Abstract

Addiction symptoms in relation to the use of social networking sites (SNS) can be associated with reduced wellbeing. However, the mechanisms that can control this association have not been fully characterized, despite their relevance to effective treatment of individuals presenting SNS addiction symptoms. In this study we hypothesize that sex and neuroticism, which are important determinants of how people evaluate and respond to addiction symptoms, moderate this association. To examine these assertions, we employed hierarchical linear and logistic regression techniques to analyze data collected with a cross-sectional survey of 215 Israeli college students who use SNS. Results lend support to the hypothesized negative association between SNS addiction symptoms and wellbeing (as well as potentially being at-risk for low mood/ mild depression), and the ideas that (1) this association is augmented by neuroticism, and (2) that the augmentation is stronger for women than for men. They demonstrated that the sexes may differ in their SNS addiction-wellbeing associations: while men had similar addiction symptoms -wellbeing associations across neuroticism levels, women with high levels of neuroticism presented much steeper associations compared to women with low neuroticism. This provides an interesting account of possible “telescoping effect”, the idea that addicted women present a more severe clinical profile compared to men, in the case of technology-“addictions”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rather than reflect extremes of normal behavior, it is becoming increasingly recognized that excessive Internet, gaming, or social media use can be associated with symptoms and phenomenology consistent with addiction [1]. These symptoms include urges and craving, cue salience, mood dysregulation, sleep disturbances, as well as effects analogous to tolerance and withdrawal [2]. Regardless, of the classification of people as “addicted” or not, the mechanics of which are still debated [3] and not yet finalized in the DSM [4], Internet users present varying degrees of addiction-like symptoms and these symptoms, even at low-medium levels, may be bothering and reduce various aspects of users’ performance and quality of life [5]. We hence take a two-pronged approach in this study. For theory development and testing, we treat addiction symptoms as a continuous concept the level of which, regardless of classification, can lead to reduced wellbeing [6]. This approach is consistent with prior research and allows for theorizing without assuming the so far inexistent scientific knowledge needed for Internet addiction classification [7]. Next, for adding a secondary layer of confidence in the proposed theory, we test it using an established classification of people as at-risk for technology addiction [8]. This classification is not meant to represent a clinical diagnosis nor does it meant to replace clinical interviews. It just detects at-risk individuals and can only serve as an initial basis for clinical interviews.

In this study we focus specifically on symptoms of addiction to social networking site (SNS) use. This addiction is defined as a state of maladaptive dependency on the use of SNS which manifests in an obsessive-compulsive pattern of seeking and engaging in SNS use to the extent that it produces addiction-like symptoms, such as withdrawal, tolerance, salience, conflict, relapse and mood modification [9]. Estimates of maladaptive or pathological use patterns for SNS have ranged between 1.6% (Nigeria) up to 34% (China/Hong Kong) in various international samples focusing mostly on adolescents and young-adults [10]. A recent study of 5961 Hungarian adolescents demonstrated a prevalence rate of at-risk for SNS addiction people to be 4.5%, but also showed that many in the rest of the population present varying levels of addiction-like symptoms in relation to SNS use [8].

Prior research has pointed to unresolved sex-based differences, not only in prevalence of addiction symptoms, but also possibly in the neurobiological and psychosocial roots of such addictions and the way the sexes respond to and deal with addiction symptoms. For example, women are more prone than men to SNS addiction [11] and present stronger addiction symptoms [9]. In the abovementioned Hungarian sample, 58.8% of the at-risk group included women. In addition, females presented a higher association between Internet addiction and depression compared to males [12]. Other sex-based differences in addiction correlates include parental alcohol abuse, ADHD, personality traits, stress reactivity, and mescorticolimbic function [13]. However, possible differences in the way the sexes react to SNS addiction symptoms have not been fully explored.

