Abstract

This study examined the relative contribution of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness to literacy skills and the relationship between letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness, using data from Korean-speaking preschoolers. The results revealed that although both letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness made unique contributions to literacy skills (i.e., word reading, pseudoword reading, and spelling), letter-name knowledge played a more important role than phonological awareness in literacy acquisition in Korean. Letter-name knowledge explained appreciably greater amount of variance and had larger effect sizes in literacy skills. Furthermore, children with greater syllable, body (e.g., segmenting cat into ca-t), and phoneme awareness had higher levels of letter-name knowledge. In particular, children’s syllable awareness and body awareness were positively associated with their letter-name knowledge, even after controlling for children’s phoneme awareness. These results suggest that Korean children’s awareness of larger phonological units (i.e., syllable and body) in addition to phoneme awareness may mediate the relationship between letter-name knowledge and literacy acquisition in Korean, in contrast with previous findings in English that have demonstrated a positive relationship only between phoneme awareness and letter-name knowledge, and the hypothesis that phoneme awareness mediates the relationship between letter-name knowledge and literacy acquisition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children’s letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness are the two important predictors of subsequent literacy acquisition for children learning to read in alphabetic languages (Adams, 1990; Lonigan, Burgess, & Anthony, 2000; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998; Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998). Despite clear evidence of the importance of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness for literacy acquisition, however, the relative importance of these two important skills to children’s literacy acquisition has rarely been investigated explicitly, particularly in a language other than English. In addition, evidence in English is inconsistent. Some studies have shown a somewhat larger effect of letter-name knowledge on word reading skills (see Scarborough, 1998) while others have shown a similar or larger effect of phonological awareness (Lonigan et al., 2000; Muter, Hulme, Snowling, & Stevenson, 2004).

Furthermore, it is important to examine the interrelationship between letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness themselves in order to understand how these two important skills help establish the alphabetic principle. Previous studies in English suggest that these two skills are positively related, and some scholars have even argued that letter-name knowledge may be causally related to the emergence of phoneme awareness (Foulin, 2005; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1994). However, studies in other languages are necessary to examine the wider generalizability of these findings (Foulin, 2005; Treiman & Kessler, 2003). The present study contributes to filling this gap in the literature using data on the language and literacy skills of young Korean-speaking children.

Data on Korean-speaking children are particularly helpful for illuminating the relative contribution of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness to literacy skills and for investigating the hypothesized relationship between letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness. First, letter names in Korean differ from those in English in the systematicity of their phonological patterning and in the transparency of the relationship between the letter names and their corresponding sound values. Second, the Korean language has different phonological and phonotactic structures than English, which result in differences in the salient instrasyllabic phonological units for Korean-speaking, as compared to English-speaking children (Kim, 2007, in press; Yoon & Derwing, 2001). Furthermore, while the Korean language has an alphabetic writing system called Hangul (thus letters represents phonemes), Hangul is also syllabic such that letters are composed in syllable blocks rather than in a linear horizontal string as in English. For example, a two syllable word, /t∫ek-sang / a desk, is written in two syllable blocks, 책상, instead of a linear string of letters (i.e., ㅊ ㅐ ᄀ ㅅ ㅏ ㅇ). The two goals for this study were: (1) to estimate and compare the magnitude and direction of the effects of children’s letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness on their literacy skills in Korean and (2) to examine the relationship between children’s letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness in Korean.

Background and context

Many studies have demonstrated the importance of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness for children’s literacy acquisition. Children’s letter-name knowledge is found to be consistently and positively related to their literacy achievement in several, diverse languages with alphabetic writing systems, including English (Blatchford & Plewis, 1990; Muter, Hulme, Snowling, & Stevenson, 2004; Treiman & Kessler, 2003; Treiman, Tincoff, Rodriguez, Mouzaki, & Francis, 1998; Vellutino & Scanlon, 1987), German (Na̎slund & Schneider, 1996), Turkish (Oney & Durgunoglu, 1997), Dutch (de Jong & van der Leij, 1999), Hebrew (Levin, Patel, Margalit, & Barad, 2002; Levin, Shatil-Carmon, & Asif-Rave, 2006; Share, 2004), Latvian (Sprugevica & Hoien, 2003), and Korean (Kim, 2007). Furthermore, children’s phonological awareness contributes positively to literacy skills. For example, in English and German, children who have highly developed rime awareness and phoneme awareness tended to have higher achievement in their word reading and spelling (Bryant, MacLean, Bradley, & Crossland, 1990; Byrne & Fielding-Barnsley, 1993; Dixon, Stuart, & Masterson, 2002; Goswami, 1991; Goswami & Mead, 1992; Na̎slund & Schneider, 1996; Treiman & Zukowski, 1991). In addition, in languages that have clear syllable boundaries such as Greek, Norwegian, and Korean, children’s syllable awareness is positively related to their literacy acquisition (Aidinis & Nunes, 2001; Cho & McBride-Chang, 2005; Hoien, Lundberg, Stanovich, & Bjaalid, 1995).

Relative contribution of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness to literacy acquisition

Share, Jorm, Maclean and Matthews (1984) found a strong relationship between phonological awareness, phoneme awareness in particular, and word reading skills such that children’s phoneme awareness explained a substantial amount of the variability in word reading (39%) while letter-name knowledge explained only a small amount of additional variability (5%) after accounting for phoneme awareness, letter copying, and gender. However, although this previous study has demonstrated the existence and estimated the strength of the relationships of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness to literacy skills, the relative sizes of the effects of these two skills on literacy skills achievement are less clear. Note that the predictor that explains the largest amount of variability in the outcome may not necessarily have the largest effect size (Azen & Budescu, 2003). The evidence on effect sizes of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness in English shows a somewhat mixed picture: while a meta-analysis of estimated bivariate relationships found a larger effect of letter-name knowledge (with a median bivariate correlation coefficient of .53) than of phonological awareness (.42) on word reading skills (Scarborough, 1998), regression analyses showed a similar or larger effect of phonological awareness on literacy skills (Lonigan et al., 2000; Muter, Hulme, Snowling, & Stevenson, 2004). Lonigan and his colleagues (2000), using structural equation modeling, found a larger impact of phonological awareness (composite of rime and phoneme awareness) than letter-name knowledge on word reading for English-speaking children. In contrast, Muter et al. (2004), also using structural equation modeling, showed similar effect sizes for the impact of phoneme awareness and letter-name knowledge on word reading skills, after controlling for children’s prior word reading skills. Although these somewhat inconsistent results in these previous studies with English-speaking children are likely to be due to different control variables included in these studies, these results suggest that the magnitude of phonological awareness, phoneme awareness in particular, may be similar to that of letter-name knowledge, or if there is a difference, the difference may not be very large.

