Abstract

Economic inequality in the U.S. is significantly influenced by the integration trajectory of diverse immigrant and racial/ethnic minority groups. It is also increasingly clear that these processes are uniquely gendered. Few studies, however, jointly and systematically consider the complex ways in which race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity intersect to shape minority men’s and women’s economic experiences, and an intersectional understanding of these processes remains underdeveloped. To address this gap, we blend insights from assimilation, stratification, and intersectionality literatures to analyze 2015–2019 American Community Survey data. Specifically, we examine income inequality and group-level mobility among full-time working whites, Blacks, Native Americans, and Asian and Latino subgroups representative of the Southwest—the first U.S. region to reach a majority-minority demographic profile. Sociodemographic and human capital attributes generally reduce group-level income deficits, and we observe a robust pattern of economic mobility among native-born generations. But most groups remain decisively disadvantaged. Persistent income gaps signal multitiered racial/ethnic-gender hierarchies in the Southwest and suggest exclusion of minority men and women. Additionally, race/ethnicity and gender have an uneven impact on the relative position and progress observed among both U.S.- and foreign-born generations. Such findings support an intersectional approach and demonstrate the complex interplay of multiple axes of inequality that together shape contemporary U.S.- and foreign-born men’s and women’s economic experiences and returns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

At the start of the twenty-first century, the U.S. has one of, if not, the highest level of income and wealth inequality among advanced industrialized nations (DeSilver, 2013; Smeeding, 2005). Numerous studies, in turn, have demonstrated that socioeconomic hierarchies in the U.S. cut across race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity status (Heathcote et al., 2010; Mandel & Semyonov, 2014; Villarreal & Tamborini, 2018). Specifically, there is strong evidence that racial/ethnic minorities, immigrants, and women tend to earn less than non-Latino whites, the native-born population, and men, respectively (Blau & Kahn, 2017; Duncan & Trejo, 2015; Painter, 2013). Most scholarly work in this area, however, focuses on one dimension of inequality (e.g., race/ethnicity or gender), ignoring complex webs of intersecting status hierarchies and axes of differentiation. Using rich, nationally representative data from the 2015–2019 American Community Survey (ACS), the present study examines inter- and intragroup income inequality in the American Southwest at the intersection of race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity.Footnote 1

Our focus on the Southwest is not trivial. The Southwest regional economy is the most dynamic in the country. According to multiple analysts (see, e.g., Doorn & Kelly, 2015; Greenwood, 2014; Millsap, 2016), the Southwest has consistently led the U.S. in GDP, job growth, and labor force participation. Additionally, the Southwest contains high concentrations of diverse racial/ethnic minority and immigrant populations, including Black, Native American, Asian, and Latino ethnics.Footnote 2 Roughly 20.2 percent of Southwest residents are foreign-born (well above the national average of 13.7 percent), and the population of the region is majority-minority (with 56.8 percent of residents nonwhite)—a demographic context anticipated for the nation as a whole by the middle of the twenty-first century.Footnote 3 Taken together, the Southwest offers a crucial case for studying group-level integration and stratification. On one hand, we may find evidence of racial/gender hierarchies, segmented assimilation, and downward mobility consistent with earlier studies (see, e.g., Greenman & Xie, 2008; Nawyn & Park, 2019; Restifo & Mykyta, 2019; Zhou et al., 2008). On the other hand, the Southwest may exhibit unique patterns that signal the path ahead and national future for many groups in the new economy.

Building upon prior scholarship, this study asks: (1) how economic incorporation, mobility, and inequality in the Southwest vary by race/ethnicity and nativity? and (2) to what extent such patterns (and potential processes) differ by gender? We add to the extant literature theoretically and empirically by examining how race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity effects interact to shape economic returns among full-time, full-year workers. Our contribution in this regard is twofold. First, from a theoretical standpoint, we bridge immigration, race/ethnicity, and intersectionality literatures to present a more nuanced picture than what is commonly found. Second, from an empirical standpoint, we utilize current ACS data, which allows us to deconstruct the monolithic view of major racial/ethnic groups (i.e., Asian and Latino) and perform intersectional comparative analyses of economic standing among diverse groups of U.S.- and foreign-born men and women. Recognizing the multigroup and hierarchical character of U.S. racial/ethnic relations and experiences, we include ten racial/ethnic groups in our analyses: non-Latino whites, Blacks, and Native Americans, as well as Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Guatemalan, Mexican, and Salvadoran ethnics—groups representative of the labor force in the Southwest. To our knowledge, no single study considers these groups in substantive depth together (relative to race, gender, and immigrant status) or applies such an approach to investigate complex systems of socioeconomic inequality in the Southwest.

Contemporary Immigration and Racial/Ethnic Stratification

Immigrant adaptation literature calls attention to the distinctiveness of immigrants relative to the dominant society and highlights two interrelated elements: sociocultural change and structural incorporation. Classical assimilation theory and its straight-line variants suggest social and cultural adaptation in successive immigrant generations is archetypal, leading to structural integration into (and mobility within) core institutions—though with the notable exception of African Americans (Glazer, 1971; Gordon, 1964; Lieberson, 1980).Footnote 4 This is supported by the remarkable incorporation and economic mobility demonstrated by diverse—yet predominantly white—European immigrant groups that arrived in the U.S. at the turn of the twentieth century. Since 1965, however, most immigrants have been racial/ethnic minorities entering a racially stratified class system (Feliciano, 2006; Jiménez, 2008; Portes & Rumbaut, 2014). Moreover, they are met in the U.S. with an information-based economy that does not offer the same job prospects or opportunity structure that the now narrowed (and generally declining) manufacturing economy once did. Not surprisingly, classical assimilation theory runs into difficulty as the uneven incorporation of diverse post-1965 immigrants into mainstream institutions and society becomes more evident (Feliciano, 2006; Portes & Zhou, 1993; Sakamoto et al., 2009).

Segmented assimilation theory moves past assumptions of a single path to incorporation and suggests multiple paths may lead to varying degrees of adaptation and integration into different segments of society (Haller et al., 2011; Portes & Rivas, 2011; Portes & Rumbaut, 2001, 2014). Crucially, this framework calls direct attention to the link between racial/ethnic status, context of reception, and mode of incorporation (Portes & Rumbaut, 2014; Portes & Zhou, 1993). The context of reception presents a set of opportunity structures in the host society that afford immigrants social and economic mobility. In many respects, this is a function of the racialized assumptions of who belongs in the U.S. and how dominant white society makes sense of where immigrant and minority groups fit into the existing status order. In the U.S., race has been and still is one, if not the most, important predictor of life chances, and, by implication, dimension of socioeconomic stratification (Gans, 2005; Omi & Winant, 2015).

Multiple scholars contend that the historically dominant binary racial classification (white-nonwhite) scheme has become obsolete due to the growing share of Asians and Latinos among U.S. immigrants in the post-Civil Rights era (e.g.,Frank et al., 2010; Lee & Bean, 2007; Marrow, 2009; Masouk & Junn, 2013). In particular, contemporary race theory points to a multitiered status hierarchy in which whites are found at the top, followed by Asians, with Blacks and Latinos most frequently disadvantaged and positioned at the bottom—a pattern reflected in economic opportunities and returns (e.g., Adelman & Tsao, 2016; Kmec, 2003; Painter & Qian, 2016; Stewart & Dixon, 2010). Taken a step further, Bonilla-Silva (2004) suggests contemporary U.S. racial/ethnic relations and inequality can be understood as a triracial system comprised of whites, honorary whites, and the collective black. Here, he designates such groups as Asian Indian, Chinese, and Filipino ethnics as honorary whites, and others such as Mexican, Salvadoran, and Vietnamese ethnics as collective black. Bonilla-Silva (2004) also suggests Native Americans, specifically those in urban areas, fit into the white stratum. This view, however, sits in contrast with historical and durable Native American disadvantage, which intimates Native Americans as internally colonized nations fall into the collective black—though few recent studies consider Native American socioeconomic integration and inequality (Davis et al., 2016; Glick & Han, 2015; Huyser et al., 2010; see also Roscigno et al., 2015).

