Abstract

South Asia, with a quarter of the world’s population, has at least a quarter of the world’s children who should be in primary school but are not. As a region, South Asia will almost certainly fall short of achieving the second EFA goal by 2015: full access to, and completion of, primary education. What can be done now to improve the prospects of achieving the goal as soon after 2015 as possible and to lay a solid foundation for doing so?

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The long journey

In 1910, a full century ago, the educator Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who was also president of the Indian National Congress and a member of the Imperial Legislative Council of Colonial India, introduced a resolution in the Council. He proposed that “a beginning be made in the direction of making elementary education free and compulsory throughout the country” and that a “mixed Commission of officials and non-officials be appointed at an early date to frame definite proposals” (Venkataith 1999, p. 67). Colonial India then included present Bangladesh and Pakistan. In introducing the resolution, Gokhale observed presciently, “It is a small and humble attempt to suggest the first steps of a journey, which is bound to prove long and tedious, but which must be performed, if the mass of our people are to emerge from their present conditions” (p. 67).

Four decades later, in 1950, article 45 of the Constitution of independent India directed the state “to endeavour to provide, within a period of 10 years from commencement of the Constitution, for free and compulsory education until [children] complete the age of 14”. It took another 42 years for the Supreme Court of India to make the observation that the “directive principles” had little effect and that provisions must be made to achieve this goal, as a fundamental right for all Indians. The 86th amendment of the Indian constitution, adopted in 2002, guaranteed primary education as a fundamental right. On 1 April 2009, based on this amendment, the landmark Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act (RTE Act) was passed.

The Act makes it a legally binding obligation of the government to provide free elementary education to every child from age 6 to 14, ensure compulsory admission and availability of neighbourhood schools, eliminate discrimination, and take measures to guarantee quality education. According to the Act, private schools have to admit poor neighbourhood children to the extent of 25% of admissions in the first grade, whose tuition fees will be reimbursed by the state to the school on the basis of its expenditure per student (Tilak 2010).

The constitutions of Bangladesh and Pakistan contain “directive principles” similar to those in India, which fall short of making education a legally enforceable obligation of the state. In Nepal, the post-monarchy Constituent Assembly, which has the task of drafting a new national constitution, is considering a right-to-education provision.

Rights, needs and implementable policy

The right to education as a human right for every child has been proclaimed in international commitments and conventions to which all the South Asian countries are signatories, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989).

The spirit and letters of national commitments and binding international treaties recognize that all children, equally, have the right to quality education; that is, they have the right to access, attend, and participate effectively in a full cycle of basic education, as defined in each national context, regardless of their differentiating characteristics, such as gender, economic situation, geography, ethnicity, caste, linguistic identity, personal abilities, or a disability or special need.

Still, tens of millions of children in South Asia are deprived of their right to quality education, in a supportive and protective environment, free of discrimination. The interactions between poverty, gender inequality, and social exclusion are reflected in wide disparities in the educational demand and effective access between the more privileged and the disadvantaged groups and individuals.

Advocates of a rights-based approach to educational development consider it the essential framework for conceptualizing, designing, and implementing comprehensive change in the education system to achieve Education for All—it is not just an add-on to an existing educational programme.

A needs-based approach is sometimes contrasted with the rights-based approach, and some argue that the former, while more prevalent, has failed to deliver results (UNESCO and UNICEF 2007, p. 11). This is a simplistic reading of the complexity of the problems and the multi-faceted efforts needed to fulfill the right to education. Surely the key components of a rights-based approach are efforts by states and other actors to define and identify the needs and deficits, and then to design and implement programmes to meet these needs. Without such a focus, this approach risks being reduced to a mere expression of a polemical position.

The authors in this issue discuss various aspects of the Universal Primary Education (UPE) efforts in four South Asian countries; in doing so, they show how the countries are directing their efforts at filling huge and persistent deficits, while invoking the rights of children and citizens and the obligations of the state and other duty-bearers to create a supportive environment. Are these efforts sufficient and commensurate with the magnitude of the deficits? Is enough being done to define and assess the needs and respond effectively with appropriate urgency, determination, and scale? Is enough being done to define and articulate the rights and obligations of all, to inculcate the pertinent moral and ethical values, and to bring these to bear on fulfilling the needs? Obviously not, as we see from the past failures to reach the goals and the prospect of yet another failure to do so by 2015.

Can more be done to instill greater urgency and efficiency, redirecting efforts to overcome the exclusions and discrimination both in participation and quality of participation in educational services? Can more be done to invoke and apply the rights perspective to define priorities, combat exclusion, assess progress, and mobilize society’s commitment and energy? Obviously the answer is yes, as the situations described in these four South Asian countries amply illustrate.

