Abstract

This study empirically investigates the association between institutional ownership composition and accounting conservatism. Transient (dedicated) institutional investors, holding diversified (concentrated) portfolios with high (low) portfolio turnover, focus on portfolio firms’ short-term (long-term) perspectives and trade heavily (generally do not trade) on current earnings news. Thus, I predict that as transient (dedicated) institutional ownership increases, firms will exhibit a lower (higher) degree of accounting conservatism. Consistent with my predictions, in the context of asymmetric timeliness of earnings, I document that as the level of transient (dedicated) institutional ownership increases, earnings become less (more) asymmetrically timely in recognizing bad news.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

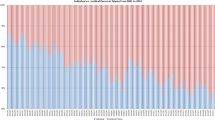

Institutional ownership of common stock has increased significantly over the past few decades. According to the Federal Reserve Board’s Flow of Funds report, institutional investors owned about 7 % of U.S. stocks in 1950 and 67 % in 2005. This increasing dominance in the equity markets contrasts with our limited understanding of the role institutional investors play in influencing accounting conservatism. In this study, I examine the association between institutional ownership composition and accounting conservatism, in an attempt to shed some light on this relation.

Accounting conservatism arguably benefits the users of financial statements by curbing managers’ opportunistic payments to themselves, mitigating agency problems in the context of managerial investment decisions, increasing debt contracting efficiency, and reducing litigation costs (Watts 2003a, b; Ball and Shivakumar 2005). Corporate governance can provide a structure that helps ensure that the assets of the firm are used efficiently, and not inappropriately distributed to managers at the expense of other stakeholders. In light of the arguable benefits of accounting conservatism, it is expected that participants in efficient corporate governance will regard conservatism as a desirable characteristic of accounting information and will favor its implementation. This assertion is supported by a paper by García Lara et al. (2009). They document that firms with stronger corporate governance exhibit a higher degree of accounting conservatism, using the takeover-protection index developed by Gompers et al. (2003) and board structure as the proxies for corporate governance.

In this study, I focus on institutional investors, as they are generally seen as playing a critical role in corporate governance—monitoring managers through explicit actions or “voting with their feet.” Activism by institutional investors generally consists of two categories. The first category takes the form of shareholder proposals. Since the mid-1980s, institutional investors have made shareholder proposals under rule 14a-8 (Kahan and Rock 2007), which usually pertain to various aspects of corporate governance. The second category takes the form of private discussions with company management and board members. Institutional investors have increasingly relied on private negotiations to persuade boards to initiate governance changes voluntarily and have only turned to formal proposals when boards failed to do so (Kahan and Rock 2007).

As activism by institutional investors is costly and the benefits of accounting conservatism are more likely to be reaped in the long run, not all institutional investors will equally engage in strengthening corporate governance and promoting accounting conservatism. Bushee (1998) classifies institutional investors into three categories based on their portfolio diversification and turnover: transient institutional investors, who hold diversified portfolios with high turnover; dedicated institutional investors, who hold concentrated portfolios with low turnover; and quasi-indexers, who hold diversified portfolios with low turnover. All institutions face a cost-benefit analysis with regards to influencing corporate governance and promoting accounting conservatism.

By definition, transient investors hold stocks for short periods of time; they have fewer incentives to invest in monitoring and thus influence corporate governance. Transient institutions act as “traders” rather than “owners,” and thus they are less likely to reap the long-term benefits of accounting conservatism when compared to dedicated institutions. Moreover, transient institutional investors prefer current earnings to long-term earnings and prefer to sell shares in firms whose current earnings are under-performing (e.g., Bushee 1998, 2001; Porter 1992). The focus of transient investors on short-term earnings may create implicit incentives for managers to engage in less conservative financial reporting practice, as conservative financial reporting (for example, timely recognition of losses) may result in missing analyst forecasts, which may trigger institutions selling shares. Heavy institutional selling can create downward pressure on stock prices (Brown and Brooke 1993).

Managers are concerned about institutional selling and negative stock price reaction, as firms’ current earnings and stock price performance affect managers’ compensation. Dikolli et al. (2009) document that in determining CEO cash bonuses, firms with high levels of transient investors tend to place less weight on earnings and more weight on annual returns. Their results suggest that transient investors’ trading behavior creates implicit incentives for CEOs to increase current earnings, and firms consider these implicit incentives when formulating CEO compensation contracts. In other words, transient investors create implicit incentives for managers to delay recognition of bad news, or to recognize bad news in a smaller-scale fashion, thus resulting in less conservative financial reporting. Hence, I predict that as the level of transient institutional ownership increases, firms will be associated with a lower degree of accounting conservatism.

Conversely, dedicated institutional investors do not trade on short-term price movement. For example, Ke and Ramalingegowda (2005) find evidence that transient institutions, but not dedicated and quasi-indexing institutions, exploit the post earnings announcement drift (PEAD).Footnote 1 Similarly, Ali et al. (2008) find that dedicated investors generally do not trade around earnings announcements. Furthermore, Bushee (2001) finds that only transient—but not long-term—institutional investors exhibit a preference for near-term earnings. Taken together, dedicated institutional investors are not fixated on current earnings performance. They act as “owners,” focus on the long-term perspective of the firm, and are more likely to reap the long-term benefits stemming from accounting conservatism.

From the perspective of costs related to monitoring managers, the longer an institution has invested in a firm, the better its access to managers and the lower its monitoring costs. Dedicated institutional investors will have lower costs and larger benefits in the long run when promoting accounting conservatism. The existing literature shows that dedicated institutional investors are actively involved in corporate governance. For example, Chen et al. (2007) document that independent institutions with long-term investment horizons focus on monitoring rather than trading.Footnote 2 Given dedicated investors’ active involvement in corporate governance and the relation between corporate governance and accounting conservatism (García Lara et al. 2009), I expect that as the level of dedicated institutional ownership increases, firms will be associated with a higher degree of accounting conservatism.

As for quasi-indexers, by definition, these investors hold diversified portfolios with low turnover. It is uncertain whether these investors will attempt to pursue monitoring effort. Moreover, the existing literature finds that quasi-indexers do not trade on current earnings news. For example, Ke and Ramalingegowda (2005) find evidence that dedicated and quasi-indexing institutions do not exploit the post earnings announcement drift (PEAD). Therefore, this study does not focus on the relationship between ownership by quasi-indexers and accounting conservatism.

In this study, I examine the association between institutional ownership composition and conditional accounting conservatism, in the context of asymmetric timeliness of earnings.Footnote 3 Asymmetric timeliness of earnings, the conditional form of accounting conservatism, is proposed by Basu. Basu (1997) defines conservatism as the requirement of stricter verification criteria for recording good news as gains in financial reporting than recording bad news as losses. Basu (1997) documents that conservative firms are characterized by greater timeliness of earnings with regards to bad news than with regards to good news, a phenomenon referred to as asymmetric timeliness of earnings. Therefore, in the context of asymmetric timeliness of earnings, I expect to document that as the level of transient (dedicated) institutional ownership increases, earnings become less (more) asymmetrically timely in recognizing bad news.

Following LaFond and Roychowdhury (2008), I run Fama and MacBeth (1973) regressions to carry out the asymmetric timeliness of earnings test.Footnote 4 I find that as the level of transient ownership increases, firms exhibit a lower degree of asymmetric timeliness of earnings, and that as the level of dedicated institutional ownership increases, firms report earnings that are significantly timelier in recognizing bad news. In summary, the regression results are consistent with my predictions that as the level of transient (dedicated) institutional ownership increases, firms will be associated with a lower (higher) degree of accounting conservatism.

