Abstract

Using Japanese panel data, we analyze precautionary savings due to staying single in the presence of income uncertainty. Our panel analysis finds that compared with young women who are likely to get married within 3 years, those who are not plan to have 44 percent more savings for precautionary purposes, and 108 percent more for retirement. These results suggest that in facing higher risk of income fluctuation due to choosing to marry late or remain unmarried, young women intend to have more wealth to mitigate the income risk inherent in single life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In many developed countries, women are marrying later in life or do not marry at all. In Japan, this trend is noticeable: according to Japan’s Vital Statistics the average age at first marriage for women rose from 24.4 in 1960 to 28.8 in 2010. Only 20.6 % of women aged 25–29 remained unmarried in 1960; this figure rose to 59.9 % in 2010 according to the Japanese Population Census. In addition, the percentage of women who had never married by the age of 50 was 1.9 % in 1960 and rose to 10.6 % in 2010. From such trends we might imagine that many of the current generation of young women will have even fewer prospects of getting married in their lifetime.

In this paper, we focus on the risk-sharing motive of marriage.Footnote 1 If a member of a married couple faces a loss of earning capacity in the future due to unemployment, illness, or living longer than expected, the other spouse will supplement the income loss and cover the costs of the longer lifespan. Assuming a husband is the main breadwinner, when an exogenous shock occurs and reduces his income, it is optimal for a couple to compensate for that income reduction so they can maintain their consumption levels or leisure time. Likewise, the risk of living longer than average can be pooled within a marriage. For example, when a wife lives longer than average and her husband dies before her, her consumption following her husband’s death can be financed by the money left by her husband. Another way to soften the shock is to increase labor supply. That a wife’s additional labor supply is often induced by a husband’s income shock has been called the “added worker effect” (Mincer 1962). In Japan Kohara (2009) found that wives’ labor supply increased when their husbands suffered from involuntary job loss in the 1990s, a time of skyrocketing unemployment.

When women get married later in life or do not get married at all they cannot rely upon such risk sharing; this means that young, single women face higher uncertainty regarding future income. Thus, the higher risk due to late or no marriage encourages them to save more than they would if they were married. Such additional wealth that results from future uncertainty is called “precautionary savings.” Whether or not individuals increase their precautionary savings when they are worried about future labor income has been examined previously, using data pertaining to the United States and Europe (see Carroll and Samwick (1998), Dardanoni (1991), Dynan (1993), Kazarosian (1997), and Lusardi (1998)). Moreover, analyses of Japanese households have been undertaken by Zhou (2003), Murata (2003), Bessho and Tobita (2008), and Horioka et al. (2000). Bishop (2005), using the same dataset we use in this paper, examined precautionary saving motives among Japanese households by measuring the effect of income volatility on household assets. However, although many studies on precautionary savings relate to unemployment and labor income risk, few have focused on the risk due to family formation and dissolution. Chami and Hess (2005) develop a model in which a state’s representative individual chooses to marry in order to hedge against income risk and empirically obtain supportive evidence using cross-sectional data for the 50 US states. The study most closely related to our research is that of Pericoli and Ventura (2011). Using data from the Italian Survey on Households Income and Wealth, they show that an increase in the objective probability of family dissolution has a negative impact on non-durable consumption and a positive impact on household precautionary saving.Footnote 2

In this paper, we focus on precautionary savings due to staying single in the presence of income uncertainty. That is, single women who expect to be married later in life or not to be married at all face higher risk of income fluctuation, which encourages them to save more for precautionary purposes. Then, we examine the testable prediction that single women who have lower expectations of getting married in the future have more precautionary savings than those who have higher expectations. This is tested using Japanese micro-level data from the Japanese Panel Survey of Consumers (JPSC) of the Institute for Research on Household Economics.

The contribution of this paper is that we undertake an original exploration of precautionary savings highlighting young, single women’s expectations of getting married in the future. With the noticeable prevalence of remaining unmarried, single women’s life in old age is a primary concern for the women themselves and for policymakers. Many women work as non-regular employees and their length of employment is shorter. Thus, their benefit level for the public pension is low, which leads to severe financial conditions at their later stage. Therefore, it is important to examine how much single women prepare for their future life. Furthermore, we obtain the magnitudes of the impacts of young women’s single status on their precautionary savings goal. That is, our cross-sectional analysis finds that a one percentage point decrease in the predicted probability of marrying within 3 years increases the wealth target for general peace of mind or for no particular purpose by 1.64 percent. Then, our panel analysis finds that, compared with young women who are likely to get married within 3 years, those who are not plan to have 43.5 percent more savings for precautionary purposes and 108.2 percent more for retirement.

Section 2 presents our testable predictions and the estimation model. Section 3 introduces the data. Section 4 presents our estimation methods. Section 5 presents sample selection and descriptive statistics. Section 6 presents the estimation results. Finally, in Sect. 7, we discuss our results and conclude the paper.

2 The model

2.1 Theoretical consideration

Nordblom (2004) provided a theoretical investigation of the relationship between precautionary savings and the marital status of women. She considered a two-period model, in which a single woman receives a certain income in the first period and an uncertain income in the second period. Single women are prudent, which is defined by the convexity of the marginal utility u′′′ > 0, that is, they save for precautionary purposes. Then, as Proposition 1, Nordblom (2004) infers that married women will save less for precautionary purposes relative to single women. From this theoretical result and transitions in marital status, we hypothesize that the lower single women’s probability of marriage in the future, the more they will save for precautionary purposes. Therefore, we obtain the following testable prediction for empirical analysis:

Testable prediction 1

Single women with a lower probability of future marriage have more savings for precautionary purposes than those with a higher probability of getting married in the future.

