Abstract

Despite a growing interest in the family trajectories of unmarried women, there has been limited research on union transitions among cohabiting parents. Using data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth, we examined how family complexity (including relationship and fertility histories), as well as characteristics of the union and birth, were associated with transitions to marriage or to separation among 1,105 women who had a birth in a cohabiting relationship. Cohabiting parents had complex relationship and fertility histories, which were tied to union transitions. Having a previous nonmarital birth was associated with a lower relative risk of marriage and a greater risk of separation. In contrast, a prior marriage or marital birth was linked to union stability (getting married or remaining cohabiting). Characteristics of the union and birth were also important. Important racial/ethnic differences emerged in the analyses. Black parents had the most complex family histories and the lowest relative risk of transitioning to marriage. Stable cohabitations were more common among Hispanic mothers, and measures of family complexity were particularly important to their relative risk of marriage. White mothers who began cohabiting after conception were the most likely to marry, suggesting that “shot-gun cohabitations” serve as a stepping-stone to marriage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Cohabitation plays an increasingly prominent role in family formation in the United States. Not only are men and women more likely than ever to cohabit and to cohabit with their spouse prior to marriage, an increasing proportion of births are occurring in cohabiting unions (Kennedy and Bumpass 2008). According to recent estimates, almost one in five (19 %) of all births (and 52 % of births outside of marriage) occur to cohabiting couples (Manlove et al. 2010).

Children born to cohabiting parents are better off financially than children born to parents not in a coresidential union, but they also tend to show poorer cognitive, socio-emotional and health outcomes than children born to married parents (Brown 2010; McLanahan 2011). Some of the disadvantages faced by children born to cohabiting couples are attributable to differences in economic resources and parenting styles between married and cohabiting couples (Brown 2010). However, the fact that cohabiting unions with children are more likely to dissolve than are marital unions—leading to family and economic turbulence in the lives of children—plays a role as well (Manning et al. 2004; McLanahan 2011).

Children born to cohabiting parents who eventually marry, however, have a lower risk of seeing their parents’ union dissolve than do those whose parents who don’t marry. In fact, Manning et al. (2004), find that the risk of union dissolution for white children born to cohabiting parents who eventually marry is indistinguishable from that for children born to married parents, although this is less the case for black and Hispanic children. As such, some see the birth of a child to a cohabiting couple as a critical point for marriage promotion interventions (Lichter et al. 2006). However, very few cohabiting couples with children marry despite high levels of expressed interest in marriage at the birth of their child (Carlson et al. 2004; Waller and McLanahan 2005). For couples, a more comprehensive understanding of factors associated with the transition to marriage—as well as to dissolution—among cohabiting parents can help inform programs and services targeted to improve union stability. For children, this same understanding provides important information on their family context while growing up and can help inform efforts to promote child wellbeing.

In this paper, we use a large, nationally representative data set—the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG)—to examine the transition to marriage or separation among a sample of women aged 15–44 who were cohabiting at their child’s birth. We concentrate our focus on three specific aims. First, we seek to understand how family complexity—including a history of prior births, marriages, or cohabiting unions–is linked to the transition out of a cohabiting union. Second, we seek to understand how the characteristics of the current cohabiting union and birth shape a couple’s transitions after the birth. Third, we seek to understand how patterns of marriage and dissolution differ for white, black and Hispanic cohabiting mothers.

It is important to note that we focus only on cohabiting couples with a birth. While a burgeoning body of research has examined the transitions to marriage or dissolution among cohabiting couples more generally (Smock et al. 2008), less research has focused specifically on transitions among cohabiting parents. Couples who give birth in a cohabiting union, however, differ from couples who choose to cohabit but don’t have children (until marriage) in important ways (Brown 2010), ways that likely alter the decision-making process around marriage and dissolution. Notably, the circumstances of the birth itself become an important influence. Similarly, although a number of studies over the past decade have examined the stability of unions among cohabiting parents, many of these do so only in comparison to the stability of unions among married parents (Manning et al. 2004; Osborne et al. 2007) or non-coresident couples (Carlson et al. 2004; Hohmann-Marriott and Amato 2008). While these studies help identify factors linked to the difference in union dissolution between parents in different types of unions, they assume these factors operate in the same manner across union types, although research suggests that, in at least some cases, they differ (Osborne 2005).

