the entrepreneurial decision. Palich and Bagby (1995) and Keh et al. (2002) both find little or no impact of an individual’s risk taking propensity on entrepreneurial decisions. With regard to this study, we argue that risk attitudes may impact not only the individual’s entry decision directly, but also indirectly, as access to external sources of funds (different from stock wealth effects) may increase the individual’s willingness or ability to start a firm.Footnote 1 This suggests the need to control for risk attitudes of entrepreneurs when evaluating the importance of capital constraints on entry.

To date, few of the empirical studies have controlled for risk attitudes when attempting to measure the impact of liquidity constraints on the entry decision, an important issue that is addressed in the design of this study.Footnote 2 Further, it is it not well understood to what extent personal finances explain the individual’s decision to start a firm.

According to Parker (2005, p. 10), there are three highly influential theoretical models to explain why liquidity constraints become more severe as firm size decreases,Footnote 3 which are outlined in Stiglitz and Weiss (1981), de Meza and Webb (1987) and Evans and Jovanovic (1989). Stiglitz and Weiss (1981) argue that the riskiness of borrowers lead suppliers of capital to limit the quantity of loans; therefore, we can conclude that the inherent risk of entrepreneurial firms or the risk-loving attitudes of those that would pursue them (De Meza and Webb 1987) would lead to credit rationing alone. Another explanation stems from the fact that the amount of information about a firm is generally not neutral with respect to firm size. As Petersen and Rajan (1992, p. 3) observe, “Small and young firms are most likely to face this kind of credit rationing, which is based on asymmetrical information problems.”

The role of wealth and the access to capital on the individual’s decision to start a firm is unclear in the literature. In their survey article, Georgellis et al. (2005) provide a summary of study results regarding the impact of wealth (mostly inheritance) on the transition to self-employment in the US and UK. This survey finds mixed results with empirical evidence on the impact of inheritance on self-employment negative in 7 of the studies and positive in the other 11 studies. In their own research using data from the British Household Panel Survey, they conclude that inheritance raises the probability of transit to self employment, but also reduces the probability of firm survival, providing ample evidence of the presence of significant capital constraints for small entrepreneurs in the UK.

Evans and Jovanovic (1989) provide an approach that uses data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Young Men (NLS) to examine the role of wealth in the form of assets, wages, and earnings. They find that wealth increases the probability of becoming an entrepreneur, concluding that “…capital is essential for starting a business, and that liquidity constraints tend to exclude those with insufficient funds.” Cressy (2000) later argues that as wealth increases, risk aversion decreases, which increases the probability that an individual will become an entrepreneur. He further suggests EJ’s results may be biased by the omission of a measure of risk aversion in their model. Kan and Tsai (2006) test this claim using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics and find that wealth has a positive impact on start-ups even when they control for risk attitudes.

A key contribution of this study is to extend this model to include the impact of other potentially important measures of personal financing on the entry decision, such as personal loans, credit cards, Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants, inheritance, gifts, and earnings from a second job—while controlling for risk attitudes of the individuals. The application of experimental economics methods to elicit risk attitudes of subjects in the field (rather than relying on exclusively self reported data from surveys as most previous studies as have done) is an important contribution for several reasons. First, experimental tasks provide salient rewards to subjects to insure proper measurement of the individuals risk preferences—a crucial component in the study of the entrepreneurial decision.Footnote 4 Second, while complementary to previous studies, this particular approach attempts to improve on the inherent limitations on previous studies, which resort to generalizations about high-technology entrepreneurs from data collected either from (1) sampling the general population, (2) entrepreneurs in general, for example pooling data on both restaurateurs and high technology innovators, or (3) relying on campus laboratory experiments conducted on student test subjects.Footnote 5

In short, while the entrepreneurship literature has made great strides in trying to identify the role that personal characteristics play in the entrepreneurial decision, few studies have examined the extent to which other forms of personal financing (besides inheritance or lottery wins) impact this decision controlling for risk attitudes on the part of the entrepreneur. The development of our model is outlined in the next section.