Moreover, personality traits, and specifically neuroticism [a tendency to experience negative emotions, especially in stressful situations, 14] appear to play a prominent role in excessive Internet applications consumption. A meta-analysis of big-five personality association with Internet addiction found a large positive effect size for neuroticism [14]. Personality disorders, which correlate positively with neuroticism [15] are also associated with maladaptive Internet use. Neuroticism increases the likelihood of developing addictive behaviors, potentially as a maladaptive coping strategy, in addition to conferring a greater risk of developing Axis I disorders such as depression, a negative indicator of personal wellbeing [16]. On average, women have slightly, but significantly higher mean neuroticism scores relative to men [17]. However, it is not entirely clear how sex and neuroticism interact to influence the way users cope with and subjectively feel when addiction symptoms emerge in relation to social media use.

Collectively, findings regarding possible sex and neuroticism-based differences regarding Internet-related addictions suggest that more research on how the sexes differ, under different neuroticism conditions, in their responses to Internet, and specifically SNS addiction, is warranted. Findings from such studies can guide the development of more nuanced interventions. In this study, we seek to address this gap and examine one mechanism that can account for sex-neuroticism-based differences in the association between SNS addiction symptoms and wellbeing. Wellbeing is defined as the evaluation of one’s own quality of life, health, and satisfaction [18]. When people use the Internet (and SNS) compulsively, they often incur a range of adverse consequences, such as mood swings, conflict with other activities, reduced health, poor sleep, diminished academic and job performance, complaints from other people, difficulties in emotion regulation, and negative emotions such as guilt [5, 19]. Under such circumstances, it is reasonable to assume that their wellbeing is diminished. This view received support in numerous studies on addictive Interment use [20,21,22]. Even outside the context of problematic use, engagement with social media is associated with reduced wellbeing; the more people use Facebook, the lower their subsequent wellbeing was (alternative models ruled out the possibility that poor wellbeing predicted increased Facebook use) [23]. Taken together, we hypothesize that (H1) SNS addiction will be negatively associated with wellbeing.

Neuroticism is a key determinant of the way humans respond to negative emotional stimuli; individuals with high neuroticism generate stronger negative reactions to stimuli including visceral pain [24], stress induction [25] and negative affective priming [26, 27]. As such, it is reasonable to assume that people high in neuroticism subjectively assess SNS addiction symptoms as more problematic, stressful, emotionally draining and painful compared with people with low levels of neuroticism. Given that such responses diminish one’s wellbeing [28], people high in neuroticism should have reduced wellbeing compared with people low in neuroticism, in association with the same level of SNS addiction symptoms. We hence hypothesize that (H2) neuroticism will moderate (augment) the negative association between SNS addiction and wellbeing.

Lastly, it is reasonable to assume that the abovementioned moderated association is sex-dependent and that it is stronger for females. This idea is rooted in the notion that women can respond differently than men to stressors [29], including at the hormonal level [30], and have lower coping ability with stressors, compared with men [31]. On average, women see stressors as threats that require avoidance and elicit strong negative emotional response, while men, more often, see them as challenges that elicit weaker negative emotional response [32, 33]. Moreover, endocrinological processes may contribute to the differences in expression of poor wellbeing in males versus females- cortisol levels were negatively related to neuroticism in females, but positively related in men, reflecting biological differences in stress responses [34]. In addition, a study on the etiological pathways to major depression (a negative indicator of wellbeing) using opposite-sex twin pairs found that for women, neuroticism was 30% more potent in its influence on major depression as compared to men. Consequently, neuroticism was among the significant factors leading to major depression in women, whereas it was not a significant etiological factor for men [35]. Given that as per H2, the addiction symptoms- wellbeing association depends on one’s level of neuroticism, it is reasonable to assume a three-way interaction involving sex-based differences. We therefore hypothesize that (H3) sex moderates the neuroticism effect on the negative association between SNS addiction and wellbeing, such that this effect is stronger (more negative) for women.

Ultimately, this theory is in line with the “telescoping effect” developed in the substance and gambling addiction domains [36]. According to this perspective, while women are generally less likely than men to become addicted or present addiction-like symptoms, when they do, they present faster progression and a more severe clinical profile, including stronger psychological problems, compared to men. Our theory suggest that in the case of SNS, one reason for these differences is the way that women associate symptoms and wellbeing is influenced by their level of neuroticism, and is different from the way men deal with this association. Testing this model can therefore shed light on possible similarities between SNS addiction and substance addictions and point to the need for possible differential treatments for men and women who present addiction-like symptoms in relation to SNS use.