Although these studies in English are informative, these do not tell us whether the impact of children’s letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness on literacy skills differs across languages that exhibit different letter naming systems. In particular, if letter names have highly consistent phonological patterning and transparent cues for letter sounds as in Korean, then letter-name knowledge may play a more important role than phonological awareness in assisting children to understand the alphabetic principle. This question not only has a theoretical importance, but also has an important practical bearing on Korean children’s early literacy instruction because, depending on the relative importance of these two skills, classroom instruction can be modified strategically. For example, if letter-name knowledge is found to play a much larger role in literacy acquisition in Korean, then Korean children would benefit from more emphasis on systematic instruction around letter names as well as instruction on phonological awareness—Currently explicit and systematic instruction on both aspects are lacking in early literacy education in Korea.

Characteristics of letter names of English and Korean

The majority of letter names in English and Korean contain phonemes represented by the lettersFootnote 1 (e.g., letter name b includes the phoneme /b/ along with an additional vowel /i/). However, English and Korean letter naming conventions differ in two critical ways. First, the phonological patterning of letter names is less consistent in English than in Korean. In English, 12 consonants have CV names in which the initial phoneme represents the letter values (i.e., b, c, d, g, j, k, p, q, t, v, z, y), and 7 consonants have VC letter names in which the final phoneme represents the letter values (i.e., f, l, m, n, r, s, x). Two consonant names do not even contain the letter sounds (e.g., h, w). In contrast, in Korean the part of the letter name that indicates the letter sound is perfectly consistent, all but two of the single consonant namesFootnote 2 have CV.VC (C/ɪ/./ɨ/Footnote 3C) letter names, and the consonant in the C/ɪ/ syllable contains the sound value in the onset position while the consonant in the /ɨ/C syllable contains the sound value in the coda position. The systematic cues at the beginning and end of a letter name are important for Korean children because many consonants in Korean have different sounds in the onset vs. coda position due to coda neutralizationFootnote 4 (see Kim, 2007).

The second difference between English and Korean letter names lies in the degree of transparency that exists in the relationship between the letter names and letter sounds. In English, several letters represent multiple sounds, but letter names use only one of those sounds (e.g., letter name for c /si/ is applied to celery but not to cat or chat; Treiman & Kessler, 2003). In particular, this lack of transparency is even more severe in the letter names for vowels in English, which makes it hard for children to connect letters for vowel sounds (e.g., the letter name for a in English is applied to b a ke, but not to b a t and w a ll; Stuart & Coltheart, 1988). In Korean, however, there is an invariant one-to-one relationship between letter names and sounds. Names for the vowel letters in Korean represent the sound value of each vowel, and those values are applied to spellings in a perfectly consistent manner.

Phonological characteristics of Korean

Korean is a syllable-timed language and syllables are salient in oral language (Kim, 2007). Furthermore, while English-speaking children tend to segment a syllable into its onset and rime (e.g., segmenting can to c-an; Treiman, 1983, 1985, 1992; Treiman & Zukowski, 1991), evidence indicates that Korean-speaking children tend to segment a syllable into its body and coda (e.g., segmenting can to ca-n; Kim, 2007, in press; Yoon & Derwing, 2001). A recent longitudinal study showed that age-trajectories of Korean children’s body awareness began at a higher elevation and grew at a more rapid rate than did their age trajectories of rime awareness, suggesting that Korean monolingual children find the body unit more accessible than the rime unit (Kim, in press).

Relationship between phonological awareness and letter-name knowledge

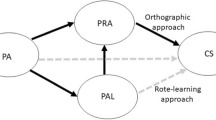

Another important question in understanding the roles of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness in literacy acquisition is to understand how children’s phonological awareness and letter-name knowledge are interrelated in order to help establish the alphabetic principle. Previous studies have shown that children with greater letter-name knowledge exhibit higher levels of phonological awareness, phoneme awareness in particular (see Foulin, 2005 for a review). Among several speculations offered to explain this positive relationship, the primary hypothesis—which has received much attention and some empirical support—states that knowledge of letter-names is required for, or causally influences, the emergence of children’s phoneme awareness (Foulin, 2005; Wagner et al., 1994). It is argued that the relationship between children’s letter-name knowledge and literacy acquisition is mediated by their letter-sound knowledge (see Share, 2004), which in turn is mediated by their phonemic awareness. According to this hypothesis, the key to the induction of letter-sound relations from letter names is the mediating role of phoneme awareness (Ehri, 1983). Many studies in English have demonstrated the hypothesized concurrent and lagged positive associations between children’s letter-name knowledge and phonemic awareness (Burgess & Lonigan, 1998; Chaney, 1994; Evans, Shaw, & Bell, 2000; McBride-Chang, 1999). Furthermore, a positive relationship has been reported between children’s letter-name knowledge and phoneme awareness, even after controlling for their rime awareness (Johnston, Anderson, & Holligan, 1996).

In contrast to the prominent relationship with phoneme awareness, children’s letter-name knowledge does not appear to be associated with their syllable awareness or rime awareness in English. Letter-name knowledge at preschool did not predict English-speaking children’s rime awareness in kindergarten (Burgess & Lonigan, 1998). In addition, Na̎slund and Schneider (1996) found that German-speaking children were able to perform syllable and rime awareness tasks even when they exhibited low letter-name knowledge. These results were taken to hypothesize that letter-name knowledge may be necessary only for a more advanced level of phonological awareness (i.e., phoneme awareness), but not necessary for more rudimentary phonological awareness (i.e., syllable awareness and rime awareness) (Bowey, 1994; Burgess & Lonigan, 1998; Foulin, 2005; MacLean, Bryant, & Bradley, 1987). Although many studies in English support the hypothesis of children’s phoneme awareness, but not syllable or rime awareness, as the sole mediator between letter-name knowledge and literacy acquisition, this relationship may simply reflect idiosyncratic characteristics of phonological structures and letter names in English. That is, in English, letter names provide children with less consistent and less clear cues for letter sounds, so that enhanced phoneme awareness may be required for English-speaking children to understand the alphabetic principle. To date, it is not clear empirically whether phonemic awareness solely and completely mediates the relationship between letter-name knowledge and literacy acquisition in a language that has a different phonological structure and patterns of letter names than English.

Early literacy instruction in Korea

In Korea literacy instruction usually begins in preschool/kindergarten and children are expected to have acquired fundamental literacy skills before entering elementary school (kindergarten is not part of formal education). The predominant approach to early literacy instruction in Korea since late 90’s is whole language or whole word instruction in which a whole word is presented to children as a unit (Kim, 2007). The researcher’s informal observations and consultation with teachers and directors of the preschools that participated in the present research study confirmed this. No explicit and systematic instruction of the alphabetic principle including letter names and phonological awareness was observed in the classrooms of the participating preschools. Letter names were incidentally and individually introduced to children as needs arise (e.g., when teachers needed to correct children’s incorrect copying of letters in a syllable or word).

Present study

In sum, the goal of this study was to investigate the relative importance of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness in literacy acquisition in Korean. The following were specific research questions:

Research question 1

Do children who display higher levels of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness tend to have better literacy skills (i.e., word reading, pseudoword reading, and spelling) in Korean? If so, which is more important?

