Abstract

Purpose

To analyse the clinical, sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors that influence perceived quality of life (QoL) in a community sample of 33,241 people aged 65+ and to examine the relationship with models of social welfare in Europe.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of data from Wave 5 (2013) of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). The instruments used in the present study were as follows: sociodemographic data, CASP-12 (QoL), EURO-D (depression), indicators of life expectancy and suicide (WHO), and economic indicators (World Bank). Statistical analysis included bivariate and multilevel analyses.

Results

In the multilevel analysis, greater satisfaction in life, less depression, sufficient income, better subjective health, physical activity, an absence of functional impairment, younger age and participation in activities were associated with better QoL in all countries. More education was only associated with higher QoL in Eastern European and Mediterranean countries, and only in the latter was caring for grandchildren also related to better QoL. Socioeconomic indicators were better and QoL scores higher (mean = 38.5 ± 5.8) in countries that had a social democratic (Nordic cluster) or corporatist model (Continental cluster) of social welfare, as compared to Eastern European and Mediterranean countries, which were characterized by poorer socioeconomic conditions, more limited social welfare provision and lower QoL scores (mean = 33.5 ± 6.4).

Conclusions

Perceived quality-of-life scores are consistent with the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants, as well as with the socioeconomic indicators and models of social welfare of the countries in which they live.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In its project to develop an instrument for measuring quality of life (QoL), the World Health Organization [1] defined QoL as an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. Thus, QoL is a multidimensional concept that encapsulates physical health, psychological well-being, level of independence, social relationships, relationship to one’s environment and personal beliefs. Given this complexity, it is worthwhile examining the factors that may influence QoL in older people.

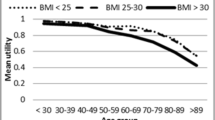

Research in this field has found that older age is associated with a reduction in QoL, which appears to peak at 67 years, falling thereafter [2]. The most important factors reported to be associated with this decrease in QoL are health related, including functional impairment and depression, as well as lifetime cumulative adversity [3].

Studies of health status and its relationship to QoL indicate that the presence of illness [4, 5] and limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) [6, 7] are associated with poorer QoL. Mental health problems, especially depression, also have a negative effect on QoL [2, 6, 8], and they often coincide with physical illness and/or widowhood in persons aged 65+ [9].

Socioeconomic status, level of education and income have also been studied for their relationship to QoL, with similar findings being reported. Specifically, more education and a higher income have consistently been associated with better perceived QoL [6, 10].

Participation in socially productive activities, such as volunteering or informal care [11], as well as leisure pursuits [12], has likewise been found to be related to better QoL. Other activities associated with improved well-being and QoL are caring for grandchildren [13] and physical exercise [14].

However, some authors have suggested that levels of QoL depend not only on individual factors, but also on the welfare provision of the country in which the person lives [15], as well as on socioeconomic inequalities [16]. In this respect, Eastern European and Mediterranean countries are characterized by more limited social welfare and greater socioeconomic inequalities, and consequently lower QoL, than is the case in countries of Northern and Central Europe [17].

Models of social welfare in Europe have been classified according to criteria such as the degree of benefit coverage, the amount of compensation paid in the event of unemployment and the nature of employment policies [18, 19]. The social democratic regime (found in Nordic countries and The Netherlands) is characterized by high levels of social protection, universal welfare provision and active employment policies. The corporatist regime (countries such as Austria, Germany and Switzerland) places less emphasis on redistribution, and entitlements depend on the individual’s employment history and/or contributions to voluntary insurance schemes; benefit coverage is thus more limited than that in the Nordic model. The Southern European regime (Mediterranean countries) relies heavily on family support systems, with poorly developed labour market policies and a benefits system that is uneven and limited. Finally, the post-socialist regime (Eastern European countries) is characterized by low levels of spending on social protection and weakness of social rights, although there are differences across countries: the Czech Republic and Slovenia are closer to the corporatist model, whereas the system in Estonia more closely resembles the liberal regime found in the UK.

With respect to QoL measures and other indicators such as life expectancy or suicide rates, a paradox emerges. Although Mediterranean countries (Spain and Italy) have lower levels of QoL [17], their populations have greater life expectancy and greater healthy life expectancy [20], as well as lower rates of suicide [21].

