Abstract

Purpose

A sense of meaning and purpose is important for people living with acute and chronic illness. It can buffer the effects of stress and facilitate adaptive coping. As part of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), we developed and validated an item response theory (IRT)-based measure of meaning and purpose in life.

Methods

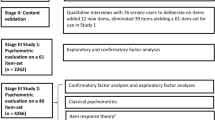

Informed by a literature review and patient and content-expert input, we wrote 52 items to assess meaning and purpose and administered them to a general population sample (n = 1000) along with the Meaning in Life Questionnaire-Presence of Meaning Subscale (MLQ-Presence) and the Life Engagement Test (LET). We split the sample in half for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) followed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). IRT analyses included assessments of differential item functioning (DIF).

Results

Participants had a mean age of 47.8 years and 50.3% were male. EFA revealed one dominant factor and CFA yielded a good fitting model for a 37-item bank (CFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.960, RMSEA = 0.085). All items were free of sex, age, education, and race DIF. Internal consistency reliability estimates ranged from α = 0.90 (4-item short form) to α = 0.98 (37-item bank). The 8-item Meaning and Purpose short form was correlated with the MLQ-Presence (r = 0.89), the LET (r = 0.79), and the full PROMIS Meaning and Purpose item bank (r = 0.98).

Conclusions

The PROMIS Meaning and Purpose measures demonstrated sufficient unidimensionality and displayed good internal consistency, model fit, and convergent validity. Further psychometric testing of the PROMIS Meaning and Purpose item bank and short forms in people with chronic diseases will help evaluate the generalizability of this new tool.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) is an NIH Roadmap/Common Fund initiative to improve and standardize patient-reported outcomes across a range of conditions and demographic characteristics [1, 2]. It is the most ambitious attempt to date to apply models from item response theory (IRT) to health-related assessments across domains of physical, mental, and social health, yielding measures that are flexible, efficient, and precise [3]. The PROMIS approach involves iterative steps of comprehensive literature searches, development of conceptual frameworks, item pooling, qualitative assessment of items using focus groups and cognitive interviewing, and quantitative evaluation of items [4, 5].

The PROMIS initiative has primarily focused on developing instruments to assess health status for chronic conditions. Consequently, item banks developed thus far focus on symptoms and function, such as emotional distress, pain, fatigue, and social function [6]. However, many individuals with chronic conditions experience themselves as more than symptomatic or disabled, having learned to cope with their conditions in positive and adaptive ways [7]. Existing measures of health status often neglect psychological well-being and positive adjustment to illness. Most conceptualizations of psychological well-being include both hedonic (positive affect) and eudaimonic (life satisfaction, meaning, and purpose) components [8, 9]. Psychometrically robust, IRT-informed measures of psychological well-being for healthy and ill adults are sparse. The NIH Toolbox initiative developed measures to assess meaning and purpose (an 18-item bank), but the raw score distributions tended to be negatively skewed, and precision estimates at the high and low ends of the information function continuum were less precise [10].

To address these limitations, we aimed to develop and validate an IRT-based patient-reported outcome tool of meaning and purpose for inclusion in PROMIS. Meaning in life refers to the feeling that one’s life and experiences make sense and matter [11]. Life purpose is characterized by the extent to which one experiences life as being directed, organized, and motivated by important goals [12]. The presence of meaning and purpose in life is considered a core component of mental health [13] and is a protective factor in health outcomes such as morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease [14, 15], quality of life among rheumatoid arthritis patients [16] and prevention of depressive symptoms, including suicidality [17, 18]. Meaning and purpose in life provide important perspectives through which we may better understand patients’ experiences of illness.

We report the development, calibration, and validation of the PROMIS Meaning and Purpose Item Bank. We aimed to (1) refine a patient-reported outcome assessment tool of meaning and purpose for PROMIS and evaluate assumptions for IRT consistent with PROMIS Scientific Standards (e.g., unidimensionality, local independence) [5]; (2) examine item-level properties to support computer adaptive testing and evaluate possible differential item functioning (DIF); and (3) create short forms and examine convergent validity of the PROMIS Meaning and Purpose Short Forms and item bank.

