Abstract

We examine a recent trend in the market where investors purchase residential properties. We find that investors purchase at a discount of 9.5% compared to individuals purchasing in the same time period and geographic area. More specifically, we find that small investors purchase at a discount of 8.0%, medium investors purchase at a discount of 11.1%, large investors purchase at a discount of 13.6%, and institutional investors purchase at a discount of 7.7%. We also find that the presence of investor buyers in a market helps improve house values. A 10% increase in the percentage of houses purchased by investors in a census block leads to a 0.20% increase in house prices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

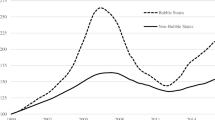

The emergence of large scale buyers in local housing markets follows the substantial decline in housing values that began in 2006 and persisted into 2012 in many markets. Entities such as New York-based Blackstone Group (NYSE: BX) and California-based American Homes 4 Rent (NYSE: AMH) and other national and local entities acquired thousands of single-family dwellings across markets particularly hard hit by the housing recession in an investment strategy presumably intended to capture cash flow from renting the dwellings to tenants and cash flow from appreciation in property value.Footnote 1

In this study, we empirically test whether investors acquire single-family dwellings at prices higher or lower than single-purchase buyers. We also test whether purchases by investor buyers lead to higher or lower prices for other dwellings in that market.

The efficient market hypothesis asserts that the price of an asset reflects all available information about its fundamental value, and the price of the asset will mirror the discounted present value of its expected cash flows. As a result, we would expect the price of an asset to be the same, regardless of whether that asset is purchased by an investor buyer or an individual buyer.

However, several factors could lead asset prices to deviate from fundamentals and to vary across different buyer types. These factors could include costly information, lack of sufficient competition, transaction costs, agency costs, and frictions in financing.Footnote 2 For example, investors may enjoy liquidity, transactional efficiencies (i.e., sophisticated targeting of potential acquisition properties, cash purchases, superior negotiation skills and experience, streamlined closings, etc.), and operational efficiencies (i.e., property and portfolio management expertise) in local housing markets that consumers in those markets may not have. Investors may also enjoy some monopsony advantage during distressed times and might be able to utilize their buyer power and negotiation skills to purchase properties at a discount to market value. On the other hand, purchases by investors would increase the overall demand in the market, deplete inventory of distressed properties in the local market, and help push the prices upwards. In addition, investors are more likely to be non-local and suffer from high search costs and informational disadvantage about the local real estate market and individual properties. Thus, whether investors pay more or less for a given property is an empirical question.

The price impact and investment performance of investors are clearly important for investors and consumers. These issues are also of potential interest to policy makers to the extent that the price impact of investors might influence the speed and magnitude of recovery in housing markets, particularly in markets with a large percentage of distressed properties.

Whether acquisition activity by investors improves home prices or suppresses them further is also critical for the overall economy given that recovery in housing markets is a leading indicator of economic growth (e.g., Green 1997; Case et al. 2005; Leamer 2007; Ghent and Owyang 2010; and Kydland et al. 2014).

Given the limited history of investor purchases of single family homes, it is not surprising that this is one of the first papers to analyze the role of investor buyers on property prices in distressed markets. The other paper on this topic is by Mills et al. (2017), who show that large “buy-to-rent” investors are less likely to re-sell homes within two years of purchase, and that house price appreciation in 2013 was higher in areas with a larger share of buy-to-rent investor purchases in 2012.Footnote 3 In this paper, we investigate whether investor buyers obtain properties at a discount or premium compared to individual purchasers, and the price externality they impose on other properties in the market. In addition to examining factors that contribute to the price discount/premium the investor buyers experience and the price externality they create, we also study factors that determine the likelihood of a property being purchased by an investor buyer versus an individual buyer.

The dataset analyzed to address these questions consists of 72,128 transactions involving single-family transactions with approximately $20.212 billion in value that occurred in Miami- Dade County, Florida, between January, 2009 and September, 2013, the date of the extraction of the data. Of these transactions, investors, defined as grantees that purchased 2 or more single- family dwellings or purchased 1 single-family dwelling as an LLC, LP, etc. during the sample period, purchased 24,607 single family dwellings (34.1% of the sample size and 29% of the sample value)Footnote 4 4. Within the investor group, large investors (6 to 28 purchases) purchased 8925 single-family dwellings (12.4% of the sample) with a collective expenditure of approximately $1.29 billion. Medium investors (3 to 5 purchases) purchased 5218 single-family dwellings (7.2% of the sample) with total expenditures of approximately $961 million. Small investors (2 purchases or 1 purchase by a LLC, LP, etc.) purchased 10,464 single-family dwellings (14.5% of the sample) with total expenditures of approximately $3.626 billion. Single-purchase buyers purchased 47,521 single-family dwellings (65.9% of the sample size and 71% of the value) with total expenditures of approximately $14.33 billion. We exclude all bulk sales from the sample since the price recorded for the bulk sale is for the block of properties and we cannot determine the individual price for each property in the bulk sale.Footnote 5

The analysis conducted for this study suggests that, holding other factors constant, investor buyers bought single-family dwellings at an average discount of 9.5% from the prices paid by individual buyers who bought only one dwelling during the same time period in this market. The analysis further suggests that compared to single-purchase buyers, institutional investors (investors with 10 or more purchases in at least one year)Footnote 6 purchased at an average discount of 7.7%, large investors (6 to 28 purchases during the sample period) purchased at an average discount of 13.6%, medium investors (3 to 5 purchases during the sample period) purchased at an average discount of 11.1%, and that smaller investors (2 purchases, or 1 purchase as an LLC, LP, etc.) purchased at an average discount of 8.0%, compared to single- purchase buyers. There is variation in the literature with Mills et al. (2017) defining micro investors as investors that purchased 1 to 2 properties consistent with our definition. Their small investors purchased between 3 and 10 properties, medium sized investors purchased between 11 and 50 properties and large investors purchased more than 50 properties. In our data, 28 properties was the maximum by a group that had not purchased at least 10 properties in a year meeting the “institutional” definition. Our breakpoints for the middle two groups does not materially impact the empirical results.

