Abstract

Purpose

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) may be helpful in identifying children at risk of developing adjustment problems. Few studies have focused on HRQoL among children of ill or substance abusing parents despite their considerable risk status. In the present study, we used the KIDSCREEN-27 to assess self-reported HRQoL in children and adolescents living in families with parental illness, or substance dependence. First, we tested whether the factor structure of the KIDSCREEN-27 was replicated in this population of children. Next, we examined differences in HRQoL according to age, gender, and type of parental illness. Finally, we compared levels of HRQoL in our sample to a normative reference population.

Method

Two hundred and forty-six children and adolescents aged 8–17 years and their ill parents participated. The construct validity of the KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire was examined by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). T-tests and ANOVA were used to test differences in HRQoL levels according to age, gender, and parental patient groups, and for comparisons with reference population.

Results

The KIDSCREEN-27 fit the theoretical five-factor model of HRQoL reasonably well. Boys and younger children reported significantly greater well-being on physical well-being, psychological well-being, and peers and social support, compared to girls and older children. Younger children also reported significantly greater well-being at school than did older children. There were no significant differences in HRQoL between groups of children living with different type of parental illness. The children in our sample reported their physical well-being significantly lower than the reference population.

Conclusion

The KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire appears to work satisfactorily among children of ill or substance abusing parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parental illness affects the whole family. The effects on children of ill parents may be particularly strong, because children’s adjustment is so closely tied to their parents’ ability to care for them. Reduced parental capacity is often a consequence of physical or mental illness, or substance abuse, it can jeopardize children’s psychosocial development and have a negative influence on children’s quality of life [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Although children of ill and substance abusing parents are at risk, they are not a clinical population per se.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a construct that can be useful in assessing the consequences of stressful life events such as parental illness [16,17,18]. It has been defined as: “the impact of perceived health on an individual’s ability to live a fulfilling life” [19]. HRQoL has been reported to be inversely associated with mental health problems in children [16, 20,21,22]. Although this negative correlation is a relatively common empirical finding, low HRQoL scores do not necessarily translate into the presence of psychosocial problems, nor do high HRQoL scores automatically denote the absence of mental health issues [23]. Simply put, HRQoL is not the mere absence of symptoms.

HRQoL may be a precursor to psychosocial problems later on. In a longitudinal study of 4500 Chinese adolescents, results indicated that youths’ life satisfaction predicted their future positive development, which in turn mitigated problem behavior [24]. Hence, HRQoL may be an appropriate measure to use in identifying individuals at risk and an important addition to traditional symptom scales.

The consequences of challenging life experiences for children may not always be heightened scores on symptoms scales. Indeed, the effects of stressful life circumstances can take on several forms, of which reduced quality of life is one. Before using measures of HRQoL for these purposes, however, an important first step is to make sure that the measure in question is valid and fits the theoretical structure of the construct.

HRQoL has predominantly been used to measure quality of life in samples experiencing some type of physical or mental disorder [23], or in research with normative samples [25, 26]. Fewer studies have looked at HRQoL in samples of children living with parental illness and substance abuse. There is gap in the literature concerning whether the construct validity of HRQoL holds for this population of children as well.

The construct of HRQoL

HRQoL is a common approach to the conceptualization of the broader concept quality of life (QoL). QoL has been defined by the World Health Organization as “an individual’s perception of his/her position in life in the context of the culture in which he/she lives and in relation to his/her goals, expectations, standards and concerns” [27]. According to Wallander and Koot [23], HRQoL has dominated the field in both child and adult literature on QoL. They list Social indicators and Subjective Well-being as two alternative approaches. Because QoL goes beyond measuring symptom- or performance indicators, but rather gauges a person’s satisfaction with life in the here and now, the person him- or herself is in the best position to make the judgement. Thus, measures of HRQoL ought to be individual, subjective reports whenever possible and measurements of HRQoL should be multidimensional because how well a person perceives his or her life to be has multiple sources. Common dimensions of HRQoL include physical, psychological, and social components, which may compensate for, or depend on each other. The multidimensionality of HRQoL makes it pertinent to examine both the respective dimensions of the concept but also the overall score for the population of interest.

