Abstract

We hypothesize debt markets—not equity markets—are the primary influence on “association” metrics studied since Ball and Brown (1968 J Account Res 6:159–178). Debt markets demand high scores on timeliness, conservatism and Lev’s (1989 J Account Res 27(supplement):153–192) R 2, because debt covenants utilize reported numbers. Equity markets do not rate financial reporting consistently with these metrics, because (among other things) they control for the total information incorporated in prices. Single-country studies shed little light on debt versus equity influences, in part because within-country firms operate under a homogeneous reporting regime. International data are consistent with our hypothesis. This is a fundamental issue in accounting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Does the demand for financial reporting arise primarily in debt markets or in equity markets? Are timely financial statements more useful to lenders or to shareholders? Is debt or equity primarily responsible for accounting conservatism? In an attempt to shed some light on these fundamental questions, we formulate and test the hypothesis that debt markets—not equity markets—exert the primary influence on the financial reporting metrics commonly estimated in “association” studies. These metrics, which include “earnings response coefficients” and the contemporaneous R 2 between earnings and returns (Lev 1989), are intended to capture important fundamental properties of financial reporting, such as relevance, timeliness and conservatism. They have been extensively studied in the accounting literature since Ball and Brown (1968).

We propose that debt markets create a demand for financial reporting that scores highly on traditional association-study metrics. Association studies measure the contemporaneous relation between financial statement variables and stock returns. Assuming market efficiency, they measure the timeliness of accounting recognition (i.e., how quickly available information is incorporated in the financial statements). Timeliness affects debt contracting because reported financial statement variables affect various covenanted financial ratios, including balance sheet leverage and earnings-based interest coverage ratios, and also affect dividend and stock repurchase restrictions. In particular, timely recognition of losses is necessary for loss-making firms to violate covenanted ratios in a timely fashion. Timely covenant violation leads to timely triggering of lenders’ contractual rights to veto major decisions by loss-making managers that could further erode debt quality, such as risky new investments and acquisitions, borrowing, dividends and stock repurchases. Untimely loss recognition reduces the effectiveness of contractual restrictions on the decision rights of loss-making managers that are based on financial-statement outcomes. Debt markets therefore p refer a strong association between financial statement variables and the information incorporated in share prices.Footnote 1

We also propose that equity markets create a relatively low demand for association per se. The primary reason for this hypothesis is that all association-study metrics control for the first-order concern of equity markets, namely the total amount of information incorporated in share prices. For example, the contemporaneous R 2 between earnings and returns (Lev 1989) measures the proportion of the total information used by the equity market that is captured in earnings in the same period. Given the total information available to it, the proportion from one source or another seems a second-order concern to the equity market. For this and other reasons outlined below, we propose that equity markets are not the primary source of demand for financial reporting that rates highly on commonly-studied association-study metrics.Footnote 2

Like all economic activities, financial reporting is costly, and not in unlimited supply. At the country level, there are costs of developing and operating complex institutions such as independent audit professions, independent and effective judicial systems to enforce securities contracts and laws, regulatory systems, and various monitoring mechanisms (analysts, rating agencies, short sellers, press). At the company level, there are costs of installing and operating information systems and accounting and control functions, of management and board time, and of internal and external auditing. Because timely financial reporting is a costly activity, we expect the resources devoted to it depend on demand.Footnote 3 Our fundamental proposition therefore is that debt markets generate more demand than equity markets for financial reporting that scores highly on association study measures, and are more likely to influence those scores.

Out tests of this proposition exploit variation among countries in relative debt and equity market demands on financial reporting. The proxies for debt and equity demands are the sizes of countries’ debt markets and equity markets. We expect that, other things equal, the countries with smaller capital markets generate less demand for effective financial reporting and hence devote fewer resources to developing and operating costly financial reporting systems. Conversely, countries with larger capital markets can devote more resources to effective financial reporting. This simple logic underlies our tests, in which measures of countries’ financial reporting properties are regressed on the countries’ debt and equity market sizes, to estimate where the demand for financial reporting resides.

We first estimate, from Basu (1997) piecewise-linear regressions of earnings on returns, country-level financial reporting timeliness (loss and gain recognition timeliness, the R 2 measure of overall timeliness). We also estimate country-level conservatism (conditional conservatism, unconditional conservatism, and the market/book ratio). We then regress countries’ these estimated financial reporting properties on the sizes of their debt and equity markets.Footnote 4 The sample comprises 78,949 firm-year observations during 1992–2003 from 22 countries. We aggregate the observations within each country and study variation across countries, so the regressions have 22 observations. While this design gives the appearance of studying a small sample of only 22 countries, the underlying sample is large.

The country-level design has several compelling advantages over a more traditional firm-level study. First, a large proportion of the costs of developing and operating a financial reporting system are incurred at the country infrastructure level. Testing our hypothesis that the amount of cost incurred in ensuring high-quality financial reporting practice is a function of the extent of demand for it therefore requires measures of countries’ debt and equity market demands. Second, studying even a large sample of individual firms within a single country is unlikely to shed much light on how financial reporting is shaped by satisfying debt versus equity market demand, because public firms within one country generally operate under a single reporting, litigation and regulatory regime. The underlying effects of debt and equity market demand thus are relatively constant across firms within one regime, independent of the firms’ individual financing policies. For example, the accounts of all public US firms are prepared under US GAAP, are audited according to US standards, and (perhaps more importantly) are subject to S.E.C. enforcement and stockholder litigation under US laws—regardless of the firms’ individual use of debt versus equity finance.Footnote 5 Third, at the firm level there is a perfectly negative correlation between debt and equity, making it impossible to identify their separate effects, whereas the country-level correlation in our sample is small & positive, +0.30. Fourth, clustering by country avoids over-stating test statistics that would arise from treating individual firm and year observations within a country as independent. Under our hypothesis, financial reporting practice within a country is determined by its institutional structure, so financial reporting practices of individual firms are not independent across either firms or years. Fifth, our procedure of treating each country as an observation avoids the fitted regression being dominated by countries with large numbers of public firms (sample sizes range from 379 for Chile to 27,559 for US). For the above reasons, we believe the appropriate level of observation is the country, not the individual firm.

The regressions control for various non-market determinants of financial reporting practice, using La Porta et al. (1997, 1998) data. The controls include countries’ legal system origins (English, French, German or Scandinavian). Ball et al. (2000a) view legal origin as a proxy for the degree of political influence on financial reporting (versus debt and equity market influences), and show it is related to timeliness and conditional conservatism. The regressions also control for three legal-system variables that Bushman and Piotroski (2006) report are related to timeliness and conditional conservatism: Rule of Law, Corruption and Creditors’ Rights. All results are robust with respect to these controls. In particular, we obtain consistently statistically significant results for the debt market proxy.

The results are not driven by outliers. Within each country, we exclude extreme earnings and return observations when estimating the country-level association-study metrics. The country-level data reported in Table 1 show no evidence of outliers in the important dependent and independent variables. Consistent with the apparent absence of outliers, the results are not sensitive to deleting individual countries from the sample (i.e., there is no evidence of a “knife edge” effect). Because the precision of the estimates of countries’ financial reporting properties likely varies (due, for example, to different sample sizes), we also report Weighted Least Squares (WLS) results, weighting the countries’ observations by the inverse of the standard errors of the country level association-study metrics. The WLS results are even stronger.

