Abstract

In 2013, Brazil’s Ministry of Health adopted the Strengthening Families Program (SFP 10–14), developed internationally for preventing drug abuse by enhancing family bonds. The social validity of the objectives, procedures, and perceived impacts of the program were investigated for participants and facilitators in northeastern Brazil. Focus groups with parents/guardians (N = 199), adolescents (N = 111), and facilitators (N = 100) were implemented. Content analysis revealed that the program’s objectives were considered socially relevant and that there was a positive short-term perceived impact on family cohesion, authoritative parenting style, adolescent life skills, and the facilitators’ professional capacity. The parents/guardians and adolescents presented a positive perception of the appropriateness of the program’s methodology, while facilitators indicated the need to adapt it to vulnerable families and improve its implementation conditions. Future studies may benefit from these findings when developing similarly viable and scalable interventions in low-resource settings. Brazilian Trial Register RBR-7q9xh5. Registered 5 August 2017, http://www.ensaiosclinicos.gov.br/rg/RBR-7q9xh5/

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Substance abuse is recognized as an important health risk factor. According to the III National Survey on Drug Use by the Brazilian Population, for the 12- to 65-year-old group, approximately 2.3 million people had an alcohol dependence problem in the 12 months preceding the survey, and in the same period, around 1.2 million individuals were physically dependent on some illegal substance (Bastos et al. 2017). Results of this study pointed out harmful consequences of substance abuse for the health of Brazilians, especially injuries and deaths from traffic accidents, violence-related perpetration, and victimization. Young people between 18 and 24 years old were the most involved in violent episodes, compared with other age groups. In addition, with regard to the adolescent public, 814,000 adolescents had consumed illicit drugs in their lifetime and 468,000 in the last 12 months. The concomitant use of alcohol and tobacco in the 12 months preceding the study was reported by more than one million adolescents, and almost 400,000 adolescents reported combined use of alcohol and at least one illicit substance. These findings indicate the relevance of implementing preventive interventions, particularly aimed at adolescents.

In view of the absence of effective local interventions to prevent drug abuse, then available (Abreu and Murta 2016), in 2013, the Brazilian Ministry of Health adopted internationally developed and evidence-based prevention programs (Murta et al. 2018; Pedroso and Hamann 2019; Sanchez et al. 2018; Schneider et al. 2016) to compose the range of preventive strategies of the National Drug Policy that were then enforced. Among them, the American intervention Strengthening Families Program (SFP 10–14) (Kumpfer et al. 1989; Molgaard et al. 1995) was adopted, the most implemented family-based preventive program in Latin America (Mejía et al. 2019). The decision to adopt a family-based preventive program was founded on a growing body of evidence that has shown that the relationship between parents and children constitutes a protective factor against substance use and misuse when characterized by supervision, communication, support, and involvement, while parental negligence increases adolescent drug abuse (Mynttinen et al. 2017; Yap et al. 2017). Because of this, parent-based interventions (Hurley et al. 2019; Ladis et al. 2019; Newton et al. 2017) and family-based interventions (Pedersen et al. 2019; Van Ryzin et al. 2016) have been implemented and disseminated around the world, targeting the protection of adolescent health.

The Brazilian version of SFP 10–14 was named Programa Famílias Fortes (Strong Families Program). As in the original version, it comprises seven 2-h sessions for parents and adolescents (aged 10 to 14) separately, followed by joint parents and adolescent sessions. In addition, four booster sessions are implemented at 3 and 12 months after the seven regular sessions. Its theoretical basis is formed by the model of family systems, bioecological theory, attachment theory, and family resilience model. In line with its theoretical basis, it adopts the motto “love and limits,” as its primary focus is the strengthening of the authoritative parenting style in parents and legal guardians, with the caregiver’s high sensitivity (“love”) and demand (“limits”). Additionally, it aims to develop a future time perspective, social skills for resisting peer pressure, and stress management skills in adolescents, as well as cohesion, values, identity, emotions regulation, and collaborative problem resolution in the family (Kumpfer 2014). SFP 10–14 was designed to increase family, parental, and child-adolescent protective factors and, as a result, prevent long-term negative outcomes in the adolescents’ health.

The diffusion of a program to strengthen family ties from its original cultural context to another, quite different, raises questions about the program’s feasibility, effectiveness, and sustainability in the new context (Barrera et al. 2017; Gardner et al. 2016; Kumpfer et al. 2018). This is particularly relevant when implemented in complex circumstances as a broad-reaching tool of public policies (Aarons et al. 2017), as for instance in Brazil. Except for Peru (Castro and Bustamante 2013), there are no records regarding the implementation of SFP 10–14 as a tool of public policy, which makes the conclusive comparative analysis difficult. Publications that evaluate the effectiveness of SFP 10–14 in Peru have not been found.

There is mixed evidence about the effectiveness of SFP 10–14 to strengthen protective family factors, derived from implementations across the world and unrelated to public policies. On the one hand, studies with American families identified improvement in parenting practices (Coatsworth et al. 2010, 2015). Similarly, the quality of family relationships was improved in studies with Puerto Rican families (Chartier et al. 2010), Chilean families (Correa et al. 2012), and Panamanian families (Mejía et al. 2014). On the other hand, the studies failed to detect effects on parenting skills or parent-child relationship improvements in Polish families (Foxcroft et al. 2017) and revealed a worsening of parental hostility and parental problem-solving skills in American families (Semeniuk et al. 2010). Such conflicting results may derive from multiple reasons, such as insufficient theorizing concerning the intervention mechanisms in the new context, mismatches between contextual resources and intervention requirements (Movsisyan et al. 2019), cultural sensitivity gaps in the intervention for families of different socioeconomic levels (Pedersen et al. 2019), and deficits in the implementation process or inconsistencies in measures, procedures, or evaluation designs (Mejía et al. 2019).

