Abstract

Minority children living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are at high risk for school dropout, delinquency, and poor health, largely due to the negative impact of poverty and stress on parenting and child development. This study evaluated a population-level, family-centered, school-based intervention designed to promote learning, behavior, and health by strengthening parenting, classroom quality, and child self-regulation during early childhood. Ten schools in urban districts serving primarily low-income Black students were randomly assigned to intervention or a “pre-kindergarten education as usual” control condition. Intervention included a family program (a 13-week behavioral parenting intervention and concurrent group for children) and professional development for early childhood teachers. The majority (88 %) of the pre-kindergarten population (N = 1,050; age 4) enrolled in the trial, and nearly 60 % of parents in intervention schools participated in the family program. This study evaluated intervention impact on parenting (knowledge, positive behavior support, behavior management, involvement in early learning) and child conduct problems over a 2-year period (end of kindergarten). Intent-to-treat analyses found intervention effects on parenting knowledge, positive behavior support, and teacher-rated parent involvement. For the highest-risk families, intervention also resulted in increased parent-rated involvement in early learning and decreased harsh and inconsistent behavior management. Among boys at high risk for problems based on baseline behavioral dysregulation (age 4, 23 % of sample), intervention led to lower rates of conduct problems at age 6. Family-centered intervention at the transition to school has potential to improve population health and break the cycle of disadvantage for low-income, minority families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A robust literature documents the impact of socioeconomic adversity on child development, implicating poverty as a key factor underlying racial/ethnic disparities in learning, behavior, and health (e.g., Blair and Raver 2012). In the USA, 80 % of the population lives in urban areas, and minority children are 6 to 9 times more likely than White children to live in concentrated poverty. The density and diversity of risks in urban areas pose major challenges and opportunities for strategic investments to improve population health (Stine et al. 2013).

Preventive interventions early in life have the potential to attenuate risk attributable to poverty and stress (Olds et al. 1998), and there is evidence of efficacy with low-income, ethnically diverse parents of preschoolers (Reid et al. 2001; Zubrick et al. 2005). However, poverty is typically associated with smaller intervention impact (Lundahl et al. 2006), and the vast majority of families raising young children in low-income, urban neighborhoods do not have access to evidence-based parenting interventions. To reduce racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in the USA, interventions must be broadly available, engaging, and effective for low-income, minority families living in large urban centers.

Toward this goal, ParentCorps was designed as a universal intervention for children in pre-kindergarten (pre-k) programs in schools in low-income neighborhoods. The school-based delivery model and intervention content and process were developed to be relevant and engaging for all families as children enter school, with recognition of the full breadth of diversity found in urban areas (e.g., immigrant status, cultural identity). To effectively mitigate the impact of poverty on children’s learning, behavior, and health, ParentCorps includes components for parents, teachers, and children that combine to strengthen parenting, classroom quality, and child self-regulation. This paper focuses on our approach to engaging and supporting families.

Embedding parenting intervention in schools as part of early childhood education minimizes logistical barriers to participation, creates a mechanism to reach the majority of children, and has the potential to create a sustainable network (corps) to support effective parenting. There is substantial evidence that key developmental transitions are an optimal time for prevention, in part because of parent openness and motivation to change (e.g., Shaw et al. 2006). Framing parenting interventions as support for school success is likely to increase acceptability and capitalize on the motivation shared by parents from diverse cultures to help children achieve.

Numerous trials show that universal intervention (for all children in at-risk populations) can improve outcomes for all, with the greatest benefits for those at highest risk (e.g., Reid et al. 2004). Altering trajectories among high-risk children early in life has been shown to yield a broad range of long-term benefits (e.g., Olds et al. 1998). Universal programs that engage the highest-risk families are expected to result in cascading effects in this subgroup, and in combination with modest changes for all children experiencing adversity, may well reduce disparities in learning, behavior, and health of the population.

FormalPara Poverty, Parenting, and Child Behavioral DysregulationPositive parenting in early childhood is a key contributor to lifelong health and productivity (Shonkoff et al. 2012). Yet, poverty constrains parenting resources and jeopardizes successful development of self-regulation (e.g., executive functioning, effortful control; Blair and Raver 2012). Transactional social learning models predict that behavioral dysregulation and disrupted parenting set in motion a cascade toward conduct problems and school failure (e.g., Shaw et al. 2000). Specific aspects of parenting are strongly linked to child development, including support for positive behavior, behavior management, and involvement in education (e.g., Hill and Craft 2003; Patterson and Stouthamer-Loeber 1984). Experimental prevention trials strengthen the developmental literature with compelling evidence in support of the causal role of parenting for conduct and related problems (for review, see Sandler et al. 2011).

“Early-starter” models of conduct problems implicate behavioral dysregulation (e.g., non-compliance) in precipitating coercive parent–child interactions, characterized by harsh and inconsistent behavior management and inadvertent reinforcement of misbehavior (e.g., Shaw et al. 2000). Children who enter school with dysregulated behavior are at risk for serious conduct problems (e.g., aggression, stealing); over time, as it becomes increasingly difficult for parents to remain involved and supportive, parental withdrawal sets the stage for deviant peer associations, antisocial behavior, and school failure (e.g., Cox et al. 2010).

