Abstract

A widely shared intuition holds that individual control over money matters for the decision process within the household and the subsequent distribution of resources and welfare. As a consequence, there are good reasons to depart from the unitary model of the household and to explore the possibilities offered by models of the family accounting for several decision makers in the household and for the potential impact of tax reforms on the balance of power. This paper summarizes both the methodological and empirical findings presented in the next three papers of this special issue of the Review of the Economics of the Household. This series of contributions primarily entails a concrete comparison of the policy implications of the choice between the unitary and a particular multi-person representation: the collective representation. On the one hand, it suggests a methodology to implement the collective model of labor supply in a realistic context where participation is modeled together with working hours, and where the full tax-benefit system is accounted for. On the other hand, the empirical part relies on comprehensive simulations of tax reforms in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom, and allows to quantify the distortions that may affect policy recommendations based on the unitary model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1. Introduction

A widely shared intuition holds that individual control over money matters for the decision process within the household and the subsequent distribution of resources and welfare. This naturally extends to sources of income such as public transfers and raises the question of the identity of the recipient of family transfers. A clear illustration is given by the recent debates surrounding the design of family benefits and the Working Families’ Tax Credit (WFTC) in the UK.

Typically, the standard model of household behavior, the unitary model, is incapable of providing an answer to this kind of issue since it assumes that households, irrespective of the number of household members, behave as single decision-makers. In recent years, the appeal for more general models of the family, taking into account several decision makers and the bargaining process, has been very strong. In particular, the collective model introduced by Chiappori (1988, 1992) and Apps and Rees (1988) does not only improve our capacity to analyze the impact of economic policy at the individual level, it also respects a fundamental methodological principle, individualism, while the unitary model does not.

The present paper is an introduction to a series of three studies which target precisely the relevance of the unitary and collective approaches and present an analysis of tax-benefit reforms for several countries. The analysis focuses on reforms which do not only change household budget constraints but also the balance of power within families.

This series of papers originates from a one-year project conducted in 2001 for the Directorate General for Employment and Social Affairs of the European Union (Laisney, 2002). The goal of the project was to provide a comparative study of tax-benefit systems for Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom with a particular focus on the possible impact of the reforms on household labor supply of women and men and, most importantly, on the within-family distribution of wealth and welfare. In particular, the project aimed to provide a comparison of the policy implications of the choice between the standard model (the unitary representation) and a more general multi-utility framework (the collective representation). The project has brought some interesting results that are summarized here. On the one hand, it suggests a methodology to implement the collective model of labor supply in a realistic context where participation in the labor market and working hours are modeled together, and where a stylized version of the full tax-benefit is accounted for. On the other hand, the empirical part relies on comprehensive simulations that exploit the heterogeneity available in microdata and replicates the exercise on several countries with different tax-benefit legislations, thus providing an informal robustness test of the results. The simulations allow to quantify distortions that may affect policy recommendations based on the unitary model for actual or topical reforms.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the recent literature on models of the household and their relevance for policy analysis. Section 3 provides an overview of the project’s contribution. Section 4 concludes.

2. Household modeling for policy analysis

In this section we first survey the recent literature on models of intrahousehold allocation (Section 2.1) and then discuss their implications for policy analysis (Section 2.2).

2.1. Models of the household: an overview

In the standard approach, the household is generally assumed to maximize a single utility function, which implies the existence of a dictatorship or common preferences (pure consensus) within multi-person households. The appeal of the ‘unitary’ approach is that it allows the derivation of testable restrictions on household behavior from the standard theory of consumer demand, as well as the complete identification of household preferences. Thus, the model provides the opportunity to study the effects of policies on household behavior and welfare in a straightforward way. However, one of the major problems of the approach is that some of the theoretical implications of the model—symmetry and negative semi-definiteness of the Slutsky matrix—turn out to be most often rejected when tested on couples (see e.g. Blundell, 1988, for an overview). The income pooling assumption—crucially related to the role of public transfers on intrahousehold distribution—is also rejected in many studies. Footnote 1 Moreover, it is natural to think that the ultimate unit of concern for policy makers is the individual.

More general models of the household that explicitly recognize the presence of several decision makers are gradually gaining ground in the applied microeconomic literature. Early studies have introduced individual preferences in the modeling of household behavior. Samuelson (1956) suggests that the household can be represented as an entity maximizing a (household) social welfare function; however, the idea relies on restrictive hypotheses. In a similar way, Becker (1974) identifies the household with a benevolent parent maximizing the egoistic utilities of the other members. Here too, some problems exist (see Bergstrom, 1989, for a critical discussion). Footnote 2 Nonetheless, these seminal papers provide a framework to think about interactions within the household. Most importantly, by recognizing each individual as a separate decision-maker both before and during marriage, Becker’s economic theory of marriage (Becker, 1965, 1973, 1991) is at the origin of all the recent models of individual decision-making within the family (see Ott, 1998, for an overview and a critique).

