Abstract

Purpose

To validate the FACT-G scale for measuring quality of life of patients with cancer in Colombia.

Methods

The analysis included factor analysis, confirmatory analysis, Rasch analysis, convergent validity, internal consistency (473 patients diagnosed with cancer), test–retest reliability (97 patients evaluated at two different time points) and sensitivity to change (25 patients evaluated before and after an intervention).

Results

A four-factor structure has been found (“Physical well-being”, “Social–family well-being”, “Functional well-being” and “Emotional well-being”). Two subscales (“Emotional well-being” and “Social–family well-being”) have misfitting items. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 for the whole scale. None of the items had significant impact on the scale’s alpha when removed. Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient indicated test–retest reliability (rho c: 0.64–0.76) adequate to the uses of the tool. Regarding sensitivity to change, repeated measures analysis demonstrated significant change of the score after an intervention [F(3, 72) = 39.89, P = 0.000]. Except for the domain “Social–family well-being”, Pearson’s correlation coefficient between equivalent domain scores on FACT-G and the EORTC QLQC-30 ranged from 0.5 to 0.7.

Conclusions

The FACT-G scale measures a four-factor construct. Results indicate that the FACT-G scale is an instrument that performs consistently over time, with evidence of responsiveness. The finding of misfitting items in two subscales (“Social–family well-being”, and “Emotional well-being”) imposes caution in interpreting the scores of these domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Concepts like health state, functional state and quality of life have been used indiscriminately by the different methods that have attempted to measure the health-disease state. However, such concepts reflect different phenomena: [1]. Health state is related to the presence of observable signs or symptoms that can be grouped under the same reference pattern. Functional state refers to how the health state affects aspects related to subject’s performance and his autonomy, while quality of life is a broader and subjective concept since it takes into account physical, psychological, spiritual and emotional well-being, as well as the ability to function properly in daily life activities. [2]. When the purpose is to evaluate how disease situations, and therapeutic and diagnostic procedures affect quality of life, we are dealing with “health-related quality of life”. This term first used by Cella and Tulsky [3] measures the discrepancy between the patient’s actual health state and the ideal functioning, satisfaction and well-being state. However, this evaluation is strictly subjective, since it has been demonstrated that people with identical levels of lesion or with very similar signs and symptoms register different levels of quality of life [4].

The use of quality of life as an outcome measure in different kinds of clinical trials has increased; for example, it is the most frequently measured outcome in clinical trials involving patients with cancer or cardiovascular pathologies. In the case of cancer, this variable has been identified as the second most important primary outcome after survival [5].

Diverse instruments have been employed to evaluate health-related quality of life in patients with cancer including generic questionnaires as Short Form 36 (SF-36) [6] and specific measures; in this group, the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) [7] and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) [8] questionnaires have been the most used in clinical research of this kind of pathology.

The FACT questionnaire is designed to be self-administered although it can be applied in the form of an interview. Its pool of items has been generated using semi-structured interviews of patients and health professionals. A factor analysis of a preliminary version having 28 items showed five domains: (1) general physical health state (related to physical well-being and some symptoms); (2) family and social environment (includes items exploring emotional support from family and friends and communication about the illness): (3) emotional state (evaluates some emotional symptoms and coping with the illness); (4) personal functioning capacity (includes items exploring functional well-being, acceptance of the illness and an overall evaluation of the quality of life) and relationship with the doctor. In the most recent Spanish version 4, the last domain having two items has been removed from the scale and a new item (“Me preocupa que mi enfermedad empeore” has been added [9].

The instrument has a simple scoring system, in which each of the 27 items is evaluated in an ordinal dimension from 0 to 4, using a 5-point rating scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much”. Higher scores indicate better quality of life. The scale uses the past 7 days as timescale. The measure yields information about total quality of life as well as the four dimensions listed previously [9]. Different attempts to validate the FACT-G questionnaire have been made in different countries [10–14]; these studies have reported adequate reliability and consistent factorial structures. Comparability with other instruments as the EORTC QLQ C30 has been established in such a way that schemes for converting scores from one instrument into the other have been proposed [15].

