Abstract

This paper delves into a facet of socioeconomic diversity relatively unaddressed in the literature: student reports of cross–class interaction (“reported CCI”). Previous research has found that student interaction across social class is a significant predictor of cross–racial interaction, but it is unknown whether the actual socioeconomic heterogeneity of a student body is significantly related to reported CCI. We use hierarchical linear modeling to identify predictors of reported CCI in the 2003 Freshman/2007 College Student Survey from the UCLA Higher Education Research Institute. In the final model, students who attended more socioeconomically diverse institutions and more racially diverse institutions reported higher levels of CCI. Findings suggest that reported CCI is linked to the actual socioeconomic heterogeneity of a student body. Measures of racial diversity (percent of students of color and diversity engagement), both at the institutional and student level, also predicted reported CCI. Thus, reported CCI is likely influenced by the racial diversity of a student body and other aspects of the campus racial climate, in addition to socioeconomic diversity. Implications for campus climate, diversity, and equity research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In recent years, social class has received increased attention in higher education circles. There is growing awareness regarding the extreme underrepresentation of low-income students in elite institutions (Carnevale and Rose 2003), and as the cost of higher education continues to escalate, many are concerned at how low-income students will fare both in access and retention (St. John 2003). As state and federal support dwindles for education and financial aid, public institutions are looking for ways to recruit more students who can pay full or out-of-state tuition, as opposed to being more aggressive about outreach to low-income students. A recent survey of senior admissions officers noted: “Recruiting more “full-pay” students—those who don’t need financial aid—is seen as a key goal in public higher education, a sector traditionally known for its commitment to access” (Inside Higher Education 2011). In a stratified higher education system, low-income students are increasingly more likely to access higher education through two-year institutions and the for-profit sector (Bailey et al. 2005; Bastedo and Jaquette 2009). These trends cut across race, as the proportion of Black, Latino/a, and Asian American from low-income backgrounds attending four-year institutions has dropped over the last 35 years (Chang et al. 2007; Allen et al. 2005; Hurtado et al. 2008).

Although some elite institutions have bolstered financial aid for low-income students, critics note that these policies are more likely to benefit middle or upper-middle income students because low-income students may not apply to such institutions in the first place (The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education 2009). Low-income students are less likely to attend highly resourced high schools and may not have access to adequate high school counseling (Deil-Amen and Tevis 2010; McDonough 1997). The high cost of tuition may deter them from applying to college in the first place, even if they are eligible for financial aid (McDonough and Calderone 2006). The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (2009) found that

…at 25 of the 30 highest-ranked universities the percentage of the student body that came from low-income families declined from 2004 to 2007… this was in a period when these universities had revamped their financial aid programs to make them more attractive to low-income students.

Drops in Pell Grant recipients were particularly pronounced at institutions such as the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Southern California, where the percentages dropped by 4.7 and 7.2 percentage points, respectively. Thus, just as institutions struggle to attract racial/ethnic diversity, numerous institutions also struggle to attract and retain socioeconomic diversity (Carnevale and Rose 2003).

Little knowledge exists regarding the ramifications of a lack of socioeconomic diversity in an institution. In a recent study (Park et al. 2013) found that students who reported interacting with those of different economic backgrounds (a term they dubbed “cross–class interaction” or “CCI”) and students who attended institutions with higher average levels of reported CCI were more likely to engage in cross–racial interaction and diversity activities, even when the racial diversityFootnote 1 of the institution was held constant. They suggested that CCI may play a role in supporting the campus racial climate by facilitating a more fluid environment with less rigid social boundaries where students are more likely to interact across race. However, are student reports of interacting across social class actually contingent on having a socioeconomically diverse student population? This study examines how reported CCI varies by an institution’s racial diversity and student engagement with racial diversity; it also investigates whether the socioeconomic heterogeneity of the student body is significantly associated with reported CCI once demographic and institutional variables are controlled for.

Background and Literature

Engagement with racial diversity is associated with a myriad of educational and civic benefits such as leadership skills, commitment to civic engagement, interracial friendship, and bias reduction (Park 2012; Bowman 2011; Jayakumar 2008). However, racial diversity is not the only type of diversity that exists on a college campus. In recent years, researchers have addressed different forms of diversity, including diversity related to religion, sexual orientation, and social class (Cole and Ahmadi 2010). Little research addresses whether engagement with other forms of diversity (i.e. religious, socioeconomic, etc.) is associated with educational benefits in the way that racial diversity is. However, in a recent study (Park et al. 2013) found that students with higher reported CCI had significantly higher levels of cross–racial interaction, as well as greater engagement with curricular and co-curricular diversity-related activities. An institution’s average reported CCI and average cross–racial interaction were correlated at 0.61, indicating that the two constructs are related but not interchangeable.

