Abstract

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms with worldwide increasing incidence, high prevalence and survival. Both the tumor itself and the systemic therapy may have an impact on patients’ nutrition. Malnutrition negatively impacts on outcome in NETs patients. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that body mass index was a risk factor for NET development and that metabolic syndrome was associated with worse prognosis in these patients. Of note, food could also interact with the metabolism of oral target therapy and antineoplastic agents used for the treatment of progressive NETs. Therefore, the nutritional assessment, based on body composition, and lifestyle modifications should be an integral component of management of the NET patients. The nutrition care plans are an integral part of the multidisciplinary management team for patients with NETs. Nutritionists with expertise in NETs can provide dietary approaches to improve the quality of life and nutritional status during various therapeutic modalities used in patients with NETs. The aim of this review is to critically discuss the importance of nutrition and body composition in patients with NETs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms, whose incidence has rapidly increased in the last decades to 7.4 cases/100,000 [1,2,3,4]. NETs arise in any tissue and organ, though they mainly affect the gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) and bronchopulmonary tract [5, 6], and show high survival rate and prevalence [1]. Age of onset is considerably variable, but NETs more frequently occur in the sixth decade, except when related to inherited syndromes, as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) or von Hippel Lindau disease [7,8,9,10]. Clinical manifestations include specific syndromes related to hormone secretion and local symptoms due to mass effect, but NETs may be diagnosed also as incidental findings. The GEP-NETs are commonly characterized by hormone hypersecretion that may induce different metabolic impairments. Nevertheless, screening for hormone secretion is routinely not recommended in absence of specific signs or symptoms related to a specific syndrome [11], but early diagnosis of NET is crucial, as they may negatively affect outcomes [12].

Although NETs have mainly an indolent course, they often present with metastases, mainly hepatic metastases, already at diagnosis [13]. In the long natural history, patients are often treated with more therapeutic lines. Besides surgery, first line therapy is usually represented by somatostatin analogs (SSA), since they have an antiproliferative effect and are capable to reduce hormone hypersecretion [14]. After progression with SSA, targeted therapies (everolimus and sunitinib), chemotherapy, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) are used in different sequences of treatment [15].

Both the tumor itself and the systemic therapy may have an impact on patients’ nutrition [16]. The role of nutrition is highly important in cancer patients, as malnutrition negatively impacts on rates of complications, hospitalization, hospital stay, costs and mortality [16, 17]. It has been demonstrated that a poor nutritional status could influence the outcome of patients with pancreatic NET [18] and predicts the tumor response in patients receiving the transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for liver metastases [19]. In order to prevent all these negative outcomes, the detection of malnutrition should be carried out with appropriate tools, early after diagnosis, particularly in NETs, whose natural history is usually longer than in several cancer types [20].

Beyond the nutrition, convincing evidence suggest that the excess of body fat represents a cause of several cancer [21] and a meta-analysis showed that body mass index (BMI) was the second relevant risk factor for NETs development after family history of cancer in all investigated sites [22]. In a series of non-functioning GEP NETs patients, we recently demonstrated that metabolic syndrome was associated with greater severity of the tumor, in terms of higher tumor size and Ki67% proliferation index [23]. Conversely, the “obesity paradox” suggests that higher BMI reduces mortality risk in cancer patients, despite a greater risk of cancer associated with higher BMI. According to a large database analysis of over 22.000 patients with abdominal NETs who underwent surgery between 2009 and 2010, obesity seems to be a protective factor against inpatient mortality [24]. This is a very debated topic and definitely a detailed analysis of body composition could clarify the relationship between cancer and obesity [25].

Data about nutrition in NETs are scattered [16, 18, 23] and large epidemiological studies, as well as randomized clinical trials are lacking. The aim of this review is to critical discuss the role of nutrition and body composition on progression in patients with NETs.

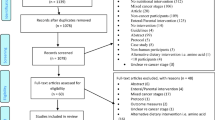

2 Search strategy and selection criteria

Relevant literature was searched in PubMed/Medline, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library up to April 2018, using at least one of the following specific keywords: neuroendocrine tumors, nutrition, Mediterranean Diet, obesity, lifestyle, body mass index, bioelectrical impedance analysis, phase angle, somatostatin analogs, everolimus, sunitinib, temozolomide, food interaction. Boolean operators were used to improve the precision of each search. Studies that were not in English language, letters to editor, abstracts to conferences and those without availability of full test were excluded. All included studies were screened and discussed by the authors until a general consensus was reached.

