Abstract

We examine the effect of capital market pressures for meeting earnings benchmarks on the relationship between R&D spending and CEO option compensation. We consider a particular scenario when firms face small earnings declines but could opportunistically reduce R&D spending to increase reported earnings. We find that firms with income reporting concerns punish their CEOs with lower option compensation when R&D spending increases but reported earnings decreases. Further, for firms with income reporting concerns, we find that the penalty for increasing R&D is greater when the firms frequently miss quarterly earnings benchmarks in the year. Overall, our findings suggest that the adverse consequence on CEO options encourages short-run compensation-motivated actions to eliminate or postpone R&D projects with positive net present values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Prior research has shown that managers engage in earnings management to report income that meets or beats important benchmarks (Burgstahler and Dichev 1997; Degeorge et al. 1999; Dechow et al. 2003). Shedding light on the tools managers use to manage earnings, prior studies focus on accrual-related maneuvers (e.g., DeFond and Park 1997; Payne and Robb 2000; Matsumoto 2002; Burgstahler and Eames 2003; Myers et al. 2007). In contrast, survey evidence indicates that managers would take real economic actions rather than accounting actions to meet short-term earnings benchmarks (Graham et al. 2005). A few studies present evidence of managers’ myopic investment behavior, such as reducing discretionary spending on R&D (e.g., Baber et al. 1991; Dechow and Sloan 1991; Bushee 1998; Roychowdhury 2006). These studies, however, give little attention to the compensation incentives that lead CEOs to take real economic actions for meeting short-term performance targets.

The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), along with the business press, has voiced concerns over questionable business decisions that sacrifice economic value and the insufficiency of current executive compensation plans to provide appropriate managerial incentives (Donaldson 2003). Securities regulators feel that weak corporate governance, especially concerning executive compensation practices, contributes to the corporate crisis in the US. In his 2003 remarks, William H. Donaldson, the former Chairman of the SEC, stated that “The game of earnings projections, and … a firm’s failure to achieve those results created an atmosphere in which ‘hitting the numbers’ became the objective, rather than sound, long-term strength and performance… Many times, … bad or questionable business decisions were rewarded with the afore-mentioned compensation packages that often bore no relationship to what I would call ‘real management performance.’”Footnote 1

In the present study, we examine the effect of capital market pressures for meeting short-term performance targets on the relationship between R&D spending and CEO option compensation. We consider a particular scenario in which firms face small earnings declines but could opportunistically reduce R&D spending to increase reported earnings (i.e., a myopia problem). Specifically, we investigate whether option compensation provides CEOs with incentives to cut R&D to meet or beat earnings benchmarks.

Mace (1986) and Lipton and Lorsch (1992), three of the most active observers of corporate boards, suggest that most outside directors are busy and unable to devote sufficient time to perform their monitoring responsibilities. Along the same lines, the security regulators and business press adopt the increasingly popular view that weak corporate governance due to inadequate board supervision of management leads to ineffective executive compensation schemes. With regard to R&D investments, Graham et al. (2005) suggest that boards are unlikely to see all projects with positive net present value (NPV). They see only the projects that top management are advocating, and therefore, do not have much influence on management investment decisions.

Providing an alternative explanation, recent theoretical studies suggest that the short-term focus of stock-based compensation is not necessarily a sign of weak board governance, but is a reflection of the more short-term orientation of shareholders. Stein (1989) and Bar-Gill and Bebchuk (2003) show that managers make a trade-off between short-term earnings and long-term goals and that earnings management to meet or beat short-term targets is an optimal decision even in a fully efficient market. Consistent with this theory, prior archival research has documented that capital market rewards (punishes) firms for meeting (missing) both annual and quarterly earnings benchmarks (Barth et al. 1999; Bartov et al. 2002; Kasznik and McNichols 2002; Skinner and Sloan 2002; Brown and Caylor 2005).

Furthermore, Bolton et al. (2006) suggest that optimal contracts in a speculative market should emphasize short-term stock performance. When market participants are obsessed with the game of meeting or beating short-term earnings (as observed in the US in the late 90 s), optimal compensation contracts should provide CEOs with incentives to meet short-term performance targets. Such contracts would benefit not only managers and shareholders with short-term horizons who gain from the increased stock prices in the short run, but also shareholders with long-term horizons because the short-term orientation of the market provides a way of reducing the firm’s cost of capital. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that compensation committees would consider meeting short-term earnings hurdles an important aspect of compensation contracts, thereby rewarding CEOs for cutting R&D to reverse an earnings decline and penalizing them for failing to do so.

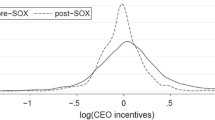

In an interesting recent study, Cheng (2004) finds that changes in CEO option grants are positively associated with changes in R&D spending for firms facing the myopia problem over the period 1984–1997. This suggests that boards reward CEOs for increasing R&D spending while reporting earnings declines. The result is somewhat surprising, given the documented trend that the stock market imposes increasingly severe penalty for missing earnings benchmarks (e.g., Brown and Caylor 2005). Compared to Cheng (2004), we examine the more recent time period (1994–2002) when the stock market focused much more closely on firms’ proclivity to achieve earnings benchmarks (e.g., Brown 2001). It is possible that compensation committees altered their strategy from rewarding managers for undertaking R&D projects toward forgoing the rewards when the firms otherwise would not meet the earnings hurdles.

We also examine whether the association between option compensation and R&D spending for firms facing the myopia problem is conditional on meeting quarterly earnings benchmarks earlier in the year. We expect that the compensation penalty for failing to reverse the declines in annual earnings is more severe when firms have missed quarterly earnings benchmarks than when firms have met the benchmarks earlier in the year. CEOs missing quarterly benchmarks earlier in the year would face greater market pressure to report annual earnings increases, and consequently, have greater incentives to reduce R&D investment than those who regularly meet or beat the quarterly benchmarks.

To date, some studies have documented a negative consequence on CEO cash compensation for missing quarterly earnings benchmarks (e.g., Matsunaga and Park 2001; Shin 2006). However, these studies have not linked missing earnings thresholds to the pressure on managers to sacrifice long-term economic value. Unlike these studies, our study examines a setting in which CEOs face a trade-off between short-term earnings and long-term goals and focuses on CEO option compensation rather than cash compensation. We have this focus for two reasons. First, CEO stock options are arguably better forms of compensation to align the long-term interests of shareholders and managers than are annual cash bonuses. Stock options should encourage management to take real economic actions in an effort to improve long-term firm value. Second, prior research has shown that annual cash bonuses are generally shielded from the income-increasing effects of discretionary spending such as R&D and advertising (e.g., Duru et al. 2002). Moreover, survey evidence suggests that the annual cash bonus is a relatively less important component of CEO compensation compared to stock compensation (Graham et al. 2005).

Based on 2,141 CEO-years representing 543 US R&D-intensive firms, we find that CEOs of firms with income reporting concerns (i.e., the myopia problem) receive lower option grants for failing to reduce R&D spending and thereby reporting an earnings decrease. The penalty for increasing R&D spending on CEO option compensation remains significant after controlling for the determinants of stock option plans suggested by Core and Guay (1999). This finding is consistent with the capital market pressures inducing CEO compensation resolutions in favor of short-term earnings. Furthermore, we find that for firms with the myopia problem, the penalty increases when the firms miss quarterly earnings benchmarks more than once during the year. The incremental penalty tends to persist across alternative earnings benchmarks. These findings are consistent with the level of capital market pressure, and thus the need for an R&D cut, being more pronounced for firms that have missed quarterly benchmarks earlier in the year.