FormalPara Culturally Informed ApproachA robust literature documents the efficacy of parenting interventions for early conduct problems (Lundahl et al. 2006). Yet, population-level efforts to successfully engage and support diverse families require a nuanced understanding of parenting that considers culture and context (e.g., Baumrind et al. 2002). Although many studies show that harsh behavior management predicts poorer outcomes (e.g., Pardini et al. 2008; MacKenzie et al. 2012), this may depend on cultural normativeness (Lansford et al. 2005) and context (e.g., neighborhood safety; Knight et al. 1994). In some contexts, physical discipline may be associated with lower levels of problems for minority children (e.g., Lansford et al. 2004). Thus, a prescriptive approach for or against certain parenting practices is not justified and may be perceived by parents as irrelevant or culturally naïve; this disconnect may contribute to underutilization of services by ethnic minority communities (for review, see Ortiz and Del Vecchio 2013).

ParentCorps was designed to serve culturally diverse communities; it is not an adaptation for a particular group. Cultural informants, including Black and Latino US-born and immigrant parents, educators, and mental health professionals provided extensive input on content and process (Brotman et al. 2008, 2011). The approach to behavior change is collaborative, autonomy supporting, and non-prescriptive. ParentCorps gives parents access to the latest evidence on parenting (along with limitations of extant research) so they may consider adopting strategies that are consistent with their cultural values and feasible given everyday realities. ParentCorps creates opportunities to reflect on the influence of culture and context on parenting and child development and recognizes the broad spectrum of family strengths (e.g., traditional values, strong commitment to children’s success) as well as stressors related to urban disadvantage (e.g., discrimination, community violence). Therefore, although ParentCorps includes a core set of behavioral strategies (e.g., positive reinforcement, consequences) that are found in nearly all effective parenting interventions (e.g., Incredible Years Series, Triple P), its culturally informed approach is unique (see examples in “Method”). Other defining features of the intervention include its emphasis on goal setting across social-emotional, cognitive, and behavioral domains; consideration of parents’ readiness for change; and a school-based delivery model which fosters sustainable connections among parents. In this model, school personnel (mental health professionals and teachers) are facilitators of the parenting intervention and concurrent group for children to increase opportunities for relationship building and foster a shared commitment to children’s success. Intervention aims to strengthen the following three key domains of parenting: positive behavior support (e.g., reinforcement, proactive strategies), behavior management (e.g., consistent consequences), and parent involvement in early learning (e.g., reading to children, communicating with teachers).

FormalPara ParentCorps ImpactA randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the family program (13-week parenting intervention and group for children) delivered in schools with pre-k programs with a diverse urban sample (e.g., 39 % Black, 24 % Latino; >50 % immigrant parents), demonstrated feasibility and impact on parenting and child behavior in pre-k (Brotman et al. 2011); although school personnel were facilitators (Brotman et al. 2008), impact on learning was limited. A second larger RCT tested an enhanced version of ParentCorps which included a new component for pre-k and kindergarten teachers to promote communication with parents and behavioral strategies to improve classroom quality. The enhanced program had a positive impact on kindergarten achievement test scores and trajectories of academic performance (e.g., for reading achievement, Cohen’s d = 0.34; Brotman et al. 2013).

Within the second RCT, the current study evaluates intervention impact on the three targeted domains of parenting and the prevention of conduct problems through the end of kindergarten. We examine baseline behavioral dysregulation and parenting as moderators of impact on parenting and child sex and dysregulation as moderators of impact on conduct problems. Given the ultimate goal of population-level impact, we examined predictors of participation in the family program.

Method

Study Design and Context

The RCT was conducted in two school districts in highly disadvantaged urban neighborhoods in New York City (NYC). Schools were eligible for the trial if they had a pre-k program and a student population greater than 80 % Black and 70 % low income; 10 schools were randomly assigned to intervention and control conditions. Baseline equivalence has been established with respect to neighborhood, school, classroom, family, and child factors, including independent observations of classrooms and children (Brotman et al. 2013; see Table 1 for measures in the current study).

Participants

The RCT aimed to enroll all pre-k students in four consecutive years (2005–2008). The only eligibility criterion was that one parent was proficient in English; 7 % were deemed ineligible (Fig. 1). The study was introduced at the school’s pre-k orientation, using a phased consent procedure to secure a sample that was representative and equivalent by condition. Phase 1 included school-based assessments (e.g., teacher ratings, testing) and no time demands for parents; phase 2 involved three family assessments by phone. In phase 1, 88 % of the pre-k student population enrolled, resulting in a total sample of 1,050 children (from 99 pre-k classrooms). Of parents enrolled in phase 1, 79 % (N = 831) consented to phase 2 and completed at least one phone interview. Enrollment rates were comparable by condition, and there were no differences in the demographic characteristics of families who did and did not consent to phase 2 (p > 0.10). Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of New York University School of Medicine and the NYC Department of Education (DOE).

Study children were 4.15 years old (SD = 0.28) at pre-k entry (see Table 1). Most parents/caregivers were mothers (88 %, mean age 33.9 years); 68 % were immigrants; 85 % were non-Latino Black (AfroCaribbean, African American). The variability in SES is noteworthy (e.g., 14 % no high school diploma/GED; 17 % college graduates). Families lived in 159 census tracts, which were primarily Black (78 %), immigrant (41 %), and poor (38 %).

Intervention Conditions

ParentCorps

Schools assigned to the intervention received the following: (1) a family program for pre-k students co-led by mental health professionals and teachers (as in the previous trial; Brotman et al. 2011); and (2) professional development for pre-k and kindergarten teachers. Intervention aimed to increase parent involvement in early learning, positive behavior support, and effective behavior management in the home and classroom (through parallel behavioral strategies). Professional development for teachers included large group-based activities to introduce strategies (5 days in year 1; 2 days/year in years 2–4) and consultation to facilitate adoption and tailoring of strategies (∼6 h/year). Pre-k teachers who chose to co-lead the family program (80 %) received additional training (2 days/year), coaching (1 h/week for 13 weeks), and compensation for after-hours work (4 h/week for 13 weeks).

