Abstract

We argue that high accruals are likely to be the outcome of rules with an income statement perspective, while low accruals are likely to be the outcome of rules with a balance sheet perspective, and that this has implications for the properties of earnings. Specifically, earnings persistence is affected both by the magnitude and sign of the accruals. Accruals improve the persistence of earnings relative to cash flows in high accrual firms, but reduce earnings persistence in low accrual firms. We show that the low persistence of earnings in low accrual firms is primarily driven by special items. We then show that special item-low accrual firms have higher future stock returns than other low accrual firms. This is consistent with investors misunderstanding the transitory nature of special items. Further analysis reveals that special item-low accrual firms have poor past performance and declines in investor recognition (analyst coverage and institutional holdings). Special items continue to explain future returns after controlling for these factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Accrual adjustments made by firms are fundamentally linked to underlying economics. Large positive accruals are indicative of firms increasing their asset bases, while large negative accruals are indicative of firms reducing their assets and exiting businesses. In this paper we suggest that the applicable accounting rules reflected in accruals differ for firms increasing or reducing their asset bases and that this has implications for earnings persistence. We then examine implications of this insight for the accrual anomaly documented by Sloan (1996).

Firms with large positive accruals are investing in assets, generating sales, and expanding their businesses. Due to the conservative nature of accounting and reliability concerns, accrual accounting generally does not fair-value future benefits on the balance sheet. Instead, many of these investment cash flows are expensed immediately and only some are capitalized as assets. Thus, large positive accruals are likely to occur in firms with negative transitory cash flows. In such firms, accrual adjustments are likely to improve earnings persistence since they mitigate the transitory effect of these negative cash flows on earnings.

In contrast, large negative accruals are indicative of firms reducing assets and downsizing. As a firm exits lines of businesses, assets such as inventory, goodwill, property, plant, and equipment are likely to have market values less than their book values. In such circumstances, accounting rules focus on correcting the balance sheet and assets are written down to their fair value. These accrual adjustments result in the recording of impairment charges, restructuring charges, and other special items in earnings. Therefore, large negative accruals are less likely to be the consequence of the firm recording large positive transitory cash flows as liabilities (i.e., accruals playing a matching role). Instead, they are more likely to reflect transitory “special items” adjustments that reduce earnings persistence.

The focus of our paper is to investigate the implications of balance sheet adjustments relating to special items for the accrual results documented by Sloan (1996). Sloan (1996) shows that earnings composed of accruals are less persistent than earnings composed of cash flows. We point out that different accounting perspectives govern the rules creating high and low accruals. Therefore, earnings persistence will be affected both by the magnitude and sign of the accruals. Specifically, management of low accrual firms are more likely to be making accrual adjustments to revalue net assets. Therefore, low accrual firms have more transitory earnings than high accrual firms because of negative special items.

Sloan (1996) provides evidence consistent with investors misunderstanding the transitory nature of the accrual component. If investors misunderstand the transitory nature of the accrual component, then isolating low accrual firms that have more transitory accruals should improve the returns to the accrual anomaly. Our results support this prediction. We find that low accrual firms with large negative special items consistently earn higher positive returns than other low accrual firms. When we split the lowest decile of accruals into those firms reporting special items and those that are not, we find that special item firms earn a size-adjusted return of 11.7% over the following year, while firms with no special items earn a size-adjusted return of only 1.4%. In addition, we find that special item-low accrual firms outperform other low accrual firms in 11 of the 15 years that we analyze.

Special items are typically recorded as separate line items on the income statement and management have incentives to highlight their transitory nature. In addition, analysts typically exclude special items from their forecasts of “pro forma” earnings and prior research suggests that investors respond more strongly to pro forma earnings (Bradshaw & Sloan, 2002; Bowen, Davies, & Matsumoto, 2005) and even ignore excluded items that are recurring (Doyle, Lundholm, & Soliman, 2003). Therefore, it is somewhat surprising that our findings suggest that investors view special items as having more implications for future earnings than they actually do. We provide further analysis to gain insights into why investors underprice these firms.

We document that low accrual firms with special items have performed very poorly over the past year. Sales have declined by 7%, 97% of the firms are reporting losses, and abnormal stock returns over the prior year are −27%. Theories from psychology (Kahneman & Tversky, 1982) suggest that investors may overweigh recent information and underweigh base rate data and as a consequence underprice firms with poor past performance (e.g., De Bondt & Thaler, 1985; Lakonishok, Shleifer, & Vishny, 1994).

If investors believe that this poor performance will continue, then analysts could drop coverage of these firms and institutional investors could sell their holdings. Lehavy and Sloan (2004) show that analysts are dropping coverage and institutional holding are declining in low accrual firms. We document that the decline in coverage and holdings is almost entirely due to firms reporting special items. These results are consistent with investors requiring a higher expected return to hold special item-low accrual firms because they have low investor recognition. Footnote 1 We also investigate analysts’ long-term growth forecast errors and find that they are pessimistic for low accrual firms. Footnote 2 However, we find that the analysts that continue to follow special item-low accrual firms are no more pessimistic than other analysts following low accrual firms.

Finally, we investigate whether analysts and investors avoid these firms because they view them as fundamentally more risky and difficult to value. Fundamental risk is risk that is specific to the firm that should be diversifiable. We measure two aspects of fundamental risk. The first is bankruptcy risk. Special items are indicative of a firm exercising the abandonment option (Hayn, 1995) by downsizing and exiting businesses. If the turn-around is not successful the firm may face bankruptcy. We find that special item-low accrual firms have higher probabilities of bankruptcy and a larger proportion of these firms delist for performance related reasons. However, a simple screen of avoiding stock with share price less than $1 mitigates this difference. Footnote 3

The second measure of fundamental risk we examine relates to information uncertainty. When it is difficult to obtain information about a firm or there is more disagreement among investors about the value of a firm, an individual investor may require a premium to hold the stock. We use share turnover to measure the degree of disagreement among investors about firm value (e.g., Beaver, 1968; Karpoff, 1986; Kim & Verrecchia, 1991) and document that it is significantly higher for special item-low accrual firms. We also investigate analyst coverage since this is likely to be correlated with the degree of available information about a stock. However, special item-low accrual firms tend to be larger than other low accrual firms and we find they have greater coverage.

Our results indicate that special items continue to explain future returns to low accrual firms after controlling for the factors measured above. Overall, the picture that emerges from our tests is that the recording of special items helps identify the end of the negative price momentum cycle (e.g., Lee & Swaminathan, 2000). Special items reflect underlying economics and are indicative of firms that have over-invested in strategies that have not worked. As a consequence, these firms have performed poorly and the recording of special items is indicative of management taking action to turn the firm around. However, investors appear to overweigh the probability that the firm will be unsuccessful. On average, special item-low accrual firms end up “turning themselves around” at higher rates than expected by investors and as a consequence show improved stock price performance.

In the next section we discuss our predictions and how our paper relates to prior research. Section 2 provides our sample selection and Section 3 presents our results. Our conclusions are in Section 4.

1 Predictions and related research

Accounting is fundamentally linked to underlying economics. A firm that is raising capital and growing will also be a firm that is recording large positive accruals relative to assets. In contrast, a firm that is declining or downsizing will be recording large negative accruals relative to assets. The philosophy behind the accounting rules that apply to growing and declining firms differ fundamentally and this difference likely stems from the historical emphasis on reliability and conservatism in accounting.