3 Nutrition and NETs

Several epidemiological studies support the theory that diet plays an important role in the initiation, promotion and progression of cancers in Western countries [26, 27]. In particular, nutritional status in NETs, especially GEP, is deeply affected by their excessive production of gastrointestinal hormones, peptides, and amines, which can lead to malabsorption, diarrhea, steatorrhea, and altered gastrointestinal motility [23, 28]. Besides the tumor production of regulatory gastrointestinal peptides, the surgical management of NETs that remove or alter the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract, or biotherapy with synthetic SSA that suppress the secretion of pancreatic enzymes as well as of gastrointestinal pancreatic hormones and function, can lead to alteration of gastrointestinal secretory, motor, and absorptive functions, with both dietary and nutritional consequences [23]. This points out how there is an urgent need for consistent, evidence-based medicine nutritional guidelines for patients with NETs.

In line with the American Cancer Society, it is recommended to eat at least five portions/servings (at least 400 g) of a variety of non-starchy vegetables and fruit every day, limited consumption of red and processed meat, that should be limited to less than 500 g a week, limited consumption of alcohol, that should be limited to no more than two drinks a day for men and one drink per day for women, eat relatively unprocessed cereals (grains) and/or legumes with every meal and limit their intake of refined starchy foods [29]. An intake of less than 6 g of salt (2.4 g sodium) a day was recommended, thereby avoiding salt-preserved, salted or salty foods. In addition to the above, energy-dense foods, as well as fast foods, should be consumed sparingly and sugary drinks should be avoided [29]. The constituents of these food groups seem to explain the biochemical mechanisms by which diet can affect tumor pathogenesis. Indeed, fruits and vegetables are important sources of a wide variety of micronutrients and other bioactive compounds, including antioxidants (such as vitamin C and E), folate, carotenoids, glucosinolates, indoles, isothiocyanates, protease inhibitors and phytochemicals (lycopene, phenolic compounds, flavonoids etc.), which have been demonstrated to exhibit anticancer properties [30, 31]. All these compounds may act against cancer through different mechanisms, including their antioxidant, anti-mutagenic and anti-proliferative properties. In addition, modulation of the immune and endocrine systems and metabolic pathways have been proposed as adjunctive mechanisms [30, 31].

Similar to other different cancers, the overall goals of nutritional approaches for a NET patient is to develop individualized nutrition care plans, to promote optimal nutritional status, to evaluate the effectiveness of nutritional interventions, to improve the quality of life of the patient during therapy, depending also on whether or not the patient is symptomatic, the stage of the disease, and the type of therapeutic management. Thus, a skilled nutritionist should be part of the multidisciplinary health care team in NET management, adapting the specific nutritional needs to the course of NETs. Despite the pioneering work of Warner’s available at the Carcinoid Cancer Foundation [32], up to now there are no dietary guidelines developed specifically for NETs.

For patients with newly diagnosed asymptomatic NETs, it is useful to follow recommendations by the healthy diet based on the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee [33, 34]. However, due to the advancement of therapeutic and diagnostic procedures, most NET patients, mainly GEP, are cancer survivors. According to the American Cancer Society [35], the major nutritional recommendation for all cancer survivors regarding lifestyle is to eat at least five servings of fruits and vegetables per day [35]. In general, the patients with advanced cancer are often protein and fatty-acid deficient, with a close link with the decrease in skeletal muscle mass [36] and weight loss. Changes in food preferences and dietary habits are also commonly noted in advanced cancer, thereby exacerbating nutrient insufficiencies [37]. In addition, nutrition status may directly affect both tolerance to and effectiveness of palliative chemotherapy treatments for solid tumors [38].

Considering the most common symptoms in NETs, which includes diarrhea, abdominal pain, gas and bloating, flushing and, to a lesser extent, fatigue, weakness, weight loss, and skin rash, there are some key nutritional advices for this group of patients. To prevent flushing it is mandatory to avoid spicy foods and alcoholic beverages. To help the management of diarrhea by the underlying endocrine tumors, NET patients should substitute raw, high-fiber fruits and vegetables, thereby introducing ripe bananas, pureed vegetables, cooked fruits, rice, pasta, and potatoes. Additionally, jam or jelly on whole grain bread should be used instead of cream cheese or butter on white bread; clear broth soup instead of creamy soup; crackers or pretzels in place of doughnuts and butter cookies; electrolyte replacements drinks, such as Gatorade, instead of carbonated soft drinks or fruit juice with pulp; and lactose-free beverages and products instead of regular milk and dairy products [33]. Therapy with SSA [39], which suppress the gastrointestinal tract and pancreatic function, can lead to altered fat and fat-soluble vitamin absorption [39], while systemic chemotherapy and combination therapy with SSA, interferon, mTOR inhibitors, or vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors cause anorexia, weight loss, and liver function abnormalities [40, 41].

An additional nutritional consideration in NET management is to supplement the intake of rich foods in niacin. Niacin deficiency, which can result from the increased tryptophan metabolism into serotonin, could lead to dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia, and pellagra. Supplementation with niacin 25 to 50 mg/day are recommended [42]. Furthermore, pancreatic enzymes, such as pancrease, creon, and ultrase, and supplementations with fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K, are particularly recommended for patients with fat malabsorption and steatorrhea, particularly related to therapy with SSA [43]. About the use of nutraceuticals or other dietary supplements there is scant evidence, and as these products may interfere with various chemotherapies, they should be used with caution.