The aims of this study were as follows: (1) to investigate the relationship between QoL and clinical, sociodemographic and socioeconomic variables in a community sample of European people aged 65+; (2) to analyse the distribution of these variables and of QoL across a range of countries grouped according to their model of social welfare; and (3) to compare QoL scores for this sample with life expectancy and suicide rates in the countries considered.

Methods

Design and study population

This was a cross-sectional study of a community sample of people aged 65+ using available data from Wave 5 (2013) of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). This survey provides information about sociodemographic characteristics, physical and mental health status, quality of life, socioeconomic status and activities in older persons from 14 European countries plus Israel [22].

Instruments

The SHARE data, variables and instruments used for the present study were as follows:

-

Sociodemographic data Age, gender, marital status and years of education.

-

Socioeconomic data Employment status, income, difficulties making ends meet and the receipt of pensions.

-

Physical exercise and activities Frequency of physical exercise, participation in activities and grandparenting.

-

Physical health Subjective health status, chronic diseases and limitations in ADL.

-

Depressive symptoms Data here are based on the EURO-D, a 12-item scale whose cut-off for depression is a score ≥4. Items require a yes/no response and the total score ranges from 0 to 12; the higher the score, the more symptoms of depression are present. Cronbach’s alpha is reported to be in the range 0.61–0.75 [23].

-

Quality of life (QoL) The CASP-12v.1 is a short version of the original scale (CASP-19) and was developed specifically for SHARE [24]. Each of its 12 items is answered using a four-point Likert-type scale, and the total score, which ranges between 12 and 48, is interpreted as follows: low QoL, <35; moderate, 35–37; high, 37–39; and very high, ≥39. Cronbach’s alpha is reported to be in the range 0.74–0.79 [17].

We also consulted WHO data on life expectancy and suicide rates, as well as socioeconomic data published by the World Bank.

-

Life expectancy (LE) and healthy life expectancy (HALE) at birth. WHO data from 2013 on life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at birth [25].

-

Suicide rate. The most recent available WHO data (corresponding to 2012) on suicide rates [21], using crude rates for the age groups 50–69 and ≥70 years.

-

Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita based on purchasing power parity (PPP). Data from the World Bank for the year 2013 [26].

Statistical analysis

We carried out a descriptive analysis of clinical, sociodemographic and socioeconomic data for the sample, using measures of central trend and dispersion for quantitative variables and absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables.

The influence of each independent variable on QoL (CASP-12) was analysed using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Student’s t test and F ANOVA for continuous variables. Effect sizes were calculated to assess the relevance of any significant (p) differences. For the difference between two means, we used Cohen’s d, whose values were interpreted as follows: <0.5, small effect; 0.5–0.8, medium effect; and >0.8, large effect. Differences between several means were examined by calculating eta-squared (η 2 ), indicating a small (<0.06), medium (0.06–0.13) or large effect (>0.14) [27]. In order to assess the magnitude of the effect between proportions, we calculated Cramer’s V, whose values depend on the degrees of freedom: V 1 = small (<0.30), medium (0.30–0.49) or large effect (≥0.50); V 2 = small (<0.20), medium (0.21–0.34) or large effect (≥0.35); and V 3 = small (<0.17), medium (0.17–0.28) or large effect (≥0.29) [28].

We identified the factors that most influenced QoL in each of the 15 countries considered for this sample, with countries being grouped according to the regional clusters defined in a 2013 report by the European Commission [29], each of which corresponds to a particular model of social welfare [18, 19]: social democratic regime/Nordic cluster (Denmark and Sweden plus The Netherlands); corporatist regime/Continental cluster (Switzerland, Luxembourg, Austria, Germany, Belgium and France); post-socialist regime/Eastern cluster (Slovenia, Czech Republic and Estonia); and Southern European regime/Mediterranean cluster (Spain, Italy and Israel).

A multilevel analysis [30] was conducted to assess the effect of the different variables on QoL (CASP-12), with three models being fitted: a null model (with no independent variables), a model for the 15 countries as a whole and a model based on four country clusters. For each model, we calculated the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) as a measure of variability in QoL.

For all analyses, we used weighted data, based on the weights provided by SHARE, as this corrects for the unequal selection probabilities of the population parameters [22].

The level of significance for comparisons was p < 0.05, and the statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v22.0 for (SPSS Inc., Chicago).

Results

Description of the sample

The total sample comprised 33,241 people aged 65+ from 14 European countries plus Israel. Their mean age was 74.7 ± 7.1 years, and 56.9 % were women. Regarding their marital status, 62.8 % were married and 24.4 % were widowed. More than eight years of formal education was reported by 58.2 % of the sample.