My study has potential contributions in the following ways. First, this paper adds to the literature by investigating the association between institutional ownership and accounting conservatism in light of the increasing dominance of institutional investors in the stock markets. Second, this study examines the association between institutional ownership and accounting conservatism, taking into account the heterogeneity of institutional investors. Examining total institutional ownership ignores important variations among different types of institutional investors. Third, this paper complements recent research on the relation between corporate governance and accounting conservatism, in that institutional investors are generally regarded as a critical component of corporate governance.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the conceptual development. Section 3 contains the hypothesis development. Section 4 presents the research design. Section 5 introduces the sample and presents empirical findings. Section 6 presents an additional analysis of asset write-downs. Section 7 discusses robustness checks, Sect. 8 contains other additional analysis, and Sect. 9 concludes the study.

2 Conceptual development

2.1 Accounting conservatism

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Statement of Concepts No. 2 defines conservatism as “a prudent reaction to uncertainty to try to ensure that uncertainties and risks inherent in business are adequately considered” (FASB 1980, Con2-24). FASB Statement No. 2 states that “Prudent reporting based on a healthy skepticism builds confidence in the results and, in the long run, best serves all of the divergent interests that are represented by the Board’s constituents” (FASB 1980, Con2-24).

The accounting literature documents that conservatism can take two different forms (Beaver and Ryan 2005). First, conservatism can be unconditional, implying that accounting numbers reflect the lowest value among the possible alternatives for assets. A clear example of unconditional conservatism would be the immediate expensing of research and development costs. Therefore, unconditional conservatism is news-independent.

Second, conservatism can be conditional, implying that book values are written down under certain unfavorable circumstances but not written up under favorable situations (Beaver and Ryan 2005). For example, accounting for impairment of long-lived assets requires those assets be written down when their book value is greater than the undiscounted sum of their future cash flows, but not be written up in the opposite scenario. Therefore, conditional conservatism is news-dependent.

The essential difference between these concepts is that unconditional conservatism represents a decrease in earnings regardless of the nature of concurrent economic outcome, while conditional conservatism contains information, and thus is useful in contracting.Footnote 5 Asymmetric verification standards curb managers’ opportunistic payments to themselves, given that the earnings management literature suggests that managers have incentives to expedite the recognition of good news and to postpone or hide bad news as their compensation is linked to reported earnings, and they have limited horizons.

This paper focuses on conditional conservatism, as it plays a clear role in the contracting and monitoring functions of corporate governance, given that dedicated institutional investors are a key component of corporate governance. Moreover, conditional conservatism is more suitable than unconditional conservatism when it comes to testing the relation between transient institutional ownership and accounting conservatism, as transient investors’ trading behavior is most sensitive to current earnings news, i.e., news-dependent.

Empirically, researchers have investigated conditional conservatism in accounting (1) in the context of both public companies and private companiesFootnote 6; (2) across countriesFootnote 7; (3) in association with debtFootnote 8; (4) in relation to managerial ownershipFootnote 9; and (5) in the context of corporate governance.

In the context of corporate governance, several studies are particularly relevant to my paper. Beekes et al. (2004) examine the link between accounting quality, measured by earnings timeliness and earnings conservatism, and the percentage of outside directors on the board of U.K. firms.Footnote 10 They document that firms with a higher percentage of outside directors recognize bad news on a timelier basis. Their results are confirmed by Ahmed and Duellman (2007), who document for a U.S. sample that the proportion of inside directors is negatively associated with conservatism, and that the proportion of outside directors’ shareholdings is positively associated with conservatism.Footnote 11 In a similar vein, García Lara et al. (2009) find that firms with stronger corporate governance exhibit a higher degree of accounting conservatism. García Lara et al. (2009) only focus on conditional conservatism, and use three different proxies, based on Basu (1997), Ball and Shivakumar (2005),Footnote 12 and Givoly and Hayn (2000).Footnote 13

In summary, these studies investigate the relation between corporate governance and accounting conservatism. These results are consistent with my prediction that as the level of dedicated institutional ownership increases, firms will exhibit a higher degree of accounting conservatism, as dedicated investors are seen as playing a significant role in corporate governance.

2.2 Institutional investor composition

Under Rule 13(f), all institutional investors managing more than $100 million in equity are required to file all equity holdings greater than 10,000 shares or $200,000 in market value with the SEC on a quarterly basis. The Thomson Financial Spectrum database compiles SEC Form 13F filings of institutional holdings. Under Spectrum’s classification, institutional investors are labeled based on their legal type: bank, insurance company, investment companies and managers, investment advisors,Footnote 14 and all others (pension funds, university endowments, foundations).Footnote 15 However, within these classifications of manager type, there are likely to be significant differences in investment horizons and trading strategies.

Bushee (1998) documents these variations and classifies institutional investors into three categories based on their portfolio diversification and turnover: transient institutional investors, who hold diversified portfolios with high turnover; dedicated institutional investors, who hold concentrated portfolios with low turnover; and quasi-indexers, who hold diversified portfolios with low turnover.Footnote 16 His results show that within each legal type, there are significant differences in investment horizons and trading strategies. For example, within the legal type of insurance company, 11.6 % (221 out of 1,901) of them are classified as dedicated investors; 64.8 % (1,232 out of 1,901) of insurance companies fall into the category of quasi-indexers per Bushee (1998); and 23.6 % (448 out of 1,901) of insurance companies are identified as transient investors. Please refer to Appendix 2 for a complete comparison between Spectrum’s legal type and Bushee’s classification.

Bushee (1998) finds that firms with higher transient institutional ownership are more likely to reduce R&D expenditures to reverse an earnings decline. Lin and Manowan (2012) document a positive relation between ownership by transient investors and discretionary accounting accruals. Koh (2007) finds that dedicated investors can mitigate aggressive earnings management, which is associated with transient investors among certain firms. Zheng (2010) documents that transient institutional ownership is positively associated with the performance sensitivity of CEO option grants and that such association does not exist for other types of institutions.

Collectively, the existing literature supports the notion that there is considerable heterogeneity in institutional investor behavior. Not all institutions share the same investment philosophy. Therefore, this study examines the association between institutional ownership and accounting conservatism, taking into account the heterogeneity of institutional investors.

3 Hypothesis development

In this section, I first establish the relation between transient institutional ownership and accounting conservatism. I then establish the relation between dedicated institutional ownership and accounting conservatism.

3.1 Transient institutional investors and accounting conservatism

To establish the relation between transient institutional ownership and accounting conservatism, two notions have to be supported: (1) transient institutional investors trade on current earnings news, and (2) managers react to this type of trading.

First, to support the notion that transient investors trade on current earnings news, I note that Bushee (1998) finds that transient investors’ trading behavior is most sensitive to current earnings news, compared to other types of investors. Ke and Ramalingegowda (2005) document that transient investors trade to exploit the post-earnings announcement drift (PEAD). They find that the quarterly change in transient ownership is positively related to the contemporaneous quarter’s earnings surprise.

Second, to support the notion that managers react to this type of trading, I note that Bushee (1998) finds that firms with higher transient institutional ownership are more likely to reduce R&D expenditures to reverse an earnings decline. Matsumoto (2002) shows that firms with higher transient ownership are more likely to meet analyst forecasts, which provides further evidence that managers do react to the trading by transient investors.