An attractive feature of the research design is that the dependent variables (estimated properties of financial reporting, such as timeliness) are not derived from a scoring of countries’ formal accounting standards. Standards are an imperfect guide to financial reporting practice because they are not implemented uniformly around the world. Following Ball et al. (2000a), the research utilizes observable properties of the financial statements that firms in different countries actually report.

We recognize the research design has limitations. As in most cross-country studies, the potential for correlated omitted variables is a concern, despite controlling for several variables. We have only proxies for the dependent and independent variables, though the model explains approximately half of the cross-country variation in estimated loss recognition timeliness.

We report robust evidence that debt markets—but not equity markets—are associated with important financial reporting properties, consistent with our hypothesis. This is a fundamental issue in accounting, but to our knowledge it has not previously been investigated directly. At the most fundamental level, the conclusion speaks to the economic origins of financial reporting. The apparent primacy of debt market influence on reporting is inconsistent with the “value relevance” school of accounting thought, in which financial reporting exists primarily to inform share markets, but is consistent with a “costly contracting” view.Footnote 6

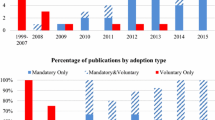

Our results suggest an alternative interpretation of the remarkable increase over time in loss recognition timeliness documented by Basu (1997, Fig. 3) and replicated internationally by Ball et al. (2000a, Table 9): corporate debt markets increasing over time in economic importance. Basu attributes the result to legal liability, but that could to some degree be an endogenous response to increasing debt market demand.

For practitioners, the evidence of debt market demand for conditional conservatism suggests the long-standing ambivalence of standard-setters to conservatism could be misplaced, and perhaps based in part on a confusion between conditional and unconditional conservatism, as suggested by Ball and Shivakumar (2005), or alternatively on the misconception that the demand for financial reporting originates primarily or exclusively in the equity market.Footnote 7 Further, the result that debt markets—but not equity markets—are associated with important properties of financial reporting brings into question the fundamental concept of “general purpose external financial reporting,” that it “is directed toward the common interest of various potential users.”Footnote 8

Finally, the result that both the balance-sheet-based and income-statement-based measures of unconditional conservatism are unrelated to debt market importance is inconsistent with the notion that unconditionally low book values exist for creditor protection. This has long been the dominant rationale for continental European conservatism, particularly in Germany (Schneider 1995; European Federation of Accountants 1997; Haller 1998; Nobes 1998). The creditor protection rationale for unconditional conservatism is inconsistent with our results, supporting the Ball (2004) and Ball and Shivakumar (2005) argument that it does not make compelling economic sense.

Section 2 of the paper describes timely financial reporting as an economic activity, subject to costly supply. Section 3 outlines important differences between debt and equity market demands on financial reporting, and develops our hypotheses. Section 4 describes the sample, data, estimation procedures, and across-country regressions used to test the hypotheses. Section 5 outlines the results. Section 6 presents conclusions and a discussion of interpretation issues including omitted variables and causality.

2 Timely financial reporting as a costly accrual accounting activity

This section observes that increasing the timeliness of earnings relative to cash flows requires accrual accounting, which it describes as a costly economic activity. The following section argues that the amount of resources devoted to accrual accounting, and hence to increasing the timeliness of earnings and balance sheet variables, depends on the demand for it.

By definition, timely gain and loss recognition incorporates information about future cash flows into accounting income around the time the information arises. This requires accounting accruals (Ball and Shivakumar 2006), because gains and losses normally have not been fully realized at the time they occur (i.e., they have not yet been fully reflected in cash flows). Examples of loss accruals are write-downs in accounts receivable due to downward revisions in expected future cash collections, write-downs in inventory (due to decreases in expected future cash flows from the investment in inventory, due to physical loss, damage, obsolescence, decline in market price, etc.), booked decreases in values of marketable securities and derivatives, foreign currency losses, provisions for environmental liabilities, provisions for litigation settlements, loss provisions, restructuring charges, and asset impairment charges. Examples of gain accruals are booked increases in values of marketable securities and derivatives, foreign currency gains, and long-term asset revaluations. In general, timely gain and loss accruals incorporate new information into earnings around the time it arrives, thereby increasing the score of earnings on various association-study metrics.

There is comparatively little timing discretion over recording actual cash flows, because there is little ambiguity concerning when they eventuate (in accounting parlance, when they are “realized”). In contrast, there is considerable discretion over when and if revisions in future cash flow expectations are incorporated in the financial statements (in accounting parlance, when they are “recognized”). Because managers cannot be expected to exercise discretion only in the interests of financial-statement users, costly systems are required to ensure that accruals rules actually are implemented, particularly timely recognition accruals.

Financial reporting costs occur at the country level and also at level of individual companies. Country-level costs of implementing timely financial reporting most likely are economically substantial, due to the complexity of the institutional framework needed to ensure that companies actually practice it. There are costs associated with training accountants and in training an effective auditing profession, and with developing accounting standards and detailed audit procedures to ensure that standards in fact are implemented. There are costs of developing and operating the myriad other monitoring mechanisms that developed economies take for granted (including company boards, audit committees, stock exchanges, security analysts, credit rating agencies and an independent press). There are costs of developing and operating an independent and effective judicial system in which private litigation can occur, as well as in developing and operating an effective regulatory system. We hypothesize these costs are economically substantial, particularly for the countries with smaller capital markets.Footnote 9

Company-level reporting costs arise because timeliness requires accounting accruals which incur incremental managerial, accounting and auditing costs, relative to the cost of simply recording realized cash outcomes. Reviewing inventory on a regular basis to check for wastage, obsolescence, theft, damage and other losses consumes managerial, accounting and audit verification resources. Regular reviews of receivables, provisions—and accruals in general—involve equivalent costs. Implementation of an asset impairment standard such as SFAS No. 144 involves costly periodic review of assets’ expected future cash flows.

In sum, to the extent that financial reporting practice is determined by market (as distinct from political) factors, the amount of resources devoted to countries’ financial reporting systems are expected to reflect demand and cost (supply) considerations. Comparative debt and equity market demands for timely financial reporting are studied in the following section.Footnote 10

3 Differences between debt and equity market demands for timely recognition

Debt and equity markets differ in the extent and nature of their demands for financial reporting. In this section, we emphasize four fundamental differences that suggest financial reporting practice is shaped to a larger degree by the debt market. The effects of political (i.e., non-market) and legal factors are discussed in the following section.

3.1 Greater importance of accounting recognition for debt contracting

One important difference between debt and equity lies in the distinction between the total amount of information available to investors and other economic agents, and the incorporation of that information in the financial statements (known in accounting as “recognition”). Given the available information, debt markets are more likely than equity markets to demand its timely recognition, because many debt covenants are written in terms of financial-statement variables such as interest coverage and financial leverage (Smith and Warner 1979).

Like equity markets, debt markets utilize both financial-statement and other information in pricing decisions, at issuance and in the secondary market. But debt differs from equity in that many of the post-issuance contractual rights of lenders are couched in terms of financial statement variables alone. Available information that is not reflected in the financial statements does not affect those rights. Timely recognition (incorporation of economic gains and losses in earnings and hence on balance sheets) therefore is important per se for debt markets. Shareholders are comparatively indifferent as to whether gain and loss information is reflected in the financial statements or received via non-financial disclosure, so long as they receive it.

