Abstract

Purpose

To assess child and family engagement in the selection of patient-reported outcomes for clinical studies/clinical settings and development of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)/patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) across the pediatric literature.

Methods

Databases were reviewed: EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO. Articles published from December 2009 to September 2018 pertaining to the selection of outcomes or development of PROMs/PREMs for children or families were included. The International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) Spectrum of Public Participation was used to classify levels of engagement across each article; IAP2 plots engagement on a spectrum across five stages (from minimal to most engagement): Inform, Consult, Involve, Collaborate, and Empower.

Results

9019 non-duplicate articles were screened; 36 articles met inclusion criteria, seven studies focused on the selection of outcomes, and 29 studies pertained to PROM/PREM development. Twenty-three articles adhered to ‘Involve’ level of engagement. Four articles were categorized as ‘Collaborate,’ seven articles were classified as ‘Consult,’ and three articles were categorized as ‘Inform’.

Conclusion

Children and families were sparsely engaged as co-conductors or equal partners in the selection or development of PRO research; involvement remained on the mid-low end of the IAP2 Spectrum. Engaging with children and families as collaborators can improve the patient-centredness, rigour, and applicability of PROM/PREM research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health systems aimed at improving child health are facing a formidable challenge due to the rising prevalence of chronic conditions and complexity of patients with multiple comorbidities [1,2,3,4]. Patient-reported outcomes, and experiences, as well as their measures (PROMs/PREMs) are essential to health system improvement on the basis of child and family-oriented care [1, 2]. PROM measures capture the outcomes important to growing up well beyond biomedical indicators, such as mental health, mobility, and quality of life. Experience measures (PREMs) allow systems to capture the extent to which health care was perceived as family-centered, coordinated, and useful [5]. Both PROMs and PREMs are vitally important to quantifying the successes and failures of health interventions as well as resource planning and health policies [3, 6]. Yet PROMs/PREMs are rarely used in large scale studies, thereby rendering the majority of robust evidence on which health decisions are made, to have omitted child and family-important outcomes and experiences completely.

Omitting PROMs and PREMs from otherwise useful research studies (like clinical trials) excludes children and family voices from policy decisions but also serves as a barrier to shared decision-making [7,8,9,10,11]. For example, a family considering a high-stakes medical intervention such as epilepsy surgery, or medical device insertion, requires answers from health providers about the likelihood of good outcomes in order to make decisions [12,13,14]. In such cases, clinicians often have evidence on the outcomes of mortality and safety but not long-term functioning and quality of life [15, 16]. Thus, families and providers are forced to make important clinical decisions based on incomplete information. The lack of inclusion of PROMs/PREMs in the health services research thus also impacts routine clinical care [17, 18].

The degree to which PROMs and PREMs are used in health services and systems research is understood more than the relevance of that use to children and families from the first place. A PROM selected by researchers or clinicians might not be measuring the outcomes that are meaningful to the target population being studied [7, 19, 20]. For example, utility-based attributes relevant to general child population-health (walking, speaking) were incorrectly and unethically selected by researchers for decades to assess the quality of life of children with cerebral palsy who were never expected to walk or talk, but nonetheless had potential for functional mobility and communication [21,22,23]. Examples of the inclusion of children and families in the selection of outcomes and experiences that are relevant to them appear to be increasing in the literature [6,7,8, 18, 24, 25]. But it is unclear whether children and families are influential in the selection and development of the PROMs and PREMs that will be incorporated into the generation of knowledge needed for systems change.

In response to the need for appropriate inclusion of patients in the measurement process, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [26] and European Medicines Agency (EMA) [27] have created guidelines related specifically to the development and use of outcome measures [26, 27]. Both document the need for clear evidence that the content of outcome measures needed to correspond to important domains of concern in the target patient population and that the thresholds of meaningful change were influenced by patient input. These guidelines were one more assertion in the growing acceptance that inclusion of children and families in measurement selection and development is not merely ethical or value-based imperative but germane to rigor in health research.

Once the issue of meaningful child and family inclusion in the selection and development of PROMs and PREMs is recognized as an issue influencing rigor, a systematic understanding of the levels of child and family engagement that currently exist is needed. The International Association of Public Participation (IAP2) Spectrum of Public Participation is a framework that can classify various levels of patient participation [28]. It was chosen in lieu of other models of public participation due to its focus on categorizing levels of participation from low (inform) to high (empower) in place of the methods that could be used to engage patients [29,30,31] in the research selection and development process. This review aims to classify the current level of child or family engagement in the selection and development of PROMs/PREMs in child health research using the IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation [28].

Methods

Search strategy

We systematically reviewed three online databases: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and EMBASE. The search consisted of keywords linked by Boolean terms pertaining to ‘selection’ AND ‘outcomes’ AND ‘patient-reported outcome/experience measures’ AND ‘children/families’ AND ‘patient engagement.’ Search terms were expanded based on these key themes and synonymous terms were identified (Online Appendix A). A Queen’s University health sciences librarian worked with the primary reviewer to establish a comprehensive search strategy. Searches were limited to articles published in English. Articles were only considered if published between December 2009 and September 2018. December 2009 is in accordance with the publication of the FDA and EMA guidelines for PROMs. The review was interested to see at what level of engagement PROMs/PREMs were developed after the guidelines were created. Existing PROMs that were developed for the use in children were included in this review if they were created after the introduction to the FDA guidelines. Articles involving children, adolescents, or proxy reporting for this cohort were considered for inclusion. The review was conducted using the PRISMA guidelines [32].

