Abstract

The present study addresses the issue of economic insecurity and its relationship with the reproductive plans of 5,358 Italian women in couples who have recently had their first child. Data were sourced from the ISTAT Sample Survey on Births, 2005 edition. This article’s originality lies in the conceptualization of economic insecurity and the investigation of its effects on fertility intentions. We propose to capture economic insecurity by considering both the insecurity associated to the two partners’ employment status and a variety of aspects that contribute to the household’s ability to cope with possible unpredictable future events. Then, we investigate whether and how economic insecurity shapes the fertility intentions of women over their entire reproductive life span. With specific respect to women who intend to have one additional child only, we also observe the effect of economic insecurity on their intention to give birth sooner (i.e., within the next 3 years) or later. Our data show the existence of a critical factor in the passage from the generic fertility intentions to the contingent plan to have a child in the next 3 years: only half of women with one child who intend to follow the two-child family model feel ready to plan to have a second child in the next 3 years. The study also reinforces an argument that is frequently made: fertility intentions over the entire lifetime are less conditioned upon contingent constraints, and are often more closely related to individual traits and/or preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The present study will address the issue of economic insecurity and its relationship with the reproductive plans of women with one child in Italy. In recent decades, Italy has witnessed a remarkable increase in (albeit still low) female labor market participation, together with the diffusion of low-paid jobs and of new flexible “nonstandard” patterns of employment and unemployment spells, especially among young people and women. At the same time, the country has experienced a persistently low level of fertility. The peculiarity of the Italian welfare state, centered on the family as the main social shock absorber and characterized by the difficult combination of female employment and family life, makes the study of the possible effects of economic insecurity on fertility plans even more relevant.

Using data from the Sample Survey on Births, carried out by Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) in 2005, this article focuses on women in couples who have recently had their first child. This choice is dictated by the fact that the fertility decline observed in Italy has not been associated with particularly high levels of childlessness or a sharp decline in the number of first births. Instead, the most dramatic declines have been in the second- and higher-order births (ISTAT 2003, 2006a).

In line with a large body of recent fertility research (e.g., Philipov 2009), which has increasingly acknowledged the need for drawing on social psychological theories, this study concentrates on fertility intentions, as we share the view that they are key determinants in the decision to have a child. The study looks separately at the factors associated with the quantum of fertility intentions, and then with their timing. First, it investigates whether women with one child plan to have zero, one or more additional children over their entire reproductive life span. Then, specific attention is devoted to women who intend to have one additional child only, looking at whether they intend to give birth sooner (i.e., within the next 3 years) or later. This article originally contributes to the existing literature by focusing not only on the traits of both partners’ occupational position which might increase the risk of economic hardship, but also on the resources available to the household for coping with potential economic losses. Furthermore, it investigates whether and how these factors shape the definitions of both the quantum and the timing of fertility intentions.

As the result of the transformations brought about by globalization, younger people, and women in particular, are exposed to increasingly precarious, lower-paid, and lower-quality employment (OECD 2002). Insecurity in working careers extends to other dimensions of life, and the related uncertainty about future prospects affects the way individuals balance their choices between work and family spheres. Several studies have looked at the possible pathways and mechanisms through which insecurity and uncertainty may affect childbearing (for a thorough and up-to-date review, see Sobotka et al. 2011). They mostly refer to two main alternative theories: the risk aversion theory (as discussed, with specific reference to family decision-making, by McDonald 2002) and the uncertainty reduction hypothesis (Friedman et al. 1994). The two theories share some common ground, insofar as they regard economic insecurity and the related future uncertainty as negative states that individuals will seek to avoid or reduce. Nevertheless, they postulate two opposing strategies that individuals might use to make their future prospects less uncertain.

Risk aversion theory derives from rational choice theory and new home economics (Becker 1960, 1965, 1981). According to this theory, in deciding whether to have a child, people make the considered calculation that the benefits of having an additional child outweigh the costs. Risk aversion theory adds the dimension of uncertainty to the decision-making process. Individuals may, in fact, have only a poor appreciation of the opportunities and costs associated with their choices as they consider the future. Therefore, when a person’s economic, social, or personal prospects are perceived to be uncertain, individual decision makers may be inclined to stay on the safe side, acting to avoid risk. In a situation of economic insecurity, risk aversion theory implies an investment in economic security (education, attachment to the labor force, savings) rather than in the insecurity that accompanies having children. McDonald (2002) also highlights the role of welfare systems in coping with market casualties. At a time when the safety once provided by welfare systems is under threat, risk-averse behaviors are even more likely to be adopted. The view that insecurity has a negative effect on family and fertility decision-making is shared by several scholars. Employment or economic insecurity reduces the likelihood of making long-term commitments (Clarkberg 1999; Oppenheimer 1988; Oppenheimer and Lewin 1997; Sennett 1998). Decisions that imply the acceptance of lifelong responsibilities, such as forming a union or having (further) children, may thus be postponed or even forgone (Adler 1997; Bernardi and Nazio 2005; De La Rica and Iza 2005; Tölke and Diewald 2003; Witte and Wagner 1995).

The theory of uncertainty reduction (Friedman et al. 1994) stems from the recognition that, even under conditions of great uncertainty, people continue to have children. Referring to the broader biographical uncertainty entailed by economic insecurity, it proposes an opposing model: individuals see life course choices that help in reducing their overall biographical uncertainty as particularly attractive. In this context, parenthood may be seen as a force that counteracts the uncertainty produced by precarious working conditions, leading couples to move toward the relative certainty that comes with having lifelong rights and obligations in relation to their children. Having children may therefore be regarded as an alternative life goal for those most affected by the uncertainty brought about by the globalization process. The idea that individuals may seek to reduce their overall biographical uncertainty by having children has been proposed in a number of recent studies looking at the relationship between economic insecurity and fertility. Although it is more often invoked in relation to the decision of becoming parents (among others, Bernardi et al. 2008; Kreyenfeld 2010; Tölke and Diewald 2003), some authors refer to the theory of uncertainty reduction also to frame the study of second-order births (Begall 2011; Klesment and Puur 2010). Indeed, while for most couples the major uncertainty arises when deciding whether to have the first child or not, we believe that the theory should not be discarded a priori when studying the intention of having the second child in the Italian context, where the transition to parenthood is invariably unquestioned, and the crucial decision rather concerns with the transition to the second birth.