Managers try to avoid missing analyst forecasts, as missing forecasts (under-performance) trigger institutions selling shares.Footnote 17 Heavy institutional selling can create downward pressure on a stock price (e.g., Brown and Brooke 1993). Selling by institutional investors might be interpreted as bad news, thus possibly triggering sales by other investors and dragging down the stock price. As noted above, transient investors are most sensitive to current earnings news, and thus firms with higher transient ownership are likely to experience more negative stock market reactions. This rationale is supported by the extant literature. For example, Hotchkiss and Strickland (2003) document that institutional ownership composition is related to the market reaction to a negative earnings announcement. When reported earnings miss analyst forecasts, the stock price response is more negative for firms dominated by momentum or aggressive growth investors.Footnote 18

Taken together, transient institutional investors trade on current earnings news and managers react to this type of trading. Furthermore, Dikolli et al. (2009) find that firms with high levels of transient investors place less weight on earnings and more weight on annual returns. Their results suggest that transient investors’ trading behavior creates implicit incentives for CEOs to increase current earnings, and compensation committees account for these implicit incentives when designing CEO compensation contracts. These findings are in line with the assertion that transient investors create implicit incentives for managers to delay recognition of bad news, and thus resulting in less conservative financial reporting. Therefore, I predict that as the level of transient institutional ownership increases, firms will exhibit a lower degree of accounting conservatism. Stated formally:

Hypothesis H1

As the level of transient institutional ownership increases, firms will exhibit a lower degree of accounting conservatism.

3.2 Dedicated institutional investors and accounting conservatism

To establish the relation between dedicated institutional ownership and accounting conservatism, three assertions have to be supported: (1) institutional investors are a key component of corporate governance; (2) dedicated institutional investors are actively involved in corporate governance; and (3) corporate governance is related to accounting conservatism.Footnote 19

First, to support the assertion that institutional investors are a key component of corporate governance, I note that Ferri and Sandino (2009) document that shareholder proposals to expense employee stock options (ESO) affected accounting and compensation decisions. Specifically, targeted firms were relatively more likely to adopt ESO expensing, and CEO pay decreased in firms where the proposal was approved relative to control firms. Given that shareholder proposals are an important category of activism by institutional investors, these findings reveal an increasing influence of institutional investors on corporate governance.

Second, to support the assertion that dedicated institutional investors are actively involved in corporate governance, I note that Chen et al. (2007) show that only concentrated holdings by independent long-term institutions are related to post-merger performance, when they use acquisition decisions to capture monitoring. Additionally, Dong and Ozkan (2008) document in a U.K. setting that dedicated institutions curb the level of director pay and increase the pay-performance sensitivity. This is consistent with the notion that dedicated (long-horizon) institutional investors are more involved in corporate governance and serve a better monitoring role than other short-horizon institutional investors.

Third, to support the assertion that corporate governance is related to accounting conservatism, I note that García Lara et al. (2009) find that firms with stronger corporate governance exhibit a higher degree of accounting conservatism. This assertion is also supported by Ahmed and Duellman (2007), who document that the proportion of inside directors is negatively linked to conservatism, and the proportion of outside directors’ shareholdings is positively linked to conservatism.

Taking together, I predict that as the level of dedicated institutional ownership increases, firms will exhibit a higher degree of accounting conservatism. Stated formally:

Hypothesis H2

As the level of dedicated institutional ownership increases, firms will exhibit a higher degree of accounting conservatism.

4 Research design

4.1 Measurement of institutional ownership

I use Bushee’s (1998) classification methodology to compute transient/dedicated institutional ownership as a percentage of total shares outstanding (TRA/DED).Footnote 20 I measure institutional ownership at the end of a firm’s third fiscal quarter. The reasons are as follows: (1) Bushee (1998) suggests that at the end of a firm’s third quarter, managers are more likely to have a clear picture of their year-end earnings position in the fourth quarter.Footnote 21 Following Bushee (1998), Koh (2007) also measures institutional ownership at the end of firms’ third fiscal quarter when examining the relation between institutional investor type and earnings management.Footnote 22 (2) As institutional investors are required to file Form 13F within 45 days after the end of each calendar quarter,Footnote 23 which makes it possible that before the fiscal year ends, when recording real asset write-downs or making myopic investment decisions, managers will incorporate the most recent information on institutional ownership (i.e., at the end of the third fiscal quarter). Therefore, in light of the existing literature and SEC regulations, I measure institutional ownership at the end of firms’ third fiscal quarter.

When conducting empirical tests, I measure institutional ownership using the scaled decile rank. Specifically, following LaFond and and Roychowdhury (2008), the scaled decile rank is determined by first ranking observations (per each institutional investor classification) into 10 groups from zero to nine, and then scaling the ranking by nine so that the rank variable falls within the zero-to-one interval. The rank variable is designed to capture the significance of investor presence within each classification, as the impact of each 1 percent increase in the original ownership may be different across different investor groups.

4.2 Measure of accounting conservatism and research models

Basu (1997) defines conservatism as “the accountant’s tendency to require a higher degree of verification to recognize good news as gains than to recognize bad news as losses.” Under conservative accounting, earnings capture bad news faster than good news due to the asymmetric recognition criteria for losses and gains. Basu documents a higher correlation of earnings with negative returns (proxy for bad news) than with positive returns (proxy for good news). Basu’s metric has been employed by many researchers (e.g., Ahmed and Duellman 2007; Kwon et al. 2006), therefore, I also use asymmetric timeliness of earnings to proxy for accounting conservatism. Specifically, I use Basu’s regression as follows (firm and time subscripts are omitted):

where NI is equal to net income before extraordinary items divided by beginning of fiscal year market value of equity. RET is equal to the buy-and-hold return by compounding 12 monthly CRSP stock returns ending 3 months after fiscal year-end. NEG is equal to one if RET is negative, and zero otherwise. Note that by using Eq. (1), I regress annual earnings (NI) on contemporaneous annual returns (RET). β 2 captures the timeliness with regards to positive returns (or good news), and β 3 captures the incremental timeliness of earnings with regards to negative returns (or bad news). The asymmetric timeliness coefficient β 3 captures the magnitude of conditional conservatism.

One-year Basu (1997) specifications are used in my association test with institutional ownership. This minimizes the probability of large changes in institutional ownership during the period over which asymmetric timeliness is measured. As Roychowdhury and Watts (2007) demonstrate, one-year Basu (1997) measures are influenced by the beginning composition of equity value, which is affected by past conditional and unconditional conservatism. Following the extant literature, I address this concern by including a proxy for the beginning composition of equity value, in particular the market-to-book ratio (MB). I do not estimate the asymmetric timeliness regression using cumulative earnings and returns over multiple years, as this modification is more susceptible (relative to one-year measure) to the confounding effect of institutional ownership changes during the period over which asymmetric timeliness is measured.

To assess the association between institutional ownership composition and conditional accounting conservatism, I modify Eq. (1) to include TRA_r and DED_r and the related interaction terms, specifically, \(NEG*TRA\_r\), \(NEG*DED\_r\), \(RET*TRA\_r\), \(RET*DED\_r\), \(RET*NEG*TRA\_r\), and \(RET*NEG*DED\_r\).

Other than market-to-book ratio (MB), I also control for leverage (LEV), firm size (SIZE) and litigation risk (LIT). The reasons are as follows:

-

1.

Leverage. Debt-holders are more concerned about the lower bounds of earnings and net assets and thus favor conservative accounting, which follows that the higher the firm’s leverage ratio, the greater is the creditor demand for accounting conservatism, ceteris paribus.

-

2.

Firm size. Large firms likely face substantial political costs that induce them to report more conservatively (Watts and Zimmerman 1978). Meanwhile, LaFond and Watts (2008) argue that information asymmetry between managers and investors is less severe in larger firms and thus larger firms likely face less demand for conservative financial reporting. Their findings are in line with the information asymmetric effect dominating the political cost effect.

-

3.

Litigation risk. Watts (2003a) argues that as litigation risk is higher for firms that inflate their earnings than firms that deflate their earnings, firms can report financial outcomes conservatively to reduce litigation costs. Firms in a litigation industry are more concerned about litigation costs; therefore, they are expected to exhibit a higher degree of accounting conservatism.