The instrument, originally in an English version, was translated into Spanish using an iterative forward–backward sequence, having a review by bilingual health professionals [16]. A subsequent adaptation into Spanish has been made using an extension of the method described by Bravo et. al [17]. In this adaptation, different cultural backgrounds have been included (Puerto Rico, Cuba, Mexico, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Argentina and Peru). This version appeared to perform at least as well as the original English instrument having comparable reliability and validity coefficients [9, 18] although some misfitting items belonging to emotional well-being and social–family well-being domains have been identified [19]. A study performed among Uruguayan patients with cancer showed acceptable to good reliability except for the emotional well-being domain [18]. Another study of Dupueto et al. [20], using the FACT-G Spanish version 4 among Uruguayan patients, reported good reliability and validity of the QOL instrument among this population, appearing to be an instrument capable of discriminating among groups of patients and having Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.78 to 0.91 in the four subscales. Since up to the moment, there are no records on the validation of the FACT questionnaire in Colombia, and to our knowledge, there are no more psychometric studies on FACT-G for Spanish-speaking patients having cancer in South America (except by the validation among Uruguayan patients). The aim of the present study was to determine the measurement characteristics of this instrument applied to patients with cancer in Colombia.

Materials and methods

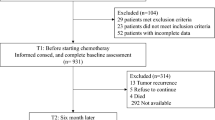

FACT-B Spanish Version 4 scale was initially applied to 473 patients with different types of cancer attending Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC) ambulatory care services in Bogotá, Colombia. This sample was used to perform an exploratory factor analysis, a confirmatory analysis, an evaluation of an item response theory (IRT) measurement model and to assess internal consistency and convergent validity (for this purpose, the EORTC QLQ C30 scale was simultaneously applied to this group of 473 patients) (see Table 1). Respondents filled out the questionnaire with the assistance of a research auxiliary trained in the implementation of the instrument.

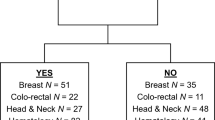

The evaluation of the test–retest reliability comprised application of the instrument repeatedly, in two opportunities, to a group of 97 patients. To evaluate the instrument sensitivity to change, the scale was applied in two opportunities to a group of 25 patients with breast cancer that had received treatment. Patients included in the groups to evaluate test–retest reliability and sensitivity to change were a subsample of the total amount of 473.

Statistical analysis

An exploratory factor analysis has been performed in the sample of 473 patients to obtain information about loadings of the items for each domain, via factor analysis of ordinal variables using LISREL 8.80 [21]. Eigenvalues higher than 1, Barlett’s test and Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test were used as extraction strategy. A promax rotation was used to achieve a more understandable structure among factors.

A confirmatory factor analysis was applied to the sample of 473 patients using LISREL 8.80. Considering the ordinal nature of the item-scores as a Likert-type scale, estimation methods using polychoric correlation and asymptotic covariance matrices were performed. These matrices were generated using PRELIS, the LISREL preprocessor [22]. Three models were used to fit the data: a model having four factors, corresponding to the original structure of the FACIT-G Spanish Version 4 (four factors in which each item loaded on only one factor, with correlations between them freely estimated), and two additional models constructed taking into account the information yielded by a factor analysis of ordinal variables and by the modification indexes generated by LISREL. The models were analyzed using diagonally weighted least squares as method of estimation, assuming non-normally distributed data. Decisions on model fit were made using the following criteria: the ratio of χ 2 to degrees of freedom (χ 2/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), non-normed fit index (NNFI), comparative fit index (CFI), goodness of fit index (GFI) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). χ 2/df < 3 indicates model adequacy. NNFI and CFI > 0.9 suggest good model fit. RMSEA < 0.08 is considered acceptable [23]. SRMR < 0.08 indicates a good fit of the model.