KIDSCREEN-27

The KIDSCREEN-27 measures HRQoL in children and adolescents and is a well-known and frequently used questionnaire, particularly in European samples. The KIDSCREEN-27 measures perceptions of general health and fitness, and psychological indicators such as mood, feelings of loneliness, autonomy, relationship with peers and parents, social support, and adjustment at school [16, 28, 29]. The KIDSCREEN-27 conforms to the conceptual considerations of HRQoL [30]. No study has to our knowledge tested the factor structure of this questionnaire in children living in families with parental illness and substance abuse.

Age, gender, and type of parental illness

HRQoL scores vary according to the age and gender of the child. Studies have indicated that boys tend to report higher levels of HRQoL than do girls [21, 25, 31,32,33,34,35], and that younger children tend to report higher levels of HRQoL compared to older children and adolescents [21, 25, 31,32,33,34,35,36]. In a study with a normative sample, lower parental physical and mental health was associated with lower HRQoL in the adolescent children [32]. In ill or substance abusing parents who are in treatment, however, few studies have explored levels of HRQoL among their children. It appears that the studies that have explored HRQoL in children of ill parents are limited to children experiencing parental cancer [31, 37], although a few studies have involved children of parents with other types of somatic illness [38], depression [39], or substance abuse [40]. This scarcity of empirical work highlights the need for more research, especially psychometric investigations of instruments and studies with children with different types of family risk.

Parental mental illness and substance abuse may expose children to different challenges compared to those experienced by children of physically ill parents. Parental mental illness and substance abuse may more often be associated with unstable home environments, which affect children’s adjustment beyond the illness or substance abuse itself [41]. Parental mental illness and substance abuse often bring about impaired social functioning [42], parental unresponsiveness, and ineffective parenting practices [43,44,45,46]. For parents who use alcohol or drugs, problems may also include preoccupation with obtaining substances, and recovery from the effects of these [47], in addition to possible comorbid mental illness. Although physical illness in parents is likely to affect parental participation in activities and chores, we hypothesize that children of parents with mental illness or substance abuse will report lower HRQoL compared to children of physically ill parents. No studies have to our knowledge, compared HRQoL in children from these three categories of parental illness.

The present study

The first goal of the present study was to examine the factor structure of the KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire in a sample of children whose parents were either physically or mentally ill or substance abusing. Factor structure was tested using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Next, we explored whether levels of HRQoL in our sample varied depending on children’s gender, age, and type of parental illness. Finally, we compared the levels of HRQoL-dimensions in our sample with those of a normative reference population [48].

Method

Participants

Participants were 246 children and adolescents, aged 8–17 years, (M = 12.45, SD = 2.85). Girls made up 56.9% of the sample. The child’s mother was the ill parent in 72.7% of the cases. Both the ill or substance abusing parent and one of their children were part of the current study. Data from eight children did not have corresponding parent report. The majority of the families (93.3%) had Norwegian ethnic background. On average, families’ socioeconomic status placed them in middle-class by Norwegian standards, and patients in somatic health services reported significantly higher incomes than patients from mental health and substance abuse clinics. Descriptive statistics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The current study was part of a nationwide cross-sectional multicenter study in Norway [49].

Procedures

Data were collected over a period of 21 months (from March 2013 to January 2015) in five health authorities across Norway. Specialized health care services in Norway are administered by geographically sectioned health authorities and serve patients with serious health challenges. Specialized health care services in Norway are typically divided into somatic, mental health, and substance abuse clinics. The children were identified and recruited via their parents who were treated in one these three types of specialized services (including both out-patient and inpatient clinics). Each patient and child was given written and oral information about the study. If the patient was a caregiver for more than one dependent child, we randomly chose one child to participate, unless the parents expressed a preference.

