Abstract

This explanatory sequential mixed methods study investigated the writing feedback perceptions of middle and high school students (N = 598). The predictive and mediational roles of writing self-efficacy and perceptions of writing feedback on student writing self-regulation aptitude were examined using mediation regression analysis. To augment the quantitative findings, the explanations students provided for either liking or disliking writing feedback were explored using open-ended questions. Quantitative findings revealed that students’ perceptions of the feedback they receive about their writing partially mediated the relationship between writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulation aptitude. Qualitative data suggested ways in which students perceive writing feedback—both positive and negative. Collectively, the quantitative and qualitative data illustrate the influential role writing feedback perceptions plays in middle and high school student writing motivation and self-regulation beliefs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“I just find it so hard to figure out what to put on a piece of paper. Like when I am looking at the paper I just can’t think. It’s weird”—ninth grader.

“I get frustrated and overwhelmed, at that point I just can’t bring myself to write anymore”—ninth grader.

“Many times I just get lost as soon as I start writing and I don’t question anyone on what I’m supposed to do because then they’ll learn that I’m a terrible writer”—ninth grader.

When asked to describe the most difficult parts of writing, the responses of high school students confirmed what many of us already know: writing can feel frustrating and overwhelming—sometimes so overwhelming that it feels paralyzing (Zumbrunn, 2015). Unfortunately, writing is not a task students can avoid. Writing is an important skill in many professions and fields of study. It is a powerful tool for communication, self-expression, and learning (Graham, 2006). In school settings, effective writing can also lead to improvements in reading comprehension (Hebert, Gillespie, & Graham, 2013), reading ability (Graham & Herbert, 2011), and overall academic achievement (Bangert-Drowns, Hurley, & Wilkinson, 2004). However, and as evidenced in the beginning quotes, writing is not an easy skill to master. The process of writing can be cognitively challenging for even experienced writers. Many students struggle with writing tasks as a result of lack of knowledge, ineffective methods, lack of planning, content generation, revisions, transcription, low persistence, and unrealistic self-efficacy (Santangelo, Harris, & Graham, 2007). The difficulties students have with writing are evident in the most recent U.S. national report of writing, which indicated that only 24 % of eighth and twelfth grade students scored at or above proficient in writing, and only 3 % of students performed at the advanced level (U.S. Department of Education, 2011).

Research over the last several decades suggests that feedback is one effective means to improve student writing (Ferris, 1997; Lizzio & Wilson, 2008). For instance, we know that feedback can foster students’ motivation for writing tasks (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Pajares, 2003; Schunk & Swartz, 1992) and improve their self-regulation while completing those tasks (Cleary & Zimmerman, 2004). Findings from a few existing studies suggest that students’ perceptions of writing feedback may be related to their writing motivation, self-regulation, and achievement (Ekholm et al., 2015; Magno & Amarles, 2011; Zumbrunn et al., 2013). Given the importance of writing for students and the challenges writing can present, it is important to understand students’ perspectives and the implications of their perspectives. As such, the current study explored the perceptions secondary school students have of writing feedback, and the relationship between student writing feedback perceptions, writing self-efficacy, and writing self-regulation aptitude.

Writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulation

Social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2001) posits that students’ beliefs about themselves and others have the power to influence their behavior and such actions often impact others within the classroom context. For example, self-efficacy, defined as the confidence one has about his or her ability to be successful in a particular domain (Bandura, 2006), is an important factor of social cognitive theory as it is a strong predictor of performance, effort, and perseverance (Pajares, 2003; Pajares & Miller, 1995). Students with higher self-efficacy beliefs typically participate more readily, put forth more effort, are more perseverant in the face of challenge, and are more academically successful than their peers with lower beliefs of efficacy (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2007). Higher self-efficacy beliefs are particularly important in cognitively demanding academic domains such as writing (Bruning et al., 2013). Decades of research show that writing self-efficacy, or one’s beliefs about their ability to write (Schunk & Swartz, 1992), impacts student writing success (Pajares, 2003; Schunk & Zimmerman, 2007). In fact, some suggest that writing self-efficacy is a more powerful predictor of success than writing aptitude or previous writing performance (Pajares, 2003). In a study with college students, Zimmerman and Bandura (1994) found strong relationships between students’ self-efficacy for writing and overall academic self-efficacy, grade attainment in a writing course, and personal goal setting. Conversely, verbal aptitude and level of writing instruction (i.e., participation in regular or advanced classes) were not related to the grades students earned in their writing courses (Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994).

Apart from self-efficacy, many other areas of writing difficulty for students relate to self-regulation (Graham & Harris, 2000). Zimmerman and Risemberg (1997) defined writing self-regulation as “self-initiated thoughts, feelings, and actions that writers use to attain various literacy goals” (p. 76). Self-regulation strategies that writers use to manage the writing process typically include goal setting, planning, self-monitoring, self-instruction, revising, and help seeking (Zimmerman, 2002). Such self-regulated behaviors help students stay on task while writing, and these processes are essential to developing proficiency for writing (Garcia-Sanchez & Fidalgo-Redondo, 2006).

Self-efficacy is a critical component of self-regulation (Bandura & Cervone, 1983). A recent study found that self-efficacy was correlated with both behavioral measures and neural indicators of self-regulation (Themanson, Pontifex, Hillman, & McAuley, 2011). Specifically, students who had higher self-efficacy beliefs were more likely to make adaptive changes to their performance on a task, which resulted in making fewer errors on subsequent trials. A later study revealed a more complex relationship between self-efficacy and self-regulation. Lee, Lee, and Bong (2014) investigated the structural relationship between self-efficacy, self-regulation, and grade goals for a sample of middle school students. Findings suggested that although self-efficacy predicted self-regulation, the relationship was mediated by students’ academic goals (Lee et al., 2014). In other words, the academic goals students set for themselves in part explained the relationship between self-efficacy and self-regulation. Likewise, several factors certainly play a role in the relationship between writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulation. Students’ perspectives of the feedback they receive about their writing is one such possible factor.

