Abstract

Racial and ethnic diversity continues to spread to communities across the United States. Rather than focus on the residential patterns of specific minority or immigrant groups, this study examines changing patterns of White residential segregation in metropolitan America. Using data from the 1980 to 2010 decennial censuses, we calculate levels of White segregation using two common measures, analyze the effect of defining the White population in different ways, and, drawing upon the group threat theoretical perspective, we examine the metropolitan correlates of White segregation. We find that White segregation from others declined significantly from 1980 to 2010, regardless of the measure of segregation or the White population used. However, we find some evidence consistent with the group threat perspective, as White dissimilarity is higher in metro areas that are more diverse, and especially those with larger Black populations. Nevertheless, our findings indicate that Whites having been living in increasingly integrated neighborhoods over the last few decades, suggesting some easing of the historical color line.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Black–White color line has long been a central organizing feature of American communities (DuBois 1899; Myrdal 1944; Massey and Denton 1993). The segregation literature has described at length how White institutional racism historically served to perpetuate Black ghettos. Nevertheless, American society has changed in some important ways over the past few decades. The Civil Rights movement overturned the legal framework that supported the unequal treatment of Blacks. There are signs that discrimination in the housing market has declined somewhat, as have blatantly racist White attitudes. Together, these have helped produce moderate declines in Black–White segregation since the 1960s (Cutler et al. 1999; Iceland et al. 2002; Ross and Turner 2005). Multiethnic perspectives on segregation have also risen in prominence in recent years. In particular, the rapid growth of the Hispanic and Asian populations in the U.S. since the 1960s, in part in response to changes in immigration policy, has spurred increased interest in the residential patterns of these groups. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity may have reduced the stark Black–White divide in the U.S. (Frey and Farley 1996; Iceland 2004).

The growing interest in the well being of various minority groups has been accompanied by a relatively new focus of academic work—Whiteness studies (Kolchin 2002; Roediger 1991). One of the central themes in this work is the recognition that Whites use their race as a currency to protect their hegemony over minorities (Fine et al. 1997; Lipsitz 1998), and the threat posed by minorities is thought to increase as the size of the minority population increases (DeFina and Hannon 2009; Blalock 1957). Race is also seen as a social construct, and as such, the notion of who is “White” has changed over time. Some immigrant groups at the beginning of the twentieth century, for example, who were initially considered racially distinct outsiders (e.g., Jews and Italians), eventually became accepted as White ethnics over the course of the century—and thus part of the American “mainstream” (Alba and Nee 2003; Hout and Goldstein 1994; Roediger 2005). Similarly, there is considerable debate today about the extent to which Hispanics are becoming a racialized minority or are being absorbed into mainstream society (e.g., Itzigsohn et al. 2005; Michael and Timberlake 2008; Duncan and Trejo 2011).

The goal of our study is to shine a light on these issues by providing a detailed accounting of White residential segregation over three decades. We examine how such segregation varies according to the way we define the White population and we test whether the group threat perspective has become less salient over time as we might expect. In short, our analysis is guided by the following research questions:

-

1.

What were the patterns and trends in White segregation over the 1980–2010 period?

-

2.

How sensitive are these patterns to the manner in which we define “Whites”?

-

3.

To what extent is the variation in White segregation patterns consistent with the predictions of the group threat perspective over the time period?

Using data from the 1980 to 2010 decennial censuses, we calculate levels of White segregation in all U.S. metropolitan areas. We analyze the effect of defining the White population in different ways, use alternative reference groups, and examine the association between levels of White segregation and various group and metropolitan area characteristics, with a focus on those that represent the group threat perspective. These analyses provide new insights on how White residential patterns changed in recent decades and some of the factors that shaped them.

Background

Social scientists have long been interested in the residential patterns of immigrants and minority groups. Burgess (1925), for example, described how new immigrants lived in the central core near manufacturing employment, but how they moved to outer-ring areas as they became acculturated and their incomes rose. Many subsequent studies also focused on the strong residential Black–White divide in U.S. cities (Burgess 1928; Myrdal 1944). The Black–White color line was seen as being nearly impenetrable, reinforced by White racism, discrimination, and sometimes violence directed towards Blacks (Clark 1965; Massey and Denton 1993; Taeuber and Taeuber 1965).

Since the 1980s there has been a growing interest in the residential patterns of other groups—mainly Asians and Hispanics—following the increase in immigration from non-European countries. Results from these studies generally indicated that Black residential segregation in U.S. metropolitan areas is high in absolute terms, though it declined moderately in recent decades. In 2000, Hispanics were generally the next most highly segregated group, followed by Asians. Unlike Black segregation, Hispanic and Asian segregation has not declined markedly over the past three decades; by some measures, it has increased (Iceland 2002; Logan and Stults 2011).

Our study, rather than focusing on the segregation patterns of specific minority groups—as is most common in the segregation literature—directly examines White residential segregation patterns and their correlates. Only a small number of studies have reported White segregation indexes (i.e., the segregation of Whites from all Nonwhites), and even in these, White segregation was not the focal point (Iceland 2004; Fischer et al. 2004).

One theoretical approach that could help explain White residential patterns is the group threat perspective, which is in many ways an extension of the place stratification perspective frequently invoked in past studies of segregation. According to place stratification, racially motivated residential preferences and discrimination reinforce segregation in the United States. Whites continually seek to defend White privilege by maintaining the homogeneity of their neighborhoods—a theme also emphasized in research on Whiteness (Lipsitz 1998; MacMullan 2009). Past research on racial preferences has indicated that ethnic groups often show strong desires to live in neighborhoods where their own group is highly represented, and often avoid other ethnic neighborhoods. However, Whites tend to show the strongest avoidance behavior, especially of African Americans, even when controlling for the socioeconomic characteristics of the other groups in the neighborhood (Bobo and Zubrinsky 1996; Emerson et al. 2001; Krysan and Farley 2002; Krysan et al. 2009; Swaroop and Krysan 2011). Some of the more common discriminatory practices in the post-Civil Rights era included the geographic steering by real estate agents of racial groups to neighborhoods populated mainly by their own group and minorities being shown fewer properties than Whites (Bullard 2007; Goering and Wienk 1996; Meyer 2000; Yinger 1995).