This previous study was the first to see if there was any sort of benefit associated with reported CCI, but previous research points to several reasons for why socioeconomic status (SES) has implications for student engagement with racial diversity. First, lower-income students of all races are less likely to participate in fraternities and sororities, which are associated with lower rates of cross–racial interaction and interracial friendship (Sáenz 2010; Stearns et al. 2009). Second, SES appears to influence the racial and socioeconomic composition of students’ peer groups: A study with a national sample of students from selective institutions found that lower and middle-income students were more likely to interact across race than their higher income peers (Espenshade and Radford 2009). Similarly, a study of a liberal arts college found that White affluent students had the most racially homogeneous friendship groups, while lower income White and Black students had more racially diverse friendship groups (Aries 2008). Park et al. (2013) suggested that these patterns may occur because lower-income White students are more likely to attend racially diverse high schools, an environment associated with higher pre-college dispositions for cross–racial interaction and engagement with diversity-related activities (Hall et al. 2011; Locks et al. 2008).

Third, greater socioeconomic diversity may influence engagement with racial diversity by making it more likely that students of different races will hold relative equal status. Allport (1954) proposed that positive intergroup contact is dependent on equal status, institutional support, and the pursuit of common goals. When institutions lack racial diversity, relative equal status is threatened because students of color are more likely to experience marginalization and/or tokenization (Park 2013). Relative equal status may also be threatened in cases when institutions lack both racial and socioeconomic diversity (for example, when the majority population is not only White, but White and affluent) because racial inequality is likely exacerbated by overlapping socioeconomic inequality (Park et al. 2013), making it less likely that students will share relative equal status. However, in combination with racial diversity, socioeconomic diversity in a student body may bolster relative equal status among students, thus facilitating intergroup contact. Altogether these studies indicate that lower and possibly middle-income students tend to have more interactions across race than their more affluent peers, and that greater socioeconomic diversity in a student body may facilitate interactions across race. Given findings that reported CCI is a significant predictor of cross–racial interaction and engagement with diversity activities, it is possible that students who interact across class backgrounds are also those who interact across racial lines more often. However, we know little about the demographic and experiential factors that are linked to reported CCI. Much in the way that earlier researchers had to investigate whether having racial diversity in a student body is necessary for cross–racial interaction to occur (Chang 1999), in this study we ask whether having a socioeconomically diverse student body is a necessary pre-condition for students to report engaging in CCI.

Significance

Much of the concern regarding the challenges facing low-income students comes from a social justice or equity perspective. Low-income students are notably underrepresented in selective institutions of higher education (Bastedo and Jaquette 2009; Carnevale and Rose 2003). Most selective institutions have extremely low percentages of Pell Grant recipients, and the numbers have grown little despite increased commitments to financial aid at numerous institutions (Supiano and Fuller 2011). As some have noted, it seems inequitable that wealth should unduly influence educational prospects and pathways in a higher education system that prides itself on facilitating social mobility (McDonough 1997). Such inequities also counter meritocratic sensibilities which posit that the best and brightest should be awarded for their achievement, regardless of their station in life (Kahlenberg 2010).

While we share these concerns, we are curious to know more about what socioeconomic diversity in a student body does for campus learning environments and campus climate. Is socioeconomic diversity just a noble cause, or are there actually educational benefits associated with it? This study is critical because it adds to our understanding of whether and how socioeconomic diversity contributes to an institution’s campus climate for diversity and overall learning environment. The question of whether socioeconomic diversity is linked to reported CCI is critical to address in order to establish whether students’ reported CCI is more a matter of perception, or if it is actually linked to the demographic conditions of an institution. While students’ self-reports are inevitably somewhat inconsistent (Bowman 2010), CCI is potentially even more difficult for students to gauge than cross–racial interaction. Identifying peers’ SES may be even more difficult given the numerous complex factors that contribute to SES, and the ability of students to mask SES or pass for a member of a different social class (Aries 2008). While these limitations confine the potential generalizability of our research, they also signify the need for a study that examines whether reported CCI is significantly related to the actual demographic socioeconomic composition of the student body. Thus, this study will investigate whether reported CCI is linked to the actual socioeconomic diversity of a student body, helping inform our understanding of how socioeconomic diversity and CCI potentially influence institutional learning environments.

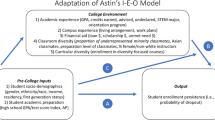

Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis

In theorizing that greater socioeconomic diversity in a student body is related to higher reports of CCI, we rely on the work of Allport (1954), who stipulated that healthy intergroup contact between minority and majority group members is contingent on the following: relative equal status, institutional support, and the pursuit of common goals. Within the college setting, we propose that these conditions are necessary for higher levels of reported CCI. In this study, we use “structural socioeconomic diversity” (SSD), a measure of the socioeconomic diversity of the student body, as a measure of both institutional support for CCI and relative equal status. We hypothesize that institutions with greater levels of SSD will have higher reports of CCI.

Given that attending a selective university is increasingly the domain of the wealthy (Carnevale and Rose 2003), institutions with greater amounts of socioeconomic diversity, as represented by SSD, likely have some commitment towards recruiting and supporting a critical mass of lower income students. In doing so, they signal an institutional commitment to supporting a socioeconomically diverse student body, which helps facilitate higher reported CCI. Furthermore, greater SSD likely facilitates greater relative equal status between students. As noted before, relative equal status is likely threatened when institutions lack not just racial, but also socioeconomic diversity (Park et al. 2013). We posit that institutions with greater SSD have higher CCI, in part because having both greater socioeconomic and racial diversity contributes to greater relative equal status, which is conducive to intergroup contact. Thus, we hypothesize that students attending institutions with higher levels of SSD will have higher levels of reported CCI, even when background, institutional attributes, and college experiences are controlled for.

