Abstract

Purpose

Effectiveness of antidepressants is generally comparable between and within classes. However, real-world studies on antidepressant treatment and its consequences on the overall quality of life and mental health of individuals are limited. The purpose of this study was to examine the association of specific class of antidepressants with the health-related quality of life, psychological distress and self-reported mental health of individuals suffering from depression who are on monotherapy.

Methods

This retrospective, longitudinal study included individuals with depression who were on antidepressant monotherapy, using data from 2008 to 2011 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Changes in health-related quality of life, self-reported mental health and psychological distress over a year’s time were observed. A multinomial logistic regression model was built to examine the association between the class of antidepressant medications and the dependent variables.

Results

A total of 688 adults met the study inclusion criteria. No significant difference was observed in the change in Physical Component Summary (PCS), self-reported mental health and psychological distress based on the class of antidepressants. However, individuals on serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (OR 0.337, 95 % CI 0.155–0.730) were significantly less likely to show improvement on Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores as compared to those on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Conclusions

The study findings suggest that practitioners should be aware of the differences in the health-related quality of life of those taking SSRIs versus other classes of antidepressants. Further research needs to be done to determine the reason for SSRIs to show greater improvement on mental health as compared to SNRIs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression is a mental illness that can be both debilitating and costly to sufferers. It can adversely affect the course and outcome of common chronic conditions such as asthma, cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, arthritis and obesity [1]. It is associated with a decrease in functioning and well-being of an individual and an increase in the number of disability days, utilization of healthcare services and cost [2–4]. Approximately 1 in 10 adults in the USA is affected by depression, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [1]. The most common treatment option for depression is antidepressant medications [5]. There has been a substantial increase in the use of antidepressants over the years among individuals living with depression. It has been reported that during the last 20 years, the use of antidepressants has grown significantly, making them one of the most costly and the third most commonly prescribed class of medications in the USA [6].

Several different classes of antidepressants are available for treating depression. These include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). There are also other antidepressants that do not fall into any of these classes [7]. The effectiveness of antidepressants is generally comparable between and within classes. The selection of appropriate antidepressants is largely based on side effects, safety or tolerability for individual patients [8]. The SSRIs and other newer antidepressants (e.g., bupropion, nefazodone, trazodone and mirtazapine) have comparable clinical efficacy and fewer side effects in comparison with the tricyclic antidepressants and other older antidepressants [9–14]. A study by Simon et al. [15] suggests that patient and physician preferences are the most important factors in treatment decisions among patients with depression. However, the available data do not indicate whether SSRIs, which are the most frequently prescribed antidepressants, and the newer antidepressants show improved outcomes such as better quality of life, less psychological distress and better mental health status.

Individuals with depressive disorder tend to have worse physical and mental health, role functioning and perceived current health as compared to patients having no chronic conditions [2]. The significance of measuring the health-related quality of life for individuals with depression has greatly increased after the Medical Outcomes Study, wherein the social well-being and physical functioning of depressed patients were compared to those of patients with other chronic conditions [2]. This study showed that, as compared to other chronic medical conditions, depression has the greatest negative impact on a patients’ quality of life [2]. Hence, many researchers believe that it is valuable to evaluate any medical intervention or treatment to control any chronic medical condition such as depression in terms of its ability to improve the patients’ health-related quality of life [16].

While there is enough data available from clinical trials on the safety and efficacy of the various classes of antidepressants, there is a lack of information regarding their impact on the health-related quality of life and mental health in real-world settings. Furthermore, most participants in clinical trials are recruited by advertisement rather than from representative practices, and they are often selected to have few comorbid disorders, either medical or psychiatric [17, 18]. The goal for treatment of mental disorders is now shifting from mere remission from symptoms to complete recovery of the individual. Recovery from illness focuses on restoring the overall well-being of an individual. Therefore, there is a need for population-based studies that can further explore the relationship between the treatment options for depression and the overall mental and physical health of an individual. The primary objective of this study was to compare the improvement in the health-related quality of life, psychological distress and mental health of individuals suffering from depression who are on monotherapy (single antidepressant therapy) based on specific class of antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs, TCA and other antidepressants). As antidepressants are expected to relieve symptoms and consequently improve the overall quality of life and mental health of individuals, we hypothesized that the health-related quality of life and mental health scores will differ over a period of time, depending on the class of antidepressant medication used. Assessing the outcomes among patients on monotherapy was chosen as a stand-alone objective, as most patients with depression begin therapy with a single antidepressant and then resort to augmentation or combinations of medications if they experience partial or no remission [8].