In their article on India, R. Govinda and Madhumita Bandyopadhyay point out that a combination of three factors led to major progress in access and participation in primary education in the 1990s. These were a policy development exercise represented by the New Education Policy of 1986; it was followed by an elaborate action plan which led to a partnership between the federal and the state government to develop infrastructure and service delivery, with the federal government taking a proactive role. The second factor, as envisaged in the policy and the action plan, was a systematic move towards decentralization with the district as the hub for managing the implementation of the programme and providing support to schools. In addition, specially targeted alternative and flexible approaches, such as the education guarantee scheme, were initiated on a substantial scale. The third factor was political and social mobilization in support of elementary education, bolstered by a nationwide adult literacy campaign under the auspices of the National Literacy Mission. Though the adult literacy gains from the campaign fell short of expectations, its beneficial fallout was increased social awareness and interest in the primary education of children.

By the beginning of the new century, expansion in primary education in India resulted in over 100% gross enrolment. But the net rate was about one-third below the gross rate; in other words, about a third of the children who should have been in school were not within the ambit of educational services. In addition, at least a third of those who enrolled in the first grade did not stay on in school to reach the fifth grade. This meant that more than half of the primary age children were deprived of a full cycle of primary education. Also questionable is how much of the basic competencies, such as language and numeracy skills, is acquired by the children who stayed on in primary school. In the absence of systematic and reliable assessments of learning outcomes, the available evidence suggests that at least a third of the students who had had 5 years in school did not attain a level of language and mathematical skills that they could sustain or use as the foundation for further education.

In the first decade since the turn of the century, further progress has surely been made both in access and improvement in effective participation, but the time lag in data makes it impossible to capture it fully. However, as efforts are made to bring the more marginalized and difficult-to-reach populations into the system, progress inevitably slows. Change in the essential configuration of effective participation has become more resistant. The pattern persists: A gross enrolment of over 100%, with a significant gap between gross and net enrolment and a high dropout rate and a very high deficit in learning outcomes. Together, these facts form the real quantitative measure of primary education deprivation—and jeopardize hopes of achieving the 2015 goal.

The three other large-population countries of the region—Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal, also a focus in this issue—share the pattern for India, both in respect of progress made and constraints faced regarding access and effective participation. They have all reached a high level of initial intake and gross enrolment rates approaching the universal access mark. But two factors hold them back from achieving effective universal participation. First is the fact that significant marginalized groups are still deprived of even initial access. Second is the low internal efficiency, which is reflected in high overall rates of failure to complete the primary stage, and deplorably poor acquisition of basic skills in language and mathematics.

A closer look reveals that the common features hide important differences in the specific characteristics and causal factors of exclusion, and therefore, in the remedies that are attempted or needed. In India and Nepal, caste, ethnic origin, and religious identity are significant determinants of exclusion; they exacerbate and compound the disadvantages created by gender, poverty, and geographic location. As the Indian experience illustrates, the change process is particularly difficult and complex because of attitudes and values that are deeply rooted in the social psyche, which influence perceptions and behaviour regarding social group identities. In Bangladesh and Pakistan, economic status, to a degree concomitant with geographic and ecological factors, is the more dominant influence; it also interacts with gender attitudes, the child labour phenomenon, disabilities, and especially difficult circumstances for some children.

Amartya Sen, in his comments about the primary education situation in West Bengal in this issue, asserts that “class divisions have a clear connection with caste distinctions, but actually go much beyond what is caught in conventional caste-based categorization”. Writing of the scheduled castes (SC) and scheduled tribes (ST), he suggests that “Any detailed investigation of the empirical situation brings out the need to go well beyond the SC-ST characterization of social disadvantage”; it must also take “note of the historically conditioned economic and social disadvantages from which most Muslim families as well as SC and ST populations historically suffer in this region”.

The countries differ in one key respect. India has experienced continuity and a degree of consistency in policy-making and the pursuit of policy through democratic political governance that has continued for some six decades. In the other three countries, the development of the democratic polity has been interrupted by regime changes through military or extra-constitutional interventions. For instance, the other countries have no equivalent to the Report of the Indian Education Commission, 1964–1966, known as the Kothari Commission, and two decades later, the National Policy on Education, 1986 and its revision in 1992, particularly in respect to the common themes that connected them. India has also made serious and systematic efforts to use these as guides in shaping programme implementation. In fact, the other countries had no dearth of education policy commissions and policy reports, but their very frequency and numbers indicate the challenges to pursuing policy objectives consistently and with determination.