Background

As the proportion of children born outside of marriage has grown (to 41 % in 2009), the stability of families for children born into cohabiting or non-coresidential union has become a predominant area of research in the family over the past decade (Smock and Greenland 2010). Building on dominant theories on family formation more generally, research examining this issue has emphasized the importance that economic resources and security, relationship quality, and norms and attitudes play in both the transition to marriage as well as dissolution (Carlson et al. 2004; Osborne 2005). Recent research grounded in the lifecourse perspective also suggests that increased family complexity (e.g., prior marriages, cohabitations, and births) as well as characteristics of the cohabiting union and birth might pose additional complications to the desire or ability to marry even among couples living together (Edin and Kefalas 2005; England and Edin 2007; Goldscheider and Sassler 2006; Manning et al. 2004), and this is where we focus our concentration. Although we are not the first study to examine the role of family complexity or relationship and birth characteristics in union transitions among cohabiting couples with children (Mcclain 2011; Osborne 2005), the use of the NSFG allows us to include measures not available in other frequently used data sets (i.e., Fragile Families, a sample of urban mothers) for a nationally-representative sample of women in the United States, variables such as a history of cohabitation (in addition to marriage), the marital status of prior births, and birth intentions of the mother and father.

The role that family complexity and relationship/birth characteristics play in the stability of families for children born to cohabiting parents, however, is likely to vary across racial and ethnic groups. There are large, and historically deep, racial and ethnic differences in family formation processes in the U.S. In 2009, 72 % of births to black women and 53 % of births among Hispanic women occurred outside of marriage compared with 36 % of all births among white women (Martin et al. 2011). Additionally, over 60 % of the nonmarital births to white and Hispanic women occur within cohabiting unions, although only 29 % of births to black women do (Manlove et al. 2010). These patterns are closely tied to the declines and delays in marriage over the past several decades in the United States, particularly among black and low-income women (Smock and Greenland 2010). There is also evidence to suggest that the meaning and role of cohabitation and marriage may differ across racial and ethnic groups, reflecting varying access to social and economic resources as well as exposure to varying cultural and social contexts (Landale and Oropesa 2007; Osborne et al. 2007; Smock and Greenland 2010). These differences lead us to expect racial and ethnic differences in the likelihood of marriage or union dissolution in response to a cohabiting birth, but also suggest that factors associated with union transitions among cohabiting parents may differ across groups. Therefore, we conduct analyses for the sample as a whole as well as separately for white, black, and Hispanic parents. Of the two studies we identified that examined transitions out of cohabitation within a sample of cohabiting parents (both using Fragile Families data) (Mcclain 2011; Osborne 2005), neither examined race-ethnic differences.

Family Complexity

The changes in family formation over the past 50 years or so, including delays in marriage as well as increases in nonmarital childbearing and cohabitation, mean that at the birth of a child, women, and men often already have complex family histories (Goldscheider and Sassler 2006; Smock and Greenland 2010). They may have a history of prior marital and cohabiting unions that have dissolved and previous children with other partners (multiple partner fertility). These histories are almost certain to play a role in the decision-making surrounding marriage and union dissolution among cohabiting parent, in part because these histories are likely markers for other well-known characteristics, such as fewer economic resources and increased strain, that are linked to marriage or union dissolution more generally (Bramlett and Mosher 2002). However, they may also be markers of other behavioral and attitudinal characteristics that influence marriage and dissolution, net of economic factors.

Prior Relationships

Although no research has focused specifically on cohabiting couples who gave birth, research among all cohabiting couples (whether they had children or not) finds that women who were previously married or who cohabited with a different partner are less likely to transition to marriage than those who were never in another co-residential union (Lichter et al. 2006; Steele et al. 2005); this is particularly true for poor cohabiting women (Lichter et al. 2006). Previously married cohabitors—again with or without children—are also less likely to end their cohabitations in separation than cohabitors who were never married (Steele et al. 2005). These findings suggest that individuals with complex relationship histories may be reticent to marry, but not necessarily to remaining in a cohabiting union.