2 Modeling entrepreneurial choice

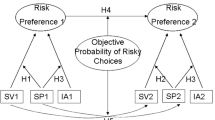

To date, the economic growth and entrepreneurship literatures are replete with studies that model this decision as one of income or entrepreneurial choice, focusing on various personal characteristics. Parker (2004) provides a comprehensive survey of theories, empirical models, and recent studies on this topic. Some of the early studies include that of Evans and Leighton (1989a, b, 1990), which links personal characteristics, such as education or experience (which proxy for the ability or skill of the entrepreneur), age, and employment status of almost 4,000 white males to the decision to start a firm in the US. Other studies, such as those of Bates (1990) and Blanchflower and Meyer (1994), emphasize human capital in the entrepreneurial choice. An important insight by Douglas and Shepherd (2002) was that the intention to become an entrepreneur is stronger for individuals with more positive risk attitudes, suggesting that empirical models of entry should control for risk attitudes.Footnote 6 Therefore, we start with a benchmark model of the entrepreneurial decision controlling for age, race, gender, education, wealth, and risk preferences.Footnote 7 We can then explicitly evaluate the impact of individual risk attitudes on the decision to start a firm, reasoning that decreases in risk aversion should increase the probability of an individual starting a firm. The corresponding refutable hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1

Decreases in risk aversion lead to an increased probability that an individual will start a firm.

This basic model (1) is then modified to include liquidity measures/sources of funds available to the potential entrepreneur,Footnote 8 demographic control variables, measures of individual ability, and additionally the potential impact of different sources of personal liquidity and government funding. These liquidity sources include inheritance, gifts, credit cards, earnings from a second job, SBIR grants, and private loans, allowing us to formally we test the following hypothesis regarding the potential impact of personal capital on the entry decision for the high-technology entrepreneur.

Hypothesis 2

Having received at least one SBIR increases the probability of starting a firm.

Hypothesis 3

Funds from use of Credit Cards increase the probability of starting a firm.

Hypothesis 4

Having a salaried or second job increases the probability of starting a firm.

Hypothesis 5

Having received an inheritance or gift increases the probability of starting a firm.

Hypotheses 2–5 articulate the impact of these various measures of personal capital or liquidity on the decision to start a firm. It is important to note that SBIR grants can be applied for before or after starting a firm, and by full-time, part-time, and/or salaried non-entrepreneurs alike. Some use the award as an impetus to start a firm, while others like university faculty, for example, may apply without the intention of leaving salaried employment. In larger organizations, often times salaried research staff are applicants for SBIR grants on behalf of the firm.Footnote 9

The modified model builds on previous studies by extending the standard specification to include new sources of initial start-up capital in a measure for firm liquidity constraints LC1, and a measure of the individual’s risk preferences CRRA Footnote 10: Thus, our modified entry model can be specified:

where Entry j is the probability of starting an entrepreneurial firm for individual j; Demo is a matrix of demographic variables to control for individual effects of age, gender, and race characteristics of the subject. The level of education of person j is used as a proxy for entrepreneurial talent or Ability j . CRRA j is a measure of the individual’s attitude towards risk taking under the assumption of constant relative risk aversion.Footnote 11 Wealth is measured by the log of total assets—an indicator of the importance of initial wealth of the potential entrepreneur—log transformed to control for variance in the data. We assert that since these entrepreneurial firms are young, their assets are a good proxy for the wealth of the entrepreneurs, who in these cases are the owners of the firm.Footnote 12 Estimates show that the assets of the entrepreneurial firm were far more statistically significant than household income as an indicator of the probability of starting a firm. LC1 j is a matrix of variables that measure the individual’s access to capital, which includes: inheritance, gifts, credit cards, earnings from another job, SBIR grants, and private loans. Since these sources are highly correlated within and across firm life stages and among each other, we test the respective hypothesis with separate regressions to avoid introducing multi-collinearity into our estimates.Footnote 13 The one exception is the liquidity measure credit cards, which is not correlated with wealth, so we include regression results for credit cards both with and without wealth or Log(Assets) in Table 3.

We also asked subjects if they had either (1) ever experienced a capital shortage with their firm or (2) were currently experiencing a shortage of capital, in order to evaluate the impact of various sources of capital on the early developmental stage of the firm. In particular we wanted to evaluate the firm’s use of internal (cash flow from operations) versus external funds (credit cards, private loans, government grants, and loans, equity). We formalize this test of the importance of cash flow in reducing current capital shortages of the firm as:

Hypothesis 6

Private sources of capital reduce the probability of current firm shortages of capital.