The context of reception and related status hierarchies are of course multidimensional and closely connected to the mode of immigrant/minority incorporation. Rumbaut (2008) describes the mode of incorporation as a function of two interrelated factors: (1) legal status at entry (as a refugee or voluntary immigrant); and (2) human capital prior to arrival. While most immigrants move to the United States to improve their socioeconomic well-being, refugees are typically displaced by civil conflict or natural disasters. Unlike other immigrants, refugees are those whose decision to move is influenced by non-economic factors concerning survival, safety, freedom, etc. Because they are “pushed” rather than “pulled,” refugees are often negatively selected on human capital (Borjas, 1989; Feliciano, 2006; Portes & Rumbaut, 2014). Moreover, compared to other immigrants, refugees are more likely to have had traumatic experiences and are likely to struggle with their adjustment (Kim, 2002; Potocky-Tripodi, 2003; Yun et al., 2012). Not surprisingly, they tend to lag behind other immigrants in the labor market and economy—i.e., they have lower earnings and higher rates of unemployment than voluntary migrants, all else being equal (Chiswick et al., 2005; Connor, 2010; De Vroome & Van Tubergen, 2010).

Segmented assimilation theory sheds important light in these regards on the dynamic and complex role of race/ethnicity and national origin, offering a nuanced lens through which to understand inter- and intragroup differences. Some minority groups may thus experience downward socioeconomic mobility from immigrant to U.S.-born generations, while others catch up to and, occasionally, even surpass non-Latino whites (Portes & Rumbaut, 2014). Still, segmented assimilation discourses seldom consider how gender might filter patterns of socioeconomic integration, mobility, and inequality in substantive depth. This is striking given women represent nearly half the U.S. immigrant population and many migrate specifically to secure work (Blau et al., 2003; Kanaiaupuni, 2000; López and Radford, 2017).

Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Intersectionality

The predominant view among contemporary stratification theorists is that race/ethnicity and gender are key status dimensions based on systems of power and deference (Bennett et al., 2009; Dumais, 2002). Such characteristics reflect cultural and social capital assets. And as Bourdieu (1986) contends, cultural and social capital can be transferred to some extent between different contexts and transformed into economic capital. Consequently, race/ethnicity and gender constitute social boundaries whose distinctions are embedded in a variety of social, economic, and cultural contexts. That is, they represent hierarchical socioeconomic categories since they provide mechanisms for exclusion (Bennett et al., 2009; Neckerman & Torche, 2007). For instance, whites exclude racial/ethnic minorities and men exclude women from high-status positions in order to preserve their monopoly over institutional power and privilege (Elliott & Smith, 2001, 2004; Roscigno, 2007).

Particularly relevant here, despite the recent dramatic increase in educational levels among working age women, gender pay gaps persist, ceteris paribus (Blau & Kahn, 2017). American female workers are affected by social closure in their careers through various forms of workplace gender segregation and discrimination (Castaño et al., 2019; Reskin, 2018). These gender inequities are compounded by the still-lower labor participation of women compared to men (England et al., 2020). Dominant group closure and exclusionary practices thus manifest in differential job placement and financial returns by both race/ethnicity and gender. This of course also ties into immigration and the immigrant experience.

Most immigrants to the U.S. are racial/ethnic minorities and women (Budiman et al., 2020; Curran et al., 2006), and their integration is both racialized and gendered. One way to explain racial/ethnic- and gender-based inequalities among the U.S.- and foreign-born is through the lens of intersectionality. Unlike the literature discussed above, intersectionality defies one-dimensional stratification frameworks that prioritize (if not essentialize) race/ethnicity, gender, nativity status, and other qualities. Such narrow foci and approaches are deemed insufficient for grasping the complexity of contemporary life events and experiences (Collins, 1990; Davis, 2008; Nash, 2008). Indeed, intersectionality scholars have shown that race/ethnicity interacts with gender in dynamic ways that move beyond what might be expected relative to the additive effects of each status dimension of inequality (Blea, 1992; Glenn, 1999; McCall, 2005; Yuval-Davis, 2006). Prior research, for example, suggests racial/ethnic minorities’ financial standing is lower than Anglo whites’, women’s is lower than men’s, and immigrants’ is lower than the native born. But such binaries are overly reductive. Race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity jointly and simultaneously produce disparities that cannot be easily predicted or deduced by simply adding disadvantages and combining effects.

To this end, intersectional work prioritizes the complexity of multiple interconnected axes of privilege and subordination. Stone et al. (2006), for instance, highlight the convergence of race/ethnicity, gender, and education for explaining earnings inequality among Asian ethnics and between women. Moreover, among U.S.- and foreign-born Asian ethnic women, their findings challenge Asian “model minority” stereotypes and reveal meaningful ethnic-specific differences in pattern and process. Valdez and Tran (2020) find a mixed picture as well. Focusing on Latino groups, their analyses suggest second-generation Latina women are generally advantaged in occupational and educational attainment compared to co-ethnic men, while also capturing important differentials tied to human capital and national/ethnic origin. Borch and Corra (2010), in turn, find a sizable earnings gap between Black and white African immigrants. They determine that human capital greatly reduces the gap between Black and white African women’s earnings—but not the gap between men’s earnings. However, men earn more than women regardless of race and despite a stronger race penalty. Nawyn & colleagues draw similar conclusions in their work on U.S.- and African-born Black and white men and women and offer several extensions, including documenting gender-specific segmented assimilation—i.e., among Black men but not women (Nawyn & Gjokaj, 2014; Nawyn & Park, 2019).

Unfortunately, research of this sort is the exception not the rule (see also De Jong & Madamba, 2001; Park et al., 2015; Restifo & Mykyta, 2019). Few studies systematically consider how race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity together might shape labor market and economic outcomes.

Research Hypotheses

Blending insights from assimilation, stratification, and intersectionality perspectives, we build on calls for intersectional approaches to understanding socioeconomic inequality and mobility (see, e.g., Greenman & Xie, 2008; McCall, 2005; Nawyn & Park, 2019; Restifo & Mykyta, 2019). In the context of the American Southwest, we compare multiple race/ethnic/gender groups and offer several hypotheses in these regards. We begin with our most general prediction concerning race/ethnicity and the context of reception.

Hypothesis 1

Reflecting fundamental U.S. racial/ethnic relations and underlying status hierarchies, whites will be positioned at the top of economic arrangements in the region, followed by Asians, with Blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans most severely disadvantaged (Huyser et al., 2010; Masouk & Junn, 2013; Painter & Qian, 2016; Portes & Rumbaut, 2014).

Drawing from and extending upon race/ethnic stratification and immigration literatures, we provide several important caveats pertaining to inter- and intragroup variation to this initial prediction.

Hypothesis 2

Economic returns for honorary whites (Asian Indians, Chinese, and Filipinos) and Native Americans in the Southwest will more closely align with those of whites, whereas returns for the collective black (Mexicans, Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and Vietnamese) will more closely align with those of African Americans (Bonilla-Silva, 2004).

Hypothesis 3

Group mobility will be positive from foreign-born to native-born generations among honorary whites, but not the collective black. That is, Asian Indian, Chinese, and Filipino ethnics will secure upward economic mobility, whereas Black, Latino, and Vietnamese ethnics will experience stagnant or even downward mobility (Bonilla-Silva, 2004; Portes & Rumbaut, 2014).

In addition to the context of reception, we consider the mode of incorporation. Here, we devote particular attention to the role of refugee status. Prior work suggests coming to the U.S. as a refugee adversely affects socioeconomic integration and mobility prospects (Rumbaut, 2008). Moreover, we know from the literature that the share of individuals who arrive in the U.S. as refugees is much higher among some Asian and Latino groups (Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and Vietnamese) than among others (Asian Indians, Chinese, Filipinos, and Mexicans) (Bloemraad, 2006; Bloemraad et al., 2008; Portes & Rumbaut, 2014). This leads to our next hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4

Asian and Latino ethnic groups that come to the U.S. primarily as refugees (Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and Vietnamese) will have lower economic returns than Asian and Latino ethnic groups that arrive primarily as voluntary migrants (Asian Indians, Chinese, Filipinos, and Mexicans).

