Abstract

The spread of GPS-based location services using smartphone applications has led to the rapid growth of new startups offering smartphone-enabled dispatch service for taxicabs, limousines, and ridesharing vehicles. This change in communicative technology has been accompanied by the creation of new categories of car service, particularly as drivers of limousines and private vehicles use the apps to provide on-demand service of a kind previously reserved for taxicabs. One of the most controversial new models of car service is for-profit ridesharing, which combines the for-profit model of taxi service with the overall traffic reduction goals of ridesharing. A preliminary attempt is here made at understanding how for-profit ridesharing compares to traditional taxicab and ridesharing models. Ethnographic interviews are drawn on to illustrate the range of motivations and strategies used by for-profit ridesharing drivers in San Francisco, California as they make use of the service. A range of driver strategies is identified, ranging from incidental, to part-time, to full-time driving. This makes possible a provisional account of the potential ecological impacts of the spread of this model of car service, based on the concept of taxicab efficiency, conceived as the ratio of shared versus unshared miles driven.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

San Francisco has emerged as a proving ground for a number of new-tech startups which use GPS locating to allow passengers to “hail” nearby taxis, limousines, and other vehicles, using mobile smartphone applications. Funded by Silicon Valley venture capital, these services bypass traditional forms of dispatch to establish more direct, trackable connections between drivers and passengers. The most controversial of these are marketed as “ridesharing” services, in which transportation is provided, not for a price, but a calculated donation alone.

Framed as “ridesharing”, “ride-matching”, or “peer-to-peer” services, these companies connect passengers with informal “community” drivers, driving private vehicles, through a smartphone app. Instead of being charged a set rate of fare, passengers typically pay a suggested donation, at a rate competitive with taxi service, of which the company takes a percentage.Footnote 1 Regulators are struggling to determine whether to treat these as taxicab services (which are heavily regulated), or as ridesharing (which is relatively exempt from regulation). Unlike traditional taxi services, drivers and vehicles are unlicensed, and driver (and vehicle) supply is more flexible. Unlike traditional ridesharing (such as car-pooling and van-pooling, as well as new “dynamic” ridesharing models (Agatz et al. 2010), drivers can make an income from the service. Supporters claim this is necessary to achieve a “critical mass” of regular drivers and passengers, while detractors claim that it erodes the distinction between licensed taxis and unlicensed ridesharing vehicles. A competitor complained that for-profit ridesharing companies are engaged in “regulatory arbitrage,” seeking to reduce costs and avoid regulations by operating de facto taxis under the less regulated “ridesharing” category (Kalanick and Hempel 2013).

In this paper, these services will be referred to as for-profit ridesharing, for the purpose of comparison and contrast with both traditional ridesharing and traditional taxi service. First, a brief overview will be given of the development of e-hailing services in San Francisco; second, economic models for traditional taxicab and ridesharing services will be contrasted. Third, ethnographic interviews with for-profit ridesharing drivers in San Francisco will be drawn on to illustrate the range of driving strategies reported by drivers and/or observed through participant observation as a passenger. Traditional ridesharing, in particular, has been promoted as an ecologically desirable means of reducing vehicle miles of travel (VMT), a fact cited by promoters of for-profit ridesharing as an argument in favor of their own model; for this reason, attention will be paid to the question of whether, and to what extent, these differing services have the potential to increase or decrease overall VMT.

E-Hailing in San Francisco

The potential for decentralized car services dispatched via mobile phone was recognized over a decade ago (Rheingold 2002; Anderson 2004, p. 259). Known popularly as “e-hailing” (Krohe 2013), it was not until internet-enabled smartphones became common that such services began to proliferate.Footnote 2 During this same period, the regulatory and political economic context of cabdriving in San Francisco was also radically transformed by the emergence of regulatory bodies—first the Taxicab Commission, and since 2009 the San Francisco Metropolitan Transportation Agency (SFMTA)—which have sought to modernize the industry technologically, and integrate taxis into a city-wide “Transit First” infrastructure (SFMTA 2012). These regulators have pushed the transition from radio to GPS-based computerized dispatch, and have mandated or encouraged the installation of surveillance cameras, credit card terminals, backseat PIMs, and electronic waybills to automate the collection of information on trips, fares, and driver incomes. These local developments reflect a broader renewed interest among planners and regulators in the potential role of taxicabs in an integrated transit system (cf. Cooper et al. 2010), which has brought new flows of investment and profit-making into the industry, along with political struggles over who will bear the cost of these devices—drivers, vehicle owners, or passengers—and has shaped the context in which subsequent technologies, such as smartphone apps, are adopted by the industry (cf. Anderson 2012).

By 2009 there were at least two companies using smartphone apps to dispatch a portion of San Francisco’s taxi fleet. In 2010 the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA), responding to an initiative proposed by drivers, began to explore the development of Open Taxi Access (OTA) a program to develop a smartphone app giving access to every taxicab in the city. Yet by mid-2011 OTA had been derailed, reportedly by the opposition of the large taxi companies, who saw it as a threat to the investments they had already made in new dispatch technology, at least in part at the behest of the MTA (Han 2011). With the demise of the fleetwide app, taxi e-hailing was left in the hands of private services, each linked to only a portion of the taxi fleet. As of this writing, there are three app services in San Francisco linked solely to taxicabs; a fourth company dispatches both taxis and for-profit ridesharing vehicles, and a fifth dispatches taxis, limousines, and for-profit ridesharers. A resurrected OTA plan, rebranded Electronic Taxi Access, is once again in development.

The slow penetration of taxi e-hailing apps left the field open for similar services designed to avoid the regulatory hurdles faced by taxicab dispatch. An e-hailing service for limousines launched in 2010, taking advantage of the looser regulatory oversight to which limousines are subject in California; in particular, the lack of a limit on the number of limousines allowed this service to grow much more rapidly than taxi e-hailing services (Daus 2012). The three for-profit ridesharing companies whose drivers were interviewed for this study were launched in 2012, taking advantage of the exemptions granted to ridesharing by California transportation regulators. The services distinguish themselves from taxi services either through an annual cap on driver income, or by charging passengers a “suggested donation” rather than a set fare. In addition, these services use the private vehicles owned by drivers themselves, and insist that drivers are not technically employees of the services.Footnote 3

By calling themselves “ridesharing,” these services claim the heritage of traditional carpooling and ridesharing efforts. Casual carpooling, in which cars and passengers meet and drop off at established locations, dates from at least the 1970s in the Bay Area, and is most commonly associated with the cross-bay commute. In recent years interest has grown in using e-hailing or similar internet technologies to develop “dynamic” ridesharing networks, which could form or alter in real-time to meet the changing destinations of riders and drivers, instead of relying on fixed networks or pre-arrangement (Deakin et al. 2010; Heinrich 2010). At least three app-based traditional ridesharing companies are currently operating in the Bay Area; however, these differ from for-profit ridesharing in that the driver typically bears some or all of the cost of the ride. Proponents of these traditional ridesharing services have publicly argued that for-profit ridesharing is “not ridesharing” and should be characterized as taxi services based on the prices charged.Footnote 4