Interviews were conducted by trained personnel (health care workers or research associates) who met with the family at a convenient time and location, usually at the home of the family. The parent and the child were handed an iPad each and given instructions on how to complete the questionnaires. The digital data collection strategy ensured no missing data at the individual participant level. The interviewers were available for guidance during the session and they were instructed to request that parents and children were sitting apart when they completed the questionnaires The estimated time to complete the questionnaire was 1 h.

Measurements

KIDSCREEN-27

HRQoL was assessed with the KIDSCREEN-27, which is a shorter version of the KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire. It is a generic HRQoL questionnaire developed for children aged 8–18 years [48]. The KIDSCREEN-27 was found to be a reliable and valid measure in a large population-based sample of European children and adolescents [21]. Good reliability and validity ratings have also been reported in a normative population of 10-year old children in Norway [50].

The KIDSCREEN-27 is a self-report questionnaire and assesses five dimensions of well-being; physical well-being (5 items), psychological well-being (7 items), autonomy and parent relations (7 items), peer-relations and social support (4 items), and school environment (4 items). The recall period is 1 week and each item assesses either the frequency or intensity of a behavior or feeling, on a five-point scale. Four items are reversed. Raw scores are transformed based on algorithms for each dimension and used to compute T-scores, with mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 [16]. The total KIDSCREEN score is the sum of all item responses. Higher scores indicate greater HRQoL. Two-week test–retest reliability has been reported to be acceptable with intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) ranging from 0.61 to 0.74 for the different dimensions [21]. In the present study, Cronbach’s α ranged from .79 to .90. Cronbach’s α for the entire scale was .94, but may be somewhat inflated by the higher number of items. The full range of response alternatives was endorsed (that is, from 1 to 5), except for items 7 (good mood) and 10 (apathy), for which the range was 2–5.

Background information

Families were asked to answer questions about their socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and other demographic information.

Statistical analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis

To test the five-dimensional factor structure of the KIDSCREEN-27, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA), in the following steps: first, we tested each of the five dimensions of HRQoL in five separate CFAs to investigate each dimension’s internal structure. Next, we tested a unidimensional model, with all 27 items loading on one single factor, HRQoL. Finally, we compared the unidimensional CFA to the theoretical five-factor CFA with Chi-square difference test of nested models. The models’ fit indices were contrasted, including Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and root-mean-square-error of approximation (RMSEA). For these analyses, we used Mplus software [51].

Comparisons of levels of HRQoL

Comparisons of levels of HRQoL were analyzed by using the SPSS Version 22. All scores were standardized according to the KIDSCREEN manual and t-scores were used for each of the five dimensions [48]. For the overall sample, t-scores with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 were used. For analysis on gender and age, we used gender- and age-specific mean values derived from data of the reference population. Both gender and age were analyzed as categorical variables. Based on categorizations used in the reference population [48], age was categorized into ‘younger children’ (8–11 years) and ‘adolescents’ (12–17 years). T-tests were used to test gender- and age differences in the total sample, and for comparisons of mean t-scores with the reference population. One-way ANOVA (with ad hoc Scheffe’ test) was used to explore potential differences in the children’s HRQoL scores between the three parental patient groups.

Results

Descriptive statistics, reliabilities, and variable normality for the total scale and for each dimension of HRQoL are presented in Table 2. All scales showed good psychometric and distributional qualities. Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations between each item of the KIDSCREEN are presented in Table 3. There were no floor effects on any of the five dimensions (< 2% for each of the dimensions scored the lowest possible score). Ceiling effects were found for the Peers and social support dimension, in which 20.7% of the sample scored the highest possible score. For the remaining dimensions, the highest score was observed in less than 13% of the sample.

Dimensional confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs)

Each dimension of HRQoL was first tested in five separate CFAs to investigate their internal structures. Each CFA showed good to excellent fit to the data, according to fit indices, significant factor loadings, inter-item correlations, and variance explained in the indicators. The error variances of select items were correlated when such dependency made substantive and statistical sense. For example, for the autonomy and parent relation dimension, the error variances of ‘being able to have time to one-self’ and ‘having free time’ were correlated.

