Abstract

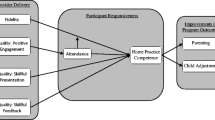

We examined attendance trajectories among mothers and fathers in the effectiveness trial of the New Beginnings Program, a parenting-focused prevention program for divorced and separated parents. We also investigated attendance trajectory class differences on two sets of pretest covariates: one set previously linked to participation in programs not specifically targeting divorced parents (i.e., sociodemographics, perceived parenting skills, child problem behaviors, parent psychological distress) and another that might be particularly salient to participation in the context of divorce (i.e., interparental conflict, level of parent-child contact, previous marital status to the ex-spouse). For mothers and fathers, results supported four attendance trajectory classes: (1) non-attenders (NA), (2) early dropouts (ED), (3) declining attenders (DA), and (4) sustained attenders (SA). In the final model testing multiple covariates simultaneously, mothers who were EDs and DAs were more likely to be Latina than SAs, and EDs reported more interparental conflict than SAs. Mother trajectory groups did not differ on parenting skills, child problem behavior, or mother-child contact in the final or preliminary models. In the final model for fathers, EDs rated their children higher on externalizing than DAs, had less contact with their children than DAs and NAs, and reported less distress than SAs. Father trajectory groups did not differ on fathers’ age, ethnicity, income, perceived parenting skills, or interparental conflict in the final or preliminary models. Results highlight qualitatively distinct latent classes of mothers and fathers who disengage from a parenting intervention at various points. We discuss implications for intervention engagement strategies and translational science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Parenting quality is linked to positive child outcomes across development and multiple domains, including mental and physical health, substance use, and academic achievement (Collins et al. 2000). The importance of parenting quality is particularly salient during times of stress, as evidenced by research showing that effective parenting is an important protective factor for children exposed to family and life stressors, such as poverty and the divorce or death of parents (Leon 2003). Given its impact on child outcomes and its malleability, parenting quality is often targeted for change in interventions for families facing normative stressors as well as adversity (Sandler et al. 2011; Wolchik et al. 2013).

As prevention science has increased its focus on the translation of evidence-based parenting programs (EBPs) to real-world delivery settings, how to effectively engage and sustain parent participation has emerged as a significant challenge (Spoth et al. 2013). Research suggests that fewer than 20% of targeted parents will participate when programs are delivered under real-world conditions (Fagan, Hanson, Hawkins, & Arthur, 2009; Prinz et al. 2009; Spoth, Clair, Greenberg, Redmond, & Shin, 2007). This has important implications because the public health impact of EBPs depends on the extent to which parents can be successfully engaged to participate in these interventions (Spoth et al. 2013).

Research Examining Parent Intervention Participation

There is a considerable amount of research on predictors of participation in parenting interventions (Gopalan et al. 2010), but much of this research has focused on mothers. There is much less research on predictors of father participation (Fabiano 2007; Panter-Brick et al. 2014). Prevention scientists’ limited understanding about the predictors of fathers’ participation is a critical gap because both mothers’ and fathers’ quality of parenting significantly impact children (Lamb 2004). Moreover, due to changing social and cultural norms and an economic context in which mothers are joining the workforce at higher rates (Lundberg and Pollak 2007), fathers are spending more time with their children and are a growing consumer base for parenting interventions. Sustainable translation depends on consumer uptake, so failure to engage fathers is a major impediment to scale-up of parenting EBPs (Spoth et al. 2013).

Because life stressors can compromise parenting quality (Farmer and Lee 2011), engaging parents in parenting interventions during times of stress and understanding factors that predict their participation in this context is important. Parenting quality has a significant impact on children’s post-divorce adjustment (Leon 2003) and understanding predictors of participation in parenting interventions during divorce may be particularly important. Divorced parents may be particularly vulnerable to divorce-related attendance barriers, such as economic strain, access to their children, and interparental conflict. Research on fathers’ participation in parenting interventions during divorce or separation is timely because divorced fathers are spending more time with their children due to changing court practices that increasingly promote gender equality in assignment of parenting time following divorce (Cancian et al. 2014). Moreover, there is robust evidence that the father-child relationship has a significant impact on children’s post-divorce adjustment (Sandler et al. 2012).

This study addresses important gaps in the literature by examining whether covariates at pretest predicted father as well as mother participation in the effectiveness trial of the New Beginnings Program (NBP), an intervention for divorcing or separating parents. Most studies examining father participation have done so in the context of family-centered interventions in which both mothers and fathers were invited to participate, but recruitment largely targeted mothers and father participation was considered ancillary (Panter-Brick et al. 2014). The NBP’s efforts and strategies to recruit mothers and fathers were equivalent. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine covariates of participation in separate father and mother samples that were recruited with the same strategies for separate, gender-specific but parallel programs.