The findings support the contention that investors buying multiple individual properties do indeed have buyer power in local housing markets relative to single-purchase buyers, with some variation in buyer power across small, medium, large, and institutional investors (with size determined by number of dwellings purchased by each type of investor). Notably, the smallest investors captured discounts approximately the same as the discount capture by the institutional investors (8.0% versus 7.7%, respectively). Given that investors are purchasing at discounted prices relative to the prices paid by single-purchase buyers, it appears that single-purchasers rather than investors are more likely to be responsible for overall price recovery in the market.

However, we provide evidence that investor buyers create positive price externalities for other properties in the market. Percent of purchases by investor buyers, defined as the number of investor purchases in a census block divided by the number of sales in the census block, indicates upward pressure on prices in the market. We find that a 10% increase in the percentage of houses purchased by investors in a census block leads to a 0.20% increase in house prices in that market. We arrive at this result after controlling for the impact that investor purchases have on the overall demand in the market. We attribute the positive impact of investor purchase on property values to the fact that distressed properties have a negative externality on the values of other properties in the neighborhood, and purchases of distressed properties by investors help reduce this negative externality. It is also possible that large purchases by investors send a signal to other potential buyers that the homes are undervalued, and encourage these buyers to enter the market and marginally improve property valuations.

Large Investors in Single-Family Home Markets

Single-family home markets have been traditionally dominated by small, local investors and consumers. However, the recent financial crisis decreased the homeownership rate and attracted large investor buyers seeking to create rental/appreciation portfolios using single-family homes.

According to a recent study from the Federal Reserve, investors buying three or more homes accounted for 6.5% of home sales nationwide in 2012, up from less than 1% in 2004 (Molloy and Zarutskie 2013). Larger investor buyers, mainly private equity firms such as Blackstone and Colony Capital, have invested $20 billion to purchase as many as 200,000 single- family homes throughout the United States. These large investor purchases represented 6–12% of distressed home sales from 2012 through mid-2013 (Rahmani et al. 2013).

About 2.4 million single-family homes were converted from owner-occupied to rental tenure between 2007 and 2011, which brought the total number of single-family rental homes to 14 million. The 14 million rental homes represent approximately one-third of the nation’s rental housing inventory (Kurth 2012).Footnote 7

Global investment banks have provided credit lines to fund single-family home purchases by investment firms, and helped them issue the first rent-backed security in November, 2013. For instance, Deutsche Bank provided approximately $3.6 billion to fund Blackstone’s acquisitions and Wells Fargo provided a $500 million line of credit to American Homes 4 Rent. Some analysts estimate the market for rent-backed securities to reach $1.5 trillion level (Rahmani et al. 2014). Some firms (e.g., Starwood Waypoint) have taken their new rental companies public as real estate investment trusts (REITs). The monetary policy by the Fed also contributed to these developments: interest rates at close to zero levels pushed pension funds and mutual funds to seek higher yields and pursue risky strategies and this led to additional flows of capital into rental single-family markets.

At first glance, entry of large investor buyers into the single-family home market appears to have many positive outcomes, such as improving property values by reducing the inventory of foreclosed homes, lessening the negative externalities caused by foreclosed homes on other home values, and bolstering local fiscal conditions. They also help with price discovery in markets where transaction volume has dried up.Footnote 8 The price discovery function became particularly critical for financial and real estate markets during the recent financial crisis.

However, there is some concern that large investors will seek to quickly get rid of as many of their houses as they can and cut maintenance expenditures as soon as they find more attractive investment instruments or if they suffer financial distress. There is also a concern in some markets about the possibility of another speculative cycle that could end in a bust.Footnote 9 Others are concerned about how large investor buyers will impact the local rental markets and affordability and accessibility for renters.

It is out of the scope of this paper to address all of these questions. In this paper, we focus on whether investor buyers acquire single-family dwellings at a premium or discount to single- purchase buyers and whether their purchases lead to higher or lower prices (externalities) for other dwellings in that market.

Our first prediction is that purchases by investor buyers will have a positive impact on the prices of other dwellings in the market. This is due to the simple fact that investor purchases will reduce the inventory of dwellings in the market. In addition, investor purchases may send a positive signal to other potential buyers about the market conditions and property valuations. Our second prediction is that, in the absence of frictions in the market and barriers to entry, investor buyers would neither enjoy a discount nor pay a premium when they acquire single-family dwellings. If investor buyers have to pay a premium, they can break into smaller units and mimic individual buyers to avoid paying a premium. If investor buyers enjoy a discount, more of them would enter and/or individual buyers would pool their resources and mimic investor buyers to enjoy a similar discount. Thus, barring frictions and barriers to entry, we would expect any premiums or discounts to disappear and expect the price of an asset to be the same, regardless of whether that asset is purchased by an investor buyer or an individual buyer. This prediction is in line with the efficient market hypothesis that the price of an asset reflects all available information about its fundamental value, which will mirror the discounted present value of the expected cash flows from that asset.

However, several factors could lead asset prices to deviate from fundamentals and to vary across different buyer types. These factors could include costly information, lack of sufficient competition, transaction costs, agency costs, and frictions in financing. We list some of these factors below. Given opposing forces these factors have on the purchase price by an investor buyer, whether an investor would pay more or less for a given property becomes an empirical question.

Whether investor buyers enjoy a discount or pay a premium relative to single-purchase buyers is largely a question of whether they have effective “buyer power” in local housing markets.Footnote 10 10 The concept of buyer power has its roots in antitrust economics. Just as a monopolist has the ability to limit the quantity of a good or service brought to market and set prices profitably above the competitive level, so can a monopsonist limit its purchase quantity to set prices below the competitive level.