Research Question 2

Do children with higher levels of letter-name knowledge exhibit more sophisticated phonological awareness among Korean-speaking children at the beginning of their literacy acquisition? Do Korean children with higher levels of letter-name knowledge exhibit higher phonemic awareness, after controlling for children’s background characteristics (i.e., age and gender) and syllable awareness and body awareness?

Research design

Sites and sample

Data were collected in four preschools in two metropolitan cities, two preschools in each city, in South Korea. The participants in this study were a sample of 184 four- and five-year-old Korean monolingual preschoolers in South Korea (mean age = 61 months, ranging from 50 to 75 months). Approximately 55 percent of the sample children (n = 102) were female. Teachers at each site reported no hearing or visual difficulties for any of the sampled children.

Procedures

The researcher, and four research assistants, administered all instruments to participants. The researcher trained the research assistants, including two graduate students in early childhood development and two child educators, to administer the measures. The assessment battery was administered approximately two months after the academic year began. Participating children were assessed individually in a quiet room, in two sessions of approximately 30 minutes each. The spelling task was group-administered. For each child, the order of administration of the measures was randomized in order to eliminate systematic fatigue effects.

Measures

Because standardized instruments to measure language and literacy skills in Korean were not available, all instruments used in the study were developed and piloted by the researcher, based on instruments that had been used in studies conducted in English (see Kim, in press for details about the pilot study). The internal consistency reliability of each measure was estimated using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics on each measure.

Literacy skills

Word reading. This task measures children’s ability to read real words in Korean. The measure contains 60 high frequency real words of increasing difficulty, each of which the child was asked to read aloud. Each item was scored dichotomously (i.e., right or wrong) to provide a total maximum score of 60. Children were able to read about 22 words correctly, on average, but there was substantial variation (SD = 23.22) around this average (see Table 1). In addition, children’s word reading scores were calculated by counting the number of letters that were read correctly. For example, the child who received a 0 score in the conventional dichotomous scoring for reading /nore/ as /nora/ was given three points for correctly reading the three letters. Table 1 displays descriptive statistics using this alternative scoring. It should be noted, however, that this alternative scoring essentially did not change children’s rank order in their word reading skills (r = .99) and the results of subsequent analyses. Cronbach’s alpha was estimated to be .98, for this measure, indicating extremely strong internal consistency of children’s responses.

Pseudoword reading. This task measures children’s skills in decoding; pseudowords were used to reduce the effect of visually memorized words. Fifty pseudowords of increasing difficulty were created based on Korean phonotactic rules (rules of allowable sound sequences). Each item was scored dichotomously to provide a total maximum score of 50. Children were able to read approximately 12 pseudowords, on average, with large variation (SD = 16.64), showing some floor effect. Again, children’s pseudoword reading scores were recalculated by counting the number of letters that were read correctly (see Table 1) and as in the word reading, the correlation between the two scoring methods was extremely high (r = .99). Cronbach’s alpha was estimated to be .98 for this measure, again indicating extremely strong internal consistency of children’s responses.

Spelling. This task assesses child’s ability to spell words (encode sounds graphically). It included 16 real words and 4 pseudowords. The conventional dichotomous scoring with a total maximum of 20 yielded a floor effect on the spelling task (M = 2.83, SD = 3.76) with about 43 percent of the children (n = 79) scoring zero. Alternatively, children were given credit for each letter spelled correctly (see Table 1). That is, a random string of no phonetically related letters (or phonetically and conventionally correct spell words, but not the words asked to spell), or no attempt was given a 0 point while any single conventionally correct letter was given one point. Any single phonetically correct letter, but not a conventional letter, was given a half point (e.g., using ㅔ for ㅐ for /ɛ/ phoneme). For the four nonwords, any phonetically correct spellings were given full credits. The correlation between dichotomous scoring and alternative scoring was high (r = .92). Cronbach’s alpha was estimated to be .73, for this measure, indicating moderately strong internal consistency among children’s responses.

Because the results using dichotomous scoring and alternative scoring did not differ, results reported in this article are based on dichotomous scoring.

Phonological awareness

“Oddity” tasks were to measure children’s syllable awareness, body awareness, and phoneme awareness, respectively. In these tasks, children were asked to select the odd word (word that has a different sound in the target phonological unit) from among three words. In order to reduce the memory burden, corresponding pictures were presented for each word. Directions for these tasks were presented orally. Children were asked to repeat each stimulus word to ensure their correct perception of the items. Each task had two practice items (phoneme awareness task had three practice items) and 15 test items. Children received feedback and explanations on their responses for the practice items. For the first two test items, correct answers were provided without feedback. Answers and feedback were not provided for the other 13 test items. Each item was scored dichotomously to provide a total maximum score of 15 in each task. The reliability estimates (Cronbach’s alpha) were .90 for the syllable awareness task, .89 for the body awareness task, and .87 for the phoneme awareness task, each demonstrating strong internal consistency reliability.

In the syllable awareness task, the child was asked to select the word that has a different beginning sound in the syllable among three words (e.g., /hu.t∫u/, /mo.ca/, /mo.rε/; /saŋ.ca/, /t∫ɪm.dε/, /saŋ.t∫u/). All the items consisted of two-syllable words. Children’s mean performance on the syllable awareness task was 6.76, but there was large variation around this average (SD = 4.62).

In the body awareness task, the child was asked to select one word that has a different sound in the body among three words (e.g., /kaŋ/, /kam/, /tul/). The first 10 items consisted of monosyllabic CVC words while the last 5 items consisted of two-syllable words. Children’s mean performance on the body awareness task was 6.50, with large variation around the average (SD = 4.50).

In the phoneme awareness task, the child was asked to select one word that has a different sound in the beginning phoneme among three words (e.g., /ki/, /ko/, /sɛ/). The first five items consisted of CV monosyllabic words while the rest of the 10 items consisted of CVC monosyllabic words. The CV monosyllabic words were included in order to reduce the difficulty of the task and minimize any floor effect. Nonetheless, children’s performance on the phoneme awareness task showed floor effect with a mean of 3.10 (SD = 3.62). Approximately 32% of the children (n = 59) scored zero in this task.

Although oddity tasks have often been used in the investigation of phonological awareness in English (e.g., Bradley & Bryant, 1985; Goswami, Ziegler, & Richardson, 2005), there are cautionary notes in the literature about using the oddity task as a measure of phonological awareness, particularly regarding a potential problem of low reliabilities. Literature presents some mixed picture on this as some studies reported low reliabilities of oddity task measurement (Hulme et al., 2002; Schatschneider, Francis, Foorman, Fletcher, & Mehta, 1999) and others finding reasonable reliability and high loading to phonological awareness (Muter et al., 2004). In the present study, the internal-consistency reliability of the items for each oddity task, estimated by Cronbach’s alpha, is reasonably high (ranging from .85 to .90). See Appendix A for more details on the results and decisions made in the phonological awareness tasks based on a pilot study.