A Rasch analysis was performed to evaluate person and item reliability, item fit statistics and rating scale diagnostics using average measures and fit statistics. Person and item reliability indexes have values analogous to Cronbach’s alpha (bounded by 0 and 1). Person and item separation indexes should be at least 2 in order to be good indicators of separation. Two item fit statistics have been computed: the infit (weighted) and the outfit (unweighted) statistics; these statistics indicate construct homogeneity and item redundancy [24]. Items having infit or outfit >1.4 and corresponding values of ZSD > 2.0 are considered misfitting; item redundancy is indicated by infit–outfit values <0.6 [25]. The rating scale diagnostics included average measures, outfit–infit mean squares and thresholds (step measures). Rasch analysis was carried out with Winsteps software [26], using the partial credit model for polytomous data.

The internal consistency of factors and their items was analyzed using the Cronbach’s alpha statistics (where values greater than 0.7 are considered acceptable). For test–retest analysis (N = 97) and concurrent validity analysis (N = 473), the sample size achieves a power greater than 88% to detect a difference of 0.15 between a null hypothesis correlation of 0.65 and the alternative hypothesis correlation of 0.8 using a two-sided hypothesis test with a significance level of 0.05.

A sample size of 25 patients was calculated for assessing sensitivity to change, expecting a 5-point difference in mean domain scores and a standard deviation of five. Measurements of central tendency, dispersion and frequency were calculated in order to characterize the different items measured by the instrument. A sample of equal or larger size than the one calculated for each procedure was considered in all phases.

Consistency between repeated measurements with the same instrument (test–retest reliability) was estimated using Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient (ρc) [27]. The instrument sensitivity to change for variations in the clinical condition was determined using a repeated measure ANOVA. Descriptive scale and classical test theory analysis were carried out using Stata®, using a significance level of 5% for testing all hypotheses. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics committee of the National Cancer Institute of Colombia (approval number 19, September 29 2004). All patients provided informed consent.

Results

The following scores were obtained for the different subscales: Physical well-being state, mean = 21.7 (±6.2); Social/family well-being, mean = 18.8 (±5.8); Emotional well-being, mean = 20.1 (±5.6); Functional well-being, mean = 17.5 (±6.2). The range of the different subscales varied between 0 and 28, except for the emotional state scale which varied between 2.3 and 24.

Exploratory factor analysis

Data were analyzed through exploratory factor analysis using as extraction strategy the results of Barlett’s test of sphericity (χ 2 = 3593.2(351), P = 0.000) and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test (KMO = 0.89). The number of factors to be analyzed was determined through a graphic analysis of a scree plot and a very simple structure analysis [28], obtaining an optimum number of four factors with both methods. In addition, an oblique rotation (Promax) was carried out. Bearing in mind the interpretability of domains as the main criteria, oblique rotation was the most appropriate solution for the factor analysis. All of the items have meaningful loadings on the four domains (greater than 0.3) [29]. The factorial pattern matches the original structure of FACT-G: four domains corresponding to physical, social–family, emotional and functional well-being. The rotated solution is shown in Table 2: the 27 items load on the theoretical factors, except for the group related to emotional well-being: two items, “I am satisfied with how I am coping with my illness” and “I am losing hope in the fight against my illness” have better loadings on the “Functional well-being” and “Physical well-being” domains, respectively. Correlations of factors have values between 0.14 (social–family well-being, emotional well-being) and 0.56 (social–family well-being, functional well-being).

Confirmatory factor analysis

Table 3 shows the results of the confirmatory analyses of two models. Model 1 corresponds to the four-factor first-order structure of the FACIT-G Spanish Version 4. Model 2 includes a modification of Model 1 suggested by the exploratory factor analysis: in this new structure, the item ge2:“I am satisfied with how I am coping with my illness”, loads on factor 4 (Functional well-being), and the item ge3 (“I am losing hope in the fight against my illness”) loads on factor 1 (Physical well-being).

Both of the models have significant coefficients with small standard errors and t-ratios; in addition, they have theory corresponding signs suggesting a good fit of internal structure [30]. Although these models are broadly similar, and approach a good fit, some small differences are apparent: Only model 2 passes the χ 2/df test. Model 2 has the lower RMSEA and SRMR. It also has the higher CFI. The changes suggested by the MI do not improve fit significantly. Overall, these data support the four-factor model although some items of the emotional well-being factor could fit better if they were assigned to other domain. Figure 1 shows the characteristics of the model having the best fit (Model 2).