Study selection

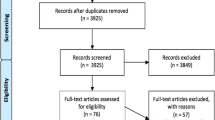

Covidence software was utilized throughout study selection [33]. Covidence is a platform used to streamline and optimize systematic review processes. Users of the software can import articles to be screened across the systematic review process. Covidence allows multiple authors to collaborate on the screening of abstracts against developed inclusion criteria. The primary reviewer screened article titles during phase one of study selection. Phase two of study selection involved screening of titles and abstracts; this was accomplished by the primary reviewer and two secondary reviewers. The primary reviewer screened 100% of titles and abstracts; two secondary reviewers initially screened a random selection of 25% of titles and abstracts. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved via consultation of a third uninvolved co-screener. See PRISMA flow diagram for synthesis of included articles (Fig. 1).

Inclusion criteria consisted of (i) articles pertaining to the selection of outcomes OR development of child and family-specific PROMs/PREMs AND (ii) pertaining to a health care setting. Both condition-specific and generic PROMs/PREMs were chosen to be included in the review as this study focused on engagement across the selection of outcomes and development of measures irrespective of conditions. Studies were either categorized as ‘Selection’ or ‘Development.’ Included studies that related to the identification or prioritization of meaningful outcomes/outcome sets were categorized as ‘Selection.’ Studies rooted in selection did not identify how outcomes should be measured. The focus of selection was to select and achieve a consensus of standardized outcomes which are deemed relevant to patient populations and should be utilized within measures. Furthermore, studies aiming to identify and select appropriate PROMs/PREMs for child and family populations were included in this category. Studies that included methods of developing measurement tools (PROMs/PREMs) to be used alongside children and families were categorized as ‘Development.’ Studies in the ‘Development’ category focused on the creation of these measures and the methods utilized across the development process.

This review focused on the use of PROs and PROMs used in pediatric populations; the development of instruments related to family function or caregiver health was not included. Articles were excluded if they were (i) not involving children or families, (ii) conference proceedings, or (iii) pertaining solely to the validity testing or translation of an existing measure. The IAP2 Spectrum and modified examples cannot appropriately be applied to studies which focus solely on validity testing or translation of existing measures. Conference proceedings were excluded as they do not provide enough information for engagement or selection to be accurately mapped on to the IAP2 Spectrum. The reference lists of included studies were searched manually by the primary reviewer for consideration of inclusion.

Data extraction

Defining engagement with the IAP2 public participation spectrum

Data extraction was carried out solely by the primary reviewer. This systematic review used a modified patient engagement spectrum published by the International Association of Public Participation (IAP2) to quantify levels of child and family engagement in the current literature (Fig. 2). The IAP2 is an international organization with the overarching mission of improving public participation across individuals, governments, and institutions [28]. The IAP2 regards ‘The Spectrum of Public Participation’ as a pillar of public engagement; it is an internationally used tool to assist in the selection of levels of involvement. The spectrum divides engagement into five distinct categories: Inform, Consult, Involve, Collaborate, and Empower. Modified examples were created for each level of engagement to be made applicable to the selection of outcomes and the development of measures.

Included articles were analyzed using the IAP2 Spectrum. A data extraction form was created based on the Cochrane Data Extraction and Assessment Template. Information obtained from each article included (i) article title, (ii) author, (iii) measurement name if applicable, (iv) study type, (v) selection of outcomes or development of measures, (vi) methods of engagement, (vii) stages of development/selection in which patients were engaged, and (viii) IAP2 level of engagement. Specific methods of engagement, such as the use of interviews or focus groups with participants were included in the data extraction form to ensure consistency throughout data analysis. The data extraction form allowed data to be coherently presented to the researchers and categorized according to the IAP2 Spectrum.

Studies included in the review were categorized according to IAP2 levels of engagement and a set of definitions and examples made specific to patient-reported outcome (PRO) selection and PROM/PREM development developed by researchers of this review (Online Appendix B). Engagement is categorized into five succinct categories, from the least to greatest level of participation (Inform, Consult, Involve, Collaborate, and Empower). The IAP2 Spectrum provides promise to the public in lay terms for each level of engagement to increase public understanding. The developed definitions range from no engagement (Inform) to children and families leading outcome selection or measure development (Empower). The remaining three categories range from limited involvement within one particular step of outcome selection or measure development (Consult), the iterative involvement of children and families across more than one step (Involve), and children and families having a clearly defined role as co-conductors of research (Collaborate).