Since this study was conducted, the California Public Utilities Commission embarked on proceedings to establish a regulatory framework for these services. The Commission rejected the argument that these services constitute “ridesharing”, yet allowed them to operate by establishing a new regulatory category, “Transportation Network Carriers” (see below). Despite the PUC’s ruling, these services are still referred to as “ridesharing” in the media and popular discourse, although they are increasingly refered to as “cabs” or “taxis” as well. In this paper, I chart a cautious course between two agendas. Rather than seeking to resolve the issue by defining these services into one category or the other (taxis or ridesharing), I aim to follow the contours of the controversy as it is deployed by those involved (Latour 2005), particularly ridesharing drivers; and the hybrid name “for-profit ridesharing,” which some would argue is a contradiction in terms, was chosen for this reason. On the other hand, it is worth asking how stable a hybrid this is, and what its effects are likely to be. For this reason it is useful to turn to models of the structural elements involved in taxidriving and ridesharing, which give some predictive insight into patterns of behavior likely to be associated with these occupations.

Traditional taxicab and ridesharing models

For-profit ridesharing combines elements of traditional ridesharing and taxi service. In terms of sustainability and access to transportation, both traditional ridesharing and taxis can be understood as having both additive and subtractive effects on overall vehicle miles travelled (VMT):

-

1.

As additive services both taxis and traditional ridesharing can provide increased access to transportation, for instance to non-car-owners, or non-drivers;

-

2.

As subtractive services both taxis and ridesharing may reduce overall VMT, for example by encouraging shared rides, supplementing fixed-route transit systems by enabling multi-modal trips,Footnote 5 and eliminating wasteful driving such as searching for parking.

Nevertheless, taxis and traditional ridesharing services differ in their emphases. Taxi service is primarily additive, and is regulated with the provision of access to transportation in mind (Cooper et al. 2010). Traditional ridesharing has been primarily subtractive, on the premise of reducing VMT by encouraging drivers to ride together rather than separately (e.g., Wiersig 1985).

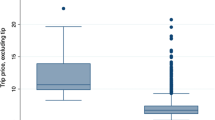

Taxis can be modelled in terms of their efficiency in providing this additive transportation service. Scholars who have modelled taxi systems have focused on the relationships between taxi supply, demand, pricing, and efficiency (e.g., Douglas 1972; Arnott 1996; Flores-Guri 2005). Such models can be useful for revealing structural relationships between these factors. Taxicab efficiency can be calculated in terms of time or distance, and refers to the ratio of paid time or mileage for which a taxicab is occupied by a passenger, as opposed to the unpaid time spent, or miles driven, without a passenger (cf. Arnott 1996). For instance, a taxicab driver may drive for a shift of 10 or 12 h and be paid only for a portion of that time; the rate of compensation for paid miles thus has to subsidize the empty miles during which the cabdriver is “dead-heading” (driving empty) to reach fares, as well as time spent waiting. Focusing on trip miles alone, and taking the reduction of VMT as an ecologically desirable goal, the ecological efficiency of taxis can be defined as the ratio of (efficient, paid) distance driven with a passenger to the (inefficient, unpaid) distance driven empty.

From a driver’s perspective, a reasonable model of taxi operation would be the following:

Here, P is the price of the taxi fare per mile; Q is occupied mileage; V is vacant mileage; c is the driver’s cost per mile, and I is the minimal expected income for which the driver will keep working.Footnote 6 Put simply, the price for paid miles must be sufficiently greater than the cost of both paid and unpaid miles to leave a sufficient income for the driver. With T as the total miles driven, taxicab efficiency can be represented as Q/T. Regulators have an interest in promoting taxi efficiency, not only because inefficient taxi miles contribute to pollution and congestion, but because a more efficient system justifies a lower price for taxi fares. Limousines, for example, typically operate at a lower level of efficiency than taxis, taking fewer fares per day at a higher price.

In contrast, traditional ridesharing occurs either without the driver receiving payment, or with both passenger and driver sharing some costs of the ride. Chan and Shaheen (2012), for instance, define ridesharing as non-profit, and Agatz et al. (2010) assume cost-sharing among driver and passenger(s). The fact that the driver shares some of the cost of the trip is instrumental to the subtractive goal of ridesharing as a way of lessening overall VMT, presuming that the driver would take the trip with or without a passenger, and so has no objection to sharing costs. Assuming costs are split evenly by one driver and one passenger, traditional ridesharing compensation can be represented using some of the same variables used above for taxis:

Here, P is the reimbursement by the passenger to the driver; c is cost per mile; Q is the efficient, shared portion of the trip, and V is the sum of any route deviation made by the driver from their own planned route to pick up, or return from dropping off, the passenger. N is the number of participants, in this case simply two.Footnote 7 Cost sharing of this sort gives drivers and passengers an incentive to engage in efficient ridesharing, because the cost to each of a shared trip will be less than the cost of driving separately. At the same time, cost sharing discourages inefficient trips in which route deviation V is sufficiently high to negate the savings from the shared ride. A tendency towards efficiency is thus built into traditional, cost-sharing ridesharing.

Unlike traditional ridesharing, for-profit ridesharing allows drivers to make an income, when the expected rate of pay for paid miles is high enough to subsidize unpaid miles. Thus for-profit ridesharing is better represented by the taxi model than by the traditional ridesharing model. However, I, the expected minimum income, is a subjective quantity. In advertising their services as “ridesharing,” for-profit ridesharing companies make their appeal not only to drivers seeking an income but to those who are motivated by the social goal of reducing VMT through shared rides, and who may additionally be willing to share the costs of the rides, in other words to accept a low return, or even no income at all.

One drawback of models such as those outlined above is a built-in assumption that human behavior will follow the predictable, rationalist pattern of homo oeconomicus. Qualitative methods can be used to supplement these models, by providing more in-depth and nuanced accounts of how people behave and are motivated in practice. For this study, ethnographic interviews were used to better understand how drivers for for-profit ridesharing services actually approach the job—specifically, what sorts of spatio-temporal strategies they use while driving, and what motivates them to do so. The models described above delineate the differing sets of economic constraints and motivations built into traditional ridesharing and taxi driving; and the strategies described below will illustrate the ways these constraints and motivations play out in the for-profit ridesharing hybrid.