Hypothesis 6 tests the significance of various sources of financing in reducing the firm’s current shortage of capital, which speak to the importance of access to capital for reducing the firm liquidity constraints associated with the early growth stage of firm development. Our capital shortage equation is specified:

Our models specified in Eqs. 1–3 will then be estimated in order to provide empirical evidence to support or refute the importance of each of these hypotheses regarding the importance of various sources of personal financing sources for the entrepreneur. Because the sources of funding available to the entrepreneur vary over time, our measures LC1 j and LC2 j do as well. This reflects that fact that later stage (relatively older) firms have access to different sources, such as equity capital and cash flow from operations.

3 Data

3.1 Field data, survey data and variable definitions

3.1.1 Field data

The field experiments were conducted in April and November 2004 at two of the bi-annual SBIR national conferences. Our field data were collected from a booth set up in the exhibitor’s area of the conferences. The subjects, who later would choose to participate in a series of paid experimental tasks, were first asked to complete a survey of firm and individual characteristics.

An important contribution of our approach is the ability to both measure and control for individual risk attitudes of subjects by compiling data through a series of field experiments, detailed in Elston et al. (2005). From this study, we combine the experimental data on individual risk attitudes with the survey data to analyze the entry decision controlling for risk attitudes and liquidity. We recognize this is not a sample of the general population; that was not our intention. It does allow us to test and control for the importance of risk attitudes on the decision to start a firm for high-technology entrepreneurs, which is not possible with survey data alone. This field approach is also preferable to the common practice of using students to proxy for the decision making of real life entrepreneurs because it allows us to capture more precisely the decision-making process of the high-technology entrepreneur.

3.1.2 Sample selection

It is important to note that when we study a specific field population of interest—high technology entrepreneurs in this case—this in itself does not constitute selection bias. Selection bias is a statistical sampling problem for which it is not sufficient to establish that there has been selection. Rather, one must establish that the quantity of interest (access to capital) is systematically different in the sample (high technology entrepreneurs attending the conferences) than in the entire population of interest—all high technology entrepreneurs—in order to establish that selection bias has taken place. We argue that in the worst case, having previously received an SBIR award, it is actually less likely that one would attend another SBIR conference (which provides seminars on how to get an award), so that any empirical results indicating significance of the SBIR award would tend to be underestimated in our empirical results.

3.1.3 Survey data

In addition to the field experiments we also collected survey data from a total of 182 individuals. Responses to the questionnaires allowed us to stratify the sample into Entrepreneurs (E) and Non-Entrepreneurs (NE).Footnote 14 We classify 44% of these as entrepreneurs since they reported self-employment status and income. Thus, we have information on a total of 80 Es and 92 NEs. In each case we required that individuals provide information on the nature of their entrepreneurial firm before we classified them as an entrepreneur, while NE includes potential entrepreneurs. All subsequent analyses in this study use either data collected on entrepreneurs only (both part-time and full-time) or the whole sample, which includes non-entrepreneurs.Footnote 15

3.1.4 Measuring risk aversion

Our measure of risk aversion is derived from experiments that employ expected utility theory and multiple price lists to elicit risk preferences of subjects.Footnote 16 In brief, we apply a constant relative risk aversion characterization of utility, employing an interval regression model. The dependent variable in the interval regression model is the CRRA interval that subjects implicitly choose when they switch from lottery A to lottery B in a ten-decision lottery matrix. For each row of the lottery matrix, one can calculate the implied bounds on the CRRA coefficient, and thus a measure of risk aversion can be calculated for each subject in the study. The CRRA utility of each lottery prize y is defined as: U(y) = (y 1−r)/(1 − r) where r is the CRRA coefficient.Footnote 17 In this context, r = 0 denotes risk neutral behavior, r > 0 denotes risk averse behavior, and r < 0 denotes a risk lover. We found that most of the subjects were risk averse with a mean r = 0.25 and that the E group was less risk averse on average than the NE group. The entrepreneurs in the study average 44 years of age, are 34% female, and 49% have completed at least some higher education. We also found that they were more likely to be Asian (13 vs. 5%) and had a higher income (48 vs. 42%) than the NEs.

Our entrepreneurship data are representative of US high-technology entrepreneurs rather than entrepreneurs in general, with the number of individuals describing their primary self-employment business as engineering or business technology related (47), software or information technology (22), medical or university (9), and other (2). In contrast, the non-entrepreneurs reported employment in mostly other sectors of the economy including: engineering or business technology (12), software or information technology (2), medical or university (5), goverment (16), and other (64)—which included food, textiles, and retail.