Methods

Participants and procedures

We partnered with Opinions for Good (Op4G), an online research panel, to recruit a demographically diverse, general population sample from the United States (n = 1000). Representativeness of data from internet samples is comparable to data from probability-based general population samples [19]. The internet is an efficient and low-cost means of data collection widely accessible to diverse groups [20]. The Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University approved this study. All interested and eligible participants provided informed consent electronically.

Op4G recruited participants by sending email invitations to a random selection of English-speaking panel members. Target distributions for age and sex were pre-specified (minimum n = 300 in each of three age strata “18–39,” “40–59,” and “60–85” with a minimum n = 120 men and 120 women in each age group), race and ethnicity (minimum n = 200 participants who self-identify as Hispanic or Latino and minimum n = 200 participants who self-identify as Black or African American), and educational attainment (minimum n = 400 for ≤ high school graduate/GED and minimum n = 400 for ≥ some college).

Following screening to ensure eligibility, participants provided informed consent and then completed a demographic survey and other self-report measures (described below). To reduce the potential for order effects, all measures were administered in random, thematic blocks, and order of measures within the blocks were also randomized. Participants who completed questionnaires were eligible for incentive-based compensation and donations made to a charity of their choice by Op4G.

Study measures

PROMIS meaning and purpose item pool

Informed by a literature review and qualitative input from patients and content experts, a pool of 52 items was created [21]. The item pool comprised 18 items from the NIH Toolbox® Meaning and Purpose Item Bank [10], 8 items from the PROMIS Pediatric Meaning and Purpose Short Form [22], and 26 newly written items to ensure adequate content coverage across the meaning and purpose continuum [23]. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” and from “not at all” to “very much.”

NIH Toolbox Meaning and Purpose Short Form

The goal of the NIH Toolbox was to identify, create, and validate brief comprehensive assessment tools to measure cognition, emotion, motor, and sensory function in longitudinal, epidemiological, and intervention studies [24]. Within the emotional health domain, item banks and short forms were developed to assess positive affect, life satisfaction, and meaning and purpose, representing the first effort to develop IRT-informed measures of these important aspects of psychological well-being [25]. The NIH Toolbox Meaning and Purpose Short Form is an 8-item, calibrated short form that assesses the degree to which participants feel their lives matter or make sense [10]. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” and from “not at all” to “very much.” Cronbach’s alpha for this study was 0.92.

PROMIS Pediatric Meaning and Purpose Short Form

The PROMIS Pediatric Meaning and Purpose Short Form is an 8-item, calibrated short form that assesses children’s evaluation of life as having purpose, goals to pursue, and a positive future [26]. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from “not at all” to “very much.” Cronbach’s alpha for this study was 0.95.

Life Engagement Test (LET)

The LET is a self-report measure of purpose in life or the extent to which a person engages in activities that are personally valued [27]. It includes six items rated on a 5-point Likert scale that ranges from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Three of the items are framed positively (e.g., “I value my activities a lot”), and three of the items are framed negatively and reverse-scored (e.g., “There is not enough purpose in my life”). Cronbach’s alpha for this study was 0.86.

Meaning in Life Questionnaire-Presence of Meaning subscale (MLQ-Presence)

The MLQ-Presence is a 5-item, self-report subscale used to evaluate how much participants feel their lives have meaning [28]. Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale with responses ranging from “absolutely untrue” to “absolutely true.” Sample items include, “My life has a clear sense of purpose” and “I understand my life’s meaning.” Cronbach’s alpha for this study was 0.87.

Positive and Negative Affective States (PANAS)

The PANAS is a 20-item, self-report measure that yields separate scores for positive affect (e.g., interested, excited, enthusiastic) and negative affect (e.g., distressed, irritable, afraid) [29]. Participants rate the extent they have felt “this” way over the past week. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale from “very slightly or not at all” to “extremely.” Cronbach’s alpha for this study was 0.92 for both positive and negative affect scales.

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS is a 5-item, self-report measure that captures the degree to which participants are content with or believe they have a good life [30]. Participants are asked to indicate how much they agree or disagree with statements using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” High life satisfaction, along with high positive affect and low negative affect, is considered a key component of subjective well-being and closely related to meaning and purpose in life [31]. Cronbach’s alpha for this study was 0.87.

