Abstract

International student mobility has assumed greater prominence in the last decades and has had a profound effect on policy decision-making in the academic education system of most countries. Actually, the number of students interested in spending part of their academic education abroad is steadily increasing. This is not surprising, given the large benefits that they receive from studying abroad in terms of intercultural competencies, as well as of quality in education, training and specialization. In the light of these considerations, the aim of this paper is to investigate the phenomenon of international student mobility by analyzing the main results of a web survey on a cohort of students that have experienced a period of study abroad. In particular, we explore latent dimensions of student profiles with regard to degree programme, field of study, geographical area and gender, and the impact of international mobility on improving students’ competencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the era of internationalization and globalization, competition is becoming higher and higher among economies and individuals, and consequently education needs to be characterized by globally accepted high academic standards, because the high level qualifications obtained by graduates in one country have to be accepted and recognized internationally as equivalent.

Therefore, governments are promoting measures aimed at both the adoption of internationally accepted high academic standards and the mobility of students. Mobility may contribute directly to the process of human capital formation acquired by young people migrating abroad and may also provide tangible economic effects, in both the destination and home countries (Agiomirgianakis and Asteriou 2001; Agiomirgianakis et al. 2004; Agiomirgianakis 2006).

In order to encourage the international academic experience, in 1999 the Bologna Process has proposed a common framework that would enable students to move freely within the European education area and study outside their home countries while obtaining full recognition for their qualifications. The overall aim of the Bologna Process is the harmonization of academic structures and the compatibility and comparability of quality assurance standards throughout Europe in conjunction with the breaking down of the existing educational borders, in order to make European higher education globally competitive.

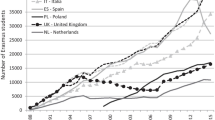

Within this framework, Erasmus (European Region Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students) is one of the oldest and most important measures promoted by the European Union to help students travel to other European countries. Since its institution in the 1987, the number of students involved in academic mobility through the Erasmus programme has substantially increased, moving from 1 million of students in the period 2002–2003 to 2 millions in 2008–2009, and to 3.3 millions in the 2013–2014.Footnote 1

Given the increasing attention on students’ international mobility, in the last years different studies in literature have analyzed the impact of such experience abroad on personal development of students, identifying the main characteristics and implications of academic mobility and investigating the benefits of the Erasmus participation in entering the workforce after graduation (Verbik and Lasanowski 2007; Engel 2010; Kahanec and Králiková 2011; Iezzi et al. 2012; Novak et al. 2013; Rachaniotis et al. 2013; Beine et al. 2014; Bryla 2015, among others).

This paper follows the same path of the above studies in focusing on the peculiarities of Erasmus students and exploring the impact of mobility in terms of employment. With these aims, the main results of a web survey (Couper 2000; Bethlehem and Biffignandi 2012) based on two cohorts of undergraduates students (incoming and outgoing) who participated in the Erasmus Programme of an Italian University are illustrated. This survey is intended to collect the opinions of students on their mobility experience in terms of motivations, training courses, selection of the hosting countries, and satisfaction with university services. The effects of the short-term programme on the job market are also investigated.

After a preliminary exploratory analysis and a description of the main characteristics of Erasmus students, a multivariate statistical analysis is carried out to identify systematic relations between factors and groups of students with homogenous features. Specifically, we apply a multivariate correspondence analysis and, starting from the results of the factor analysis, perform a cluster analysis to classify the students into different groups. The empirical results give evidence of the importance of international students’ mobility in socializing with other cultures and improving international competencies and technical skills. Moreover, it comes out that the Erasmus experience is considered as an important element during job interviews, easing young workers for a first-time job.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. After a brief review of the main studies on the phenomenon of the students’ mobility (Sect. 2), in Sect. 3 we introduce the research methodology, focusing on the research aims and survey design (Sect. 3.1), as well as on the data processing and the statistical analysis performed on the data (Sect. 3.2). In Sect. 4 we describe the main empirical results of the web survey (Sect. 4.1) and present the findings of the multivariate statistical analysis (Sects. 4.2 and 4.3). Some discussion and conclusions are provided in Sect. 5.