Methods

Data Source

We utilized data from the Cooperative Institutional Research Program (CIRP) at the University of California, Los Angeles’ (UCLA) Higher Education Research Institute (HERI): The 2003 Student Information Form (SIF) and the 2007 College Student Survey (CSS). The SIF was administered during registration, orientation, or the first few weeks of the semester to all full-time, first-time entering students in Fall 2003. The purpose of the SIF is to gather students’ background and demographic characteristics, high school characteristics and experiences, financial arrangements, current views and attitudes, and current educational and career aspirations prior to having any substantial experience with college life (for more detailed information about the 2003 SIF, see Sax et al. 2003). In Spring 2007, the CSS was administered to the same students at the end of their fourth year of college, and asked them about their various college experiences over the past four years. The CSS focuses on a range of college student experiences, such as academic engagement and achievement, cognitive and affective development, current views and attitudes, current educational and career aspirations, and other post-college plans. The CSS can be administered as a “stand-alone” survey, a follow-up survey to the SIF (as was done here), and sometimes a follow-up survey to the Your First College Year (YFCY) survey. Response rates were not available to us due to the nature of both survey administrations, however, interested readers can obtain more detailed information on the 2003 SIF and 2007 CSS from Sax et al. (2003), Spinosa et al. (2008) respectively.

The initial sample consisted of 15,231 students nested within 102 institutions. All variables were examined for accuracy of data entry, plausible value ranges, and missing values. Only one variable had more than 5 % missing data (5.3 % missing). We only excluded students who had missing data on gender (5 students) or race (156 students). We also excluded students from institutions with fewer than 20 respondents (95 students). Then, we utilized the expectation maximization (EM) method which uses maximum likelihood (ML) estimates to replace missing data for the continuous variables (Allison 2002). The final sample consisted of 14,975 students nested within 89 institutions. Of the 89 institutions, 7 (8 %) were public institutions, and 82 (92 %) were private institutions. Of the 14,975 students, 9,114 (61 %) were female and 5,861 (39 %) were male. In terms of race, 12,259 (82 %) were White/Caucasian, 932 (6 %) were Asian American, 779 (5 %) were Latino/a, 502 (3 %) were African American, 141 (1 %) were American Indian, and 362 (2 %) reported their race as “other.”

Key Variables

For this study, our dependent variable was reported cross–class interaction (CCI) which was represented by an item asking students the extent to which they interacted with “students from a different economic background” (1 = never to 5 = very often). The principal independent variables of interest represent institutional socioeconomic diversity (“structural socioeconomic diversity,” SSD) and institutional racial diversity. SSD was represented by the percentage of students receiving any financial aid (i.e. federal, state/local, or institutional grant aid) which was obtained from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) enrollment figures. This variable was recoded into an inverted U shaped variable to reflect the heterogeneity and maximum opportunity for inter-class contact. On one end of the continuum, institutions with 0 or 100 % of students receiving aid were recoded into low scores. On the other end, institutions with 50 % of students receiving aid were recoded into high scores.Footnote 2 This index is conceptually similar to Chang and Yamamura’s (2006) “Diversity Heterogeneity” index for racial diversity in that it does not assume that one particular group (i.e. White students in the case of racial diversity, or students receiving financial aid in the case of socioeconomic diversity) will always be the largest grouping on every campus. Reported CCI was more strongly correlated with structural socioeconomic diversity (r = 0.10) as compared to structural racial diversity (r = 0.08).

Institutional racial diversity was represented by three variables: structural racial diversity, aggregated curricular/co-curricular diversity engagement (hereafter referred to as “diversity engagement”), and aggregated cross–racial interaction. Structural racial diversity was represented by the institutional percentage of students of color, that is, the combined proportional representation of Asian Americans, African Americans, American Indians, and Latino/as. We utilized this measure because the dataset we received did not contain the percentage of students for each racial/ethnic group in order to protect the anonymity of participating institutions. While there are a number of different ways to calculate structural racial diversity, all of them are highly correlated with one other; furthermore, the percentage of students of color is the most highly correlated with the frequency of cross–racial interaction (see Chang and Yamamura 2006). Aggregated diversity engagement and aggregated cross–racial interaction were represented by the institutional averages of diversity engagement and cross–racial interaction, respectively. The student-level diversity engagement and cross–racial interaction variables are described below.

Although we were interested primarily in the effect of institutional context, we also included student-level variables related to socioeconomic and racial diversity. Specifically, we included parental education and income, concern financing college, diversity engagement, and cross–racial interaction. Parental education was the average of father’s and mother’s education level (1 = grammar school or less to 8 = graduate degree), and parental income was represented by one item asking students about the best estimate of their parents’ total income last year (1 = less than $10,000 to 14 = $250,000 or more). Concern financing college was one item asking students at the beginning of college how concerned they were about financing college (1 = none, I am confident that I will have sufficient funds to 3 = major, I am not sure I will have enough funds to complete college).