PROMIS Global-10

The PROMIS Global is a 10-item short form that assesses general domains of health and functioning, including overall physical, mental, and social health, as well as pain, fatigue, and overall perceived quality of life [32]. Participants respond using 5-point Likert scales or an 11-point Likert scale (i.e., pain) to indicate the quality of their health or the frequency or severity of their symptoms. We used the physical and mental health summary scores for this project. Cronbach’s alphas for the summary scores were 0.77 for Global Physical Health and 0.80 for Global Mental Health.

Statistical analysis

We followed the general guidelines used in the PROMIS Scientific Standards for item bank development [4, 5, 33] and grouped them into three stages: (1) testing assumptions for IRT modeling; unidimensionality and local independence of items; (2) estimating item parameters using IRT, IRT-based local dependence analysis, evaluating items for DIF; and (3) selecting items for static short forms and examining preliminary validity. After reviewing item content and analytic results, we used group consensus to decide the final composition of the static short forms.

During the first stage, we examined items for sparse data within any rating scale response category (i.e., n < 5). Data were randomly divided into two datasets (n = 500 each), one for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the other for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We used the psych package in R for exploratory analyses [34, 35], and MPlus 7.2 [36] for confirmatory analysis. We applied EFAs of the polychoric correlation matrix with oblique rotation to identify potential factors among items; CFA was used to confirm final factor structure. In the EFAs, we examined the scree plot and parallel analysis as criteria to estimate meaningful factors. Parallel analysis compares the succession of factors of the observed data with that of a random data of the same size [37]. Items representing secondary factors or with loadings < 0.4 on the primary factor were considered for exclusion. Next, we estimated the proportion of total variance attributable to a general factor with omega hierarchical (omega-h) using the psych package [34]. This method estimates omega-h from the general factor loadings derived from an exploratory factor analysis and a Schmid–Leiman transformation [38]. Values of 0.70 or higher suggest that the item set is sufficiently unidimensional [39]. Finally, arriving at a single-factor model, we examined residual correlations to identify any remaining locally dependent item pairs (> 0.20).

For CFA, we evaluated the final selection of items in a single-factor model with fit statistics. We used the weighted least squares estimator with adjustments for the mean and variance (WLSMV) in Mplus, based on a polychoric correlation matrix, as appropriate for the ordered categorical data [40]. We selected the commonly used indices for item banking as recommended by PROMIS Scientific Standards: Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). We used the following model fit indices as guidelines: RMSEA < 0.08; CFI > 0.95; TLI > 0.95 [4].

In the second stage, the total sample (n = 1000) was used and items that met unidimensionality assumptions were analyzed using Samejima’s Graded Response Model (GRM) [41] as implemented in IRTPRO software [42, 43]. The GRM is one of the most commonly used IRT models in health-related quality of life research [44]. Item threshold parameters represent items along the measured trait and show the coverage across the meaning and purpose continuum. The item slope parameter represents the discriminative ability of the items, with higher slope values indicating better ability to discriminate between adjoining values on the construct. Items displaying poor IRT fit (criterion: significant S–χ2 fit statistic, p < 0.01 [45, 46]) and poorly discriminating items (i.e., those with unacceptable IRT slopes; criterion: slope < 1) were candidates for exclusion at this stage. To ensure that parameter estimates are not unduly distorted by pairs of associated items, we assessed local dependence in the IRT framework with the chi-square (LD χ2) statistic; values of 10 or greater are considered large and unexpected [43].

We used the lordif package in R to conduct DIF analyses on the basis of age (“18–39” versus “40–59,” “18–39” versus “60–85,” “40–59” versus “60–85”), sex (“male” versus “female”), education (“ ≤ high school” versus “ ≥ some college”) and race (“White” versus “non-White,” “Black” versus “non-Black”) for groups with a minimum of 150–200 participants per subgroup [47]. An item has significant DIF if the item exhibits different measurement properties between subgroups, which is similar to “item bias.” We tested for DIF using an ordinal logistic regression procedure [48] with χ2 to detect items (p < 0.01), and McFadden pseudo R2 > 0.02 as the threshold for substantial DIF [49]. Items that demonstrated DIF greater than R2 > 0.02 were considered for removal.

