Abstract

Purpose

Although frailty was originally a medical concept, nowadays more and more researchers are convinced of its multidimensional nature, including a psychological and social domain of frailty as well as a physical domain. The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that the prediction of quality of life by physical frailty components is improved by adding psychological and social frailty components.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out with a sample of Dutch citizens. A total of 1,031 people aged 65 years and older completed a Web-based questionnaire containing the Tilburg Frailty Indicator for measuring physical, psychological, and social frailty, and the WHOQOL-BREF for measuring four quality of life domains (physical health, psychological, social relations, environmental).

Results

The findings show that the prediction of all quality of life domains by eight physical components of frailty was improved after adding four psychological and three social frailty components. The psychological frailty component ‘feeling down’ significantly improved the prediction of all four quality of life domains, after controlling for the effects of background characteristics and all other frailty components.

Conclusion

This study emphasizes the importance of a multidimensional assessment of frailty in the prediction of quality of life in older people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Frail older people have a higher risk of disability [1], health-care utilization such as hospitalization [2, 3] and institutionalization [4, 5], and premature death [2, 6] compared to non-frail older people. Physical frailty is also associated with lower quality of life of older persons [7–9]. The focus of this study is on the associations of frailty with different aspects of quality of life, using not only physical but also other domains of frailty.

Medicine has a strong influence on how frailty is conceptualized nowadays [10], meaning that frailty is usually predominantly defined in terms of physical function. However, more and more researchers are currently convinced of the multidimensional nature of frailty [11–13]. A recently developed multidimensional definition of frailty is as follows: frailty is a dynamic state affecting an individual who experiences losses in one or more domains of human functioning (physical, psychological, social), which is caused by the influence of a range of variables and which increases the risk of adverse outcomes [14]. The inclusion of psychological and social components next to physical components makes a multidimensional definition of frailty suited to nursing, doing greater justice to the integral approach central to nursing care.

Quality of life is defined by the World Health Organization Quality of Life Group (1995, p. 1405) as ‘an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns’ [15]. The definition reflects a multidimensional concept addressing physical health, psychological state, social relationships, and environment based on subjective appraisals. Quality of life is an important outcome that is linked to the goals of nursing [16]. Nursing older people aims to maintain or improve their quality of life. To support independent living in older people, nurses and other health- and social-care professionals may need to carry out preventive interventions focusing on aspects related to quality of life, aimed at delaying hospitalization or institutionalization. To enable early detection of problems and preventive interventions, identifying components of frailty that are associated, cross-sectionally, with quality of life, is an important first step.

No consensus exists on effects of socio-demographic characteristics (sex, age, education, marital status) on quality of life [16]. For instance, some studies observed a positive association between level of education and quality of life [17, 18], whereas other studies found no such association [19, 20]. Similarly, Netuveli and Blane [21] found no association between age and quality of life, whereas Paskulin et al. [17] found higher quality of life for participants of 80 years and older compared to those of 60–79 years, and Raphael et al. [19] found lower quality of life for those of 80 years and older. Multimorbidity is acknowledged to negatively affect quality of life of older people [22], especially the physical domain [23, 24]. Our use of a large sample enables us to draw firm conclusions with respect to effects of socio-demographic characteristics and multimorbidity on quality of life.

Previous research on the association between frailty and quality of life domains found the expected negative associations [8, 25, 26]. Research on predicting quality of life with physical frailty employed the phenotype of frailty by Fried et al. [2], consisting of the physical components weakness, slowness, poor endurance, weight loss, and low physical activity. Poor endurance and slowness had the strongest negative effect on quality of life [7, 27], measured with the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Short Form-36 (SF-36) [28]. It is also well known that the psychological and social frailty domains are associated with adverse outcomes related to quality of life, such as institutionalization [4, 5] and mortality [4, 5, 29]. For instance, Andrew et al. [30] observed an association of increasing social frailty with medium-term survival (5–8 years). Although quality of life was not the subject of study in aforementioned studies, their findings on outcomes related to quality of life suggest that it is important to consider frailty broadly when examining quality of life.