The concept of buyer power, however, is broader than monopsony power because it need not result solely from a depression of quantity purchased. Buyer power may also occur in the form of bargaining power (or, to use the phrase coined by Galbraith (1952, 1954), “countervailing power”).Footnote 11 Buyers with enhanced bargaining abilities may be able to significantly influence prices when there is imperfect competition among sellers.

Investors do enjoy some monopsony advantage during distressed times in many housing markets in which there is an abundance of properties for sale and little demand by local players.

However, there are other reasons why investor buyers might enjoy buyer power and acquire single-family homes at a discount to individual buyers. A major reason is that investors generally purchase these homes with cash, rather than obtaining mortgages for each home. Paying with cash gives investor buyers a competitive advantage when negotiating the price of a home because of two reasons. First, a cash buyer may present less risk to the seller of the deal falling apart due to the mortgage-contingency clause in a sales contract. Second, a cash purchase may reduce the time required to complete the transaction because cash buyers do not have to spend time obtain loan approval for the purchase. As a result of these two reasons, a seller would be willing to accept a lower price when she faces a cash buyer. Indeed, Asabere et al. (1992) and Lusht and Hansz (1994) report discounts for cash financing of 13 and 16%, respectively. A recent study by Hansz and Hayunga (2014), however, report a price premium of 4% for cash purchases.

Investor buyers might also enjoy buyer power because they bring transactional efficiencies to the market, including sophisticated targeting of potential acquisition properties, superior negotiation skills and experience and streamlined closings. These efficiencies increase their bargaining power and give incentives to sellers to accept lower prices.

On the other hand, investor buyers may end up paying more than individual buyers because single-purchase buyers are mostly local buyers while investors are more likely to be non-local buyers. Non-local buyers may have higher search costs, inferior knowledge of the individual properties and the local market, and unrealistic beliefs about market values. As a result, as empirically reported in Lambson et al. (2004) and Chinco and Mayer (2014), non-local (out-of-state) buyers pay a premium to local buyers. Studies by Rutherford et al. (2005), Levitt and Syverson (2008) and Kurlat and Stroebel (2015) show that there are indeed informational asymmetries in real estate markets, and real estate brokers utilize these informational asymmetries to sell their own houses at a higher price than they sell their clients’ houses.

Investors may also have a shorter time horizon to purchase, particularly when the investor buyer is a fund that has allocated a certain amount of funds for investment in specific single- family home markets. These buyers may outbid other buyers, and pay a price premium, in order to obtain the targeted capital commitment. This effect should be stronger in markets where investor buyers’ target volume is a larger percentage of the total value of homes available in that market.

It is also important to note that purchases by investors may reduce the inventory of distressed properties. It has been well established that distressed properties have a negative externality on the values of other properties in that neighborhood and that this impact increases with the size of the distressed property inventory (Campbell et al. 2011; Gerardi et al. 2012; Li 2014). Thus, when targeting to buy a large number of units, the buyer may be able to enjoy the positive externalities of her early purchases. By internalizing these positive externalities, investors may attach a higher value and may be willing to pay more for these early purchases than single-purchase buyers.

It is also possible that investors prefer to buy in bulk, or arrange simultaneous closings, in order to avoid possible positive externalities of their early purchases on their later purchases if their purchases increase demand and reduce the inventory of distressed properties, and thus avoid paying more for their later purchases. For example, large volumes of purchases by investors might send a signal to other potential (and hesitant) buyers that the homes are temporarily undervalued and now is the right time to buy. This signal could place upward pressure on prices.

The next section of this study presents an empirical analysis of a local housing market and the relative prices paid by dominant and non-dominant buyers, where dominant buyers are investors who emerged in this market following its recent price downturn.

Data

In order to conduct the empirical analysis, we obtain data from a number of datasets. The primary dataset contains information on sales in Miami-Dade County, Florida, from January, 2009 through September, 2013.Footnote 12 The dataset includes grantee and grantor information, sales price, date of sale, a unique property ID (Folio number), deed book and deed page, property address, square feet of the building, square feet of the land, number of bedrooms, number of bathrooms, number of stories, year built, effective year built, DORcode (type of property which allows us to identify single family homes) and SalesCode (type of sale variables: Transfer qualified as arm’s length by deed; Corrective deed, quit claim deed, etc.; Auction/Deeds from financial institutions; Deeds executed by bankruptcy trustees; Transaction involving affiliated parties; Sale not exposed to the open-market; and Forced sale or sale under duress).Footnote 13 A second dataset from Miami-Dade contains information about properties with pools that we use to create a pool dummy variable. A third set of yearly datasets are obtained from the Florida Department of Revenue (FDOR). Each year, every Florida County provides a dataset that contains the assessed value of the land and assessed value of each property to FDOR. We use the FDOR Miami-Dade datasets to estimate the percentage of value from the land and match with the sales dataset by year and by property ID. The dataset also contains a quality description each year that we match with the sales data to obtain an estimate of the quality of the property. In addition, census block and census block group are available in the FDOR datasets and we use census block group to control for location. We match the data from the above-described datasets with information from the local MLS by the tax district’s property information numbers. We extract time on the market, sales price, list price, cash sale and REO sale information from the MLS data for the matched sample. To identify cash sales for non-MLS matched properties, we use as a proxy from the tax district data which shows whether or not there is a third-party escrow company payee identified for each property at the time of sale. If there is no third-party payee matched to the sale, we consider this to be a cash sale.Footnote 14 To identify REO properties, our first cut is to use REO sales identified in the MLS data. For the remaining MLS and non-MLS sales, we examine ownership of each property and code as a REO; bank owned, owned by a mortgage company, ownership by financial institutions such as FNMA, HUD, etc.