Other research suggests why this might be the case. One study found that women with a high risk of marriage dissolution also have a high risk of ending a cohabiting union (whether it has children or not), net of a wide range of controls (Steele et al. 2005). The authors suggest that there are likely some underlying, unmeasured attributes that may make some women more prone to unstable partnerships in general. While some of these attributes may reflect access to economic resources, some may reflect relationship dynamics. Qualitative research on unmarried parents suggests that relationship problems—such as violence, infidelity, and mistrust—may be as strong as or an even stronger determinant of union dissolution, and perhaps the decision to stay in a union but not marry, than economic factors (Reed 2007). A history of prior unions, in particular, may serve as a marker of some of these attributes and be indicative of relationship dynamics that serve as a barrier to marriage, and may even promote dissolution, particularly when children are involved. An alternative hypothesis is that a history of previous marriages (vs. cohabitations) may reflect more positive attitudes towards marriage or a higher preference for marriage, and thus the association between positive marriage attitudes and the likelihood of marriage (Waller and McLanahan 2005) may lead cohabitors with a prior marriage history (although not those with a prior cohabiting history) to marry (and to not dissolve their union).

Fertility

Among all cohabitors, a history of prior births with another partner reduces the odds of ever marrying (Bramlett and Mosher 2002; Steele et al. 2005). Similarly, the presence of children from a partner’s previous relationship is linked with a lower likelihood of marriage or cohabitation among all unmarried parents 1 year after the birth of a child (Carlson et al. 2004; Reichman et al. 2004; Waller and McLanahan 2005). Among urban cohabiting parents, however, results are mixed. Although one study finds that either the mother or father having a prior birth increases the risk of dissolution (although not marriage) compared to staying in a cohabiting union (Mcclain 2011), another finds no association with either marriage or dissolution (Osborne 2005).

Despite the mixed findings, there are several reasons to expect the presence of prior children will reduce the likelihood of marriage and increase the likelihood of dissolution among cohabiting parents. First, men and women with multiple partner fertility tend to have fewer economic resources than those without children from previous partners, and, to the extent that they must provide support to other children, what economic resources exist are spread out across more people and across more households (Smock and Greenland 2010). These two factors—limited economic opportunities in combination with financial obligations to previous children—are cited as barriers to marriage promotion among unmarried fathers (Gibson-Davis et al. 2005; Ooms and Wilson 2004). Additionally, the presence of stepchildren can add stress and conflict into a household as families try to negotiate complex relationships. In fact, prior research finds that, at least among fathers, involvement with prior children is a primary source of mistrust among cohabiting parents (Reed 2006). To the extent this is true, previous marital births may reduce marriage and increase dissolution more so than previous nonmarital births, because of the greater nonresident father involvement present for children born in prior marriages (Amato et al. 2009; Argys et al. 2007).

Characteristics of the Cohabiting Union and Birth

The second aim of our research seeks to understand how circumstances of a child’s birth and of the union in which it occurs may shape parents’ union transitions. In particular, we focus on the length of the cohabiting union before the birth, the age difference between cohabiting parents, whether the birth was identified as intended by the mother and the father, and whether the couple had any other children together. These characteristics will provide a descriptive portrait of cohabiting couples at the time of the birth, as well as key information about how these circumstances are associated with both the transition to marriage and to dissolution.

In general, the longer a woman has been in a cohabiting union (regardless of whether she had children in that relationship), the less likely she is to get married and the less likely she is to separate (Lichter et al. 2006). As such, we expect to see increased duration prior to pregnancy associated with a reduced risk of marriage and of dissolution compared to remaining in a cohabiting union. However, the relative timing of cohabitation in relation to a pregnancy also matters. Women who enter into cohabitation after becoming pregnant are more likely to get married after 1 year of cohabitation than are those who began cohabiting prior to a pregnancy (Bramlett and Mosher 2002). For these women, cohabitation is likely seen as temporary and serves as a stepping-stone to marriage. This highlights that for many couples, decisions about cohabitation, marriage, and childbearing tend to occur jointly (Musick 2007; Wu and Musick 2008).