The family program included 13 weekly 2-h sessions for parents (Parent Group; ∼15 members/group) and concurrent sessions for children (Child Group), held at school, typically from 5 to 7 pm. Families of all pre-k students in the school were invited to participate in a program for families to “help children succeed.” The entire family was welcome, including caregivers residing outside the home; childcare and a creative arts group were provided for toddlers and older siblings, respectively. Dinner was served, and gift cards were raffled as incentives for participation. Parents learned about the program through flyers and brief informational sessions at school events (with parent “graduates” from prior years). Teachers engaged parents in person and by phone. Welcoming invitations continued throughout (e.g., “Come when you can, even if it means coming late,” “Bring me to ParentCorps” stickers on children’s coats), and the initial Parent Group session was designed to identify barriers and elicit parents’ commitment to attending as consistently as possible. Weekly reminder calls and “We missed you” flyers were also used.

During Parent Group, mental health professionals followed detailed session manuals to present a specific set of strategies: daily routines; positive parent–child interactions during non-directive play; sharing books; positive reinforcement; proactive strategies; selectively ignoring mild misbehavior; consequences for serious misbehavior; helping children manage emotions; and parent self-care. Program content and process were designed to encourage participation, reflection, and consideration of culture and context and to motivate parents to try new strategies. Initial sessions included activities in which parents were invited to share about their culture and discuss how culture influences parenting and child development (e.g., benefits of strong ethnic identity). In this context, parents set goals for their children and shared them with Parent Group members, Child Group leaders, and other important caregivers. Sessions followed a consistent structure and approach to behavior change, including introduction of topics through a ParentCorps video (illustrating A Day in the Life of three families living in one urban community), evocative questions about the influence of culture (e.g., What might your grandmother say about praising children for good behavior? What are some reasons that a parent might choose to spank? Or not to spank?), experiential activities (e.g., role plays), discussion about parents’ readiness to try a new skill (e.g., inviting dissent or expressions of doubt), and group problem solving to address potential barriers to change. Facilitators used a collaborative, autonomy-supporting approach that was intended to empower parents to select the strategies that were most relevant to their goals and consistent with their values. For example, rather than taking a prescriptive stance against spanking, leaders facilitated exploration of parents’ goals for discipline (e.g., “to teach good behavior,” “to stop misbehavior,” “to teach respect for elders”) and the congruence between the strategies and their values (e.g., a parent may continue to spank in certain situations to keep her child safe; another parent may try alternatives because spanking in anger is incongruent with her value for feeling in control).

In the Child Group, following detailed session manuals, leaders used a consistent structure (e.g., lesson with puppets, play), positive behavior support, and behavior management to promote social–emotional skills (e.g., sharing, paying attention, identifying feelings). These skills are considered foundational for self-regulation and early learning (Raver et al. 2007); many are common to effective social–emotional and behavioral interventions for young children (e.g., Incredible Years Dinosaur School; Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies). Additional lessons celebrate diversity and support emerging identity.

The parent and child components were intentionally integrated in numerous ways. At the end of each of the 13 2-h sessions, Child Group leaders provided positive feedback to parents about children’s progress toward individualized goals, grounded in observations of the child’s strengths and challenges. Periodic parent–child activities facilitated by Parent and Child Group leaders provided an opportunity for positive interactions and practicing of new skills. Exposure to strategies taught to their parents (e.g., sticker charts, Time Out) increased children’s familiarity with and acceptance of these practices when implemented at home by their parents.

Fidelity was assessed in terms of adherence and facilitator competence. Multiple facilitators rated adherence to weekly protocols of key content and process elements (Parent Group, 5–18 elements per session; Child Group, 10–12 elements per session); based on more than 300 sessions, adherence was 96 % (ranging from 86 to 99 %, ICC = 0.75) for Parent Group and 95 % (ranging from 92 to 98 %, ICC = 0.73) for Child Group. Facilitator competence, measured by weekly ratings from parents (e.g., “Leader made me and other group members feel comfortable and confident”), was high (M = 1.3 on a scale from 1 “strongly agree” to 7 “strongly disagree”) and consistent across schools and years (all M < 2.0).

Control Condition

All schools provided full-day (6.3 h) or half-day (2.5 h) pre-k and full-day kindergarten. During the study period, there were ∼560 NYC public schools with full- or half-day pre-k serving ∼23,000 4-year-olds (and another 500 pre-k programs in community organizations); approximately 60 % of 4-year-olds in NYC were enrolled in pre-k. Pre-k curriculum was aligned with state early learning standards (including social–emotional skills). Based on information collected from the DOE, key elements of ParentCorps were not provided in control schools. For example, monthly parent workshops focused on topics other than parenting (e.g., nutrition, asthma), and teachers did not receive training on family engagement. Parent–teacher communication was typically limited to three brief (5–10 min) events throughout the school year (orientation, fall and spring parent–teacher conferences).

Measures

Pre-k and kindergarten teachers completed questionnaires at the beginning and end of the school year (4 times). Parents were interviewed at the beginning and end of pre-k and at the end of kindergarten (3 times; except that parent ratings of involvement were obtained 2 times, in pre-k only). The current study includes teacher ratings of parent involvement (N = 1,003; phase 1 consent) and parent ratings of parenting and conduct problems (N = 831; phase 2 consent). Demographics were obtained via parent report and census tract data (N = 1,050). All measures have been used successfully in previous trials with ethnically diverse parents of young children.