In terms of socioeconomic data, the majority of people were retired (85.5 %) and in receipt of a retirement pension (83.6 %). Around two-thirds (67.5 %) said they had no problems making ends meet.

Physical exercise was taken by 44.1 % of the sample, and 79.6 % reported participation in some kind of leisure activity, either individual and/or social. More than half (54.2 %) felt they were in good health and 80.7 % said they experienced no limitations in ADL, although 74.3 % reported one or more chronic disease. The rate of depression (score ≥4 on the Euro-D) was 30.7 %.

Quality of life overall was moderate (mean = 36.7 ± 6.5), with fairly high levels of life satisfaction (mean = 7.5 ± 1.8). Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic, socioeconomic and clinical data for the sample as a whole.

Quality of life and sociodemographic, socioeconomic and clinical factors

Table 2 shows data from the bivariate analysis examining the influence of clinical and sociodemographic factors on QoL. The main text also includes additional analyses concerning the key variables that were associated with the subgroups (different levels) of each factor.

With respect to age, the effect size for differences in QoL scores across age groups was small (η 2 = 0.04). However, the oldest group (≥80 years) scored lowest on QoL. The main factors that distinguished these older individuals from those in the youngest group (65–69 years) were more depression (≥4 Euro-D = 42.3 vs. 23.6 %; V 1 = 0.20), poorer subjective health (fair and poor = 57.6 vs 33.7 %; V 1 = 0.24), income below the 50th percentile (65.2 vs. 37.3 %; V 1 = 0.27) and, with larger effect sizes, a higher rate of widowhood (46.9 vs. 10.6 %; V 1 = 0.40) and more limitations in ADL (>1 = 39.0 vs. 7.8 %; V 1 = 0.37).

Quality of life was somewhat lower among women (d = 0.20), with the main factors that distinguished them from men being more depression (≥4 Euro-D = 38.1 vs. 21.0 %; V 1 = 0.26) and a higher rate of widowhood (34.3 vs. 11.4 %; V 2 = 0.26).

Education had a moderate effect on QoL scores (η 2 = 0.11). The group with least education (0–5 years) scored lowest on QoL, and the main factors that distinguished this group from those with the highest level of education (>12 years) were more depression (≥4 Euro-D = 42.0 vs. 20.7 %; V 1 = 0.23), poorer subjective health (fair and poor = 59.5 vs. 31.8 %; V 1 = 0.27) and income below the 50th percentile (61.4 vs. 31.4 %; V 1 = 0.29).

Analysis of socioeconomic data revealed that lower QoL was associated with less income (M = 34.7 ± 6.9), not being in receipt of a pension (M = 33.9 ± 7.0) and, more notably, with difficulties making ends meet (M = 30.3 ± 6.5).

People who more frequently took physical exercise, those who participated in individual and social activities and those who cared for grandchildren all reported higher QoL.

The analysis showed that health is particularly relevant to perceived QoL. A higher number of chronic diseases (η 2 = 0.06), more limitations in ADL (η 2 = 0.16), more depression (d = 1.16) and poorer subjective health (η 2 = 0.26) were all associated with lower QoL, with effect sizes for the latter three variables being large.

Depression also had a notable impact on perceived QoL. The 30.7 % of the sample who scored ≥4 on the Euro-D (indicative of depression) obtained significantly lower scores on the CASP-12 (M = 31.9 ± 6.4), than did those individuals without depression (score <4 on Euro-D; CASP-12, M = 38.8 ± 5.4), the effect size being large (d = 1.16). Depression was also strongly associated with health indicators, it being more present among individuals with poorer subjective health (poor = 70.3 %, fair = 38.5 %, good = 18.7 %, very good = 10.8 %; V 3 = 0.40) and limitations in ADL (>2 = 72.5 %, 1 or 2 = 52.1 %, no = 23.5 %; V 2 = 0.32).

Table 2 presents the full data for QoL scores in relation to the different variables considered.

Quality of life and factors by country and by country clusters

Table 3 shows the means and frequencies by country and by country cluster for the most important factors, revealing a number of notable differences. The main text also includes data from the bivariate analyses examining differences between country clusters with respect to some of these key factors.