The elected government in Bangladesh that assumed power in 2009 made it a priority to formulate a new education policy based on a review of past policies and progress made so far. A new national policy has just been adopted, following extensive consultation, and is expected to guide educational development in the run-up to 2015 and beyond.

Why and how are children excluded from education?

As the Indian article in this issue points out, in the government’s National Sample Survey, when parents and children were asked why children left school without completing 5 years of education, very few mentioned the absence of school or “school too far” as the cause. The predominant reason they gave was the need for the boys to work to supplement the family income and for the girls to help at home. The next most important reason was that school education was “not considered necessary”, which presumably meant that children and their families did not consider schooling relevant for the children’s life expectations and the life prospects they visualized.

To better understand the underlying forces and indicate the elements of remedial strategies, Govinda and Bandyopadhyay juxtaposed the perceptions and expectations of the intended beneficiaries with the objective conditions and processes that contribute to educational exclusion.Footnote 1They analyzed the objective conditions in India and suggested five categories, which present a more complex interplay of the factors than simply poverty and the need to work for wages or at home. The five categories were: (a) children’s health and nutritional status; (b) poverty and child labour; (c) parental illiteracy and a home environment indicating “first generation learners”; (d) ethnic and minority group identity (e.g., Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Muslims); and (e) gender disadvantage. Also important are disabilities and the especially difficult circumstances facing some children (e.g., street children, children without family support, children of nomads and migrants). Although not specifically cited, a cross-cutting factor is geographic and ecological conditions, such as the disadvantage associated with living in rural areas, urban slums, inaccessible terrain, flood-prone and coastal areas, and arid and desert zones.

Sen observes in his West Bengal commentary that “The differential reach of primary education emerges quite strikingly in our [West Bengal] studies”; that is, “belonging to Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes, and coming from Muslim families, is not merely an indicator of caste or community background, but also, statistically, something of a proxy for class-related handicap”.

Despite India’s policy priorities and programmes targeted to disadvantaged groups, which have been operating for over two decades, many children in the SC, ST and Muslim population groups are still not in school. Specifically, in the mid-2000s, of the officially (thus conservatively) estimated total of out-of-school children, more than half belonged to those groups although together they constituted only 38% of the total population, according to the 2001 national census (Government of India 2001).

Shiva Lohani, Ram Balak Singh and Jeevan Lohani, the authors of the article on Nepal in this issue, identify persistent disparities related to ethnic status and geographic locations. The articles on Bangladesh and Pakistan do not specifically discuss the dimensions of inequality in education, but other sources indicate patterns comparable to those in India and Nepal (Ahmed et al. 2007; Aslam 2007).

In different ways, the articles in this special issue also illustrate how the socio-economic correlates of exclusion interact with educational and pedagogical factors. Education programmes sometimes attempt to respond to or adapt to these conditions. Often, however, the socio-economic correlates of exclusion are not given sufficient attention in education design and strategy, and are instead seen as matters beyond the domain of education. Indeed, direct intervention to alleviate poverty or overcome geographic inaccessibility would not be appropriate as a major agenda item in the education sector.

At the same time, an education programme that is unresponsive or indifferent to the socio-economic correlates of educational exclusion risks failure or meagre results. The articles in this issue describing the country situations in South Asia draw attention to various educational challenges in responding and adapting to the conditions surrounding intended education participants and beneficiaries. The articles illustrate the challenges to responding and adapting sufficiently, both while articulating policy objectives, and while following up with effective action. A few of the issues are highlighted below.

The role of diversity in educational provision

In Bangladesh, the government schools (GPS), accounting for less than half the total number of schools, serve 57% of students, as the article in this issue by Zia-Us-Sabur and Manzoor Ahmed describes. Meanwhile, the registered non-government schools (RNGPS), largely dependent on government funding, and representing more than half of formal primary institutions, serve 19% of the primary school students. Madrasas and proprietary English-medium schools serve another 10%. A special feature of the Bangladesh primary system is the second-chance non-formal primary education pioneered by BRAC, which continues to serve over a million children who are either dropouts from formal school or do not enroll in formal school for various reasons. They constitute about 10% of children in the primary system. However, the government policy remains ambivalent about the significance of this alternative and second-chance opportunity, in spite of its demonstrated success. As if to symbolize the official attitude, these schools and their students are not included in the official primary education statistics, thus presenting a somewhat misleading picture of the situation.

As the articles in this issue show, diversity in provisions appears to be an under-recognized phenomenon in terms of policy implications and their actual and potential role in designing and implementing responsive and adaptive education programmes.