Students’ perceptions of feedback on writing

Students’ affective responses and openness to receiving feedback about their writing comprise their writing feedback perceptions (Zumbrunn et al., 2010). Students may exhibit a variety of writing feedback perceptions ranging from very positive to very negative. Many studies in this area have explored the differing views of feedback between instructors and students (Carless, 2006), barriers to the utility of feedback (Higgins, Hartley, & Skelton, 2001), the ways in which students use feedback (Poulous & Mahony, 2008), and students’ preferences for receiving feedback (Rowe, 2011). The complexity of the feedback process is a reoccurring theme across this work. To date, the majority of studies examining student perceptions of feedback stems from work with college student samples and does not specifically address student perceptions of the feedback they receive about their written work.

In an effort to better understand students’ openness to writing feedback, Ekholm et al. (2015) tested the mediational role of feedback perceptions in linking self-efficacy and self-regulation in writing. Students’ openness to receiving feedback about their writing partially mediated the relationship between students’ writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulation aptitude. This finding is consistent with that of Lee et al. (2014) suggesting the relationship between self-efficacy and self-regulation is not always direct. However, similar to much of the research on feedback perceptions, the model tested in Ekholm et al. (2015) was developed using a sample of college students. Students have experiences with writing and receiving feedback about their writing long before they enter college, and writing feedback perceptions may be different for students at different stages of their education and development. That is, perceptions of elementary and secondary school students may differ from those of college students. As such, the relationship between writing feedback perceptions, writing self-efficacy, and writing self-regulation might also be different for younger students. Given the number of K-12 students who struggle with writing, it is even more important to understand how these factors relate and have the potential to improve student writing success.

To begin to address this need, a recent qualitative study explored elementary students’ perceptions of writing feedback (Marrs et al., 2015). Findings indicated that a majority of students in grades 3 through 5 like receiving feedback about their writing from teachers. Students predominantly cited aspects related to improving their writing skills as reasons for their openness to receiving feedback. Students also indicated that feedback from their teachers prompted positive affective responses (e.g., “it makes me feel good”). However, a sizeable number of students disliked receiving feedback about their writing from teachers. Several believed that feedback often results in negative emotional responses (e.g., “it makes me feel dumb”). Findings also suggested that some students commonly fear criticism, judgment, and getting a bad grade. Others seemed to dislike feedback because they felt unconfident in their writing ability. Although this work provided more insight into the perceptions of writing feedback of a younger population, secondary school students may exude further differences in feedback perceptions, as they typically have had more experiences with writing and receiving writing feedback from their teachers, peers, and others.

The purpose of the present study was twofold. The primary purpose was to extend the findings of Ekholm et al. (2015). As their study was conducted in college classrooms, the results might not capture the relationships that exist between writing self-efficacy, writing self-regulation, and feedback perceptions among middle and high school students. Thus, we investigated the predictive and mediational roles of writing self-efficacy and writing feedback perceptions on student writing self-regulation aptitude with secondary school students. Similar to Marrs et al. (2015), the secondary purpose of this study was to hear the voices of our participants and deepen our understanding of student writing feedback perceptions. As such, we collected both quantitative and qualitative data using an explanatory sequential design (i.e., QUAN → qual) (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). The two sets of data gathered were intended to complement one another, leading to the development of more complex insights into the findings (Calfee & Sperling, 2010).

Methods

Participants and setting

Participants included 598 students in grades 6–10 across four schools in a large Southeastern school district. The sample consisted of both males (n = 306) and females (n = 292). Approximately 41 % of the students were African American, 35 % were European American, 18 % were Hispanic, 2 % were Asian, and fewer than 1 % were of Hawaiian/Pacific Island descent. Approximately 3 % of students identified with two or more ethnicities. Roughly 8 % of students received special education services, 8 % received gifted education services, 4 % received English Language Learner (ELL) services, and 23 % qualified for free or reduced lunch status. The sample was unified and common for both QUAN and qual strands of the study.

Data collection procedures

The current study is one component of a larger study examining elementary and secondary students’ perceptions of the writing process and themselves as writers. During the spring semester, all quantitative and qualitative data were collected using an online survey platform. To help ensure developmentally appropriate methodology, the prompt and all instructions were provided in written and audio formats within the online instrument. All students completed measures independently; however, classroom teachers across all grade levels made accommodations based on students’ individual needs (e.g., typing dictated responses).

Quantitative data sources

Modified versions of the scales used in Ekholm et al. (2015) were used to collect the quantitative data in the current study. Measures included the following scales: the Student Writing Feedback Perceptions Scale, the Writing Self-Efficacy Scale, and the Writing Self-Regulation Aptitude Scale.

Student Writing Feedback Perceptions Scale

The Student Writing Feedback Perceptions Scale (Ekholm et al., 2015), originally intended for college students, asks students to rate their feelings about the feedback they receive on their writing from others on a scale of 1 (Almost never) to 4 (Almost always). This scale was modified for the present study to be developmentally appropriate with K-12 writers. For example, all incidences of the word, “instructor” were changed to “teacher.” Additionally, as K-12 students report that they talk about their writing with people at home (Marrs et al., 2015), an item was added to address students’ perceptions of the feedback they receive about their writing from their family members. The adapted Student Writing Feedback Perceptions Scale consisted of six items. All items for this scale are available in “Appendix”.