Results

Included study characteristics

Thirty-six studies met inclusion criteria. Seven studies focused on the selection of outcomes and 29 studies pertained to PROM/PREM development. Table 1 provides a breakdown of each article in terms of first author, year, article context (i.e., select outcome or develop measure), IAP2 level of engagement, methods of engagement, and stage of engagement. Specific measure names are provided for articles that used them (see Online Appendix C). The most common IAP2 level of engagement across included studies was ‘Involve’ with 22 of the articles falling under this category, further defined by the iterative involvement of patient perspectives and concerns. Three studies were classified as ‘Inform’ with no engagement and seven studies were classified as ‘Consult’ with limited engagement. Four studies adhered to the criteria for ‘Collaborate’ in which children and families had clearly defined roles and were partners in the co-conduction of research. None of the included studies matched the criteria for ‘Empower’ in which children and/or families lead outcome selection or measurement development and act as final decision-makers. The categorization of studies is represented in Table 2. The systematic selection of articles is presented in a PRISMA diagram (Fig. 2). The most common reasons for the exclusion of included studies were as follows: (i) articles not pertaining to outcome selection or measure development and (ii) participants not involving the target cohort.

Methods of engagement

Methods of engagement varied across included studies. The following engagement methods were assessed for use across included articles: (i) interviews, (ii) focus groups, (iii) cognitive debriefing, (iv) concept elicitation methods, (v) co-recruitment, (vi) co-data collection, (vii) co-data analysis, (viii) co-dissemination, (ix) family driven outcome selection, (x) included in multiple steps and stages, and (xi) key decision-makers across crucial steps.

Participants were most frequently engaged via semi-structured interviews or focus groups. Five of seven articles pertaining to the selection of outcomes utilized these methods to elicit patient preferences for meaningful outcomes [6, 40, 45, 49, 56]. Nineteen of 29 articles with the aim of PROM/PREM development involved participants through focus groups or interviews throughout initial concept elicitation [34, 35, 37, 45,46,47,48, 51,52,53, 55, 57,58,59,60,61, 64, 65, 67]. Concept elicitation interviews were conducted to identify common themes and concepts which were deemed meaningful to children and families. The data collected through concept elicitation interviews or focus groups served as the basis for item generation to be used in developed measures. Ten articles which developed PROMs/PREMs did not engage participants through initial concept elicitation and the first draft of items were constructed based on expert consensus or through a review of existing literature [36, 38, 39, 41, 43, 44, 52, 62, 63, 68].

‘Informing’ children and families

Two of the studies in this category utilized a review of the literature followed by Delphi consensus rounds with experts to select and prioritize outcomes [42, 66]. One study relied solely on existing literature to develop a measure and piloted the measure with the target population, without further refinement [44]. The studies under ‘Inform’ did not directly reach out to children and/or families to obtain their preferences or perspectives relating to the selection of outcomes or development of measures.

‘Consulting’ children and families

Studies that only engaged children and/or families within one stage of selection or development with limited implementation were categorized as ‘Consult,’ All studies categorized as ‘Consult’ lacked the iterative process of engagement across several steps. Experts led the research process and target populations had limited decision-making power. Seven studies included in this review were categorized as ‘Consult,’ six of these focused on the development of PROMs/PREMs [36, 38, 39, 41, 43, 57], and one focused on the selection of outcomes [40].

To ‘Consult’ children and families across the selection of outcomes, focus groups were conducted alongside populations to identify relevant health-related quality of life outcomes [40]. Further refinement and analysis of collected data were conducted entirely by experts [40]. Outcomes identified as important by children and families across focus groups were refined by experts and compared to existing measures to identify gaps in the literature [40].

Most studies at the ‘Consult’ level developed items based on existing literature and consulted children and/or families through methods of item reduction or item refinement [36, 38, 39, 41, 43]. One study engaged children in focus groups for concept elicitation and researchers completed the subsequent analysis of transcripts and generation of items [57]. Children and families were engaged in methods to further refine items and ensure clarity through cognitive debriefing. For example, children were instructed to read the developed items out loud to identify any areas of difficulty within items [43]. Other item reduction or refinement strategies at this level included statistical methods, such as the removal of items based on the frequency of missing responses when piloting developed measures [39], and Rasch analysis methods to determine the appropriateness of items [41].

‘Involving’ children and families

Twenty-two studies categorized as ‘Involve’ worked directly with children and families in an iterative process across several steps of outcome selection or PROM/PREM development. These studies clearly engaged children and families across two or more stages of the selection or development process.

The articles which focused on the selection of outcomes consisted of two stages of selection. Both articles involving children and families across outcome selection conducted focus groups to identify which outcomes were important to patients [45, 49]. Dyson et al. conducted a quantitative survey of outcomes with regular parent input to determine which outcomes were important for children with pediatric acute respiratory illness [45]. Outcomes included in the survey were determined by a literature review conducted by professionals [45]. Follow-up focus groups were conducted with the target population to reach a consensus on important outcomes [45].

Franciosi et al. used focus groups and interviews to elicit child and parent preferences regarding outcomes [49]. A priori outcome domains were established through a review of the existing literature to identify themes of focus group discussion [49]. Interviews were conducted with both parents and children and were open-ended in nature to prompt discussion [49]. Interviews were refined alongside parents when analyzing participant interview transcripts [49].