The predictions we have outlined up to this point provide important guideposts to sort out complex race/ethnic-nativity differences. What remains less clear, however, is: (1) how such predictions might vary relative to gender; and (2) how race/ethnicity and nativity status intersect with gender to shape patterns of group incorporation, mobility, and inequality. At a basic level, most evidence suggests women earn less than men and are disadvantaged in the labor market and the economy at large (England et al., 2020; Kim & Carter, 2016). Enduring gender income gaps are rooted in complex gender dynamics that remain the subject of active research, ranging from differences in human capital, familial gender roles, employment practices, and outright discrimination (Blau & Kahn, 2017).

At the same time, gender gaps continue to evolve. American women now earn more college degrees across all major racial groups than their male counterparts, while also earning better grades and maintaining higher GPAs (DiPrete & Buchmann, 2013). But the promise of women’s relative advantage in academic performance is dampened upon entry into the skilled-labor market because gender stereotyping may cause actual academic achievement to be evaluated unevenly and in favor of male college graduates (Quadlin, 2018). Additionally, late entry into the labor market, early exits, and periods of intermittent employment have a cumulative effect on gender pay gaps, affecting women’s relative wage attainment as they progress in their careers in labor segments where they tend to be more concentrated (Weisshaar & Cabello-Hutt, 2020). Nevertheless, in some lines of work men experience higher wage penalties than women for work lapses, a disadvantage that may be attributable to a male breadwinner/female caretaker gendered norm dichotomy that persists in the U.S. workplace (Weisshaar, 2018).

Overall, the evidence is quite mixed with regards to the applicability of Hypotheses 1–4 to women. Indeed, recent research denotes that race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity intersect in the labor market and economy to produce complex and unique outcomes. Chapman & Benis (2017), for instance, find a larger gender wage gap among Latina women (relative to co-ethnic men) than white and black women. Greenman and Xie (2008), in turn, report a larger deficit among white women (relative to white men) than Asian, Black, and Latina women to co-ethnic men. Restifo and Mykyta (2019) identify markedly distinct racial/ethnic wage hierarchies for men and women. They also find evidence of upward mobility among some Asian, Black, and Latino American groups, while others show signs of stagnant and downward economic mobility that vary by gender. Valdez (2006) similarly highlights the convergence of gender and nativity in shaping segmented earnings outcomes. Estimates here show a shortfall among Mexican American women (relative to co-ethnic immigrant women), whereas U.S.- and foreign-born Mexican men tend to fair better. Nawyn and Park (2019) meanwhile observe a gender-specific racial/immigrant disadvantage suggestive of segmented assimilation among Black African men (relative to white African and U.S.-born Black men). Among Black African women, however, a racial/immigrant earnings disadvantage is not observed. Taken together, intersectional scholarship points to a picture that is far from complete. The foregoing discussion leads to our final two hypotheses.

Hypothesis 5

Women in the Southwest will have lower economic returns than men in general and co-ethnic men in particular.

Hypothesis 6

We expect to find significant variation between, and joint effects of, race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity on economic returns and mobility. Given the convergence of multiple axes of differentiation, however, we do not make specific directional predictions (Browne & Misra, 2003; Glenn, 1999; McCall, 2005; Yuval-Davis, 2006).

Data and Methods

Data and Sample

To test the above hypotheses and explore potential inter- and intragroup differences in economic incorporation, mobility, and inequality, data are drawn from the 2015–2019 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year sample (Ruggles et al., 2021). Data are based on respondent self-reporting and provide a 5-in-100 random sample of the U.S. population. We restrict the sample to adults ages 25 to 55 living in the Southwest (AZ, CA, CO, NV, NM, TX, UT) and apply individual-level sample weights to obtain representative estimates. We target adults ages 25 to 55 because this corresponds to the foremost period of workforce participation. We also restrict the sample to full-time, full-year workers. Full-time, full-year workers are persons who worked 35 or more hours per week for 48 or more weeks the previous year.Footnote 5 This includes self-employed individuals (i.e., business owners and employers), as well as public and private sector employees (i.e., individuals working for another person or entity for wages or salary). Full-time, full-year workers represent persons integrated into the labor market that we might assume have secured more or less equal competitive opportunity (Restifo & Mykyta, 2019).Footnote 6 Thus, we consider patterns and processes of stratification and mobility among those that have secured a regular place in the workforce and presence in the economy.

Our focus on the Southwest is equally important. Once part of the Spanish Empire and later Mexico, the region has a shared social, economic, and political-legal history. This history is linked to diverse indigenous (Native American and Mexican-origin) populations, as well as restrictive government legislation, action, and surveillance (including forced relocation and mass deportation) spanning the southern border from California to Texas north to Colorado and Utah (Hall, 1989; Obinna, 2018). At present, the Southwest economy leads the nation in the transition to an information-based economy (Doorn & Kelly, 2015; Greenwood, 2014). Moreover, the region is majority-minority and offers a valuable (though often overlooked) site to study the socioeconomic integration of underinvestigated domestic groups, such as Native Americans, and fast-growing immigrant groups, especially Central Americans and Southeast Asians, that are relatively underrepresented in other regions of the country.

The Southwest, of course, is also internally diverse and heterogenous across localities. Indeed, the region includes such cities as Boulder, CO, El Paso, TX, Phoenix, AZ, Provo, Utah, and San Francisco, CA, to name a few. In total, the region encompasses 65 Census-identified metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). These large urban areas, which include a principal city and surrounding communities, have populations of at least 50,000 inhabitants and represent the local labor markets where a vast majority of the region’s population live and work (Ruggles et al., 2021). Specifically in our case, 90% of full-time, full-year workers in the 2015–2019 ACS ages 25–55 in the Southwest live in these 65 MSAs.Footnote 7 Such comprehensive and inclusive data bolsters our confidence in the veracity and representativeness of it for the groups we consider and the Southwest region overall. We limit our sample to these areas and account for them in our analyses (see discussion of statistical controls below).

Our analyses center on ten racial/ethnic groups. This includes non-Latino whites, Blacks, and Native Americans, as well as Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Mexican, Guatemalan, and Salvadoran ethnics.Footnote 8 Each group represents a mutually exclusive racial/ethnic classification and category.Footnote 9 Given this focus (and related restrictions), our analytic sample consists of 774,646 men and women. Importantly, the ten racial/ethnic groups we analyze provide a broad cross-section of populations that reflect quite well the diversity found in Southwestern labor markets. In addition, our inclusion of these groups provides leverage useful toward disentangling complex dynamics and outcomes—dynamics and outcomes obscured by analyses examining just a handful of racial/ethnic groups and those utilizing pan-ethnic classification schemes (e.g., Asian and Latino) (for a detailed discussion see DiPietro & Bursik, 2012).

Dependent Variable

Total personal income is our primary outcome of interest. This measure reflects the total pre-tax personal income (including losses) of respondents from all sources during the previous 12 months and is key for assessing financial achievement and inequalities. All values are inflation-adjusted to 2019 dollars and we log-transform total income in our analytic models to correct for the positive skew of the data. In addition, to obtain positive logged values for all cases, including persons with negative total incomes, we add the absolute value (plus one) of the largest income deficit in the sample to the total income of every respondent. This strategy allows us to take into account full-time, full-year workers experiencing financial shortfalls and fully maximize our sample (for a detailed explanation, see Painter & Qian, 2016).

Independent Variables

Race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity are central to our analyses and serve as core predictors for modeling income. We include each racial/ethnic group noted above and draw a distinction between foreign-born (i.e., first-generation immigrants) and U.S.-born respondents (i.e., second generation or higher).Footnote 10 Simultaneous consideration of race/ethnicity and nativity—as well as comparison of divergent outcomes among and between the foreign- and native-born—can shed valuable light on group-specific assimilation and inequality processes. Likewise, acknowledging the unique challenges and experiences that confront men and women in the economy, we analyze each group by gender and introduce a series of interaction terms in later models to capture the potential multiplicative effects of race/ethnicity (stratified by nativity) and gender on income.