The present study centers on explaining quality of life, incorporating different domains (physical, psychological, social, environmental), with frailty as a multidimensional concept, incorporating physical, psychological, and social components and domains. The main goal of this study is testing the hypothesis that the prediction of quality of life by physical frailty components is improved by adding psychological and social frailty components. In contrast to most previous research, the focus is on frailty components rather than on frailty domains. Frailty components are more specific compared to domains, providing more guidance for (preventive) interventions. The hypothesis is tested in a large sample of people aged 65 and older, because more benefits are expected when prevention is started earlier [31].

Methods

Study population and data collection

The ‘Senioren Barometer’, initiated by the Academic Collaborative Center Policy for the Elderly and Informal Care (Tranzo, Tilburg University), is a Web-based questionnaire to assess the opinion of a panel of Dutch older people (aged 50 years and older) about different aspects of life. Older people can volunteer, and participation is always without obligation. To be consistent with other frailty research [1, 2, 7], we selected participants of 65 years and older from the panel. In the period December 2009 and January 2010, 1,323 people of 65 years and older completed a questionnaire containing questions regarding frailty, quality of life, and background characteristics. We excluded 292 cases from further analyses because of missing values for frailty and quality of life, yielding a sample size of 1,031.

The sample was invited to participate in the study in different ways and through multiple sources. Through the website www.seniorenbarometer.nl, people could indicate that they wanted to participate in research among the target group. Organizations for the elderly in the Netherlands were asked to issue an announcement of the study on their websites so that persons who were interested in participating could register. A third major source of participants was persons who attended computer training courses for older persons given by a large training and educational institute in the Netherlands.

Medical-ethics approval was not necessary as particular treatments or interventions were not offered or withheld from respondents. The integrity of respondents was not encroached on as a consequence of participating in the study, which is the main criterion in medical-ethical procedures in the Netherlands [32]. Informed consent, in terms of information-giving and maintaining confidentiality, was respected.

Measures

Frailty

Frailty was assessed using part B of the Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI) (See ‘Appendix’) [25]. Part B of the TFI contains fifteen questions on components of frailty. Eight components refer to physical frailty: unintended weight loss, difficulty in walking, strength in the hands, physical tiredness, physical health, balance, and hearing and vision problems. In this study, we measured physical activity instead of physical health, because physical activity is a criterion of the phenotype of frailty by Fried et al. [2]. In addition, physical activity belongs to the physical components in our integral conceptual model of frailty [14]. For measuring physical activity, we used the question ‘Do you find that you can be sufficiently physically active?’, as we proposed in a previous study [25]. Cognition, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and coping are four components belonging to psychological frailty. The three components of social frailty are living alone, social relations, and social support. Eleven items from the TFI have two response categories ‘yes’ and ‘no’, whereas four items have three response categories ‘yes’, ‘sometimes’, and ‘no’. The item cognition is dichotomized into ‘yes’ and ‘sometimes or no’, and the other three items were dichotomized into ‘yes or sometimes’ and ‘no’ (see ‘Appendix’). After recoding, scales are obtained with ranges 0–8 (physical), 0–4 (psychological), and 0–3 (social). Previous studies concluded that the TFI is a valid and reliable measure to assess frailty in a sample of community-dwelling older people [25, 26, 33]. In the present study, the reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) for total, physical, psychological, and social frailty was 0.71, 0.67, 0.54, and 0.51, respectively.