Methods

Data source

This retrospective, longitudinal observational study was conducted using a 2-year longitudinal panel covering years 2008–2011 of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). MEPS is a large-scale, publicly available dataset that includes surveys of families from a nationally representative sample of the civilian, non-institutionalized US population and is sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS contains information on the medical health conditions, treatments, healthcare utilization, expenditures, sources of payment, health insurance coverage, respondents’ health status, demographics, socioeconomic characteristics and access to care. Information about each household member is collected using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) technology. Approximately 13,000 households and 35,000 individuals are surveyed each year. The panel design of the survey includes five rounds (rounds 1, 2, 3 4 and 5) of interviews covering two full calendar years, providing data for examining person-level changes in selected variables such as expenditures, health insurance coverage and health status. The MEPS sample is drawn from the households participating in the previous year’s National Health Interview Survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics [19]. This study was approved by The University of Toledo’s Biomedical Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

Study subjects

Individuals having depression were identified using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component (MEPS-HC) medical conditions file. This file contains information on observation of each self-reported medical conditions that a MEPS respondent experienced during the data collection year. The participants are asked to report the medical condition they experienced during the last 4–5 months since the previous interview in each round of interviews. Medical conditions reported by participants were recorded by interviewers as verbatim text and were coded by professional coders to fully specified three-digit International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes [20]. According to the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality, ICD-9-CM codes 296, 300 and 311 indicate depression [21] and were used to identify adults with depression.

Individuals taking antidepressants were identified using the Prescribed Medicines Files. The therapeutic sub-classification variable number 249 was used to identify antidepressants. Furthermore, the therapeutic sub–sub-classification variable was used to identify specific classes of antidepressants. For this study, the classes of antidepressants that were evaluated included SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs and other antidepressants (bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodone and nefazodone). Monoamine oxidase inhibitors were not evaluated as a separate class, as preliminary analysis found <5 individuals using this class of antidepressants. These individuals were excluded from the final data analysis.

Inclusion criteria

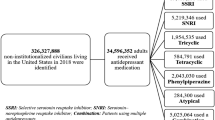

The analytical sample consisted of individuals aged 18 years or older who were identified with depression in the 2008–2011 MEPS database files and who were taking only one antidepressant medication. Of these, only those respondents who reported taking antidepressants since the beginning of the panel were included in the study. Those who reported using antidepressants for the first time in the third, fourth and fifth rounds of a panel were excluded. Respondents with missing responses on either of the questions assessing the health-related quality of life, psychological distress and perceived mental health status were also excluded (Fig. 1).

Dependent variable measures

Health-related quality of life

The health-related quality of life has been assessed in rounds 2 (time-point 1) and 4 (time-point 2) of each panel using the Short Form Health Survey-12 version two [22]. The instrument has two component summary scales, the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS). The scores on both scales range from 0 to 100, where a higher score is indicative of a better health-related quality of life [23]. The longitudinal data files in MEPS contain variables for both the PCS and the MCS scores of participants. In order to establish criteria to assess change in these scores, three categories were created: “improved,” “declined” and “unchanged.” If the difference in scores between time-point 2 and time-point 1 was >6, then the change in scores was defined as improved. Similarly, if the difference in scores between the two time-points was <6, it was defined as decline in scores, and if the difference was between ≥6 and ≤6, then the health-related quality of life was considered to be unchanged. We chose a six-point difference, because it represented half the standard deviation of difference in the health-related quality of life score in our study. Previous research suggests that a half standard deviation difference is considered a clinically significant change in the health-related quality of life of a patient [24].