Driver strategies

Ethnographic approaches, including ethnographic interviews as well as mobile participant observation [or “go-alongs” (Kusenbach 2003)] have shed light on the driving choices and tactics made use of by urban drivers (Katz 2013; Toiskallio 2002), and on the choices and motivations of commuters and urban movers in general (Clifton 2004; Basmajian 2010; Gamberini et al. 2013). Ethnographic studies have provided insight on the experience of ridesharing (e.g., Adler and Adler 1984) and taxi driving (Leonard 2006). The concept of a spatio-temporal strategy is drawn from ethnographic studies of taxicab drivers, and refers to the spatial and temporal choices drivers make to improve income—and avoid danger—while driving through the city (e.g., Cantiello 1974; Davis 1990; Anderson 2004). These strategies link the moment-to-moment tactics and choices employed in driving and interacting with passengers to the driver’s ability to achieve an overall goal or trajectory in the course of the working day, against the background of the economic and organizational demands of their occupation (Schlosberg 1980). For this study, interviews and participant observation (through ride-alongs and the use of the apps for e-hailing) were used to get a sense of the range of motivations and strategies used by for-profit ridesharing drivers as they make use of the service.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twenty drivers for three different for-profit ridesharing companies in San Francisco, from November 2012 to February 2013. Initial in-person interviews were conducted in November and December of 2012 with 12 drivers who were contacted through the smartphone application and interviewed during rides. These interviews lasted between 20 and 40 min; all drivers contacted in this method responded enthusiastically to the request for an interview, and in several cases drivers pulled over at the completion of the ride to continue the discussion.Footnote 8 A further eight drivers were interviewed, three by email, and five by phone or by phone and email; the author was put in touch with these drivers through previous interviewees. By relying on social networks existing among drivers, this snowball method, while ensuring a pool of informed and interested interviewees, does have the potential to distort the results of the interviews by over-representing certain groups of drivers at the expense of others.

Given that this study compares the work strategies of for-profit ridesharing drivers with those of taxi drivers, it is worth considering to what extent these drivers can be compared demographically. This is of course difficult due to the small sample size, and the lack of any comparative data on for-profit ridesharing drivers.Footnote 9 An attempt can be made at comparing them with limousine and taxi drivers, using the Hara Associates 2013 report on the San Francisco cab industry, prepared for the SFMTA; Burgel et al.’s 2012 study using focus groups of San Francisco taxi drivers; a Taxi Driver Survey conducted in 2004 by the San Francisco Taxicab Commission; and Bruce Schaller’s 2004 national study of taxi and limousine drivers, based on 2000 census data. Table 1 lists driver gender, ethnicity, and residence as reported in these studies.

In this study only two of the drivers contacted were female, at ten percent this falls within the range of reported percentages for female taxi drivers in San Francisco. The rest of the table follows the ethnic categories used in the Hara Associates study.Footnote 10 A plurality of White for-profit ridesharing drivers in the sample (45 %) falls within the reported range for taxi and limousine drivers; however, the sample percent of Middle Eastern drivers is much higher (25 %) than that reported for taxi drivers, possibly reflecting the effect of the snowball interviewing method. A more satisfactory statistical comparison of for-profit ridesharing and taxi drivers will have to await better data; for the present I will argue that a substantial number of the for-profit ridesharing drivers interviewed for this study fall into the taxi driver demographic, based on interviewee’s statements that they have previously driven taxis or limousines (5 of 20), or have considered such employment (4 of 20).

A final consideration is the place of residence reported by drivers. Of ridesharing drivers interviewed for this study, only four (20 %) reported living in San Francisco; the rest drove into the city to work as ridesharing drivers. The 2004 SFTC study reported 55.3 % of taxi drivers living in San Francisco; the difference could reveal a difference between ridesharing and taxi drivers, or could reflect the movement of working drivers out of the city in response to rising rent and home prices over the period between the two studies (Solnit 2013).

Although statistical inferences should not be derived from this small convenience sample of a fluid population of hundreds of drivers, it does shed some light on qualitative aspects of driver behavior. These interviews were part of a broader, ongoing study of regulatory and technological change in the San Francisco hired-car industry, focusing also on the use of similar apps to dispatch taxis and limousines. At the time of research, the three for-profit ridesharing services were under cease-and-desist orders from the state of California, and there was an immediate possibility that they could be shut down at any time. The research methodology was shaped, in some degree, by the urgency of studying this phenomenon before its potential disappearance.

The three different for-profit ridesharing companies for which interviewed drivers worked employ slightly differing models, which have effects on driver behavior. The companies are here referred to pseudonymously as Companies A, B, and CFootnote 11:

-

Company A: Drivers commit to assigned shifts of 4–10 h; passengers choose the amount to pay based on suggested donation. Company receives a percentage of donation.

-

Company B: Drivers may turn app on or off at any time, and work as little or as much as they desire. Passengers choose amount to pay based on suggested donation, and company receives a percentage of the donation.

-

Company C: Passengers post desired trips at least 10 min in advance, choosing an amount to offer guided by community average. Drivers are restricted to $8,500 income over 1 year. Company charges a booking fee based on the amount paid.

Based on interviews and on observations made as a user of the applications, drivers for for-profit ridesharing services can be said to fall along a continuum of three basic driving strategies:

-

1.

Incidental drivers, who provide the service only occasionally, for instance while commuting to and from work. These drivers match the “sharing” and “collaborative” image which frames the service as “ridesharing” as opposed to a taxi or limousine service. These are the drivers who are most likely to also use the service as passengers.

-

2.

Part-time drivers, who use the service to supplement income from other employment. Unlike incidentals, part-timers are more likely to work several hours at a time, and to have routine “shifts” they formally or informally fill, such as after work or on weekends. Part-timers may also be students who work a few days a week, in addition to taking classes.

-

3.

Full-time drivers attempt to use the service as a primary means of income. This may mean taking rides over the entire course of the day, or focusing on rush hours, with breaks during slow times. Full-timers are also more likely to be available to accept rides during non-peak hours, such as at night. One full-timer stated that he drove 12 h a day; another said that he was aiming for 60 h a week.Footnote 12

This continuum is divided into three for descriptive purposes; in truth, there is much bleed-over between the categories, and strict divisions between them are merely arbitrary. Also, individual drivers may shift strategies over time. Along with these three general strategies, several more situated spatio-temporal strategies were observed. For each of the three categories above, two additional sub-types are listed below, to further illustrate the variability of driver approaches. This continuum of driver strategies is also a continuum in terms of the applicability of the two driving models described above; the cost-sharing ridesharing model may best describe the motivations of incidental drivers, while the economic and motivational context of full-time driving is best understood with the for-profit taxicab model. Just as these models illustrate different constellations of constraints and motivations for drivers, so do the ensuing driving strategies have different potential impacts in terms of service provided, driving efficiency, and driver VMT.