We show that our findings are robust to a number of additional analyses. We find no evidence that increased market pressures induce the penalty for increasing R&D spending for firms without similar income reporting concerns, suggesting that incremental R&D spending does not have an adverse effect on CEO options when meeting short-term earnings goals is irrelevant to the R&D decision. Further, our results are robust to using alternative model specifications, alternative proxies for capital market pressures, and controls for other standard determinants of compensation. Moreover, we find that the penalty on CEO option compensation for increasing R&D is more severe for firms in industries suffering more negative valuation consequences for missing earnings thresholds. In addition, we find that, unlike CEO option grants, CEO cash compensation is largely shielded from the income-decreasing effects of R&D spending, consistent with Duru et al. (2002).

Collectively, our results are consistent with recent survey findings (Graham et al. 2005) that managers do not hesitate to sacrifice discretionary spending which has nontrivial future economic consequences to meet short-term earnings thresholds. Furthermore, compensation committees consider meeting short-term earnings thresholds an important aspect of executive pay packages and would reward CEOs for giving up positive NPV investment projects to meet short-term earnings benchmarks. Our results lend support to the claim that the current compensation policies in corporate America encourage CEOs to sacrifice economic value to avoid short-term earnings disappointments (e.g., Donaldson 2003; Scannell and Lublin 2007). While recent theoretical studies suggest that a compensation scheme focusing on short-term earnings performance is an optimal solution for the contracting problem between shareholder and managers in a speculative market (e.g., Stein 1989; Bar-Gill and Bebchuk 2003; Bolton et al. 2006), our findings indicate that boards of directors may need to reconsider the practice of rewarding CEOs for meeting short-term earnings targets at the expense of long-term firm value.

Our results also complement prior research documenting the relationship between CEO cash compensation and the incidence and frequency of missing quarterly earnings benchmarks (e.g., Matsunaga and Park 2001; Shin 2006). In particular, we show that the penalty for missing quarterly earnings benchmarks pertains to stock-based compensations which are supposedly designed to better align the long-term interests of shareholders and managers.

The next section summarizes the related literature and discusses our hypotheses. Sect. 3 discusses our sample selection procedure and research methods. Sections 4 and 5 present and discuss the empirical results and additional analyses, respectively, and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Background and hypotheses development

The classical view of executive compensation (Mirrlees 1999; Holmstrom 1979; Holmstrom and Tirole 1993) suggests that stock-based compensation schemes are effective forms of incentive schemes for aligning the long-term interests of shareholders and managers. One main hypothesis is that stock prices provide unbiased estimators of firm fundamentals upon which CEO pay could be based. According to this classical view, corporate boards representing the interests of long-term shareholders are expected to set stock-based compensation schemes that provide CEOs with incentives to build long-term firm value. Using a sample of 160 Forbes 500 firms from 1984 to 1997, Cheng (2004) indeed finds that compensation committees prevent potential opportunistic cuts in R&D spending by establishing a positive association between changes in R&D spending and changes in CEO option compensation.

The recent corporate crisis, however, has raised some doubts about the ability of the classical contracting theories to explain the current compensation practices that seem to reward executives for meeting short-term performance at the expense of long-term goals. Regulators and researchers claim that capital market pressure and investors’ overreaction to small earnings misses encourage managerial decisions that at times sacrifice long-term value to meet short-term earnings targets (e.g., Baber et al. 1991; Dechow and Sloan 1991; Bartov 1993; Bushee 1998; Donaldson 2003; Graham et al. 2005; Roychowdhury 2006). Based on their survey of top executives, Graham et al. (2005) suggest that small earnings misses breed uncertainty about a firm’s future prospects, which managers believe hurts stock valuation. Therefore, managers (and shareholders) are willing to make small or moderate sacrifices in economic value to meet the earnings expectations of analysts and investors to avoid the severe market reaction to missing earnings hurdles. While regulators and business press blame weak corporate governance for ineffective compensation practices that reward managers for sacrificing long-term goals to meet short-term earnings targets, recent theoretical research (e.g., Stein 1989; Bar-Gill and Bebchuk 2003; Bolton et al. 2006) offers an alternative explanation. This stream of research suggests that a compensation contract focusing on meeting short-term performance provides an optimal solution for the contracting problem between management and shareholders when investors with short-term horizons dominate the market.

Stein (1989) and Bar-Gill and Bebchuk (2003) show that capital market incentives induce managers to behave myopically to meet short-term earnings benchmarks at the expense of long-term firm value. When the capital market rewards firms for meeting short-term performance, both managers and shareholders would prefer actions that maximize short-term earnings and stock price over long-term strategic actions such as investments in R&D. By pursuing such strategies, both managers and existing shareholders will gain from selling their holdings. Even when managers cannot sell their shares, managers will still maximize short-term performance in order to obtain favorable terms to raise capital for new acquisitions or projects. These theoretical predictions are consistent with the archival studies showing that the capital market rewards (punishes) firms for meeting (missing) quarterly or annual benchmarks (Barth et al. 1999; Bartov et al. 2002; Kasznik and McNichols 2002; Skinner and Sloan 2002; Brown 2001).

Along the same lines, Bolton et al. (2006) introduce a model examining a speculative market (as observed in the US in the late 90 s) in which stock prices have two components: a long-term fundamental component and a short-term speculative component.Footnote 2 Shareholders in a speculative market are willing to pay more than the stock’s long-term fundamental component because they expect to sell the shares in the short term to other investors with more optimistic beliefs. The model shows that optimal CEO compensation contracts will give more weight to short-term performance as shareholders encourage CEOs to boost the short-term speculative price component. The model suggests that even long-term oriented shareholders may want managers to take actions that maximize short-term earnings performance as a way of reducing the firm’s cost of capital.

In summary, the literature provides both theory and evidence suggesting that compensation plans reward managers for meeting short-term performance targets when the market is dominated by short-term investors. As such, boards’ compensation committees would yield to the capital market pressure and provide CEOs with incentives to boost short-term earnings. Therefore, we expect that compensation committees reward (penalize) CEOs with higher (lower) option compensation for reducing (failing to reduce) R&D spending to avoid reporting earnings decreases. We state the formal hypothesis in an alternative form as follows:

H1

Ceteris paribus, incremental R&D spending has an adverse effect on a CEO option grant when a firm faces a small earnings decline.

Prior research shows that the market particularly penalizes firms for missing quarterly earnings benchmarks and the magnitude of the price response to negative surprises significantly exceeds the price response to positive surprises (e.g., Brown 2001; Skinner and Sloan 2002; Brown and Caylor 2005).Footnote 3 Matsunaga and Park (2001) find that firms with earnings lower than quarterly earnings thresholds for at least two quarters during the year punish their CEOs with lower annual cash bonuses. This finding suggests that the compensation system encourages managers to avoid downward stock price adjustments for missing quarterly earnings benchmarks. Consistent with the studies on the capital market pressure by short-term institutions, Shin (2006) finds that the penalty on CEO annual bonuses for missing quarterly earnings thresholds increases with the percentage of ownership by short-term institutional investors. These investors are more concerned about negative surprises in quarterly earnings.

Overall, prior studies suggest that the pressure for meeting last year’s earnings level by reducing R&D is more pronounced for firms facing a myopia problem which have frequently missed thresholds earlier in the year. When the compensation system rewards managers for meeting short-term earnings targets, CEOs will feel greater pressure to take actions, such as cutting R&D, to avoid reporting a decline in earnings because the failure to hit quarterly benchmarks earlier in the year decreases the likelihood that the firm will be able to achieve its annual earnings target. Therefore, we expect that CEOs will receive an additional penalty when firms miss quarterly earnings benchmarks and the CEOs are unable or unwilling to respond to the increasing pressure by rejecting or postponing positive NPV projects. The formal hypothesis stated in the alternative form is as follows:

H2

Ceteris paribus, incremental R&D spending has an adverse effect on a CEO option grant when a firm facing a small earnings decline misses quarterly earnings benchmarks.

For both hypotheses, the ceteris paribus condition means that the hypotheses predict negative incremental effects of failing to cut R&D to increase earnings after controlling for the “normal” effect of firm performance and R&D on CEO option pay.