Psychological distress

Psychological distress in MEPS is measured using the K6, a six-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale. The scores are based on six mental health-related questions that measure the individuals’ nervousness, hopelessness, sadness, restlessness, worthlessness and effortlessness in the past 30 days on a scale of 0–4, with 0 being none of the time and 4 being all the time. Summing the values on all these questions gives the overall K6 scores. The higher the K6 scores, the greater is the person’s tendency toward mental disability. The internal consistency and reliability of K6 scores is high (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89) [25]. The longitudinal data files in MEPS contain K6 scores, which are measured in rounds 2 (time-point 1) and 4 (time-point 2) of a panel and are roughly a year apart. In order to establish criteria to define change in scores in between round 2 (time-point 1) and round 4 (time-point 2), K6 scores were first categorized into no/low psychological distress, mild or moderate distress, and severe distress. We used previously reported cutoff points, as described in the literature, to stratify K6 scores into no/low (0–6), mild–moderate (7–12) and severe psychological distress (13–24) [25]. If an individual moved from a higher stress category in time-point 1 to a lower stress category in time-point 2, then the individual’s psychological distress was considered to be lower with time and was, therefore, defined as improved. Similarly, if an individual moved from a lower distress category in time-point 1 to a higher distress category in time-point 2, then the individual’s level of distress was considered to have worsened over time, and the change in psychological distress was defined as declined. Furthermore, if the distress categories remained the same in time-points 1 and 2, then the psychological distress was considered to remain unchanged over time.

Self-reported mental health

Perceived self-reported mental health was assessed using questions that asked the participant of MEPS-HC: “In general, compared with other people of the same age, would you say that your mental health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” It is scored on a Likert scale of 1–5, where 1 is excellent, 2 is very good, 3 is good, 4 is fair and 5 is poor. Change in categories between time-points 1 and 2 were assessed in the current study. We further classified the self-reported mental health into “very good” (if it was excellent or very good), “fair” (if it was good or fair) and “poor.” Similar to the above two outcome measures, if an individual moved from a lower mental health category in time-point 1 to higher mental health category in time-point 2, the mental health was considered to have improved over time, and vice versa. If the mental health categories remained the same over the two time-points, then their mental health was considered to have remained unchanged.

Covariates

Information on covariates, which included demographic factors, socioeconomic factors, health-related factors and resources available, was obtained from the MEPS longitudinal data files. In the present study, we controlled for demographic variables such as age, gender, race, ethnicity and marital status. Socioeconomic factors included education level, annual total person income, insurance type and employment status. Health-related factors included the number of coexisting chronic health conditions that a patient might have had with depression. Resources available included satisfaction with quality of care, access to healthcare and social support.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study sample according to their socio-demographic characteristics. The dependent variables, namely the change in health-related quality of life, psychological distress scores and self-reported mental health, were categorized into “improved,” “declined” and “unchanged.” A multinomial logistic regression model was built to determine the association of independent variables with the above-mentioned dependent variables. Demographic variables, socioeconomic factors, comorbidities and resources available were included as control variables. All analyses were performed after accounting for the complex survey design of MEPS using SAS software (version 9.3 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) with an a priori significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

A total of 688 individuals met the study criteria and were included in the data analysis. As shown in Table 1, assigning weights gave a number of 14,728,836, which represented a national cohort of individuals with depression who were on monotherapy. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. A vast majority of the study sample were females (N = 493, 72 %), whites (N = 422, 61 %) and non-Hispanics (N = 582, 85 %). Most of the individuals fell within the age category of 18–45 years (N = 316, 46 %). Individuals who were married (N = 314, 45 %), had low income (N = 364, 53 %) and had an education level of greater than high school (N = 309, 44 %) represented the majority of the sample. Most of the adults had private insurance (N = 391, 56 %) and had high satisfaction with health care (N = 569, 82 %). Furthermore, access to medical care was reported to be easy by a majority of the sample (N = 443, 65 %).

Of the 668 individuals on monotherapy, a majority of the individuals reported taking SSRIs to treat depression (N = 421). A minimal number of individuals were found to be taking TCAs to manage depression (N = 40). SNRIs were used by 109 individuals. Other antidepressants, which include bupropion, nefazodone, trazodone and mirtazapine, were prescribed to 118 individuals (Table 2).The percentage of patients showing improvement, decline and no change in scores in the second (time-period 1) and fourth rounds (time-period 2) of the panel are summarized in Table 2.