Diversity engagement was represented by an index of three items that asked students if they had participated in the following activities (0 = no; 1 = yes): taken an ethnic studies course, attended a racial/cultural awareness workshop, or participated in an ethnic/racial student organization since entering college. Cross–racial interaction was an average of five items on the survey that asked students about the extent to which they had interacted with students from each of the following groups: White/Caucasian, African American/Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian American/Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic/Latino. For each student, we created an average score to represent the frequency with which they interacted with all the other racial groups excluding their own (1 = never to 5 = very often). Cross–racial interaction was more strongly correlated with structural racial diversity (r = 0.27) as compared to structural socioeconomic diversity (r = 0.05). We also included other key control variables representing characteristics, predispositions, and college experiences of students that, unless taken into account, could influence the outcomes and cause an overestimation of the effects of socioeconomic and racial diversity. For example, we included variables such as prior experiences with diversity, parents’ education and income, concerns about financial matters, employment during college, and political orientation (see the Appendix for the full list of variables).

Analytic Approach

We utilized both descriptive and hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) analyses. We used descriptive analyses to explore variations in reported CCI across gender, race/ethnicity, and parents’ education and income. We then used HLM (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002) to examine the effects of socioeconomic and racial diversity on reported CCI. Prior to running the HLM analyses, we standardized all continuous variables and mean-centered all dichotomous variables to reduce multicollinearity and simplify the interpretation of the coefficients, that is, the unstandardized coefficients are analogous to standardized coefficients (Cohen et al. 2003). The student-level variables were the level-1 predictors, and the institution-level variables were the level-2 predictors. We conducted three HLM analyses in which SSD was modeled simultaneously with each one of the three institutional racial diversity variables (i.e. structural racial diversity, average diversity engagement, and average cross–racial interaction). We modeled the institutional racial diversity variables one at a time due to possible multicollinearity of the three racial diversity variables. While two of the three intercorrelations were below 0.32, the correlation between structural racial diversity and average cross–racial interaction was 0.72. We then conducted a fourth HLM analysis in which SSD was modeled simultaneously with all three of the racial diversity variables.

The fully unconditional model (i.e. no predictors) provides preliminary information about how much variation in the outcome lies within and between institutions (see Eqs 1 and 2).

Level-1:

where i = 1, 2,…,n j students in institution j, and j = 1, 2,…, j institutions. In Eq. 1, each student’s value on the outcome measure (Y ij ) is a function of his or her institutional average on the outcome measure (β 0j ) and a random effect (r ij ) unique to each individual. The r ij represents random error, which is normally distributed with a mean of zero and variance σ 2. The variance of the random effects (σ 2) represents the within-institution variance.

Level-2:

In Eq. 2, the institutional average on the outcome measure (β 0j ) is a function of the grand mean on the outcome measure for all institutions (γ 00 ) and a random effect (u 0j ) unique to each institution. The random effect u 0j is normally distributed with a mean of zero and variance τ 00 . The variance of the random effects (τ 00 ) represents the between-institution variance.

The conditional model which contains both student-level (level-1) and institution-level (level-2) predictors (see Eqs. 3 and 4). All level-1 predictors have been group-mean centered and all level-2 predictors have been grand-mean centered. Thus, the intercept (β 0j ) represents the institutional average on the outcome measure (i.e., unadjusted mean) for institution j.

Level-1:

In the Level-2 model, the intercept (β 0j ) was specified as random, while all other coefficients were specified as fixed.

Level-2:

Limitations

An inherent limitation of the study is our use of secondary data and the use of a single-item dependent variable. The CIRP and CSS surveys are designed to measure the multi-faceted nature of students’ college experiences. There were multiple items regarding student engagement with diversity activities (3 items) and interracial contact (5 items), but only one item related specifically to experiences with inter-class contact. We recognize that it would be ideal to combine multiple items to capture the various facets of CCI, but were limited by the existing data. Obviously, cross–class interaction is more complex and nuanced than this one item, and future studies would benefit by considering a more stable measure or a multiple-item measure that can more accurately capture cross–class interaction. Similarly, at the institution-level we were only able to include one measure of socioeconomic diversity, SSD. We also recognize that the SSD measure that we were able to include, i.e. heterogeneity of students receiving aid, can only begin to capture the complex concept of socioeconomic diversity. Future studies can consider additional ways of operationalizing various facets of socioeconomic diversity. There were also some generalizability limitations of this study, due to skew of institutions favoring private institutions (i.e. 92 % of institutions and 94 % of students in our sample) and the sample consisting only of four-year colleges and universities (i.e. no two-year colleges included). Future studies would benefit by including two-year colleges, as cross–class interaction may quite well look different in community colleges. Despite these limitations however, this study makes some important contribution as one of the first few studies to measure any sort of socioeconomic diversity at an institutional level. As an initial exploration of socioeconomic diversity, it will yield insights to inform future studies.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