Quality of life

The WHOQOL-BREF was used to assess quality of life. The WHOQOL-BREF is a 26-item self-report scale, covering four domains of quality of life—physical health (seven items), psychological (six items), social relations (three items), and environmental (eight items)—and includes one overall quality of life item and one general health item [34, 35]. In this study, we used only the 24 domain items. All items were rated on a 5-point scale with a higher score indicating a higher quality of life. Domain scores were calculated by multiplying the mean domain score by a factor of 4 and accordingly resulting in a range from 4 to 20 for each quality of life domain. Many studies have shown that the WHOQOL-BREF has adequate psychometric properties among different populations, including older people [35, 36]. In the present study, the reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha) were 0.80, 0.73, 0.64, and 0.77 for physical health, psychological, social relations, and environmental, respectively.

Background characteristics: socio-demographic and multimorbidity

Socio-demographic characteristics assessed were sex, age (in years), ethnicity (Dutch versus other), marital status (five categories), net household income (nine categories), and highest education attained (six categories). See Table 1 for a detailed description of the answering categories. Multimorbidity was assessed with the question ‘Do you have two or more diseases and/or chronic disorders?’ (yes/no).

Analysis strategies

After determining the characteristics of participants using descriptive statistics, variables were coded for analysis. Dummies were created for marital status (‘1’ married or cohabiting and ‘0’ rest), sex (‘1’ woman, ‘0’ man), and multimorbidity (‘1’ yes, ‘0’ no). The models incorporated linear effects of age, education, and income. We specified linear effects of our predictors since linear effects are good approximations of possible nonlinear effects that are monotonically increasing or monotonically decreasing. Because of a low frequency of non-Dutch older people (3.9 %), we excluded the variable ethnicity from further analyses.

Bivariate associations between each background variable and frailty component on the one hand and the four quality of life domains on the other hand were tested using regression analyses. The sequential regression analyses consisted of three blocks. The effect of the background characteristics was estimated in the first block. The second block contained the eight physical components of frailty. Finally, in the third block, the four psychological and three social components of frailty were added to the model. The second block enabled testing the effect of physical components on quality of life after controlling for background characteristics; the third block enabled testing of psychological and social components after controlling for both physical frailty and background characteristics. We tested the individual regression coefficients of the full model including all predictors, and whether each block increased the prediction of each quality of life domain, using the change in R 2.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, IBM Corp., Somers, NY, United States of America).

Results

Participant characteristics

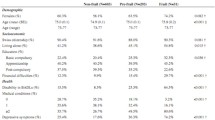

Table 1 presents an overview of descriptive statistics of the sample. The participants’ mean age was 73.4 years (SD = 5.8) with a range of 65–95; 66.8 % were men, and 71.1 % were married or cohabiting.

In a previous study, it was concluded that a cut-off point of 5 on the TFI total score was optimal in distinguishing frail older people from those who are not frail [25]. Applying this cut-off point identified 27.7 % of the sample as being frail. The means and standard deviations of the frailty domains indicate that there was sufficient heterogeneity in frailty, but that most older people scored low on frailty. Our respondents on average exhibited relatively good quality of life, since their mean scores on the four quality of life domains were higher compared to normative data [37]. The correlations between all frailty and quality of life scales are shown in Table 2. All correlations were significant at p < .001. The correlations between the frailty domains were small to medium (.23–.28) and medium to strong between the quality of life domains (.42–.66). Correlations between frailty on the one hand and quality of life on the other hand were all negative, varying from .25 to .68.

Regression analyses

Table 3 presents the results of the bivariate and sequential regression analyses on the four domains of quality of life (physical health, psychological, social relations, environmental). Columns 2–4, 8–10, 14–16, and 20–22 present the results of the bivariate regressions, with p values significant at .05 printed in bold. Younger age, being married, higher income, and no multimorbidity were associated with higher scores on all four quality of life domains. Higher education was associated with higher quality of life except social relations. Being a woman was associated with lower physical and psychological quality of life. Finally, all physical, psychological, and social components of frailty were significantly associated with all four quality of life domains, except the association of poor hearing with social relations quality of life.

