Abstract

Under the act that established the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), persons 70 years of age or above are automatically enrolled in the scheme and therefore can access health services free at the point of use. This suggests that the elderly who are unable to afford the premiums of private health insurance can enrol in the NHIS thereby eliminating the possibility of disparities in health insurance coverage. Notwithstanding, few studies have examined health insurance coverage among the elderly in Ghana. The lack of studies on the elderly in Ghana may be due to limited data on this important demographic group. Using data from the Study on Global Ageing and Health and applying logit models, this paper investigates whether the pro-poor exemption policy is eliminating disparities among the elderly aged 70 years and older. The results show that disparities in insurance coverage among the elderly are based on respondents’ socio-economic circumstances, mainly their wealth status. The study underscores the need for eliminating health access disparities among the elderly and suggests that the current premium exemptions alone may not be the solution to eliminating disparities in health insurance coverage among the elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, it is estimated that 2 billion people will be over the age of 60 by the year 2050 with about 80% of this population expected to reside in low and middle income countries (LMIC) (Aboderin 2012; Beard et al. 2012; Lancet 2012). Accordingly, most LMICs have begun to witness considerable increases in the populations of the elderly and the associated health challenges unique to this group. With limited regenerative abilities, the elderly are at heightened risk of poor health due to pronounced risk of diseases, syndromes and sickness (World Health Organization 2004). Also, with many LMICs already experiencing economic challenges, any projected increase in the elderly population will have far reaching implications for the broader health systems in such societies. This makes the provision of appropriate health services to cater for the needs of the elderly a major challenge for LMICs.

With an older than average population compared to other countries in SSA, Ghana’s young age structure is fast changing to an older population. The United Nations projected, for instance, that Ghana’s elderly population will grow from 5.3 to 7.9% by 2050 (United Nations: Department of Social and Economic Affairs 2013). This demographic shift will certainly increase demand for age-appropriate health care for the elderly. Recognizing the special health needs of its older population, Ghana implemented a Social Health Protection (SHP) program within its National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), with the aim of reducing financial barriers associated with accessing healthcare services for the poorest and disadvantaged groups including the elderly. At the moment, the elderly are exempted from paying premium for Ghana’s NHIS suggesting that barriers to accessing health insurance have been reduced if not completely eliminated. Yet, not many studies have examined access to the NHIS among the elderly in Ghana and whether this varies by their socio-economic characteristics or wealth status. The omission in the literature is surprising especially when it is documented that quite a substantial proportion of the elderly are poor and reside in rural areas where accessing the scheme may be challenging and difficult (HelpAge-International 2008; Aboderin 2012).

Furthermore, as most of the populations in sub-Saharan Africa are young, a lot more attention has been directed to the demographic and health needs of this vulnerable group to the disadvantage of other vulnerable groups including the elderly. This paper contributes to broader debates on ageing and the health needs of the elderly in Ghana with implications for other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Specifically, the paper examines health insurance access among the elderly which for a very long time has been neglected in the scholarly literature in sub-Saharan Africa. We also explore if significant differences exist among the Ghanaian elderly population belonging to different socio-economic strata. The findings will be an important in helping the government formulate better policies related to health insurance access for the elderly in Ghana with implications for other sub-Saharan African countries.

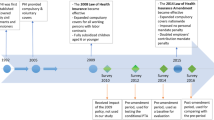

Health Insurance in Ghana

Ghana’s NHIS, effectively operating from 2004, is a national health financed scheme intended to increase health service access for its population. Prior to its implementation, the ‘cash and carry’ system restricted health access for large sections of the populations (i.e., poor, rural, elderly, women), contributing to significant disadvantage due to fees associated with seeking health care (Asenso-Okyere et al. 1998; James et al. 2006; Nyonator and Kutzin 1999). In light of these disparities, the NHIS was developed as an equitable means of health care financing.

Under the national health insurance act (Act 650, later replaced by Act 852)—which established the NHIS—health insurance is mandatory for every Ghanaian. However, no specific punitive measures are prescribed for violators, and enforcement relating to violations is yet to be documented (Dixon et al. 2011). The act allows three distinct types of insurance schemes in Ghana—District Mutual Health Insurance Schemes (DMHIS), private mutual insurance schemes and private commercial insurance schemes. The DMHIS is the most popular and operates in all districts of the country while the other two are mainly urban-centred and cover less than one percent of insured individuals (Gajate-garrido and Owusua 2013). Although the activities of the two other types of private insurance are regulated by the National Health Insurance Authority, they do not receive financial support from government.

Collectively, the DMHIS make up the NHIS and are financed mainly through central government level funds and premiums. Revenue for the NHIS comes from four main sources—a value-added tax (VAT), the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT—a national pension scheme for formal sector employees), investment income and premiums. In 2011, VAT provided over 72% of the scheme’s revenue, while SSNIT, investment income and premiums contributed about 17, 5 and 4%, respectively (National Health Insurance Authority Ghana 2011). All formal sector employees and their dependants (18 years or less) are automatically enrolled, and their premiums are collected at the central level via payroll deductions. Self-employed individuals and informal sector workers need to enrol directly in the NHIS.