We define as investors grantees that purchased two or more properties or grantees that were identified as a LLC, LP, Inc. and had only one purchase during the sample period. Investors were identified by visual inspection of all the grantee names and classified as either an individual or an investor. The number of purchases by each investor was tallied and the small investor group includes all investors that have 2 purchases or 1 purchase by an LLC, LP etc. The medium investor group includes all investors with 3 to 5 purchases during the sample period. The large investor group is defined as investors that purchase 6 to 28 houses during the sample period, but no years in which the entity has 10 or more purchases. The institutional group is defined as an entity with 10 or more purchases in a given year and then including all other purchases for that entity. All institutional purchasers purchased at least 10 properties or more in one or more years. The average number of purchases for the 118 institutional purchasers is 39.58 properties over the five years. Fifty eight percent of the institutional purchases have 40 or more observations, 72% have 30 or more observations, 87% have 20 or more purchases and the remaining 13% purchased between 10 and 19 houses over the sample period with a least one year with 10 or more properties purchased.Footnote 15

The initial data had 148,128 transactions from 2009 through September 2013. We excluded all sales with a price below $20,000 with 92.5% of sales below $20,000 having a transaction price of $100 or less. The remaining 7.5% below $20,000 had an average price of $6815. We excluded another 201 sales that had a price of $10,000,000 or greater and dropped 11,801 sales that were purchased by a financial institution such as a bank or FNMA on the assumption that these are properties financial institutions purchased at foreclosure auctions. This leaves 79,009 transactions. Another 6881 or 4.6% of the initial sample is deleted due to missing data, leaving a final sample of 72,128 transactions with investors purchasing 24,607 of these properties and single-purchase buyers purchasing the remaining 47,521 properties.

We present variables used in the analysis and their description in Table 1. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the full sample, single-purchase purchases and investor purchases with a difference in means t-test. Sales prices are lower for investor purchases ($239,024 vs. $301,566), but they are also smaller, older, have smaller lots, with lower land value percentages associated with lower valued properties. Fewer bedrooms, bathrooms, fewer stories and a lower percentage without a pool are consistent with lower valued properties relative to properties bought by single-purchase buyers. A higher percentage of investor properties are fair or average quality and a lower percentage are above average or excellent quality compared to properties purchase by single-purchase buyers.

While Table 2 provides a comparison between single-purchase buyers and investors, Table 3 summaries key variables over time between single-purchase buyers and investors. Table 4 provides additional statistics by year and by each investor group for the same set of variables. REOs have been a primary issue in the last five years and the data indicates that the largest percentage of REOs in this sample occurred in 2009, with a high of 44% in 2009 decreasing to 18% in 2013. In Table 4, we see that 30 % of smaller investor purchases are REO properties, with a high of 48% in 2009 and likewise decreasing to 18% in 2013. Medium sized investors (3 to 5 purchases) followed a similar pattern with an average of 30%, 59% in 2009 and dropping off to 24% in 2013. The average percentage REO purchases for investors that purchased 6 to 28 properties is 30%, with a similar trend of 54%, highest in 2009 and 23%, lowest in 2013. The institutional investor group follows a similar trend with a high of 41% in 2009 and a low of 17% in 2013 with an average of 26% over the five years. The trend in the data indicates a significant decrease in the number of REO transactions over the last five years.Footnote 16

Another variable of interest that has generated a number of articles in the popular press is the cash transaction.Footnote 17 From Table 2, we note that investors pay cash for about 70% of their purchases and individuals buy with cash in about 29% of their transactions over the 2009–2013 sample period. In Table 3, these estimates are by year and we see that individuals used cash in 24% of their transactions in 2009 and approximately 38% in 2013. In Table 4, we observe that small investors with 2 or fewer purchases buy with cash in 53% of the transactions in 2009 with an increase in cash purchases to 73% in 2013. Panel B provides statistics that show a similar pattern, with medium investors using cash in 60% of their 2009 transactions and increasing to 75% in 2013 with an average of 68%. Large investors that purchased 6 to 28 properties used cash in 70% of their transactions in 2009 and 79% in 2013 with an average of 78%. Not surprising, institutional investors purchase with cash in approximately 84% of their purchases, with a range of 80% to 89% over the five-year period. The data indicates that cash purchases were increasing in the small and medium investor groups with the large investor and institutional group purchasing with cash at a relatively high rate throughout the sample period.

Statistics from Tables 3 and 4 indicate that percentage of properties with a pool is reasonably stable on a per group basis over the five years, with single-purchase buyers at 28%, small investors at 26%, medium investor group at 18% and large investors at 15%. Sale price in general is trending up over the sample period, though for large investors the price is highest in 2009, drops for 2010 and 2011, and rebounds in 2012 and 2013. In addition, price per square foot (PSF) is following the same trend, suggesting an improving market. One other item of note in these tables is that the portion of transactions through the MLS for all groups is dropping over this time period. Single-purchase buyers have the highest MLS usage rate of 70%, though 2013 is showing a drop to 59% thru September 2013. MLS transactions dropped from a high of 67% in 2009 to 49% in 2013 for small investors and dropped from a high of 67% in 2009 to 46% in 2013 for the medium investor group. The large investor group has a high of 56% in 2009 and a low of 38% in 2013. The institutional investor group shows less of a decline, with a high of 37% in 2009 and a low of 26% in 2010, and an average of 32% over the five years.Footnote 18

For the MLS subsample in Table 2, average time on the market is 147 days for properties purchased by investors and 160 days for single-purchase buyers, with a list price of $294,170 for investor purchased properties and $350,510 for single-purchase buyers. MLS sale prices are $268,440 for investor purchased properties versus $323,887 for single-purchase buyers.Footnote 19

Methods

We estimate a model with census block group fixed effects and sale year month fixed effects. The initial empirical model we estimate allows us to compare investor purchased properties to properties purchased by single-purchase buyers, and takes the following form:

where the dependent variable y is the logged sales price, I is a dummy variable indicating an investor purchased the property with variations (small, medium, large, or institutional buyers), C is a dummy variable indicating the house is purchased with cash, R is a dummy for a REO, M is a dummy for sold through the MLS, Q is a set of variables describing the relative quality of a property in a given year, and S is a set of additional variables describing the type of sale. The vector Xi for the sales price model includes a full set of housing characteristics, including size, effective age, bathroom and bedroom counts, and pool. The last term in (1), ε is a random error term.