Columns 5–7, 11–13, 17–19, and 23–25 summarize the results of the sequential regression analyses. ‘R 2 total’ indicates how much of the variance of the four quality of life domains was explained by all predictors together (last row), and the significance of ‘R 2 total’. Total explained variances were 56.5 % (physical health), 46.9 % (psychological), 27.5 % (social relations), and 34.6 (environmental). The ΔR 2 (last row of each block) indicates the increase in explained variance and its significance after adding the variables of that block to the model. All ΔR 2 were significant at .001, meaning that (1) the background characteristics predicted the quality of life domains, (2) physical frailty improved the prediction of quality of life after controlling for the effects of background characteristics, and (3) psychological and social frailty together improved the prediction of quality of life after controlling for background characteristics and physical frailty. The psychological and social frailty components explained an additional 2.8, 20.5, 15.3, and 7.9 % of quality of life domains physical health, psychological, social relations, and environmental, respectively. These represent large effect sizes (f 2 around .25 or higher) for psychological (f 2 = .39), medium effect sizes (f 2 around .15) for social (f 2 = .21) and environmental (f 2 = .12), and small (f 2 = .02) to medium effect size for physical quality of life (f 2 = .064) [38].

The regression coefficients and their tests in columns 5–7, 11–13, 17–19, and 23–25 refer to the effects of individual predictors in the full model including all predictors listed in Table 3. None of the background characteristics had an effect on all four quality of life domains after controlling for the frailty components. Income had a positive effect on all domains, except social relations. Being a woman had a positive effect on all domains, except physical health. The only other effect with p < .01 was a negative association between multimorbidity and the physical health domain.

Of the eight individual physical frailty components, only physical tiredness significantly improved the prediction of all quality of life domains after controlling for the effects of all other variables; physical tiredness was associated with lower quality of life. Physical inactivity was associated with lower quality of life, except on social relations. Difficulty maintaining balance was associated with lower quality of life in two domains; unexplained weight loss, difficulty in walking, lack of strength in the hands, and poor vision with one, and poor hearing with none of the quality of life domains. The prediction of quality of life domains physical health, psychological, social relations, and environmental were significantly improved by six, three, one, and three physical frailty components.

The psychological frailty component ‘feeling down’ was associated with lower scores on each of the four quality of life domains, even after controlling for the effect of all background variables and other frailty components; its effect was weak on physical health (f 2 = .02) and environmental (f 2 = .02), weak to medium on social (f 2 = .06), and medium on psychological quality of life (f 2 = .15). The psychological frailty component ‘feeling nervous or anxious’ and the social frailty components ‘lack of social relations’ and ‘lack of social support’ were associated with lower scores on three quality of life domains. The psychological component ‘unable to cope with problems’ was associated with lower scores on two domains. The psychological frailty component ‘problems with memory’ and social frailty component ‘living alone’ were associated with none of the quality of life domains. Noteworthy is that three psychological frailty components improved the prediction of psychological quality of life, and at the same time, two of these components improved the prediction of the other three quality of life domains. Similarly, two social frailty components improved the prediction of psychological, social relations, and environmental quality of life.

Discussion

To enable early detection of problems and preventive interventions, identifying components of frailty that are associated with quality of life is an important first step. In this cross-sectional study, we tested the hypothesis that the prediction of quality of life by physical frailty components is improved by adding psychological and social frailty components in a sample of 1,031 older people in the Netherlands. We used two validated assessment tools: part B of the TFI for measuring frailty [25, 26] and the WHOQOL-BREF for assessing quality of life in four domains (physical health, psychological, social relations, and environmental) [35].