Contradictory results have also been reported in substance abuse outcomes (Gorman 2017). While the original studies with the American population found evidence of effectiveness, randomized clinical trials conducted by independent teams with Polish families (Foxcroft et al. 2017) and German families (Baldus et al. 2016) failed to replicate the findings of those studies, showing null effects. Several possibilities could explain such phenomena, known as the decline effect (Gorman 2017). First, it seems that the use of distinct data analysis strategies between the original and adapted versions of SFP 10–14 constitutes one reason for the different results (Gorman 2017). Second, the implementation fidelity losses, such as reducing the number of family meetings and the inclusion of adolescents unaccompanied by their parents, may have had a negative impact on the results, as was found in a Swedish study (Skärstrand et al. 2014). Third, the program may be effective for some populations and not for others if cultural adaptation ignores relevant protective factors for families from the new culture, different from those of the original culture (Mejía et al. 2019). Finally, one can speculate about the role of contextual factors (Waltz et al. 2019): the inadequacy of the support system (such as gaps in supervision and training) and the program offering infrastructure (for example, a lack of organizational capacity in the services responsible for implementation), whose fragility could theoretically threaten the implementation and, as a consequence, the effectiveness of preventive programs.

In 2013, Brazil’s Ministry of Health selected the Social Assistance Reference Center as the initial space for implementing the SFP 10–14. The Social Assistance Reference Center is a service member of the then ongoing National Policies of Social Assistance, which should inform and facilitate access to social assistance, guarantee interaction spaces, and develop the autonomy and empowerment of economically disadvantaged families (Brasil, Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome 2012). The Social Assistance Reference Center was chosen to implement SFP 10–14 by virtue of the compatibility between its objectives and SFP 10–14’s target audience. After the initial study that assembled the cultural adaptation needs (Murta et al. 2018) and a cultural adaptation process performed by the Ministry of Health, the large-scale implementation of SFP 10–14 was undertaken. Between 2014 and 2017, the implementation of SFP 10–14 was managed jointly by the Ministry of Health and the National Secretary for Drug Policies and executed by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation. It was implemented in an intersectoral manner, in which the municipalities articulated their message at the Social Assistance Reference Center, basic health care units, public schools, and other similar social facilities. By the end of 2017, when its implementation was interrupted by the management of the Ministry of Health and National Secretary for Drug Policies, SFP 10–14 had reached eight Brazilian states, among them, four northeastern states—Ceará (CE), Pernambuco (PE), Rio Grande do Norte (RN), and Sergipe (SE)—the targets of this study.

In this study, the goal was to investigate the social validity of SFP 10–14 through the perceptions of its participants and facilitators. Social validity studies are meant to analyze the social relevance of public health intervention goals, the appropriateness of their strategies, and the social significance of their impact, as perceived by the target audience (Halle 2019). With that in mind, the objective of this study was to describe the participants’ and facilitator’s perceptions of (a) social relevance of SFP 10–14 vis-à-vis its participants’ needs, (b) the appropriateness of its methodology to the target audience, and (c) the social significance of its effect on the adolescent, parents, and family protective factors and on the practices of professionals and services.

We hope this study will expand the findings of previous studies by synthesizing data coming from multiple informants about the social validity of SFP 10–14 as a tool of public policies, something not often seen in studies in this field. It is likely that the findings of this study will show to what extent SFP 10–14, in Brazil, fulfilled one criterion of high-quality public policies, namely, consideration of the public interest (Howlett 2019). Following this, by listening to the participating parents and adolescents as well as the facilitators, this study aims to determine if and how SFP 10–14 meets the demands of the target audience and affects the health protective factors based on the perspective of those who know it best. Furthermore, due to the scarcity of locally developed evidence-based drug abuse preventive interventions in Latin American countries (Mejía et al. 2019), particularly in Brazil (Abreu and Murta 2016), this study gains relevance by producing inputs in the form of “lessons learned” applicable to an agenda of cultural adaptation research or development of similar socially valid social interventions for implementation in a context with scarce resources.

Methods

Participants

This transversal and qualitative study had 199 parents/guardians, 111 adolescents, and 100 facilitators. Focus groups were conducted separately: parents/guardians (N = 48 groups), adolescents (N = 35 groups), and facilitators (N = 23 groups). Focus groups ranged in size from 2 to 8 parents/guardians (mode = 3), 2 to 9 adolescents (mode = 3), and 2 to 9 facilitators (mode = 3). Parents/guardians were primarily women and mothers (97.4%) with an average age of 40.2 years (SD = 11.2). The most of the adolescents were boys (58.6%), average age 11.6 years. The majority of participants came from low-income families. The facilitators were professionals connected to Social Assistance Reference Centers, public schools, and basic health care units and had an average age of 36.2 (SD = 9.4), where 87% of these facilitators were female.

Intervention

SFP 10–14 was implemented, as intended in its original format, in separate sessions for parents/guardians and children/adolescents in the first hour, and for families in the second hour, totaling seven sessions of 120 min each. The themes addressed included as follows: love and limits, goals and dreams (session 1); rules and limits, admiration for the family members (session 2); incentive to good behavior, stress management, collective leisure (session3); rules and limits, family values (session 4); resistance skills to resist pressure from friends, empathic listening, emotional regulation (session 5), protection against substance abuse, friendship quality, resistance skills to resist pressure from friends (session 6); and social support network, joint resolution of problems, and community resources (session 7). Timed procedures, described in a manual adapted to Brazil (Brasil, Ministério da Saúde 2014), comprising several playful activities and group discussions were executed, some of them after presenting videos depicting episodes of family interaction, along with written tasks and homework. At the end of each session, the families were offered a snack. Although booster sessions should be offered between 3 and 12 months after the seventh regular meeting as per the original version of SFP 10–14, in Brazil, they were implemented between 1 and 3 months after that meeting. Booster sessions were conducted in less than half of the groups (18 to 33% of those in the states of PE, RN, and SE; CE uninformed) and recalled previous themes.