Several alternatives to the unitary model have been proposed, all explicitly accounting for the existence of several decision makers with possibly different preferences. One broad class of models represents multi-person household behavior in a non-cooperative framework. Footnote 3 While some of the models neglect the household environment, early contributions inspired by the Demand and Supply models of the marriage market introduced by Becker (1973) (e.g. Grossbard-Shechtman, 1984; Grossbard-Shechtman & Neuman, 1988) acknowledge the fact that bargaining power matters when studying the behavior of individual household members and is related to relative incomes and conditions on the marriage market surrounding each individual.

However, a potential drawback of non-cooperative models is that intrahousehold allocations are not necessarily Pareto-efficient. Yet, since it is reasonable to expect that spouses know each other’s preferences well, it is plausible that they exploit the gains from cooperation during the long-term relationship they maintain while living as a couple. Footnote 4 Efficiency then finds game-theoretic support (Folk theorem) and appears as a natural extension of the unitary setting. Some models in this vein focus on efficient intrahousehold outcomes by making use of explicit axiomatic bargaining solutions, e.g. Nash bargaining, and the specification of fall-back options for each individual in the household. While early studies assume that threat points correspond to the situation after separation (Manser & Brown, 1980; McElroy & Horney, 1981), more recent contributions tend to favor non-cooperative equilibria (e.g., Haddad & Kanbur, 1994; Konrad & Lommerud, 2000; Lundberg & Pollak, 1993).

In contrast, the collective approach introduced by Chiappori (1988, 1992) and Apps and Rees (1988) makes no structural hypothesis on the form of the interactions between household members, apart from assuming that they lead to efficiency. In this way, it nests both the unitary approach and all cooperative models leading to efficient outcomes. Yet, Slutsky symmetry and negativity are no longer satisfied (see Browning & Chiappori, 1998). The recent literature on collective models has focused primarily on the derivation of new testable restrictions on observable behavior. Several studies have found that the collective restrictions are not rejected by data on couples, while the unitary restrictions often are. Footnote 5

The efficiency assumption means that household members will always be on the Pareto frontier in the utility space. An important aspect of the collective approach is that the final location on this frontier may depend on partners’ relative wages, nonlabor incomes and ‘distribution factors’ that influence the balance of power between spouses and the subsequent intrahousehold distribution of wealth and welfare. Distribution factors are socio-economic variables that may influence the bargaining conditions but do not influence directly either individual preferences or the budget constraint (see Bourguignon, Browning, & Chiappori, 1995). They are referred to as “extra-household environmental parameters” by McElroy (1990). Examples of such variables in recent applications are the sex ratio (defined as the proportion of females in the working age population), or an index measuring the extent to which divorce laws favor the wife (see Chiappori et al., 2002). In the collective model, variables such as wages, unearned incomes and distribution factors enter in an unrestricted way through the reduced form of the negotiation output. Footnote 6 In cooperative bargaining models, their influence may depend on the precise specification of the threat points. In multi-person household models incorporating the marriage market, such as Grossbard-Shechtman (1984), wages, incomes, and marriage market conditions influence the negotiated value of individual household production time and hence individual outcomes.

Discussions and surveys of the different models mentioned above can be found in Bourguignon and Chiappori (1992), Bergstrom (1996), Chiappori (1997), Chiuri (2000), Vermeulen (2002a) and in the introduction of Grossbard-Shechtman (2003). The most recent and comprehensive survey on modeling issues is provided (in French) by Chiappori and Donni (2006), while Lundberg (2005) provides an enlightening discussion on the evolution of family economics. Lundberg and Pollak (1996), Behrman (1997) and Strauss, Mwabu and Beegle (2000) also discuss non-unitary models, focusing specifically on the issue of intrahousehold allocation of resources. A clear definition of the collective approach can be found in Donni (2007).

2.2. Tax policies and household bargaining

The primary motivation of the project described in this special issue is to analyze how policies may affect the household decision process and the welfare of individuals within families.

The collective model has raised considerable attention over the recent years. However, its implementation for policy analysis remains a serious challenge. Some attempts have been made to identify the structure of the model on the basis of information typically available in general purpose survey data. In most previous studies, the identification of a collective model of labor supply usually relies on three crucial assumptions: (i) separable preferences (either egoistic or caring à la Becker) allowing the decentralization or ‘sharing rule’ interpretation of the model, (ii) no taxation, and (iii) no corner solutions. Extensions to account for public goods (see Blundell, Chiappori, & Meghir, 2005), as well as issues surrounding domestic production have been recently suggested. Footnote 7 As far as the three assumptions above are concerned, tests and identification results have been obtained when nonlinear taxation is introduced (see Donni, 2003, and Beninger, 2000, for the theory, and Nicolas Moreau and Olivier Donni, 2002, for estimation on French data), or when participation decisions are modeled together with the choice of working hours (see Blundell, Chiappori, Magnac, & Meghir, 2001; Donni, 2003, for participation issues in a framework without taxation). However, the general case when both taxation and participation decisions are incorporated has not yet received proper treatment; in addition, in many countries, realistic simulations of tax-benefit systems must cope with nonconvex budget sets due to the means-test of social assistance and family transfers. Footnote 8 One of the objectives of the project summarized here is to provide a way to overcome these difficulties in a consistent manner that can be reproduced over several European countries characterized by complex tax-benefit systems (and actually nonconvex budget sets).

