Abstract

This study attempts to shed some light on the extent of non-realtor broker listings on the MLS and their resulting price and time-on-the markets effects. Using duration, probit and selling price models, this study empirically examines whether the REALTOR designation provides a signal of quality that is reflected in the price and time on the market for sellers. Results indicate that properties listed by non-realtors on the MLS setting sell at lower prices, take slightly longer to sell, and are less likely to sell than properties listed by REALTORs in a MLS setting. Working with a REALTOR in a MLS setting appears to be advantageous to the seller.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Yinger (1981) presented a search model for real estate brokerage with an extension to a market with a multiple listing service (MLS). He advocated for legislation to mandate broker membership in the multiple listing service. While no legislation has been forthcoming, most residential brokers and agents have elected to join a MLS. Yinger makes a compelling case that search costs could be reduced and efficiency increased in the market for brokerage services, however there is scant empirical research that examines whether brokers operating in a MLS setting provide better services to sellers.

Comparing across MLS and non-MLS sales, Yavas and Colwell (1995) found that properties sold through a MLS had a lower price than similar properties sold directly by the owner (FSBO) or through a non-MLS participant broker. Johnson et al. (2005) also found that properties sold by a broker through the MLS had a lower price than broker-sold properties outside the MLS. But, Doiron et al. (1985), and Frew and Jud (1987) found that brokers obtain higher sale prices than owners selling their own property. Other studies by Kamath and Yantek (1982) and Colwell et al. (1992) found that brokers do not impact the selling price of a house.

In general, real estate agents with MLS affiliation acts as market makers for residential housing with the typical compensation structure being a fixed percentage of the transaction amount (see Anglin and Arnott 1991). There is evidence that a fixed percentage commission contract creates a potential source of conflict between sellers and agents given that the agent and the sellers receive significantly different payoffs as a result of the agent’s efforts or abilities to locate buyers willing to pay higher prices (Rutherford et al. 2005). Even though both should want the sale to occur at the highest price, the compensation agreement does not provide the necessary incentive for the agent to increase his search effort to locate the optimal trading partner (see Jud 1983; Maurizi 1974; Zorn and Larsen 1986 and Zumpano and Hooks 1988).Footnote 1 Yavas (1994) considers alternative compensation structures for real estate agents and concludes that in the most commonly used arrangement, a percentage of the transaction amount, the agent benefits by making as many matches as possible rather than searching for the optimal partner.

Listing strategy in real estate often focused on the role brokers play in selling properties and is complicated by the compensation structure for agents representing the sellers. The primary question from the viewpoint of the seller is whether the present value of the net sale proceeds is maximized by the listing strategy employed.

One listing strategy advocated by the National Association of Realtors (NAR) is to list the house with a “REALTOR.” The National Association of Realtors state explicitly that not all licensees are the same and that only agents that are members of NAR can properly call themselves REALTORS®. They also state that “When selling your home, your REALTOR® can give you up-to-date information on what is happening in the marketplace and the price, financing terms and condition of competing properties. These are key factors in getting your property sold at the best price, quickly and with minimum hassle.” In addition, REALTORS® are expected to “subscribe to a strict code of ethics and to maintain a higher knowledge of the process of buying and selling real estate.”Footnote 2 NAR also advocates that all licensees should become members of the MLS and local real estate boards. In a news clip, Fletcher (2004) poses two questions that we have modified to reflect a seller’s view. If you are a seller, would you prefer to be represented by a broker with one month’s experience or a broker with several years experience? He argues the obvious answer is the broker with the experience. The second question is, if you are a seller, would you prefer to list with a broker with one month’s experience who is a REALTOR or a broker with several years of experience who is not a member of NAR? Fletcher states that NAR indicates that the public should select the REALTOR and Fletcher disagrees, indicating that he does not believe that a REALTOR with a few days or weeks of training will favorably compare to the non-realtor with years of on-the-job experience.

NAR essentially maintains that REALTORs are expected to be “better” brokers. There is some evidence that REALTORs or REALTORs with designations earn higher income than non-realtors, see Crellin et al. (1988), Sirmans and Swicegood (2000), Izzo and Langford (2003). Izzo and Langford (2003) show positive relationships between the possession of REALTOR designations and cognitive moral development, income and job tenure. Izzo and Langford also argue that ethnical behavior is an important element of professionalism that leads to increased sales.