Parenting

Parenting was assessed by multiple methods across three domains, namely positive behavior support, behavior management, and involvement in early learning. Measures in all domains have been used in previous studies of ParentCorps and have been shown to be sensitive to intervention-induced changes in parents of young children (e.g., Brotman et al. 2011; Webster-Stratton et al. 2001, 2004).

Knowledge of positive behavior support and effective behavior management was measured with the effective practices test (EPT; Brotman et al. 2011). Parents were asked to select the best response to 10 vignettes about young children’s behavior. Stability (over 6 months within the control condition) was 0.46, and in a previous trial of ParentCorps, a linear dose–response relation was established (Est = 0.71, SE = 0.17, p < 0.001; Brotman et al. 2011).

Positive behavior support was measured with the Parenting Practices Interview (PPI; Webster-Stratton 1998); positive reinforcement subscale (15 items; e.g., “How often do you praise or compliment your child?” rated from (1) “Never” to (5) “Very Often”) and the clear expectations subscale (3 items; e.g., “I have made clear rules for my child about chores” rated from (1) “Strongly Disagree” to (5) “Strongly Agree”). The two subscales were correlated (r = .36, p < .001) and combined to create a composite; internal consistency (α) of the 18-item composite was moderate (ranging from 0.66 to 0.71 over time), and stability was .64.

Harsh and inconsistent behavior management was measured with two subscales of the PPI: harsh (6 items; e.g., “How often do you raise your voice or yell at your child”; rated from (1) “Never” to (5) “Very often”) and inconsistent discipline (6 items; e.g., “If you warn your child that you will punish him if he doesn’t stop misbehaving, how often do you actually punish him if he keeps on misbehaving?”; rated from (1) “Never” to (5) “Very Often”). The subscales were correlated (r = 0.33, p < 0.001) and combined (α = 0.66–0.72; stability = 0.60).

Parent report of parent involvement in early learning was based on the Involve Interview (Webster-Stratton et al. 2001) and Parent Perceptions of Parent Efficacy (PPPE; Hoover-Dempsey, et al. 1992). Parents completed the Involve 12-item Commitment to Education subscale (e.g., “How important is it to you that your child reads or looks at books?”; rated from (1) “Not important” to (5) ”Extremely Important”) as well as four items about involvement at school and home (e.g., “How often did you help your child with school-type activities (like reading together)?”; rated from (1) “Never” to (5) “Everyday”). Internal consistency was high (α = 0.80–0.82). Four items from the PPPE assessed efficacy related to school (e.g., “I know how to help my child do well in school”; rated from (1) “Strongly Agree” to (5) “Strongly Disagree”). Internal consistency was adequate (α = 0.73–0.74). The two measures were correlated (r = 0.40, p < 0.001) and combined (stability = 0.62).

Teacher report of parent involvement was obtained on a 6-item subscale of the Involve (Webster-Stratton et al. 2001) about school activities (e.g., “How often has this parent asked questions or made suggestions about his/her child?”; rated from (1) “Never” to (5) “More than once per week”). Internal consistency and stability were adequate (α = 0.74–0.81; r = 0.62).

Child Conduct Problems

Parents rated child behavior during the past 4 weeks on the New York Rating Scale (NYRS; Miller et al. 1995). The NYRS covers the full range of age-relevant disruptive behaviors, including behavioral dysregulation, aggression, and covert conduct problems (26 items; e.g., “defiant,” “loses temper,” “hits or pushes,” “steals”) rated as 0 (“Not at all”), 1 (“Just a little”), 2 (“Pretty much”), and 3 (“Very much”). The NYRS has strong psychometric properties, including sensitivity to intervention (Collett et al. 2003). Scoring for this preschool-aged sample was modified based on consideration of item endorsement and stability (from age 4 to 6) in the control condition: (1) three items were eliminated (since they were never or almost never endorsed; “deliberately hurts animals,” “has run away from home,” “used a knife or other weapon in a fight”); (2) all items were re-coded from a 4-point scale to 0 or 1 (most items were coded 1 if they were endorsed “pretty much” or “very much”; five items were coded 1 if endorsed “just a little” or more since any occurrence is clinically meaningful [e.g., “assaults others,” “physically cruel”]). The modified 23-item measure of conduct problems was reliable (α = 0.75–0.87) and stable (r = 0.48).

Baseline Child Behavioral Dysregulation

Baseline child behavioral dysregulation, the indicator of child-level risk, was assessed with a subset of the conduct problems measure; 14 items tap aspects of dysregulation (e.g., non-compliance, tantrums), considered hallmarks of the “early-starter” pathway. Analyses in the control condition support reliability (α = 0.84, stability = 0.64) and predictive validity: behavioral dysregulation (age 4), defined as the top quintile in the current sample, was associated with increased conduct problems at age 6 (high-risk boys (23 %)—M = 4.00, SD = 5.56 vs. low-risk boys—M = 0.87, SD = 1.80, p = 0.004; high-risk girls (17 %)—M = 2.00, SD = 2.35 vs. low-risk girls—M = 0.74, SD = 1.89, p = 0.007). Behavioral dysregulation also predicted harsh and inconsistent behavior management as expected (over time and by sex; all p values <0.01).