Writing Self-Efficacy Scale

An adapted version of the Self-Efficacy for Writing Scale (SEWS; Bruning et al., 2013) was used to provide information about students’ beliefs about their writing abilities. The original SEWS consists of 16 total items. Based on the findings of factor analyses, the measure was reduced to nine items representing a single factor (Ekholm et al., 2015). Also in line with Ekholm et al. (2015), the scale range was reduced from 0–100 to 0–4. All items for this scale are available in “Appendix”.

Writing Self-Regulation Aptitude Scale

Similar to the Student Writing Feedback Perceptions Scale, the Writing Self-Regulation Aptitude Scale (Ekholm et al., 2015) was originally intended for college students. The scale asks students to rate their perceived self-regulative behaviors on a scale from 1 (Almost never) to 4 (Almost always). The scale assesses the self-regulated learning processes of goal setting, planning, self-monitoring, attention control, emotion regulation, self-instruction, and help-seeking for writing. For the current study, the items, “I make my writing better by changing parts of it” and “I tell myself I did a good job when I write my best,” were added to include the self-regulation processes of self-evaluation and self-imposed contingencies. Additionally, slight changes in language were made to the original items to ensure the developmentally appropriateness of the scale. The adapted Writing Self-Regulation Aptitude Scale consisted of twelve items. All items for this scale are available in “Appendix”.

Quantitative data analyses

Correlational analyses were first conducted to examine the relationships among student writing self-efficacy, writing feedback perceptions, and writing self-regulation aptitude. Next, a hierarchical regression analysis followed by a mediation analysis was conducted. To test for mediation, a significant relationship between writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulation aptitude was first established using simple linear regression. Simple linear regressions then were conducted to examine the effect of writing self-efficacy on writing feedback perceptions, and writing feedback perceptions on writing self-regulation aptitude. Finally, a multiple linear regression was conducted to determine the effect of writing feedback perceptions on writing self-regulation aptitude when controlling for writing self-efficacy beliefs. The Sobel test was used to examine the magnitude of the mediator.

Qualitative data sources

The online survey data collection format and the large sample limited the qualitative data for this study to one open-ended question. After responding “yes” or “no” to the closed-ended question, “Do you like to receive feedback about your writing?” students were branched to the appropriate follow-up open-ended question, “Why do/don’t you like to receive feedback about your writing from your teacher?” Qualitative data sources were replicative of the qualitative sources used in Ekholm et al. (2015).

Qualitative data analyses

An exploratory descriptive qualitative investigation (Sandelowski, 2000) was conducted to explore students’ experiences with receiving feedback about their writing. Data was divided to explore the reasons students did or did not like receiving feedback about their writing. Two sets of data were created: (1) students who reported liking writing feedback (answered “yes” to the closed-ended question, “Do you like to receive feedback about your writing?”), and (2) students who reported disliking writing feedback (answered “no” to the closed-ended question, “Do you like to receive feedback about your writing?”). Two readers independently reviewed all student responses, then met to discuss reoccurring patterns within the data. A conventional content analysis of each set of the qualitative data (i.e., liking writing feedback, not liking writing feedback) allowed the codes and names for codes to flow from the data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Constant comparative analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), whereby connections, contrasts, and comparisons between codes were explored, helped ensure that codes covered all data and were mutually exclusive. All codes were co-determined by both readers. Codes for liking/disliking writing feedback were then grouped into categories and subcategories to meaningfully organize the data (Patton, 2002). Following independent analyses, the two readers conferenced with each other to determine final coding of all data. All discrepancies were discussed and reconciled to 100 % agreement.

Similar to procedures followed in Marrs et al. (2015), a quantitative analysis of the qualitative data was conducted by converting the qualitative categorical data into numerical binary codes and analyzing this data statistically. Each student response received a binary score for each of the structural codes: 1 if the response aligned with the code, or 0 if the response did not align with the code. This numerical coding enabled an analysis of the frequencies for each structural code. Averages of binary scores equated the percentage of the proportion of the participants whose response aligned with each structural code. It is important to note that students often included several reasons for whether or not they liked receiving writing feedback in their responses. Accordingly, it was possible for each student response to align with multiple codes.

Mixed methods procedures

Iterative sequential mixed analysis (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009) of the data was used. That is, the quantitative analysis of the quantitative data was conducted before the qualitative and quantitative analyses of the qualitative data. The qualitative data was used to augment the quantitative findings. Findings from both the quantitative and qualitative phases were used to make final interpretations and conclusions.

Findings

Quantitative results

Table 1 provides means and standard deviations for scores on the Student Writing Feedback Perceptions Scale, the Self-Efficacy for Writing Scale, and the Writing Self-Regulation Aptitude Scale. Table 2 presents positive correlations among scores on the three scales. Writing self-efficacy, feedback perceptions, and self-regulation aptitude were moderately correlated, ranging from r = .476 to .555. A mediation regression analysis was conducted next.

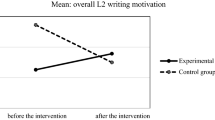

First, a significant relationship between writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulation aptitude was determined using simple linear regression (F 1,589 = 234.29, ρ < 0.001; r 2 = .29; β = 0.53). Writing self-efficacy accounted for approximately 29 % of the variation in student writing self-regulation beliefs. Next, writing self-efficacy was determined to have a significant effect on writing feedback perceptions (F 1,592 = 173.05, ρ < 0.001; r 2 = 0.23; β = 0.48), and accounted for 23 % of the variance in writing feedback perceptions. A significant relationship between writing feedback perceptions and writing self-regulation was then determined (F 1,591 = 262,066 ρ < 0.001; r 2 = 0.31; β = 0.56). After controlling for writing self-efficacy, writing feedback perceptions were positively related to writing self-regulation aptitude (F 2,588 = 195.51, ρ < 0.001; R 2 = 0.40; β = 0.39). Participants with more positive perceptions of feedback reported higher writing self-regulation aptitude than did participants with more negative feedback perceptions. Approximately 40 % of the variance in writing self-regulation aptitude was accounted for when including both writing self-efficacy beliefs and writing feedback perceptions as predictors. That is, writing feedback perceptions predicted a significant amount of variance over and beyond the variance accounted for by writing self-efficacy beliefs.