The group threat perspective, like place stratification, highlights the importance of prejudice and discrimination; however the former approach emphasizes that minorities are perceived to pose a larger “threat” to Whites in areas where they comprise a larger proportion of the population. As succinctly stated by Quillian (1996: p. 820), “prejudice is in part a response to feelings that certain prerogatives believed to belong to the dominant racial group are under threat by members of the subordinate group.” While the size of the minority group is not the only possible source of group threat, a number of studies have indicated that it is positively related to prejudice and discrimination (Blalock 1956, 1957; Fossett and Kielcolt 1989; Giles and Evans 1985; Pettigrew 1959). Indeed, the racial group threat hypothesis is consistent with the finding that Black–White segregation increased in northern metropolitan areas in the first decades of the twentieth century as the Northern Black population swelled (Bullard 2007; Cutler et al. 1999; Lieberson 1980; Taeuber and Taeuber 1965). Recent studies have also found that minority segregation from Whites is positively associated with minority group representation in a given area (DeFina and Hannon 2009; Lichter et al. 2010; Logan et al. 2004).

While there are theoretical and empirical reasons to believe that White avoidance of minorities intensifies as minority populations grow, little research (that we are aware of) examines changes in this relationship over time. There are several reasons to think the salience of group threat and the discrimination underlying the place stratification perspective has declined. The proportion of Whites holding blatantly racist attitudes has dropped considerably over the decades according to public opinion polls (Pager 2008). This does not provide definitive proof that attitudes have changed, as people may just be less likely to express socially undesirable opinions to survey researchers. Other research, however, indicates that Whites have been increasingly willing to remain in their neighborhoods as African Americans enter, and that multiracial neighborhoods have become more stable (Ellen 2007; Farley et al. 1994; Logan and Zhang 2010). Housing audit studies have also documented that discrimination in the housing market has declined somewhat in recent years (Ross and Turner 2005). Our study is thus particularly concerned with trends in White segregation and whether the significance of race in determining these trends has gradually diminished.

Defining the White Population

In addition to looking at the correlates of White segregation, this study examines the extent to which patterns of segregation vary by how the White population is defined. Racial and ethnic group delineations are rarely static and have changed considerably over time (Alba 2009). The most common definition of the White population in segregation research, and in most other studies concerned with race, is to include in the category those who are “non-Hispanic White” (e.g., Fischer et al. 2004; Logan et al. 2004; Massey and Denton 1993). The underlying notion is that Hispanics are a distinct and disadvantaged minority group, which is reflected in their treatment by the privileged White majority as an outgroup (Itzigsohn et al. 2005; Michael and Timberlake 2008). From this angle, Hispanics are probably best viewed not as an ethnic group (as in the Census) but rather as a racial one (Hitlin et al. 2007). Hispanics share a culture, often live in tightly-knitted ethnic communities, and are viewed and treated by others—such as through discriminatory actions—in similar ways (Oropesa and Jensen 2010). This in turn reinforces their distinct Hispanic identity.

However, it could be that lighter-skinned Hispanics in particular experience less discrimination than Blacks and other darker-skinned Hispanics, and may be more likely to enter the majority White mainstream (Duncan and Trejo 2011; Frank et al. 2010; Golash-Boza and Darity 2008). In this way the boundaries of Whiteness may blur or expand over time, as occurred for Eastern and Southern European immigrants in the twentieth century (Alba 2009; Roediger 2005; Waters 1990). Duncan and Trejo (2011) note that by the third generation, many people of Latin American origin (e.g., one of their grandparents were born in Mexico) no longer identify as Hispanic, which is positively correlated with socioeconomic status. The implication here is that Hispanics who mark the “White” category on the census form are providing meaningful information about their identification, given the diversity of responses to the race question. In fact, many Hispanics explicitly report that they are “some other race,” rather than White, Black, Asian, or American-Indian. According to the 2010 census, 53 % of the Hispanic population identified as White, 3 % identified as Black, 37 % identified as “some other race,” 6 % identified with two or more races, and the small remainder chose other categories (Humes et al. 2011).

At the same time, a broader definition of the White population might display lower levels of segregation from Nonwhites, as those towards the “perimeter” of the White group boundary (e.g., White Hispanics) may be less averse or have some affinity with outgroup members. Previous research has indicated relatively low levels of segregation between White Hispanics and Hispanics who choose a different racial identity (Iceland and Nelson 2008). Here we do not assert that White Hispanics should necessarily be counted solely as White. Rather, we investigate the extent to which patterns and trends in White segregation vary when using two plausible alternative approaches to defining the White population.

In summary, our study builds on previous research of racial/ethnic residential segregation by focusing on three related issues. First, we update previous work on segregation with the latest decennial (2010) data with a focus on patterns and trends in White segregation from others. Second, given the general debate in the literature on racial identity and racial group categories in surveys, our examination of the sensitivity of using different “White” definitions is important and novel. Third, our look at group threat places our analysis of White segregation in a theoretically relevant context; no previous study on segregation has looked at the effect of group threat over time. In terms of specific theoretical expectations, according to the group threat perspective, more diverse metropolitan areas will have higher levels of White segregation. We also examine whether group threat is best thought of as White aversion to all Nonwhites or to Blacks in particular, as the racial preferences literature points to greater White antipathy toward Blacks than other groups (Charles 2006).

Our findings will also have theoretical implications for discerning the trajectory of the American color line. Whereas the traditional divide in American society has been between Whites and others, some argue that the more salient divide today is between Blacks and others (Lee and Bean 2010; Yancy 2003). By gauging trends in White segregation and the magnitude and changing effect of group threat, our results will suggest whether the residential patterns among Whites are converging or diverging with patterns of other racial/ethnic groups over the 30-year period of our study.