However, it must be noted that marriage results in higher expected future income, as most Japanese women marry men who earn more than they do. Thus, even if single women are not prudent, single women who have a higher probability of future marriage will have less savings in general. These negative effects of the probability of marriage on savings are equivalent to the effects theoretically examined by Grossbard and Pereira (2010). Without breaking down savings by motivation, they say that women will save more if they expect to stay single than if they expect to marry in traditional societies in which single women expect to obtain a higher disposable income after marriage. If this is the case, saving is motivated by income smoothing over the lifetime, rather than precautionary purposes. Therefore, if women expect higher income after marriage, we will empirically observe a decrease in wealth in general. Thus, our second testable prediction is as follows:

Testable prediction 2

If income smoothing achieved through marriage to a higher-income spouse has an effect on the saving behavior of single women, then relative to those with a higher probability of future marriage, women with a lower probability of marriage in the future will be expected to have more savings in general.

2.2 Estimation model

To examine these two testable predictions, we use the following estimation equation:

The dependent variable \( W_{it} = \left( {w_{it} + \frac{{\sqrt {w_{it}^{2} + 1} }}{2}} \right) \) is the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation of the amount of wealth target, w it, broken down by purpose. In order to address the skewness of wealth data, we take the transformation, which is an alternative of the log transformations when variables take on zero.Footnote 3 This transformation gives us percentage changes in the amount of wealth target. For Testable Prediction 1, we use the following three variables for precautionary purpose: (a) the variable emergency, which represents the wealth target to prepare for illness, disaster, and emergency; (b) the variable no purpose, which represents the wealth target for general peace of mind and for no particular purpose; and (c), the variable retirement, which represents the wealth target for retirement. For Testable Prediction 2, we use the following two variables: (d), the variable durables, which represents the wealth target for purchasing consumer durables; and (e), the variable leisure, which represents the wealth target for spending on leisure activities.

In some cases savings for retirement are categorized as being part of lifecycle wealth. However, the categorization is quite controversial because savings for retirement and savings for precautionary purposes are similar, though retirements are further away in the future, given the age of the sample we use. Thus, it may be expected that they will go in the same direction. As Japan’s population ages and its birth rate drops, growing insecurity surrounding Japan’s pension system has been generating precautionary savings. In fact, using the same survey as we use, Murata (2003) points out that precautionary savings exist in Japan due to uncertainty concerning public pension benefits. She also notes that households begin to accrue precautionary savings when the respondents are as young as in their 30s. Therefore, we cannot ignore the precautionary aspect of retirement savings.

Our underlying assumption is that young single women’s saving behaviors are determined by their subjective probability of marriage. Our main explanatory variable is the dummy marriage it, which equals 1 if the woman gets married within the next 3 years, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 4 If, as Testable Prediction 1 states, the main purpose of saving among single women is precautionary, then we expect the coefficient of the dummy variable marriage it to be negative when the dependent variables are emergency, no purpose, and retirement. Meanwhile, if, as Testable Prediction 2 states, the main purpose of saving among single women is to achieve some of the income smoothing that married women achieve by marriage to a higher-income spouse, then we expect the coefficient of the dummy variable marriage it to be negative when the dependent variables are durables and leisure.

Z i is the set of variables that capture the lifecycle of respondents: age, age squared, dummy variables for working status (full-time worker), educational attainment (junior high-school graduate, high-school graduate, college graduate, and university graduate or more), father’s educational attainment (high-school graduate or more), residential status (living alone), annual income (income from zero to ¥2 million, income from ¥2 million to ¥4 million, income from ¥4 million to ¥6 million, income over ¥6 million), and survey wave (eleventh wave versus ninth wave).

3 The data

We use panel data from the Japanese Panel Survey of Consumers, provided by the Institute for Research on Household Economics. This panel survey was initiated in October 1993 and has been conducted annually since then.Footnote 5 In the panel survey, a stratified, two-stage random country-wide sample was collected, using the drop–off, pick–up method.Footnote 6

In the survey, each female respondent was tracked for multiple years, and so we could gauge her age profile against her marital status. In addition, since the ninth wave (year 2001), the subjects’ target wealth has been tracked by purpose for saving, so our analysis has been performed only the ninth and later waves.Footnote 7

In addition, the survey asks each female respondent about her preference for marriage, which is used as an instrumental variable for marriage it; it also asks for information on household demographics, including family size, age, education, income, and occupational status.

The reason we use wealth target rather than actual wealth is that it is only for wealth target that we can obtain the amounts broken down by purpose.Footnote 8 The probability of future marriage should affect not only precautionary savings but also savings for the other purposes. If the latter offsets the former partially or completely, it will contaminate the effect of the probability of future marriage. Therefore, it is better to use wealth target rather than actual wealth in our analysis. However, we have to note that these five categories of wealth target, (a)–(e), are not actual amounts. Unfortunately, the survey we use asks about the total amount of actual wealth, but not the amounts of actual wealth for various purposes. Therefore, we cannot clarify how closely the amounts of intended or targeted wealth categories (a)–(e) correspond to actual wealth. We only see how closely the total amount of intended or targeted wealth corresponds to actual wealth. There is a statistically significant difference between the two: the total amount of intended or targeted wealth is ¥8.22 million (with a standard deviation of ¥15.65 million), while the total amount of actual wealth is ¥2.69 million (and a standard deviation of ¥4.73 million).