Writing feedback perceptions partially mediated the effect of writing self-efficacy beliefs on writing self-regulation aptitude. Using the Sobel test, the magnitude of the relation between writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulation aptitude significantly decreased with the inclusion of writing feedback perceptions (z = 8.35, ρ < .001). As Fig. 1 illustrates, the standardized regression coefficient between writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulation aptitude decreased substantially when controlling for writing feedback perceptions. Not shown in this model, however, are other possible factors that relate to students’ perceptions of writing feedback. From a practical perspective, a deeper understanding of the ways in which students perceive the writing feedback they receive from their teachers is especially important, as students report that they typically discuss their writing with their teachers more than with their peers or families (Zumbrunn & Bruning, 2011). To address this, our qualitative data further explored the reasons students provide for either liking or not liking writing feedback from their classroom teachers.

Qualitative findings

Significantly more students (n = 482) answered “yes” to the question, “Do you like to receive feedback about your writing” than those who answered “no” (n = 116). The following sections describe the primary reasons students provided for either liking or disliking writing feedback.

Why students like receiving feedback about their writing

Overall, student responses for liking writing feedback aligned with two overarching qualitative categories: “Mastery” and “Positive Affect.” See Table 3 for categories, subcategories, frequencies of student responses, and exemplar quotes. Approximately 15 % (n = 72) of the students who indicated that they like to receive feedback about their writing provided either an unrelated or non-response to the open-ended question.

Mastery

The Mastery category represented students’ appreciation for feedback as a means to improve their writing. This category included the subcategories of “General Improvement,” “Mistakes,” “Positive Aspects,” “Others’ Views,” and “Thinking Ahead.” Taken together, the Mastery subcategories represented nearly 80 % of positive student responses.

General improvement

The primary reason students provided for liking writing feedback was to improve their writing skills. Over a quarter (n = 129) of students’ responses aligned with this sub-category. Though the majority of student responses in this category were more general in nature and lacked specific detail, students seemed to recognize feedback as a mechanism for helping them become better writers. For example, an eighth grader commented that feedback helps her “get better at writing each time.” Another student wrote, “[Feedback] helps me do better and focus on my writing!” Some students reported that writing feedback can lead to improved products (e.g., “It helps me get a better story/essay”), while others noted that writing feedback can help them learn (e.g., “I like to receive feedback from my teacher about my writing because I can learn from their comments;” “[Teachers] can teach me something I did not know about and help me improve”).

Mistakes

Several (n = 114) students believed feedback is valuable when it identifies the mistakes they make in their writing. Responses in this category seemed to represent the critical nature of feedback. For example, many responses included the words, “fix,” “correct,” “weakness,” or “wrong.” A ninth grader commented, “I like to receive feedback because they let me know how bad I did on my assignment.” “I know that my writing may be wrong so I would like to be corrected,” responded another student. Several students noted the ways in which feedback helped them learn from their mistakes. One student wrote, “I want to know what I did wrong so I could learn from my mistakes.” Similarly, a high schooler commented, “I love knowing my mistakes then being able to change and learn [from] them.” Some students mentioned the specific types of feedback they receive. In particular, many students recalled receiving feedback on their spelling mistakes.

Positive aspects

Whereas student responses in the Mistakes sub-category seemed to highlight the value of feedback as a means to identify areas of students’ writing that required improvement, responses (n = 70) in this sub-category showed that some students were interested in receiving feedback that identifying areas of their writing that hit the mark. Many comments included the words, “good,” “strengths,” and “right.” An eighth grader noted, “I like when I receive feedback because it tells me what I’m good at.” Similarly, another student commented that feedback “tells me that I know what I’m doing, and I’m doing it right.” A few student responses in this sub-category were more specific. For example, a high school student wrote that she appreciates feedback “so that I know if my writing has good organization and if it reads well.”

Others’ views

Responses (n = 37) in this sub-category illustrated that students recognized the value of others’ opinions. Many students mentioned that feedback from others with more experience is especially valuable. For example, one student commented, “I’d rather have a teacher who has more experience look at my paoper [sic] than my classmates.” Other students highlighted the ways in which others can provide advice through feedback. One ninth grader wrote that her teachers “give good insight on what your paper needs to look like.” Another student noted that his teachers “have interesting ideas.”

Thinking ahead

Some students (n = 33) seemed to use feedback as a means to think ahead about their next draft or writing assignment. Nearly all responses in this sub-category included the phrases, “next time” or “future writing.” For example a ninth grader commented, “It helps me know what I need to work on so I can do better next time.” Another student replied that she liked feedback because it informs what she needs to “change for [her] next writing assignment.”

Positive affect

The Positive Affect category represented students’ positive experiences and emotions related to receiving feedback about their writing. This category included the subcategories of “Positive Emotion” and “Positive Experiences.” Taken together, the Positive Affect subcategories represented approximately 17 % of positive student responses.