Data and Methods

The data for this study come primarily from the 1980 to 2010 U.S. decennial censuses summary files. For our segregation calculations, we extract full-count (census summary file 1) data from the Longitudinal Tract Database (LTDB), which is a tool created by the US2010 project to normalize census tract boundaries from earlier years to 2010 tract boundaries (Logan et al. 2012). The benefit of this approach is that comparisons over time are unaffected by changes in tract boundaries from one census to the next. For our multivariate analyses, we create metropolitan area control variables using data from the 1980–2000 census summary file 3 data and the 2006–2010 American Community Survey (ACS) for the 2010 period.

Data on race and Hispanic origin in the U.S. decennial census are collected in two questions. The first question asks whether the person is of Hispanic origin or not. A second question asks about a person’s race, where response categories include White, Black, American-Indian, a number of Asian and Pacific Islander groups (e.g., Chinese), and some other race. The race and Hispanic origin questions have been asked in a fairly similar manner over the period, with the most important change occurring in 2000, when census respondents were permitted to choose more than one race. However, in 2000 and 2010, only 2.4 and 2.9 % of the population, respectively, chose more than one race (Humes et al. 2011).Footnote 1

Based on the way the data have been collected, our analyses use two definitions of the White population: (1) non-Hispanic Whites are people who identified as White alone in the race question and also indicated they were not of Hispanic origin; and (2) all Whites are people who identified as White alone in the race question, regardless of whether they indicated if they were of Hispanic origin or not. Figure 1 shows the proportion of the total metropolitan area population who identified as White using these definitions over the 1980–2010 period. It indicates that while all Whites comprised 82 % of the U.S. metropolitan population in our sample in 1980, by 2010 that figure was down to 70 %. The proportion of the 2010 population that is non-Hispanic White in our metropolitan sample is lower still at 61 %.

Residential segregation usually refers to the distribution of groups across neighborhoods within metropolitan areas. Metropolitan areas approximate labor and housing markets. According to 2009 Census Bureau metropolitan definitions, there are 366 metropolitan areas (each with a population of at least 50,000 people) that contain 84 % of the U.S. population. To ensure comparability over time, we use constant 2009 county-based metropolitan area definitions for the 1980–2010 period covered by this analysis. County boundaries change little over time.

We use census tracts to measure neighborhoods for several reasons. Census tracts generally have between 2,500 and 8,000 individuals, are defined with local input with the intention of representing neighborhoods, and undergo minor changes from census to census. Census tracts are also by far the unit most used in research on residential segregation (e.g., Logan et al. 2004; Massey and Denton 1993). Because the Census Bureau did not tract the entire U.S. until 1990, there are missing data for a small sample of tracts in 1980. Thus, our analysis includes up to 333 metropolitan areas in 1980 and 366 metropolitan areas in 1990, 2000, and 2010—only a relatively modest difference. We further restrict our analyses in all years to metropolitan areas with at least 1,000 members of both the White group of interest and the minority reference group, as segregation indexes for metropolitan areas with small group populations are less reliable than those with larger ones.Footnote 2 We conducted supplemental segregation analyses where we kept the number of metropolitan areas constant over the entire period. Patterns of White segregation are very similar whether we restrict the number of metropolitan areas or not. We show results with a non-constant set of metropolitan areas because the increase in metro areas better represents actual patterns of population change over the three decades.

We use the two most commonly used segregation measures in our analysis, dissimilarity and isolation (and in some instances a corollary measure—interaction). Dissimilarity (D) is a measure of evenness, which refers to the differential distribution of the subject population across neighborhoods in a metropolitan area. It ranges from 0 (complete integration) to 1 (complete segregation), and indicates the percentage of a group’s population that would have to change residence (and be replaced by the other group) for each neighborhood to have the same percentage of that group as the entire metropolitan area. We use the Nonwhite population as the reference group in many calculations. The Nonwhite population is the total population minus the White population, depending on which definition of the White population we use. Specifically, when analyzing the segregation of non-Hispanic Whites, the Nonwhite population consists of all people who did not identify as non-Hispanic White (i.e., Blacks, Asians, all Hispanics, American Indians, people of some other race, and multiracial individuals). When analyzing the segregation of all Whites (which includes White Hispanics), the reference Nonwhite group consists of all people who did not mark the White category alone on the census form. In other calculations, we also examine the segregation of Whites from specific racial/ethnic groups, including non-Hispanic Blacks, non-Hispanic Asians, Hispanics (when examining the segregation of non-Hispanic Whites) and those from other races (when looking at all Whites).Footnote 3 We thus use care in avoiding overlap between the group of interest and the reference group in our calculations.

The second index used in the analysis, isolation (Pxx), is the most widely used measure of exposure (one of the dimensions of segregation defined by Massey and Denton 1988). The isolation index indicates the average percentage of group members (of the group of interest) in the neighborhood where the typical group member lives. The index varies from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating the highest level of segregation. A White isolation score of 0.80 in a metropolitan area, for example, would indicate that the typical White individual lives in a neighborhood that is 80 % White. In some cases we use the interaction index, which is calculated in a similar manner as the isolation index and provides a measure of how much interaction Whites have with a specific reference group. When using the interaction index, a higher score indicates a greater propensity for interacting with that group.

When comparing the dissimilarity and isolation/interaction indexes, the dissimilarity index has the advantage of not being sensitive to the relative size of the groups in question. It merely provides information on how evenly members of groups are distributed across neighborhoods. In contrast, the isolation and interaction indexes are sensitive to the relative size of the group being studied. Other factors being equal, racial/ethnic groups with larger shares of the metro population will be more isolated than smaller ones simply because there are more co-ethnics present with which to share neighborhoods. For example, isolation is generally higher (and interaction with other groups lower) for Whites in the U.S. metropolitan areas with proportionally many Whites (e.g., Salt Lake City) rather than ones with fewer Whites (e.g., Los Angeles). The isolation and interaction indexes thus provide useful information on the extent to which a person of a particular ethnic group lives primarily with co-ethnics versus other groups.

