Abstract

This paper formulates a model to examine the effects of changes in tax-benefit policy on the behavior of divorced parents and the well-being of children in single-parent households. Noncustodial parents choose the level of a child support payment to transfer to custodians. These, in turn, decide over child good expenditures and the allocation of time between market work and parenting. Our main finding shows that welfare policies that subsidize childcare expenditures or reduce withdrawal rates, which are most certainly intended to improve the conditions of working single parents and their children, could actually have the reverse effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

When it comes to improving the economic circumstances of low income parents, policy makers increasingly turn to the tax and benefit system for solutions. For example, one of the key objectives of the “making work pay” agenda in the United States, Canada, and Britain has been to boost in-work benefits offered to low-income parents (especially single mothers) through more generous amounts of tax credits, lower withdrawal (phase-out) rates, and substantial childcare subsidies. Examples include the policies implemented through the American Earned Income Tax Credit, the Canadian Self-Sufficiency Program, and the British Working Families’ Tax Credit and Working Tax Credit.

Despite the popularity of these reforms among policy makers, however, the ways in which they may affect the overall welfare of low-income families is often not fully understood. In particular, little is known about behavioral responses to tax-benefit reforms that have an adverse impact on child well-being in lone parent families. A growing body of empirical research documents that changes in tax and benefit policies can have or have had unfavorable effects on single mothers’ well-being (e.g., Bitler et al. 2002, 2005; Francesconi and van der Klaauw 2007; Baker et al. 2008; Grogger and Karoly 2009; Brewer et al. 2009) as well as on a wide array of their children’s outcomes (e.g., Gennetian et al. 2002, 2005; Baker et al. 2008; Herbst and Tekin 2008; Grogger and Karoly 2009; Gregg et al. 2009). There is still insufficient appreciation for the ramifications of such unintended or unanticipated consequences of welfare reform. The contribution of this paper, therefore, is to provide a new theoretical setup that can coherently explain these undesirable effects and can also deliver testable implications on child welfare and on the strategic interaction between divorced parents.

Our study is based on the seminal contributions by Weiss and Willis (1985, 1993) and Del Boca and Flinn (1995). These studies, which treat labor supply decisions and post-divorce incomes of former spouses as exogenous, provide a formal analysis of the noncooperative behavior of divorced parents in terms of child support transfers and expenditures on children. We build on these earlier studies by (i) modeling the labor supply decision of the custodial parent and (ii) explicitly incorporating the tax-benefit program.

We then focus on the effects of tax-benefit policy changes on divorced parents’ labor supply, consumption and child support transfer decisions and on child well-being in single parent households. We posit that child well-being is determined by the combination of purchased goods and parental time, which in the case of single parent households reduces to the time allocated by the custodial (lone) parent only. For simplicity, the time devoted to the child by the noncustodial parent is assumed to have no effect on child well-being. In this environment, divorced parents make three decisions in a one-shot noncooperative game with a sequential two-stage structure. First, the noncustodial parent chooses the amount of child support payment to transfer to the custodial parent, and the then custodial parent decides over both child good expenditures and the allocation of time between market work and childcare. Each parent has preferences defined over own consumption and child welfare. Child welfare depends positively on expenditures and the amount of time the child spends with the custodial parent. One hour spent away from the custodial parent (for instance, in formal daycare, while the mother works) is assumed to contribute less (is less productive) to child welfare than one hour spent with the mother. Child welfare therefore is a local public good from the point of view of both parents, although only the custodial parent gets to decide how much to spend on child goods and how to allocate time between paid work and parenting.

With this setup, we first characterize the noncooperative behavior of divorced parents in terms of child support payments, time allocated to parenting, and child good expenditures. Because the noncustodial parent does not bargain with the custodial parent over the expenditure and time allocation decisions, it is not feasible for the ex-spouses to reach a Pareto efficient allocation of their resources. As a consequence, the noncustodian provides less than efficient child support transfers. The custodian, instead, not only spends too little on child goods, but also devotes too much time to market work and too little to childcare. Thus, the inefficiencies that arise in our framework are threefold and correspond to the three parental decisions under analysis: on the custodial side, child quality suffers because of inefficiently high levels of labor supply and inefficiently low expenditures on child goods, and on the noncustodial side child support payments are suboptimally low. Footnote 1

Using this framework, we then investigate the impact of policy reforms that are meant to improve lone parents’ well-being. We document that more generous government transfers provided to custodial parents (in the form of, say, income support or child tax credits) increase well-being of both custodial and noncustodial parents as well as that of their children. This is a straightforward result. A new result, instead, emerges when we look at the effect of increasing the custodian’s effective wage, through either greater childcare subsidies or lower withdrawal (phase-out) rates or both. While standard theory suggests that an exogenous increase in the effective wage rate should raise lone mothers’ well-being (although not necessarily that of their children), in our model it can reduce the utility of divorced custodial parents and depress the welfare of their children. This is because an increase in the mother’s effective wage reinforces the inefficiencies induced by noncooperation. That is, such an increase further depresses child support transfers from noncustodial fathers and accentuates over-work among custodial mothers. This greater labor supply is the net effect of a direct substitution effect (i.e., the opportunity cost of not engaging in paid work goes up) and a strategic multiplier effect (i.e., a response to the reduced child support transfer from the noncustodian). There are circumstances (that we shall characterize later) in which these effects interact so as to offset the positive income effect to depress divorced parents’ utility and child welfare.

This finding provides an important insight that has been overlooked so far: welfare policies that subsidize childcare expenditures or reduce withdrawal rates, which are most certainly intended to improve the conditions of working single parents and their children, could actually have the reverse effect. However, our model also suggests that increases in the quality of non-maternal child care reduce the adverse effects that the provision of child care subsidies may have on children and their parents. From a policy perspective, these findings suggest that policies aimed at increasing the effective wage of lone parents should be accompanied by efforts to improve the quality of non-maternal child care. In an extension of our basic model, we show that these implication are robust to the inclusion of issues of compliance with child support awards imposed by external institutional agents (e.g., courts or judges).

The remainder of the paper is as follows. The next section discusses the links of our contribution to the relevant literature. Section 3 sets up the basic model, while Sect. 4 provides the main equilibrium analysis and illustrates the effects of tax-benefit changes on divorced parents’ and children’s well-being. Section 5 explores an extension of the basic model in detail, i.e., compliance with court-mandated child support orders by the noncustodial parent. Section 6 relates our theoretical results to some of the existing empirical evidence and discusses some ideas for future research. For the sake of brevity, all proofs and some mathematical derivations are not presented here, but can be found in Francesconi et al. (2008).

2 Related literature

Our model is closely related to the work by Weiss and Willis (1985) and Del Boca and Flinn (1995). Weiss and Willis (1985) address the question of why many divorced fathers allow their children’s welfare to suffer as a consequence of divorce. Children are treated as collective consumption goods from the point of view of both parents. Within marriage parents’ cooperative behavior allows them to overcome the inefficiencies typically associated with public goods provision. Footnote 2 Upon divorce, however, the noncustodial parent cannot bargain over the expenditure decisions with the custodial parent. This, in turn, prevents the ex-spouses from reaching an efficient allocation of their resources, with the noncustodial parent making inadequate child support payments and the custodial parent devoting too few material resources to child goods. Footnote 3 Our paper focuses in addition to expenditures on children on the amount of time the custodial parent spends with child. We find that both inputs in child welfare are inefficiently low.

Del Boca and Flinn (1995) develop a noncooperative framework in which both child support compliance decisions of noncustodial fathers and court-mandated child support awards can be rationalized. Structural estimates of their model, which qualitatively replicate the observed distribution of child support payments, can be used to infer the implicit weights assigned by courts to the post-divorce welfare of both parents and children. The results indicate that the weight attached to the combined welfare of custodial mothers and their children is smaller than the weight attached to the welfare of noncustodial fathers. Courts may therefore set relatively low child support orders not only because they are concerned with fathers’ noncompliance but also because they assign a large weight on fathers’ welfare. As illustrated in Sect. 5, extending our basic framework to a model that incorporates child support orders does not alter our main results.