Methods

Participants

Israeli college students who use SNS (Facebook) were invited to participate in this study (n = 260); 215 completed the online survey (82.7% response rate). Inclusion criteria included active usage of Facebook at the time of the survey and signing a consent form that was approved by the Institutional Review Board of a research University. Exclusion criteria included age < 18. No exclusions were made. All participants gave an online informed consent when they started the survey. The university student segment of SNS users was deemed to be appropriate for this study because it presents varying degrees of SNS addiction symptoms [9] that are often associated with reduced wellbeing [37].

Procedure

Minimum sample size for an effect size of 0.15, desired power of 0.8, twelve predictors (one main effect, five controls, two direct effects of moderators, three two-way interactions, and one three-way interaction term), and probability level of 0.05 was calculated a-priori to be 127. An invitation to participate in a social media study was published on a bulletin board of a psychology department. Those who decided to participate completed the consent form and the subsequent online survey. No compensation was provided. There were no missing data.

Measures

Appendix 1 describes scale sources; it also provides the English version of measurement scales, and their descriptive and psychometric properties.

Statistical Analysis

Details regarding analyses are given in Appendix 2.

Results

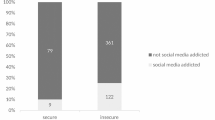

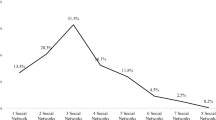

The sample included 215 Facebook users (158 women). Their average age was 26.99 (20–65, SD = 6.02). Their average Facebook friends score was 7.36 (1–9, SD = 2.05). Through extrapolation, the average number of Facebook friends is estimated to be 336. Their average Facebook daily use frequency score was 4.93 (1–6, SD = 1.22). Through extrapolation, the average Facebook daily use frequency is estimated to be 2.4 times per day. The sample’s average Facebook daily use time score was 3.08 (1–6, SD = 1. 47). Through extrapolation, the average Facebook daily use is estimated to be 1.1 h per day. Based on WHO-5 scores and recommended cutoffs, the sample included 73 people (34%) who were at-risk for low mood (or mild depression) and 13 people (6%) at-risk for major depression. Based on addiction symptoms scores and suggested cutoffs, the sample included nine people (all women; 4.2% of the population) who may be at-risk of SNS addiction. This is comparable to results obtained in prior research, using the English version of the scale in adolescents [4.5% in 8], which strengthens the confidence in the validity of the translated scale.

The indices provided in Appendix 1 combined with the CFA results reported in the “Measures” section and pilot test results demonstrated that all scales were sufficiently valid and reliable. The AIC and BIC indices of models including the four ordinal controls treated as continuous predictors of wellbeing were consistently better (much smaller) than these indices in models operationalizing the four ordinal controls with dummy variables (i.e., as discrete ordinal variables). It was therefore reasonable to treat the ordinal controls as continuous variables.

The correlations matrix is provided in Appendix 1. Results of the hierarchical regression models are presented in the left columns of Table 1 and depicted in Fig. 1. These results lend support to all three hypotheses. The three-way interaction model explained 64.4% of the variance in wellbeing. Additional analyses are reported in the two rightmost columns of Table 1. A model that uses a binary addiction variable produced similar results to those obtained by using a continuous addiction symptoms variable; the three way interaction was significantly associated with wellbeing.

The three-way interaction is plotted in Fig. 2. It first shows that men and women were similar in that those with high neuroticism, regardless of level of addiction, presented lower wellbeing compared to those low in neuroticism. The plot further shows that while the slopes of addiction symptoms’ effects on wellbeing are similar for men in high and low neuroticism conditions, they differ for women. Women high in neuroticism seem to bear more negative SNS addiction consequences, as manifested in reduced wellbeing, compared to others. Slope difference tests support this observation and indicated that there is a significant difference between slopes (1) and (3) (t = −0.3125, p < 0.002). This means that while men with low and high neuroticism have statistically similar slopes of addiction symptoms association with wellbeing, women with high levels of neuroticism present much steeper addiction-to-wellbeing slopes compared to women with low neuroticism. In addition, slope difference tests pointed to marginal difference between slopes (3) and (4) (t = 1.691, p < 0.092). This means that that among participants low in neuroticism; men actually have a somewhat steeper association between addiction symptoms and wellbeing. The simple slope test indicated that addiction symptoms predict wellbeing when the moderators are set to 0 (simple slope = −0.462, t = −0.531, p < 0.000). Overall, this analysis points to sex-based and neuroticism-level based differences in the association between SNS addiction symptoms and wellbeing.