Attendance Trajectory Classes

Participation involves multiple phases: enrollment, initiation, and retention (Winslow et al. 2009). This study focuses on initiation, which we define as attending at least one session, and retention, which we define as attendance over time. Most previous studies have operationalized attendance as dichotomous (attended vs. did not attend) or as the number of sessions attended (e.g., Dillman Carpentier et al. 2007; Prado et al. 2006; Winslow et al. 2009), but these operationalizations fail to elucidate patterns of attendance through the course of the intervention. Some recent studies have used probability-based methods to explore unobserved (or latent) classes of mothers with similar attendance trajectories in a preventive intervention (Mauricio et al. 2016; Mauricio et al. 2014). Modeling attendance trajectories and covariates associated with class membership helps identify parents who are vulnerable to declines in attendance and when they are vulnerable. Because parents who disengage early may differ from those who disengage later, identifying patterns of attendance and profiling parents that fit these patterns can inform who should be targeted when for strategies that enhance participation. This study extends previous studies that focused exclusively on mothers by modeling both mother and father attendance trajectories and examining how trajectory groups differ on covariates at pretest. Based on extant research (Baker et al. 2011; Coatsworth et al. 2006; Mauricio et al. 2014; Mauricio et al. 2016), we hypothesized four trajectory groups: (1) non-attenders (i.e., parents who attend zero sessions), (2) early drop outs, (3) variable attenders (i.e., parents who attend irregularly), and (4) sustained attenders.

Attendance Trajectory Covariates

Covariates included a set of pretest variables previously linked to parent participation in programs that do not specifically target divorced parents: sociodemographics (i.e., parent education level, age, ethnicity, and income), parent perceptions of parenting skills, child problem behaviors, and parent psychological distress. Further, we included previous legal marital status to the ex-spouse (married vs. never married) as a divorce-specific sociodemographic variable that may affect participation, and we also examined interparental conflict and level of parent-child contact as barriers to intervention participation that may be particularly salient for parents in the context of divorce. We drew from intervention participation research and psychological theory to inform hypotheses about the relations between the covariates and participation.

Sociodemographics

Consistent with prior research, we expected less education and lower age to be associated with less participation (Morawska and Sanders 2006). Some studies have found that ethnic minority parents participate less (Baker et al. 2011), whereas others found non-significant relations (Gross et al. 2001). In this study, 32% (n = 154) of parents were Latino, allowing us to examine how Latino and non-Latino parents differed in participation. Because language can function as a proxy for acculturation (Dillman Carpentier et al. 2007) and the NBP was offered in English only, we anticipate that participating Latino parents were highly acculturated. Based on previous research suggesting that highly acculturated parents are less likely to initiate participation and, if they do initiate, attend fewer sessions (Dillman Carpentier et al. 2007), we hypothesized that Latino parents in the NBP were more likely to be non-attenders and early dropouts than variable and sustained attenders. Consistent with research showing that economic strain and income-related barriers (e.g., reliable transportation) deter participation (Snell-Johns et al. 2004), we expected low income to be a participation barrier. Never-married mothers tend be more economically disadvantaged than married mothers (Gibson-Davis et al. 2005) and also have less access to their former partners’ resources when the relationship ends (Seltzer 2000); thus, we expected never-married mothers to have fewer resources and more income-related barriers and to participate at lower rates than those that had been married. Because paternal investment is higher for married than unmarried fathers (Hofferth 2006), we expected fathers who had never married the child’s mother to be less likely to initiate participation than fathers who had married the mother. We hypothesized that: (1) for mothers and fathers, non-attenders would be lower in age, education and income and more likely to be Latino vs. non-Latino compared to all other groups; (2) among mothers and fathers who initiated participation, early dropouts would be lower in age, education, and income and more likely to be Latino vs. non-Latino in comparison to variable and sustained attenders; (3) among mothers, non-attenders and early dropouts would be less likely than sustained and variable attenders to have been married to the co-parent; and (4) among fathers, non-attenders would be less likely to have been married than all other groups.

Parenting Skills

Mothers who rate their parenting as poor are more likely to participate in a parenting intervention, perhaps because they expect to yield more benefit than mothers who perceive themselves as good parents (Perrino et al. 2001). Consistent with prior research, we expected mothers who initiated and sustained participation in the NBP to rate their parenting skills as poorer than other mothers. Alternatively, given social norms that dissuade men from admitting personal limitations, we anticipated fathers who rate their parenting as poor to be less motivated than fathers who rate their parenting as good to attend a group-based parenting intervention, where they might be asked to discuss their parenting and acknowledge perceived shortcomings (Addis and Mahalik 2003). If fathers who rate their parenting as poor do initiate participation, they may be more likely to drop out early. We hypothesized that: (1) among mothers, non-attenders would rate their parenting higher than all other groups; (2) among mothers who initiated participation, early dropouts would rate their parenting higher than sustained and variable attenders; (3) among fathers, non-attenders would rate their parenting lower than all other groups; and (4) among fathers who initiated participation, early dropouts would rate their parenting lower than variable and sustained attenders.

Child Problem Behaviors

Mothers who perceive their child as having problem behaviors enroll in parenting interventions at higher rates than those who do not because they expect to gain more from the program (Perrino et al., 2001). Although parents of high-risk children initiate participation at high rates (Winslow et al. 2009), sustaining participation may be a challenge for these parents (Kazdin et al. 1997). Stress associated with parenting a child with problem behaviors or parents’ unrealistic and unmet expectations for immediate behavior change prompts dropout. For mothers and fathers, we hypothesized that: (1) non-attenders would rate their child lowest on problem behaviors and (2) among parents who initiate participation, early dropouts and variable attenders would rate problem behaviors higher than sustained attenders.

