Abstract

Purpose

Major depressive disorder (MDD) negatively impacts different aspects of an individual’s life leading to grave impairments in quality of life (QOL). We performed a detailed analysis of the interaction between depressive symptom severity, functioning, and QOL in outpatients with MDD in order to better understand QOL impairments in MDD.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted with 319 consecutive outpatients seeking treatment for DSM-IV-diagnosed MDD at an urban hospital-based outpatient clinic from 2005 to 2008 as part of the Cedars-Sinai Psychiatric Treatment Outcome Registry, a prospective cohort study of clinical, functioning, and patient-reported QOL outcomes in psychiatric disorders using a measurement-based care model. This model utilizes the following measures: (a) Depressive symptom severity: Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report (QIDS-SR); (b) Functioning measures: Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), Work and Social Adjustment Scale, and the Endicott Work Productivity Scale; and (c) Quality of Life measure: Quality of Life, Enjoyment, and Satisfaction Questionnaire—Short Form (Q-LES-Q).

Results

QOL is significantly impaired in MDD, with a mean Q-LES-Q score for this study population of 39.8 % (SD = 16.9), whereas the community norm average is 78.3 %. Regression modeling suggested that depressive symptom severity, functioning/disability, and age all significantly contributed to QOL. QIDS-SR (measuring depressive symptom severity), GAF, and SDS (measuring functioning/disability) scores accounted for 48.1, 17.4, and 13.3 % (semi-partial correlation values) of the variance in Q-LES-Q, respectively.

Conclusions

Our results show that impairment of QOL increases in a monotonic fashion with depressive symptom severity; however, depression symptom severity only accounted for 48.1 % of the QOL variance in our patient population. Furthermore, QOL is uniquely associated with measures of Functioning. We believe these results demonstrate the need to utilize not only Symptom Severity scales, but also Functioning and Quality of Life measures in MDD assessment, treatment, and research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [1]. Unfortunately, the majority of clinical and research efforts in psychiatry have been more attentive to the impact of interventions on symptom reduction than on well-being or quality of life (QOL). Psychiatric illnesses are strongly associated with impairment in QOL, frequently at levels that are equal to or exceed those of medical illnesses [2]. The traditional focus on symptom improvement in psychiatric care and research may have resulted in more emphasis being placed on symptom severity rather than including improvement in functioning and QOL.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) negatively impacts a myriad of facets of an individual’s life including functioning, satisfaction with work, relationships, leisure, physical health, sexual functioning, sleep patterns, future outlook, and overall sense of fulfillment or contentment with one’s life [3]. Studies have demonstrated that patients with MDD have significant impairments in QOL [2–5]. An analysis from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study revealed that severity of depressive symptoms was significantly associated with poor health-related quality of life [6]. Rapaport et al. [7] demonstrated significant impairments in quality of life in subjects with a broad array of different depressive and anxiety disorders entering clinical trials. This study reported that illness-specific symptom severity was significantly associated with baseline QOL impairment, but it explained only a modest proportion of the variance in QOL as measured by the Quality of Life, Enjoyment, and Satisfaction Questionnaire—Short Form (Q-LES-Q) [7]. There is a growing consensus that successful treatment should not only target symptom severity, but also impairment in functioning and QOL in leading to restoration of health [8–10].

Despite the extensive literature investigating QOL in psychiatric disorders, a detailed examination is needed for the interaction between psychiatric symptom severity, clinical characteristics, functioning, and QOL in treatment-seeking outpatients with MDD. The purpose of this study is to perform an in-depth analysis of the critical factors thought to influence QOL for individuals with MDD in an outpatient clinical practice. The first goal of this study was to investigate the impact that a variety of factors (that have been implicated usually by exploratory and secondary analyses) truly had on QOL. Thus, we explicitly sought to investigate the role that age, sex, ethnicity, recurrence, psychiatric comorbidity, and severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms had on QOL. Based on previously published work, we postulated that QOL impairment would be adversely affected by psychiatric symptom severity and speculated that QOL would be adversely affected by functional impairment [7–11]. Hence, the second goal was to investigate the relationship between symptom severity, functioning, and QOL.