After including control variables and interacting them with RET, NEG, and \(RET*NEG\) respectively, I obtain the following model:

where NI = net income before extraordinary items divided by beginning of fiscal year market value of equity; RET = buy-and-hold return by compounding 12 monthly CRSP stock returns ending 3 months after fiscal year-end; NEG = equal to one if RET is negative, and zero otherwise; TRA_r = the scaled decile rank of percentage of shares outstanding held by transient institutional investors per Bushee (1998); DED_r = the scaled decile rank of percentage of shares outstanding held by dedicated institutional investors per Bushee (1998); MB_r = the scaled decile rank of market-to-book ratio at the beginning of the fiscal year; LEV_r = the scaled decile rank of total debt divided by total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year; SIZE_r = the scaled decile rank of the natural logarithm of market value of equity at the beginning of the fiscal year; LIT = equal to one if a firm is in a litigious industry—SIC codes 2833–2836, 3570–3577, 3600–3674, 5200–5961, and 7370–7374, and zero otherwise.

In Eq. (2), β 14 measures earnings timeliness with regards to good news, and β 21 measures the asymmetric timeliness with regards to bad news. I expect β 22 to take on a negative sign, indicating that earnings become less asymmetrically timely in recognizing bad news as transient institutional ownership increases. I expect β 23 to take on a positive sign, indicating that earnings become more asymmetrically timely in recognizing bad news as dedicated institutional ownership increases.

Turning to control variables, I expect to find a negative coefficient on \(RET*NEG*MB\_r\), as the accounting literature suggests the negative relation between asymmetric timeliness and market-to-book ratio (e.g., Beaver and Ryan 2005). I expect to find a positive coefficient on \(RET*NEG*LEV\_r\), which indicates that the higher the leverage ratio, the greater is the creditor demand for accounting conservatism. I expect to find a negative coefficient on \(RET*NEG*SIZE\_r\), which indicates that the asymmetric timeliness of earnings for larger firms is smaller. Finally, I expect to find a positive coefficient on \(RET*NEG*LIT\), which indicates that firms in a litigation industry exhibit a higher degree of accounting conservatism.

5 Sample selection and empirical results

5.1 Sample selection

Table 1 presents the sample selection procedure and describes the reasons for data loss for the asymmetric timeliness test. My initial sample consists of all active U.S. firms on Compustat over the period 1996 to 2006. I also collect data on stock returns from the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP), and institutional investor holdings (i.e., SEC Form 13f filings) from CDA/Spectrum. Because Bushee’s institutional investor classification is used throughout this study, firms must have this pertinent information to be included for the empirical analysis. The intersection of these databases and the trimming at the most extreme one percentile of variable distributions yield a final sample that is composed of 26,507 firm-year observations representing 3,623 firms.

5.2 Descriptive statistics

Table 2, Panel A reports the descriptive statistics on the dependent and independent variables used in the asymmetric timeliness analysis. The descriptive statistics in Table 2 indicate that mean ownership by transient institutional investors is 14.4 %, while mean ownership by dedicated institutional investors is 6.3 %, which indicates the greater presence of transient institutional investors in general. The average buy-and-hold return in my sample is 17.1 %, which is close to 16.3 % reported by LaFond and Roychowdhury (2008). The descriptive statistics on the negative return indicator variable, NEG, indicate that 39.3 % of the sample experiences a negative buy-and-hold return over the 12 months ending 3 months after the fiscal year-end.

Panel B of Table 2 presents the Pearson correlation matrix among the variables. NI is significantly positively correlated with RET (0.17) and negatively correlated with NEG (−0.21), indicating that reported earnings reflect some portion of the information reflected in returns. Panel C of Table 2 presents the Spearman rank correlation matrix among the variables. For the above noted variable NI, RET, and NEG, the Spearman rank correlation coefficients are in sign with the Pearson correlation coefficients with a larger magnitude, specifically, 0.31 (the Spearman coefficient) versus 0.17 (the Pearson coefficient), and −0.28 (the Spearman coefficient) versus −0.21 (the Pearson coefficient).

5.3 Regression results

Table 3 reports the association between institutional ownership and conservatism in the context of asymmetric timeliness of earnings using Eq. (2). The coefficient on \(RET*NEG*TRA\_r\) is borderline significant (−0.047 with p value 0.085), while the coefficient on \(RET*NEG*DED\_r\) is significantly positive (0.030 with p value 0.036). These results suggest that as transient ownership increases, earnings become less asymmetrically timely in recognizing bad news. On the other hand, as dedicated ownership increases, earnings become more asymmetrically timely in recognizing bad news. Taken together, more conservative financial reporting standards imposed by dedicated investors counter managers’ implicit incentives induced by transient investors to overstate current earnings by delaying recognition of bad news.

Turning to control variables, the coefficient on \(RET*NEG*LEV\_r\) is borderline significant (0.057 with p value 0.099), indicating a trend in which the higher the leverage ratio, the greater the debt-contracting demand for accounting conservatism. The coefficient on \(RET*NEG*SIZE\_r\) is significantly negative (−0.162 with p value 0.001), consistent with the notion that information asymmetry is less severe in larger firms. The coefficients on \(RET*NEG*MB\_r\) and \(RET*NEG*LIT\) are not significant.

In sum, regression results in Table 3 are in line with my predictions that as the level of transient (dedicated) institutional ownership increases, firms exhibit a lower (higher) degree of accounting conservatism. Regarding transient investors, my interpretation of these results is that they trade on current earnings and sell on bad news, which creates implicit incentives for managers to recognize bad news in a less timely manner. Regarding dedicated investors, my interpretation of these results is that they have long-term investment horizons and are arguably more likely to benefit from accounting conservatism in the long run. Therefore, they promote accounting conservatism in their portfolio firms.

6 Additional analysis

Asymmetric timeliness of earnings indicates that overall the earnings number is timelier in incorporating bad news than good news. In this section, I carry out an additional analysis to explore how financial reporting recognizes bad news in the specific context of asset write-downs. Asset write-downs are recognition of bad news about future cash flows in current earnings. Specifically, firms are required to record asset write-downs when the book value of a long-lived asset is greater than its undiscounted cash flows expected to result from the use and eventual disposition of the asset, and the written-down amount is the difference between the book value and fair value of the asset.

SFAS No. 144, Accounting for the Impairment or Disposal of Long-lived Assets, states: “Estimates of future cash flows used to test the recoverability of a long-lived asset (asset group) shall incorporate the entity’s own assumptions about its use of the asset (asset group) and shall consider all available evidence.” Therefore, the formal accounting standards give managers much discretion concerning asset write-down amounts, and implementation of SFAS No. 144 is influenced by managers’ subjective estimates.

Bunsis (1997) provides evidence of negative stock market reaction to announcements of asset write-offs. More importantly, Bartov et al. (1998) document that only a relatively small stock-price reaction occurs at the time of announcement of write-downs. Substantial stock-price underperformance occurs around later earnings announcements for those firms previously announcing write-downs. As previously noted, managers are concerned about institutional selling and the resulting negative stock price reaction, therefore, as the level of transient institutional ownership increases, firms become less likely to recognize “bad news” in a timely manner, and these firms will either delay the asset write-down recognition, or record a smaller amount of asset write-downs, ceteris paribus.

On the other hand, dedicated institutional investors are not fixated on current earnings performance and are more likely to promote accounting conservatism in their portfolio firms. In the context of asset write-downs, firms recognizing a greater amount of asset write-downs exhibit a higher degree of accounting conservatism, ceteris paribus. Hence, as dedicated institutional ownership increases, firms are more likely to record a greater amount of asset write-downs to adequately consider the uncertainties and risks.

Taken together, I expect to find that in the event of a sales decline, as the level of transient (dedicated) institutional ownership increases, firms will report a lesser (greater) amount of asset write-downs, ceteris paribus.