This reasoning implies that the contemporaneous R 2 between earnings and returns, a summary timeliness metric popularized by Lev (1989), has greater relevance for debt markets than equity markets.Footnote 11 The R 2 metric controls for the total amount of information available, and there is no first-order reason for the equity market to care about the proportion arising from one source or another, given the total amount of information available.Footnote 12 Accountants might be worried about the proportion of total information incorporated in financial statements, as a measure of “market share,” but equity investors most likely are relatively indifferent to it. Paradoxically, the importance of timely accounting recognition for debt, but not for equity—an important point largely unrecognized in the literature—implies the association between financial statement variables and equity returns is more important to debt markets than equity markets.Footnote 13

A parallel implication for balance sheets is that equity markets are relatively indifferent to the book/market ratio. When interpreted as a measure of financial reporting conservatism, this ratio measures the proportion of equity value contemporaneously captured in balance sheet book values. Here too, there is no first-order reason to believe that equity investors are concerned about the proportion of market value that accountants report on the balance sheet, given market value. The proportion might concern accountants, but it too controls for the total amount of information incorporated in market value, which is the equity market’s primary concern.

The argument can be generalized to all association-study measures of financial reporting, because they control for the total information incorporated in prices. This is not to argue there is no equity market demand for timely new accounting information, at the margin. The point is that, by controlling for the total amount of information, association studies cannot address marginal effects.

3.2 Confirmation demand for accounting

A second difference between debt and equity demands for financial reporting arises from the interaction between financial reporting and other disclosures. Gigler and Hemmer (1998) and Ball (2001) argue that accurate reporting of actual outcomes (such as realized cash flows) exerts a discipline on managers’ public disclosures about expected outcomes (such as growth prospects and earnings forecasts), because managers then know they later will be held more accountable for their statements. This increases the informativeness of non-financial disclosures, but because it requires a reporting focus on actual outcomes rather than revisions in expectations it also decreases the informativeness of financial reports. Both effects reduce financial reporting scores on association-study metrics, including R 2.

The debt-equity difference arises here because equity markets have more to gain from sacrificing financial reporting timeliness for non-financial disclosure informativeness, if this leads to a net increase in total information quantity, whereas the debt market has a greater demand for timely financial-statement recognition per se. The equity market might prefer an accounting regime that is not oriented to timely reporting of new information. The point turns on the distinction between the average amount of new information in financial reporting and the marginal effect of financial reporting on the total amount of new information.

3.3 Equity portfolio diversification

A third difference between debt and equity demands for financial reporting arises from equity portfolio diversification. To the extent equity investors are concerned about the R 2 between earnings and returns, portfolio diversification implies the relevant R 2 is at the portfolio level, not the individual-security level (Ball and Brown 1969, p. 316). With even modest diversification, the portfolio-level R 2 is substantially larger than its individual-firm average.Footnote 14 In contrast, debt contracts are written in terms of individual firms’ financial statement variables, so individual-firm and not portfolio-level associations are relevant in debt markets. This difference sharpens the paradox, stated above, that the timeliness with which financial statements reflect the individual-firm information incorporated in equity prices is more relevant to the debt market than to the equity market.

3.4 Asymmetric debt market demand for timely recognition

A final important difference between debt and equity arises from the asymmetric relation between changes in firm value and the value of its debt. In contrast to equity, the value of debt claims generally is more asymmetrically sensitive to decreases in firm value than to increases. Consequently, debt contracts treat gains and losses asymmetrically.

Debt contracts commonly contain leverage, interest coverage and other financial covenants that are triggered by substantial decreases in the value of the firm (Smith and Warner 1979). Covenant violations typically give lenders the right to veto specific decisions by managers that could further reduce debt value, including major financing decisions that weaken their security (dividends, stock repurchases, capital distributions to shareholders, and additional debt issuance) and major investment decisions that are potentially negative-NPV (new investments, acquisitions and asset sales).Footnote 15 Such violations are triggered by losses, not gains.

Timely accounting recognition of economic losses increases debt contract effectiveness, because it leads to timelier revision of earnings and of book values of assets, liabilities and equity, and in turn into timelier violation of financial covenants. This more quickly transfers important decision rights from loss-making managers to lenders.Footnote 16 Untimely loss recognition allows managers to continue impairing debt value, without restrictions on asset distributions to shareholders via dividends and repurchases, and without restrictions on investment.

Because timely loss recognition makes debt a more efficient form of financing, in countries that practice it we should observe comparatively larger corporate debt markets. In countries without timely loss recognition, debt is less efficient. We therefore predict that timely loss recognition increases in the importance of debt markets.

Debt market demand for timely recognition is not symmetric, however. Relative to loss recognition, the debt market generates a lower demand for timely gain recognition because debt covenants are violated by losses, not gains. Timely gain recognition can improve debt contracting under some circumstances, most notably when economic losses that earlier were recognized in the accounts subsequently reverse and thus there is a less reason for lenders to restrict their risk exposure. Losses followed by gains are less frequent than losses, so gain recognition is in lower demand than loss recognition.Footnote 17

Lower debt market demand for timely gain recognition than for loss recognition, when coupled with both being in costly supply, implies we should observe a greater quantity of timely loss recognition than timely gain recognition. If both were costless, we would expect to observe them supplied in equal amounts. But because they are costly economic activities, timely gain and loss recognition can be expected to bear some relation with their respective demands, which are not symmetric. The testable implication is that earnings are more highly correlated with negative than positive returns (Basu 1997), and is known as “conditional conservatism” (Ball and Shivakumar 2005; Beaver and Ryan 2005). We predict that conditional conservatism increases in the size of debt markets, but not equity markets.

3.5 The relative roles of equity and debt markets: tested hypotheses

We have reviewed four differences between debt and equity market demands for financial reporting. Each implies that the association-study correlation between financial statement variables and equity returns is more important to debt markets than for equity markets.

Our testable hypotheses can be stated as follows:

-

Debt Hypotheses

-

H1: Timely loss recognition increases in the importance of debt markets.

-

H2: Conditional conservatism (asymmetrically timely loss recognition relative to gain recognition) increases in the importance of debt markets.

-

H3: Unconditional conservatism (low reported earnings and book values, independent of economic gains and losses) does not increase in the importance of debt markets, controlling for conditional conservatism.

-

Equity hypotheses

-

H4: Timely gain and loss recognition do not increase in the importance of equity markets.

-

H5: Conditional conservatism (asymmetrically timely loss recognition relative to gain recognition) does not increase in the importance of equity markets.

-

H6: Overall gain and loss timeliness does not increase in the importance of equity markets.

The following section outlines our tests of these hypotheses.

4 Tests of debt, equity relation with gain and loss recognition timeliness

This section describes the estimation procedures we follow in testing the effect of debt and equity markets on financial reporting practice. First, association-study metrics are estimated for each country using pooled data for firms and years in that country. The metrics estimated are: gain and loss recognition timeliness, overall timeliness, unconditional income statement conservatism, and market-to-book ratios. Second, these metrics are regressed on debt and equity market size, as well as variables that control for non-market influences on financial reporting.

The sample comprises 78,949 fiscal-year observations during 1992–2003 from 22 countries. It is constructed as follows. First, for all firm/years with data, we obtain net income before extraordinary items X from the Global Vantage Industrial/Commercial file (Data Item 32), and calculate fiscal-year stock returns using year-end prices and dividends from the Global Vantage Issue file. Each firm/year is assigned to a country based on Periodic Descriptor Array 13, indicating the accounting standards used in preparing its financial statements that year.Footnote 18 Second, we calculate price-deflated earnings per share NI t as X t /(N t P t−1), where N is number of shares outstanding, P is stock price and t is fiscal year. Adjustments are made for splits and dividends. Third, we require at least 400 observations per country. This produces a sample of 26 countries with 85,497 firm/year observations. Fourth, we discard four countries (Bermuda, Hong Kong, Switzerland and Taiwan) due to missing control variables (described below), reducing the sample to 82,185 observations. Fifth, we delete the top and bottom percentiles of the earnings and returns variables, further reducing the sample to 79,116 observations. Finally, we only use data for a country in years with at least 25 observations, to allow reliable calculation of annual country mean returns, which we use in calculating mean-adjusted returns R to control for differences in expected return across countries and across years.