Although our paper focuses on the interactions between divorced parents, the approach of the paper also has much in common with bargaining models of household decisions among married couples used in recent contributions, such as Grogger and Karoly (2009) and Francesconi et al. (2009). Both these studies point out that work-conditioned transfer programs can cause the likelihood of divorce either to rise or to fall. This is because such programs may alter the non-marital options faced by single mothers and, at the same time, they may also affect the marital utility-possibility frontier. Likewise, changes in one spouse’s nonmarital alternatives induced by in-work benefit reform could affect child well-being through their influence on intrahousehold resource allocations, and this relationship again is likely to be ambiguous.

3 The basic framework

The goal of our analysis is to understand how changes in the tax-benefit system, and especially in in-work benefits (such as EITC and WFTC), affect the behavior of divorced parents. Consider a non-intact family that is comprised of a child, a custodial mother m, and a nonresident/noncustodial father f. Each parent i (i = f, m) has preferences defined over private consumption, x i , and child welfare, C. Child welfare depends on both childcare quality, q, and child good expenditures, k, and is produced according to

where the parameters a and b are such that 0 < a < 1, 0 < b < 1 and a + b < 1 which implies that the function F is strictly increasing in each of its arguments and is strictly concave. Parental preferences are represented by Cobb–Douglas utilities: Footnote 4

where γ f and γ m , which represent the preference weights on own consumption for the father and the mother respectively, are assumed to be contained in the open unit interval. It is useful to define

as parent i’s (i = f, m) productivity-weighted preferences over k and q, respectively. Substituting (1) into (2) and using (3), the parent’s utility functions can be re-written as

For simplicity (but also reflecting the prevailing norm in living arrangements among divorced parents), we assume that the mother has legal and physical custody of the child. Footnote 5 Under this sole custody assumption, the mother controls both childcare quality (q) and child good expenditures (k), while the father cannot influence (e.g., through a bargaining process) his ex-spouse’s resource allocation directly. The only way in which the father can affect q and k is through child support payments, s, which are transferred to the mother. The interactions we are interested in are those between the mother and the father. In the background, besides the child, there is however another inactive player, namely a welfarist government that may choose some key institutional variables, such as in-work benefit levels and childcare subsidies to daycare costs.

We envisage a two-stage game between m and f, which unfolds as follows. In stage 1, the father chooses the monetary level of child support, s, to transfer to the mother. Footnote 6 Assuming that the father’s labor supply is fixed and that he has income \(\mathbf{y}>0, s\) lies in \([0,\mathbf{y}]\). In stage 2, s is received (and observed) by the mother. The mother, who has a unit of active time endowment, spends the fraction l ∈ [0,1) of time working in the labor market and the remaining fraction h = 1 − l in childcare activities. Having chosen l, the mother then decides on how to divide her after-tax income between private consumption, x m , and child good expenditures, k. Footnote 7

To keep our analysis simple, leisure decisions are not modeled. Thus, h can be viewed as maternal time input used to produce childcare quality q. Specifically, we assume that q is produced according to a technology that is linear in both the fraction of time the custodial mother spends with the child (1 − l) and the fraction of time the child is looked after by someone else while the mother works (l). Footnote 8, Footnote 9 In particular,

where ψ < 1 and hence δ > 0. In setting the marginal quality of the mother’s time to 1 and the marginal quality of purchased care to ψ < 1, we follow Ermisch (2003) and assume that “outside care” is not a perfect substitute for the mother’s time. Footnote 10, Footnote 11

Since a working single mother must rely on childcare and if this must be paid for, she faces an effective wage which falls short of her after-tax wage by the hourly price of childcare. Formally, if we denote by w > 0 the mother’s hourly wage rate and by p > 0 the hourly price of formal childcare, the mother’s effective wage rate is

where τ is the marginal rate of income tax. The government might raise the mother’s effective wage \(\mathbf{w}\) by reducing the marginal rate of income tax (lower τ) or by providing more generous childcare subsidies (lower p). The after-tax income of the mother is then

where B ≥ 0 denotes government transfers (e.g., income support, child benefit, and child tax credit) and s is the child support payment from the noncustodial father. Throughout our analysis, we will maintain the following simplifying restriction on the model parameters:

Assumption 1

This places a lower bound (\(\underline{\mathbf{w}}\)) and an upper bound (\(\overline{\mathbf{w}}\)) on the value of the mother’s effective wage rate, \(\mathbf{w}\). Footnote 12 As will become apparent later, the upper bound ensures that the mother’s labor supply is less than 1, i.e., it rules out solutions in which the mother spends her entire time endowment working in the labor market. The lower bound guarantees that, in the absence of a positive child support payment from the noncustodial father, the mother would always find it optimal to participate in the labor market by choosing labor supply greater than 0. The latter assumption not only enables us to simplify the analysis but is also justified by the goal of this work, which is focused on providing useful insights into the effects of tax-benefit policy changes on divorced parents’ labor supply and child support decisions. Footnote 13

4 The effect of tax-benefit policy reform on divorced parents’ behavior

Having described the framework in which the two-stage game between f and m takes place, we now characterize its subgame-perfect equilibrium using standard backwards induction arguments. We then consider how changing the institutional parameters (B and \(\mathbf{w}\)) affects the equilibrium choices and describe the underlying welfare effects.

4.1 Mother’s decisions

Fix an arbitrary child support payment \(s\in[0,\mathbf{y}]\) made by the father in stage 1. In stage 2, the custodial mother decides how to allocate her time between market work and childcare activities by choosing l, and then chooses how to allocate her after-tax income between private consumption, x m , and expenditures on the child, k. It is useful to decompose the second stage into a step where the mother first makes her time allocation decision and then decides over her income allocation.

Consider first the budget allocation decision. The mother’s after-tax income is \(B+\mathbf{w}l+s\). Let π x denote her income share in private consumption x m , and π k her income share in child goods k. Then, the mother’s income allocation problem is

subject to π x + π k = 1. Footnote 14 Cobb–Douglas preferences imply constant expenditure shares, which in equilibrium are

Consider now the time allocation decision. Under (5), the mother’s second stage time allocation problem is to solve

Since there may be a corner solution in which the mother decides not to participate in the labor market, define \(\tilde{s}\) to be the child support payment that implicitly solves the mother’s first-order condition when l = 0. This is given by

Note that under Assumption 1, \(\tilde{s}>0\). The mother’s time allocation decision in stage 2 is then described by the following:

Proposition 1

Suppose Assumption 1 holds. Given any arbitrary child support payment s ∈ [0, y] from the father, the mother’s optimal choice of l is:

-

(i)

l e = 0, if \(s\geqslant \tilde{s}\); or

-

(ii)

$$ l^e=\frac{(\alpha_m+\gamma_m){\mathbf{w}}-\beta_m\delta (B+s)}{{\mathbf{w}}\delta(\alpha_m+\beta_m+\gamma_m)} \equiv l^*(s), \;\hbox{if}\;s<\tilde{s}. $$(12)

Therefore mothers who receive a transfer above the threshold \(\tilde{s}\) choose to be out of the labor market, while those who receive a transfer below \(\tilde{s}\) choose to be in paid employment. Expression (12) reflects the trade-off between home-produced childcare quality and employment as a function of the father’s support payment s and the institutional parameters B and \(\mathbf{w}\). It can be easily verified that an increase in s reduces the mother’s labor supply. Intuitively, if the mother receives a relatively high child support transfer, she is willing to substitute work time in the market for childcare time at home, and this has a beneficial impact on childcare quality. An increase in \(\mathbf{w}\), instead, raises labor supply. The mother’s demand functions for private consumption and child good expenditures satisfy standard properties: that is, they are increasing in s, B, and \(\mathbf{w}\). Finally, child welfare—which positively depends on child good expenditures and maternal time—is strictly increasing in s and B. An increase in \(\mathbf{w}\), however, has an ambiguous effect on child welfare: while it increases child good expenditures, it also reduces the amount of time the child receives direct interaction with the mother.