The implementation of each session required at least three facilitators, two to conduct the session for children/adolescents, one for the parents/guardians, and all three in the family sessions. While the original program anticipates the participation of both parents/guardians, i.e., a ratio of two (2) adults for one (1) adolescent, the Brazilian implementation included both parents/guardians per adolescent in slightly more than half of the cases (56.2%). All the facilitators were trained before the implementation and supervised throughout a project under the responsibility of Oswaldo Cruz Foundation. The usual place for the implementation was the Social Assistance Reference Centers, even if professionals associated with public education and health were also part of the implementation team. The implementation location needed to have two rooms available for simultaneous use as well as a TV and DVD equipment. As suggested by the original intervention (Molgaard et al. 1995), a caretaker for children under 10 years of age (not assisted by SFP 10–14) was also provided.

Instruments and Data Collection Procedures

Scripts for the focus groups with parents/guardians, adolescents, and facilitators were developed for data collection based on research questions and the literature on social validity (Francisco and Butterfoss 2007). The Parent/Guardian Focus Group Script included 12 questions about their satisfaction regarding the (a) fit between their needs and the content of SFP 10–14, (b) methodology of SFP 10–14, and (c) the effects perceived in their lives in the parental sphere (effects on parental role), family sphere (effects on family function), school sphere (effects on the school life of adolescents and children), and community sphere (effects on the family’s ties with the other group members, neighborhood, equipment, and community service).

The Adolescent Focus Group Script had three parts: (a) four initial questions to retrieve memories of the adolescents about their SFP 10–14 experience, what they liked most, what they liked least, and where they thought the intervention needed to improve; (b) five questions about the transfer of skills learned to the adolescents’ daily life in environments such as school, family, dating, and friendship; and (c) four questions about difficulties applying the content learned in the SFP 10–14 meeting to daily life. To trigger discussion, the focus groups with adolescents used cards containing images referent to each of the relational contexts: “family,” “friends,” “school,” “dating,” and “future.”

Finally, the Facilitators Focus Group Script had three questions exploring (a) the facilitators’ perceptions of positive changes caused by SFP 10–14 in the adolescents, families, professionals, and services; (b) negative changes resulting from SFP 10–14 to any of the above domains; and (c) absence of changes, described as desired effects that had not occurred by the end of the program. These questions were used as triggers to explore the facilitators’ positive or negative perceptions about the compatibility between the objectives and the families’ needs, and the adequacy of the methodology. While the last two questions allowed gaps to emerge between the family’s goals and needs and problems in the methodology of the intervention, the first question was to identify positive perceptions.

The focus groups held in the states of PE, RN, and SE were conducted up to 3 months after the end of the seventh regular SFP 10–14 meeting, while in CE, up to 12 months after. Participants were recruited using a face-to-face invitation at the end of the seventh regular meeting of SFP 10–14 or by telephone. The focus groups were held in public facilities, such as schools or Social Assistance Reference Centers. The groups were led by trained researchers. The parent/guardian focus groups lasted between 11 and 78 min (average = 30 min), the adolescent focus groups lasted between 9 and 39 min (average = 21 min), and the facilitator focus groups lasted between 22 and 90 min (average = 45 min). The sessions were audio-recorded and then transcribed. The focus groups were conducted, transcribed, and analyzed in Portuguese, then translated to English for publication. The focus group transcripts for parents/guardians totaled 180,333 words; 49,445 words for adolescents; and 126,932 words for facilitators.

All participants were properly informed about the research process and gave their consent to participate through the separate consent forms for adolescents versus parents/guardians and facilitators. This study was submitted to and approved by the Committee for Research Ethics of Human and Social Sciences of the University of Brasilia and executed in accordance with Resolution No. 510/2016.

Data Analysis Procedures

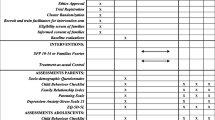

Data analysis was performed by content analysis (Bengtsson 2016). The transcripts of the focus groups were submitted to successive readings, which identified categories and subcategories for each of the dimensions investigated: social validity of objectives; social validity of procedures; social validity of effects on family, parents, and adolescent protective processes; and social validity of effects on facilitators and services.

Table 1 shows the definitions of these dimensions, which guided the decision on reports considered to be high or low social validity. In each of these dimensions, categories and subcategories related to high and low social validity were identified, from which the frequency counting from the group reports proceeded. Then, the frequencies of high and low validity reports across social validity categories represent the number of groups which reported that specific comment and not based on the individual respondents inside each group. All group reports that responded to the investigated dimensions were counted and considered units of meaning, regardless of their number or size, which varied from one sentence to a set of sentences with homogeneous meanings. The categories of social validity effects were partially based on family protective factors described in the theory of family resilience (Henry et al. 2015).

Categorization of the data was performed by independent coders and disagreements that arose were resolved consensually. The coders had expertise in mixed evaluation methods of adolescent preventive interventions. The coders training included three work sessions lasting 6 h to discuss the research questions, social validity studies, and family resilience literature (Henry et al. 2015). Member checking was the strategy used to assess the data trustworthiness (Lincoln and Guba 1985). The category system was discussed with the facilitators from the four states (CE, PE, RN, and SE) so they could judge whether the data corresponded to what they had actually experienced or, in other words, the accuracy and credibility of the categories and subcategories. No divergence was detected.