There is considerable evidence that the Mediterranean diet (MD) represents a dietary pattern suitable in the prevention of non-communicable diseases, including cancer [44,45,46,47]. A meta-analysis including both cohort and case-control studies investigating the effects of adherence to MD on overall cancer risk evidenced that a high adherence to a MD is associated with a significant reduction in the risk of overall cancer mortality (10%), colorectal cancer (14%), prostate cancer (4%) and aerodigestive cancer (56%) [48]. A few prospective cohort studies investigated the association between composition of diet and cancer survival, reporting inconsistent results [49]. For example, several studies focused on the evaluation of the relationship between survival and single nutrients rather than dietary patterns [49, 50]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated in volunteers recruited for the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study that the adherence to a traditional Italian MD may help to prevent weight gain and abdominal obesity [51]. The beneficial effects of nutritional interventions promoting the Mediterranean food pattern could be extended to NETs patients. Future well-designed dietary intervention trials on larger population samples are needed to define specific dietary guidelines for NETs.

4 Body composition and NETs

There is convincing evidence that excess body fat is a cause of several cancers [21]. Arnold et al. recently estimated that 3.6% of all incident cancers in the world in 2013 were caused by obesity [52]. A meta-analysis indicated that the increase in the risk of developing cancer for every 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI ranged from 9 to 56% [53, 54]. The BMI is inexpensive and easily measured, and is considered a commonly used surrogate for evaluating adiposity. Nevertheless, BMI evaluates excess weight rather than excess fat [55,56,57], as it does not measure body fat directly, and poorly distinguishes between fat mass and lean or bone mass [58]. A recently published meta-analysis reported that, among risk factors for NETs, family history of cancer is the most relevant risk factor for NET development at all investigated sites, followed by BMI and diabetes [22]. Nevertheless, NET-related weight loss due to malnutrition is a frequently encountered yet underestimated clinical event, with relevant prognostic and socioeconomic implications for affected patients and caregivers [59].

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) and its derived parameter phase angle (PhA) have been widely used in different populations [60, 61]. BIA is a non-invasive diagnostic tool for the evaluation of body composition, which measures resistance to an electrical current and extrapolates fluid and fat compartments from this measurement [62]. The parameters that can be measured include hydration status (intracellular, extracellular and total water content), body fat mass, and electrolyte composition, which are essential in determining the overall health status [63, 64]. Malnutrition-associated patterns of body composition are increased extracellular mass (ECM), which is largely defined by extracellular water, and decreased body cell mass (BCM) [62, 65]. The PhA is an indicator for cell membrane integrity, water distribution between the intra- and extracellular spaces and prediction of body cell mass, which is most commonly evaluated and correlated with nutritional status and survival rate [66, 67]. Several studies indicate that the use of BIA and PhA measures can benefit in the clinical management of cancer patients in the prevention, diagnosis, prognosis and in nutritional intervention [68]. The best use of BIA measurements is the evaluation of individuals over time to provide for longitudinal changes of PhA along with disease progression and treatment. In this context, it is important to remind that the evaluation of the beneficial effect of therapeutic nutritional interventions should be monitored by BIA and not only via BMI, because this may be misleading in cases such as edema. Recently, our group has reported a novel association between the adherence to the Mediterranean diet and PhA, independently of sex, age, and body weight, recommending the nutrition assessment as good clinical practice in the clinical settings [61]. Thus, BIA and PhA may be particularly useful also to evaluate and predict outcomes related to symptom management of patients with NETs, whose nutritional status and the symptoms are clearly affected by their tumours.

5 Nutritional assessment of patients with NETs: the point of view of the nutritionist

The dietary evaluation in patients with cancer, in particular macro- and micronutrient, plays a central role in the management of these patients [69]. Disease-related malnutrition is frequently encountered in cancer patients, with substantial prognostic and socioeconomic implications [16]. A number of different studies have evidenced that malnutrition increases complication rates after oncological surgery, the duration of hospitalization mostly due to a higher number of infectious complications, and side effects of cytotoxic treatment, and decreases response to treatment and the quality of life on the other side, and ultimately a worse prognosis in malnourished cancer patients [16]. Thus, both regular nutritional assessment and nutritional therapy have been recommended to cancer patients with active disease or undergoing complete resection surgery to improve their clinical outcome [16].

