Abstract

Educators are increasingly being encouraged to implement evidence-based interventions and practices to address the social, emotional, and behavioral needs of young children who exhibit problem behavior in early childhood settings. Given the nature of social-emotional learning during the early childhood years and the lack of a common set of core evidence-based practices within the early childhood literature, selection of instructional practices that foster positive social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes for children in early childhood settings can be difficult. The purpose of this paper is to report findings from a study designed to identify common practice elements found in comprehensive intervention models (i.e., manualized interventions that include a number of components) or discrete practices (i.e., a specific behavior or action) designed to target social, emotional, and behavioral learning of young children who exhibit problem behavior. We conducted a systematic review of early childhood classroom interventions that had been evaluated in randomized group designs, quasi-experimental designs, and single-case experimental designs. A total of 49 published articles were identified, and an iterative process was used to identify common practice elements. The practice elements were subsequently reviewed by experts in social-emotional and behavioral interventions for young children. Twenty-four practice elements were identified and classified into content (the goal or general principle that guides a practice element) and delivery (the way in which a teacher provides instruction to the child) categories. We discuss implications that the identification of these practice elements found in the early childhood literature has for efforts to implement models and practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many states across the USA provide early education programs for preschool-age children ages 3–5 years old to foster school readiness and reduce school failure. Unfortunately, 14–30 % of the children who enter these programs exhibit problem behavior (e.g., disruptive behavior; Barbarin 2007) and are without age-appropriate social and emotional skills, both of which impact their ability to benefit from early educational experiences (Feil et al. 2005). As a result, these children are at risk for long-term behavioral and academic problems (O’Conner et al. 2011). Despite the increased focus on providing high quality early childhood education to foster social-emotional learning and ameliorate problem behavior, many educators in early childhood settings struggle to deliver the interactional and instructional supports designed to prevent or ameliorate social-emotional learning deficits and associated problem behaviors. This has led some researchers to call for specific training and supports for early educators focused on social-emotional and behavioral interventions (Hemmeter et al. 2006).

A logical choice for improving the quality of early educators’ interactional and instructional support for young children with chronic problem behavior is for them to implement comprehensive intervention models (i.e., manualized interventions that include a number of practice components, henceforth called models) and discrete practices (i.e., a specific behavior or action, henceforth called practices) that target children in early childhood classrooms who demonstrate problem behavior and collateral social and emotional needs. The early childhood literature includes a few models that meet evidence-based criteria (e.g., Incredible Years; Webster‐Stratton et al. 2008), along with other models that have been identified as needing additional empirical support to be considered evidence-based (e.g., Second Step, Brown et al. 2012). Educators also have implemented discrete practices that have demonstrated positive social, emotional, or behavioral effects, typically through single case experimental designs (e.g., precorrective statement, Smith et al. 2010). Although a number of models and discrete practices exist, it can be a challenge for stakeholders to determine which models or discrete practices are the best fit for use with specific children in a particular early childhood setting (Powell and Dunlap 2009). This is due, in part, to the fact that there is no consensus in the literature about operational definitions for the practices that have been the subject of study. These definitional issues make it challenging to compare and contrast findings across studies and make it difficult for teachers to implement practices from models or discrete practices with integrity in early childhood settings.

Other fields have attempted to introduce systems for defining practices to facilitate communication related to intervention methodology and findings. In the mental health field, researchers have focused on defining practice elements (i.e., discrete principles or skills) that compose the models and practices evaluated within a specific literature (e.g., Chorpita and Daleiden 2009; Garland et al. 2008; Institute of Medicine 2015). The practice element approach, also called “therapeutic strategies” (i.e., goal or general principle that guides psychosocial treatment; Beutler and Baker 1998) and “evidence-based kernels” (i.e., units of behavior influence that cannot be reduced further without losing their function; Embry and Biglan 2008), presents a different perspective on how the evidence base can be defined and employed (Chorpita and Daleiden 2009; Chorpita et al. 2005; Garland et al. 2008). Instead of a focus on implementing practices from a single model, the elements approach argues for the efficiency of focusing on specific practice elements that are made from the practices used to create the models. In recent years, this approach has gained traction, as some assert that creating a common way to define the practices within a body of literature is key for implementation efforts (Fairburn and Patel 2014; Institute of Medicine 2015).

Two methods have been used to analyze the evidence base to identify practice elements in the mental health field. One approach developed by Chorpita and colleagues started with a codebook of predefined practice elements derived through stakeholder input, including practitioners and intervention developers (see Chorpita et al. 2005; Chorpita and Daleiden 2009). The set of practice elements was then compared to models for youth with emotional and behavioral problems, and the presence of those elements was coded. This approach is useful for cataloging the extent to which a set of common practice elements is represented across a broad literature. However, given that the practice elements are largely predetermined, this approach may not capture all practice elements within a given literature (Garland et al. 2008).