2 Literature review

In the last years different studies have analyzed the phenomenon of academic mobility, highlighting its determinants and implications and underlining its impact on the undergraduates’ employment. Table 1 list some of the studies examining the students’ international academic mobility by country, period and methodological approach.

Most of the empirical evidence shows that the international experience has a positive impact on the personal development of students, and particularly on intercultural understanding and foreign language proficiency, but also on their academic development (Verbik and Lasanowski 2007; Kahanec and Králiková 2011; Kumpikaitè and Duoba 2011; Iezzi et al. 2012; Coşciug 2013; Novak et al. 2013; Rachaniotis et al. 2013; Vaicekauska et al. 2013; Beine et al. 2014; Caveziel et al. 2016). Furthermore, the mobility programme is found to always help students to become internationally competent and well-prepared for job requirements in a closely interrelated European economy, and it is seen as beneficial for students in finding their first job after graduation and for their early career (Verbik and Lasanowski 2007; Engel 2010; Kumpikaitè and Duoba 2011; Parey and Waldinger 2011; Gajderowicz et al. 2012; Severino et al. 2014; Bryla 2015).

The papers reported in Table 1 can be divided into two groups. The first consists of those studies that investigate the international mobility by using the official statistics for some European countries, and identify the main determinants of the choice of location of international students and evaluate the effect of studying abroad on international labor market mobility after students’ graduation by means of statistical methods, like linear regression and its variants (e.g. Verbik and Lasanowski 2007; Rachaniotis et al. 2013; Beine et al. 2014). The second group comprises the studies that sketch the profile of international students by means of a survey. The analysis is generally focused on an University of the country under investigation and in most cases is descriptive (e.g. Kumpikaitè and Duoba 2011; Coşciug 2013; Bryla 2015; Caveziel et al. 2016).

The essential findings of the papers displayed in Table 1 can be summarized as follows. The main motivational factors that influence the decision to apply for international mobility programmes are: the employment and residency opportunities, the quality of the student experience, including accommodation and social activities, and the costs associated with an international education (Verbik and Lasanowski 2007). Most of the students participate in students’ mobility programmes especially to gain international study and life experiences (Novak et al. 2013), to develop their international core competencies (Kumpikaitè and Duoba 2011; Vaicekauska et al. 2013), and to improve foreign language and academic knowledge (Coşciug 2013; Caveziel et al. 2016). Moreover, the motivation to study abroad is strongly associated to personal growth, changing life style and enlarging job opportunities (Severino et al. 2014), and to the medium and high socio-economic levels of students, measured by the social background of parents (Iezzi et al. 2012).

Another important feature that may attract international students is the quality of university and the costs of living and education fees (Engel 2010; Kahanec and Králiková 2011; Rachaniotis et al. 2013; Beine et al. 2014). In fact, it has been noted that the percentage market share of foreign students of a country is positively related to the academic quality of that country’s education system and negatively related to the cost of living. In addition, the availability of programs in the English language can act as an important tool to attract international students, and thus high-skilled migrants.

The mobility programmes, such as the Erasmus, have positive effects in terms of increasing labor market mobility within Europe. As a matter of fact, studying abroad increases an individual’s probability of working in a foreign country by about 15 % points (Parey and Waldinger 2011). Furthermore, international experience is considered to exert a strong influence on students’ professional development and position and higher education and proficiency in foreign languages, which are judged as been very important for students’ career development and job positions (Bryla 2015).

Even if students with past mobility experience are characterized by shorter search time duration, mobility per se cannot be treated as a positive predictor of employability (Gajderowicz et al. 2012). The mobility may be correlated with other characteristics that contribute to increase the probability of finding a job. It seems then that international mobility experience can be regarded as a signalling device rather than a method to accumulate human capital (Gajderowicz et al. 2012).