We also include a number of measures associated with immigrant adaptation and human capital. These are U.S. citizenship, English language proficiency, and education (Alba & Nee, 2003; McCall, 2001; Valdez, 2006). U.S. citizenship is captured using dichotomous measures for U.S.-born citizen, naturalized citizen, and non-citizen.Footnote 11 English language proficiency is coded 1 if a respondent speaks English well and 0 otherwise. Education is gauged using a set of binary indicators for less than high school education, high school diploma (or equivalent), some college, bachelor’s degree, and post-graduate degree.Footnote 12

Relatedly, we take into account work experience, class of worker, hours worked, and occupation in our modeling. Such factors are commonly linked to socioeconomic attainment and mobility (McCall, 2001; Wilson, 1997, 2009). Work experience is calculated as age minus years of schooling minus six (see Borch & Corra, 2010; Greenman & Xie, 2008; VanHeuvelen, 2018).Footnote 13 We also include a squared term since the effect of work experience may be nonlinear. Class of worker is captured using dichotomous measures for self-employed status, public sector employment, and private sector employment. Self-employed includes business owners, entrepreneurs, and employers; public sector denotes local, state, and federal government employees; and private sector denotes for-profit company and nonprofit organization employees.Footnote 14 Hours worked is a continuous measure representing the usual number of hours worked per week. We construct a series of binary indicators for the 24 occupational categories identified by the U.S. Census Bureau—excluding military service (see Stewart & Dixon, 2010).

We introduce several measures of family and household structure as well. Specifically, we control for marital status, household family membership, and number of own children in household—measures associated with social capital and economic status (Nee & Sanders, 2001; Tolnay, 2004). Marital status is dichotomous, coded 1 if an individual is married and 0 if never married, widowed, separated, or divorced. Household family membership is coded 1 if a respondent lives in a household with extended family members and 0 otherwise.Footnote 15 Number of own children is a continuous measure that reflects the number of biological, step, and adopted children living with the respondent. Lastly, we include dichotomous measures for each MSA to standardize for local metropolitan context. Table 1 reports summary statistics for dependent and independent variables by race/ethnicity and gender.

Analytic Strategy

Our analyses proceed in two steps. First, we use ordinary least squares regression to estimate racial/ethnic- and gender-specific differences in logged total income (Table 2). Model 1 serves as a baseline for examining potential income gaps and group hierarchies, holding MSA constant. Model 2 introduces assimilative and human capital attributes, including nativity, citizenship, education, and work experience. Model 3 incorporates class of worker, hours worked, occupation, family, and household controls. Comparison of Models 1 through 3 highlights and contextualizes racial/ethnic and gender income inequalities and hierarchical arrangements.

To estimate logged total income (shown in Table 2), we used the following equation:

where β0 is the intercept, β1 is the vector of racial/ethnic-gender groups (X1), β2 denotes assimilation and human capital predictors (X2), β3 denotes remaining individual background predictors (X3), β4 represents MSA controls (X4) (not shown for parsimony), and τ is the error term.

The second step of our analyses distinguishes each racial/ethnic group by nativity, allowing us to assess differences in total income between immigrants and their U.S.-born co-ethnic peers (Table 3). We estimate separate regression models, in this instance, for men and women. We also estimate a single pooled model where we introduce interaction terms for covariates by gender (t for M-W).Footnote 16 Such an approach allows us to: (1) assess the impact of race/ethnicity, nativity, and other predictors on total income; and (2) draw direct comparisons between men and women. Thus, we are able to more fully engage and explore patterns and dynamics at the intersection of race/ethnicity, nativity, and gender.

To estimate logged total income separately for men and women (shown in Table 3), we used the following equation:

where β0 is the intercept, β1 is the vector of racial/ethnic-nativity groups (X1), β2 denotes assimilation and human capital predictors (X2), β3 denotes remaining individual background predictors (X3), β4 represents MSA controls (X4) (not shown for parsimony), and τ is the error term.

To specify significant differences by gender across models for men and women in Table 3 (t for M-W), we used the following equation introducing interaction terms for covariates by gender (utilizing the full analytic sample):

where β0 is the intercept, β1 denotes covariates (X1), β2 denotes gender (X2), β3 represents covariate by gender interaction terms (X1X2), β4 represents MSA controls (X4) (not shown for parsimony), and τ is the error term.

Descriptive Findings

Table 1 reports median total personal income and explanatory variable means for full-time, full-year workers by race/ethnicity and gender. Among men in the Southwest, median income ranges from $30,544 (Guatemalan men) to $112,227 (Asian Indian men). White men earn more than most groups (with the exception of Asian Indian and Chinese men), and Asian men outpace their Black, Latino, and Native American counterparts. Strikingly, Latino men trail all other full-time working men, including Black and Native American men. Consistent with expectations, we also find substantial income differences within broader pan-ethnic groupings (i.e., Asian and Latino). Asian Indian men, for example, gross $57,249 more than Vietnamese men, while Mexican men earn $8,951 more than Guatemalan men.

Among women in the Southwest, median total personal income ranges from $29,202 (Guatemalan women) to $86,550 (Asian Indian women). Similar to men, Asian women have higher median incomes than all other minority women (with Asian Indian and Chinese women also exceeding white women), and Latina women exhibit the lowest totals overall. Once again, considerable variation is evidenced within broader race/ethnic categories. Asian Indian women, for instance, gross $40,735 more than Vietnamese women, while Mexican women earn $4,172 more than Guatemalan women. Additionally, we see significant income inequalities within and across race/ethnicity by gender. Findings demonstrate that the median income for most groups of women working full-time falls well below that of male co-ethnics—a pattern consistent with regression estimates discussed below. But nearly all non-Latina women (i.e., white, Black, Asian, Native American) earn more than Latino men.

Table 1 provides additional sample characteristics by race/ethnicity and gender. Notably, U.S. citizenship in the Southwest is lowest among Asian Indian, Guatemalan, and Salvadoran men—three groups overwhelmingly comprised of immigrants. Vietnamese men, nonetheless, although also predominantly foreign-born, show especially high rates of citizenship. By the same token, Chinese, Filipino, and Vietnamese men are more likely to be U.S. citizens than Latino men, and a larger share of Asian men speak English well compared to Latino men. Educational attainment is highly stratified as well. For example, about 10 percent of Latino men and 21 percent of Native American men hold a college or graduate degree. In contrast, about half of white and Filipino men, 73 percent of Chinese men, and 89 percent of Asian Indian men have completed college. At least in part reflecting high levels of educational attainment, Asian Indian men have the highest income and fewest years of work experience among full-time working men.

In many ways, men’s and women’s background characteristics parallel one another in our sample. Yet several gender-based differences are immediately discernable. Latina women, for instance, are more likely to be U.S.-born and U.S. citizens than co-ethnic men. They also generally have higher college graduation rates than their male counterparts. Latina women, however, like Latino men, show lower levels of citizenship, English proficiency, and educational attainment relative to most other groups. Further, we find that for most racial/ethnic groups, women working full-time are less likely to be married than co-ethnic men—with more pronounced gaps observed among whites, Blacks, Native Americans, and Latino ethnics. Although a large proportion of Asian women are married (62–79%), a majority of Black, Native American, and Latina women are not (51–66%).

Regression Results

Table 2 reports regression estimates of logged total income for full-time, full-year workers in the Southwest. For ease of interpretation, logged income estimates for each race/ethnic-gender group are converted to a proportion (p) by calculating the antilog of each unstandardized coefficient. Each value, in turn, represents the proportion of average total income earned by a given group relative to the reference category (white men). This strategy allows us to more effectively discuss group-specific income estimates and inequalities.

Model 1 denotes racial/ethnic and gender disparities, calling immediate attention to group hierarchies.Footnote 17 Here, all but one group, Asian Indian men, display significantly lower income levels than white men. Income gaps range from 0.47 for Guatemalan men to 0.91 for Chinese men, and from 0.45 for Guatemalan and Salvadoran women to 0.96 for Asian Indian women (relative to white men). Findings in this instance suggest a multitiered racial/ethnic income hierarchy among full-time working men and full-time working women in which whites and Asian Indians are positioned at the top, Chinese ethnics follow, Blacks, Filipinos, Native Americans, and Vietnamese are in the middle, and Latino groups (Guatemalans, Mexicans, Salvadorans) are at the bottom.