The rationale for using 3 years to define the dummy variable marriage it is as follows. Suppose first that instead we used a period shorter than 3 years, i.e. 1 or 2 years, then there is the fear that we might commit a mistake by considering as “not expecting marriage” some of the women who have the intention and desire to get married and will get married. After couples are engaged, it may take more than one or 2 years to prepare for a wedding or a wedding ceremony. In fact, in our survey, among those who answered “I am engaged and going to get married” in response to a question about their preference for getting married—which we will address in the next section—74.9 % of them actually married within a year, while 9.0 and 4.1 % of them married in the second and the third years, respectively. Thus, a small, but not insignificant, number of single women with a certain expectations of getting married stay single for an additional 2 years. Next, suppose that we define “expected marriage” as marriage observed within four or more years, rather than 3 years. In such a case, we could commit the opposite mistake—that is, those who state that they have no intention or desire to marry may actually get married due to unexpected circumstances. In fact, in our survey, among those who answered, “I do not want to get married,” 3.2 % married in the fourth year and 5.5 % in the fifth year. Choosing marriage within 3 years seems to be the optimal way of addressing these concerns.

4 Estimation method

We outline our cross-sectional analysis methodology in Sect. 4.1, and then we explain our panel analysis in Sect. 4.2.

4.1 Cross-sectional analysis (instrumental variables)

In our cross-sectional analysis, we use the ninth and eleventh waves of the survey; thus, in this subsection, we remove the subscript t from the variables we use.

It is difficult to discuss the true impact of marriage i on W i due to endogeneity problems. It is highly likely that there are omitted variables, which could bias our estimated coefficients positively or negatively. For instance, single women with steady character may save more for precautionary purposes. Thus, the character is attractive to a potential husband, and could actually serve as a catalyst for positive bias. Also, we use the amount of wealth target as the dependent variable, which may also cause an omitted variable bias: wealth target does not necessarily correspond to actual wealth, and whether or not a woman achieves her desired level of wealth target may depend on her personality. In turn, those who are determined enough to achieve their goals are more likely to get married. Hence, given the amount of actual wealth, a single woman who has such a personality will tend to set modest and realizable targets, which generates a negative bias on the estimated coefficients. Furthermore, there may be reverse causality. A negative bias is brought about when a woman who spends more money increases her likelihood of marriage by creating more opportunities to meet a potential husband.

In order to resolve these endogeneity problems, we employ the Two-Stage least squares method using two instruments for marriage i. One has five dummy variables representing the respondent’s preferences or intentions for marriage. They are defined using the following survey questionnaire, which asks single female respondents about marriage preferences.

-

Question: Would you like to get married (based on legal definitions)?

-

Answer:

-

1.

I am engaged and going to get married.

-

2.

I would like to get married soon.

-

3.

I would like to get married—not soon, but eventually.

-

4.

It is not necessary to get married.

-

5.

I do not want to get married.

From this questionnaire, we construct five dummy variables: engaged, hope to marry soon, hope to marry eventually, not necessary to marry, do not want to marry. The base category of these variables is those who answer “I would like to get married soon” (hope to marry soon = 1).

Our empirical strategy is that marriage preferences, represented by these five dummy variables on marriage preferences, are not directly related to precautionary saving behavior, though it is likely that marriage preferences do affect marriage-oriented saving behavior. Those who have a strong preference for marriage will set aside a large amount of wealth for marriage expenditures, such as the wedding ceremony, honeymoon, and married life. As noted in Sect. 3, in this survey, questions about wealth target are segmented to include wealth target for reasons of marriage, as well as wealth target for precautionary purposes and for income smoothing. Therefore, marriage preference dummies may correlate with unobservable determinants of wealth for marriage reasons, while they do not correlate with those of wealth for precautionary purposes.Footnote 9 That is why marriage preferences are appropriate instruments for marriage i.

The other instrument is the percentage of unmarried women aged 24–35, by prefecture (unmarried rate) obtained from census data.Footnote 10 Since the census is conducted only every 5 years, we could not obtain the percentage for each cohort (ninth wave [2001] and eleventh wave [2003]); we therefore use the closest years: 2000 and 2005.

Whether or not a single woman ends up getting married depends on objective indicators such as education and income, as well as the above-mentioned marriage preferences and the percentage of unmarried women aged 24–35 by prefecture. Thus, we include the other control variables in Z i when we conduct the first-stage estimation.

The validity of the instruments will be formally tested in Sect. 6.1. In addition, see Appendix A.1 for more on the instrument variables.

4.2 Panel analysis

When it is more likely that an unmarried woman will not marry, how does her saving behavior change over time? To examine this question, we conduct a panel estimation. We expect that if a woman expects a low probability of marriage she will save more for precautionary purposes.

The two biases we mentioned in the previous subsection are due to the fixed effect of individual character and personality. In fact, such individual characteristics are stable and independent of the events related to employment, health, and family, as reported by Cobb-Clark and Schurer (2012), so we can mitigate these biases through panel analysis.