As Lohani et al. describe, primary education in Nepal consists of two types of government-funded community schools—those where education authorities are highly involved in management and those with community-based school management—along with private proprietary schools, known as institutional schools, and the schools run by religious organizations. The public sector, therefore, consists of the community schools, which enroll about 85% of the primary education students. The institutional schools appear to be the growth sector in education, currently serving 14% of students; perceived as generally of higher quality than the public system, they attract a growing clientele who can afford the cost. The government-funded schools with school-based management, accounting for about a quarter of primary schools, represent an innovative effort to improve participation and quality for the relatively disadvantaged groups through stronger community accountability.

In Pakistan, one-third of the children in primary education were in privately run for-profit or non-profit schools. Their popularity and their share in enrolment are growing, because of the perception, borne out by evidence, that public schools were deficient in performance, quality, and accountability (Aslam 2007).

In India, in 2005–2006, about 10% of the children at the lower primary level and more than a quarter at the upper primary level went to schools other than those of the government. As part of government-funded education services, the Education Guarantee Scheme and Alternative and Innovative Education (EGS/AIE) served 7 million children or about 4% of those in primary education, who were not attracted to or could not be kept in formal primary schools. The Right to Education law adopted in 2009 recognized the role that private schools play in responding to expectations and demands in both urban and increasingly in rural areas, as noted above, so it provided for 25% of the first grade places in private schools to be offered to children from low-income families in the community, for whom the government would reimburse the tuition cost.

Sen writes about the role of Shishu Siksha Kendra (SSK or Child Learning Centres), taught by community-appointed para-teachers and managed with the close involvement of the community and the village-level local government. These served children who did not go to a regular school or did not perform well there.

Historically, this diversity in provisions developed in response to needs and circumstances in society. Each has its own characteristics—strengths as well as weaknesses—and one form of school cannot necessarily substitute for another. Is the principle of the right to education, and the state’s responsibility to provide it, contradictory to diversity in basic education provisions, especially in the private sector? The debate surrounding the Right to Education constitutional amendment and the law in India brought to the fore the concept of a common, free, and compulsory public system for all children, which its protagonists see as the only way to fulfill the right to education and to meet the state’s obligation in this respect. However, countries appear to have pragmatically accepted the diversity that has developed historically; they have also come to recognize the reality that the public system is not necessarily the most responsive to the circumstances and needs of the participants and not invariably equitable, and that a democratic polity cannot banish diversity in basic education provisions.

Increasingly, people are recognizing that the state’s obligations in fulfilling the right to education may be best served by creating the appropriate policy environment, establishing and enforcing regulatory systems, and maintaining oversight over implementation of the key policy objectives. Governments also can keep the bulk of the provision in compulsory primary and secondary level education in the public sector, as is the case in most countries, and serve as the “provider of last resort”. However, as the articles in this issue show, it remains difficult to articulate and clarify this position, working out the operational implications with a broad consensus and applying them in programmes. The degree of success that countries achieve in these respects will determine their progress towards EFA.

A quality concern: Teachers

In the four largest-population countries of South Asia, some 230 million students in primary education are taught by 5 million teachers. The great majority of the primary teachers have at least 12 years of formal schooling (higher secondary level), and in India and Bangladesh an increasing proportion have college degrees. In Nepal and Pakistan, a proportion of the teachers in rural areas are below this standard, and the goal is to require at least a higher secondary qualification for all teachers. In India and Bangladesh, the great majority, around 90%, have at least 1 year of teacher training; this figure is around 80% in Nepal and Pakistan.

In fact the education systems in these countries are plagued by problems in respect of both the numbers of teachers and the quality of personnel attracted to the profession, along with their professional preparation and professional support, and the incentives and rewards for their performance, as underscored in the article on Pakistan by Kulsoom Jaffer.

For these four countries, the average student to teacher ratio is around 40:1. In practice this means that some primary classes have a hundred or more students and in some schools, one or two teachers teach three or four classes. In Bangladesh, the learning time, or number of contact hours, is about half of the international average of a 1,000 hours per school year. New teachers are not always recruited in sufficient numbers to replace the annual natural attrition, as Jaffer mentions.

As noted in the case of India, in most states, trained teachers with higher qualifications are generally concentrated in urban areas. Increasingly para-teachers are being appointed in rural primary and upper primary schools on a contract basis and with much lower salaries than the regular teachers in some states. This is leading to a pattern where disadvantaged children are taught by poorly-qualified, low paid siksha karmis (para-teachers), while those from privileged families are more likely to be taught by a regular teacher.