3 Research methodology

3.1 Research questions and survey design

In this study, the aim is to analyze the University students’ mobility with particular attention to the Erasmus experience. For the purpose, we start from the results of a web survey developed and conducted on a cohort of students from the University of Salerno, in the South of Italy, that have experienced a period of study abroad. Our research question mainly concerns the investigation of the determinants of the Erasmus experience, also by looking at the impact that it can have on improving students’ skills.

In particular we study the reasons and factors that influence the decisions of students’ to study abroad, even for a short period, exploring their profile and highlighting the differences and similarities between incoming (inbound, i.e. foreign students that spend their Erasmus period at the University of Salerno) and outgoing (outbound, i.e. Italian students that go abroad for studying) students.

A specific sub-section is also devoted to the relationship between the Erasmus experience and the entry into the working life for the outgoing students, with the aim of investigating the relevance of studying abroad within the international professional mobility as well as analyzing whether and how such experience could improve the employability of students.

To take into account the differences that characterize the training period for the outgoing and incoming students, two different questionnaires have been elaborated.

Both questionnaires are divided into three main sets of questions, each composed of sub-questions, for a total of 50 items for the outgoing and 30 items for the incoming. The first set of items is related to the respondents’ personal data, the second to mobility duration, motivation, accommodation, costs and personal impressions regarding mobility. The third set is related to the satisfaction of students with the services offered by the host university and with some aspects of the Erasmus experience. Only for the outgoing students a fourth set of questions concerning their work experience of students is added.

The survey has been conducted on a cohort of students who participated in the Erasmus Programme between 2005 and 2014 for the outgoing students, and between 2013 and 2014 for the incoming students.

The data have been collected on-line through the Surveymonkey platform. The web survey has been active from January to July 2015, and the number of participants amounted to 728 students (684 outgoing students and 44 incoming students). Even if the survey has been conducted via the web, the registered response rate has been relatively high (32.88 % for outgoing and 17.19 % for incoming).

3.2 Data processing and statistical methodology

First of all, our data-set has been pre-processed in order to identify missing values and other sources of possible errors (Biemer et al. 1991). Some items (i.e. variables) have been recoded in order to delete the categories with null frequency and reduce the effects and influence of those with low frequency. An explorative descriptive analysis has been then performed to highlight the main features emerging from the data.

Starting from the reached preliminary results (shown in Sect. 4.1), we have performed multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) (Rencher 2002; Greenacre and Blasius 2006) to explore the relationship between the students’ opinion and the international mobility experience and analyse the weights of the different factors that can affect the students’ mobility and the various aspects under study. A second MCA has been devoted to the evaluation of the impact of studying abroad on international professionalism. Both analyses are exploratory in order to validate the instruments used in the survey, and thus check its effectiveness. They could also help to assess the efficacy of the questions and find out which of them are the most significant and relevant for sketching a typical profile of Erasmus students as well as capturing the relationship between the international mobility experience and the opportunity to get a job. The analyses have been performed by Coheris Analytics SPAD v.8.2 (Lebart et al. 2004).

In order to manage the effects of variables with low frequencies, we have opted for MCA with selection of active categories, which allows to specify that certain categories of active variables have to be considered as supplementary categories.

The outputs of MCA have been interpreted looking at the absolute contributions and relative inertia for the active categories, and at the test-value for the supplementary variables. The absolute contribution (a.c.) of a variable indicates the proportion of variance (i.e. inertia) explained by each variable in relation to each axis. The categories with the biggest contributions are usually selected. The relative inertia (i.e. the squared cosine) represents the proportion of the total inertia explained by an attribute, and measures the quality of representation of categories on the axis. The categories with the biggest values are selected. The supplementary variables are included in the illustration if the test-value is greater than 2 in absolute value (with the confidence level α = 0.05). The bigger its test value, the more interesting is the category on that axis.