In addition, our estimates underscore the fundamentally depressed character of women’s income relative to men’s. Women across most groups in our sample have substantially lower income levels than their co-ethnic male counterparts. Noticeably, though, Asian Indian women exhibit higher earnings than all groups but white and Asian Indian men, and most non-Latina women exhibit higher earnings than Latino men.

Model 2 introduces assimilative and human capital attributes. For multiple groups, Latinos in particular, the income gap is reduced considerably. Guatemalan men’s income ratio, for example, increased from 0.47 to 0.74, and Salvadoran men’s increased from 0.53 to 0.79. Similarly, both Guatemalan and Salvadoran women’s ratios increased from 0.45 to 0.64 (relative to white men). Consistent with prior scholarship, our findings point to the salience of nativity, citizenship, language proficiency, education, and experience, highlighting how such factors can mitigate some race/ethnic- and gender-based inequalities. Distinctly, however, Asian Indian men and women see a dip in income across models. This is likely at least in part a function of overqualification wherein advanced educational credentials do not match jobs or compensation (Lu & Huo, 2020; Lu & Li, 2021).

Model 3 incorporates remaining work and household controls. For most racial/ethnic groups the income gap for both full-time working men and women is again reduced. A majority of minority men’s income ratios now reach 0.85 and a majority of women’s ratios reach 0.75 (relative to white men). Even so, apart from Asian Indian men, significant income deficits persist for all groups compared to white men. What’s more, group-specific deficits cluster somewhat by gender and sensitivity tests signal significant income gaps between co-ethnic men and women.

Importantly, Model 3 estimates suggest variable, if not unique, race/ethnic-gender income hierarchies. Among men in the Southwest, whites and Asian Indians display the highest earnings, followed by Chinese ethnics (0.92), then Mexican, Native American, Salvadoran, and Vietnamese ethnics (0.85–0.87), and finally Black, Filipino, and Guatemalan men (0.81). Among women in the Southwest, earnings appear split between whites and nonwhites, with white and honorary white (Asian Indian, Chinese) ratios at or above 0.82 and comparing favorably to collective black and Latina ratios (0.74–0.77) as well as several groups predicted to be in the white stratum (Filipina, Native American [0.75–0.76]). Still, white, Asian Indian, and Chinese women’s income estimates approximate those of only the most disadvantaged men in our sample—namely, Black, Filipino, and Guatemalan men.

Table 3 reports coefficients and proportions from OLS regression models predicting the logged total income of full-time working men and women by race/ethnicity and immigrant status as well as interaction terms by group and gender (t for M-W). All models include our full complement of explanatory measures and statistical controls. White native-born men and white native-born women serve as referents in models estimated for men and women, respectively. White native-born men serve as the referent in the single pooled model used to estimate interactions.

Table 3 shows that among minority men and among all women, income ratios are higher among U.S.-born ethnics compared to their foreign-born peers. For example, Chinese American men’s income (0.95) outpaces that of foreign-born Chinese men (0.89), while Mexican American men’s position (0.88) tops that of foreign-born Mexican men (0.85). We find a similar pattern across the board among women in our sample. Such findings suggest positive group-level incorporation and economic mobility for most full-time working U.S.-born ethnics relative to the immigrant generation in the Southwest context. We do not, however, find evidence of downward mobility among the collective black (Blacks, Latinos, Vietnamese) as hypothesized—though we find signs of sluggish if not stagnant mobility among Salvadoran men and Guatemalan and Salvadoran women. Although these are not direct measures of intergenerational or longitudinal adaptation, such results suggest native-born workers across widely different groups show a trend towards greater labor force integration and improved economic opportunities—a trend consistent with more classic assimilation arguments. This, of course, may partially reflect and be a function of the low financial starting point of workers born abroad across many groups (e.g., foreign-born Black and Filipino men).

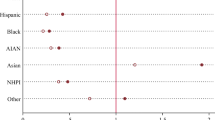

Figure 1 helps further illustrate race/ethnic-nativity mobility by gender and contextualize income ratio differentials. Crucially, significant gaps persist for most racial/ethnic minorities regardless of nativity, even after controlling for human capital and family configuration measures. Among men in the Southwest, income levels generally fall below 0.90 (relative to white native-born men) for both U.S.- and foreign-born ethnics—with the exception of U.S.- and foreign-born Asian Indians, U.S.-born Chinese, and foreign-born whites. Here, our findings point to an income hierarchy wherein white and Asian Indian men demonstrate the highest returns, followed by Chinese men, with collective black, Latino, and Native American men most strikingly disadvantaged. Historically, white men have been privileged as immigrants in the U.S. and even today they are beneficiaries of benign reception due to the continued preference for white workers in the U.S. labor force and selectivity in the foreign worker recruitment process. Likewise, some recent Asian immigrant cohorts have arrived under a relatively positive context of reception. Asian Indian men, for instance, typically selected from the high end of the income and educational distribution in their home country, may benefit from a “halo” effect emanating from ethnic social capital embedded in strong, socioeconomically stable communities (Lueck, 2018).

Proportion of Logged Total Income for Race/Ethnicity & Nativity by Gender for Full-Time, Full-Year Workers, ACS 2015–2019. Estimates are based on a single pooled model utilizing the full analytic sample. Proportions reflect the antilog of the unstandardized coefficient for each group. U.S.-born white men serve as the overall reference group. Full results and estimates from this model are available upon request. Sensitivity tests capture significant differences between U.S.- and foreign-born co-ethnics. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Chinese men may similarly benefit from model minority generalizations stemming from the successful integration of prior cohorts—despite the arrival of recent immigrants from poorer regions (Portes & Rumbaut, 2014; Zhou et al., 2008). This does not, however, appear to be the case for most full-time, full-year workers. Foreign-born Black men, for example, exhibit the lowest income shares (0.72) among men in the Southwest (relative to white men). Our estimates also suggest U.S.-born Black men have lower average income (0.82) than any other group of U.S.-born men, including racial/ethnic groups considered part of the collective black. Noticeably, foreign-born collective black and Latino men’s earnings resemble African American men’s earnings, while Mexican-origin and Vietnamese American men appear more on par with Native American men.

Among women, we once again find evidence suggestive of a distinct white-nonwhite income gap and labor hierarchy. Table 3 denotes clustering among white and honorary white ratios and among collective black and Latina ratios, with the key exception of Vietnamese women. Indeed, Vietnamese American women’s income is comparable to that of full-time working white and honorary white women. Cultural differences are often cited as one of the reasons why some Asian groups are more successful in their socioeconomic adaptation to the host society than others (Barringer et al., 1990; Kim, 2002; Sakamoto et al., 2009). Specifically, some scholars argue that East Asian cultures historically influenced by Confucianism and Taoism are conducive to successful incorporation of East Asian ethnic groups (Kim, 2002; Sue & Okazaki, 1990). In this view, East Asian cultures are characterized by strong family ties, a sturdy work ethic, and delayed gratification—features frequently deemed essential for integration and upward mobility in the U.S. (Fuligni et al., 1999; Portes & Rumbaut, 2014; Zhou, 1997; Zhou et al., 2008). It is worth noting that, although geographically southeastern, Vietnamese culture is an integral part of East Asian culture (Choi et al., 2008; Kim, 2002; Zhou, 1997). Among women, then, although the Vietnamese population includes a significant number of refugees and is deemed part of the collective black, Vietnamese American women’s average income more closely approximates that of white/honorary white women than collective black and Latina women.

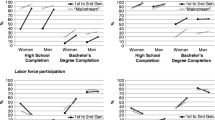

Table 3 also highlights important group-specific gender differences in income. Particularly noteworthy here, minority women’s income ratios (foreign- and U.S.-born) are higher relative to white women (0.86 to 1.09) than their co-ethnic male peers’ ratios relative to white men (0.72 to 1.05), with multiple foreign- and U.S.-born women’s income estimates closely approaching (if not matching and surpassing) those of white women. Comparison of specific racial/ethnic group coefficients and corresponding interactions also suggest race/ethnicity (stratified by nativity) has a larger effect on men’s earnings than women’s. Indeed, racial/ethnic income gaps are consistently wider among men than women across all minority and nativity groups (except Asian Indians). For many of the groups we consider, this suggests racial minority status may create male-specific lags in attainment. Alternatively, this could mean full-time working white women, who serve in this instance as the referent for other women in the workforce, are uniquely disadvantaged when compared to white men. Greater income parity among women does not negate the reality that nearly all women in our analyses—across race/ethnicity and nativity—have significantly lower income levels than their male counterparts. Figure 2 captures this clearly, confirming significant race/ethnic-gender group deficits by nativity. Still, most minority men’s earnings more closely align with those of white women than white men. Such findings support and extend race/gender/nativity intersectional frameworks by highlighting diverse incorporation pathways and gendered racial/ethnic experiences.