Positive emotion

Feedback evoked positive emotions for several (n = 57) students. The words, “feel good” and “happy” were included among many responses in this sub-category. For example, a seventh grader commented, “[feedback] makes me feel good about my writing and myself.” Similarly, another student wrote that feedback “makes me feel better and makie [sic] my day.” Feedback made some students feel more confident in themselves as writers: “I like to receive feedback from my techer [sic] because it can boost my confidence and make me a better writer;” “It makes me feel more sure of myself;” and “It makes me feel like I was successful with the subject we had to write.” In addition, pride and strength seemed to be themes for a few writers. For example, a high school student recalled that feedback made him “feel better and strong.” For others, feedback evoked feelings of distinction. “It makes me feel special,” commented a seventh grader. Many students seemed to be encouraged and motivated by the feedback they receive from their teachers. One student recalled, “It makes me feel good about my work and makes me want to do it even better the next time.” “I like it because it pushes me to do better next time,” noted another student.

Positive experiences

Several students (n = 26) recalled positive experiences related to receiving feedback about their writing. The great majority of responses in this sub-category referred to the compliments students receive about their work. For example, a ninth grader noted, “I’ve really only ever been given pleasant feedback, and I enjoy hearing it.” Similarly, another student wrote, “It’s usually good feedback because I’m an awesome writer.”

Why students dislike receiving feedback about their writing

Two qualitative categories emerged for disliking writing feedback: “Disregard” and “Negative Affect.” See Table 4 for categories, subcategories, frequencies of student responses, and exemplar quotes. Approximately 16 % (n = 19) of the students who indicated that they did not like to receive feedback about their writing provided either an unrelated or non-response to the open-ended question.

Disregard

The Disregard category represented students’ disinterest or indifference to feedback—particularly negative feedback. This category included the subcategories of “General Disinterest,” “Negative Feedback,” and “Indifferent.” Taken together, the Disregard subcategories represented approximately 65 % of negative student responses.

General disinterest

The majority of students who reported a disinterest in receiving writing feedback (n = 38) gave little explanation for their preferences. “I just don’t” was a common response in this sub-category. Many students mentioned that they did not like writing in general. “I don’t like writing and [teachers] are really critical so I just say whatever and keep writing,” wrote a middle schooler. Others simply reiterated their disinterest in receiving writing feedback, “I don’t like people reading and commenting on my writing.” Some students commented that feedback was “annoying,” “boring,” or “dumb.”

Negative feedback

Several students (n = 21) seemed to expect negative feedback about their writing from their teachers. “I feel like they might respond with something bad,” wrote an eighth grader. Many students commented on the critical nature of feedback, “There are few commits [sic], and it’s always bad commits [sic]. Never good.” A few students expected especially harsh feedback, “[Teachers] might say u [sic] did awlful [sic] -_-.”

Indifferent

Responses (n = 16) in this sub-category illustrated the indifference some students have toward receiving feedback about their writing. The phrase, “don’t care,” was included in the majority of student comments in this sub-category. “I don’t really care what other people think,” wrote one freshman. Similarly, another student replied about his teachers, “I don’t care what they have to say about my writing.”

Negative affect

The Negative Affect category represented students’ negative emotions and experiences related to receiving feedback about their writing. Approximately 23 % of negative student responses aligned with this category. The majority of student responses classified in this category communicated that feedback evokes negative emotions. Negative emotions ranged from unhappiness (e.g., “If it’s bad, then it makes me feel bad :(”) to anxiousness (e.g., “It makes me nervous”), embarrassment (e.g., “I feel embarrassed”), and anger (e.g., “Sometimes their comments make me want to punch them”). Feedback seemed to make some students feel inadequate. For example, a sixth grader commented, “Sometimes my writing is terrible and it makes me feel like crap when it sucks.” “It makes me feel like I am really stupid,” wrote another student. A few students recalled the negative past experiences they’ve had with receiving feedback about their writing. For example a ninth grader wrote about his teachers, “They scould [sic] me about some of the things I write.” Similarly, another student noted, “Some of the teachers are mean.”

Discussion

The primary purpose of our study was to quantitatively investigate the predictive and mediational roles of writing self-efficacy and feedback perceptions on student writing self-regulation aptitude. Ekholm et al. (2015) found that feedback perceptions about writing partially mediated the relationship between student writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulation aptitude in college classrooms. This finding was replicated in our study using a sample of middle and high school students. Together, these findings support the critical role of writing feedback perceptions in linking students’ self-efficacy about writing to their writing self-regulation aptitude. If improving student writing self-regulation is a goal, then it becomes important to not only provide feedback on students’ writing, but also on their strategy use (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2007). Building on prior work that shows that feedback is most useful for students when they are willing to interact with it positively (Price, Handley, Millar, & O’Donovan, 2010), our findings suggest that improving both student writing self-efficacy and writing feedback perceptions has the potential to result in better student writing.

Although our quantitative results support the findings of Ekholm et al. (2015) and demonstrate the importance of students’ perceptions of writing feedback, they fall short of helping us understand the reasons underlying students’ openness to feedback. The second purpose of this study therefore aimed to expand what we know about student writing feedback perceptions. Similar to the findings with elementary students of Marrs et al. (2015), we found that many middle and high school students like to receive feedback about their writing. Students who indicated an openness to writing feedback cited justifications related to the personal mastery of writing skills or the positive feelings feedback can promote.

The largest subgroups of students liked to receive feedback on their writing because it helped them to improve their writing skills or to identify mistakes in their writing. Other students liked to receive feedback because it helped them to see aspects of their writing that were done well, while others liked it because it helped them understand the perspectives of others, including teachers and peers. These students made clear that they want to become better writers and see feedback as helpful and useful. Like many students in elementary school (Marrs et al., 2015), students in this study often did not identify specific ways in which feedback helps them to accomplish their writing goals. Regardless, this sense of motivation is encouraging, as such mastery motivation is often associated with positive academic outcomes, including achievement and self-efficacy (Meece, Anderman, & Anderman, 2006).