As well as in other oncological diseases, malnutrition is a common problem in NET patients [16]. Few studies to date have investigated the association among NETs, nutrition and body composition [16, 18, 23]. Consequently, knowledge about this association and the possible usefulness of a nutritional treatment in NETs is still very limited [23, 28]. However, as in the majority of cases NET are characterized by a relatively slowly growing neoplasms, NET patients present only moderate ‘cachexia-inducing’ potential, which is also reflected in the global good long-term prognosis. Nevertheless, such as in other neoplasms, malnutrition is a relevant clinical problem in NET patients, with an impact on short- and long-term outcomes. Malnutrition might be an underestimated problem in NETs patients, which should systematically be diagnosed by widely available standard methods as nutritional status is an important independent prognostic factor for NETs besides their proliferative capacity, which influences treatment outcomes, treatment complications, quality of life and survival. The diagnosis of clinically manifest malnutrition can be established by using simple screening tools, such as the Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS), in association with widely available serum surrogate parameters of malnutrition (e.g. serum albumin levels) or measures of body composition, such as BIA, which can rather easily be integrated into clinical routine. The direct measurement of BIA parameters, such as PhA, represents a widely available method among NET inpatient and outpatient nutrition teams, as it provides an easily measureable, reproducible and valid marker of malnutrition.

The specific role of malnutrition for prognosis and patient management in NET patients has recently been reported by Maasberg et al. [16] using clinical scores, such as Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) or NRS, anthropometry, BIA, in particular PhA, and serum surrogate parameters, including albumin [16]. In this cross-sectional study the authors found that up to one quarter of NET patients were at risk of malnutrition, as defined by SGA and NRS, in particular those with high-grade (G3) tumors, with progressive disease and undergoing chemotherapy. In malnourished NET patients the duration of hospitalization was significantly longer, while long-term overall survival was significantly reduced, thereby confirming the role of malnutrition as an independent prognostic factor for NET besides proliferative capacity [16]. Additionally, malnutrition was associated with significantly poorer BIA parameters, and resulted in a decreased PhA and an increased ECM to BCM ratio, indicating the loss of BCM and an increase in ECM in malnourished NET patients compared with well-nourished counterpart [16]. Among clinical screening scores for the diagnosis of malnutrition, the NRS has been proven to represent a valid and simple tool for identifying patients at high risk of malnutrition or actually malnourished [16]. Of interest, the authors found that both the SGA and NRS identify moderately to severely malnourished NETs patients reliably.

Thus, BIA allows monitoring of nutritional status and body compositional changes during the disease and treatment course, helping set nutritional interventions, and it is recommended also in NET patients as a method for malnutrition assessment.

6 Food interaction on oral target therapy and antineoplastic agents

In patients with advanced progressive NETs, a targeted therapy with sunitinib or everolimus has been associated with a significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) over placebo [39]. The supposed long term treatment of NET imposes to rule out any possible toxicity and oral administration of therapy significantly improves the quality of life and allows home care, less interference with work and social activities, as well as avoidance of painful injection [70]. However, an interaction between food and orally administrated medications including oral antineoplastic agents has been shown. This is known as ‘food-drug interaction’, that can change the absorption rate or interact with the metabolism of specific drugs. In specific condition, this effect can be clinically relevant, particularly to optimize medical treatment and to avoid undesirable effects [71, 72]. Several mechanisms are involved in the food-drug interaction, including food categories, the postprandial digestive system physiology, as well as the pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic of the drug [71].

The most important mechanism involved in the pharmacokinetic of oral antineoplastic agents, is the superfamily of the cytochrome (CYP) P450 [73, 74]. Everolimus and sunitinib are both administered orally and are predominantly metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4, thus food that affect the CYP 3A4 could influence their metabolism [72]. It has been showed that grapefruit, a potent inhibitor of the CYP3A4, could increase the risk of everolimus toxicity and increase the plasma concentration of sunitinib and its active metabolites [72]. Other food-inhibitors of the CYP3A4 are camomile, cranberry, garlic, ginseng, green tea extract, pepper, resveratrol and soya [18]. A helpful website on this topic has been provided by Dr. Flockhart at the Indiana University, U.S.A., the ‘Cytochrom P450 Drug Interaction Table’, https://drug-interactions.medicine.iu.edu/Main-Table.aspx. (https://www.regionorebrolan.se/Files-sv/%C3%96rebro%20l%C3%A4ns%20landsting/Arbete_utbildning/ST/ST-psykiatri/inbjudan/Clinical-Table-CYP450.pdf).

Moreover, the absorption of the drugs depends on intestinal enzymes and transporters, among which the P-glycoprotein (Gp-P) that acts as a drug efflux pump and can limit the bioavailability of some orally administered drugs, including the inhibitors of tyrosine kinase, particularly everolimus but also sunitinib [72]. High-fat meal could inhibit the Gp-P, blocking the export of drugs with a consequent increased bioavailability of the drug [71]. High-fat meal also reduced the concentration time curve of everolimus [75].