A second approach developed by Garland et al. (2008) starts without an explicit set of practice elements and works to extract practice elements from a target literature. In their paper (Garland et al. 2008), they focused on studies evaluating evidence-based programs (i.e., models that meet defined levels of empirical support) for youth aged 4–13 years old displaying disruptive behavior problems. Through successive iterative steps, they extracted 21 practice elements from eight studies. The approach demonstrated by Garland et al. is more likely to identify the full range of practice elements represented in a literature.

A comparison between the two approaches reveals some similarities. The seven most commonly represented practice elements identified by Chorpita et al. (2005) for disruptive behavior problems were mapped on to the list of practice elements produced by Garland et al. (2008). However, Garland et al. produced a more expansive list, likely due to their focus on identifying the full set of practices found in the empirical literature. Of course, the ideal number of practice elements identified may vary by the purpose. In some instances, knowing the entire range may be needed, whereas in other contexts, knowing a smaller set may prove more useful.

We are not aware of efforts to identify practice elements in the early childhood intervention literature for children who demonstrate social-emotional difficulties and problem behavior. An approach like Garland et al. (2008) took has several advantages as a first step in identifying practice elements in this literature. First, as noted earlier, there are no commonly accepted definitions for the social-emotional and behavioral practice elements used in early childhood classrooms that could be used to guide the development of a codebook. Second, we were interested in identifying all of the practice elements evaluated in the early childhood literature for models and practices designed to address social-emotional deficits and problem behaviors. Thus, we employed an approach most similar to the one used by Garland et al. to define practice elements.

We applied a modified version of the Garland et al. (2008) approach to identify practice elements in the early childhood social-emotional and behavioral intervention literature. Our primary goal was to determine if it was possible to extract and define a set of practice elements that represent the models and practices studied in the early childhood literature. We describe the process used to identify studies focused on models and practices that target young children aged 3–5 years old who have social, emotional, and behavioral learning needs and to distill from these studies common practice elements. Importantly, unlike previous efforts to identify practice elements in the mental health field, we did not attempt to differentiate practice elements by level of empirical support or exclude studies that failed to achieve positive effects. This decision was made based on the challenges of attempting to synthesize findings across group experimental and single-case research designs (see Shadish et al. 2015). This would require us to resolve challenges related to a quantitative synthesis of the data produced by the two research designs reviewed for this paper, which is beyond the scope of the current manuscript. Instead, we identified the practice elements found in the models and practices listed as having empirical support on the What Works Clearinghouse (ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/); Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL; www.casel.org/preschool-and-elementary-edition-casel-guide); and Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development (www.blueprintsprograms.com/) in order to highlight those practice elements that are associated with agreed upon standards of evidence in the field.

Method

Selection of Studies

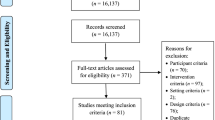

We conducted a literature search of published articles evaluating models or practices delivered in early childhood classrooms targeting young children with chronic problem behavior. A computer-based search was conducted using four electronic databases: (a) Education Research Information Center (ERIC), (b) PsycINFO, (c) Elton B. Stephens Company (EBSCO), and (d) Web of Knowledge (Social Science Citation Index). The search spanned January 2005 to August 2014; these dates were chosen to correspond with the 2005 publication of the National Research Council report that sought to advance scientific research in education, with a specific focus on evidence-based education (National Research Council 2005). The following search terms were used in each database: (engage* OR “on task” OR “off task” OR complian* OR noncomplian* OR behavior OR behaviors OR aggress* OR disrupt* OR problem* OR challeng* OR regulat* OR affect* OR social* OR emotion*) AND (intervene* OR treatment* OR therapy OR prevent*) AND (child* OR preschool*). Relevant reviews and meta-analyses (e.g., Barton et al. 2014; Carter et al. 2011; McCabe and Altamura 2011) were used to initiate literature trails. The search yielded 10,363 unique hits. We reduced the number of articles to 228 by reviewing the title and abstract and excluding studies that did not focus on models or practices delivered in early childhood classrooms. We obtained the full-text version of the 228 articles and determined that 49 articles met inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1). Studies included in the review are denoted with asterisks in the “References” section.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included, a study had to meet five criteria. First, the study had to include a model or practice designed to target one or more of the following child outcomes: teacher-child relationships, social skills (peers), social skills (adults), problem and/or challenging behavior, self-regulation, emotion identification, emotion expression, social problem solving, or engagement (i.e., task-oriented behavior). Second, the model or practice had to be delivered at a school or early childhood program. We did not include interventions tailored to an individual child that would not generalize across children (e.g., function-based interventions; LeGray et al. 2010). Third, the model or practice had to be evaluated using one of the following designs: (a) randomized controlled trial, (b) quasi-experimental group comparison design in which groups were matched or tested for differences, or (c) single-case experimental designs (e.g., ABAB/reversal, multiple baseline, changing criterion, and alternating-treatment designs). Fourth, at least one participant had to be preschool age (i.e., 3–5 years old). Finally, the study had to be published in English.