Incidentals

Morgan,Footnote 13 a young tech professional in his thirties, picked me up in his black SUV in the Mission district after some slight confusion when his GPS sent him to an alley off of 24th Street instead of Valencia, where I was standing. When I introduced myself as a researcher, he enthusiastically responded that he, too, was interested in the “sharing economy.” He himself works for a social media startup which he described passionately for several blocks, including its recent acquisition by a major investment firm. He saw a clear connection between his regular work at the tech startup, and his occasional driving for Company B’s ridesharing service. “The social, cashless economy, it’s the wave of the future,” he explained.

Though he had been driving with Company B for over a month, I was only his fifth passenger:

Morgan: My first three rides I did right in a row as “real rideshares,” I guess you’d say, from home to work and vice versa. I live on Nob Hill and work down by the ballpark [Candlestick], so I turn on the app on the way to work or on the way back when I’m getting off. It’s worked pretty good, there’s always someone going from downtown out to my area, or coming back…. The appeal to me is not economic, I’m not doing it for the money but for the experience.

Today was the first day he’d taken two rides in a row, off of his regular route: First, he had taken a woman from near his work down to the airport, and then while coming back into the city on 101, my call had popped up in the Mission and he had decided to take it. I took him a bit out of his way into the Inner Sunset, but he figured he would keep the app on as he returned across town, and take another fare if he saw one going his way.

Morgan: I don’t always look at the destination [on the app] but sometimes I do, this time I did, when I picked you up, and I figured at least you’re going north. I didn’t want to take you if you were heading south. And especially it’s the time of day, there’s some times when you might get stuck in traffic, and of course there’s some parts of town I don’t want to go to, just for a ride that might be nine dollars.

Morgan is a frequent customer of the two main ridesharing services, along with competing limousine and taxi services. His experience as a customer, he reports, was “part of what got me into it, to see what this is about.” He initially signed up for both Companies A and B but stuck with B because it gave him a more flexible schedule, which he requires because of his regular job:

Morgan: I actually signed up for Company A but really couldn’t do it…. they require you to sign up for schedules, but for my work I have to be very flexible… With Company A you have to set your hours a week in advance, and stick to those hours, you can’t work outside of the hours without pre-approval to use the system.

Morgan is a classic example of the incidental driver who rarely uses the app to give rides to places he was not already going to. A further type of driver who can be classed as incidental is one who drives only for short periods of time, to fill in between other jobs or errands. Such a driver is Jin Hee, who picked me up in his Jetta outside a used bookstore on Clement Avenue in the Richmond. Jin Hee owns his own business which often brings him into the city from his home in Alameda, across the Bay. He has been driving for Company B for two months, a couple days a week, no more than a few hours a day:

Jin Hee: This is not my main job. I have my own business, and I do this when I have free time, like an hour free time. This is not something I do for a living, this is a couple hours every now and then when I feel like working.

[Do you ever come into the city just to do this?]

No, I wouldn’t come into the city for this unless I was already here. I wouldn’t come across the bridge just to do this, it’s not worth it. I just do this, when I’m already in the city, I turn this on for an hour or so when I have some free time.

Based on interviews and observations, incidental drivers can be further distinguished by particular spatio-temporal strategies used to obtain passengers. Thus, commuters take passengers during their own commute, or other pre-planned trips, such as while running errands. Joyriders provide occasional rides “for fun,” to meet people, or because of the appeal of “sharing” rides. These sub-types are not mutually exclusive: for instance Morgan, above, falls into both categories.

Part-timers

Steve had been sitting at his home in Daly City when he received an email with my ride request through Company C. He had been thinking of coming up to San Francisco on this weekend morning to run some errands in Hayes Valley, and since my destination was not far from there, “that decided it.” I was in fact his third passenger for Company C: the first had been the CEO of the company, and the second a rider from Daly City to the Mission, the day before. Steve so far has not driven more than many incidentals, but intends to be a part-time ridesharing driver:

[So do you do this for a living?]

Steve: Now I’m trying to. I signed up for Company A but they said they weren’t taking drivers right now… So I signed up for this, and for Company B, too. I’ll start that soon.

Steve had recently lost the house he owned in the Twin Peaks neighborhood—“it was a very painful process”—and moved south to Daly City. He is attracted to driving as a way to make some extra money to supplement an unsteady income from his primary work:

Steve: I work for the Department of Elections and that’s part time, it’s only full time when we have elections… A friend who also works at elections told me how he was driving for Company B three or four days a week and taking in $80 a day for a couple hours work—I figured, that sounds okay!

He had also looked into driving a taxi part-time, but had decided against it after learning that drivers had to pay the cab companies around a hundred dollars a day to lease a taxi:

Steve: There’s all this BS with taxi drivers. I bet they deal with a lot of shit. Also you have to pay for the license and take a test, then find a company that will take you. With these [ridesharing jobs] you just call, and they call you back, and you go. The cabs have these twelve hour shifts, I can’t do that. I have two ruptured disks and a lumbar problem. I couldn’t drive for that long, sitting in a car. With this job, I can work shorter shifts so my back doesn’t hurt.

Philip was in his twenties, sporting tattoos and Ubangi-style earrings. He had been hanging out South of Market, which is a hot-spot for ridesharing fares, but it was a slow afternoon, so he accepted my hail 15 min away in the Marina. A film student at San Francisco State, he lives south of the city in Burlingame, and drives into the city for school and work. He had been driving about five months, since “pretty much when it was starting.” He had been looking for a job or paid internship in his field, when he saw that Company A was advertising for drivers on craigslist. Company A requires drivers to take shifts of several hours at a time. Philip finds this a convenient way to work a few days a week, which he fits around his school schedule:

Philip: I like the schedule because it is flexible, you can cancel a day ahead of time, if you need to. The way it works is, you send them your availability, and they post blocks of time in which you can choose to work, and you can select from the ones available. Usually you can get the hours you want. I used to work Tuesdays and Thursdays, when school was in session, those were days I had class in the morning, so I’d stay in town and work afterwards.

Class was now out of session for winter break, and Philip had changed his schedule so that he could put in more hours at a time. He works about 7 to 8 h a day, making between 20 and 30 dollars an hour; “if you’re working Friday nights you’re more likely to see the 30 dollar end of that.” Riding 15 min to pick up a call was unusual; typically, a hail would be about 7 min away, or fewer. “But I wouldn’t turn someone down just because they were that far away, like in the Marina or something like that.”

He and other rideshare drivers tend to cluster in the neighborhoods with the majority of calls, and once they have dropped passengers in other neighborhoods, they are pulled back to those neighborhoods by the lure of business:

Philip: I came from SoMa to pick you up, because there’s a lot of fares come out of there. SoMa and the Mission, some will come out of the Haight too. So I’ll probably swing by the Haight on my way back downtown, since I don’t figure I’ll get anything out at Sixth and Clement. So I’ll head back to the Haight or back downtown.