For QoL and the majority of indicators, the results became progressively less favourable across the following sequence of country clusters: Nordic, Continental, Eastern and Mediterranean. Differences in QoL showed a large effect size (η 2 = 0.14), with Mediterranean countries scoring lowest overall, below 35 on the CASP-12 (mean = 33.4 ± 6.5) (Fig. 1). Compared with the other three clusters, the Mediterranean countries also yielded the most negative results in terms of education (<8 years = 71.9 vs. 26.0 %; V 1 = 0.44), difficulties making ends meet (53.6 vs. 21.6 %; V 1 = 0.32), participation in fewer activities (44.1 vs 8.1 %; V 1 = 0.42) and not being in receipt of a pension (34.8 vs 7.0 %; V 1 = 0.35).

The most notable differences between country clusters were observed when comparing the Nordic and Continental with the Eastern and Mediterranean clusters, this being the case not only for QoL (mean = 38.5 ± 5.8 vs. 33.5 ± 6.4; d = 0.81), but also for education (>8 years = 73.5 vs. 33.4 %; V 1 = 0.39), difficulties making ends meet (20.2 vs. 52.6 %; V 1 = 0.33) and participation in activities (92.1 vs. 59.2 %; V 1 = 0.39). The data for per capita GDP were also more favourable for countries in the Nordic and Continental clusters.

Table 4 shows the effect sizes by country cluster for the influence on perceived QoL of each of the factors analysed. It can be seen that some factors had an effect on QoL across all four clusters, this being the case of difficulties making ends meet, physical exercise, participation in activities, subjective health, limitations in ADL, depression and satisfaction with life. Regarding the data for the Mediterranean cluster, it is worth noting that whereas older age, fewer years of education and less income had a negative impact on QoL, caring for grandchildren was, in this cluster, associated with higher QoL scores.

Multilevel analysis: quality of life and associated factors in four country clusters

In the null model (i.e. only QoL as the dependent variable, without factors), the estimated value of the intercept in the fixed effects was: coefficient = 37.59, SE = 0.70, t = 53.1, p < 0.001. The parameter estimates associated with the random effects were: variance in the factor Country: coefficient = 7.49, SE = 2.83; Wald z = 2.6, p = 0.008; and variance in the residuals: coefficient = 34.93, SE = 0.27, Wald z = 128.8, p < 0.001. According to these estimates, the between-country variability in QoL was 17 % (ICC = 0.17).

In the multilevel analysis that considered all 15 countries as a whole (Table 5), the reference level for each variable was the one associated with the highest QoL scores. The analysis showed that older age, male gender, difficulties making ends meet, less physical exercise, poorer subjective health, limitations in ADL, chronic disease and depression were associated with lower QoL; conversely, participation in more activities, caring for grandchildren and greater satisfaction with life were associated with better QoL.

The third model, which considered four country clusters, revealed a number of differences between them. Male gender was associated with lower QoL in the Nordic and Eastern clusters, while being divorced or separated was related to lower QoL in the Continental and Mediterranean clusters. More years of education only had a significant impact in the Eastern and Mediterranean clusters, where it was associated with better QoL. In terms of employment status, being retired was associated with lower QoL in the Eastern cluster, while being a homemaker was associated with lower QoL in both the Eastern and Mediterranean clusters. Less income was associated with lower QoL in the Nordic and Eastern clusters. Receipt of a pension was only associated with better QoL in the Eastern cluster, while caring for grandchildren was only associated with higher QoL in the Mediterranean cluster. Finally, chronic disease was associated with poorer QoL in both the Continental and Eastern clusters. The effect of all the remaining variables on QoL was similar across four clusters. The greatest variability was observed among countries in the Eastern cluster (19 %), with between-country variability being small (1–7 %) in the other three clusters.

Discussion

Physical and mental health

Health is one of the most important factors influencing perceived QoL. Poor subjective health, depression and limitations in ADL were clearly associated with lower QoL in this sample, with medium or large effect sizes in all countries. Various studies have highlighted the relationship between physical health and QoL [4, 17], with limitations in mobility and functional impairment [6, 7], chronic disease [5, 31] and depression [3] being consistently associated with poorer QoL.

The lower QoL scores observed among people aged 80+ have been linked to more impaired physical [3, 7] and mental health [2], as well as to higher rates of widowhood, associated with depression [9].

Active ageing

The present data lend support to the tenets of active ageing, since participation in a greater number of activities (social, clubs, courses, volunteering, etc.) was associated with better QoL, showing a medium effect size in all four country clusters. Various authors have previously documented the relationship between higher QoL and socially productive activities such as volunteering [11], caring for grandchildren [13] and leisure pursuits in general [12].