The logistic regression results with WHO-5 ≤ 50 classification as the outcome are provided in the fifth column of Table 1. They show that addiction symptoms, neuroticism and being a female are associated with increased likelihood of being at-risk for low mood. The significant three-way interaction term indicates that women, high in neuroticism and addiction, have higher (17 fold) odds of being at-risk for low mood, compared to men, low in neuroticism and with low addiction symptoms. The model reached 85.1% general accuracy, and classified at risk for low mood correctly in 72.6% of the cases.

Focusing on at-risk for major depression classification (WHO-5 ≤ 28), we had only 13 positive cases and hence ran a model with only the main predictor (SNS addiction). The coefficient for addiction (β = 1.962, exp.(β) = 7.12, p < 0.001) indicated that an increase of one unit in SNS addiction symptoms is associated with a seven-fold increased likelihood of being at risk for major depression. Nevertheless, it failed to classify people as possibly being at risk for major depression.

Discussion

This study examined how neuroticism and sex interact to influence the established negative association between SNS addiction symptoms and subjective wellbeing in a sample of college-age Israeli participants. Firstly, we confirmed H1 and showed that higher scores on SNS addiction symptoms are related to lower subjective wellbeing. We also observed that higher neuroticism was associated with lower wellbeing. Lending support to H2, we showed that high neuroticism was associated with a stronger negative relationship between SNS addiction symptoms and wellbeing. Although neuroticism was associated with lower wellbeing independent of sex and SNS addiction symptoms score, the context of high SNS addiction had stronger negative association with female wellbeing: the association between addiction symptoms and wellbeing was similar for men regardless of their level of neuroticism, whereas for females, high neuroticism magnified the negative association between SNS addiction symptoms and wellbeing. This result confirmed our third, critical hypothesis. Support for this hypothesis was also provided when using a binary coded addiction variable that classified people to at-risk and low/no risk of SNS addiction categories. Another observation based on the three-way interaction was that for individuals low in neuroticism, men actually have a slightly steeper association between addiction symptoms and wellbeing. This suggests moderating factors apart from neuroticism are more relevant to men as compared to women in explaining associations between SNS addiction symptoms and wellbeing.

The model ultimately supports the key ideas on which we built the hypotheses, including the notions that (1) SNS addiction symptoms can be conceived as a persistent stressor that is associated with reduced wellbeing, (2) neuroticism alters the way people interpret and deal with such stressors, and (3) women differ from men in the way they subjectively associate combined SNS addiction symptoms-neuroticism states with wellbeing. There are, to our knowledge, no studies linking sex differences in neuroticism and wellbeing in the context of addiction and especially SNS addiction symptoms. Taking a broader addiction perspective, the findings demonstrate that the “telescoping effect”, which is common in substance abuse and gambling contexts, can be relevant to SNS addiction and there are possible similarities between the way sex is associated with SNS addiction and the way it is associated with other addictions.

Ultimately, the preliminary results of this study point to a need for further inquiries into how (and why) males and females differ in associations with behavioral addictions in order to identify effective treatments. From a practical standpoint, they suggest that tailored treatments should be developed based on one’s sex and neurotic traits; special attention to wellbeing improvement techniques should be given in the case of women high in neuroticism who seek treatment for Internet-related addictions. The efficacy of this approach should be tested in future research.

Several limitations of this study that point to interesting future research are noteworthy. First, this study was cross-sectional in nature. Longitudinal designs can help in establishing better causality. Second, this study did not account for possible comorbidities, even though such comorbidities are common with Internet addictions [38]. Future research can better account for potential effects of additional co-present disorders and states. Third, we employed a simple set of suggested cutoffs for creating at risk classifications for addiction and low-mood. Future research can employ more robust depression and addiction screening. Fourth, the chosen statistical techniques are limited; future research can supplement them with qualitative data, clinical interviews and larger samples. Fifth, future research may use continuous control variables rather than ordinal one. Lastly, this study used subjective measures. Future research can extend our findings with experimental contexts that employ physiological measures, such as psychophysiological or hormonal indices and neuroimaging.