Proportion of Logged Total Income for Race/Ethnicity & Gender by Nativity for Full-Time, Full-Year Workers, ACS 2015–2019. Estimates are based on a single pooled model utilizing the full analytic sample. Proportions reflect the antilog of the unstandardized coefficient for each group. U.S.-born white men serve as the overall reference group. Full results and estimates from this model are available upon request. Sensitivity tests capture significant differences between co-ethnic men and women. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Discussion and Conclusions

We focused in this article on how race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity intersect to shape patterns of socioeconomic inequality and mobility among full-time, full-year workers in the Southwest. Once the intersection of Old-World colonial empires, the region today represents a fast-growing postindustrial economy and uniquely diverse demographic landscape. The Southwest’s globalized information-based economy with strong technology sectors attracts a broad cross-section of the American labor force, including an unparalleled combination of immigrant groups. The continuous influx of newcomers from all corners of the globe adds to the diversity of the region. Accordingly, the region’s population is one of the most racially and ethnically diverse in the world.

Our analyses elaborate and extend upon prior scholarship on socioeconomic inequality and mobility and call attention to the ways race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity intersect to affect labor market integration and stratification. Previous work highlights how assimilation and human capital attributes can enhance or hinder (directly and indirectly) employment opportunities, labor market experiences, economic returns, and overall well-being (see, e.g., Alba & Nee, 2003; Lieberson, 1980; Painter & Qian, 2016). Our results are certainly consistent with this point. The introduction of nativity, adaptation, and human capital measures (see Table 2) reduces most income gaps between white men and all other race/ethnic-gender groups considered—particularly Latinos. Yet the fact that income gaps persist for full-time, full-year workers even after taking such background characteristics into account suggests prejudice and exclusion confronting minority men and women. As such, we find support for Hypothesis 1, which predicts the primacy of whites in the Southwest income hierarchy. We also find some support for Hypothesis 2 in that honorary white income levels—specifically Asian Indian men, Asian Indian women, and Chinese women—more closely align with white men and women, respectively, than with other minority men and women, while Filipinos, Native Americans, and the stratum theorized as collective black (Blacks, Latinos, Vietnamese) are consistently and decisively disadvantaged. Filipino and Native American men and women, however, do not display average incomes consistent with honorary white status or stratum. Rather, their earnings are commensurate to collective black levels—a pattern that, for Filipino ethnics, may reflect racialization as/with Latinos in the Southwest, and for Native Americans, a legacy of rural isolation and colonialism that follows them into urban areas to this day.

Taken a step further, we consider inter- and intragroup differences in incorporation and inequality relative to nativity (see Table 3). Our results, which align with segmented assimilation and intersectional frameworks (see, e.g., Portes & Rumbaut, 2014; McCall, 2005), suggest differential incorporation pathways and distinct group-level mobility prospects in the Southwest. Although we do not see strong evidence suggestive of stagnant group-level economic mobility across generations (Hypothesis 3) or a pattern of markedly depressed returns specific to groups with large refugee populations (Hypothesis 4), we do find substantial support for Hypothesis 6, which predicts significant interactions between race/ethnicity, gender, and immigrant status. Indeed, we observe race/ethnic- and nativity-based income differences among men and women, as well as gendered variations within and across race/ethnic groups and nativity (see Figs. 1 & 2). Such findings support an intersectional lens and approach by capturing the complex interplay of multiple axes of inequality that together shape contemporary U.S.- and foreign-born men’s and women’s economic experiences and returns.

Although the gender gap favoring men is a consistent feature among all racial/ethnic groups analyzed (see Table 2 & Hypothesis 5), we also note that gender has an uneven impact on the relative progress observed among U.S.-born generations in the Southwest (see Table 3 & Fig. 2). Chinese American women, for instance, report higher incomes than native white women, while Chinese American men show a deficit relative to their white male counterparts. Asian Indian American men and women, in turn, both show income attainment above their native white counterparts. By the same measure, Vietnamese American women reach parity with native white women, yet their male co-ethnics show a marked lag. Similarly, although Black, Filipina, Guatemalan, Mexican, Salvadoran, and Native American women are disadvantaged relative to white women, they lag to a lesser extent than do their male co-ethnics. Taken together, these comparisons are consistent in that economically active, native-born minority women are closer to parity to their white reference group than their male counterparts are, suggesting that the paths to socioeconomic integration are gendered, although in unexpected ways and depending on the specific group. However, the positive assimilation observed among women of color is only relative, as a more comprehensive male advantage remains firmly in place in the Southwestern workforce. Only the highest earning groups of minority women (Asian Indian, Chinese) match or exceed the lowest earning groups of minority men (Black, Filipino, and Guatemalan).

The income disparities we identify in the Southwest at various intersections of race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity suggest several labor policy solutions moving forward. Most obviously, government actions to address labor discrimination have had (and still have) a positive effect in ameliorating labor market inequities experienced by American women and minorities (Stiglitz, 2022). Worker compensation regulations at the local, state, and federal level can also have significant impacts. Wage compression mechanisms such as minimum wage increases are effective in reducing overall gender income gaps in developed economies (Blau & Kahn, 2003), as well as racial income disparities among U.S. workers (Wursten & Reich, 2021). And because foreign-born workers in the U.S. are concentrated in the lower half of the income distribution, they stand to benefit most from raising wage floors (Joshi et al., 2022).

We acknowledge several analytic limitations to our study. First, we use cross-sectional data. Systematic longitudinal data containing sufficient cases and detailed information on multiple groups are rare for analyses of immigration and socioeconomic inequality. Yet our analyses capture meaningful differences within and across racial/ethnic, gender and nativity lines, and our confidence in these findings is bolstered by the representativeness of the groups we analyze relative to the Southwest context. Second, the data do not provide information on the generational status of persons born in the United States. As such, we cannot distinguish between persons born in the U.S. to foreign-born parents and those born in the U.S. to parents whose family has resided in the country for multiple generations. Our use of nativity status nonetheless taps into group-level assimilation, economic mobility, and variations within and between foreign- and U.S.-born co-ethnics. Finally, the data do not directly account for racial/ethnic- and gender-based closure or discrimination in business or employment. Our analyses are only suggestive in these regards.

Despite these cautions, this article adds to assimilation, stratification, and intersectional literatures. Our analyses: (1) identify important differences in economic incorporation, mobility, and inequality at a crossroads of race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity status in the American Southwest (a key U.S. region with diverse racial/ethnic and immigrant populations); and (2) highlight the fundamental role played by race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity status on the experiences of full-time, full-year workers. Importantly, future research can continue to benefit from intersectional investigations into how assimilation and status hierarchies converge to shape immigrant and minority group opportunities and outcomes. And while this article focused exclusively on full-time, full-year workers, devoting attention to those unable to secure full-time work or engaged outside the formal economy can provide insight toward a better understanding of workplace dynamics and closure related processes—including who gets fired, who gets excluded, and who “opts out.” This speaks to understudied issues affecting immigrant and minority women, in particular, as well as undocumented persons and refugees. Such research is critical given the current U.S. context of escalating anti-immigrant sentiment and action, and the entrenched character and continued prominence of complex race/ethnic- and gender-based inequalities found in the labor market and economy.

Data availability

Data used in this article are publicly available and can be accessed at https://usa.ipums.org/usa/.

Notes

We define the Southwest as: Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah.