CYP P450 enzymes play only a minor role in the metabolism of temozolomide which is spontaneously hydrolyzed at physiologic pH to its active species [76]. Therefore, food that modified the normal pH of the gastrointestinal tract may interfere with the pharmacokinetic of this drug and can reduce rate and extend of medication absorbed by body, increasing adverse effects [70].

In conclusion, grapefruit and other food that inhibit the CYP34A, as well as high-fat meal, are preferred to be avoided during the administration of everolimus and sunitinib, as well as it should be preferred to avoid the administration of temozolomide concomitant to a meal.

7 Conclusion

NETs have worldwide increasing incidence combined with high survival rate and prevalence [1]. Surgery remains the only curative treatment for early-stage disease [77], while somatostatin analogues represent the treatment of choice for unresectable/advanced disease, followed by peptide receptor-targeted radiotherapy and several drugs, such as targeted therapy and chemotherapy [15, 77, 78].

Both the tumor itself and the systemic therapy may have an impact on patients’ nutrition. Hormonal cosecretion such as seen with the ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone induced Cushing’s syndrome can impact metabolic, nutritional, and wound healing status [79]. However, data about nutrition in NETs are scattered and large epidemiological studies, as well as randomized clinical trials are lacking. A limited number of studies demonstrated that malnutrition negatively impacts on clinical outcome of NETs patients [16, 18] and that metabolic syndrome was associated with greater severity of the NETs [23]. Food could also interact with the metabolism of oral targeted therapy and antineoplastic agents used for the treatment of progressive NETs [70, 71], Fig. 1. Finally, adherence to the MD has been associated with the prevention of several cancers [45,46,47] as well as with a significant reduction in the risk of overall cancer mortality [48].

Both the tumor itself and the systemic therapy may have an impact on patients’ nutrition. The nutrition could interact with the oral target therapy and antineoplastic agents used for the treatment of progressive NETs. The nutritional assessment, based on body composition, should be an integral component of management of the NETs patients. This information is important either for Nutritionists and Endocrinologists for increases the knowledge and on the potential usefulness of nutrition, body composition evaluation and drugs interactions in NETs patients with the aim to reduce the comorbidities and improve the quality of life in these patients. Furthermore, these concepts suggests of a growing cooperation between Nutritionists and Endocrinologists in the complex management of the NETs patients

Therefore, the nutritional assessment, based on body composition, and lifestyle modifications should be an integral component of management of the NETs patients [23, 28]. These “easy” concepts might be of strategic relevance in terms of clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the newer drugs. The nutrition care plans are an integral part of the multidisciplinary management team for patients with NETs. Nutritionists with expertise in NETs can provide dietary approaches to improve the quality of life and nutritional status during various therapeutic modalities used in patients with NETs. They can monitor these patients and provide appropriate dietary changes to address the various side effects of therapy. The goal of these recommendations is to make NETs patients aware of beneficial dietary interventions. Achieving dietary-related goals includes an integrated effort of a trained team that involves the NET patients in the decision-making process. Analogous to guidelines for managing patients with metabolic surgery [80, 81], it should be recommended that in the NET team a leading role in providing nutrition care should be given to skilled nutritionists, about the dietary interventions and supporting nutrition and dietetic recommendations, and NET patients should actively participate in the decision-making process.

References

Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, et al. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(10):1335–42. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589.

Boyar Cetinkaya R, Aagnes B, Thiis-Evensen E, Tretli S, Bergestuen DS, Hansen S. Trends in incidence of neuroendocrine neoplasms in Norway: a report of 16,075 cases from 1993 through 2010. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1159/000442207.

Scherubl H, Streller B, Stabenow R, Herbst H, Hopfner M, Schwertner C, et al. Clinically detected gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are on the rise: epidemiological changes in Germany. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(47):9012–9. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.9012.

Petersenn S, Koch CA. Neuroendocrine neoplasms - still a challenge despite major advances in clinical care with the development of specialized guidelines. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18(4):373–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-018-9442-7.

Rindi G, Arnold R, Capella C, Klimstra DS, Klöppel G, Komminoth P, et al. Nomenclature and classification of digestive neuroendocrine tumours. In: WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. WHO Classification of Tumours, Volume 3. IARC; 2010. ISBN-13 9789283224327.

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG. WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. 4th ed. WHO Classification of Tumours, Volume 7. IARC; 2015. ISBN-139789283224365.

Faggiano A, Ferolla P, Grimaldi F, Campana D, Manzoni M, Davi MV, et al. Natural history of gastro-entero-pancreatic and thoracic neuroendocrine tumors. Data from a large prospective and retrospective Italian epidemiological study: the NET management study. J Endocrinol Investig. 2012;35(9):817–23. https://doi.org/10.3275/8102.

Anlauf M, Garbrecht N, Bauersfeld J, Schmitt A, Henopp T, Komminoth P, et al. Hereditary neuroendocrine tumors of the gastroenteropancreatic system. Virchows Arch. 2007;451(Suppl 1):S29–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-007-0450-3.