Consider a growing firm that is recording the net acquisition of assets. The accounting rules governing the recognition of assets tend to capitalize past expenditures. Accounting is not forward looking for firms with growth opportunities. The rules instead tend to delay the recognition of certain expenditures until the associated revenue is recognized (i.e., adopt an income statement perspective). Thus allowable accruals adjustments are likely to reduce the effect of negative transitory cash flows on earnings.

P1a

Earnings are more persistent than cash flows in high accrual firms.

P1b

Accruals and cash flows are negatively correlated in high accrual firms.

The application of accounting rules for declining firms is fundamentally different from those for firms increasing their assets bases. When firms are exiting businesses, selling off their inventory, downsizing and undertaking restructurings, the accounting rules are forward looking and focus on correcting the balance sheet. To avoid assets being overstated or liabilities being understated, accounting rules require firms to revalue assets and liabilities. Footnote 4 As pointed out by Schipper and Vincent (2003), the more assets and liabilities that accounting rules mark to fair value, the more earnings will reflect changes in fair value, and so the lower the persistence of earnings. In contrast, cash flows are not affected by “fair-value” accounting rules.

P2a

Earnings are less persistent than cash flows in low accrual firms.

In addition, when firms are downsizing they are likely to be generating low cash flows from their asset base. A fair-value perspective requires the firm to forecast the entire stream of future lower cash flows and recognize the present value of the decline in the current period. This suggests that accruals no longer perform their “matching” function and will either exhibit no correlation or a positive correlation with cash flows.

P2b

Accruals and cash flows are positively correlated in low accrual firms.

One way to identify accruals that are made to “correct” the balance sheet is to focus on firms reporting special items in their income statement. Special items typically result from accrual adjustments for impairments, write-downs or write-offs and restructuring charges. Prior research has emphasized the transitory nature of special items (e.g., Fairfield, Sweeney, & Yohn, 1996) and the classification itself is made to help financial users distinguish them from other earnings components. Our focus is to show that special items are correlated with the magnitude of accruals and are a key driver of the low persistence of earnings in low accrual firms. Note that we do not attempt to distinguish whether reported special items are due to earnings management (taking a “big bath”) or underlying economics. For our test this distinction is unimportant since both scenarios predict lower earnings persistence.

P3

The low persistence of earnings in low accrual firms is due to special items.

Sloan’s (1996) results suggest that investors underweigh the cash flow component and overweigh the accrual component’s implications for future earnings. If investors misunderstand the nature of accruals, then the recording of special items (which are particularly transitory) is likely to result in relatively more misvaluation. Therefore, firms with low accruals due to the recording of special items could be important for explaining the high future returns to low accrual stock.

P4

Low accrual firms with special items earn higher future returns than other low accrual firms.

Of course, management has incentives to highlight the transitory nature of special items to investors. If management successfully performs this task then we should not find support for P4 and observe a relation between special item-low accrual firms and future returns. In fact, researchers have pointed out that managers have incentives to argue that special items are more transitory than they actually are. For example, a growing area of research examines pro forma versus GAAP earnings (e.g., Bradshaw & Sloan, 2002). One component of these excluded expenses are typically special items. Doyle et al. (2003) study the implication of expenses excluded from pro forma earnings for future returns. They document negative returns for firms in the highest decile of excluded expenses. This is exactly opposite to our prediction and is consistent with management convincing investors that certain recurring expenses are non-recurring. However, Doyle et al. (2003) show that their hedge return is driven by the difference between total exclusions and special items (GAAP earnings—IBES earnings—special items). They do not find a significant negative association between special items and future returns. One potential explanation for why they do not find a result for the special item firms is likely to be due to the type of firm that reports pro forma earnings. Typically firms reporting pro forma earnings are high growth firms (Lougee & Marquardt, 2004). These firms are likely to have positive accruals and so the transitory nature of special items could be offset by the future reversals of positive accruals. Our results for high accrual firms with special items are broadly consistent with this conjecture.

Our research relates to several other streams of research. Burgstahler, Jiambalvo, and Shevlin (2002) investigate the extent to which security prices reflect the implication of special items for future earnings. They find that the market underestimates the reversal of special items in the year-over-year quarterly statements. They find that a trading strategy consisting of a long position in firms reporting negative special items and a short position in firms reporting positive special items earns a significantly positive 3-day return of 0.67%. They point out that the return is statistically significant, but economically small. Our research differs from their work in two ways. First, our focus is on determining whether special items are important for understanding the lower persistence of the accrual component relative to the cash flow component of earnings documented by Sloan (1996). Second, we examine the implications of special items for the accrual anomaly. Burgstahler et al.’s focus is primarily related to the post-earnings announcement drift.

Chan, Chan, Jegadeesh, and Lakonishok (2006) investigate whether high accrual firms have large income-decreasing special items in the following year. They find some evidence consistent with this conjecture and interpret this finding as the reversal of earnings management in the prior year. However, they do not investigate or address the contemporaneous relation between special items and low accrual firms.

Richardson, Sloan, Soliman, and Tuna (2005) find that less reliable accruals result in lower earnings persistence and investors do not fully anticipate the lower earnings persistence. Two accrual categories of low reliability are change in current operating assets (COA) and change in non-current operating assets (NCOA). Change in COA is dominated by receivables and inventory. Change in NCOA is dominated by PPE and intangibles. Both changes of COA and NCOA could reflect write-downs due to special items. They do not address whether there is any systematic difference between low and high accrual firms in terms of changes of COA and NCOA, nor do they investigate the role of special items. In this paper we investigate both measures of accruals and show that considering special items is important for understanding earnings persistence and future stock returns.

We should also point out that throughout the paper all variables are scaled by average assets. Therefore, we focus on the persistence of various measures of return on assets (see Fairfield, Whisenant, & Yohn, 2003b). For simplicity however, we refer to these variables by the numerator’s name.

2 Data

We obtain financial data from the Compustat annual database. Stock return data are obtained from the CRSP daily stock returns files. The resulting sample covers all firm-years with available data on Compustat and CRSP for the period 1988–2002. Footnote 5 Our analysis is restricted to observations after the release of SFAS 95 in order to calculate accruals from the statement of cash flows. We do this since Hribar and Collins (2002) argue that a more accurate measure of cash flows is obtained using this method. We exclude financial institutions from our analysis (SIC codes between 6000 and 6999) because the distinction between operating and investing activities is not clear in these firms. This is primarily a concern for our operating accrual measure. We remove firm-year observations with missing data on Compustat that are necessary to calculate the primary financial statement variables used in our tests. We use Compustat special items (Item #17) and replace missing values of special items with zero.

We use two definitions of accruals. In the spirit of the recommendations made by Hribar and Collins (2002) we use data directly from the statement of cash flows. The first definition of accruals is Operating accruals. This is calculated as the difference between earnings and cash flows from operations (CFO):

Net income is earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item #123) and CFO is cash from operating activities (Compustat item #308), as reported on the statement of cash flows. Footnote 6

Sloan (1996) calculates current accruals using the balance sheet (we term this measure BS current accruals). Sloan subtracts BS current accruals from operating earnings to derive cash flows. Sloan (1996) measure is based on current assets and liabilities. Therefore, his measure will reflect special items related to write-downs of current assets (e.g., inventory or receivables) and creation of current liabilities relating to restructurings. However, unlike our operating accrual measure, BS current accruals will not include special items related to the write-down of long-term assets or creation of long-term restructuring liabilities. Therefore, our definition of operating accruals will include more special item accrual adjustments.