Item response theory

Analyses were made using Rasch models for polytomous scales. Table 4 shows overall information regarding model fit. These data suggest misfit for items (The standard deviation of the ZSTD infit is greater than 2). Table 5 presents the reliability and separation indices for persons and items corresponding to the four subscales. Reliability has values >0.65 for persons and >0.96 for items. Separation indexes show modest values for persons (only functional well-being subscale has a value greater than two), but adequate values for items. Low person reliability and separation indexes and high item reliability and separation indexes suggest a narrow spread of this sample.

Table 6 shows item infit and outfit statistics on the scale. Rasch analysis identifies misfit of two items of the Emotional well-being scale (ge5 and ge6) and of the Social–family well-being scale (gs3 and gs6). No item demonstrated redundancy.

Table 7 presents average measures and infit–outfit MNSQ. Values corresponding to average measures increase monotonically in an expected manner across the rating scales, suggesting that persons having higher measures rate higher in the items. Infit–outfit MNSQ values ranged between 0.70 and 1.67. Nearly all of infit–outfit MNSQ values are close to 1 except for categories “Not at all”—“A little bit” in the Social–family well-being scale: this suggests that patients having high scores in this subscale unpredictably choose low ratings.

In Fig. 2, the higher a patient is positioned on the vertical axis, the better in terms of quality of life. It can be seen that persons and items have high spread, covering a range of −2 to 5 logits. In addition, the person mean is about 1.2 logits higher than the item mean; this suggests that the construct the scale measures in this group is quantitatively superior than the one observed in a random sample of patients. Item ge3 (“I am losing hope in my fight against my illness”) is in the upper zone of the item map, suggesting that coping is a strong marker of quality of life in this sample. In contrast, items gs3 (“I get support from my friends”) and gsf (“I am satisfied with my sex life”) seem to be poor markers of this construct. In addition, the scale shows a gap between some symptoms (physical and emotional) and coping.

Internal consistency

Cronbach’s alpha for the total FACT-G score was 0.89. Cronbach’s alpha for the four subscales was 0.85 for the Physical well-being, 0.79 for the Social/family well-being, 0.85 for the Emotional well-being and 0.73 for the Functional well-being subscale. None of the items has a significant impact in the scale alpha when removed.

Validity of the convergent criteria

The validity of the convergent criteria was assessed in 473 patients, choosing EORTC QLQC-30 subscales having theoretical correspondence with FACIT scale: Physical functioning (5 items), social/family functioning (2 items), emotional functioning (4 items) and functional role (2 items). Values of correlations estimated between pairs of the contrasted subscales oscillated between 0.1 and 0.7 (Table 8).

Test–retest reliability

Ninety-seven patients were assessed for this step of the instrument evaluation. The time elapsing between the two assessments has a mean of 8 days (±3.8), varying between 2 and 20 days. Table 9 shows the results of measuring reliability for the subscales total scores. Concordance correlation coefficients had a range of 0.64–0.76.

Sensitivity to change

Twenty-five patients were assessed at two time points for this step of the instrument evaluation, before and after receiving therapeutic intervention. The time elapsed between both assessments has a mean of 179 days (±85.2), varying between 91 and 396 days. The mean scores for each of the subscales before and after the intervention are shown in Table 10. Although we expected to see a positive effect of the intervention on quality of life, it can be seen that changes in the scores are not pointing to the same direction for all subscales.

The initial and final score was different for each of the four subscales (P < 0.03). According to the results of the repeated measures ANOVA, such difference was explained by the time component.

Discussion

Although The FACT-G is among the most widely used instruments for measuring quality of life in patients with cancer, few studies have been performed for its validation in Latin America [18, 20]. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the FACT-P 4 when applied in a Colombian sample of patients with cancer.