In the third and final stage, a fixed-length short form was determined by consensus. Our team of content-expert consultants, psychometricians, and measurement scientists reviewed item content, threshold, and slopes for all meaning and purpose items in the newly calibrated bank to identify optimal 4-, 6-, and 8-item short forms. Finally, the convergent validity of the PROMIS Meaning & Purpose Item Bank and 8-item Short Form were examined using bivariate Pearson correlations with comparable constructs. For measures that provided item content for the development of the PROMIS Meaning & Purpose Item Pool and served as comparison measures (e.g., NIH Toolbox), we examined correlations with and without overlapping items. We hypothesized that the PROMIS Meaning & Purpose Item Bank and Short Forms would demonstrate the largest correlations with the NIH Toolbox Meaning and Purpose Short Form but would also be significantly correlated with the LET and the MLQ-Presence. We also expected PROMIS Meaning & Purpose scores to be significantly correlated with the PROMIS Global Mental Health scores and less strongly correlated with the PROMIS Global Physical Health scores.

Results

Sample characteristics

Our sample comprised approximately equal numbers of older (ages 60 to 85), middle-aged (ages 40 to 59), and young (ages 18 to 39) adults. It was primarily non-Hispanic, White (62.1%) but had good representation from racial and ethnic minorities. Approximately equal numbers of participants had received a high school education or less and greater than a high school education. The most common comorbidities reported were high blood pressure (39.2%), anxiety (27.7%), depression (27.0%), arthritis (26.6%), and migraines (24.2%). Additional demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

IRT assumptions

We examined frequencies for the 52-item PROMIS Meaning and Purpose Item Pool to ensure adequate numbers of responses for each category for all items. None of the candidate items had sparse data (i.e., n < 5) within any response category. Item-total correlations ranged from r = 0.52 “I understand the world around me” to r = 0.86 “My life has purpose.” To establish the relative unidimensionality of the PROMIS Meaning and Purpose Item Pool, we randomly split the sample into halves and conducted EFAs on the first half (n = 500) and a CFA on the second half to confirm a single model fit for the final item set. The EFAs were conducted with the psych package in R by generating a polychoric correlation matrix, followed by weighted least squares estimation. We first examined the unidimensionality of the item data with a scree plot, parallel analysis, and the residual correlation matrix of the single-factor model. Results suggest that a second factor is formed by the reverse-scored items (nearly all showed residual correlations > 0.20). The two-factor EFA model (oblimin rotation) showed a dominant factor (eigenvalue = 26.5; 51% variance explained) with a second distinguishable factor (eigenvalue = 8.6; 17% variance explained) defined by the 10 negatively worded items (e.g., “Most of what I do seems trivial and unimportant to me”). The output of this two-factor model is presented as electronic supplementary material along with each item. Given the potential for the multidimensionality introduced by negatively worded items to distort the interpretation and reliability of our final instrument’s scores, we opted to remove these items from further consideration.

During the exploratory phase of our analysis, we also removed five additional items based on conceptual and content grounds. We excluded three conceptually weaker items (“I feel grateful for each day,” “I expect to enjoy my future life,” “I feel hopeful about my future”). Finally, we excluded two additional items that were redundant with other item content (“I have a reason for living” and “I know where I am going in my life.”).

Next, we investigated distribution and unidimensionality of the remaining 37-item set. The frequency response distribution of these 37 items revealed a distribution with small level of skew (Mean = 134.3, SD = 33.4, Median = 140, Range = 38 to 185; Fig. 1). Turning to unidimensionality, we produced a combined scree and parallel analysis plot of these items (Fig. 2). This plot shows that all secondary factors have eigenvalues below 1 and close to the eigenvalues produced by random data. Consistent with these findings, the omega-hierarchical index (based on the polychoric correlations) produced a high value (0.87) suggesting the presence of a dominant general factor.

Finally, we conducted a single-factor CFA on a polychoric correlation matrix of the other half of the sample (n = 500). Acceptable fit indices were obtained CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.085). Table 2 shows the relatively high factor loadings of this model, ranging from 0.65 to 0.92. Thus, the proposed meaning and purpose bank was essentially unidimensional for purposes of scaling with IRT models.

Estimating item parameters and evaluating DIF

Once we established essential unidimensionality, the next step was to calibrate the new meaning and purpose bank using estimated IRT parameters from a GRM to inform item slope (discrimination) and threshold (location) parameters. All item slopes were > 1.0, which met our inclusion criteria with the average slope = 2.28. The location parameters ranged from − 5.59 to 1.38. However, two items suggested a poor fit (S–χ2 < 0.01) and were candidates for exclusion (“I have a reason for living,” “My life matters”).