We also control for the percentage of houses sold (the number of sales in census block divided by the number of houses) and the percentage of sales that can be attributable to investor buyers (the number of investor purchases in census block divided by the number of sales in the census block), for each year. The former variable captures the volume of transaction activity, as a proxy for demand in the market, while the latter variable helps identify the impact of investor activity on house prices in the market.

Three alternative specifications of the price model allow more focused analysis of the statistical relationships between transaction price and buyer types. In Table 7 we replace the Investor variable with four binary variables defined in Table 1 that refine the type of investor into Small Investor (two or fewer purchases), Medium Investor (3 to 5 purchases) and Large Investor (6 to 28 purchases with none greater than 9 in a year) and Institutional Investor (at least 10 purchases in one year) categories. These binary variables take the value of 1 if the transaction involves a grantee who fits the size categories defined above and 0 otherwise. The omitted category is single-purchase buyers. Note that the number of purchases used to define the investor groups is based on prior definitions for the “micro investors” and “institutional investors” whereas the middle two groups are defined by our desire to divide the remaining properties into two closely equal groups in terms of number of observations. The reported results are reasonably robust to changes in the group definitions.

In Table 8 results are presented for models where the samples are either MLS sales or Non-MLS sales.In Table 10 Panel A, coefficients for the investor variables are presented for each year where the model is based on either Model 4 in Table 6 or Table 7. In Panel B, we split the sample into CASH only purchases and Financing-only purchases and estimate Model 4 in Table 6 for the overall investor variable or Model 4 in Table 7 for the four defined groups of investors. Panel C examines the models for REO properties and a sample that excludes REO properties.

We also study if properties purchased by investor buyers stayed on the market longer or shorter than those purchased by individual buyers. To do so, we conduct two sets of time-on-the- market analysis. First, we estimate eq. (1) with the dependent variable y representing the days the property stayed on the market. The time-on-the-market model includes a similar set of variables as the initial sales price model, but the sample is only for the MLS sold properties.Footnote 20 The time on the market model also includes the degree of overpricing, DOP, as an additional control variable. DOP is the percentage deviation of the list price, LP, from an expected list price for a house described by X housing characteristics and M marketing attributes, and is calculated as log(LP) - E(log(LP); X, M). The model also has controls for list year and month, whereas the sales price model includes controls for sale year and month. Both price and time-on-the-market models have fixed-effects for census block group to control for location and t-tests are based on heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors that account for clustering by house.

The second estimation of time on the market uses a hazard model with a Weibull specification of the baseline hazard function:

where φ is a duration dependency parameter, λ is a scaling parameter, t is time on the market, and other variables are as previously described (see Lancaster 1990, for further discussion). T-tests based on heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors that account for clustering by house are presented along with the model coefficients.

We also estimate a Probit model to examine the characteristics that determine the likelihood of the buyer of the property being an investor buyer versus an individual:

In Eq. (3), the dependent variable Prob (I) is the probability of an investor purchasing the property, and X, C, R, M, Q, and S are as defined above and in Table 1.

Empirical Results

The results of the probit model are presented in Table 5. The probit model results are similar to the results from the difference in means t-tests. Larger properties and above average quality properties are less likely to be purchased by investors. Likewise, MLS listed properties are less likely to be purchased by an investor relative to individuals. Properties with more bedrooms are more likely to be purchased by investors, though the marginal effect is only .013. Notably, cash purchases are 35% more likely to be by an investor and REO sales are more likely to be purchased by an investor. It appears that investors are better equipped to compete for distressed properties, prefer properties that are average or below average in quality, and more frequently purchase with cash.

Results obtained from the initial regression model, presented in Table 6, indicate that investors are purchasing properties at approximately a 17% discount relative to individuals after controlling for physical characteristics and a proxy for quality. We then control for types of sales (whether the transfer qualified as arm’s length by deed, Corrective deed / quit claim, Auction/Deed from a financial institution, Deed executed by bankruptcy trustees, Transaction involving affiliated parties, Sale not exposed to the open-market, or Forced sale or sale under duress) along with REO and Cash. This results in a reduction of the discount to approximately 8%. The last controls added in Model 4 include the Percentage of Sales in a Census Block defined as the number of sales by year divided by the number of housing units in the 2010 census block. This demand variable indicates that prices increase as the percentage of houses transacted in a census block increases, with a 10% increase associated with a 0.79% increase in housing prices. We also include the percentage of houses that sold that are purchased by investors in a census block by year. The coefficient is .00020, thus a 10% increase in investor purchases is associated with a 0.20% increase in purchase price. Thus, while investors purchase at a discount relative to individuals, their purchases have a positive impact on market values of houses in that census block market. As a result, controlling for the percentage of sales and percentage of investor purchases in a census block, the Investor Purchase discount increases, from 8.4% to 9.5%.

In Table 7, results are provided for investor groups, 2 or less, 3 to 5 purchases, 6 to 28 purchases and institutional (average 40 purchases, must have at least one year with 10 purchases). These results indicate that the two middle groups purchase at deeper discounts and that small investors and institutional investors purchase at similar discounts. The other variables have similar results to those found in Table 6. REOs sale at approximately a 14% discount, MLS sales are at a premium of 4.5% and cash sales occur at a discount of approximately 12%. The quality proxy variables have the expected signs compared to average quality, with fair quality selling at about a 9% discount, above average quality properties selling at a 6% premium and excellent quality properties selling at a 15% premium. Comparing model 3 and 4, we note that controlling for the percentage of sales and percentage of investor purchases in a census block increases the Investor Purchase discount for every investor group. Thus, while buying properties at a discount, each group of investors has a positive contribution to the market values of houses in that census block market.Footnote 21

Examining the purchases that occurred through the MLS in Table 8, investors purchase at a 10.2% discount compared to a 9.5% discount for the full sample. The smaller investor MLS group purchases at a 7% discount compared to an 8% discount for the full sample and a 7.8% discount for the non-MLS purchases. The results are very similar for the small investor. The medium group of investors purchases at about the same discount across the MLS at 11.3% and the full sample at 11.07%, but for the medium investor the Non-MLS discount is about 2 percentage points lower at 8.6%. The large investors purchase at a discount of 13.6% for the full sample, compared to the MLS sample discount for these large investors of 16.3% and the Non- MLS discount of 7.9%, suggesting that compared to individual that purchase thru the MLS, large investors are able to negotiate better prices thru the MLS than they are when they compete against individuals buying non-MLS properties. Institutional investors purchase at a 7.7% discount in the full sample, a 12.8% thru the MLS, but only a 2.7% discount when competing for properties compared to individuals purchasing outside the MLS.