Jaffer reports that the notion of supervision has gained currency in Pakistan as a way of offering continuous professional development opportunities for teachers. What has not shifted significantly is the supervisors’ job descriptions or the way the job is carried out—factors that would make a difference in teacher performance and development. Moreover, many government teachers hold a second job to supplement their meager income from teaching.

Although teacher training is a requirement and offered extensively at substantial cost, it does not seem to make a significant difference in student learning outcomes. One reason for this is the absence of other supportive elements, including learning aids, adequate professional support and supervision for teachers, incentives and motivation for performance, and a conducive learning environment (Ahmed et al. 2007). As Ahmed (2009) argued, in Bangladesh the system cannot achieve its goals with the current numbers of teachers, methods of preparation and professional development and the level of salary and incentives. New ways of thinking about teachers and pedagogy are needed, beyond actions for improvements within the current structure of teacher recruitment, remunerations, professional support and supervision.

Moreover, Sen, in this issue, writes of the “terrible affliction” of students depending on private tuition, a phenomenon that divides the student population into categories of “haves” and “have-nots”, makes teachers less responsible, and diminishes their central role in education. Drawing on studies in West Bengal, Sen also points out the problem of overloading the official curriculum: “The heavy load that very young children have to bear in pursuit of elementary education”. He sees a link between the unnecessary curriculum load and the requirement of children’s “home-based study […] after school hours, often in excessive and unreasonable ways”, especially for parents who did not have the benefit of schooling themselves, which leads to “unshakable dependence” on private tuition.

Indeed, the teacher has to be seen as central in the strategy to improve educational quality. Bold and creative measures are needed to attract talented and inspired young people to teaching, to keep them in the profession, and to create a critical mass of talented teachers in the education system.

An idea proposed to the Planning Commission of Bangladesh for consideration in the sixth 5-year development plan (2010–2015) may have relevance for other South Asian countries. To attract academically competent people to teaching in primary schools (as well as extended compulsory grades and secondary schools) and to keep them in the profession, the idea is to introduce education courses in the general education degree programme and offer education as a subject in at least one well-equipped degree college in each district. Competition could help attract strong candidates if stipends were offered to selected teachers who would undertake to serve in a primary school for at least 5 years.

To attract and keep the right people in the profession, these new teachers have to be paid salaries at levels competitive with other civil servants who hold similar educational credentials. Currently employed teachers may be offered this salary level if they meet specified criteria, including college graduation and an academic career with only first- and second-class exam results. Many countries use this combination of general education and pedagogy in the undergraduate college programme. But, for this proposal to succeed, countries must ensure high standards in both the facilities and teaching personnel in the selected degree colleges.

Over a decade, a hundred colleges in such a project, producing at least 10,000 teacher candidates each year (after the initial 4 years), would create a nucleus of high-quality and enthusiastic teachers in primary and secondary schools in the country. Eventually, in this scenario, the existing primary and secondary teacher training institutions can concentrate on much-needed continuous in-service training of teachers (Ahmed 2009).

The success of other quality initiatives, such as transforming pedagogy, making continuous and summative learning assessment and examinations more meaningful, and turning teachers into role models for young people, will depend on attracting talented and motivated people into teaching.

A second quality concern: Assessment of learning

In Nepal, three school-based periodic examinations are held each year, including the end-of-the year examination. In addition, the teachers use written tests, oral tests, class work, homework, and classroom questions to assess students’ learning outcomes. Examinations are also conducted at the school level for grade 5 at the end of primary education and at the district level for grade 8 at the end of lower secondary education. This general pattern is applied in the other countries, except in Bangladesh, where a national end-of-the-primary-cycle test was introduced in 2009.

Jaffer notes three common approaches to evaluating school performance in Pakistan: examinations and other assessments of cognitive attainment, school self-evaluation, and external evaluation through inspection. However, of the three, examinations to assess cognitive attainment predominate as the way to judge schools’ performance; some surveys of samples of students are applied at a national or regional level to measure outcomes, again focusing on students’ cognitive learning of the curriculum requirements.

In Nepal, national assessment surveys of primary-level children were conducted in selected years from 1997 to 2003. Lohani et al. point out that although the tests were not strictly comparable, as they were conducted at different times of the year and by different agencies, there was a trend toward underachievement in the core subjects: Nepali, mathematics and social studies. The students’ overall performance was lowest on mathematics, followed by Nepali and social studies. The findings do not suggest that the educational reform initiatives have made a significant difference in students’ learning achievement. Nor have the assessment results been analyzed for use in influencing the course of reform in teacher training, curriculum, and pedagogy.