Differing from the feedback perceptions of elementary students in Marrs et al. (2015), a small subgroup of students recognized that feedback could help them with future assignments. This finding demonstrates that some students anticipate the need to keep feedback in mind for the future. Similar findings have been found with college students (Higgins et al., 2001). Developmentally, we would not necessarily expect elementary students to share this perspective, as older students typically are better able to plan than younger students (Huizinga, Dolan, & van der Molen, 2006).

Other responses students provided for liking writing feedback related to the positive affective responses it can prompt. For some, receiving feedback was associated with positive experiences. For others, feedback seemed to prompt positive emotional reactions such as feelings of happiness or pride. These students were clear that feedback makes them feel good about themselves and about their writing. Our study is not the first to find that some students associate very positive emotions with feedback (Marrs et al., 2015; Rowe, Fitness, & Wood, 2014). Rowe et al. (2014) asked college students to speak about their experiences with feedback and encouraged them to recall emotional experiences they had with receiving feedback. Students typically associated joy and happiness with feedback focused on their individual achievement. Interestingly, Rowe et al. (2014) also found that love was a major category that emerged from student responses. Students associated love with feedback because of the caregiving aspect associated with it. Students felt that feedback from instructors shows that their teacher appreciates and cares for them (Rowe et al., 2014). Findings from these studies provide evidence that some students associate receiving feedback with positive emotions, regardless of age.

Unfortunately, we know that not all students view writing feedback favorably (e.g., Marrs et al., 2015; Rowe et al., 2014). The responses from students who expressed a dislike for writing feedback illustrate the severity of several students’ negative experiences with receiving feedback. In fact, some students viewed feedback so negatively that they avoid receiving or reading it.

Students who disliked writing feedback responded in ways that suggested that they were uninterested in feedback on their writing or were indifferent to such feedback. This is a subtle but important distinction, as indifference did not emerge as a thematic category in the Marrs et al. (2015) study with younger students. Some students disinterested in writing feedback seemed to view their writing as their own and did not want the opinions of others. Conversely, students who were indifferent to feedback were adamant about not caring about the opinions of others. Whereas generally disinterested students seemed to be less interested in the feedback process as a whole, indifferent students seemed less interested in the content of writing feedback. It is possible that this distinction did not appear with elementary school-aged students because they were less able to fully articulate their feelings toward feedback.

Many students who disliked receiving feedback found it to be very critical, sometimes plainly stating that teachers rarely have anything good to say about their writing. A number of middle and high school students in this study also associated writing feedback with negative emotional responses, just as elementary aged children did in Marrs et al. (2015) and college students in Rowe et al. (2014). Furthermore, the emotions secondary school students mentioned were very similar to those of younger children: unhappiness, anxiety, embarrassment, and anger. Some students reported that feedback often makes them feel stupid or badly about themselves as writers or students in general. When providing students with feedback, it is possible for teachers to unintentionally write or say things that students readily interpret as comments about themselves rather than about their work, sometimes amplifying their existing feelings of self-doubt (Värlander, 2008).

Our qualitative findings reveal a range in explanations students provide for liking or disliking writing feedback. Many responses referred to students’ self-efficacy for writing as reasoning for their views of feedback, though not always directly. These qualitative findings support our quantitative results in that for some students, writing self-efficacy relates to their perceptions of feedback about their writing. If students are convinced that they are not adequate writers and are not open to receiving feedback about their writing, then taking the time to plan their writing projects or revise them regularly seems somewhat unlikely.

In line with studies with older students (Caffarella & Barnett, 2000), an inverse relationship seems to exist for students who like to receive feedback. Many students seemed to expect feedback on their writing to be complimentary. Often these students alluded to their beliefs of themselves as good writers. Some described that feedback from their teachers often makes them feel more confident and sure of themselves. Moreover, some students seemed to feel more motivated to write as a result of receiving feedback. For these students, their positive self-efficacy and feedback perceptions might result in increased writing self-regulation and, ultimately, better writing quality (Ekholm et al., 2015).

Although evidence suggests that writing self-efficacy is a possible predictor of writing feedback perceptions, other predictive factors certainly exist. Similar to elementary students in Marrs et al. (2015), not all student responses point to self-efficacy as a reason for liking or disliking feedback. These studies suggest that other factors contribute to the reasons underlying students’ writing feedback perceptions. Previous research has shown that students with more positive attitudes toward writing show higher writing achievement (Graham, Berninger & Fan, 2007). Perhaps student attitudes toward writing are also predictive of how students feel about the feedback they receive on their writing. This could be particularly applicable to the students who are disinterested in or indifferent to feedback.

Practical implications

Our findings suggest that students’ beliefs about their ability to accomplish certain writing tasks are related to their level of openness to receiving feedback. Thus, one way to encourage positive writing feedback perceptions in the classroom might be to focus on raising student efficacy beliefs about their writing. Mastery experiences—students’ personal experiences with success or failure—are critical sources of self-efficacy beliefs (Usher & Pajares, 2008). Giving students opportunities to recognize their own good writing and to chart their writing successes are ways to help students accurately track their positive mastery experiences in writing (Garcia & de Caso, 2006). Charting writing progress can also encourage students to be more self-regulated in their writing (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006).

Familiarizing students with the feedback process and its benefits through structured class activities may be another way to help students view feedback in a positive light (Rust, 2002). For example, teachers might begin the feedback process by describing how and why feedback will be given as well as providing students with detailed explanations of the meanings and implications of specific feedback on student work (Burke, 2009). Understanding the ways in which feedback can be useful for subsequent assignments may be difficult if writing tasks are very different from one another. Providing students with general writing feedback rather than feedback about specific content may be perceived as more useful by students (Higgins et al., 2001). The practice of peer-editing can also foster students’ understanding of feedback (Caffarella & Barnett, 2000). Wellington (2010) suggests that the reciprocity of both receiving and giving feedback can promote students’ positive attitudes toward feedback.