Letter-name knowledge

The letter-name knowledge measure contained all the 40 Korean letters (21 vowel letters—10 simple and 11 complex vowels—and 19 consonant letters; see Appendix B) which were randomly arranged. Children were asked to say the name of each letter. Each item was scored dichotomously to provide a total maximum score of 40. Children in the sample knew about 15 letter names, on average, with large variation around the average (SD = 11.05). Cronbach’s alpha was estimated to be .96 for this measure, indicating extremely strong internal consistency of children’s responses.

Control predictors

Children’s gender and age were included as control variables. The child’s gender was represented by a dichotomous predictor that indicated whether the child was female (1 = female; 0 = male). Children’s age was in months.

Data analyses

To address the first research question, both the strength (i.e., amount of variance explained in the outcome) and magnitude (i.e., effect sizes) of the relationships of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness with literacy skills were examined. For each of the relationships, the amount of variability in children’s literacy skills explained by their letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness, respectively, was estimated after controlling for their age and gender. Two taxonomies of hierarchical regression models were fitted. In both series, control predictors were entered into the model in the first step. In the first taxonomy of models, children’s awareness of each phonological unit was entered as a predictor into the model in the second step, while children’s letter-name knowledge was entered into the model in the third step (see the bottom panel of Table 3). In the second taxonomy of models, letter-name knowledge was entered as a predictor into the model in the second step, while children’s awareness of three phonological units was entered in the third step (see the top panel of Table 3). These two taxonomies of fitted models allowed us to estimate the variability explained in each literacy outcome by letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness, respectively, before and after controlling for each other in addition to age and gender.

In addition, dominance analysis was conducted in order to confirm the relative importance of predictors in OLS regression models (Azen & Budescu, 2003; Budescu, 1993). Although the amount of variability explained by phonological awareness and letter-name knowledge in hierarchical regression reveals the amount of variability explained by each predictor in each step, dominance analysis provides more accurate and summary estimates of the R 2 values for all possible subset models in the contexts of selected predictors, accounting for the correlations between predictors (see Schatschneider, Fletcher, Francis, Carlson, & Foorman, 2004 for an application of dominance analysis). If the results from dominance analysis show that one variable is dominant over others, then the zero-order relationship as well as the mean semipartial and partial correlation of the dominant variable with the outcome variable is greater than the relationship of the other variable to the outcome variable.

Subsequently, the relative sizes of the effects of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness on each literacy outcome were estimated using regression analysis, after controlling for children’s age and gender. From the fitted regression models, the effect sizes were estimated by multiplying the appropriate parameter estimate by the respective standard deviation. Thus, for example, the effect size of letter-name knowledge on real word reading represents the number of words in the word reading task associated with a one standard deviation difference in letter-name knowledge.

To address the second research question, taxonomies of multiple regression models were fitted to examine the extent to which inter-individual differences in children’s letter-name knowledge is associated with their phonological awareness outcomes (i.e., syllable, body, and phoneme awareness), after accounting for selected control predictors (age and gender). In each taxonomy, these covariates were entered into the model in the first step. In the second step, children’s awareness of phonological units other than the outcome phonological awareness was entered as a predictor into the model. In the third step, letter-name knowledge was entered into the model. For example, when the outcome was syllable awareness, body and phoneme awareness were entered as predictors into the model in the second step. Thus, if the effect of children’s letter-name knowledge was statistically significant and positive in the third step, this suggests that children’s letter-name knowledge is associated with their syllable awareness even after controlling for their body and phoneme awareness in addition to other control variables (i.e., age and gender).

Results

Relationship of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness with literacy skills in Korean

The first research question was whether children with higher level of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness have better literacy skills, and if so, which one (letter-name knowledge or phonological awareness) is more important to literacy skills in Korean. Results are based on the conventional scoring of the outcomes (word reading, pseudoword reading, and spelling) for ease of interpretation (particularly for comparison of effect sizes). Overall, the results showed that letter-name knowledge made a positive contribution to literacy skills after controlling for phonological awareness while phonological awareness made a positive contribution to literacy skills after controlling for letter-name knowledge. However, letter-name knowledge had a stronger relationship with, and a larger impact on, literacy skills than did phonological awareness in Korean. Bivariate correlation coefficients in Table 2 show that letter-name knowledge has stronger relationships with literacy skills than does phonological awareness. For example, the relationship between letter-name knowledge and word reading skills is stronger (r = .76) than those between word reading skills and syllable awareness (r = .54), body awareness (r = .47), and phoneme awareness (r = .37). Letter-name knowledge had stronger relationships with literacy skills even when the phonological awareness total score (e.g., r = .60 for the word reading task) was examined rather than phonological awareness of various linguistic sizes (i.e., syllable, body, and phoneme awareness). Similar magnitudes and patterns were observed for pseudoword reading and spelling. The correlation coefficients for letter-name knowledge and literacy skills were significantly larger than those for phonological awareness and literacy skills (p < .05).

Furthermore, children’s letter-name knowledge explained a consistently larger amount of the variability in each of their literacy outcomes than did their phonological awareness, after controlling for children’s age and gender. The results in the top and bottom panels in Table 3 show the estimated amounts of variability explained in each literacy outcome by phonological awareness and letter-name knowledge, after controlling for children’s age and gender. For example, children’s letter-name knowledge explained substantial amounts of variability in word reading, pseudoword reading, and spelling (42%, 30%, and 29%, respectively), after controlling for their gender and age (top panel, step 2). Even when children’s phonological awareness of various linguistic sizes was controlled (bottom panel, step 3), children’s letter-name knowledge predicted substantial additional variability in their literacy skills (.20 ≦ ΔR 2 ≦ .35). When the phonological awareness total score was used, children’s letter-name knowledge still added a substantial amount of unique variation in their literacy skills (ΔR 2 = .23, .15, .17 for word reading, pseudoword reading, and spelling, respectively).

In contrast, children’s phonological awareness explained smaller amount of variability in their literacy skills than those by letter-name knowledge. Children’s syllable awareness, body awareness, and phoneme awareness predicted 6 to 18% of the variability in each literacy outcome, after controlling for children’s age and gender (bottom panel, step 2). When the phonological awareness total score was used in the second step, it explained 23%, 20%, and 15% of variability in the word reading, pseudoword reading, and spelling outcomes, respectively (models not shown). When letter-name knowledge was accounted for, however, phonological awareness explained between 0 to 5 percent of variability in the literacy outcomes (top panel, step 3). Specifically, phonological awareness total score explained additional 3 to 5 percent of variability while syllable and phoneme awareness explained an additional 2 to 4 percent of the variability in word reading, pseudoword reading, and spelling. Body awareness was positively related to word reading (p = .018), but did not explain additional variability in pseudoword reading (p = .09) and spelling (p = .60), after controlling for gender, age, and letter-name knowledge. This appears to be due to the sizeable covariance of letter-name knowledge and body awareness (r = .42, p < .001), because when letter name knowledge was not included as a predictor in the model, in the second step, body awareness remained positively related to all the three aspects of literacy skills (bottom panel, step 2).