3 Research design

We focus our analysis on a sample of “Small Decrease” (SD) firms whose decisions to maintain or cut R&D affect the growth in reported earnings. Prior research suggests a high likelihood that such firms forsake R&D investments to boost current earnings (Baber et al. 1991; Bushee 1998). For comparison purposes, we also examine “increase” (IN) and “large decrease” (LD) firms that do not have the same incentives to reduce R&D to reverse earnings declines. Following Baber et al. (1991) and Bushee (1998), we use prior year’s pretax earnings as an income target since managers consider avoiding earnings decreases an important threshold to meet (e.g., Burgstahler and Dichev 1997; Barth et al. 1999) and use prior year’s R&D expenditures as a proxy for the current year’s R&D investment opportunities. Table 1 shows our definitions for the SD sample and the other two groups (i.e., IN and LD).

Under scenario one (i.e., “increase” or IN), a difference between pre-tax, pre-R&D earnings and the income target is greater than the cost of acceptable R&D opportunities (i.e., EBTRD t − EBT t − 1 > R&D t − 1). The IN firms could accept all existing R&D projects and still report an increase in pre-tax earnings. Under scenario three (i.e., “large decrease” or LD), pre-tax, pre-R&D earnings is lower than the income target (i.e., EBTRD t − EBT t − 1 ≤ 0). The LD firms could reject all acceptable R&D opportunities and still report a decrease in pre-tax earnings. For managers of IN and LD firms, maintaining last year’s R&D spending does not affect the trend in reported income in the current period. Scenario two (i.e., “small decrease” or SD) is the tipping point event in which the difference between earnings before R&D and taxes and the income target is positive but less than prior level of R&D (i.e., 0 < EBTRD t − EBT t − 1 < R&D t − 1). In this case, managers face the trade-off between the short-term pressure to “deliver earnings” by reducing R&D spending and the long-term objective of making value-maximizing investment decisions.

To test whether CEO option compensation provides incentives for managers to reduce R&D spending to avoid earnings decreases (H1), we estimate the following regression:

where for each firm i and year t:

- ∆OPTION it :

-

change in CEO annual stock option grants (in thousands of dollars) from year t − 1 to year t, computed as ln(OPTION) it − ln(OPTION)it − 1. OPTION t (OPTION t − 1) is the CEO stock option grants as reported in the proxy statement following the end of year t (t − 1), valued using the Black and Scholes (1973) methodology;

- ∆RD it :

-

change in R&D expense (in millions of dollars) from year t − 1 to year t, computed as RD it − RD it − 1, where RD is R&D expense scaled by average book value of common equity (in millions of dollars);

- SD it :

-

1 if firm i faces a small earnings decrease in year t, and 0 otherwise;

- LD it :

-

1 if firm i faces a large earnings decrease in year t, and 0 otherwise;

- Incentive residual it − 1 :

-

residual from a regression of the incentives from stock options on their determinants as estimated in Core and Guay (1999). This residual is estimated at the end of the fiscal year prior to the fiscal year in which the new option grant is awarded (i.e., year t − 1);

- Log(Sales) it − 1 :

-

the logarithm of sales in year t − 1;

- Book-to-market it − 1 :

-

(book value of assets)/(book value of liabilities + market value of equity), estimated for year t − 1;

- Net operating loss it − 1 :

-

1 if firm i has net operating loss carry-forwards in any of the 3 years prior to year t, and 0 otherwise;

- Cash flow shortfall it − 1 :

-

the 3-years average of [(common and preferred dividends + cash flow from investing − cash flow from operations)/total assets], estimated for the 3 years prior to year t;

- Dividend constraint it − 1 :

-

1 if firm i is dividend constrained in any of the 3 years prior to year t, and 0 otherwise. A firm is dividend constrained if [(retained earnings at year-end + cash dividends and stock repurchases during the year)/the prior year’s cash dividends and stock repurchases] is <2 or if the denominator is zero for all 3 years;

- RET it, t − 1 :

-

annual stock return in year t and year t − 1;

- ∆ROE it :

-

change in accounting return on equity from prior to current fiscal year, computed as ROE it − ROEi t − 1, where ROE is earnings before R&D expenses and taxes divided by average book value of common equity (both in millions of dollars)

We use the natural logarithm of the change in CEO option compensation as the dependent variable.Footnote 4 Because boards are more likely to punish their CEOs for incremental R&D spending when they face an income reporting concern than when they do not, we include two interaction terms that allow the slope coefficients of the change in R&D to differ across subgroups of firms with different earnings scenarios, i.e., IN, SD, and LD. H1 predicts that even after controlling for the general relationships between option compensation and both performance and R&D spending, there is an incremental penalty for failing to reduce R&D to meet the prior year’s earnings level. Hence, we expect the coefficient of SD it * ∆RD it to be negative. H1 also implies that CEOs are unlikely to be punished for maintaining R&D spending if their investment decisions do not affect the trend in reported earnings. Therefore, we expect the coefficient of ∆RD it to be insignificant when it interacts with the group dummy LD.Footnote 5

We control for the change in R&D (∆RD) and predict a positive relation between ∆RD and the change in CEO stock options as documented in prior studies (Bryan et al. 2000; Ryan and Wiggins 2001). Prior research shows that the market reacts positively to increases in R&D investment of high technology firms (e.g., Chan et al. 1990), implying that additional R&D investment is desirable and tends to increase CEOs’ annual option compensation. Firms with small or large earnings decreases (SD and LD) are more likely to be poor performers compared to firms with earnings increases. However, prior research suggests that CEOs are more likely to reap rewards for good performance than to be penalized for poor performance (Gaver and Gaver 1998).Footnote 6 Thus, we provide no signed predictions for the coefficients of SD and LD.

Further, we control for other determinants of CEO option grants as suggested by Core and Guay (1999). These control variables include deviation from CEOs’ optimal level of equity incentives (Incentive residual it − 1), firm size (Log(Sales) it − 1), growth opportunity (Book-to-market it − 1), net operating loss (Net operating loss it − 1), cash flow shortfall (Cash flow shortfall it − 1), and dividend constraints (Dividend constraint it − 1).

Core and Guay (1999) find that firms use option grants to manage the optimal level of equity incentives. More specifically, they show that new option grants are increased (decreased) when the CEO’s equity portfolio is below (above) an optimal equity incentive level. We estimate the deviation of the CEO’s equity incentive level from its optimal level (Incentive residual) following the procedure in Core and Guay (1999). The actual incentive level is measured as the sensitivity of the option value to a 1% change in stock price (i.e., the sum of the deltas of each option held by the CEO multiplied by 1% of price). The optimal incentive level is determined by regressing the actual incentive levels on measures of firm size, firm risk, growth opportunities, CEO tenure, free cash flow, and year dummies.Footnote 7 The optimal incentive level is the predicted value of the equity incentive level computed using the estimated coefficients of this regression. Incentive residual is defined as the difference between the actual incentive level and the estimated, optimal incentive level. A negative (positive) residual suggests that CEOs’ incentive level is below (above) the optimal level. We expect a negative relationship between Incentive residual and the change in CEO stock options as option grants are expected to increase (decrease) when the actual incentive level is below (above) the optimal level.

Prior studies suggest that larger firms and growth firms have greater demand for a quality CEO, and therefore, are willing to pay higher compensation (e.g., Smith and Watts 1992). We use the logarithm of sales dollars as a proxy for firm size and the book-to-market ratio as a proxy for growth opportunities. We expect Log(Sales) it − 1 and Book-to-market it − 1 to be positively and negatively related to the change in CEO stock options, respectively.

