Abstract

More than ½ of the foreign born workforce in the US have no schooling beyond high school and about 20% of the low-skilled workforce are immigrants. More than 10% of these low-skilled immigrants are self-employed. Utilizing longitudinal data from the 1996, 2001 and 2004 Survey of Income and Program Participation panels, this paper analyzes the returns to self-employment among low-skilled immigrants. We find that the returns to low-skilled self-employment among immigrants is higher than it is among natives but also that wage/salary employment is a more financially rewarding option for most low-skilled immigrants. In analyses of earnings differences, we find that most of the 20% male native-immigrant earnings gap among low-skilled business owners can be explained primarily by differences in the ethnic composition. Low-skilled female foreign born entrepreneurs are found to have earnings roughly equal to otherwise observationally similar self-employed native born women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Immigration has grown steadily over the last decades. Approximately 16% of the US workforce was foreign born in 2007, a proportion that more than doubled since its 7% share in 1980 Lofstrom (2009). Over the same time period, self-employment grew strongly and immigrants continued to increase their share of business owners.Footnote 1 Figure 1 reveals an increase of close to 7.5 million business owners from 1980 to 2007 and that immigrants’ share of self-employment increased from about 6.6% to approximately 17.4%.Footnote 2

Although many immigrants are highly educated and skilled, immigrants also represent a rising large share of the country’s low-skilled workers, defined here to be those with no more than a high school diploma. Table 1 shows that while the immigrant proportion of the college educated workforce increased from 7.1% in 1980 to 15.2% in 2007, the immigrant share of skilled workers remains roughly equal to the overall proportion of immigrants in the US workforce. However, over this period the share of immigrants in the low-skilled segment of the labor force more than tripled, from 6.7 to 20.4%, making low-skilled immigrants considerably over-represented among the least educated workers.

Relatively little is known about the labor market performance of this large and growing group of immigrants. Low-skilled workers in general do not fare well in today’s skill intensive economy and their opportunities continue to diminish. Given that individuals in this skill segment of the workforce are more likely to have poor experiences in the labor market, and hence incur greater public expenses, it is particularly important to seek and evaluate their labor market options. From the perspective of immigrant workforce integration, economic contribution and policy, it is also of importance to know specifically how low-skilled immigrants perform in the labor market.

In this paper we focus on the labor market performance of low-skilled self-employed immigrants. Self-employment has been argued to be an important stepping stone for economic assimilation among immigrants (e.g. Cummings 1980) and self-employed immigrants have been found to do better than their wage/salary counterpart (Lofstrom 2002). It is however unknown whether the relative success among immigrant entrepreneurs hold among the ones with relatively low schooling levels. The research question we seek to answer is whether self-employment is an economically rewarding option for low-skilled immigrants. We address this issue by comparing low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs to low-skilled immigrants working in the wage/salary sector as well as low-skilled native born business owners.

A large number of business owners in the US are low-skilled. In 2007, 6.9 million business owners did not have any education beyond high school, representing about 40% of the total number of self-employed (Lofstrom 2009). Importantly, foreign born entrepreneurs play an increasingly important role. This is evident in recent data which show that the entire net increase from 1980 to 2007 of about 1.1 million low-skilled self-employed workers is due to immigrant entrepreneurs (Lofstrom 2009). In fact, there are fewer native born low-skilled business owners today compared to 1980. This is not due to a decrease in the low-skilled native self-employment rate. In fact, the self-employment rate for both native born low-skilled men and women increased from 1980 to 2007, from 10.1 to 11% and 3.9–6.1%, respectively for men and women (Lofstrom 2009). The self-employment rate among the low-skilled foreign born population increased over the same period from 9.8 to 10.5% among men and remarkably from 4.2 to 10.6% for women. It is clear from this that self-employment now plays a particularly important role among low-skilled immigrants, especially foreign born women who are now slightly more likely to be self-employed than foreign born men.

The economic returns to self-employment have previously been rather extensively examined. Studies from the 1980s find that potential wages and wage growth of entrepreneurs are higher or not significantly different from the wages and growth of paid employees (for example, Brock and Evans 1986; Rees and Shah 1986 and Evans and Leighton 1989). However, Hamilton (2000) finds that most entrepreneurs have both lower initial earnings and lower earnings growth than they would receive in paid employment. He finds that earlier results indicating relatively high returns to self-employment may be influenced by a handful of high-income entrepreneurial “superstars”. The observed higher average earnings may thus not characterize the self-employment returns of most business owners.