Results from dominance analysis confirmed the above results. As seen in Table 4, across all the three literacy outcomes, letter-name knowledge explained approximately 23 to 35% of variance in the literacy outcomes in Korean above and beyond the variability explained by phonological awareness of different linguistic sizes, age and gender. Syllable awareness explained 8 to 11% of variance in early literacy outcomes above and beyond letter-name knowledge, age, and gender. Body awareness and phoneme awareness explained 4 to 7% of variance in the literacy outcomes. When phonological awareness total score was used as a predictor instead of syllable, body, and phoneme awareness, letter-name knowledge explained 38%, 27%, and 29% of variance and phonological awareness total score explained 18%, 16%, and 14% of variance in word reading, pseudoword reading, and spelling outcomes, respectively. The results were essentially the same when alternative scoring was used for word reading, pseudoword reading, and spelling skills (see Table 4).

The same picture emerged from effect size estimates of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness on literacy skills in regression analyses (see Table 5). Overall, children’s letter-name knowledge had an effect on literacy skills that was approximately two times larger than the effect of their phonological awareness. In Table 5, the estimates listed in the second column under ‘word reading’ are the estimated sizes of the effects of children’s phonological awareness and letter-name knowledge on their word reading skills. For example, it was estimated that a one standard deviation difference in children’s letter-name knowledge was associated with about a 14–15 word difference in word reading skills (more than half of a standard deviation), after taking into account the effects of children’s age, gender, and phonological awareness. In contrast, a one standard deviation difference in children’s phonological awareness (syllable, body, and phoneme, respectively) was associated with 3 to 5 word difference in their word reading skills (this being approximately one fifth of a standard deviation), after controlling for children’s age, gender, and letter-name knowledge. Similar results were found when phonological awareness total score was used as a predictor. Results for the pseudoword reading and spelling outcomes presented a similar picture. Letter-name knowledge again supported fairly large effect sizes of about half a standard deviation for pseudoword reading and spelling, whereas phonological awareness supported small effect sizes of about a quarter and one fifth of a standard deviation.

Relationship between letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness in Korean

The second research question investigates the interrelationships between phonological awareness and letter-name knowledge in Korean. As seen in Table 2, not surprisingly, children’s letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness were positively related (.30 ≦ rs ≦ .47), and phonological awareness of various linguistic sizes was positively related to each other (.34 ≦ rs ≦ .53). In multiple regressions as presented in Table 6, Korean-speaking children’s letter-name knowledge was indeed positively related to their syllable awareness (p. < .01) and body awareness (p < .001), after accounting for the effects of gender, age, and phonological awareness other than the outcome. For example, letter-name knowledge was positively associated with syllable awareness after accounting for the effects of gender, age, body awareness and phoneme awareness. However, children’s letter-name knowledge was not related to their phoneme awareness (p = .25) after accounting for the effects of gender, age, and syllable and body awareness.

Discussion

Relative contribution of phonological awareness and letter-name knowledge to literacy acquisition in Korean

This study investigated (a) relative impact of two important building blocks of beginning alphabetic reading skills—letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness—on literacy acquisition in Korean and (b) the relationship between letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness in Korean. The results of this study confirmed that it is important for young Korean children to develop letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness for their literacy acquisition in Korean (i.e., word reading, pseudoword reading, and spelling).

This study further demonstrated that letter-name knowledge is substantially more important than phonological awareness to literacy skills in Korean. Letter-name knowledge explained greater amount of variability in literacy skills (approximately two times greater amount of variability), and the magnitudes of impact of Korean children’s letter-name knowledge on literacy skills were substantial and approximately two to three times larger (more than half a standard deviation in each literacy outcome) than those of phonological awareness. In contrast, phonological awareness had much smaller impact on literacy skills in Korean (close to a quarter and one fifth of a standard deviation in literacy outcomes), after accounting for the effect of letter-name knowledge.

The more important role of letter-name knowledge than phonological awareness in literacy acquisition in Korean may be attributed to the characteristics of Korean letter names. The transparent relationship between letter names and letter sounds may provide Korean children with easy and clear access to letter sounds, which in turn helps their literacy skills. Furthermore, the highly consistent phonological patterning of Korean letter names may facilitate the awareness of letter-sound correspondence by analogy (Levin et al., 2002). For example, knowing the sound value of a letter may alert the child to understand letter-sound relations for other letters, particularly when the phonological patterning is highly regular as in Korean. In contrast, in English less consistent phonological patterning of letter names and less transparent relationships between letter names and sounds may present some challenges for English-speaking children in detecting cues to learn the associated sound values for each letter. This then reduces the relative impact of letter-name knowledge on literacy acquisition in English while requiring facilitation of children’s phonological awareness in understanding the alphabetic principle to a larger extent than in Korean.

The results in the present study also contrast with the findings from English-speaking children in regards to the impact of phonological awareness of different (phonological) units on literacy skills. Studies in English showed relative importance of phoneme awareness over rime awareness to literacy skills (Hatcher & Hulme, 1999; Hoien et al., 1995; Muter, Hulme, Snowling, & Taylor, 1998; Nation & Hulme, 1997). In Korean, however, the effect size estimates of phoneme awareness were not different from those of more rudimentary phonological awareness (i.e., syllable awareness) after accounting for the effect of letter-name knowledge. In fact, results from dominance analysis showed that syllable awareness explained slightly greater amount of variability in literacy skills compared to body awareness and phoneme awareness. This role of syllable awareness in early literacy acquisition in Korean may be due to the saliency of the syllable in Korean oral language and a syllabic as well as alphabetic writing system in Korean (Kim, 2007; Taylor, 1980). Thus, children’s phonological awareness of a larger phonological unit (i.e., syllable awareness) may play as important a role as a smaller unit (i.e., phoneme awareness) in literacy acquisition in Korean. However, it should be noted that the floor effect in the phoneme awareness task in this study may have attenuated the magnitude of phoneme awareness on literacy skills.

In this study children’s body awareness was no longer associated with their pseudoword reading and spelling skills once the effect of letter-name knowledge was taken into account. This is inconsistent with results from Kim’s (2007) study, which showed that Korean children’s body awareness remained positively related to their pseudword reading and spelling skills after accounting for age, gender, grade, parental education, and letter-name knowledge. This discrepancy may be attributed to two main differences between Kim’s (2007) study and the present study. First, Kim’s (2007) study used blending and segmenting tasks, which required children to articulate sounds at syllable, onset-rime, body-coda, and phoneme level. The oddity tasks used in the present study required children to compare sounds in different phonological units in working memory. It has been shown that different phonological awareness tasks have different relationships with literacy skills in English (Katzir et al., 2006; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1999). A second plausible reason may lie in the differences in the samples of these two studies. The children in Kim’s (2007) study were 14 months older, on average, and had superior letter-name knowledge and literacy skills than the sample children in the present study. Thus the different results may be a consequence of developmental changes over time. A future study should clarify the differences found in these two studies by including multiple measures of phonological awareness and using a longitudinal study design.