Conclusions

This study suggests that sex-based differences exist in the way SNS addiction symptoms, neuroticism and wellbeing are associated. This finding is theoretically significant because it develops a new theory that captures sex-neuroticism profile associations, points to additional possible similarities between behavioral addictions on the spectrum of Internet addiction disorders and more established substance and gambling addictions, and provides initial support to the extension of the “telescoping effect” from substance and gambling addictions to the case of SNS addiction symptoms. The findings are practically meaningful because they pave the way for the development of more tailored interventions aiming to improve the wellbeing or alleviate the suffering of people who present addiction symptoms in relation to SNS use. We call for future research to further examine sex-based differences in people who present addiction symptoms in relation to the use of various technologies.

References

Turel O, Brevers D, Bechara A. Time distortion when users at-risk for social media addiction engage in non-social media tasks. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;97:84–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.11.014.

Turel O, Serenko A. The benefits and dangers of enjoyment with social networking websites. Eur J Inf Syst. 2012;21(5):512–28. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2012.1.

He Q, Turel O, Bechara A. Brain anatomy alterations associated with Social Networking Site (SNS) addiction. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45064.

He Q, Turel O, Brevers D, Bechara A. Excess social media use in normal populations is associated with amygdala-striatal but not with prefrontal morphology. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2017;269(1):31–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.09.003.

Turel O, Qahri-Saremi H. Problematic use of social networking sites: antecedents and consequence from a dual-system theory perspective. J Manage Inform Syst. 2016;33(4):1087–116.

Turel O. Untangling the complex role of guilt in rational decisions to discontinue the use of a hedonic Information System. Eur J Inf Syst. 2016;25(5):432–47. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41303-016-0002-5.

Turel O, Serenko A, Integrating GP. Technology addiction and use: an empirical investigation of online auction sites. MIS Q. 2011;35(4):1043–61.

Banyai F, Zsila A, Kiraly O, Maraz A, Elekes Z, Griffiths MD, et al. Problematic social media use: results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169839.

Turel O, He Q, Xue G, Xiao L, Bechara A. Examination of neural systems sub-serving Facebook "addiction". Psychol Rep. 2014;115(3):675–95. https://doi.org/10.2466/18.PR0.115c31z8.

Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501–17. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517.

Turel O. An empirical examination of the “vicious cycle” of Facebook addiction. J Comput Inform Syst. 2015;55(3):83–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2015.11645775.

Wu AMS, Li JB, Lau JTF, Mo PKH, Lau MMC. Potential impact of internet addiction and protective psychosocial factors onto depression among Hong Kong Chinese adolescents - direct, mediation and moderation effects. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;70:41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.06.011.

Fattore L, Melis M, Fadda P, Fratta W. Sex differences in addictive disorders. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35(3):272–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.04.003.

Kayis AR, Satici SA, Yilmaz MF, Simsek D, Ceyhan E, Bakioglu F. Big five-personality trait and internet addiction: a meta-analytic review. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;63:35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.012.

Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Schutte NS. The relationship between the five-factor model of personality and symptoms of clinical disorders: a meta-analysis. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2005;27(2):101–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-005-5384-y.

Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Rooke SE, Schutte NS. Alcohol involvement and the five-factor model of personality: a meta-analysis. J Drug Educ. 2007;37(3):277–94. https://doi.org/10.2190/DE.37.3.d.

Costa PT, Terracciano A, McCrae RR. Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: robust and surprising findings. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81(2):322–31. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.81.2.322.

Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol Bull. 1999;125(2):276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.125.2.276.

Turel O. Quitting the use of a habituated hedonic information system: a theoretical model and empirical examination of Facebook users. Eur J Inf Syst. 2015;24(4):431–46. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2014.19.

Caplan S. Problematic internet use and psychosocial well-being: development of a theory-based cognitive-behavioral measurement instrument. Comput Hum Behav. 2002;18(5):553–75.