4.1 Gain and loss timeliness estimates from earnings-returns regressions

Separately for each country i, we estimate a Basu (1997) piecewise-linear regression of accounting income on stock return, using fiscal-year data pooled across firms and years:

Here i, j and t denote country, firm and year, respectively. R jt is the fiscal-year t stock return of firm j, adjusted for its country annual mean return. RD jt is a dummy variable equaling one if R jt is negative (indicating economic losses), and zero otherwise (indicating economic gains). The coefficient β2i on stock return measures the timeliness of gain recognition in country i. The coefficient β3i on the product of stock return and the return dummy measures the incremental timeliness of loss recognition in that country. Timely loss recognition is measured by (β2i + β3i ) and asymmetrically timely loss recognition implies β3i > 0. Overall income timeliness, for both gains and losses combined, is measured by the adjusted R 2 of the regression.Footnote 19

4.2 Controls for countries’ political and legal systems

We control for several variables that prior studies have to be useful proxies for countries’ political and legal environments. In principle these controls work against our hypotheses, because they likely are correlated with capital market development, which is our underlying dependent variable, but in fact the controls exhibit only weak effects.

The control variables are countries’ legal origins (English, French, German and Scandinavian) and their legal enforcement and investor protection ratings (Rule of Law, Corruption, and Creditors’ Rights). The importance of these variables for financial markets is demonstrated by La Porta et al. (1997, 1998) and Shleifer and Vishny (1997). In a financial reporting context, Ball et al. (2000a, b, 2003) shows that timeliness and conditional conservatism vary with legal origin (a proxy for political influences on financial reporting). Notably, common law countries exhibit more timely loss recognition. Bushman and Piotroski (2006) show that timely loss recognition is affected by the legal environment. We add these control variables to verify that our results are not driven by omitted institutional variables that are correlated with debt and equity market importance.

The Rule of Law variable measures a country’s tradition of law and order. A country with a stronger law and order tradition is likely to have more-developed financial markets and more-effective financial reporting practices. Stronger Rule of Law limits firms’ ability to exploit debt holders, and hence could be associated with the development and comparative size of debt markets. In addition, higher Rule of Law could result in more enforcement of timely loss recognition standards. On the other hand, higher Rule of Law could reduce the demand for conditional conservatism due to substitution effects, by the protection it provides to creditors.

The Corruption variable measures the probability that corrupted governments, officials and special interest groups inhibit financial-market growth through the costs and risks they impose on financial intermediaries and firms (Rajan and Zingales 2003). The efficiency of financial reporting can be impeded by governments, officials and others interfering in accounting standards, in the implementation of standards, or in enforcement by courts and government agencies. Moreover, it might be in the interest of government officials to smooth earnings, and hence to suppress timely loss recognition in a bad year for the economy, to maintain a steady flow of taxes. On the other hand, more corruption might increase the demand for conservatism via substitution, due to the lack of alternative protection for creditors.

The Creditors’ Rights control variable proxies for the extent to which creditors have the right to make and enforce loans, which affects debt market development. Lenders and borrowing firms could be more willing to contract when their rights are better protected by the legal system. As is the case with Rule of Law and Corruption, the effect of the Creditors’ Rights score on timely loss recognition is unclear because it depends on whether timely loss recognition and creditor protection are complements or substitutes for credit markets. It therefore is difficult to predict the coefficient sign for all three measures of the legal environment.

4.3 Control for market-to-book ratio

We also report regressions that control for the market-to-book ratio (MTB). The effect of MTB on the earnings-returns relation can be described in two ways. First, MTB contains information about both expected returns and expected earnings (Vuolteenaho 2002). Second, MTB proxies for the proportion of the variation in the market value of equity that is due to factors (such as synergies and rents) that are not reflected in book value, and hence affect returns but not earnings.Footnote 20

The relation between earnings, returns and MTB can be described as follows. In the basic pricing equation, dividends D are discounted at rates of return R t+i:

Assume D t+j = a t+j · X t+j and that X t+j = b t+j · X t , where X t denotes earnings. Thus, D t+j = a t+j · b t+j · X t . Substituting in Eq. 2 and scaling by P t-1 gives:

Equation 3 implies the relation between earnings and returns depends both on expected returns and on expected earnings.Footnote 21 Vuolteenaho (2000, 2002) shows that the MTB can be decomposed into those two components, expected returns and expected earnings:

Here, lowercase denotes logs, bm t denotes the book-to-market ratio (the inverse of MTB), r t denotes stock return and e * t denotes the book return on equity. Equation 4 suggests that high MTB indicates low expected returns and/or high profitability.

Collins and Kothari (1989) use the intuition described in Eqs. 3 and 4 to conclude that higher MTB results in lower return response coefficients. Roychowdhury and Watts (2007), Collins and Kothari (1989), and Easton and Zmijewski (1989) use the intuition in Eq. 4 to develop predictions about the relation between MTB and the Basu gain and loss recognition coefficients. They observe that some growth options and most synergies that arise from the firm’s collection of tangible and intangible assets are not recognized in its books. Therefore, in a regression of earnings on returns, variation in their values is incorporated in returns but not in earnings, reducing the Basu regression coefficients towards zero.Footnote 22 The variance of “unbooked” gains and losses increases in the MTB ratio, which reflects the proportion of firm value represented by unbooked assets such as synergies and growth potential, so we expect a negative relation between MTB and the coefficients in Eq. 1.

The effect of MTB on the earnings-returns relation applies to both negative and positive returns in the Basu (1997) regression model. Therefore, we expect a negative relation between MTB and both β2i and (β2i + b 3i ) in regression model (1). While we expect the direction of the effect to be the same for both positive and negative returns, its magnitude need not be the same because positive and negative return variances are not equal.Footnote 23 Consequently, we make no prediction for the effect of MTB on the incremental loss recognition slope β3i . We estimate the MTB inverse, the book-to-market ratio (BM), as the median value for all firms and years in each country.Footnote 24 We report below that it is positively correlated with β1, β2, β3, (β2 + β3) and R 2.

5 Results: debt, equity and financial reporting timeliness and conservatism

The following financial reporting properties are estimated separately for each country i from regression (1): β2i (timely gain recognition coefficient); β2i + β3i (timely loss recognition coefficient); β3i (incrementally timely loss recognition coefficient); the regression R 2 i (overall timeliness); and β0i + β1i LF i , where LF i is the loss frequency in country i and is the country mean of RD jt (unconditional conservatism, controlling for contemporary gains and losses). The data are arrayed in Table 1. There is no evidence of outliers in the important variables.Footnote 25

Table 2 reports the correlation between the important institutional variables and the gain and loss timeliness coefficients. At the outset, it is important to note that while the financial reporting properties are correlated with the control variables, their univariate correlations with the debt and equity market size variables are consistent with results from the multivariate regression models that include the controls. For example, the correlation of timely loss recognition (β2i + β3i ) with Debt/GNP is 0.27, but its correlation with Equity/GNP actually is negative, −0.16, consistent with our conclusions below. This gives us confidence that the results for the debt and equity variables in the multivariate regressions are not induced by the controls.