Parent Psychological Distress

Because a parenting intervention may be perceived as a resource for support, parent distress may motivate initial participation; however, the sadness, hopelessness, and other symptoms that accompany psychological distress may interfere with sustained participation. Research shows that depressed mothers are more likely than non-depressed mothers to initiate participation, but they do not sustain participation (Mauricio et al. 2014). Studies with non-divorced fathers show that psychological distress did not relate to participation (Wong et al. 2013). However, in the context of divorce, distress may motivate fathers to participate because, unlike women who have support networks extending beyond their spouse, men often rely on their spouse or partner (Cutrona 1996). In this regard, fathers may be motivated to participate in a parenting program, particularly a fathers’ only program, to seek support for divorce-related psychological distress. We hypothesized that: (1) among mothers and fathers, non-attenders would report less distress than all other groups; (2) among mothers who initiate participation, early dropouts and variable attenders would report more distress than sustained attenders; and (3) among fathers who initiate participation, sustained and variable attenders would report more distress than early dropouts.

Interparental Conflict

Because interparental conflict takes psychological and other resources, it may minimize parent capacity to engage in an intervention (Staudt 2007). Among non-divorced parents, high levels of interparental conflict link to less participation (Wong et al. 2013). Because the co-parents’ relationship is often characterized by conflict during divorce (Amato 2000), interparental conflict may be a salient divorce-specific participation barrier. This may be especially true for fathers for whom interparental conflict can provoke “maternal gatekeeping,” which limits father-child contact and may discourage engagement in a parenting intervention (Pruett et al. 2006). For mothers and fathers, we hypothesized that: (1) non-attenders would report the most conflict, and (2) among parents who initiated participation, early dropouts would report more conflict than sustained and variable attenders.

Parent-Child Contact

Among separated and divorced parents, level of parent-child contact may be a particularly influential correlate of intervention participation, with less contact linked to less participation. Parents with little parent-child contact may perceive themselves as having little influence in changing their child’s behavior and thus be less motivated than parents with lots of contact to initiate participation. Among parents that initiate participation, too little parent-child contact may prohibit practice of program skills and lower parenting efficacy, which may be a disincentive for sustained participation. The influence of parent-child contact may be particularly salient for divorced and separating fathers who experience considerable variability in level of parent-child contact (Cancian et al. 2014; Melli and Brown 2008). For mothers and fathers, we hypothesized that: (1) non-attenders would have less contact than all other groups and (2) early dropouts would report less contact than sustained and variable attenders.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data were from 477 parents enrolled in the NBP effectiveness trial and randomized to the 10-session NBP. Most (86.6%) parents were the sole parent enrolled in the effectiveness trial, but 64 (32 pairs; 16.8%) were divorcing or separating from another participating parent. The effectiveness trial was conducted in partnership with four county-level family courts in Arizona. The majority of parents (83.4%) were recruited from 4-h parent information programs (PIP), during which parents viewed a video inviting them to participate in the NBP. In addition, 16.6% of parents in the NBP were referrals from judges or lawyers, self-referrals, or recruited via media announcements. Although PIPs are mandated for all divorcing parents in Arizona, participation in the NBP was voluntary and free. There were 50 same-gender groups across four cohorts (276 mothers in 26 groups; 201 fathers in 24 groups). Eligible parents (1) must have sought divorce, separation, or court assistance with a formal parenting plan in the 2 years prior to recruitment; (2) had at least one 3- to 18-year-old child with whom they had a weekly minimum of 3 h of contact or an overnight every other week; (3) were not remarried; (4) were able to participate in English; and (5) were not mandated to a parenting class by Child Protective Services or the Juvenile Court. Parents with multiple eligible children completed all measures for a randomly selected “target child” and a briefer battery for other children. With the exception of attendance, this study used parents’ report on themselves and their target child (47.2% female) at pretest.

Measures

Table A1 in the online appendix reports the mean, standard deviation, and correlations among all pretest measures, separately for mothers and fathers.

Sociodemographics

Parents reported their current gross family income (ordinal from 1 = $10,000 or less to 21 = more than $200,000), age (continuous), ethnicity (self-identified as Latino = 1, 32.3%; non-Latino = 0), legal marital status prior to separation (1 = married, 86.2%; 0 = never married), and education level (ordinal from 1 = 1st grade to 19 = doctoral degree). Mothers and fathers were similarly educated, 7.2% of mothers and 8.0% of fathers did not graduate from high school, 8.3 and 8.5% graduated from high school, 56.2 and 46.8% completed some college or vocational training, and 28.3 and 36.8% earned a bachelor’s degree or higher. The median gross family income at pretest was between $20,000 and $30,000 for mothers, but between $40,000 and $50,000 for fathers. Of the 154 Latino parents, 120 (77.9%) reported being Mexican, Mexican American, or Chicano; 6 (3.9%) reported being Puerto Rican; and 28 (19.2%) reported being of another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.

Parenting Skills

We assessed two parenting dimensions, parent-child relationship quality and discipline, using factor scores from a two-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model estimated in Mplus 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2014).

-

Parent-child relationship quality. Indicators of parent-child relationship quality included involvement measured by the 9-item Involvement scale (e.g., going to a movie; Menning, 2006), parent-child communication measured by the 10-item Open Communication scale (Barnes and Olson 1982; α = 0.81), parent-child closeness, family routines measured by a 7-item adaptation of the Family Routines Inventory (Jensen et al. 1983; α = 0.81), and acceptance measured by a parent report version of the Child Report of Parenting Behavior Inventory (CRPBI) 16-item Acceptance subscale (Schaefer 1965; α = 0.87).