Unidimensional confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

We then tested a unidimensional model, in which all the 27 items loaded on a single factor: HRQoL. In the first test of the model, no error variances were correlated. The model showed an inadequate fit to the data: χ2 (324) = 1437.64, p < 0.001, RMSEA = .12 (90% CI 0.11–0.12), and CFI = .70. We then ran the same unidimensional model entering the same correlated error variances as in the separately run dimensional CFAs. As these models are nested, we performed a Chi-square test of significance. The model with correlated error variances significantly improved the fit of the model with a difference of 9 degrees of freedom: χ2 (315) = 1118.24, p < 0.001, RMSEA = .10 (90% confidence interval CI 0.10–0.11), and CFI = .78.

Comparing the unidimensional model with the five-factor model

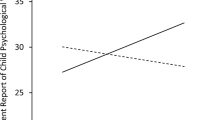

Finally, we compared the unidimensional model allowing for correlated error variances with the theoretical five-dimensional model with the same error variances correlations. These models were also nested. The five-factor model fit the data significantly better than the unidimensional model. The final five-factor model with some added error variance correlations fit the data reasonably well and χ2 (302) = 441.57, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.04 (90% confidence interval CI 0.03–0.05), and CFI = 0.96. An RMSEA value between 0.00 and 0.05 has been suggested as an indication of good fit, whereas a CFI value between .95 and .97 has denoted acceptable fit [52]. These results indicate that the KIDSCREEN-27 consists of five separate and related factors and thus replicated its theoretical factor structure in this sample. Figure 1 shows the final model.

Age, gender, and type of parental illness

Table 4 shows how children in our sample rated their level of HRQoL, in terms of standardized mean t-scores, across the five dimensions of well-being according to the children’s gender, age group, and type of parental illness. Boys reported significantly higher levels of physical well-being (p < 0.01), psychological well-being (p < 0.01), and peers and social support (p < 0.05), compared to the girls.

Younger children (8–11 years) reported higher levels of physical well-being (p < 0.02), psychological well-being (p < 0.01), peers and social support (p < 0.02), and well-being at school (p < 0.02), compared to adolescents (12–17 years). Contrary to expectations, no significant differences in HRQoL scores emerged between children of physically ill parents and children of mentally ill and substance abusing parents on any of the five dimensions of the KIDSCREEN-27.

Scores compared to reference population

When compared to the reference population [48], we found that both younger children and adolescents in our sample reported significantly lower physical well-being (p < 0.01) compared to the reference population (see Table 4). Moreover, the girls in our sample reported significantly lower physical well-being (p < 0.01), while the boys reported significantly higher scores on peers and social support (p < 0.03) and school well-being (p < 0.02) compared to the gender specific means in the reference population.

When exploring children’s HRQoL scores according to type of parental illness, we found that in our sample, children of physically and mentally ill parents, but not of substance abusing parents, reported significantly lower physical well-being (p < 0.01 and p < 0.01, respectively) compared to the reference population. This may, however, be due to power issues.

Discussion

The objectives of this investigation were to test whether the theoretical factor structure of KIDSCREEN-27 was replicated in a Norwegian sample of children whose parents had a physical, mental, or substance abuse illness and to examine whether there were differences in scores based on gender, age-level, or type of parental illness. Further, we wanted to compare the HRQoL scores of the children in our sample to those from a normative reference population.

The results indicated that the conceptual five-factor model fit the data well and better than the unidimensional model. Thus, our results suggest that KIDSCREEN-27 measures the same constructs in children and adolescents with parental illness and substance abuse as it does in a population-based European sample. Moreover, our findings further support KIDSCREEN-27 to be conceptualized as consisting of five related, albeit separate constructs.

Boys rated their physical-, and psychological well-being, as well as their relation to peers and social support, higher than did girls. This is in line with results from other studies on HRQoL among children [21, 25, 31,32,33, 35]. It has been reported that gender differences in HRQoL tend to emerge around the ages of 11–14 years, and that the greater decreases in HRQoL with age reported among girls may be associated with age-specific challenges such as menarche [26, 35] or a tendency for girls to report more depressive symptoms around this age is [53, 54]. This may have a substantial impact on how girls rate their QoL at this developmental period.