The exploratory factor analysis provides support for the hypothesized underlying four-factor structure of the FACT-G. Although the structure of items loading does not match with the original theoretical composition of the scale, the relationships we found are plausible: The loading of item “I am satisfied with how I am coping with my illness” (ge2) on the functional domain makes sense considering that coping strategies have been associated with functional status [31]. Regarding item “I am losing hope in the fight against my illness” (ge3), its connection with the physical well-being domain could be explained by the relevance of perceived symptoms on the expectations about the illness outcome in this group of patients.

The confirmatory factor analysis also supports the proposed four-factor structure indicating that the FACT-G is a measure of several domains of quality of life in patients with cancer: symptoms, family/social, emotional and function. However, in this sample of South American Spanish-speaking patients, a factorial model having a better fit comes out when some items belonging to the “emotional well-being” domain are assigned to other subscales. Although this finding does not have an effect on the four-factor structure (fulfills the criteria of three or more factor loadings >0.4) [32], it suggests some limitation of the internal structure of the emotional subscale; difficulties with this subscale have been previously reported in samples of Spanish-speaking patients having cancer [18]. A possible explanation is that the difference in item wording of ge2 and ge3 introduces, in this sample of Colombian patients, an additional meaning related to factors as adaptation and functioning, and not merely the emotional aspect. Some of the autocorrelation structures suggested by the Modification Indexes seem plausible, but its impact in the factorial structure does not seem relevant taking into account that they do not modify loadings of items nor improve the fit of the original model.

Rasch analysis indicates that person reliability and separation have lower values than item reliability and separation, suggesting a narrow spread of the sample and probably a large sample size [33]. Although person reliability has acceptable values (ranging from 0.65 to 0.84), these scores could be increased if patients having less severe stages of cancer were included, therefore increasing sample variability (it should be noted that the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología is a reference cancer center in Bogotá and thus the sample could be biased). High values of item reliability indicate an adequate sample size for stable comparisons between items [34]. Considering the results of item statistics, two subscales, emotional well-being and family/social well-being, have items with misfit. In a previous study with European patients [19], two of these items have been identified as misfitting (gs6 and ge6). Items gs7 and ge2, included in emotional well-being and family/social well-being subscales, have been reported as misfitting in a study with South American patients with cancer [20]. In the Latin culture, where large extended family networks are predominant [35], friends and partners, included in items gs3 and gs6, could have less protagonism when support to a patient with cancer is needed; as a consequence, misfitting of these items could be related to this social characteristic of the Latin families. This could be also the explanation of why items located in the social/family domain are poor markers (or difficult items) when measuring quality of life. An additional explanation of the difficulty of item gs7 (“I am satisfied with my sex life”) could be the reluctance of many patients to give information about their sexual life. Furthermore, the misfit in the emotional subscale could be explained by the religious beliefs that, in Latin patients, seem to counteract fatalistic tendencies and to increase the sense of mastery and ability to cope with disease [36]. However, caution should be used when identifying problematic items, employing only Rasch methods [37]. Other scenarios and additional studies and methods should be employed before making decisions about modifications on these items. The gap shown in the scale suggests that additional items, probably related to coping abilities (as indicator of “easiest” item in FACT-G), could improve some psychometric properties of the scale. The rating scale functioning in this sample can be considered acceptable. The finding of high values of infit–outfit MNSQ in the Social and family well-being could be evidence for social desirability bias.

The internal consistency of the instrument, measured at an overall level and for each of the subscales, was found to be appropriate. However, this finding should be taken into account with caution considering that Cronbach’s alpha is an index having as limitation its tendency to increase as the number of items increases.

A comparison of the instrument versus a reference pattern showed an appropriate correlation between physical and emotional factors, but moderate between functional factors. It is worth noting that the domain related to social–family aspects had a poor correlation when being measured with the EORTC scale. This finding could be reflecting a different approach for measuring the same construct: while the FACIT scale encompasses seven items, measuring specific aspects related with friends, family and partners, the EORTC scale includes only two broad questions for measuring this aspect (Has your physical condition or medical treatment interfered with your family life?, Has your physical condition or medical treatment interfered with your social activities?). This lack of focus about explicit details could be generating a different approach to measuring this dimension. In other words, instead of reflecting a difference in the constructs measured, low correlation values could be due to high proportion of error in the measures.