Analytic Approach

Multiple Imputations for Missing Data

Of the 1,050 children enrolled in the trial, 92 % remained in the study in kindergarten (92 % intervention, 93 % control). Attrition was largely due to children transferring to schools closer to home after pre-k (6 % in both conditions); fewer than 2 % withdrew. Teacher-report data were obtained at baseline and at least one additional time for 96 % of cases (N = 1,003); imputation was not performed for teacher report given the high rate of completeness (and since there is only one teacher-report variable in the study, imputation would not have yielded additional information). Of the 831 parents who completed at least one interview (79 % of the sample), parent-report data were available on 90, 82, and 81 % at the three times, respectively. High serial auto-correlations across the three time points and observed values of the four parent-reported variables allowed for reliable imputation (N = 831). Twenty imputations were generated separately for control and intervention conditions (Little and Rubin 2002). There were no differences by intervention condition in the percent of missing data at any time point for parent or teacher data (p > 0.10). Comparison of the analytic sample to cases without parent-report data (N = 831 vs. 219) revealed no differences on neighborhood-level characteristics by intervention condition (p > 0.10).

Evaluation of Intervention Effects

Following intent-to-treat principles, outcomes (time = 0, 1, and 2) were modeled as a function of intervention (0 = control; 1 = intervention), time, and their interaction, adjusting for baseline value of outcome (0 to 3). A non-significant intervention-by-time interaction indicates that the magnitude of the intervention effect does not change over time; and in that case, the common effect over time is estimated from a reduced model that includes main effects only. Standard errors were adjusted to account for repeated assessments and clustering of children within schools, the unit of randomization. The intra-class correlations for schools were small (parent-report, ICC = 0–0.04; teacher-report, ICC = 0.02–0.08). To evaluate potential moderators of intervention effects (i.e., baseline parenting, behavioral dysregulation, child sex), the moderator-by-intervention term was added to the models above.

Family Program Participation and Dose–Response

The following predictors of participation in the family program (attendance at 0 to 13 sessions) were evaluated in bivariate and multivariate analyses: baseline parenting, baseline dysregulation, sex, ethnicity, parent unemployment, parent SES (dichotomous indicator for single parent, low education, large family size, or receipt of public benefits), and neighborhood SES (poverty, unemployment). Dose–response analyses considered the relation between participation and change in parenting.

Analyses were conducted using SAS® software, version 9.3 of the SAS System (SAS Institute Inc. 2011); Proc MI and Proc MIANALYZE were used to impute, merge, and analyze data, and Proc MIXED was used to evaluate intervention effects, with consideration of nested data.

Results

Intervention Effects on Parenting

Intent-to-treat analyses showed intervention effects on knowledge (d = 0.32, p < 0.001), positive behavior support (d = 0.16, p = 0.032), and teacher-rated parent involvement (d = 0.38, p < 0.001; Table 2). None of these effects were moderated by baseline parenting or child dysregulation (intervention-by-moderator p values >0.10), indicating that the intervention effect on parenting was similar across levels of baseline risk.

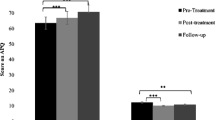

There were moderated intervention effects for the other two measures of parenting. For parent-rated involvement, the corresponding baseline measure was a significant moderator (intervention-by-involvement Est = −0.19, SE = 0.07, p = 0.006); among parents with lower levels of involvement, there was an intervention effect on Parent Involvement (at 1 SD below the mean; d = 0.30, p < 0.001). For harsh and inconsistent behavior management, baseline dysregulation was a significant moderator (intervention-by-dysregulation Est = −0.3.17, SE = 1.64, p = 0.054), such that among parents of children with high levels of dysregulation (20 % of the sample), there was an intervention effect to reduce harsh and inconsistent behavior management (d = 0.28, p = 0.031). As shown in Fig. 2, the level of harsh and inconsistent behavior management post-intervention in high-risk families (i.e., those with dysregulated children) was as low as that reported by lower-risk families.

Intervention effect on post-intervention outcomes (end of pre-k to end of kindergarten) moderated by baseline child behavioral dysregulation. Note. High-risk = highest 20% on baseline behavioral dysregulation. Figure portrays the overall moderation effect across time. Error bars denote the 95% confidence interval for the estimate of the mean. For conduct problems, the figure portrays the intervention effect for boys only. * p<.05 for the intervention effect within risk group

Intervention Effect on Conduct Problems

Although there was no main effect on conduct problems (Est = 0.10, SE = 0.14, p = 0.468), there was a significant moderated effect (intervention-by-dysregulation-by-sex Est = −1.82, SE = 0.69, p = 0.009). For dysregulated boys (but not girls), there was an intervention effect on conduct problems (intervention-by-dysregulation Est = −1.24, SE = 0.52, p = 0.018; high-risk boys—d = 0.52, p = 0.026). Intervention “normalized” the level of problems in high-risk boys to that of low-risk boys (Fig. 2).

Intervention Participation and Dose–Response

Nearly 100 % of teachers in intervention schools participated in professional development, and 80 % of pre-k teachers received additional training and experience as facilitators of the family program. The majority (58 %) of families participated in the family program, ranging across schools (44–75 %) and increasing over the 4 years of implementation (50–65 %). Among pre-k families in intervention schools, average attendance was 4.2 of 13 sessions; family program participants averaged more than half the sessions (7.2 of 13). Attendance was not predicted by a broad range of characteristics (i.e., neighborhood SES, ethnicity, child sex, baseline parenting, dysregulation; p > 0.10 for bivariate and conditional associations). In the multivariate model, there were two predictors; unemployed parents attended one more session than employed parents (B = 1.13, SE = 0.40, p = 0.005) and the lowest-SES families attended one fewer session than others (B = −1.17, SE = 0.42, p = 0.006).