Previous research revealed contrary effects of socio-demographic characteristics on quality of life. In our study, being married, higher income, and higher education were associated with higher scores on one or more quality of life domains. No effect of age on quality of life was observed after controlling for other variables. The effect of sex was complex. Being a woman was associated only with lower physical and psychological quality of life, but after controlling for the other variables, the effect on physical quality of life disappeared and being a woman was associated with higher social and environmental quality of life. More research is needed to understand these complex effects of sex. As expected, multimorbidity was associated with lower physical quality of life. Although all eight physical frailty components were associated with each quality of life domain (except poor hearing), only physical tiredness significantly improved the prediction of all quality of life domains after controlling for the effects of all other variables. Physical tiredness was associated with lower quality of life, which was in line with other research that established the association between endurance (physical tiredness) and all scales of the SF-36 except role limitations due to physical and emotional problems [27]. Furthermore, a study by Bilotta et al. [8] found that reduced energy level (a concept which seems to be very close to physical tiredness) was the only physical frailty criterion independently associated with a poor quality of life, measured with the Older People’s Quality of Life (OPQOL) questionnaire [39].

Our study showed that the prediction of all four quality of life domains by eight physical components of frailty was improved after adding seven psychological and social frailty components. The psychological component ‘feeling down’ significantly improved the prediction of all quality of life domains, after controlling for the effects of all other variables. Feeling down refers to depression, a well-known criterion for measuring frailty [40, 41] and a common complication of the frailty identity crisis [42].

In a study by Bilotta et al. [8], depression was also found to be a predictor of a poor quality of life independently of physical frailty. The finding that feeling down is associated with lower quality of life in all domains is supported by Ten Doesschate et al. [43], who observed an association between an increase in the level of depressive symptoms with a decrease in all scales of the SF-36 developed by Ware et al. [28]. Penninx et al. [44] also observed an association between chronic depression and a greater decline in physical function in a longitudinal study among community-dwelling older people.

Social components have been often neglected in the definition of frailty [11, 12]. This study found that the social components ‘lack of social relations’ and ‘lack of social support’ significantly improved the prediction of three quality of life domains, after controlling for the effects of all other variables. This finding is supported by a Dutch qualitative study exploring the meaning of quality of life among community-dwelling frail older people [45]. They reported social contacts as one of the most important factors for quality of life. Other authors also reported that having poor social relationships and support was a main factor that affected quality of life negatively [46]. For frail older people, the presence of others to engage with their stories, to recognize, and to value the daily rituals that anchor their experience is vital if they are to retain quality of life [47].

Total explained variances of the quality of life domains varied from 27.5 % (social relations) to 56.5 % (physical health). Other variables that are known to have an effect on quality of life are personality characteristics such as adaptation and resilience [21], perceived control over life [48], and spirituality [49]. What the effect is of these personality characteristics in relation and combination with the effects of the frailty domains could be explored in future research.

Some limitations should be noted in interpreting the results of this study. First, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow for any prospective conclusion on the relationship of physical, psychological, and social frailty components with quality of life domains. A longitudinal design is required to address this issue in more detail; follow-up of the cohort will allow us to examine the relationship between frailty components at baseline and subsequent quality of life domains. Second, the potential representativeness of the sample can be questioned due to the fact that the participants completed a Web-based questionnaire [50]. That is, the sample may be biased due to the exclusion of those people without Internet access or without Internet skills; 66.8 % of the participants were men, while of the Dutch population aged 65 and over, only 44.4 % is men [51]. Perhaps, men are more regular Internet users or have more frequent access to the Internet than women. The average age of the sample (73.4) is not much different from the average age (74.5) of people older than 65 years in the Dutch population [52]. Research that also employs non-users is needed to verify our conclusions on the association between frailty and quality of life. A final limitation is that we used a self-report questionnaire rather than validated physical performance-based tests and psychological or social scales for interviewing older people. However, previous studies established the construct validity and predictive validity of the TFI by establishing the correlation between the TFI and physical performance-based tests, and psychological and social scales [25, 26]. Moreover, Gobbens and van Assen [53] showed that these tests and scales did not improve the prediction of adverse outcomes by the TFI, with the exception of disability. Therefore, we do not believe that the use of the TFI hampers the validity of our conclusions concerning the associations between frailty and quality of life.