While prior work indicates that REALTORs may earn higher income, the most direct estimate of the value to an agent of being a REALTOR comes from a study by AbsoluteBRAND LLC conducted for NAR that was released on August 26, 2005. NAR released the following statement: “The REALTOR® brand generates an average of $32,000 in incremental income for every REALTOR® during his or her membership in the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF REALTORS®.”Footnote 3 In a related article by Realty Times, additional information is provided, and we quote: “The median number of years of experience for Realtors in 2004 was nine. The individual member brand value over a 10-year period was $32,383, or $3,238 annually.”Footnote 4

It does appear that agents may be better off by joining NAR as REALTORs. However, does the REALTOR designation make a difference for the clients paying the commissions? No study to our knowledge has examined whether using a REALTOR as the listing agent in a MLS setting improves the bargaining position of the seller and results in a higher probability of sell or a higher sales price for the seller. This study attempts to shed some light on the extent of REALTOR versus non-realtor agent listings on the MLS and their resulting price and time-on-the market effects. It is well known that the majority of brokers listing on the MLS are REALTORs. However, it appears that a small percentage of properties listing on the MLS are listed by non-realtors (approximately 1.2% in our data). This provides us with an opportunity to examine broker impact on price, time on the market, probability of sale, conditioned on their choice to join NAR, within a MLS setting. Prior research on how brokers impact selling price has focused on FSBO versus broker sales through the MLS, and broker sales through the MLS versus broker sales outside the MLS. The evidence from this research is mixed, with results indicating that the use of a broker increases the sales price, decreases the sales price and has no impact on the selling price (see Yavas and Colwell 1995; Johnson et al. 2005; Doiron et al. 1985 and Jud and Frew 1986; Kamath and Yantek 1982 and Colwell et al. 1992).

Yinger made a compelling case that search costs could be reduced and efficiency increased in the market for brokerage services by having all brokers join a MLS. Operating in Yinger’s world where “all brokers” are members of the MLS, but not necessarily members of NAR, we examine whether the REALTOR® designation works as a signal of quality and is associated with positive benefits to the seller using a REALTOR. However, to a large degree, we know that “realtor” is widely accepted as a term to indicate a real estate broker, agent or salesperson, and thus it is possible that the REALTOR designation does not provide any signal. In this case we should expect no difference in the quality of the service and benefits to the seller for REALTORs and non-realtors in a MLS setting. We have some evidence that REALTORs earn more and that the REALTOR brand is worth approximately $3,238 annually. Thus agents that maintain their REALTOR membership are better off. What we do not know is whether these higher earnings come at the expense of their clients or if their higher earnings represent a signal of quality and indicate that clients’ interest are best served by agents holding the REALTOR membership.

Our empirical results indicate that residential properties listed by non-realtors sell at lower prices, take slightly longer to sell, and are less likely to sell than properties listed by REALTORs in a MLS setting. These results indicate that brokers may have an impact on prices and suggest that working with a REALTOR in a MLS setting is advantageous to the seller.

The next section discusses the data, the third section presents the methods, the fourth section presents the results and a fifth section offers concluding remarks and some comments on future research.

Data

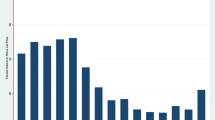

The data set consist of 116,596 observations of single family residential properties that sold or withdrew between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2005. The sample is from a large metropolitan Multiple Listing Service (MLS) consisting of several counties in Texas.Footnote 5 Variable names and data descriptions are provided in Table 1.