I run the Tobit model to carry out the asset write-down test.Footnote 24 Following Riedl (2004), I include proxies for economic factors to capture the underlying value of the firm’s assets. To capture macro-economic influence, I include ∆GDP, the percentage change in U.S. Gross Domestic Product from period t − 1 to t. Regarding economic elements in relation to firm-specific changes in asset value, I use ∆SALES and ∆E_p. ∆SALES is the percent change in sales for firm i from period t − 1 to t, and ∆E_p is the change in firm i’s pre-write-off earnings from period t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1. I also include a market-based measure FRET (firm’s stock return, measured over firm’s fiscal year t) as an explanatory variable for reported write-offs, as this measure may reflect market expectations of the firm’s future performance.

This additional analysis is carried out to examine a firm’s discretion in recording asset write-downs to incorporate bad news pertaining to declines in economic values of assets. Therefore, the focus of the analysis is then not on the main effect terms for institution type but rather on the interaction terms with an indicator of bad news. As firms’ sales are directly related to the estimated future cash flows which result from the use of the asset, I use sales declines to proxy for bad news. Therefore, I include a dummy variable DUM_SALES, equal to one if a firm experience a sales decline, and two three-way interaction terms, \(TRA\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\) and \(DED\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\), in the Tobit regression, resulting in Eq. (3):

where WOTA = firm i’s reported pre-tax long-lived asset write-off (computed as a positive amount) for period t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1; ∆GDP = the percentage change in U.S. Gross Domestic Product from period t − 1 to t; ∆SALES = the percent change in sales for firm i from period t − 1 to t; ∆E_p = the change in firm i’s pre-write-off earnings from period t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1; FRET = Firm i’s stock return, measured over firm i’s fiscal year t; TRA_r = the scaled decile rank of percentage of shares outstanding held by transient institutional investors per Bushee (1998); DED_r = the scaled decile rank of percentage of shares outstanding held by dedicated institutional investors per Bushee (1998); DUM_SALES = equal to one if firm i experiences a sales decline during the year t, and zero otherwise.

Negative ∆GDP, ∆SALES, ∆E_p, and FRET are indicative of unfavorable economic situations, implying that firm assets may suffer contemporaneous reductions in value; therefore, I predict a negative correlation between the amount of write-offs and these variables.

I expect to find a negative coefficient on \(\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\), which implies that a larger scale of sales declines will be associated with a greater amount of asset write-offs (coded as a positive amount). Regarding the three-way interaction term, \(TRA\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\), I expect to find a positive coefficient on it, indicating that as transient institutional ownership increases, firms will record a smaller magnitude of asset write-downs in the face of a sales decline, ceteris paribus. Similarly, I expect to document a negative coefficient on \(DED\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\), indicating that as dedicated institutional ownership increases, firms will record a greater amount of asset write-downs in the face of a sales decline, ceteris paribus.

As the first full year data for asset write-downs is available only since 2001 per the Compustat manual (2003), I sample firms starting in fiscal year 2001.Footnote 25 Table 4 presents the sample selection procedure and describes the reasons for data loss for the asset write-down test. After winsorizing at the most extreme one percentile of variable distributions, the final sample is composed of 16,413 firm-year observations representing 3,423 firms.

Table 5, Panel A and Panel B report the descriptive statistics for the asset write-down observations and non-write-down observations respectively. Consistent with prior research, write-down firms exhibit worse financial performance, compared to non-write-down firms, as reflected in lower means and medians for ∆SALES, ∆E_p, and FRET. Panel D presents the Pearson correlation matrix among the variables. Note that all economic elements ∆GDP, ∆SALES, ∆E_p, and FRET are significantly negatively correlated with WOTA, indicating that as underlying economic situations become unfavorable, that is, ∆GDP, ∆SALES, ∆E_p and FRET take on negative values, firms report a greater amount of asset write-downs (WOTA coded as a positive amount). Panel E of Table 5 presents the Spearman rank correlation matrix among the variables. Consistent with the Pearson correlation coefficients, ∆GDP, ∆SALES, ∆E_p, and FRET are significantly negatively correlated with WOTA.

Table 6 reports the association between institutional ownership and conservatism in the context of asset write-downs using Eq. (3). The coefficient on \(TRA\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\) is significantly positive, indicating that as transient institutional ownership increases, firms record a smaller magnitude of asset write-downs in the event of a sales decline, ceteris paribus. The coefficient on \(DED\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\) is insignificant.

Turing to control variables, the coefficients on economic elements (∆GDP, ∆E_p, and FRET) are significantly negative, indicating that as underlying economic situations become unfavorable, firms report a greater amount of asset write-downs. The interpretation of the relation between ∆SALES and write-down amounts should incorporate the coefficient on ∆SALES and that on \(\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\). For simplicity, suppose both TRA_r and DED_r equal zero, i.e., in the bottom decile. When firms experience a sales decline, ∆SALES is significantly negatively correlated to the magnitude of write-downs, as indicated by the sum of the coefficient on ∆SALES (0.015) and that on \(\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\) (−0.092). Therefore, these results are consistent with the notion that as underlying economic situations become unfavorable, firms tend to report a greater amount of asset write-downs.

I also use another proxy for bad news—the change in a firm’s pre-write-off earnings.Footnote 26 Specifically, a dummy variable, DUM_∆E_p, takes on the value of one if a firm experiences a decline in its pre-write-off earnings and zero otherwise. The regression results are reported in Table 7. The coefficient on \(DED\_r*\Delta E\_p*DUM\_\Delta E\_p\) is significantly negative, indicating that as the level of dedicated institutional ownership increases, firms report a greater amount of asset write-downs in the event of a decline in pre-write-off earnings, ceteris paribus.

Taken together, regression results in the aforementioned two tables are consistent with my predictions: (1) as the level of transient ownership increases, firms record a smaller amount of asset write-downs to incorporate bad news (Table 6); and (2) as the level of dedicated ownership increases, firms report a greater amount of asset write-downs to incorporate bad news (Table 7).

7 Robustness tests

I run a number of (untabulated) sensitivity tests to investigate whether regression results are robust to alternative model specifications and variable measurements.

First, I investigate the sensitivity of the results to the inclusion of quasi-indexers. By definition, quasi-indexers hold diversified portfolios with low turnover. They typically follow buy-and-hold strategies. A priori, it is uncertain whether quasi-indexers will pursue monitoring effort. Moreover, the existing literature documents that quasi-indexers are not sensitive to current earnings news. Therefore, it is uncertain whether quasi-indexers will act more as “traders” or “owners.” As a robustness check, I examine the association between transient/dedicated investors and accounting conservatism, while controlling for quasi-indexers’ presence.

Specifically, in the asymmetric timeliness analysis, \(QIX\_r,NEG*QIX\_r\), \(RET*QIX\_r\), and \(RET*NEG*QIX\_r\) are added to Eq. (2). Adding these terms yields the same qualitative results for the \(RET*NEG*TRA\_r\) and \(RET*NEG*DED\_r\) interactions as reported in Table 3. The coefficient on \(RET*NEG*QIX\_r\) is insignificant. In the asset write-down test, \(QIX\_r,QIX\_r*\Delta SALES\), and \(QIX\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\) are added to Eq. (3). Adding these terms yields the same qualitative results for the \(TRA\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\) and \(DED\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\) interactions as reported in Table 6. The coefficient on \(QIX\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\) is insignificant.

Second, I investigate the sensitivity of the results to the alternate measurement of institutional ownership. In the main results, institutional ownership is measured at the end of firms’ third fiscal quarter. As a robustness check, I run regressions using institutional ownership measured over firms’ four fiscal quarters. Regression results of sensitivity tests indicate that the evidence documented in Tables 3 and 6 is robust to this alternate measurement of institutional ownership.