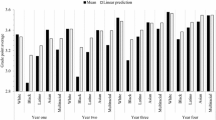

The dependent variable of reported CCI ranged from a minimum of 1 (never) to 5 (very often). For the descriptive analyses only, we categorized the student respondents into four groups: very low interaction (combining ‘never’ and ‘seldom’; 8 % of the sample), low interaction (‘sometimes’; 20 % of the sample), medium interaction (‘often’; 34 % of the sample), and high interaction (‘very often’; 39 % of the sample). Table 1 shows the frequency distribution of reported CCI into the very low, low, medium, and high interaction by gender, race/ethnicity, and parents’ education and income. There are slight differences between males and females in reported CCI [χ 2 (3, N = 14,975) = 18.17, p < 0.0001], with female students reporting interacting slightly more frequently across social class as compared to male students. There are also significant differences across race/ethnicity [χ 2 (15, N = 14,975) = 141.04, p < 0.001]. Native American students are most likely to interact ‘very often’ across social class, followed by African American, Latino/a, and ‘other’ race students. Asian American and White students are less likely to report interacting ‘very often’ across social class and most likely to interact ‘never’, ‘seldom’, or ‘sometimes’ across social class as compared to the other student groups. In terms of parents’ education and income, while there are no significant differences in reported CCI across parents’ education [χ 2 (12, N = 14,975) = 11.32, p = ns], there are significant differences in perceptions of CCI across parents’ income [χ 2 (12, N = 14,975) = 108.36, p < 0.001]. Students from low-income families are more likely to interact across social class as compared to students from higher income families.

Table 2 presents the frequency distribution of reported CCI by gender, race/ethnicity, and parents’ education while controlling for income. Disaggregating the frequencies of reported CCI by these background characteristics, while controlling for income, shows some differing patterns. At lower income levels, there were some significant differences in reported CCI across gender, race/ethnicity, and parents’ education. Specifically, when parents’ income was less than $50,000, there were significant differences in reported CCI across race/ethnicity [χ 2 (15, N = 2,711) = 54.87, p < 0.001], but no differences across gender [χ 2 (3, N = 2,711) = 5.27, p = ns] or parents’ education [χ 2 (12, N = 2,711) = 11.31, p = ns]. When parents’ income was between $50,000 and $100,000, there were significant differences in reported CCI across gender [χ 2 (3, N = 5,442) = 17.81, p < 0.001], race/ethnicity [χ 2 (15, N = 5,442) = 59.75, p < 0.001], and parents’ education [χ 2 (12, N = 5,442) = 25.60, p < 0.05]. At higher income levels, however, there were no significant differences in reported CCI across gender, race/ethnicity, and parents’ education. Specifically, when parents’ income was between $100,000 and $150,000, there were no significant differences in reported CCI across gender [χ 2 (3, N = 3,022) = 2.79, p = ns], race/ethnicity [χ 2 (15, N = 3,022) = 12.78, p = ns], and parents’ education [χ 2 (12, N = 3,022) = 14.92, p = ns]. Similarly, when parents’ income was $150,000 and greater, there were no significant differences in reported CCI across gender [χ 2 (3, N = 3,800) = 2.79, p = ns], race/ethnicity [χ 2 (15, N = 3,800) = 16.95, p = ns], and parents’ education [χ 2 (12, N = 3,800) = 16.36, p = ns]. Thus, these preliminary descriptive statistics illustrate that there is more variation in reported CCI at lower family income levels, but less variation in reported CCI at higher income levels.

HLM Analyses

Table 3 presents the findings of the HLM analyses with structural racial diversity (Model 1), average diversity engagement (Model 2), and average cross–racial interaction (Model 3) modeled individually with SSD. At the institution-level, the findings show some beneficial effects of socioeconomic diversity and each form of racial diversity. Specifically, SSD, reflecting the socioeconomic heterogeneity of a student body, is positively associated with higher reported CCI in two of the three models (and is marginally significantly positive in the third model). The findings also show that two of the three racial diversity variables have a significant positive effect on reported CCI. That is, attending a campus that is more structurally (racially) diverse (γ05 = 0.01, t = 3.81) or a campus with higher average levels of diversity engagement (γ06 = 0.07, t = 3.18) are both associated with higher reported CCI.

Table 3 also presents the findings of the combined model for CCI with structural racial diversity, average diversity engagement, and average cross–racial interaction modeled simultaneously (last column on the right). In regards to the institution-level effects, SSD (γ05 = 0.02, t = 2.01), structural racial diversity (γ05 = 0.01, t = 3.09), and average levels of diversity engagement (γ06 = 0.08, t = 2.93) are all significant positive predictors of reported CCI. So, students who attend more racially diverse institutions, institutions where the students as a whole are engaged in more diversity activities, and more socioeconomically diverse institutions tend to also report more frequent interactions across social class. Higher average levels of CCI, however, had no effect on individual students’ reports of CCI. One possible interpretation for this finding is that a more structurally (racially) diverse student body, as compared to a student body that interacts more frequently across race, is a better predictor of reported CCI.

In terms of student-level effects, parental income is a significant negative predictor of reported CCI (γ80 = −0.06, t = −4.41). Both diversity engagement (γ160 = 0.04, t = 4.10) and cross–racial interaction (γ170 = 0.37, t = 34.77) are significant positive predictors of reported CCI. In other words, curricular/co-curricular diversity engagement and cross–racial interaction are both associated with higher reported CCI. Also, cross–racial interaction in high school (γ100 = 0.05, t = 7.18) and predicted cross–racial interaction in college (γ110 = 0.06, t = 5.65) are both significantly positively associated with reported CCI. Students with a more liberal political orientation (γ140 = 0.03, t = 3.28) and a higher high school GPA (γ90 = 0.03, t = 3.83) also had higher reported CCI as compared to those with a more conservative orientation and lower high school GPA, respectively.