The second definition is Total accruals, calculated as the difference between earnings less free cash flows (FCF):

We define FCF as equal to CFO + CFI. CFI is cash flows from investing activities (Compustat Item #311), as reported on the statement of cash flows. FCF will reflect the impact of cash spent on property, plant and equipment, acquisition and other investments that have been capitalized as assets on the balance sheet. It will also reflect cash received for sale of divested assets and other investments. Therefore, FCF better matches the flows in earnings because earnings includes capital charges such as depreciation and amortization charges that are ignored in CFO. Footnote 7 Total accruals is similar to the measure used in Richardson et al. (2005) and Fairfield, Whisenant, and Yohn (2003a) except that their measures are calculated directly from balance sheet accounts and would also include assets and liabilities obtained through mergers and acquisitions (we term their measure BS total accruals).

Stock returns are measured using compounded buy-hold size-adjusted returns, inclusive of dividends and other distributions. Returns are calculated for a 12-month period beginning 4 months after the end of the fiscal year. The size-adjusted return is calculated by deducting the value-weighted average return for firms in the same size-matched decile, where size is measured as the market value at the beginning of the return cumulation period. For delisted firms during our return window, the remaining return is calculated by first applying CRSP’s delisting return and then reinvesting any remaining proceeds in the appropriate size-matched portfolio.

For tests reported later in the paper we use I/B/E/S data. We use the median long-term earnings growth forecast outstanding in the fourth month after fiscal year end. We calculate the growth forecast error as realized growth minus the growth forecast. Realized growth is the average future annualized EPS growth determined from I/B/E/S. We also obtain the number of analysts following the firm in the fourth month after the fiscal year end.

We use data on 13F filers obtained from the CDA/Spectrum 13F institutional transaction quarterly data. 13F filings are required on a quarterly basis from all institutional investors with more than $100 million of securities under their discretion. We report the average of the quarterly percentage changes in the number of institutional holders for each firm over the fiscal year. Footnote 8

We trim the 1% tails of all our financial statement variables except special items in order to remove extreme outliers. Our final sample with non-missing financial statement data consists of 63,875 firm years.

3 Empirical results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 provides summary statistics of the financial variables used in our analysis. Panel A reports descriptive statistics. All variables are scaled by average assets. Median earnings is 0.028, while median cash from operations is 0.065. This difference reflects the fact that due to depreciation, operating accruals are negative (−0.051). Special items have a median value of 0.000; however, the mean is −0.018, suggesting that the distribution of special items is highly skewed. Investing cash flows are consistently negative for most areas of the distribution (median −0.066). FCF are negative (median −0.012) suggesting that on average, firms are raising financing (median cash from financing, CFF, is 0.003).

Panel B provides both Spearman and Pearson correlations. For ease of exposition, we discuss the Spearman correlations. Consistent with prior research, we document a positive correlation between earnings and operating accruals (0.393) and total accruals (0.462). We also document a positive correlation between earnings and CFO (0.647) and FCF (0.368). We find a negative relation between earnings and investing cash flows (−0.250) and financing cash flows (−0.244). Cash from financing is negatively related to CFO (−0.435), CFI (−0.417), and FCF (−0.788), consistent with firms raising capital when cash flows are negative and paying dividends/extinguishing debt when FCF are positive. Consistent with matching, we find that total accruals are negatively related to FCF (−0.524), and operating accruals are negatively related to CFO (−0.306).

We predict that special items will be positively related to accruals and earnings because most special items are the result of writing off assets or the creation of liabilities. We do not expect strong correlations between special items and cash flows. Consistent with this expectation, special items are positively correlated with operating accruals (0.298), total accruals (0.202) and earnings (0.320), while the correlation between special items and our measures of cash flows are all less than 11% (CFO = 0.110, CFI = −0.007, CFF = −0.060, and FCF = 0.095).

In Appendix A, we investigate this issue further by randomly selecting 20 firms with large negative accruals that also had special items. We find that in almost all cases the special items are accrual adjustments (e.g., impairment charges) that did not affect cash flows. In addition, since 2001 Compustat has classified types of special items. Footnote 9 For a sample of 1117 firm-years that belong to the lowest decile of operating accruals and have negative special items greater than 5% of assets during 2001–2004, we investigate the accrual component as a percentage of special items. We find that, for this sample, on average, 81.89% of special items are accruals (median = 100%). If we make the conservative assumption that all restructuring costs are cash, then this average drops to 72.03 (median = 96.38%).

In Panel C we compare the correlations between our cash flow based measures and the balance sheet based measures described in Section 3. The correlation between operating accruals and BS Current Accruals is 0.75 and between Total Accruals and BS total accruals is 0.76. We replicate all of our results reported later in the paper using the balance sheet measures of accruals and get stronger results using BS total accruals and similar results using BS Current Accruals.

Finally, we report the correlations between non-cash funds reported in the statement of cash flows and special items. Our objective is to obtain a measure that reflects balance sheet adjustments and we use as our proxy, special items. However, special items contain error because some special items could be adjustments to cash flows (e.g., severance pay for terminated employees). The low correlation between special items and cash flows reported in Panel B suggests that this is not too important a concern. Non-cash funds should include special items but also includes other adjustments that could add error such as minority interest, amortization of various intangibles, etc. The Spearman and Pearson correlations between these measures are 0.46 and 0.73, respectively. We replicate our results using non-cash funds and the tenor of the results is similar. Footnote 10

3.2 The persistence of cash flows and earnings with the magnitude of accruals and the role of special items

We conjecture that the persistence of earnings relative to that of cash flows will vary with the magnitude of accruals. To investigate this issue we rank observations into deciles based on each measure of accruals. Decile 1 contains firms with extreme negative accruals and decile 10 has firms with extreme positive accruals. We then perform the following regressions for each decile:

Regression (1a) examines whether the persistence of earnings is lower for extreme accrual deciles. Regression (1b) examines whether the persistence of cash flows likewise is lower for extreme accrual deciles. Dechow and Dichev (2002) point out that extreme accruals reflect a more uncertain and volatile business environment. Therefore, the usefulness of cash flows as an alternative performance or valuation metric could also vary with accruals. Regression (1c) provides evidence on how well cash flows predict future earnings across deciles. This regression addresses the question of whether earnings or cash flows better predicts future earnings. Footnote 11

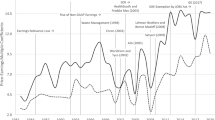

Figure 1a reports the estimated persistence parameter of earnings and cash flows (where cash flows are defined as cash from operations) based on the magnitude of operating accruals. Figure 1b is similar except that firms are ranked on total accruals and free cash flows is the measure of cash flows. For ease of exposition, we discuss only the results for operating accruals. We make four observations from Fig. 1a.

-

1.

On average, earnings are more persistent than cash flows. This is consistent with Dechow (1994) who argues that revenue recognition rules and the matching principle improve earnings as a measure of performance relative to cash flows.

-

2.

The persistence of earnings displays a concave relation with accruals. When accruals are small in absolute magnitude, earnings have high persistence close to 1.00. Large accruals of either sign reduce the persistence of earnings. This is consistent with the findings reported in Sloan (1996).