Although mother’s age was not linked to union transitions among one sample of cohabiting mothers (Osborne 2005), older ages among women and their partners have been linked to reduced union dissolution among cohabiting couples more generally (Lichter et al. 2006). This is perhaps not surprising as increased age is linked to increased maturity and resources, factors that generally contribute to more stable relationships. The age difference between the partners may provide even more information about the context of unions, as women (particularly teenage women) in relationships with a much older partner are more likely to be in coercive relationships with unequal power dynamics (Darroch et al. 1999). Very little research in the U.S. has examined the role of age differences in union transitions (and none among cohabiting parents), although studies from Canada and the Netherlands found that cohabitations and marriages have a higher probability of dissolution if the woman is older than the man (Kalmijn et al. 2007; Wu and Hart 2003). Research in the U.S., however, shows no significant association between age difference and relationship dissolution among married and cohabiting couples (Shoen 2003), indicating that further research is needed.

Unintended births, especially unwanted births, have long been associated with negative health and developmental outcomes for families, women, and children (Gipson et al. 2008; Logan et al. 2007; Santelli et al. 2003). Although most research focuses on the consequences of unintended childbearing for children (Logan et al. 2007), some limited research finds that unintended pregnancy is linked to lower mental health among women and higher relationship stress among couples (Gipson et al. 2008; Scott et al. 2010). These factors, in turn, are important mediators in the association between a couple’s pregnancy intentions and later union status among unmarried parents, including those in cohabiting and non-coresident relationships (Scott et al. 2010). We expect that cohabiting parents in which either partner (or both) did not intend the pregnancy will have a higher risk of union dissolution compared to staying in a cohabiting union or getting married. However, we also expect that an intended pregnancy will be associated with greater chances of a transition to marriage compared to staying in a cohabiting union, because it may demonstrate a couple’s commitment to their current union and be indicative of positive marriage intentions.

Although, as described above, we expect prior fertility with other partners to disrupt cohabiting relationships, we expect repeat joint childbearing to be linked to union stability either by transitioning to marriage or remaining cohabiting. Previous studies have found that having shared prior children together is associated with an increased likelihood that unmarried parents (including cohabitating and non-coresident parents) remain in a coresidential relationship 1 year after the birth of a child (Carlson et al. 2004) and with an increased likelihood of marriage (or remaining married) among all parents—including those who were married, cohabiting, or in a non-coresidential union at the birth of the child (Reichman et al. 2004).

Racial/ethnic Differences

Differences in the role of cohabitation across groups—being more a stepping stone to marriage among white women, while serving as a more acceptable venue in which to have children among Hispanic and perhaps black women (Landale and Oropesa 2007; Musick 2007; Wildsmith and Raley 2006)—lead us to expect that white cohabiting mothers will be more likely to marry than black or Hispanic mothers and that cohabiting Hispanic mothers will be the least likely to dissolve their cohabiting unions. Previous empirical work supports some of these expectations. For example, Carlson et al. (2004) used Fragile Families data and found that white and Hispanic women are more likely to marry or cohabit 1 year after a nonmarital birth than are black women. However, Osborne (2005) also using Fragile Families data, finds that mothers outside of coresidential unions, in fact, drive much of this effect; she finds no significant racial or ethnic differences in the odds that women cohabiting at the birth of their child transition to marriage or separation within 1 year. Whether factors associated with union transitions after a cohabiting birth vary by race/ethnicity is not examined.

Differences in the role of cohabitation across groups, however, coupled with differences in attitudes and expectations regarding marriage and childbearing also lead us to expect that the role that family complexity and the circumstances of the union and birth union play in union transitions among cohabiting parents will vary across racial and ethnic groups. For example, research finds that births outside of marriage among Hispanic women are much more likely to be planned than are comparable births to white and black women (Musick 2007). To the extent cohabitation is seen as an acceptable venue in which to have children, having an intended birth may not be linked to marriage among Hispanic women as much as it is for other women, and may be more strongly linked to remaining in a cohabiting union. As another example, some qualitative research suggests that black women have particularly high standards regarding what relationship characteristics need to be in place in order to marry (Edin and Kefalas 2005). If this is the case, family complexity may be an even stronger barrier to marriage among cohabiting black mothers than it is for white or Hispanic mothers. Thus, in our third aim we examine these associations between family complexity as well as the characteristic of the union and birth with union transitions separately for white, black, and Hispanic cohabiting parents.