Coding of the Studies

We first focused on extracting individual practices from each study. We defined practice as a specific statement, behavior, or action of a teacher that manipulates features of the physical, temporal, interactional, or instructional environment in the classroom to promote child adaptation, behavioral competence, or learning. To extract practices, we sought to obtain the intervention manual if one existed. If the manual was not available, we relied on the most thorough description of the model provided in the published literature (e.g., description of the model). If such a source did not exist, we relied on the description provided in the article. In all, we relied upon 32 unique sources (n = 3 manuals and n = 29 articles) to code practices. Each intervention manual and article was double coded; disagreements were resolved via discussion.

Each practice was coded along the three dimensions: (a) Target goal, the domain of functioning targeted by the practice (i.e., teacher-child relationships, social skills (peers), social skills (adults), problem and/or challenging behavior, self-regulation, emotion identification, emotion expression, social problem solving, and/or engagement); (b) Unit, the components, features, or active ingredients that are a major part of a practice designed to promote child adaptation, behavioral competence, or learning. Units (e.g., emotional regulation training, social skills training) are typically composed of multiple practices. This dimension was only coded when appropriate (i.e., both the practice and the unit level were identified); and (c) Practice.

Translating Practices into Practice Elements

We took the extracted practices and grouped together the practices that were the same. We then combined the remaining practices to form practice elements via an iterative process. We defined practice elements as discrete practices, principles, or skills that comprise the models (see Chorpita and Daleiden 2009; Garland et al. 2008). Practices that targeted the same domain of child functioning via the same mechanism were grouped together to form single practice elements. For example, practices such as “behavior specific praise” and “descriptive praise” were grouped under the practice element “praise” (see Supplemental Table 1 in online material for how the praise, emotion regulation, and tangible reinforcement practice elements were created). Once the initial list of practice elements was produced, we grouped them into two categories (Garland et al. 2008): (a) Content, defined as the general principle that guides a practice; and (b) Delivery, defined as the way in which a teacher provides instruction to the child.

Expert Review

We surveyed five experts in early childhood education with experience developing or evaluating interventions for young children with social-emotional learning needs and problem behavior. Four experts received a PhD in education (75 % early childhood special education, 25 % special education) and one received a PhD in clinical/community psychology. All experts were employed in academic university settings (80 % Full Professor, 20 % Research Scientists). Two experts were co-authors of this paper and provided feedback after the practice elements were identified, defined, and extracted. None of the experts were authors of any of the models or practices included in the review. A survey was created by the first three authors, which included the name and definition of the 24 practice elements. Experts were asked to rate each practice element as to its relevance for use as a practice for addressing young children’s social-emotional learning needs and problem behavior in early childhood classrooms. Ratings included (a) “not necessary” to use in early childhood classrooms; (b) “useful”, but not essential to use in early childhood classrooms; or (c) “essential” to use in early childhood classrooms. The experts were asked to comment on each practice element and suggest additional practice elements missing from the list. For three practice elements, one respondent did not provide ratings. The criterion for retention of the elements was a useful or essential rating by at least 75 % of respondents.

Finalization of Practice Elements

The quantitative and qualitative feedbacks from the experts were reviewed, and consensus was reached on the final item list. This work included producing final definitions for each item.

Results

A total of 475 practices were extracted from the manuals (n = 3) and articles (n = 29). Redundant practices were grouped, which produced an initial list of 56 practices. These 56 practices were then transformed into practice elements via an iterative process (see Supplemental Table 2 in online material), which produced a list of 24 practice elements divided into content (emotion regulation, problem solving, promoting behavioral competence, promoting teacher-child relationship, social skills) and delivery (choices, differential reinforcement, error correction, ignoring, instructive feedback, modeling, monitoring, narrating, opportunities to respond, praise, precorrection, premack statements, rehearsal, rules, scaffolding, supportive listening, tangible reinforcement, time-out, visual cues) categories.