Another issue worth mentioning is that in models relying solely on the efficiency assumption the sharing rule has no explicit form, i.e. it appears only as a reduced form. This approach can be characterized as ‘semi-structural’. As a consequence, there is hardly any guidance concerning the factors that could affect negotiation (see Browning & Lechene, 2001; Browning, Chiappori, & Lechene, 2005) and, in particular, the way taxation could come into play. This is an additional difficulty for analyzing the intrahousehold effects of tax policies, which has become apparent in the course of the present project. In Vermeulen et al. (2006), we introduce taxation through the relative potential contribution of each spouse to household disposable income, in a way which may appear somewhat ad hoc. More structural models—i.e. specifying the cooperative bargaining process and the outside options—could be used to alleviate this problem and characterize in better ways the specific impact of tax-benefit reforms on the negotiation rule. However, the choice of a given type of threat point, that completely determines the nature of policy recommendations using these models, can be very arbitrary as well. For instance, in a cooperative model relying on divorce threat points, the change in the identity of the recipient of child benefits (e.g. a ‘wallet to purse’ type of reform) should not have any influence on the outcomes. Footnote 9 In contrast, this type of reform will affect the household decision process in cooperative models where income pooling does not hold, for instance when fall-back options correspond to a non-cooperative marriage with corner solutions. This is typically the case of the separate spheres model of Lundberg and Pollak (1993) where each spouse is dedicated to a gender-specific activity determined by tradition. Footnote 10

In theory, both aspects of the situation when divorced (including tax-benefit rules for single individuals and single parents) and when married (including tax-benefit rules for couples) could be included in the reduced form sharing rule of collective models; in practice, serious identification issues may arise so that a trade-off between using collective and fully structural models still exists. In the following, we will abstract from these issues and will focus on the implementation of a collective model where tax-benefit rules for couples matter in both the budget constraint and the determination of the bargaining process. Note finally that even though aspects surrounding divorce (e.g. legislation) may affect the outcome of collective models, as described above, household formation or dissolution as such is not modeled in this approach. This would require not only more structure but also the modeling of the marriage market (see, e.g., Grossbard-Shechtman & Keeley, 1993, in a non-cooperative setting, and Del Boca & Flinn, 2005, in a cooperative framework).

3. Main contributions

3.1. Implementation of a collective model with taxation and participation

The first contribution of this project is to suggest a way to simulate labor supply using a collective model with taxation and participation decisions. This is the topic of Vermeulen et al. (2006), a methodological paper whose suggested approach is used in the following papers, Myck et al. (2006) and Beninger et al. (2006).

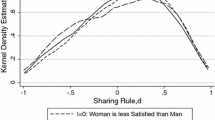

The collective model assumes that household allocations are Pareto efficient. A first idea would be to describe the bargaining position of the spouses by searching for the convex combination of the spouses’ utility functions that would rationalize household choices as maximizing that combination. But in the presence of nonconvex budget sets (typically resulting from interactions between fiscal and social benefit systems), the utility possibility set can be nonconvex, thus defeating the proposed strategy. Footnote 11 The present approach, which is used for the first time in the empirical literature, maps the complete Pareto frontier for each household, and proposes different measures of the final location on the frontier that are interpreted as the bargaining position of the spouses or power index. Footnote 12 The identification is achieved by two routes. First, some preference parameters, which are assumed to be common to singles and households, are estimated separately on a sample of singles. Second, the power index and marriage-specific preference parameters are calibrated on observed labor supplies of men and women in a sample of couples. The calibrated power index is finally regressed on relevant bargaining factors, including a set of variables retracing the potential relative contributions of the spouses to household disposable income (i.e. income after social contributions, taxes and benefits).

In its capacity to handle nonconvex budget sets and labor force participation decisions of both spouses, this model offers a unique chance to simulate labor supply responses to tax-benefit reforms which affect not only the budget constraints but also the balance of power in the household (Myck et al., 2006). The model also suggests the following exercise to compare unitary and collective representations. First, the estimated and calibrated collective model is used to generate a ‘collective’ baseline dataset. Second, a unitary model is estimated on this data. Finally, differences in the predictions are interpreted as distortions attributed to the unitary model when the ‘true’ behavior is assumed to be collective (Beninger et al., 2006).