In the multivariate model, each estimated financial reporting property is regressed on the country institutional characteristics:Footnote 26

Results from estimating versions of Eq. 5 are reported in Tables 3–9. In each table, Column (B) reports a regression incorporating the debt and equity variables, with controls for only the three legal origin dummy variables (German origin is the base). This regression has 16 degrees of freedom. Columns (B) through (H) report regressions with controls for the individual legal environment variables: Rule of Law, Corruption and Creditors’ Rights, respectively. Column (I) also controls for BM. The conventional 95% significance level for the t-statistic ranges from 2.12 (for 16 degrees of freedom) to 2.18 (for 12 d.f.).

5.1 Loss recognition timeliness

Table 3 reports results for estimated loss recognition timeliness, (β2i + β3i ). The central result is confirmation of the hypothesis that debt markets and not equity markets are associated with the level of timely loss recognition. The coefficient on debt is positive for all model specifications, with t-statistics ranging from 2.25 to 3.45. A one standard deviation increase in Debt/GNP translates into a 0.08 increase in the regression slope for accounting income on negative stock returns, β2i + β3i , which is large in comparison with the 0.21 mean across countries (Table 1). The relation between debt market size and loss recognition timeliness therefore is in the predicted direction, and economically as well as statistically significant.

In contrast, the coefficient on equity is negative, though it is statistically significant in only two of the nine specifications (t-statistics range from −0.99 to −2.46). The absence of a positive relation is inconsistent with a strict “value relevance” hypothesis that equity markets alone drive the demand for timely loss recognition in accounting.

A significant result is the importance of legal origin in explaining loss recognition timeliness. Controlling for the sizes of their debt and equity markets, German origin countries exhibit the lowest average levels of loss recognition timeliness, followed by French origin countries, consistent with Ball et al. (2000a). Scandinavian and English origin countries are associated with economically and statistically significantly higher levels of timely loss recognition, with dummy intercepts ranging from 0.166 to 0.305 in different specifications, which is large in relation to the mean of 0.21 across all countries (Table 1), and with t-statistics ranging from 2.17 to 3.54. This result is consistent with the conclusion of Artburg (1998, pp. 284–285) that Scandinavian accounting has gravitated from German to Anglo-Saxon approaches to conservatism.Footnote 27 The regressions control for debt and equity market size, so the country effects are due to other factors (e.g., political or tax influences on financial reporting practice).

In contrast, the three variables that control for legal environment contribute little to explaining loss recognition timeliness, both individually and collectively. Their individual coefficients are statistically insignificant: the t-statistics for Rule of Law, Corruption and Creditors’ Rights are 0.60, −0.33 and −0.82, respectively, in columns (B) through (D).Footnote 28 The 49% adjusted R 2 of the column (A) specification omitting the three legal environment controls is exceeded in none of the column (B) through (H) specifications that include them.

When BM is included in the loss recognition regression (column I), the model’s explanatory power increases only slightly. The coefficient of 0.140 on BM has the predicted sign but is not significant (t-statistic of 1.61). The coefficient on debt market size falls, but remains significant. The equity coefficient remains insignificant.

Overall, the results in Table 3 are consistent with the hypothesis that debt markets, not equity markets, are the basic determinant of timely loss recognition. The regression model explains a surprisingly high 44%–52% of the variation in countries’ loss recognition timeliness measures, which is encouraging because the sample is small, and both the dependent and the independent variables are proxies that likely measure their underlying constructs with error. While loss recognition timeliness is correlated with the legal origin control variables, its univariate correlation with the debt and equity market variables (Table 2) is consistent with the results from the multivariate regression model with the controls.

5.2 Gain recognition timeliness

Table 4 reports results for estimated gain recognition timeliness, β2i . We expect debt markets exhibit a lower association with timely gain recognition than reported above for loss recognition. We also expect gain recognition to be independent of equity market size. The results are consistent with these hypotheses. The t-statistics for the debt and equity variables range from −1.71 to 0.33 and −1.97 to 1.26, respectively, none of which is significant. In specifications excluding the BM ratio, the regression model explains only 5%–25% of the variation in countries’ gain recognition timeliness measures, compared with 44%–49% for loss recognition timeliness in Table 3. These full-model results are consistent with the β2i coefficient’s univariate correlation of only 0.02 with equity market size and its negative correlation with debt market size (Table 2).

When BM is included in the gains recognition regression (column I), the model’s explanatory power more than doubles, to 55%. The coefficient on BM is 0.104, which has the predicted sign and is statistically significant (t-statistic of 3.10). It is similar in magnitude to the equivalent estimate of 0.140 in Table 3 for the loss recognition regression. The debt and equity market size variables remain insignificant when BM is added to the gains recognition regression.

5.3 Incremental loss recognition timeliness (conditional conservatism)

Table 5 reports results for estimated conditional conservatism, β3i , the incremental timeliness of loss recognition relative to gain recognition. The t-statistic for Debt/GNP ranges from 2.36 to 3.40, and affirms the importance of debt markets in determining conditional conservatism. As in Table 3, the coefficient on Equity/GNP is negative though not always significant (t-statistic of −0.89 to −2.86). Empirically, debt markets are associated with enhanced conditional conservatism, and equity markets are not.Footnote 29

Conditional conservatism is significantly greater in countries of English and Scandinavian legal origin, consistent with Ball et al. (2000a). When BM is included in the incremental loss recognition regression (column I), the model’s explanatory power is essentially unchanged. The coefficient on BM is insignificant (t-statistic of 0.40), reflecting the almost symmetric effect of BM on the gain and loss recognition coefficients, reported earlier in Tables 3 and 4.Footnote 30 Overall, the regression models describing incremental timeliness of loss recognition perform well, with adjusted R 2 statistics of 40%–56%.

5.4 Overall gain and loss recognition timeliness

Table 6 reports results for overall gain and loss recognition timeliness, measured by the R 2 i of the individual-country earnings-returns regression (1). In its linear form, this is commonly espoused as a metric of financial reporting informativeness to investors (Lev 1989), and is viewed as a measure of the “value relevance” of earnings. The results generally are consistent with those in previous tables, though there are some differences.

The coefficient on debt is positive in all nine regressions, though it is statistically significant in two only. We interpret this weak positive relation as a combination of the strong positive relation between debt and timely loss recognition (Table 3) and the absence of an equivalent relation with timely gain recognition (Table 4). The coefficient on equity flips sign across the regressions and is not significant in any, indicating that overall reporting timeliness is not associated with the importance of a country’s equity markets. This result is consistent with the weak relation reported above between equity market size and both timely loss and timely gain recognition (Tables 3 and 4), and is inconsistent with the value relevance hypothesis.Footnote 31

The French, English and Scandinavian dummies are positive in all specifications, indicating that countries with German legal origins have the lowest overall earnings timeliness, consistent with Ball et al. (2000a). Overall timeliness seems to be affected by the legal environment, in that the Rule of Law, Corruption and Creditors’ Rights dummy variables all are significant when considered individually, with t-statistics of 2.35, 2.42 and −2.05, respectively. Consequently, when Rule of Law, Corruption and Creditors’ Rights are included in the model, the explanatory power increases from 26% to 41%.