Data collected from the MLS include physical property characteristics (age, building square feet, pool, number of bedrooms, bathrooms, fireplaces, stories, living areas, and dining areas), market descriptors (month of listing and month of sale or withdrawal, changes in interest rates), marketability characteristics (tour of homes, open house, internet listing, vacant, tenant-occupied, builder), and broker characteristics (listing agent experience, age, broker versus agent). We elected to examine listing agent experience using three groups, rookies with 2 years or less, than three years, agents with 3 to 4 years, but would not be considered very experienced and agents that had 5 or more years of experience.Footnote 6 The data contains numerical MLS defined geographic variables that we use to control for location in the models. Calendar information includes the listing month and the month of sale during the year. Other variables include the list price, the selling price, and the days-on-the-market (DOM). For properties that are ultimately sold, days-on-the-market is measured as the number of days from the listing date reported in the MLS to the sale date as reported in the MLS. The days-on-the market for houses that went off the market without a sale is calculated as the number of days between the listing date and the day the property went off the market.Footnote 7 In addition, houses listed by a non-realtor brokers are identified with a binary variable, Non-realtor.Footnote 8 For this variable, a value of “1” denotes a non-realtor single family listing on the MLS. Non-realtors listed approximately 1.2% of the sample of 116,596 listings. We identified non-realtors by looking up each listing broker on the Texas Association of Realtors website directory and then double checked those against the National Association of Realtors website directory. If the broker was not found on either directory, we identified that broker as a non-realtor. In addition to the data obtained from the MLS, data relating to the broker’s experience, status (Licensed BrokerFootnote 9 or Salesperson), and broker’sFootnote 10 age were either available from Texas Real Estate Commission (TREC) or could be estimated from the data available from TREC.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the data broken out by whether the property was listed by a REALTOR or non-realtor representing the owner. Slightly more than 1% (1.2%) of the sample consists of non-realtor listings. A comparison of the two sub-samples shows that a majority of the 28 variables displayed are statistically different at either 1 or 5% level of significance. The comparison of sub-samples shows that non-realtor properties both list and sell at a lower price, are smaller and older, more likely to be larger lots and to be occupied by a tenant, and take longer to sell than REALTOR listings. Also, the non-realtor listings are more likely to be listed by less experienced brokers, less likely to be listed by a real estate Licensed Broker and less likely to be sold.

Materials and Methods

The first step in the analysis is to estimate the typical list price for a house described by X under market conditions described by M. The list price (LP) model is:

The residual of the list price model is used to estimate the degree of overpricing, DOP, the percentage deviation from an expected list price for a house described by X and M. DOP is calculated as log(LP) − E(log(LP); X, M). DOP is expected to influence the time-on-the-market, DOM.

Next, we specify a days-on-the-market model. Lancaster (1990, ch. 8.8) indicates that using a semi-log OLS model to estimate the model for DOM is equivalent to throwing away 39% of the data if the true model is exponentially distributed and 43% of the data if a Weibull distribution is more appropriate. In light of this fact, we estimate a DOM using a hazard model with a Weibull specification of the baseline hazard function:

where φ is a duration dependency parameter, λ is a scaling parameter, t is DOM, and other variables are as previously described. We use a proportional hazards specification to explain the contribution of the independent variables where

for some function g(.).

We modify this likelihood since the observed DOM is the minimum of two random variables: the time-to-sell and the time-to-withdrawal. Given that a seller can withdraw without selling introduces “censoring” into the duration data which may misleadingly shorten the average DOM. The variable, Sold Property, is a binary variable indicating whether a property was sold (Sold Property = 1) or withdrawn. For those houses that were withdrawn from the market at time t, the probability that the time-to-sell exceeds t is

The maximum likelihood estimates of β, φ and θ correct for this random and frequent censoring. See Lancaster (1990) for further discussion. The next set of models we estimate are hedonic selling price models. We estimate the price model using OLS and then correct for sample selection bias following the labor economics literature for wage equations where one has information on the characteristics of the individual but no wage data for those individuals who are not employed. For our model we have housing characteristics for all the properties, but no selling price for the 44,552 houses that did not sell during the sample period.

The selling price model is:

where the vector X i is similar to the X i for the time-on-the-market equation, except that the season variables relate to the month of the sale and the overpricing variable is excluded. Table 5 provides the results for the time-on-the-market equations and Table 4 shows the results for the selling price model corrected for possible sample selection bias. For housing studies and many other applications, the Heckman model (Heckman 1979) is an appropriate methodology when one suspects sample selection bias.Footnote 11 In general, sample selection bias refers to the case where a dependent variable is only observed for a restricted, non-random sample. In the estimation we take account of this possible selection bias, where in the first stage a probit model (see Table 4, Model 1) is used to predict the probability of a house being sold and in the second stage the IMR is included as a regressor in the housing price model. The dependent variable in this probit model is the variable Sold Property and the independent variables are those included in the selling price model plus the variables related to the listing season, excess time-on-the-market, defined as the residual from a log linear time-on-the-market model, and a variable measuring the rate of change in interest rates. While this regression with the IMR corrects for possible sample selection based on whether or not the property was sold, the issue of self-selection or endogeneity of the non-realtor variable may be a problem. We attempt to correct for the possible endogeneity of non-realtor by estimating a second probit model where the dependent variable is non-realtor and the independent variables are similar to the probit model for Sold Property, with the addition of Internet and Listing Agent Age (see Model 2, Table 4). The results are discussed below.Footnote 12

Results

The univariate statistics in Table 2 indicate a number of statistical differences between REALTORs and non-realtors with the most interesting results indicating that non-realtors take longer to sell, that a smaller percentage of the non-realtor listings eventually sold and that the list price, size, and selling price are all lower for non-realtor listings. These results are consistent with our findings using multivariate models.