I also measure institutional ownership at the end of firms’ prior fiscal year. Regression results are summarized as follows: (1) in the asset write-down test, this sensitivity test yields the same qualitative results as reported in Table 6; (2) in the asymmetric timeliness test, this sensitivity test yields insignificant results. Note that by using Eq. (2), I regress annual earnings (NI) on contemporaneous returns (RET), with RET calculated by compounding 12 monthly CRSP stock returns ending 3 months after fiscal year-end (t). Therefore, institutional ownership measured at the end of firms’ prior fiscal year (t − 1) may not be in line with returns measured in this fashion. This could possibly explain why the coefficients on \(RET*NEG*TRA\_r\) and \(RET*NEG*DED\_r\) are not significant, when institutional ownership is measured at the end of firms’ prior fiscal year in Eq. (2).

Third, for the asset write-down analysis, I investigate the sensitivity of the results to the inclusion of managers’ reporting incentives. In Eq. (3), I focus on economic elements to capture the underlying value of a firm’s assets. As the earnings management literature suggests, managers may face incentives (e.g., maximizing long-term compensation) to opportunistically report earnings using “big bath” charges or “smoothing.” Therefore, following Riedl (2004), I include two proxies (BATH and SMOOTH) to capture reporting incentives managers may face in recording asset write-downs.Footnote 27 Note that, since the change in pre-write-off earnings (∆E_p) is included as an indicator of firm performance, BATH and SMOOTH will pick up the incremental effect associated with managers’ reporting incentives. As predicted, the coefficient on BATH (SMOOTH) is significantly negative (positive). Adding controls for reporting incentives yields the same qualitative results for the \(TRA\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\) and \(DED\_r*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\) interactions as reported in Table 6.

8 Other additional analysis

In the main tests and robustness checks, the rank variable TRA_r (DED_r) captures within-group presence of each type of investors. It does not directly capture the relative dominance between transient investors and dedicated investors, that is, it does not directly address the across-group dominance. To account for this drawback, I calculate the difference between TRA_r and DED_r. Note that the difference, TRA_DED_dd, is calculated as the scaled decile rank of TRA minus that of DED, indicating that the higher the value, the greater extent to which transient investors dominate dedicated investors.

In untabulated results, I rerun the regressions in Tables 3 and 6 while substituting the measure of transient ownership relative to dedicated ownership (i.e., TRA_DED_dd) in lieu of the individual variables (TRA_r and DED_r). Regarding the asymmetric timeliness of earnings analysis, I find that the coefficient on \(RET*NEG*TRA\_DED\_dd\) is significantly negative, indicating that as transient investors exceed dedicated investors, earnings become less asymmetrically timely in recognizing bad news. These results suggest that as the level of transient ownership exceeds that of dedicated ownership, firms exhibit a lower degree of accounting conservatism.

Regarding the asset write-down analysis, I find that the coefficient on \(TRA\_DED\_dd*\Delta SALES*DUM\_SALES\) is insignificant when the analysis is carried out in the full sample. However, in the subsample of firms experiencing greater than the median value of sales declines, I find that the coefficient on \(TRA\_DED\_dd*\Delta SALES\) is significantly positive, indicating that as the rank difference (TRA_r − DED_r) increases, firms record a smaller amount of asset write-downs.Footnote 28 These results indicate that the dominance effect is more pronounced for firms in severe unfavorable economic situations, that is, experiencing a sales decline greater than the median value. In these situations, write-downs become imminent and the transient investors’ dominance effect manifests itself.

Overall, these results provide evidence on the across-group dominance that as the level of transient ownership exceeds that of dedicated ownership, firms exhibit a lower degree of accounting conservatism.

9 Conclusions

In this study, I examine the association between institutional ownership composition and accounting conservatism. Transient investors trade on current earnings and sell on bad news, and thus create implicit incentives for managers to inflate current earnings and defer recognition of bad news. This results in less conservative financial reporting, as managers are concerned about negative stock price reaction arising from large-scale institutional selling for the sake of compensation and job security. Therefore, I predict that as the level of transient institutional ownership increases, firms will be associated with a lower degree of accounting conservatism.

Dedicated investors are not fixated on current earnings and generally do not trade on current earnings news, as they have long-term investment horizons. Prior research documents that efficient corporate governance results in more conservative financial reporting in light of the long-term benefits arising from accounting conservatism, in the form of lower interest rates and lower present value of tax payments, and thus the higher the firm’s long-term value. Given the notion that dedicated investors are actively participating in corporate governance, I predict that as the level of dedicated institutional ownership increases, firms will be associated with a higher degree of accounting conservatism.

I focus on conditional accounting conservatism and examine it in the context of asymmetric timeliness of earnings. Consistent with my predictions, I find that as the level of transient ownership increases, firms exhibit a lower degree of asymmetric timeliness of earnings, and that as the level of dedicated institutional ownership increases, firms report earnings that are significantly timelier in recognizing bad news.

In summary, this paper adds to the literature by investigating the association between institutional ownership and accounting conservatism, taking into consideration the heterogeneity of institutional investors. The results documented in this paper suggest that examining total institutional ownership overlooks significant variations among institutional investors, as transient and dedicated investors have different investment horizons. This paper also complements recent research on the relation between corporate governance and accounting conservatism, in that institutional investors are generally regarded as playing a critical role in corporate governance. My findings in this paper are in line with the extant literature.

Notes

PEAD refers to the tendency for abnormal returns to drift following earnings announcements in the direction of earnings surprises.

Chen et al. (2007) refine their monitoring measure by intersecting groups of independent long-term institutions with those identified by Bushee’s method as dedicated and quasi-indexer investors. Their results remain unchanged, when they intersect only the dedicated institution sample with the sample of independent long-term institutions with concentrated ownership.

Following Beaver and Ryan (2005), I refer to this news-dependent conservatism as conditional conservatism. Unconditional or news-independent conservatism refers to the understatement of stockholders’ equity as a result of historical accounting and under-recognition of certain assets (Feltham and Ohlson 1995). In this paper, I only focus on conditional conservatism as it plays a clear role in the monitoring functions of corporate governance, of which dedicated institutional investors are a key component. Moreover, conditional conservatism is more suitable than unconditional conservatism when it comes to testing the relation between transient institutional ownership and accounting conservatism, as transient investors’ trading behavior is most sensitive to current earnings news, i.e., news-dependent.

LaFond and Roychowdhury (2008) use the Fama–MacBeth procedure when examining the effect of managerial ownership on financial reporting conservatism, proxied by asymmetric timeliness of earnings; LaFond and Watts (2008) also use the same procedure to investigate the relation between information asymmetry and asymmetric timeliness of earnings; and Huijgen and Lubberink (2005) use the same method to compare asymmetric timeliness of earnings of U.K. companies cross-listed in the U.S. to that of U.K. companies without a U.S.-listing.

Ball and Shivakumar (2005) argue that it is difficult to infer how contracting is affected by unconditional conservatism. If the amount of an unconditional accounting bias is known, rational agents would simply account for the bias. If the bias is unknown, it can only bring noise in financial information and can only decrease contracting efficiency.

For example, Ball and Shivakumar (2005) hypothesize that private company financial reporting is of lower quality due to different market demand. Tests conducted in a large U.K. sample support this hypothesis, in which quality is measured using Basu’s (1997) measure of timely loss recognition and an accruals-based method.

For example, Bushman and Piotroski (2006) analyze relations between key characteristics of country-level institutions and conditional conservatism. They find that firms in countries with high quality judicial systems incorporate bad news in earnings faster than firms in countries with low quality judicial systems.