Govinda and Bandyopadhyay, looking at India, point out that studies demonstrated a poor quality of teaching and learning, leading to children not acquiring basic skills in reading, writing, and arithmetic, after attending school for 5 and even 8 years. The 2006 Pratham Annual Status of Education Review revealed that in states where large numbers of children did not recognize letters or numbers in grades 1 and 2, their performance in reading and arithmetic in later years was poor (Pratham 2007). In Pakistan, one-third of the students in grade 3 could not subtract single-digit numbers; in India, 72% of those in grade 3 could not do subtraction problems with two-digit numbers. Many of these children attend irregularly and therefore fail to learn at appropriate levels, putting them at risk of dropping out. Other children continue to be enrolled at school and are physically present but gain little cognitive benefit from the experience. These children are generally first-generation learners and many live in environments that do not encourage them to study. Irregular attendance, low levels of learning, previous temporary withdrawals, being overage, and repeating grades tend to place children at risk of “silent exclusion”, as they invariably remain outside the concerns of policy makers as well as practitioners (Govinda and Bandyopadhyay 2008). This is one of the “zones of exclusion” identified by CREATE, as noted above.

Sen finds some consolation in the fact that only 5% of the students in classes 3 and 4 could not write their own names in a recent independent test in West Bengal, compared to 30% in 2001–2002. He remarks that this proportion should be zero percent, “but it would be silly not to see the progress that is observed”.

The recently adopted education policy (2010) in Bangladesh identified student assessment to discourage rote learning as a key strategy for improving quality in education. It proposes that assessments of learners’ achievement should aim at assessing cognitive, affective, and reasoning domains. The major public examinations would be held at the end of the 12th grade. Other examinations would be organized at the district or upazila levels at the end of grades 5, 8, and 10 to award scholarships and (possibly) evaluate system performance. The policy states that all examinations should be aimed at discouraging rote learning.

South Asia has not participated in international assessments of learning achievement in basic skills and competencies, such as the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), offered under the auspices of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). While some may question the value and meaning of a country’s comparative position in an international league table, participating in these studies would help countries build their technical capacity in learning assessment. It could also encourage the shift from examinations focusing on curriculum and textbook-based reproduction of facts and information to assessments of skills and competencies and their application in problem-solving.

Governance and decentralization

Effective governance and management are essential at both the central and school levels to ensure quality improvement. Two key aspects of management in education are: (a) authority and responsibility with accountability, including budget and resource management at the level of institutions; and (b) devolution of planning, management, and monitoring at district and local levels. In India, Nepal, and Pakistan, but less in Bangladesh, structural and procedural changes have been made to involve local government bodies, giving greater financial authority to schools and the local level, and encouraging the involvement of the community. The government in Bangladesh has made a key political commitment to decentralization through empowered local government, but has yet to take concrete measures on a substantial scale.

As noted earlier, in India, the district has been designated as the hub for planning development inputs for elementary education. A broader concurrent move has been made to decentralize the delivery of public services by empowering the local self-governance mechanisms through panchayati raj (local government) institutions. These steps have helped to strengthen the multi-layered planning and implementation framework for elementary education.

In Nepal, recent EFA plans and strategies have emphasized the critical role of community involvement in enhancing quality and equity in basic education. This has been a key consideration in all initiatives for strengthening education governance and school management. Meanwhile, the milestone Education Act Seventh Amendment (EASA) 2001 has made school management committees (SMCs) mandatory for both community and institutional schools, whether or not they receive government grants.

As Lohani et al. note, there is an unequal power relationship between the centre and the grassroots level, between educational bureaucrats and the community representatives. For the SMCs to function effectively, they need to develop capacity. A resource center for a cluster of 30–50 schools is expected to provide technical support to the schools. Similar resource centers exist in other countries, but, as pointed out for Nepal, the centres themselves have to develop the capacity to discharge their responsibility.

Recognizing the need to alter the relationship between government authorities and the communities, the Community School Support Project was launched in Nepal in 2002. It offered SMCs the option to accept greater responsibility in such areas as teacher recruitment and deployment, mobilizing financial resources, and managing the school budget, with stronger accountability to the community.

An additional incentive for the SMCs was a higher level of government financial support compared to other community schools. By 2008, some 8,000 schools, a quarter of the community schools, had opted to participate in school-based management. Two key components of school-based management are parent-teacher associations and school improvement plans, as the basis for accessing government resources; and social audits of the schools, as a mechanism for community oversight of schools. Apart from slow progress in learning and building the capability to exercise their new authority, the SMCs also face opposition from the teachers’ unions, which feel threatened by accountability to communities, rather than to the official hierarchy, and also sense threats to their job security.