Based on the results of both multiple correspondence analyses, we have further performed a cluster analysis in order to characterize the groups of students and better understand their distinctive characteristics. The classification of cases from the calculated factorial coordinates is carried out by means of a mixed classification (SEMIS) that combines the method of clustering around moving centers and a Hierarchical Agglomerative Clustering (HAC) (Lebart et al. 2004). The first classification is obtained by crossing several initial partitions or considering a single partition built through the algorithm of mobile centers (K-means) around centers selected by the user or drawn at random. The aim is to find out stable groups, which are identified by the sets of units that are always assigned to the same cluster in each of the base partitions.

We have searched for stable clusters by crossing several initial partitions built around cases drawn at random. Such stable clusters are then aggregated by Ward criterion, as it has been shown that it results in a minimal loss of inertia at each step and ensures good compatibility between MCA and classification (Greenacre 1998). The final partition of the population is defined by cutting the dendrogram at a suitable level, identifying a smaller number of clusters.

To recognize the variables that are typical of groups, the percentage of category in group, which shows if the category is representative within group, is considered. Moreover, the characteristic elements are classified by order of importance with the help of the test value, to which is assigned a probability: the bigger the test value and the lesser the probability, the more the element is characteristic.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Erasmus students’ characteristics

The results of the preliminary analysis concerning the outgoing students show that the participation of women in Erasmus programme is higher than men (53.72 vs. 47.28 %). Moreover, students prefer to go to Spain (40.76 %), France (15.83 %) and Germany (13.64 %), for studying Liberal Arts (48.47 %), Technology (24.32 %) and Law and Economics (20.87 %).

The respondents declare that the main reasons for taking part in Erasmus are learning new competencies (68.49 %) and acquiring international academic training (24.49 %), and that the most important elements they considered when choosing the foreign university are the language (49.67 %) and the opportunity to find a job in future (24.12 %).

They are very satisfied with the Erasmus office (76.96 %), the Erasmus tutor (61.29 %), the university (84.43 %), the relationship with professors (81.50 %), the syllabus of lectures (79.60 %), the lectures notes (79.80 %) and teaching (83.20 %).Footnote 2

About the relationship between the Erasmus experience and the opportunity of being hired, they assert that the Erasmus could have a positive effect on the willingness of working abroad (97.47 %). Moreover, after their stay abroad they had have an interview (51.70 %) during which their Erasmus experience was considered very positive (61.87 %). Finally, studying abroad could influence the possibility of being hired (56.26 %).

The results of the data analysis regarding incoming students have pointed out that females have a greater propensity to come to the University of Salerno than males (68.99 vs. 32.01 %), and the most students come from Spain (45.24 %), from France, Germany, Poland and Portugal (9.52 %), in order to study Economics and Law (41.67 %) and Liberal Arts (36.11 %).

The respondents affirm that the main reasons for taking part in the Erasmus are learning new competencies (38.64 %), the international academic training (27.27 %) and the life experience (25.00 %). Moreover, the University of Salerno is chosen because of its geographical position (29.55 %), the advice of other students that have studied there (22.73 %) and the good location for their study (22.73 %).

They are very satisfied with professors’ quality (72.01 %), syllabus of lectures (67.44 %), teaching (55.81 %). About the services offered by the University, they express a positive judgment on the International Relations Office (86.36 %), classrooms (77.27 %), dining hall and food services (95.34 %), library (70.45 %) and the university website (67.44 %).

4.2 Evaluation of Erasmus students’ satisfaction

As said in Sect. 3.2, we have performed a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA), in order to explore the structure of the main variables of the questionnaire, identifying the relationships between students’ opinions and their Erasmus experience.

For this aim, 14 questions/variables have been chosen as active variables (Table 2), with 48 associated categories/modalities identified after the cleaning procedure.Footnote 3

To better interpret the results, 4 questions and 16 associated categories—related to the groups of Erasmus students’ (outgoing or incoming), the geographical division of countries, the scientific area of their degree, and the type of degree—have been considered as supplementary or illustrative (Table 3).