When exploring age-group differences in our sample, we found that the younger children (8–11) reported significantly higher physical- and psychological well-being, as well as better relations with peers and social support, and greater well-being in school compared to the adolescents (aged 12–17). This is also in line with findings from earlier studies on age differences in HRQoL [21, 25, 31,32,33, 35, 36]. Regarding age differences, it has been suggested that these differences may reflect a delayed comprehension of the potential consequences that parental illness may represent [31]. Except for well-being in terms of autonomy and parent relations, it appears that the gender and age differences reported among other populations of children are also evident among children and adolescents living with an ill or substance abusing parent. It is important to note that while these age and gender difference were significant, they were in the small to medium range in terms of effect sizes (Cohen’s d).

Our hypothesis that children of physically ill parents would report greater HRQoL scores than children of mentally ill- or substance abusing parents was not supported. No significant differences between children of the different the parental patient groups were found, except that the level of physical well-being was significantly lower for children of physically mentally ill parents, but not of substance abusing parents, compared to the reference population. A possible reason for this lack of significant differences between the groups may be participation bias. Although most parents were positive to participation in our study, we experienced that the more severely ill parents were less likely to agree to participate. For some of these parents, choosing not to participate in the study was related to their functioning—they were too strained to be able to participate. For others, the reasons may have been a hesitation of giving information about their health and family functioning, and how their condition affected the child, especially among the substance abusing parents, who are more often under the supervision of child protection services. Hence, our sample may have suffered from less representation of the more severely ill and/or substance abusing parents, leaving us with less variation and thereby a lower likelihood of detecting differences between the patient groups. Moreover, the children in the parental substance abuse group was small (n = 30), which reduced power to detect significant differences.

When compared to the reference population, we found that the children in our sample in general reported significantly lower physical well-being (Cohens’ d = .4). Although considerable research has been conducted on associations between mental health and physical complaints, these studies are dominated by adult samples, and less is known about links between physical and mental health and quality of life in children. Our results are nevertheless similar to what has been reported among adolescents living in youth care homes provided by the child welfare system. In these at-risk populations, adolescents often report poorer physical well-being compared to a normative or low-risk population [55]. It appears that indicators of physical well-being are important to consider in future studies of populations at risk and especially as it relates to HRQoL. Children’s psychological problems may often be manifested by somatic complaints such as headaches, stomachaches, and fatigue.

Strengths and limitations of the current study

A strength of this study is that our sample included children of parents with different types of parental illness. Moreover, children and families were recruited from five major health authorities in Norway, which combined serves about 1/3 of the Norwegian population. The use of the KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire allowed for comparison with normative and international samples cross Europe. Finally, our data collection strategy ensured no missing data at the individual level, though at the family level, data were missing for parents of eight children.

As is the case with any factor analysis, support for a factor structure does not necessarily mean that it is the best fitting or only model that fits the data for a given population, in this case children of ill or substance abusing parents. A competing model, not yet identified, may prove to fit the data even better. Testing model modifications in future studies would help expand the knowledge base concerning HRQoL in children of ill or substance abusing parents. It is worth noting that in a preliminary model testing, we ran the HRQoL data in an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) framework. In the EFA, the five theoretical factors were extracted and while all items loaded quite strongly on their respective and theoretically appropriate factors, 7 of the 27 items cross-loaded on other factors. While these cross-loadings were rather small, it may nevertheless suggest that there may be superfluous items or that adding a dimension could capture these items better. We ran an additional CFA in which we excluded these seven items. The model fit results indicated very good fit to the data: χ2 (153) = 177.01, p = 0.09, RMSEA = .03 (90% CI 0.00–0.04), and CFI = .99. Future investigation of HRQoL in general and KIDSCREEN in particular for this population of children may shed further light on this issue.