4.2 Father’s decision

The father’s budget constraint is \(x_f=\mathbf{y}-s\). He is assumed to care not only about his own consumption but also about the welfare of his child. Footnote 15 Child welfare, in turn, depends on child good expenditures, \(k^e=\pi_k^e(B+\mathbf{w}l^e+s)\), and childcare quality, q e = 1 − δ l e, which are controlled by the custodial mother. Thus, the father’s first stage optimization problem is to solve

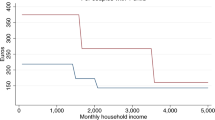

His decision is driven by the way in which child good expenditures and childcare quality vary with child support transfers. The following result, which is illustrated in Fig. 1, characterizes the unique subgame perfect equilibrium of our model.

Proposition 2

Suppose Assumption 1 holds. Define:

Let \(\overline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) solve \(s^*=\tilde{s}\); and let \(\underline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) solve s * = 0. Then, \(\overline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})>\underline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) for all \(\mathbf{w}\in(\mathbf{\underline{w}},\mathbf{\overline{w}})\), and:

-

(i)

if \(\mathbf{y} \in(\underline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w}), \overline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w}))\), the father’s optimal support payment is s e = s * , and the mother’s optimal labor supply is l e = l *(s *) (“interior equilibrium”).

-

(ii)

if \(\mathbf{y}\geqslant \overline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) , the father’s support payment is \(s^e=\max\{\overline{s},\tilde{s}\}\) , and the mother’s labor supply is l e = 0 (“no-employment equilibrium”).

-

(iii)

if \(\mathbf{y} \leqslant \underline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) , the father’s support payment is s e = 0, and the mother’s labor supply is l e = l *(0) (“no-support equilibrium”).

In either (i), (ii), or (iii), the mother spends fractions π e x = π * x and π e k = π * k of her equilibrium after-tax income on private consumption and child goods, respectively.

There are, therefore, three types of equilibria. Consider an arbitrary value of \(\mathbf{w}\) in the open interval \((\mathbf{\underline{w}},\mathbf{\overline{w}})\). If the father’s income is sufficiently high, \(\mathbf{y}\geqslant \overline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\), we have a no-employment equilibrium: here, the child support payment made by the father, \(s^e=\max\{\overline{s},\tilde{s}\}\), is high enough to allow the mother to choose full-time parenting, so that l e = 0 [case (ii)]. If the father’s income instead is at an intermediate level, \(\mathbf{y}\in(\underline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w}), \overline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\)), then we are at an interior equilibrium [case (i)]: the child support payment made by the father, s e = s *, is positive but not large enough to enable the mother to spend all of her time looking after the child, and so she decides to supply a positive amount of labor to the market, namely l e = l *(s *). Finally, if the father’s income is low, \(\mathbf{y} \leqslant \underline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\), we have a no-support equilibrium [case (iii)]: here, the father does not volunteer any child support payments, i.e., s e = 0, while the mother devotes a relatively large proportion of her time to market work, l e = l *(0). Footnote 16

The main aim of this study is to develop an understanding of the interplay between tax-benefit policy reform and the behavior of divorced parents in terms of child support payments, time allocated to work and parenting, and child good expenditures. Marginal changes in tax-benefit policies have no direct effect on mothers’ labor supply decisions in the no-employment equilibrium, and so we will not focus on it. In addition, since marginal policy changes have no impact on the behavior of divorced fathers in the no-support equilibrium, we will not focus on it either. Footnote 17 Therefore, we focus mainly on the interior equilibrium in which neither parent is bound by non-negativity constraints. The two most interesting features of this interior equilibrium are its efficiency properties and the comparative statics with respect to the tax-benefit parameters (B and \(\mathbf{w}\)), to which we now turn.

4.3 Efficiency properties of the equilibrium

A key aspect of our model is that child well-being is a public good from the point of view of both parents, although only the custodial parent decides on childcare quality and child good expenditures. In our setting, there is no self-enforcing mechanism that induces the custodian to internalize the impact of her choices on the noncustodian. In particular, noncooperative behavior implies that the ex-spouses cannot negotiate and then commit to binding and costlessly enforceable agreements. As a consequence, the two parents fail to achieve a Pareto efficient allocation of their resources. The following proposition describes the distortions that arise in this framework.

Proposition 3

In an interior equilibrium, where s e = s *, l e = l *(s *) and π e x = π * k , each of (i) a marginal increase in π k , (ii) a marginal reduction in l, and (iii) a marginal increase in s would lead to a Pareto improvement for the two parents.

The interior equilibrium suffers from three inefficiencies. On the custodial side, the amount spent on child goods is not efficient, since the mother does not internalize the effect of her income allocation on the father. This is a standard problem which has been discussed before (Weiss and Willis 1985; Flinn 2000). However, in addition to spending an inefficiently low amount on child goods, the mother also supplies an inefficiently high amount of labor time to the market, that is, she spends too much time at work and too little on childcare activities. On the noncustodial side, anticipating that the mother will spend too little on child goods and work too much in the labor market, the father offers inadequate child support payments. Essentially, the father cannot bargain with his former spouse over her time and income allocations; thus, through his child support transfer, he tries to influence the mother to spend more money on child goods and substitute hours of parenting for hours of paid work. But because the mother only spends a fraction of the transfer received from the father on child goods, and because she supplies more than the efficient amount of labor, the father does not fully capture the social marginal return from his child support payment. Therefore, his transfer is inefficiently low.

4.4 Equilibrium comparative statics

So far we have characterized parents’ decisions given the tax policy parameters, B and \(\mathbf{w}\). We now consider how changes in such parameters affect those choices and illustrate the corresponding welfare effects. As the choices in the interior equilibrium depend on B and \(\mathbf{w}\) [see expressions (12) and (14)], our notation will have to acknowledge this explicitly. The father’s equilibrium transfer then is denoted \(s^e=s^*(B, \mathbf{w})\), and the mother’s optimal labor supply is \(l^e=l^*(B,\mathbf{w},s^*(B,\mathbf{w}))\). We examine the effects of a policy reform that operates through two distinct channels. The first involves a more generous government transfer to the custodial parent (higher B); the second implies an increase in the custodian’s effective wage \(\mathbf{w}\), which can be achieved either through greater childcare subsidies (lower p) or through a reduction in the marginal rate of income tax (lower τ).

We begin with the effects on the father’s child support decision with the following:

Proposition 4

In the interior equilibrium, where \(l^e=l^*(B,\mathbf{w},s^*(B,\mathbf{w}))\) and \(s^e=s^*(B,\mathbf{w})\), the noncustodian’s child support payment is (i) strictly decreasing in B, and (ii) strictly decreasing in \(\mathbf{w}\).

This result suggests that greater B and \(\mathbf{w}\) induce the father to reduce his equilibrium child support payment \(s^*(B,\mathbf{w})\). Thus, policies that increase government transfers and/or the effective wage received by the custodial parent will crowd out child support transfers from the noncustodian. Greater government transfers paid to the mother (part (i) of Proposition 4) have the same positive effect on her decision environment as an increase in the support payment by the noncustodial father: that is, it induces the mother to spend more financial resources on child goods, and to substitute hours of childcare at home for hours of work in the market. But this, in turn, implies that the father can respond to the original increase in welfare payments by reducing his child support transfer without a decrease in child well-being.