More regular physical exercise was also associated with better QoL, with a medium effect size in all four country clusters. This is consistent with previous research highlighting the benefits of physical exercise in terms of improved well-being and QoL [14].

Socioeconomic data

Our analysis indicated that education and income only influenced perceived QoL (with a medium effect size) in countries from the Eastern and Mediterranean clusters, whereas difficulties making ends meet had a strong effect in all four country clusters.

Less education and lower income have previously been linked to poorer QoL [6, 10]. More specifically, some authors have noted that the difference in quality of life by wealth and between the least and most educated is particularly wide in Eastern and Southern European countries, as compared to the narrower inequalities in quality of life that are found in countries that comprise the Nordic and Continental clusters considered here [16]. This is consistent with a conclusion reached by other authors, namely that QoL is related to welfare regimes [15]. In this respect, the lower QoL observed for countries in our Eastern and Mediterranean clusters would reflect the fact that their social welfare regimes are more limited than those of countries in the Nordic and Continental clusters.

Quality of life and models of social welfare in Europe

Countries in the Nordic cluster scored the highest on QoL and had the best personal and economic indicators [15–17]. These data are consistent with the social democratic welfare regime in these countries, offering high levels of social protection and universal provision. It should be noted, however, that despite a decrease in recent years these countries also had moderate rates of suicide, which was more common in rural areas and which has been linked to greater isolation [32] and alcohol abuse [33].

Countries in the Continental cluster had high levels of QoL associated with good socioeconomic indicators, although they were below those found in the Nordic cluster [15–17]. Countries with a corporatist regime have a long tradition of welfare provision, and a high proportion of their GDP are spent on social protection and old age benefits. Nonetheless, suicide rates were particularly high in Austria [35], Belgium and France [36].

Countries in the Eastern cluster scored low on QoL, with higher rates of depression and poorer socioeconomic indicators. In recent years, these countries have undergone enormous political and social changes, and their model of social welfare has shifted towards an insurance-based system similar to that found in countries in the Continental cluster, albeit with more limited coverage and continued high rates of poverty in rural areas [34]. In general, the former Eastern bloc countries showed lower levels of satisfaction with life, as well as the highest suicide rates [37].

The lowest QoL scores corresponded to countries in the Mediterranean cluster, which also showed higher rates of depression and low personal and socioeconomic indicators [15–17]. The welfare system (Southern regime) in these countries is characterized by low investment in social protection and a heavy reliance on the family and voluntary sector. The positive effect of caring for grandchildren on perceived QoL in these countries is consistent with the importance and value ascribed to family support. Interestingly, although these countries had the poorest QoL indicators in our analysis, data published by the WHO in 2013 indicated that they had the best life expectancy and healthy life expectancy [25], while WHO data published the following year showed that these countries had the lowest suicide rates in both the 50–69 years and 70+ age groups [21]. With respect to greater life expectancy, various authors have linked increased longevity to the Mediterranean diet [38], especially in terms of reduced cardiovascular disease, a major cause of preventable mortality [39]. As regards suicide, some authors claim that the strength of the family unit [34] in Southern European countries plays an important protective role against suicide, whereas others suggest that the Catholic religion, which predominates in Spain and Italy, is a factor associated with lower suicide rates [40].

Conclusions

In conclusion, certain factors, namely life satisfaction, physical and mental health, difficulties making ends meet, participation in activities and physical exercise, influenced QoL in all the countries considered. Socioeconomic indicators (GDP) and the social welfare regime also had an important effect, such that countries in the Nordic and Continental clusters had higher levels of QoL.

The lowest QoL scores corresponded to Eastern European and Mediterranean countries, which were characterized by poorer socioeconomic conditions. In countries of Southern Europe, however, there are other factors that appear to have an influence in terms of greater life expectancy (Mediterranean diet) and lower suicide rates (greater family support and religion).

Limitations

The most important limitation of this study has to do with the fact that SHARE data are based on self-reports. With respect to aspects such as limitations in ADL and physical and mental health, it would be useful to complement these subjective ratings with those of a third-party informant and to examine possible discrepancies.

Further studies are required to explore in greater depth the relationship between welfare regimes, life expectancy, suicide rates and perceived QoL.

References

World Health Organization. (1995). The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science Medicine, 4, 1403–1409.