Most of the ‘Involve’ studies that engaged children and families through measure development utilized a combination of interviews or focus groups for concept elicitation paired with further cognitive debriefing for item clarification and refinement [34, 35, 37, 46,47,48, 50, 51, 53, 55, 58,59,60,61, 64]. This iterative approach allowed participants to determine common themes for items and ensured they were comprehensible for children and/or families after cognitive debriefing. When paired with concept elicitation, cognitive debriefing strategies allowed children and families to have increased decision-making power on what was to be included in final measures. Furthermore, it was common for patients to complete existing measures to identify concerns with widely used tools and apply findings to measure development.

‘Collaborating’ with children and families

Four articles were categorized as ‘Collaborate,’ in which authors co-conducted research with children and families across the selection [6, 56] or development [54, 67] process. The two articles which focused on the selection of outcomes collaborated with children and families to identify and prioritize meaningful outcomes to be measured. Both of these articles included children or families as co-applicants for funding and included these stakeholders in regular team meetings [6, 56].

Morris et al. is a peer-reviewed and published protocol that outlines an ongoing study that has begun recruitment [56]. Morris et al. described a protocol for conducting a systematic review of the literature followed by the rating of importance of identified outcomes [56]. The researchers will facilitate three Delphi consensus rounds with children and families to refine and prioritize outcomes [56]. Children and families will be allowed to suggest new outcomes to be included in Delphi rounds if they were not identified by the systematic review [56]. A final meeting, which will include multiple stakeholder groups will be used to further refine outcomes using small plenary discussions and card sorting techniques [56].

Allard et al. [6] conducted a qualitative study alongside children and families to select key health outcomes for children with neurodisability. A research advisory board was established with parents of child patients [6]. Focus groups and semi-structured interviews were conducted with children and their parents to identify their perspectives related to important outcomes [6]. Further interviews with parents included the completion and rating of current PROMs/PREMs and whether they were important [6]. Child participants were shown photographs of an imaginary child and were prompted to identify meaningful outcomes [6]. Children used a ‘Talking Mat’ approach consisting of cartoon images on cards, displayed on a board, to prioritize health outcomes in order of importance [6]. Interview rounds using this method were repeated until consensus was reached [6]. Professionals created a framework for analysis based on focus group transcripts and the youth version of the ICF [6].

Youth were engaged throughout the co-construction of items, co-refinement of data, and cognitive debriefing across the studies related to measure development. Development was divided into succinct stages with researchers acknowledging and acting upon the perspectives of children and families. Focus group rounds were employed across both studies pertaining to concept elicitation, the refinement of items, and cognitive debriefing to ensure item clarity [54, 67]. Both development articles conducted focus groups across at least three stages of measure development [54, 67]. The analysis of focus group data was typically conducted by researchers [54, 67]. One study analyzed data based on the content areas of an existing framework [67]. A different study analyzed data using an inductive framework which was created using child responses [54].

In one study, the collaboration with children and families across development was defined by the creation of a ‘youth team’ to co-conduct research with professionals [54]. Focus groups were conducted with children, by children and researchers. The perspectives of the youth team were acknowledged and considered across the stages of measure development [54]. Furthermore, researchers utilized creative methodologies to convey the perspectives of children and families [54]. Children were prompted to take photographs and record their daily routines [54]. Recordings were played back to children and they were further probed to discuss barriers to participation identified in the recordings [54]. The identified barriers were used to further shape items to be included in measurement tools.

One study engaged children and families on their preferences relating to potential formats and modes of administration of measures through focus groups [67]. Children were separated by age groups and preferences were elicited relating to presentation [67]. The final developed PREMs were pilot tested in a large hospital setting to identify real-time barriers to PREM completion [67].

‘Empowering’ children and families

No articles included in this review were categorized at the ‘Empower’ level of engagement because there were no methods described which involved processes where children and/or families led the selection or development process and had final decision-making power. Table 2 provides a summary of levels of engagement across articles pertaining to the selection of outcomes or development of measures.

Discussion

Patient engagement of children and families in self-report measures is currently at an ‘involve’ level, according to the IAP2 Spectrum. The ‘involve’ level was mainly operationalized through the use of qualitative interviews for measurement content development. It appears that since the publication of regulatory guidelines [26, 27], patient involvement in content development is being implemented in contrast to ‘expert-driven’ methods that characterized the development of earlier legacy measures [69, 70]. This positive shift towards improving the relevance of measures to families has not come at the expense of clinical indicators [71,72,73,74,75] but merely enhances them. The regulatory guidelines that led to this shift towards patient involvement was based in an onus by developers to demonstrate a strong overlap between measurement content, measurement thresholds, and target populations. The guidelines did not require or recommend patients to be involved in the selection of outcomes or in psychometric validation, which remains a missed opportunity to improve the rigor and quality of self-report measures on the basis of child and family participation.

Where there are no specific guidelines on the engagement of selecting PROs and developing their measures within the FDA and EMA guidelines beyond content development, there are opportunities to enhance relevance of research through the co-selection of outcomes between children and families and researchers so that the evidence generated is meaningful to them [7, 19, 25]. Yet this remains a rare exception rather than the rule in research that is used for decision-making such as clinical trials [11]. When outcomes are selected by researchers and clinicians, this does not occur, researchers may insert their own biases into the selection of outcomes used, which then appear as success markers in clinical trials with children [11]. On the development side of participation, there were missed opportunities for children or families to collaborate on areas that impact upon psychometrics such response options and overall formatting and data collection methods. When this was studied, the results were highly informative to scale structure and form [67].