Krauss T, Ferrara AM, Links TP, Wellner U, Bancos I, Kvachenyuk A, et al. Preventive medicine of von Hippel-Lindau disease-associated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(9):783–93. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-18-0100.

Glasker S, Neumann HPH, Koch CA, Vortmeyer AO. Von Hippel-Lindau disease. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, Feingold KR, Grossman A, Hershman JM et al, editors. South Dartmouth, MA: Endotext; 2000.

Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, Bartsch DK, Capdevila J, Caplin M, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of patients with functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103(2):153–71. https://doi.org/10.1159/000443171.

Zandee WT, Kamp K, van Adrichem RC, Feelders RA, de Herder WW. Effect of hormone secretory syndromes on neuroendocrine tumor prognosis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24(7):R261–R74. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-16-0538.

Hallet J, Law CH, Cukier M, Saskin R, Liu N, Singh S. Exploring the rising incidence of neuroendocrine tumors: a population-based analysis of epidemiology, metastatic presentation, and outcomes. Cancer. 2015;121(4):589–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29099.

Pavel M, O'Toole D, Costa F, Capdevila J, Gross D, Kianmanesh R, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of distant metastatic disease of intestinal, pancreatic, bronchial neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN) and NEN of unknown primary site. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103(2):172–85. https://doi.org/10.1159/000443167.

Frost M, Lines KE, Thakker RV. Current and emerging therapies for PNETs in patients with or without MEN1. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(4):216–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2018.3.

Maasberg S, Knappe-Drzikova B, Vonderbeck D, Jann H, Weylandt KH, Grieser C, et al. Malnutrition predicts clinical outcome in patients with neuroendocrine neoplasia. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104(1):11–25. https://doi.org/10.1159/000442983.

Lis CG, Gupta D, Lammersfeld CA, Markman M, Vashi PG. Role of nutritional status in predicting quality of life outcomes in cancer--a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. 2012;11:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-11-27.

Ekeblad S, Skogseid B, Dunder K, Oberg K, Eriksson B. Prognostic factors and survival in 324 patients with pancreatic endocrine tumor treated at a single institution. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(23):7798–803. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0734.

Marrache F, Vullierme MP, Roy C, El Assoued Y, Couvelard A, O'Toole D, et al. Arterial phase enhancement and body mass index are predictors of response to chemoembolisation for liver metastases of endocrine tumours. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(1):49–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603526.

Qureshi SA, Burch N, Druce M, Hattersley JG, Khan S, Gopalakrishnan K, et al. Screening for malnutrition in patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e010765. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010765.

Byers T, Sedjo RL. Body fatness as a cause of cancer: epidemiologic clues to biologic mechanisms. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22(3):R125–34. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-14-0580.

Leoncini E, Carioli G, La Vecchia C, Boccia S, Rindi G. Risk factors for neuroendocrine neoplasms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(1):68–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv505.

Gallo M, Muscogiuri G, Pizza G, Ruggeri RM, Barrea L, Faggiano A, et al. The management of neuroendocrine tumours: a nutritional viewpoint. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2017.1390729.

Glazer E, Stanko K, Ong E, Guerrero M. Decreased inpatient mortality in obese patients with abdominal Nets. Endocr Pract. 2014:1–20. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP14203.OR.

Caan BJ, Cespedes Feliciano EM, Kroenke CH. The importance of body composition in explaining the overweight paradox in cancer-counterpoint. Cancer Res. 2018;78(8):1906–12. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3287.

Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, Bandera EV, McCullough M, McTiernan A, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(5):254–81 quiz 313-4.

Longo VD, Fontana L. Calorie restriction and cancer prevention: metabolic and molecular mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31(2):89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2009.11.004.

Jin XF, Spampatti MP, Spitzweg C, Auernhammer CJ. Supportive therapy in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: often forgotten but important. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-018-9443-6.

Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, Rock CL, Demark-Wahnefried W, Bandera EV, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):30–67. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20140.

Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, Zhu M, Zhao G, Bao W, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2014;349:g4490. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g4490.

Turati F, Rossi M, Pelucchi C, Levi F, La Vecchia C. Fruit and vegetables and cancer risk: a review of southern European studies. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(Suppl 2):S102–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114515000148.

Warner ME. Nutritional concerns for the carcinoid patient: developing nutrition guidelines for persons with carcinoid disease., https://www.carcinoid.org/for-patients/general-information/nutrition/nutritional-concerns-for-the-carcinoid-patient-developing-nutrition-guidelines-for-persons-with-carcinoid-disease/. 2008 update. Accessed 16 May 2018.

Go VL, Srihari P, Kamerman Burns LA. Nutrition and gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2010;39(4):827–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2010.08.003.