We begin by calculating the segregation indexes for Whites by definition of the White population and year. Then we conduct a detailed examination of the metropolitan correlates with White segregation using random-effects regression models. We investigate the association between White segregation and minority group threat with two sets of racial composition variables: (1) overall racial/ethnic diversity, and (2) specific racial/ethnic group composition.Footnote 4 Metropolitan diversity is measured by the entropy index. This index measures how equally members of a population are spread across categories or groups on some variable of interest. Like segregation indexes, the entropy score ranges from 0 (where the entire population consists of one group) to 1 (when all groups are of equal size). When non-Hispanic Whites are considered we use a 5-group index (non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, non-Hispanic Asians, non-Hispanic others, and Hispanics), while we use a 3-group index (Whites, Blacks, all others) when all Whites are considered.

The racial/ethnic categories we use when looking at White segregation from specific groups include non-Hispanic Blacks, non-Hispanic Asians (except in 1980, when we use all Asians), and Hispanics when examining non-Hispanic Whites, and all Blacks, all Asians, and all others when examining all Whites. Since the isolation index is computationally affected by the relative size of the different groups in question, we test the group threat perspective by focusing on the association between group composition and dissimilarity.

We model the association between group threat and White dissimilarity over time with a series of random-effects regression models. Taking advantage of our time series data structure, we pool all years of metropolitan-level data and include dummy variables for year (i.e., 1990, 2000, and 2010—with 1980 as the omitted year) to capture the general trend in White segregation over time. We also interact these year dummy variables with diversity indexes and racial composition variables to detect whether the extent of group threat has changed over the last three decades. Our random-effects modeling strategy is superior to standard OLS because it captures both within- and between-metropolitan level variation in the effects of our metropolitan correlates on White segregation patterns.Footnote 5

Finally, we include a number of ecological control variables in our multivariate analysis that have been used in several past segregation studies (e.g., Frey and Farley 1996; Logan et al. 2004; Wilkes and Iceland 2004). While these controls are not the focus of our study, we include them because of their potential to confound the effect of group threat. These include census region, metropolitan area population size, proportion of the civilian labor force that is in manufacturing and government, proportion of the labor force that is in the military, proportion of the population that is age 65 and older, proportion of the population aged 16–19 that has dropped out of high school, proportion of housing units that were built in the past 10 years,Footnote 6 proportion of occupied housing units that are owned, the proportion of the metropolitan area population in the suburbs, and the ratio of the average household income of Whites to that of the minority reference group.

Results

We begin with a comparison of White segregation trends with those of other racial and ethnic groups over the 1980 to 2010 period. In all calculations the reference group consists of those not of the group of interest (e.g., White–Nonwhite segregation, Black–Nonblack segregation, etc.). Later, we also look at the segregation of Whites from specific groups, as there may of course be considerable variation across them. Mean segregation scores are weighted by the size of the metropolitan population of the racial/ethnic group of interest. As such, segregation scores provide information on the levels of segregation experienced by the typical metropolitan individual of the racial/ethnic group of interest.

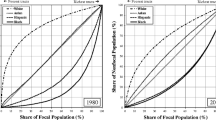

Figure 2 shows that the dissimilarity of all Whites (which includes White Hispanics) declined substantially over the period, from 0.58 in 1980 to 0.41 in 2010. The dissimilarity of non-Hispanic Whites in 2010 was only modestly higher at 0.45. One rather striking finding is that by 2010, segregation levels of Whites, Hispanics, and Asians have nearly converged, as the segregation of Asians and Hispanics from nongroup members held more or less steady since 1980 (increasing slightly among Asian and declining among Hispanics). Moreover, the absolute levels of segregation are in the moderate range, following the general rule of thumb that dissimilarity scores above 0.6 are considered high, those between 0.3 and 0.6 are moderate, and below 0.3 are low (Massey and Denton 1993). Black–Nonblack segregation declined steadily over the three decades, from 0.71 in 1980 to 0.55 in 2010, but remained above that of the other groups. The general descriptive trends are consistent with the declining significance of race among Whites (and Blacks) in shaping their residential patterns.

Figure 3 shows trends in isolation for the same set of groups over the period. As expected, Whites stand out as being considerably more isolated than any other group. The 0.79 score for all Whites in 2010 indicates that the typical White individual lived in a neighborhood that was 79 % White. This figure is down from 90 % in 1980, indicating that, consistent with other analyses, Whites live in more diverse neighborhoods than before (Logan and Zhang 2010). Isolation is slightly lower for non-Hispanic Whites (0.75 in 2010), which mainly reflects the relative size of the two White groups (holding other factors constant, larger groups tend to me more isolated).

Among other groups, we see that Black isolation declined steadily over the period (even though the relative size of the Black population in the U.S. has remained stable), from 0.61 in 1980 to 0.46 in 2010. This indicates that the typical African American no longer lives in a neighborhood that is majority Black. Black isolation levels have virtually converged with Hispanic isolation levels, in part reflecting the similarity in the size of the two groups, given the growth in the Hispanic population in recent decades. Asian isolation has increased steadily, but remains well below that of other groups.

Table 1 shows the dissimilarity of Whites from specific racial/ethnic minority groups from 1980 to 2010. The table suggests that declines in White segregation shown in Fig. 2 were particularly fueled by declines in White segregation from Blacks. For example, the segregation of non-Hispanic Whites from Blacks declined from 0.70 in 1980 to 0.57 in 2010. Segregation from Asians increased slightly from 1980 to 2000 and changed little in the 2000s, while segregation from Hispanics remained fairly stable over the period, even with continued high levels of immigration. Although the segregation patterns of all Whites are similar to those of non-Hispanic Whites, the declines experienced by the former are more pronounced. This suggests that the social distance between non-Hispanics Whites and others is somewhat higher than among White Hispanics, who may be less averse to living near other minority groups. Alternatively, it could mainly reflect that White Hispanics are more likely to live near other Hispanics than non-Hispanic Whites (Iceland and Nelson 2008).