In Table 3 we present the results for the two Probit models used to generate Inverse Mill’s Ratios (IMRs) to correct for possible sample selection and endogeneity. Table 3, Model 1, shows the coefficients for a Probit model that examines whether the property is sold or unsold during the sample period. Non-realtor listings are less likely to be sold. In addition, the probability of sale increases with broker experience, broker age, listing on the internet, ownership by a builder, marketing in a tour of homes, increases in interest rates, increases in dining and living areas, age, fireplaces and if the property has a pool. Increases in property size, number of stories, large lot, tenant occupied lead to a decrease in the probability of selling.

The second Probit model in Table 3 examines the probability that a property is listed by a non-realtor. A non-realtor listing is more likely to be listed by a less experienced broker. All other significant coefficients in model 3 are negative and indicate a lower probability of listing by a non-realtor. Experienced brokers, Licensed Brokers, older brokers, internet listings, houses with more dining areas, larger lots, and builder owned houses are less likely to be listed by a non-realtor.

To test for the effect of a non-realtor listing on prices, we estimated several selling price models. The results for these models are shown in Table 4. The first model is an OLS regression that does not correct for any potential biases. The second model is the Heckman selection model which corrects for possible sample selection bias based on the probability of sale. The third model attempts to correct for endogeneity. The fourth model attempts to correct jointly for the sample selection bias and endogeneity associated with the non-realtor listing variable.

As shown in Table 4, the results across the models are consistent. Non-realtors sell properties for 2.5–3.3% less than REALTOR listings.Footnote 13 The results for the other variables are mostly as expected. Houses sell for higher prices when they are larger, builder-owned, have a pool, are marketed with an open house or a housing tour. More experienced brokers obtain higher prices and an increase in the number of fireplaces or dining areas is associated with higher prices. Discounts to the selling price are evident for properties that are older, have more living areas, vacant or tenant occupied. Houses sold by brokers with limited experience and houses sold by Licensed Brokers receive lower prices.

The results for the selling price model (Model 2) with a correction for sample selection bias (using Heckman’s selection model) show that the coefficient for non-realtor listing is negative and significant with a magnitude of 2.5%. In this model the IMR is statistically insignificant; indicating that in this sample, after controlling for other characteristics, price is not subject to a sample selection bias based on whether the property sold or did not sell. In Model 3 where we attempt to correct for endogeneity, we find a coefficient of negative 3.3% and in Model 4 where we attempt to correct for both endogeneity and also include the IMR for sample selection bias, we obtain a discount of 3.1%. These results suggest that non-realtor listings sell at a discount of approximately 3% relative to REALTOR listings on the MLS.Footnote 14 The other variables show results much as expected and similar to Model 1. The coefficient for IMR1 is insignificant and the coefficient for IMR2 is significant, indicating endogeneity, but not selection bias.

In Table 5, we provide the results from estimating a Weibull failure time model corrected for censoring. The time-on-the-market effects of non-realtor listings are found to be positive and significant. The coefficient is 2.5% and is statistically significant, indicating that non-realtors take about 3 days longer to sell properties they list compared to REALTOR listed properties.

While statistically significant the three extra days on the market would not be a concern for most sellers. The model also shows that marketing time decreases for increase in age, bathrooms, fireplaces, living areas, dining areas. Houses with pools, builder owned and housing on market tours take less time to sell. Increase in listing agent experience and listings by Licensed Brokers also decrease the time on the market. Decreases in interest rates are associated with less time on the market. Marketing time increases for larger properties, more bedrooms, more stories, larger lots, tenant occupied, vacant, open houses, and for an increase in interest rates over the marketing period. Brokers with less experience also take more time to sell.

Thus, based on the results of the price models correcting for sample selection and endogeneity, the probit models and the duration model we find that properties listed by a non-realtor sell at a price discount of approximately 3%, take approximately 2.5% longer to sell and have a lower probability of selling in this market examined during 2005.