Promotion. USDoHaHSOoDPaH. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/?_ga=2.93506781.1509651194.1526503567-2137365160.1526503567. Accessed 16 May 2018.

Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. American Cancer Society’s SCS, II. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(13):2198–204. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6217.

Murphy RA, Mourtzakis M, Chu QS, Reiman T, Mazurak VC. Skeletal muscle depletion is associated with reduced plasma (n-3) fatty acids in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Nutr. 2010;140(9):1602–6. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.123521.

Hutton JL, Martin L, Field CJ, Wismer WV, Bruera ED, Watanabe SM, et al. Dietary patterns in patients with advanced cancer: implications for anorexia-cachexia therapy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(5):1163–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/84.5.1163.

Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, Reiman T, Sawyer MB, Martin L, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(7):629–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70153-0.

Pavel M, Valle JW, Eriksson B, Rinke A, Caplin M, Chen J, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines for the standards of care in neuroendocrine neoplasms: systemic therapy - biotherapy and novel targeted agents. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105(3):266–80. https://doi.org/10.1159/000471880.

Yao JC, Phan AT, Chang DZ, Wolff RA, Hess K, Gupta S, et al. Efficacy of RAD001 (everolimus) and octreotide LAR in advanced low- to intermediate-grade neuroendocrine tumors: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(26):4311–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.16.7858.

Yao JC, Phan A, Hoff PM, Chen HX, Charnsangavej C, Yeung SC, et al. Targeting vascular endothelial growth factor in advanced carcinoid tumor: a random assignment phase II study of depot octreotide with bevacizumab and pegylated interferon alpha-2b. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1316–23. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6374.

Vinik AI, Anthony L, Boudreaux JP, Go VL, O'Dorisio TM, Ruszniewski P, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors: a critical appraisal of management strategies. Pancreas. 2010;39(6):801–18. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ea5839.

Plockinger U, Wiedenmann B. Diagnosis of non-functioning neuro-endocrine gastro-enteropancreatic tumours. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80(Suppl 1):35–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000080739.

Sofi F, Macchi C, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Mediterranean diet and health status: an updated meta-analysis and a proposal for a literature-based adherence score. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(12):2769–82. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013003169.

Castello A, Amiano P, Fernandez de Larrea N, Martin V, Alonso MH, Castano-Vinyals G, et al. Low adherence to the western and high adherence to the mediterranean dietary patterns could prevent colorectal cancer. Eur J Nutr. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1674-5.

Castello A, Pollan M, Buijsse B, Ruiz A, Casas AM, Baena-Canada JM, et al. Spanish Mediterranean diet and other dietary patterns and breast cancer risk: case-control EpiGEICAM study. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(7):1454–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.434.

Romaguera D, Gracia-Lavedan E, Molinuevo A, de Batlle J, Mendez M, Moreno V, et al. Adherence to nutrition-based cancer prevention guidelines and breast, prostate and colorectal cancer risk in the MCC-Spain case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(1):83–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30722.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(8):1884–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28824.

Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):243–74. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21142.

Jones LW, Demark-Wahnefried W. Diet, exercise, and complementary therapies after primary treatment for cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(12):1017–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70976-7.

Agnoli C, Sieri S, Ricceri F, Giraudo MT, Masala G, Assedi M, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and long-term changes in weight and waist circumference in the EPIC-Italy cohort. Nutr Diabetes. 2018;8(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-018-0023-3.

Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, Renehan PAG, Stevens GA, Ezzati PM, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(1):36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71123-4.

Freisling H, Arnold M, Soerjomataram I, O'Doherty MG, Ordonez-Mena JM, Bamia C, et al. Comparison of general obesity and measures of body fat distribution in older adults in relation to cancer risk: meta-analysis of individual participant data of seven prospective cohorts in Europe. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(11):1486–97. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.106.

Kyrgiou M, Kalliala I, Markozannes G, Gunter MJ, Paraskevaidis E, Gabra H, et al. Adiposity and cancer at major anatomical sites: umbrella review of the literature. BMJ. 2017;356:j477. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j477.

Okorodudu DO, Jumean MF, Montori VM, Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Erwin PJ, et al. Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2010;34(5):791–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.5.

Koch CA, Bornstein SR, Birkenfeld AL. Introduction to Hanefeld symposium: 40+ years of metabolic syndrome. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2016;17(1):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-016-9356-1.

Melcescu E, Griswold M, Xiang L, Belk S, Montgomery D, Bray M, et al. Prevalence and cardiometabolic associations of the glucocorticoid receptor gene polymorphisms N363S and BclI in obese and non-obese black and white Mississippians. Hormones (Athens). 2012;11(2):166–77.

De Lorenzo A, Bianchi A, Maroni P, Iannarelli A, Di Daniele N, Iacopino L, et al. Adiposity rather than BMI determines metabolic risk. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166(1):111–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.006.