Dose–response analyses showed that the number of sessions attended was related to change in parenting, with a monotone linear increase of the intervention effect with each additional session attended (Knowledge—Est = 0.97, SE = 0.15, p < 0.001; Positive Behavior Support—Est = 0.40, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001). For heuristic purposes, we examined outcomes for children who received “full dose” or “partial dose” relative to controls. We considered children in intervention schools to have received “full dose” if parents attended five or more of the 13 sessions (just above the average). Nearly 40 % of children received “full dose” (increasing from 32 to 45 % over 4 years), with families attending an average of 10 sessions (Mean = 9.8, SD = 2.3, Median = 10). Of the remaining 20 % with some participation, half attended one session and half attended two to four sessions. Relative to controls, intervention effects for families who received the “full dose” were as follows: Knowledge (d = 0.62, p < 0.001), Positive Behavior Support (d = 0.33, p < 0.001), Teacher-rated Parent Involvement (d = 0.60, p < 0.001). For high-risk boys who received “full dose,” the effect on Conduct Problems was d = 0.79 (p = 0.067). There was also meaningful impact on two outcomes for families receiving “partial dose”: Teacher-rated Parent Involvement (d = 0.25, p = 0.016) and Conduct Problems (for high-risk boys, d = 0.49, p = 0.195).

Discussion

This study replicates and extends the results of the first trial of ParentCorps, which documented impact on parenting knowledge, positive behavior support, and child behavior immediately following intervention (Brotman et al. 2011). Intent-to-treat analyses in the current trial found maintenance of effects on parenting knowledge, positive behavior support, and involvement in early learning one year after completion of the family program. Among the highest-risk families, there were additional effects on harsh and inconsistent behavior management and conduct problems. Sustained impact across domains and informants is meaningful given the dearth of trials that document lasting effects on parenting (Sandler et al. 2011), particularly in the context of poverty-related stressors that make parenting more difficult.

Positive impact on three critical domains of parenting (positive behavior support, behavior management, involvement in early learning; effect sizes ranged from 0.16 to 0.38 SD) is consistent with our previous report of impact on academic achievement for all children and obesity prevention and health promotion among behaviorally dysregulated children in this trial (Brotman et al. 2012, 2013). The prevention of conduct problems (e.g., hitting, cheating at games, stealing; effect size = 0.52 SD), which increased sharply from age 4 to 6 among dysregulated boys in the control condition, may indicate an important shift off the “early-starter” pathway to antisocial behavior, substance use, and school dropout. Population impact, and return on investment related to changes in this subgroup alone, may be substantial given that boys on the early-starting pathway are ultimately responsible for almost half of juvenile crime and three-fourths of violent crime (Offord et al. 1991). Additional population-level benefits may be conferred via reductions in disruptive behavior for entire classrooms of students in disadvantaged areas (Kellam et al. 1998). We are currently examining whether this is one of the mechanisms underlying the main effect of ParentCorps on academic achievement (Brotman et al. 2013).

Future work will explore the developmental trajectory for high-risk girls and the possibility of sex-specific relations between early dysregulation and later behavioral, education, and health outcomes. We previously reported intervention impact on health for both dysregulated girls and boys (Brotman et al. 2012); the effect on BMI was similar for boys and girls, but the mechanisms appear to be sex-specific (decreased sedentary activity in girls, increased physical activity in boys). Ongoing follow-up will help clarify whether dysregulated girls were not at risk for conduct problems, whether intervention failed to prevent conduct problems for this subgroup, or whether impact is detectable later, given an expectation of later age of onset for girls.

The moderated intervention effects in the current study are consistent with a growing prevention literature showing a pattern of greatest benefit for the highest risk (e.g., Reid et al. 2004). This type of protective interaction indicates that intervention mitigated the impact of baseline risk factors. It is particularly noteworthy that intervention reduced the prospective relation from dysregulation (for boys and girls) to harsh and inconsistent behavior management. A substantial literature documents “child effects” on parenting (e.g., Pardini et al. 2008), but attenuation of the “child effect” has rarely been reported. It is plausible that increases in knowledge and skill allowed parents to experience some success in modifying their children’s behavior. Over time, these successes may have reinforced the use of effective practices even when dysregulated behavior made it difficult, thereby reducing harsh and inconsistent practices.

High rates of family participation and sustained impact on parenting in disadvantaged urban neighborhoods support a school-based delivery model and culturally informed approach to supporting families. In this diverse sample, the majority of families participated. By the fourth year of implementation, 65 % of families participated and almost half received “full dose” (attending an average of 10 sessions). These rates are substantially higher than those of other prevention programs in community settings (10–25 % of families; for review, Spoth and Redmond 2000). Given the historic underutilization of services by minority families, this level of participation is noteworthy and may be attributed to engaging families at a key developmental transition and to the culturally informed approach to behavior change. Importantly, participation was not predicted by family ethnicity, neighborhood poverty, baseline parenting, or dysregulation. This indicates that the program reached diverse families, including those in greatest need of preventive services. Together with a study of barriers among a subsample of parents who came to few or no sessions (data available from authors), these findings underscore the potential for widespread acceptability, reach, and impact.

The value of integrating a parenting intervention within a school setting is further supported by the finding of positive impact on multiple domains of parenting, including parent involvement as rated by teachers, and for those at highest risk, parent confidence and involvement in early learning activities at home. These aspects of parenting are important for long-term educational success and are not typically targeted by parenting interventions. Likewise, school-based programs that promote parent involvement do not typically address behavioral parenting practices. Further, maintenance of effects to the end of kindergarten stands in contrast to inconsistent Head Start impacts (e.g., Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families 2012) and the “fade out” often observed after transitions from enriched early childhood programs to kindergarten in different settings (e.g., Webster-Stratton et al. 2001). The lasting impact of ParentCorps may be attributed to a range of factors, including the integration of components for parents, teachers, and children, the provision of intervention for pre-k and kindergarten teachers, and a shift in the school culture toward greater value for and active engagement of parents.