-

3.

The persistence of cash flows also reflects a concave pattern. This suggests that underlying economics reflected in accruals also affect the persistence of cash flows. For example, firms in declining business are likely to be selling stores, paying off leases, and clearing inventory; this will induce temporary components in cash flows. Likewise high accrual firms are likely to have negative cash flow expenditures that result in positive future cash flows (e.g., investments in PPE or inventory) and this can also induce transitory components in cash flows. Thus the low earnings persistence for firms with extreme accruals is not entirely due to earnings manipulation or reliability issues in measuring accruals.

-

4.

A comparison of the persistence of earnings and cash flows reveals that the incremental benefits of accruals are highest for high accrual firms and lowest for low accrual firms. These results are consistent with P1a and P2a. For high accrual firms, earnings persistence is 0.88 versus CFO persistence of 0.64. For low accrual firms, earnings persistence is 0.50 and is lower than CFO’s persistence of 0.61. Footnote 12 The results for regression 1c (cash flows ability to predict future earnings) yield a similar conclusion. In high accrual firms, cash flows are less useful than earnings for predicting future earnings, but in low accrual firms cash flows are more useful.

The role of earnings and cash flow for predicting future firm performance by accruals. (a) Earnings and CFO persistence by operating accruals. (b) Earnings and FCF persistence by total accruals. The sample consists of 61,989 firm-years from 1988 to 2002. Firms-year observations are ranked annually and assigned in ascending order to decile portfolios based on operating accruals or total accruals. Decile 1 consists of firms with the most negative accruals. Decile 10 consists of firms with the most positive accruals. Earnings is earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123). Operating accruals is defined as earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123) minus cash flow from operations (CFO, Compustat item 308). Total accruals is defined as earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123) minus free cash flow. Free cash flow is defined as cash flow from operations (Compustat item 308) plus cash flow from investing (Compustat item 311). The above variables are deflated by average total assets. The coefficient estimates of earnings and cash flows are estimated from the following regressions: Earnings t+1=α t +βEarnings t +ɛ t ; CFO t+1=α t +δCFO t +ɛ t ; Earnings t+1=α t +γCFO t +ɛ t ; Earnings t+1=α t +δFCF t +ɛ t ; FCF t+1=α t +γFCF t +ɛ t

Figure 2 investigates prediction P1b and P2b. The figure reports the correlation between cash flows and accruals for each decile. The results show that high accrual firms have the strongest negative correlation of −0.45. As accruals decrease, the correlation becomes less negative and is positive in deciles 1 and 2, with decile 1 reporting a correlation of 0.29 between cash flows and accruals. The results in Fig. 2 support prediction P1b and P2b and corroborate findings reported in Fig. 1.

The correlation between cash flow and accruals across accruals deciles. (a) Spearman correlation between operating accruals and CFO by operating accruals. (b) Spearman correlation between total accruals and FCF by total accruals. The sample consists of 63,875 firm-years from 1988 to 2002. Firms-year observations are ranked annually and assigned in ascending order to decile portfolios based on operating accruals and total accruals. Decile 1 consists of firms with the most negative accruals. Decile 10 consists of firms with the most positive accruals. Earnings is earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123). Operating accruals is defined as earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123) minus cash flow from operations (CFO, Compustat item 308). Total accruals is defined as earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123) minus FCF. FCF is defined as cash flow from operations (Compustat item 308) plus cash flow from investing (Compustat item 311). The above variables are deflated by average total assets

Figure 3 provides further intuition on the relation between accruals, cash flows, and earnings persistence. Figure 3 reports the average level of earnings and cash flows for each decile of accruals. The most negative cash flows are reported for high accrual firms (decile 10). However, accrual adjustments “match” these negative cash flows so that earnings are positive. Low accrual firms (decile 1) also have negative cash flows (though much smaller in magnitude). However, in this decile, accruals accentuate the negative cash flows and the result is that earnings are far more negative than cash flows. This is consistent with firms “fair-valuing” assets (recording special items) when cash flows are lower than expected and is broadly consistent with the concept of conservative accounting (e.g., Watts, 2003; Ball & Shivakumar, 2005).

The average level of earnings and cash flow across accrual deciles. (a) Means of Earnings and CFO by operating accruals. (b) Means of Earnings and FCF by total accruals. The sample consists of 63,875 firm-years from 1988 to 2002. Firms-year observations are ranked annually and assigned in ascending order to decile portfolios based on operating accruals and total accruals. Decile 1 consists of firms with the most negative accruals. Decile 10 consists of firms with the most positive accruals. Earnings is earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123). Operating accruals is defined as earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123) minus cash flow from operations (CFO, Compustat item 308). Total accruals is defined as earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123) minus FCF. FCF is defined as cash flow from operations (Compustat item 308) plus cash flow from investing (Compustat item 311). The above variables are deflated by average total assets

Figure 4 plots the proportion of firms reporting large negative special items based on ranks of accruals. Large negative special items are defined either as special items as a percent of assets greater than 1%, 2% or 5%. The results indicate that the proportion of firms reporting special items is largest in deciles 1 and 2. Approximately 55% of firms in decile 1 report special items that are greater than 2% of average total assets. The results in Fig. 4 suggest that the low persistence of earnings in decile 1 and the positive correlation between cash flows and accruals is likely to be due to the high frequency of special items.Footnote 13

Frequency of negative special items across accrual deciles (a) Based on ranks of operating accruals. (b) Based on ranks of total accruals. The sample consists of 63,875 firm-years from 1988 to 2002. Firms-year observations are ranked annually and assigned in ascending order to decile portfolios based on operating accruals and total accruals. Decile 1 consists of firms with the most negative accruals. Decile 10 consists of firms with the most positive accruals. Earnings is earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123). Operating accruals is defined as earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123) minus cash flow from operations (CFO, Compustat item 308). Total accruals is defined as earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123) minus FCF. FCF is defined as cash flow from operations (Compustat item 308) plus cash flow from investing (Compustat item 311). The above variables are deflated by average total assets

We next investigate whether special items are important for explaining why the accrual component of earnings is less persistent than the cash flow component. Table 2 provides the following regressions:

Regression (1a) and (2) are provided for comparative purposes, while regression (3) and (4) analyze the role of special items. There are two panels in Table 2. Panel A provides the specification using operating accruals. Panel B provides the specification using total accruals. The results in Panel A indicate that the persistence parameter on earnings is 0.696. Decomposing earnings into cash flows and accruals indicates that the cash flow component of earnings is more persistent than the accrual component of earnings (0.828 vs. 0.465). This is consistent with the findings in Sloan (1996). A decomposition of accruals into the special item component and the pre-special item component indicates that the special item component of accruals is less persistent than other accrual components (0.604 vs. 0.156). Thus, firms with special items appear to be an important driver of the lower coefficient on accruals relative to cash flows. Note that the coefficient on cash flows hardly changes (0.828 vs. 0.863) suggesting that most special item adjustments affect accruals and not cash flows. The fourth regression is equivalent to the third regression. We provide this specification purely to clarify that deducting special items from accruals has no effect on the magnitude of δ1 or δ2. These results confirm that special items accrual adjustments are important for explaining the lower persistence of the accrual component.