Data and Sample

We used data from the 2002 NSFG, a cross-sectional nationally representative survey of men and women aged 15–44. Conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, the NSFG contains over-samples of Hispanics, African-Americans, and teenagers. Female respondents provide retrospective information about their birth and relationship histories and other factors relating to reproductive health and fertility. Unfortunately, comparable information on men is not available, so we limited our analyses of union transitions following a cohabiting birth to women.

The baseline NSFG sample includes 7,643 women aged 15–44. To create our analytic sample of women who had a birth in a cohabiting union, we removed 3,739 women who never cohabited, 1,056 women who never had a birth, and 1,665 women who did not have any births within cohabiting relationships. An additional 78 women are removed from the analytic sample (6.5 % of women eligible to be in the sample) because they have missing data on dates regarding their current or prior relationships. These restrictions resulted in an analytic sample of 1,105 women who ever had a birth within a cohabiting relationship and who had complete information on cohabitation dates.

In order to examine women’s relationship transitions over time and include both time-invariant and time-varying measures, we constructed a person-month file consisting of a separate observation for each month in which a cohabiting mother was at risk of a relationship transition. A risk spell began when a respondent had a birth within a cohabiting relationship and ended when the respondent exited that cohabiting relationship by either ending the relationship or marrying her cohabiting partner. If the respondent had another birth within the same cohabitation, she remained in the same risk spell. Respondents were censored if they experienced no change in relationship status by the 2002 interview date. Because respondents could have births with more than one partner from different cohabiting relationships, they could contribute multiple risk spells to our analysis file. Ninety-eight women had two risk spells (a birth with two separate cohabiting partners), while one woman had three risk spells, reflecting almost 9 % of women in the sample. Therefore, our final sample includes a total of 1,205 risk spells (and 45,668 person-months) contributed by the 1,105 women in the sample.

In order to assess whether the predictors of cohabiting relationship transitions differ by race/ethnicity, we conducted analyses using subsamples of 378 white, 328 black, and 362 Hispanic women who had a cohabiting birth. There were too few women (37) of “other” race to include in subgroup analyses. White, black, and Hispanic women contributed 406, 363, and 397 risk spells, and 11,887, 14,676, and 17,993 person-months to our analyses, respectively.

Measures

Dependent Variable

Our dependent variable is a three-category time-varying measure indicating whether the respondent experienced a relationship transition in each month. In each month following the cohabiting birth, the respondent could transition to marriage with that partner, end the cohabiting relationship, or experience no transition (remain in the cohabiting union).

Independent Variables

We included several time-invariant and time-varying independent variables in our analyses to test whether family complexity and characteristics of the union and focal birth were associated with union transitions following a cohabiting birth, net of a range of background and control variables.

Family Complexity

Characteristics of fertility and relationship histories of respondents and their partners were measured using time-invariant measures whose values are constant throughout the risk spell. Two dichotomous variables indicating whether the respondent had any marital or nonmarital births with a different partner prior to the focal birth (the first birth within a cohabiting relationship) were created. Because partners were not surveyed in the NSFG, we used respondent reports to created one dichotomous measure indicating whether their partner had any children from his prior relationships (these data did not allow us to distinguish between births that occurred inside or outside of marriage).Footnote 1 Two dichotomous variables indicated whether the respondent had ever been married or had ever cohabited prior to her current relationship. One measure, based on respondent reports, indicated whether her partner had ever been previously married (women did not report on partner’s previous cohabitating relationships).

Characteristics of the Union and Birth

We examined a number of characteristics of the cohabiting union and the focal birth in our analyses. These included time-invariant measures of the age difference between partners (a three-level variable indicating whether the partner was the same age or younger, 3–5 years older, or more than 5 years older than the respondent), birth intentions (comparing whether the cohabiting birth was intended by both partners, unintended by both, intended by the mother but not her partner, intended by the partner but not the mother, or whether the mother did not know either her own or her partner’s intentions), and the duration of the cohabitation prior to the birth (less than 9 months, 9–24 months, or longer). Note that we rely on mothers’ reports of their partners’ birth intentions. Time-varying measures included a dichotomous variable that indicated whether the respondent had more than one birth with their cohabiting partner by that time in the spell.