Caplan S, Williams D, Yee N. Problematic internet use and psychosocial well-being among MMO players. Comput Hum Behav. 2009;25(6):1312–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.06.006.

Muusses LD, Finkenauer C, Kerkhof P, Billedo CJ. A longitudinal study of the association between compulsive internet use and wellbeing. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;36:21–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.035.

Kross E, Verduyn P, Demiralp E, Park J, Lee DS, Lin N, et al. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e69841. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069841.

Coen SJ, Kano M, Farmer AD, Kumari V, Giampietro V, Brammer M et al. neuroticism influences brain activity during the experience of visceral pain. Gastroenterology 2011;141(3):909-U639. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.008.

Gunthert KC, Cohen LH, Armeli S. The role of neuroticism in daily stress and coping. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(5):1087–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1087.

Robinson MD, Ode S, Moeller SK, Goetz PW. Neuroticism and affective priming: evidence for a neuroticism-linked negative schema. Personal Individ Differ. 2007;42(7):1221–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.027.

Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 2009;64(4):241–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015309.

Puig-Perez S, Villada C, Pulopulos MM, Hidalgo V, Salvador A. How are neuroticism and depression related to the psychophysiological stress response to acute stress in healthy older people? Physiol Behav. 2016;156:128–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.01.015.

Lighthall NR, Mather M, Gorlick MA. Acute stress increases sex differences in risk seeking in the balloon analogue risk task. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6002. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006002.

Kirschbaum C, Wust S, Hellhammer D. Consistent sex-differences in cortisol responses to psychological stress. Psychosom Med. 1992;54(6):648–57.

Tamres LK, Janicki D, Helgeson VS. Sex differences in coping behavior: a meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 2002;6(1):2–30. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0601_1.

Lighthall NR, Sakaki M, Vasunilashorn S, Nga L, Somayajula S, Chen EY, et al. Gender differences in reward-related decision processing under stress. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2012;7(4):476–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsr026.

Turel O. Organizational deviance via social networking site use: the roles of inhibition, stress and sex differences. Personal Individ Differ. 2017;119(1):311–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.002.

DeSoto MC, Salinas M. Neuroticism and cortisol: the importance of checking for sex differences. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:174–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.07.608.

Kendler KS, Gardner CO. Sex differences in the pathways to major depression: a study of opposite-sex twin pairs. Am J Psychiatr. 2014;171(4):426–35. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13101375.

Greenfield SF. Back SE, Lawson K, Brady KT. Substance abuse in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33(2):339–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.004.

Turel O, Bechara A. Social Networking Site use while driving: ADHD and the mediating roles of stress, self-esteem and craving. Front Psychol. 2016;7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00455.

Ha JH, Yoo HJ, Cho IH, Chin B, Shin D, Kim JH. Psychiatric comorbidity assessed in Korean children and adolescents who screen positive for internet addiction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(5):821–6.

Hahn E, Gottschling J, Spinath FM. Short measurements of personality - validity and reliability of the GSOEP big five inventory (BFI-S). J Res Pers. 2012;46(3):355–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.03.008.

Bech P, Gudex C, Johansen KS. The WHO (ten) well-being index: validation in diabetes. Psychother Psychosom. 1996;65(4):183–90. https://doi.org/10.1159/000289073.

Steenackers K, Cassady B, Brengman M, Willems K. Measuring Facebook Addiction among adults: validating the Bergen Facebook addiction scale in a non-student sample. J Behav Addict. 2016;5:41.

Pontes HM, Andreassen CS, Griffiths MD. Portuguese validation of the Bergen Facebook addiction scale: an empirical study. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2016;14(6):1062–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-016-9694-y.

Blom EH, Bech P, Högberg G, Larsson JO, Serlachius E. Screening for depressed mood in an adolescent psychiatric context by brief self-assessment scales – testing psychometric validity of WHO-5 and BDI-6 indices by latent trait analyses. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10(1):149. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-149.

Topp CW, Østergaard SD, Søndergaard S, Bech P. The WHO-5 well-being index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(3):167–76.