We next examine the conjecture that firms with low accruals and special items are likely to have even less persistent earnings. To test this we run the following regression:

where Low accruals is an indicator equal to one for firms in the bottom decile of accruals, and SI is an indicator equal to one when the magnitude of negative special items is greater than 2% of assets. Note that after controlling for the lowest decile of accruals, the coefficient on earnings increases from 0.696 in regression (1a) to 0.886. The negative coefficients on the interaction terms indicate that persistence of earnings is lower for firms with low accruals but without special items (0.886−0.231) and even lower for firms with low accruals and special items (0.886−0.231−0.226). This is consistent with Prediction P3.

Finally, we report the following regression:

This regression investigates whether the higher coefficient on earnings of 0.886 reported in regression (5) is due to an improvement in the persistence of the accrual component, cash flow component, or a combination of both. A comparison with regression (2) indicates that the cash flow component increases from 0.828 to 0.913, while the accrual component increases from 0.465 to 0.683. Thus, the improvement in the persistence of earnings primarily comes from the improvement in the persistence of the accrual component. Similar inferences are drawn from the results reported in Panel B using total accruals as our accrual metric. Footnote 14

3.3 Special items, accruals and future returns

We next investigate whether investors understand the implications of special items in low accrual firms. Table 3 ranks observations into deciles based on the magnitude of accruals. We report the percentage of observations that have special items and the average level of accruals for firms with and without special items. The mean level of operating accruals is lower for firms with special items in decile 1 (−0.279 vs. −0.358). However, additional tests reported later in the tables (see Table 8) suggest that our return results are not just due to a finer partitioning of accruals. The average size of reported negative special items is also larger in decile 1 relative to other deciles, suggesting that firms in decile 1 are likely to be taking radical steps in downsizing their operations. The next column reports the returns to the accrual anomaly for our sample. Operating accruals generate a theoretical hedge return of 13.3%. Total accruals generate a theoretical hedge return of 20.9%. These results are consistent with the findings of prior research (Sloan, 1996; Richardson et al., 2004). The next two columns report the future returns to special item versus the other firms in each decile. The return to special item firms in decile 1 is 11.7% whereas for other firms the return is only 1.4%. A similar finding holds in decile 2–7. Footnote 15

It is worth noting that the context of the special item appears to be important. The difference in returns is highest for low accrual firms, but declines and even reverses for high accrual firms (in deciles 8, 9, and 10). High accrual firms tend to have lower future earnings, while special items firms tend to have higher future earnings. Thus, for the small proportion of firms reporting high accruals and special items the two effects on future earnings could be offsetting. High accrual firms with special items could also be firms that report “pro forma” earnings. Doyle et al. (2003) provide evidence that these firms tend to under-perform. Our results also help explain why Burgstahler et al. (2002) find only weak evidence that special items predict future earnings reversals and stock returns. Our evidence suggests that when special items are accompanied by negative accruals (suggesting that the special item most likely relates to accruals and not to cash flows) they appear to be more useful for predicting future positive stock returns.

Panel B reports the findings for total accruals. The results using this measure are similar to Panel A. The high returns to the low accrual firms appear to be primarily driven by firms reporting large negative special items.

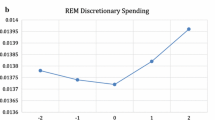

Figure 5 examines the robustness of this result across years. We split the bottom decile of accruals into those firms reporting special items and those that do not. In 11 of the 15 years for operating accruals, and 13 of the 15 years for total accruals, the special item firms outperform other low accrual firms. This suggests that our results are not driven by a few unusual years.

Difference in size-adjusted returns (special items firms—others) for low accrual firms by year. (a) Based on ranks of operating accruals and special items. (b) Based on ranks of total accruals and special items. The sample consists of firm-years that belong to the bottom decile of accruals from 1988 to 2002. Firm-year observations are ranked annually and assigned in ascending order to decile portfolios based on Operating accruals and Total accruals. Operating accruals is defined as earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123) minus cash flow from operations (CFO, Compustat item 308). Total accruals is defined as earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat item 123) minus free cash flow. Free cash flow is defined as cash flow from operations (Compustat item 308) plus cash flow from investing (Compustat item 311). The above variables are deflated by average total assets. Special item firms refer to those firm-years having negative special items is greater than or equal to 2% of average total assets. Annual returns are calculated from the start of the fourth month subsequent to the fiscal year-end. The size-adjusted return is calculated by deducting the value-weighted average return for firms in the same size-matched decile, where size is measured as the market value at the beginning of the return cumulation period. For delisted firms during our return window, the remaining return is calculated by first applying CRSP’s delisting return and then reinvesting any remaining proceeds in the appropriate size-matched portfolio

Table 4 provides more formal tests of investor perceptions using the Mishkin (1983) tests (see Sloan, 1996 for more details). Panel A reports results for regression (3) in Table 2 where we decompose earnings into cash from operations, pre-special item operating accruals, and special items. The results indicate that investors underweigh the cash flow component (0.863 vs. 0.710), overweigh the accrual component (0.604 vs. 1.002) and overweigh special items (0.156 vs. 0.641). Investors appear to recognize that special items are less persistent than other components of accruals, but they overweigh their persistence.Footnote 16

Panel B provides the results for regression (5). This regression includes interactive indicator variables for whether the observation is in decile 1 and whether the firm reports a special item. The results suggest that investors overweigh current earnings for firms in deciles 2–9 (0.886 vs. 1.007). The coefficient on (Earnings × Low OPACC) is −0.231 in the earnings regression and −0.622 in the returns regression. This indicates that low accrual firms without special items have earnings persistence of 0.655 (0.886−0.231), whereas the implied persistence from the returns regression is 0.385 (1.007−0.622), suggesting that investors expect greater earnings reversals than are actually realized. Finally, the coefficient on (Earnings × Low OPACC × SI) is −0.226 in the earnings regression and 0.155 (weakly significant at 11% level) in the returns regression. This indicates that low accrual firms with special items have earnings persistence of 0.429 (0.886−0.231−0.226), whereas the implied persistence from the returns regression is 0.540 (1.007−0.622+0.155), suggesting investors assume special item-low accrual firms have relatively more persistent earnings than they actually do. Similar findings are reported for total accruals in Panels C and D.

3.4 Why do investors undervalue low accrual firms with special items?

Reporting a special item is not a random event and so special item-low accrual firms could differ in fundamental ways from other low accrual firms. In addition, managers have incentives to highlight the transitory nature of special items, so why would investors overweigh them? The objective of this section is to provide further insights into why special item-low accrual firms appear to be undervalued by investors.

3.4.1 Poor past performance

Table 5 Panel A, B provides various measures of growth across accrual deciles. The relation between asset growth and accruals (particularly for total accruals) is mechanical since accruals are defined in terms of changes in net assets. It is reported here to show how asset-base growth varies systematically with accruals. Sales growth is −1.1% for low accrual firms and 21% for high accrual firms; past 3-year’s growth in sales shows an even larger spread. The change in earnings scaled by sales also varies systematically across deciles. Low accrual firms report a much higher percentage of losses than other accrual deciles. These results are consistent with firm performance varying as a function of accruals.

Table 5 Panel C compares special item-low accrual firms to other low accrual firms. The results indicate that special item firms have significantly lower asset growth, lower past sales growth (measured either over 1–3 years), more negative changes in earnings, and a greater percentage of firms reporting losses. Thus special items firms have performed very poorly during the fiscal year in which they report the special item.