Firms may also use stock options as a substitute for cash compensation. Prior studies (e.g., Yermack 1995; Matsunaga 1995; Dechow et al. 1996; Core and Guay 1999) show that the use of stock options is greater when firms have lower free cash flow, expect higher future corporate tax rates, and want to avoid expensing compensation. Since options do not require immediate cash payout, they provide a substitute for cash compensation when firms have cash constraints. Options also provide more favorable future tax deductions than immediate tax deductions from cash compensation when firms anticipate higher marginal tax rates. Finally, for the time periods that we examine (i.e., 1994–2002), firms are not required to expense the option value, but are required to provide a disclosure about the value in the footnotes to the financial statements. We use three variables (i.e., Cash flow shortfall, Net operating loss, and Dividend constraint) to measure the degree of cash shortfall and expect them to be positively related to the change in CEO stock options.

Finally, following prior research on performance-based compensation contracts (e.g., Lambert and Larcker 1987; Baber et al. 1996), our regression analysis also includes control variables for both market and accounting performance (RET it , RET it − 1, and ∆ROE it ). These variables are critical to separating the incremental effect of income disappointments due to R&D spending from the general effect of poor performance on compensation. We predict the coefficients of the current year and prior year stock returns and the change in accounting return on equity to be positive since CEO compensation is expected to increase when market- and accounting-based performance measures increase.

Hypothesis 2 tests whether the penalty for failing to reduce R&D to meet the earnings target in SD firms is conditional on meeting quarterly earnings benchmarks. For this purpose, we classify SD firms based on the incidence and frequency of missing a quarterly earnings benchmark. Following prior studies (e.g., Degeorge et al. 1999; Matsunaga and Park 2001; Brown and Caylor 2005; Graham et al. 2005), we use four quarterly earnings benchmarks that executives view as important thresholds to meet: same quarter last year EPS (DECY), analyst consensus forecast (NEGFE), previous quarter EPS (DECQ), and zero profit (LOSS). We use the dummy variables, PRESSURE0 and PRESSURE1–4, to capture the subgroup of firms meeting a benchmark for all four quarters, and those missing a benchmark for at least one quarter during the year, respectively. We specify the following regression:

where for each firm i and year t,

- PRESSURE0 it :

-

1 if firm i meets a benchmark for all four quarters during the year and 0 otherwise. PRESSURE refers to four earnings benchmarks: same quarter last year EPS (DECY), analyst consensus forecast (NEGFE), previous quarter EPS (DECQ), and zero profit (LOSS);

- PRESSURE1–4 it :

-

1 if firm i misses a benchmark for at least one quarter during the year and 0 otherwise. PRESSURE refers to four earnings benchmarks: same quarter last year EPS (DECY), analyst consensus forecast (NEGFE), previous quarter EPS (DECQ), and zero profit (LOSS)

The rest of the variables are defined earlier.

Prior research provides mixed evidence on the relationship between missing quarterly earnings benchmarks and CEO option compensation. Matsunaga and Park (2001) show that missing quarterly earnings benchmarks has a negative, but somewhat weaker, effect on CEO stock-based compensation than the effect on cash compensation. Carter et al. (2007) and Shin (2006), on the other hand, suggest that firms with more capital market pressure due to missing quarterly earning benchmarks prefer to use stock options to avoid compensation expenses, facilitating the achievement of a string of earnings increases. Given these mixed findings, we provide no signed predictions for the relationship between SD it *PRESSURE(J) it and ∆OPTION it .

H2 predicts that boards punish their CEOs more severely if the CEOs are unable or unwilling to cut R&D when firms miss earnings thresholds earlier in the year. Therefore, we expect the coefficient of (SD*PRESSURE1–4)*∆RD to be significantly negative. To support H2, the coefficient of (SD*PRESSURE0)*∆RD can carry either an insignificant or a smaller negative coefficient (relative to that of (SD*PRESSURE1–4)*∆RD). SD firms that meet an earnings benchmark in all four quarters are less likely to be punished for R&D increases than those frequently missing quarterly earnings benchmarks.

Assuming the level of market pressure for myopic investment increases with the frequency of missing earnings benchmarks, we further examine whether the stock-option penalty in SD firms increases with the number of quarters of missing an earnings threshold. We introduce five dummy variables, PRESSURE(J) (J = 0–4), to represent the number of quarters in which the firm misses an earnings benchmark. We estimate the following regressionFootnote 8:

where for each firm i and year t:

- PRESSURE(J) it :

-

1 if firm i meets a benchmark for J (J = 0–4) quarters during the year and 0 otherwise. PRESSURE refers to four earnings benchmarks: same quarter last year EPS (DECY(J)), analyst consensus forecast (NEGFE(J)), previous quarter EPS (DECQ(J)), and zero profit (LOSS(J));

- DECY(J) it :

-

1 if firm i misses prior year same quarter EPS for J (J = 0–4) quarters in year t and 0 otherwise;

- NEGFE(J) it :

-

1 if firm i misses analyst consensus forecast for J (J = 0–4) quarters in year t and 0 otherwise;

- DECQ(J) it :

-

1 if firm i misses prior quarter EPS for J (J = 0–4) quarters in year t and 0 otherwise;

- LOSS(J) it :

-

1 if firm i reports a loss for J (J = 0–4) quarters in year t and 0 otherwise

The rest of the variables are defined earlier. Similarly, H2 predicts negative signs for the interaction terms (SD it *PRESSURE(J) it )*∆RD it (J = 1–4).

4 Empirical results

4.1 Sample and descriptive statistics

The initial sample includes all firms in R&D-intensive industries with firm-years between 1994 and 2002 and data available on the ExecuComp, I/B/E/S, Compustat, and CRSP databases. We obtain CEO compensation data from ExecuComp and quarterly earnings forecasts from I/B/E/S. We obtain accounting and market performance data from Compustat and CRSP. We define an industry as R&D-intensive if it is identified as R&D-intensive, intangible-intensive, or high-tech by Collins et al. (1997), Dechow and Sloan (1991), Francis and Schipper (1999), and Lev and Sougiannis (1996). This process yields 2,141 CEO-year observations from 543 companies in 39 three-digit and 80 two-digit SIC industries. Only 135 executives (16.6%) have the maximum number of nine observations in the sample.

Panel A of Table 2 presents the distribution of the sample based on two-digit SIC codes and three earnings scenarios (i.e., IN, SD, and LD). Three industries, communications (SIC 481), business service (SIC 737), and engineering, accounting, and related service (SIC 873) are grouped as “other” because they have relatively fewer observations. Panel B shows that SD firms report, on average, smaller increases in R&D spending than IN or LD firms (t = −3.88 and −2.48, respectively).Footnote 9 This finding is consistent with Baber et al. (1991) and Bushee (1998), who suggest that firms facing small earnings declines tend to cut R&D to report income above prior year’s earnings.Footnote 10

We summarize the frequency distributions for the four earnings benchmarks in Table 2, Panel C. With the exception of the previous quarter EPS benchmark (DECQ), firms are most likely to meet a benchmark in all four quarters, or to miss the benchmark in just one quarter. Nonetheless, a nontrivial proportion of firms miss their quarterly benchmarks more than once during a year, especially LD firms with poorer performance.

Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics of our sample. To reduce the effects of extreme observations, we winsorize the top and bottom 0.5% of each variable’s distribution. Columns 3 through 7 of Table 3 present means, standard deviations, quartile one (Q1) values, medians, and quartile three (Q3) values of our variables. The last three columns show the mean differences and p values for the variables for the following sub-sample comparisons: SD vs. others, SD vs. IN, and SD vs. LD.

The mean ratio of R&D spending to average book value of common equity (i.e., RD) for the sample firms is 16.2%. The mean (median) change in R&D (i.e., ∆RD) is 0.8 (−0.1) percent of average book value of common equity, indicating that the change in R&D spending is relatively small from year to year. Consistent with the frequency distributions of missing earnings benchmarks in Panel C of Table 2, the mean (median) frequencies for missing the four benchmarks are ≤2.