5.5 Unconditional conservatism

Basu (1997, p. 4) defines conservatism as “accountants’ tendency to require a higher degree of verification for recognizing good news than bad news in financial statements... earnings reflects bad news more quickly than good news.” Ball and Shivakumar (2005) and Beaver and Ryan (2005) describe this as “conditional conservatism,” in contrast with “unconditional conservatism” which is an accounting bias toward reporting low earnings and book values of stockholders equity.Footnote 32 Conditional conservatism is the stricter concept, requiring the accounting bias to be conditional on the sign of contemporaneous economic income, and hence to be a function of new information.Footnote 33 This requirement is not satisfied by accounting biases such as routinely over-expensing, routinely expensing early or routinely deferring revenue recognition, independent of economic income.

We study unconditional conservatism for several reasons. First, the distinction between conditional and unconditional asymmetry is important in any contracting context, including debt, because unconditional conservatism is not a function of new information. Ball (2004) and Ball and Shivakumar (2005) argue that gains in contracting efficiency therefore can arise only from conditional conservatism. If firms simply reported unconditionally low numbers, rational economic agents would try to “contract around” the bias. For example, borrowers and lenders alike would realize that assets are unconditionally under-stated, and would set leverage covenants appropriately. Unconditional biases thus are contracting-neutral at best.

Second, standard setters traditionally have not clearly distinguished the two concepts of conservatism, and increasingly have viewed conservatism negatively. For example, in Concepts Statement No. 2, FASB (1980) defined conservatism as “prudent reaction to uncertainty to try to ensure that uncertainty and risks inherent in business situations are adequately considered,” and then stated (\(\P\)93): “Conservatism in financial reporting should no longer connote deliberate, consistent understatement of net assets and profits.” The International Accounting Standards Board (2001, \(\P\)37) reiterated these views recently, though it replaced the unfashionable term “conservatism” with “prudence.” None of these statements refers to the gain/loss asymmetry in financial reporting practice observed by Basu (1997), or the rationales for it.

Third, the unconditional definition of conservatism has been employed in much prior literature, including the international accounting literature (e.g., Gray 1980). Notably, creditor protection has been offered as the main explanation for the conservative balance sheets of German companies in particular.Footnote 34 Under the vorsicht principle, German firms historically have engaged in unconditionally conservative practices such as charging future operating expenses against current-period income. We argue that this would not increase either the efficiency of debt contracting or creditor welfare.

We therefore test the hypothesis that unconditional conservatism, in the form of low earnings and book values independent of economic outcomes, does not increase debt contracting efficiency and hence is not demanded by debt markets. A testable prediction is that unconditional conservatism is not associated with debt market size, controlling for conditional conservatism.

A test of this prediction is obtained by regressing the mean intercept from (1) on debt and equity market size. The mean intercept is β0i + β1i LF i , where LF i is the frequency of losses in country i, defined as the country mean of RD jt . The Basu regression (1) controls for stock returns and the sign of stock returns, so the mean intercept captures the mean reported net income relative to stock returns, after controlling for conditional conservatism. A negative coefficient on debt is predicted if unconditional conservatism per se is demanded by debt markets.

The results reported in Table 7 are consistent with the hypothesis that debt markets do not demand unconditional conservatism. The coefficient for the mean intercept β0i + β1i LF i regressed on debt is positive and statistically insignificant (coefficient of 0.053, t = 1.68). Equity also is insignificantly associated with unconditional conservatism (coefficient −0.007, t = −0.35). These results suggest the origin of unconditional accounting conservatism lies outside the capital markets, perhaps in book-tax conformity (Ali and Hwang 2000), in the capacity it gives managers to draw on hidden reserves at a later date to hide losses (Schneider 1995; Ball 2004), in taxation, or in political costs of reporting higher earnings (Gilman 1939; Watts 1977; Watts and Zimmerman 1986).

This measure of unconditional conservatism is noisy because it is based on a maximum of only 12 annual earnings observations. For example, if firms in a particular country have reported low earnings in years prior to the sample period, clean surplus accounting could require them to report high earnings during the sample years, other things equal. This provides a motivation for studying the book-to-market ratio as an alternative dependent variable.

5.6 Book-to-market ratios

We next report results with book-to-market ratio as the dependent variable, as distinct from the prior tables where it is a control variable. Pae et al. (2005) and Roychowdhury and Watts (2007) document a relation between book-to-market ratios and conditional and unconditional conservatism. Book-to-market is referred to as a measure of unconditional conservatism by Beaver and Ryan (2005). To the extent that book-to-market reflects unconditional conservatism, in the form of low book values independent of economic outcomes, we expect it does not increase debt contracting efficiency and hence is not demanded by debt markets. To the extent the ratio reflects conditional conservatism (i.e., decreases in book value that are correlated with decreases in economic value, and hence contain information), we expect it is associated with the importance of debt markets.

The results in Table 8 show a positive relation between BM and both our debt and equity variables, but their statistical significance is relatively weak. The t-statistic varies from 0.71 to 1.52 for the debt variable and from 0.88 to 2.21 for the equity variable. The explanatory power of the model never exceeds 24%, one half of which is due to Rule of Law and Corruption (compare Columns (E) and (F)). Overall, we find no significant relation between this measure of conservatism and either debt or equity markets. One interpretation of this result is that international variation in book-to-market ratios is dominated by differences in unconditional, not conditional, reporting conservatism.

5.7 Weighted least squares

To address the fact that the dependent variables are estimates for countries with different sample sizes, we estimate Weighted Least Squares (WLS) regressions. Each country’s observation is weighted by the inverse of the square of the standard error of its β3i estimate. This is expected to increase the efficiency of the regression models by assigning lower weight to country observations that are measured with higher error. All WLS results are consistent with, and stronger than, the OLS results in Tables 1–7. For brevity, in Table 9 we present only the results with β3i and β2i + β3i as dependent variables. These results are even stronger than the OLS equivalents reported in Tables 3 and 5. The explanatory power of the model increases from 52% in Table 3 Column (I) and 53% in Table 5 Column (I), to 73% and 80% in Table 9. The debt variable loads positively, with increased t-statistics of 3.24 to 4.69 across models. The importance of the legal origin dummies in Tables 3 and 5 above is reaffirmed in Table 9. We conclude that our results are not due to estimation error in the Basu regression coefficients.Footnote 35

5.8 Deleting individual countries

The results are robust with respect to marginal changes in the sample. This alleviates the concern that the 22-country estimates are unduly influenced by individual countries. We create 22 different samples, each of 21 countries, by deleting a country at a time. We find virtually no changes in the results. The significance of the debt variable is maintained in 19/22 instances; in the other three instances (deletions of Denmark, Singapore and Thailand, respectively), the debt variable is significant at the 10% level. The equity variable remains insignificant in all except one instance (deletion of Sweden), where it is significantly negative. The behavior of the control variables remains unchanged also. The dummies for English and Scandinavian countries are significantly positive in all except three and four cases, respectively, and in the majority of these the significance is maintained at the 10% level. There is no evidence of “knife-edge” effects in the data, or that the results and their significance are volatile.

5.9 Two-year Basu slopes

In the previous tables we estimate Eq. 1 from annual earnings and returns. However, expected slope coefficients depend on the intervals over which returns and earnings are measured (e.g., Kothari and Sloan 1992; Basu 1997; Roychowdhury and Watts 2007). While we prefer annual intervals because they directly address the issue of timeliness of annual earnings, we re-estimate Eq. 1 using two-year-windows for both returns and earnings as in Roychowdhury and Watts (2007).