Table 3 shows multinomial logistic regression results for the PCS and MCS scores for individuals on monotherapy. Decline in these scores was treated as the reference category for comparison. Among antidepressants, the use of SSRIs was treated as the reference, as it was the most frequently prescribed antidepressant class. No significant differences were observed in the PCS scores among individuals on monotherapy based on the class of antidepressant used. Nonetheless, those on SNRIs were significantly less likely than those on SSRIs to show improvement on MCS scores as opposed to showing decline (OR 0.337, 95 % CI 0.155–0.730). However, no significant difference was observed in improvement on MCS scores between those on SSRIs, TCAs and other antidepressants. In addition, age, race, gender, type of insurance, income and number of comorbidities were found to be significant predictors of improvement in PCS scores. On the other hand, social activity, ethnicity and income were found to be significant predictors of change in MCS scores. Blacks were 2.2 times more likely to show improvement in PCS scores as compared to whites (95 % CI 1.006–5.007). Individuals who were older than 65 years of age were less likely to show improvement in PCS scores compared to individuals who were 18–45 years old (95 % CI 0.134–0.978). Also, females were 54 % less likely to show improvement in PCS scores compared to males (95 % CI 0.24–0.91). Those individuals having public insurance had three times higher odds of showing improved PCS scores when compared to those having private insurance (95 % CI 1.188–7.707). Individuals who responded that their health state “sometimes” and “none of the time” stopped their social activity were less likely to show improved MCS scores as compared to those who responded “all the time.” Non-Hispanics were twice as likely to show improvement in MCS scores as opposed to decline when compared to Hispanics.

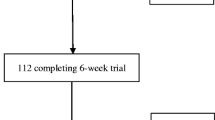

As described in Table 4, no significant association was found between the classes of antidepressants used among individuals with depression and the tendency to show improvement, decline or no change in the self-reported mental health status and psychological distress. Furthermore, only “health stopped social activity” was found to be a significant predictor of the change in mental health status and psychological distress. The odds ratio of improvement in self-reported mental health and psychological distress of individuals reporting that their “health never stopped their social activity” was 0.354 (95 % CI 0.162–0.774) and 0.083 (95 % CI 0.033–0.207), respectively, as compared to those whose “health always stopped their social activity.” The key findings of the study are summarized in Fig. 2.

Percentage of individuals on the different classes of antidepressants showing improvement versus decline in the MCS scores, PCS scores, self-reported mental health and psychological distress. Those on SNRIs were significantly less likely to show improvement as opposed to decline in MCS scores over a year’s time based on multinomial logistic regression results (OR 0.337, 95 % CI 0.155–0.730). Adjusted analysis showed that individuals on any of the classes of antidepressants showed no significant improvement or decline in the PCS scores, perceived self-reported mental health status and psychological distress. CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio, PCS physical component summary, MCS mental component summary

Discussion

This study is unique, as it is one of the few studies that has explored the association between perceived mental health, psychological distress and health-related quality of life and the various classes of medications used to treat depression in patients on monotherapy in real-world settings. Moreover, this study has a longitudinal design that enabled us to evaluate the improvement in quality of life and mental health in contrast to other observational cross-sectional studies.

The results of the present study showed that a vast majority of the individuals with depression reported using SSRIs and very few individuals reported using TCAs. This could be attributed to the more severe side effects that are exhibited by TCAs in comparison with other antidepressants [5]. Descriptive statistics from the present study also showed that a majority of the individuals on monotherapy alone, taking either of the four classes of antidepressants, were found to show no change in health-related quality of life, perceived mental health status and psychological distress scores over a period of 1 year. Moreover, a higher percent of individuals showed a decline in PCS scores as compared to the percent of individuals showing improved scores. This was seen in patients taking any of the four classes of antidepressants. A probable explanation for this finding is that the medical treatments used to treat mental disorders strongly predict the mental health status of an individual and might improve mental health more than physical health [26]. Also, side effects of antidepressants, which include weight gain, loss of libido, tremors, nervousness, nausea and headache, might also lead to a decline in physical health scores. However, after controlling for a wide range of covariates, no significant association was found between the class of antidepressants and the tendency of individuals to show improvement, decline or no change in their PCS scores. These findings were consistent with another study that compared the health-related quality of life of antidepressant users and those who were concomitant users of antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics [27].