The added value of a multidimensional definition of frailty in practice has yet to be proven through scientifically evaluated interventions. Early identification and intervention can enable frail older people to maintain control over their quality of life for longer [54]. Health-care professionals such as nurses, nurse practitioners, and general practitioners can use the TFI to identify frail older people; it is a simple and potentially suitable screening instrument for assessing frailty in a primary health-care setting [55]. Studies show that nurses are capable of fulfilling extended roles [56, 57]. They can offer an appropriate solution to the difficulties faced by general practitioners in providing high-quality services to older people, such as an increasing workload and consequently limited consultation time. In addition, using their integral approach to human functioning nurses can act as a case manager for frail older people and make a multidisciplinary care plan in cooperation with other health-care professionals. This plan should be aimed at preventing or delaying well-known adverse outcomes of frailty such as disability [1], health-care utilization [2, 5], and maintaining or improving the quality of life. Health-care professionals should discuss with frail older people what is important to them in relation to quality of life as it varies among older people according to their integral needs.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates and emphasizes the importance for nursing practice of a multidimensional definition of frailty in the prediction of quality of life in older people. Due to its multidimensional approach of frailty, the TFI has potential in nursing practice.

References

Boyd, C. M., Xue, Q. L., Simpson, C. F., Guralnik, J. M., & Fried, L. P. (2005). Frailty, hospitalization, and progression of disability in a cohort of disabled older women. The American Journal of Medicine, 118(11), 1225–1231.

Fried, L. P., Tangen, C. M., Walston, J., et al. (2001). Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. Journal of Gerontology Medical Sciences, 56(3), M146–M156.

Ravaglia, G., Forti, P., Lucicesare, A., Pisacane, N., Rietti, E., & Patterson, C. (2008). Development of an easy prognostic score for frailty outcomes in the aged. Age and Ageing, 37(2), 161–166.

Jones, D. M., Song, X., & Rockwood, K. (2004). Operationalizing a frailty index from a standardized comprehensive geriatric assessment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52(11), 1929–1933.

Rockwood, K., Song, X., MacKnight, C., et al. (2005). A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 173(5), 489–495.

Song, X., Mitnitski, A., & Rockwood, K. (2010). Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(4), 681–687.

Chang, Y. W., Chen, W. L., Lin, F. G., et al. (2012). Frailty and its impact on health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study on elder community-dwelling preventive health service users. PLoS ONE,. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038079.

Bilotta, C., Bowling, A., Case, A., et al. (2010). Dimensions and correlates of quality of life according to frailty status: a cross-sectional study on community-dwelling older adults referred to an outpatient geriatric service in Italy. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes,. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-8-56.

Masel, M. C., Ostir, G. V., & Ottenbacher, K. J. (2010). Frailty, mortality, and health-related quality of life in older Mexican Americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(11), 2149–2153.

Levers, M. J., Estabrooks, C. A., & Ross Kerr, J. C. (2006). Factors contributing to frailty: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56(3), 282–291.

Markle-Reid, M., & Browne, G. (2003). Conceptualizations of frailty in relation to older adults. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44(1), 58–68.

Gobbens, R. J., Luijkx, K. G., Wijnen-Sponselee, M. T., & Schols, J. M. (2010). Toward a conceptual definition of frail community dwelling older people. Nursing Outlook, 58(2), 76–86.

Hogan, D. B., MacKnight, C., & Bergman, H. (2003). Models, definitions, and criteria of frailty. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 15(3 Suppl), 1–29.

Gobbens, R. J., Luijkx, K. G., Wijnen-Sponselee, M. T., & Schols, J. M. (2010). Towards an integral conceptual model of frailty. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 14(3), 175–181.

The WHOQOL Group. (1995). The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science & Medicine, 41(10), 1403–1409.

Lee, T. W., Ko, I. S., & Lee, K. J. (2006). Health promotion behaviors and quality of life among community-dwelling elderly in Korea: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43(3), 293–300.