Table 2 shows White exposure to specific groups, using the interaction index (note that White exposure to Nonwhites is the same as the isolation index shown in Fig. 2). Here we see that White exposure to all other groups has gradually increased over the decades. For example, in 1980 the typical non-Hispanic White individual lived in a neighborhood that was 88 % White, 5 % Black, 2 % Asian, and 5 % Hispanic. By 2010, the exposure to Blacks, Asians, and Hispanics increased to 7 %, 4 %, and 10 %, respectively. The same general pattern holds for all Whites as well.

Multivariate Analyses

We now examine the correlates of White segregation by using random-effects regression models that include pooled segregation scores from each year (1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010) and testing the predictions of the group threat perspective. According to this perspective, White segregation will be higher in metropolitan areas that are more racially and ethnically diverse. We present separate models for non-Hispanic Whites and all Whites, as this allows us to investigate whether the metropolitan correlates of White segregation differ by the definition of the White population used. The means and standard deviations of our metropolitan variables, including diversity and racial composition, are listed in Table 3. Briefly, racial/ethnic diversity and the shares of minority groups in metropolitan areas increased steadily since 1980. In addition, metropolitan areas experienced declines in manufacturing employment, increases in population, greater suburbanization, and declines in the proportion of young adults who are high school dropouts, among other changes shown in the table.

Table 4 shows random-effects regression results for White–Nonwhite segregation using racial/ethnic diversity (entropy score) to test group threat. As mentioned earlier, we only look at the relationship between this variable and dissimilarity, given the aforementioned limitations of the isolation index for examining this issue. Models include year dummy variables and diversity-year interactions to see if the effect of diversity varied over time. Results using the dissimilarity index indicate that White segregation was lower in 2000 and 2010 than in 1980 (the 1990 coefficient was not significant). The positive and significant coefficient for the diversity variable indicates that, consistent with group threat, metropolitan areas with more diversity tend to have higher levels of White–Nonwhite segregation. However, the negative, and in many cases significant, interaction terms indicate that the effect of group threat generally declined over time. That is, diversity tends to be less strongly associated with White segregation in later years than it was in 1980.

The effects of most variables do not differ much according to how the White population is defined in a given year.Footnote 7 Among the ecological variables, we see that larger metropolitan areas tend to have higher levels of White–Nonwhite segregation, while those with more recent housing construction have lower levels of White–Nonwhite segregation. These correlates of White segregation are quite similar to those found in other research on Black segregation (Timberlake and Iceland 2007). In addition, metro areas with higher rates of homeownership and a greater proportion of the population employed by the government have higher White segregation, while those located in the West and South (compared to the Northeast) and with relatively more employment in the military have significantly lower segregation. Metro areas with higher White-to-Nonwhite income ratios (i.e., a greater disparity in income, since Whites earn more on average than minorities) have greater White segregation—supporting the notion that income differences between groups matter (Iceland and Wilkes 2006).

In Table 5, we examine the issue of group threat in more detail by looking at how the relative presence of specific racial/ethnic groups affects White-minority segregation. This table presents random-effects models where we include the proportion of each minority group where the dependent variable is the segregation of Whites from that particular group. For example, in the first column of results, the dependent variable is non-Hispanic White—non-Hispanic Black dissimilarity, and the key independent variable is the proportion of the metropolitan area population that is non-Hispanic Black. Consistent with the diversity findings, White–Black segregation (regardless of how we define the White population) is higher in metropolitan areas with relatively large Black populations. While White–Black segregation is considerably lower in 2010 than in 1980 (as represented by the year dummy variables), the effect of percent Black remains fairly stable over time (as indicated by the nonsignificant interaction terms). If anything, the group threat effect was slightly higher in 2010 than in 1980. It is not clear why this might be the case, though it could reflect the fact that high levels of White–Black segregation have been slower to decline in Northeastern and Midwestern metropolitan areas with large Black populations than metropolitan areas in other regions. Although our regression models control for broad regional categories, they may not pick up the full variation in metropolitan patterns of differential decline in segregation.

Metropolitan areas with a higher proportion of Asians tend to have higher White-Asian segregation. Such metro areas may have high levels of immigration where Asian immigrants are buttressing immigrant enclaves (Iceland 2004). The proportion Asian-year interaction terms are for the most part not significant, indicating that the effect of group threat where Asians are concerned has not changed over time. Finally, the last set of models includes variables for proportion Hispanic (when considering non-Hispanic White segregation), and proportion all other races (when considering all White segregation). We find that, consistent with group threat, that the relative presence of Hispanics and other races are positively associated with White-Hispanic and White-Other segregation. However, the effect of percent Hispanic and percent other race is considerably smaller in 2010 than in 1980, indicating a declining effect of minority group presence on White segregation.

Conclusion

This study examined patterns and trends of White residential segregation, the sensitivity of these patterns to the manner in which we defined the White population, and the extent to which these patterns are consistent with the group threat perspective. We found that White segregation from non-Whites declined significantly over the 1980–2010 period, regardless of the measure used. Most of this was driven by declines in White–Black segregation in particular, as White dissimilarity from Hispanics and Asians changed relatively little in recent decades. The patterns and trends were similar for the White population defined in different ways. For instance, compared to all Whites, non-Hispanic Whites were slightly more segregated (according to the dissimilarity index) from non-Whites, but were slightly less isolated.