-

Discipline. Indicators of discipline were consistency, as measured by the CRPBI 8-item Consistent Discipline subscale (α = 0.84), follow-through, as measured by the 11-item Oregon Discipline Follow-Through subscale (α = 0.80), and appropriate use of discipline based on a ratio of 9 items assessing appropriate (α = 0.74) to total discipline use (Oregon Social Learning 1991).

-

CFA model. When fitting the two-factor model, we allowed involvement and family routines to correlate due to their conceptual similarity and acceptance and discipline consistency to correlate, as they were measured by items on the same scale. The two-factor model closely fit the data: χ 2(17) = 69.86; RMSEA = 0.06, 90% CI (0.05, 0.08) (Steiger 1989); CFI = 0.96 (Bentler 1990), TLI = 0.94 (Tucker and Lewis 1973), and SRMR = 0.05 (Bollen 2014).

Child Problem Behaviors

We used T-scores from the Externalizing and Internalizing subscales of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; α = 0.90 and 0.89, respectively; Achenbach and Edelbrock 1983) and the Externalizing and Internalizing subscales of the Preschool Child Behavior Checklist (Pre-CBCL; α = 0.91 and 0.90, respectively; Achenbach and Rescorla 2000) to assess child problem behaviors. For both mother and father reports, mean T-scores for externalizing and internalizing (see Table A1) were comparable to normative samples.

Parent Psychological Distress

Parents completed the 27-item Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview (PERI) demoralization scale (Dohrenwend et al. 1980; α = 0.93) to assess non-specific psychiatric distress, including anxiety, sadness, helplessness, hopelessness, and psychophysiological symptoms. Roberts and Vernon (1981) found the demoralization scale related moderately to psychiatric diagnoses, particularly major depression, based on structured clinical interviews. The PERI demoralization scale has shown good reliability with other samples of divorced adults (e.g., Tein et al. 2000; α = 0.93).

Interparental Conflict

Parent completed the six frequency items (e.g., “In the past month, your children often saw you and [your ex] arguing.”) and nine intensity items (e.g., “In the past month, when you and [your ex] argued, you yelled a lot.”) from parent report of the Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale (Grych et al. 1992; α = 0.90). The scale was developed for use with children but has demonstrated adequate reliability for parent report (e.g., α = 0.68–0.91) and that parent and child reports are correlated (Kitzmann and Cohen 2003).

Parent-Child Contact

Parent-child contact was based on a single item: “In the last 30 days, how many days did you spend 2+ hours with [target child] while you were both awake?” The mean was 23.51 days (SD = 7.47) for mothers and 17.21 days (SD = 8.69) for fathers.

Attendance

Parent attendance (1 = attended, 0 = did not attend) at the NBP was reported by the group leader at the end of each session.

Data Analytic Strategy

We fit a series of latent class growth analysis (LCGA) models in Mplus 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2014), separately for mothers and fathers. LCGA searches for unobserved (or latent) classes of parents with similar attendance trajectories and estimates the posterior probability of parent membership in each class. For all models, we specified a logistic regression parameterization (because attendance is binary) and used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation. We used a sandwich estimator for the standard error computations to adjust for clustering by intervention group. Because all models were estimated separately for mothers and fathers, the standard errors were not adjusted to account for dependence between the 32 pairs of co-parents. We started with one class and successively increased the number of classes until we encountered serious convergence issues, indicating we were extracting too many classes. When extracting two or more classes, we forced parents who never attended to form one class by constraining the growth factor means to zero and the attendance thresholds to 15, which corresponds to an attendance probability of zero (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2014). The growth factor means were estimated freely in each of the remaining classes. For each k-class solution, we compared the results between a linear latent class growth model versus a quadratic latent growth model for each class. The attendance thresholds were constrained to be equal across sessions and across classes (except for the no attendance class). All of the growth factor variances and covariances were constrained to zero.

To avoid solution based on local optima, we specified 1000 initial stage and 100 final stage random sets of starting values and confirmed the best log-likelihood value was replicated multiple times. To select the optimal solution, we used the Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz 1978), sample size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SABIC; Sclove 1987), Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLMR LRT), Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (aLMR LRT; Lo et al. 2001), entropy (exceeding 0.80), and considered whether the classes were meaningfully different and substantively useful. The BIC and SABIC consider fit and parsimony, with lower values being favored. A significant (p < 0.05) VLMR LRT or aLMR LRT indicates the k-class solution improves fit relative to a solution with one less class. Entropy ranges from 0 to 1 and summarizes cases’ posterior probabilities of class membership; higher values indicating greater confidence in classification.