In terms of race/ethnicity, African American students (γ20 = −0.08, t = −2.48), American Indian students (γ30 = −0.14, t = −2.06), Asian American students (γ40 = −0.16, t = −3.64), Latino students (γ50 = −0.08, t = −2.66), and “other” race students (γ60 = −0.13, t = −3.10) are all less likely to report frequent interactions across social class as compared to White students. Given these unexpected findings, we re-ran the HLM analyses to explore the complicated nature of these relationships. Specifically, we included gender and race/ethnicity in the first step. We then added in the other student-level variables one at a time in subsequent steps to examine the ways in which the additional variables affected the relationship between race/ethnicity and reported CCI. In the first step, the coefficients for African Americans, American Indians, Latino/as, and “other” race are all significantly positive while the coefficient for Asian Americans is non-significant. In other words, African-American, American Indian, Latino/a, and “other” race students report more frequent interactions across social class as compared to White and Asian American students. In the step where curricular/co-curricular diversity engagement enters the model, the coefficient for African Americans, American Indians, Latino/as, and “other” race students becomes non-significant and the coefficient for Asian Americans becomes significantly negative. So, the reason for the attenuated effects in this step is because these groups of students (i.e. generally all underrepresented minorities except for Asian Americans) are more likely to participate in curricular/co-curricular diversity activities in college. Similarly, when college cross–racial interaction enters the model, the coefficients for African Americans, American Indians, Latino/as, and “other” race students all become significantly negative, meaning that these underrepresented minority students are all more likely to interact across racial lines as compared to White students, which further explains the sign change in their coefficients. Thus, the seemingly lower reports of CCI by African American, American Indian, Latino/a, and “other” race students is attributed to the fact that they are all more likely to engage in diversity activities and interact more frequently across racial lines. So when their engagement with diversity activities and cross–racial interactions is controlled for, it appears that they have lower levels of reported CCI than do White students, which is incorrect: In fact, the opposite is true.

Discussion

This study contributes to the debate regarding whether there are benefits associated with socioeconomic diversity in the way that there are with racial diversity. Specifically, our findings show that students who attend socioeconomically diverse institutions and more racially diverse institutions are more likely to report more frequent interactions across class lines. Multiple measures of racial diversity, both at the institutional and student level, are significantly related to reported CCI, showing how reports of CCI are likely influenced by the racial composition of a student body and aspects of the campus racial climate. In particular, percent students of color, SSD, and institutional level diversity engagement are significant predictors of reported CCI, as well as individual students’ levels of cross–racial interaction and diversity engagement.

Notably, SSD was a significant institution-level predictor, suggesting that reported CCI is not just a subjective perception, but an estimation that reflects the actual socioeconomic heterogeneity of a student body. This finding is also corroborated by the simple correlation between SSD and reported CCI. It appears that students are unlikely to report interacting with students of different socioeconomic backgrounds if there are not students of different social classes in the student body. While this conclusion is a statement of the obvious, our study is the first to examine and document this phenomenon using rigorous statistical methods and a robust national, longitudinal sample. Our findings are entirely novel and illustrate how there are benefits associated with both socioeconomic and racial diversity, and that the benefits of both types of diversity are distinct and exist independently of one another. Most importantly, the findings highlight how both racially diverse institutions and socioeconomically diverse institutions contribute uniquely to student reports of interacting more frequently across class lines.

Findings also lend further support to the use of Allport’s (1954) contact theory in higher education studies. Greater socioeconomic and racial heterogeneity are both linked to reported CCI, possibly because having greater levels of both types of diversity likely facilitates relative equal status between students and also reflects greater institutional support for diversity. Having a student body that is both racially and socioeconomically diverse appears to break down some of the social barriers to interaction on campus, and also is likely reflective of a commitment to supporting students of different socioeconomic backgrounds. Future studies, both qualitative and quantitative, are needed to elucidate these phenomena. Also needed are more quantitative studies with multiple measures of socioeconomic diversity. Since this study utilized secondary data analysis, a more focused, mixed-methods study could provide a more nuanced picture of the complex relationships between racial and socioeconomic diversity and their differing and complementary influences on more robust measures of cross–class interaction. Just as there are a variety of ways to measure structural racial diversity (e.g. Chang and Yamamura 2006), there are a number of differing ways to measure and operationalize both CCI and SSD. Thus, future research should also examine the differing ways in which various measures of SSD influences actual CCI, and even how CCI can affect other student outcomes. Future studies should also examine a broad range of institutional types to include community colleges and public institutions, as well as historically black colleges and universities and Hispanic-serving institutions. By examining the entire range of institutions can we truly understand what influences students to interact across social class lines across a variety of contexts.