However, rather than espousing one of these theories to the exclusion of the other, most authors have suggested that the relationship between insecurity and the likelihood of having a child may not be universal and unidirectional. In this respect, the recently developed theory of conjunctural action (Johnson-Hanks et al. 2011) provides a valuable theoretical orientation. According to this theory, similarities/differences in behaviors should be seen as a consequence of individuals filtering experiences and stimuli through similar/different (schematic and material) structures, and thus construing in similar/different ways their solutions to conjunctures. Structures also influence the conjunctures individuals may face, resulting in their uneven distribution across social groups and social space and over the life course. Thus, the adoption of risk-averse or, conversely, of uncertainty-reducing behavior could depend, among other things, upon the extent and type of this uncertainty, the socioeconomic characteristics of individuals, and the societal and institutional responses to uncertainty. As a matter of fact, it has been demonstrated that fertility decisions at times of economic insecurity are differentiated by individual characteristics, such as gender (Mills and Blossfeld 2005), age (Bernardi and Nazio 2005; Mills and Blossfeld 2005), the current number of children (Philipov et al. 2006; Vignoli et al. 2012; Vikat 2004), and membership in a given social group (e.g., Kreyenfeld 2010, with regard to educational level). Furthermore, economic insecurity has different effects on fertility preferences and/or intentions, their intended timing, or their realization (see, e.g., Perelli-Harris (2006) on the stronger effect on childbearing preferences than on outcomes; or Philipov et al. (2006) on the different effects on long- or short-term fertility intentions).

In addition, the above studies suggest that the observed effects are strongly context-dependent. As put forward by Mills and Blossfeld (2005), individual responses to the challenges and the threats imposed by the globalizing economy and increasing uncertainty about economic and social developments are moderated by institutional filters, such as the labor market, the educational system, and institutional and family welfare. Within the same context, however, an important intermediary factor between the individual and the societal response to insecurity is the availability of support from the individual’s social network (Bühler and Fratczak 2007; Philipov 2003; Philipov et al. 2006). Individuals’ rational decision-making under increasing uncertainty may thus differ widely across countries depending on the institutional setting, and within the same country depending on the social structure, as these factors determine the degree to which rising uncertainty affects individual lives.

The issue of economic insecurity and its relationship with reproductive intentions will be addressed in this article in relation to the cases of Italian women in couple who have recently had their first child. This article is structured as follows. The next section gives an overview of the Italian context. The object of the study and the research questions are outlined in the “Object of the Study and Research Questions” section. The “Data, Variables, and Methods” section is devoted to a description of the data, methods, and variables. The “Measuring Economic Insecurity” section specifically focuses on the measurement of economic insecurity. The “Results” section reports the results of the multivariate analysis. The sections that follow offer a general discussion of the study and its findings, before ending with some concluding remarks.

Fertility Patterns, the Labor Market, the Family, and the Welfare State: A Brief Overview of the Italian Scenario

We begin by framing the study of economic insecurity and fertility intentions within the Italian context. This section highlights the main features of the trends in fertility and the transformations in the labor market in recent decades. We then outline the salient traits of the Italian system of welfare. As has already been emphasized, family and fertility behaviors, labor market participation, and welfare regimes are deeply intertwined, and it is their interaction which produces the context in which individuals’ actions take place.

The fertility level of Italy is among the lowest in Europe. Starting in 1965, the total period fertility rate (TFR) decreased steadily to reach a low rate of 1.19 children per woman in 1995. Since then, a modest recovery was observed up to 2009, whereas in the latest years the TFR leveled out: according to the most recent ISTAT's estimates, the mean number of children per woman was 1.39 in 2011. The observed increase of period TFR is partly attributable to fertility recovery of older aged women and to the behavior of foreign women whose TFR exceeds that of native women (ISTAT 2012). The decline in fertility levels in recent decades has affected the mean size of Italian families to a considerable extent, as couples with only one child are becoming more and more common. Nevertheless, first-order births have been only partially affected by the fertility crisis: Italian women still show a high propensity to become mothers, even though they often have only one child (ISTAT 2006a). The lowest-low fertility patterns observed in Italy do not translate into very high levels of childlessness (ISTAT 2003). Thus, the sharp decline in fertility is not attributable to a refusal to procreate, but rather to less-frequent transitions to higher-order births (ISTAT 2006a).

At the same time, however, there is not much evidence of a change in the preferences of couples regarding the number of children they would like to have. According to ISTAT (2006b), the fertility intentions for partnered women aged 18–49 equal replacement level (TFR of 2.1), with no significant differences found across women’s birth cohorts. Hence, most women continue to prefer the familial model of a couple with two children.

In recent decades, Italy has also undergone profound social, economic, and legislative transformations that have had a major impact on labor market organization. The latter was traditionally characterized by low female activity rates, high unemployment rates among youths and the less-skilled workforce, the scarcity of part-time jobs, and low levels of active labor market participation among people aged 55–64. Geographical differences were also pronounced, and the informal economy was not negligible, particularly in the south. Furthermore, the fragmentation within the workforce was still high, as a significant degree of job protection for those in standard employment (the “insiders,” adopting Lindbeck and Snower’s (1989) terminology) led to the erection of high barriers that hindered a steady entry into the labor market for weaker groups (the “outsiders”).

Since the 1990s, in order to foster economic growth and to create greater occupational opportunities for the marginal and/or disadvantaged segments of the labor force, the wider use of the few existing nonstandard contractual forms has been promoted. In addition, new contractual forms, known as atypical contracts, have been progressively introduced, and have had a high degree of diffusion, particularly among the younger generations (for a critical review on this issue, e.g., Ferrera (2000) and Contini and Trivellato (2005)). According to ISTAT (2006c), the share of employees with temporary contracts in 2005 was equal to 14.7 for women and 10.5 for men. These figures, however, do not include other forms of nonstandard work, such as—for instance—employees with part-time contacts. In fact, a rather heterogeneous set of contractual forms fall under the umbrella of “atypical contracts,” differing with respect to their stability, work schedules, remuneration levels, career opportunities, maternity benefits, income guarantees, and access to (limited) unemployment and pension benefits. The link between flexibility and economic insecurity is thus not always straightforward, since flexible contracts may represent an individual choice, a temporary phase facilitating the transition to a standard occupation, or, conversely, the only opportunity to participate in the labor market. Empirical evidence proves that the latter situation is particularly common in Italy, where for more than 80 % of atypical workers, having a nonstandard contract is not a choice they made voluntarily, but is rather a situation they have accepted because they were unable to find more stable employment (Incagli and Rustichelli 2002). Furthermore, atypical workers are generally confined within a marginal market characterized by poor job quality in terms of social protection, stability, salaries, and the tasks performed (Barbieri and Scherer 2009). Finally, in order to properly assess the impact of job stability on people’s lives, it is important to look at the labor market participation of all of the members of a household. Compared to double-earner households in which both partners are in a standard form of employment, the most critical situations in terms of income security and social protection are those of double-earner households in which one or both partners has a nonstandard contract, or of single-earner families or lone-parent families, particularly if the only worker in the household holds a nonstandard work contract. According to ISTAT (2009a), households of the latter typologies represent in Italy a significant percentage of all households, and their numbers have been increasing.

Moving on now to sketch the salient traits of the welfare state, we adopt the categories developed by Esping-Andersen, who defined Italy as a country with a conservative welfare regime, in which most of the benefits provided by the state are tied to employment, and the private market provision of welfare is still marginal (Esping-Andersen 1990, 1999). This is particularly true for active and passive labor policies, such as entitlement to unemployment benefits or maternity pay. On the other hand, the health and the educational systems of Italy are characterized by a much higher degree of universalism (Barbieri and Scherer 2009; Ferrera 2000; Kolberg and Esping-Andersen 1991; Morlicchio et al. 2002).