Primack BA. The WHO-5 wellbeing index performed the best in screening for depression in primary care. Evid Based Med. 2003;8(5):155.

Heun R, Bonsignore M, Barkow K, Jessen F. Validity of the five-item WHO well-being index (WHO-5) in an elderly population. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;251(2):27–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03035123.

Lucas-Carrasco R, Allerup P, Bech P. The validity of the WHO-5 as an early screening for apathy in an elderly population. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2012;2012:5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/171857.

Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “friends”: social capital and college students' use of online social network sites. J Comput-Mediat Commun. 2007;12(4):1143–168

Turel O, Bechara A. A triadic reflective-impulsive-interoceptive awareness model of general and impulsive information system use: behavioral tests of neuro-cognitive theory. Front Psychol. 2016;7:601. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00601.

Dawson JF, Richter AW. Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: development and application of a slope difference test. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(4):917–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.917.

Funding

The authors report no extramural funding for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no potential conflict of interest pertaining to this Psychiatric Quarterly submission.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Scales and their Psychometric Properties

The survey was completed in the Hebrew language. The psychometric properties of the scales are given in Table 2, which also outlines the items in the English language. Table 3 provides the correlations between the constructs.

The wellbeing and neuroticism scales had validated adaptations to Hebrew, which were adapted in this study. The SNS addiction symptoms scale and some of the control variables were translated to Hebrew using a forward-backward translation process with two fluent bilingual researchers. The Hebrew scales were tested for face- and content-validity by presenting them together with the original English scales to a panel of 15 bilingual academicians who use SNS. No changes were made based on their feedback, and the content validity of the scales was affirmed via individual interviews with panel members. All scales (the newly translated and the ones with established translations) were then pilot tested with a sample of 30 Israeli students. They were judged to be reliable (all αs > 0.81) and loaded on the expected latent variables (all loadings >0.6) in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models.

SNS Addiction Symptoms

SNS addiction as manifested via addiction symptoms was captured with the Hebrew translation of the 6-item Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS, see [10]) using a 1–5 Likert scales (1 = very rarely, and 5 = very often). In this scale, each item captured the frequency of one key core symptom of addiction (salience, tolerance, mood modification, relapse, withdrawal, and conflict). This scale has been shown to work well in various International samples, including in adolescents, students and adults [41], and has been successfully translated to various languages [42]. Recently, a cutoff of 19 was suggested as a differentiator between people at-risk of SNS addiction and those with low or no risk of such addiction [8]. We use the scale here as continuous, i.e., encapsulating the level of addiction-like symptoms, as well as for producing the at-risk vs. no/low risk of SNS addiction classification using the abovementioned cutoff. As a continuous scale, it was consistent and reliable (see Table 2). It also presented good fit to the assumed factor structure in a CFA procedure in AMOS 24 [χ2(9) = 25.3, CFI = 0.94, IFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.059 with p-close = 0.34, SRMR = 0.031] and all loadings were over 0.58 and significant at p < 0.001. Hence, it was reasonable to use composite (imputed) scores from the CFA procedure in the regression analysis.

Neuroticism

Neuroticism was captured with three items from the Big Five inventory- short version (BFI-S) [39] as adapted in the Hebrew translation of the full Big Five inventory (https://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~johnlab/pdfs/BFI-Hebrew.pdf). Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = does not apply to me at all, 7 = applies to me perfectly). The scale was consistent and reliable (see Table 2). A CFA procedure in AMOS 24 was estimated together with the other two factors, it demonstrated good fit to the assumed factor structure [χ2(74) = 111.8, CFI = 0.96, IFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.052 with p-close = 0.41, SRMR = 0.054]; all loading were over 0.59 and significant (p < 0.001). Hence, a composite score from the CFA analysis was used in the regression models.

Sex

Sex was measured with a direct two-choice question (women coded as 1).

Wellbeing

Wellbeing was captured with the WHO (World Health Organization) five item Wellbeing Index (WHO-5) [40]. This scale had a valid Hebrew version that was taken from the WHO website. People were asked to report on feelings over the last two weeks by using a six-point Likert scale (0 = at no time, 5 = all of the time). The scale was consistent and reliable (see Table 2), and presented good fit indices in a CFA procedure in AMOS 24 [χ2(5) = 12.7, CFI = 0.97, IFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.050 with p-close = 0.42, SRMR = 0.025] and all loadings were over 0.57 and significant at p < 0.001. Hence, its composite (imputed) scores from the CFA procedure were used in the regression analysis.