Yet, because other drivers tend also to cluster downtown, Philip had developed some strategies to increase his chances of getting fares:

Philip: If I get a fare out to somewhere like the Haight, where there might be rides, I’ll sometimes pull over and sit there, and see if I get another ride. I’ll wait, because I might get one back downtown. I also look at the app, you can see on the screen where the other cars are, to know where the drivers are, because you don’t want to be right next to anybody. For instance if that car [he points to a car next to us], if that was another Company A driver, anyone calling from that side of us would get him instead of me. So you don’t want to be near anybody. You want to be further away from other drivers.

Making strategic choices to increase income, part-timers like Philip approach their work much more like cabdrivers than like incidentals. When asked about additional attractions of the job beyond money, Philip echoed sentiments commonly expressed by cabdriversFootnote 14:

[Besides money, what other appeals does the job have?]

Philip: Freedom, flexibility, it pays good. You can do it whenever you need to, and you don’t have to be sitting in an office or waiting tables, you can be out with people! You don’t have to work in some customer service setting.

Ahmad is another young driver, and a student at San Jose State. He works at a Costco in Redwood City during the week, and drives for Company B on weekends while he is in San Francisco visiting and hanging out with friends. He has been driving for a few months, and estimates that he has given a total of 37 or 39 rides. His busiest time so far was around Halloween, when demand was high and he worked steadily for two days.

Ahmad: The money from this is not much, but it’s not like my job at Costco, where you have to show up at a certain time, work a set amount of hours, take home a set amount. With this I work when I want, I can work as long or as late as I want, I could come out at 3 AM, and see what business is there… This morning, I couldn’t sleep, so I got up at 6:30 and drove a guy downtown, took another guy to the airport, then picked up some people in the Mission on the way back.

When business slows he parks his car somewhere or goes to his friends’ home and waits there. He appreciates the freedom to work as much or as little of the day as he finds convenient. As he dropped me near Union Square he showed me that he already had another call, 6 min away.

Ahmad: In this job there is never a dull moment!

The spatio-temporal strategies of part-timers can be framed in relation to their other occupations or pursuits. Thus, second-shifters drive a few hours a day before or after a regular job (or school), or drive on weekends. Sitters leave the app on while sitting at home, at a workplace, or a cafe; giving occasional rides as breaks from studying or working.

Full-timers

Bryce had been driving for Company A for 1 week, to support his wife and daughter living in Redwood City, down the peninsula. After spending a year and a half as a stay-at-home dad, he was happy to be working. He had been considering getting a job as a taxi driver, but was put off by the strict requirements and bureaucracy involved:

Bryce: I was thinking about becoming a cabdriver, or maybe a towncar driver. But I learned that this was an easier and quicker process. The cabs, they have all those regulations you have to go through, you have to get a letter of intent [to hire] from a company, and then take all these courses and things that take a week.

He had also applied to Company B, but stuck with Company A because they were the first to schedule him an interview. He liked the feeling of the company and of the people who worked there. Bryce has been working varying shifts, from four to 10 h a day, his goal being 60 h a week. Today his shift was from 7 in the morning to 1 in the afternoon; he estimated that he had had six or eight fares before picking me up. Mine would be his last trip; after dropping me in the Mission, he would head home to Redwood City.

Bryce: You can make about ten dollars an hour, if you take it easy, take breaks, etc. But if you skip all your breaks and work constantly, you can make about twenty dollars an hour…. They seem to take good care of the drivers, they make sure they have enough business for them. They plan it ahead of time, they plan the amount of drivers versus people.

Salem is a licensed cabdriverFootnote 15; in his own words, he is a cabdriver who drives for Company B. When asked if he approached driving as a “job” or as “fun” he unequivocally answered that this was his job. He had driven cabs for about 5 years for several different companies, and had most recently quit to take a half-year vacation to his homeland of Yemen. On returning another cabdriver had talked him into coming to Company B. He said he knew several cabdrivers who worked for both Companies A and B.

Salem finds Company B more convenient to work for than a traditional taxi company. He shares a Tenderloin apartment with three other men from Yemen; instead of having to travel to the southern neighborhoods where the taxi companies are located to pick up a car before starting his day, he simply retrieves his personal car from the parking garage below his apartment. “It is better to drive with my own car. This is how it is changing, this is what people want now.” He owned his own car before becoming a rideshare driver, but said that he knew several drivers who had bought cars in order to drive for Companies A and B, planning to use their income to cover their car payments. Luis, a driver interviewed by phone, confirmed that, after leaving his job at a licensed taxi company, he had bought a pre-owned hybrid sedan to work as his own boss, using two of the ridesharing apps. Both Salem and Luis pointed out that a ridesharing vehicle is “not just a taxi,” but a personal car as well:

Salem: If you don’t have a car, you can get one, doing this job.

The spatio-temporal strategies of full-timers are most like those of cabdrivers, which is not surprising since not a few have cabdriving experience. After dropping off passengers, sandbaggers return empty to wait in the areas with the most calls, such as South of Market. Cruisers, in contrast, actively seek out passengers, such as by moving along the edge of busy zones to increase the size of the region for which they will be the most proximate driver, or by driving against commute traffic into zones with expected demand.

Observations

These three approaches to driving—incidental, part-time, full-time—form a continuum rather than discrete categories. It can be expected that at least some drivers will change strategies over time, and that the composition of these three kinds of drivers will change seasonally, or as these services mature. Of 20 drivers interviewed, I classed 3 as incidentals, 10 as part-timers, and 7 as full-timers; this is at best an imperfect snapshot of the range of driver strategies at the time of the study.

Incidental drivers act the most like traditional ridesharing drivers, and are the least likely to take trips without shared destinations, or to be willing to drive empty any great distance to pick up a fare; thus, they are more likely to perform the VMT-subtractive service of traditional ridesharing. They were more likely to voice social rather than economic motivations for sharing rides, and in some cases denied that ridesharing was a “job.” Based on interviews and observations, it seems possible that incidentals may form the largest single group of enrolled drivers. However, they provide rides only sporadically, which might account for their low representation in the sample. It appears likely that most rides are provided by full and part-time drivers.

Both part-timers and full-timers were more likely to voice economic motivations, and to consider ridesharing a job, equivalent to driving a taxi; several of those interviewed had, in fact, previously been employed as taxi drivers, or had considered such employment before taking the ridesharing job. Compared to incidentals, they were more likely to actively seek out fares, and to be willing to dead-head to reach passengers, thus performing the additive service of the traditional taxicab. Part-timers and full-timers were also more likely than incidentals to have experienced negative aspects of the occupation, such as rude or threatening passengers, or passengers who decline to contribute the “suggested” donation. Significantly, 45 % (9 of 20) drivers interviewed said that ridesharing was their sole or primary source of income.