For example, Wittenberg-Moerman (2008) documents that timely loss recognition reduces the bid-ask spread in the secondary-loan market, which follows that conservative reporting reduces information asymmetry pertaining to a borrower.

For example, Lafond and Roychowdhury (2008) study the effect of managerial ownership on financial reporting conservatism and document a negative association between managerial ownership and asymmetric timeliness of earnings.

Ball and Shivakumar (2005) measure conditional conservatism based on the relation between accruals and cash flows. They argue that the negative relation between earnings and operating cash flows is less pronounced in bad news periods as a result of the asymmetric recognition criteria for losses and gains. Losses are likely to be recorded on a timely basis through unrealized accruals, while gains are recorded when realized and thus recognized on a cash basis.

Givoly and Hayn (2000) measure conservatism based on the accumulation of operating accruals. They find that higher accounting conservatism gives rise to larger negative total accruals. Notice that negative total accruals is a measure of total conservatism, rather than conditional conservatism. García Lara et al. (2009) acknowledge that this measure captures conditional conservatism with some noise.

Mutual funds are included in the Investment Advisor classifications. Generally, mutual funds also manage pension investments on behalf of their clients and are classified on the 13-F as Investent Advisors.

Due to a mapping error, CDA/Spectrum’s type classification is not accurate beyond 1998. Many institutions are inappropriately labeled as Type 5 institutions (all others) (Chen et al. 2007).

The fourth category characterized by concentrated portfolios with high turnover does not exist. Due to transaction costs and liquidity issues, it would be impossible to run a trading strategy that makes highly-frequent trades in large blocks of stock. I thank Professor Brian Bushee for his clarification on this category.

An alternate explanation for managers trying to avoid missing analyst forecasts is offered by Mergenthaler et al. (2009). They find that missing the quarterly analyst earnings forecast results in career penalties, for example, a smaller bonus, decreased equity grants, and a higher possibility of displacement for both CEOs and CFOs.

Momentum investors are determined by studying the stocks purchased, held and sold by each fund manager over six consecutive quarters. Momentum investors exhibit the greatest inclination to buy (sell) stocks with positive (negative) analyst revisions. Momentum investors classified by Georgeson & Co. are similar to transient institutional investors under Bushee’s classification. For example, only 2.9 % of momentum investors are identified to have low turnover (Hotchkiss and Strickland 2003, p. 1477).

Notice that when developing the relation between transient ownership and accounting conservatism, I do not focus on corporate governance. The rational is as follows, as transient investors, by definition, hold stocks for short periods of time, therefore, they have fewer incentives to invest in monitoring and thus influence corporate governance.

I thank Professor Brian Bushee for providing access to the institutional investor classifications used throughout this study.

Bushee (1998) argues that the manager likely has an accurate estimate of annual earnings and starts to consider myopic investment decisions in the middle of the second half of the fiscal year; therefore institutional ownership is measured at the end of firms’ third fiscal quarter.

See http://www.sec.gov/divisions/investment/13ffaq.htm for more information.

The Tobit Model is adopted in the context of asset write-downs, as this model has been adopted in the prior research. For example, Francis et al. (1996) use a Tobit estimation procedure to test the causes and effects of discretionary asset write-offs; Riedl (2004) uses a Tobit model to carry out an examination of long-lived asset write-downs; and Chao and Horng (2013) also use Tobit regressions to carry out tests relating to asset write-offs. The Tobit model is assuming the data is censored. In the context of asset write-downs, the assumed latent variable is the change in the value of the firm’s asset, which can lead to an asset write-down or a write-up. However, U.S. GAAP does not generally allow reporting of asset write-ups, and thus these unobservable (non-reported) asset write-ups make up that portion of the distribution of the censored dependent variable, which the Tobit specification aims to fill in (Riedl 2004). Therefore, in this paper, the dependent variable is left censored at zero.

Specifically, data item 380 (write-downs pretax) is the sum of all write-down special items reported before taxes, which includes impairment of assets other than goodwill and write-down of assets other than goodwill.

Some researchers (e.g., Francis et al. 1996) include a firm’s stock return as an explanatory variable for asset write-downs. However, researchers also document that asset write-downs are an input used by stock market investors to determine firm value (e.g., Elliott and Hanna 1996), which suggests that market-based measures would be endogenous if included as explanatory variables. Meanwhile, researchers find that a firm’s stock decline precedes write-off announcements (e.g., Francis et al. 1996), that the stock market reacts negatively to announcements of asset write-downs (e.g., Bunsis 1997), and that abnormal returns of firms reporting write-offs continue to decline after the announcement by as much as 21 % annually for a two-year period (Bartov et al. 1998). Therefore, a market-based proxy for bad news is susceptible to the confounding time effect before, at the same time as, and after the announcement of asset write-downs. Accordingly, I use accounting-based measures as proxies for bad news.

BATH equals the change in pre-write-off earnings from t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1, when this change is below the median of nonzero negative values, and zero otherwise. SMOOTH equals the change in pre-write-off earnings from t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1, when this change is above the median of nonzero positive values, and zero otherwise. In line with firms taking a “big bath,” I predict a negative correlation between write-downs and BATH. In line with firms engaging in income smoothing, I predict a positive correlation between write-offs and SMOOTH.

In the subsample analysis, dummy variable DUM_SALES and its related interaction terms are left out from Eq. (3), as the subsample consists of firms experiencing greater than the median value of sales declines (−8.6 %).

References

Ahmed AS, Duellman S (2007) Accounting conservatism and board of director characteristics: an empirical analysis. J Account Econ 43(2/3):411–437

Ali A, Klasa S, Li OZ (2008) Institutional stakeholdings and better-informed traders at earnings announcements. J Account Econ 46(1):47–61

Ball R, Shivakumar L (2005) Earnings quality in U.K. private firms: comparative loss recognition timeliness. J Account Econ 39(1):83–128

Bartov E, Lindahl FW, Ricks WE (1998) Stock price behavior around announcements of write-offs. Rev Account Stud 3(4):327–346

Basu S (1997) The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. J Account Econ 24(1):3–37

Beaver WH, Ryan SG (2005) Conditional and unconditional conservatism: concepts and modeling. Rev Account Stud 10(2/3):269–309

Beekes W, Pope P, Young S (2004) The link between earnings timeliness, earnings conservatism and board composition: evidence from the UK. Corp Gov Int Rev 12(1):47–59

Brown K, Brooke B (1993) Institutional demand and security price pressure: the case of corporate spin-offs. Financ Anal J 49(5):53–62

Bunsis H (1997) A description and market analysis of write-off announcements. J Bus Financ Account 24(9/10):1385–1400

Bushee BJ (1998) The influence of institutional investors on myopic R&D investment behavior. Account Rev 73(3):305–333

Bushee BJ (2001) Do institutional investors prefer near-term earnings over long-run value? Contemp Account Res 18(2):207–246

Bushman RM, Piotroski JD (2006) Financial incentives for conservative accounting: the influence of legal and political institutions. J Account Econ 42(1/2):107–148

Chao CL, Horng SM (2013) Asset write-offs discretion and accruals management in Taiwan: the role of corporate governance. Rev Quant Financ Account 40(1):41–74

Chen X, Harford J, Li K (2007) Monitoring: which institutions matter? J Financ Econ 86(2):279–305

Dikolli SS, Kulp SL, Sedatole KL (2009) Transient institutional ownership and CEO contracting. Accont Rev 84(3):737–770

Dong M, Ozkan A (2008) Institutional investors and director pay: an empirical study of UK companies. J Multi Financ Manag 18(1):16–29

Elliott J, Hanna J (1996) Repeated accounting write-offs and the information content of earnings. J Account Res 34(Supplement):135–155

Fama E, MacBeth J (1973) Risk, return, and equilibrium: empirical tests. J Polit Econ 81(3):607–636