The NHIS covers outpatient, inpatient and emergency care, deliveries, dental care and essential drugs which constitute about 95% of the disease burden in Ghana. Individuals need to register with the NHIS once in their lifetime and then renew their membership annually. Additionally, the NHIS offers exemption from fees for certain populations. Children under 18, pregnant women, indigents (i.e. the poor and destitute) and all persons over 70 years are exempted from paying premiums, although they still need to register and renew their membership annually. All exempt groups including Ghanaians over 70 years pay a registration fee of GH¢ 4.00 (about $1). The same amount is paid for renewal every year (Nyonator 2012). In 2011, 8.2 million people (33% of the population) were active members (registered and had renewed their membership that year) with 4.9% of those active members over the age of 70 (National Health Insurance Authority Ghana 2011).

The Elderly and Health Insurance Coverage

Although evidence suggests coverage under the NHIS is effective for improving health outcomes (Mensah et al. 2010), studies have revealed that Ghana continues to face difficulties enrolling segments of the population including the poorest of society (Dixon et al. 2011). Besides financial constraints, the elderly may face additional barriers to enrolling in health insurance because ageing—particularly in the developing world—is associated with heightened risks and overall social and physical vulnerability (Crooks 2009; Issahaku and Neysmith 2013). Studies show that the incidence and prevalence of poverty is high among the elderly in Ghana. While enrolment is free for the elderly, anecdotal evidence suggests that quite a substantial proportion of this demographic group are not insured or enrolled on the NHIS in Ghana. For instance, Parmar et al. (2014) found that about 38% of the Ghanaian elderly population were not insured compared to 52% in Senegal. Although exempted from payments, dealing with ‘hidden’ costs, including those related to transportation to registration centres may serve as a deterrent for the poor who are extremely vulnerable. Against this backdrop, this paper investigates disparities in health insurance coverage among elderly Ghanaians by wealth status. By focusing on the elderly population, this paper departs from previous studies that examined the determinants of NHIS enrolment among the general population in Ghana (Dixon et al. 2011, 2014a; Jehu-Appiah et al. 2011; Sarpong et al. 2010). It is hypothesized that wealthier individuals will be more likely to enrol compared to their poorer counterparts. For the purposes of this study, elderly is used to describe individuals who are 70 years or older.

A main challenge is that older people in SSA usually retire in rural areas, with poor infrastructure and acute problems of basic service provision (Issahaku and Neysmith 2013). To this extent, we expect the majority of the respondents in our sample to reside in rural areas and to be less likely to enrol on the NHIS, compared with those in the urban areas. Additionally, previous research among the elderly found gender disparities in access to health care services including insurance enrolment (Davidson et al. 2011). For elderly women in particular, the challenges of enrolment are more severe due to gender-related discrimination. Older women encounter social isolation, inequity and economic adversity that affect their ability to utilize health insurance schemes with implications for their overall physical and mental health (Bastos et al. 2009; Brady and Kall 2008). In their study on enrolment of older people in SHP programs in Senegal and Ghana, Parmar et al. (2014) found significant gender differences as men were more likely to enrol in Senegal. Similar results were found in Ghana, but the differences were not statistically significant. Thus, based on the extant literature, we expect women to be more likely to enrol compared to their male counterparts.

The fact that many elderly individuals in developing countries have low educational attainment makes them even more vulnerable. While education influences knowledge of available social services including access to social protection programs, the lack of it may limit economic participation especially for those in the informal sector where there is limited provision for retirement and economic security (Altschuler 2004; United Nations, D. of E. and S. A. P 2007). The empirical literature establishing links between education and enrolment on social protection programs show that individuals with higher education are more likely to enrol compared to those without any education (Dixon et al. 2011). Thus, based on previous literature, we hypothesize educated elderly Ghanaians will enrol compared to the uneducated.

Further, given limited formal employment records, the elderly have no access to formal social security arrangements like pensions—deepening their poverty levels. It is estimated that only 17% of older people in SSA receive an old age pension (ILO 2014). The consequences of unavailable social security arrangements are particularly serious given that health care expenditures increase at this stage of the life course (Mendis et al. 2011; Williams and Kurina 2002; World Health Organization 2009). Through exemption policies for certain vulnerable groups (including the elderly), the government of Ghana has attempted to improve access to the scheme. These exemptions have become necessary because most elderly people do not have pension benefits, since the majority work in the informal sector and removing such barriers may facilitate enrolment. Even for those in the formal sector who have some pension benefits, this may not be enough to cover their health care needs in old age (Issahaku and Neysmith 2013). While formal sector employees are enrolled automatically, the self-employed and those in the informal sector are expected to enrol directly on to the NHIS Parmar et al. (2014). Based on previous literature, we expect type of employment to determine enrolment among the elderly in Ghana.