Overall, race clearly plays an important role in White residential patterns, and especially in the early time periods. In 1980, for example, White–Nonwhite dissimilarity stood at 0.58—very near the 0.6 rule-of-thumb threshold of very high segregation (Massey and Denton 1993). Numbers in this range indicate that racial segregation is much higher than residential segregation along other demographic dimensions, such as income, age, and other life course variables (White 1987). This is consistent with the findings of the racial residential preferences literature, where Whites seek to avoid minority neighbors, and Black neighbors in particular (Charles 2003; Krysan et al. 2009), and housing audit studies that indicate discrimination against minority home-seekers in housing market transactions (Ross and Turner 2005). Likewise, this suggests, as emphasized in Whiteness studies, that Whites use race as a currency to protect their neighborhoods and thus their privilege, as many resources (e.g., schools) are locally based (Lipsitz 1998; Roediger 2005).

At the same time, the salience of these race-based perspectives has likely declined over time, as indicated by significant reductions in White–Nonwhite (and especially White–Black) segregation. By 2010, White segregation from Nonwhites was in the .41–.45 range (depending on the definition of the White population used), which falls well within the moderate range of segregation (.3 to .6). Notably, the segregation of Whites, Asians, and Hispanics from all nongroup members have converged over time, such that by 2010 there is little difference in the levels of dissimilarity between each of the groups. Blacks remain the most segregated group, though Black dissimilarity from others has fallen substantially since 1980 as well. These declines are in line with evidence suggesting that Whites are less likely to express prejudicial attitudes than they used to, and that Blacks are less likely to experience discrimination in the housing market (Pager 2008; Ross and Turner 2005).

However, as expected, White isolation from others is considerably higher than the isolation experienced by other racial/ethnic groups. In other words, Whites continue to live in predominately White neighborhoods, while minority groups live in areas characterized by more diversity. This reflects the relatively large size of the White population, though White isolation has declined gradually over the past 30 years. Whereas in 1980 Whites tended to live in neighborhoods that were overwhelmingly White (about 90 %), by 2010 the typical White individual lived in a neighborhood that was on average 75–79 % White.

Consistent with some previous work (Defina and Hannon 2009), our analysis provided support for the group threat perspective. Specifically, we found that White dissimilarity was higher in metro areas with higher diversity and in those with larger specific Nonwhite populations (Blacks, Asians, and Hispanics) than in more racially homogenous metro areas. Nevertheless, the magnitude of group threat, as represented by a general measure of diversity, has generally declined over time. When specific racial/ethnic groups are examined, group threat has also declined for White-Hispanic segregation. Thus, the factors that might have served to reduce White segregation overall may also be mitigating the effect of group threat. However, our results indicate that the effect of the relative presence of Blacks has not declined over time. This could reflect the slower decline of segregation in metropolitan areas with a high representation of Blacks (e.g., Chicago, Detroit, and New York) and continued avoidance of Blacks by Whites.

Our analyses indicated that White segregation patterns, trends, and correlates were not especially sensitive to the definition of the White population used. The broader question is: whom should we consider “White” when describing White residential patterns? As noted earlier, the traditional reference group in segregation calculations has been non-Hispanic Whites. Hispanics are commonly seen as a meaningful panethnic group and there is considerable research aimed at ascertaining Hispanic well-being. However, it is not clear if this should preclude Hispanics who explicitly identify as White in surveys from also being considered as part of the White population when the latter is the object of study. People often have multiple identities (e.g., Black and Dominican, White and German, Asian and Filipino) and could thus fall into different analytical categories, depending on the goal of a particular study (Waters 1990, 2000).

There is considerable debate on whether Hispanics should be viewed as a racialized minority or an ethnic group that may eventually experience upward mobility and integration with the White mainstream. Some hold that a shared Hispanic culture, persisting ethnic residential communities, and Hispanics’ exposure to prejudice and discrimination at the hands of Whites and other groups will reinforce Hispanic identity for the foreseeable future (Itzigsohn et al. 2005; Michael and Timberlake 2008; Oropesa and Jensen 2010). However, others maintain that Hispanics—and especially light-skinned individuals—are experiencing upward mobility and may increasingly identify as White over time (Duncan and Trejo 2011; Frank et al. 2010; Golash-Boza and Darity 2008). An implication of the latter view is that to recode a purposeful race response in a survey (i.e., to recode Hispanics who reported being White as Nonwhite), as is commonly done, is not the best analytical practice.

Our study does not directly answer the question of how White Hispanics should be classified, but we do find that White segregation patterns do not vary that much by how one defines the White population, and that the effect of Hispanic group threat has ebbed over time. This suggests the possibility of additional boundary blurring between Whites and Hispanics in the future. To further pursue this issue, one possible avenue for future research would be to examine the residential patterns of Whites of different ethnic origins. How much variation is there across different ethnic groups among the panethnic White group and what explains this variation? Other research could delve further into the link between Hispanic identity and residential preferences. Census data may mask some measure of integration if a number of people of Latin American origins stop marking Hispanic on the census form over time.

Overall, despite some continued avoidance of Blacks and persistently high White–Black segregation particularly in metropolitan areas in the Northeast and Midwest (Iceland et al. 2013), we conclude that the White–Nonwhite color line has eased somewhat in recent decades. That is not to say that individuals are evenly distributed across neighborhoods in American communities or that ethnic distinctions have disappeared. Whites still tend to live in majority-White neighborhoods. Whites seem more adverse to minority groups in metropolitan areas where such groups are more prevalent, especially African Americans. Specific Hispanic and Asian (not to mention White and Black) ethnic groups, for example, still share a cultural heritage and often other sociodemographic traits. It is also unlikely that Asians will mark the “White” category on a census form in the near future—something that many twentieth century European immigrants and light-skinned Latin Americans have done. Rather, consistent with our finding that residential differences have narrowed in the 30-year period from 1980 to 2010, it appears that race as a construct shaping most facets of people’s lives has declined moderately in importance.

Notes

We conducted some analyses back to 1970. The challenge with using 1970 data is that one cannot distinguish between the “white” and “non-Hispanic white” population in census public use files. We also do not have data on the number of Asians in that year. These omissions mean that we cannot conduct many of our analyses with data from that year. The number of metropolitan areas in that year was also considerably smaller than in subsequent years. Overall, the declines in white segregation from nonwhites and from blacks we see from 1980 onward were evident in the 1970 to 1980 period as well.