Slightly more subtle are the issues related to the impact of an increase in the mother’s effective wage (part (ii) of Proposition 4). It is useful to separate this into two distinct effects. First, holding the mother’s labor supply constant, an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) raises her after-tax income, which translates into an increase in child good expenditures. Again, this in turn allows the father to reduce his transfers without jeopardizing child welfare. In fact, it is as if the father’s income increased, allowing him to expand his private consumption at the expense of child support payment. Second, an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) leads the mother to increase her labor supply. This will have two opposite effects. On the one hand, it induces the father to increase his child support payment in an attempt to offset the increase in mother’s labor supply. On the other hand, it permits the father to reduce his child support transfers because the increase in mother’s labor supply is accompanied by an increase in her income and thus in child good expenditures allowing the father to substitute his private consumption for child support. In our framework, the latter effect strictly dominates the former. Therefore, the net total effect of an increase in mother’s effective wage is to induce the father to increase his private consumption and, accordingly, reduce his child support payment.

This substitution from child support to private consumption on the noncustodial side can have repercussions on both child welfare and parents’ well-being. Before looking at this issue, we first ascertain the effects of the tax-benefit reform on the mother’s labor supply decision. For this, we have:

Proposition 5

In the interior equilibrium, where \(l^e=l^*(B,\mathbf{w},s^*(B,\mathbf{w}))\) and \(s^e=s^*(B,\mathbf{w})\), the custodian’s labor supply is (i) strictly decreasing in B, and (ii) strictly increasing in \(\mathbf{w}\).

In the interior equilibrium of our model, the mother’s labor supply choice is too high and Pareto inefficient from the standpoint of the two parents. Proposition 5 indicates that, ceteris paribus, an increase in the level of government transfers received by the mother will reduce her labor supply, mitigating the inefficiency of over-employment [part (i)]. There are two opposite effects at work here. On the one hand, we have a standard income effect of transfer receipt: an increase in B makes the mother richer, and this allows her to reduce her labor supply and spend more time at home with the child. On the other hand, we have an indirect effect: an increase in government transfers paid to the mother leads the father to reduce his child support payments, and this in turn increases the mother’s labor supply. The income effect is larger than the strategic effect in absolute value, and thus the mother’s labor supply is decreasing in B. An increase in the mother’s effective wage, in contrast, increases her labor supply, reinforcing the inefficiency due to over-employment (part (ii) of Proposition 5). This relationship, again, is driven by two effects which, in this case, work in the same direction. There is a direct substitution effect: an increase in the effective wage rate increases the mother’s labor supply since it pushes up the opportunity cost of staying at home and looking after the child. Footnote 18 Besides this direct effect, there is also a strategic “multiplier” effect. This arises because an increase in the mother’s effective wage induces the father to reduce child support payments, and this reduction further magnifies the proportion of time the mother chooses to spend in the labor market.

4.5 Welfare effects

We now consider the welfare effects generated by the type of policy reform analyzed above. We are interested not only in how the reform affects the equilibrium utility of mother and father, but also in its impact on equilibrium child welfare. The questions we address are: What welfare effects would arise from increasing the government transfers paid to the mother? And what are the welfare effects of an increase in the mother’s effective wage rate? The answer to the first question is encapsulated in

Proposition 6

In the interior equilibrium, an increase in B would (i) raise the utilities of custodial and noncustodial parents and (ii) increase child welfare.

This result is perhaps unsurprising. While an increase in government transfers paid to the mother reduces the child support payment from the father, it nevertheless allows the mother to reduce her labor supply and spend more financial resources on child goods, which unambiguously raises child welfare and increases both parents’ utilities.

The answer to the second question is more surprising. Letting \(\delta(a+b)/[(1-\delta)+\delta(a+b)]\equiv \overline{\gamma}\), this is given in

Proposition 7

In the interior equilibrium, if the parents’ preference parameters are such that \(\gamma_f \geqslant \overline{\gamma}\) and \(\gamma_m \geqslant \overline{\gamma}\), then an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) would (i) lower the utilities of custodial and noncustodial parents and (ii) reduce child welfare.

We ought to point out that the premises of this proposition (i.e., the assumption on the preference parameters γ f and γ m ) impose sufficient conditions. In fact, there are weaker sufficient conditions—which allow for \(\gamma_f<\overline{\gamma}\) and/or \(\gamma_m<\overline{\gamma}\)—under which this finding holds too (see Proposition 8 below). The result here implies that, if private consumption has a sufficiently large weight in parents’ utilities, then an increase in the effective wage of the mother (through either a greater childcare subsidy or a lower income tax rate) would unambiguously reduce child welfare and lower the utility of both parents. Our result offers a new insight: a tax-benefit policy that also subsidizes households’ childcare expenditures or lowers marginal income tax rates faced by low-income working single parents and their children could worsen their well-being.

To see this, notice that we can reformulate the father’s problem of Sect. 4.2 as a choice between private consumption and child welfare. As long as the mother supplies a positive fraction of her time in paid work, the father’s problem can be rewritten as:

where

Thus, the father’s decision boils down to choosing between child welfare and private consumption as if he had effective money income \(\mathbf{y}+\mathbf{w}/\delta + B\) and faced a non-linear price schedule for child welfare, \(\rho(\mathbf{w})\mu(C)\), which depends on the mother’s effective wage and the preference parameters of her utility function. Footnote 19 In his decision, the father takes into account the fact that his former spouse, without having to rely on his transfer, would guarantee a minimum level of child welfare \(\underline{C}(\mathbf{w})\), where Footnote 20

In this context, an increase in the mother’s effective wage rate entails three changes that are relevant to the father’s decision problem. First, it raises his money income \(\mathbf{y}+\mathbf{w}/\delta+ B\); second, it raises the implicit price for child welfare \(\rho(\mathbf{w})\); third, it lowers the minimum amount of child welfare \(\underline{C}(\mathbf{w})\) the father can obtain when he does not make any child support payment. As illustrated in Fig. 2, at an interior equilibrium these changes produce three effects on the father’s decision environment:

-

(a)

a money income effect (MIE): holding \(\rho(\mathbf{w})\) constant, an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) raises the father’s money income, giving him an incentive to increase his private consumption at the expense of child support transfers. Intuitively, if we hold the mother’s labor supply constant, an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) raises her after-tax income, and this increases child good expenditures and child welfare; this then yields an increase in the father’s effective money income, inducing the father to increase his private consumption and cut child support.

-

(b)

a real income effect (RIE): allowing now \(\rho(\mathbf{w})\) to adjust, an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) raises the implicit price of child welfare as it induces the mother to work more; this in turn reduces the father’s real income which leads to a reduction in his private consumption and to an increase in child support payments to the mother in the attempt to mitigate the increase in her labor supply.

-

(c)

a substitution effect (SE): an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) causes the implicit price of child welfare to go up, thereby increasing the relative attractiveness of private consumption; this induces the father to substitute private consumption for child welfare (i.e., reduce support payments to the mother); the utility of the father is unaffected but child welfare is reduced.

The figure also illustrates that the total effect of an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) is to increase the father’s private consumption (with the corresponding reduction in child support payments) and to lower child welfare. This last reduction is driven by the greater labor supply of the mother, which itself is the net result of the direct substitution effect (i.e., the opportunity cost of staying home goes up) and the strategic multiplier effect (i.e., the response to smaller child support from the father) described in the previous subsection.

Up until now we have considered the welfare effects of increasing the effective wage earned by the mother under the assumption that parents’ own-consumption utility weights are sufficiently high (\(\gamma_f\geqslant\overline{\gamma}\) and \(\gamma_m\geqslant\overline{\gamma}\)). These results may continue to hold even when parents’ own-consumption utility weights are lower (e.g., \(\gamma_f<\overline{\gamma}\) and/or \(\gamma_m<\overline{\gamma}\)). The set of parameter values in the \((\mathbf{y},\mathbf{w})\)-space for which this occurs is described in the following

Proposition 8

Let

If the model parameters are such that \(\mathbf{y}>\max \{\hat{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w}),\tilde{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\}\), then an increase in the effective wage \(\mathbf{w}\) would (i) lower the utility of custodial and noncustodial parents and (ii) reduce child well-being even if \(\gamma_f<\overline{\gamma}\) and/or \(\gamma_m<\overline{\gamma}\).