The sample sizes fall dramatically because two consecutive calendar years of both earnings and returns data now are required. We therefore drop the requirement of at least 400 total observations per country over the entire period, because that would decrease the number of countries for the cross-sectional analysis from 22 to only 10. Even with this compromise, which allows us to use all 22 countries, the total sample falls from 78,949 one-year observations to 33,494 two-year observations.

The average country’s asymmetric timeliness coefficient β3i declines with the longer horizon, consistent with Basu (1997) and Roychowdhury and Watts (2007), and the standard errors of the coefficients of Eq. 1 almost double on average. We therefore use a WLS model for estimating Eq. 5, using the inverse of the squared standard error of β3i to weight each country’s observation, as in Sect. 5.7. The results (not reported) are qualitatively the same as the results using one-year horizon results. In particular, the results for debt do not change, insofar as debt is positive and statistically significant for β3i as well as β2i + β3i .

5.10 CIFAR scores

We study the financial reporting scores developed by the Center for International Financial Analysis and Research (CIFAR 1995) to help validate the association-study results reported above. A CIFAR score is a reporting quality index, based on the exclusion or inclusion of 85 items in individual firms’ annual reports. Despite their seemingly arbitrary nature, country-level scores, aggregated across firms, have been widely used to measure financial reporting quality (e.g., La Porta et al. 1998; Bushman et al. 2004).

Results are reported in Table 10. Panel A covers 21 of the 22 countries in previous tests (excluding Indonesia, for which a CIFAR score was not available), and Panel B reports results for a larger sample of 35 countries with available CIFAR data. English and Scandinavian origin countries have the highest CIFAR scores, other things equal, and French and German origin countries have the lowest. CIFAR scores are positively but weakly related to debt (t-statistics ranging from 0.72 to 2.08) and even more weakly to equity (t-statistics of 0.03 to 1.43). Due largely to the legal origin variables, the model explains more than 50% of the variation in scores. The results are not materially affected by the control for BM. These results are very similar to those reported in Table 6 for the earnings-returns R 2 measure of overall gain and loss recognition timeliness, our measure which corresponds most closely to what CIFAR scores capture. This gives us added confidence in the validity of the country-level association-study measures.

6 Conclusions and discussion

In concluding their survey of the “value relevance” literature, Holthausen and Watts (2001, p. 65) call for research on the following question: “Is the form and content of the balance sheet largely driven by the demands of debtholders as opposed to equity investors?” Despite the centrality of this issue to accounting, we are aware of no direct test of the roles of debt and equity in shaping financial reporting practice. We conduct a direct test that utilizes variation among countries in debt market and equity market demands on country-level financial reporting. Within-country research designs suffer from homogeneity across firms of regulatory regime, of litigation regime, and of financial reporting and auditing requirements, but cross-country designs offer an opportunity to observe the separate effects of debt and equity market demands.

Our research design regresses individual-country measures of gain and loss recognition timeliness, and overall timeliness, on the sizes of the countries’ debt and equity markets. The rationale is that timely financial reporting is a costly activity, and the quantity of it in observed in practice should depend on demand. If timely gain and/or loss recognition is in lower demand in a country with poorly developed capital markets, that country is less likely to expend costly resources in implementing it. Our measure of demand is market size.

Our analysis of 78,949 annual earnings observations from twenty-two countries supports the hypothesis that important properties of financial reporting originate in the reporting demands of debt markets, but not of equity markets. Gain and loss recognition timeliness, as well as overall reporting timeliness, are not associated with equity market size. In contrast, timely loss recognition, overall timeliness and conditional conservatism (timelier loss recognition than gain recognition) are associated with debt market size. The loss recognition effect is economically as well as statistically significant, in that a one standard deviation increase in a country’s Debt/GNP is associated with a 0.08 increase in the regression slope for accounting income on negative stock returns, which is large in relation to the cross-country mean of 0.21. We conclude that these important properties of financial reporting exist more for their role in efficient debt contracting than to inform equity markets.

These results are inconsistent with the basic premise of the influential “value relevance” school of accounting thought, in which financial reporting exists primarily to inform equity markets. This viewpoint is implicit in studies that use the R 2 measure of association between market prices and financial statement variables as a financial reporting criterion. In contrast, the results are consistent with the “costly contracting” school of accounting thought, and in particular with the hypothesis that the debt market exerts a substantial impact on accounting practice. This hypothesis has origins at least as early as Gilman (1939), and more recently has been proposed by Watts and Zimmerman (1986), Watts (1993, unpublished manuscript; 2003a, b) and Holthausen and Watts (2001). We argue that loss recognition timeliness increases the efficiency of debt contracting, makes debt a more efficient form of financing, and hence is associated with larger debt markets. That is, we hypothesize that an important source of demand for financial reporting lies in debt markets.

We are not proposing that the equity market does not prefer more timely financial reporting, other things equal. Of course it does. But association studies cannot address this issue, because they control for the total amount of information, and do not consider either financial reporting costs or the effect of financial reporting timeliness on non-financial disclosures. Nor are we proposing that the debt market does not prefer more timely gain recognition, other things equal. Of course it does. But timely gain recognition is a costly economic activity and hence the amount of it supplied to the debt market should reflect demand, which is not symmetric with the demand for timely loss recognition.

The hypothesis does not attempt to distinguish between two explanations concerning the sequencing of supply and demand. One sequence is that financial reports exhibiting timely loss recognition are supplied by firms and their auditors, and this facilitates the creation of debt markets. The alternative sequence is that debt markets put pressure on firms and their accountants, either through litigation or regulation, to increase loss recognition timeliness. Either way, the ultimate source of the demand for financial reporting practice is the debt market.

Similarly, we note that correlated institutional variables do not necessarily alter our conclusions. Institutional complementarity implies the existence of jointly caused and hence correlated variables in these contexts, and it is not always meaningful to assign causation to individual variables. For example, we are not unduly concerned that cross-country differences in firm characteristics such as capital intensity could be correlated with both timely loss recognition and debt market size, because the characteristics of listed firms are jointly determined with financial reporting and market characteristics. Developed capital markets and timely loss recognition might be necessary conditions for listing capital-intensive firms. Equally, the existence of capital intensive firms and developed markets might be necessary conditions for timely loss recognition. Because one therefore has to be careful to avoid over-controlling for endogenously determined variables, we would have mixed views on our regression controls for market-to-book ratios if they had a substantial effect on the results. Fortunately, they did not.

Nevertheless, we caution readers that ours is a cross-sectional international research design, and hence correlated omitted variables cannot be ruled out as a problem. Fortunately, many of these variables seem more likely to affect unconditional conservatism than its conditional cousin, asymmetrically timely loss recognition. For example, the use of debt could be correlated internationally with corporate tax rates, which in turn could be correlated with the extent of government involvement in financial reporting and hence with book-tax conformity rules.Footnote 36 However, the financial reporting practices leading to conditional conservatism, such as timely loss provisioning and asset impairment, generally are not allowed for income tax purposes. Tax rules generally do not allow deductions based on downward revisions of expectations concerning future cash flows, and generally require losses to be realized for them to be tax-deductible. Further, book-tax conformity would be more likely to produce unconditional conservatism, because conservative tax reporting practices such as generous depreciation allowances are largely unrelated to the sign of contemporaneous stock returns—and hence are more likely to affect the intercepts but not the slopes in a Basu (1997) regression. In our study, international tax differences thus are more likely to affect the legal origin dummy variables than the loss recognition slopes.