Random factors and geocoding errors are more likely to play a large role in determining the settlement pattern of group members when fewer members are present, causing these indexes to contain greater volatility (Iceland et al. 2002).

For 1980 we use all Asians (and not non-Hispanic Asians) in this calculation because there was no public-use data available on Asians by Hispanic origin in that year. When examining all whites, other races in these calculations (which appear only in the last row in Tables 1, 2 only) includes individuals who are not white, black, or Asian. When examining non-Hispanic whites, other races include those who are not non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian, or Hispanic.

While most independent variables are calculated using the 2006–2010 ACS data, our racial composition variables are based on 2010 decennial data.

A significant Breusch-Pagan Lagrange multiplier test confirmed our use of random-effects models over simple OLS regression. We also ran fixed-effects models, which are focused on within-metropolitan variation and changes over time, and received very similar results that do not alter our conclusions about the association between diversity/racial composition and White segregation. Moreover, a random-effects approach provides the average within- and between-metropolitan effect, which we contend is more appropriate for answering our research questions.

We also considered using a variable indicating the proportion of housing built before 1950; the coefficient yielded similar conclusions as the proportion of housing built in the past 10 years.

Because the intercepts in the models are negative, a potential concern is that predicted probabilities might fall out of a reasonable range for dissimilarity (the index ranges from 0 to 1). Thus, we calculated predicted probabilities for the regressions and find that they all fall within 0 to 1 as expected.

References

Alba, R. (2009). Blurring the color line: The chance for a more integrated America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Alba, R., & Nee, V. (2003). Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Blalock, H. M. (1956). Economic discrimination and Negro increase. American Sociological Review, 21(5), 584–588.

Blalock, H. M. (1957). Percent non-White and discrimination in the south. American Sociological Review, 22(6), 667–682.

Bobo, L., & Zubrinsky, C. (1996). Attitudes toward residential integration: Perceived status differences, mere in-group preference, or racial prejudice? Social Forces, 74, 883–909.

Bullard, R. D. (2007). The Black metropolis in the era of sprawl. In R. D. Bullard (Ed.), The Black metropolis in the twenty-first century: race, power, and politics of place (pp. 17–40). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Burgess, E. W. (1925). The growth of the city: An introduction to a research project. In R. E. Park, E. W. Burgess, & R. D. McKensize (Eds.), The City (pp. 47–62). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Burgess, E. W. (1928). Residential segregation in American cities. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 140, 105–115.

Charles, C. Z. (2003). Dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annual Review of Sociology, 29(1), 167–207.

Charles, C. Z. (2006). Won’t you be my neighbor: Race, class, and residence in Los Angeles. New York: Russell Sage.

Clark, K. B. (1965). Dark ghetto: Dilemmas of social power. New York: Harper and Row.

Cutler, D. M., Glaeser, E. L., & Vigdor, J. L. (1999). The rise and decline of the American ghetto. Journal of Political Economy, 107(3), 455–506.

DeFina, R., & Hannon, L. (2009). Diversity, racial threat and metropolitan housing segregation. Social Forces, 881(1), 373–394.

DuBois, W. E. B. (1899). The Philadelphia Negro: A social study. Reprint (p. 1967). New York: Schocken.

Duncan, B., & Trejo, S. J. (2011). Tracking intergenerational progress for immigrant groups: The problem of ethnic attrition. The American Economic Review, 101(3), 603–608.

Ellen, I. G. (2007). How integrated did we become during the 1990s? In J. Goering (Ed.), Fragile rights within cities: Government, housing, and fairnes (pp. 123–141). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Emerson, M. O., Yancy, G., & Chai, K. J. (2001). Does race matter in residential segregation? exploring the preferences of White Americans. American Sociological Review, 66, 922–935.

Farley, R., Steeh, C., Krysan, M., Jackson, T., & Reeves, K. (1994). Stereotypes and segregation: Neighborhoods in the Detroit area. American Journal of Sociology, 100, 750–780.

Fine, M., Weis, L., Powell, L. C., & Wong, L. M. (1997). Preface. In M. Fine, L. Weis, L. C. Powell, & L. M. Wong (Eds.), Off White: Readings on race, power, and society (pp. v–xii). New York: Routledge.

Fischer, C. S., Stockmayer, G., Stiles, J., & Hout, M. (2004). Geographic levels and social dimensions of metropolitan segregation. Demography, 41, 37–60.

Fossett, M., & Kielcolt, K. J. (1989). The relative size of minority populations and White racial attitudes. Social Science Quarterly, 70(4), 820–835.

Frank, R., Akresh, I. R., & Lu, B. (2010). Latino immigrants and the U.S. racial order: How and where do they fit? American Sociological Review, 75(3), 378–401.

Frey, W. H., & Farley, R. (1996). Latino, asian, and Black segregation in U.S. metropolitan areas: Are multiethnic metros different? Demography, 33, 35–50.

Giles, M. W., & Evans, A. S. (1985). External threat, perceived threat, and group identity. Social Science Quarterly, 58, 412–417.

Goering, John M., & Wienk, Ron (Eds.), (1996). Mortgage lending, racial discrimination and federal policy. Washington: Urban Institute Press.

Golash-Boza, T., & Darity, W. (2008). ‘Latino racial choices: The effects of skin colour and discrimination on Latinos’ and Latinas’ racial self-identifications’. Ethnic & Racial Studies, 31, 899–934.

Hitlin, S., Scott Brown, J., & Elder, G. H. (2007). Measuring Latinos: Racial and ethnic classification and self-understandings. Social Forces, 86(2), 587–611.

Hout, M., & Goldstein,. J. R. (1994). How 4.5 million Irish immigrants became 40 million Irish Americans: Demographic and subjective aspects of the ethnic composition of White Americans. American Sociological Review, 59(1), 64–82.