Background Characteristics and Controls

We controlled for individual and family characteristics that have been shown to be associated with union formation and dissolution. Time-invariant measures included race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, or another race), nativity (foreign-born or not), respondent’s age at first birth, respondents’ age at the focal birth (indicating whether the respondent was a teen, aged 20–24, or aged 25+ at the birth), parent’s education (whether the respondent’s most highly educated parent did not receive a high school degree, received only a high school degree, or completed at least some college), and family structure (assessed by whether the respondent lived with two biological/adoptive parents at age 14 and whether her parents were married when she was born). We additionally included a time-invariant measure that controlled for the decade of birth (1980s, 1990s, or 2000s) and two time-varying variables indicating whether the respondent had graduated from high school and the number of months that had passed since the focal birth.

Methods

In this paper we used a combination of descriptive and multivariate analyses to address our research aims. We first present sample characteristics for all of the independent variables included in the multivariate analyses, for the sample as a whole and separately for white, black, and Hispanic women. To examine our dependent variable, we next show results from life-table analyses that examined the cumulative probability of union transitions over time—to marriage, dissolution, or no change—for the sample as a whole, as well as separately for white, black, and Hispanic women. Finally, we show results from event-history analyses modeling the union transitions from a cohabiting union. Specifically, we used discrete-time multinomial logistic regression analyses of person-month data to model the the transition to marriage versus no relationship change as well as the transition to ending the cohabiting union versus no relationship change. We conducted analyses on the full sample, as well as separate regression models for white, black, and Hispanic subsamples. We ran t-tests to compare the relative risk ratios for each racial/ethnic group against each other to assess whether the observed associations differed significantly across models. All analyses were weighted and run in Stata using SVY commands to control for the complex sampling design of the NSFG.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 shows the weighted distributions of all variables for the respondent-level samples.Footnote 2 Almost half of our full sample of respondents was white (46 %), and about a quarter each was black (23 %) and Hispanic (27 %). Approximately 16 % of the mothers in our sample were born outside of the U.S., including half of Hispanic mothers.

Family Complexity

The cohabiting mothers in our sample had a fair amount of family complexity. Approximately one-quarter (26 %) of the women in our sample had at least one prior nonmarital birth; fewer reported any prior marital births (11 %), any prior marriages (17 %), or prior cohabiting relationships (19 %). Twenty percent of the sample reported that their partners had been previously married and one-third of the sample reported that their partners had at least one child from a prior relationship.

Compared with blacks and Hispanics, whites were more likely to have had a previous marital birth, to have ever been married, and to have had a prior cohabiting relationship. Compared with white and Hispanic women, black women were more likely to have had a prior nonmarital birth. White women were more likely than black or Hispanic women to report that their partner had been previously married, while black women’s partners were more likely than white or Hispanic women’s partners to have had a birth with another partner.

Characteristics of the Union and Birth

One-quarter of our sample had a birth with a partner who was five or more years older. One-third of the births in our sample were intended by both partners (33 %), one-third were unintended by both partners (35 %), and almost one-quarter of births occurred to parents who did not agree on intentions. Most of the cohabiting unions began prior to conception (prior to 9 months before the birth); however, almost 30 % of the women began cohabiting with their partner after conception. Finally, more than one-quarter (28 %) of the women reported more than one birth with the same cohabiting partner.

Compared with whites, Hispanics were less likely to have a partner at least 5 years older and more likely to report that the birth was intended by both partners, whereas blacks were less likely to report that the focal birth was unintended by the father only and more likely to report that it was unintended by the mother only. Additionally, more Hispanic women (38 %) had multiple births within a cohabiting union than did white (23 %) or black (26 %) women.