Although our sample size was of adequate size when it comes to research on children of ill or substance abusing parents, it was nevertheless deemed too small to test for invariance in factor structure across sub-groups, for example, across gender or age groups. Moreover, while we found gender and age differences in mean levels on several HRQoL sub-dimensions, we believe that the factor structure of HRQoL is similar for boys and girls and younger and older children. Future studies with larger samples will be able to confirm this assumption. Future studies may also investigate whether HRQoL is indeed a precursor to later psychosocial maladjustment given longitudinal designs. And as our results suggest particular consideration should be awarded the role of physical well-being in determining children’s overall quality of life and in assessing risk.

References

Barkmann, C., Romer, G., Watson, M., Schulte-Markwort, M. (2007). Parental physical illness as a risk for psychosocial maladjustment in children and adolescents: Epidemiological findings from a national survey in Germany. Psychosomatics: Journal of Consultation Liaison Psychiatry, 48, 476–481.

Berg-Nielsen, T. S., & Wichstrom, L. (2012). The mental health of preschoolers in a Norwegian population-based study when their parents have symptoms of borderline, antisocial, and narcissistic personality disorders: At the mercy of unpredictability. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6, 19.

Bogosian, A., Moss-Morris, R., & Hadwin, J. (2010). Psychosocial adjustment in children and adolescents with a parent with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation, 24, 789–801.

Christoffersen, M. N., & Soothill, K. (2003). The long-term consequences of parental alcohol abuse: A cohort study of children in Denmark. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 25, 107–116.

Connell, A. M., & Goodman, S. H. (2002). The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 746–773.

Diareme, S., Tsiantis, J., Kolaitis, G., Ferentinos, S., Tsalamanios, E., Paliokosta, E., et al. (2006). Emotional and behavioural difficulties in children of parents with multiple sclerosis: A controlled study in Greece. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 15, 309–318.

Evans, S., Keenan, T. R., & Shipton, E. A. (2007). Psychosocial adjustment and physical health of children living with maternal chronic pain. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 43, 262–270.

Jeppesen, E., Bjelland, I., Fossa, S. D., Loge, J. H., Sorebo, O., & Dahl, A. A. (2014). Does a parental history of cancer moderate the associations between impaired health status in parents and psychosocial problems in teenagers: A HUNT study. Cancer Medicine, 3, 919–926.

Kelley, M. L., & Fals-Stewart, W. (2004). Psychiatric disorders of children living with drug-abusing, alcohol-abusing, and non-substance-abusing fathers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 621–628.

Krattenmacher, T., Kuhne, F., Halverscheid, S., Wiegand-Grefe, S., Bergelt, C., Romer, G., et al. (2014). A comparison of the emotional and behavioral problems of children of patients with cancer or a mental disorder and their association with parental quality of life. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 76, 213–220.

Osborne, C., & Berger, L. M. (2009). Parental substance abuse and child well-being: A consideration of parents’ gender and coresidence. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 341–370.

Ramchandani, P., & Psychogiou, L. (2009). Paternal psychiatric disorders and children’s psychosocial development. The Lancet, 374, 646–653.

Razaz, N., Nourian, R., Marrie, R. A., Boyce, W. T., & Tremlett, H. (2014). Children and adolescents adjustment to parental multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. BMC Neurology, 14, 107.

Sieh, D., Meijer, A., Oort, F., Visser-Meily, J., & Van der Leij, D. (2010). Problem behavior in children of chronically ill parents: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13, 384–397.

Visser, A., Huizinga, G. A., Hoekstra, H. J., Van Der Graaf, W. T., Klip, E. C., Pras, E., et al. (2005). Emotional and behavioural functioning of children of a parent diagnosed with cancer: A cross-informant perspective. Psychooncology, 14, 746–758.

The KIDSCREEN Group Europe. (2006). The KIDSCREEN Questionnaires—Quality of life questionnaires for children and adolescents. Handbook. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

Coker, T. R., Elliott, M. N., Wallander, J. L., Cuccaro, P., Grunbaum, J. A., Corona, R., et al. (2011). Association of family stressful life-change events and health-related quality of life in fifth-grade children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 165, 354–359.