Given the strong association between occupational status and access to the system of social protection, labor market deregulation is likely to have a significant impact on reproductive choices, especially as it affects the younger generations to a greater extent. Several scholars have suggested that, when flexible jobs are not well-paid and are less protected in terms of social measures, they are likely to depress fertility levels, rather than facilitate the combining of family and work (Livi Bacci 2001a; McDonald 2006; van Peer 2002).

Another defining trait of the conservative welfare regime, especially in Southern European countries, is its “familialistic” or “familistic” nature (Esping-Andersen 1999; Saraceno 1994). In other words, the features and responsibilities of the Italian model are deeply shaped by the conception of the family as the economic and caregiving unit: i.e., as the basic societal cell in which income and care are distributed among its members. This view implies that the state acts only when families are not able to meet their members’ needs (Ferrera 2000; Livi Bacci 2001b). This attitude nourishes a vicious circle, in which families do not rely on the state, and institutions are not particularly pressed to intervene (De Rose et al. 2008). In this context, the family (and, frequently, the extended family) too often not only assumes a fundamental caregiving role for grandchildren and other dependents, but also constitutes an important shock absorber when one of its members experiences unemployment episodes or a period of income reduction. The increasing flexibility of the labor market has exacerbated the situation, overloading families with even greater responsibilities. The detrimental impact that this status quo has been increasingly exerting on family and reproductive behaviors, and particularly on the expected and actual fertility of the younger generations, has been widely discussed in the last two decades. A recent comparative study on 12 European countries on the link between female labor participation and the fertility behavior of one-child women found that, where temporary jobs are more widespread, a substantial delay in second births is observed (Adsera 2011). As Esping-Andersen (1999) has emphasized, familialism often results in a low-fertility equilibrium. The high educational levels of women (and, consequently, their greater labor market attachment), combined with traditional gender roles in partnerships and inadequate family support measures, make female employment and children less compatible, and may push women to reduce their family size or even forgo having children (Blossfeld 1995; Fiori 2011; Pinnelli 2001; Pinnelli and Fiori 2008).

Finally, Southern European countries share another important feature that relates to homeownership. As Mulder and Billari (2010) pointed out, parallels may be drawn between welfare regimes and housing systems. Specifically, Mediterranean countries are all characterized by high levels of homeownership, poor access to mortgages, a small rental sector, and underdeveloped public housing policies. The link between fertility and the housing market has been widely studied (for a review, see Sobotka 2011): on the one hand, becoming a homeowner can compete with the cost of having additional children; on the other hand, the lack of affordable housing may delay childbearing or limit couples’ family size. In Italy, the difficulties in getting a mortgage are often overcome with the help of extended family members through inter vivos intergenerational transfers (Ferrera 2000; Guiso and Jappelli 2002). At the same time, in Italy (as well as in other countries where the rental market is limited because of public policies on housing), homeownership may be viewed not only as an investment of household savings, but also as an important form of insurance against social risks (Castles and Ferrera 1996; Conley and Gifford 2006).

Object of the Study and Research Questions

This study focuses on the relationship between economic insecurity and the reproductive plans of Italian women in couples who have recently had their first child.

The first issue that deserves attention is, therefore, the decision—which is in line with a large body of recent fertility research (e.g., Philipov 2009)—to focus on women’s reproductive plans. We are aware of the debate around the predictive value of fertility intentions, which are often found to be excessively optimistic. However, while their correspondence with observed fertility is not perfect, fertility intentions can be rightly regarded as an important component of the behavioral model which leads to fertility outcomes (ISTAT 2009b; Noack and Østby 2002; Schoen et al. 1999; Symeonidou 2000; Thomson 1997; Toulemon and Testa 2005; Westoff and Ryder 1977).

The core issue under investigation here is the relationship between economic insecurity and fertility intentions. The study focuses on the quantum and timing of the fertility intentions of Italian women who have a partner and have recently had their first child. Specifically, we first seek to understand the relationship between economic insecurity and the intention to have zero, one, or more additional children. We then shift our focus to those women who intend to follow the two-child family model, and look at how economic insecurity is associated with whether they intend to have a second (and last) child in the more proximate future (i.e., within the next 3 years) or later.

The question of what is economic insecurity and how it is measured is not straightforward and we devote the fifth paragraph to the issue. Here, we anticipate that, for the purpose of this article, economic insecurity is defined as a mix of the two partners’ employment status (which we refer to as employment-related insecurity) and of the monetary and nonmonetary resources available to the household for contrasting situations of economic adversities. In line with the literature reviewed and discussed in the introduction, our interest lies in understanding how women who recently had one child define their subsequent fertility intentions in the context of economic insecurity. This translates into the two following research questions.

The first research question may be expressed as follows:

Is the relationship between economic insecurity and fertility intentions characterized by risk aversion, or, conversely, by uncertainty reduction?

If risk aversion is the prevailing force, then women with insecure economic profiles should, in general, be less prone to plan to have more children, or should be more likely to postpone their intentions to the more distant future. From an empirical point of view, this would entail a negative relationship in our data between the variables measuring economic insecurity and (the quantum and timing of) fertility intentions. On the other hand, if uncertainty reduction is the prevailing force, the more “insecure” women would have higher and more immediate fertility intentions. Planning the birth of a child would be their direct response to reducing the biographical uncertainty entailed by economic insecurity. In this case, we would observe in our data a positive relationship between the variables measuring economic insecurity and (the quantum and timing of) fertility intentions.

According to the theoretical frame of reference presented in the introduction, however, the direction of the relationship between economic insecurity and fertility may not hold universally. We may reasonably assume that women with distinct characteristics on the one hand, and women who have different resources to mitigate possible unfavorable economic situations on the other hand, will define their fertility intentions differently when faced with occupational insecurity. Therefore, our second research question asked explicitly is as follows:

Does the relationship between employment-related insecurity and fertility intentions vary in relation to the sociodemographic characteristics of the woman? and Is the relationship between employment-related insecurity and fertility intentions moderated by the monetary and nonmonetary resources, on which a couple can rely in case of economic difficulties?

The first issue is empirically addressed in this article by considering the interaction of the variable describing the couple’s employment status with woman’s age and education, and by looking at the joint effect on fertility intentions.

With respect to the second issue, our attention focuses on the household context, considering the household’s saving capacity, the housing tenure, and the support provided by the extended family network after the birth of the first child. Again, the question is addressed in the empirical analysis by looking at the interaction between the employment-related insecurity and each of the three aspects above. In other words, we will be assessing how employment-related insecurity and fertility intentions are related for women who differ with respect to the resources available to their household to cope with potential economic difficulties.