Surprisingly, existing research on low-skilled self-employment, and the performance of low-skilled entrepreneurs, is scant. Exceptions include two papers by Robert Fairlie (2004, 2005). Fairlie (2004) studies young less-educated business owners and finds that after a few initial years of slower growth, the average earnings for the self-employed grow faster over time than the average earnings for wage/salary workers. Fairlie (2005) defines disadvantaged differently and focuses on family background (parents’ education). He finds some evidence that disadvantaged self-employed business owners earn more than wage/salary workers from disadvantaged families. Also relevant is Holtz-Eakin et al. (2000) who find that low-income self-employed individuals moved ahead in the earnings distribution relative to those who remained in wage/salary work.

This paper contributes to the limited existing research on low-skilled immigrants and low-skilled entrepreneurship in several ways. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to analyze the labor market performance of low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs in the US. We also build on Fairlie’s research by separately comparing and analyzing the earnings of low-skilled immigrants and natives. Furthermore, we include individuals of all working ages (defined here to be ages 18–64).

2 Comparing earnings of the self-employed and wage/salary workers

A key objective of the paper is to assess the relative success of immigrant low-skilled entrepreneurs compared to low-skilled wage/salary workers. The measures of success used are based on total annual earnings because these outcome measures closely reflect the overall economic well being of individuals.

An important issue to consider when comparing earnings between self-employed and wage/salary workers is the fact that self-employment earnings do not only represent returns to human capital but also returns to financial capital invested in the business. That is, reported self-employment earnings partially reflect a return to owner investments made in the business while wage/salary earnings do not. In addition to using total annual earnings, we therefore generate an alternative earnings measure, similar to Fairlie (2005).

The alternative measure entails subtracting a portion of the earnings of the self-employed, which roughly represents owner returns to investments of resources in their small businesses. Hence, we utilize the reported dollar amount of business equity information available in our data (discussed below) and subtract from annual earnings an amount equal to 5% of this business equity, representing an inflation adjusted real return to a relatively risky investment. Use of the 5% figure is a reflection of the opportunity cost of capital. We refer to this measure as “business equity-adjusted” earnings, which we interpret as an income measure that reflects only returns to human capital for both employed workers and the self-employed.

Although we argue above that the use of a 5% real discount rate is reasonable in this setting, clearly the specific choice of a return to business equity to subtract from the reported annual earnings is ad hoc. The impact of alternative returns is that a higher interest rate leads to lower business equity adjusted earnings while a lower discount rate leads to more favorable comparison for the self-employed (a zero discount rate generates a measure identical to our total annual earnings measure). Lastly, we note that the use of an assumed real return of 5% is similar to Fairlie and Robert (2004) approach and that given the relatively low levels of business equity among low-skilled entrepreneurs, the results are not sensitive to minor changes in the assumed discount rate.

3 Data and descriptive statistics

We use nationally representative individual longitudinal data from the 1996, 2001 and 2004 panels of the US. Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). The SIPP data contain individual demographic information as well as detailed information on labor market activities, business ownership and business characteristics.Footnote 3

The sample utilized is restricted to low-skilled individuals, men and women, between the ages of 18 and 64 in the survey period who report working at least 15 h per week. Furthermore, we restrict our sample to individuals for whom immigration status is available and who are observed at least 2 years during the sample period. The latter restriction is necessary for our earnings growth analysis which relies on an individual fixed effects specification.

We define an individual to be self-employed if she/he reported owning a business in the sample month and usually working at least 15 h per week in that business. Similarly, individuals are defined to be wage/salary workers, or employees, if she/he does not report owning a business but work at least 15 h per week in their current job.

We start by examining our annual earnings measures to see how low-skilled entrepreneurs compare to wage/salary earners, shown in Table 1. Our data show that low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs have higher average annual earnings than their counterparts in wage/salary employment and that this also holds among foreign born women. However, female US born business owners earn less on average than US born women wage/salary earners.