Krattenmacher, T., Kuhne, F., Ernst, J., Bergelt, C., Romer, G., & Moller, B. (2012). Parental cancer: Factors associated with children’s psychosocial adjustment-A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 72, 344–356.

Mayo, N. E. (2015). Dictionary of Quality of Life and Health Outcomes Measurement. 1st ed. International Society for Quality of Life Research, 3.

Bot, M., de Leeuw den Bouter, B., & Adriaanse, M. (2011). Prevalence of psychosocial problems in Dutch children aged 8–12 years and its association with risk factors and quality of life. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 20, 357–365.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Auquier, P., Erhart, M., Gosch, A., Rajmil, L., Bruil, J., et al. (2007). The KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: Psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European countries. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 16, 1347–1356.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Gosch, A., & Wille, N. (2008). Mental health of children and adolescents in 12 European countries—Results from the European KIDSCREEN Study. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 15, 154–163.

Wallander, J. L., & Koot, H. M. (2016). Quality of life in children: A critical examination of concepts, approaches, issues, and future directions. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 131–143.

Sun, R. C. F., & Shek, D. T. L. (2013). Longitudinal influences of positive youth development and life satisfaction on problem behaviour among adolescents in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality-of-Life Measurement, 114(3), 1171–1197.

Berra, S., Tebe, C., Esandi, M. E., & Carignano, C. (2013). Reliability and validity of the KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in the 8 to 18 year-old Argentinean population. Archivos Argentinos de Pediatria, 111, 29–35.

Palacio-Vieira, J., Villalonga-Olives, E., Valderas, J., Espallargues, M., Herdman, M., Berra, S., et al. (2008). Changes in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in a population-based sample of children and adolescents after 3 years of follow-up. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 17, 1207–1215.

World Health Organization. Health statistics and information systems; WHOQOL: Measuring quality of life. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqol-qualityoflife/en/.

Wallander, J. L., Schmitt, M., & Koot, H. M. (2001). Quality of life measurement in children and adolescents: Issues, instruments, and applications. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57, 571–585.

Detmar, S., Bruil, J., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Gosch, A., & Bisegger, C. (2006). The use of focus groups in the development of the KIDSCREEN HRQL questionnaire. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 15, 1345–1353.

Robitail, S., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Simeoni, M.-C., Rajmil, L., Bruil, J., Power, M., et al. (2007). Testing the structural and cross-cultural validity of the KIDSCREEN-27 Quality of Life Questionnaire. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 16, 1335–1345.

Gotze, H., Ernst, J., Brahler, E., Romer, G., & von Klitzing, K. (2015). Predictors of quality of life of cancer patients, their children, and partners. Psychooncology, 24, 787–795.

Giannakopoulos, G., Dimitrakaki, C., Pedeli, X., Kolaitis, G., Rotsika, V., Ravens-Sieberer, U., et al. (2009). Adolescents’ wellbeing and functioning: relationships with parents’ subjective general physical and mental health. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7, 100.

Cavallo, F., Zambon, A., Borraccino, A., Raven-Sieberer, U., Torsheim, T., & Lemma, P. (2006). Girls growing through adolescence have a higher risk of poor health. Quality of Life Research, 15, 1577–1585.

Meade, T., & Dowswell, E. (2015). Health-related quality of life in a sample of Australian adolescents: Gender and age comparison. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1033-4.

Michel, G., Bisegger, C., Fuhr, D. C., & Abel, T. (2009). Age and gender differences in health-related quality of life of children and adolescents in Europe: A multilevel analysis. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 18, 1147–1157.

Bisegger, C., Cloetta, B., von Rueden, U., Abel, T., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2005). Health-related quality of life: gender differences in childhood and adolescence. Soz Praventivmed, 50, 281–291.

Kuhne, F., Krattenmacher, T., Bergelt, C., Ernst, J. C., Flechtner, H. H., Fuhrer, D., et al. (2012). Parental palliative cancer: Psychosocial adjustment and health-related quality of life in adolescents participating in a German family counselling service. BMC Palliative Care, 11, 21.