3.2. Analysis of tax-benefit reforms

The second paper, Myck et al. (2006) illustrates the two main advantages of collective models for tax reform analysis. The first one is their ability to produce results at the individual level rather than simply at the household level, which enables the analyst to obtain results in terms of intrahousehold redistributions. The second is their ability to map effects of reforms for which the unitary model predicts no reaction whatsoever, like reforms which pertain only to the identity of the beneficiary of a benefit within the household. In this respect, the paper presents the results of simulations of the introduction of the WFTC in the UK, a tax credit to families with children which can be paid alternatively to the main carer (more frequently the wife) or to the main earner (more frequently the husband). The paper focuses on the UK but also summarizes results obtained for other countries and other tax-benefit reforms. Footnote 13

The methodology described in Vermeulen et al. (2006) is used to calibrate the collective model. As indicated before, the power index is regressed on a set of variables including the relative financial contribution of wife and husband in household disposable income. In particular, one of the variables aims to capture the difference between giving the WFTC to the main carer versus giving it to the main earner.

Findings suggest that the identity of the recipient of the transfer does matter. Although whether the WFTC is paid to the mother or to the father does not change the household budget constraint, the collective framework shows significant differences in behavioral responses between these two forms of the reform and substantial differences in the normative impact of the reform in terms of individual welfare analysis. Results are confirmed for other countries when reforms which affect simultaneously the household budget constraint and the intrahousehold distribution are implemented.

3.3. Comparing household representations

The third paper in this issue, Beninger et al. (2006), compares the performance of the unitary and the collective representations in an exercise that focuses on German data and the introduction of linear taxation in Germany, with a summary of results obtained for other countries and other reforms.

The strategy consists of assessing the size of the distortions entailed by the use of a unitary model in tax reform analysis when ‘true’ behavior is collective. More precisely, the collective model implemented in Vermeulen et al. (2006) is used for two purposes: to generate labor supplies consistent with the collective rationality—the ‘collective’ baseline—and to obtain the ‘collective’ predictions to a reform. Then, a unitary model is estimated on ‘collective’ data and used to predict responses to the reform. In this way, we can gauge the discrepancies due to the unitary assumption when assessing the labor supply response to a tax reform, and the subsequent impact on individual welfare. Footnote 14

The analysis assumes that households behave collectively, so that post-tax reform predictions from the collective model can be considered as ‘true’ responses, whereas the predictions from the unitary model are what the traditional literature can tell about household behavior in this situation. This approach can be related to a model choice procedure in the spirit of Cox (1962). Instead, one could wonder what a collective model predicts when estimated on ‘unitary data’ (generated by a unitary model). The asymmetry is justified at least for two reasons: (i) there exists no example of an estimation of a general collective model yet, and (ii) unitary restrictions have been rejected in several studies. Moreover, we agree with Alderman, Chiappori, Haddad, Hoddinott, and Kanbur (1995) that it is time to shift the burden of the proof.

The construction of collective data and the estimation of a unitary model for comparison purposes have been conducted on Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. For each country, a national dataset was used and common as well as country-specific tax reforms were simulated. The repetition of the experience for six countries provides an informal robustness test for the exercise described above.

The general conclusion is that distortions due to the use of a unitary model turn out to be important for the design of tax revenue neutral reforms and for predictions of labor supply adjustments and the welfare implications of a reform. Unitary and collective models cannot be used indiscriminately when formulating policy recommendations. This justifies putting more effort into the identification and estimation of multi-person household models, such as the collective model, in realistic settings (taxation, participation, etc.).

4. Conclusions

The project has demonstrated anew the relevance of multi-person models such as the collective model, and pointed to new directions for the estimation of such models in much more realistic situations than has been the case so far. The study shows that much more interesting results on the analysis of tax reforms can be obtained in a multi-person than in a unitary framework. In particular, our collective model can point to the conflicting situations that can result from economic policies.

Very understandably, the methodology presented here suffers from numerous shortcomings which are not specific to this project but reflect the limits of the current literature. A first and obvious shortcoming is that our analysis is in terms of partial rather than general equilibrium. Adjustments in prices and wages are ignored, and we assume that any person wishing to change her labor supply in any direction, even in the sense of taking up activity, is able to do so without restriction. This can only be at best a rough representation of reality. Even brushing aside this partial equilibrium aspect, we only consider fairly narrow sub-populations, and this weakens the relevance of our revenue-neutral exercises. Other difficulties concern the interpretation of leisure and the modeling of public consumption in the household. Although we have made some attempts at capturing pure leisure by taking into account minimum time requirements linked with physiological regeneration and some aspects of household production, this is not the end of the story, and more effort is clearly needed. Footnote 15 Similarly, the minimum required consumption goes some way in the direction of subsuming public goods, but at the cost of neglecting household decisions about the level of public consumption and its adjustment to new situations in prices and incomes. Concerning the measurement of the bargaining positions of the spouses, more research is clearly needed in order to obtain measures that do not hinge on a particular cardinal representation of the individual preferences, and to improve the identification of the way in which the bargaining position of the spouses depends on various aspects of the tax-benefit system.