Method

Recruitment method

Patients presenting for psychiatric evaluation and treatment at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center are enrolled in the Cedars-Sinai Psychiatric Treatment Outcome Registry (CS-PTR), an ongoing research study to track the outcome of psychiatric interventions in a naturalistic clinical setting using measurement-based care. The study was approved by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB), Los Angeles, California. Patients are evaluated using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [12]. The evaluations are performed by psychiatric residents, psychology interns, and social work interns who have undergone a course on the MINI and DSM-IV diagnoses. Each interview is monitored by a psychiatrist through a one-way mirror. Since the MINI does not have personality disorder modules (except for antisocial personality disorder), personality disorders are diagnosed clinically by employing DSM-IV criteria. Final diagnoses are confirmed using consensus techniques by a team led by a senior faculty member. Patient-reported outcomes consisting of self-report measures of depressive and anxiety symptom severity, functioning, and QOL (as detailed in the next section) are collected at baseline and then on a quarterly basis. All data are de-identified and entered into a secure database maintained by a data manager who monitors data completeness and integrity.

Data were collected and analyzed for 319 consecutive outpatients who had a primary DSM-IV diagnosis of MDD and presented for initial outpatient evaluation between 2005 and 2008. Data about prior episodes of MDD and current psychiatric comorbidities were collected along with demographic information.

Clinical measures utilized

The individual item scores were collected at the time of initial assessment for the following as detailed in Table 1:

-

1.

Symptom Severity measures: the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report (QIDS-SR) [13] for depressive symptoms, wherein the severity of MDD depressive symptoms was categorized based on the QIDS-SR scores as detailed by Rush et al. [13]: remission (score 0–5), mild (score 6–10), moderate (score 11–15), severe (score 16–20), or very severe (score > 20). We also used the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [14] for anxiety symptoms;

-

2.

Functioning measures: Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) [15], Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) [16], Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) [17], and the Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS) [18]; and

-

3.

Quality of Life measure: Quality of Life, Enjoyment, and Satisfaction Questionnaire—Short Form (Q-LES-Q) [18]. This self-report measure contains 16 items, each rated on a 5-point scale (1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = fair, 4 = good, and 5 = very good) during the past week. In the first 14 items, the patient rates his or her satisfaction with physical health, mood, work, household activities, social relationships, family relationships, leisure time activities, ability to function in daily life, sexual drive/interest/performance, economic status, living/housing situation, ability to get around physically, vision, and overall sense of well-being. The total score is calculated and converted to a percentage where 100 would be the best score and 0 is the worst. Q-LES-Q score calculation and interpretation are detailed in Table 1. Q-LES-Q has an internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.90 and test–retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient) of 0.86 in the community norm sample [19]. Patients with scores less than 10 % of the community norm (mean = 78.3 %, SD = 11.3), that is scores less than 70.5 %, are considered to have quality of life impairments [7, 19]. Patients with scores of 2 or more standard deviations below the community norm, that is scores less than 55.7 %, are considered to have severe impairment in QOL [7].

Data analysis

The raw data were assessed for normality of distribution (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test). Means and standard deviations were computed for all the measures. A Student’s t test or an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s Studentized Range (HSD) test for multiple comparisons was used to examine differences in the clinical measures across groups. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were employed to determine the correlations between total scores of the Q-LES-Q, QIDS-SR, BAI, GAF, SDS, WSAS, and EWPS. Linear regression analysis was performed to investigate the relationship between QOL, depressive symptom severity, and functioning measures. Forward step-wise selection procedures were used to select the variables with the greatest prognostic value of QOL scores, and only variables with a p < 0.15 in univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the multivariable model. Semi-partial correlation coefficients were calculated to examine how much each factor individually accounted for QOL impairment. All results were considered significant where p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS v9.1 computer software package (SAS Institutes Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

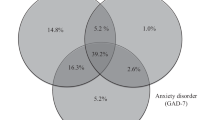

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 2. Subjects were predominantly women (n = 221, 67 %), Caucasian (n = 219, 69 %), and experiencing recurrent MDD (n = 245, 77 %) with a mean age of 44 years (SD = 16). Approximately half of the sample subjects were employed (n = 148, 46 %), and almost half of the sample had psychiatric comorbid diagnoses (n = 156, 49 %).