The three companies differ in the freedom they afford drivers to pursue different strategies. Company A requires shifts, which makes incidental driving impossible; Company C requires advance ordering, which makes full-time driving difficult. Only Company B allows the full range of incidental, part-time, and full-time driving. Several drivers report using more than one app at a time in order to increase the chances for fares. Notably, 16 out of 20 drivers interviewed live outside of San Francisco, and bring their car into the city to drive for for-profit ridesharing services. Without claiming that this is statistically representative of ridesharing drivers as a whole, it nevertheless raises the concern that for-profit ridesharing could increase congestion by drawing drivers into the city, and increase VMT by drivers deadheading long distances to and from work.

Implications and further questions

Ultimately, the direct ecological impact of for-profit ridesharing depends on the strategies adopted by drivers, along this continuum from incidental, to part-time, to full-time driving. Further research is needed for a clearer picture of how representative these three types of driver strategies are, and what the true ratio of the three types may be within the overall population. Additionally, the proportions of drivers pursuing different strategies may change over time, for instance seasonally, or as the services come to be regulated. Yet some potential insight is afforded by the distinction made above between traditional cost-sharing ridesharing and taxi models. The cost-sharing built into traditional ridesharing is missing from for-profit ridesharing, the logic of which is better represented by the taxi model focused on I, the driver’s income. The for-profit business model does not directly determine driver strategies, but it does shape the constraints drivers face, and the range of motivations which will be rewarded by the job. The strategies adopted by drivers, in turn, lead to differing outcomes in terms of ecological efficiency.

The monetary incentive of for-profit ridesharing encourages a number of drivers to treat ridesharing as a job, equivalent to that of driving a taxi—driving long hours, giving rides with no common driver/passenger destination, and often commuting long distances to work. This further implies that these services may contribute to car use, rather than decreasing it as traditional ridesharing does, because of the empty or “deadhead” miles driven by drivers to pick up passengers. To this extent, these services are likely to be less ecologically efficient than traditional not-for-profit ridesharing.

There are indications that the role of income-focused full and part-time drivers is growing. Companies are increasingly seeking full and part-time drivers rather than incidentals, advertising for drivers on craigslist and similar sites with claims that drivers can make $20 to $35 dollars per hour; or enticing drivers to work through periods of low demand by reducing the company percentage taken, or by paying a base wage per hour.Footnote 16 In some cases multiple drivers take shifts to keep a ridesharing car in constant service (Johnson 2013). Full-day leases are available for cars to be used as ridesharing vehicles, in much the same manner as taxis are leased.Footnote 17 This is significant, because whereas incidental drivers are more likely to perform the trip-subtractive function of traditional ridesharing, part-time and full-time drivers are performing an additive service, much like traditional taxi drivers. The question then becomes which model—for-profit ridesharing or licensed taxis—performs this service more efficiently, with the least amount of additional miles driven.

In terms of reducing overal VMT, how ecologically efficient are these services compared to traditional taxis? The two key distinctions are (a) the greater flexibility of the on/off for-profit ridesharing vehicle, as opposed to the dedicated licensed taxi; and (b) the relative lack of regulatory oversight on vehicle standards and quantity. Increased flexibility in driver/vehicle supply could make this model more efficient than traditional taxis (in the traditional sense of occupied time as a percentage of overall time) by reducing driver downtime, since flexible drivers can simply go offline when business is slow. However, this flexibility is less evident the more hours drivers spend seeking fares, and may not necessarily be reflected in decreased VMT if offline drivers remain in their cars, in the city, waiting for the next period of demand. Several drivers reported using multiple ridesharing apps simultaneously, to increase their chances of fares during slow times; some have also claimed that they supplement slow hours, such as the breaks between rush hours, working as delivery drivers for similarly smartphone-enabled services. Furthermore, to the extent that drivers use the ridesharing income to support their own use of a private vehicle—or even to purchase a vehicle, as some do—for-profit ridesharing can serve as a prop for private automobility rather than a substitute for it. Such a criticism would apply far less to a dedicated taxi vehicle.Footnote 18 Thus, the increased flexibility of for-profit ridesharing may make it less efficient than dedicated taxi service at reducing VMT. This would be a key question for further research, or potentially for experimentation, for instance should regulators introduce some aspects of this flexibility into a licensed taxi model.

For-profit ridesharing could also prove less ecologically desirable than traditional licensed taxis by removing controls on the number of drivers and vehicles plying for hire. Like taxis, for-profit ridesharing drivers deadhead to pick up passengers; yet unlike taxis, which are typically restricted to a specific geographic jurisdiction, ridesharing drivers are free to bring their vehicles further in the search for work, as evidenced by the large portion of interviewed drivers who drove into San Francisco from other parts of the Bay Area. Further, the existence of for-profit ridesharing could erode the viability of existing regulations of the licensed taxi industry, potentially leading to loss of regulatory control over the number of licensed cabs, and over vehicle emissions standards. In San Francisco, for example, close to 100 % of the licensed taxi fleet is composed of recent-model “clean air” vehicles, thanks to a “Clean Taxi” program pushed by local regulators.Footnote 19 In contrast, the San Francisco Police Department estimated that of 100 for-profit ridesharing vehicles admonished for dropping passengers at the airport, only 17 % were clean air vehicles.Footnote 20 Not only do for-profit ridesharing companies in San Francisco impose less-stringent vehicle standards than do taxicab regulators, they have so far actively argued against the authority of regulators to expand such standards to ridesharing services (Dolan 2013), leading to the accusation that they are motivated by a neoliberal, pro-deregulatory agenda (Redmond 2012).

The future of for-profit ridesharing promises to be interesting. While this study was being conducted, these services were under cease-and-desist orders from the California Public Utilities Commission; at the time of this writing, the Commission has issued a ruling rejecting the argument that these services constitute “ridesharing,” while creating for them a new regulatory category of Transportation Network Company (TNC), in the stated interest of promoting innovation by shielding these services from the stricter local regulations governing taxis in many cities. The PUC adopted minimal requirements for insurance, driver training, and trade dress for TNCs, and plans to revisit these standards in one year for re-evaluation.Footnote 21 Despite the new terminology created by the PUC, these for-profit services continue to be referred to as “ridesharing” in media and popular discourse (e.g. Geron 2013), while others unequivocally refer to them as “cabs” or “taxis” (e.g. Bhatia 2013). In the meantime, the larger for-profit ridesharing companies have spread beyond San Francisco to many other US cities, while facing competition from smartphone-enabled limousine and taxicab dispatching services which are also scaling rapidly, as venture capitalists throw millions of dollars behind one company or another (Graham 2013). These new car services are already meeting a variety of regulatory responses in different municipalities, from crackdowns, to toleration, to official encouragement.Footnote 22 What happens next will take place against the backdrop of ideological conflict as progressive, conservative, and neoliberal visions compete over the future of automobility politics in US cities (Henderson 2013).