The issue of working with teachers to achieve educational reforms deserves special attention. If teachers, as a professional group, become the adversaries in efforts at educational reform, that is hardly a formula for success. Sen describes a collaborative strategy that apparently was developed with the teachers’ unions in West Bengal—in fact, with two rival unions of primary teachers—which helped to produce a common understanding of problems and cooperation in implementing some recommendations.

In Pakistan, the 1992–2002 Education Policy proposed specific structural and functional changes in educational management, including the five below:

-

Establish school management committees (SMCs).

-

Appoint head teachers for each primary school and enhance the role of the head teacher as the educational leader.

-

Strengthen professional support and supervision, with no more than 15 schools under one supervisor.

-

Create a code of ethics for teachers and administrators, and base accountability and rewards on evaluation of teacher performance.

-

Provide purposive professional training for supervisors and head teachers and fill vacancies in these and other administrative posts.

As it turned out, steps were taken only to form the SMCs, but the failure to act on the other items rendered the SMCs ineffective. Particular constraints were the inattention to the many small rural schools and neglect of school leaders. In Sindh, for instance, a senior teacher is designated as in-charge to look after the day-to-day management of the school. Teachers are not enthusiastic about taking on this job, as it entails “responsibility without authority” and no special recognition in terms of status and remuneration. The same pattern prevails in the public sector primary schools in the other South Asian countries.

Resources for education

Bangladesh has one of the lowest-cost education systems, even compared to other least developed countries. This is reflected in its fairly extensive provision of basic education using the lowest ratio of GNP devoted to education in South Asia and one of the lowest ratios among developing countries. The system is best described as low-cost and low-yield, marked by high internal inefficiency and poor outcomes. The overall situation is only marginally better in the other three countries in respect to education financing.

The regional review of GMR 2008 reported that in these four countries of South Asia, the share of GDP devoted to education in the budget ranged from 2.3 to 3.8%, well below the median for developing countries of 4.5% (UNESCO 2008). This is one measure of availability of resources and an indication of the priority the government assigns to education. Another indication is the share of education within the total government budget. Here the range was from 11% to 16%, again below the benchmark ratio of 20% that is seen as a floor for education financing (UNESCO 2008, p. 12).

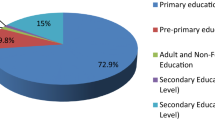

The resources actually available to basic and primary education depend on the percentage allocated to them within the education budget. In 2007, this percentage varied from 35.8% for India to a high of 62.9% for Pakistan. The pool from which public resources for education can be drawn depends on the absolute level of national and per capita GDP and the public revenues collected as a proportion of GDP. On both of these counts, South Asia is at a disadvantage, compared not only to developed countries, but also to other developing countries. In this respect, international assistance assumes a special significance, as does the willingness of richer countries to live up to their various commitments and pledges.

Along with the question of mobilizing increased resources, another concern is that education systems use those resources effectively, through greater accountability, transparency, and involvement of the beneficiaries. In Nepal the application of a formula of per capita funding (PCF), based on school enrolment, has been seen as a step towards transparency of funding and greater school control over resource management. PCF-based salary grants to community primary schools were introduced starting in Fiscal Year 07/08, allowing higher amounts to schools with higher student-to-teacher ratios. The PCF is expected to mitigate political influence over resource allocation.

In India, a new formula for education funding has been introduced, whereby districts with low education development indices received up to twice as much per child as districts in the highest quintile on the education development index.

While chronic under-resourcing of the system is a generic problem that spawns many other problems, not everything can be solved with additional funds. Along with effective management of resources and decision-making, and effective implementation of decisions regarding learning objectives and priorities, improvements are needed in the teaching process, in establishing accountability, and in performance standards at all levels.

Arguably, finance arrangements for education reinforce the pattern of inequity in the education systems in South Asia. To make education financing mechanisms and decisions into effective vehicles for serving educational objectives and priorities, as has been attempted in India and Nepal, will require governments to clearly articulate and delineate objectives in both qualitative and quantitative terms and then follow up with the implications for allocation decisions and implement them effectively.

A goal of 5% of GDP as the expenditure on public education would be a minimal benchmark target for these South Asian countries to reach, if not surpass, by 2015. Financing criteria and principles should be established and applied to support the objectives of quality-with-equity, such as the capitation formula and institutional control of resources. Substantial new resources need to be directed to teacher incentives and to raising the status of teaching as a profession and other quality improvement inputs.