Perhaps the most straightforward way to encourage positive feedback perceptions in the classroom is to make time for conversations not only about the feedback students receive about their writing, but also how such feedback makes students feel. In her review, Värlander (2008) discusses the emotional challenges that can be associated with the feedback process. Rather than viewing these emotions as a barrier to learning, she suggests we shift our thinking to look at emotions as a natural part of the learning process. For students who have strong adverse reactions to feedback, Värlander (2008) suggests that “feedback-on-the-feedback” dialogues might be a way to reduce the negative emotions students sometimes associate with feedback.

Limitations and future directions

The design of this study has both benefits and limitations. Though the use of a developmentally-appropriate online survey made it possible to collect responses from hundreds of students across several classrooms and schools, the qualitative data collected in this study was limited to relatively brief replies in response to the open-ended questions posed to students. Future research including follow-up interviews or classroom observations would add to the richness of our understanding of student perceptions of writing feedback.

A second limitation to our study is that we relied on students’ self-reported responses of their writing self-regulation. Students might not always accurately recount how strategic they are in their writing. Even if students are able to accurately judge their writing self-regulation, they may be tempted to answer questions about it more favorably to appear “better.” Future research in this area should consider other ways of measuring student writing self-regulation. Such methods might include observations or teacher ratings of student self-regulation behaviors in the classroom.

The positive wording used for all scale items also presents a potential limitation. Though debated in the survey methodology literature, there is some evidence to suggest that interspersing the directionality of items on scales might mitigate “response set” patterns in which participants select their responses without reading the content of items (De Vaus, 2002).

Conclusions

The findings from the current study are a logical extension of the extant work in the area of writing feedback perceptions (Ekholm et al., 2015; Marrs et al., 2015; Caffarella & Barnett, 2000; Rowe et al., 2014). We combined and replicated the quantitative methods from Ekholm et al. (2015) and qualitative methods from Marrs et al. (2015) using a developmentally different sample of students. We believe that data gathered from each methodology provided distinct valuable information regarding students’ feelings about writing feedback, and that mixing the two approaches allowed us to gain greater depth in our understanding. Collectively, the results of this work begin to give a more complete picture of the diverse perceptions students have of writing feedback and the importance of writing feedback in linking writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulation aptitude.

References

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26.

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide to constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 307–337). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Bandura, A., & Cervone, D. (1983). Self-evaluative and self-efficacy mechanisms governing the motivational effects of goal systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 1017–1028.

Bangert-Drowns, R. L., Hurley, M. M., & Wilkinson, B. (2004). The effects of school-based writing-to-learn interventions on academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 29–58.

Bruning, R., Dempsey, M., Kauffman, D., McKim, C., & Zumbrunn, S. (2013). Examining dimensions of self-efficacy for writing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(1), 25–38.

Burke, D. (2009). Strategies for using feedback students bring to higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(1), 41–50.

Caffarella, R. S., & Barnett, B. G. (2000). Teaching doctoral students to become scholarly writers: The importance of giving and receiving critiques. Studies in Higher Education, 25(1), 39–52.

Calfee, R., & Sperling, M. (2010). On mixed methods: Approaches to language and literacy research. New York: Teachers College Press.

Carless, D. (2006). Differing perceptions in the feedback process. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 219–233.

Cleary, T. J., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2004). Self-regulated empowerment program: A school-based program to enhance self-regulated and self-motivated cycles of student learning. Psychology in the Schools, 41(5), 537–550.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

De Vaus, D. (2002). Surveys in social research. Abingdon, Oxforshire: Routledge.

Ekholm, E., Zumbrunn, S., & Conklin, S. (2015). The relation of college student self-efficacy toward writing and writing self-regulation: Writing feedback perceptions as a mediating variable. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(2), 197–297.

Ferris, D. R. (1997). The influence of teacher commentary on student revision. TESOL Quarterly, 31(2), 315–339.

Garcia, J. N., & de Caso, A. M. (2006). Changes in writing self-efficacy and writing products and processes through specific training in the self-efficacy beliefs of students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 4(2), 1–27.

Garcia-Sanchez, J. N., & Fidalgo-Redondo, R. (2006). Effects of two types of self-regulatory instruction programs on students with learning disabilities in writing products, processes, and self-efficacy. Learning Disability Quarterly, 29(3), 181–211.

Graham, S. (2006). Writing. In P. Alexander & P. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 457–478). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Graham, S., Berninger, V., & Fan, W. (2007). The structural relationship between writing attitude and writing achievement in first and third grade students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32(3), 516–536.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2000). The role of self-regulation and transcription skills in writing and writing development. Educational Psychologist, 35(1), 3–12.

Graham, S., & Herbert, M. (2011). Writing to read: A meta-analysis of the impact of writing and writing instruction on reading. Harvard Educational Review, 81(4), 710–744.

Hebert, M., Gillespie, A., & Graham, S. (2013). Comparing effects of different writing activities on reading comprehension: A meta-analysis. Reading and Writing, 26(1), 111–138.

Higgins, R., Hartley, P., & Skelton, A. (2001). Getting the message across: The problem of communicating assessment feedback. Teaching in Higher Education, 6(2), 269–274.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

Huizinga, M., Dolan, C. V., & van der Molen, M. W. (2006). Age-related change in executive function: Developmental trends and a latent variable analysis. Neuropsychologia, 44, 2017–2036.