Paskulin, L., Vianna, L., & Molzahn, A. E. (2009). Factors associated with quality of life of Brazilian older adults. International Nursing Review, 56(1), 109–115.

Lubetkin, E. I., Jia, H., Franks, P., & Gold, M. R. (2005). Relationship among sociodemographic factors, clinical conditions, and health-related quality of life: Examining the EQ-5D in the U.S. general population. Quality of Life Research, 14(10), 2187–2196.

Raphael, D., Brown, I., Renwick, R., Cava, M., Weir, N., & Heathcote, K. (1997). Measuring the quality of life of older persons: A model with implications for community and public health nursing. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 34(3), 231–239.

Hilleras, P. K., Jorm, A. F., Herlitz, A., & Winblad, B. (2001). Life satisfaction among the very old: A survey on a cognitively intact sample aged 90 years or above. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 52(1), 71–90.

Netuveli, G., & Blane, D. (2008). Quality of life in older ages. British Medical Bulletin, 85, 113–126.

Hunger, M., Thorand, B., Schunk, M., et al. (2011). Multimorbidity and health-related quality of life in the older population: results from the German KORA-age study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes,. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-9-53.

Rijken, M., van Kerkhof, M., Dekker, J., & Schellevis, F. G. (2005). Comorbidity of chronic diseases: Effects of disease pairs on physical and mental functioning. Quality of Life Research, 14(1), 45–55.

Fortin, M., Bravo, G., Hudon, C., et al. (2006). Relationship between multimorbidity and health-related quality of life of patients in primary care. Quality of Life Research, 15(1), 83–91.

Gobbens, R. J., van Assen, M. A., Luijkx, K. G., Wijnen-Sponselee, M. T., & Schols, J. M. (2010). The Tilburg Frailty Indicator: Psychometric properties. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 11(5), 344–355.

Gobbens, R. J., van Assen, M. A., Luijkx, K. G., & Schols, J. M. (2012). The predictive validity of the Tilburg Frailty Indicator: Disability, health care utilization, and quality of life in a population at risk. The Gerontologist, 52(5), 619–631.

Lin, C. C., Li, C. I., Chang, C. K., et al. (2011). Reduced health-related quality of life in elders with frailty: A cross-sectional study of community-dwelling elders in Taiwan. PLoS ONE,. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021841.

Ware, J. E, Jr, & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483.

Pilotto, A., Rengo, F., Marchionni, N., et al. Comparing the prognostic accuracy for all-cause mortality of frailty instruments: A multicentre 1-year follow-up in hospitalized older patients. PLoS One, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029090.

Andrew, M. K., Mitnitski, A. B., & Rockwood, K. (2008). Social vulnerability, frailty and mortality in elderly people. PLoS ONE,. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002232.

Treurniet, H. F., Hoeymans, N., Gijsen, R., Poos, M. J., van Oers, J. A., & Thien, W. M. (2005). Health status and the challenges for prevention in the Netherlands. Public Health, 119(3), 159–166.

Central Committee on Research inv. Human Subjects. (2010). Does your study have to be reviewed? http://www.ccmo-online.nl (Home > For investigators > Review step plan RC > WMO) Accessed June 15, 2010.

Metzelthin, S. F., Daniels, R., van Rossum, E., de Witte, L., van den Heuvel, W. J., & Kempen, G. I. (2010). The psychometric properties of three self-report screening instruments for identifying frail older people in the community. BMC Public Health,. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-176.

WHOQOL Group. (1998). Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine, 28(3), 551–558.

Skevington, S. M., Lotfy, M., & O’Connell, K. A. (2004). The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Quality of Life Research, 13(2), 299–310.

Kalfoss, M. H., Low, G., & Molzahn, A. E. (2008). The suitability of the WHOQOL-BREF for Canadian and Norwegian older adults. European Journal of Ageing, 5(1), 77–89.

Hawthorne, G., Herrman, H., & Murphy, B. (2006). Interpreting the WHOQOL-BREF: Preliminary population norms and effect sizes. Social Indicators Research, 77, 37–59.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc Inc.