Next we examined local dependency statistics. Out of 666 possible pairs, 60 pairs showed X2 LD values of 10 or higher, affecting 16 items (out of 37). Because local dependencies may inflate discrimination parameter estimates, we estimated additional models. First, we identified 21 items that were relatively free of local dependencies. We then re-ran each of the 16 LD items with this 21 item set, and compared the resulting parameters with those that were generated from the full 37-item set. Discrimination parameter estimates from the 21 + 1 calibration runs were very similar to those obtained as part of the 37-item set. The average difference was 0.06 (range − 0.29 to 0.30). The average discrimination parameter value for the 21 + 1 item runs was 2.79 (range 1.91 to 3.90). The average for those same items in the 37-item calibration was only slightly higher, 2.85 (range 1.88 to 4.06). We concluded that local dependencies did not meaningfully bias parameter estimates.

None of the 37 items exceeded the McFadden pseudo R2 threshold of 0.02 in any of the DIF comparisons (sex, age, education, and race). Since the two items with poor fit had good slopes, were free of DIF, and provided important and conceptually congruent content for meaning and purpose, they were retained for the final bank.

Next, IRT parameters were estimated using a GRM and linked to the NIH Toolbox metric, such that T-scores (M = 50 and SD = 10) are comparable and representative of the United States 2010 census [50, 51]. This was accomplished by following the multi-method linking procedure described by PROsetta Stone investigators [52]. Briefly, we obtained the official Toolbox item parameters from the investigators, and used these previously established values to fix the 10 overlapping items to anchor our analyses. In a co-calibration of the 10 Toolbox items, the new 27 Meaning and Purpose PROMIS items were freely estimated. As a second method, we used the Stocking-Lord procedure [53] to estimate linking constants defined by the difference of Toolbox item parameters we obtained from our sample compared to those we received from the Toolbox developers. The resulting linking constants were as follows: A = 1.314 and B = − 0.525. They were then applied uniformly to the 27 new PROMIS item parameters to place them on the Toolbox metric. Both the fixed co-calibration and the Stocking-Lord methods lead to similar test characteristic curves, with a maximum expected score difference of 2.25 points on a raw summed score range of 148 (37 × 4) at very low levels of the trait (< 2 SDs below the mean). The resulting Stocking-Lord linking constants (A = 1.314 and B = − 0.525) were applied to the PROMIS item parameters to place them on the Toolbox metric.

Identifying a short form and examining preliminary validity

Of particular relevance for identifying the “best” items for short forms was the information accounted for by each item across the meaning and purpose continuum. These calibrations and content considerations (identifying a conceptual range of meaning and purpose concepts) guided the selection of 4-, 6-, and 8-item short forms (Table 3) to go along with the 37-item bank. The 4-, 6-, and 8-item short forms and item bank demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability, with coefficient αs = 0.90, 0.91, 0.93, and 0.98, respectively. In addition, the short forms were all positively correlated with the item bank (rs = 0.94 to 0.96). Table 4 presents bivariate correlations among the PROMIS Meaning & Purpose Short Forms and Item Bank with related constructs (life engagement, presence of meaning, positive affect, life satisfaction), the NIH Toolbox Meaning and Purpose Short Form and the PROMIS Global-10. All correlations between the PROMIS Meaning and Purpose short forms and the legacy measures, the MLQ-Presence and the LET were significant (p < 0.001) with rs = 0.75 or higher. Similarly, high correlations were found between the PROMIS Meaning and Purpose Short Forms and the comparable Toolbox and Pediatric short forms (rs = 0.87 to 0.96). Not surprisingly, correlations with the PROMIS Global measure were stronger with the Mental score (rs = 0.65 to 0.67) than with the Physical score (rs = 0.37 to 0.39) (Fig. 2).