After selecting the optimal solution for mothers and for fathers, we tested the effects of the covariates using the R3STEP option for the AUXILIARY command in Mplus (Asparouhov and Muthén 2014; Muthén and Muthén 1998–2014; Vermunt 2010). First, we tested conceptually related covariates in groups (i.e., preliminary models): sociodemographics (parent age, education, ethnicity, income, and marital status),Footnote 1 perceived parenting skills (parent-child relationship quality and discipline), child problem behaviors (internalizing and externalizing), parent psychological distress, interparental conflict, and parent-child contact. Next, we tested the covariates that showed significant or marginally significant differences between two or more classes in the preliminary models in a single, final model for mothers and a single, final model for fathers, which we henceforth refer to as the “final model.”Footnote 2

Results

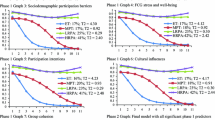

Table 1 summarizes the fit information for the LCGA models. For mothers and fathers, we selected a four-class solution while estimating a quadratic growth model in each class. The fit information suggested that three or four classes were viable (the BIC and SABIC were lower with four classes, but the VLMR LRT and aLMR LRT were non-significant), but extracting four classes allowed us to distinguish parents who dropped out very early from those who gradually dropped out. Figure 1 plots estimated probabilities of attendance for mothers and for fathers. Three of the four classes represented in Fig. 1 are consistent with hypotheses: non-attenders (NA; 24.0% of mothers vs. 15.8% of fathers), early dropouts (ED; 19.6 vs. 20.6%), and sustained attenders (SA; 44.5 vs. 55.2%). We labeled the fourth class as declining attenders (DA; 11.9 vs. 8.3%) rather than variable attenders because parents in this class initiated attendance in the NBP and then had a steady, gradual decline in attendance, rather than variable or irregular attendance throughout the NBP as hypothesized. A higher proportion of mothers than fathers never attended, χ 2(1) = 3.71, p = 0.05, but the mean number of sessions attended did not differ across mothers and fathers who attended at least one session (6.52 vs. 6.47, respectively).

When tested in conceptual groups, seven covariates showed significant or marginally significant differences between two or more classes for mothers and were retained for the final model: education, age, ethnicity, income, marital status, psychological distress, and interparental conflict (see Table B1 in the online appendix). In the preliminary models, parenting skills, child problem behavior, and mother-child contact did not predict class membership (see Table B1 in the online appendix). In the final model, ethnicity and interparental conflict were significantly associated with class membership; education, age, income, marital status, and distress were not. Compared to non-Latina mothers, Latina mothers were more likely to be EDs vs. SAs, z = 2.36, p = 0.02, and more likely to be DAs vs. SAs, z = 1.99, p = 0.05. Mothers who reported more interparental conflict were more likely to be EDs vs. SAs, z = 2.09, p = 0.04.

When tested in conceptual groups, six covariates showed significant or marginally significant differences between two or more classes for fathers and were retained for the final model: education, marital status, child internalizing problems, child externalizing problems, psychological distress, and father-child contact (see Table B2 in the online appendix). In the preliminary models, age, ethnicity, income, parenting skills, and interparental conflict did not predict class membership. In the final model for fathers, education, externalizing problems, distress, and contact with the child were significantly associated with class membership; marital status and internalizing problems were not. In the final model for fathers, education, externalizing problems, distress, and contact with the child distinguished class membership; marital status, internalizing problems, and distress did not. Fathers with less education were more likely to be NAs vs. SAs, z = −2.73, p = 0.01. Fathers who rated their child high on externalizing were more likely to be EDs vs. DAs, z = 2.42, p = 0.02. More distressed fathers were more likely to be SAs vs. EDs, z = 2.66, p = 0.01. Fathers with less contact with their child were more likely to be EDs vs. NAs, z = −2.27, p = 0.02, but also more likely to be EDs vs. DAs, z = −2.07, p = 0.04.

Discussion

This study used LCGA to examine attendance trajectories among recently divorced and separated mothers and fathers in the NBP effectiveness trial and examined how pretest covariates predicted class membership. We tested a set of covariates linked to participation in programs that do not specifically target divorced parents and a set of covariates we expected to be particularly salient in the context of divorce. For mothers and fathers, results supported four trajectories: (1) non-attenders (NA), (2) sustained attenders (SA), (3) declining attenders (DA), and (4) early dropouts (ED). Different covariates were associated with mothers’ and fathers’ class membership. For mothers and fathers, sustained attenders was the largest group (44 and 55%, respectively), indicating a large percentage of divorced parents will enroll and sustain participation in a 10-week parenting program. However, a large percentage of parents never attended or dropped out after three or fewer sessions (44% of mothers, 37% of fathers). From a public health perspective, this suggests the group-formatted NBP will fail to reach many families when offered on a voluntary and free basis to the general population of divorcing families. It also highlights the necessity of effective recruitment and retention strategies to optimize population-level impact when parenting interventions scale-up (Spoth et al. 2013). The finding that more mothers than fathers attended no sessions may suggest divorced mothers experience more attendance barriers than divorced fathers. It may also suggest divorced fathers are more likely than mothers to utilize external resources to manage post-divorce stress related to parenting.

Covariates Associated with Trajectory Group Membership

Mothers

In the final model, mothers who were Latina or who reported more interparental conflict dropped out of the NBP prematurely. Our finding that, among mothers initiating participation, Latina mothers were more likely to drop out was consistent with hypotheses. However, our hypothesis that Latina mothers would be less likely than non-Latina mothers to initiate participation was not supported. This finding suggests Latina mothers initiated participation as frequently as non-Latina mothers but they did not sustain participation. Retention among Latina mothers may have been higher if the NBP offered provider-parent ethnic match, culturally homogeneous intervention groups, or both; however, these program features were not feasible from a research design perspective or acceptable to the implementing agencies. Cultural homogeneity, which can increase group cohesion and increase attendance (Leszcz and Yalom 2005; Mauricio et al. 2014), may be particularly important for a parenting program, because parenting values may differ for Latinos and the majority culture (Domenech Rodriguez et al. 2009). Our result that SAs reported less interparental conflict than EDs was consistent with our hypothesis that high levels of interparental conflict would deter participation. Because the NBP offered only one session on interparental conflict, mothers with high conflict may have felt that the program was not meeting their needs, prompting them to drop out. Because interparental conflict can impede the capacity to parent effectively and is a strong predictor of child adjustment post-divorce (Sandler et al. 2008), our results are consistent with other studies suggesting that parents likely to receive the most benefit from an intervention are also most likely to drop out (Baker et al. 2011).