3.4.2 Market perception and investor recognition

Table 6 investigates how market participants respond to firm performance as it varies with accruals. As expected, investor response is correlated with firm performance and is positively correlated with accruals. Firms reporting low accruals have earned annual negative size-adjusted returns of −17%, while firms with high accruals have returns of 11%. As documented by Lehavy and Sloan (2004), analysts increase coverage of high accrual firms (21.7%) and drop coverage of low accrual firms (−3.6%). Institution investors behave in a similar manner. The average change in institutional holding is highest for high accrual firms and lowest for low accrual firms.

We also report the average book-to-market ratio (measured at fiscal year end) for each decile of accruals. High book-to-market ratios suggest (among other things) that market participants have low expectations of future growth (e.g., Lakonishok et al., 1994; Desai, Rajgopal, & Venkatachalam, 2004). Book-to-market ratios, however, exhibit a concave relation with accruals, being lowest for both high and low accruals. The large write-offs included in the numerator for low accrual firms, and the high growth expectations built into market prices for high accrual firms, are likely to explain this relation. Finally, we report analysts’ long-term growth forecast errors measured 4 months after the fiscal year-end for the subset of firms that have analyst coverage. Consistent with Bradshaw et al. (2001) who analyze short-term forecasts, we document a negative relation between growth forecast errors and accruals. Analysts are most pessimistic about the future growth prospects of low accrual firms and this may be why analysts drop coverage of low accrual firms.

Table 5 Panel C indicates that special item-low accrual firms performed significantly worse than other low accrual firms. In Table 6B we investigate how the market responds to this poor performance. Special item firms have contemporaneous returns of −25.6% versus −7.3% for other low accrual firms. This is consistent with the findings in Francis, Hanna, and Vincent (1996). Analysts drop coverage of the special item firms (−9.5%), while other low accrual firms experience an increase in coverage (7.09%). Likewise, the decline in institutional holding is entirely due to special item firms (−0.024% for special item firms versus 0.041% for other low accrual firms). These results suggest that special item firms suffer significant declines in investor recognition. However, analysts that choose to continue following special item firms are no more pessimistic than analysts that follow other low accrual firms. Book-to-market is the incorrect sign, most likely due to the effect of special items on the numerator.

3.4.3 Fundamental risk: bankruptcy risk and information uncertainty

We next investigate whether bankruptcy risk varies across accrual deciles and whether the information environments differ. We measure bankruptcy risk using the model developed by Shumway (2001):

\(\alpha =-13.303-1.982{\ast} NI+3.593{\ast} TL-0.467{\ast} \hbox{SIZE}-1.809{\ast} \hbox{RET}+5.791{\ast} \hbox{SIGMA}\).

The variables included in the model are: net income scaled by total assets (NI), total liabilities scaled by total assets (TL), relative size measured as the logarithm of each firm’s size relative to the total size of the NYSE and AMEX market (SIZE), past market-adjusted return (RET), and the idiosyncratic standard deviation of each firm’s stock returns (SIGMA). SIGMA is calculated by first regressing each stock’s monthly returns in t−1 on the value-weighted NYSE/AMEX index return during the same time period. SIGMA is the standard deviation of the residual of the regression. We use the parameter estimates provided in Shumway (2001) to estimate the probability of bankruptcy. We also provide the percent of firms delisted for performance related reasons as an ex post measure of bankruptcy risk.

Table 7A reports that the Shumway score and the percent of firms delisted are highest for low accrual firms, suggesting that bankruptcy concerns are important in these firms. Panel A also reports share turnover calculated as the number of shares traded during the day divided by shares outstanding. We calculate this measure each day during the fiscal year and report the average for each firm. We find that share turnover is convex across deciles being highest for decile 1 and 10. This is consistent with a lack of consensus regarding the stock price for both high and low accrual firms.

Table 7B compares special item-low accrual firms to other low accrual firms. Special item firms have a greater frequency of delisting over the next year and higher share turnover. They also have a higher probability of bankruptcy using the Shumway score. Given that special item firms have very poor earnings, poor stock price performance, high share turnover (that is likely to be correlated with SIGMA), it is not surprising that they also have high Shumway scores.

Table 7A also reports analyst coverage (equal to one if the firm is covered by an analyst, zero otherwise). Only 37% of the low accrual firms are followed by analysts and for these firms, the median number of analysts following the firm is 3. For all remaining deciles, the coverage is at least 50% and the median number of analysts following the firm ranges between 4 and 6. This is consistent with low accrual firms having a poorer information environment. However, Table 7B indicates that the percentage of firms followed by analysts is higher for special item firms, while the number of analysts following special item firms is not significantly different. Special item firms are larger in size (market value of $301.8 million vs. $264.1 million for low accrual firms with no special items) and since analysts following is correlated with size this may explain why coverage is higher for these firms.

3.4.4 Special item and future returns: robustness tests

The analysis in Tables 6 and 7 suggests that special item-low accrual firms differ in important ways from other low accrual firms. Table 8 investigates whether these variables subsume special item’s ability to predict future returns. We include the level of accruals in the regression since Table 3 indicates that special item firms have lower accruals and we do not want special items to purely partition firms on the magnitude of accruals.

The results indicate that special items continue to explain future returns after controlling for other potential determinants of future returns. Note that book-to-market now has the correct sign suggesting that after controlling for special items, value stock earn higher returns. Changes in institutional ownership continue to be important for explaining future returns. Analyst coverage is also significant suggesting that firms followed by analysts perform better in the future. This is consistent with findings by Barber, Lehavy, McNichols, and Trueman (2001). In the total accruals regression share turnover is negative and significant suggesting that low accrual stock with low turnover earn higher future returns. This is consistent with Lee and Swaminathan (2000) who find that value stock with low turnover are more likely to perform well in the future.

Table 9 provides two robustness tests of our results. The results in Table 7 suggest that bankruptcy risk is high for special item-low accrual firms. In unreported results we find that a simple screen of avoiding firms with share prices less than $1 or market values less than $50 million significantly reduces the probability of bankruptcy for special item low accrual firms. Footnote 17 Table 9 examines whether special items are useful for predicting returns after implementing these simple screens. The results indicate that special items remain significant. In addition, in unreported tests we also exclude the Shumway score from our regressions since data requirements for this variable reduce the sample size. The tenor of the results does not change.

Finally, Kraft et al. (2005) suggest that the accrual anomaly is driven by “outlier” returns. Our results continue to hold after trimming the future size-adjusted returns at 1% tails (in the operating accrual regression the coefficient estimate on special items is 0.054; t statistic = 2.16). Footnote 18

To summarize, this section investigates why special items-low accrual firms appear to be mispriced. We show that special item-low accrual firms have performed very poorly in the year that the special item is reported. They earn large negative stock returns, have high share turnover, are dropped by analysts, and sold by institutional investors. Thus although investors appear to understand that special items are more transitory than other accrual components, they still give them too much weight. Market participants appear to place too low a probability that special item-low accrual firms will recover.