Conclusions

The PROMIS Meaning and Purpose measure demonstrated sufficient unidimensionality and good internal consistency, model fit, and convergent validity. This is the first report summarizing the psychometric properties of this important component of psychological well-being for PROMIS and one of only three studies of which we are aware that applied a systematic, rigorous, and state-of-the-art measurement development approach to create a patient-reported outcome measure of meaning and purpose [10, 26, 54]. Of those three studies, only one measure (NIH Toolbox Meaning and Purpose Item Bank) was designed for use among healthy and ill adults [10]. The PROMIS Meaning and Purpose Item Bank builds on and extends the work of the NIH Toolbox in order to refine and strengthen the assessment of this important domain and further our understanding of healthy adaptation to illness.

The content of our Meaning and Purpose Bank was represented by 37 items that cover the conceptual breadth of the construct and yet remain sufficiently unidimensional. Recent work in the measurement of meaning in life suggests it comprises distinct but related concepts of mattering, purpose, and comprehension [23]. Other measurement approaches have focused on the search for meaning as well as the presence of meaning [28]. Within the scope of PROMIS, we prioritized the presence of meaning while also intentionally capturing the range of the construct, identifying existing and writing new item content [21]. One dominant factor that included items from the tripartite approach to meaning in life emerged in our large general population sample. While not necessarily precluding a tripartite understanding of meaning, this finding does suggest the presence of an underlying, general meaning in life factor.

Our calibration testing further supported the potential utility of the PROMIS Meaning and Purpose Item Bank. In contrast to the NIH Toolbox Meaning and Purpose Item Bank, we obtained a normal distribution of scores from a similar general population sample. Although both measurement approaches can be administered as computer adaptive tests, the PROMIS Meaning and Purpose Item Bank includes 12 of the Toolbox Meaning and Purpose Bank items (all but the 5 negatively worded items and the item “I feel grateful for each day”) as well as an additional 25 items. Thus, administration of the full 37 items of the PROMIS Meaning and Purpose Bank or flexible administration of the Bank as a computer adaptive test should yield greater precision than the NIH Toolbox measure, over the range of the latent meaning and purpose continuum.

The newly developed PROMIS Meaning and Purpose Short Forms and item bank all had excellent internal consistency reliability and evidence of convergent validity. Although there are no true “gold standards” for assessing meaning in life within health-related research, the measures we included as indices of convergent validity are some of the more commonly used and psychometrically sound, brief measures of meaning and purpose [11, 27, 28] as well as the most commonly used measures of related well-being concepts of positive affect [29] and life satisfaction [30]. Although our item bank included overlapping content, the convergent validity correlations remained quite strong even after excluding the redundant items from the PROMIS measures. Similarly, the correlations with the existing NIH Toolbox and Pediatric PROMIS measures of meaning and purpose were quite large, suggesting considerable overlap in the construct. Lastly, the positive associations with global mental and global physical quality of life underscore the relationship between meaning in life and positive health [55,56,57,58].

Study limitations should be acknowledged: The cross-sectional design precludes examining potential responsiveness of the PROMIS Meaning in Life measures. A robust body of work focuses on meaning-making within the context of acute and chronic illnesses [7, 59,60,61,62] and the mutability of meaning is an important, patient-centered outcome. Further, psychosocial interventions to promote meaning have demonstrated efficacy [63] and psychometrically sound indices of meaning in life that capture change over time with minimal participant burden and maximal measurement precision are inherently valuable. A related concern is that the current calibration and validation testing did not include a clinical sample. Since PROMIS measures are designed for patients with a range of acute and chronic illnesses, it is not yet known how these new measures will perform among patients. To establish useful T-scores, it is important to calibrate and validate these new measures with a general population sample to serve as a meaningful reference group as a first step. Subsequent work will extend and increase the psychometric evidence for the PROMIS Meaning and Purpose measures.

In summary, the work described here provides initial and strong psychometric support for the PROMIS Meaning and Purpose item bank and short forms. These assessment tools were designed to aid clinicians and researchers to better evaluate and understand the potential role of positive psychological processes for individuals with chronic health conditions. Further psychometric testing to examine criterion validity and responsiveness alongside commonly used measures of psychological well-being and in patients with chronic diseases will help evaluate the added benefit and generalizability of these new measures.

References

Cella, D., et al. (2010). Initial adult health item banks and first wave testing of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS™) Network: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,63(11), 1179.

Cella, D., et al. (2010). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,63(11), 1179–1194.

Segawa, E., Schalet, B., & Cella, D. (2020). A comparison of computer adaptive tests (CATs) and short forms in terms of accuracy and number of items administrated using PROMIS profile. Quality of Life Research,29(1), 213–221.