Although this trial was not designed to disaggregate the intervention components, dose–response analyses offer some insight. Parenting knowledge and positive behavior support increased substantially for families who participated; otherwise, there was no change. For parent involvement in early learning and conduct problems, the largest effects occurred when families participated, but there were also benefits when they did not participate. This is consistent with the dose–response for achievement test scores (Brotman et al. 2013) and suggests that there were meaningful changes at school. Future work will explore meditational pathways linking changes in parenting, classroom quality, and child self-regulation to academic and behavioral outcomes.

This cluster RCT meets rigorous design and implementation standards, and confidence in generalizability is strengthened by enrollment of nearly 90 % of the pre-k population. Yet, there are several limitations. First, the number of randomization units (schools) was small, increasing the potential for Type 1 error. Second, multiple informants and methods were used to assess parenting, but only parents reported on conduct problems, and both parents and teachers were aware of intervention condition. Third, we cannot completely eliminate the possibility of sample selection bias; although the phased consent procedure resulted in close to complete participation in the trial (including student data from school records), 21 % of parents opted out of interviews. It is possible that those with parent-report data (N = 831) are not a random subsample; however, the consent rate was similar in the two conditions, and there were no differences on measured variables between those with and without consent for parent interviews. Further, attrition from the trial was low and comparable by condition, and all indications support the validity of inferences based on imputed parent-report data (e.g., similar estimates with or without imputation). Ongoing follow-up of child behavior in the classroom via teachers and observers masked to condition, and standardized test scores obtained for all children who remain in NYC schools (>98 %) will provide unbiased tests of impact. Previous reports of impact on achievement test scores (Brotman et al. 2013) and BMI (per objective measures of height and weight; Brotman et al. 2012) suggest that the observed effects are not due to bias. Finally, although 10 % of the sample was Latino, non-English speakers were excluded from the trial. We are preparing to evaluate ParentCorps in this growing population, including formative work that considers the need for program adaptation (e.g., Calzada et al. 2013).

Conclusion and Implications

ParentCorps is a population-level, family-centered, school-based approach to mitigate the adverse effects of poverty on child development. Together with evidence of positive impact on academic achievement and health (Brotman et al. 2012, 2013), this study suggests the promise of early childhood prevention to yield broad benefits for low-income, minority children. Implications for policy and practice include the need to effectively engage parents as an essential component of early childhood initiatives to promote healthy development, reduce the achievement gap, and break the cycle of disadvantage. At minimum, this entails active engagement, support and feedback to families and educators; the common practice of simply disseminating information to parents and teachers is very unlikely to support the sustained changes in behavior needed for population-level impact (Yoshikawa and Weiland 2013). The infrastructure for more comprehensive, family-centered programming is being established with quality rating improvement systems (QRIS) in nearly half of the states. In New York, the QRIS includes family engagement as a key quality indicator: “Actively engaging parents in the early education of their children is essential to children’s success in the elementary classroom and later learning.”

In closing, we reflect on the disproportionate burden of poverty, discrimination, and violence experienced by minority children, particularly boys, and the formidable task faced by their families. Findings suggest the potential for ParentCorps to bolster families as they weather the stressors of urban disadvantage and to shift young boys at high risk for conduct problems from a dangerous path to one of opportunity and success.

References

Baumrind, D., Larzelere, R. E., & Cowan, P. A. (2002). Ordinary physical punishment: Is it harmful? Comment on Gershoff (2002). Psychological Bulletin, 128, 580–589.

Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2012). Child development in the context of adversity: Experiential canalization of brain and behavior. American Psychologist, 67, 309–318.

Brotman, L. M., Kingston, S., Bat-Chava, Y., Calzada, E. J., & Caldwell, M. (2008). Training school personnel to facilitate a family intervention to prevent conduct problems. Early Education and Development, 19, 622–642.

Brotman, L. M., Calzada, E. J., Huang, K. Y., Kingston, S., Dawson-McClure, S., Kamboukos, D., & Petkova, E. (2011). Promoting effective parenting practices and preventing child behavior problems in school among ethnically diverse families from underserved, urban communities. Child Development, 82, 258–276.

Brotman, L. M., Dawson-McClure, S., Huang, K. Y., Theise, R., Kamboukos, D., Wang, J., & Ogedegbe, G. (2012). Family intervention in early childhood and long-term obesity prevention among high risk minority youth. Pediatrics, 129, e621–e628.

Brotman, L. M., Dawson-McClure, S., Calzada, E. J., Huang, K. Y., Kamboukos, D., Palamar, J. J., & Petkova, E. (2013). A cluster (school) randomized trial of ParentCorps: Impact on kindergarten academic achievement. Pediatrics, 131, e1521–e1529.

Calzada, E. J., Basil, S., & Fernandez, Y. (2013). What Latina mothers think of evidence-based parenting programs. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20, 362–374.

Collett, B. R., Ohan, J. L., & Myers, K. M. (2003). Ten year review of rating scales. V: Scales assessing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 1015–1037.

Cox, M. J., Mills-Koonce, R., Propper, C., & Gariepy, J. L. (2010). Systems theory and cascades in developmental psychopathology. Development & Psychopathology, 22, 497–506.

Hill, N. E., & Craft, S. A. (2003). Parent-school involvement and school performance: Mediated pathways among socioeconomically comparable African-American and Euro-American families. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 74–83.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Bassler, O. C., & Brissie, J. S. (1992). Explorations in parent-school relations. Journal of Education Research, 85, 287–294.