In order to investigate the structure of variables and capture the associations and connections between them, a two-dimension MCA solution (Fig. 1) has been considered as the most adequate, after looking at the scree-plot and the proportion of inertia. It can be easily interpreted looking at the absolute contributions and relative inertia (Table 4).

Since for this dimension the theoretical mean inertia percentage expressed by each category is 2.04 % (given by 100 % over the number of categories), modalities with absolute contribution greater than it have been considered significant.

The dimension 1 discriminates between students who are very satisfied of their experience and those who express a lower grade of satisfaction.

All these categories capture about 70 % of the inertia of the axis 1, while the other variables contribute very less to its creation. Since the relative contributions are all greater than 20 %, and in some cases they approach to 50 %, all modalities can be regarded to have a good representation.

The significant supplementary variables, included in the illustration of the dimension 1, are shown in Table 5.

Portraying the dimension 1, we can argue that the incoming students from Eastern Europe who enrolled in Economics and Law are not completely satisfied, as opposed to the students going to Northern Europe who are completely satisfied.

The dimension 2 juxtaposes students who would suggest to participate in Erasmus because it is a somewhat interesting experience and those who would not recommend to take part in it (Table 4). All these categories capture about 53 % of the inertia of the axis 2. As in the first dimension, the relative contributions for all these elements are greater than 20 %, hence these categories are well represented by the second factor.

About the supplementary variables, the most significant variables are reported in Table 5.

Using a description for the dimension 2, it can be said that the students going to Western Europe who enrolled in the technological area think that the Erasmus is a good opportunity to learn languages, meet new friends and find a job, as opposed to the students coming from Southern Europe who would not suggest to study abroad for short period not to delay the graduation.

Based on these results, we have performed a cluster analysis in order to identify groups of students with common characteristics. In Fig. 2 the classification into three main groups is displayed.

The first cluster consists of 517 units (about 71.31 %), and it is characterized by students that go to Southern Europe for their Erasmus experience and have read some informative flyers on the mobility programme. They are completely satisfied by the relationship with professors of the hosting University, syllabus of course attended during their Erasmus period, the lecture notes and the teaching. Moreover, they would recommend participating in the Erasmus programme.

The second cluster is composed of 181 students (about 24.97 %) and is represented by incoming students that come from Western Europe. They are partially satisfied and their level of language knowledge after the experience is B1.

The group 3 is composed by 27 units (about 3.72 %) and is represented by students who are enrolled in Economics and Law and do not recommend to participate in Erasmus, and whose satisfaction is low.

4.3 Analyzing the impact of Erasmus on job market

In this section we draw the main results of the multiple correspondence analysis, performed so as to analyze the students’ opinions on the relationship between the international mobility and the acquisition of more technical competencies useful for finding a job after graduation.

For this aim the analysis focuses on the variables (active variables) that characterize the students’ opinions on the impact of the Erasmus experience on getting a job. The active variables and associated categories are 18 and 51 (after cleaning), respectively, and are shown in Table 6.

The questions considered as supplementary or illustrative, related to the personal information of students, are displayed in Table 7.

Again, the first two dimensions are chosen by looking at the scree-plot and the proportion of inertia and are able to catch the association between studying abroad and international professionalism (Fig. 3). The most important categories are those with absolute contributions greater than 1.96 %, i.e. the theoretical mean inertia percentage expressed by each category (Table 8).

The juxtaposition between respondents who do not work and those who work and/or have a job interview and think that Erasmus experience have had a positive impact on their employment is described in the first dimension.

About 58 % of the total inertia of this dimension has been captured by these categories, whose relative inertia is greater than 20 % and for the modalities of question Q.38 (working/not working) it approximates to 1. The supplementary variables, that integrates the description of the first dimension, are displayed in Table 9.