5 Sample selection and descriptive statistics

5.1 Sample selection

In the cross-sectional analysis, we use the ninth wave of cohorts A and B (i.e., from 2001) and the eleventh wave of cohort C (i.e., from 2003) of unmarried respondents, which include women who are now single but have been previously married.Footnote 11 There were a total of 817 observations (332 from cohorts A and B, and 485 from cohort C). We restrict the sample to respondents with no children, which reduces the number of observations from 817 to 741; we also restrict the sample to respondents whose marital status after three years is available, which further reduces the number from 741 to 566. In addition, for dependent variables (a)–(e), the numbers of observations were reduced to 525, 528, 525, 528, and 526, respectively. We avoid dropping observations by adding a category for “missing observation” for dummy explanatory variables (educational attainment, annual income, and working status).

In the panel analysis, there were a total of 866 (N = 2,079 and T = 2.40) observations from the ninth to the twelfth waves. Restricting the analysis to the respondents whose marital status after 3 years is available brings the number of observations down to 678. In addition, for dependent variables (a)–(e), the numbers of observations were reduced to 665, 662, 667, 668, and 666, respectively. The data on which we conduct both fixed-effects and random-effects regressions are from unbalanced panels.

5.2 Descriptive statistics

Tables 1 and 2 present descriptive statistics for the unmarried Japanese women used in the cross-sectional analysis. Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of continuous variables and of category variables. In the rightmost column, we put the mean values from other nationwide large-scale surveys, given that the number of observations used here is relatively small.

Respondent unmarried women were aged 24–42 years, with a mean of 28.7 years, which is close to the average age at first marriage (26.3 in 1995, 28.0 in 2005, and 28.8 in 2010 according to the Vital Statistics of Japan). In our sample, of the women unmarried at the starting wave of each cohort, 22.1 % got married within 3 years, as shown in marriage it in Table 1. How representative are the single women we use in our analysis? These relatively older and successful single women face lower income uncertainty due to their economic independence, and thus it may be likely that they have given up on finding a suitable partner. If this is the case, the probability of future marriage may have less impact on precautionary savings. However, women 36 years of age or older make up only 9.5 % of the single women in our analysis. We conduct our analyses using single women under 35 years of age but we do not have significantly different results from the following section.

With respect to marriage preferences, the proportion of respondents who would like to get married (hope to marry soon = 1 or hope to marry eventually = 1) was about 67.4 %; those who think that it is not necessary to get married (not necessary to marry = 1) comprised 23.1 %, and those who do not want to get married comprised only 3.2 % of the sample. Similar marriage preferences were observed in the National Fertility Survey in 2002, where 88.3 % of unmarried female respondents aged 18–34 answered “want to get married eventually,” while only 5.0 % answered “do not have an intention to get married” (6.7 % unknown). Thus, the fact that most respondents expect to get married is also observed in a large data source.

One noticeable characteristic of our sample is the large proportion living with their parents (79.1 %, living alone = 0 in Table 1). According to the National Fertility Survey, the proportion of Japanese unmarried women aged 25–29 who lived with their parents was 79.4 % in 1997 and 78.5 % in 2002; the numbers in those years fall to 72.1 and 76.1 %, respectively, for those aged 30–34 years. Hence, our data is representative in that respect too.Footnote 12

In addition, about 87.8 % of our survey’s respondents work [as full-time employees (61.8 %, working fulltime = 1) or part-time employees (26.0 %)]. According to the Labor Force Survey, in 2002 the labor force participation rate of unmarried women aged 25–34 was 82.5 % (70.5 % worked as full-time employees and 12.0 % worked as part-time employees).

Next, we examine wealth target with respect to precautionary savings. On average, the wealth target to prepare for illness, disaster, and emergency is ¥0.66 million, that for retirement is ¥1.45 million, and that for general peace of mind or for no particular purpose is ¥2.25 million. With respect to lifecycle wealth, the wealth target for purchasing consumer durables is ¥0.17 million, and that for spending on leisure activities is ¥0.26 million.

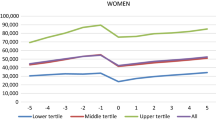

In Fig. 1 we show how wealth target changes as single respondents get closer to time of marriage. Here we use 180 single respondents who got married between the tenth and fifteenth waves. First, it can be seen that wealth target for precautionary purposes—emergency and no purpose—decreases from ¥0.83 million and ¥2.88 million 5 years prior to marriage to ¥0.50 million and ¥1.60 million 1 year prior to marriage, respectively, amounting to decreases of 39.4 and 44.4 %. In fact, for no purpose, we observe a statistically significant difference between one year before marriage and 4 years before marriage. Second, although target wealth for retirement rises sharply at 3 years before marriage, it decreases 56.2 % from 5 years prior to marriage to 1 year prior to marriage. We observe a statistically significant difference in retirement between 1 year before marriage and 3 years before marriage. However, durables shows little decrease (15.5 %) and leisure increases by 89.0 %, but the differences are not statistically significant.

Finally, a note about income: on average, the respondents’ annual income (i.e., not only income from work but also that from property, social security, allowance from parents, etc.) is ¥2.60 million. According to the National Survey of Family Income and Expenditure, in 1999, young single female households (aged under 30) had average earnings of ¥2.88 million annually, implying that our respondents have slightly lower earnings than those in the National Survey of Family Income and Expenditure (1999).

5.3 Descriptive statistics by marriage

Next, we compare respondents who remain unmarried (marriage = 0), those who eventually get married (marriage = 1), and those who dropped from the survey (marriage = n.a.). First, we see a difference in the wealth target for precautionary purposes between the respondents who remain unmarried and those who eventually get married. That is, the wealth target to prepare for illness, disaster, and emergency for those who remain unmarried is statistically higher than that of those who get married eventually. Moreover, we find a statistical difference in the wealth target for general peace of mind or for no particular purpose. Second, whether respondents remain unmarried or eventually get married is strongly correlated with marriage preference for. Those who remain unmarried were less likely to answer “engaged and going to get married” or “would like to get married soon” 3 years before than those who get married eventually, while those who remain unmarried were more likely to answer “hope to get married eventually,” “not necessary to get married,” or “do not want to get married” 3 years before than those who get married eventually.