The last three columns of Table 3 compare the means for each variable between sub-samples. On average, the changes in CEO option compensation are not significantly different between SD firms and the rest of the sample. The level of R&D spending (RD) in SD firms is greater than those in IN and LD sub-samples (t-statistics = 3.96 and 5.01, respectively). We do not find a significant difference in the average change in R&D spending (i.e., ∆RD) across the groups; but the means of relative R&D spending, as reported in Table 2, Panel B, are significantly different between SD and the other two groups.Footnote 11

For all earnings benchmarks, SD firms report, on average, higher frequencies of earnings misses than do IN firms, but lower frequency of earnings misses than do LD firms (all significant at the 0.01 level, two-tailed). Our results also indicate that SD firms are smaller (measured by sales revenue) than IN firms (significant at the 0.01 level, two-tailed), but are not significantly different in size from LD firms. We find that SD firms report higher book-to-market ratios (a proxy for growth opportunities) than IN firms, but show lower book-to market ratios than LD firms (all significant at the 0.01 level). Compared to both IN and LD firms, SD firms have lower free cash flow (t-statistics = 3.16 and 3.57, respectively). Finally, the accounting (∆ROE) and stock performance (RET) of SD firms are generally lower than that of IN firms, but higher than that of LD firms.

4.2 Test of hypothesis 1

Table 4 reports the OLS results of Eq. 1. We present two models. In Model 1, the coefficient of ∆RD represents the association between the change in R&D spending and the change in CEO option grants for the combined IN and LD sample, while the coefficient of the interaction of SD and ∆RD represents the penalty on CEO compensation when SD firms maintain R&D spending and fail to report earnings increases. In Model 2, the coefficient of ∆RD represents the association between the change in R&D and the change in CEO option grants for IN firms, and the coefficients of SD*∆RD and LD*∆RD provide the incremental effect of maintaining R&D on CEO option compensation for SD and LD firms, respectively.

For both models, the coefficients of ∆RD is positive and significant (at the 0.05 level or better, one-tailed), suggesting that CEOs are rewarded with greater option grants for rising R&D spending. The interaction of SD*∆RD is negatively associated with the change in the value of CEO annual option compensation (significant at the 0.01 level or better, one-tailed, for both models), indicating that managers in SD firms face a penalty for failing to cut R&D to reverse an earnings decline. In Model 2, the coefficient of LD*∆RD is insignificant, suggesting that the CEOs of LD firms do not receive a penalty for increasing R&D spending. Unlike SD firms which depend on reducing R&D for reporting earnings increases, LD firms could increase or decrease their R&D spending without affecting the trend in their reported earnings.

Three other determinants of new option grants are significantly associated with the dependent variable (significant at the 0.05 level or better, one-tailed, for both models). A negative coefficient of Incentive residual suggests that CEOs whose equity incentive is above (below) the optimal incentive level receive smaller (larger) option grants. Log(Sales), a proxy for firm size, is positively associated with the change in option grants while Book-to-market, a proxy for growth opportunities, are negatively associated with the change in option grants (i.e., smaller book-to-market ratio is associated with greater growth opportunities). Finally, while market performance (RET) in both the current and the prior fiscal year is positively associated with the change in grants, the change in accounting return (∆ROE) unexpectedly has a negative association with the change in option grants.

Overall, consistent with our first hypothesis, the findings suggest that firms with concerns about reported income (i.e., SD firms) provide their CEOs with lower option grants when the CEOs maintain R&D spending and fail to report an earnings increase. We do not observe this phenomenon for firms without concerns about reported income (i.e., IN and LD firms). The observed negative association between changes in R&D spending and changes in CEO option compensation for SD firms are consistent with the view that compensation committees consider meeting short-term earnings thresholds an important aspect of executive pay packages, and accordingly, reward CEOs for giving up positive NPV projects to meet short-term earnings benchmarks. Our findings are contradictory to Cheng (2004), who documents a positive association between changes in R&D spending and changes in CEO option compensation for firms facing a myopia problem and attributes the result to the role of boards’ compensation committees in preventing potential opportunistic reduction in R&D spending.

Our analysis differs from Cheng (2004) in two major aspects. First, our sample is larger and more recent than that of Cheng (2004). We use 543 firms and 2,141 firm-year observations in the ExecuComp database over the period 1994–2002, while Cheng uses a sample of 160 Forbes 500 firms that have compensation data in firm proxy statements, 10 Ks, and Forbes annual surveys of CEO compensation between 1984 and 1997. We are unable to perform an analysis of the periods prior to 1994 because the compensation data is only available in the ExecuComp database starting in 1992 and we need the data in year t − 1 to perform the change analysis and the CEO tenure data in year t − 2 to compute Incentive residual in year t − 1.Footnote 12 Second, unlike Cheng (2004), we control for other determinants of new option grants (e.g., deviation from CEOs’ optimal level of equity incentives, cash flow shortfall, dividend constraints, firm size, and growth opportunity). We find significant and consistent results after controlling for these factors.

Our results are consistent with the archival evidence that the stock market focused much more closely on firms’ proclivity to achieve earnings benchmarks (e.g., Brown 2001) and that firms missing earnings benchmarks received increasingly more negative valuation consequence in the more recent periods (e.g., Brown 2003; Brown and Caylor 2005). Our results are also consistent with both recent theoretical predictions (e.g., Stein 1989; Bar-Gill and Bebchuk 2003; Bolton et al. 2006) and US survey findings (Graham et al. 2005), suggesting that boards and compensation committees promote myopia through option compensation. Our results, therefore, tend to suggest that compensation committees altered their strategy from rewarding managers for undertaking R&D projects toward forgoing the rewards when the firms otherwise would not meet the earnings hurdles.

4.3 Test of hypothesis 2

In this section, we test whether the penalty for maintaining R&D primarily exists for firms facing small earnings decrease (i.e., SD firms) that have missed quarterly earnings benchmarks earlier in the year. We expect that firms missing quarterly earnings thresholds earlier in the year are subject to greater market pressure. As discussed in Sect. 3, we partition the SD sample into several subgroups based on the incidence or frequency of missing a quarterly earnings benchmark. Table 5 presents the OLS estimations of Eqs. 2 and 3 for each quarterly earnings threshold, i.e., DECY, NEGFE, DECQ, and LOSS.

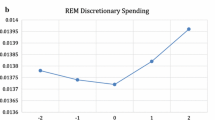

The insignificant coefficients of (SD*PRESSURE0)*∆RD may imply that these SD firms are unlikely to be punished for R&D increases because they are exposed to less market pressure for myopic investment behavior, and thus, bear lower perceived costs for reporting an unfavorable trend in earnings. The interaction term (SD*PRESSURE1–4)*∆RD, in Eq. 2 is significant and negative for each earnings benchmark (one-tailed p < 0.01). The results show that, for SD firms, the penalty for increasing R&D is related to the incidence of missing a quarterly earnings threshold. The CEO option compensation decreases when SD firms miss quarterly earnings benchmarks at least once and fail to take real actions to cut R&D to report an earnings increase. Thus, H2 is supported.

As for the regression results of Eq. 3, we find that the coefficients of (SD*PRESSURE0)*∆RD and (SD*PRESSURE1)*∆RD are insignificant for each earnings benchmark, with the exception of DECY for which the coefficient of (SD*PRESSURE1)*∆RD is significantly negative (t-statistic = −3.25, one-tailed p < 0.01). Consistent with our predictions, the other three interaction terms (i.e., for missing the quarterly benchmarks twice, three times, and four times during the year) are significantly negative for DECY and NEGFE (at the 0.10 level or better, one-tailed). These results suggest that CEOs receive a penalty for choosing R&D over reporting increased income when the firm’s quarterly earnings fall short of the earnings for the same quarter last year or the consensus analyst forecast for at least two quarters during the year. They provide further support for H2. The results for DECQ and LOSS are weaker than those of the first two benchmarks.Footnote 13 For each benchmark, the estimated coefficients do not seem to decline gradually as firms record earnings misses in more quarters.