The mean Q-LES-Q score for this study population was 39.8 % (SD = 16.9), a value presenting greater than two standard deviations below the community norm mean of 78.3 % (SD = 11.3). The mean QIDS-SR was 15.4 (SD = 5.3), indicating a moderate severity level of MDD. The mean scores for the clinical measures appear in Table 3.

Impact of demographic factors on QOL in MDD

No sex differences were noted in any of the measures. However, ethnicity was a significant predictor of Q-LES-Q, QIDS, and SDS scores: these findings were primarily due to the increased levels of symptom severity and functional and QOL impairments reported by Hispanic and Asian subjects. An ANOVA to compare clinical measures across racial groups showed that race was a significant predictor in Q-LES-Q (p < 0.001), QIDS (p = 0.009), and SDS (p = 0.039). A forward step-wise regression of Q-LES-Q scores was performed, and least square means of Q-LES-Q scores by race were generated, revealing that Hispanics have significantly lower Q-LES-Q score than “others” and whites, after adjusting for other covariates. No other significant differences exist between racial categories as detailed in Table 4. In terms of employment status, subjects not currently working were significantly older and had significantly lower/worse Q-LES-Q and GAF scores, with higher/worse BAI, SDS, and WSAS scores as detailed in Table 5.

Impact of clinical characteristics on QOL in MDD

There were no significant differences in any of the symptom severity, functioning, or QOL measures when dichotomized by the presence or absence of psychiatric comorbidities, or by recurrent versus single episode of MDD. As detailed in Table 6, patients with comorbid DSM-IV-diagnosed anxiety disorders had statistically significant higher BAI scores (p = 0.03), but did not differ on the rest of the measures. However, when patients were dichotomized employing a BAI score of greater than or equal to 16 (reflecting moderate to severe anxiety according to Beck and Steer [20]) to identify patients with anxious depression [21], increased symptoms of anxiety had a profound negative impact on all of the measures of QOL, functioning, and work productivity.

Impact of depressive symptom severity on QOL

There were statistically significant differences in mean QOL scores between all of the various groups of depression severity, as measured by the QIDS-SR, highlighting the strong association between symptom severity and QOL. The mean Q-LES-Q score for patients in remission was 72.5 (SD = 11.8), as compared to 54.2 (SD = 11.8) in mild, 45.2 (SD = 11.4) in moderate, 34.4 (SD = 12) in severe, and 23.2 (SD = 11.4) in very severe MDD (Table 7). Additionally, BAI scores increased with increased depression symptom severity.

The relationship between symptoms, functioning, and QOL in MDD

Pearson’s correlations were calculated to examine the relationships between the symptom measures, measures of functioning and work productivity, and QOL (Table 8). The QIDS-SR, BAI, SDS, and WSAS all were positively correlated with one another (r range, 0.451–0.78). The Q-LES-Q was negatively correlated with all four of these measures (r range, −0.74 to −0.448), an expected and plausible finding. The EWPS was positively correlated with the QIDS-SR, BAI, SDS, and WSAS (r range: 0.38–0.50).

Linear regression analyses were used to further investigate the relationship between Q-LES-Q, demographic variables, clinical measures, and functioning measures. The results are shown in Table 9. In the unadjusted analysis, QIDS-SR, BAI, GAF, SDS, and WSAS were all significant predictors of Q-LES-Q scores (p < 0.01 for all). In total, the adjusted regression model describes a significant portion of the variance of Q-LES-Q score (r2 adj = 0.638). Measures of depressive symptoms severity (QIDS-SR) and measures of functioning/disability were highly predictive of Q-LES-Q scores. QIDS-SR, GAF, and SDS scores accounted for 48.1, 17.4, and 13.3 % (partial correlation values) of the variance in Q-LES-Q, respectively (Table 9).

We also performed an item analysis to determine whether specific aspects of QOL impairment were driving the overall low Q-LES-Q scores for our patients. The overall sample scored the lowest on satisfaction with work, followed by sexual drive, interest, and/or performance. They also scored almost as low on the mood, economic status, and overall well-being items. An item-by-item listing of Q-LES-Q scores from our sample appears in Table 10 alongside the community norm sample [18].