In future research, efforts are needed in several directions. One is the exploitation of time use surveys, possibly in combination with general household surveys, towards the investigation of household production models within the collective framework. Another direction that would lead to a more realistic modeling should be combining the collective model with approaches explicitly taking into account the employability of low productivity workers in connection with minimum wage regulations (see e.g. Laroque & Salanié, 2002) or restrictions on hours coming from the demand side. But the most obvious immediate direction will be the investigation of the possibility of one-shot econometric estimation of collective models with nonparticipation and taxation opened up by this study (instead of the piecemeal mix of estimation and calibration discussed here). A seemingly attractive path would be to resort to Bayesian methods, which would allow to translate information on singles’ preference parameters into prior distributions on some of the preference parameters of individuals in couples. Another path would be to resort to indirect inference (Dridi & Renault, 2000; Gouriéroux, Monfort, & Renault, 1993), i.e. to formulate an approximation of the complete model, and obtain estimates for the parameter vector of the complete model by minimizing the discrepancy between the estimates obtained from the approximate model on the original data and on data simulated with the complete model.

Notes

The share of individual income in total household unearned income usually has a significant impact on household decisions. See, among others, Behrman (1988), Thomas (1990, 1992), Schultz (1990) or Lechene and Attanasio (2002). The well-known evidence of Lundberg, Pollak and Wales (1997) also shows that a ‘wallet to purse’ reform in the UK in the 1970s has significantly affected consumption patterns.

Since these early models still respect symmetry and negative semi-definiteness of the Slutsky matrix, they are usually classified as unitary models.

Strictly speaking, this statement applies to a nonparametric version of the model. In practice, a rather restrictive functional form is often used and adds (possibly undesirable) constraints on the form of the underlying negotiation process.

See theoretical contributions by Apps and Rees (1997), Chiappori (1997) and Rapoport, Sofer, and Solaz (2003) on domestic production, and Bourguignon (1999) and Blundell, Chiappori, and Meghir (2005) on the presence of children. See also some estimations by Chiuri (1999), Couprie (2003), Rapoport, Sofer, and Solaz (2003, 2006) and Bourguignon and Chiuri (2005), and an important generalization in Donni (2005).

In Moreau and Donni (2002), for instance, male and female labor supplies were estimated on two-earner couples, ignoring participation decisions and convexifying the budget set.

This case is nonetheless interesting since it allows to study the impact of policies which affect individuals in case of divorce. For instance, social benefits targeted to single mothers, such as the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) in the US, may affect fall-back options of married women with children and the probability of divorce. As a matter of fact, Rubalcava and Thomas (2000) find that variations in AFDC levels over time and across US states directly affect the bargaining position of married mothers with low incomes, and subsequently household decisions on consumption and time allocation. In the spirit of the present project, Bargain and Moreau (2005) simulate a Nash bargaining model with divorce threat points in order to investigate the incidence of such reforms.

One could argue that relevant threat points depend ultimately on empirical evidence. Some studies emphasize both the role of divorce (and related marriage market issues)—see Gray (1998), Chiappori et al. (2002), Moreau and Donni (2002), Grossbard-Shechtman and Neuman (2003), and Wolfers (2005) among others—and the possible role of non-cooperative situations on intrahousehold decisions. Bergstrom (1996) reconciles both approaches in a model drawing on noncooperative foundations of bargaining models (à la Rubinstein-Binmore), where noncooperation is an intermediary threat and divorce is the ultimate threat.

A possibility, however, is to suggest that non-convex parts of the utility set are not attained by households when they are assumed to play mixed strategies. In this case, it is possible to model household decisions as the maximization of a household welfare function; see Bargain and Moreau (2002). Tax policy analysis is performed by Vermeulen (2004) using an estimation of a collective model of female labor supply. Both papers still rely on estimations on single individuals to complete identification.

This approach relies implicitly on cardinality assumptions. As suggested by Van Praag (1994), this branch of research should ultimately resort to richer data than those which can be derived from the observation of demand behavior.

Complete results for each country and a number of different tax reforms are available in Vermeulen (2002b, Belgium), Bargain, Beninger, Laisney, and Moreau (2002, France), Beninger, Beblo, and Laisney (2002, Germany), Chiuri and Longobardi (2002, Italy), Carrasco and Ruiz-Castillo (2002, Spain), and Blundell, Lechene, and Myck (2002, UK).

This strategy originates from Beninger and Laisney (2002) who present insights on the basis of purely synthetic data. The present project extends their work to real data.

On the importance of properly identifying pure leisure, see e.g. Apps (2003).

References

Alderman, H., Chiappori, P., Haddad, L., Hoddinott, J., & Kanbur, R. (1995). Unitary versus collective models of the household: Is it time to shift the burden of the proof? World Bank Research Observer, 10, 1–19.

Apps, P. (2003). Gender, time use and models of the household. IZA Discussion Paper. Bonn: IZA 796.