Results

Social Validity of Objectives: Does the SFP 10–14 Present Goals Relevant to the Needs of Its Target Audience?

According to facilitators and parents/guardians, SFP 10–14 is mostly compatible with several of the needs of families. Parents/guardians noted the appropriateness of SFP 10–14 objectives as regards the strengthening of family cohesion and parenting skills. However, one group remarked that SFP 10–14 does not address youth professionalization needs. Facilitators listed a wide number of relevant objectives, beyond those cited by the participants, including the strengthening of services and adolescent life skills (Table 2).

The relevance of SFP 10–14’s goal of promoting parenting skills and its compatibility with local needs is illustrated by the reports of a mother and a facilitator, respectively:

[…] the program helped me, I improved a lot, because the program helped me to be more patient, not shouting all the time. Also, things should be based on conversation, not beating someone. Because beating someone up doesn’t solve anything, really. [My son] gets even more rebellious. He was always getting beaten up, then yeah, the program did help a lot this way, like in conversation about patience, that’s why I say it changed my life a lot and his too. (Mother, Focus Group 16)

In my eyes, I think there was a closeness in the parent-child relationship, between the guardian and the child, […]I guess the mother learned how to deal better with her son, how to ask if everything is ok, if he did okay in school, something […] that hadn’t happened[before]. I feel that with the application of this project there was a lot of improvement in this issue of knowing how to talk. (Facilitator, Focus Group 2)

Social Validity of Procedures: Does SFP 10–14 Present the Proper Methodology for Its Target Public?

For the most part, the parents/guardians and adolescents reported the appropriateness of the SFP 10–14 methodology, while facilitators perceived it as being less appropriate, with an overall decontextualization of material, language that was too difficult for less-educated participants to understand, and excessive structuring. These results are described in Table 3.

Elevated social validity can be observed in the reports of a mother and a facilitator, respectively:

I liked the videos, they showed us a lot […]. The wonderful team [of facilitators], they explained every little thing. (Mother, Focus Group 26)

It’s a program that has a methodology, like, very complete, in the sense that the family is not gonna get here and get BSed. You can’t BS, you really have to make it happen. If you follow what is actually in the manuals it works out. (Facilitator, Focus Group 9)

On the other hand, gaps or inadequacies in SFP 10–14’s methodology can be seen in the reports below:

I guess we gotta have another person that looks at us, right? I loved it all. The meal was very good, I didn’t fall asleep, I read everything right away. Great book, great content. It’s just that I don’t know, something was missing really. Someone to closely do a follow up. This was very short. It should be like a school, that’s what’s missing, that happens every week, the whole year. What I think is that in so little time we saw so much change, we changed so much, at home, but it still could be better. (Mother, Focus Group 3)

The first sessions… there were families who didn’t get into it, like, on account of that. Because the video, it’s a little unrealistic, right? And there’s the whole question of them being uneducated, they feel embarrassed. (Facilitator, Focus Group 10)

Social Validity of Effects: Does SFP 10–14 Produce a Socially Relevant Impact for Families, Parents, and Adolescents?

According to reports by parents/guardians, adolescents, and facilitators, the evidence of perceived high-impact social validity of SFP 10–14 largely exceeded that perceived for low social validity, as shown by the number of categories and frequency of reports for each (Table 4). The effects perceived as positive were categorized according to protective processes related to life skills, control, emotion, and school. Facilitators, parents/guardians, and adolescents consistently reported the beneficial short-term impacts on the strengthening of family cohesion, authoritative parenting style, and the adolescents’ life skills.

Overall, the adolescents highlighted the development of assertive social skills and resistance to peer pressure:

“Also at school, today, my classmates asked me to go to another corner after school, and I said ‘No, I’m going home, I have to go home.’” (Adolescent, Focus Group 3)

Parents/guardians and facilitators pointed to the boost in the family’s emotional regulation as the most evident impact:

They cited examples, one I remember: “we wanted to watch the same thing at the same time on TV, then it occurred to us that it could be a good time to talk.” There were reports like that, everyday things they did […] “He wanted to do this thing and I remembered I shouldn’t overreact.” This type of report is simple, but it’s where we can see that it made a difference at times, daily, real life examples, that the father reported he had to keep calm, try it another way […]. (Facilitator, Focus Group 4)

Moreover, in the family environment, the parents/guardians reported clear improvements that set rules and limits, teaching responsibility and respect for authority (family protective factors related to control), and improving confidence, affection, empathy, and communication (family protective processes related to emotion) (Henry et al. 2015) (Table 4):

If I hadn’t participated I wouldn’t have learned to be more patient, set more limits, that everything the boys want to do we would allow and agree to. (Mother, Focus Group 12)

Although less frequent, improvements in school performance have also been reported, as seen in this report:

I had problems at school. Low grades. This is over. It was really confusing and the grades plunging. With my daughter it changed. I haven't been called back since. It seems that things have really improved her mind. And the grades are great. (Mother, Focus Group 4)

Among the low social validity categories, there were virtually no reports of worse behavior in adolescents or caretakers. Reports of low impact due to low achievement and high dropout rates are more frequent, as reported by the facilitators:

By assisting ten families we won’t resolve the problems of millions, right? But we’re in those…baby steps, and little by little trying to change reality. But we are in a situation where baby steps don’t work anymore. We see families being completely ripped apart, because of alcohol, drugs, prostitution, child labor, the countless vulnerabilities that exist on this earth, and we see that the baby steps (…) are important, but it’s not fulfilling the real need of Brazilian families. (Facilitator, Focus Group 6)

It was hard getting them to come, to show up, we had to do an active search every week. They [...] liked the program, when they were here “I love it” [...], they got involved [...]. Then next week, then it was the same, we had to go after them in their homes. (Facilitator, Focus Group 11)

The parents/guardians, in turn, pointed to the absence of change as the clearest indicator of low social validity, but lower in frequency relative to indicators of high social validity (Table 4).