Conclusion and Implications

Overall this study breaks ground by showing that the actual socioeconomic heterogeneity of a student body is linked with higher reported levels of cross–class interaction, a type of diversity engagement that is associated with increased levels of cross–racial interaction and engagement in curricular/co-curricular diversity activities (Park et al. 2013). We found that the relationship between structural socioeconomic diversity and reported cross–class interaction persists even when multiple forms of institutional racial diversity (structural racial diversity, diversity engagement, and cross–racial interaction) are controlled for. Furthermore, we found that structural racial diversity and institutional diversity engagement themselves are significant predictors of reported CCI, indicating that engagement across class lines is linked with elements of the campus racial climate.

Findings point to several implications. First, our findings illustrate the importance of assembling and supporting both racially and socioeconomically diverse student bodies in order to support the overall campus climate for diversity. While a considerable amount of scholarship on the essentialness of recruiting and retaining racially diverse student bodies has emerged (see for example Bowman 2011; Chang et al. 2004; Gurin et al. 2004), work addressing the value of socioeconomic diversity is still emerging. While such work importantly addresses the social justice imperative to promote equity within higher education and provide social mobility for America’s best and brightest, regardless of social class (Kahlenberg 2010), research on how socioeconomic diversity is related to and potentially supports racial diversity in the college environment is still in the early stages. Our study attempts to address this gap by exploring the extent to which the two are interconnected. Further research and public dialogue is needed to help policymakers and educators understand how racial diversity and socioeconomic diversity, while not interchangeable, are deeply interrelated and interdependent phenomena that are both needed to support the campus climate for diversity and a more equitable campus.

Additionally, we want to draw special attention to the need for institutions to prioritize socioeconomic diversity. In a time when income inequality continues to grow in America (Norton and Ariely 2011), a certain class of higher education institutions are growing increasingly out of reach for low-income, working class, and first-generation college students. Not only are elite private institutions largely the domain of the more affluent (Carnevale and Rose 2003), but some public institutions, particularly public flagship institutions, are increasingly attended by out-of-state students who can pay full, out-of-state tuition (Inside Higher Education 2011). Recruiting out-of-state students and also international students may seem appealing in the name of “diversity,” and we agree that such students add to the vibrancy of a student body. However, diversity without equity falls short of the values of higher education institutions, particularly public institutions that have a responsibility to promote access and social mobility for state residents.

Simply increasing financial aid to low-income students has not resulted in marked enrollments at many institutions (The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education 2009; Supiano and Fuller 2011). One of the main reasons for this is that college choice decisions are not simply a rational linear process, but is complicated by numerous factors such as cultural and social capital, families, insider knowledge, political contexts, access to resources, institutional agents, and peer networks (Park and Eagan 2011; McDonough 1997; Perna 2006). Boosting socioeconomic diversity will not come from simply allocating more resources to financial aid, although this step is essential. Also important is understanding low-income students’ sense of belonging and other factors related to retention and success, as some researchers have investigated (Ostrove and Long 2007; Walpole 2008). While there are no easy answers, we hope that the findings of our study will encourage institutions to understand that fostering both equity and diversity adds uniquely to an institution’s campus climate and overall learning environment.

Notes

We recognize that much of the research actually examines “racial/ethnic diversity,” but for the sake of simplicity, we refer to “racial diversity” in the remainder of the paper.

We tested various iterations of the SSD variable, with differing “peaks” at 40, 50, 60, 70, and 80 %. We then correlated each of these different inverted-U shaped variables with CCI to examine which one was associated with the most CCI. The correlations showed that institutions with 50 % of students receiving aid were associated with the most frequent student reports of interactions across class.

References

Allen, W. R., Jayakumar, U. M., Griffin, K. A., Korn, W. S., & Hurtado, S. (2005). Black undergraduates from Bakke to Grutter. Los Angeles: UCLA Higher Education Research Institute.

Allison, P. D. (2002). Missing data. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Aries, E. (2008). Race and class matters at an elite college. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Bailey, T., Jenkins, D., & Leinbach, T. (2005). What we know about community college low-income and minority student outcomes: Descriptive statistics from national surveys. New York: Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center.

Bastedo, M. & Jaquette, O. (2009). Institutional stratification and the fit hypothesis: Longitudinal shifts in student access. Paper presented at the annual conference of the Association for the Study of Higher Education. Vancouver, Canada.

Bowman, N. A. (2010). Can first-year college students accurately report their learning and development? American Educational Research Journal, 47, 466–496.

Bowman, N. A. (2011). Promoting participation in a diverse democracy: A meta-analysis of college diversity experiences and civic engagement. Review of Educational Research, 81, 29–68.

Carnevale, A. P., & Rose, S. J. (2003). SES status, race/ethnicity, and selective college admissions. New York: The Century Foundation.

Chang, M. J. (1999). Does racial diversity matter?: The educational impact of a racially diverse undergraduate population. Journal of College Student Development, 40(4), 283–301.

Chang, M. J., Astin, A. W., & Kim, D. (2004). Cross–racial interaction among undergraduates: Some causes and consequences. Research in Higher Education, 45, 527–551.

Chang, M. J., Park, J. J., Lin, M. H., Poon, O. A., Nakanishi, D. (2007). Beyond myths: The growth and diversity of Asian American college freshmen, 1971–2005. Los Angeles: UCLA Higher Education Research Institute.