While the scale is meant to measure wellbeing, it has been suggested as a valid tool for initial screening (as a preliminary step before clinical interviews, not instead) for at-risk for depression. Those with scores (sum*4) of less than 50 were suggested to be at-risk for low-mood or mild-moderate depression [43] and those with a score below 28 were proposed to be at-risk for major depression [44]. While such classification is rudimentary, it has been shown to be a good predictor of actual clinical depression, with sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 64% and to do better at preliminarily screening for at-risk of depression compared with PHQ-9 and the General Health Questionnaire [45]. Subsequent studies also showed that WHO-5 is adequate at the detection of depression [46] and apathy [47] in elderly populations.

Demographic, control and descriptive variables

These included age [open ended, continuous quantitative], number of Facebook friends [1–9 Likert Scale, based on Ellison et al. [48], 71 = up to 10 friends, 9 = over 400 friends], frequency of Facebook use [1–6 Likert Scale, based on Turel, Bechara [49], 1 = less than once a month, 6 = over four times per day], time per day on Facebook [1–6 Likert Scale, based on Turel, Serenko [2], 1 = less than 10 min per day, 6 = over three hours per day], and education [1–5 Likert Scale, 1 = elementary school, 6 = doctorate].

Appendix 2: Detailed Statistical Procedures

Data were first tested for validity and reliability with multiple indictors: Cronbach alpha, Guttman split-half coefficients, corrected item-total correlations, percent of variance explained by the latent variables, and loadings and fit indices extracted from CFA models in AMOS 24. After establishing sufficient validity and reliability, composite factor scores were generated for all multiple-item scales in AMOS 24. These scores were used in a hierarchical regression model in SPSS 24, with wellbeing as the dependent variable. Because four of the control variables were operationalized as ordinal variables, and even though linear regression is not sensitive to the use of such variables as continuous ones, we tested which treatment is better using guidelines in: https://www3.nd.edu/~rwilliam/xsoc73994/OrdinalIndependent.pdf. Specifically, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) indices of models using each control as a continuous variable were contrasted with the same indices of models operationalizing these controls with dummy variables.

After establishing that the operationalization is adequate, variable entry order in the regression model was: (block 1) five control variables (Facebook friends, daily use frequency, daily use time, age and education), (block 2) the key predictor, namely SNS Addiction, (block 3) neuroticism and its interaction with SNS addiction, and (block 4) sex, two two-way interaction terms of sex, and the three way interaction term. In order to avoid distributional assumptions, bootstrapping with 500 re-samples and bias-corrected estimates were employed in the regression analysis. Next, for the linear regression model, analysis of differences between slopes of four groups [low (-1SD) vs. high (+1SD) neuroticism for men and women] was performed using tools in http://www.jeremydawson.co.uk/slopes.htm, which rely on Dawson, Richter [50]. Last, the moderation effects were plotted using the three-way interaction plotting facilities on the same website.

To supplement these analyses and enrich the findings, three additional analyses were performed. First, the binary variable representing the classification of people as at-risk vs. low/no risk of SNS addiction was used as a regressor (dummy variable, instead of continuous addiction symptoms score) in the full model. Given multicollinearity, the addiction classification interaction with neuroticism was excluded. Second, a logistic regression model with the same predictors as in the full model and with the binary classification of at-risk for low mood =1 and not =0 as the outcome variable was fit to the data. Third, a smaller model focusing only on SNS addiction symptoms as the predictor and the binary classification of at-risk for major depression as the outcome was fit to the data. This model was more restrictive in terms of predictors given the small number of subjects who met possible at-risk for major depression criteria.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Turel, O., Poppa, N.“. & Gil-Or, O. Neuroticism Magnifies the Detrimental Association between Social Media Addiction Symptoms and Wellbeing in Women, but Not in Men: a three-Way Moderation Model. Psychiatr Q 89, 605–619 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-018-9563-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-018-9563-x