Overall, our findings do not suggest that managers necessarily set out to cut R&D to achieve favorable trends in reported earnings. Instead, the need to reduce R&D spending seems more pronounced for firms missing quarterly benchmarks earlier in the year. The results show that CEO option grants provide managers with incentives to respond to the market pressure by eliminating or postponing positive NPV investments. This finding validates the widely held claim that managers sometimes manage earnings through ‘‘real’’ decisions like reducing R&D expenditures (Dechow and Sloan 1991; Bushee 1998; Graham et al. 2005; Roychowdhury 2006).

5 Additional analyses

5.1 The penalty for increasing R&D for firms without an income reporting concern

The previous section suggests that boards punish their CEOs when they are unable or unwilling to respond to increasing market pressure by eliminating or postponing positive NPV projects. A potential explanation for our results is that CEOs are punished for their failure to hit quarterly earnings thresholds, even if they do not face a trade-off between delivering current year earnings and making long-run optimal investment decisions. For example, Matsunaga and Park (2001) document a significant incremental adverse effect on CEO annual cash bonuses when the firm’s quarterly earnings fall short of the consensus analyst forecast or the earnings for the same quarter of the prior year.

As a robustness check, we examine whether a similar penalty exists in LD firms that more frequently miss earnings thresholds. Specifically, we group LD firms by the incidence and frequency of missing quarterly earnings thresholds and rerun Eqs. 2 and 3 with an indicator variable for each of the corresponding LD subgroups.

For LD firms, maintaining last year’s R&D spending should have no direct compensation consequence because such decision does not affect the trend in reported income in the current period. Consistent with our prediction, the results (untabulated) show that all, except one coefficient of LD*PRESSURE(J)*∆RD, are insignificant, suggesting that the adverse effects of market pressure on the relationship between R&D expenditures and CEO options are not present in LD firms. Therefore, we conclude that firms missing quarterly earnings benchmarks are under pressure to reject or postpone positive NPV investments only when they have a pronounced concern about reporting favorable trends in earnings.

5.2 Alternative model specifications

We conduct several tests to assess the robustness of our results to alternative specifications. First, we estimate Eqs. 1–3 with each control variable measured as the change from year t − 1 to year t. Our results using the change specification (untabulated) are similar to those reported in Tables 4 and 5. Therefore, our conclusion that CEOs of SD firms face a penalty for failing to cut R&D to reverse an earnings decline remains unchanged.

Second, we perform a two-stage least squares analysis to address the potential simultaneity between changes in R&D spending and changes in CEO option compensation, following the procedure in Cheng (2004). In the first stage, we estimate the following regression for every year and two-digit SIC industry: ∆RD it = β 0 + β 1 IND_∆RD it + ε it , where IND_∆RD it is the average ∆RD of other firms in the same four-digit SIC industry as firm i in year t. In the second stage, we estimate Eqs. 1–3 using the fitted value of ∆RD from the first stage. The results (untabulated) are similar, albeit weaker, to those reported in Tables 4 and 5. The interactive variable SD*∆RD in Eq. 1 is negatively associated with the change in the CEO option compensation (significant at the 0.05 level or better, one-tailed). The coefficient of the interaction term (SD*PRESSURE1–4)*∆RD in Eq. 2 is also significant and negative for each earnings benchmark (at the 0.05 level or better, one-tailed). Overall, our findings are robust to the simultaneity of R&D expenditures and CEO option compensation.

5.3 Alternative proxies for capital market pressures

Our primary tests assume that the level of market pressures for myopic investment behavior increases with the frequency of missing quarterly earnings benchmarks. We also consider the stock market reaction to negative earnings surprises as an alternative proxy for capital market pressures. We examine whether firms operating in industries with more adverse valuation consequences for negative surprises are more likely to evidence the compensation penalty for failing to reverse earnings declines with reductions in R&D spending. Following Brown (2003), we define negative earnings surprise as the reported quarterly earnings falling short of analyst expectations and measure analyst expectations using the last analyst forecast of the quarterly earnings issued prior to the earnings announcement. We measure the market reaction to negative earnings surprises as the 3-days market-adjusted cumulative abnormal returns around earnings announcement dates. We compute the average stock market returns to negative earnings surprises for every four-digit SIC industry and year. Then, we assign the sample firms into the high (low) market pressure subsample when the industry average stock returns are below (above) the median.Footnote 14

We find that the coefficient of the interactive variable SD*∆RD in Eq. 1 is significantly negative only for the high market pressure subsample (at the 0.01 level, one-tailed), while the coefficient of the interactive variable SD*∆RD for the low market pressure subsample is not significant (untabulated). Consistent with our expectation, the penalty on CEO option compensation for failing to cut R&D to reverse earnings declines is more severe for firms operating in the industries that suffer more adverse valuation consequences for missing earnings benchmarks.Footnote 15

Prior studies show that firms planning to raise capital in the near future also face increased pressures to maintain high level of earnings (Teoh and Wong 1998; Teoh et al. 1998; Anthony et al. 2004; Richardson et al. 2004). Furthermore, Carter et al. (2007) find that capital-raising activities affect the level of CEOs’ option compensation. Therefore, we control for the need to access capital markets as an alternative proxy for capital market pressures. We include two variables measuring the extent to which a firm accesses the equity and debt markets in the upcoming year, as well as their interactions with ∆RD, in Eqs. 2 and 3.Footnote 16 Untabulated results are similar to those in Table 5.

5.4 The effect on CEO cash compensation

We focus on the effect of income reporting concern on the association between R&D spending and CEO option compensation. As discussed by Duru et al. (2002), CEO cash compensation is generally shielded from the income-decreasing effects of R&D spending. Therefore, corporate boards are unlikely to punish their CEOs for maintaining last year’s R&D spending in determining cash compensation. As a robustness check, we rerun Eqs. 2 and 3 using changes in CEO cash compensation as the dependent variable.Footnote 17 Consistent with Matsunaga and Park (2001), we find significant incremental adverse effects on CEO annual cash compensation when the group of firms missed earnings thresholds for at least two quarters during the year. However, the coefficients of SD*PRESSURE(J)*∆RD are either significantly positive or insignificant, indicating that CEO cash compensation is at least partially shielded from the adverse effect of increasing R&D.

5.5 Other analyses

Prior research suggests that CEOs become more short-term oriented as they approach retirement and compensation committees may adjust CEO compensation arrangements to induce retiring CEOs to accept risky, value-increasing investment projects (Dechow and Sloan 1991; Dikolli 2001; Cheng 2004; Dikolli et al. 2004). We, therefore, control for the effect of the CEOs’ decision horizon on the association between changes in R&D and changes in CEO option in our primary tests. We set HORIZON to one if the CEO is at least 63 years old, and zero otherwise (Cheng 2004). Our inferences remain unchanged after controlling for the effect of CEO decision horizon.

Following Shin (2006), we also estimate an industry fixed effects model to control for the effect of heterogeneity on CEO option pay. We include seven industry dummies since our sample is distributed across 80 two-digit SIC codes. The results (untabulated) are very similar to those reported in Tables 4 and 5.

6 Conclusion

We examine the effect of capital market pressure for meeting earnings benchmarks on the association between R&D spending and CEO option compensation. We consider a particular scenario in which the difference between earnings before R&D (and taxes) and the income target is positive but less than prior year’s R&D spending (i.e., a myopia problem). In this case, firms could opportunistically reduce R&D spending to increase reported earnings. Given the concern about meeting the annual earnings target, we hypothesize and find that CEOs are punished with lower annual option grants in the situation where R&D increases but earnings decreases. We further hypothesize and find that, for firms with the concern about reported income, the penalty on CEO option grants for increasing R&D spending is greater when they miss quarterly earnings benchmarks earlier in the year.