6 Estimation results

In this section, we present our estimation results regarding the true impact of marriage it on Wit.

6.1 Results of the first-stage estimation (Table 3)

The results of the first-stage estimation based on probit regressions of marriage i for marriage preferences are presented. Table 3, these estimations are represented for different samples, is preparation for the second-stage estimation of the dependent variables: emergency, no purpose, retirement, durables, and leisure.

First, we find that for all samples in Table 3, the coefficients of engaged are positive and significant, and hope to marry eventually, not necessary to marry, and do not want to marry are negative and significant. (The base category being hope to marry soon = 1.) In specification (a), the coefficients of engaged, hope to marry eventually, not necessary to marry, and do not want to marry are 1.588, −0.668, −1.025, and −1.394, respectively, all of which are significant. With respect to the other four specifications, we find similar coefficients, all with statistical significance. These results suggest that respondents who have a strong fondness for marriage are more likely to marry within the next 3 years, whereas those who have less interest in marriage are less likely to do so.

The coefficients of control variables Z i are not included in Table 3, but we have several statistically significant coefficients: single women who are university graduates (or more) are less likely to marry within 3 years than high-school graduates, and single women who live alone are more likely to marry within 3 years than those who live with their family. From the coefficients of unmarried rate we infer that the respondents with a prefecture where there is a higher percentage of unmarried women aged 24–35 are not more or less likely to marry within the next 3 years.

Finally, we formally test the validity of the instruments. In the row pertaining to Hansen’s J test in Table 3 we report tests of the null hypothesis that all excluded instruments are exogenous. We find that in two out of five models—no purpose and leisure—we cannot reject this null hypothesis; this finding suggests that the four dummy variables for the marriage preferences and unmarried rate are exogenous in these first-stage estimations for no purpose and leisure. As for the second condition, F-statistics in the first-stage regression are much greater than 10 for the null hypothesis that the coefficients of the instrumental variables are equal to 0—a condition necessary for the instruments to be valid in all specifications.

6.2 Estimation results of cross-sectional analysis (Table 4 ) Footnote 13

Table 4 presents the estimation results of our cross-sectional analysis of taking into account the endogeneity of the variable marriage i. Predicted values of marriage i, \( \widehat{marriage}_{i} \)were estimated in the first-stage.

First, in column (b)—where the dependent variable is no purpose—\( \widehat{marriage}_{i} \) has a negative and significant coefficient. That is, a one percentage point increase in the predicted probability of marrying within 3 years decreases the wealth target for preparing for general peace of mind or for no particular purpose by approximately 1.64 percent. This result supports Testable Prediction 1: if single women do not expect future marriage, they intend to have greater precautionary savings if they expect marriage.

With respect to the control variables Z i, there are positive and significant coefficients of income 2–4 months and income 4–6 months in columns (a) and (b). For example, single women with annual incomes ranging from ¥4 million to ¥6 million have wealth targets to prepare for illness, disaster, and emergency that are approximately 104.8 % (= 100[exp(0.717)–1]) higher than those of single women with annual income ranging from zero to ¥2 million.Footnote 14 Hence, the higher a single woman’s annual income, the higher her wealth target for precautionary purposes. In addition, both junior high and university have negative and significant coefficients in column (b)—that is, a single woman who is a junior high-school graduate has wealth target for general peace of mind or for no particular purpose approximately 88.6 % lower, and one who is a university graduate 50.4 % lower, than a single woman who is a high-school graduate. The negative coefficient of university might indicate that single women with higher education are more economically independent than those with lower education. Consequently, they do not face as much uncertainty regarding future income and do not need to save as much for precautionary purposes. The coefficient of age is positive and significant and that of age squared is negative and significant in column (b). This implies that unmarried women’s wealth target for precautionary purposes for unmarried woman increases up to the age of 33.1 \( \left( { \approx \frac{0.795}{2 \times 0.012}} \right) \) and then decreases. The coefficient of previously married is negative and significant in column (b)—that is, a single woman who was previously married has approximately 78.6 % less wealth target for general peace of mind and for no particular purpose than a single woman who has never married.

We now turn to columns (d)–(e), where the dependent variables are durables and leisure. Here we find that the coefficients of \( \widehat{marriage}_{i} \)are insignificant. From this result, we cannot support Testable Prediction 2. That is, marriage to a higher-income spouse does not result in lower saving in general.

With respect to the control variables Z i, a university education has positive and significant coefficients in columns (d) and (e) (wealth target for purchasing consumer durables and for spending on leisure activities are approximately 376.4 and 264.0 % higher than in the case of a high-school graduate). In addition, college has a positive and significant coefficient in column (e), and junior high has a negative and significant coefficient in column (d). Also, age squared and working fulltime in column (c) and income 4m–6m in column (e) are positive and significant, and living alone in column (e) is negative.