Man, nothing changed, no. He keeps rebelling in the same way. (Mother, Focus Group 39)

Social Validity of Effects: Does SFP 10–14 Present Socially Relevant Impacts for Facilitators and Services?

The facilitators reported that the experience had had a positive impact on their professional abilities, including, firstly, group management skills. They also indicated having gained knowledge about drug abuse prevention (Table 5).

For me, I rediscovered myself as a facilitator, because facilitating groups was hard for me before, I just tried. And Programa Famílias Fortes pushed me ahead, to get organized, to facilitate. The tools also helped a lot, so, for me, it was positive. It was a win professionally, […] I learned a lot, even with the difficulties. Professionally, it bore fruit. (Facilitator, Focus Group 5)

On the other hand, the facilitators reported feeling significantly overwhelmed because of the time required to plan activities, prepare materials, and study the training material, and by the length of the program. They noted that the service routine was not amenable to inserting a new activity. According to them, many things conspired for this to happen, such as insufficient management support; inadequate physical infrastructure and lack of resources (for example, televisions); insufficient planning, monitoring, and supervision; deficient communications; and competing interests among the involved public agencies. SFP 10–14 became “one more activity” to be carried out by an insufficient team, already reduced in comparison with the existing workload, in the eyes of the facilitators, as can be seen in the following account:

I felt overwhelmed because we had to deal with the program and the activities of the Social Assistance Reference Center. So that when we talked about Tuesday, everyone was, “Ah, Tuesday, a really tiring day” (laughs). We weren’t able to schedule a team meeting on Tuesday, because Social Assistance Reference Center was really dynamic, so if something happened on Monday, on Tuesday there was no time to talk. Because when you arrived at 7 o’clock the meeting was right at 8 and then you had to separate the material […]. Then it took up the whole morning, since after the sessions we did the planning and so Social Assistance Reference Centers kept me offline all day. (Facilitator, Focus Group 11)

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that SFP 10–14 is perceived by the majority of focus groups of parents/guardians and facilitators as compatible with the needs of Brazilian families in vulnerable circumstances, and present positive initial effects, indicated by the consensus of parents/guardians, adolescents, and facilitators. They reported SFP 10–14 effects that are well tracked with their theoretical basis (Kumpfer 2014; Molgaard et al. 1995), being aligned with life skills and family protective processes related to emotion (love, the first motto of the program) and control (limits, its second motto) (Henry et al. 2015). Such positive results in family protective factors are in agreement with those found in various international studies, including US samples (Coatsworth et al. 2010, 2015) and Latin American ones (Chartier et al. 2010; Correa et al. 2012; Mejía et al. 2014). Evidence for iatrogenic effects on participants were sparsely reported or virtually absent, similar to most international studies, with the exception of one US study that found worsened parental functioning (Semeniuk et al. 2010).

The positive impacts were also noted in the professional practice of implementation agents who highlighted gains in their skills to manage groups. This is considered a relevant effect, as evidence indicates that such skills act to facilitate group cohesion and positive changes in SFP 10–14 parents in a US sample (Elreda et al. 2015). The facilitators related improvement in understanding drug abuse prevention, based on increasing protective factors, such as the quality of parental and family relationships, in lieu of providing information about the substance and its effects (Hurley et al. 2019; Mynttinen et al. 2017; Yap et al. 2017).

While evidence for high social validity of SFP 10–14 objectives and effects was greater overall than that for low social validity, there was mixed evidence for the methodological social validity. Parents/guardians and adolescents gave predominantly positive evaluations of SFP 10–14 procedures, content, and materials, while the facilitators perceived various deficiencies in the intervention, such as overstructure, decontextualization, and inappropriateness for less-educated families (Menezes et al. 2020). Moreover, they evaluated that SFP 10–14 implementation was heavy, stressful, and incompatible with the service routine. These findings reveal the need to adapt the intervention and the system in which it is inserted. This is a highly complex process, named by Aarons et al. (2017) as type III of scaling-out, in which an intervention is transported to a target audience and the delivery system is different from those in which it was originally tested. In summary, the results indicate that the intervention needs to be more compatible with the families’ education; the organizational capacity of the services must be adequately provided; and there should be ongoing supervision and training for facilitators.

Future SFP 10–14 adaptation efforts for Brazilian families may benefit from the findings of a recent systematic literature review that examined the adaptation of complex population health interventions for a new context (Movsisyan et al. 2019). According to these findings, the intervention theory, generalized evidence of intervention effects on different contexts, and differences between the local infrastructure available and requirements for intervention implementation should be taken into account. If such conditions are considered, a new version of the intervention could be produced with greater feasibility, less implementation burden, and less work overload for facilitators. In addition, it is vital to have the involvement of multiple stakeholders that include implementers, local community leaders, experts in family and adolescent health, intervention developers, practitioners, policymakers, parents, and adolescents from vulnerable contexts. This is consistent with the evidence that applying participatory approaches, active engagement of a range of implementers and the target community, and tailoring the scaled-up approach to the local context, among other factors, are favorable for scaling up public health interventions (Milat et al. 2015). This is notably relevant in a diverse country such as Brazil. Such participatory process could favor the ownership of intervention, collaboration, commitment, and support, and therefore maximize the chances of success in enrolment and retention of families, which are important challenges identified in the present study.