With regard to the above-presented research questions, we expect (as suggested by the risk aversion hypothesis) to find that the negative relationship between economic uncertainty and reproductive plans is the prevailing force observed in our sample. Families living in situations of severe economic insecurity should experience, all other factors being equal, greater difficulties in planning to continue their reproductive careers.

In spite of being the prevailing force, the negative relationship may not, however, hold for all women. Thus, for instance, we expect to observe a differential effect by educational level. Other things being equal, women with higher educational level would be more inclined to renounce or to delay their fertility plans in situations of employment-related insecurity; less educated women, on the other hand, may place less value on the pursuit of economic security, and see an additional baby as a way out of insecurity. Age also may determine the way employment-related insecurity affects fertility intentions. Older women, being aware that they have less time left, might feel the pressure to plan a further birth, irrespective of their employment status.

In relation to the resources that a household can count on, we expect that individuals who rely on the safety net provided by the family might decide to face the risks connected with having more children, in spite of the eventual insecurity associated to their employment status. On the other hand, a reluctance to depend on their family of origin may further discourage the fertility intentions of some women. Similarly, we expect that homeownership as well as higher savings can favor the formation of positive fertility intentions.

The study looks separately at the quantum of fertility intentions and then, for women who plan to have only one more child, at their timing. The rationale is that the processes and considerations involved in a woman’s decision regarding how many children she intends to have, and regarding when she intends to have them, are different. We therefore expect to find that economic insecurity plays different roles in the quantum and in the timing of fertility intentions. Specifically, we hypothesize that the effects of economic insecurity on the intention to have a second child are stronger in the short term (i.e., within the following 3 years) than in the long term. It is likely that respondents implicitly take into account possible/probable changes over time when expressing their reproductive plans; choosing, for example, to postpone the birth of the second child in straitened circumstances. We also believe that economic insecurity can affect the intention to have one or more additional children differently. Because Italy is a low-fertility country, women with higher fertility intentions are particularly selected with respect to their individual characteristics, and their reproductive plans are less dependent upon economic conditions. Economic insecurity should therefore have a more negative effect on the intentions of one-child women interested in pursuing the two-child family model.

Data, Variables, and Methods

Data

The study relied on data from the Sample Survey on Births, which is periodically carried out by ISTAT. The survey represents one of the main sources for studying the reproductive behavior of mothers residing in Italy, and for assessing the relationship between the observed reproductive behavior and the socioeconomic context in which the births occur. Specifically, the present study used data from the second (and last available) survey edition, carried out during 2005 on a large and representative sample of women (n = 49,385) who had had a live birth 18 months before the interview. The survey questionnaire consisted of two modules: the short module, which was distributed to all women in the sample; and the extended module (containing thematic in-depth questions), which was distributed to only one-third of the sample (n = 15,870).

The analyses presented in this study are based on the responses of Italian women who completed the extended module. This form asked mothers about their fertility intentions.Footnote 1 It also collected a wide range of information about the sociodemographic characteristics of the mothers and their partners, such as their age, educational level, place of residence, and—of particular interest to us—working conditions. Questions were also asked about the household’s economic resources and housing tenure. Finally, details were gathered on the existence of networks of family support, including economic help from the extended family or assistance in the care of children. Thus, overall, the survey data have allowed us to examine the impact of economic insecurity, and to control for the main sociodemographic characteristics of the woman and her partner, as well as for the role of family-provided welfare.

Our final sample consists of 5,358 Italian women who had already had their first child, and who were still married to (or cohabiting with) the child’s father at the time of interview. Women whose first birth was a twin birth, who had children co-residing in the house other than the natural child they give birth to, who were pregnant at the time of the interview, or who had foreign citizenship were also excluded from the analysis.

Variables

In the extended module of the questionnaire, the women were asked the following question: “Do you intend to have other children in the future?” Respondents who say “yes”Footnote 2 were additionally asked: “How many children do you intend to have?” and “At what age—at the latest—do you intend to have your last child?”

We first focused on the quantum of fertility intentions of women with one child. Combining the information collected, we were able to classify women into three categories: (a) those who did not want another child, (b) those who intended to have one additional child only, and (c) those who planned to have two or even more additional children. We treated them as three separate categories for two reasons. Based on the theoretical considerations reviewed above, we wanted to explore whether there are differences in the sociodemographic profiles of women with one child who wanted no, one, or more additional children; and whether these women are exposed to different constraints. From a strictly pragmatic point of view, singling out the category of women intending to have one additional child only was convenient, since for these women we could also derive information on the timing of reproductive plans. The latter point will be clarified in the following paragraph. The resulting dependent variable, which measures the quantum of fertility intentions for women with one child (n = 5,358) is thus expressed as follows: intention of having another child in the future: no (n = 1,205); yes, one additional child only (n = 3,379); yes, two or more additional children (n = 774).

We then turned our attention to the timing of fertility intentions: i.e., to when the woman plans to have the child. In this respect, unfortunately, the survey’s questions were not ideal, since they asked about the intended timing for having the last (and not the next) child. However, the prevailing model of fertility intentions in Italy is that of two children, and only a relatively small (and highly selected) proportion of women intend to have more than two. Therefore, we restricted our attention to those women intending to have just one additional child, for whom the correspondence between the “next” and the “last” child was perfect, and the information on the intended timing was available. The resulting variable, which measures the timing of fertility intentions for women with one child intending to have only one additional child (n = 3,224), is the following: intentions of having the second child within the next 3 years: yes (n = 1,594); no, later (n = 1,630). We were thus able to draw comparisons between the factors affecting the formation of lifelong and short-term (i.e., the timing) intentions of having just one additional child.

The main issue addressed in this article is the relationship between women’s fertility intentions after having the first child and economic insecurity. We measured economic insecurity relying on several questionnaire variables. The derived variables account for both occupational-related characteristics which might increase the risk of experiencing economic difficulties, and the resources available to cope with potential economic loss. The conceptual and technical aspects behind their construction are illustrated in detail in the next paragraph. The models also include several sociodemographic control variables that usually play an important role in determining fertility plans: area of residence (North, Center, South), women’s age class at interview (<30, 30–34, 35 and older), and partnership status (married, or cohabiting). The two partners’ educational levels (mother’s educational level and father’s educational level with the following categories: low, medium, and high) are combined into a single variable to account for educational homogamy. The interaction, however, is observed with respect to woman’s education only to avoid empty cells, and the partner’s education is introduced as a control variable.

Table 4 in the Appendix reports the percentage distribution of explanatory variables for women with one child, by quantum of their fertility intentions. Table 5, instead focuses on women with one child intending to have one additional child only, presenting the percentage distribution of explanatory variables, by timing of their fertility intentions.

Methods

The quantum of the fertility intentions of women who have recently had one child was studied by means of a multinomial logistic regression. Women intending to have one additional child only and women intending to have two or more additional children were compared to women not intending to have additional children, which was taken as the base category. The choice of a multinomial logistic regression is the natural choice based on the theoretical considerations discussed previously. Our goal was to investigate whether there are differences in the sociodemographic profiles (and in the constraints) of women who already had one child, and who wanted no, one, or more than one additional child. Second, it permitted us to single out the category (women intending to have one additional child only) for which we could also derive the information on the timing of reproductive plans.