Concluding comments

Returning to the elusive goal of the right to education, the rights perspective of educational development can indeed be a powerful framework for conceptualizing the priorities and strategies and for critically analyzing action to fulfill the needs in education, thus reconciling the rights with the needs. One way to categorize the rights of children and the obligations of the state and other actors, and also to assess what is needed to fulfill the obligations, that would resonate with the discussion above, is a four-fold taxonomy: making education available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable (Tomasevski 2004, p. 7; Sandkull 2005), as elaborated below.

Availability

Obligation to ensure compulsory and free education for all children in the country within a determined age range, up to at least the minimum age of employment, observing the principle of the best interests of the child.

Accessibility

Obligation to eliminate exclusion from education based on group or individual identity and characteristics: race, colour, sex, language, religion, geographical origin, economic status, ethnicity, disability status.

Acceptability

Obligation to improve the quality of education; to set minimum standards for education, including the contents in textbooks and curricula, methods of teaching, school discipline, health and safety and professional requirements for teachers; obligation to ensure that the education system conforms to human rights values.

Adaptability

Obligation to design and implement education for children excluded from formal schooling, including “second chance”, where necessary (for dropouts, refugees or internally displaced children, street or working children, nomadic children, migrants); obligation to adapt education to the best interests of each child, especially those with special needs, or minority and indigenous children; obligation to apply the indivisibility of human rights and the right to education in education programmes as a guide to action.

As Govinda and Bandyopadhyay caution in their article on India, deeper structural constraints in society at large and in the educational system, as well as the nexus of many interacting influences, remain formidable obstacles. The special initiatives and affirmative measures have stumbled at these systemic and structural obstacles.

The optimism expressed regarding India also can be echoed for South Asia. While the challenge extends beyond the education system, the structural obstacles are likely to become less formidable, as each country in the region makes headway in fulfilling its vision of becoming a modern and progressive nation, overcoming abject poverty and gross inequities, and taking its rightful place among nations globally and in the region. Thus the region will lay the foundation for achieving UPE, if not by 2015, then soon after.

At the same time, as Sen says in concluding his commentary, the problems are serious and involve long-standing injustice to millions of young children; therefore, “Patience can be, alas, another name for continuing injustice”.

Notes

The Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transition and Equity (CREATE) postulated various “zones of exclusion”, corresponding to different forms of exclusion from education and categories of children affected by clusters of exclusionary factors (Lewis 2007).

References

Ahmed, M. (2009). The education challenges: Priorities for the Sixth Plan. Background paper prepared for the Sixth Plan. Dhaka: Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies.

Ahmed, M., Ahmed, K. S., Khan, N. I., & Ahmed, R. (2007). Access to education in Bangladesh: Country analytic review of primary and secondary education. CREATE Country Analytic Review. Brighton: University of Sussex.

Aslam, M. (2007). The relative effectiveness of government and private schools in Pakistan: Are girls worse off? RECOUP Working Paper 4. Oxford: Oxford University.

Government of India (2001). National Census Statistics. http://censusindia.gov.in/Tables_Published/SCST/scst_main.html.

Govinda, R., & Bandyopadhyay, M. (2008). Access to elementary education in India: Country analytical review. CREATE Pathways to Access Series. New Delhi and Brighton: CREATE-NUEPA. http://www.create-rpc.org/pdf_documents/India_CAR.pdf.

Lewin, K. (2007). Improving access, equity and transitions in education: Creating a research agenda. CREATE Pathways to Access Series, No. 1. Brighton: CREATE.

Pratham. (2007). Annual status of education report (rural) 2006. New Delhi: Pratham. http://pib.nic.in/release/release.asp?relid=23947&kwd=.

Sandkull, O. (2005). Strengthening inclusive education by applying a rights-based approach to education programing. Bangkok: UNESCO.

Tilak, J. (2010). On the Right to Education Act. [Posting on the National Forum of India on yahoogroups.co.in]. http://educationworldonline.net/index.php/page-article-choice-more-id-2288.

Tomasevski, K. (2004). Manual on rights-based education. Bangkok: UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2008). South and West Asia regional overview. Background paper for EFA Global Monitoring Report 2008. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO & UNICEF. (2007). A human rights-based approach to Education for All. New York and Paris: UNICEF and UNESCO.

Venkataith, S. (1999). Adult and modern education. In S. Venkataith (Ed.), Encyclopedia of contemporary education (pp. 67–68). New Delhi: Anmol Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, M., Govinda, R. Introduction. Prospects 40, 321–335 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-010-9165-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-010-9165-3