The questions of the legality of for-profit ridesharing services, or of what sort of regulation should or should not be applied to them, are beyond the scope of this paper. Here, a preliminary attempt was made at understanding how for-profit ridesharing compares to traditional taxi and ridesharing models, and at getting a sense of the range of motivations and strategies used by for-profit ridesharing drivers as they make use of the service. This makes possible a provisional account of the potential ecological impacts of the spread of this model of car service, based on the concept of taxicab efficiency, or the ratio of shared versus unshared (“dead-heading”) miles. The on/off flexibility of the for-profit ridesharing model has the potential to lead to either more or less efficiency compared to traditional dedicated taxicab vehicles, depending ultimately on the ratio of driving strategies (incidental, part-time, or full-time) adopted by drivers. At the same time, the deregulatory threat posed by the for-profit model of ridesharing could contribute to increased pollution and congestion through the erosion of regulatory controls on taxicab vehicle numbers and standards.

Notes

Underpaying, or not paying the donation, however, can result in a passenger being effectively barred from the service.

London-based Zingo, one of the first taxi e-hailing services, folded in 2004 (Bowers 2004).

In fact, taxicab companies in San Francisco and elsewhere make the same representation, classifying their drivers as independent contractors. For a detailed account, see Healy (2009).

Cf. comments by eRideShare before the Californa Public Utilities Commission, at http://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Efile/G000/M075/K768/75768710.PDF.

cf. King et al. (2012) on taxis.

This is a simplistic, generic model that could describe both owner-operators and leasing or commission drivers. Additional, non-mileage related costs could be considered as part of I. Income is “expected” because there is no guarantee of reaching I, regardless of P. Expected income affects the labor supply of taxi drivers (Crawford and Meng 2011), and low expectations have historically led to labor shortages (Hodges 2007).

Cost-sharing for additional passengers would call for a more complex model if the shared distance Q and deviation V are different for different passengers. See Agatz et al. (2010) for a more general cost-sharing model.

The author has encountered similar responses from taxi and limousine drivers in both San Francisco and Mexico City.

Of the three companies whose drivers were interviewed, one was unresponsive to requests for information; the other two declined to share data on drivers, rides, or passengers.

I.e., taking the liberty of converting my drivers’ diverse responses (e.g., Italian, Nicaraguan) into Hara’s categories (White, Latino). This is of course an imposition by the author but is done solely to enable comparison. Shaller’s study listed only three ethnic categories (White, Asian, and Black/African-American).

Since fieldwork was conducted, at least two additional companies have started providing smartphone-enabled for-profit ridesharing in San Francisco.

For comparison, the San Francisco cabdrivers interviewed by Burgel et al. (2012: 719) reported working between 10 and 84 h per week, with a median of 50 h.

All driver names are pseudonyms. Interview selections are taken from the author’s notes from verbal

interviews or from emails.

In other words, Salem possesses an “A-card,” required to drive a licensed taxi in San Francisco. The ridesharing companies do not require this license of their drivers.

See appendices to the comments by the San Francisco Cab Drivers’ Association before the California Public Utilities Commission at http://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Efile/G000/M071/K162/71162385.PDF; cf. also Kamzan (2013), Sharrock (2013).

See appendices to the comments by the Taxicab Paratransit Association of California before the California Public Utilities Commission at http://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Efile/G000/M079/K258/79258130.PDF.

The likelihood that a taxi will also serve as a private vehicle for the driver depends on the regulatory context and the taxi supply/demand ratio of the city. Cf. Kemp (1974: 86–7). In San Francisco, where most cabs are leased two full shifts per day, such use is necessarily limited.

cf. statements by the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency before the California Public Utilities Commission at http://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Efile/G000/M071/K162/71162385.PDF.

See the Decision issued by the California Public Utilities Commission on September 23, 2013 at http://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Published/G000/M077/K192/77192335.PDF.

Even within the same city: in Los Angeles, the mayor voiced public support for for-profit ridesharing, while the LA Department of Transportation has issued cease-and-desist notices to the companies involved (Maddaus 2013).

References

Adler, P.A., Adler, P.: The carpool: a socializing adjunct to the educational experience. Sociol. Educ. 57(4), 200–210 (1984)

Agatz, N., Erera, A., Savelsbergh. M., Wang, X.: Sustainable passenger transportation:dynamic ride-sharing. Erasmus Research Institute of Management. (2010) http://repub.eur.nl/res/pub/18429/ Accessed 5 September 2012

Anderson, D.N.: Playing for hire: discourse, knowledge, and strategies of cabdriving in San Francisco. Master’s Thesis, California State University, Hayward (2004)

Anderson, D.N.: The spy in the cab: the use and abuse of taxicab cameras in San Francisco. Surveill. Soc. 10(2), 150–166 (2012)

Arnott, R.: Taxi travel should be subsidized. J. Urban Econ. 40, 316–333 (1996)

Basmajian, C.: ‘Turn on the radio, bust out a song’’: the experience of driving to work. Transportation 37, 59–84 (2010)

Berry, K.: The last cowboy: the community and culture of halifax taxi drivers. Honors Thesis, Saint Mary’s University. (1995) http://www.taxi-l.org/cowboy.htm Accessed 28 August 2002

Bhatia, S.: Lyft: San Francisco’s colourful and controversial taxi firm. The Daily Telegraph (1 November 2013). (2013) http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/travelvideo/10404934/Lyft-San-Franciscos-colourful-and-controversial-taxi-firm.html Accessed 1 November 2013

Bowers, S.: Zingo goes for a song after cab service loses £4M. The guardian. (2004) http://www.theguardian.com/business/2004/nov/25/transportintheuk Accessed 10/15/2013

Burgel, J.B., Gillen, M., White, M.C.: Health and safety strategies of urban taxi drivers. J. Urban Health 89(4), 717–722 (2012)

Cantiello, A.P.: Strategic interaction among cabdrivers. Master’s Thesis, City University of New York. (1974)

Chan, N.D., Shaheen, S.A.: Ridesharing in North America: past, present, and future. Transp. Rev. 32(1), 93–112 (2012)

Clifton, KJ.: Mobility strategies and food shopping for low-income families: a case study. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 23, 402–413 (2004)

Cooper, J., Mundy, R., Nelson, J.: Taxi! Urban economies and the social and transport impacts of the taxicab. Ashgate, Burlington VT. (2010)

Crawford, V.P., Meng, J.: New York city cab drivers’ labor supply revisited: reference-dependent preferences with rational-expectations targets for hours and income. Am Econ Rev 101, 1912–1932 (2011)

Daus, M.: “Rogue” smartphone applications for taxicabs and limousines: innovation or unfair competition? Windels Marx Lane & Mittendorf. (2012). http://www.windelsmarx.com/resources/documents/Rogue%20Applications%20Memo%20(updated%208.6.12)%20(10777883).pdf Accessed August 30, 2012