Lee, W., Lee, M. J., & Bong, M. (2014). Testing interest and self-efficacy as predictors of academic self-regulation and achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39(2), 86–99.

Lizzio, A., & Wilson, K. (2008). Feedback on assessment: Students’ perceptions of quality and effectiveness. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(3), 263–275.

Magno, C., & Amarles, A. (2011). Teachers’ feedback practices in second language academic writing classrooms. The International Journal of Education and Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 21–30.

Marrs, S., Zumbrunn, S., Mewborn, C., & Stringer, J. K. (2015). Exploring elementary student perceptions of writing feedback. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Meece, J. L., Anderman, E. M., & Anderman, L. H. (2006). Classroom goal structure, student motivation, and academic achievement. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 487–503.

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218.

Pajares, F. (2003). Self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, and achievement in writing: A review of the literature. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 139–158.

Pajares, F., & Miller, M. D. (1995). Mathematics self-efficacy and mathematics performances: The need for specificity of assessment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(2), 190.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Poulos, A., & Mahony, M. J. (2008). Effectiveness of feedback: The students’ perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(2), 143–154.

Price, M., Handley, K., Millar, J., & O’Donovan, B. (2010). Feedback: All that effort, but what is the effect? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(3), 277–289.

Rowe, A. (2011). The personal dimension in teaching: Why students value feedback. International Journal of Educational Management, 25(4), 343–360.

Rowe, A. D., Fitness, J., & Wood, L. N. (2014). The role and functionality of emotions in feedback at university: A qualitative study. The Australian Educational Researcher, 41(3), 283–309.

Rust, C. (2002). The impact of assessment on student learning how can the research literature practically help to inform the development of departmental assessment strategies and learner-centred assessment practices? Active Learning in Higher Education, 3(2), 145–158.

Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23, 334–340.

Santangelo, T., Harris, K. R., & Graham, S. (2007). Self-regulated strategy development: A validated model to support students who struggle with writing. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 5(1), 1–20.

Schunk, D., & Swartz, C. (1992). Goals and feedback during writing strategy instruction with gifted students. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco.

Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2007). Influencing children’s self-efficacy and self-regulation of reading and writing through modeling. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 23, 7–25.

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (Eds.). (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

Themanson, J. R., Pontifex, M. B., Hillman, C. H., & McAuley, E. (2011). The relation of self-efficacy and error-related self-regulation. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 80(1), 1–10.

U.S. Department of Education. (2011). Writing 2011: National Assessment of Educational Progress at grades 8 and 12. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Education Science.

Usher, E. L., & Pajares, F. (2008). Sources of self-efficacy in school: Critical review of the literature and future directions. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 751–796.

Värlander, S. (2008). The role of students’ emotions in formal feedback situations. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(2), 145–156.

Wellington, J. (2010). More than a matter of cognition: An exploration of affective writing problems of post-graduate students and their possible solutions. Teaching In Higher Education, 15(2), 135–150.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Bandura, A. (1994). Impact of self-regulatory influences on writing course achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 31, 845–862.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Risemberg, R. (1997). Becoming a self-regulated writer: A social cognitive perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22(1), 73–101.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (Eds.). (2007). Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and applications. New York: Routledge.

Zumbrunn, S. (2015). The most difficult parts of writing. Unpublished raw data.

Zumbrunn, S., & Bruning, R. (2011, December). Do conversations about writing matter? The relationship between elementary students’ writing conversations and writing beliefs, perceptions, and success. Paper presented at the Literacy Research Association Annual Meeting, Jacksonville.

Zumbrunn, S., Conklin, S., Varier, D., Turner, A., & Dumke, E. (2013, April). Self-efficacy is only part of the story: The role of feedback perceptions on student writing self-regulation. Poster presented at the American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco.

Zumbrunn, S. K., Bruning, R. H. Kauffman, D. F., & Hayes, M. (2010, April). Explaining determinants of confidence and success in the elementary writing classroom. Poster presented at the American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, Denver.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Virginia Commonwealth University Presidential Research Incentive Program and the Virginia Commonwealth University Foundation Langshultz Fund. The authors would like to thank Chesterfield County Public school district, the teachers, and the students who participated in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix: Scale items

Appendix: Scale items

Student Writing Feedback Perceptions Scale

-

I like talking with my teachers about my writing.

-

I like it when my classmates comment on my writing.

-

I like it when teachers comment on my writing.

-

I feel good about teachers’ comments about my writing.

-

I feel good about my classmates’ comments about my writing.

-

I feel good about my family members’ comments about my writing.

Self-Efficacy for Writing Scale

-

I can spell my words correctly.

-

I can write complete sentences.

-

I can punctuate my sentences correctly.

-

I can think of many ideas for my writing.

-

I can put my ideas into writing.

-

I can think of many words to describe my ideas.

-

I can concentrate on my writing for a long time.

-

I can avoid distractions when I write.

-

I can keep writing even when it is difficult.

Writing Self-Regulation Aptitude Scale

-

Before I start writing, I plan what I want to write.

-

Before I write, I set goals for my writing.

-

I think about who will read my writing.

-

I think about how much time I have to write.

-

I ask for help if I have trouble writing.

-

While I write, I think about my writing goals.

-

I keep writing even when it’s difficult.

-

While I write, I avoid distractions.

-

When I get frustrated with my writing, I make myself relax.

-

While I write, I talk myself through what I need to do.

-

I make my writing better by changing parts of it.

-

I tell myself I did a good job when I write my best.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zumbrunn, S., Marrs, S. & Mewborn, C. Toward a better understanding of student perceptions of writing feedback: a mixed methods study. Read Writ 29, 349–370 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9599-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9599-3