There is an evidence-driven value and impact to collaborating with children and families during measurement [6, 54, 56, 67]; yet there are also barriers to their engagement. Engagement increases the number of steps involved in the development process and hence the costs [76]. Also, depending on the number and level of involvement of the target population, generating participation can be difficult when the topic of measurement seems nebulous relative to intervention. Some of these practical issues such as getting participants to participate may be overcome through the use of creative or novel methods that can promote receptivity. This review found that studies with higher levels of engagement utilized targeted methods to act upon the specific barriers to inclusion, such as arts-based cues for children [6], or photovoice for families [54], and in doing so, promoted receptivity [54]. Children and families can also provide suggestions for how to make their inclusion more feasible and compelling [76].

An outstanding issue remaining at the conclusion of this review is the question as to: “what level of patient engagement should be pursued in the measurement process and why?” ‘Collaborate’ was the highest level of engagement identified and its feasibility demonstrated by exemplars such as ‘youth teams’ who partnered at all phases of decision-making to children facilitating focus groups on their own behalf [6]. Empower levels of engagement in the selection of PROs and development of measures were not found in the literature likely due to the technical expertise required to select and develop PROMs/PREMs. Some examples of empowered measurement selection have been intimated in the adult literature as seen through the prioritization of research areas and the selection of outcomes for patient-driven trials [77, 78]. Yet the outcome of this review has highlighted the importance and value of engagement to enhance the relevance, rigor, and uptake of evidence generated by measures overall. An example of child and family collaboration that reduced the relevance, rigor, or uptake of PROMs and PREMs research was not found.

Conclusion

Reframing children and families from participants of outcomes research, to stakeholders with the potential to co-conduct research, is required to reach a consensus on accurate outcomes and to shape effective measurement tools. Research conducted “for children and young people, by children and young people” [54] has the potential to increase the impact of interventions when outcomes are in alignment with the needs and desires of children and families.

Findings of this review demonstrate that the engagement of children and families across the selection of outcomes and development of PROMs/PREMs varies. Engagement efforts were primarily focused on concept elicitation and item refinement. Although engaging with patients is often valued as integral to research aiming to capture the accurate perspectives of children and families, more collaborative engagement strategies during outcome development remain under-explored.

References

Braithwaite, J., Testa, L., Lamprell, G., Herkes, J., Ludlow, K., McPherson, E., et al. (2017). Built to last? The sustainability of health system improvements, interventions and change strategies: A study protocol for a systematic review. British Medical Journal Open, 7(11), e018568. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018568

Thomson, S., Foubister, T., Figueras, J., Kutzin, J., Permanand, G., & Bryndová, L. (2009). Addressing financial sustainability in health systems. World Health Organization. Retrieved September 2020 from https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/76041/E93058.pdf.

Serebrisky, D., & Wiznia, A. (2019). Pediatric asthma: A global epidemic. Annals of Global Health, 85(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2416

Cohen, E., & Patel, H. (2014). Responding to the rising number of children living with complex chronic conditions. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 186(16), 1199–1200. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.141036

Male, L., Noble, A., Atkinson, J., & Marson, T. (2017). Measuring patient experience: A systematic review to evaluate psychometric properties of patient reported experience measures (PREMs) for emergency care service provision. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 29(3), 314–326. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzx027

Allard, A., Fellowes, A., Shilling, V., Janssens, A., Beresford, B., & Morris, C. (2014). Key health outcomes for children and young people with neurodisability: Qualitative research with young people and parents. British Medical Journal Open, 4, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004611

Morris, C., Janssens, A., Shilling, V., Allard, A., Fellowes, A., Tomlinson, R., et al. (2015). Meaningful health outcomes for paediatric neurodisability: Stakeholder prioritisation and appropriateness of patient reported outcome measures. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13, 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-015-0284-7

Bevans, K. B., Moon, J., Becker, B. D., Carle, A., & Forrest, C. B. (2020). Development of patient-reported outcome measures of children’s oral health aesthetics. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 48(5), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12555

Sinha, I., Jones, L., Smyth, R. L., & Williamson, P. R. (2008). A systematic review of studies that aim to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials in children. PLoS Medicine, 5(4), e96. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050096

Edbrooke-childs, J., Wolpert, M., & Deighton, J. (2016). Using patient reported outcome measures to improve service effectiveness (UPROMISE): Training clinicians to use outcome measures in child mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 302–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0600-2

Fayed, N., de Camargo, O. K., Elahi, I., Dubey, A., Fernandes, R. M., Houtrow, A., et al. (2014). Patient-important activity and participation outcomes in clinical trials involving children with chronic conditions. Quality of Life Research, 23(3), 751–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0483-9

Jain, P., Smith, M. L., Speechley, K., Ferro, M., Connolly, M., Ramachandrannair, R., et al. (2020). Seizure freedom improves health-related quality of life after epilepsy surgery in children. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 62(5), 600–608.