It has been demonstrated, however, that enrolment on to social protection programs are not only influenced by gender and class, but also ethnicity and religion (Marmot et al. 2008; Parmar et al. 2014). Although not necessarily on the elderly, previous studies on the relationship between ethnicity, religion and NHIS enrolment are mixed. While some studies show ethnicity and religion as important determinants of health insurance access in Ghana (Dixon et al. 2011; Jehu-Appiah et al. 2011), others show no such relationship (Parmar et al. 2014). We add ethnicity and religion as statistical controls in our models, yet expect these variables to have independent effects on access to NHIS among the elderly in Ghana.

Finally, as individuals age, health costs related to the treatment of chronic and non-communicable diseases (such as hypertension, arthritis, angina, diabetes and stroke) also increase. This makes the exemption policy under the NHIS extremely crucial for the elderly as it may increase health care access—with implications for morbidity and mortality among this demographic group. It is expected that respondents suffering from chronic diseases that require health care will out of need enrol on NHIS compared to those with no chronic conditions.

Materials and Methods

Data and Analytical Sample

Our study used the first wave of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) from Ghana. Data were collected between January 2007 and December 2008 through face-to-face interviews. The SAGE is a nationally representative multi-country study (involving China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russian Federation and South Africa) that gathered data on older persons (50 years and over) to respond to their health needs. To enable comparison, the SAGE also includes a smaller sample of young adults between the ages of 18 and 49 years. A stratified multi-stage cluster design was employed to select respondents for the survey in Ghana. First, the sample was stratified by administrative region (using all the ten regions in Ghana) and location (urban/rural). Some 235 enumeration areas (EA) were selected as primary sampling units. Enumeration areas that did not have persons who are 50 years or older were not included. Within each EA, 20 households with one or more persons who was 50 years or over and four households with members aged 18–49 were selected. From these localities, 5269 households were surveyed. A total of 5573 (Male = 2799 and Females = 2764) individuals were then sampled from these households (Biritwum et al. 2013). Response rates at both household and individual levels were 86 and 80%, respectively. For the purposes of this study, only individuals aged 70 years and above were included. Thus, the analytical sample in this study was 1534.

Measures

The dependent variable in this study, health insurance coverage, was derived from the following question ‘do [you] have health insurance coverage?’ with the following response categories: ‘Yes, mandatory insurance’, ‘Yes, voluntary insurance’, ‘Yes, both mandatory and voluntary insurance’ and ‘No, none’. This was transformed and re-categorized to indicate if respondents had health insurance coverage or not. Consequently, health insurance status was coded as 0 = uninsured and 1 = insured. Wealth status, the focal independent variable in the study, was operationalized using respondent’s household income quintile. The SAGE data used permanent income estimates derived from household assets and characteristics of the dwelling to compute household income quintile (Biritwum et al. 2013). Household income quintile is an ordinal variable with five categories—poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest. Additionally, we controlled for variables that have been identified in the literature as important correlates of health care service utilization (Gelberg et al. 2000). The following variables were selected as controls: age; gender coded (1 = Male, 2 = Female); education coded (0 = No formal education, 1 = Primary, 2 = Secondary, 3 = College/University); marital status coded (1 = Married, 2 = Separated/Divorced, 3 = Widowed, 4 = Never Married); ethnicity coded (1 = Akan, 2 = Ewe, 3 = Ga-Adangbe, 4 = Gruma, 5 = Mole-Dagbani, 6 = Other ethnic group); religion coded (1 = Christian, 2 = Muslim, 3 = Traditional, 4 = Other religion, 5 = None); and location of residence coded (1 = Urban, 2 = Rural). In addition to the above socio-economic and demographic factors, we also controlled for self-reported prevalence of chronic conditions among respondents. Disease prevalence or conditions constitute a need for health care access and tend to influence health care behaviours (Andersen and Newman 1973; Gerdle et al. 2004). Thus, the following chronic conditions were used: ever been diagnosed with arthritis coded (0 = No, 1 = Yes); ever been diagnosed with angina coded (0 = No, 1 = Yes); ever been diagnosed with hypertension coded (0 = No, 1 = Yes), ever been diagnosed with stroke coded (0 = No, 1 = Yes); ever been diagnosed with diabetes coded (0 = No, 1 = Yes); and ever been diagnosed with asthma coded (0 = No, 1 = Yes). Missing cases made up less than 1% for most variables and were deleted from our analysis.

Analytical Strategy

Descriptive and multivariate techniques were employed for analysis. Specifically, we use binary logit models given the dichotomous nature of our outcome variable. The logit link function was used given that cases were distributed almost evenly across the categories on the dependent variable. Standard regression techniques such as logit models are built under the assumption of independence of subjects. However, the SAGE has a hierarchical structure with respondents nested within clusters which could potentially produce biased standard errors. We handled this problem in STATA 12SE by imposing a ‘cluster’ variable—typically respondent’s cluster ID numbers on our models. STATA 12SE provides an outlet through which the standard errors can be adjusted thereby producing statistically robust parameter estimates (see Tenkorang and Owusu 2010). We report exponentiated beta coefficients (Odds ratios) in Tables 2 and 3 which show results of bivariate and multivariate analyses, respectively. Two multivariate models are built to examine the relationship between health insurance coverage and wealth status. In Model 1, we control for respondent’s socioeconomic and demographic factors, and Model 2, self-reported chronic conditions. The analyses adjusted for the sample weights included in the data.