Fathers

Education, child externalizing, psychological distress, and level of parent-child contact were associated with class membership in the final model. Consistent with hypotheses, NAs were less educated than SAs. The NBP was particularly effective in reducing externalizing among high externalizing children in the efficacy trial (Wolchik et al. 2000), but in this study fathers who dropped out early rated their children high on externalizing. This may be because, based on the NBP’s theory, topics related to building positive parent-child relationships and effective listening are addressed first, with discipline addressed in later sessions. Fathers may perceive relationship building and communication skills as less immediately helpful in managing externalizing behaviors, prompting drop out. The finding that more distressed fathers had higher rates of attendance was also expected. Spouses and romantic partners are a primary support resource for men and, in the absence of this resource, men may seek support elsewhere (Cutrona 1996), such as from their NBP group. Although maternal psychological distress was not significant in the final model, in the preliminary model the effect of distress on mothers’ participation was directionally opposite to effects on fathers; mothers reporting high levels of distress more likely to be EDs or DAs than SAs (see Table B1). Because women rely on friends and family for support they may have less incentive to seek it elsewhere (Cutrona 1996). Our findings that EDs had less contact with their child than both NAs and DAs suggest that fathers with limited contact initiate but do not sustain their participation, perhaps because limited contact with their child is a barrier to doing home practice, which the NBP strongly emphasizes. Identifying fathers who have low levels of contact with their child at program initiation and addressing their participation barriers may help sustain their participation.

Limitations and Future Research

Mother and father sample sizes were modest, so limited power may have obscured small effects between covariates and class membership, particularly in the final models testing multiple, competing covariates simultaneously. Replicating this study with larger samples may identify additional characteristics of divorcing and separating parents that distinguish trajectories of participation. Another important area for future inquiry is why Latina mothers dropped out early. We are currently coding group dynamics in the NBP, which may offer insight into process-related factors that contributed to Latina mothers’ drop out. For example, because the program is highly structured and emphasizes providers teaching skills rather than providing open-ended support, providers may not have spent adequate time addressing mothers’ concerns and needs. This is counter to the value of “personalismo,” emphasizing personal connections, and may have contributed to Latina mothers’ drop out (Falicov 2009). Interestingly, ethnicity did not predict class membership for fathers.

Conclusions

This study is the first to examine covariates of participation among separate father and mother samples, recruited with the same strategies for independent, gender-consistent, parallel programs. Previous studies have examined father participation in the context of family-centered interventions that predominantly target mothers’ participation. Because fathers are a growing consumer base for parenting interventions, EBPs that do not engage their participation will fail to have the intended population impact during scale-up. Understanding factors affecting fathers’ participation in parenting interventions has significant public health implications (Spoth et al. 2013). This study is also the first to examine father participation in a parenting intervention in the context of divorce. Fathers are at-risk for disengaging from their children during divorce, so it is an important time to support their continued involvement (Maldonado 2005). For mothers and fathers, our results show that divorce-related barriers deter participation, suggesting it is important to consider context-related barriers to intervention participation. Studies such as this one that profile parent subpopulations that vary in the timing of intervention disengagement can inform timing and allocation of resources to implement participation-incentivizing strategies.

Notes

Because very few non-Latino parents reported races other than White (16 fathers and 23 mothers) and we could not justify hypotheses about this heterogeneous subsample of parents, we tested the sociodemographic covariates while including and excluding these parents. The results reported are based on the full sample because excluding non-Latino parents who reported races other than White did not appreciably change the results.

We chose to reduce the number of covariates entered into the final model, though we could have entered all 12 covariates simultaneously or interpreted the results from the models testing conceptually-related covariates (see Tables B1 and B2 in the online appendix). Although we developed hypotheses about the attendance classes and covariates related to the attendance classes, the analyses reported in this paper are largely exploratory. The formation of attendance classes was data-driven, and we tested several covariates potentially related to the attendance classes because very little research focuses on father initiation and retention in parenting interventions.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1983). Manual for the child behavior checklist and revised child behavior profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

Addis, M. E., & Mahalik, J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist, 58, 5–14.

Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 1269–1287.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model. Mplus Web Notes: No. 21.

Baker, C. N., Arnold, D. H., & Meagher, S. (2011). Enrollment and attendance in a parent training prevention program for conduct problems. Prevention Science, 12, 126–138.

Barnes, H., & Olson, D. H. (1982). Parent-adolescent communication scale. In D. H. Olson, H. I. McCubbin, H. Barnes, A. Larsen, M. Muxen, & M. Wilson (Eds.), Family inventories: Inventories used in a national survey of families across the family life cycle (pp. 33–48). St. Paul, MN: Family Social Science, University of Minnesota.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Bollen, K. A. (2014). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Cancian, M., Meyer, D. R., Brown, P. R., & Cook, S. T. (2014). Who gets custody now? Dramatic changes in children’s living arrangements after divorce. Demography, 51, 1381–1396. doi:10.1007/s13524-014-0307-8.