The data indicate that it is not only enough to adapt SFP 10–14, but also necessary to provide the conditions for its routinization in services, with the potentiality of undermining its scalability. Therefore, it is suggested that future studies examine the contextual barriers to the enablers for the implementation of SFP 10–14 (Pfandenhauer et al. 2017) as well as its interaction with support and delivery systems (Segrott et al. 2017). Along these lines, the evidence could favor selecting customized implementation strategies to contextual barriers (Waltz et al. 2019). In the same vein, the low achievement and high dropout rates reported by the implementation agents as impact hurdles warrant subsequent studies. As regards the first one, difficulties in reaching and recruiting families for SFP 10–14 were also identified in a Welsh study (Segrott et al. 2017). Other reasons concern the challenges of recruiting families with profiles that are compatible with universal prevention measures (as opposed to families with illnesses or pre-existing risk profiles). The second reason concerns evidence from an international study (Coatsworth et al. 2018) that examined the engagement of participating parents and indicated that better-educated parents and parents more involved in a parent-child relationship were more absorbed in the first session of the intervention. This study revealed that marital status (having a partner) and involvement in and quality of the relationship with the child at the baseline predicted greater engagement in the sessions. These demographic, relationship, and other socioeconomic variables (for example, education) should be considered in studies analyzing possible predictors of engagement in at-risk Brazilian families.

Finally, the focus groups of facilitators consensually reported SFP 10–14 as relevant for promoting parental and life skills, although its effects are restricted due to the numerous needs of the community, the services, and the at-risk families. This was expressed, for example, in one of the focus groups for parents/guardians, in which the need to professionalize adolescents was pointed out as relevant, but not covered by the SFP 10–14. Such findings reveal, therefore, the urgency for adopting and implementing sustainable, integrated social policies capable of systematically reducing inequities and embracing the diverse needs of vulnerable contexts (Garcia et al. 2014), as is the case with northeastern Brazilians and impoverished families in general. Furthermore, the barriers of SFP 10–14 regarding its insertion into the Social Assistance Reference Centers work routine and the overloading of facilitators reveals the importance of strengthening these services and their teams, which is a determining condition not only for the implementation of, but also for the adoption and maintenance of SFP 10–14 within related services.

The participation of multiple informants is considered a primary source of methodological robustness in the present study. Through this, consensus and peculiarities were identified among the participants and facilitators. A second relevant methodological characteristic was inserting questions into the instruments about the absence of change and/or negative changes, which could have reduced the social desirability in data collection and provided a more complete picture of the social validity of SFP 10–14 objectives, procedures, and perceived impacts. On the other hand, the time to collect data in three of the four states (within 3 months after the seventh session) was a limitation which may have impeded identifying impacts in contextual and distal spheres, such as changes in the community, foreseen in the theory of SFP 10–14 actions but not identified in this study. A second limitation is the lack of differentiation between groups regarding the effects on social validity with and without booster sessions. The short evaluation time in the three abovementioned states impeded the comparison of the social validity impacts in groups with and without booster sessions. Meanwhile, in the state of Ceará, it was possible, but was not done.

In 2017, the implementation of SFP 10–14 as a public policy tool in Brazil was halted at the federal level, precociously, prior to the evidence of its viability (Murta et al. accepted) and effectiveness (Murta et al. 2020) for Brazilian families was available. It is not known to what extent the interruption of political support at the federal level impacted the sustainability of the program at the municipal level. It would be productive if future studies examined the evidence of sustainability of SFP 10–14 in the municipalities that have adopted it within a range of possibilities from the most to the least optimistic, such as the continuity in implementing SFP 10–14 in services for vulnerable families or similar services, incorporating parts of the program in these or other services, keeping the topic on the political agenda or the absence of SFP 10–14 impact in the services and professional practice of facilitators (Scheirer and Dearing 2011). Equally informative would be identifying the determinants of such outcomes (Schell et al. 2013). This may provide insights into the sustainability of SFP 10–14 as a public policy strategy to prevent drug abuse, something that is still unknown worldwide.

Overall, the implementation experience of the Brazilian SFP 10–14 as a public drug abuse prevention policy strategy suggests its appropriateness given the needs of families, and perceived short-term positive impacts on participants and facilitators. The mixed evidence for high and low methodological social validity in the implementation context indicates that its strengths and weaknesses should be taken into consideration equally. The data can underpin double-pronged research agendas. Firstly, new waves of cultural adaptation should seek to make SFP 10–14 more sensitive to vulnerable contexts, more understandable for parents with little or no education, and more flexible for facilitators. Secondly, these findings might fuel the creation of local interventions with socially valid objectives and procedures that are potentially more viable, effective, scalable, and sustainable for its implementation in resource-poor contexts (Mejía et al. 2019). In both cases, it is suggested that the composition of the committees be mixed, with multiple stakeholders, to better adapt to the interests of the various public actors involved.

References

Aarons, G. A., Sklar, M., Mustanski, B., Benbow, N., & Brown, C. H. (2017). “Scaling-out” evidence-based interventions to new populations or new health care delivery systems. Implementation Science, 12(111). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0640-6.

Abreu, S., & Murta, S. G. (2016). O estado da arte da pesquisa em prevenção em saúde mental no Brasil: uma revisão sistemática. Interação em Psicologia, 20, 101–111.

Baldus, C., Thomsen, M., Sack, P. M., Bröning, S., Arnaud, N., Daubmann, A., et al. (2016). Evaluation of a German version of the Strengthening Families Programme 10-14: a randomised controlled trial. European Journal of Public Health, 26, 953–959.

Barrera, M., Berkel, C., & Castro, F. G. (2017). Directions for the advancement of culturally adapted preventive interventions: local adaptations, engagement, and sustainability. Prevention Science, 18, 640–648.