On this dimension male students in technological area, that work and think that Erasmus experience has a positive impact on employment are opposed to female students in healthy and Liberal Arts area that do not work.

The dimension 2 juxtaposes respondents who considered some elements as important for finding a job and those who think that they are not relevant and the degree is not necessary to work (Table 8). The percentage of total inertia captured by these categories are about 72 %. The significant supplementary variables are displayed in Table 9. This dimension is characterized by students in technological area, that consider some elements very important to find a job and students in Liberal Arts area that consider the degree as not important and Erasmus as not determinant for getting a job.

The classification into 2 main groups, based on the MCA results, is displayed in Fig. 4.

The cluster 1 consists of 260 units (about 38.18 %). The main characteristics are that they are male, enrolled in a second cycle bachelor, attend a job interview after the Erasmus experience and work. They acquire some expertise during the Erasmus that is difficult to learn in Italy. Moreover, they believe that the most important elements that can help in finding a job are the knowledge of language, technical knowledge, the capacity of adapting to any kind of job, and the willingness to leave their own town.

In the cluster 2, there are 421 students (about 61.82 %). About the main characteristics, they are female, study Liberal Arts, do not work and do not have any job interview after their Erasmus experience. Finally, they think that the possibility of working is not a relevant element when choosing the destination for studying abroad.

5 Conclusion and discussion

Since globalization requires more and more specialized skills and knowledge, education needs to be characterized by globally accepted high academic standards, because high level qualifications obtained by a graduate in one country have to be accepted and recognized internationally as equivalent. Therefore, governments should ensure sustainable economic and social development for their countries by promoting measures aimed at the adoption of such standards and encouraging the exchange and mobility of students. Data show that students’ mobility is a steadily increasing phenomenon, which confirms that students are more and more willing to learn and/or to strengthen their competencies and knowledge.

Starting from the above considerations, this paper has focused on the student mobility within Europe, with particular attention to the determinants and characteristics of the mobility process from and toward Italy. We have presented the results of a questionnaire pilot survey analysis based on two cohorts of undergraduate students who participated in the Erasmus Programme in one University located in the South of Italy, namely Salerno. The analyses have been useful to check the efficacy of questions, so as to select the most relevant variables allowing to draw a profile of Erasmus students and give an insight into the connection between the international mobility experience and students’ working life.

Unlike previous studies that just illustrate the descriptive results of a survey (e.g. Bryla 2015; Caveziel et al. 2016; Coşciug 2013; Kumpikaitè and Duoba 2011), we have applied multidimensional statistical analyses in order to sketch the typical Erasmus student and evaluate the impact of mobility in terms of employment. This allows to draw some valuable considerations.

The Erasmus experience is regarded as very important in most of the cases to socialize with new cultures, increase skills and competencies, learn foreign languages or to improve its knowledge, even though in some cases it is judged negatively because it could delay the graduation.

The opinion and satisfaction on the aspects that characterized the Erasmus experience are different between outgoing and incoming students. Particulary, the incoming students (i.e. foreign students that spend their Erasmus period at the University of Salerno) are less satisfied than the outgoing students (i.e. local students that go to universities abroad). Under this respect, our investigation could help to implement policies aimed at improving the services offered.

It also emerges that studying abroad seems to have a positive impact on finding a job, because it is evaluated as positive during job interviews. Even though our exploratory analysis does not provide a measure of the impact of international mobility on working, it represents a first step toward a more comprehensive investigation on the incidence of Erasmus experience in finding a job.

Notes

The aspects of Erasmus experience and services offered by University are evaluated by using a scale with 10 values, where 1 means “completely not satisfied” and 10 means “completely satisfied”. We considered very satisfied students that gave an evaluation of different elements and services greater than or equal to 7.

The cleaning procedure has consisted in excluding the categories with low weights from the analysis and assigning them randomly to other modalities.