Our findings are generally consistent with the claim that managers sometimes manage earnings through real economic actions rather than accounting manipulations (Dechow and Sloan 1991; Bushee 1998; Graham et al. 2005; Roychowdhury 2006). Our evidence shows that CEO option grants focus on meeting short-term earnings targets and encourage short-run actions to eliminate or postpone positive NPV R&D projects. Since managers do not hesitate to sacrifice discretionary spending with nontrivial future economic consequences to meet short-term performance targets, the current compensation practice may have put firms’ long term future at risk. Therefore, our results suggest that boards of directors should reexamine the practice of rewarding (penalizing) CEOs with higher (lower) option compensation for meeting (missing) short-term earnings thresholds.

Furthermore, our results suggest that income reporting concerns, and thus the need for R&D cuts, are more pronounced in firms that have missed quarterly benchmarks earlier in the year. While past research has established a link between meeting or beating (missing) earnings benchmarks and CEO cash bonuses (Matsunaga and Park 2001; Shin 2006), we add to this line of research by empirically linking missing quarterly earnings thresholds to the pressure on managers to avoid reduction in option grants via myopic investment decisions. Thus, we show that the potential penalty for missing earnings benchmarks extends beyond CEOs’ cash bonuses.

This study is subject to several limitations. The principal caveat is that although our findings suggest that boards of directors, on average, reward (punish) CEOs for meeting (missing) earnings benchmarks, we do not examine the precise corporate governance mechanisms leading to this practice. Future research could examine, for example, whether corporate board structures and director characteristics influence the association between R&D spending and CEO option grants.

Notes

The SEC sent letters to nearly 300 companies critiquing executive compensation disclosures in their 2007 proxy statements and demanding more information about the targets and benchmarks that corporate boards use to tie executive pay to performance (Scannell and Lublin 2007).

Brown (2001) shows that loss surprises tend to be negative and extreme, whereas profit surprises tend to be positive and small. Brown and Caylor (2005) find that negative earnings surprises have become scarcer and that short-term market reactions to missing analyst consensus forecasts are larger than those to missing earnings for the same quarter prior year. Skinner and Sloan (2002) demonstrate that growth stocks are more likely to exhibit an asymmetric response to earnings surprises.

We use the natural logarithmic transformation to control for skewness in CEO compensation (Cheng 2004). For robustness, we use the change in option grants (untransformed) as an alternative dependent variable. The results are qualitatively similar to those with the transformation.

We replace LD with a dummy variable for the “increase” firms (IN) and find that the coefficient of ∆RD is insignificant when interacting with IN.

It is consistent with the perception of regulators and media that top executives have not shared in the losses of their companies (e.g., Donaldson 2003).

We make several modifications to the procedures adopted by Core and Guay (1999). First, we use the risk-free rate in ExecuComp, rather than the risk-free interest rate (treasury yield) corresponding to time-to-maturity of the options. Second, we include only year indicator variables. Despite these simplifying modifications, we are able to replicate the results in Core and Guay (1999) and obtain similar distribution of portfolio equity incentives, regression adjusted R 2 (42.7% compared to 47.8% in Core and Guay), and distribution of Incentive residual.

Following Baber et al. (1991), we compare the group difference in relative R&D (defined as the ratio of current to prior period R&D spending).

The proxies for the change in R&D are slightly different between these two studies. Baber et al. (1991) use relative R&D, i.e., the ratio of current to prior year R&D spending; and Bushee (1998) uses the frequency of R&D cuts. For our sample, we find that SD firms have a lower relative R&D, and a higher frequency of R&D cuts than IN and LD firms.

In an untabulated analysis, we examine the association between changes in R&D spending and the myopia problem using the following regression: ∆RD it = β 0 + β 1 SD it + β 2 IND_∆RD it + ε it , where IND_∆RD it is the average ∆RD of other Compustat firms in the same four-digit industry as firm i in year t. In addition, we estimate the above regression using Relative R&D as an alternative proxy for R&D change, and the average Relative R&D of other Compustat firms in the same four-digit industry as firm i in year t as the control variable. Consistent with the univariate results, the coefficient of SD in the regression of ∆RD is not significant but the coefficient of SD in the regression of Relative R&D is negative and significant (at the 0.01 level, one-tailed).

Nevertheless, we partially replicate Cheng (2004) using ExecuComp data by identifying R&D-Intensive firms in the Forbes 500 rankings between 1994 and 1997 (114 observations) and extend the analysis to cover more recent periods from 1994 to 2002 (330 observations). We find significantly negative associations between changes in R&D spending and changes in CEO option compensation for firms facing a myopia problem for both periods. However, without fully replicating Cheng (2004), we may not attribute the differences in the results to variations in data sources or time periods.

The small percentage of firms missing the previous quarter EPS (DECQ) for four quarters during year t (1.7%—Panel C of Table 2) may be a reason for the insignificant coefficient of the interaction term SD*PRESSURE4*∆RD in Model 3 (DECQ). In addition, Graham et al. (2005) suggest that the previous quarter EPS may be a less important benchmark compared to the other earnings benchmarks, particularly the quarterly earnings for the same quarter last year (DECY) and the analyst consensus estimate (NEGFE). This provides an additional reason for the weak result for DECQ.

Brown (2003) finds that high-tech firms have more negative valuation consequence for missing earnings benchmarks than non-high tech firms. Since we do not have non-high tech firms in our samples, we use the average stock market returns to negative earnings surprise to partition firms into high market pressure and low market pressure industries.

As an additional test, we group firms into “pattern” or “non-pattern” categories based on whether they have at least three consecutive prior years of increasing earnings patterns. We find that the incentive penalty for increasing R&D spending while reporting earnings decreases pertains to only the non-pattern subsample. The results are consistent with Barth et al. (1999), who find that the stock market rewards firms exhibiting patterns of increasing earnings with incremental earnings multiples and just 1 year of decreased earnings is insufficient to eliminate the market reward associated with the previously increasing earnings pattern.

Following Carter et al. (2007), ISSUE_EQ is measured by the future increase in equity capital (i.e., the sum of common stock, paid in capital, preferred stock, and treasury stock) for firm i from year t to year t + 1, scaled by assets. ISSUE_DEBT is measured by the future increase in debt capital (i.e., current liability plus long-term debt) for firm i from year t to year t + 1, scaled by assets. Both variables are set to zero when the calculation yields a negative number.

Defined as change in CEO annual cash compensation from prior to current fiscal year, computed as ln(COMP) it − ln(COMP)it − 1. CEO cash compensation is the sum of CEO salary and annual bonus.

References

Anthony JH, Bettinghaus B, Farber DB (2004) Earnings management and the market response to convertible debt issuance. Working paper, Michigan State University

Baber W, Fairfield P, Haggard J (1991) The effect of concern about reported income on discretionary spending decisions: the case of research and development. Account Rev 66(4):818–829

Baber W, Janakiraman S, Kang S (1996) Investment opportunities and the structure of executive compensation. J Account Econ 21(3):297–318. doi:10.1016/0165-4101(96)00421-1

Bar-Gill O, Bebchuk LA (2003) Misreporting corporate performance. Harvard law and economics discussion paper. Available at SSRN. http://ssrn.com/abstract=354141 or doi:10.2139/ssrn.354141

Barth ME, Elliott JA, Finn MW (1999) Market rewards associated with patterns of increasing earnings. J Account Res 37(2):387–413. doi:10.2307/2491414

Bartov E (1993) The timing of asset sales and earnings manipulation. Account Rev 68(4):840–855

Bartov E, Givoly D, Hayn C (2002) The rewards to meeting or beating earnings expectations. J Account Econ 33(2):173–204. doi:10.1016/S0165-4101(02)00045-9

Black F, Scholes M (1973) The pricing of options and corporate liabilities. J Polit Econ 81(3):637–654

Bolton P, Scheinkman J, Xiong W (2006) Executive compensation and short-termist behaviour in speculative markets. Rev Econ Stud 73(3):577–610. doi:10.1111/j.1467-937X.2006.00388.x

Brown L (2001) A temporal analysis of earnings surprises: profits versus losses. J Account Res 39(2):221–241. doi:10.1111/1475-679X.00010