Bastos, F. I. P. M., Vasconcellos, M. T. L., De Boni, R. B., Reis, N. B., & Coutinho, C. F. S. (2017). III Levantamento Nacional sobre o Uso de Drogas pela População Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: ICICT/FIOCRUZ.

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nursing Plus Open, 2, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001.

Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. (2014). Programa Famílias Fortes: Versão brasileira adaptada do “Strengthening Families Programme” – SFP 10-14 UK (G. C. Justino et al., Trad.). Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, Coordenação de Saúde Mental, Álcool e Drogas.

Brasil, Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome. (2012). Orientações Técnicas sobre o PAIF. Brasília: MDS, Secretaria Nacional de Assistência Social.

Castro, A., & Bustamante, I. (2013). Rutas de aprendizaje del Programa Familias Fuertes: amor y límites sistematización y propuesta de evaluación de la experiencia Peruana del Programa Familias Fuertes: amor y límites. Retrieved September 10,2018, from: http://www.comunidadandina.org/StaticFiles/2013214121126Familias_Fuertes.pdf.

Chartier, K. G., Negroni, L. K., & Hesselbrock, M. N. (2010). Strengthening family practices for Latino families. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 19, 1–17.

Coatsworth, J. D., Duncan, L. G., Greenberg, M. T., & Nix, R. L. (2010). Changing parent’s mindfulness, child management skills and relationship quality with their youth: results from a randomized pilot intervention trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 203–217.

Coatsworth, J. D., Duncan, L. G., Nix, R. L., Greenberg, M. T., Gayles, J. G., Bamberger, K. T., et al. (2015). Integrating mindfulness with parent training: effects of the Mindfulness-Enhanced Strengthening Families Program. Developmental Psychology, 51, 26–35.

Coatsworth, J. D., Hemady, K. T., & George, M. W. (2018). Predictors of group leaders’ perceptions of parents’ initial and dynamic engagement in a family preventive intervention. Prevention Science, 19, 609–619.

Correa, M. L., Zubarew, T., Valenzuela, M. T., & Salas, F. (2012). Evaluación del programa “Familias fuertes: amor y límites” en familias con adolescentes de 10 a 14 años. Revista Médica de Chile, 140, 726–731.

Elreda, L. M., Coatsworth, J. D., Gest, S. D., Ram, N., & Bamberger, K. (2015). Understanding process in group-based intervention delivery: social network analysis and intra-entity variability methods as windows into the “black box”. Prevention Science, 17, 925–936.

Foxcroft, D. R., Callen, H., Davies, E. L., & Okulicz-Kozaryn, K. (2017). Effectiveness of the Strengthening Families Programme 10-14 in Poland: cluster randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Public Health, 27, 494–500.

Francisco, V. T., & Butterfoss, F. D. (2007). Social validation of goals, procedures, and effects in public health. Health Promotion Practice, 20, 1–6.

Garcia, L., Kinoshita, R. T., & Maximiano, V. (2014). Uma perspectiva social para o problema do crack no Brasil: implicações para as políticas públicas. In F. I. Bastos & N. Bertoni (Eds.), Pesquisa nacional sobre o uso de crack: quem são os usuários de crack e/ou similares do Brasil? Quantos são nas capitais brasileiras? (pp. 147–155). Rio de Janeiro: ICICT/FIOCRUZ.

Gardner, F., Montgomery, P., & Knerr, W. (2016). Transporting evidence-based parenting programs for child problem behavior (age 3–10) between countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45, 749–762.

Gorman, D. M. (2017). The decline effect in evaluations of the impact of the Strengthening Families Program for Youth 10-14 (SFP 10-14) on adolescent substance use. Children and Youth Services Review, 81, 29–39.

Halle, J. (2019). Avoiding the humdrum: recommendations for improving how we conceptualize and assess social validity in ECSE. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 39, 139–143.

Henry, C. S., Morris, A. S., & Harrist, A. W. (2015). Family resilience: moving into the third wave. Family Relations, 64, 22–43.

Howlett, M. (2019). Designing public policies: principles and instruments. London: Routledge.

Hurley, E., Dietrich, T., & Rundle-Thiele, S. (2019). A systematic review of parent based programs to prevent or reduce alcohol consumption in adolescents. BMC Public Health, 19, 145.

Kumpfer, K. (2014). Family-based interventions for the prevention of substance abuse and other impulse control disorders in girls. ISRN Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/308789.

Kumpfer, K. L., DeMarsh, J. P., & Child, W. (1989). Strengthening families program: children’s skill curriculum manual, parent training manual, children’s skill training manual, and family skills training manual (prevention services to children of substance-abusing parents). Salt Lake City: Department of Health, Alcohol and Drug Research Center.

Kumpfer, K. L., Scheier, L. M., & Brown, J. (2018). Strategies to avoid replication failure with evidence-based prevention interventions: case examples from the Strengthening Families Program. Evaluation & the Health Professions. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278718772886.

Ladis, B. A., Macgowan, M., Thomlison, B., Fava, N. M., Huang, H., Trucco, E. M., et al. (2019). Parent-focused preventive interventions for youth substance use and problem behaviors: a systematic review. Research on Social Work Practice, 29, 420–442.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Mejía, A., Ulph, F., & Calam, R. (2014). An exploration of parents’ perception and beliefs about changes following participation in a family skill training program: a qualitative study in a developing country. Prevention Science, 16, 674–684.

Mejía, A., Bertello, L., Gil, J., Griffith, J., López, A. I., Moreno, M., et al. (2019). Evaluation of family skills training programs to prevent alcohol and drug use: a critical review of the field in Latin America. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00060-x.