Discussion

This sample of subjects seen in an academic community hospital outpatient program has demographic and clinical characteristics that are typical of what is observed in most outpatient settings [9]. One of the unique features of this clinical sample of patients is the range of severity of depressive symptoms. Some patients were in remission but entered the clinic in order to receive ongoing medication follow-up, while others were un-medicated subjects requesting initial assessment and care. In general, the patients were moderately depressed and had significant functioning impairments as demonstrated by GAF, SDS, and WSAS scores and work productivity impairments as evidenced by EWPS scores. The mean QOL for this clinical sample of 39.8 % on the Q-LES-Q is not only substantially lower than the mean score of 78.3 % (SD = 11.3) for the normal population [7, 19] (where normal limits are within 10 % of community norms, i.e., above 70.5 %), but also represents a value greater than two standard deviations below the community norm mean (i.e., values below 55.7 %) similar to what has been reported in research populations [7]. Our findings are consistent with other studies showing significant impairment of QOL in MDD such as the US STAR*D trial [6], the European FINDER study [22], and another International 6-country study [23]. The mean Q-LES-Q score for our study population is similar to that observed in the STAR*D study [6, 24, 25].

The literature investigating potential sex differences in MDD is quite extensive, but the literature investigating differences in QOL is sparse [26]. We did not find any differences in the measures of QOL, functioning, or symptom severity based on sex. Additionally, when we performed an item-by-item comparison with the Q-LES-Q short form, we observed no statistical or clinically significant differences between women and men.

While we did not find any statistically significant differences in mean outcome measures among genders, we did find some with age and ethnicity. In our clinical sample, older and Hispanic patients had lower QOL ratings, which is consistent with previous studies [6, 24, 25].

In terms of recurrent depression versus first episode, we found that individuals with recurrent depression were less likely to be employed, but did not differ from individuals presenting with their first episode of MDD on depressive symptom severity, level of anxiety, QOL impairment, or any measures of functional impairment. These findings challenge the widely held clinical dictum that the initial episode of depression is less severe, less functionally impairing, and causes less of a detriment to QOL than recurrent illness, suggesting that the actual severity of episodes, measured with a multidimensional approach, is similar for single versus recurrent MDD, while the impact of recurrent episodes in itself may be reflected by the differences in employment rates. Since our sample did include a small percentage of patients who came for an initial evaluation on psychotropic medications or with recent treatment history, it is always possible that these interventions had a mitigating effect on symptom severity, QOL, or functional impairments.

We did not discern a significant difference on QOL measures for individuals presenting with comorbid DSM-IV-diagnosed psychiatric disorders versus those without psychiatric comorbidity, especially with regard to the impact of comorbid anxiety disorders on QOL. Fava et al. [21, 27] have repeatedly reported that depressed patients (and subjects) with higher ratings of anxiety, usually assessed on the anxiety subscale of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, tended to be less responsive to treatment, suggesting a rough treatment ride for those with anxiety present at baseline. The presence of a DSM-IV-diagnosed comorbid anxiety disorder did not impact the scores of Q-LES-Q, QIDS-SR, or WSAS. As expected, individuals with comorbid anxiety disorders did have significantly higher BAI scores than subjects with MDD only. However, when individuals are classified based on the severity of their baseline anxiety into those subjects with “anxious” depression and those without anxious depression, individuals with anxious depression have significantly worse scores on all measures of QOL, symptom severity, and functioning.

Our data demonstrate that impairment in QOL is significantly correlated with impairment in functioning. QOL as measured by the Q-LES-Q is moderately correlated with GAF scores and more highly and inversely correlated with SDS and WSAS scores. Q-LES-Q scores were also inversely correlated with EWPS scores.

In order to fully investigate the relationship between QOL impairment, demographic and clinical variables, and measures of functioning and work productivity, we performed a step-wise linear regression analysis. Our model showed that the QIDS-SR scores (depressive symptom severity) accounted for 48.1 % of the variance in Q-LES-Q scores (QOL), raising doubt that poor QOL in MDD is driven solely by depressive symptom severity. This is consistent with Q-LES-Q studies in research subjects with MDD which showed that illness-specific symptoms account for even less variance in Q-LES-Q scores [7]. Moreover, a number of studies investigated the determinants of QOL for patients with MDD using alternative QOL instruments [28–34]. These studies employed the WHO’s Quality of Life Instrument Short Version (WHOQOL-BREF) [35]. The majority of publications report relationships between specific WHOQOL domains and determinants of QOL. Although the amount of variance in specific domains of the WHOQOL-BREF may vary both based on the specific domain and the specific study, the overall findings suggest that symptom severity, socio-demographic data, self-esteem, response styles, and strength of social network can only account for a small-to-moderate amount of variance in the WHOQOL-BREF and its domain scores [28–30].