Fortunato, J. E., Troy, A. L., Cuffari, C., Davis, J. E., Loza, M. J., Oliva-Hemker, M., et al. (2010). Outcome after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children and young adults. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 50(4), 390–393.

Mahant, S., Friedman, J. N., Connolly, B., Goia, C., & Macarthur, C. (2009). Tube feeding and quality of life in children with severe neurological impairment. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 94(9), 668–673.

Nelson, K. E., Rosella, L. C., Mahant, S., Cohen, E., & Guttmann, A. (2019). Survival and health care use after feeding tube placement in children with neurologic impairment. Pediatrics, 143(2), e20182863.

Roth, J., Carlson, C., Devinsky, O., Harter, D. H., MacAllister, W. S., & Weiner, H. L. (2014). Safety of staged epilepsy surgery in children. Neurosurgery, 74(2), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000000231

Marshall, S., Haywood, K., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2006). Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: A structured review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 12(5), 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00650.x

Stover, A. M., Haverman, L., van Oers, H. A., Greenhalgh, J., Potter, C. M., Ahmed, S., et al. (2020). Using an implementation science approach to implement and evaluate patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) initiatives in routine care settings. Quality of Life Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02564-9

Fayed, N., Gardecki, M., & Cohen, E. (2018). Partnering with families of children with medical complexity to evaluate interventions. Canadian Medical Association Journal. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.180372

Janvier, A., Farlow, B., Baardsnes, J., Pearce, R., & Barrington, K. J. (2016). Measuring and communicating meaningful outcomes in neonatology: A family perspective. In Seminars in perinatology (Vol. 40, No. 8, pp. 571–577). Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

Fayed, N. (2011). Content issues in child health status and quality of life instruments: Addressing the challenges with new methods (Doctoral dissertation).

Rosenbaum, P. L., Livingston, M. H., Palisano, R. J., Galuppi, B. E., & Russell, D. J. (2007). Quality of life and health-related quality of life of adolescents with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49(7), 516–521.

Raphael, D., Brown, I., Renwick, R., & Rootman, I. (1996). Assessing the quality of life of persons with developmental disabilities: Description of a new model, measuring instruments, and initial findings. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 43(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/0156655960430103

Crudgington, H., Collingwood, A., Bray, L., Lyle, S., Martin, R., Gringras, P., et al. (2020). Mapping epilepsy-specific patient-reported outcome measures for children to a proposed core outcome set for childhood epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior, 112, 107372.

Morris, C., Simkiss, D., Busk, M., Morris, M., Allard, A., Denness, J., et al. (2015). Setting research priorities to improve the health of children and young people with neurodisability: A British Academy of Childhood Disability-James Lind Alliance Research Priority Setting Partnership. British Medical Journal Open, 5(1), e006233. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006233

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. (2009). Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Rockville: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration.

European Medicines Agency. (2005). Regulatory guidance for the use of health-related quality of life (Hrql) measures in the evaluation of medicinal products reproduction. Amsterdam: European Medicines Agency.

International Association for Public Participation. (2004). Public participation spectrum. Retrieved September 2018 from https://iap2canada.ca/Resources/Documents/0702-Foundations-Spectrum-MW-rev2%20(1).pdf.

Frank, L., Forsythe, L., Ellis, L., Schrandt, S., Sheridan, S., Gerson, J., et al. (2015). Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Quality of Life Research, 24(5), 1033–1041.

Esposito, D., Heeringa, J., Bradley, K., Croake, S., & Kimmey, L. (2015). PCORI dissemination and implementation framework. MATHEMATICA Policy Research. Washington, DC, US. Retrieved from http://pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-Dissemination-Implementation-Framework.pdf.

Frank, L., Basch, E., & Selby, J. (2014). Viewpoint: The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. Journal of the American Medical Association, 312(15), 1513–1514.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Covidence. (2020). Retrieved September 2018 from, https://www.covidence.org/about-us/.

Arbuckle, R., Abetz, L., Durmer, J. S., Ivanenko, A., Owens, J. A., Croenlein, J., et al. (2010). Development of the Pediatric Restless Legs Syndrome Severity Scale (P-RLS-SS): A patient-reported outcome measure of pediatric RLS symptoms and impact. Sleep Medicine, 11(9), 897–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2010.03.016

Basra, M. K. A., Salek, M. S., Fenech, D., & Finlay, A. Y. (2018). Conceptualization, development and validation of T-QoL© (Teenagers’ Quality of Life): A patient-focused measure to assess quality of life of adolescents with skin diseases. The British Journal of Dermatology, 178(1), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15853

Bemister, T. B., Brooks, B. L., & Kirton, A. (2014). Development, reliability, and validity of the Alberta Perinatal Stroke Project Parental Outcome Measure. Pediatric Neurology, 51(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.01.052

Bevans, K. B., Gardner, W., Pajer, K., Riley, A. W., & Forrest, C. B. (2013). Qualitative development of the PROMIS(R) pediatric stress response item banks. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss107

Bramhagen, A.-C., Eriksson, M., Ericsson, E., Nilsson, U., Harden, S., & Idvall, E. (2016). Self-reported post-operative recovery in children: Development of an instrument. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 22(2), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12451

Caty, G., Gilles, C., Arnould, C., Thonnard, J. L., & Lejuene, T. (2008). ABILOCO-Kids: A Rasch-built 10-item questionnaire for assessing locomotion ability in children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 40(10), 823–830.