Norman K, Pichard C, Lochs H, Pirlich M. Prognostic impact of disease-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2008;27(1):5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2007.10.007.

Stefanaki C, Peppa M, Boschiero D, Chrousos GP. Healthy overweight/obese youth: early osteosarcopenic obesity features. Eur J Clin Investig. 2016;46(9):767–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12659.

Barrea L, Muscogiuri G, Macchia PE, Di Somma C, Falco A, Savanelli MC, et al. Mediterranean diet and phase angle in a sample of adult population: results of a pilot study. Nutrients. 2017;9(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9020151.

Barbosa-Silva MC, Barros AJ, Wang J, Heymsfield SB, Pierson RN Jr. Bioelectrical impedance analysis: population reference values for phase angle by age and sex. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1):49–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn.82.1.49.

Macinnis RJ, English DR, Gertig DM, Hopper JL, Giles GG. Body size and composition and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004;13(12):2117–25.

MacInnis RJ, English DR, Hopper JL, Haydon AM, Gertig DM, Giles GG. Body size and composition and colon cancer risk in men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004;13(4):553–9.

Norman K, Stobaus N, Pirlich M, Bosy-Westphal A. Bioelectrical phase angle and impedance vector analysis--clinical relevance and applicability of impedance parameters. Clin Nutr. 2012;31(6):854–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2012.05.008.

Paiva SI, Borges LR, Halpern-Silveira D, Assuncao MC, Barros AJ, Gonzalez MC. Standardized phase angle from bioelectrical impedance analysis as prognostic factor for survival in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19(2):187–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0798-9.

Norman K, Stobaus N, Zocher D, Bosy-Westphal A, Szramek A, Scheufele R, et al. Cutoff percentiles of bioelectrical phase angle predict functionality, quality of life, and mortality in patients with cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(3):612–9. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.29215.

Grundmann O, Yoon SL, Williams JJ. The value of bioelectrical impedance analysis and phase angle in the evaluation of malnutrition and quality of life in cancer patients--a comprehensive review. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(12):1290–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2015.126.

Ravasco P, Monteiro Grillo I, Camilo M. Cancer wasting and quality of life react to early individualized nutritional counselling! Clin Nutr. 2007;26(1):7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2006.10.005.

Segal EM, Flood MR, Mancini RS, Whiteman RT, Friedt GA, Kramer AR, et al. Oral chemotherapy food and drug interactions: a comprehensive review of the literature. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(4):e255–68. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2013.001183.

Deng J, Zhu X, Chen Z, Fan CH, Kwan HS, Wong CH, et al. A review of food-drug interactions on Oral drug absorption. Drugs. 2017;77(17):1833–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-017-0832-z.

Collado-Borrell R, Escudero-Vilaplana V, Romero-Jimenez R, Iglesias-Peinado I, Herranz-Alonso A, Sanjurjo-Saez M. Oral antineoplastic agent interactions with medicinal plants and food: an issue to take into account. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(11):2319–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-016-2190-8.

Haefeli WE, Carls A. Drug interactions with phytotherapeutics in oncology. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10(3):359–77. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425255.2014.873786.

Zanger UM, Schwab M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138(1):103–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007.

Kovarik JM, Hartmann S, Figueiredo J, Rordorf C, Golor G, Lison A, et al. Effect of food on everolimus absorption: quantification in healthy subjects and a confirmatory screening in patients with renal transplants. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(2):154–9.

Hammond LA, Eckardt JR, Baker SD, Eckhardt SG, Dugan M, Forral K, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of temozolomide on a daily-for-5-days schedule in patients with advanced solid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2604–13. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2604.

Thomaschewski M, Neeff H, Keck T, Neumann HPH, Strate T, von Dobschuetz E. Is there any role for minimally invasive surgery in NET? Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18(4):443–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-017-9436-x.

Angelousi A, Kaltsas G, Koumarianou A, Weickert MO, Grossman A. Chemotherapy in NETs: when and how. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18(4):485–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-017-9432-1.

Singer J, Werner F, Koch CA, Bartels M, Aigner T, Lincke T, et al. Ectopic cushing’s syndrome caused by a well differentiated ACTH-secreting neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ileum. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118(8):524–9. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1243634.

Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM, Livingston E, Salvador J, Still C, et al. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):4823–43. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-2128.

Bays H, Kothari SN, Azagury DE, Morton JM, Nguyen NT, Jones PH, et al. Lipids and bariatric procedures Part 2 of 2: scientific statement from the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS), the National Lipid Association (NLA), and Obesity Medicine Association (OMA). Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(3):468–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2016.01.007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human rights and on the welfare of animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Altieri, B., Barrea, L., Modica, R. et al. Nutrition and neuroendocrine tumors: An update of the literature. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 19, 159–167 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-018-9466-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-018-9466-z