Apps, P., & Rees, Ray. (1988). Taxation and the Household. Journal of Public Economics, 35, 355–369.

Apps, P., & Rees, R. (1997). Collective labor supply and household production. Journal of Political Economy, 105, 178–190 (Comments).

Ashworth, J., & Ulph, D. (1981). Household models. In B. Charles (Ed.), Taxation and labour supply (pp. 117–133). London: Allen and Unwin.

Bargain, O., & Moreau, N. (2002). Is the collective model of labor supply useful for tax policy analysis? A simulation exercise. DELTA Working Paper 21, Paris: DELTA.

Bargain, O., & Moreau, N. (2005). Cooperative models in action: Simulation of a Nash-bargaining model of household labor supply with taxation. IZA Discussion Paper 1480. Bonn: IZA.

Bargain, O., Beninger, D., Laisney, F., & Moreau, N. (2002). Positive and normative analysis of tax policy: Does the representation of the household decision process Matter? Evidence for France. Paper presented at the EEA’02 meeting in Venice.

Becker, G. (1965). A theory of the allocation of time. Economic Journal, 75, 493–517.

Becker, G. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Becker, G. (1974). A theory of social interactions. Journal of Political Economy, 82, 1063–1093.

Becker, G. (1991). A treatise on the family, enlarged edition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Behrman, J. (1988). Intrahousehold allocation of nutrients in rural india: Are boys favoured? Do parents exhibit inequality aversion? Oxford Economic Papers, 40, 32–54.

Behrman, J. (1997). Intrahousehold distribution and the family. In M. Rosenzweig & O. Stark (Eds.), Handbook of population and family economics (pp. 125–187). Vol. 1A, Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Beninger, D. (2000). Collective models: Introduction of the taxation. Mimeo. Mannheim: ZEW.

Beninger, D., & Laisney, F. (2002). Comparison between unitary and collective models of household labor supply with taxation. ZEW Discussion Paper 02-65. Mannheim: ZEW.

Beninger, D., Beblo, M., & Laisney, F. (2002). Welfare analysis of fiscal reforms: Does the representation of the family decision process matter? Evidence for Germany. Mimeo. Mannheim: ZEW.

Beninger, D., Bargain, O., Beblo, M., Blundell, R., Carrasco, R., Chiuri, M., Laisney, F., Lechene, V., Longobardi, E., Myck, M., Moreau, N., Ruiz-Castillo, J., & Vermeulen, F. (2006). Evaluating the move to a linear tax system in Germany and other European countries: The choice of the representation of household decision processes does matter. Review of Economics of the Household, 4, 159–180.

Bergstrom, T. (1989). A fresh look at the rotten-kid theorem and other household mysteries. Journal of Political Economy, 97, 1138–1159.

Bergstrom, T. (1996). Economics in a family way. Journal of Economic Literature, 34, 1903–1934.

Blundell, R. (1988). Consumer behaviour: Theory and empirical evidence—a survey. Economic Journal, 98, 16–65.

Blundell, R., Chiappori, F., & Meghir, C. (2005). Collective labor supply with children. Journal of Political Economy, 113, 1277–1306.

Blundell, R., Lechene, V., & Myck, M. (2002). Does the representation of family decision processes matter? Collective decisions and fiscal reforms in the UK. Mimeo. London: IFS.

Blundell, R., Chiappori, P., Magnac, T., & Meghir, C. (2001). Collective labour supply: Heterogeneity and nonparticipation. IFS Working Paper WP01/19. London: IFS.

Bourguignon, F. (1984). Rationalité Individuelle ou Rationalité Stratégique: Le Cas de l’Offre Familiale de Travail. Revue Économique, 1, 147–162.

Bourguignon, F. (1999). The cost of children: May the collective approach to household behavior help? Journal of Population Economics, 12, 503–521.

Bourguignon, F., & Chiappori, P. (1992). Collective models of household behavior. An introduction. European Economic Review, 36, 355–364.

Bourguignon, F., & Chiuri, M. (2005). Labor market time and home production: A new test for collective models of intra-household allocation. CSEF Working Paper 131. Bari: CSEF.

Bourguignon, F., Browning, M., & Chiappori, P. (1995). The collective approach to household behavior. DELTA-Discussion Paper 95 04. Paris: DELTA.

Browning, M., & Chiappori, P. (1998). Efficient intra-household allocations: A general characterization and empirical tests. Econometrica, 66, 1241–1278.

Browning, M., & Lechene, V. (2001). Caring and sharing: Tests between alternative models of intrahousehold allocation. Oxford Economics Discussion Paper Series 70. Oxford: University of Oxford.

Browning, M., Chiappori, P-A., & Lechene, V. (2005). Collective and unitary models: A clarification. Review of the Economics of the Household (forthcoming).

Carrasco, R., & Ruiz-Castillo, J. (2002). Does the representation of family decision process matter? A collective model of household labour supply for the evaluation of a personal tax reform in Spain. Mimeo. Madrid: Universidad Carlos III.