The impact of the range of severity of depression on QOL revealed that, as measured by the Q-LES-Q, QOL scores ranged from 72.5 % (SD = 11.8) in patients in remission to 23.2 % (SD = 11.4) in very severe MDD. These data do agree with both the work of Kessler [36] and Maier [37] and suggest that there is a gradient of impairment in QOL that increases with the severity of depressive symptoms, which accounted for 48.1 % of the variance in Q-LES-Q. Moreover, functioning uniquely played a significant role in QOL impairment with the GAF accounting for 17.4 % and the SDS for 13.3 % of the variance in Q-LES-Q.

We also investigated which Q-LES-Q items might be responsible for influencing QOL scores for patients with MDD. For the entire sample, the five items associated with greatest impairment included work, sexual drive, mood, economic status, and overall sense of well-being. These five items were consistently the items with greatest dysfunction throughout the range of severity of depressive disorder. This is consistent with the items rated lowest from the Rapaport study that included research subjects with MDD [7]. The item-by-item display in Table 10 also shows the wide discrepancy between patients with MDD and the community norm sample scores.

There are always limitations to research performed in clinical settings. This cross-sectional examination of the demographic and clinical characteristics is just a beginning, and we plan to analyze the quarterly data and use these results in future follow-up studies. Another potential criticism of this work is that medical comorbidities were not carefully ascertained for these individuals; we do not know the impact that medical comorbidity may have on our findings. Yet, this is a relatively young sample seeking outpatient psychiatric treatment; hence, it is less likely that this omission was of great significance given this patient population. Although it is true that we did not systematically collect education and socioeconomic data in this study, our clinic cares for a wide range of patients extending from a sliding scale through Medicare to most major insurers, with the majority of subjects having some type of insurance coverage. Other limitations include the possibility that self-reported ratings might differ from clinician-rated measures; however, a significant number of studies demonstrated a high correlation between self-reported and clinician-rated measures. Despite the fact that this sample was drawn from an urban hospital-based psychiatric clinic, the findings could be relevant to patients seen in the inpatient setting, partial hospital setting, or high-end fee-for-service private practice settings as well, given the range of severity, functioning, QOL, diversity of comorbidities, and demographic factors associated with our sample. A final caveat is that we did not include information about the age of onset, total duration of illness, medication, or psychotherapy trials, nor lifetime comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. Inclusion of these variables certainly might have led to a more elegant analysis, but their omission should not adversely skew our data. We believe that a unique aspect of this study lies in the fact that it examines data extracted from a clinical sample with no selection criteria; this more closely mirrors what clinicians typically see in an outpatient practice. Moreover, the detailed data on the 319 MDD patients could enable the readers to compare and contrast the ratings presented in this article with their own patients or research subjects.

Conclusions

This study provides significant details of patient-reported measures of depressive symptoms, anxiety level, functioning, work productivity, and QOL in individuals with MDD seeking treatment in a typical outpatient setting using measurement-based care. Clinical variables commonly thought to adversely impact QOL and functioning such as recurrence of depression and comorbidity were not associated with greater dysfunction, nor did we observe any gender difference in our findings. Age and ethnicity seem to have an effect on QOL with older and Hispanic individuals having lower QOL. Additionally, both increasing levels of depressive symptom severity and increasing levels of anxiety were associated with poorer QOL, functioning, and work productivity outcomes. In our regression models, depressive symptom severity only accounted for 48.1 % of the variance in QOL. Since the restoration of QOL or overall well-being is the ultimate goal in health care, in general and in MDD in particular [38], it is clear that focusing solely on symptom severity in treating or researching MDD is not sufficient. Our study showed that functioning/disability as measured by the GAF and SDS also accounted for some of the variance in QOL. Additional research should be conducted to identify other contributors to QOL impairment in MDD.