Background Characteristics and Controls

One-third of the respondents in our sample were teenagers (35 %), and 39 % were young adults aged 20–24 at the time of the focal birth. The average age at first birth was 20 years of age. Most women had graduated from high school, had parents with at least a high school degree, were born to married parents, and lived with two biological parents at age 14. The majority of births in our sample occurred during the 1990s (53 %), compared with 29 % that occurred in the 1980s and 18 % in the 2000s. Respondents spent approximately 36 months in each risk spell, on average.

Black and Hispanic women had somewhat different profiles than white women. Hispanic women had the highest proportion of teen births and the lowest levels of education, among themselves and among their parents. Hispanic respondents also had the longest risk spells. Black women were the least likely to live with two biological parents at age 14. Additionally only 57 % of black women and 72 % of Hispanic women were born to married parents compared to 91 % of white women. White women were older on average at first birth than were black or Hispanic women.

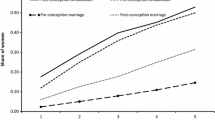

Life-table Estimates

Table 2 presents life-table estimates of transitions out of cohabitation—either to marriage or separation—among all mothers in our sample and separately for white, black, and Hispanic cohabiting mothers. In general, for the first year, unions were fairly stable. Almost three-quarters (74 %) of all cohabiting mothers were still in a cohabiting union 1 year after the birth, while another 15 % had married the father of their child. However, unions became somewhat less stable over time. Five years after the child’s birth, one-third of cohabiting couples had ended their relationship, although more than 40 % of the cohabiting couples had married and another 25 % remained in their cohabiting union.

There were some notable race/ethnic differences in transitions. One year after the birth, white mothers were more likely than black or Hispanic mothers to transition out of a cohabiting union, mostly because of their greater likelihood of marrying the father (20 % of white mothers versus 10 % of black and 11 % of Hispanic mothers). By 5 years after the birth, almost half of white cohabiting mothers had married the father of their child, compared with only one-third of both black and Hispanic cohabiting mothers. In contrast, black cohabiting mothers were more likely to end their cohabiting union than white or Hispanic mothers. Hispanic mothers were most likely to remain in a stable cohabiting union 5 years after the birth (41 % vs. 19 % of white and 22 % of black mothers).

Multivariate Results—Transition to Marriage

Tables 3 and 4 show relative risk ratios from multinomial logistic regression analyses predicting a transition to marriage compared with no relationship transition (Table 3) and separation versus no relationship transition (Table 4). The two tables are based on the same set of multinomial models, for the full sample and for racial/ethnic sub-groups. Some predictors (marked by dashes) were not included in all of the subgroup analyses because of small cell sizes. We discuss cases where some of the primary independent variables were significantly associated with marriage or union dissolution for one race/ethnic group, but not for another. However, this does not necessarily mean that these associations vary across groups, as other factors (including small sample size) might account for a non-significant association for a specific race/ethnic group. Thus, we also highlight when measures of family complexity and characteristics of the union and birth that differed in their associations with marriage and union dissolution across race/ethnic groups based on t-test comparisons.

Family Complexity

The only measure of family complexity associated with the transition to marriage in the full model was the mother’s history of prior marital births. Women in the full sample (and white women) who had any prior marital births had more than twice the relative risk of transitioning to marriage compared with those who did not (rrr = 2.26 for the full sample and 3.04 for whites). In addition, Hispanic women with a previous nonmarital birth had less than half the relative risk of marriage versus staying in a union (rrr = 0.43), although this association did not differ significantly from whites or blacks. Partner characteristics were only associated with the transition to marriage for Hispanics. Specifically, Hispanic women whose partners’ had children from prior relationships—particularly previous nonmarital births (analyses not shown)—had a lower relative risk of marriage (rrr = 0.28), whereas Hispanic women whose partners had been previously married had more than twice the relative risk of marriage versus staying in a union (rrr = 2.53). These associations among Hispanics women were significantly stronger than the (non-significant) associations among white women (and black women in the case of relationship histories).