Morley, D., Selai, C., Schrag, A., Jahanshahi, M., & Thompson, A. (2011). Adolescent and adult children of parents with Parkinson’s Disease: Incorporating their needs in clinical guidelines. Parkinson’s Disease. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/951874.

Dittrich, K., Fuchs, A., Bermpohl, F., Meyer, J., Führer, D., Reichl, C., et al. (2018). Effects of maternal history of depression and early life maltreatment on children’s health-related quality of life. Journal of Affect Disordorders, 1, 280–288.

Comiskey, C. M., Milnes, J., & Daly, M. (2017). Parents who use drugs: The well-being of parent and child dyads among people receiving harm reduction interventions for opiate use. Journal of Substance Use, 22, 206–210

Dam, K., & Hall, E. O. (2016). Navigating in an unpredictable daily life: A metasynthesis on children’s experiences living with a parent with severe mental illness. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12285.

Tebes, J., Kaufman, J., Adnopoz, J., & Racusin, G. (2001). Resilience and family psychosocial processes among children of parents with serious mental disorders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 10(1), 115–136.

Berg-Nielsen, T. S., Vikan, A., & Dahl, A. A. (2002). Parenting related to child and parental psychopathology: A descriptive review of the literature. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7, 529–552.

Johnson, J. G., Cohen, P., Kasen, S., Ehrensaft, M. K., & Crawford, T. N. (2006). Associations of parental personality disorders and axis I disorders with childrearing behavior. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 69, 336–350.

Laulik, S., Chou, S., Browne, K. D., & Allam, J. (2013). The link between personality disorder and parenting behaviors: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18, 644–655.

Stein, A., Ramchandani, P., Murray, L. (2008). Impact of parental psychiatric disorder and physical illness. In M. Rutter, D. Bishop, D. Pine, S. Scott, J. Stevenson, E. Taylor, & A. Thapar (Eds.), Rutter’s child and adolescent psychiatry (5th ed., pp 407–420) xv, 1230 pp. London: Wiley. (Reprinted 2010).

Lander, L., Howsare, J., & Byrne, M. (2013). The impact of substance use disorders on families and children: From theory to practice. Social Work in Public Health, 28, 194–205.

Europe, T. K. G. (2006). The KIDSCREEN questionnaires: Quality of life questionnaires for children and adolescents. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

Ruud, T. B. B., Faugli, A., Amlund Hagen, K., Hellmann, A., Hilsen, M., Kallander, E. K., et al. (2015). Barn som pårørende—-Resultater fra en multisenterstudie. Lørenskog: Akershus universitetssykehus HF.

Andersen, J. R., Natvig, G. K., Haraldstad, K., Skrede, T., Aadland, E., & Resaland, G. K. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the Kidscreen-27 questionnaire. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 14, 58.

Munthén, L. K. (1998–2015). MBO: Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh edition. Los Angeles, CA: Munthén & Munthén.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit Measures. Methods of psychological research online, 8, 23–74.

Ogden, T., & Hagen, K. A. (2014). Adolescent mental health: Prevention and intervention. New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

Benjet, C., & Hernandez-Guzman, L. (2001). Gender differences in psychological well-being of Mexican early adolescents. Adolescence, 36, 47–65.

Kayed, N. S., Jozefiak, T., Rimehaug, T., Tjelflaat, T., Brubakk, A. M., & Wickstrom, L. (2015). Resultater fra forskningsprosjektet psykisk helse hos barn og unge i barnevernsinstitusjoner. Trondheim: Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Funding

This study was funded by the Research Council of Norway (ID: 213477).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Regional Committee on Medical and Health Research Ethics, South-East (ID: 2012/1176).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hagen, K.A., Hilsen, M., Kallander, E.K. et al. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in children of ill or substance abusing parents: examining factor structure and sub-group differences. Qual Life Res 28, 1063–1073 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2067-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2067-1