With respect to the timing of the reproductive plans of women with one child, a sample selection problem can arise, as the intention to have the second child within the next 3 years can be measured only for women with positive fertility intentions. If unobserved factors affecting the timing of fertility intentions are correlated with the factors affecting the formation of positive fertility intentions, standard regression techniques deliver inconsistent estimations. In order to overcome this possible bias, we opted for a modeling strategy which consisted of the joint estimation of two regression equations (Heckman 1979; see also Philipov et al. 2006 for an application to similar data).

The sample selection model for dichotomous variables can easily be written as a system of equations for two latent variables:

where y *i = 1 if the woman intends to have the second child within the next 3 years, and zero otherwise. In this context, y *i represents the latent continuous variable, β is the vector of parameters to be estimated, θ is the coefficient associated with the endogenous dummy, and u i is the residual term.

Similarly,

where I *i = 1 if the woman intends to have only one more child, and I *i = 0 if the respondent has negative fertility intentions. I * i represents a latent continuous variable, γ represents a vector of parameters, and v i represents the residual term. It should be noted that y i can only be observed if I i = 1.

In standard regression models, u i and v i are assumed to be independent. However, if we want to take into account potential sample selection, we have to consider the possible correlation between the two residual terms:

It is assumed that all the three parameters: ɛ i, τ i, and ζ i are independently normally distributed, with mean 0 and variance 1. Finally, λ is a free parameter. If λ = 0 the correlation (ρ) between the two residuals terms equals 0 as well. This means that the hypothesis of sample selection can be rejected. When the individuals are randomly selected from the sample, consistent and nonbiased estimations of β and γ are obtained by using ordinary probit or logit regression analysis. In this case only, the ordinary regressions and the sample selection model will lead to the same results.

Since the estimation of the sample selection model may require heavy computation, we adopted the strategy followed by Philipov et al. (2006). The first step was to estimate two separate probit models, ignoring the sample selection problem. The first model is on women’s intentions of having only one more child (the selection equation), while the second model tested the probability that women intending to have only one more child would plan the birth of the second (and last) child within 3 years (the structural equation). We then estimated the Heckman probit model with sample selection, including all of the covariates for the structural equation, but only those that proved significant for the selection equation.

The model returned a nonsignificant ρ-coefficient (see Table 6 in the Appendix). Thus, the correlation between the residual terms of the two equations was nonsignificant, meaning that—given the covariates we included—the sample selection did not have an effect on the equations’ coefficients. Therefore, in this case, the use of two separate equations with independent residual terms would not produce biased and nonconsistent estimations, and we therefore opted for a logistic specification of our model.

Measuring Economic Insecurity

A crucial point of this article is the measurement of economic insecurity. A large body of recent literature on the link between economic conditions and fertility and family formation has proposed conceptualizations of security (and/or insecurity) which encompass several dimensions of individuals’ living conditions (see Bernardi and Nazio 2005; Bhaumik and Nugent 2002; Kreyenfeld 2010; Tölke and Diewald 2003). Although their approaches differ, they all suggest that economic security should not merely be related to employment. As a matter of fact the measurement of economic security by means of the variables related to an individual’s occupational status only implicitly assumes that work equals economic well-being and leaves out other features (such as, for instance, the quality of work or the household’s financial resources) contributing to the individual’s personal security.

However, despite the large volume of empirical literature on economic insecurity, this issue is often examined only indirectly, and its measurement remains underdeveloped. Western et al. (2012) start with this observation, and then move on to define economic insecurity as “the risk of economic loss faced by workers and households as they encounter the unpredictable events of social life.” They then suggest a four-part framework for the study of economic insecurity. First, they argue that, given its relational nature, the study of economic insecurity should focus on households. This makes it possible to capture the complex dynamics of risk pooling within households consisting of more than one earner. Second, they assert that the concept of insecurity relates to (downward) changes in income over time, rather than merely to income levels. Third, they contend that income loss is linked to adverse events, such as unemployment, family dissolution, or poor health. Finally, they argue that the effects and prevalence of adverse events depend on the context of insurance relationships surrounding the households. They note that institutions such as the labor market, the welfare system, or the support provided by the family network are of particular relevance in this respect, as they provide resources and instruments for reducing, shifting, and spreading risks.

Drawing inspiration from this exhaustive framework, we focus on the household level, capturing both partners’ working conditions. In particular, valuing the adoption of a dynamic perspective, the woman’s contract duration and her partner’s position in employmentFootnote 3 are considered to account for the potential stability of employment-related income. Together, the features describing the two partners’ employment status should express the couple’s risk of experiencing economic difficulties. Then, the attention is shifted to the household’s ability to cope with unpredictable events, measured through its saving capacity and housing tenure, both seen as a form of insurance against future risks. Lastly, in the context of an increasingly de-regulated labor market and of a conservative welfare regime, we regard the extended family as an important safety net that promotes, supports, and readjusts the household’s well-being. Although not directly part of the couple’s monetary resources to cope with economic difficulties, the family network might indeed act as an important moderator of the effects of potential economic losses. To sum up, in this article we capture economic insecurity by considering both the insecurity potentially associated to the couple’s employment status and occupational characteristics and the other monetary and nonmonetary resources available to the household to cope in the event of economic adversities.

In the following we explain the operationalization of the considerations above for the purposes of this study; i.e., which survey questions were used and how.

In recognition of the relational nature of economic insecurity, we started by including the couple’s employment conditions. We built two variables (one for each partner) by combining information from several survey questions. The information is more detailed for women, since the questionnaire surveys occupational status, contractual typology, and sector. This allowed us to construct the variable woman’s employment conditions with the following six categories: employed-permanent contract, public sector; employed-permanent contract, private sector; employed-short-term contract; self-employed; unemployed; and not in the labor force. For men, owing to the lack of information on contractual typology (and because nearly all of the men in the sample were employed and the categories not in the labor force and unemployed are not numerically large enough to be considered separately), the derived variable man’s employment conditions distinguishes between in employment-high positions Footnote 4; in employment-medium–low position; and not in employment. The information from the two partners is combined into a single variable. After some preliminary analyses, however, some categories were merged together, to avoid small cell numbers. Particularly, the distinction between public and private sectors is omitted, as no significant differences were observed with respect to the definition of fertility intentions in our sample. The derived variable distinguishes eight categories under the three following headers: dual-earners (woman with long-term contract, man with a high occupational position; woman with long-term contract, man with a low–medium occupational position; woman with short-term contract, man with a high occupational position; woman with short-term contract, man with a low–medium occupational position); male bread-winner (woman not in employment, man with a high occupational position; woman not in employment, man with a low–medium occupational position); and other (man not in employment, woman either in or out of employment). In spite of the lack of proper longitudinal information, these variables partly incorporate the possible changes over time of employment-related economic security. Not only the contract duration in particular, but also the position in employment, contribute to the indirect evaluation of the expected steadiness of the partners’ position in the labor market.