4 Conclusion

We point out that applicable accounting accrual rules differ for high and low accrual firms. High accruals are likely to be the outcome of accounting rules with an income statement perspective, while low accruals are likely to be the outcome of accounting rules with a balance sheet perspective. We predict that this difference in perspectives leads to difference in the usefulness of earnings for predicting future performance for high and low accrual firms. Consistent with this prediction we show that: (i) high accrual firms have high earnings persistence relative to that of cash flows, and cash flows and accruals are negatively correlated; (ii) low accrual firms have low earnings persistence relative to that of cash flows, and cash flows and accruals are positively correlated; (iii) special items play an important role in explaining the lower persistence of earnings in low accrual firms. We also point out that: (iv) the persistence of both cash flows and earnings varies with the magnitude of accruals, suggesting that firms with extreme accruals are operating in more volatile business environments.

The remainder of our paper focuses on low accrual firms and examines the implications of special items for the accrual anomaly documented by Sloan (1996). Sloan shows that the accrual component of earnings is more transitory than the cash flow component. We point out that earnings persistence is affected both by the magnitude and sign of the accruals. Specifically, low accrual firms will have more transitory earnings than high accrual firms because of balance sheet adjustments relating to special items. We document that low accrual firms with special items have higher future stock returns than other low accrual firms. This is consistent with investors misunderstanding the transitory nature of special items.

Our results provide an alternative interpretation to the conclusions drawn in concurrent research by Kraft et al. (2005). Kraft et al. investigate the annual reports of 29 “outlier” (extreme positive) returns in the low accrual decile. They report that most of these firms have large write-offs. They conclude that this evidence supports their outlier story for the accrual anomaly because investors should not misprice special items since management have incentives to highlight them. In contrast, our results suggest that the mispricing of low accrual firms with special items is a more general phenomenon and is not limited to positive “outlier” return firms.

We provide further tests to better understand why investors undervalue special item-low accrual firms. We find that special item-low accrual firms have poor past sales growth, are reporting losses, have poor past stock price performance, have high bankruptcy risk, and share turnover is unusually high. We also find that analysts have dropped coverage and institutional investors have reduced their holdings in these firms. Taken together, these results suggest that there is high uncertainty and pessimism about the prospects of these firms with the consequence being a decline in investor recognition. The reporting of special items by management appears to mark the end of this negative momentum, and on average, these firms turn themselves around at higher rates than expected by investors.

Our research raises questions for future research. For example, do different types of special items have different implications for earnings persistence and future returns? The results of Elliott and Hanna (1996) and Francis et al. (1996) suggest that they may. Are implications different for cash special items (e.g., McVay, 2006)? Can an analysis in the spirit of Piotroski (2000) and Mohanram (2005) distinguish special item-low accrual firms that delist from those that turn themselves around? What actions do managers take that reverse the market’s perceptions? More generally, does our finding that the correlation structure between cash flows and accruals varies with the level of accruals have implications for research modeling accruals? Finally, we focus on low accruals and implications of the balance sheet perspective; future research could examine high accrual firms and implications of the income statement perspective.

Notes

Merton (1987) argues that investors only use securities that they know about in constructing their optimal portfolios. Therefore, firms with low investor recognition will earn higher returns than firms with high investor recognition.

If bankruptcy risk is a priced source of risk, firms with higher bankruptcy risk should earn higher future returns to compensate for this risk. However, Dichev (1998) provides evidence that firms with high bankruptcy risk earn lower future returns (inconsistent with bankruptcy risk being a priced source of risk). His results suggest that investors do not require a premium for holding stock with high bankruptcy risk. Alternatively, Kahn (2005) provides descriptive evidence that low accrual firms are more financially distressed. However, Kahn provides no formal evidence that bankruptcy risk is a priced source of risk.

The sample is not restricted to only NYSE/AMEX firms; therefore, it does not have the exchange listing bias suggested by Kraft, Leone, and Wasley (2005).

Our results are similar when we subtract the cash portion of discontinued operations and extraordinary items (Compustat item #124) from cash from operations to calculate operating accruals according to Hribar and Collins (2002). The Spearman correlation between the measures is 0.99.

Our definition of FCF includes some financing charges such as interest paid and received and certain effects related to the tax effects of stock options (e.g., Hanlon & Shevlin, 2002) and changes in some financial assets such as marketable securities.

We thank Reuvan Lehavy and Richard Sloan for providing us with their data on quarterly changes in institutional holdings.

Compustat has the following classifications for special items: Acquisition/merger pretax (Data item #360); Gain/loss pretax (Data item #364); Impairments of goodwill pretax (Data item #368); settlement (litigation/insurance) Pretax (Data item #372); Restructuring costs pretax (Data item #376); Write-down pretax (Data item #380); Other special items pretax (Data item #384). We calculate the accrual component of special items as the sum of gain/loss, impairments of goodwill, restructuring costs, and write-downs.

We attempted to reconcile the non-cash fund number reported by Compustat to the Statement of Cash Flows for the 20 firms identified in Appendix. We found this number more difficult to identify and reconcile to underlying accruals than the special item number.

When earnings and cash flows at t+1 are missing because the firm has been delisted for performance related reasons we make the following adjustment: we assume that firm has liquidated and so investors lose all their invested capital (i.e., the book value of equity). Therefore, we substitute the negative of the book value of equity as the future performance metric. When the book value is negative, we substitute zero as the future performance metric. We do this adjustment to avoid survivorship bias upwardly biasing our measures of persistence. In addition, we include delisted firms in our stock returns tests so the adjustment makes results comparable across tables.

When we make no adjustments for missing earnings and cash flows at t+1, earnings persistence is 0.60 and is still lower than CFO’s persistence of 0.68.

We also investigated positive special items; however, there is little variation across accrual deciles. For our entire sample, 3.8% of firms report positive special items greater than 2% of assets. Nine percent of high accrual firms have positive special items versus 3% for low accrual firms.

One issue of concern is whether to use earnings on a before or after-tax basis since special items and accruals are on a before-tax basis. Appendix A examines whether special items affected the tax expense/benefit reported by a random sample of low accrual firms. We find that in most cases the special items did not affect reported taxes since most of the firms were reporting losses and had a 100% deferred tax asset valuation allowance. In unreported tests, we also ran regressions using pretax income and adjusting cash flows for tax effects. The tenor of the results reported in Table 2 does not change.

Thomas and Zhang (2002) document that the negative relation between accruals and future abnormal returns is driven by inventory changes. We find that our results are not driven by inventory changes. In addition, Bradshaw et al. (2001) compare the hedge return for working capital accruals and operating accruals. Accrual adjustments excluded from working capital accruals but included in operating accruals include depreciation, amortization and special items. They find that the hedge returns based on working capital accruals is slightly higher than the returns based on operating accruals (a size-adjusted return of 11.1% vs. 10.3%). However, they do not investigate the specific role of special items.

Elliott and Hanna (1996) show that investors place less weight on write-offs than pre-special item earnings. However, they do not examine whether investors correctly weigh special items.

We delete observations where share price is less than $1 and find that the percentage of firms delisted declines from 18.39% to 13.03% for special item-low accrual firms and from 15.92% to 11.18% for other low accrual firms. The Shumway Score declines from 1.28% to 0.63% for special item firms and is no longer significantly different from other low accrual firms. We also remove stock with average daily dollar trading volume (share price × shares traded) and relative trading volume (dollar trading volume/market value) less than the bottom 10% of the sample. The tenor of the results does not change. The difference in size-adjusted returns for the two groups is unaffected by these adjustments.

References

Ball, R., & Shivakumar, L. (2005). The role of accruals in asymmetrically timely gain and loss recognition. Working paper, University of Chicago and London Business School.