We submitted the 24 practice elements to the experts (see Table 1). Fourteen items were rated as essential to use in early childhood classrooms (choices, emotion regulation, error correction, ignoring, instructive feedback, modeling, opportunities to respond, praise, premack statements, problem solving, promoting behavioral competence, promoting teacher-child relationship, scaffolding, social skills). Three items were rated as essential by four of five experts and useful by one of five experts (differential reinforcement, monitoring, rehearsal). One item was rated as essential by three of five experts and useful by two of five experts (time-out). Two items were rated as essential by two of five experts and useful by three of five experts (narrating, tangible reinforcement). Four items were rated as essential by three of four experts and useful by one of four experts (precorrection, supportive listening, rules, visual cues). Given that the experts rated all of the items as useful or essential, we retained all of the practice elements. Three practice elements were modified, however, based upon expert feedback: promoting behavioral competence, precorrection, and rules.

Table 1 provides definitions and frequency counts of the 24 practice elements. To identify practice elements found in evidence-based models and practices, we searched the (a) What Works Clearinghouse (ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/), (b) Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development (www.blueprintsprograms.com/), and (c) CASEL (www.casel.org/preschool-and-elementary-edition-casel-guide). Social skills training was listed on What Works Clearinghouse; Incredible Years (Webster‐Stratton, C et al. 2008), PATHS (Domitrovich et al. 2007), and Tools of the Mind (Barnett et al. 2008) were labeled effective on CASEL; Head Start REDI (Bierman et al. 2008), and Incredible Years were listed as “promising” on Blueprints. Twenty of the 24 practice elements were included in Incredible Years, the only model listed on multiple lists (see Table 1). Lastly, we examined how delivery items grouped in the five content domains (see Supplemental Table 3 in the online materials).

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to describe the iterative process used to identify common practice elements of models and practices designed to target the social, emotional, and behavioral needs of young children who exhibit problem behavior. Utilizing a process described by Garland et al. (2008), we performed a comprehensive literature review, coded the identified literature, and consulted with experts. We identified a total of 24 practice elements that describe a range of practices used in early childhood classrooms to ameliorate problem behavior and improve social-emotional outcomes. The list of 24 practice elements represents an initial step in an effort to address some of the definitional issues in the field.

It is important to consider how our list compares with previous efforts to define practice elements in the mental health field as well as the implications such a list can have for efforts to implement these practices in early childhood settings. There is some overlap between our list of 24 practice elements and the lists produced by previous efforts to identify practice elements in psychosocial treatments for disruptive behavior problems (Chorpita et al. 2005; Chorpita and Daleiden 2009; Garland et al. 2008). Garland et al. (2008) identified a total of 21 practice elements and little less than half overlapped with our list (see Table 1). Of the 20 most frequent practice elements identified by Chorpita and Daleiden (2009) in psychosocial treatments for disruptive behavior problems, a little less than half of them overlapped with our list (see Table 1). So even though these efforts focused on mental health interventions, there is overlap in the practice elements identified by the three approaches. The overlap seen across these three independent efforts provides some preliminary validity to the overall approach of identifying practice elements.

As the previous efforts to identify practice elements focused on psychosocial treatments, it is not surprising (and perhaps encouraging) that we identified some unique practice elements. Unique practice elements identified in our study may reflect developmental differences (i.e., practice elements targeting outcomes of young children in our study versus older children in Garland et al. 2008 and Chorpita and Daleiden 2009) as well as contextual needs of stakeholders (i.e., teachers delivering practice elements in the classroom versus practitioners delivering interventions in clinical settings). Specific delivery items identified in our review that were not found in either of the previous efforts such as active supervision, precorrection, and rules may reflect the needs of teachers to promote and manage the behavior of young children who exhibit problem behavior within classroom contexts. Unique items such as opportunities to respond may reflect teachers’ attempts to provide learning opportunities to monitor child progress in the classroom as well as to promote child engagement in individual and group learning formats.

Our ability to identify practice elements has research and practical implications. This list could help inform efforts to develop quality indicators (i.e., a measure of the quality of early childhood classrooms) for the delivery of practices targeting social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes in early childhood classrooms. In mental health, some efforts to improve care have focused on identifying quality indicators embedded in a quality of care framework (McGlynn et al. 1988). Quality of care research seeks to improve the outcomes of individuals by studying how structural elements (e.g., contextual elements including attributes of settings, clients, and providers) and processes of care (e.g., activities and behaviors associated with giving and receiving care) influence outcomes. In this framework, identifying quality indicators is an important prerequisite for engaging in quality improvement (Garland et al. 2010; Pincus et al. 2011). This is because quality indicators provide the means to assess, track, and monitor the performance of providers relative to recommended practice in the field (Hussey et al. 2007).