We did robustness checks with different specifications of the variable marriage. When we defined the variable marriage as marriage within 2 years (which increases the sample size from 566 to 605), we obtained the same first stage results as when marriage is defined with 3 years. However, in the second stage, the coefficient of \( \widehat{marriage}_{i} \) is negative and significant only in the case of the no purpose regressions, and the absolute value of the coefficient gets smaller. We defined the variable marriage as marriage within 4 years (which decreases the sample size from 566 to 526). Then, in the first stage, the coefficient of the other instrument unmarried rate (the percentage of unmarried women aged 24–35, by prefecture) becomes statistically significant, and in the second stage, the coefficient of \( \widehat{marriage}_{i} \) is negative and significant in the case of the emergency and no purpose regressions and the absolute values of the coefficients get larger. Thus, we see consistently that the more years are used for defining marriage, the larger the impact of single status on precautionary savings. These robustness checks are consistent with Fig. 1, which implies that there seems to be a relationship between wealth target and the “countdown” to marriage.

6.3 Estimation results of panel data analysis (Table 5)

The first six columns of Table 5 present the results of the dependent variables emergency, no purpose, and retirement. There, marriage it has negative and significant coefficients in columns (a-1), (b-1), and (c-1). With respect to the Hausman test, which is a test of fixed versus random effects, we obtain p values of 33.4, 0.5, and 44.5 % for estimations of emergency, no purpose, and retirement, respectively, implying that the random-effect and fixed-effect estimates are so close that it does not matter which is used for estimations of emergency and retirement, whereas we have to use the fixed-effects estimation for no purpose. That is, our estimations in columns (a-1) and (c-1) find that compared with young women who are likely to get married within 3 years, women who are not plan to have approximately 43.5 % more savings for preparing for illness, disaster, and emergency, and approximately 108.2 % more for retirement. Thus, the expectations of remaining single in the future lead to more savings for preparing for illness, disaster, and emergency and for retirement, which supports our Testable Prediction 1.

With respect to the control variables, we present the results of the random effects estimation in column (a-1) and the fixed effects estimation in column (b-2). We obtain positive and significant coefficients of income in columns (a-1)—that is, single women with annual income ranging from ¥4 million to ¥6 million have wealth targets to prepare for illness, disaster, and emergency that are approximately 165.4 % [= 100(exp(0.976)-1)] higher than single women with annual income ranging from zero to ¥2 million. Additionally, living alone has a positive coefficient in columns (a-1) and (b-2)—that is, a single woman who lives alone has wealth target to prepare for illness, disaster, and emergency that is approximately 66.5 % [= 100(exp(0.510)-1)] higher than a single woman who lives with her family.

The last four columns of Table 5 present the panel-analysis results, where the dependent variables are durables and leisure. There, marriage it has a negative and significant coefficient in column (e-2)—that is, compared with young women who are likely to get married within three years, women who are not plan to have approximately 222.5 % more savings for leisure, but has no significant impact on saving goals for durables. Note that the Hausman test cannot be rejected. This supports Testable Prediction 2. That is, marriage to a higher-income spouse results in lower saving in general.

In the panel estimations for retirement, durables, and leisure, we obtain several significant control-variable coefficients. Similar to the previous cross-section estimations, we obtain a positive and significant coefficient of working fulltime in column (c-1); and positive and significant coefficients of income 4m–6m and income 6m or more in columns (c-1), (e-1), and (e-2).

7 Discussion and conclusion

We conducted estimations of wealth target for precautionary purposes. The results support our testable prediction that single women who expect to remain single plan to have more precautionary savings than those who expect to get married.

In our cross-sectional analysis, relative to single women who get married within 3 years single women who do not get married within 3 years have higher wealth targets to prepare for general peace of mind or for no particular purpose. Our panel analysis also shows that relative to single women who get married within 3 years, those who do not get married within 3 years have higher wealth target for preparing for illness, disaster, and emergency and for retirement. These findings enable us to conclude that expectations of remaining single in the future promote women’s precautionary savings.

Moreover, in our panel analysis, we find that compared with women who are likely to get married within 3 years, women who are not plan to have more savings for leisure. From this result, we cannot deny the possibility that our second testable prediction holds—that is, marriage to a higher-income spouse implies an income-smoothing motive.

With respect to the magnitude of the coefficients, expected single status has the largest impact on wealth targets for general peace of mind and for no particular purpose in cross-sectional analysis (163.8 % more target wealth). Moreover, our panel analysis indicates that expected single status has a statistically significant impact on wealth targets to prepare for illness, disaster, and emergency (43.5 % more wealth target) and for retirement (108.2 % more wealth target).

A number of our results can be explained in terms of our testable prediction that the less a single woman expects to get married, the higher the amount she is likely to save for precautionary purposes.

Although there is no existing literature in Japan that explicitly addresses the impact of single status on precautionary savings, Bishop (2005), who uses the same dataset we use and runs regressions with attained and factual wealth as the dependent variables, hints that unmarried women in Japan have stronger precautionary saving motives than married women. Using the samples consisting of both married and unmarried women, he finds that a one percentage increase in permanent income volatility produces about a 10 % increase in wealth, but for a sample of continuously married couples he did not find significant effects of either permanent or transitory income volatility. Moreover, Horioka and Watanabe (1997), using micro data from the Survey on the Financial Asset Choice of Households, find that net saving for the precautionary motive and for the retirement motive dominate all other motives for saving(net saving for the illness motive and the peace of mind motive accounts for 56.0 % of total net saving for all motives). In addition to this, Zhou (2003), using data on 2,441 Japanese households taken from the 1996 Survey on the Financial Asset Choice of Households, concludes that the precautionary saving model fits the results well and income uncertainty has a statistically significant impact on Japanese household savings. Our results are thus broadly consistent with a series of previous findings that precautionary motives play an important role in explaining savings in Japan.