Chen, Z., & Woolley, F. (2001). A Cournot–Nash model of family decision making. Economic Journal, 111, 722–748.

Chiappori, P. (1988). Rational household labor supply. Econometrica, 56, 63–89.

Chiappori, P. (1992). Collective labor supply and welfare. Journal of Political Economy, 100, 437–467.

Chiappori, P. (1997). Introducing Household production in collective models of labor supply. Journal of Political Economy, 105, 191–209.

Chiappori, P., & Donni, O. (2006). Les Modèles Non-Unitaires de Comportement du Mé nage: Un Survol de la Littérature. Forthcoming in L’Actualité Économique.

Chiappori, P., Fortin, B., & Lacroix, G. (2002). Marriage market, divorce legislation and household labor supply. Journal of Political Economy, 110, 37–72.

Chiuri, M. (1999). Intrahousehold allocation of time and resources: Empirical evidence on a sample of Italian households with young children. TMR Progress Report 5. Tilburg: Tilburg University.

Chiuri, M. (2000). Individual decisions and household demand for consumption and leisure. Research in Economics, 54, 277–324.

Chiuri, M., & Longobardi, E. (2002). Welfare analysis of fiscal reforms in Europe: Does the representation of family decision processes matter? Evidence from Italy. Mimeo. Bari: University of Bari.

Couprie, H. (2003). Time allocation within the family: Welfare implications of life in couple. Mimeo. Toulouse: GREQAM.

Cox, D. (1962). Further results on tests of separate families of hypotheses. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 24B, 406–424.

Del Boca, D., & Flinn, C. (2005). Household time allocation and modes of behavior: A theory of sorts. Mimeo. New York: New York University.

Donni, O. (2003). Collective household labor Supply: Non-participation and income taxation. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 1179–1198.

Donni, O. (2005). Labor supply, home production and welfare comparisons. Mimeo. Cergy-Pontoise: University de Cergy-Pontoise.

Donni, O. (2006). Modèles d’Offre de Travail Non-Coopératifs d’Offre Familiale de Travail. L’Actualité Économique. (forthcoming)

Donni, O. (2007). Collective models of the household. In S. Durlauf & L. Blume (Eds.), The new palgrave dictionary of economics, 2nd ed. London: Palgrave McMillan (forthcoming).

Dridi, R., & Renault, É. (2000). Semi-parametric indirect inference. DP STICERD/Econometrics EM/00/392. London: London School of Economics.

Fortin, B., & Lacroix, G. (1997). A test of the neo-classical and collective models of household labor supply. Economic Journal, 107, 933–955.

Gouriéroux, C., Monfort, A., & Renault, É. (1993). Indirect inference. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 8, 85–118.

Gray, J. (1998). Divorce-law changes, household bargaining, and married women’s labor supply. American Economic Review, 88, 628–642.

Grossbard-Shechtman, A. (1984). A theory of allocation of time in markets for labor and marriage. Economic Journal, 94, 863–882.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. (Ed.). (2003). Marriage and the economy: Theory and evidence from advanced societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S., & Keeley, M. (1993). A theory of divorce and labor supply. In S. Grossbard-Shechtman (Ed.), On the economics of marriage—a theory of marriage, labor and divorce. Boulder: Westview Press.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S., & Neuman, S. (1988). Women’s labor supply and marital choice. Journal of Political Economy, 96, 1294–1302.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S., & Neuman, S. (2003). Marriage and Work for Pay. In S. Grossbard-Shechtman (Ed.), Marriage and the economy: Theory and evidence from advanced societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haddad, L., & Kanbur, R. (1994). Are better off households more unequal or less unequal. Oxford Economic Papers, 46, 445–458.

Konrad, K., & Lommerud, K. (2000). The bargaining family revisited. Canadian Journal of Economics, 33, 471–487.

Laisney, F. (Ed.). (2002). Final Report on the EU Project. Welfare analysis of fiscal and social security reforms in Europe: Does the representation of family decision processes matter? Contract No: VS/2000/0776, Written for the European Commission, DG Employment and Social Affairs. Mannheim: ZEW.

Laroque, G., & Salanié, B. (2002). Labor market institutions and employment in France. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 17, 25–48.

Lechene, V., & Attanasio, O. (2002). Tests of income pooling in household decisions. Review of Economic Dynamics, 5, 720–748.

Leuthold, J. (1968). An empirical study of formula income transfers and the work decision of the poor. Journal of Human Resources, 3, 312–323.

Lundberg, S. (2005). Men and islands: Dealing with the family in empirical labor economics. Labour Economics, 12, 591–612.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. (1993). Separate spheres bargaining and the marriage market. Journal of Political Economy, 101, 988–1010.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. (1994). Non-cooperative bargaining models of marriage. American Economic Review (Papers & Proceedings), 84, 132–137.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. (1996). Bargaining and distribution in marriage. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10, 139–158.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. (2003). Efficiency in marriage. Review of Economics of the Household, 1, 153–167.