Results

Univariate

Table 1 presents the distribution of the study participants as well as Chi squared tests describing the relationship between health insurance coverage and selected explanatory factors. The average age of respondents was about 76 years and females constitute the largest proportion of the sample (56%). Respondents who were married or cohabiting constitute the largest proportion of the insured, while those who were widowed constitute the largest proportions of the uninsured. Compared with the uninsured, insured respondents are relatively well educated, worked in the public and informal sectors of the economy, they are wealthier and resided in urban areas. The results also indicated that insured elderly have higher rates of chronic conditions. It is important to indicate that generally about 48% of respondents were insured compared to 52% who were not insured.

Bivariate

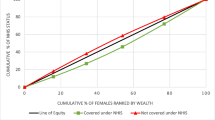

Table 2 shows bivariate relationships between health insurance coverage and selected independent variables. Wealth status was significantly associated with health insurance coverage. Specifically, respondents in the middle, poorer and poorest income quintiles were all less likely to have health coverage compared to their counterparts in the richest income quintile. Separated or divorced individuals were 39% less likely to have insurance coverage compared to the married. Compared to Akans, Ga-Adangbes and those in the ‘Other’ ethnicity category had lower odds of insurance coverage. Relative to Christians, traditionalist and respondents with no religion were 0.33 and 0.32 times less likely to have health insurance, respectively. Respondents residing in rural areas had lower odds of insurance coverage compared to those in urban areas. In the bivariate analysis, three of the five selected chronic conditions were significantly associated with the likelihood of health insurance coverage. Individuals who indicated that they were hypertensive had diabetes and asthma, and had higher odds of health insurance coverage compared to those without these conditions.

Multivariate

In Model 1 of the multivariate analysis, the observed relationship between health insurance coverage status and income quintile persisted. Respondents in the middle and poorest income quintiles were 39 and 42% less likely to have health insurance coverage compared to those in the richest wealth quintile, respectively (OR 0.61, P < 0.05; and OR 0.57, P < 0.05, respectively). It is observed, however, that the effects of wealth were significantly attenuated with other potential confounders added in the multivariate analysis.

Some control variables were also statistically associated with health insurance coverage in Model 1. Specifically, marital status, occupation, ethnicity, religion and location of residence were significantly associated with health insurance coverage among the elderly. Separated and divorced individuals were less likely to have health insurance compared to those who are married or cohabiting (OR 0.56, P < 0.01). Respondents engaged in the informal sector had higher odds of having health insurance compared to those who are self-employed (OR 1.61, P < 0.05). Ga-Adangbes compared to Akans were less likely to have health insurance (OR 0.60, P < 0.05). Traditionalists compared to their Christian counterparts were 61% less likely to have health insurance coverage (OR 0.39, P < 0.001). Respondents belonging to ‘Other’ religious groups were less likely to have health insurance compared to Christians (OR 0.44, P < 0.05). Those without any religious affiliation were also less likely to have health insurance coverage compared to Christians (OR 0.35, P < 0.01). Respondents who live in rural areas had lower odds of health insurance coverage compared to those in urban areas (OR 0.75, P < 0.05).

The final model added self-reported prevalence of chronic conditions. The association between wealth (the focal independent variable) and health insurance coverage was statistically robust. We found that respondents in the middle income quintile compared to those in the richest income quintile had 0.62 lower odds of health insurance coverage (OR 0.62, P < 0.05). Also, the poorest respondents were significantly less likely to have health insurance coverage compared to the richest respondents (OR 0.58, P < 0.05).

Apart from location of residence, all the socioeconomic and demographic control variables which were significant in Model 1 remained statistically robust in Model 2 (see Table 3). For example, for marital status, separated and divorced respondents were significantly less likely to have health insurance coverage compared to those who are married or cohabiting (OR 0.56, P < 0.01), while for occupation, informal sector workers were significantly more likely to have health insurance compared to those in who are self-employed (OR 1.66, P < 0.05). Ga-Adangbes were significantly less likely to have health insurance coverage compared to Akans (OR 0.59, P < 0.01). Compared to Christians, adherents of the traditional religion were 0.39 times less likely to have health insurance coverage, while those who belong to the ‘Other’ religious faiths were 0.46 times less likely to have health insurance compared to Christians. The elderly who have no religious affiliation were each less likely to have health insurance coverage compared to their Christian counterparts (OR 0.36, P < 0.01). Unlike in the bivariate analysis, only one of the selected chronic conditions was significantly associated with the likelihood of health insurance coverage among respondents in the multivariate analysis. Respondents with asthma were 1.84 times more likely to have health insurance coverage compared to those who indicated that they did not have the condition (OR 1.84, P < 0.05).