Figure 3 illustrates the effects of an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) on child and parental welfare in general terms. Panel (a) plots the father’s income against the mother’s effective wage. Footnote 21 Panel (b), instead, plots the own-consumption utility weight of the father against that of the mother. Proposition 7 shows that if parents’ preference parameters are such that \(\gamma_f\geqslant \overline{\gamma}\) and \(\gamma_m\geqslant \overline{\gamma}\) [region A in panel (b)], then an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) would reduce child welfare and lower the utility of both parents for all \((\mathbf{y},\mathbf{w})\)-combinations that give rise to an interior equilibrium [regions I, II, and III in panel (a)]. Footnote 22 Proposition 8 establishes that, even if \(\gamma_f<\overline{\gamma}\) and/or \(\gamma_m<\overline{\gamma}\) (regions B–E), an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) would continue to reduce child welfare and lower the utility of both parents as long as the father’s income and the mother’s wage are such that \(\mathbf{y}>\max\{\hat{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w}),\tilde{\mathbf{y}} (\mathbf{w})\}\) [region I in panel (a)]. Therefore, even if private consumption carries relatively little weight in parents’ preferences, as long as the income of the noncustodial parent is sufficiently high, an increase in the mother’s effective wage will have negative welfare consequences for all parties involved: the child, the custodial mother, and the noncustodial father.

It is important to underline that an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) will not always reduce the welfare of all parties. Our next step is to discuss configurations of parameter values for which one of the parties would be made better off. If parents’ preference parameters are such that \(\gamma_f\geqslant\overline{\gamma}\) and \(\gamma_m<\overline{\gamma}\) (as in region B), an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) would reduce child welfare and lower the mother’s utility; but the father will experience an increase in utility provided the model parameters are such that \(\mathbf{y}< \hat{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) [as in regions II and III, panel (a)]. Thus, if private consumption carries less weight in the mother’s utility function than in the father’s, and the father’s income is sufficiently low, an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) would benefit the mother while hurting both the father and the child. If the preference parameters instead are such that \(\gamma_f< \overline{\gamma}\) and \(\gamma_m\geqslant\overline{\gamma}\) (as in region C), an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) would reduce both child well-being and the father’s utility; but the mother will experience an increase in utility provided that \(\mathbf{y}< \tilde{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) (regions II and III). Perhaps surprisingly, there is also a case in which an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) lifts the utility levels of both parents, while reducing child welfare. This occurs if either \(\pi(\gamma_m)/[1 + \pi(\gamma_m)]<\gamma_f<\overline{\gamma}\) and \(\gamma_m<\overline{\gamma}\) (region D), Footnote 23 and \(\mathbf{y}<\min\{\hat{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w}),\tilde{\mathbf{y}} (\mathbf{w})\}\) [regions II and III, panel (a)]; or if \(\gamma_f<\overline{\gamma}\) and \(\gamma_m<\overline{\gamma}\) (regions D and E) and \(\breve{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})<\mathbf{y} <\min\{\hat{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w}),\tilde{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\}\) [region II, panel (a)].

The final result of this section completes the picture by describing the set of parameter values for which all parties involved would benefit from an increase in the effective wage of the custodial parent. This is given in

Proposition 9

Let

If the model parameters are such that \(\mathbf{y}<\breve{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) and γ f < π(γ m )/[1 + π(γ m )], then an increase in the effective wage \(\mathbf{w}\) would (i) raise the utility of both custodial and noncustodial parents and (ii) increase child well-being.

Two conditions must be satisfied if an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) is to have a positive effect on child and parental well-being. Not only is it necessary that private consumption carries relatively little weight in both parents’ preferences (region E), but also the noncustodial father must have a sufficiently low income (region III). Thus, policies that increase the effective wage of custodians are predicted to have positive welfare effects only for low-income divorced parents who value their private consumption relatively little viz-à-viz child well-being.

In sum, we have presented a comprehensive analysis of the effects of tax-benefit reform on the welfare of divorced parents and their children. Our results suggest that programs that increase the effective wage of custodial parents, either through lower marginal income tax rates or (as generally promoted with in-work benefit programs) through higher childcare subsidies, may have unexpected, possibly undesirable, welfare effects amongst divorced families. When parents’ own-consumption utility weights are sufficiently high, such reforms may yield a decline in child and parental welfare. This result continues to hold even when private consumption carries little weight in parental preferences as long as the noncustodian enjoys a relatively high income. Only when the noncustodial parent has a low income will we see positive welfare effects, provided that parental preferences for own consumption are sufficiently weak.

Remarks

We would like to draw attention to three points about the results stated above. First, one important assumption made in the model is that purchased “outside care” is not a perfect substitute for the mother’s time in the production of child quality (ψ < 1). Hence it is reasonable to ask: What would happen if a government not only provided child care subsidies, but also invested in high-quality child care? In this regard, our model predicts that an increase in the quality of non-maternal child care (i.e., a higher ψ) reduces the adverse effects that the provision of child care subsidies may have on children and their parents. Moreover, once the quality of outside care exceeds that of maternal care (i.e., as \(\psi\geqslant1\)), the provision of child care subsidies unambiguously raises the welfare of children and their parents and hence is no longer associated with adverse effects. From a policy perspective, these observations suggest that policies aimed at increasing the effective wage of lone parents should be accompanied by efforts to improve the quality of non-maternal child care.

Second, our policy analysis ignores its general equilibrium implications. In particular, it does not consider the effects of a reform’s funding on the welfare of divorced parents and their children. Thus, instead of taking the governments tax program as given, suppose that the reforms considered here are funded by a lump-sum tax levied on the father. Consider first an increase in government transfers (B), and assume that the lump-sum tax levied on the father exactly equals the increase in transfers. In this case, the increase in B would no longer have positive effects on parents and their children (see Proposition 6), but would leave parental and child welfare completely unaffected. The intuition is that an “income pooling property” applies to the interior equilibrium of our model. The implication of income pooling is that only total household unearned income matters for the mother’s labor supply choice and the parents’ indirect utilities. Thus, a reform that increases government transfers to the mother but, at the same time, imposes a lump-sum tax on the father that equals the increase in government transfers leaves the indirect utilities of the parents unaffected. Footnote 24 A different conclusion applies to a reform that increases the effective wage of the mother. If such a reform is financed by lump-sum tax on the father, then the adverse effects described above (see Proposition 7) will be reinforced since the lump-sum tax on the father will induce him to further reduce his child support payment to the mother.

Finally, our discussion has focused on the negative welfare effects generated by policy reforms in the interior equilibrium of our model. By contrast, in the no-support equilibrium (see Proposition 2, Fig. 1), such reforms are less likely to yield declines in child and parental well-being. Intuitively, this is because an increase in the effective wage of the custodial parent would no longer lead to a strategic multiplier effect, i.e., it would no longer induce the noncustodial parent to further reduce child support payments. As a consequence, the aggravation of the inefficiency due to over-employment is less severe in the no-support equilibrium than in the interior equilibrium. Formally, in the no-support equilibrium an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) would unambiguously raise the utility of the custodial mother. Moreover, if the model parameters are such that \(\gamma_m<\overline{\gamma}\) (i.e., the mother’s own-consumption utility weight is sufficiently low) and \(\mathbf{w}>\tilde{\mathbf{w}}\) (i.e., the mother’s wage is sufficiently high), Footnote 25 then an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) would also raise the utility of the noncustodial father and increase child well-being. Conversely, if \(\gamma_m>\overline{\gamma}\), or if \(\gamma_m<\overline{\gamma}\) and \(\mathbf{w}<\tilde{\mathbf{w}}\), then an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) would lower the utility of the noncustodial father and reduce child welfare.