Although further work supporting our findings is necessary, we believe these results demonstrate the need to utilize not only Symptom Severity scales, but also Functioning and Quality of Life measures in major depressive disorder treatment and research.

Abbreviations

- BAI:

-

Beck Anxiety Inventory

- CS-PTR:

-

Cedars-Sinai Psychiatric Treatment Outcome Registry

- EWPS:

-

Endicott Work Productivity Scale

- GAF:

-

Global Assessment of Functioning

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- QIDS-SR:

-

Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report

- Q-LES-Q:

-

Quality of Life, Enjoyment, and Satisfaction Questionnaire—Short Form

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- MDD:

-

Major Depressive Disorder

- SDS:

-

Sheehan Disability Scale

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WSAS:

-

Work and Social Adjustment Scale

References

Constitution of the World Health Organization. (1946). American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health, 36(11): 1315–1323.

Bonicatto, S. C., Dew, M. A., Zaratiegui, R., Lorenzo, L., & Pecina, P. (2001). Adult outpatients with depression: Worse quality of life than in other chronic medical diseases in Argentina. Social Science and Medicine, 52(6), 911–919.

Papakostas, G. I., Petersen, T., Mahal, Y., Mischoulon, D., Nierenberg, A. A., & Fava, M. (2004). Quality of life assessments in major depressive disorder: A review of the literature. General Hospital Psychiatry, 26, 13–17.

Doraiswamy, P., Khan, Z. M., Donahue, J., & Richard, N. E. (2002). The spectrum of quality-of-life impairments in recurrent geriatric depression. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences., 57A, M134–M137.

Saarijarvi, S., Salminen, J. K., Toikka, T., & Raitasalo, R. (2002). Health-related quality of life among patients with major depression. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 56(4), 261–264.

Trivedi, M. H., Rush, A. J., Wisniewski, S. R., Warden, D., McKinney, W., Downing, M., et al. (2006). Factors associated with health-related quality of life among outpatients with major depressive disorder: A STAR*D report. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(2), 185–195.

Rapaport, M. H., Clary, C., Fayyad, R., & Endicott, J. (2005). Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1171–1178.

Rush, A. J., & Trivedi, M. H. (1995). Treating depression to remission. Psychiatric Annals, 25, 704–709.

Zimmerman, M., Mattia, J. I., & Posternak, M. A. (2002). Are subjects in pharmacological treatment trials of depression representative of patients in routine clinical practice? American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 469–473.

Angst, J., Kupfer, D. J., & Rosenbaum, J. F. (1996). Recovery from depression: Risk or reality? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 93, 413–419.

Rapaport, M. H. (2009). Helping patients with depression achieve wellness. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70(5), e11.

Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., et al. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl 20), 22–33; quiz 34–57.

Rush, A. J., Trivedi, M. H., Ibrahim, H. M., Carmody, T. J., Arnow, B., Klein, D. N., et al. (2003). The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): A psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biological Psychiatry, 54(5), 585.

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893–897.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Global Assessment of Functioning in diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.

Sheehan, D. V. (1983). The anxiety disease. New York, NY: Scribner’s.

Mundt, J. C., Marks, I. M., Shear, M. K., & Greist, J. H. (2002). The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 461–464.

Endicott, J., Nee, J., Harrison, W., & Blumenthal, R. (1993). Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: A new measure. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 29, 321–326.

Schechter, D., Endicott, J., Nee, J. (2007). Quality of life of ‘normal’ controls: Association with lifetime history of mental illness. Psychiatry Research, 30 152(1):45–54.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1990). Beck Anxiety Inventory manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Fava, M., Rush, A. J., Alpert, J. E., Balasubramani, G. K., Wisniewski, S. R., Carmin, C. N., et al. (2008). Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: A STAR*D report. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(3), 342–351.

Reed, C., Monz, B. U., Perahia, D. G., Gandhi, P., Bauer, M., Dantchev, N., et al. (2009). Quality of life outcomes among patients with depression after 6 months of starting treatment: Results from FINDER. Journal of Affective Disorders, 113(3), 296–302.

Fleck, M., Simon, G., & Herrman, H. (2005). Major Depression and its correlates in primary care settings in six countries. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186(1), 41–47.