Relationship between letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness

The findings in this study suggest that although children who have a better understanding of phonological structures in a language tend to have better letter-name knowledge (Bowey & Francis, 1991; Burgess & Lonigan, 1998), the relationship between phonological awareness and letter-name knowledge may vary as a function of phonological structures and characteristics of letter names in a language. Although studies in English have shown a positive relationship between letter-name knowledge and phoneme awareness, but not with rime awareness (Burgess & Lonigan, 1998; Foulin, 2005), the present study using data from Korean-speaking children showed a different pattern: Children’s letter-name knowledge was positively associated with their syllable, body, and phoneme awareness. Moreover, once other phonological awareness was taken into account in addition to age and gender, letter-name knowledge was positively associated with syllable awareness and body awareness, but not with phoneme awareness. These results suggest that the relationship between letter-name knowledge and literacy acquisition may not be necessarily mediated by phoneme awareness in particular, but perhaps mediated by awareness of other larger phonological units as well in Korean. In other words, in Korean, children’s ability to isolate sounds in the syllable and body units may help them induce sound-letter relations from their letter-name knowledge.

The significant relationship of syllable awareness and body awareness with letter-name knowledge requires elucidation because it diverges from previous findings and hypotheses based on studies in English: In alphabetic writing systems where letters represent phonemes, it is phoneme awareness that is generally expected to mediate the relationship between letter-name knowledge and literacy acquisition. The positive relationship between syllable awareness and letter-name knowledge after controlling for body and phoneme awareness suggests that children’s letter knowledge may facilitate development of children’s ability to discriminate syllable boundaries.

There may be three explanations for the positive relationship between letter-name knowledge and body awareness above and beyond syllable awareness and phoneme awareness. First, understanding of letter sounds may perhaps occur in the CV unit (i.e., the body unit) in the initial stage of induction of letter sounds from letter names, followed by phoneme level understanding. This may be particularly true for languages in which the body appears to be a salient intrasyllabic unit such as Korean (Kim, 2007; Yoon & Derwing, 2001) and Hebrew (Share & Blum, 2005). For example, when Hebrew-speaking pre-kindergartners and kindergartners were asked to provide letter sounds, the majority of children produced it with a CV structure, even with the experimenter’s explicit feedback demonstrating that letter sounds are single phonemes (Levin et al., 2006). This may be due to the difficulty of retrieving initial phonemes from spoken words, particularly because stop consonants cannot be pronounced without a vowel (Byrne & Fielding-Barnsley, 1990; Share & Blum, 2005).

A second explanation for the positive relationship between body awareness and letter-name knowledge is that the regularities of CV-VC phonological patterning of letter names and the transparent relationship between letter names and sounds in Korean may provide particularly consistent and easy access to the consonant in the onset and the perfectly transparent vowels. This may help children form and secure connections between letter names and letter sounds in the CV unit (which corresponds to the body unit) during induction of letter sounds from letter names in Korean because induction of sound-letter relations has been shown to be most accessible for the initial phoneme (i.e., onset) in the CV letter names (McBride-Chang, 1999; Treiman & Kessler, 2003). In contrast, in English, opaqueness of the relationship between letter names and sounds, particularly in the vowels, may require children’s attention to isolate sounds at the phoneme level. In addition, according to this reasoning, the letter names in English may also induce body awareness for English-speaking children at a certain point of letter-sound induction because many English letter names (i.e., 12) have CV structure. Future studies should explore how awareness of different phonological units is related to potentially different stages of induction of letter sounds in relation to characteristics of letter names. It should be noted that these results do not exclude the role of phoneme awareness in the induction of sounds in Korean as phoneme awareness was positively correlated with letter-name knowledge when other phonological awareness (i.e., syllable awareness and body awareness) was not controlled for.

Finally, a third reason may be an instructional factor: in Korea sometimes letter names are introduced using C/a/ structure (e.g., /ka/, /na/, /ta/, etc.) instead of the formal C/i/./ɨ/C names (e.g., /kɪ-jʌk/, /nɪ-ɨn/, /tɪ-gɨt/, etc.). The strength of this C/a/ approach is that many high frequency words in Korean start with C/a/ structure so that children may easily see the correspondence between letter names and spellings. However, this structure of letter names does not provide children with information about the sound values for consonants in the coda. Unfortunately, the extent of systematic letter-name instruction as well as the extent of using either or both of these two approaches in letter-name instruction in the Korean context is unknown.

Limitations and implications

It should be noted that the phoneme awareness task and the spelling task had severe floor effects in this study. Although despite the floor effects, variation in phoneme awareness and spelling was positively related to the majority of the variables in the study (e.g., phonological awareness and all the literacy skills), the reduced variance in the phoneme awareness and spelling tasks may have obscured their relationships with other variables to some extent. Future studies are warranted. Furthermore, it should be noted that the correlational nature of the present study does not allow us to tease out the directionality of the relationship between letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness, thus requiring caution in interpretation. For example, it is possible that phonological awareness and letter-name knowledge has a bidirectional relationship such that children’s phonological awareness facilitates the acquisition of letter names.

The findings of the present study offer several important implications. First, they inform us that the relative influences of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness depend on the characteristics of oral language, letter names, and orthography in a given language. Therefore, our understanding of factors influencing early literacy skills development should incorporate variation across languages, warranting more systematic investigation in languages other than English. For example, a future intervention study with Korean-speaking children is warranted to confirm the different magnitudes of impact of letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness on literacy acquisition in Korean.

Second, children learning Korean will benefit greatly from systematic and explicit instruction of letter names. Children should be introduced to the alphabet letters using letter names and also explicitly taught how the letter names provide important cues for the sounds in the syllable-initial and syllable-final contexts as well as vowels. This educational implication is critical in the current Korean context because anecdotal evidence indicates that letter names may not be systematically taught in beginning literacy education, primarily due to the influence of a whole language (or whole word) instructional approach since the 1990’s. Moreover, an explicit instruction of letter-sound relations is extremely rare in early literacy instruction in Korea.

Finally, the results of the present study also showed that Korean children’s phonological awareness facilitates children’s literacy acquisition beyond their letter-name knowledge in Korean. This implicates that Korean children will benefit from systematic instruction and emphasis on oral language development prior to or concomitantly with literacy instruction. Traditionally, literacy or preliteracy instruction in Korea tends not to pay explicit and substantial attention to oral language development.

Notes

In English 24 of the 26 letters contain a speech phoneme of the sound value (Treiman & Kessler, 2003) while in Korean 35 of the 40 letters do. In Korean five double consonants do not contain the corresponding phoneme and they are named literally ‘double’-single consonant.

Two exceptions are letters, /kɪ.jʌk/ and /tɪ.gɨt/, which have a CV.CVC structure.

While the majority of letter names for consonants have /ɨ/ in the second syllable, two exceptions exist. One letter name has /jʌ/ (kɪjʌk) and the other has /o/ (∫ɪot).

Phonemic contrasts of 19 consonants in the onset are neutralized to seven in the coda.

References

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Aidinis, A., & Nunes, T. (2001). The role of different levels of PA in the development of reading and spelling in Greek. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 14, 145–177.