3.1.5 Descriptive statistics

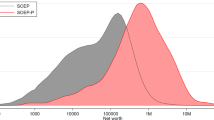

Responses to questions on sources of funding are summarized in Appendix A, with key variables presented in Graphs 1 and 2. Graph 1 suggests that most entrepreneurs, 84%, reported having experienced a shortage of capital at some time, with another 48% reporting that they are currently experiencing liquidity constraints, which underscores the potential importance of including these factors in studying entrepreneurial decision making.

Source: All charts are based on own calculations

Focusing on the start-up phase of the entrepreneurial firm, Graph 2 shows that inheritance (3%) and gifts (1%) are not as frequent as some studies have found to be the case in the UK (Blanchflower and Oswald 1998). Our interpretation is that perhaps inheritance is less common in the US, or at least does not drive entrepreneurship in the high-technology arena. We speculate that since these entrepreneurs report working predominantly in the high-technology sector, perhaps other factors, such as education and skills, may be more important than inheritance in determining the decision to start a firm. Supporting this conclusion is the fact that earnings from another job (58%) are a common way that these entrepreneurs secure funding to start up their firm.Footnote 18 Private loans from individuals and banks are also an important source of funds, as are, to a lesser degree, credit cards. When asked how they finance the firm currently, 74% responded cash flow from operations, which is consistent with the well-known financing hierarchy structure of most firms—that is, most firms prefer to use less expensive internal funds over more costly external capital. Of course, these findings are only suggestive, and we need to control for other factors in a regression context to determine their degree of importance.

Government loans and grants appear to have an important role in both the start-up and early growth phases of these firms. When asked how the firm is funded today, 56% reported that government support was important versus 20% for equity capital—a somewhat surprising result given the size and liquidity of US equity markets, although again these are relatively young firms. A relatively large number of these entrepreneurs have applied for, 34%, and received, 20%, government support in the form of SBIR grants, which speaks positively about both the public awareness and potential importance of this small business program for funding firm start-ups. This finding is consistent with national data analyzed by Branscomb and Auerswald (2002), who estimate that the federal government provides 20–25% of all funds for early stage technology development in the US.

While this data speaks to the potential importance of these sources of funding, the statistical significance of these sources on the entry decision are calculated by estimating our Probit equation controlling for risk attitudes and demographic factors.

3.1.6 Variable definitions

In Table 1 we list the key variable definitions with descriptive statistics. Explanatory variables are grouped into general variables of interest, those relating to sources of financing used specifically in the start-up phase of the firm, and finally sources of financing that are currently used to grow the entrepreneurial firm. Since the last two groups refer to financing at different stages of firm development, they allow us to distinguish the importance of different sources of capital on firm start-up and subsequent firm development and growth stages.

4 Empirical results

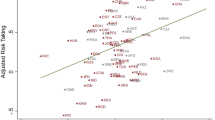

Table 2 lists Probit estimates for entry by subject demographic, risk attitude, and wealth—as measured by the log of total assets. Generally, the demographic variables become less important in predicting Entry once we control for risk attitudes and wealth, both of which are statistically significant. In column 1, the measure of risk or CRRA is large, negative and statistically significant, indicating that higher levels of risk aversion reduce the probability of entry or starting up a firm. This finding is important because it provides some of the first empirical evidence (which supports intuition) that individual risk attitudes—specifically risk aversion—reduces the probability that an individual will choose to start up a firm.

It is interesting to note that the smaller and almost significant effects of race and gender found in the reduced model data both disappear when we add measures of risk attitudes and wealth, which suggests it may be important to control for these demographic characteristics, even if they are not of great import in predicting entry itself.Footnote 19 Overall, our evidence is also consistent with findings of Kan and Tsai (2006), which find that risk aversion has a negative impact on the entry decision even when we control for wealth, which supports Hypothesis 1—Decreases in individual risk aversion lead to an increased probability that an individual would start a firm.