Brown L (2003) Small negative surprises: frequency and consequence. Int J Forecast 19(4):149–159. doi:10.1016/S0169-2070(02)00061-4

Brown L, Caylor M (2005) A temporal analysis of quarterly earnings thresholds: propensities and valuation consequences. Account Rev 80(2):423–440. doi:10.2308/accr.2005.80.2.423

Bryan S, Hwang L, Lilien S (2000) CEO stock-based compensation: an empirical analysis of incentive-intensity, relative mix, and economic determinants. J Bus 73(4):661–693. doi:10.1086/209658

Burgstahler D, Dichev I (1997) Earnings management to avoid earnings decreases and losses. J Account Econ 24(1):99–126. doi:10.1016/S0165-4101(97)00017-7

Burgstahler D, Eames M (2003) Earnings management to avoid losses and earnings decreases: are analysts fooled? Contemp Account Res 20(2):253–294. doi:10.1506/BXXP-RGTD-H0PM-9XAL

Bushee B (1998) The influence of institutional investors on myopic R&D investment behavior. Account Rev 73(3):305–333

Carter ME, Lynch LJ, Tuna I (2007) The role of accounting in the design of CEO equity compensation. Account Rev 82(2):327–357. doi:10.2308/accr.2007.82.2.327

Chan S, Martin J, Kensinger J (1990) Corporate research and development expenditures and share value. J Financ Econ 26(2):255–276. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(90)90005-K

Cheng S (2004) R&D expenditures and CEO compensation. Account Rev 79(2):305–328. doi:10.2308/accr.2004.79.2.305

Collins D, Maydew E, Weiss I (1997) Changes in the value-relevance of earnings and book values over the past forty years. J Account Econ 24(1):39–67. doi:10.1016/S0165-4101(97)00015-3

Core J, Guay W (1999) The use of equity grants to manage optimal equity incentive levels. J Account Econ 28(2):151–184. doi:10.1016/S0165-4101(99)00019-1

Dechow P, Sloan R (1991) Executive incentives and the horizon problem: an empirical investigation. J Account Econ 14(1):51–89. doi:10.1016/0167-7187(91)90058-S

Dechow P, Hutton A, Sloan R (1996) Economic consequences of accounting for stock-based compensation. J Account Res 34(3):1–20. doi:10.2307/2491422 Suppl

Dechow P, Richardson S, Tuna I (2003) Why are earnings kinky? An examination of the earnings management explanation. Rev Account Stud 8(2–3):355–384. doi:10.1023/A:1024481916719

DeFond ML, Park CW (1997) Smoothing income in anticipation of future earnings. J Account Econ 23(2):115–139. doi:10.1016/S0165-4101(97)00004-9

Degeorge F, Patel J, Zeckhauser R (1999) Earnings management to exceed thresholds. J Bus 72(1):1–33. doi:10.1086/209601

Dikolli S (2001) Agent employment horizon and contracting demand for forward-looking performance measures. J Account Res 39(3):481–494. doi:10.1111/1475-679X.00024

Dikolli S, Kulp S, Sedatole K (2004) Transient institutional investor concentration and pay-for-performance sensitivity in CEO incentive contracts. Working paper, University of Texas at Austin

Donaldson WH (2003) Speech by SEC chairman, remarks at the 2003 Washington economic policy conference. National Association for Business Economics. Available at http://ftp.sec.gov/news/speech/spch032403whd.htm

Duru A, Iyengar WJ, Thevaranjan A (2002) The shielding of CEO compensation from the effects of strategic expenditures. Contemp Account Res 19(2):175–193. doi:10.1506/UM8Q-NVJ6-JKGT-GH5W

Francis J, Schipper K (1999) Have financial statements lost their relevance? J Account Res 37(2):319–352. doi:10.2307/2491412

Gaver J, Gaver K (1998) The relation between nonrecurring accounting transaction and CEO cash compensation. Account Rev 73(2):235–253

Graham JR, Harvey CR, Rajgopal S (2005) The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. J Account Econ 40(1–3):3–73. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2005.01.002

Holmstrom B (1979) Moral hazard and observability. Bell J Econ 10(1):74–91. doi:10.2307/3003320

Holmstrom B, Tirole J (1993) Market liquidity and performance monitoring. J Polit Econ 101(4):678–709. doi:10.1086/261893

Kasznik R, McNichols M (2002) Does meeting earnings expectations matter? Evidence from analyst forecast revisions and share prices. J Account Res 40(3):727–759. doi:10.1111/1475-679X.00069

Lambert R, Larcker D (1987) An analysis of the use of accounting and market measures of performance on executive compensation contracts. J Account Res 25(3):85–125. doi:10.2307/2491081 Suppl

Lev B, Sougiannis T (1996) The capitalization, amortization, and value-relevance of R&D. J Account Econ 21(1):107–138. doi:10.1016/0165-4101(95)00410-6

Lipton M, Lorsch JW (1992) A modest proposal for improved corporate governance. Bus Lawyer 48(1):59–77

Mace LM (1986) Directors: myth and reality. Harvard Business School Classics, Boston

Matsumoto D (2002) Management’s incentives to avoid negative earnings surprises. Account Rev 77(3):483–514. doi:10.2308/accr.2002.77.3.483

Matsunaga S (1995) The effects of financial reporting costs on the use of employee stock options. Account Rev 70(1):1–26

Matsunaga S, Park C (2001) The effect of missing a quarterly earnings benchmark on the CEO’s annual bonus. Account Rev 76(3):313–332. doi:10.2308/accr.2001.76.3.313

Mirrlees J (1999) The theory of moral hazard and unobservable behaviour: part I. Rev Econ Stud 66(226):3–21 Note: the paper was completed in October 1975 but never previously published

Myers JN, Myers LA, Skinner DJ (2007) Earnings momentum and earnings management. J Account Audit Financ 22(2):249–284

Payne JL, Robb SG (2000) Earnings management: the effect of ex ante earnings expectations. J Account Audit Financ 15(4):371–392

Richardson S, Teoh SH, Wysocki P (2004) The walk-down to beatable analysts’ forecasts: the role of equity issuance and insider trading incentives. Contemp Account Res 21(4):885–924. doi:10.1506/KHNW-PJYL-ADUB-0RP6

Roychowdhury S (2006) Earnings management through real activities manipulation. J Account Econ 42(3):335–370. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2006.01.002

Ryan HE, Wiggins RA (2001) The influence of firm- and manager-specific characteristics on the structure of executive compensation. J Corp Finance 7:101–123. doi:10.1016/S0929-1199(00)00021-3

Scannell K, Lublin JS (2007) SEC asks firms to detail top executives’ pay. The Wall Street J 31:B1

Shin JY (2006) Institutional investment horizons and the structure of CEO compensation. Working paper, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Skinner D, Sloan R (2002) Earnings surprises, growth expectations and stock returns, or don’t let an earnings torpedo sink your portfolio. Rev Account Stud 7(2)/3:289–312

Smith C, Watts R (1992) The investment opportunity set and corporate financing, dividends, and compensation policies. J Financ Econ 32(3):263–292. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(92)90029-W

Stein J (1989) Efficient capital market, inefficient firms: a model of myopic corporate behavior. Q J Econ 104(4):655–669. doi:10.2307/2937861

Teoh SH, Wong TJ (1998) Earnings management and the long-run market performance of initial public offerings. J Finance 53(6):1935–1974. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00079

Teoh SH, Welch I, Wong TJ (1998) Earnings management and the underperformance of seasoned equity offerings. J Financ Econ 50(1):63–99. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(98)00032-4

Yermack D (1995) Do corporations award CEO stock options effectively? J Financ Econ 39(2)/3:237–269

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, J., Laksmana, I. The effect of capital market pressures on the association between R&D spending and CEO option compensation. Rev Quant Finan Acc 34, 273–300 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-009-0146-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-009-0146-7