As already mentioned, besides considering the insecurity associated to the couple’s employment status and occupational characteristics, we also measure the overall household’s ability to cope with future adverse events. In this respect, we consider three distinct aspects: the household’s saving capacity, the housing tenure, and the support received from the extended family network.

The first variable is constructed from the combination of the answers to the following survey questions: “Is the family’s monthly income sufficient to cover all expenses?”; and, for those who answered positively: “How much of your family income do you spend monthly?”. The variable we derived is thus the proportion of monthly income spent, with the categories less than half; half; more than half; all; and non-sufficient income. The variable also has a residual category (sufficient income, but percentage spent undeclared), which consists of respondents who declared their income to be sufficient, but who did not state the proportion spent. Some of the categories were merged together for the estimation of the final models presented in this article. In general, the variable provides an indirect measure of the household’s saving capacity, thus contributing to the measurement of the extent of economic insecurity.

Housing tenure is also seen as a further form of insurance against risks, and it distinguishes between homeownership; renting; and other. The last category includes both a few nonresponses and the responses of families who live in a house without being owners or tenants; most of those who fall into this group are living in a house provided by their parents (or by other members of the extended family).

Finally, we considered an additional variable that measures the support received by the couple from members of the extended family. The variable results from combining information collected through several questionnaire items. The first set of items relates to whether the couple has received any economic help in the year following the birth of the first child; and, if they have, whether this assistance came from family members or other persons. The second set of items refers to whether the woman has relied on somebody else for child care and/or household chores. Again, it was possible to distinguish between whether this help came from close family members or from other persons or institutions. We focused on the (both economic and child care) help received from the extended family only, and we combined the information into the variable family-based welfare, with the following four categories: no help; informal care only (help in child care and household chores); economic help only; and both (economic and informal) forms of help. The last two categories, both involving economic help, were aggregated into one because their relationship with the dependent variables was in the same direction. In combining these categories, we avoided including in the models categories of variables with numbers that were too small.

Results

In the following paragraph, we describe the results of our empirical analyses, in line with the theoretical assumptions and the consequent research questions outlined earlier in this article. We start by briefly reporting the reproductive plans expressed by our sample. We then look at the relationship between economic insecurity and the quantum of fertility intentions. Results from the corresponding multinomial logistic regression are presented in Table 2, together with comments. Next, we focus on the relationship between economic insecurity and the timing of reproductive plans of women who intend to have one additional child only. The related logistic model is reported in Table 3 and is illustrated. We then examine whether the relationship between employment-related insecurity and (the quantum and timing of) fertility intentions varies depending on the woman’s sociodemographic characteristics. Finally, we assess the mediating role of the resources available to reduce the impact of economic loss on the relationship between employment-related insecurity and fertility intentions. The interaction effects are presented in the Appendix (Tables 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12). All models, whether with main effects only or with interaction effects, control for the remaining sociodemographic variables.

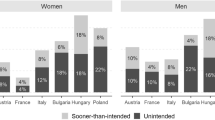

Among Italian women in couples who have recently had their first child, the orientation toward the two-child family model still prevails: 63.1 % of respondents plan to have one additional child only. In contrast, fewer than one out of four women show negative fertility intentions, and just 14.4 % of them expect to have two or more additional children by the end of their reproductive career. However, among women intending to have exactly one additional child, only half plan to have the baby within the next 3 years (Table 1).

Table 2 presents the results from the estimation of the multinomial logistic model on the quantum of fertility intentions. Column 1 reports the relative risk for the intention to have one additional child only, while Column 2 contains model estimations for the intention to have two or more additional children. In both cases, the base category consists of women of parity one with negative fertility intentions. In general, the results indicate that women who intend to have one more child only and women who intend to have two or more children differ, insofar as the reproductive plans of women with higher fertility intentions are less dependent upon economic conditions. On the other hand, the observed effects of the sociodemographic variables are very similar, although generally more pronounced in magnitude on the intention to have two or more additional children.

Age is undoubtedly a driving factor, especially among those with higher (two or more additional children) fertility intentions. Women who are aged 35 or older, in particular, are significantly less likely to plan the birth of an additional child compared with the reference category (women aged 30–34). Women below age 30 do not differ from the reference category in the intention to have only one more child, but they are more than twice as likely to plan to have two or more additional children. This age effect is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Berrington 2004), which have found that the percentage of women who intend to have no further children increases rapidly with age. It can be argued that older women are aware they have less biological time left for planning further births; at the same time, however, higher long-term fertility intentions may act a priori toward an earlier start of the reproductive career.

Our main interest lies in detecting how economic insecurity is related to women’s reproductive intentions. Surprisingly, the insecurity associated to the couple’s current employment status does not significantly differentiate the quantum of woman’s reproductive plan. Compared to women with long-term contracts whose partners hold high occupational positions, no significant variations in relative risks are observed across the categories obtained by the combination of the two partners’ job characteristics. The only exceptions are couples where the man is not in employment (which are less likely to plan one additional child only) and couples where the woman is not in employment and the man holds high occupational positions (which are conversely more likely to plan two or more children). Results are however only weakly significant. If employment-related insecurity only moderately affects the quantum of reproductive intentions, on the other hand considerations over the overall household’s ability to cope with future economic risks appear to play a key role, particularly for one-child women interested in pursuing the two-child family model. The relative risk of intending to have exactly one more child decreases with increasing proportions of monthly income spent and it is lower for women who are renting. Moreover, when the household has no saving capacity, also the risk of higher fertility intentions is significantly lower. The informal network of the family exerts a positive influence on the formation of long-term fertility intentions, particularly when it does not involve monetary transfers. Women who report relying on direct help provided by their close family networks following the birth of their first child are more likely to report they want to extend their reproductive career.

The other sociodemographic control variables follow the expected direction. We found that women living in Southern Italy are more likely to plan to have second and subsequent children. Married women seem to adhere to the two-child family model more often than those who cohabit, while no significant difference by living arrangement is observed with respect to the planning of larger families. The results also indicate that the higher the educational level of both partners, the higher is the chance a couple plans to have additional children.

The second aim of this article was to delve more deeply into the reproductive plans of women with one child who follow the two-child model by looking at the timing of their fertility intentions. More specifically, we wanted to assess whether economic insecurity affects short-term and long-term reproductive intentions differently.

The reproductive plans of women in the sample differ significantly with respect to the temporal span of reference. We found (Table 1) that nearly one out of two women who expect to have exactly two children intend to have the second (and last) child within 3 years (49.4 %), while the other half plan to have their second child later.

Table 3 presents the results from the estimation of the logistic model on the timing of fertility intentions. More precisely, it shows the estimates in relation to the intention to have the second child within 3 years of the interview versus later.