Since the correlation matrix of key variables listed in Appendix B indicates that assets and liquidity sources were highly positively correlated, as we might expect, we entered these sources of financing separately in our model as reflected in Table 3. The only exception was credit cards, which were not correlated with wealth; thus, Table 3 has models that test for the importance of CCards both with and without wealth effects in the model. In Table 3 estimates, SBIR-rec is both economically and statistically an important indicator of entry, supporting Hypothesis 2—Having received at least one SBIR grant increases the probability of starting a firm. This finding is consistent with national data on SBIR recipients, which indicates that almost 40% of individuals who received an SBIR award stated they would either (1) definitely not or (2) probably not or (3) might not have undertaken their research project in the absence of the SBIR award.Footnote 20 The statistical significance of the SBIR on entry is not due to the fact that the data were gathered at a SBIR conference; in fact, only seven individuals in our entry sample had actually received an SBIR award in the past, much fewer than those who received other types of funding from other sources, such as credit cards, loans, and earnings from a second job, which were statistically less significant.

Estimates indicate that CCards and earnings from a 2nd Job were small but significant sources of capital for firm start-ups, thus providing support for Hypothesis 3—Funds from Credit Cards increase the probability of starting a firm, and since the finding on the significance of CCards is present whether we control for wealth effects or not, see regressions 4a and 4b; so this is a particularly robust result. Earnings from a second job are also positive and statistically significant, providing evidence to support Hypothesis 4—Having a Second Job increases the probability of starting a firm. Results indicate that neither inheritance nor gifts were statistically significant in predicting entrepreneurial entry for high-technology entrepreneurs; thus, we find no support for Hypothesis 5—Having received an Inheritance or Gift increases the probability of starting a firm.Footnote 21 In non-reported results, neither loans nor other sources of capital were statistically significant in predicting entry.

Table 4 contains Probit estimates testing whether various sources of funding (LC2: government loans, private loans, credit cards, earnings from a 2nd job, equity, cash flow from operations, and having received an SBIR grant) reduce the probability of current capital shortages for entrepreneurs. Regressions were run only on data from entrepreneurs. In regression 1 estimates are reported from a backward stepwise regression with the inclusion criteria set at 10% with all possible financing sources in the model (but controlling for all demographic variables). We note that SBIR grants or SBIR-rec is statistically significant and negative in both regressions, indicating that receiving an SBIR reduces the likelihood of experiencing a shortage of capital. No other sources of funding were found to be significant in the model at the 10% level in reducing the current capital shortage. In the second model, we did not control for any demographic variables in the model. Results in regression 2 of Table 4 reveal that Cash flow from operations and SBIR-rec are both statistically significant at the 10% level. Therefore, we find weak support for Hypothesis 6—Private sources of capital, that is specifically cash flow from operations and having received an SBIR grant, reduce the probability of current firm shortages of capital.

5 Conclusions

This study provides insight into the entry decision of high-technology entrepreneurs in the US, which have been an economically important source of innovation and growth in the US during the last 2 decades.

We find that capital constraints are problematic for high-technology entrepreneurs, negatively impacting the probability of firm start-up. While empirical results are consistent with previous studies on the importance of wealth in the entry decision, we find that the additional measures of personal liquidity are also significant in predicting entry. Specifically SBIR grants are found to be an important source of funds for improving the probability of entry for high-technology entrepreneurs, dominating all other sources of personal capital in the study. From an industrial policy perspective, this suggests that the SBIR program may be money well spent in terms of policy goals to increase the probability of new high-technology start-ups.

Once the firm is established and growing, SBIR grants dominate as an important source of funds for reducing the probability of a capital shortage—a finding that is robust to model specification. In context, our findings suggest that when the firm has more alternative sources of funds, including cash from operations, loans, and equity, it prefers to use cash flow from operations and SBIR rather than other sources of external funds. This is broadly consistent with the well-established preferences of firms for use of internal over external funds. It is important to note that this finding does not support the notion of “SBIR mills”—firms who subsist predominantly from SBIR grants rather than from firm income derived from successfully developing and commercializing new technologies.

Contrary to findings of previous studies, including Blanchflower and Meyer (1994), our results provide evidence that gifts and inheritance are not important indicators of entry—at least for our sample of US high-technology entrepreneurs. Our interpretation of this finding is that our data, unlike the large national survey panels, represent more accurately one type of entrepreneur—the high-technology entrepreneur—whose path to entry is less likely to be predicted by chance gifts or inheritance, but more likely by deterministic factors, such as education and skill-based sources of financing, like grant writing—e.g., SBIR grants.