The magnitude of the differences in average annual earnings depends on the earnings measure. Foreign born male business owners earn on average between 13% (business equity adjusted earnings) and 26% (total annual earnings) more than immigrant men in wage/salary employment. The corresponding average female immigrant self-employment advantage is somewhat lower, between 7 and 11%. Although immigrants earn less on average than their native counterparts, the mean earnings differences above indicate that self-employment is a more financially rewarding option for foreign born entrepreneurs than it is for US born business owners. Among native born low-skilled women, business owners have even lower mean earnings than their counterparts in wage/salary employment.

A comparison of average earnings can be misleading if the success story among entrepreneurs is one of relatively few very successful business owners (Hamilton 2000). A comparison of earnings by selected percentiles reveals that there is truth to this assertion among the low-skilled. The median annual earnings of low-skilled entrepreneurs—US and foreign born men and women—are lower than those of low-skilled employees in the same group. Although the magnitudes of the self-employment disadvantage differ across the two measures, there is no instance in which median earnings are higher among business owners.

The comparison of median earnings differences between wage/salary workers and business owners also indicates lower earnings among immigrants than natives. However, the self-employment disadvantage is smaller among immigrants, indicating that self-employment is a relatively more rewarding for the foreign born than it is among the US born; a similar conclusion to the one reached by comparing average earnings. We also note that the self-employment median earnings disadvantages shown in Table 1 are very close to the mean earnings differences in the log of annual earnings, the measure used in our empirical approach below. In other words, the log transformation of annual earnings reduces the influence of the highest earning individuals and hence comparisons of mean log annual earnings are more in line with comparisons of median earnings.

Table 1 shows that among foreign born men, approximately the top half of business owners do as well or outperform the top half of immigrant wage/salary earners. Among natives, the self-employment earnings advantage is not quite as prevalent. However, we observe that at least the top 25% low-skilled native born male entrepreneurs have higher earnings than the top 25% wage/salary workers. As expected, once self-employment earnings are adjusted for returns to capital invested in the business, self-employment is less rewarding compared to wage/salary work.

The top 25% female immigrant entrepreneurs have roughly the same or higher earnings than their foreign born counterparts who work in the wage/salary sector. Native born low-skilled business owners are relatively less successful, when compared to their employee counterparts. Table 1 shows that among US born women only the top 10% of entrepreneurs outperform the top 10% wage/salary workers. In fact, when we adjust earnings for business equity, native born self-employed women throughout the distribution have lower earnings than their employee counterpart.

Immigrant men have lower earnings than native born men. However, the earnings summary statistics in Table 1 indicate that the native-immigrant earnings gap is somewhat smaller among some low-skilled entrepreneurs, namely the ones in the upper end of the earnings distribution. For example, among male entrepreneurs in the top decile, the immigrant-native earnings gap is approximately 10%. Among wage/salary earners in the top decile, the gap is twice that, about 21%. The data also indicate that both among male low-skilled business owners and wage/salary employees the median native-immigrant earnings gap is about 20%.

Female immigrant entrepreneurs appear quite successful when compared to their US born counterpart. A comparison of the mean and median total annual earnings of native and immigrant self-employed women shows no statistically significant earnings difference. Interestingly, a look at the equity adjusted earnings measure reveals that self-employed immigrant women have between 8% (median) to 18% (mean) higher earnings than low-skilled native self-employed women. This shows that US born female business owners have higher levels of business equity and that these higher levels of equity makes an immigrant-native comparison, not accounting for business equity differences, more favorable to female native entrepreneurs. This is similar to previous research on earnings differences between Latina and non-Hispanic white female business owners (Lofstrom and Bates 2009). The impact of business equity differences between immigrant and native male entrepreneurs is much smaller.

The above descriptive statistics indicate that most low-skilled entrepreneurs have lower earnings than wage/salary workers but also that the economic returns to self-employment are higher for immigrants than natives. Furthermore, compared to low-skilled natives in the same sector, immigrant entrepreneurs are relatively more successful than foreign born wage/salary workers. The latter two observations are important since much of the growth in low-skilled self-employment is among immigrants and that low-skilled immigrants have higher self-employment rates than low-skilled natives. The relative, compared to natives, financial attractiveness of self-employment is one plausible reason for this.

Some of the observed earnings differences between entrepreneurs and employees may not be attributable to self-employment but may be due to differences in earnings relevant demographic traits (such as education, age, family composition, ethnic composition) or workforce characteristics (such as the number of hours worked, previous period’s employment status and workforce experience). A look at differences in the above characteristics between workers in the two sectors indicates that the self-employed possess on average more of the attributes associated with higher earnings than wage/salary workers.Footnote 4 The extent to how these factors affect earnings and how they contribute to earnings differences across groups are central to our empirical analysis.