Feltham GA, Ohlson JA (1995) Valuation and clean surplus accounting for operating and financial activities. Contemp Account Res 11(2):689–731

Ferri F, Sandino T (2009) The impact of shareholder activism on financial reporting and compensation: the case of employee stock options expensing. Account Rev 84(2):433–466

Francis J, Hanna J, Vincent L (1996) Causes and effects of discretionary asset write-offs. J Account Res 34(supplement):117–134

García Lara JM, García Osma B, Penalva F (2009) Accounting conservatism and corporate governance. Rev Account Stud 14(1):161–201

Givoly D, Hayn C (2000) The changing time-series properties of earnings, cash flows and accruals: has financial reporting become more conservative? J Account Econ 29(3):287–320

Gompers P, Ishii J, Metrick A (2003) Corporate governance and equity prices. Q J Econ 118(1):107–155

Hotchkiss ES, Strickland D (2003) Does shareholder composition matter? Evidence from the market reaction to corporate earnings announcements. J Financ 58(4):1469–1498

Huijgen C, Lubberink M (2005) Earnings conservatism, litigation and contracting: the case of cross-listed firms. J Bus Financ Account 32(7/8):1275–1309

Kahan M, Rock EB (2007) Hedge funds in corporate governance and corporate control. Univ Penn Law Rev 155(5):1021–1093

Ke B, Ramalingegowda S (2005) Do institutional investors exploit the post-earnings announcement drift? J Account Econ 39(1):25–53

Koh PS (2007) Institutional investor type, earnings management and benchmark beaters. J Account Public Policy 26(3):267–299

Kwon SS, Yin QJ, Han J (2006) The effect of differential accounting conservatism on the “over-valuation” of high-tech firms relative to low-tech firms. Rev Quant Financ Account 27(2):143–173

LaFond R, Roychowdhury S (2008) Managerial ownership and accounting conservatism. J Account Res 46(1):101–135

LaFond R, Watts RL (2008) The information role of conservatism. Account Rev 83(2):447–478

Lin L, Manowan P (2012) Institutional ownership composition and earnings management. Rev Pac Basin Financ Mark Polic 15(4). doi:10.1142/S0219091512500221

Matsumoto DA (2002) Management’s incentives to avoid negative earnings surprises. Account Rev 77(3):483–514

Mergenthaler RD, Rajgopal S, Srinivasan S (2009) CEO and CFO career penalties to missing quarterly analysts forecasts. Working Paper, Harvard Business School

Porter M (1992) Capital choices: changing the way America invests in industry. Council on Competitiveness, Harvard Business School, Boston

Riedl EJ (2004) An examination of long-lived asset impairments. Account Rev 79(3):823–852

Roychowdhury S, Watts RL (2007) Asymmetric timeliness of earnings, market-to-book and conservatism in financial reporting. J Account Econ 44(1/2):2–31

Watts RL (2003a) Conservatism in accounting. Part I. Explanations and implications. Account Horiz 17(3):207–221

Watts RL (2003b) Conservatism in accounting. Part II. Evidence and research opportunities. Account Horiz 17(4):287–301

Watts RL, Zimmerman JL (1978) Toward a positive theory of the determination of accounting standards. Account Rev 53(1):112–134

Wittenberg-Moerman R (2008) The role of information asymmetry and financial reporting quality in debt trading: evidence from the secondary loan market. J Account Econ 46(2/3):240–260

Zheng Y (2010) Heterogeneous institutional investors and CEO compensation. Rev Quant Financ Account 35(1):21–46

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on my dissertation at Boston University. I thank my dissertation chairman, Professor Krishnagopal Menon, for his continuous guidance in the development of this paper. I also thank other members of my dissertation committee—Professor Kumar Sivakumar and Professor Jacob Oded—as well as Professor Brian Bushee for providing access to the institutional investor classifications used throughout this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Variable definitions

TRA | ≡ | percentage of shares outstanding held by transient institutional investors per Bushee (1998) |

TRA_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of TRA a |

DED | ≡ | percentage of shares outstanding held by dedicated institutional investors per Bushee (1998) |

DED_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of DED |

QIX | ≡ | percentage of shares outstanding held by quasi-indexers per Bushee (1998) |

QIX_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of QIX |

WOTA | ≡ | firm i’s reported pre-tax long-lived asset write-off (computed as a positive amount) for period t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1 |

∆GDP | ≡ | the percentage change in U.S. Gross Domestic Product from period t − 1 to t |

∆SALES | ≡ | the percent change in sales for firm i from period t − 1 to t |

∆E_p | ≡ | the change in firm i’s pre-write-off earnings from period t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1 |

FRET | ≡ | firm’s stock return, measured over firm’s fiscal year t |

DUM_SALES | ≡ | equal to one if a firm experiences a sales decline during the year t, and zero otherwise |

DUM_∆E_p | ≡ | equal to one if a firm experiences a decline in its pre-write-off earnings during the year t, and zero otherwise |

NI | ≡ | net income before extraordinary items divided by beginning of fiscal year market value of equity |

RET | ≡ | buy-and-hold return by compounding 12 monthly CRSP stock returns ending three months after fiscal year-end |

NEG | ≡ | equal to one if RET is negative, and zero otherwise |

MB | ≡ | market-to-book ratio at the beginning of the fiscal year |

MB_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of MB |

LEV | ≡ | total debt divided by total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year |

LEV_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of LEV |

SIZE | ≡ | the natural logarithm of market value of equity at the beginning of the fiscal year |

SIZE_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of SIZE |

LIT | ≡ | equal to one if a firm is in a litigious industry—SIC codes 2833–2836, 3570–3577, 3600–3674, 5200–5961, and 7370–7374, and zero otherwise |

BATH | ≡ | equal to the change in pre-write-off earnings from t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1, when this change is below the median of nonzero negative values, and zero otherwise |

SMOOTH | ≡ | equal to the change in pre-write-off earnings from t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1, when this change is above the median of nonzero positive values, and zero otherwise |

Appendix 2: Spectrum type by Bushee’s classification

Spectrum type | Bushee’s classification | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

DED | QIX | TRA | Total | Percent | ||

1 | Bank | 563 | 4,373 | 608 | 5,544 | 15.1 |

2 | INS | 221 | 1,232 | 448 | 1,901 | 5.2 |

3 | INV | 131 | 937 | 456 | 1,524 | 4.2 |

4 | IIA | 1,442 | 13,532 | 9,119 | 24,093 | 65.7 |

5 | CPS | 136 | 640 | 181 | 957 | 2.6 |

5 | PPS | 9 | 358 | 47 | 414 | 1.1 |

5 | UFE | 44 | 281 | 73 | 398 | 1.1 |

5 | MSC | 121 | 1,052 | 672 | 1,845 | 5.0 |

Total | 2,667 | 22,405 | 11,604 | 36,676 | 100 | |

Percent | 7.3 | 61.1 | 31.6 | 100 | ||

Spectrum’s type

-

BNK = bank trust (Spectrum type code 1)

-

INS = insurance company (2)

-

INV = investment company (3)

-

IIA = independent investment advisor (4)

-

CPS = corporate (private) pension fund (5)

-

PPS = public pension fund (5)

-

UFE = university and foundation endowments (5)

-

MSC = miscellaneous (5)

Bushee’s classification

-

DED = dedicated institutional investors per Bushee (1998)

-

QIX = quasi-indexers per Bushee (1998)

-

TRA = transient institutional investors per Bushee (1998)

-

Source: http://accounting.wharton.upenn.edu/faculty/bushee/iiclass/desctdqxtc.txt.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, L. Institutional ownership composition and accounting conservatism. Rev Quant Finan Acc 46, 359–385 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-014-0472-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-014-0472-2