5 An extension: child support orders and the issue of compliance

In the model of Sect. 4, the government exogenously sets B and τ and may choose to subsidize the purchase of formal childcare by varying its unit price p. But it does not influence child support transfers through, for instance, a system of court-mandated awards. To examine whether or not our earlier results change in an environment in which divorced parents face child support orders, we modify the noncustodial father’s preferences in the way proposed by Del Boca and Flinn (1995) as follows:

where s o > 0 is a court-mandated child support order and I[·] is an indicator function. Footnote 26 The father pays a fixed cost, θ, if he does not fully comply with the court order. But if his child support payment meets or exceeds the order, then the cost is avoided. Recall that the father’s voluntary child support payment is given by

where (\(s^*,\overline{s}, \tilde{s}\)) and \((\underline{\mathbf{y}} (\mathbf{w}), \overline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\)) are defined in (11) and Proposition 2.

Consider the father’s decision of whether or not to comply with the court order as a function of \(\mathbf{y}\) and θ, and assume \(s^o<\tilde{s}\). This restriction ensures that the child support order—if fully complied with—is such that it is optimal for the mother to supply a positive fraction of her time to the labor market. With these ingredients, we can identify five different types of compliance behavior. Figure 4 describes these cases as a function of \(\mathbf{y}\) and θ.

In the previous section we have established that when the father’s income \(\mathbf{y}\) exceeds the threshold \(\underline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) the father will voluntarily make a positive child support payment to his former spouse. If, additionally, his voluntary payment s * is greater or equal to s o, then the court order does not bind his transfer behavior. This is the case of overcompliance. Let \(\mathbf{y}^+(\mathbf{w})\) be the value of the father’s income for which the voluntary payment s * is exactly equal to the court order s o. Footnote 27 Clearly, for the father to choose to be overcompliant, his income must be more than \(\mathbf{y}^+(\mathbf{w})\).

Consider now the case in which the father’s income is less than \(\mathbf{y}^+(\mathbf{w})\) but more than \(\underline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\). In this case, the father will again make a voluntary transfer to the mother, although s * will not be above the court order s o. The father then has two options: he can either choose undercompliance by making his optimal voluntary transfer s * and incurring the cost θ; or choose exact compliance by paying the order s o and avoiding the cost θ. Let \(\lambda_1(\theta,\mathbf{w})\) be the value of \(\mathbf{y}\) which equates the utility value of undercompliance to the utility value of exact compliance. Footnote 28 It then follows that a noncustodian with income between \(\underline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) and \(\mathbf{y}^+(\mathbf{w})\) will choose undercompliance if \(\mathbf{y}<\lambda_1(\theta,\mathbf{w})\), and exact compliance if \(\mathbf{y}>\lambda_1(\theta,\mathbf{w})\).

Finally, consider the case in which the father, in absence of court orders, would voluntarily make no child support payment to the mother. This case occurs when the father’s income is less than \(\underline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\). As before, the father faces two options: he can either make no transfer and bear the cost θ, or choose exact compliance at no cost. If \(\lambda_2(\theta,\mathbf{w})\) denotes the value of \(\mathbf{y}\) which equates the utility value of no child support payment with that of exact compliance, Footnote 29 then a father who makes no transfer will have \(\mathbf{y}<\lambda_2(\theta,\mathbf{w})\), while a father with \(\mathbf{y}>\lambda_2(\theta,\mathbf{w})\) will exactly comply with the court order.

We now use this extended model to examine how in-work benefit reform affects the compliance behavior of noncustodial parents. For the sake of brevity, we focus on the effects of a singly policy—an increase in the effective wage of the custodial mother. All our results on compliance behavior, however, also apply to a policy that offers greater government transfers B to the custodian. Under the assumption that \(\mathbf{y}\) and θ are independently distributed random variables, we have the following

Proposition 10

A tax-benefit policy reform that aims at increasing the effective wage of custodial mothers would reduce the set of fathers who choose either to overcomply or to exactly comply with child support orders. The set of fathers who choose either to undercomply or to make no child support payment would increase accordingly.

The intuition for this result is straightforward. First, an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) reduces the voluntary child support payment that fathers with \(\mathbf{y}<\underline{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) would optimally make. This essentially pushes up the income threshold \(\mathbf{y}^+(\mathbf{w})\) above which fathers choose to overcomply with respect to court orders. Hence, the incidence of overcompliance will decline. Second, for any given value of θ, an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) reduces the utility value of exact compliance relative to that of undercompliance. This is because undercompliance allows fathers to reduce their child support payments optimally in response to an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\), while exact compliance does not allow for such utility-maximizing adjustments. Thus, the income threshold \(\lambda_1(\theta,\mathbf{w})\) shifts outwards. A similar argument establishes that an increase in \(\mathbf{w}\) drives a wedge between the utility value of no child support payment and that of exact compliance, and so \(\lambda_2(\theta,\mathbf{w})\) shifts outwards too. Hence, the incidence of exact compliance will go down.

In general, tax-benefit policies that alter the economic circumstances of divorced parents, especially those programs that try to raise custodial parents’ effective wages, may crowd out the voluntary child support transfers from noncustodial parents, even in presence of court-mandated child support awards. Adding child support orders to the institutional environment, therefore, does not qualitatively change our earlier results, implying that the potential for tax-benefit reforms to have unintended (and presumably undesirable) consequences remains.

6 Conclusions

Our theoretical analysis, which extends the seminal work by Weiss and Willis (1985), suggests that welfare reforms, and especially recent work-conditioned transfer programs, may have unintended consequences among divorced parents and their children. Like earlier models of child support payments (Weiss and Willis 1985; Del Boca and Flinn 1995; Flinn 2000), our model also produces inefficient levels of child support transfers and expenditures on children. Additionally, it emphasizes inefficiencies related to the childcare decisions of noncustodial parents. The introduction of generous in-work benefits, which substantially increase the effective wage of single parents (through either lower marginal income tax rates, or higher childcare subsidies, or both), may aggravate the inefficiency on the custodial side by creating more incentives to work and thus spending less time with children. This policy-induced inefficiency is magnified by an indirect effect that operates through further reductions of the already low child support payments made by noncustodial parents.

What are the implications of our results for future in-work benefit reforms? There is consistent and robust evidence that work-conditioned transfer programs around the world have been quite successful in providing cash assistance to low-income single-parent families without creating adverse incentives for participation in the labor market (e.g., Hotz and Scholz 2003; Blundell and Hoynes 2004; Eissa and Hoynes 2004; Morris et al. 2005; Grogger et al. 2002; Francesconi and van der Klaauw 2007; Meyer 2007; Blundell et al. 2008). In fact most studies find such programs to produce positive and meaningful increases in labor supply and total income. However, these positive outcomes notwithstanding, it is unclear whether such programs actually produce significant improvements in the welfare of divorced parents and their children. As indicated by our theoretical findings, in-work benefit reforms may in fact have negative welfare consequences, including that of children. Therefore, in designing welfare-to-work programs special care should be taken to avoid such effects, for example by including provisions for improving the availability of higher quality childcare services and through the introduction of tax incentives or changes in child support orders or in their enforcement to help avoid reductions in the private child support transfers made by fathers. That is, in-work benefit reforms ought to be part of a broader mix of family policies.

There are several extensions and applications we would like to pursue in future research. First, it would be interesting to analyze an extension of the model in which non-custodial parents can also decide how much time and money to spend on children. In this case, the model would be more like a voluntary contribution to a public good game. Second, the possibility that divorced parents change their child transfer and expenditure decisions over time (also in response to changes in welfare programs) suggests that a dynamic model can provide a more accurate description of ex-spouses’ interactions. Third, some of our rationalizations rest on noncustodial fathers’ transfer behavior. Although there are several studies that estimate child support transfer decisions of nonresident fathers (e.g., Weiss and Willis 1993; Del Boca and Flinn 1995; Flinn 2000; Walker and Zhu 2006; Ermisch and Pronzato 2008), relatively little is known about such decisions in response to welfare reforms. This seems to be a promising area for future empirical work. Fourth, formulating an estimable model that could be taken to longitudinal data on parents and children followed before and after divorce would enormously enhance our insights into the role of parents in shaping child outcomes and our understanding of how this relationship can be influenced by welfare reform.