Barber, B., Lehavy, R., McNichols, M., & Trueman, B. (2001). Can investors profit from the prophets? Security analyst recommendations and stock returns. Journal of Finance, 56(2), 531–563.

Beaver, W. (1968). The information content of annual earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting Research, 6, 67–92.

Bowen, R. M., Davis, A. K., & Matsumoto, D. A. (2005). “Emphasis on pro forma versus GAAP earnings in quarterly press releases: Determinants, SEC intervention, and market reactions. The Accounting Review (forthcoming).

Bradshaw, M. T., Richardson, S. A., & Sloan, R. G. (2001). Do analysts and auditors use information in accruals? Journal of Accounting Research, 39(1), 45–75.

Bradshaw, M. T., Richardson, S. A., & Sloan, R. G. (2003). Pump and dump: An empirical analysis of the relation between corporate financing activities and sell-side analyst research. Working paper, University of Michigan.

Bradshaw, M. T., & Sloan, R. G. (2002). GAAP versus the street: An empirical assessment of two alternative definitions of earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(1), 41–65.

Burgstahler, D., Jiambalvo, J., & Shevlin, T. (2002). Do stock prices fully reflect the implications of special items for future earnings? Journal of Accounting Research, 40(3), 585–612.

Chan, K., Chan, L. K. C., Jegadeesh, N., & Lakonishok, J. (2006). Earnings quality and stock returns. Journal of Business (forthcoming).

Core, J. E. (2005). Discussion of an analysis of the theories and explanations offered for the mis-pricing of accruals and accruals components. Working paper, University of Pennsylvania.

De Bondt, W. F. M., & Thaler, R. (1985). Does the stock market overreact? Journal of Finance, 40(3), 793–805.

Dechow, P. M., & Dichev, I. (2002). The quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation errors. The Accounting Review, 77(Supplement), 35–59.

Dechow, P. M. (1994). Accounting earnings and cash flows as measures of firm performance: The role of accounting accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 18(1), 3–42.

Desai, H., Rajgopal, S., & Venkatachalam, M. (2004). Value-glamour and accruals mispricng: One anomaly or two? The Accounting Review, 79(2), 355–385.

Dichev, I. D. (1998). Is the risk of bankruptcy a systematic risk? Journal of Finance, 53(3), 1131–1147.

Doyle, J. T., Lundholm, R. J., & Soliman, M. T. (2003). The predictive value of expenses excluded from pro forma earnings. Review of Accounting Studies, 8(2/3), 143–391.

Elliott, J. A., & Hanna, J. D. (1996). Repeated accounting write-offs and the information content of earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 34(Supplement), 135–155.

Fairfield, P. M., Sweeney, R. J., & Yohn, T. L. (1996). Accounting classification and the predictive content of earnings. The Accounting Review, 71(3), 337–355.

Fairfield, P. M., Whisenant J. S., & Yohn, T. L. (2003a). Accrued earnings and growth: Implications for future profitability and market mispricing. The Accounting Review, 78, 353–371.

Fairfield, P. M., Whisenant, J. S., & Yohn, T. L. (2003b). The differential persistence of accruals and cash flows for future operating income versus future profitability. Review of Accounting Studies, 8(2/3), 221–243.

Francis, J., Hanna, J. D., & Vincent, L. (1996). Causes and effects of discretionary asset write-offs. Journal of Accounting Research, 34(Supplement), 117–134.

Hanlon, M., & Shevlin, T. (2002). Accounting for tax benefits of employee stock options and implications for research. Accounting Horizons, 16, 1–16.

Hayn, C. (1995). The information content of losses. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 20(2), 125–153.

Hribar, P., & Collins, D. W. (2002). Errors in estimating accruals: Implications for empirical research. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 105–134.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky A. (1982). Intuitive prediction: Biases and corrective procedures. In Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (Eds.), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. London: Cambridge University Press.

Karpoff, J. M. (1986). A Theory of Trading Volume. Journal of Finance, 41(5), 1069–1087.

Khan, M. (2005). Are accruals really mispriced? Evidence from tests of an intertemporal capital asset pricing model. Working paper, MIT.

Kim O., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1991). Trading volume and price reactions to public announcements. Journal of Accounting Research, 29, 302–321.

Kraft, G. A., Leone, A. J., & Wasley, C. E. (2005). Research design issues and related inference problems underlying tests of the market pricing of accounting information. Working paper, London Business School.

Lakonishok, J., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1994). Contrarian investment, extrapolation, and risk. Journal of Finance, 49(5),1541–1578.

Lee, M. C. C., & Swaminathan, B. (2000). Price momentum and trading volume. Journal of Finance, 55(5), 2017–2069.

Lehavy, R., & Sloan, R. G. (2004). Investor recognition, accruals and stock returns. Working paper, University of Michigan.

Lougee, B. A., & Marquardt, C. A. (2004). Earnings informativeness and strategic disclosure: An empirical examination of “pro forma” earnings. The Accounting Review, 79(3), 769–795.

McVay, S. (2006). Earnings management using classification shifting: An examination of core earnings and special Items. The Accounting Review (forthcoming).

Mishkin, F. S. (1983). A rational expectations approach to macroeconometrics: Testing policy effectiveness and efficient markets models. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Mohanram, P. S. (2005). Separating winners from losers among low book-to-market stocks using financial statement analysis. Review of Accounting Studies, 10(2/3), 133–170.

Piotroski, J. (2000). Value investing: The use of historical financial statement information to separate winners from losers. Journal of Accounting Research, 38(Supplement), 1–41.

Richardson, S. A., Sloan, R. G., Soliman, M. T., & Tuna, A. I. (2005). Accrual reliability, earnings persistence and stock prices. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39, 437–485.

Schipper, K., & Vincent, L. (2003). Earnings quality. Accounting Horizons, 17(Supplement), 97–110.

Shumway, T. (2001). Forecasting bankruptcy more accurately: A simple hazard model. The Journal of Business, 74(1), 101–124.

Sloan, R. G. (1996). Do stock prices fully reflect information in accruals and cash flows about future earnings? The Accounting Review, 71(3), 289–315.

Teoh, S. H., & Zhang, Y. (2005). Loss firms, asset pricing controls, and accounting anomalies. Working paper, Ohio State University.

Thomas, J. K., & Zhang, H. (2002). Inventory changes and future returns. Review of Accounting Studies, 7(2–3), 163–187.

Watts, R. L. (2003). Conservatism in accounting part 1: Explanations and implications. Accounting Horizons, 17(3), 207–221.

Acknowledgements

This paper shared First Prize for Best Paper at the 2005 Review of Accounting Studies Conference. We have benefited from the comments of Patricia Fairfield, Charles Lee, Reuven Lehavy, James Ohlson, Stephen Penman, Scott Richardson, Richard Sloan, Irem Tuna, and an anonymous referee. We thank seminar participants at Barclays Global Investors, University of California, Berkeley, Carnegie Mellon Conference 2005, and the Review of Accounting Studies 2005 Conference, for their comments. We also thank the Harry H. Jones Endowment Fund for Research on Earnings Quality for financial support. This paper was previously titled “Earnings, Cash Flows, Persistence, and Growth.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dechow, P.M., Ge, W. The persistence of earnings and cash flows and the role of special items: Implications for the accrual anomaly. Rev Acc Stud 11, 253–296 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-006-9004-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-006-9004-1