4 Empirical model specifications

Our objective is to assess the relative success of immigrant low-skilled entrepreneurs compared to both low-skilled immigrant wage/salary workers and low-skilled native born business owners. We focus on total annual earnings as our measure of success.

We use ordinary least squares (OLS) to estimate regression models of the log of total annual earnings, y ijt , of individual i in state j at year t. This measure is defined as the log of the sum of wage/salary earnings and self-employment earnings. The model specification is;

Where;

-

X it = Matrix containing individual characteristics such as age, educational attainment, marital status, family composition and ethnicity. For immigrants it also includes controls for years since migration and naturalization.

-

LFSit−1 = Matrix containing controls for lagged the labor force status, i.e. whether the person was observed in wage/salary work, part-time self-employment, part-time self-employment, unemployed, welfare participation or not in the labor force. The matrix also includes controls for number of years at job for wage/salary workers and years in business for the self-employed.

-

γj = State fixed effect

-

τt = Year fixed effect

The use of lagged labor force status are included to reduce omitted variable bias of parameters of interest. Put differently, these controls are intended to purge the data of the impact of previous labor market outcomes or decisions on earnings. Furthermore, since repeated individual observations are not assumed to be independent, all estimates are clustered on individuals.

We also estimate individual fixed effects models to obtain estimates of the impact of years in business or years at current job. In this specification, we do not include lagged labor force status, since it is time invariant for certain sub-groups, including all individuals who stayed in business or remained in the same job for the full sample period. We do however include a control for hours worked per week.Footnote 5 Lastly, since the analysis is based on a sample in which individuals are not randomly assigned to different labor market states, and that due to no credible instrument is available, we do not model the selection into self-employment. Consequently, the presented estimates are not clearly causal.

5 Empirical results

The earnings regression results show, as expected, that factors like age, education, experience and hours work have positive impacts on earnings, shown in Tables 2 and 3. Among low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs, we do not find that time since migration has much of an impact on earnings nor do the data reveal a significant relationship between naturalization and self-employment earnings.Footnote 6 This is contrary to the wage/salary estimates which indicate a positive relationship between these assimilation variables and earnings. Although the minority earnings disadvantages vary across the two sectors, the results show lower earnings among African-Americans and Hispanics.

To specifically analyze how observable earnings related factors affect the earnings differences between wage/salary workers and the self-employed we use an Oaxaca earnings decompositions. Before doing so, we note that a look at the differences in the mean of the log of total annual earnings, shown in Table 4, shows that the earnings of self-employed immigrant men is about 4% lower than the earnings of immigrant men in wage/salary employment. This is roughly equal to the self-employment earnings disadvantage among low-skilled native born men. Among women, the self-employment log earnings gap is substantially smaller among immigrants (15%) than it is among US born women (40%).

We use the regression estimates in Tables 2 and 3 and the sample means to determine how much each observable factor contributes to the mean log earning gaps. This exercise, results presented in Table 4, clearly shows that differences in the observable characteristics do not explain lower earnings among most of the self-employed when compared to wage/salary workers. In fact, the decomposition analysis shows that for all groups the self-employment earnings disadvantages are greater once these factors are considered.

5.1 Native-immigrant earnings differences

Low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs have lower earnings than native born entrepreneurs. The log annual earnings of foreign born male entrepreneurs are about 20% lower than those of native born entrepreneurs. This is also roughly the native-immigrant earnings gap for both men and women in the wage/salary sector. Female immigrant business owners, however, do not have statistically significantly lower earnings than their native counterpart. The role of differences in observable characteristics in explaining earnings differences can also be answered by utilizing an Oaxaca earnings decomposition, this time between foreign and US born individuals working in the same sector.

The results, shown in Table 5, show that among self-employed men, the most important factor contributing to the native-immigrant earnings gap is the difference in the ethnic composition of low-skilled business owners. Hispanics make up almost half of low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs while they represent only about 5% of native born self-employed men. This large difference, and the lower earnings among Hispanic business owners, explains essentially the entire native-immigrant self-employment earnings gap. Although of less consequence for the wage/salary native-immigrant earnings gap, the ethnic compositional difference is the most important factor in this sector too. Native-immigrant differences in schooling, hours work per week and experience also contribute to the observed lower earnings among immigrants. Overall, differences in the observable characteristics contribute to about 4/5 of the native-immigrant earnings gap, both among self-employed and wage/salary men.