It is interesting that, except for small investors who purchased one or two properties during the sample period, investors enjoy larger discounts when they purchase MLS-listed properties. It is also interesting to note that price advantage enjoyed by investors thru MLS becomes larger as the investor size increases. One possible explanation is properties not listed on MLS require better knowledge of the individual property and the surrounding area. In some distressed sales, buyers are not even allowed to enter and inspect the property. In those cases, local buyers who already know certain features of the property will have informational advantage over investor buyers who are less likely to be local. It is possible that MLS reduces such informational asymmetries, at least for a subset of properties, between the two groups of buyers.Footnote 22 This argument is in line with our result that larger investor buyers enjoy deeper discounts with MLS-listed properties since larger investor buyers are more likely to be non-local.

In fact, this argument is also supported by the coefficients of the “sale type” variables in Table 8: Corrective deed / quit claim deed, etc., Auction/Deeds from financial institutions, Deeds executed by bankruptcy trustees, Transaction involving affiliated parties, Sale not exposed to the open-market, Forced sale or sale under duress and REO sale. As expected, each of these sale types has a negative impact on the sale price. Notably, however, the absolute value of each of these coefficients is smaller for MLS sales than for non-MLS sales. In other words, MLS reduces the negative impact of each of these sale types. Given that these are the transaction types where informational advantage of local buyers is likely to be more pronounced, we conclude that MLS helps alleviate informational asymmetries in the market.

The time on the market models in Table 9 for MLS marketed properties suggest that investors do not necessarily target properties that have been on the market longer or shorter than average. In Model 1, Investors purchase properties that have been on the market about the same amount of time as individual purchased properties. In the 2nd model, the evidence indicates that the Institutional investor group purchases properties that have been on the market about 7.1% longer than individual purchased properties. However, the duration models (3 & 4) tell a slightly different story. Investor purchases take slightly more time, but once we separate the investors into groups, it appears again that it is the institutional investors that are buying properties that have been on the market a slightly longer period of 1.7% compared to individual purchased properties. In either case we are only looking at roughly 3 to 11 more days depending on whether you use the estimate from the duration model or the regression model. Our results for time on the market suggest that time on the market is only marginally important in examining investor activity in the housing market.

In Table 10, we estimate Eq. 1 (Table 6 regression model 4 and Table 7 regression model 4) for each year. Panel A reports the Investor coefficient and the Investor group coefficients. The results indicate that the discount for investors is stable over time, with a discount of approximately 10% each year. For the four investor groups, the discount ranges from a statistically significant 6.5% to 15.6% with no discernable pattern. One item of note is that in 2013, the institutional investor group purchased at similar prices as individuals in the market. It is also worth noting that institutional investors as a group purchased their largest number of houses during the first nine months of 2013, 1482 compare to a high of 1237 in 2012 for a full year.

Panel B of Table 10 presents the results when the complete sample is separated into a CASH sample and a Financing sample. Investor properties purchased with CASH compared to individual properties purchased with CASH are purchased at about a 9% discount with a range between 7% and 13%. Investor purchased properties that use financing purchase at a discount of between 6.3% and 9.3% compared to individual properties purchased with financing. Thus, though somewhat smaller, investor buyers enjoyed discounts when they purchased with financing as well as with cash.

Panel C of Table 10 results for REO investor purchases and Non-REO investor purchases indicate that investors are able to purchase REO properties at deeper discounts than individuals purchasing an REO with a range of 9.5% to 15%, with the larger investors enjoying the deepest discount. For the sample excluding REOs, investors purchase at lower discounts than the same REO group, with the exception of institutional investors. They buy non-REO properties at prices paid by individuals buying non-REO properties, but buy REO properties at the largest discount, 14.7%, of any of the investor groups. REOs make up about 26% of institutional purchases over the sample period, the lowest of any group, but Auctions/Deeds from financial institutions represent about 48.5% of institutional purchases during the sample period, the highest of any group, then next highest is the large investor group at approximately 30% of their purchases, while REOs represent about 38% of their purchases. Individuals purchased only 1.2% of Auctions/Deeds from financial institutions, while about 30% of their purchases are REOs.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that investors purchased single-family homes at discount prices relative to single-purchase buyers during the years 2009 through 2013 (with the exception of institutional investors in 2013). Small investors purchased at a discount of approximately 8.0%, medium investors purchased at a discount of 11.1%, large investors purchased at a discount of 13.6%, and institutional investors purchased at a discount of 7.7%, relative to single-purchase buyers. We also provide evidence regarding the price externality created by investor buyers in the market. We find that a 10% increase in the percentage of houses purchased by investors in a census block (the number of investor purchases in census block divided by the number of sales in the census block) leads to a 0.20% increase in house prices in that market. We attribute the positive impact of investor purchase on property values to the fact that distressed properties have a negative externality on the values of other properties in the neighborhood, and large purchases of distressed properties by investors help reduce this negative externality. It is also possible that large purchases by investors send a signal to other potential buyers that the homes are undervalued, and encourage these buyers to enter the market and drive up the prices.