Bowling, A. (2009). The psychometric properties of the older people’s quality of life Questionnaire, compared with the CASP-19 and the WHOQOL-OLD. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research,. doi:10.1155/2009/298950.

Puts, M. T., Lips, P., & Deeg, D. J. (2005). Static and dynamic measures of frailty predicted decline in performance-based and self-reported physical functioning. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 58(11), 1188–1198.

Bergman, H., Béland, F., Karunananthan, S., Hummel, S., Hogan, D., & Wolfson, C. (2004). English translation of article published in ‘Gerontologie et société’. Dévelopment d’un cadre de travail pour compendre et étudier la fragilité. Gérontologie et société, 109, 15–29.

Fillit, H., & Butler, R. N. (2009). The frailty identity crisis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57(2), 348–352.

Ten Doesschate, M. C., Koeter, M. W., Bockting, C. L., & Schene, A. H. (2010). Health related quality of life in recurrent depression: A comparison with a general population sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 120(1–3), 126–132.

Penninx, B. W., Deeg, D. J., van Eijk, J. T., Beekman, A. T., & Guralnik, J. M. (2000). Changes in depression and physical decline in older adults: A longitudinal perspective. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61(1–2), 1–12.

Puts, M. T., Shekary, N., Widdershoven, G., Heldens, J., Lips, P., & Deeg, D. J. (2007). What does quality of life mean to older frail and non-frail community-dwelling adults in the Netherlands? Quality of Life Research, 16(2), 263–277.

Gabriel, Z., & Bowling, A. (2004). Quality of life from the perspectives of older people. Ageing & Society, 24(5), 675–691.

Nicholson, C., Meyer, J., Flatley, M., & Holman, C. (2012). The experience of living at home with frailty in old age: A psychosocial qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies,. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.01.006.

Bowling, A., Seetai, S., Morris, R., & Ebrahim, S. (2007). Quality of life among older people with poor functioning. The influence of perceived control over life. Age and Ageing, 36(3), 310–315.

Low, G., & Molzahn, A. E. (2007). Predictors of quality of life in old age: A cross- validation study. Research in Nursing & Health, 30(2), 141–150.

Holmes, S. (2009). Methodological and ethical considerations in designing an Internet study of quality of life: A discussion paper. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(3), 394–405.

Statline. Bevolking: geslacht, leeftijd en burgerlijke staat, 1 januari. http://www.statline.cbs.nl. Accessed November 14, 2012.

Statistics Netherlands. Population pyramid [fact sheet]. http://www.cbs.nl/en-GB/menu/themas/bevolking/cijfers/extra/piramide-fx.htm?Languageswitch=on. Accessed November 13, 2012.

Gobbens, R. J., & van Assen, M. A. (2012). Frailty and its prediction of disability and health care utilization: The added value of interviews and physical measures following a self-report questionnaire. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 55(2), 369–379.

Van Campen, C. (2011). Frail older persons in the Netherlands. The Hague: The Netherlands Institute for Social Research.

Pialoux, T., Goyard, J., & Lesourd, B. (2012). Screening tools for frailty in primary health care: A systematic review. Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 12(2), 189–197.

Fall, M., Walters, S., Read, S., et al. (1997). An evaluation of a nurse-led ear care service in primary care: Benefits and costs. British Journal of General Practice, 47(424), 699–703.

Gallagher, M., Huddart, T., & Henderson, B. (1998). Telephone triage of acute illness by a practice nurse in general practice: Outcomes of care. British Journal of General Practice, 48(429), 1141–1145.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank René Schalk for collecting and making available the data.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gobbens, R.J.J., Luijkx, K.G. & van Assen, M.A.L.M. Explaining quality of life of older people in the Netherlands using a multidimensional assessment of frailty. Qual Life Res 22, 2051–2061 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0341-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0341-1