Kellam, S. G., Ling, X., Merisca, R., Brown, C. H., & Ialongo, N. (1998). The effect of the level of aggression in the first grade classroom on the course and malleability of aggressive behavior into middle school. Development and Psychopathology, 10, 165–185.

Knight, G. P., Virdin, M., & Roosa, M. (1994). Socialization and family correlates of mental health outcomes among Hispanic and Anglo American children: Consideration of cross-ethnic scalar equivalence. Child Development, 65, 212–224.

Lansford, J. E., Deater-Deckard, K., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (2004). Ethnic differences in the link between physical discipline and later adolescent externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 45, 801–812.

Lansford, J. E., Chang, L., Dodge, K. A., Malone, P. S., Obruru, P., Palmerus, K., & Quinn, N. (2005). Physical discipline and children’s adjustment: Cultural normativeness as a moderator. Child Development, 76, 1234–1246.

Little, R., & Rubin, D. (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Lundahl, B., Risser, H. J., & Lovejoy, M. C. (2006). A meta-analysis of parent training: Moderators and follow-up effects. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 86–104.

MacKenzie, M. J., Nicklas, E., Waldfogel, J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2012). Corporal punishment and child behavioural and cognitive outcomes through 5 years of age: Evidence from a contemporary urban birth cohort study. Infant and Child Development, 21, 3–33.

Miller, L. S., Klein, R. G., Piacentini, J., Abikoff, H., Shaw, M., Samoilov, A., & Guardino, M. (1995). The New York Teacher Rating Scale for disruptive and antisocial behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 359–370.

Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families. (2012). Third grade follow-up to the Head Start Impact Study final report (#2012-45). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Offord, D. R., Boyle, M. H., & Racine, Y. A. (1991). The epidemiology of antisocial behavior in childhood and adolescence. In D. J. Pepler & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), The development and treatment of childhood aggression (pp. 31–54). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Olds, D., Henderson, C. R., Cole, R., Eckenrode, J., Kitzman, H., Luckey, D., & Powers, J. (1998). Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children’s criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280, 1238–1244.

Ortiz, C., & Del Vecchio, T. (2013). Cultural diversity: Do we need a new wake-up call for parent training? Behavior Therapy, 44, 443–458.

Pardini, D. A., Fite, P. J., & Burke, J. D. (2008). Bidirectional associations between parenting practices and conduct problems in boys from childhood to adolescence: The moderating effect of age and African-American ethnicity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 647–662.

Patterson, G. R., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (1984). The correlation of family management practices and delinquency. Child Development, 55, 1299–1307.

Raver, C. C., Garner, P., & Smith-Donald, R. (2007). The roles of emotion regulation and emotion knowledge for children’s academic readiness: Are the links causal? In B. Pianta, K. Snow, & M. Cox (Eds.), Kindergarten transition and early school success (pp. 121–148). Baltimore: Brookes Publishing.

Reid, M. J., Webster-Stratton, C., & Beauchaine, T. P. (2001). Parent training in Head Start: A comparison of program response among African American, Asian American, Caucasian, and Hispanic mothers. Prevention Science, 2, 209–227.

Reid, M. J., Webster-Stratton, C., & Baydar, N. (2004). Halting the development of conduct problems in head start children: The effects of parent training. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 33, 279–291.

Sandler, I. N., Schoenfelder, E. N., Wolchik, S. A., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2011). Long-term impact of prevention programs to promote effective parenting: Lasting effects but uncertain processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 299–329.

SAS Institute Inc. Base SAS ® 9.3 Procedures Guide. Cary, NC: Copyright © 2011.

Shaw, D. S., Bell, R. Q., & Gilliom, M. (2000). A truly early starter model of antisocial behavior revisited. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 3, 155–172.

Shaw, D. S., Dishion, T., Supplee, L., Gardner, F., & Arnds, K. (2006). A family-centered approach to the prevention of early-onset antisocial behavior: Two-year effects of the family check-up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 1–9.

Shonkoff, J., Garner, A., & Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood Adoption and Dependent Care, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129, e232–e246.

Spoth, R., & Redmond, C. (2000). Research on family engagement in preventive interventions: Toward improved use of scientific findings in primary prevention practice. Journal of Primary Prevention, 21, 267–284.

Stine, N. W., Chokshi, D. A., & Gourevitch, M. N. (2013). Improving population health in US cities. Journal of the American Medical Association, 309, 449–450.

Webster-Stratton, C. (1998). Preventing conduct problems in Head Start children: Strengthening parenting competencies. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 66, 715–730.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Hammond, M. (2001). Preventing conduct problems, promoting social competence: A parent and teacher training partnership in Head Start. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 283–302.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Hammond, M. (2004). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: Intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 105–124.

Yoshikawa, H. & Weiland, C. (2013, October 11). Investing in our future: The evidence base on preschool education. Retrieved from: http://fcd-us.org/resources/evidence-base-preschool.

Zubrick, S. R., Ward, K. A., Silburn, S. R., Lawrence, D., Williams, A. A., Blair, E., & Sanders, M. R. (2005). Prevention of child behavior problems through universal implementation of a group behavioral family intervention. Prevention Science, 6, 287–304.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dawson-McClure, S., Calzada, E., Huang, KY. et al. A Population-Level Approach to Promoting Healthy Child Development and School Success in Low-Income, Urban Neighborhoods: Impact on Parenting and Child Conduct Problems. Prev Sci 16, 279–290 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-014-0473-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-014-0473-3