Notes

In 2012, Blackstone Group committed more than $3 billion purchasing and renovating single-family dwellings through its Invitation Homes division and related its subsidiaries. (http://www.blackstone.com/the-firm/overview/history, last accessed 5/6/2015.) Also, American Homes 4 Rent has acquired single-family dwellings in 30+ markets around the U.S. (http://americanhomes4rent.com/, last accessed 9/18/2013.)

There is a large experimental literature on booms and busts in asset markets. In two recent studies involving experimental real estate markets, Ikromov and Yavas (2012a, 2012b), for instance, offer evidence that prices in experimental real estate markets deviate from their fundamental values, and the degree of these deviations are impacted by such factors as transaction costs, short selling restrictions, and the volatility of the cash flows from the asset.

It is also worth noting two other studies that involved investor buyers. Gay (2015) examines the impact of real estate investors on housing affordability in the local market and finds a negative impact. Bracke (2016) studies purchases of buy-to-rent buyers and finds that they pay less than other buyers for equivalent properties.

There is some possible ambiguity regarding the classification of small investors. We define small investor as 2 purchases or 1 purchase by a LLC, LP, etc. It is possible that some of these LLCs or LPs are individual buyers who simply set up an LLC or LP and purchase under that LLC or LP, in which case we would be overestimating the sample size of small investor group. As will be illustrated in our findings, this possible distinction is not of material importance. We analyze the role of each investor group, and the small investor group has the same directional and magnitudinal impact as other groups.

All bulk sale 597 bulk properties (597 properties) by various investors were excluded from the sample due to price identification/assignment problems. They are identified as multiple parcel sales in the data. FDOR defines them as “Arm’s-length transaction transferring multiple parcels with multiple parcel identification numbers”. The 597 properties represent 0.82% of the sample right before we dropped them from the final Miami Dade County single family dataset. The rationale for removing them from the sample is that the sale price is the total of all properties and is the same for each bulk sale set of properties we examined. Thus, we are unable to determine a price for each individual property in these sets. One possibility is to divide price evenly across properties in a given bulk sale purchase, but this would not match the correct price with the correct characteristics of each property. As an illustration of the problem, for one bulk purchase by “Roar Investments” the mean, minimum, maximum and medium price is $1,098,000 for each of the 23 properties in this bulk sale set in 2011. We could divide the $1,098,000 by the total of 23 properties and assign this average price to each of the 23 properties, but that would assume that each of the properties are identical in terms of housing characteristics (square feet, age, pool, fireplace, etc.) and location. For the entire sample of 597 bulk sale properties the average bulk sale price is $1,108,393 with a median of 799,800.

This definition is consistent with one provided by RealtyTrac (2015) where Institutional Investors/purchasers are entities that purchase at least 10 properties in a calendar year. We define our institutional investor group as having 10 or more purchases by a company in one of the five years in Miami-Dade County with all other purchases by these investors also classified as institutional purchases. This definition of Institutional Investor determines the maximum of the next group of large investor classification at 28 purchases. The choice of the cut for the other groups does not materially impact the empirical findings.

See Schnure (2014) for a detailed analysis of the decline in home ownership rate and the rising role of institutional investors in single family rental homes.

See Camargo et al. (2014) for a discussion of how the information contained in asset prices plays a crucial role in the decision-making processes of many agents in the economy and what role a government can play in “unfreezing” a market. Cespa and Foucault (2014) show how a small drop in the liquidity of one asset can propagate to other assets and can, through a feedback loop, lead to a large drop in market liquidity and to flash crashes.

The term “buyer power” should not be confused with “buying power” which is commonly used to refer to the amount of money available to purchase a good or service.

See von Ungern-Sternberg (1996) for a detailed exposition of the theory of countervailing power.

The rationale for the time period is that grantor and grantee information is available from January 2009 and we extracted the data in September/October 2013.

See “Real Property Transfer Qualification Codes for use by DOR & Property Appraisers Beginning January 1, 2012” at: http://dor.myflorida.com/dor/property/rp/dataformats/pdf/salequalcodes12.pdf

This may result in a bias toward zero with regards to the size and significance of the coefficient on the cash variable in the regression models. The overall cash percentage is 43.48%. The cash percentage is approximately 41% for the MLS sales and the estimated cash percentage is approximately 47% for the non-MLS sales using this method. These numbers are consistent with the 43% estimate by RealtyTrac, August 29, 2013 (http://www.inman.com/2013/08/29/all-cash-deals-on-the-rise/).

This definition is consistent with one provided by RealtyTrac (2015) where Institutional Investors/purchasers are entities that purchase at least 10 properties in a calendar year.

Note that we ended the sample in September 2013 when we collected the data, thus we are not comparing a full year of data to prior years.

For example, a report by Goldman Sachs, in the Mortgage Analyst, August 14, 2013 titled “How much upside to purchase mortgage originations?” estimates an increasing percentage of cash transactions with approximately 30% cash transactions in 2009 and roughly 58% in the summer of 2013. RealtyTrac, August 18, 2014 state: “Among metropolitan statistical areas with a population of at least 500,000, those with the top six highest percentages of cash sales were all in Florida: Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach (64.1%)” is the highest.

The trend of increasing cash transactions and decreasing MLS market share is interesting. Banks are generating fewer transactions, impacting the fees they earn from financing residential real estate and brokers are selling a lower percentage of the transacting properties resulting in lower demand for real estate broker services and most likely lower total dollar commissions for real estate brokers. This analysis is admittedly limited to one market, so it would be interesting to see if this trend is occurring in other markets nationally.

Note that public records do not include information on marketing time. Therefore, analysis of marketing time is limited to properties sold thru the MLS.

We do not have time-on-the-market data for non-MLS properties. MLS sales comprise approximately 64% of the full sample.