Coatsworth, J. D., Duncan, L. G., Pantin, H., & Szapocznik, J. (2006). Patterns of retention in a preventive intervention with ethnic minority families. Journal of Primary Prevention, 27, 171–193.

Collins, W. A., Maccoby, E. E., Steinberg, L., Hetherington, E. M., & Bornstein, M. H. (2000). Contemporary research on parenting: The case for nature and nurture. American Psychologist, 55, 218–232.

Cutrona, C. E. (1996). Social support in couples: Marriage as a resource in times of stress (Vol. 13). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dillman Carpentier, F. R., Mauricio, A. M., Gonzales, N. A., Millsap, R. E., Meza, C. M., Dumka, L. E., Germán, M., & Genalo, M. T. (2007). Engaging Mexican origin families in a school-based preventive intervention. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 28, 521–546.

Dohrenwend, B. P., Shrout, P. E., Egri, G., & Mendelsohn, F. S. (1980). Nonspecific psychological distress and other dimensions of psychopathology: Measures for use in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37, 1229–1236.

Domenech Rodriguez, M. M., Donovick, M. R., & Crowley, S. L. (2009). Parenting styles in a cultural context: Observations of “protective parenting” in first-generation Latinos. Family Process, 48, 195–210.

Fabiano, G. A. (2007). Father participation in behavioral parent training for ADHD: Review and recommendations for increasing inclusion and engagement. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 683–693.

Fagan, A. A., Hanson, K., Hawkins, J. D., & Arthur, M. W. (2009). Translational research in action: Implementation of the communities that care prevention system in 12 communities. Journal of Community Psychology, 37(7), 809-829.

Falicov, C. J. (2009). Commentary: On the wisdom and challenges of culturally attuned treatments for Latinos. Family Process, 48, 292–309.

Farmer, A. Y., & Lee, S. K. (2011). The effects of parenting stress, perceived mastery, and maternal depression on parent–child interaction. Journal of Social Service Research, 37, 516–525.

Gibson-Davis, C. M., Edin, K., & McLanahan, S. (2005). High hopes but even higher expectations: The retreat from marriage among low-income couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1301–1312.

Gopalan, G., Goldstein, L., Klingenstein, K., Sicher, C., Blake, C., & McKay, M. M. (2010). Engaging families into child mental health treatment: Updates and special considerations. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 19, 182–196.

Gross, D., Julion, W., & Fogg, L. (2001). What motivates participation and dropout among low-income urban families of color in a prevention intervention? Family Relations, 50, 246–254.

Grych, J. H., Seid, M., & Fincham, F. D. (1992). Assessing marital conflict from the child’s perspective: The Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale. Child Development, 63, 558–572.

Hofferth, S. L. (2006). Residential father family type and child well-being: Investment versus selection. Demography, 43, 53–77.

Jensen, E., Janes, S., Boyce, W. T., & Hartnett, S. A. (1983). The Family Routines Inventory: Development and validation. Social Science and Medicine, 17, 201–211.

Kazdin, A. E., Holland, L., Crowley, M., & Breton, S. (1997). Barriers to Treatment Participation Scale: Evaluation and validation in the context of child outpatient treatment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 1051–1062.

Kitzmann, K. M., & Cohen, R. (2003). Parents’ versus children’s perceptions of interparental conflict as predictors of children’s friendship quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 20, 689–700.

Lamb, M. E. (Ed.). (2004). The role of the father in child development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Leon, K. (2003). Risk and protective factors in young children’s adjustment to parental divorce: A review of the research. Family Relations, 52, 258–270.

Leszcz, M., & Yalom, I. (2005). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

Lo, Y., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88, 767–778.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. A. (2007). The American family and family economics (No. w12908). National Bureau of Economic: Research.

Maldonado, S. (2005). Beyond economic fatherhood: Encouraging divorced fathers to parent. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 153, 921–1009.

Mauricio, A. M., Tein, J.-Y., Gonzales, N. A., Millsap, R. E., & Dumka, L. E. (2016). Attendance patterns and links to non-response on child report of internalizing among Mexican-Americans randomized to a universal preventive intervention. Prevention Science. Advance online publication.

Mauricio, A. M., Tein, J.-Y., Gonzales, N. A., Millsap, R. E., Dumka, L. E., & Berkel, C. (2014). Participation patterns among Mexican–American parents enrolled in a universal intervention and their association with child externalizing outcomes. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54, 370–383.

Melli, M. S., & Brown, P. R. (2008). Exploring a new family form—the shared time family. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 22, 231–269.

Menning, C. L. (2006). Nonresident fathering and school failure. Journal of Family Issues, 27(10), 1356-1382.

Morawska, A., & Sanders, M. (2006). A review of parental engagement in parenting interventions and strategies to promote it. Journal of Children’s Services, 1, 29–40.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2014). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles: CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Oregon Social Learning, C. O. S. L. (1991). LIFT parent interview (unpublished manual). Eugene: Oregon Social Learning Center.

Panter-Brick, C., Burgess, A., Eggerman, M., McAllister, F., Pruett, K., & Leckman, J. F. (2014). Practitioner review: Engaging fathers—recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 1187–1212.