Reeve, B. B., et al. (2007). Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: Plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Medical Care,45(5 Suppl 1), S22–S31.

PROMIS Health Organization and PROMIS Cooperative Group. (2013). PROMIS® Instrument Development and Validation: Scientific Standards Version 2.0 (revised May 2013). Retrieved September 19, 2013, from https://www.nihpromis.org/Documents/PROMISStandards_Vers2.0_Final.pdf.

Cook, K. F., et al. (2016). PROMIS measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,73, 89–102.

Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress,17(1), 11–21.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology,52, 141–166.

Samman, E. (2007). Psychological and subjective wellbeing: A proposal for internationally comparable indicators. Oxford Development Studies,35(4), 459–486.

Salsman, J., et al. (2014). Assessing psychological well-being: Self-report instruments for the NIH Toolbox. Quality of Life Research,23(1), 205–215.

Steger, M. F., Oishi, S., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. Journal of Positive Psychology,4(1), 43–52.

McKnight, P. E., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Review of General Psychology,13(3), 242–251.

Fusar-Poli, P., et al. (2020). What is good mental health? A scoping review. European Neuropsychopharmacology,31, 33–46.

Koizumi, M., et al. (2008). Effect of having a sense of purpose in life on the risk of death from cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Epidemiology,18(5), 191–196.

Kim, E. S., Delaney, S. W., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2019). Sense of purpose in life and cardiovascular disease: Underlying mechanisms and future directions. Current Cardiology Reports,21(11), 135.

Verduin, P. J., et al. (2008). Purpose in life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical Rheumatology,27(7), 899–908.

Mascaro, N., & Rosen, D. H. (2005). Existential meaning's role in the enhancement of hope and prevention of depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality,73(4), 985–1013.

Costanza, A., Prelati, M., & Pompili, M. (2019). The meaning in life in suicidal patients: the presence and the search for constructs. A systematic review. Medicina (Kaunas),55(8), E465.

Liu, H., et al. (2010). Representativeness of the PROMIS Internet Panel. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,63(11), 1169–1178.

Roster, C. A., et al. (2004). A comparison of response characteristics from web and telephone surveys. International Journal of Market Research,46(3), 359–374.

Salsman, J. M., et al. (2018). Refining and supplementing candidate measures of psychological well-being for the NIH PROMIS(R): Qualitative results from a mixed cancer sample. Quality of Life Research,27(9), 2471–2476.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., et al. (2014). Subjective well-being measures for children were developed within the PROMIS project: Presentation of first results. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,67(2), 207–218.

George, L. S., & Park, C. L. (2016). Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering: Toward integration and new research questions. Review of General Psychology,20(3), 205.

Gershon, R. C., et al. (2010). Assessment of neurological and behavioural function: the NIH Toolbox. Lancet Neurology,9(2), 138–139.

Salsman, J. M., et al. (2013). Emotion assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology,80(11 Supplement 3), S76–S86.

Forrest, C. B., et al. (2019). Assessing children's eudaimonic well-being: The PROMIS pediatric meaning and purpose item banks. Journal of Pediatric Psychology,44(9), 1074–1082.

Scheier, M., et al. (2006). The Life Engagement Test: Assessing purpose in life. Journal of Behavioral Medicine,29(3), 291–298.

Steger, M. F., et al. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology,53(1), 80–93.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,54(6), 1063–1070.

Diener, E., et al. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment,49(1), 71–75.

Diener, E., et al. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin,125(2), 276–302.

Hays, R. D., et al. (2009). Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Quality of Life Research,18(7), 873–880.

Pilkonis, P. A., et al. (2011). Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS):depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment,18(3), 263–283.

Revelle, W., Psych: Procedures for personality and psychological research (R Package Version 1.8.12) [Computer software]. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University, 2019. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psych/index.html.

R Core Development Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.r-project.org/.

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen.

Humphreys, L. G., & Montanelli, R. G., Jr. (1975). An investigation of the parallel analysis criterion for determining the number of common factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research,10(2), 193–205.

Schmid, J., & Leiman, J. (1957). The development of hierarchical factor solutions. Psychometrika,22(1), 53–61.