Given the confluence of race, ethnicity, and national origin, we use the term race/ethnicity. For a discussion as this relates to Census and ACS data, see Footnote 9. When discussing racial/ethnic and/or national origin groups (U.S.- and foreign-born), we employ the term ethnics to refer to members of these groups (e.g., Asian and Latino ethnics; Chinese and Mexican ethnics). For a critique of broad racialized pan-ethnic classifications, see DiPietro & Bursik (2012); Restifo & Mykyta (2019). For a discussion of the racialization of Hispanics and Latinos, see Ortiz & Telles (2012); Estrada et al. (2020).

Estimates based on 2019 American Community Survey data.

The ACS does not directly ask respondents if they work full-time or part-time. Rather, respondents are asked to report the “usual” number of hours per week they worked the previous year and the number of weeks (Ruggles et al., 2021). Consistent with the U.S. Department of Labor (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020), we classify persons that reported working 35 hours or more per week as full-time. We also designate persons that reported working 48 weeks or more the previous year as full-year workers. We are unable to distinguish, however, between persons that worked 35 + hours per week, 48 + weeks per year at a single job versus those that did so at multiple part-time and/or partial-year jobs because: 1) the ACS does not provide information on whether respondents worked a single job the previous year or multiple jobs; and 2) the ACS does not provide the number of hours or weeks spent at each job for those working multiple jobs. The dataset provides only a single, primary occupation for each respondent (Ruggles et al., 2021). As such, respondents that worked multiple part-time and/or partial-year jobs that amounted to full-time, full-year work (35 + hours per week, 48 + weeks per year) are included in our analyses.

Part-time workers are in many ways unique and distinct from full-time workers. This includes access, participation, and movement in the labor market, as well as reason/purpose (economic vs. noneconomic; voluntary vs. involuntary) for working part-time (e.g., school, semi-retired, childcare, eldercare) (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018). By restricting our sample to persons working 35 + hours per week, 48 + weeks per year, we reduce conflating full-time and part-time workers and their experiences. Even so, we recognize that some full-time, full-year workers in our sample worked multiple part-time and/or partial-year jobs—though we cannot directly track it.

We estimate that only about 3% of full-time, full-year workers ages 25–55 in the Southwest live outside identified MSAs, with an additional 6% living in areas where metropolitan status is indeterminable.

We use detailed racial, ethnic, and national origin codes available via the ACS to construct the 10 above mentioned racial/ethnic group categories. Except for Mexicans, Guatemalans, and Salvadorans, all other racial/ethnic groups considered in our analyses consist of non-Latinos only. Native Americans include both American Indians and Alaskan Natives. In an effort to reduce potential ambiguities, multiracial respondents are not included in our analyses. Persons self-identifying as multiracial comprise a small fraction of cases (less than 2 percent) once we apply sample restrictions.

The U.S. Census Bureau, which administers the ACS, designates five broad racialized pan-ethnic categories for race: 1) white, 2) Black or African American, 3) American Indian or Alaska Native, 4) Asian, and 5) Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (Jones et al., 2021). These five categories represent a general American conceptualization of race based on phenotype combined with ethnicity, national origin, and geographic region (OMB, 1997; see DiPietro & Bursik, 2012 for a critique of such classification schemes). The ACS questionnaire, when asking about race, provides survey respondents the first three racial categories (white, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native) to select from, as well as several specific Asian and Pacific Islander origin categories (e.g., Asian Indian, Chinese, Native Hawaiian, and Samoan). Survey respondents can also write in other specific Asian and Pacific Islander ethnic, cultural, and national origins (e.g., Hmong, Laotian, Fijian, Tongan)—all of which are designated in the ACS questionnaire as races (Ruggles et al., 2021). Importantly, the U.S. Census Bureau conceptualizes and treats Hispanic, Latino, and Spanish origin as distinct from race, and the ACS questionnaire asks a separate question about it. As such, Hispanic origin categories are independent of and cut across race. The ACS questionnaire provides survey respondents several specific Hispanic, Latino, and Spanish origin categories to select from (Mexican/Chicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban), and respondents can write in other specific Hispanic, Latino, and Spanish ethnic, cultural, and national origins (e.g., Colombian, Dominican, Guatemalan, Salvadoran) (Ruggles et al., 2021).

Foreign-born white, in this instance, consists exclusively of non-Latino white Europeans, while foreign-born Black is comprised of non-Latino Black Africans. Given the diversity (and to a certain extent, ambiguity) of groups clustered into U.S. Census race categories, we attempt to preserve a degree of focus and precision among foreign-born whites and Blacks for comparative purposes with other racial/ethnic groups. Native American does not present a foreign-born equivalent for comparison.

U.S.-born citizen and naturalized citizen are collapsed into the single category of U.S. citizen in analyses reported in Table 3 (where each race/ethnic group is stratified by nativity) to avoid model degradation due to collinearity tied to the inclusion of more detailed citizenship and race/ethnic-nativity measures—which diagnostic tests showed posed estimate problems.

We explored the possibility of introducing measures to account for age of U.S. entry (which also taps into whether individuals received their education in the U.S. or abroad) in our analyses. Diagnostic tests, however, revealed model degradation due to collinearity between age of U.S. entry and other key predictors. This was especially problematic with models presented in Table 3 where each race/ethnic group is distinguished by nativity.

We do not include measures for both age and work experience together in our models since age is directly factored into our calculation of work experience. We explored the possibility of substituting age and age-squared in our models for work experience and work experience-squared. Both sets of estimates were consistent and all major patterns held across the board.

We draw a distinction between public and private employment sectors because prior work shows racial/ethnic minorities and women experience more equitable treatment, opportunities, and mobility prospects in the public sector—though recent evidence suggests this is changing with the privatization of the public sector (Wilson, 1997, 2009; Wilson et al, 2015). In addition, public and private employment sectors show distinct tendencies for union membership. An estimated 34.8 percent of public-sector workers are union members compared to just 6.3 percent of private-sector workers (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021).

Extended family members include any relative that is not the household head, his/her spouse, or his/her child.

Full results and interaction effect estimates from the pooled model are not shown but are available upon request.

All models include statistical controls for MSA (results not shown).

References

Adelman, R. M., & Tsao, H. (2016). Deep South demography: New immigrants and racial hierarchies. Sociological Spectrum, 36(6), 337–358.

Alba, R. D., & Nee, V. (2003). Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Harvard University Press.

Barringer, H. R., Takeuchi, D. T., & Xenos, P. (1990). Education, occupational prestige, and income of Asian Americans. Sociology of Education, 63(1), 826–874.

Bennett, T., Savage, M., Silva, E., Warde, A., Gayo-Cal, M., & Wright, D. (2009). Culture, Class, Distinction. Routledge.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2003). Understanding international differences in the gender pay gap. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(1), 106–144.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2017). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3), 789–865.

Blau, F. D., Kahn, L. M., Moriarty, J. Y., & Souza, A. P. (2003). The role of the family in immigrants’ labor-market activity: An evaluation of alternative explanations: Comment. The American Economic Review, 93(1), 429–447.

Blea, I. (1992). La Chicana and the Intersection of Race, Class, and Gender. Praeger.

Bloemraad, I. (2006). Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada. University of California Press.

Bloemraad, I., Korteweg, A., & Yurdakul, G. (2008). Citizenship and immigration: Multiculturalism, assimilation, and challenges to the nation-state. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 153–179.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2004). From bi-racial to tri-racial: Towards a new system of racial stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 27(6), 931–950.

Borch, C., & Corra, M. K. (2010). Differences in earnings among black and white African immigrants in the United States, 1980–2000: A cross-sectional and temporal analysis. Sociological Perspectives, 53(4), 573–592.

Borjas, G. J. (1989). Economic theory and international migration. The International Migration Review, 23(3), 457–485.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press.

Browne, I., & Misra, J. (2003). The intersection of gender and race in the labor market. Annual Review of Sociology, 29, 487–513.

Budiman, A., Tamir, C., Mora, L., & Noe-Bustamante, L. (2020). Statistical Portrait of the Foreign-Born Population in the United States, 2018. Pew Hispanic Center.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). Monthly Labor Review: Who chooses part-time work and why? U.S. Department of Labor.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). Employment Characteristics of Families—2019. U.S. Department of Labor.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021). News Release: Union Members—2020. U.S. Department of Labor.