Humes, K. R., Jones, N.A, Ramirez, R.R. (2011). Overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. Census 2010 Brief # C2010BR-02. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Iceland, J., Weinberg D.H., Steinmetz E. (2002). Racial and ethnic residential segregation in the United States: 1980–2000. U.S. Census Bureau, Census Special Report, CENSR-3. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Iceland, J. (2004). Beyond Black and White: Residential segregation in multiethnic America. Social Science Research, 33(2 (June)), 248–271.

Iceland, J., & Nelson, K. A. (2008). Hispanic segregation in metropolitan America: Exploring the multiple forms of spatial assimilation. American Sociological Review, 73(5), 741–765.

Iceland, J., Sharp, G., & Timberlake, J. M. (2013). Sun belt rising: Regional population change and the decline in Black residential segregation, 1970–2009. Demography, 50(1), 97–123.

Iceland, J., & Wilkes, R. (2006). Does socioeconomic status matter? Race, class, and residential segregation. Social Problems, 52(2), 248–273.

Itzigsohn, J., Giorguli, S., & Vazquez, O. (2005). Immigrant incorporation and racial identity: Racial self-identification among Dominican immigrants. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(1), 50–78.

Kolchin, P. (2002). Whiteness studies: The New history of race in America. The Journal of American History, 89(1), 154–173.

Krysan, Maria, Couper, Mick P., Farley, Reynolds, & Forman, Tyrone A. (2009). Does race matter in neighborhood preferences? Results from a video experiment. American Journal of Sociology, 115(2), 527–559.

Krysan, M., & Farley, R. (2002). The residential preferences of Blacks: Do they explain persistent segregation? Social Forces, 80(3), 937–980.

Lee, Jennifer, & Bean, Frank D. (2010). The diversity paradox: Immigration and the color line in twenty-first century America. New York: Russell Sage.

Lichter, D. T., Parisi, D., Taquino, M. C., & Grice, S. M. (2010). Residential segregation in new Hispanic destinations: Cities, suburbs, and rural communities compared. Social Science Research, 39, 215–230.

Lieberson, Stanley. (1980). A piece of the pie: Blacks and White immigrants since 1980. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lipsitz, George. (1998). The possessive investment in Whiteness: How White people profit from identity politics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Logan, J. R., Xu Z., Stults B. (2012). Interpolating US decennial census tract data from as early as 1970 to 2010: A longitudinal tract database. Professional Geographer. [forthcoming].

Logan J.R., Stults B. (2011). The persistence of segregation in the metropolis: New findings from the 2010 census. Census Brief prepared for Project US2010.

Logan, J. R., Stults, B. J., & Farley, R. (2004). Segregation of minorities in the metropolis: Two decades of change. Demography, 41(1), 1–22.

Logan, J. R., & Zhang, C. (2010). Global neighborhoods: New pathways to diversity and separation. American Journal of Sociology, 115(4), 1069–1109.

MacMullan, T. (2009). Habits of Whiteness: A pragmatist reconstruction. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. (1988). The dimensions of residential segregation. Social Forces, 67, 281–315.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Meyer, S. G. (2000). As long as they don’t move next door: Segregation and racial conflict in American neighborhoods. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Michael, J., & Timberlake, M. J. (2008). Are Latinos becoming White? Determinants of Latinos’ racial self-identification in the U.S. In C. A. Gallagher (Ed.), Racism in post-race America: New theories, new directions (pp. 107–122). Chapel Hill: Social Forces.

Myrdal, G. (1944). An American Dilemma: The Negro problem and modern democracy. Reprint, New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1996.

Oropesa, R. S., & Jensen, L. (2010). Dominican immigrants and discrimination in a new destination: The case of reading, Pennsylvania. City and Community, 9(3), 274–297.

Pager, D. (2008). The dynamics of discrimination. In A. C. Lin & D. R. Harris (Eds.), The colors of poverty: Why racial and ethnic disparities persist (pp. 21–51). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Pettigrew, T. (1959). Regional differences in anti-Negro prejudice. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59, 28–36.

Quillian, L. (1996). Group threat and regional change in attitudes toward African–Americans. American Journal of Sociology, 102(3), 816–860.

Roediger, D. R. (1991). The wages of Whiteness: Race and the making of the American working class. New York: Verso.

Roediger, D. R. (2005). Working toward Whiteness: How America’s immigrants became White. New York: Basic Books.

Ross, S. L., & Turner, M. A. (2005). Housing discrimination in metropolitan America: Explaining changes between 1989 and 2000. Social Problems, 52(2), 152–180.

Swaroop, S., & Krysan, M. (2011). The determinants of neighborhood satisfaction: Racial proxy revisited. Demography, 48(3), 1203–1229.

Taeuber, K. E., & Taeuber, A. F. (1965). Negroes in cities: Residential segregation and neighborhood change. Chicago: Aldine.

Timberlake, J. M., & Iceland, John. (2007). Change in racial and ethnic residential inequality in American Cities, 1970–2000. City & Community, 6, 335–365.

Waters, M. C. (1990). Ethnic options: Choosing identities in America. Berkeley: California University Press.

Waters, Mary C. (2000). Immigration, intermarriage, and the challenges of measuring racial/ethnic identities. American Journal of Public Health, 90(11), 1735–1737.

White, M. J. (1987). American neighborhoods and residential differentiation. New York: Russell Sage.

Wilkes, R., & Iceland, J. (2004). Hypersegregation in the twenty-first century: An update and analysis. Demography, 41(1), 23–36.

Yancy, G. (2003). Who is White? Latinos, Asians, and the New Black/Nonblack divide. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Yinger, J. (1995). Closed doors, opportunities lost: The continuing costs of housing discrimination. New York: Russell Sage.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Population Research Institute Center Grant, R24HD041025.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iceland, J., Sharp, G. White Residential Segregation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas: Conceptual Issues, Patterns, and Trends from the U.S. Census, 1980 to 2010. Popul Res Policy Rev 32, 663–686 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9277-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9277-6