Reise, S. P., et al. (2013). Multidimensionality and structural coefficient bias in structural equation modeling: A bifactor perspective. Educational and Psychological Measurement,73(1), 5–26.

Muthén, B., et al. (1997). Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. Unpublished Paper.

Samejima, F. (1969). Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometrika Monograph Supplement, No. 17. 1969. Richmond, VA: Psychometric Society.

Thissen, D. (2003). MULTILOG. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International Inc.

Cai, L., Thissen, D., & de Toit, S. (2011). IRTPRO 2.01. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International.

Preston, K., et al. (2011). Using the nominal response model to evaluate response category discrimination in the PROMIS emotional distress item pools. Educational and Psychological Measurement,71(3), 523–550.

Orlando, M., & Thissen, D. (2003). Further examination of the performance of S-X 2, an item fit index for dichotomous item response theory models. Applied Psychological Measurement,27, 289–298.

Kang, T., & Chen, T. T. (2011). Performance of the generalized S-X2 item fit index for the graded response model. Asia Pacific Education Review,12(1), 89–96.

Scott, N. W., et al. (2009). A simulation study provided sample size guidance for differential item functioning (DIF) studies using short scales. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,62(3), 288–295.

Zumbo, B. D. (1999). A handbook on the theory and methods of differential item functioning (DIF): Logistic regression modeling as a unitary framework for binary and Likert-type (ordinal) item scores. Ottawa, ON: Directorate of Human Resources Research and Evaluation, Department of National Defense.

Choi, S. W., Gibbons, L. E., & Crane, P. K. (2011). lordif: An R package for detecting differential item functioning using iterative hybrid ordinal logistic regression/item response theory and Monte Carlo simulations. Journal of Statistical Software,39(8), 1–30.

Beaumont, J. L., et al. (2013). Norming plans for the NIH Toolbox. Neurology,80(11 Supplement 3), S87–S92.

Babakhanyan, I., et al. (2018). National Institutes of Health Toolbox Emotion Battery for English- and Spanish-speaking adults: Normative data and factor-based summary scores. Patient Related Outcome Measures,9, 115–127.

Choi, S. W., et al. (2014). Establishing a common metric for depressive symptoms: Linking the BDI-II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 to PROMIS depression. Psychological Assessment,26(2), 513–527.

Stocking, M. L., & Lord, F. M. (1983). Developing a common metric in item response theory. Applied Psychological Measurement,7(2), 201–210.

Carlozzi, N. E., et al. (2016). New measures to capture end of life concerns in Huntington disease: Meaning and purpose and concern with death and dying from HDQLIFE (a patient-reported outcomes measurement system). Quality of Life Research,25(10), 2403–2415.

Zika, S., & Chamberlain, K. (1992). On the relation between meaning in life and psychological well-being. British Journal of Psychology,83(Pt 1), 133–145.

Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics,83(1), 10–28.

Steptoe, A., Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2015). Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. The Lancet,385(9968), 640–648.

Czekierda, K., et al. (2017). Meaning in life and physical health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review,11(4), 387–418.

Lee, V. (2008). The existential plight of cancer: Meaning making as a concrete approach to the intangible search for meaning. Supportive Care in Cancer,16(7), 779–785.

Park, C. L. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin,136(2), 257–301.

Martz, E., & Livneh, H. (2016). Psychosocial adaptation to disability within the context of positive psychology: findings from the literature. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation,26(1), 4–12.

Leonhardt, B. L., et al. (2017). Recovery and serious mental illness: A review of current clinical and research paradigms and future directions. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics,17(11), 1117–1130.

Park, C. L., et al. (2019). Effects of psychosocial interventions on meaning and purpose in adults with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer,125(14), 2383–2393.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the NIH under award number K07CA158008. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Portions of this manuscript were previously presented: Salsman, J.M., Park, C.L., Schalet, B., Hahn, E.A., Steger, M.F., George, L., Snyder, M.A., & Cella, D. (2015). Assessing meaning & purpose in life: Development and validation of an item bank and short forms for the NIH PROMIS. Quality of Life Research, 24(Suppl.1), 144.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salsman, J.M., Schalet, B.D., Park, C.L. et al. Assessing meaning & purpose in life: development and validation of an item bank and short forms for the NIH PROMIS®. Qual Life Res 29, 2299–2310 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02489-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02489-3