Of course, an important step in identifying quality indicators is determining the practice elements linked to key outcomes, a point that highlights a limitation of our review. Unlike previous efforts to identify practice elements (e.g., Chorpita and Daleiden 2009; Garland et al. 2008), we did not take strength or level of evidence into account when identifying models or discrete practices as part of the literature review. We opted to take this approach because it allowed us to use a larger dataset to begin developing a set of practice elements in the field of early education. That said, 20 of the 24 practice elements were found in an evidence-based model, suggesting that most practice elements have empirical support. An important future direction will be to accumulate more evidence regarding the empirical support for the individual practice elements. In the long term, it will be important to winnow the set of practice elements using level of evidence. However, doing so will require producing effect size estimates across single case experimental designs, quasi-experimental designs, and experimental group designs, which represent a challenge for the field (see Shadish et al. 2015). It will be important to negotiate this hurdle so that work toward synthesizing the literature across the various research designs can be made, which will aid in the process of identifying quality indicators with clear empirical support.

Turning to applications of the practice elements we identified, it may be possible to train teachers to use them as a part of efforts to improve the process quality in classroom settings. We identified 24 practice elements suggesting that there may be a relatively short list of practices in the early childhood literature that pertain to young children’s problem behaviors and social-emotional learning. Most models and practices evidenced substantial overlap, suggesting that training teachers to use a relatively short number of practice elements would cover most of the content found in existing models. Moreover, most delivery items clustered within a few content domains, suggesting that it may be possible to select particular practice elements based on the area of child need being targeted. This helps to illustrate why some have suggested that adopting a practice element framework for implementation efforts can be more cost effective and scalable than relying on purveyor-driven models (e.g., Chorpita and Daleiden 2009).

Our results could also inform the development of treatment integrity tools capable of supporting implementation efforts. Some have suggested that treatment integrity instruments used in implementation research should focus on three components (Bellg et al. 2004; McLeod et al. 2013): treatment adherence (prescribed interventions), treatment differentiation (proscribed interventions), and competence (quality of prescribed interventions). These treatment integrity components encompass the core components involved in the implementation of practice elements as each plays a critical role in fostering positive outcomes in young children (Durlak 2010). However, to our knowledge, there are no treatment integrity instruments in the early childhood education field that assess all three components and have utility for use within an implementation science framework (Sutherland et al. 2013). Most existing instruments are designed to assess treatment adherence; however, in implementation research, it is important to assess multiple treatment integrity components (McLeod et al. 2013; Sutherland et al. 2013). The 24 practice elements identified herein could form the items of an integrity instrument capable of assessing treatment adherence and differentiation as well as allow researchers to characterize the instructional practices delivered in business-as-usual classrooms. Thus, it is possible to use these practice elements as items for an integrity instrument for early childhood classrooms.

Though our approach to identifying practice elements had a number of strengths, a few limitations should be recognized. First, a small number of experts were used to help establish the content validity of the practice elements, and it is possible that a larger number of experts may have suggested the addition of more items. Second, it is possible that there may be some practice elements included in the models that were not written in the manuals or articles. It could be the case that the description of the practices was mostly limited to those that represented the main focus of study and that some practices were not explicitly described.

In summary, by using a practice element framework we were able to identify 24 common practice elements that appear in comprehensive intervention models or that are discrete practices targeting social, emotional, and behavioral needs of young children who exhibit problem behavior. On the one hand, this process has implications for improving educational services to these children through training and implementation efforts. On the other hand, the practice elements framework may be useful for researchers, policy makers, and practitioners as we search for efficient and effective ways to serve children and youth who are most vulnerable.

References

*Baker-Henningham, H., Scott, S., Jones, K., & Walker, S. (2012). Reducing child conduct problems and promoting social skills in a middle-income country: Cluster randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 201, 101-108.

Barbarin, O. A. (2007). Mental health screening of preschool children: Validity and reliability of ABLE. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77, 402–418.

*Barnett, W. S., Jung, K., Yarosz, D. J., Thomas, J., Hornbeck, A., Stechuk, R., & Burns, S. (2008). Educational effects of the Tools of the Mind curriculum: A randomized trial. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(3), 299-313.

Barton, E. E., Steed, E. A., Strain, P., Dunlap, G., Powell, D., & Payne, C. J. (2014). An analysis of classroom-based and parent-focused social–emotional programs for young children. Infants & Young Children, 27, 3–29.

*Beaulieu, L., Hanley, G. P., & Roberson, A. A. (2012). Effects of responding to a name and group call on preschoolers’ compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(4), 685-707.

Bellg, A. J., Borrelli, B., Resnick, B., Hecht, J., Minicucci, D. S., Ory, M., & Czajkowski, S. (2004). Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Health Psychology, 23, 443–451.

*Bellone, K. M., Dufrene, B. A., Tingstrom, D. H., Olmi, D. J., & Barry, C. (2014). Relative efficacy of behavioral interventions in preschool children attending Head Start. Journal of Behavioral Education, 23(3), 378-400.