While comparing the association of various classes of antidepressants with MCS scores, both descriptive statistics and adjusted analysis revealed that individuals using SSRIs were significantly more likely to show improved scores, as opposed to decline in scores when compared to those using SNRIs. Our study did not directly explore the reasons behind this finding, but we can speculate that the improved MCS scores among SSRIs users could be due to the better tolerability of SSRIs when compared to SNRIs. An investigation into adverse drug effects of venlafaxine and duloxetine, which are both SNRIs, revealed that both these drugs had higher discontinuation rates as compared to SSRIs [28, 29]. Additionally, other studies comparing the safety of venlafaxine versus escitalopram reported that even though the two drugs had comparable efficacy, escitalopram was better tolerated and was more cost-effective [30–32]. There is some evidence that SNRIs are less well tolerated than SSRIs, and therefore SSRIs users might be more likely to continue their therapy and have better mental health outcomes as compared to SNRIs users. However, a number of studies have also found no significant evidence of the superiority of SSRIs over SNRIs, and vice versa [33–35]. Furthermore, another study that compared the association of venlafaxine and SSRIs with the quality of life showed no statistically significant difference [28]. Although the present study shows that individuals taking SSRIs are more likely to show improvement on MCS scores as opposed to those taking SNRIs, such findings were not replicated when perceived mental health status was used as an outcome variable and no causal explanation can attributed to these findings. Further research is needed to determine the reason that patients taking SSRIs show better MCS scores as compared to those taking SNRIs. Insignificant differences in MCS scores between SSRIs and other antidepressants could be due to the similar efficacy and side-effect profiles of the two classes.

The above-mentioned findings of the association of antidepressant classes with MCS scores of the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey were not replicated when examined with respect to improvement in perceived self-reported mental health and psychological distress. Researchers have found that self-reported health, both physical and mental, also reflects physical functioning, vitality, health behaviors, effective coping with disease and even spiritual orientation [36]. Respondents may integrate a variety of considerations to derive an overall health assessment [36]. Self-reported mental health may hence analogously result from combining multiple considerations, which may also include physical health, whereas MCS may represent only a subset of factors that might be more specific to depression and mental illness. This presents a possible explanation for the results on perceived mental health status being similar to PCS scores as compared to MCS scores of the Short Form Health Survey. Psychological distress, measured using K6, appears to be a useful screener for depression, as examined by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in population-based studies [18]. Therefore, it was chosen as a separate outcome measure. Although all the outcomes used in the study provide a measure of mental health, we chose multiple outcome measures in order to see the variation in results. In the present study, results for psychological distress were in line with the findings of PCS and self-reported mental health. Also, no significant difference was observed between SSRIs and SNRIs. This could be because the questions on K6 can be more depression specific as compared to the questions assessing mental health on the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey. Similar efficacy of both SSRIs and SNRIs in treating depression may enable patients to keep their depression under control and may show similar scores on K6 for both classes of drugs.

Since health-related quality of life and mental health are multidimensional concepts, we tried to account for as many relevant covariates as possible. In addition to the above-mentioned findings, our study also found significant predictors of improvement in quality of life, perceived self-reported mental health and psychological distress. The present study found a significant association between age and change in PCS scores. Individuals over 65 years of age were found to significantly show more improvement as opposed to decline when compared to younger adults. The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study evaluating the health-related quality of life in depression also found age to be a significant predictor of quality of life [37]. One possible explanation for this is that younger adults might experience more stress than older adults. Insurance type, income and number of comorbidities were found to have significant association with improvement in PCS scores. This is in line with another study, which showed a positive correlation between these factors and physical health [27]. Another interesting finding of the present study was that social activity was found to have a significant association with each of the three outcomes assessing mental health. Those individuals who reported that their health sometimes or never stopped their social activity were less likely to show improved scores as compared to those who reported that their health always stopped their social activity. Individuals with greater depressive symptoms report more frequent negative social interactions [38]. Individuals reporting that their disease state often stops them from having social interactions may be suffering from more severe depression and may experience worse scores before treatment. However, these individuals may report improved scores once they begin antidepressant therapy to control depression.