Regarding the values of the correlation and concordance between successive assessments, being the patient under a stable clinical condition, the levels of reliability in the different domains suggest that the instrument performs consistently through time. Additionally, the scale seems to detect changes in different domains of the construct and shows an acceptable correlation with the reference pattern. It seemed interesting that the change in the clinical condition turned out to be indicative of improvement in the physical and emotional domains, and decline in the social–family and functioning domains. For it use in Colombia, this finding suggests that it would be more advisable to evaluate the scores of individual domains when applying the instrument, instead of the overall score. According to our findings, cultural invariance of some of the domains of the FACT-G 4 (social/family test–retest emotional) cannot be supported. The subscales where misfit has been identified are clearly influenced by social, cultural and geographical aspects; in contrast, domains related to symptoms and with functional abilities are more stable.

According to the result of this validation study, the FACT-G scale is a measure of a four-factor construct of quality of life in patients with cancer in Colombia. The analysis of the internal structure of the subscales indicates the existence of misfitting items in the social/family and emotional factors.

It should be noted, however, that not having included a sufficiently large number of patients with other types of cancer might compromise data generalization. The possibility of spectrum bias is an additional aspect that can affect the external validity of this study. Therefore, further research incorporating different types of patients to cover a broader spectrum of the disease is required in order to assess the instrument performance in different scenarios. Additionally, studies evaluating differential item functioning in a more representative sample of Colombian patients with cancer are recommended.

A remaining issue deals with the Spanish version that has been validated: the cultural adaptation of the instrument used in this study incorporated a Latin-American background sample that did not include Colombian patients. Although no major concerns about difficulties to understand the meaning of the items have been found during the application of the questionnaires, we cannot exclude the fact that the omission of a local process of cultural adaptation could be responsible for some of the limitations this instrument reveals.

References

Patrick, D. L., & Bergner, M. (1990). Measurement of health status in the 1990s. Annual Review of Public Health, 11, 165–183.

Leplege, A., & Hunt, S. (1997). The problem of quality of life in medicine. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(1), 47–50.

Cella, D. F., & Tulsky, D. S. (1993). Quality of life in cancer: Definition, purpose, and method of measurement. Cancer Investigation, 11(3), 327–336.

Testa, M. A., & Simonson, D. C. (1996). Assessment of quality-of-life outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine, 334(13), 835–840.

Frost, M. H., & Sloan, J. A. (2002). Quality of life measurements: A soft outcome—or is it? The American Journal of Managed Care, 8(18), S574–S579.

Bullinger, M. (1996). Assessment of health related quality of life with the SF-36 health survey. Rehabilitation (Stuttg), 35(3), 17–27. Quiz XXVII–XXIX.

Aaronson, N. K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., Bullinger, M., Cull, A., Duez, N. J., et al. (1993). The European Organization for Research and Treatment Of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85(5), 365–376.

Cella, D., & Nowinski, C. J. (2002). Measuring quality of life in chronic illness: The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy measurement system. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 83(12 Suppl 2), S10–S17.

Cella, D., Hernandez, L., Bonomi, A. E., Corona, M., Vaquero, M., Shiomoto, G., et al. (1998). Spanish language translation and initial validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy quality-of-life instrument. Medical Care, 36(9), 1407–1418.

Lee, E. H., Chun, M., Kang, S., & Lee, H. J. (2004). Validation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) scale for measuring the health-related quality of life in Korean women with breast cancer. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 34(7), 393–399.

Conroy, T., Mercier, M., Bonneterre, J., Luporsi, E., Lefebvre, J. L., Lapeyre, M., et al. (2004). French version of FACT-G: Validation and comparison with other cancer-specific instruments. European Journal of Cancer, 40(15), 2243–2252.

Costet, N., Lapierre, V., Benhamou, E., & Le Gales, C. (2005). Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy General (FACT-G) in French cancer patients. Quality of Life Research, 14(5), 1427–1432.

Thomas, B. C., Pandey, M., Ramdas, K., Sebastian, P., & Nair, M. K. (2004). FACT-G: Reliability and validity of the Malayalam translation. Quality of Life Research, 13(1), 263–269.