Beutler, L. E., & Baker, M. (1998). The movement toward empirical validation: At what level should we analyze, and who are the consumers? In K. S. Dobson & K. D. Craig (Eds.), Empirically supported therapies (pp. 43–65). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Press.

*Bierman, K. L., Domitrovich, C. E., Nix, R. L., Gest, S. D., Welsh, J. A., Greenberg, M. T.,…Gill, S. (2008). Promoting academic and social‐emotional school readiness: The Head Start REDI program. Child Development, 79(6), 1802-1817.

*Brown, J. A., Jimerson, S. R., Dowdy, E., Gonzalez, V., & Stewart, K. (2012). Assessing the effects of school‐wide second step implementation in a predominately English language learner, low SES, Latino sample. Psychology in the Schools, 49(9), 864-875.

*Carpenter, E. M., & Nangle, D. W. (2002). Effects of brief verbal instructions on aggression: A replication in a Head Start setting. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 24(4), 21-38.

Carter, E. W., Lane, K. L., Crnobori, M., Bruhn, A. L., & Oakes, W. P. (2011). Self-determination interventions for students with and at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders: Mapping the knowledge base. Behavioral Disorders, 36, 100–116.

Chorpita, B. F., & Daleiden, E. L. (2009). Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 566–579.

Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2005). Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research, 7, 5–20.

*Conner, N. W., & Fraser, M. W. (2011). Preschool social–emotional skills training: A controlled pilot test of the Making Choices and Strong Families programs. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(6), 699-711.

*Domitrovich, C. E., Cortes, R. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (2007). Improving young children’s social and emotional competence: A randomized trial of the preschool “PATHS” curriculum. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 28(2), 67-91.

*Driscoll, K. C., & Pianta, R. C. (2010). Banking Time in Head Start: Early efficacy of an intervention designed to promote supportive teacher–child relationships. Early Education and Development, 21(1), 38-64.

*Drogan, R. R., & Kern, L. (2014). Examination of the mechanisms underlying effectiveness of the turtle technique. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 33(4), 237-248.

Durlak, J. A. (2010). The importance of doing well in whatever you do: A commentary on the special section, “Implementation research in early childhood education.”. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 348–357.

Embry, D. D., & Biglan, A. (2008). Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11, 75–113.

Fairburn, C. G., & Patel, V. (2014). The global dissemination of psychological treatments: A road map for research and practice. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 495–498.

Feil, E. G., Small, J. W., Forness, S. R., Serna, L. A., Kaiser, A. P., Hancock, T. B., & Burchinal, M. R. (2005). Using different measures, informants, and clinical cut-off points to estimate prevalence of emotional or behavioral disorders in preschoolers: Effects on age, gender, and ethnicity. Behavioral Disorders, 30, 375–391.

*Filcheck, H. A., McNeil, C. B., Greco, L. A., & Bernard, R. S. (2004). Using a whole-class token economy and coaching of teacher skills in a preschool classroom to manage disruptive behavior. Psychology in the Schools, 41(3), 351-361.

*Fullerton, E. K., Conroy, M. A., & Correa, V. I. (2009). Early childhood teachers’ use of specific praise statements with young children at risk for behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 34(3), 118-125.

Garland, A. F., Hawley, K. M., Brookman-Frazee, L., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2008). Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children’s disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 505–514.

Garland, A. F., Bickman, L., & Chorpita, B. F. (2010). Change what? Identifying quality improvement targets by investigating usual mental health care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37, 15–26.

*Gettinger, M., & Stoiber, K. C. (2014). Increasing opportunities to respond to print during storybook reading: Effects of evocative print-referencing techniques. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(3), 283-297.

*Hamre, B. K., Pianta, R. C., Mashburn, A. J., & Downer, J. T. (2012). Promoting young children’s social competence through the preschool PATHS curriculum and MyTeachingPartner professional development resources. Early Education & Development, 23(6), 809-832.

*Han, S. S., Catron, T., Weiss, B., & Marciel, K. K. (2005). A teacher-consultation approach to social skills training for pre-kindergarten children: Treatment model and short-term outcome effects. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(6), 681-693.

*Helker, W. P., & Ray, D. C. (2009). Impact of child teacher relationship training on teachers’ and aides’ use of relationship-building skills and the effects on student classroom behavior. International Journal of Play Therapy, 18(2), 70-83.

Hemmeter, M., Corso, R., & Cheatham, G. (2006). A national survey of early childhood educators: Training needs and strategies (Paper presented at the Conference on Research Innovations in Early Intervention, San Diego, CA).

*Herman, K. C., Borden, L. A., Reinke, W. M., & Webster-Stratton, C. (2011). The impact of the Incredible Years parent, child, and teacher training programs on children’s co-occurring internalizing symptoms. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(3), 189-201.