Study limitations

No causal relationship can be inferred based solely on the findings of this study. Due to the limitation of the MEPS database, we could not adjust for severity of depression, illness duration and medication adherence. Additionally, we could not adjust for unknown information on the participants’ use of alcohol and other drugs as well as other treatments for depression such as psychotherapy, which may include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT) and electroconvulsive therapy. Each of these covariates can influence the health-related quality of life and mental health outcomes in patients with depression. Additionally patients’ self-reported medical conditions are mapped into only three-digit ICD-9 codes in MEPS, which makes it impossible to distinguish between non-psychotic disorders. To overcome this limitation, only individuals who were prescribed medications that are used to treat depression were included in the study. Other limitations of using a retrospective database include missing information, which may therefore introduce bias. Social desirability bias and recall bias are other possible limitations, as the information in the database is self-reported by the respondents, which may not always be reliable. However, previous researchers have deemed this information to be of a reasonable quality.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, findings from this study will add to the literature guiding clinicians in prescribing antidepressants. The results of the study suggest that SSRIs significantly improved MCS scores as compared to SNRIs; however, further research is needed to determine why SSRIs appear to be associated with greater improvement in mental health as compared to SNRIs. We suggest that future studies examine the role of antidepressants on health-related quality of life and mental health after taking baseline scores into consideration. Other factors such as medication adherence, severity of illness and subjective tolerability should also be considered. This study can serve as a reference for researchers in this area who can further strengthen the study design, which may provide some additional guidance to clinicians in choosing one class of antidepressant over another. Also, since the effectiveness of medications used to treat depression may vary within each drug class, future research can focus on comparative effectiveness of the most widely prescribed antidepressants.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). An estimated 1 in 10 U.S. adults report depression. Retrieved August 22, 2011 from http://www.cdc.gov/Features/dsDepression.

Wells, K. B., Stewart, A., Hays, R. D., et al. (1989). The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 262, 916–919.

Broadhead, E. W., Blazer, D. G., George, L. K., et al. (1990). Depression, disability days and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. Journal of the American Medical Association, 264, 2524–2528.

Ormel, J., VonKorff, M., Ustun, B., et al. (1994). Common mentadisorders and disability across cultures: results from the WHO collaborative study on psychological problems in general health care. Journal of the American Medical Association, 272, 1741–1748.

Cramer, J. A., & Rosenheck, R. (1998). Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services, 49(2), 196–201.

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, U. S. (2010). With, & special feature on death and dying. Table 95. Hyattsville, M. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus10.pdf.

Centres for Medicare and Medicaid & Medicaid Services. (2013). Antidepressant medications: Use in adults, from http://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Fraud-Prevention/Medicaid-Integrity-Education/Pharmacy-Education-Materials/Downloads/ad-adult-factsheet.pdf.

American Psychiatric Association. (2010). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf.

Stark, P., & Hardison, C. D. (1985). A review of multicenter controlled studies of fluoxetine vs imipramine and placebo in outpatients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 46(3 (Sect. 2)), 53–58.

Song, F., Freemantle, N., Sheldon, T., et al. (1993). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: Meta-analysis of efficacy and acceptability. British Medical Journal, 306, 683–687.

Workman, E., & Short, D. (1993). Atypical antidepressants versus imipramine in the treatment of major depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 54, 5–12.

Rickels, S., Schweizer, E., Clary, C., et al. (1994). Nefazodone and imipramine in major depression: A placebo-controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 802–805.

Mendels, J., Reimherr, F., Marcus, R. N., et al. (1995). A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of two dose ranges of nefazodone in the treatment of depressed outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 56(6 Suppl.), 30–36.

Preskorn, S. H. (1995). Comparison of the tolerability of bupropion fluoxetine, imipramine, nefazodone, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 56(Suppl.), 12–21.

Simon, G. E., VonKorff, M., Heiligenstein, J. H., et al. (1996). Initial antidepressant choice in primary care: Effectiveness and cost of fluoxetine vs tricyclic antidepressants. Journal of the American Medical Association, 275, 1897–1902.

IsHak, W. W., Greenberg, J. M., Balayan, K., Kapitanski, N., Jeffrey, J., Fathy, H., et al. (2011). Quality of life: The ultimate outcome measure of interventions in major depressive disorder. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 19(5), 229–239.

Bolton, J. M., & Robinson, J. (2010). Population-attributable fractions of Axis I and Axis II mental disorders for suicide attempts: Findings from a representative sample of the adult, noninstitutionalized US population. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2473–2480.