Lundberg, S., Pollak, R., & Wales, T. (1997). Do husbands and wives pool their resources? Evidence from the UK child benefit. Journal of Human Resources, 32, 463–480.

Manser, M., & Brown, M. (1980). Marriage and household decision making: A bargaining analysis. International Economic Review, 21, 31–44.

McElroy, M. (1990). The empirical content of Nash-bargained household behavior. Journal of Human Resources, 25, 559–583.

McElroy, M., & Horney, M. (1981). Nash-bargained household decisions: Towards a generalization of the theory of demand. International Economic Review, 22, 333–349.

Moreau, N., & Donni, O. (2002). Une Estimation d’un Modèle Collectif d’Offre de Travail avec Taxation. Annales d’Économie et de Statistique, 65, 55–83.

Myck, M., Bargain, O., Beblo, M., Beninger, D., Blundell, R., Carrasco, R., Chiuri, M., Laisney, F., Lechene, V., Longobardi, E., Moreau, N., Ruiz-Castillo, J., & Vermeulen, F. (2006). Who receives the money matters: Simulating the working families’ tax credit in the UK and some European tax reforms. Review of Economics of the Household, 4, 129–158.

Ott, N. (1992). Intrafamily bargaining and household decisions. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Ott, N. (1998). Der familienökonomische Ansatz von Gary S. Becker. In I. Pies & M. Leschke (Eds.). Gary Beckers ökonomischer Imperialismus (pp. 63–90). Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr Siebeck.

Rapoport, B., Sofer, C., & Solaz, A. (2003). Household production in a collective model : Some new results. Cahiers de la MSE 03038. Université Paris 1-Panthéon-Sorbonne.

Rapoport, B., Sofer, C., & Solaz, A. (2006). La Production Domestique dans les Modèles Collectifs. L’Actualité Économique.

Rubalcava, L., & Thomas, D. (2000). Family bargaining and welfare. Mimeo. Santa Monica: RAND.

Samuelson, P. (1956). Social indifference curves. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70, 1–22.

Schultz, P. (1990). Testing the neoclassical model of family labor supply and fertility. Journal of Human Resources, 25, 599–631.

Strauss, J., Mwabu, G., & Beegle, K. (2000). Intrahousehold allocations: A review of theories and empirical evidence. Journal of African Economies, 9(AERC Supplement), 83–143.

Thomas, D. (1990). Intrahousehold resource allocation: An inferential approach. Journal of Human Resources, 25, 635–664.

Thomas, D. (1992). The distribution of income and expenditures within the household. Annales d’Économie et de Statistique, 29, 109–135.

Van Praag, B. (1994). Ordinal and cardinal utility: An integration of the two dimensions of the welfare concept. In R. Blundell, I. Preston & I. Walker (Eds.), The measurement of household welfare (pp. 86–110). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vermeulen, F. (2002a). Collective household models: Principles and main results. Journal of Economic Surveys, 16, 533–564.

Vermeulen, F. (2002b). Where does the unitary model go wrong? Simulating tax reforms by means of unitary and collective labour supply models. The case for Belgium. Mimeo. Leuven: University of Leuven.

Vermeulen, F. (2004). A collective model for female labour supply with nonparticipation and taxation. Journal of Population Economics (forthcoming).

Vermeulen, F. (2005). And the winner is ... An empirical evaluation of unitary and collective labour supply models. Empirical Economics, 30, 711–734.

Vermeulen, F., Bargain, O., Beblo, M., Beninger, D., Blundell, R., Carrasco, R., Chiuri, M.-C., Laisney, F., Lechene, V., Longobardi, E., Myck, M., Moreau, N., Ruiz-Castillo, J. (2006). Collective models of household labor supply with non-convex budget sets and non-participation: A calibration approach. Review of Economics of the Household, 4, 113–127.

Wolfers, J. (2005). Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. NBER Working Paper 10014. Cambridge-Massachusetts: NBER.

Acknowledgements

This paper exploits work done in the one-year project “Welfare analysis of fiscal and social security reforms in Europe: does the representation of family decision processes matter?” , partly financed by the EU, General Directorate Employment and Social Affairs, under grant VS/2000/0778. We are grateful for comments and advice from the Editors, anonymous referees, François Bourguignon, Martin Browning, Pierre-André Chiappori, Olivier Donni, Andreas Krüpe, Jason Lee, Ernesto Longobardi, Isabelle Maret, Costas Meghir, Nathalie Picard, Hubert Stahn, Ian Walker and Bernarda Zamora, as well as participants in conferences and seminars too numerous to be quoted here. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bargain, O., Beblo, M., Beninger, D. et al. Does the Representation of Household Behavior Matter for Welfare Analysis of Tax-benefit Policies? An Introduction. Rev Econ Household 4, 99–111 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-006-0001-8

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-006-0001-8