Layte, R., Sexton, E., & Savva, G. (2013). Quality of life in older age: Evidence from an Irish cohort study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(S2), 99–305.

Shrira, A. (2014). Greater age-related decline in markers of physical, mental and cognitive health among Israeli older adults exposed to lifetime cumulative adversity. Aging and Mental Health, 18, 610–618.

Blane, D., Netuveli, G., & Montgomery, S. M. (2008). Quality of life, health and physiological status and change at older ages. Social Science and Medicine, 66, 1579–1587.

Wikman, A., Wardle, J., & Steptoe, A. (2011). Quality of life and affective well-being in middle-aged and older people with chronic medical illnesses: A cross-sectional population based study. Plos One, 6, e18952.

Netuveli, G., Wiggins, R. D., Hildon, Z., Montgomery, S. M., & Blane, D. (2006). Quality of life at older ages: Evidence from the english longitudinal study of aging (wave 1). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 357–363.

Palgi, Y., Shrira, A., & Zaslavsky, O. (2015). Quality of life attenuates age-related decline in functional status of older adults. Quality of Life Research, 24, 1835–1843.

Shrira, A. (2012). The effect of lifetime cumulative adversity on change and chronicity in depressive symptoms and quality of life in older adults. International Psychogeriatrics, 24, 1988–1997.

Schaan, B. (2013). Widowhood and depression among older Europeans—the role of gender, caregiving, marital quality, and regional context. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68, 431–442.

von dem Knesebeck, O., Wahrendorf, M., Hyde, M., & Siegrist, J. (2007). Socio-economic position and quality of life among older people in 10 European countries: Results of the SHARE study. Ageing and Society, 27, 269–284.

Siegrist, J., & Wahrendorf, M. (2009). Participation in socially productive activities and quality of life in early old age: Findings from SHARE. Journal of European Social Policy, 19, 317–326.

Nimrod, G., & Shrira, A. (2016). The paradox of leisure in later life. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 106–111.

Neuberger, F. S., & Haberkern, K. (2014). Structured ambivalence in grandchild care and the quality of life among European grandparents. European Journal of Ageing, 11, 171–181.

Khazaee-Pool, M., Sadeghi, R., Majlessi, F., & Rahimi Foroushani, A. (2015). Effects of physical exercise programme on happiness among older people. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22, 47–57.

Motel-Klingebiel, A., Romeu-Gordo, L., & Betzin, J. (2009). Welfare states and quality of later life: Distributions and predictions in a comparative perspective. European Journal of Ageing, 6, 67–78.

Niedzwiedz, C. L., Katikireddi, S. V., Pell, J. P., & Mitchell, R. (2014). Socioeconomic inequalities in the quality of life of older Europeans in different welfare regimes. European Journal of Public Health, 24, 364–370.

von dem Knesebeck, O., Hyde, M., Higgs, P., Kupfer, A., & Siegrist, J. (2005). Quality of life and Well-Being. In A. Börsch-Supan, A. Brugiavini, H. Jürges, J. Mackenbach, J. Siegrist, & G. Weber (Eds.), Health, ageing and retirement in Europe—first results from the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (pp. 199–203). Mannheim: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging (MEA).

Sapir, A. (2006). Globalisation and the reform of European social models. Journal of Common Market Studies, 44, 369–390.

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2010). Welfare regime and social class variation in poverty and economic vulnerability in Europe: An analysis of EU-SILC. Journal of European Social Policy, 20, 316–332.

Murray, C. J., Richards, M. A., Newton, J. N., Fenton, K. A., Anderson, H. R., Atkinson, C., et al. (2013). UK health performance: Findings of the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet, 381, 997–1020.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative (pp. 80–87). Geneva: WHO. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/131056/1/9789241564779_eng.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Malter, F., & Börsch-Supan, A. (Eds.). (2015). SHARE Wave 5: Innovations & methodology. Munich: Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy.

Prince, M. J., Reischies, F., Beekman, A. T. F., Fuhrer, R., Jonker, C., Kivela, S. L., et al. (1999). Development of the EURO-D scale—a European union initiative to compare symptoms of depression in 14 European centres. British Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 330–338.

Hyde, M., Wiggins, R. D., Higgs, P., & Blane, D. B. (2003). A measure of quality of life in early old age: the theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging and Mental Health, 7, 86–94.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2013). Life expectancy at birth and Healthy life expectancy at birth. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.688?lang=en. Accessed 25 Oct 2015.