Azen, R., & Budescu, D. V. (2003). The dominance analysis for comparing predictors in multiple regression. Psychological Methods, 8, 129–148. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.8.2.129.

Blatchford, P., & Plewis, L. (1990). Pre-school reading-related skills and later reading achievement: Further evidence. British Educational Research Journal, 16, 425–428. doi:10.1080/0141192900160409.

Bowey, J. A. (1994). Phonological sensitivity in novice readers and nonreaders. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 58, 134–159. doi:10.1006/jecp.1994.1029.

Bowey, J., & Francis, J. (1991). Phonological analysis as a function of age and exposure to reading instruction. Applied Psycholinguistics, 12, 91–121.

Bradley, L., & Bryant, P. (1985). Rhyme and reason in reading and spelling. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Bryant, P. E., Maclean, M., Bradley, L. L., & Crossland, J. (1990). Rhyme and alliteration, phoneme detection, and learning to read. Developmental Psychology, 26, 429–438. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.26.3.429.

Budescu, D. V. (1993). Dominance analysis: A new approach to the problem of relative importance of predictors in multiple regression. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 542–551. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.542.

Burgess, S. R., & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Bidirectional relations of phonological sensitivity and prereading abilities: Evidence from a preschool sample. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 70, 117–141. doi:10.1006/jecp.1998.2450.

Byrne, B., & Fielding-Barnsley, R. (1990). Acquiring the alphabetic principle: A case for teaching recognition of phoneme identity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 805–812. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.82.4.805.

Byrne, B., & Fielding-Barnsley, R. (1993). Evaluation of a program to teach phonemic awareness to young children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 104–111. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.85.1.104.

Chaney, C. (1994). Language development, metalinguistic awareness, and emergent literacy skills of 3-year-old children in relation to social class. Applied Psycholinguistics, 15, 371–394.

Cho, J.-R., & McBride-Chang, C. (2005). Correlates of Korean Hangul Acquisition among kindergartners and second graders. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9, 3–16. doi:10.1207/s1532799xssr0901_2.

de Jong, P. F., & van der Leij, A. (1999). Specific contributions of phonological abilities to early reading acquisition: Results from a Dutch latent variable longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 450–476. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.91.3.450.

Dixon, M., Stuart, M., & Masterson, J. (2002). The relationship between phonological awareness and the development of orthographic representations. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 15, 295–316.

Ehri, L. C. (1983). A critique of five studies related to letter-name knowledge and learning to read. In L. Gentile, M. Kamil, & J. Blanchard (Eds.), Reading research revisited (pp. 143–153). Columbus, OH: C.E. Merrill.

Evans, M. A., Shaw, D., & Bell, M. (2000). Home literacy activities and their influence on early literacy skills. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 54, 65–75. doi:10.1037/h0087330.

Foulin, J. N. (2005). Why is letter-name knowledge such a good predictor of learning to read? Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 18, 129–155.

Goswami, U. (1991). Learning about spelling sequences: The role of onsets and rimes in analogies in reading. Child Development, 62, 1110–1123. doi:10.2307/1131156.

Goswami, U., & Mead, F. (1992). Onset and rime awareness and analogies in reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 27, 153–162. doi:10.2307/747684.

Goswami, U., Ziegler, J. C., & Richardson, U. (2005). The effects of spelling consistency on phonological awareness: A comparison of English and German. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 92, 345–365.

Hatcher, P. J., & Hulme, C. (1999). Phonemes, rhymes and intelligence as predictors of children’s responsiveness to remedial reading instruction: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 72, 130–153. doi:10.1006/jecp. 1998.2480.

Hoien, T., Lundberg, I., Stanovich, K., & Bjaalid, I.-K. (1995). Components of phonological awareness. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 7, 171–188.

Hulme, C., Hatcher, P. J., Nation, K., Brown, A., Adams, J., & Stuart, G. (2002). Phoneme awareness is a better predictor of early reading skill than onset-rime awareness. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 82, 2–28. doi:10.1006/jecp.2002.2670.

Johnston, R. S., Anderson, M., & Holligan, C. (1996). Knowledge of the alphabet and explicit awareness of phonemes in pre-readers: The nature of the relationship. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 8, 217–234.

Katzir, T., Kim, Y.-S., Wolf, M., O’Brien, B., Kennedy, B., Lovett, M., et al. (2006). Reading fluency: The whole is more than the parts. Annals of Dyslexia, 56, 51–82. doi:10.1007/s11881-006-0003-5.

Kim, Y.-S. (2007). Phonological awareness and literacy skills in Korean: an examination of the unique role of body-coda units. Applied Psycholinguistics, 1, 69–94. doi:10.1017/S014271640707004X.

Kim, Y.-S. (in press). Cat in a hat or cat in a cap? An investigation of developmental trajectories of phonological awareness for Korean children. Journal of Research in Reading.

Levin, I., Patel, S., Margalit, T., & Barad, N. (2002). Letter names: Effect on letter saying, spelling, and word recognition in Hebrew. Applied Psycholinguistics, 23, 269–300. doi:10.1017/S0142716402002060.

Levin, I., Shatil-Carmon, S., & Asif-Rave, O. (2006). Learning of letter names and sounds and their contribution to word recognition. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 93, 139–165. doi:10.1016/j.jecp. 2005.08.002.

Lonigan, C. J., Burgess, S. R., & Anthony, J. L. (2000). Development of emergent literacy and early reading skills in preschool children: Evidence from a latent-variable longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 36, 596–613. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.596.

MacLean, M., Bryant, P., & Bradley, L. (1987). Rhymes, nursery rhymes, and reading in early childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33, 255–281.

McBride-Chang, C. (1999). The ABCs of the ABCs: The development of letter-name and letter-sound knowledge. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45, 285–308. 3–19.

Muter, V., Hulme, C., Snowling, M., & Taylor, S. (1998). Segmentation, not rhyming, predicts early progress in learning to read. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 71, 3–27.

Muter, V., Hulme, C., Snowling, M., & Stevenson, J. (2004). Phonemes, rimes, vocabulary, and grammatical skills as foundations of early reading development: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 40, 665–681.

Nation, K., & Hulme, C. (1997). Phonemic segmentation, not onset-rime segmentation, predicts early reading and spelling skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 32, 154–167.

Na̎slund J. C., & Schneider, W. (1996). Kindergarten letter knowledge, phonological skills, and memory processes: Relative effects on early literacy. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 62, 30–59.

Oney, B., & Durgunoglu, A. Y. (1997). Beginning to read in Turkish: A phonologically transparent orthography. Applied Psycholinguistics, 18, 1–15.

Scarborough, H. S. (1998). Early identification of children at risk for reading disabilities: Phonological awareness and some other promising predictors. In B. K. Shapiro, P. J. Accardo, & A. J. Capute (Eds.), Specific reading disability: A view of the spectrum (pp. 75–119). Timonium, MD: York Press.