Discussion

This study examined disparities in health insurance coverage among the elderly in Ghana and found that differences exist regarding health insurance coverage mostly determined by respondent’s wealth status. This finding is at variance with the pro-poor orientation and equity mandate of the NHIS that seeks to eliminate disparities in health care access within the population, particularly for vulnerable groups including the elderly. Health insurance is important for improving curative and preventive health care with implications for morbidity and mortality outcomes (Amin et al. 2010; Gnawali et al. 2009; Jowett et al. 2004; Lei and Lin 2009). Among the elderly, this is even more salient because of the peculiar health care needs associated with ageing. The introduction of the NHIS as a pro-poor policy with premium payment exemptions for persons 70 years and over was aimed at helping bridge the gap between the poor and rich in respect of health care access (Agyepong and Adjei 2008; James et al. 2006; Nyonator and Kutzin 1999). Yet the findings here show that for the elderly, poverty remains a barrier to health insurance enrolment.

In Ghana where the retirement age is 60 years and pensions tend to be generally low, removing financial barriers for the elderly is critical for improving health access. The implication of the findings here suggest that the NHIS exemption policy in its current form may not have been very successful at bridging the gap between the poor and wealthy elderly regarding health insurance coverage. A couple of reasons are proposed here. First, it is possible that the observed differences may be due to the NHIS registration fee (the equivalent of about $1), which is required of everyone regardless of premium exemption. Although this financial requirement for registration seems negligible, for the poor without any direct source of income, raising approximately $1 may be difficult. Second, the cost of registration might only be a fraction of the entire cost of getting registered (e.g. transportation cost to registration centres, unofficial payments, etc.). Further exploration of the data showed that majority of the elderly in this study who fall in the poor and middle wealth quintiles reside in rural areas unlike the richer and richest elderly Ghanaians who mostly reside in urban areas. This means the rural poor are faced with severe challenges of enrolling or getting covered; challenges that not only emanate from their poverty but also their location. Rural locations in Ghana tend to be highly underdeveloped and lacking basic facilities such as adequate roads, schools, good source of drinking water, electricity and health facilities (Kuuire et al. 2015). Thus, the utter lack of facilities in rural areas makes it difficult for older people in such locations to benefit from the exemption policy of the NHIS. Additionally, lack of identification and documentation, such as proof of age (i.e. birth certificate), often prevents older people from accessing the health exemption (HelpAge-International 2008).

Some studies have suggested that the exemption policy of the NHIS favours people in certain groups—particularly the elderly and children who are more likely to be poor (Derbile and Van Der Geest 2013). Our findings show that even within supposed favoured groups such as the elderly, disparities in health insurance coverage based on wealth status exist. This is amidst mounting evidence that the rich continue to be the biggest beneficiaries from the introduction of the NHIS (Amoako Johnson et al. 2015; Dixon et al. 2014; Parmar et al. 2014).

Although not the central focus of this study, it is important to discuss, some selected socioeconomic and demographic factors (marital status, occupation, ethnicity and religion) that influenced health insurance coverage. The finding that widowed and separated respondents were less likely to have health insurance coverage compared to the married perhaps indicates the importance of social capital derived from marriage and how this affects health outcomes including access to important health services (Kawachi et al. 2008). Spouses provide not only emotional support, but also financial resources to their partners in times of need and as a result may have improved health access and outcomes compared to the single and never married. This is more pronounced for the elderly who tend to have limited social networks and connections within their communities (Laporte et al. 2008; Parmar et al. 2014; Ramlagan et al. 2013).

Regarding employment, some studies have documented that employees in the informal sector may be excluded from enrolling in health insurance due to challenges of affordability (Derbile and Van Der Geest 2013; Gajate-garrido and Owusua 2013). For example, Gajate-garrido and Owusua (2013) argue that many in the informal sector in developing economies such as Ghana are poor. Yet, they are not categorized as indigents and are expected to pay premium. In the face of poverty, such payments may serve as a barrier for enrolment. However, our study showed that the elderly in the informal sector were more likely to have health insurance coverage. As the retirement age in Ghana is set at 60 years, it is mostly the case that Ghanaians who retire still remain economically active well beyond their retirement age and may be engaged in the informal sector (Ahadzie 2009; Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) (2013). Income derived from such engagements may facilitate health insurance enrolment among this group.

With regard to ethnicity, we found that Ga-Adangbes were less likely to enrol in NHIS compared to Akans. A cross-classification of ethnicity and wealth status showed that the majority of Akans were in the middle income category compared to Ga Adangbes who mostly fell in the poorer and poorest wealth quintiles. Also, relatively higher proportions of Akans resided in urban areas while the majority of Ga-Adangbes resided in rural areas. It is evident that the ethnic difference in health insurance enrolment is an artefact of the socio-economic differences existing between the two ethnic groups.