Davis, R.A.: The taxicab business in San Francisco: a geographic analysis. Master’s Thesis, San Francisco State University. (1990)

Deakin, E., Frick, K.T., Shively, K.: Markets for dynamic ridesharing? The case of Berkeley, California. Transp. Res. Rec. 2187, 131–137 (2010)

Dolan, C.B.: Ridesharing safety standards non-existent. San Francisco Examiner (July 28, 2013). http://www.sfexaminer.com/sanfrancisco/rideshare-safety-standards-nonexistent/Content?oid=2514336 Accessed July 26, 2013

Douglas, G.W.: Price regulation and optimal service standards: the taxicab industry. J. Transp. Econ. Policy 6(2), 116–127 (1972)

Flores-Guri, D.: Local exclusive cruising regulation and efficiency in taxicab markets. J. Transp. Econ. Policy 39, 155–166 (2005)

Gamberini, L., Spagnolli, A., Miotto, A., Ferrari, E., Corradi, N., Furlan, S.: Passengers’ activities during short trips on the London Underground. Transportation 40, 251–268 (2013)

Geron, T.: California becomes first state to regulate ridesharing services. Forbes (19 September 2013) http://www.forbes.com/sites/tomiogeron/2013/09/19/california-becomes-first-state-to-regulate-ridesharing-services-lyft-sidecar-uberx/ Accessed 20 September 2013

Graham, J.: Taxi alternatives are on the move. Newsfactor (June 30, 2013) http://www.newsfactor.com/news/Taxi-Alternatives-Are-on-the-Move/story.xhtml?story_id=13000006UPMM Accessed July 27, 2013

Han, J.: Killing open taxi access a disservice to passengers—shields special interests of larger cab companies. San Francisco Sentinel. (8 June 2011) http://www.sanfranciscosentinel.com/?p=132338 Accessed 10 October 2013

Hara Associates: Taxi driver survey. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (2013). http://www.sfmta.com/about-sfmta/reports/hara-associates-draft-taxi-driver-survey. Accessed 15 September 2013

Healy, E.: In the Trenches With the Independent Contract. http://phantomcabdriverphites.blogspot.com/2009/07/in-trenches-with-independent-contract.html Accessed 5 May 2011

Heinrich, S.: Implementing real-time ridesharing in the San Francisco Bay Area. Master’s Thesis, San Jose State University. (2010)

Henderson, J.: Street Fight: The Politics of Mobility in San Francisco. University of Massachussets Press, Amherst (2013)

Hodges, G.R.G.: Taxi! A Social History of the New York City Cabdriver. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore (2007)

Johnson, C.: Rider’s Delight: How Two Lyft Drivers Bring the Party to the People. Shareable. (2013). http://www.shareable.net/blog/riders-delight-how-two-lyft-drivers-bring-the-party-to-the-people Accessed 18 October 2013

Kalanick ,T., Hempel, J.: Video and transcript: Uber CEO Travis Kalanick. CNNMoney. (2013). http://tech.fortune.cnn.com/2013/07/23/travis-kalanick-uber/ Accessed 24 July 2013

Kamzan, J.: Why taxi when you can sidecar? A new ridesharing app gives cabs a run for their money. Crosscut.com (March 11, 2013) http://crosscut.com/2013/03/11/transportation/113354/why-taxi-when-you-can-sidecar-new-ridesharing-app-/Accessed 15 March 2013

Katz, J.: How Emotions Work. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (2013)

Kemp, M.A.: Taxicab Service. In: Kirby, R.F., et al. (eds.) Paratransit Neglected Options for Urban Mobility, pp. 57–125. The Urban Institute, Washington DC (1974)

King, D.A., Peters, J.R., Daus, M.W.: Taxicabs for improved urban mobility: are we missing an opportunity? Proceedings of the 91st Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting. Washington, DC, USA. (2012). http://amonline.trb.org/1shm0t/1shm0t/1 Accessed 13 July 2013

Krohe, J.: Not your daddy’s taxi. Planning 79(5), 15–17 (2013)

Kusenbach, M.: Street phenomenology: the go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography 4(3), 455–485 (2003)

Latour, B.: Reassembling the Social. Oxford University Press, New York (2005)

Leonard, R.: Yellow Cab. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque (2006)

Maddaus, G.: Ride-sharing Apps Fight Back. LA Weekly (July 25, 2013) http://www.laweekly.com/2013-07-25/news/los-angeles-lyft-uber-taxi-sidecar/ Accessed 26 July 2013

Redmond, T. Cabs v. Lyft et al. isn’t just about tech. San Francisco Bay Guardian (November 19, 2012) http://www.sfbg.com/politics/2012/11/19/cabs-v-lyft-etal-isnt-just-about-tech Accessed 19 November 2012

Rheingold, H.: Smart mobs, The Next Social Revolution. Perseus Publishing, Cambridge MA (2002)

San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. SFMTA Strategic Plan: Fiscal Year 2013-2018. (2012). http://www.sfmta.com/cms/rstrategic/documents/1-3-12item12dfy13-18strategicplan.pdf. Accessed 5 October 2012

San Francisco Taxi Commission. Taxi driver survey. (2004). http://archives.sfmta.com/cms/rtaxi/documents/TaxiDriverSurvey-SummaryFindings4.pdf Accessed 10 October 2013

Schaller, B.: The changing face of taxi and limousine drivers. Schaller consulting, New York. (2004). http://www.schallerconsult.com/taxi/taxidriverreport.htm (accessed 3/1/2011)

Sharrock, J. Life behind the wheel in the new rideshare economy. BuzzFeed (May 8, 2013) http://www.buzzfeed.com/justinesharrock/life-behind-the-wheel-in-the-new-rideshare-economy Accessed 11 May 2013

Schlosberg, R.: Taxi driving: a study of occupational tension. Dissertation, City University of New York. (1980)

Solnit, R.: Diary: Google invades. London review of books. 35:34-35 (February 7, 2013) http://www.lrb.co.uk/v35/n03/rebecca-solnit/diary Accessed May 2, 2013

Toiskallio, K.: The impersonal Flâneur: navigation styles of social agents in Urban Traffic. Space Culture 5(2), 169–184 (2002)

Wiersig, D.W.: Estimating ridesharing levels for reduction in VMT. Transp. Res. Rec. 1018, 54–60 (1985)

Acknowledgments

An earlier, much simpler version of these arguments was presented as a poster at the 2013 Consumer Culture Theory Conference in Tucson, Arizona, June 14, 2013. My thanks go to the ridesharing drivers who shared their time and perspectives with me. Comments and criticisms from editor Mark Horner and from three anonymous reviewers greatly improved this article. Its remaining faults are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, D.N. “Not just a taxi”? For-profit ridesharing, driver strategies, and VMT. Transportation 41, 1099–1117 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-014-9531-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-014-9531-8