Notes

As will become apparent below, by “suboptimally low” we mean that an increase in the father’s equilibrium child support payment would constitute a Pareto improvement for the two parents.

A recent strand of analysis argues that inefficient intrahousehold allocations are plausible even in marriage as long as current decisions affect future bargaining power and spouses cannot make binding commitments over allocations within marriage. See, among others, Lundberg and Pollak (2003) and Konrad and Lommerud (1995), and our brief discussion below.

Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of the High School of 1972, Weiss and Willis (1993) analyze the effects of spouses’ incomes on transfers among divorced couples. They find that divorce transfers tend to increase with the noncustodial parent’s income and to decline with the custodial parent’s income, while child expenditures in the divorce state are estimated to be half of those that would occur during marriage. This last finding is consistent with the estimates reported in Jarvis and Jenkins (1999) for Britain and Page and Stevens (2004) for the United States. In a recent empirical study, Gunter (2013) examines whether states’ elimination of child support disregards for welfare payments after welfare reform caused non-custodial parents to increase in-kind support.

Our specific functional form assumptions allow us to reach closed-form solutions which keep the analysis transparent and tractable. However, allowing for more general utility and production functions would not change the main gist of our results. Moreover, allowing additionally for pure leisure in the mother’s utility function would also not change our main insights.

In the UK, family courts decide to leave children with their mothers in the vast majority of divorce cases. Indeed, data from a number of different sources (e.g., the Office for National Statistics) from the late 1990s and early 2000s suggest that 70 % of single parents in Britain are mothers living with their children. Only 7 % of single parents are fathers living with their children, while 21 % of divorced parents share custody for their children. In the US, joint custody has been awarded in 25 % of all cases between 1989 and 1995, with the mother assigned sole custody in the majority of the remaining 75 % of cases (Halla 2013).

Our basic setup assumes that child support transfers are voluntary. This is a reasonable assumption when monitoring child support arrangements is difficult or when their enforcement is weak. For example, in Britain the majority of child support payments are made informally and, in large part, on a voluntary basis (Blackwell and Dawe 2003). In an extension, we will also explore a model where noncustodial parents have to decide whether or not to comply with court-mandated child support orders.

Del Boca and Flinn (1995) also consider an environment in which decision making proceeds sequentially. This assumption simplifies our analysis. Notice, however, that all our main insights would also hold in the corresponding simultaneous-move game.

There is therefore an implicit equivalence between maternal hours of work and paid childcare. This equivalence is imposed to ease the exposition of some results, without affecting our main insights. Indeed, all results are robust to using a linear relationship between hours of paid work and childcare, as supported by the empirical evidence presented in Duncan et al. (1995).

Suárez (2013) provides an empirical analysis of working mothers’ decisions on childcare.

Ermisch (2003) goes one step further and assumes that purchased child-care is not only an imperfect substitute for maternal time, but also that additional purchased time becomes a poorer substitute for maternal care. In particular, he proposes a child quality production function given by

$$ t_{mc}=H+h(M) \;\hbox{with}\; 0<h'(M)<1, h''(M)<0, h(0)=0, $$where H is the amount of the mother’s time devoted to children, M is the amount of time purchased in the market, and h(M) is a function converting purchased time inputs into units equivalent to the mother’s time. As will become apparent below, adopting this more general specification would only reinforce our results.

Empirical research on the effect of nonmaternal care on child developmental and behavioral outcomes tends to document a strong negative relationship (e.g., Belsky 2001; NICHD-ECCRN 2003; Baker et al. 2008, and references therein). Negative formal childcare effects also emerge in the case of later child outcomes (e.g., Bernal and Keane 2010; Liu et al. 2010). Our assumption of imperfect substitutability between maternal care and outside care is consistent with this evidence.

These are \(\underline{\mathbf{w}}=\delta \beta_m B/(\alpha_m + \gamma_m)\) and \(\overline{\mathbf{w}}=\delta \beta_m B / [(1-\delta)(\alpha_m+\gamma_m)-\delta \beta_m]\), respectively.

For women with wage rates below \(\underline{\mathbf{w}}\), we are back to a setting similar to that in Weiss and Willis (1985) and Del Boca and Flinn (1995) which treats the custodian’s labor supply decision and income as exogenous. In such an environment, the allocation of resources within non-intact families would be independent of policies aimed at increasing the (non-working) custodian’s effective wage.

With Cobb–Douglas preferences, this problem is equivalent to choosing (x m , k) to maximize \(U_m[x_m,F(k,q)]=x_m^{\gamma_m}k^{\alpha_m} q^{\beta_m}\) subject to the budget constraint \(x_m+k=B+\mathbf{w}l+s\).

Grogger and Karoly (2009) formulate an alternative model in which divorced fathers do not receive utility from child well-being.

From (12), it is easy to check that, in the no-support equilibrium, the mother works more than in the interior equilibrium, i.e., l *(0) ≥ l *(s *).

We will, however, in the next section briefly comment on some comparative static results that would be obtained in the no-support equilibrium.

An increase in the effective wage also makes the mother richer, and this reduces her labor supply. In our setting, however, this income effect is strictly dominated by the substitution effect described in the text. This is simply the result of our choice of the Cobb–Douglas functional form for parental preferences. However, that the substitution effects dominate labor supply decisions holds more generally for any forward-sloping labor supply function.

If child welfare is evaluated at π e k = π e x and l e = l *(s), we obtain

$$ C=\left[\frac{\pi^*_k(\alpha_m+\gamma_m)}{\delta}\right]^a \left(\frac{\beta_m}{{\mathbf{w}}}\right)^b\left(\frac{{\mathbf{w}}+\delta (B+s)}{\alpha_m+\beta_m+\gamma_m}\right)^{a+b}. $$By inverting the above expression we obtain \(s=\rho(\mathbf{w})\mu(C)-\mathbf{w}/\delta-B\). It follows that the father’s private consumption can be written as \(x_f=\mathbf{y} -s = (\mathbf{y} + \mathbf{w}/\delta + B) - \rho(\mathbf{w})\mu(C)\).

For ease of exposition, the figure assumes γ f = γ m . This assumption implies that \(\hat{\mathbf{y}} (\mathbf{w}) = \tilde{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\). Notice, however, that \(\hat{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) will be larger (respectively, smaller) than \(\tilde{\mathbf{y}}(\mathbf{w})\) if γ f > γ m (respectively, if γ f < γ m ).

As shown in Proposition 2 values outside of these regions do not correspond to an interior equilibrium.

The function π(γ m ) is explicitly defined in Proposition 9.

Note that this conclusion only applies to an interior equilibrium in which (a) the mother works positive hours and (b) the father makes a voluntary transfer to the mother. Thus, it ignores the possibilities of the mother not working and of a zero voluntary transfer from the father to the mother (see Proposition 2).

Here, \(\tilde{\mathbf{w}}=b\delta B/a\). It is readily checked that \(\tilde{\mathbf{w}}\in(\underline{\mathbf{w}},\overline{\mathbf{w}})\) for all \(\gamma_m<\overline{\gamma}\).

For simplicity, we assume that the court-mandated order s o is independent of the father’s income. However, our analysis would also go through under the alternative assumption that the father has to pay a fixed percentage of his income to the mother.