Evidence on the relationship between religion and health insurance coverage in Ghana is mixed. For instance, Jehu-Appiah et al. (2011) found that Muslims were more likely to be covered by NHIS. Contrary to this, some other studies demonstrate Muslims, traditionalists and respondents with no religion were less likely to be covered by NHIS compared to Christians (Dixon et al 2014a, b; Jehu-Appiah et al. 2012). Our findings are consistent with several other studies that show traditionalists, and respondents belonging to ‘Other’ faiths, or have no religious affiliation, were less likely to have health insurance coverage compared to Christians. Some research in Ghana suggests that Christians are more likely to accept and patronize western or mainstream health services compared to their counterparts in other religions (Gyimah et al. 2006). Gyimah and colleagues explain that this may be due to theological differences between religions where the norms of some religious groups may encourage certain attitudes toward western medicine. It is also the case that the observed differences may reflect socio-economic gaps between Christians and people in other religious denominations. This is more the case when this analysis indicated Christians tend to be more educated and wealthier than Traditionalists, people of ‘Other’ religions and those with no religious affiliations.

The findings on the relationship between health insurance status and chronic conditions among the elderly were interesting. Among the selected chronic conditions, only asthma had a significant association with health insurance status. Asthmatic respondents were more likely to have insurance coverage. The reasons for this observation are unclear. A potential explanation may be due to the relative ease in understanding the signs of asthma, compared to determining the associated symptoms of hypertension, diabetes, angina and stroke. Since asthma is easily diagnosed, those with asthma perhaps recognized the need to obtain health insurance coverage because they understand they are more likely to need health care. As a result, they may be more likely to obtain health insurance coverage. Additionally, unlike the other chronic diseases (i.e. hypertension, angina, stroke, diabetes and arthritis), which are generally associated with lifestyle and also tend to occur later in life, asthma usually manifests itself relatively much early in life. Perhaps, these differences might be responsible for the findings obtained in this study. The finding that those with chronic conditions are more likely to be insured could also reflect some selection effects especially as individuals are more likely to enrol when there is a pressing health need—such as being diagnosed with a chronic condition.

Policy Implications and Conclusions

Like other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Ghana’s population has been described as ageing very fast, especially given that an increasing proportion of Ghanaians are surviving beyond age 60 (United Nations: Department of Social and Economic Affairs 2013). The changing age structure and demography of the Ghanaian population raises several important questions, including those related to health insurance and health care access. This study offers new insights on the determinants of health insurance coverage among the elderly in the context of the premium exemption policy, revealing that socio-economic barriers to insurance coverage persist despite the exemption policy for the elderly. Our findings have important implications for policy makers as it suggests the removal of economic barriers that militate against the elderly in accessing health insurance as this is crucial to reducing morbidity and mortality among this important demographic group. Specifically, policy makers must pay particular attention to barriers beyond initial enrollment fees and consider broader systemic issues of health infrastructure, distance and costs of transportation to health services, social support and prevention mechanisms, and yearly renewal fees.

Our findings bode well for Ghana’s National Ageing Policy developed in 2010 which has an overarching aim of ensuring the socio-economic and cultural integration of the elderly in the Ghanaian society and also their full participation in the national development process (Government of Ghana 2010). Disparities in health insurance coverage based on wealth status identified in this study among older Ghanaians underlines the urgent need for implementing the National Ageing Policy. It is noteworthy that an important aspect of the policy refers to reducing socio-economic inequality and poverty among the elderly as these have implications for accessing health care through the NHIS. Government must improve and develop comprehensive pension schemes, one that captures not only those in the formal sectors of the economy but also even others in the informal sector. It is also important for policy to eliminate discriminatory practices that prevent the elderly from engaging actively in economic activities as these have implications for NHIS enrolment.

While this study presents important findings, certain limitations exist. The study relies on the first wave of SAGE data, which is cross-sectional, and as a result causal links cannot be established from these findings. Further, the analysis did not control for distance to health facility or health insurance registration locations, as this information was unavailable in the data. However, the findings are important as this study is one of the few to contribute to debates on ageing and health insurance coverage in Ghana and sub-Saharan Africa using large scale data. Given the projected growth rate of Africa’s ageing population and associated implications (Aboderin 2012; Lancet 2012; United Nations: Department of Social and Economic Affairs 2013), it becomes crucial that countries seek to provide adequate and accessible health care for ageing populations. Thus, it is imperative that governments implement appropriate health policies and services to meet demographic needs in changing populations. Ghana’s NHIS and its exemption policy for vulnerable groups, including the elderly is an important step in this policy area which remains nascent or missing in much of SSA.

References

Aboderin, I. (2012). Global poverty, inequalities and ageing in sub-Saharan Africa: A focus for policy and scholarship. Journal of Population Ageing, 5(2), 87–90. doi:10.1007/s12062-012-9064-x.

Agyepong, I. A., & Adjei, S. (2008). Public social policy development and implementation: A case study of the Ghana National Health Insurance scheme. Health Policy Plan, 23(2), 150–160. doi:10.1093/heapol/czn002.