Hussey, P. S., Mattke, S., Morse, L., & Ridgely, M. (2007). Evaluation of the use of AHRQ and other quality indicators (Vol. Prepared for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). Rockville, MD: RAND Health.

*Hutchings, J., Martin-Forbes, P., Daley, D., & Williams, M. E. (2013). A randomized controlled trial of the impact of a teacher classroom management program on the classroom behavior of children with and without behavior problems. Journal of School Psychology, 51(5), 571-585.

Institute of Medicine. (2015). Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: A framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Retrieved from: http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2015/Psychosocial-Interventions-Mental-Substance-Abuse-Disorders.aspx.

*Izard, C. E., King, K. A., Trentacosta, C. J., Morgan, J. K., Laurenceau, J., Krauthamer-Ewing, E. S., & Finlon, K. J. (2008). Accelerating the development of emotion competence in head start children: Effects on adaptive and maladaptive behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 20(1), 369-397.

*Izard, C. E., Trentacosta, C. J., King, K. A., & Mostow, A. J. (2004). An emotion-based prevention program for head start children. Early Education & Development, 15(4), 407-422.

*Koglin, U., & Petermann, F. (2011). The effectiveness of the behavioural training for preschool children. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 19(1), 97-111.

*Larmar, S., Dadds, M. R., & Shochet, I. (2006). Successes and challenges in preventing conduct problems in Australian preschool-aged children through the Early Impact program. Behaviour Change, 23(2), 121-137.

*LeBel, T. J., Chafouleas, S. M., Britner, P. A., & Simonsen, B. (2013). Use of a daily report card in an intervention package involving home-school communication to reduce disruptive behavior in preschoolers. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 15(2), 103-112.

LeGray, M. W., Dufrene, B. A., Sterling-Turner, H., Olmi, D. J., & Bellone, K. (2010). A comparison of function-based differential reinforcement interventions for children engaging in disruptive classroom behavior. Journal of Behavioral Education, 19, 185–204.

*Levine, D. G., & Ducharme, J. M. (2013). The effects of a teacher–child play intervention on classroom compliance in young children in child care settings. Journal of Behavioral Education, 22(1), 50-65.

*Ling, S. M., & Barnett, D. W. (2013). Increasing preschool student engagement during group learning activities using a group contingency. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 33(3), 186-196.

*Luczynski, K. C., & Hanley, G. P. (2013). Prevention of problem behavior by teaching functional communication and self‐control skills to preschoolers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46(2), 355-368.

*Luczynski, K. C., Hanley, G. P., & Rodriguez, N. M. (2014). An evaluation of the generalization and maintenance of functional communication and self‐control skills with preschoolers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(2), 246-263.

McCabe, P. C., & Altamura, M. (2011). Empirically valid strategies to improve social and emotional competence of preschool children. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 513–540.

McGlynn, E. A., Norquist, G. S., Wells, K. B., Sullivan, G., & Liberman, R. P. (1988). Quality-of-care research in mental health: Responding to the challenge. Inquiry, 25, 157–170.

McLeod, B. D., Southam‐Gerow, M. A., Tully, C. B., Rodríguez, A., & Smith, M. M. (2013). Making a case for treatment integrity as a psychosocial treatment quality indicator for youth mental health care. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20, 14–32.

*Morris, P., Millenky, M., Raver, C. C., & Jones, S. M. (2013). Does a preschool social and emotional learning intervention pay off for classroom instruction and children’s behavior and academic skills? Evidence from the Foundations of Learning project. Early Education & Development, 24(7), 1020-1042.

*Morrison, M. O., & Bratton, S. C. (2010). Preliminary investigation of an early mental health intervention for Head Start programs: Effects of child teacher relationship training on children’s behavior problems. Psychology in the Schools, 47(10), 1003-1017.

*Murphy, K. A., Theodore, L. A., Aloiso, D., Alric‐Edwards, J. M., & Hughes, T. L. (2007). Interdependent group contingency and mystery motivators to reduce preschool disruptive behavior. Psychology in the Schools, 44(1), 53-63. 205.

National Research Council. (2005). Advancing scientific research in education. In L. Towne, L. L. Wise, & T. M. Winters (Eds.), Committee on Research in Education (Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

*Nix, R. L., Bierman, K. L., Domitrovich, C. E., & Gill, S. (2013). Promoting children’s social-emotional skills in preschool can enhance academic and behavioral functioning in kindergarten: Findings from Head Start REDI. Early Education & Development, 24(7), 1000-1019.

O’Conner, E. E., Dearing, E., & Collins, B. A. (2011). Teacher-child relationship and behavior problem trajectories in elementary school. American Educational Research Journal, 48, 120–162.