Although the earnings of self-employed immigrant women is on par with the earnings of native born female business owners, the earnings decomposition analysis suggests that female immigrant entrepreneurs are more likely to reside in states with lower self-employment earnings and that once this is factored in, their predicted earnings is somewhat higher than those of observationally similar native born business owners. The native-immigrant earnings gap among female wage/salary employees can be explained primarily by differences in factors such as experience, education and ethnic composition.

Overall, the data and our analyses indicate that most low-skilled business owners have lower earnings than those of workers in the wage/salary sector. However, the analyses so far have not looked at possible differences in earnings growth across both sectors and groups. We next address this issue, as well as unobserved individual heterogeneity.

To account for individuals’ differences in important time invariant unobservable earnings related factors, such as innate ability and motivation, we also estimate individual fixed effects model specifications. In these specifications, we do not include lagged labor force status, since it is time invariant for certain sub-groups, including all individuals who stayed in business or remained in the same job for the full sample period. We do however include controls for hours worked per week.Footnote 7 Lastly, year fixed effects are included to control for macroeconomic changes.

We use two alternative fixed effects approaches to analyze earnings growth; one with an emphasis on changes in earnings with respect to age and the other with respect to the role of years in business or years at current job.Footnote 8 We interact these variables with self-employment status but do not include an uninteracted self-employment dummy.Footnote 9 This approach has the advantage that identification does not require change in self-employment status while still accounting for unobservable individual heterogeneity.

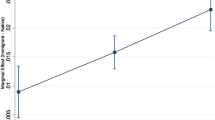

The earnings growth estimates with respect to age, presented in the top panel of Table 6, do not reveal evidence of differences in earnings growth between immigrant low-skilled business owners and employees, neither for men nor women. The interaction (age with self-employment) coefficients are not significant at traditional significance levels. However, the estimates do point to some differences across sectors among natives, although it is difficult to determine whether these differences imply lower or greater earnings growth. To assess this, we used the fixed effects estimates and generated predicted age-earnings profiles, shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Among native men, Fig. 2 reveals a slight decline in the self-employment earnings disadvantage over the work life, by approximately 10% points from age 25 to age 50. Low-skilled native born female entrepreneurs are predicted to reduce the earnings gap substantially over the same age range but are not predicted to catch-up with their wage/salary counterparts (Fig. 3).Footnote 10

The predicted log annual earnings are generated from the fixed effects estimates presented in the top panel of Table 6

The predicted log annual earnings are generated from the fixed effects estimates presented in the top panel of Table 6

We also explore the following earnings scenario of two hypothetical individuals in each group—one who just started her/his own business and the other who instead of entering self-employment started a new job in the wage/salary sector. We again rely on the fixed effects specification but in place of age variables we utilize years of owning the current business and years at current job. The results are shown in the bottom panel of Table 6. With the exception of immigrant women, the estimates indicate that the earnings of low-skilled entrepreneurs follow a different trajectory, with respect to firm or business specific experience, than the earnings of low-skilled wage/salary workers. Again, we use the estimates to generate earnings predictions, and plot the estimates over time. Since the focus is on earnings growth, we assume that business owners and traditional employees start out at the same earnings level.

Figure 4 indicate initially slower earnings growth for self-employed men but also that earnings increase somewhat faster in the subsequent years. The estimates suggest roughly equal earnings after about 14–15 years among immigrant men but no convergence within 15 years among native born men. Figure 5 indicates a similar relationship for low-skilled native women, who also experience a steeper earnings trajectory, after having experienced slower growth during the first few years in business. The figure also suggests that self-employed immigrant women experience slower earnings growth than employees. However, it is important to note that the estimates in Table 6 fail to reject equal earnings trajectories between female immigrant entrepreneurs and employees. We also note that the earnings growth analysis with respect to experience understate the self-employment earnings gap since we assume, for ease of exposition, the same starting point—an assumption the data do not support. For example, our data reveals that low-skilled self-employed women have 36 and 22% lower mean annual earnings, natives and immigrant, respectively, in their first year in business compared to observationally similar women in their first year at a wage/salary job.Footnote 11