Ahadzie, W. D. (2009). Baseline survey to assess access of older people to health care, poverty initiatives, pensions and social grants in three regions of Ghana, Accra.

Altschuler, J. (2004). Meaning of housework and other unpaid responsibilities among older women. Journal of Women & Aging, 16(1–2), 143–159. doi:10.1300/J074v16n01_10.

Amin, R., Shah, N. M., & Becker, S. (2010). Socioeconomic factors differentiating maternal and child health-seeking behavior in rural Bangladesh: A cross-sectional analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health, 9, 9. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-9-9.

Amoako Johnson, F., Frempong-Ainguah, F., & Padmadas, S. S. (2015). Two decades of maternity care fee exemption policies in Ghana: Have they benefited the poor? Health Policy and Planning. doi:10.1093/heapol/czv017.

Andersen, R. M., & Newman, J. F. (1973). Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly: Health and Society. doi:10.2307/3349613.

Asenso-Okyere, W. K., Anum, A., Osei-Akoto, I., & Adukonu, A. (1998). Cost recovery in Ghana: Are there any changes in health care seeking behaviour? Health Policy and Planning, 13(2), 181–188.

Bastos, A., Casaca, S., Nunes, F., & Pereirinha, J. (2009). Women and poverty: A gender-sensitive approach. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(5), 764–778.

Beard, J., Biggs, S., Bloom, D. E., Fried, L. P., Hogan, P. R., Kalache, A., & Olshansky, S. J. (2012). Global Population Ageing: Peril or Promise? 148.

Biritwum, R., Mensah, G., Yawson, A., & Minicuci, N. (2013). Study on global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE). Wave, 1, 1–111.

Brady, D., & Kall, D. (2008). Nearly universal, but somewhat distinct: The feminization of poverty in affluent Western democracies, 1969–2000. Social Science Research, 37(3), 976–1007. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.07.001.

Crooks, D. (2009). Development and Testing of the Elderly Social Vulnerability Index (ESVI): A Composite Indicator to Measure Social Vulnerability in the Jamaican Elderly Population [PhD’s thesis] Miami, FL: Florida International University

Davidson, P. M., DiGiacomo, M., & McGrath, S. J. (2011). The feminization of aging: How will this impact on health outcomes and services? Health Care for Women International, 32(12), 1031–1045. doi:10.1080/07399332.2011.610539.

Derbile, E. K., & Van Der Geest, S. (2013). Repackaging exemptions under National Health Insurance in Ghana: How can access to care for the poor be improved? Health Policy and Planning, 28(6), 586–595. doi:10.1093/heapol/czs098.

Dixon, J., Tenkorang, E. Y., & Luginaah, I. (2011). Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme: Helping the poor or leaving them behind? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 29(6), 1102–1115. doi:10.1068/c1119r.

Dixon, J., Luginaah, I., & Mkandawire, P. (2014a). The National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana’s upper West Region: A gendered perspective of insurance acquisition in a resource-poor setting. Social Science & Medicine, 122, 103–112. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.028.

Dixon, J., Luginaah, I. N., & Mkandawire, P. (2014b). Gendered inequalities within Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme: Are poor women being penalized with a late renewal policy? Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 25(3), 1005–1020. doi:10.1353/hpu.2014.0122.

Dixon, J., Tenkorang, E. Y., Luginaah, I. N., Kuuire, V. Z., & Boateng, G. O. (2014c). National Health Insurance Scheme enrolment and antenatal care among women in Ghana: Is there any relationship? Tropical Medicine & International Health, 19(1), 98–106.

Gajate-garrido, G., & Owusua, R. (2013). The National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana Implementation Challenges and Proposed Solutions.

Gelberg, L., Andersen, R. M., & Leake, B. D. (2000). The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: Application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research, 34(6), 1273–1302.

Gerdle, B., Björk, J., Henriksson, C., & Bengtsson, A. (2004). Prevalence of current and chronic pain and their influences upon work and healthcare-seeking: A population study. Journal of Rheumatology, 31(7), 1399–1406.

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2013). Population & housing census Report: The elderly in Ghana.

Gnawali, D. P., Pokhrel, S., Sié, A., Sanon, M., De Allegri, M., Souares, A., et al. (2009). The effect of community-based health insurance on the utilization of modern health care services: Evidence from Burkina Faso. Health Policy, 90(2–3), 214–222. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.09.015.

Government of Ghana (2010). National ageing policy: Ageing with security and dignity. Accra-Ghana.

Gyimah, S. O., Takyi, B. K., & Addai, I. (2006). Challenges to the reproductive health need of African women: On religion and maternal health utlilization in Ghana. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 62(12), 2930–44.

HelpAge-International. (2008). Older people in Africa: A forgotten generation.

ILO. (2014). World Social Protection Report 2014–2015 building economic recovery, inclusive development and a social justice.

Issahaku, P. A., & Neysmith, S. (2013). Policy implications of population ageing in West Africa. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 33(3/4), 186–202.