We also found little evidence that risk attitudes were important in predicting entry; risk attitudes were only significant when wealth was included but access to capital was excluded from the entry model. This suggests that risk attitudes may not be as important in the entry decision as many have thought, indicative that the distribution of risk attitudes may be similar between entrepreneur and non-entrepreneur groups. This is consistent with earlier findings from Elston et al. (2005), which found that these same entrepreneurs were not risk loving; rather, they appeared to be only somewhat less risk averse than their non-entrepreneurial peers. These findings are also consistent with those of Palich and Bagby (1995) and Keh et al. (2002), which found little difference in risk propensity measures between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs.

One caveat of our study is that results may or may not be easy to generalize to all entrepreneurs; the trade-off is that it does provide a better understanding of the importance of financing sources on the entry decision of US high-technology entrepreneurs—an economically and strategically important group about which we understand too little.

These findings suggest a number of directions for future research. Our study on the importance of sources of financing is neither exhaustive nor complete; many other sources may be important, in particular for the growth stage of the firm—including angel or venture capital financing. Future studies may also be warranted to better examine the impact of the broad spectrum of governmental support in funding the firm. The Small Business Administration, for example, has a number of programs in addition to the SBIR that support firm start-up and development, including the Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) program, a variety of loan programs, surety bond guarantees, as well as various training programs to support small business development.

In addition, it is interesting to note our study’s finding on the importance of a second salaried job on the individual’s decision to start a firm. This model is less common in Europe and other places, and suggests that from a policy perspective it may be interesting to consider how impediments to holding a secondary job inhibit entry and innovation of small firms in Europe.

Notes

By direct effects, we mean that risk-averse individuals may be less likely to leave salaried employment to start their own firm (Parker 2004).

Kan and Tsai (2006) control for risk attitude in their study on the importance of wealth.

Stiglitz and Weiss (1981) argue that as the rate of interest rises, so does the riskiness of borrowers, leading suppliers of capital to limit the quantity of loans they make. Most potential lenders have little information on the managerial capabilities or investment opportunities of such firms and are unlikely to be able to screen out poor credit risks or to have control over a borrower's investments. Also if lenders are unable to identify the quality or risk associated with particular borrowers, Jaffe and Russell (1976) show that credit rationing will occur.

Salient rewards refer to an experimental design where the payoffs increase with performance in order to induce subject behavior consistent real world competitive environments. Although for smaller payouts as in this study, this appears to be less of an issue (Holt and Laury 2002).

Use of experimental data by design does involve using not a random sample of the general population.

Their study uses survey data from 300 Australian students to measure risk preferences from responses to questions regarding hypothetical preferences for salary (low risk) versus performance-based bonuses (high risk).

If wealthier individuals have an easier time starting a firm then a positive relationship between wealth and the probability of starting a firm is evidence in itself that there are liquidity constraints (Evans and Jovanovic 1989, p. 819). In the absence of data on individual wealth before starting the firm, we use assets of the nascent firm as a proxy to measure and control for wealth effects—per Evans and Jovanovic (1989). This measure is consistent with the fact that there is often little distinction between personal wealth and the assets of the young entrepreneurial firm. In fact, from a lender’s perspective, the corporate veil is indeed thin for new firms, with owner's personal assets often being used as collateral for firm loans.

While the interdisciplinary literature on entrepreneurship refers to the process of starting a firm as: firm start-up, entry, the entrepreneurial decision, the entry decision, self-employment, etc., we will hereinafter use the term entry to denote this process.

From discussions with entrepreneurs, we found that for accounting and tax reasons, some entrepreneurs chose to take their compensation in the form of a salary. In examining the data, there were two cases in which salaried part-time entrepreneurs received SBIR grants and five cases where full-time entrepreneurs were recipients.

See Elston et al. (2005) for details on the series of experimental tasks that generated this data.

In fact we elicit individual CRRA intervals rather than use ones predicted by statistical models, so the CRRA measures are not subject to sampling error in this context.

Empirical studies use different measures to proxy for the importance of wealth. For example, Evans and Jovanovic (1989) use assets, wages, and earnings as proxies for individual wealth. Kan and Tsai (2006) use personal assets, and Georgellis et al. (2005) rely on the reported inheritance of individuals.

Since our experiments were one shot, we do not have the option of lagging variables over time to control for the potential endogeneity of independent variables.

In a related study on part-time entrepreneurs, Levesque and Schade (2005) examine how entrepreneurs divide time between working a wage job and working in their newly formed firm.

Entrepreneurs who also held salaried positions outside of their entrepreneurial firm are still classified as entrepreneurs as opposed to salaried non-entrepreneurs; in estimations we found that if we pool the two types of entrepreneurs, the data simply exhibit a wider variance in risk attitudes.