Schatschneider, C., Fletcher, J. M., Francis, D. J., Carlson, C. D., & Foorman, B. R. (2004). Kindergarten prediction of reading skills: A longitudinal comparative analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 265–282.

Schatschneider, C., Francis, D. J., Foorman, B. R., Fletcher, J. M., & Mehta, P. (1999). The dimensionality of phonological awareness: An application of item response theory. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 439–449.

Share, D. L. (2004). Knowing letter names and learning letter sounds: A causal connection. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 88, 213–233.

Share, D. L., & Blum, P. (2005). Syllable splitting in literate and preliterate Hebrew speakers: Onsets and rimes or bodies or codas? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 92, 182–202.

Share, D. L., Jorm, A. F., Maclean, R., & Matthews, R. (1984). Sources of individual differences in reading acquisition. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 1309–1324.

Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (Eds.). (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Sprugevica, I., & Hoien, T. (2003). Enabling skills in early reading acquisition: A study of children in Latvian kindergartens. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16, 159–177.

Stuart, M., & Coltheart, M. (1988). Does reading develop in a sequence of stages? Cognition, 30, 139–181.

Taylor, I. (1980). The Korean writing system: An alphabet? a syllabary? a logography? In P. A. Kolers, M. E. Wrolstad, & H. Bouma (Eds.), Processing of visible language (pp. 67–82). New York: Plenum Press.

Treiman, R. (1983). The structure of spoken syllables: Evidence from novel word games. Cognition, 15, 49–74.

Treiman, R. (1985). Onsets and rimes as units of spoken syllables: Evidence from children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 39, 161–181.

Treiman, R. (1992). The role of intrasyllabic units in leaning to read and spell. In P. B. Gough, L. C. Ehri, & R. Treiman (Eds.), Reading acquisition (pp. 65–106). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Treiman, R., & Kessler, B. (2003). The role of letter names in the acquisition of literacy. In R. Kail (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 31). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Treiman, R., Tincoff, R., Rodriguez, K., Mouzaki, A., & Francis, D. J. (1998). The foundations of literacy: Learning the sounds of letters. Child Development, 69, 1524–1540.

Treiman, R., & Zukowski, A. (1991). Level of phonological awareness. In S. A. Brady & D. P. Shankweiler (Eds.), Phonological processes in literacy (pp. 67–84). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Vellutino, F. R., & Scanlon, D. M. (1987). Phonological coding, phonological awareness, and reading ability: Evidence from a longitudinal and experimental study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33, 321–363.

Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., & Rashotte, C. A. (1994). Development of reading-related phonological processing abilities: New evidence of bidirectional causality from a latent variable longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 30, 73–87.

Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., & Rashotte, C. A. (1999). Comprehensive test of phonological processing. Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69, 848–872.

Yoon, Y.-B., & Derwing, B. (2001). A language without a rhyme: Syllable structure experiments in Korean. Canadian Journal of Linguistics, 46, 187–237.

Acknowledgements

Part of this study was supported by a National Science Foundation Dissertation Grant (#0545205) and Harvard Korea Institute’s Min Young-Chul Memorial Summer Travel Fellowship. The author wishes to thank all the children, teachers, and preschool directors who participated in this study. Special thanks are due to Jaesik Kim and Heesook Kim. In addition, the author wishes to thank Catherine Snow, John Willett, Andrew Nevins, and anonymous reviewers for their feedback on earlier version of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Pilot sample means, standard deviations, and t statistics for testing differences in children’s performances on body awareness tasks with varied linguistic manipulations in the target word in the oddity tasks (n = 75)

Body awareness | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

Rime change | 2.81 (1.22) |

Onset coda change | 2.37 (1.18) |

Syllable change | 2.40 (1.25) |

In this study, syllable change condition was used in the body awareness task. In the pilot test, the linguistic characteristics of the target odd word (or distractors) were varied in the body awareness task in order to investigate whether its phonological characteristics influence children’s performance. The distractors varied in the following: (1) those requiring a rime change (i.e., the distractor shared the same onset as the other two words; e.g., puk, pul, pam), (2) those requiring an onset-coda change (i.e., the distractor shared the same vowel as the other two words; sam, p h an, p h al), and (3) those requiring a syllable change (i.e., the distractor did not share any sounds with the other two words; e.g., mal, puk, man). A total of 24 items (8 items in each linguistic structure for distractors) was used in the body awareness task. The order of items for each linguistic manipulation condition was randomly arranged.

As seen in the table above, in the body awareness tasks, children’s performance on the rime change distractor items was statistically significantly higher than on the onset-coda change distractor items (t = 3.65, p = .000) as well as on the syllable change distractor items (t = 3.32, p = .001), but there was no difference in children’s performance between onset-coda change distractor items and syllable change items. Thus, in this study, syllable change condition was used.

In addition, an attempt was made to examine the potential effect of global sound similarity in the distractors. In another study, a subsample of children (n = 63) were given another body awareness task in addition to the body awareness task with syllable change condition used in this study. In this task, the odd word (distractor) shared the same consonant sounds as one of the other two words and only differed in the vowel (e.g., kaŋ, kam, kim). In this case, the global sound similarity was controlled because two phonemes are shared in the two words that share the same sounds in the body unit (CV, /k/ and /a/ in the example) as well as in one of the two words and the distractor (CC, /k/ and /m/ in the example). Children’s performance on this task (m = 10.11) was not statistically different from their performance on the body awareness task in which the odd word had an entirely different syllable (m = 10.44) (F (1, 62) = .84, p = .36).

Appendix B

Korean alphabet letters and their names

Consonants | Vowels | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Letter | Letter name | Letter | Letter name |

ㄱ | kɪj∧k | ㅏ | a |

ㄴ | nɪɨn | ㅑ | ja |

ㄷ | tɪgɨt | ㅓ | ∧ |

ㄹ | rɪɨl | ㅕ | j∧ |

ㅁ | mɪɨm | ㅗ | o |

ㅂ | pɪɨp | ㅛ | jo |

ㅅ | ∫ɪot | ㅜ | u |

ㅇ | ɪɨŋ | ㅠ | ju |

ㅈ | cɪɨt | ㅡ | ɨ |

ㅊ | t∫ɪ ɨt | ㅣ | ɪ |

ㅋ | khɪɨk | ㅐ | æ |

ㅌ | thɪɨt | ㅔ | æ |

ㅍ | phɪɨp | ㅘ | wa |

ㅎ | hɪɨt | ㅟ | wɪ |

ㄲ | ssaŋkɪj∧k | ㅢ | ɨɪ |

ㄸ | ssaŋtɪgɨt | ㅝ | w∧ |

ㅃ | ssaŋpɪɨp | ㅖ | jɛ |

ㅆ | ssaŋ∫ɪot | ㅒ | jɛ |

ㅉ | ssaŋcɪɨt | ㅚ | wɛ |

ㅙ | wɛ | ||

ㅞ | wɛ | ||

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, YS. The foundation of literacy skills in Korean: the relationship between letter-name knowledge and phonological awareness and their relative contribution to literacy skills. Read Writ 22, 907–931 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-008-9131-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-008-9131-0