As a first general remark, it should be noted that, of the sociodemographic variables considered, only age and couple’s education play a significant role in shaping the timing of fertility intentions. Furthermore, their effect has an opposite direction on short-term compared to long-term fertility intentions. Among women who intend to have exactly two children, in fact, the older ones are more likely to plan to have the second within the next 3 years, while younger women are more likely to postpone it. Then, the couple’s educational level also affects short-term fertility intentions in an opposite direction compare to what observed for lifetime fertility plan: the higher the educational level, the lower is the odds-ratio of intending to have the second child within 3 years.

Even more interestingly, the variables capturing the household’s risk of experiencing economic loss and its ability to cope with it are differently associated to short-term compared to long-term fertility plans. Specifically, the insecurity associated to the couple’s current employment condition plays now a major role on the intention of having the second child in the next 3 years. Women who are either not in employment or with a short-term contract, and whose partners hold low–medium occupational positions, are significantly less likely to plan their second child in the short term. Having a partner in a low–medium occupational position also moderately discourages the fertility intentions of women with more secure contracts. Only weakly significant differences are observed in the definition of short term intentions by tenure or by proportion of income spent, with lower odds ratio for women renting or with no saving capacity. Also, the help provided by family members (which had an impact on the definition of the quantum of fertility intentions) has no significant association with the intended timing of the birth of the second child, either in the form of economic help and assistance with child care, or in the form of the direct provision of child care only.

As posited by the second research question, however, the effect of employment-related insecurity on reproductive plans may not be univocal, but may instead vary in relation to the sociodemographic characteristics of women or depending on the availability of other resources to contrast situations of economic hardship.

Thus, we first interact employment-related security with the woman’s sociodemographic characteristics (tables available on request) but contrary to our expectations, its effect does not appear to vary significantly by women’s characteristics. Specifically, we do not observe any significant differences in the effect of employment-related insecurity at different ages or educational levels with respect to the quantum of fertility intention nor to the timing of an additional birth.

Then we argue that the resources available to the household to cope with situations of economic difficulties—besides having an impact per se—could moderate the effects of employment-related insecurity. We therefore interact the three variables reflecting the extent and typology of resources with the variable capturing the insecurity associated to the employment status, and include them (one interaction at a time) in the model, again controlling for the remaining sociodemographic variables. The interactions are often only weakly significant and should anyway be interpreted with caution, as—in spite of the merging together of some categories—the results might still be affected by small cell numbers. Tables 7, 8 and 9 in the Appendix report the relative risks for the interaction terms included in the multinomial logistic regression on the quantum of fertility intentions. The results suggest that the effect of employment-related insecurity on the definition of long-term fertility intentions is to some extent moderated by the resources available to the households. For instance, women are significantly less likely to express the intention of having two or more children if they spend more than half of their monthly income, and the differences are particularly remarkable for women either with short-term contracts or not in employment, whose partner hold low–medium occupational positions. With the only exception of the couples where the man is not in employment, no significant differences by the couple’s employment conditions are observed with respect to the intention of having another child among the homeowners. Living in a rented house, however, has a detrimental effect on fertility intentions—particularly of having two or more children—on all the typologies of couple other than the reference category (i.e., woman with a long-term contract, man with a high occupational position). Lastly, the positive effect of having received help with child care, when observed across the categories of employment-related security, persists only for women in couples with greater occupational security. Particularly, having received economic help significantly reduces the relative risk of expressing the intention of having two or more children for women not in employment with partners in high occupational positions.

Table 10, 11, and 12 in the Appendix shows the odds ratios for the interaction terms as included in the logistic model on the timing of fertility intentions of women who plan to have another child only. Although sometimes the values of the odds ratios might hint at a more or less pronounced effect of occupational insecurity depending on the availability of other resources, the results are mostly not significant to draw any firm conclusion. Overall, results suggest that couples are more concerned with the insecurity potentially associated to their current employment status than with the availability of other resources to face possible future uncertainties, when expressing their contingent fertility intention for the more proximate future.

The effects of the other control variables do not vary from those already reported in Tables 2 and in 3 respectively, and are therefore not included.

Discussion

This article contributes to the study of the reproductive plans of Italian women who recently had their first child by examining the association between these plans and economic insecurity. Reproductive choices, as well as other sociodemographic behaviors, may be affected by the increasing economic insecurity that Italy (along with most Western economies) is experiencing as a consequence of the profound transformation brought about by globalization processes and the deregulation of the labor market. The study distinguishes between the quantum and the timing of fertility intentions. First, we studied the intentions of women with one child of having no more children, one additional child only, or two or more additional children over their entire reproductive life span. Then, we focused on women who follow the two-child family model and looked at whether they were intending to give birth to the second (and last) child in the more proximate (i.e., within the next 3 years) or the more distant future.

Two main alternative hypotheses have been proposed in the literature to explain the relationship between economic insecurity and fertility behaviors: the risk aversion and the uncertainty reduction hypotheses. At the same time, several authors argue that it might not be a matter of either-or, but rather the strength and direction of the relationship might vary depending on individual and contextual features. Thus, from an empirical point of view, the study tried to determine whether one of the two mechanisms was predominant in our sample. At the same time, we considered the possibility that both of the relationships could be relevant, acting differently based on each woman’s sociodemographic characteristics (above all, age and education) and household context.

This article’s originality lies in the conceptualization of economic insecurity and the investigation of its effects on both the quantum and timing of fertility intentions. Inspired by the framework developed by Western et al. (2012), we proposed to capture economic insecurity by focusing on the household and by considering both the insecurity associated to the position of the two partners in the labor market and a variety of aspects that contribute to the household’s ability to cope with possible unpredictable future events. Empirically, we considered four main dimensions: the couple’s employment status and occupational characteristics, the household’s saving capacity, the housing tenure, and the support received from the extended family network. Each dimension was measured by combining several survey variables.

There are several strengths in the way we capture economic insecurity in this study that are worth noting. First, we assume that economic insecurity is relational, and hence we look at the two partners’ employment status. Furthermore, the variable captures other characteristics that describe the quality of work, such as occupational position and contract duration. The relevance of these characteristics increases in light of the recent diffusion of precarious working careers, characterized by the experience of downward mobility, fixed-term contracts, part-time work, and employment below the level of training acquired. In addition, they indirectly account for the stability of the employment-related income. Workers with permanent contracts are less exposed to the risk of unemployment or of a worsening of their economic conditions, and workers with higher occupational positions are endowed with skills that would enable them to find another position quickly. The opposite is the case for workers in atypical or nonskilled jobs.

Second, and in addition to the variable accounting for the insecurity potentially associated with the couple’s employment status, the household’s monetary and nonmonetary resources (here expressed in terms of saving capacity, homeownership and support from the family network) are seen as playing a role in defining the overall sense of economic security. Particularly in situations of economic recession, these factors offer protection from future risks and unanticipated events.