Fumimoto, H., Kobayashi, K., Chang, C. H., Eremenco, S., Fujiki, Y., Uemura, S., et al. (2001). Cross-cultural validation of an international questionnaire, the general measure of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale (FACT-G), for Japanese. Quality of Life Research, 10(8), 701–709.

Holzner, B., Bode, R. K., Hahn, E. A., Cella, D., Kopp, M., Sperner-Unterweger, B., et al. (2006). Equating EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G scores and its use in oncological research. European Journal of Cancer, 42(18), 3169–3177.

Bonomi, A. E., Cella, D. F., Hahn, E. A., Bjordal, K., Sperner-Unterweger, B., Gangeri, L., et al. (1996). Multilingual translation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) quality of life measurement system. Quality of Life Research, 5(3), 309–320.

Bravo, M., Canino, G. J., Rubio-Stipec, M., & Woodbury-Farina, M. (1991). A cross-cultural adaptation of a psychiatric epidemiologic instrument: The diagnostic interview schedule’s adaptation in Puerto Rico. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 15(1), 1–18.

Dapueto, J. J., Francolino, C., Gotta, I., Levin, R., Alonso, I., Barrios, E., et al. (2001). Evaluation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General questionnaire (FACT-G) in a South American Spanish speaking population. Psycho-oncology, 10(1), 88–92.

Smith, A. B., Wright, P., Selby, P. J., & Velikova, G. (2007). A Rasch and factor analysis of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G). Health Qual Life Outcomes, 5, 19.

Dapueto, J. J., Francolino, C., Servente, L., Chang, C. H., Gotta, I., Levin, R., et al. (2003). Evaluation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) Spanish Version 4 in South America: Classic psychometric and item response theory analyses. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 1, 32.

Jöreskog, K., & Sörbom, D. (2007). LISREL 8.80. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International.

Diamantopoulos, A., & Siguaw, J. A. (2000). Introducing Lisrel: A guide for the uninitiated. London: SAGE.

Hu, L. T. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

Linacre, J. M. (2002). Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. Journal of Applied Measurement, 3(1), 85–106.

Wright, B., & Linacre, M. (1994). Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 8(3), 370.

Linacre, J. M. (2005). User’s guide to winsteps. Chicago: Mesa Press.

Lin, L., & Torbeck, L. D. (1998). Coefficient of accuracy and concordance correlation coefficient: New statistics for methods comparison. PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology, 52(2), 55–59.

Revelle, W., & Rocklin, T. (1979). Very simple structure: An alternative procedure for estimating the optimal number of interpretable factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 14, 403–414.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2006). A first course in structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Porter, L. S., Keefe, F. J., Garst, J., McBride, C. M., & Baucom, D. (2008). Self-efficacy for managing pain, symptoms, and function in patients with lung cancer and their informal caregivers: associations with symptoms and distress. Pain, 137(2), 306–315.

Pett, M. A., Lackey, N. R., & Sullivan, J. J. (2003). Making sense of factor analysis: The use of factor analysis for instrument development in health care research. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Pub.

Wright, B., & Masters, G. N. (2002). Number of persons or item strata. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 16(3), 888.

Wright, B. D. (1998). Interpreting reliabilities. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 11(4), 602.

Vega, W. A. (1990). Hispanic families in the 1980s: Adecade of research. Journal of marriage and the family, 52, 1015–1024.

Florez, K. R., Aguirre, A. N., Viladrich, A., Cespedes, A., De La Cruz, A. A., & Abraido-Lanza, A. F. (2009). Fatalism or destiny? A qualitative study and interpretative framework on Dominican women’s breast cancer beliefs. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 11(4), 291–301.

Karabatsos, G. (2000). A critique of Rasch residual fit statistics. Journal of Applied Measurement, 1(2), 152–176.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez, R., Ballesteros, M. & Arnold, B.J. Validation of the FACT-G scale for evaluating quality of life in cancer patients in Colombia. Qual Life Res 20, 19–29 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9727-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9727-0