Chang, M. J., & Yamamura, E. (2006). Quantitative approaches to measuring student body diversity: Some examples and thoughts. In W. Allen, M. Bonous-Hammarth, & R. T. Teranishi (Eds.), Higher education in a global society: Achieving diversity, equity and excellence (pp. 369–386). Oxford: Elsevier.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cole, D., & Ahmadi, S. (2010). Reconsidering campus diversity: An examination of Muslim students’ experiences. Journal of Higher Education, 81(2), 121–139.

Deil-Amen, R., & Tevis, T. L. (2010). Circumscribed agency: The relevance of standardized college entrance exams for low SES high school students. The Review of Higher Education, 33, 140–170.

Espenshade, T. J., & Radford, A. W. (2009). No longer separate, not yet equal: Race and class in elite college admission and campus life. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gurin, P., Dey, E., Gurin, G., & Hurtado, S. (2004). The educational value of diversity. In P. Gurin, J. Lehman, & E. Lewis (Eds.), Defending diversity: Affirmative action at the University of Michigan (pp. 97–188). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hall, W. D., Cabrera, A. F., & Milem, J. F. (2011). A Tale of two groups: Differences between minority students and non-minority students in their predispositions to and engagement with diverse peers at a predominantly White institution. Research in Higher Education, 52, 420–439.

Hurtado, S., Saenz, V. B., Santos, J. L., & Cabrera, N. (2008). Advancing in higher education: A portrait of Latina/o college freshmen at four-year institutions, 1975–2006. Los Angeles: UCLA Higher Education Research Institute.

Inside Higher Education (2011). Clashes of money and values: A survey of admissions directors. Inside Higher Education. http://www.insidehighered.com/news/survey/admissions2011. Accessed 1 Oct 2011.

Jayakumar, U. M. (2008). Can higher education meet the needs of an increasingly diverse and global society? Campus diversity and cross-cultural workforce competencies. Harvard Educational Review, 78(4), 615–651.

Kahlenberg, R. (2010). Rewarding strivers: Helping low-income students succeed in college. Washington, DC: Century Foundation.

Locks, A. M., Hurtado, S., Bowman, N. A., & Oseguera, L. (2008). Extending notions of campus climate and diversity to students’ transitions to college. Review of Higher Education, 31(3), 257–285.

McDonough, P. M. (1997). Choosing colleges: How social class and schools structure opportunity. Albany: SUNY.

McDonough, P. M., & Calderone, S. (2006). Perceptual differences between college counselors and low-income families about college costs and financial aid. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(12), 1703–1718.

Norton, M. I., & Ariely, D. (2011). Building a better America: One wealth quintile at a time. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 9–12.

Ostrove, J. M., & Long, S. M. (2007). Social class and belonging: Implications for college adjustment. The Review of Higher Education, 30(4), 363–389.

Park, J. J. (2012). When race and religion collide: The effect of religion on interracial friendship in college. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 5(1), 8–21.

Park, J. J. (2013). When diversity drops: Race, religion, and affirmative action in higher education. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Park, J. J., Denson, N., & Bowman, N. (2013). Does socioeconomic diversity make a difference? Examining the effects of racial and socioeconomic diversity on the campus climate for diversity. American Educational Research Journal.

Park, J. J., & Eagan, M. K. (2011). Who goes early? A multi-level analysis of enrollment via early action and early decision admissions. Teachers College Record, 113(11), 2345–2373.

Perna, L. W. (2006). Studying college choice: A proposed conceptual model. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. XXI, pp. 99–157). Cambridge: Springer.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Sáenz, V. (2010). Breaking the segregation cycle: examining students’ precollege racial environments and college diversity experiences. The Review of Higher Education, 34(1), 1–37.

Sax, L. J., Lindholm, J. A., Astin, A. W., Korn, W. S., Saenz, V. B., & Mahoney, K. M. (2003). The American freshman: National norms for fall 2003. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA.

Spinosa, H., Sharkness, J., Pryor, J. H., & Liu, A. (2008). Findings from the 2007 administration of the College Senior Survey (CSS): National aggregates. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA.

St. John, E. (2003). Refinancing the college dream. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Stearns, E., Buchmann, C., & Bonneau, K. (2009). Interracial friendships in the transition to college: Do birds of a feather flock together once they leave the nest? Sociology of Education, 82, 173–195.

Supiano, B., & Fuller, A. (2011). Elite colleges fail to gain more students on Pell Grants. Chronicle of Higher Education. http://chronicle.com/article/Pell-Grant-Recipients-Are/126892/.

The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (2009). Disappointing progress in enrollments of low-income students at America’s most selective colleges and universities. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. http://www.jbhe.com/features/61_lowincome.html. Accessed 1 Oct 2011.

Walpole, M. (2008). Emerging from the pipeline: African American students, socioeconomic status, and college experiences and outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 49(3), 237–255.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme [DP1094417].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J.J., Denson, N. When Race and Class Both Matter: The Relationship between Socioeconomic Diversity, Racial Diversity, and Student Reports of Cross–Class Interaction. Res High Educ 54, 725–745 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9289-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9289-4