Based on our results, if realtors can sell more quickly and at a higher price, why do non-realtors exist in the MLS setting? It would appear that sellers would eventually discover that non-realtors in a MLS setting are at a competitive disadvantage and only list with REALTORs. Our data suggest that perhaps sellers have discovered this in general, for only 1.2% of the listings were by non-realtors, with the vast majority of agents selecting to become REALTORs.

In addition, there does not appear to be anything to prevent a non-realtor from obtaining the realtor designation and joining the majority. However, it appears that a small fraction of agents choose to go against convention, and sellers may be unaware of the fact they have selected a non-realtor given that the agent meets the state licensing requirements and is able to list properties on the MLS.

These results suggest that it may be useful for sellers to ask listing agents if they are REALTORs, how many years of experience the agent has and what level of income they earned from being a REALTOR on average over the last few years. It would appear that each component could provide some evidence of the quality of the agent for the seller. Unfortunately, a more complete database than is currently available is needed to examine these questions.

Conclusion and Future Research

This study examined non-realtor listings on the MLS and their resulting price and time-on-the market effects. Results show that non-realtor properties list and sell at a lower price, after corrections for sample selection and endogeneity related to non-realtor listings. The implications of the results suggest that working with a REALTOR in a MLS setting is advantageous to sellers when they list their properties. REALTOR designation appears to provide a signal of quality that is reflected in the sales price, the probability of sale, and time on the market.

Future research should examine this question in other markets to determine if these results apply. Another possible extension would be using a better database and track when a agent becomes a REALTOR and their duration as a REALTOR. This would allow a more precise measure of the impact that REALTORs have on prices and marketability in a MLS setting compared to non-realtors in the same MLS setting. NAR has long argued that REALTORs are better agents and this study finds results consistent with this position.

Notes

In this study we are not looking at for-sale-by-owner properties or broker properties that were not listed on the MLS, but are examining whether brokers listing on a MLS provide a benefit to clients if they join NAR and obtain the REALTOR membership.

The initial data sample had 125,923 single family listings. Due to missing values and extreme variables that were considered to be data entry problems, the final data set has 116,596 single family listings.

These groups closely follow categories used by NAR. “The 2005 NAR Member Profile shows that those REALTORS® working in real estate for two years or less earned a median income of only $12,850 in 2004. By contrast, the more experienced NAR members who have been in business for six to 10 years earned a median income of $58,700 in 2004. And those with at least 26 years of experience earned $92,600, up 37 percent from two years earlier.” Quote from: REALTOR Magazine Online: “Rookies Work More, Earn Less,” by Haley M. Hwang, January 3, 2006. We elected to roughly follow their categories, dropping down to 5 years for experienced agents and not differentiating those with 26 or more years of experience. Models were also estimated with experience and experienced squared instead of the dummy variables. The coefficients for non-realtor listings did not change.

Days-on-the market may be larger than our measure. We do not have repeated listing information and thus our calculation of DOM may be less than the actual time on the market. This problem is common in the empirical studies we are aware of.

We classified 13,379 listing agents in this process. We expect there might be some classification errors given that any point in the year a broker might elect to later join NAR or to drop their NAR membership. We did not repeat the classification each month.

Licensed Broker identifies an actual broker not a listing or selling agent.

Otherwise, we use broker as a generic term throughout the paper to represent a salesperson, an agent or an actual Broker.

The Heckman selection model corrects for selectivity bias by adjusting the conditional error terms using the Inverse Mills Ratio (IMR) so that the conditional error terms will have zero means.

In an attempt to see if our results were sensitive to the estimation procedure, we estimate a multivariate probit for sold and non-realtor jointly, and then calculate the IMR for the non-realtor model and include this IMR and the non-realtor variable in the selection equation of a Heckman model with selling price as the dependent variable. In addition, we estimate the Heckman model with the selection equation conditioned on the choice of a realtor or non-realtor without including the non-realtor IMR above. In both cases, the results for the non-realtor coefficient remain approximately the same.

We split the sample into three relatively equal groups and estimated the selling price models. The highest priced (LP > $199,999) group had a coefficient of −3.2% significant at 10%, the middle group had a coefficient of −1.84%, significant at 5% and the lowest priced (LP < 130,000) group had a coefficient of +0.72%, that was not statistically significant. These results indicate that for lower priced properties a REALTOR or non-realtor agent obtain similar prices, with non-realtors obtaining increasingly lower prices across the middle and highest priced groups.