References

Agiomirgianakis, G., Lianos, T., Asteriou, D.: Foreign Universities graduates in the Greek labour market. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 9, 151–164 (2004)

Agiomirgianakis, G.: European Internal and external migration: theories and empirical evidence. In: Zervoyianni, A., Argiros, G., Agiomirgianakis, G. (eds.) European Integration, Chapter 10. Palgrave (Macmillan), Press Limited, Hampshire (2006)

Agiomirgianakis, G., Asteriou, D.: Human capital and economic growth: time series evidence in the case of Greece. J. Policy Model. 23, 481–489 (2001)

Beine, M., Noël, R., Ragot, L.: Determinants of the international mobility of students. Econ. Educ. Rev. 41, 40–54 (2014)

Bethlehem, J., Biffignandi, S.: Handbook of web surveys. Wiley, New York (2012)

Biemer, P.P., Groves, R.M., Lyberg, L.E., Mathiowetz, N.A., Sudman, S.: Measurements errors in survey. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. Wiley, New York (1991)

Bryla, P.: The impact of international student mobility on subsequent employment and professional career: a large-scale survey among polish former Erasmus students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 176, 633–664 (2015)

Caviezel, V., Falzoni, A.M., Vitali, S.: Esperienza erasmus: motivazioni e timori prima della partenza. Stat. Soc. http://www.rivista.sis-statistica.org/cms/?p=74 (2016)

Coşciug, A.: The impacts of international student mobility in Romania. Europolis 7, 93–109 (2013)

Couper, M.P.: Web surveys: a review of issues and approaches. Public Opin. Q. 64, 464–494 (2000)

Engel, C.: The impact of Erasmus mobility on the professional career: empirical results of international studies on temporary student and teaching staff mobility. Belgeo 4, 351–363 (2010)

Gajderowicz, T., Grotkowska, G., Wincenciak, L.: Does students’ international mobility increase their employability? Ekon. J. 30, 59–74 (2012)

Greenacre, M.: Clustering the rows and columns of a contingency table. J. Classif. 5, 3951 (1988)

Greenacre, M., Blasius, J.: Multiple Correspondence Analysis and Related Methods. Statistics in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton (2006)

Iezzi, D.F., Mastrangelo, M., Sarlo, S.: International mobility of university students: the Italian case. In: Proceedings of XLVI Scientific Meeting SIS (2012)

Kahanec, M., Králiková, R.: Pulls of international student mobility. Discussion paper series IZA DP No. 6233 (2011)

Kumpikaitè, V., Duoba, K.: Development of intercultural competencies by student mobility. J. Knowl. Econ. Knowl. Manag. 4, 41–50 (2011)

Lebart, L., Morineau, A., Piron, M.: Statistique Exploratoire Multidimensionnelle. Dunod, Paris (2004)

Novak, R., Slatinsek, A., Devetak, G.: Importance of motivating factors for international mobility of students: empirical findings on selected higher education institutions in Europe. Organizacija 46(6), 274–280 (2013)

Parey, M., Waldinger, F.: Studying abroad and the effect on international labour market mobility: evidence from the introduction of ERASMUS. Econ. J. 121, 194–222 (2011)

Rachaniotis, N.P., Kotsi, F., Agiomirgianakis, G.M.: Internationalization in tertiary education: intra-European students mobility. J. Econ. Integr. 28(3), 457–481 (2013)

Rencher, A.C.: Methods of Multivariate Analysis. Wiley, New York (2002)

Severino, S., Messina, R., Llorent, V.J.: International student mobility: an identity development task? Int. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 4, 89–103 (2014)

Vaicekauska, T., Duoba, K., Kumpikaite-Valiuniene, V.: The role of international mobility in students’ core competences development. Econ. Manag. 18, 847–856 (2013)

Verbik, L., Lasanowski, V.: International Student Mobility: Patterns and Trends. Observatory of Borderless Higher Education, London (2007)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amendola, A., Restaino, M. An evaluation study on students’ international mobility experience. Qual Quant 51, 525–544 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-016-0421-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-016-0421-3