For details, see Elston et al. (2005).

Note when r = 1, U(y) = ln(y).

One can speculate that since secondary jobs are generally less common in Europe that this may negatively impact the ability of Europeans entrepreneurs to finance new firms.

An alternative interpretation is that while neither Race nor Age are statistically significant, they are almost significant in the model without control variables, which may indicate that the age of the entrepreneur has a potentially positive impact and being non-Caucasian has a potentially negative impact on the probability of starting a firm.

Wessner (2002).

The data on gifts and inheritance were pooled into one variable because there were too few observations on gifts.

References

Bates, T. (1990). Entrepreneur human capital inputs and small business longevity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72(4), 551–559.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Meyer, B. (1994). A longitudinal analysis of young entrepreneurs in Australia and the United States. Small Business Economics, 6(1), 1–20.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. G. (1998). What makes an entrepreneur? Journal of Labor Economics, 16, 26–60.

Branscomb, L. M., & Auerswald, P. A. (2002). Between invention and innovation: An analysis of funding for early-stage technology development. NIST GCR 02-841 (p. 23). Gaithersburg, MD: NIST.

Cressy, R. (2000). Credit rationing or entrepreneurial aversion? An alternative explanation for the Evans and Jovanovic finding. Economic Letters, 66, 235–240.

de Meza, D., & Webb, D. C. (1987). Too much investment: A problem of asymmetric information. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 102, 281–292.

Douglas, E., & Shepherd, D. (2002). Self-employment as a career choice: Attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions, and utility maximization. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26, 81–90.

Elston, J. A., Harrison, G., & Rutström, E. E. (2005). Characterizing the entrepreneur using field experiments. Discussion paper, Department of Economics, College of Business Administration, University of Central Florida. http://cebr.dk/upload/harrison.pdf.

Evans, D. S., & Jovanovic, B. (1989). An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), 808–827.

Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1989a). Some empirical aspects of entrepreneurship. American Economic Review, 79(3), 519–535.

Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1989b). The determinants of changes in U.S. self-employment. Small Business Economics, 1(2), 11–120.

Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1990). Small business formation by unemployed and employed workers. Small Business Economics, 2(4), 319–330.

Georgellis, Y., Sessions, J., & Tsitsianis, N. (2005). Windfalls, wealth, and the transition to self-employment. Small Business Economics, 25, 407–428.

Hart, O., & Moore, J. (1994). A theory of debt based on the inalienability of human capital. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(4), 841–879.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. The American Economic Review, 92, 1644–1655.

Jaffe, D. M., & Russell, T. (1976). Imperfect information, uncertainty and credit rationing. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 90, 651–666.

Kan, K. K., & Tsai, W. (2006). Entrepreneurship and risk aversion. Small Business Economics, 26, 465–474.

Keh, H. T., Foo, M. D., & Lim, B. C. (2002). Opportunity evaluation under risky conditions: The cognitive processes of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 125–148.

Levesque, M., & Schade, C. (2005). Intuitive optimizing: Experimental findings on time allocation decisions with newly formed ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 313–342.

Palich, L. E., & Bagby, D. R. (1995). Using cognitive theory to explain entrepreneurial risk-taking: Challenging conventional wisdom. Journal of Business Venturing, 10, 425–438.

Parker, S. (2004). The economics of self-employment and entrepreneurship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parker, S. (2005). The economics of entrepreneurship: What we know and what we don’t. Discussion papers on entrepreneurship, growth, and public policy #1805. The Max Planck Institute for Research into Economic Systems.

Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (1992). The benefits of firm-creditor relationships: Evidence from small business data. University of Chicago working paper #362.

Stiglitz, J., & Weiss, A. (1981). Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. American Economic Review, 71, 393–410.

Wessner, C. (Ed.). (2002). The small business innovation research program: Challenges and opportunities. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Maria Minniti and Christian Schade for discussions on the material contained in this study. Elston thanks the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation for research support under grant no. 20070378.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elston, J.A., Audretsch, D.B. Financing the entrepreneurial decision: an empirical approach using experimental data on risk attitudes. Small Bus Econ 36, 209–222 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9210-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9210-x

Keywords

- Entry

- Experimental data

- High-technology entrepreneurs

- Liquidity constraints

- Personal capital

- Risk attitudes

- SBIR