The World Bank. (2013). GDP per capita, PPP (current international $). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?order=wbapi_data_value_2013+wbapi_data_value&sort=desc. Accessed 15 Dec 2015.

Cohen, J. (1973). Eta-squared and partial eta-squared in fixed factor ANOVA designs. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 33, 107–112.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

European Commission. (2013). Quality of life in Europe: Subjective well-being (pp. 5). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/es/publications/report/2013/quality-of-life-social-policies/quality-of-life-in-europe-subjective-well-being. Accessed 1 Dec 2015.

Pardo, A., Ruiz, M. A., & San Martín, R. (2007). Cómo ajustar e interpreter modelos multinivel con SPSS. Psicothema, 19, 308–321.

Sexton, E., King-Kallimanis, B. L., Layte, R., & Hickey, A. (2015). CASP-19 special section: how does chronic disease status affect CASP quality of life at older ages? Examining the WHO ICF disability domains as mediators of this relationship. Aging and Mental Health, 19, 622–633.

Titelman, D., Oskarsson, H., Wahlbeck, K., Nordentoft, M., Mehlum, L., Jiang, G.-X., et al. (2013). Suicide mortality trends in the Nordic countries 1980–2009. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 67, 414–423.

Morin, J., Wiktorsson, S., Marlow, T., Olesen, P. J., Skoog, I., & Waern, M. (2013). Alcohol use disorder in elderly suicide attempters: A comparison study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21, 196–203.

Wu, J., Värnik, A., Tooding, L. M., Värnik, P., & Kasearu, K. (2014). Suicide among older people in relation to their subjective and objective well-being in different European regions. European Journal of Ageing, 11, 131–140.

Watzka, C. (2012). Social conditions of suicides in Austria. An overview on risk and protective factors. Neuropsychiatrie, 26, 95–102.

Hooghe, M., & Vanhoutte, B. (2011). An ecological study of community-level correlates of suicide mortality rates in the Flemish region of Belgium, 1996–2005. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 41, 453–464.

Bray, I., & Gunnell, D. (2006). Suicide rates, life satisfaction and happiness as markers for population mental health. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41, 333–337.

Knoops, K. T., de Groot, L. C., Kromhout, D., Perrin, A. E., Moreiras-Varela, O., Menotti, A., et al. (2004). Mediterranean diet, lifestyle factors, and 10-year mortality in elderly European men and women: the HALE project. Journal of the American Medical Association, 292, 1433–1439.

Mathers, C. D., Stevens, G. A., Boerma, T., White, R. A., & Tobias, M. I. (2015). Causes of international increases in older age life expectancy. Lancet, 385, 540–548.

Spoerri, A., Zwahlen, M., Bopp, M., Gutzwiller, F., & Egger, M. (2010). Religion and assisted and non-assisted suicide in Switzerland: National Cohort Study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39, 1486–1494.

Acknowledgments

This paper uses data from SHARE Wave 5 release 1.0.0, as of March 31, 2015 (DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w5.100). The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through the 5th Framework Programme (project QLK6-CT-2001-00360 in the thematic programme Quality of Life), through the 6th Framework Programme (projects SHARE-I3, RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE, CIT5- CT-2005-028857, and SHARELIFE, CIT4-CT-2006-028812) and through the 7th Framework Programme (SHARE-PREP, N° 211909, SHARE-LEAP, N° 227822 and SHARE M4, N° 261982). Additional funding from the US National Institute on Aging (U01 AG09740-13S2, P01 AG005842, P01 AG08291, P30 AG12815, R21 AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG BSR06-11 and OGHA 04-064) and the German Ministry of Education and Research, as well as from various national sources, is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org for a full list of funding institutions). The authors would like to specifically acknowledge gratefully the Organisme de Salut Pública de la Diputació de Girona (Dipsalut) for the funding, and the Institut d’Assistència Sanitària de Girona (IAS) and the Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya (IDESCAT) for their collaboration.

Funding

The study received funding from European Commission 7th Framework Programme (SHARE M4, No 261982). Project: SHARE (Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Institut d’Assistència Sanitària de Girona, IAS) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All participants signed informed consent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Conde-Sala, J.L., Portellano-Ortiz, C., Calvó-Perxas, L. et al. Quality of life in people aged 65+ in Europe: associated factors and models of social welfare—analysis of data from the SHARE project (Wave 5). Qual Life Res 26, 1059–1070 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1436-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1436-x