The predicted log annual earnings are generated from the fixed effects estimates presented in the bottom panel of Table 6

The predicted log annual earnings are generated from the fixed effects estimates presented in the bottom panel of Table 6

Lastly, we note that the earnings analysis to some extent overstates the performance of business owners since we have not applied any discounting of the returns to financial capital to our analysis. However, the typically relatively low levels of business equity among low-skilled entrepreneurs suggest that the potential upward bias of their performance is likely to be comparatively minor. Our analysis using our business equity adjusted earnings measure supports the latter but also indicates a relatively less favorable comparison for the self-employed.Footnote 12

6 Summary and conclusions

There are more business owners in the US who have no education beyond high school 6.9 million, than there are self-employed college graduates, 5.6 million. Immigrants play a particularly important role among these less educated entrepreneurs and in fact, the entire net growth in low-skilled self-employment from 1980 to 2007 stems from immigration (Lofstrom 2009). Furthermore, more than half of the immigrant population in the US are low-skilled (defined here to be individuals with no formal education beyond high school) and are hence particularly likely to face limited labor market opportunities in the increasingly skill intensive US economy.Footnote 13 The ability of the large group of low-skilled immigrants to successfully integrate into the US economy is clearly of importance.

This paper addresses the research question of how well do low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs do in the US labor market. To answer this question we compare the annual earnings of foreign born business owners to the annual earnings of immigrants in wage/salary employment as well as native born entrepreneurs. The research shows that the answer depends on who low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs are compared to and the time horizon.

The analysis reveals that although top earning immigrant low-skilled entrepreneurs earn more than top earning immigrant employees, wage/salary employment is a more rewarding option for most low-skilled workers, regardless of gender. When compared to observationally similar foreign born workers in wage/salary employment, self-employed immigrants have substantially lower earnings. Our results show that this is also true for native born low-skilled workers.

Our individual fixed effects estimates of earnings growth reveal that the long-run financial gains to low-skilled self-employment are relatively high for immigrant men, who are found to have higher earnings growth than foreign born wage/salary earners. The estimates indicate that after about 14–15 years in business, their earnings are roughly at the level of wage/salary workers. The catch-up with wage/salary workers appears to be somewhat faster among immigrant men compared to native business owners.

Compared to observationally similar native born male business owners, immigrant entrepreneurs have slightly lower annual earnings. The observed low-skilled native-immigrant self-employment earnings gap of about 20% among men can be explained almost entirely by native-immigrant differences in the ethnic composition of business owners, close to 50% of low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs are Hispanic while only about 5% of self-employed natives are Hispanic.

Low-skilled female immigrant entrepreneurs do as well as self-employed native females. In fact, once native-immigrant differences in observable factors are accounted for, the results indicate that their earnings are slightly higher, albeit statistically insignificantly so. The earnings growth estimates indicate, however, that the earnings of female native entrepreneurs may grow faster than the earnings of self-employed immigrant women.

Although our results indicate that earnings growth is possibly greater among low-skilled self-employed immigrant men (compared to foreign born workers in wage/salary employment) is consistent with self-employment being a tool that increases low-skilled immigrant economic integration, the estimates also indicate a weaker relationship between increased earnings and years since immigration among foreign born business owners. The lack of strong evidence of relative success among low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs suggests that previous finding of greater labor market assimilation among self-employed immigrants is driven by the relative success of the comparatively higher skilled immigrant entrepreneurs. Lastly but importantly, in spite of the limited evidence of low-skilled entrepreneurial success, the results indicate that the, admittedly low, returns to self-employment are higher among low-skilled immigrants than it is among low-skilled natives.

Overall, the results suggest that self-employment among low-skilled immigrant, and native, workers is not a particularly financially rewarding option. Policies and efforts aimed at increasing the business ownership rates of low-skilled workers are likely to be relatively ineffective ways to increase the economic well being among low-skilled workers. The relative lack of success among low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs is probably not due to start-up barriers, such as limited availability of start-up capital. Previous research does not find evidence of binding capital constraints for self-employment entry into low-barrier industries, the industries most relevant to low-skilled individuals (Lofstrom and Wang 2009). The difficulties of successfully encouraging low-skilled entrepreneurship is also evident in the body of research which finds that less skilled business owners face significant difficulties staying in business and that micro loan programs aimed at disadvantaged groups are ineffective (e.g. Bates 1990; Servon and Bates 1998 and Shane 2009). Instead, policies aimed at increasing human capital, such as formal schooling, vocational training or English courses, of low-skilled workers are more likely to achieve a policy objective of improving the economic well being of workers in this challenging segment of the skill distribution.