*Ostrov, J. M., Massetti, G. M., Stauffacher, K., Godleski, S. A., Hart, K. C., Karch, K. M.,…Ries, E. E. (2009). An intervention for relational and physical aggression in early childhood: A preliminary study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24(1), 15-28.

*Pahl, K. M., & Barrett, P. M. (2010). Preventing anxiety and promoting social and emotional strength in preschool children: A universal evaluation of the fun FRIENDS program. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 3(3), 14-25.

*Petermann, F., & Natzke, H. (2008). Preliminary results of a comprehensive approach to prevent antisocial behaviour in preschool and primary school pupils in Luxembourg. School Psychology International, 29(5), 606-626.

Pincus, H. A., Spaeth-Rublee, B., & Watkins, K. E. (2011). Analysis & commentary: The case for measuring quality in mental health and substance abuse care. Health Affairs, 30, 730–736.

Powell, D., & Dunlap, G. (2009). Evidence-based social-emotional curricula and intervention packages for children 0–5 years and their families (roadmap to effective intervention practices). Tampa, Florida: University of South Florida.

*Ramaswamy, V., & Bergin, C. (2009). Do reinforcement and induction increase prosocial behavior? Results of a teacher-based intervention in preschools. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 23(4), 527-538.

*Raver, C. C., Jones, S. M., Li-Grining, C., Zhai, F., Metzger, M. W., & Solomon, B. (2009). Targeting children’s behavior problems in preschool classrooms: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(2), 302-316.

*Reinke, W. M., Stormont, M., Herman, K. C., Wang, Z., Newcomer, L., & King, K. (2014). Use of coaching and behavior support planning for students with disruptive behavior within a universal classroom management program. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 22(2), 74-82.

Shadish, W. R., Hedges, L. V., Horner, R. H., & Odom, S. L. (2015). The role of between-case effect size in conducting, interpreting, and summarizing single-case research. Retrieved from: http://ies.ed.gov/ncser/pubs/2015002/pdf/2015002.pdf.

*Shernoff, E. S., & Kratochwill, T. R. (2007). Transporting an evidence-based classroom management program for preschoolers with disruptive behavior problems to a school: An analysis of implementation, outcomes, and contextual variables. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(3), 449-472.

*Smith, C. S., Lewis, T. J., Stormont, M. (2010). The effectiveness of two universal behavioral supports for children with externalizing behavior in Head Start classrooms. Journal of Positive Behavior, 13(3), 133-143.

*Stefan, C. A. (2008). Short-term efficacy of a primary prevention program for the development of social-emotional competencies in preschool children. Cognition, Brain, Behavior, 12(2), 285-307.

*Ştefan, C. A. (2012). Social emotional prevention program for preschool children: An analysis of the high risk sample. Cognition, Brain, Behavior, 16(3), 319-356.

*Ştefan, C. A., & Miclea, M. (2013). Effects of a multifocused prevention program on preschool children’s competencies and behavior problems. Psychology in the Schools, 50(4), 382-402.

*Ştefan, C. A., & Miclea, M. (2012). Classroom effects of a hybrid universal and indicated prevention program for preschool children: A comparative analysis based on social and emotional competence screening. Early Education & Development, 23(3), 393-426.

Sutherland, K. S., McLeod, B. D., Conroy, M. A., & Cox, J. R. (2013). Measuring implementation of evidence-based programs targeting young children at risk for emotional/behavioral disorders: Conceptual issues and recommendations. Journal of Early Intervention, 35, 129–149.

*Tiano, J. D., & McNeil, C. B. (2006). Training head start teachers in behavior management using parent-child interaction therapy: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, 3(2), 220-233.

*Tominey, S. L., & McClelland, M. M. (2011). Red light, purple light: Findings from a randomized trial using circle time games to improve behavioral self-regulation in preschool. Early Education & Development, 22(3), 489-519.

*Upshur, C., Wenz-Gross, M., & Reed, G. (2013). A pilot study of a primary prevention curriculum to address preschool behavior problems. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 34(5), 309-327.

*Webster‐Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Stoolmiller, M. (2008). Preventing conduct problems and improving school readiness: Evaluation of the Incredible Years teacher and child training programs in high‐risk schools. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(5), 471-488.

*Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Hammond, M. (2004). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: Intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(1), 105-124.

Wolery, M., & Hemmeter, M. L. (2011). Classroom instruction background, assumptions, and challenges. Journal of Early Intervention, 33, 371–380.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Preparation of this article was supported in part by a grant from the Institute of Education Science (R305A140487; McLeod and Sutherland).

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOC 126 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McLeod, B.D., Sutherland, K.S., Martinez, R.G. et al. Identifying Common Practice Elements to Improve Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Outcomes of Young Children in Early Childhood Classrooms. Prev Sci 18, 204–213 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0703-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0703-y