Notes

With respect to same-sex couples’ family formation, Negrusa and Oreffice (2011) analyze their household financial decisions using the 2000 US census data.

We thank the co-editor, F. Woolley, for suggesting the use of this transformation.

Pericoli and Ventura (2011) use whether or not the married couple will be divorced or separated after 2 years as the marital disruption risk when they examine the consequences of family dissolution risk onto consumption and saving.

The data contain 15 waves (1993–2007). In 1993, the survey started with 1,500 women (1,002 married women and 498 single women) between 24 and 34 years of age as of October 1993 (cohort A). In 1997, 500 women between 24 and 27 years of age as of October 1997 (201 married women and 299 single women) were added (cohort B); in 2003, 836 women between 24 and 29 years of age as of October 2003 (351 married women and 485 single women) were added (cohort C).

The drop–off, pick–up method is conducted as follows: First, a census taker visits randomly selected households and leaves a hard copy of the questionnaire. Next, the selected households respond to the questionnaire within a given time period, and then the census takers collect the completed questionnaires by visiting the households again at a convenient time. According to Sakamoto (2006), 42.2% of respondents in cohort A were lost from cumulative attrition from the first to the eleventh wave, which is larger than the first 11-year cumulative attrition rate of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (32.2%).

The time frame to which the wealth target variables refer is clear only in the ninth and tenth waves since the survey ascertains the timeframe with the question, “In how many years do you expect to reach your wealth target?” From the answer to the question, the unmarried respondents expected to reach their wealth target level in a shorter period of time than the married respondents. The difference in the time frame is the largest for no purpose (6.3 years for unmarried vs. 10.7 years for married).

Some might argue that saving is fungible and that it does not make sense to speak of saving for a specific motive, but we disagree with this argument for the following two reasons: first, household surveys consistently find that respondents are able to allocate their savings and wealth among specific motives (see, for example, Horioka and Watanabe (1997)). Second, in Japan, there are many types of saving accounts for specific motives, such as housing purchase and retirement, and penalties are imposed if the funds are used for a different purpose.

The instrument could be invalid if these five dummy variables on the preferences for marriage have direct effects on wealth target, whereas when we regress wealth target on these five dummy variables on the preferences for marriage, these five dummies have insignificant coefficients.

In Japan, “prefecture” is a general term for 47 local public entities. They include cities, towns, and villages. According to the 2005 census, the most populated prefecture is Tokyo (12.5 million), while the least populated is Tottori (0.6 million).

Single mothers are not excluded by design, but we drop them.

The survey collects information about inheritance. However, more than 99% of the respondents neither received financial or real assets as intervivos and inheritance from their parents in the past nor expected to receive them in the future.

Detailed regression results of Tables 4 and 5 are available from the internet (http://www.ipss.go.jp/pr-ad/e/Self/kozin/kureishi_e.html).

We thank the co-editor, F. Woolley, for suggesting the interpretation of dummy coefficients. The same applies to the following dummy coefficients.

The options are as follows: (1) a meeting arranged by relatives and families, (2) a meeting arranged by friends, (3) asked friends and relatives to introduce a male marriage partner, (4) joined a matrimonial agency in the last year, (5) continued to be part of a matrimonial agency over the year, (6) read a bridal magazine, (7) talked about marriage with a boyfriend, (8) got engaged, (9) other, and (10) did nothing.

References

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81(4), 813–846.

Becker, G. S. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bessho, S., & Tobita, E. (2008). Unemployment risk and buffer-stock saving: An empirical investigation in Japan. Japan and the World Economy, 20(3), 303–325.

Bishop, T. “Precautionary Saving by Japanese Households.” (2005) mimeo. Available from URL: http://www.econ.ucdavis.edu/faculty/twbishop/html/Japan_precaution.pdf.

Carroll, C. D., & Samwick, A. (1998). How important is precautionary savings? Review of Economics and Statistics, 80, 410–419.

Chami, R., & Hess, G. D. (2005). For better or for worse? state-level marital formation and risk sharing. Review of Economics of the Household, 3(4), 367–385.

Cobb-Clark, D., & Schurer, S. (2012). The stability of big-five personality traits. Economics Letters, 115, 11–15.

Dardanoni, V. (1991). Precautionary savings under income uncertainty: A cross-sectional analysis. Applied Economics, 23, 153–160.

Dynan, K. E. (1993). How prudent are consumers? Journal of Political Economy, 101, 1104–1113.

Grossbard, S. A. and A. M. Pereira. “Will Women Save More Than Men? A Theoretical Model of Savings and Marriage” (2010), CESifo Working Paper Series No. 3146. Available from URL: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1655648.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. (1993). On the economics of marriage: A theory of marriage, labor, and divorce. Boulder: Westview Press.

Horioka, C. Y., & Watanabe, W. (1997). Why do people save? A micro-analysis of motives for household saving in Japan. The Economic Journal, 107(442), 537–552.

Horioka, C. Y., Fujisaki, H., Watanabe, W., & Kouno, T. (2000). Are Americans more altruistic than the Japanese? A US–Japan comparison of saving and bequest motives. International Economic Journal, 14(1), 1–31.

Kazarosian, M. (1997). Precautionary savings: A panel study. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 79(2), 241–247.