Castaño, A. M., Fontanil, Y., & García-Izquierdo, A. L. (2019). “Why can’t I become a manager?” —A systematic review of gender stereotypes and organizational discrimination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(10), 1–29.

Chapman, S. J., & Benis, N. (2017). Ceteris non paribus: The intersectionality of gender, race, and region in the gender wage gap. Women’s Studies International Forum, 65, 78–86.

Chiswick, B. R., Lee, Y. L., & Miller, P. W. (2005). A longitudinal analysis of immigrant occupational mobility: A test of the immigrant assimilation hypothesis. International Migration Review, 39(2), 332–353.

Choi, Y., He, M., & Harachi, T. W. (2008). Intergenerational cultural dissonance, parent–child conflict and bonding, and youth problem behaviors among Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(1), 85–96.

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge.

Connor, P. (2010). Explaining the refugee gap: Economic outcomes of refugees versus other immigrants. Journal of Refugee Studies, 23(3), 377–397.

Curran, S. R., Shafer, S., Donato, K. M., & Garip, F. (2006). Mapping gender and migration in sociological scholarship: Is it segregation or integration? International Migration Review, 40(1), 199–223.

Davis, J. J., Roscigno, V. J., & Wilson, G. (2016). American Indian poverty in the contemporary United States. Sociological Forum, 31(1), 5–28.

Davis, K. (2008). Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful. Feminist Theory, 9(1), 67–85.

De Jong, G. F., & Madamba, A. D. (2001). A double disadvantage? Minority group, immigrant status, and underemployment in the United States. Social Science Quarterly, 82(1), 117–130.

De Vroome, T., & Van Tubergen, F. (2010). The employment experience of refugees in the Netherlands. International Migration Review, 44(2), 376–403.

DeSilver, D. (2013). Global Inequality: How the U.S. Compares. Washington, DC, Pew Hispanic Center.

DiPietro, S. M., & Bursik, R. J., Jr. (2012). Studies of the new immigration: The dangers of pan-ethnic classifications. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 641, 247–267.

DiPrete, T. A., & Buchmann, C. (2013). The rise of women: The growing gender gap in education and what it means for American schools. The Russell Sage Foundation.

Doorn, D. J., & Kelly, K. A. (2015). Employment change in the US Census Divisions from 2000 through the Great Recession and current recovery. Regional and Sectoral Economic Studies, 15(2), 5–22.

Dumais, S. A. (2002). Cultural capital, gender, and school success: The role of habitus. Sociology of Education, 75(1), 44–68.

Duncan, B., & Trejo, S. J. (2015). Assessing the socioeconomic mobility and integration of US immigrants and their descendants. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 657(1), 108–135.

Elliott, J. R., & Smith, R. A. (2001). Ethnic matching of supervisors to subordinate work groups: Findings on “bottom-up” ascription and social closure. Social Problems, 48(2), 258–276.

Elliott, J. R., & Smith, R. A. (2004). Race, gender, and workplace power. American Sociological Review, 69(3), 365–386.

England, P., Levine, A., & Mishel, E. (2020). Progress toward gender equality in the United States has slowed or stalled. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(13), 6990–6997.

Estrada, E., Cabaniss, E., & Coury, S. (2020). Racialization of Latinx immigrants: The role of (seemingly) positive newspaper discourse. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 17(1), 125–146.

Feliciano, C. (2006). Unequal Origins: Immigrant Selection and the Education of the Second Generation. LFB Scholarly Publishing.

Frank, R., Akresh, I. R., & Lu, B. (2010). Latino immigrants and the US racial order: How and where do they fit in? American Sociological Review, 75(3), 378–401.

Fuligni, A. J., Tseng, V., & Lam, M. (1999). Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development, 70(4), 1030–1044.

Gans, H. J. (2005). Race as class. Contexts, 4(4), 17–21.

Glazer, N. (1971). Blacks and ethnic groups: The difference, and the political difference it makes. Social Problems, 18(4), 444–461.

Glenn, E. N. (1999). The social construction and institutionalization of gender and race: an integrative framework. In M. Marxerree, J. Lorber, & B. B. Hess (Eds.), Revising Gender (pp. 3–43). Sage Publications.

Glick, J. E., & Han, S. Y. (2015). Socioeconomic stratification from within: Changes within American Indian cohorts in the United States: 1990–2010. Population Research and Policy Review, 34(1), 77–112.

Gordon, M. M. (1964). Assimilation in American Life. Oxford University Press.

Greenman, E., & Xie, Y. (2008). Double jeopardy? The interaction of gender and race on earnings in the United States. Social Forces, 86(3), 1217–1244.

Greenwood, M. J. (2014). Migration and Economic Growth in The United States: National, Regional, and Metropolitan Perspectives. Academic Press.

Hall, T. D. (1989). Social Change in the Southwest, 1350–1880. University of Kansas Press.

Haller, W., Portes, A., & Lynch, S. M. (2011). Dreams fulfilled, dreams shattered: Determinants of segmented assimilation in the second generation. Social Forces, 89(3), 733–762.

Heathcote, J., Perri, F., & Violante, G. L. (2010). Unequal we stand: An empirical analysis of economic inequality in the United States, 1967–2006. Review of Economic Dynamics, 13(1), 15–51.

Huyser, K. R., Sakamoto, A., & Takei, I. (2010). The persistence of racial disadvantage: The socioeconomic attainments of single-race and multi-race Native Americans. Population Research and Policy Review, 29(4), 541–568.

Jiménez, T. R. (2008). Mexican immigrant replenishment and the continuing significance of ethnicity and race. American Journal of Sociology, 113(6), 1527–1567.

Jones, N., Marks, R., Ramirez, R., & Ríos-Vargas, M. (2021). 2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country. U.S. Census Bureau.

Joshi, P., Walters, A. N., Noelke, C., & Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2022). Families’ job characteristics and economic self-sufficiency: Differences by income, race-ethnicity, and nativity. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 8(5), 67–95.

Kanaiaupuni, S. M. (2000). Reframing the migration question: An analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico. Social Forces, 78(4), 1311–1347.

Kim, J., & Carter, S. D. (2016). Gender inequality in the U.S. labor market: Evidence from the American Community Survey. In M. F. Karsten (Ed.), Gender, Race, and Ethnicity in the Workplace: Emerging Issues and Enduring Challenges (pp. 59–82). Praeger.

Kim, R. Y. (2002). Ethnic differences in academic achievement between Vietnamese and Cambodian children: Cultural and structural explanations. The Sociological Quarterly, 43(2), 213–235.

Kmec, J. A. (2003). Minority job concentration and wages. Social Problems, 50(1), 38–59.

Lee, J., & Bean, F. D. (2007). Reinventing the color line: Immigration and America’s new racial/ethnic divide. Social Forces, 86(2), 561–586.

Lieberson, S. (1980). A Piece of the Pie: Blacks and White Immigrants Since 1880. University of California Press.

Lu, Y., & Huo, F. (2020). Immigration system, labor market structures of high-skilled immigrants in the United States and Canada. International Migration Review, 54(4), 1072–1103.

Lu, Y., & Li, X. (2021). Vertical education-occupation mismatch and wage inequality by race/ethnicity among highly educated U.S. workers. Social Forces, 100(2), 706–737.

Lueck, K. (2018). Socioeconomic success of Asian immigrants in the United States. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(3), 425–438.

Mandel, H., & Semyonov, M. (2014). Gender pay gap and employment sector: Sources of earnings disparities in the United States, 1970–2010. Demography, 51(5), 1597–1618.

Marrow, H. B. (2009). New immigrant destinations and the American colour line. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32(6), 1037–1057.

Masouk, N., & Junn, J. (2013). The Politics of Belonging: Race, Public Opinion, and Immigration. The University of Chicago Press.

McCall, L. (2001). Sources of racial wage inequality in metropolitan labor markets: Racial, ethnic, and gender differences. American Sociological Review, 66(4), 520–541.

McCall, L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs, 30(3), 1771-l880.

Millsap, A. (2016). State labor force changes and the need for a flexible labor market. Forbes. August 5, 2016.