Equating s * [see Eq. (14)] to s o and solving for \(\mathbf{y}\), it follows that

$$ {\mathbf{y}}^+({\mathbf{w}})=\frac{\gamma_f({\mathbf{w}}+\delta B)+ s^o\delta(\alpha_f+\beta_f+\gamma_f)}{\delta(\alpha_f+\beta_f)}. $$Formally, \(\lambda_1(\theta,\mathbf{w})\) implicitly solves

$$ ({\mathbf{y}}-s^*)^{\gamma_f}[\pi^e_k(B+{\mathbf{w}}l^*(s^*) +s^*)]^{\alpha_f}[1-\delta l^*(s^*)]^{\beta_f}-\theta= ({\mathbf{y}}-s^o)^{\gamma_f}[\pi^e_k(B+{\mathbf{w}}l^*(s^o) +s^o)]^{\alpha_f}[1-\delta l^*(s^o)]^{\beta_f}. $$The left-hand side of this expression is the utility value of undercompliance, while the right-hand side represents the utility value of exact compliance. Note that l *(s) and s *, which are respectively defined in (12) and (14), are functions of \(\mathbf{w}\).

Clearly, \(\lambda_2(\theta,\mathbf{w})\) solves the same expression as \(\lambda_1(\theta,\mathbf{w})\) earlier, but with the voluntary transfer s * replaced by 0.

References

Baker, M., Gruber, J., & Milligan, K. (2008). Universal child care, maternal labor supply, and family well-being. Journal of Political Economy, 116(4), 709–745.

Belsky, J. (2001). Developmental risks (still) associated with early child care. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(7), 845–859.

Bernal, R., & Keane, M. P. (2010). Quasi-structural estimation of a model of child care choices and child cognitive ability production. Journal of Econometrics, 156(1), 164–189.

Bitler, M. P., Gelbach, J. B., Hoynes, H. W., & Zavodny, M. (2002). The Impact of Welfare Reform on Marriage and Divorce. Demography, 41(2), 216–236.

Bitler, M. P., Gelbach, J. B., & Hoynes, H. W. (2005). Welfare reform and health. Journal of Human Resources, 40(2), 309–334.

Blackwell, A., & Dawe, F. (2003). Non-resident parental contact. London: Office for National Statistics, Social and Vital Statistics Division.

Blundell, R., Brewer, M., & Francesconi, M. (2008). Job changes and hours changes: Understanding the path of labor supply adjustment. Journal of Labor Economics, 26(3), 421–453.

Blundell, R., & Hoynes, H. (2004). Has ‘in-work’ benefit reform helped the labour market?. In: R. Blundell, D. Card & R. B. Freemand (Eds.), Seeking a premier economy: The economic effects of British economic reforms, 1980–2000 (pp. 411–459). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brewer, M., Francesconi, M., Gregg, P., & Grogger, J. (2009). Feature: In-work benefit reform in a cross-national perspective. Economic Journal, 119, F1–F14.

Del Boca, D., & Flinn, C. J. (1995). Rationalizing child-support decisions. American Economic Review, 85(5), 1241–1262.

Duncan, A., Giles, C., & Webb, S. (1995). The impact of subsidising childcare. EOC research report no. 13. Manchester: Equal Opportunities Commission.

Eissa, N., & Hoynes, H. (2004). Taxes and the labor market participation of married couples: The earned income tax credit. Journal of Public Economics, 88(9–10), 1931–1958.

Ermisch, J. F. (2003). An economic analysis of the family. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ermisch, J. F., & Pronzato, C. (2008). Intra-household allocation of resources: Inferences from non-resident fathers’ child support payments. Economic Journal, 118, 347–362.

Flinn, C. J. (2000). Modes of interaction between divorced parents. International Economic Review, 41(3), 545–578.

Francesconi, M., Rainer, H., & van der Klaauw, W. (2009). The effects of in-work benefit reform in Britain on couples: Theory and evidence. Economic Journal, 119, F66–F100.

Francesconi, M., Rainer, H., & van der Klaauw, W. (2008). Unintended consequences of welfare reform: The case of divorce parents. IZA discussion paper no. 3891, Bonn.

Francesconi, M., & van der Klaauw, W. (2007). The socioeconomic consequences of “in-work” benefit reform for British lone mothers. Journal of Human Resources, 42(1), 1–31.

Gennetian, L., Duncan, G., Knox, V., Vargas, W., Clark-Kauffman, E., & London, A. (2002). How welfare and work policies for parents affect adolescent: A synthesis of research. New York: Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation.

Gennetian, L. A., Miller, C., & Smith, J. (2005). Turning welfare into a work support: Six year impacts on parents and children from the Minnesota Family Investment Program. New York: Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation.

Gregg, P., Harkness, S., & Smith, S. (2009). Welfare reform and lone parenting in the UK. Economic Journal, 119, F38–F65.

Grogger, J., Karoly, & L. A. (2009). The effects of work-conditioned transfers on marriage and child well-being: A review. Economic Journal, 119, F15–F37.

Grogger, J., Karoly, L. A., Klerman, & J. A. (2002). Consequences of welfare reform: A research synthesis. Doc. DRU-2676-DHHS by RAND for Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Santa Monica, CA.

Gunter, S. P. (2013). Effects of child support pass-through and disregard policies on in-kind child support. Review of Economics of the Household, 11(2), 193–209.

Halla, M. (2013). The effect of joint custody on family outcomes. Journal of the European Economics Association, 11(2), 278–315.

Herbst, C. M., & Tekin, E. (2008). Child care subsidies and child development. IZA discussion paper no. 3836.

Hotz, V. J., & Scholz, J. K. (2003). The earned income tax credit. In: R. A. Moffitt (Ed.). Means-tested transfer programs in the United States (pp. 141–197). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jarvis, S., & Jenkins, S. P. (1999). Marital splits and income changes: Evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. Population Studies, 53(2), 237–254.

Konrad, K. A., & Lommerud, K. E. (1995). Family policy with non-cooperative families. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 97(4), 581–601.

Liu, H., Mroz, T., & van der Klaauw, W. (2010). Maternal employment and child development. Journal of Econometrics, 156(1), 212–228.

Lundberg, S. J., & Pollak, R. A. (2003) Efficiency in marriage. Review of Economics of the Household, 1(3), 153–167.

Meyer, B. D. (2007). The U.S. earned income tax credit, its effects, and possible reforms. Harris School working paper series no. 07.20, University of Chicago.

Morris, P. A., Gennetian, L. A., & Duncan, G. J. (2005). Effects of welfare and employment policies on young children: New findings on policy experiments conducted in the early 1990s. Society for Research in Child Development Social Policy Report, vol. 19, no. 2.

NICHD-ECCRN (National Institute of Child Health and Development—Early Childcare Research Network). (2003). Does the amount of time spent in childcare predict socioemotional adjustment during the transition to kindergarten?. Child Development, 74(4), 976–1005.

Page, M. E., & Stevens, A. H. (2004). The economic consequences of absent parents. Journal of Human Resources, 39(1), 80–107.

Suárez, M. J. (2013). Working mothers’ decisions on childcare: The case of Spain. Review of Economics of the Household, 11(4), 545–561.

Walker, I., & Zhu, Y. (2006). Child support and partnership dissolution. Economic Journal, 116(510), C93–C109.

Weiss, Y., & Willis, R. J. (1985). Children as collective goods and divorce settlements. Journal of Labor Economics, 3(3), 268–292.

Weiss, Y., & Willis, R. J. (1993). Transfers among divorced couples: Evidence and interpretation. Journal of Labor Economics, 11(4), 629–679.

Acknowledgments

The paper benefited from comments from Richard Blundell, Mike Brewer, Jeff Grogger, Hilary Hoynes, and seminar participants at Bergen, Bocconi, Boğaziçi, Essex, IFS, Linz, St Andrews and Stirling. We would also like to thank three anonymous referees and the Editor, Sonia Oreffice, for very helpful suggestions. The views and opinions offered in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System as a whole.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Francesconi, M., Rainer, H. & van der Klaauw, W. Unintended consequences of welfare reform for children with single parents: a theoretical analysis. Rev Econ Household 13, 709–733 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9226-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9226-5