In Table 7, we define small investor as 2 purchases or 1 purchase by a LLC, LP, etc. It is possible that some of these LLCs or LPs are individual buyers who simply set up an LLC or LP and purchase under that LLC or LP, in which case we would be overestimating the sample size of small investor group. In unreported results, we redid the analysis in Table 7 by redefining small investor as at least two purchases. Although this led to a small decrease in discounts enjoyed by each investor group, the results are similar to those reported in Table 7. We also extended the analysis to separate investors into flippers and non-flippers, where a flipper purchase is defined as an investor purchase that resold within two years of the original purchase. We find that flipper investors enjoy a discount of 15%, more than non-flipper investors. While controlling for flipper investors decreases the discount enjoyed by each investor group marginally, the results remain similar to those reported in Table 7.

In order to party reduce informational disadvantage they were facing, many institutional investors, including industry leader Blackstone, started partnering with smaller firms by 2012, who could provide better knowledge of local markets (Gittelsohn 2012).

References

Asabere, P., Huffman, F., & Mehdian, S. (1992). The price effects of cash versus mortgage transactions. Journal of the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association, 20(1), 141–150.

Bayer, P., Geissler C., Mangum K., & Roberts J.W. (2015). Speculators and middlemen: The strategy and performance of Investors in the Housing Market. NBER working paper 16784.

Bracke, P. (2016). How much do Investors pay for houses? Working paper, Bank of England.

Camargo, B., K. Kim & B. Lester (2014). Price discovery and interventions in frozen markets. Working Paper,

Campbell, J. Y., Giglio, S., & Pathak, P. (2011). Forced sales and house prices. American Economic Review, 101(5), 2108–2131.

Case, K. E., Quigley, J. M., & Shiller, R. J. (2005). Comparing wealth effects: The stock market versus the housing market. Advances in Macroeconomics, 5(1), 1–32.

Cespa, G., & Foucault, T. (2014). Illiquidity contagion and liquidity crashes. Review of Financial Studies, 27, 1615–1660.

Chinco, A. & C. Mayer (2014). Misinformed speculators and mispricing in the housing market. Mimeo.

Galbraith, J. K. (1952). American capitalism: The concept of countervailing power. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Galbraith, J. K. (1954). Countervailing Power. American Economic Review, 44, 1–6.

Gay, S. (2015). Investors effect on household real estate affordability. Working Paper, University of Chicago.

Gerardi, K., E. Rosenblatt, P.S. Willen & V. Yao. (2012). Foreclosure externalities: Some new evidence, NBER working paper 18353.

Ghent, A. C., & Owyang, M. T. (2010). Is housing the Business cycle? Evidence from U.S. Cities, Journal of Urban Economics, 67(3), 336–351.

Gittelsohn, J. (2012). Private equity has too much money to spend on homes. Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-06-13/private-equity-has-too-much- money-to-spend-on-homesmortgages.html.

Green, R. K. (1997). Follow the leader: How changes in residential and non-residential investment predict changes in GDP. Real Estate Economics, 25(2), 253–270.

Hansz, J. A. & Hayunga K. (2014). Cash financing in residential real property transaction prices, working paper.

Houghwout, A., D. Lee, J. Tracy & W. van der Klaauw (2011). Real estate investors, the leverage cycle, and the housing market crisis. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report 514.

Ikromov, N., & Yavas, A. (2012a). Asset characteristics and boom and bust periods: An experimental study. Real Estate Economics, 40, 603–636.

Ikromov, N., & Yavas, A. (2012b). Cash flow volatility, prices and price volatility: An experimental study. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 44(1–2), 203–229.

Kurlat, P. & Stroebel J. (2015). Testing for Informational Asymmetries in Real Estate Markets. Review of Financial Studies, forthcoming.

Kurth, R. (2012). Single-family rental housing: The fastest growing component of the rental market (data note). Economic and Strategic Research, 2(1), 1–5. Fannie Mae.

Kydland, F. E., Rupert, P., & Sustek, R. (2014). Housing dynamics over the Business cycle: An international perspective. Working: Paper.

Lambson, V., McQueen, G., & Slade, B. (2004). Do out-of-state buyers pay more for real estate? An examination of anchoring-induced bias and search costs. Real Estate Economics, 32(1), 86–126.

Lancaster, T. (1990). The econometric analysis of transition data. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Leamer, E. E. (2007). Housing is the Business cycle. NBER working paper no. 13428.

Levitt, S. D., & Syverson, C. (2008). Market distortions when agents are better Informed: The Value of Information in Real Estate Transactions. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90, 599–611.

Li, L. (2014). Why are foreclosures contagious? Mimeo.

Lusht, K., & Hansz, J. A. (1994). Some further evidence on the price of mortgage contingency clauses. Journal of Real Estate Research, 9(2), 213–217.

Mills, J., R. Molloy, & R. Zarutskie (2017). Large-scale buy-to-rent Investors in the Single- Family-Housing Market: The emergence of a new asset class? Real Estate Economics Forthcoming.

Molloy, R. & Zarutskie R. (2013). Business investor activity in the single-family-housing market, FEDS Notes 2013–12-05. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Rahmani, J., B. George, & R. O’Steen (2013). Single-family REO: An emerging asset class (3rd edition). North America equity Research: Mortgage Finance industry update (September 10). Keefe, Buryette and Woods.

Rahmani, J., B. George, R. Tomasello (2014). Securitization of single-family rentals. North America equity Research: Mortgage Finance industry update (January 14). Keefe, Bruyette and Woods.

Rutherford, R. C., Springer, T. M., & Yavas, A. (2005). Conflicts between principals and agents: Evidence from residential brokerage. Journal of Financial Economics, 76, 627–665.

Schnure, C. (2014). Single-family rentals: Demographic, structural and financial forces driving the new Business. Mimeo: Model.

von Ungern-Sternberg, T. (1996). Countervailing power revisited. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 14, 507–520.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, M.T., Rutherford, J., Rutherford, R. et al. Impact of Investors in Distressed Housing Markets. J Real Estate Finan Econ 56, 622–652 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-017-9609-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-017-9609-0