Chang, K. W., Austin, A., Yeaman, J., Phillips, L., Kratz, A., Yang, L., et al. (2017). Health-related quality of life components in children with neonatal brachial plexus palsy: A qualitative study. PM&R, 9(4), 383–391.

Chien, C.-W., Rodger, S., & Copley, J. (2015). Development and psychometric evaluation of a new measure for children’s participation in hand-use life situations. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 96(6), 1045–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2014.11.013

de Kleuver, M., Faraj, S., Holewijn, R. M., Germscheid, N. M., Adobor, R. D., Andersen, M., et al. (2017). Defining a core outcome set for adolescent and young adult patients with a spinal deformity. Acta Orthopaedica, 88(6), 612–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1371371

Dickin, K. L., Lent, M., Lu, A. H., Sequeira, J., & Dollahite, J. S. (2012). Developing a measure of behavior change in a program to help low-income parents prevent unhealthful weight gain in children. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 44(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2011.02.015

Doi, T., Inoue, H., Arai, Y., Shirado, O., Doi, T., Yamazaki, K., et al. (2018). Reliability and validity of a novel quality of life questionnaire for female patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Scoliosis Japanese Questionnaire-27: A multicenter, cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 19(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-2025-7

Dyson, M. P., Shave, K., Gates, A., Fernandes, R. M., Scott, S. D., & Hartling, L. (2017). Which outcomes are important to patients and families who have experienced paediatric acute respiratory illness? Findings from a mixed methods sequential exploratory study. British Medical Journal Open, 7(12), e018199. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018199

Eapen, V., Crncec, R., Walter, A., & Tay, K. P. (2014). Conceptualisation and development of a quality of life measure for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research and Treatment, 2014(101576459), 160783. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/160783

Fabricant, P. D., Robles, A., Downey-Zayas, T., Do, H. T., Marx, R. G., Widmann, R. F., et al. (2013). Development and validation of a pediatric sports activity rating scale: The Hospital for Special Surgery Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale (HSS Pedi-FABS). The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(10), 2421–2429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546513496548

Fiume, A., Deveber, G., Jang, S.-H., Fuller, C., Viner, S., & Friefeld, S. (2018). Development and validation of the Pediatric Stroke Quality of Life Measure. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 60(6), 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13684

Franciosi, J. P., Hommel, K. A., DeBrosse, C. W., Greenberg, A. B., Greenler, A. J., Abonia, J. P., et al. (2012). Quality of life in paediatric eosinophilic oesophagitis: What is important to patients? Child: Care Health and Development, 38(4), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01265.x

Geister, T. L., Quintanar-Solares, M., Martin, M., Aufhammer, S., & Asmus, F. (2014). Qualitative development of the “Questionnaire on Pain caused by Spasticity (QPS)”, a pediatric patient-reported outcome for spasticity-related pain in cerebral palsy. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 23(3), 887–896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0526-2

Gore, C., Griffin, R., Rothenberg, T., Tallett, A., Hopwood, B., Sizmur, S., et al. (2016). New patient-reported experience measure for children with allergic disease: Development, validation and results from integrated care. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 101(10), 935–943. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2015-309598

Heyworth, B., Cohen, L., von Heideken, J., Kocher, M. S., & Iversen, M. D. (2018). Validity and comprehensibility of outcome measures in children with shoulder and elbow disorders: Creation of a new Pediatric and Adolescent Shoulder and Elbow Survey (Pedi-ASES). Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 27(7), 1162–1171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2017.11.009

Klingels, K., Mayhew, A. G., Mazzone, E. S., Duong, T., Decostre, V., Werlauff, U., et al. (2017). Development of a patient-reported outcome measure for upper limb function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: DMD Upper Limb PROM. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 59(2), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13277

Kramer, J. M., & Schwartz, A. E. (2018). Development of the Pediatric Disability Inventory-Patient Reported Outcome (PEDI-PRO) measurement conceptual framework and item candidates. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 25(5), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2018.1502344

Liu, H., Hays, R. D., Marcus, M., et al. (2016). Patient-reported oral health outcome measurement for children and adolescents. BMC Oral Health, 16, 95.