Wisniewski, S. R., Rush, A. J., Bryan, C., Shelton, R., Trivedi, M. H., Marcus, S., et al. (2007). Comparison of quality of life measures in a depressed population. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(3), 219–225.

Daly, E. J., Trivedi, M. H., Wisniewski, S. R., Nierenberg, A. A., Gaynes, B. N., Warden, D., et al. (2010). Health-related quality of life in depression: A STAR*D report. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 22(1), 43–55.

Piccinelli, M., & Wilkinson, G. (2000). Gender differences in depression. Critical review. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 486–492.

Fava, M., Alpert, J. E., Carmin, C. N., Wisniewski, S. R., Trivedi, M. H., Biggs, M. M., et al. (2004). Clinical correlates and symptom patterns of anxious depression among patients with major depressive disorder in STAR*D. Psychological Medicine, 34(7), 1299–1308.

Berlim, M. T., McGirr, A., & Fleck, M. P. (2008). Can sociodemographic and clinical variables predict the quality of life of outpatients with major depression? Psychiatry Research, 160(3), 364–371.

da Rocha, N. S., Power, M. J., Bushnell, D. M., & Fleck, M. P. (2009). Is there a measurement overlap between depressive symptoms and quality of life? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 50(6), 549–555.

Gureje, O., Kola, L., Afolabi, E., & Olley, B. O. (2008). Determinants of quality of life of elderly Nigerians: Results from the Ibadan study of ageing. African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, 37(3), 239–247.

Moore, M., Hofer, S., McGee, H., & Ring, L. (2005). Can the concept of depression and quality of life be integrated using a time perspective? Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 3–11.

Ritsner, M. (2007). The distress/protection vulnerability model of quality of life impairment syndrome. In M. Ritsner & A. G. Awad (Eds.). Quality of life impairment in schizophrenia, mood, and anxiety disorders (pp. 3–19). The Netherlands: Springer.

Bech, P. (1995). Quality-of-life measurements for patients taking which drugs? The clinical PCASEE perspective. Pharmacoeconomics, 7(2), 141–151.

Yen, C. F., Chen, C. C., Lee, Y., Tang, T. C., Ko, C. H., & Yen, J. Y. (2009). Association between quality of life and self-stigma, insight, and adverse effects of medication in patients with depressive disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 26(11), 1033–1039.

Skevington, S. M., Lotfy, M., O’Connell, K. A., & WHOQOL Group. (2004). The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Quality of Life Research, 13, 299–310.

Kessler, R. C., Zhao, S., Blazer, D. G., & Swartz, M. (1997). Prevalence, correlates, and course of minor depression and major depression in the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Affective Disorders, 45, 19–30.

Maier, W., Gansicke, M., & Weiffenbach, O. (1997). The relationship between major and subthreshold variants of unipolar depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 45, 41–51.

IsHak, W. W., Greenberg, J. M., Balayan, K., Kapitanski, N., Jeffrey, J., Fathy, H., et al. (2011). Quality of life: The ultimate outcome measure of interventions in major depressive disorder. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 19, 229–239.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Psychiatry residents, trainees, staff, and faculty for their exceptional work with patients over the years, and for their contributions in building and maintaining the psychiatric treatment outcome registry cited in this work. The authors would also like to thank Ms. Gitta Morris for her exceptional help during the various stages of development of this manuscript. This research was supported by NARSAD Young Investigator Award Grant#CSMC215387 (Dr. IsHak) and by NIMH Grant#R01 MH073765 (Dr. Rapaport, Polier Endowed Chair in Schizophrenia and Related Disorders). Dr. IsHak received research support from NARSAD, Pfizer (ziprasidone monotherapy for major depression). Dr. Rapaport received research support from NIMH and NCCAM, and is an unpaid consultant for Pax Neuroscience.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Greenberg, Ms. Bresee, Dr. Balayan, Dr. Fakhry, and Mr. Christensen report no conflict of interest and have no relevant financial disclosure to report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

IsHak, W.W., Balayan, K., Bresee, C. et al. A descriptive analysis of quality of life using patient-reported measures in major depressive disorder in a naturalistic outpatient setting. Qual Life Res 22, 585–596 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0187-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0187-6