Lorenz, R. A., Whitley, H. P., & McCoy, E. K. (2010). Safety of varenicline in patients with mental illness. Primary Psychiatry, 17(9), 60–66.

AHRQ. (2011). MEPS-HC sample design and collection process. Rockville: AHRQ. [cited 2011 17th February]. http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/hc_data_collection.jsp.

AHRQ. (2008). MEPS HC-120: 2008 Medical Conditions. Center for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends540. Gaither Road Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. cited 2012 9th August]. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h120/h120doc.shtml.

Khanna, R., Bhanegaonkar, A., Colsher, P., Madhavan, S. S., & Halverson, J. (2009). Breast cancer screening, incidence, and mortality in West Virginia. West Virginia Medical Journal, 105(S1), 24–32.

Cheak-Zamora, N., Wyrwich, K., & McBride, T. (2009). Reliability and validity of the SF-12v2 in the medical expenditure panel survey. Quality of Life Research, 18(6), 727–735. doi:10.1007/s11136-009-9483-1.

Ware, J. E. J., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. D. (1996). A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 34(3), 220–233.

Norman, G. R., Sloan, J. A., & Wyrwich, K. W. (2003). Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical Care, 41, 582–592.

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S.-L. T., et al. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in nonspecific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976.

Hoff, R. A., Bruce, M. L., Kasl, S. V., et al. (1997). Subjective ratings of emotional health as a risk factor for major depression in a community sample. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 167–172.

Al-Ruthia, Y. S., Hong, S. H., & Solomon, D. (2015). Do depressed patients on adjunctive atypical antipsychotics demonstrate a better quality of life compared to those on antidepressants only? A comparative cross-sectional study of a nationally representative sample of the US population. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 11(2), 228–240.

Selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) for patients with depression: Executive summary of final report A05-20A, Version 1.0 (2005). In Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care: Executive Summaries. Cologne, Germany: IQWiG (Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0049661.

Taylor, D., Paton, C., & Kapur, S. (2012). The South London and Maudsley NHS FoundationTrust Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry (11th ed.). London: Wiley.

Maity, N., Ghosal, M. K., Gupta, A., Sil, A., Chakraborty, S., & Chatterjee, S. (2014). Clinical effectiveness and safety of escitalopram and desvenlafaxine in patients of depression with anxiety: A randomized, open-label controlled trial. Indian Journal of Pharmacology, 46(4), 433–437. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.135959.

Nordstrom, G., Danchenko, N., Despiegel, N., & Marteau, F. (2012). Cost-effectiveness evaluation in Sweden of escitalopram compared with venlafaxine extended-release as first-line treatment in major depressive disorder. Value Health, 15(2), 231–239. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2011.09.011.

Kornstein, S. G., Li, D., Mao, Y., Larsson, S., Andersen, H. F., & Papakostas, G. I. (2009). Escitalopram versus SNRI antidepressants in the acute treatment of major depressive disorder: Integrative analysis of four double-blind, randomized clinical trials. CNS Spectrums, 14(06), 326–333.

Bauer, M., Tharmanathan, P., Volz, H. P., Moeller, H. J., & Freemantle, N. (2009). The effect of venlafaxine compared with other antidepressants and placebo in the treatment of major depression: A meta-analysis. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 259, 172–185.

Cipriani, A., Brambilla, P., Furukawa, T. A., Geddes, J., Gregis, M., & Hotopf, M., et al. (2005). Fluoxetine versus other types of pharmacotherapy for depression. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4), CD004185–CD004185. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004185.pub2.

Panzer, M. J. (2005). Are SSRIs really more effective for anxious depression? Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 17, 23–29.

Fleishman, J. A., & Zuvekas, S. H. (2007). Global self-rated mental health: associations with other mental health measures and with role functioning. Medical Care, 45(7), 602–609.

Trivedi, M. H., Wisniewski, S. R., Nierenberg, A. A., & Gaynes, B. N. (2010). Health-related quality of life in depression: A STAR* D report. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 22(1), 43–55.

Steger, M. F., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Depression and everyday social activity, belonging, and well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(2), 289–300. doi:10.1037/a0015416.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, D., Vaidya, V., Patel, A. et al. Assessment of health-related quality of life, mental health status and psychological distress based on the type of pharmacotherapy used among patients with depression. Qual Life Res 26, 969–980 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1417-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1417-0