James, C. D., Hanson, K., McPake, B., Balabanova, D., Gwatkin, D., Hopwood, I., et al. (2006). To retain or remove user fees? Reflection on the current deabte in low- and middle-income countries. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 5(3), 137–153. doi:10.2165/00148365-200605030-00001.

Jehu-Appiah, C., Aryeetey, G., Spaan, E., de Hoop, T., Agyepong, I., & Baltussen, R. (2011). Equity aspects of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana: Who is enrolling, who is not and why? Social Science and Medicine, 72(2), 157–165. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.025.

Jehu-Appiah, C., Aryeetey, G., Agyepong, I., Spaan, E., & Baltussen, R. (2012). Household perceptions and their implications for enrolment in the National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana. Health Policy and Planning, 27(3), 222–233. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr032.

Jowett, M., Deolalikar, a, & Martinsson, P. (2004). Health insurance and treatment seeking behaviour: Evidence from a low income country. Health Economics, 13(9), 845–857.

Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S., & Kim, D. (2008). Social capital and health: A decade of progress and beyond. In I. Kawachi, S. V. Subramanian, & D. Kim (Eds.), Social capital and health (pp. 1–26). New York: Springer.

Kuuire, V. Z., Bisung, E., Rishworth, A., Dixon, J., & Luginaah, I. (2015). Health-seeking behaviour during times of illness: A study among adults in a resource poor setting in Ghana. Journal of Public Health. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdv176.

Lancet, T. (2012). A manifesto for the world we want. The Lancet, 380(9857), 1881. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62092-3.

Laporte, A., Nauenberg, E., & Shen, L. (2008). Aging, social capital, and health care utilization in Canada. Health Economics, Policy, and Law, 3(Pt 4), 393–411. doi:10.1017/S1744133108004568.

Lei, X., & Lin, W. (2009). The New Cooperative Medical Scheme in rural China: Does more coverage mean more service and better health? Health Economics. doi:10.1002/hec.1501.

Marmot, M., Friel, S., Bell, R., Houweling, T. A., Taylor, S., & Commission on Social Determinants of Health. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 372(9650), 1661–1669.

Mendis, S., Puska, P., & Norrving, B. (2011). Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Mensah, J., Oppong, J. R., & Schmidt, C. M. (2010). Ghana’s national health insurance scheme in the context of the health MDGs: An empirical evaluation using propensity score matching. Health Economics. doi:10.1002/hec.1633.

National Health Insurance Authority Ghana. (2011). National Health Insurance Authority Annual Report 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2015, from http://www.nhis.gov.gh/_Uploads/dbsAttachedFiles/1(1).pdf

Nyonator, F. (2012). What Ghana is doing for the health of the aged in the government/public and private sector? In Paper presented at the 65th World Health Assembly, Geneva

Nyonator, F., & Kutzin, J. (1999). Health for some? The effects of user fees in the Volta Region of Ghana. Health Policy and Planning, 14(4), 329–341. doi:10.1093/heapol/14.4.329.

Parmar, D., De Allegri, M., Savadogo, G., & Sauerborn, R. (2014a). Do community-based Health Insurance Schemes fulfil the promise of equity? A study from Burkina Faso. Health Policy and Planning, 29(1), 76–84. doi:10.1093/heapol/czs136.

Parmar, D., Williams, G., Dkhimi, F., Ndiaye, A., Asante, F. A., Arhinful, D. K., et al. (2014b). Enrolment of older people in social health protection programs in West Africa—does social exclusion play a part? Social Science & Medicine, 1982. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.011.

Ramlagan, S., Peltzer, K., & Phaswana-mafuya, N. (2013). Social capital and health among older adults in South Africa. BMC Geriatrics, 13(1), 1.

Sarpong, N., Loag, W., Fobil, J., Meyer, C. G., Adu-Sarkodie, Y., May, J., et al. (2010). National health insurance coverage and socio-economic status in a rural district of Ghana. Tropical Medicine and International Health. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02439.x.

Tenkorang, E. Y., & Owusu, Ga. (2010). Correlates of HIV testing among women in Ghana: Some evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys. AIDS Care, 22(3), 296–307.

United Nations, D. of E. and S. A. P. (2007). World Population Ageing 2007. Population New York

United Nations: Department of Social and Economic Affairs. (2013). World population prospects: The 2012 revision, DVD edition. Population Division 2013

Williams, K., & Kurina, L. (2002). The social structure, stress, and women’s health. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 45(4), 1099–1118.

World Health Organization. (2004). Towards age-friendly primary health care: WHO

World Health Organization. (2009). Women and health: Today’s evidence tomorrow’s agenda. Geneva: WHO

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuuire, V.Z., Tenkorang, E.Y., Rishworth, A. et al. Is the Pro-Poor Premium Exemption Policy of Ghana’s NHIS Reducing Disparities Among the Elderly?. Popul Res Policy Rev 36, 231–249 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9420-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9420-2