Notes

We use the terms self-employed, entrepreneur and business owner synonymously.

The self-employment trends are generated using the 1980, 1990, and 2000 US Census 5% Public Use Microdata Samples (PUMS) and the 2005, 2006, and 2007 American Community Survey (ACS). The sample is restricted to individuals between the ages of 16 and 67. In these data, individuals are defined to be self-employed if they report, in the class of worker question, being self-employed in an incorporated or not-incorporated establishment.

The data, and the sample utilized here, are described in more detail in Lofstrom (2009). Although the 2004 Panel was originally set to have 12 waves with a full set of topical modules, due to budget constraints, the topical modules were not collected for waves 9–12. Furthermore, the sample was cut by half for this time period.

It is also possible to include additional controls for variables that may change over time, such as family composition and geographic location. However, the estimated coefficient of these variables are unlikely to represent causal impacts since they are identified through variation in the arguably selective sub-sample for whom these variable values change. Furthermore, including these variables do not appreciably affect the years in business or job parameters. Hence, we opted for presenting the results for the more parsimonious specification.

We explored both linear and quadratic functional forms of years since migration and found similar weak relationships.

Including other potentially time varying factors, such as education and marital status, does not appreciably affect the estimated earnings differences between low-skilled entrepreneurs and wage/salary workers.

For each group we performed F-tests to determine the appropriate functional form of earnings growth. The best fits appear to uniformly be a third order degree polynomial.

One possibility is to utilize a fixed effects specification including a simple self-employment dummy variable to capture the earnings gap. A potential short coming of this approach is that the self-employment parameter of interest is entirely identified off individuals who are observed entering or exiting self-employment over the 3–4 year sample period. It is possible that this selective sub-sample is not representative of low-skilled entrepreneurs in general, and hence the approach not yielding unbiased estimates of the earnings differences.

The results are not included but are available upon request from the author.

Author’s calculation using the 2007 American Community Survey show that approximately 53% of immigrants in the US labor force have no post-secondary education.

References

Bates, T. (1990). Entrepreneur human capital inputs and small business longevity. Review of Economics and Statistics, 72(4), 551–559.

Brock, W. A., & Evans, D. S. (1986). The economics of small businesses: Their role and regulation in the U.S. economy. New York: Holmes and Meier.

Cummings, S. (1980). Self-help in urban America: Patterns of minority business enterprise. New York: Kenikart Press.

Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1989). Some empirical aspects of entrepreneurship. American Economic Review, 79, 519–535.

Fairlie, R. W. (2004). Earnings growth among less-educated business owners. Industrial Relations, 43(3), 634–659.

Fairlie, R. W. (2005). Entrepreneurship and earnings among young adults from disadvantaged families. Small Business Economics, 25(3), 223–236.

Hamilton, B. H. (2000). Does entrepreneurship pay? An empirical analysis of the returns of self-employment. The Journal of Political Economy, 108(3), 604–631.

Holtz-Eakin, D., Rosen, H. S., & Weathers, R. (2000). Horatio Alger meets the mobility tables. Small Business Economics, 14, 243–274.

Lofstrom, M. (2002). Labor market assimilation and the self-employment decision of immigrant entrepreneurs. Journal of Population Economics, 15(1), 83–114.

Lofstrom, M. (2009). Does self-employment increase the economic well-being of low-skilled workers? IZA Discussion Paper No 4539, October.

Lofstrom, M., & Bates, T. (2009). Latina entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, 33(4), 427–439.

Lofstrom, M., & Wang, C. (2009). Mexican-American self-employment: A dynamic analysis of business ownership. Research in Labor Economics, 29, 197–227.

Rees, H., & Shah, A. (1986). An empirical analysis of self-employment in the U.K. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 1, 95–108.

Servon, L., & Bates, T. (1998). Microenterprise as an exit route from poverty. Journal of Urban Affairs, 20, 419–441.

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33, 141–149.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lofstrom, M. Low-skilled immigrant entrepreneurship. Rev Econ Household 9, 25–44 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-010-9106-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-010-9106-1