Morris, C., Dunkley, C., Gibbon, F. M., Currier, J., Roberts, D., Rogers, M., et al. (2017). Core health outcomes in childhood epilepsy (CHOICE): Protocol for the selection of a core outcome set. Trials, 18(1), 572. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2323-7

Newcombe, P. A., Sheffield, J. K., Petsky, H. L., Marchant, J. M., Willis, C., & Chang, A. B. (2016). A child chronic cough-specific quality of life measure: Development and validation. Thorax, 71(8), 695–700. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207473

Oluboyede, Y., Hulme, C., & Hill, A. (2017). Development and refinement of the WAItE: A new obesity-specific quality of life measure for adolescents. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 26(8), 2025–2039. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1561-1

O’Sullivan, E. J., & Rasmussen, K. M. (2017). Development, construct validity, and reliability of the questionnaire on infant feeding: A tool for measuring contemporary infant-feeding behaviors. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 117(12), 1983-1990.e1984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2017.05.006

Punpanich, W., Hays, R. D., Detels, R., Chokephaibulkit, K., Chantbuddhiwet, U., Leowsrisook, P., et al. (2011). Development of a culturally appropriate health-related quality of life measure for human immunodeficiency virus-infected children in Thailand. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 47(1–2), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01886.x

Roorda, L. D., Scholtes, V. A., van der Lee, J. H., Becher, J., & Dallmeijer, A. J. (2010). Measuring mobility limitations in children with cerebral palsy: Development, scalability, unidimensionality, and internal consistency of the mobility questionnaire, MobQues47. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91(8), 1194–1209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.009

Santucci, N. R., Hyman, P. E., Karpinski, A., Rosenberg, A., Garguilo, D., Rein, L. E., et al. (2018). Development and validation of a childhood self-efficacy for functional constipation questionnaire. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 30(3), e13222.

Shaikh, N., Martin, J. M., Casey, J. R., Pichichero, M. E., Wald, E. R., Colborn, D. K., et al. (2009). Development of a patient-reported outcome measure for children with streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatrics, 124(4), e557-563. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0331

Tadic, V., Cooper, A., Cumberland, P., Lewando-Hundt, G., Rahi, J. S., & Vision-related Quality of Life Group. (2013). Development of the functional vision questionnaire for children and young people with visual impairment: The FVQ_CYP. Ophthalmology, 120(12), 2725–2732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.07.055

Tsakos, G., Blair, Y., Yusuf, H., Wright, W., Watt, R., & Macpherson, L. (2012). Developing a new self-reported scale of oral health outcomes for 5-year-old children (SOHO-5). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10, 62.

Verschuren, O., Ketelaar, M., Keefer, D., Wright, V., Butler, J., Ada, L., et al. (2011). Identification of a core set of exercise tests for children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: A Delphi survey of researchers and clinicians. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 53(5), 449–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03899.x

Wray, J., Hobden, S., Knibbs, S., & Oldham, G. (2018). Hearing the voices of children and young people to develop and test a patient-reported experience measure in a specialist paediatric setting. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 103(3), 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2017-313032

Wright, W. G., Spiro, A., 3rd., Jones, J. A., Rich, S. E., & Garcia, R. I. (2017). Development of the teen oral health-related quality of life instrument. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 77(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphd.12181

Varni, J. W., Seid, M., & Rode, C. A. (1999). The PedsQL™: Measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Medical Care, 37, 126–139.

Landgraf, J. M., Abetz, L., & Ware, J. E. (1999). Child health questionnaire (CHQ): A user’s manual. Boston, MA: Landgraf & Ware.

Berry, J. G., Graham, D. A., Graham, R. J., Zhou, J., Putney, H. L., O’Brien, J. E., et al. (2009). Predictors of clinical outcomes and hospital resource use of children after tracheotomy. Pediatrics, 124(2), 563–572.

Eapen, V., Črnčec, R., & Walter, A. (2013). Clinical outcomes of an early intervention program for preschool children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in a community group setting. BMC Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-13-3

Wilkinson, J. D., Lowe, A. M., Salbert, B. A., Sleeper, L. A., Colan, S. D., Cox, G. F., et al. (2012). Outcomes in children with Noonan syndrome and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A study from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry. American Heart Journal, 164(3), 442–448.

Biederman, J., Monuteaux, M. C., Doyle, A. E., Seidman, L. J., Wilens, T. E., Ferrero, F., et al. (2004). Impact of executive function deficits and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on academic outcomes in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.757

Langley, K., Fowler, T., Ford, T., Thapar, A. K., Van Den Bree, M., Harold, G., et al. (2010). Adolescent clinical outcomes for young people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 196(3), 235–240.

Wiering, B., de Boer, D., & Delnoij, D. (2017). Patient involvement in the development of patient-reported outcome measures: The developers’ perspective. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 635. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2582-8

Mader, L. B., Harris, T., Kläger, S., Wilkinson, I. B., & Hiemstra, T. F. (2018). Inverting the patient involvement paradigm: Defining patient led research. Research Involvement and Engagement, 4(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-018-0104-4

El-Damanawi, R., Lee, M., Harris, T., Mader, L. B., Bond, S., Pavey, H., et al. (2018). Randomised controlled trial of high versus ad libitum water intake in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: Rationale and design of the DRINK feasibility trial. British Medical Journal Open, 8(5), e022859. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022859

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Sandra McKeown for her knowledge and insight on creating database search strategies.

Funding

The research was funded through the Ontario Child Health Support Unit through OSSU (the Ontario SPOR [Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research] SUPPORT [Support for People and Patient-Oriented Research and Trials] Unit).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest or competing interests to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McNeill, M., Noyek, S., Engeda, E. et al. Assessing the engagement of children and families in selecting patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and developing their measures: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 30, 983–995 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02690-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02690-4