Another possible omitted variable arises from corporate governance and management compensation. Ball (2001, p. 139) argues that timely loss recognition makes managers “more likely to incur the personal cost of abandoning losing investments and strategies and less likely to invest in negative-NPV projects that give them personal utility.” Internationally, the extent of reliance on financial reporting—and hence timely loss recognition—to monitor and discipline professional managers seems likely to be positively correlated with the depth of equity markets. It is particularly likely to be correlated with our measure of market depth, which excludes large shareholders such as controlling families who can monitor managers more directly as “insiders,” rather than via financial reporting. It therefore is surprising that we do not observe a positive correlation between timely loss recognition and our measure of equity market depth.

Shareholders have an indirect interest in timely loss recognition via its effect on the efficiency of debt contracting and hence the cost of capital. We do not view this as an omitted effect because it should increase in the amount of debt: that is, it is a component of the debt-induced demand for financial reporting timeliness. To the extent it is a function of the size of the equity market, it too predicts a positive slope on the equity variable, whereas the observed slope is negative.

Notes

Gilman (1939, p. 232), Jensen and Meckling (1976, p. 338), Smith and Warner (1979), Leftwich (1983) Watts (1977, 2003a, b) and Holthausen and Watts (2001) address the relation between financial reporting and debt contracting. Basu (1997) is the first to study timely loss recognition, and Ball (2001), Ball et al. (2003) and Ball and Shivakumar (2005) address its debt-contracting role.

Association-study metrics are of interest to the accounting profession (for example, the association-study R 2 is a type of information-market share variable), though the usefulness of financial reporting likely is not a monotone increasing function of R 2 (Ball 2001).

An effective institutional structure is easily taken for granted by participants in a highly developed economy. US participants have been alerted recently to Sarbanes–Oxley Act compliance costs, yet these are but a subset of the total costs of an effective reporting system. Lesser-developed economies do not devote the same amount of resources to institutional development and operation as is familiar in countries with more developed financial systems. See Ball (2001) for an analysis of efficient financial reporting systems in developing economies.

Some conclusions can be drawn from single-country studies, for example that the asymmetry reported by Basu (1997) for US firms is consistent with debt exerting an important influence on financial reporting (Holthausen and Watts 2001), but the evidence underlying these conclusions arises from what in essence is a single observation.

Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 1, FASB (1978, \(\P\)30).

Political solutions differ from market solutions, and vary internationally. We therefore control for various country-level system variables when testing the influence of debt and equity markets on financial reporting.

The notion of earnings timeliness was introduced by Ball and Brown (1968), who concluded (p. 176): “the annual income report does not rate highly as a timely medium.” Nevertheless, subsequent literature emphasized the informativeness of earnings and focused on event-day price responses to earnings announcements, which (while statistically significant in large samples) are a minor component of the variance of annual and longer-horizon stock returns. Lev (1989) reiterated the low timeliness of earnings, expressing in terms of the R 2 between earning and contemporaneous returns, and called (section 8) for research to improve the quality of financial information, presumably to increase the R 2. Similar views are evident in the literature as far back as Canning (1929), and were central to the debates in the so-called “golden era” of accounting research (for example, Chambers 1966).

Differential costs of processing financial-statement versus other information do not affect this argument, because the amount of information incorporated in prices reflects processing costs. Second-order effects could arise if, for some reason, there were non-optimal quantities of either financial-statement or other information in supply, for example due to agency costs or political intervention (for which we control). Shareholders have indirect interests in reporting timeliness that we discuss below.

This should be obvious from a cursory review of the results in studies such as Bernard and Thomas (1989, Figs. 1–4), even though the portfolios in these studies are formed on the basis of common earnings behavior and hence are poorly diversified.

Presumably, this is because: (1) managers who have made negative-NPV decisions in the past are more likely to keep making bad decisions in the future, due for example to poor strategies and/or low ability or effort; and (2) managers in firms who hold “out of the money” options due to past losses have incentives to gamble on new investments and acquisitions even if they have a negative expected NPV.

Losses followed by gains can be handled by lenders electing not to exercise their decision rights. Some demand for timely gain recognition is generated by debt repricing (Asquith et al. 2005) and by debt selling substantially below face value. The argument is not that there is no debt demand for timely gain recognition; it is that there is less demand for it than for losses.

No allowance is made for cross-listing, which constitutes a bias against our hypotheses.

Consistent with the interpretation in Ball and Kothari (2007, unpublished manuscript), we model this as a property of equilibrium income recognition practices in each country. Roychowdhury and Watts (2007) model it as an errors-in-variables issue.

More precisely, the ratio of the variances of booked and unbooked economic gains need not equal the corresponding ratio for booked and unbooked economic losses. Here, “unbooked” refers to gains and losses that are not recorded in contemporary accounting income, such as revisions in the value of economic rents.

Our results are robust with respect to alternative specifications of BM. We also find similar results when we exclude two countries (Brazil and Indonesia) with unusually low values for BM.

The market/book ratio has extreme values for Brazil and Indonesia, perhaps due to inflation, but is used only in some specifications, and then as a robustness control (without materially influencing the results).

In contrast to Bushman and Piotroski (2006), who use debt/equity ratios, our regression includes both debt and equity as independent variables because our goal is to assess their individual roles. For example, a positive coefficient on debt/equity can indicate a positive association with debt, a negative association with equity, or both.

See also Alexander and Schwencke (2003).

This result implies that, for the purpose of predicting countries’ earnings qualities measured in terms of loss recognition timeliness, a simple classification of countries by legal system origins (e.g., Ball et al. 2000a) performs better than more specific measures of legal environment (e.g., Leuz et al. 2003). The result is insensitive to including various combinations of the legal environment variables in the regression.

The negative slope for equity cannot be explained by incremental loss recognition sensitivity encountering increasing marginal costs, because it does not occur by equity market size increasing timely gain recognition: it occurs by equity market size decreasing timely loss recognition. We are aware of no version of the “value relevance” hypothesis that is consistent with this result.

It is consistent with the hypothesis that the primary role of accounting earnings in equity markets is not to inform them in a timely manner, but to subsequently confirm or contradict managers’ non-financial forecasts and disclosures, and hence exert a discipline on them. See Ball (2001, pp. 133–138).

We view these as economically different concepts, as distinct from measures, of conservatism (cf. Roychowdhury and Watts 2007), because they have substantively different economic and political roles. We view unconditional conservatism as arising from tax, political costs and managerial self interest, and conditional conservatism as arising from efficient debt and governance contracting. Basu (1997, p. 8) draws a distinction between the concepts, though he does not use this terminology and clouds the distinction in his citation (p. 7) of FASB (1980, para 95). Ball et al. (2000a, n. 15) make the distinction, but describe it inaccurately as “income statement” versus “balance sheet” conservatism. Beaver and Ryan (2005) also use the terms “conditional” and “unconditional.” Confusion of the unconditional and conditional versions of conservatism is evident as early as Gilman (1939, p. 130) and APB Statement No. 4. The concepts clearly are related (Ball et al. 2000a, fn. 15; Roychowdhury and Watts 2007).

Under clean surplus accounting, reporting low book values implies reporting low average net incomes, though not necessarily in any given year and hence not necessarily related to contemporary economic losses. Unconditional conservatism also creates “hidden reserves” (“cookie jar reserves”) that allow firms to increase earnings in loss periods. See Schneider (1995, pp. 136–137); Ball et al. (2000a, fn. 15); and Ball (2004, pp. 126–131).