Menezes, J. C. L., Nobre-Sandoval, L., & Murta, S. G. (2020). Local adaptations to implement the Strengthening Families Program in northeastern Brazil. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 407–421.

Milat, A. J., Bauman, A., & Redman, S. (2015). Narrative review of models and success factors for scaling up public health intervention. Implementation Science, 10(113). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0301-6.

Molgaard, V., Kumpfer, K., & Fleming, E. (1995). The Iowa Strengthening Families Program. Ames: University Extension, Iowa State University.

Movsisyan, A., Arnold, L., Evans, R., Hallingberg, B., Moore, G., O’Cathain, A., et al. (2019). Adapting evidence-informed complex population health interventions for new contexts: a systematic review of guidance. Implementation Science, 14(105). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0956-5.

Murta, S. G., Nobre-Sandoval, L. A., Pedralho, M. S., Tavares, T. N. G., Ramos, C. E. P. L., Allen, D., et al. (2018). Needs assessment for cultural adaptation of Strengthening Families Program (SFP 10-14-UK) in Brazil. Psychology: Research and Review, 31(25). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-018-0105-0.

Murta, S. G., Vinha, L. G. A., Nobre-Sandoval, L. A., Rocha, V. P. S., Duailibe, K. D., Gomes, M. S. M., et al. (2020). Exploring the short-term effects of the Strengthening Families Program on Brazilian Adolescents: a pre-experimental study. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy, 27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2020.1769030.

Murta, S. G., Vinha, L. G. A., Nobre-Sandoval, L. A., Miranda, A. A. V., Menezes, J. C. L., & Rocha, V. P. S. (accepted). Feasibility of the Strengthening Families Program for Brazilian families: a mixed method study. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa.

Mynttinen, M., Pietilä, A., & Kangasniemi, M. (2017). What does parental involvement mean in preventing adolescents’ use of alcohol? An integrative review. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 26, 338–351.

Newton, N. C., Champion, K. E., Slade, T., Chapman, C., Stapinski, L., Koning, I., et al. (2017). A systematic review of combined student- and parent-based programs to prevent alcohol and other drug use among adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Review, 36, 337–351.

Pedersen, G. A., Smallegange, E., Coetzee, A., Hartog, K., Turner, J., Jordans, M. J., et al. (2019). A systematic review of the evidence for family and parenting interventions in low-and middle-income countries: child and youth mental health outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2036–2055.

Pedroso, R. T., & Hamann, E. M. (2019). Adequações do piloto do programa Unplugged#Tamojunto para promoção à saúde e prevenção de drogas em escolas brasileiras. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 24, 371–381.

Pfandenhauer, L. M., Gerhardus, A., Mozygemba, K., Lysdahl, K. B., Booth, A., Hofman, B., et al. (2017). Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: the context and implementation of complex interventions (CICI) framework. Implementation Science, 12, 21.

Sanchez, Z. M., Valente, J. Y., Sanudo, A. S., Pereira, A. P. D., Schneider, D. R., & Andreoni, S. (2018). Effectiveness evaluation of the school-based drug prevention program #Tamojunto in Brazil: 21-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Drug Policy, 60, 10–17.

Scheirer, M. A., & Dearing, J. W. (2011). An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 2059–2067.

Schell, S. F., Luke, D. A., Schooley, M. W., Elliot, M. B., Herbers, S. H., Mueller, N. B., & Bunger, A. C. (2013). Program public health capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implementation Science, 8(15). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-15.

Schneider, D. R., Pereira, A. P. D., Cruz, J. I., Strelow, M., Chan, G., Kurki, A., et al. (2016). Evaluation of the implementation of a preventive program for children in Brazilian schools. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 36, 508–519.

Segrott, J., Murphy, S., Rothwell, H., Scourfield, J., Foxcroft, D., Gillespied, D., et al. (2017). An application of Extended Normalisation Process Theory in a randomized controlled trial of a complex social intervention: Process evaluation of the Strengthening Families Programme (10–14) in Wales, UK. SSM Population Health, 3, 255–265.

Semeniuk, Y., Brown, R. L., Riesch, S. K., Zywicki, M., Hopper, J., & Henriques, J. B. (2010). The Strengthening Families Program 10–14: influence on parent and youth problem-solving skill. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 17, 392–402.

Skärstrand, E., Sundell, K., & Andréasson, S. (2014). Evaluation of a Swedish version of the Strengthening Families Programme. The European Journal of Public Health, 24, 578–584.

Van Ryzin, M. J., Roseth, C. J., Fosco, G. M., Lee, Y., & Chen, I. (2016). A component-centered meta-analysis of family-based prevention programs for adolescent substance use. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 72–80.

Waltz, T. J., Powell, B. J., Fernández, M. E., Abadiel, B., & Damschroder, L. J. (2019). Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future direction. Implementation Science, 14(42). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0892-4.

Yap, M. B. H., Cheong, T. W. K., Zavarinos-Tsakos, F., Lubman, D. I., & Jorm, A. F. (2017). Modifiable parenting factors associated with adolescent alcohol misuse: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Addiction, 112, 1142–1162.

Funding

Support for this study has been provided by the National Secretary for Drug Policies, Ministry of Justice and Public Safety from Brazil.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Committee for Ethics in Human and Social Sciences of the University of Brasília (CAAE 53103516.1.0000.5540) and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all of the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murta, S.G., de Almeida Nobre-Sandoval, L., Rocha, V.P.S. et al. Social Validity of the Strengthening Families Program in Northeastern Brazil: the Voices of Parents, Adolescents, and Facilitators. Prev Sci 22, 658–669 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01173-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01173-9