Kohara, M. (2009). The response of Japanese wives’ labor supply to husbands’ job loss. Journal of Population Economics, 23(4), 1133–1149.

Lusardi, A. (1998). On the importance of the precautionary saving motive. American Economic Review, 88, 449–453.

Mincer, J. (1962). Labor force participation of married women: A study of labor supply. In H. Gregg Lewis (Ed.), Aspects of labor economics: A conference of the universities national bureau committee for economic research (pp. 63–85). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Murata, K. (2003). Precautionary saving and income uncertainty: Evidence from Japanese micro data. Monetary and Economic Studies, 21(3), 21–52.

Negrusa, B., & Oreffice, S. (2011). Sexual orientation and household financial decisions: Evidence from couples in the United States. Review of Economics of the Household, 9(4), 445–463.

Nordblom, K. (2004). Cohabitation and marriage in a risky world. Review of Economics of the Household, 2(3), 325–340.

Pericoli, F. and L. Ventura “Family Dissolution and Precautionary Savings: An Empirical Analysis.” Review of Economics of the Household (2011): 1–23.

Sakamoto, K. (2006). Analysis of sample attrition: Verification of defining factors of attrition and sample selection biases using Japanese panel survey of consumers. The Japanese Journal of Labour Studies, 48(6), 55–70. (in Japanese).

The National Fertility Survey, the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 1997 and 2002.

The labor force survey, statistics Bureau, Ministry of internal affairs and communications, 2002.

The National Survey of Family Income and Expenditure, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 1999.

The Vital Statistics of Japan, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2011.

Zhou, Y. (2003). Precautionary saving and earnings uncertainty in Japan: A household-level analysis. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 17(2), 192–212.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to Charles Yuji Horioka for his kind advice and comments throughout the process of writing this paper. We would also like to thank Setsuya Fukuda, Hidehiko Ichimura, Yukinobu Kitamura, Ayako Kondo, Colin McKenzie, Kei Sakata, Shizuka Sekita, and the participants at the Kansai Labor Economics Seminar, the Horioka seminar, the Empirical Micro Research Seminar at Tokyo University, the seminar at the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, and the 2011 spring annual meeting of the Japanese Economic Association for their helpful comments and discussion. We are deeply indebted to the editor, S. Grossbard, and co-editor, F. Woolley, as well as to two anonymous referees for their very helpful comments. We also thank the Institute for Research on Household Economics for permitting us to use data from “the Japanese Panel Survey of Consumers (JPSC).” Finally, we are indebted to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of the Japanese government for the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (#22330094, #24730262 and #22330083) supporting this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: The validity of the instrumental variables

Appendix: The validity of the instrumental variables

We need to check the validity of the five dummy variables for the marriage preferences or intentions and unmarried rate as instruments. First, these variables should not correlate with the error term of our estimation equation (1) in Sect. 2.1—that is, the unobservable determinants of wealth for precautionary purposes. Second, these variables should partially correlate with marriage i, once the impact of the other exogenous variables has been netted out.

1.1 Variables for the marriage preferences or intentions

We discuss whether the five dummy variables for the marriage preferences are valid as an instrument. Since we have already discussed the first condition in Sect. 4.1, we consider the second condition here. We can anticipate that respondents who are very fond of the idea of marriage are more likely to marry. In the survey questionnaire we use, the survey asks, “Did you engage in some activities related to marriage during the last year?”; multiple answers were allowed.Footnote 15 The answers from our 590 respondents indicate that those who have a strong marriage preference are more likely to undertake more than one activity related to marriage. In fact, 81.8 % of those who answered “I am engaged and going to get married” (engaged = 1) undertook more than one activity related to marriage, while 70.5 % of those who answered “I would like to get married soon“(hope to marry soon = 1) and 35.7 % of those who answered “I would like to get married, not soon, but eventually” (hope to marry eventually = 1) did so. These findings imply that those with a strong marriage preference are active with regard to marriage, and such activities provide them with greater chances of meeting a marriage partner and getting married in the future.

1.1.1 Unmarried rate

Next, we examine whether the percentage of unmarried women aged 24–35 by prefecture (unmarried rate) is valid as an instrument. We needed to ascertain that the first condition—that interprefectural variations in the ratio of the unmarried women are unlikely to correlate with unobservable determinants of saving behavior—is reasonable. It is obvious that the ratio of unmarried women by prefecture does not affect individual-level saving behavior.

We consider the second condition—that is, whether or not this ratio correlates with \( \widehat{marriage}_{i} \). It is reasonable that in a prefecture where the ratio of unmarried women is high, it is more likely that the respondents will remain unmarried. This is because of a specific feature of the mobility of women in Japan. That is, there is a gender gap: women leave home for marriage, while men leave home before marriage. Actually, Suzuki (2003), who uses the Fourth National Survey on Household Changes, shows that in Japan the proportions of home leaving associated with marriage are 20.5 % for males and 52.9 % for females, which is in sharp contrast to Western countries. From this immobility of unmarried women in Japan, a higher share of unmarried women in a prefecture implies that there are many marriage competitors, and thus it is difficult to find a marriage partner in the prefecture. Therefore, the percentage of unmarried women by prefecture will be a good indicator of their ability to get married. In addition, this can be understood to mean that in an environment with a large number of unmarried women, being unmarried becomes a norm of sorts, and unmarried women therefore may not feel anxious about being single.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kureishi, W., Wakabayashi, M. What motivates single women to save? the case of Japan. Rev Econ Household 11, 681–704 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9191-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9191-z