In an attempt to examine other possible reasons for the discount, we examine whether non-realtor listing agents systematically misprice their listings compared to REALTORS. The results indicate that there is no observable systematic mispricing by non-realtors compared to REALTORS. We also examined whether there was a Large Firm effect by creating a size dummy variable where 1 = firms with at least 2% of the listings in the market to examine if agents associated with large firms might be systematically related to the non-realtor variable. The results for the non-realtor coefficient do not change when we include the large firm dummy variable. An anonymous referee suggested that professional designations might impact the results. We agree that a study on levels of professional designations attained through education and the impact on price, time on the market and probability of sale would be interesting. While we do not have the data to examine this issue in our dataset, recent research by Ford and Rutherford (2003), in a technical report for the Real Estate Center at Texas A&M using 59,599 sales during 2002 indicate that if a listing agent had at least one of the certifications (CRS, GRI, E-Pro), this was associated with a statistically significant and marginally higher sales price of approximately 0.54%. Using the estimate from their results, that would still leave approximately 2.5% as a premium for REALTORs compared to non-realtors.

References

Anglin, P. M., & Arnott, R. (1991). Residential real estate brokerage as a principal-agent problem. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 4, 99–125.

Colwell, P. F., Lauschke, D. P., & Yavas, A. (1992). The value of real estate marketing systems: Theory and evidence. University of Illinios (mimeograph).

Crellin, G. E., Frew, J. R., & Jud, G. D. (1988). The earnings of REALTORS: Some empirical evidence. The Journal of Real Estate Research, 3(2), 69–78.

Doiron, J. C., Shilling, J., & Sirmans, C. F. (1985). Owner versus broker sales: Evidence on the amount of rokerage commission capitalized. Real Estate Appraiser and Analyst, 51, 44–48.

Fletcher, D. (2004). Should NAR redefine “professional in real estate?” Realty Times, September 14.

Ford, J., & Rutherford, R. (2003). Impact of TRELA 1995, limited service representation, and agent certification in Texas on the marketing and pricing of single-family residential real estate: A comparison of empirical findings with real estate agent and customer perceptions. Technical Report to the Real Estate Center, Texas A&M University.

Frew, J. K., & Jud, G. D. (1987). Who pays the real estate brokers’s commission? Research in Law and Economics, 10, 177–187.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47, 153–161.

Izzo, G., & Langford, B. E. (2003). Realtor designations as an indicant of cognitive moral development and success in real estate sales. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 6(2), 191–202.

Jud, G. D. (1983). Real estate brokers and the market for residential housing. AREUEA Journal, 11, 69–82.

Jud, G. D., & Frew, J. (1986). Real estate brokers, housing prices, and the demand for housing. Urban Studies, 23(11): 21–31.

Kamath, R., & Yantek, K. (1982). The influence of brokerage commissions on prices of single-family homes. Appraisal Journal, 50, 63–70.

Johnson, K. H., Springer, T. M., & Brockman, C. M. (2005). Price effects of non-traditionally broker-marketed properties. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 31(3), 331–343.

Lancaster, T. (1990). The econometric analysis of transition data. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Maurizi, A. (1974). Occupational licensing and the public interest. Journal of Political Economy, 87, 399–413.

Rutherford, R., Springer, T. M., & Yavas, A. (2005). Conflicts between principles and agents: Evidence from residential brokerage. Journal of Financial Economics, 76, 627–665.

Sirmans, G. S., & Swicegood, P. G. (2000). Determining real estate licensee income. The Journal of Real Estate Research, 20(1), 189–204.

Yavas, A. (1994). Economics of brokerage: An overview. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 2, 169–195.

Yavas, A., & Colwell, P. F. (1995). A comparison of real estate marketing systems: Theory and evidence. Journal of Real Estate Research, 10, 583–599.

Yinger, J. (1981). A search model of real estate broker behavior. American Economic Review, 71, 591–605.

Zorn, T. S., & Larsen, J. E. (1986). The incentive effects of flat-fee and percentage commissions for real estate brokers. AREUEA Journal, 14, 24–47.

Zumpano, L., & Hooks, D. (1988). The real estate brokerage market: A critical reevaluation. AREUEA Journal, 16, 1–16.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, B., Rutherford, R. Who You Going to Call? Performance of Realtors and Non-realtors in a MLS Setting. J Real Estate Finan Econ 35, 77–93 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-007-9029-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-007-9029-7