Perrino, T., Coatsworth, J. D., Briones, E., Pantin, H., & Szapocznik, J. (2001). Initial engagement in parent-centered preventive interventions: A family systems perspective. Journal of Primary Prevention, 22, 21–44.

Prado, G., Pantin, H., Schwartz, S. J., Lupei, N. S., & Szapocznik, J. (2006). Predictors of engagement and retention into a parent-centered, ecodevelopmental HIV preventive intervention for Hispanic adolescents and their families. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31, 874–890.

Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., Shapiro, C. J., Whitaker, D. J., & Lutzker, J. R. (2009). Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P system population trial. Prevention Science, 10, 1–12.

Pruett, M. K., Arthur, L. A., & Ebling, R. (2006). The hand that rocks the cradle: Maternal gatekeeping after divorce. Pace Law Review, 27, 709–739.

Roberts, R. E., & Vernon, S. W. (1981). Usefulness of the PERI demoralization scale to screen for psychiatric disorder in a community sample. Psychiatry Research, 5, 183–193.

Sandler, I., Miles, J., Cookston, J., & Braver, S. (2008). Effects of father and mother parenting on children’s mental health in high-and low-conflict divorces. Family Court Review, 46, 282–296.

Sandler, I. N., Schoenfelder, E. N., Wolchik, S. A., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2011). Long-term impact of prevention programs to promote effective parenting: Lasting effects but uncertain processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 299–329.

Sandler, I., Wolchik, S., Winslow, E. B., Mahrer, N. E., Moran, J. A., & Weinstock, D. (2012). Quality of maternal and paternal parenting following separation and divorce. In K. Kuehnle & L. Drozd (Eds.), Parenting plan evaluations: Applied research for the family court (pp. 85–122). New York: Oxford University Press.

Schaefer, E. S. (1965). Children’s report of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development, 36, 413–424.

Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6, 461–464.

Sclove, S. L. (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52, 333–343.

Seltzer, J. A. (2000). Child support and child access: Experiences of divorced and nonmarital families. In J. T. Oldham & M. S. Melli (Eds.), Child support: The next frontier (pp. 69–87). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Snell-Johns, J., Mendez, J. L., & Smith, B. H. (2004). Evidence-based solutions for overcoming access barriers, decreasing attrition, and promoting change with underserved families. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 19–35.

Spoth, R., Clair, S., Greenberg, M., Redmond, C., & Shin, C. (2007). Toward dissemination of evidence-based family interventions: maintenance of community-based partnership recruitment results and associated factors. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(2), 137.

Spoth, R., Rohrbach, L. A., Greenberg, M., Leaf, P., Brown, C. H., Fagan, A., Catalano, R. F., Pentz, M. A., Sloboda, Z., Hawkins, J. D., & Society for Prevention Research Type 2 Translational Task Force Members and Contributing Authors. (2013). Addressing core challenges for the next generation of type 2 translation research and systems: The translation science to population impact (TSci Impact) framework. Prevention Science, 14, 319–351.

Staudt, M. (2007). Treatment engagement with caregivers of at-risk children: Gaps in research and conceptualization. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16, 183–196.

Steiger, J. (1989). Causal modeling: A supplementary module for SYSTAT and SYGRAPH. Evanston, IL: Systat.

Tein, J. Y., Sandler, I. N., & Zautra, A. J. (2000). Stressful life events, psychological distress, coping, and parenting of divorced mothers: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 27.

Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38, 1–10.

Vermunt, J. K. (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18, 450–469.

Winslow, E. B., Bonds, D., Wolchik, S., Sandler, I., & Braver, S. (2009). Predictors of enrollment and retention in a preventive parenting intervention for divorced families. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 30, 151–172.

Wolchik, S. A., Sandler, I. N., Tein, J.-Y., Mahrer, N. E., Millsap, R. E., Winslow, E., Vélez, C., Porter, M. M., Luecken, L. J., & Reed, A. (2013). Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families: Effects on mental health and substance use outcomes in young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81, 660–673.

Wolchik, S. A., West, S. G., Sandler, I. N., Tein, J.-Y., Coatsworth, D., Lengua, L., Weiss, L., Anderson, E. R., Greene, S. M., & Griffin, W. A. (2000). An experimental evaluation of theory-based mother and mother-child programs for children of divorce. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 843–856.

Wong, J. J., Roubinov, D. S., Gonzales, N. A., Dumka, L. E., & Millsap, R. E. (2013). Father enrollment and participation in a parenting intervention: Personal and contextual predictors. Family Process, 52, 440–454.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Development and evaluation of the New Beginnings Program (NBP), including the data collected and used in this study, were supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse grant R01 DA026874.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Drs. Sandler and Wolchik are the developers of the NBP; Drs. Mauricio and Berkel have a grant (R01DA033991) to study implementation of the NBP; Drs. Sandler, Wolchik, Tein, Berkel, and Winslow were involved in the evaluation of the effectiveness of the NBP program. The authors declare that they have no other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All study procedures and measures were reviewed and approved by the Arizona State University Institutional Review Board. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study and assent was obtained from minors included in the study.

Additional information

This study was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse grant R01 DA026874.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 31 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mauricio, A.M., Mazza, G.L., Berkel, C. et al. Attendance Trajectory Classes Among Divorced and Separated Mothers and Fathers in the New Beginnings Program. Prev Sci 19, 620–629 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0783-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0783-3