We are aware that other aspects could contribute to the definition of economic insecurity. When possible, a more complete assessment of individuals’ and families’ feelings of insecurity would provide useful insights into the complex interactions between current and perceived insecurity and individual decision-making (Kohler and Kohler 2002; Kreyenfeld 2010; Perelli-Harris 2006). Recently, the effects of trust on fertility behavior have also been highlighted (Aassve et al. 2011). While subjective measures of insecurity were not collected by the survey we used, these issues suggest directions for future research. Furthermore, the measurement of economic insecurity could be enriched by the availability of longitudinal information, which would allow for the dynamic assessment of worsening/improvement of the household’s economic resources.

As a firs general remark, our data clearly confirm the existence of a critical factor in the passage from the generic fertility intentions to the contingent plan to have a child in the next 3 years: only half of women with one child, who intend to have one more child feel ready to plan to have a second in the next 3 years.

The study also reinforces an argument that is frequently made: i.e., that fertility intentions over the entire lifetime are less conditioned upon contingent constraints, and are often more closely related to individual traits and/or preferences. Fertility intentions in the near future, on the other hand, are often said to derive from a more realistic evaluation of the contingent situation. In the specific case of Italian women with one child and their intentions regarding whether and when to have a second child, individual sociodemographic traits play a significant role in shaping lifelong intentions, whereas only age and education matter for short-term intentions. Furthermore, the effect of both age and education has an opposite direction on short-term and long-term fertility intentions. Younger women have usually higher fertility intentions, but they feel less the pressure of planning a child in the immediate future. Similarly, women from highly educated couple have more often higher fertility intentions, but when it comes to making plans for the immediate future they tend to postpone, perhaps being more concerned with the effects of long breaks on their career opportunities. Finally, and even more interestingly in the light of our research aims, the degree of security associated with the resources available to cope with unpredictable events, exerts a strong and positive influence on the definition of the quantum of long-term fertility intentions; short-term plans are, on the other hand, almost solely related to the couple’s current employment status.

With specific regard to the variables selected to describe economic insecurity for the purpose of this study, their choice allowed us to gain precious insights on the different strategies of Italian households, and how these relate to their fertility intentions. Not surprisingly for a country where the female labor force participation is low, the security (and earnings) associated to the man’s occupational position still plays a greater role in shaping the household’s fertility decisions. Couples where the man holds low–medium occupational positions are systematically less likely to express the intention of having another child in the short term. However, and perhaps reflecting the consequences of the changes in Western economies, and, specifically, of the deregularization of the labor market not supported by adequate social protection, Italian households seem to seek the security necessary for family building in a double-earner strategy that can shield them in case of temporary job loss or a contract break. The negative effects on short-term fertility intentions are particularly pronounced when the lower status of the man’s occupation is not counterbalanced by a safe and sound position of the woman within the labor market.

Beside the security derived from a solid and gainful participation in the labor market of both partners, our study highlighted the importance of relying on other monetary and nonmonetary resources. These are particularly helpful in the definition of a long-term fertility plans. In this respect, and within a context of a familistic Welfare regime such as in Italy, the role of the extended family appears unquestionable, both earlier in life to favor the transition to adulthood (with inter vivos transfers to help with the purchase of a house) and later as a provider of free childcare and as source of economic help in case of economic difficulties.

Finally, a last remark on the support offered by the close family network which seems to act as a double-edged sword: although it moderates the effects of economic insecurity, its effect is not the same for all women. Among other things, the role played by family-provided help may depend upon the perceptions and the feelings of the couples receiving it. On the one hand, couples may feel protected and supported by a cooperative family network, and thus encouraged in their reproductive plans. Conversely, they may suffer the pressure of being dependent upon their families. This may explain why some women who had relied on economic help from their families were not inclined to have further children. Furthermore, as family support is an uneven instrument that not everybody enjoys in the same way, it cannot be regarded as a valid alternative to public measures to counteract the pressures of economic insecurity on young couples’ fertility intentions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study draws attention to the existence of a nonnegligible association between economic insecurity and reproductive plans. The results showed that, in the Italian context, the risk aversion hypothesis prevails, particularly in shaping short-term fertility intentions. This finding is noteworthy in itself, and even more so if we consider that fertility intentions which explicitly refer to a short-term temporal frame are more likely to result in actual reproductive behavior (Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan 2003).

For two reasons, we believe that the impact of economic insecurity on realized fertility could indeed be even stronger. First, it is widely known that negative fertility intentions are often realized: consequently, the more the economic insecurity discourages the planning of further births, the stronger will be its effect in depressing the actual fertility levels. Second, the reported results showed that economic insecurity has a greater influence on the forming of positive fertility intentions in the short than in the long term. The possible risk then is that , the continuous postponement of the plan to have a second child may eventually turn into forgone fertility. Given this risk, it would be extremely interesting to perform the same analysis using more recent data, which will be released in the next future. This would allow us to explore the issue in light of the most recent economic recession, as we expect levels of insecurity to have grown further. The challenges that the downturn presents would have become more evident, and thus even more strongly associated with current and prospective family plans. Furthermore, the survey data to be released will include a longitudinal component, which will allow us to overcome the analytic limitations associated with the use of cross-sectional data.

Finally, the study has underlined the critical passage from generic fertility intentions to the contingent plan to have a child in the next 3 years and the inadequacy of family-provided support to ease the pressures of economic insecurity. These findings call for greater attention at the institutional level. Effective public measures aimed at the reduction of families’ economic insecurity (especially if combined with an increase in affordable conciliation measures) may actually play a relevant role in encouraging the planning (and, thus, also the realization) of new births. This appears to be even more important in light of the inadequacy of the familistic welfare regime, in which public support to the families is limited and the families themselves often act as shock absorbers. We may envisage distinct policy measures, complementing one another, which could help to reduce the feeling of economic insecurity faced by families, enabling them to look to the future with more confidence. These might include, for example, policies favoring access to homeownership or controlled rent, or policies for income support directed particularly at atypical workers who are likely to face periods of involuntary absence from the labor market. Policies to enhance the public supply of child care services—which represent a major expense for families—would serve a similar purpose. Studies on short-term fertility intentions could thus acquire further relevance, as they may allow for a timely adjustment of national social measures.

Notes

The survey, being directed at women only, does not collect information on partners’ fertility intentions. We are aware, however, of their relevance and of the complexity of the decision-making process within the couple (for a thorough review of studies dealing with the issue, e.g., Thomson et al. (1990); for a recent analysis on couples in Italy, see Cavalli and Rosina (2011). At the same time, several studies have shown a strong association between women’s and their partners’ fertility intentions, suggesting that the intentions women express at the time of interview have been influenced by previous daily interactions, the sharing of experiences, and negotiations between the partners, and they are thus already inclusive of men’s intentions (Berrington 2004; Fried et al. 1980; Miller and Pasta 1995; Morgan 1985; Thomson 1997; Thomson et al. 1990; Thomson and Hoem 1998; Udry 1983).

The survey only distinguishes between positive and negative fertility intentions. Both respondents who answered “don’t know” and respondents who refuse to answer were coded as “no answer.” Therefore, our analysis could not take into account the degree of certainty attached to fertility intentions, and the category of women with uncertain fertility intentions could not be included in the models.