Characteristics of the Union and Birth

The age difference between partners was not associated with the transition to marriage among the full sample of cohabiting mothers. However, white mothers with a partner who was five or more years older had half the relative risk of marriage versus staying in a union (although this association was not significantly different from that of blacks or Hispanics). Among the full sample, respondents who reported that their partner intended the birth but they did not had a lower relative risk of marrying (rrr = 0.60), as were respondents who did not know the intentions of one or both partners (rrr = 0.53). Intentions were associated with marriage for white and black women in particular, as there were no significant associations among Hispanic women. White respondents reporting that both partners did not want the birth, and black respondents who reported that the woman only did not intended the birth (but the partner did), had a reduced relative risk of marriage (both of these associations differed from the non-significant association for Hispanic women). In addition, white women who reported one or both partners did not know their intentions had a reduced relative risk of marriage than those who both intended the birth, although this association did not differ significantly from other race/ethnicity groups.

Cohabiting for less than 9 months before the birth—i.e., beginning to cohabit after conception—was associated with higher odds of transitioning to marriage for the full sample (rrr = 1.65), and this appears to be largely driven by white women (rrr = 2.55). Cohabiting unions of longer duration were not associated with marriage in the full sample, although having a particularly stable pre-birth cohabitation (one that that lasted longer than 2 years) was associated with a lower relative risk (rrr = 0.57) of marriage for Hispanics, and this differs from the non-significant association for whites. Finally, although having multiple births within a cohabiting union was not linked to marriage for the full sample, it was linked to an increased relative risk of marriage for whites (rrr = 1.65), and this differed from the non-significant association for Hispanics.

Background Characteristics and Controls

Most of the background and control variables were linked to the transition to marriage in the expected ways. Black mothers and foreign-born mothers in the full sample (driven by Hispanics) had a lower relative risk of transitioning to marriage compared to remaining in a cohabiting union. High school graduation was linked to a greater risk of marriage, in the full sample and for white women. Having a birth within cohabitation as a teen was also associated with a reduced relative risk of marriage, though for black women only. Among Hispanic mothers, those who grew up with both biological parents had a greater relative risk of marriage. Among white mothers, having married parents was linked to a greater risk of marriage, while having a birth in the 2000s was linked to a reduced risk of marriage. For the full sample, a longer duration of time since the birth was associated with a lower relative risk, with every additional month of time since the baby was born associated with a 1 % reduction in the relative risk of marriage.

Multivariate Results: Dissolution Versus No Union Change

Family Complexity

As shown in Table 4, women’s prior fertility was not associated with union dissolution, but their partner’s prior fertility was. Women whose partner had a prior birth with another partner had an almost 50 % higher relative risk (rrr = 1.49) of ending the union compared to remaining in a cohabiting union; this association was particularly strong among the partners of white women (relative to black women). Conversely, it was women’s prior relationships, and not men’s, that were associated with union dissolution. Women who had ever been married had a substantially lower relative risk (rrr = 0.42) of seeing their union end than were women without a prior marriage, and this association was significant for white and black women (with the association especially strong for black versus Hispanic women). Additionally, among Hispanic women, having a history of prior cohabiting unions was associated with more than twice the risk of union dissolution (rrr = 2.16), and this association was stronger for Hispanics than for blacks or whites.

Characteristics of the Union and Birth

In the full sample, women who had a birth with a partner who was more than 5 years older than themselves had a lower relative risk of ending the cohabiting relationship (rrr = 0.59). The association between partner age difference and union dissolution differs across racial/ethnic groups. Among white women, having a partner between 3 and 5 years older (but not more than 5 years older) was associated with an increased risk of union dissolution; however, among black and Hispanic women, having an older partner was linked to reduced dissolution. In the full sample, respondents who reported that the birth was unintended by one or both partners had a greater relative risk of ending the relationship. There were racial/ethnic differences in the significance of associations between fertility intentions and union dissolution (although coefficients did not differ significantly across groups). Among Hispanics, relationships in which neither partner intended the pregnancy had a greater risk of dissolution, and among blacks, relationships in which the mother did not intend the birth or did not know either her own or her partner’s birth intentions were associated with a greater risk of separating. Neither the duration of the cohabiting union or having subsequent births within the union was linked to the risk of union dissolution versus staying in a cohabiting union.

Background Characteristics and Controls

For individual and family characteristics, Hispanic race/ethnicity and growing up with two biological parents (for blacks and Hispanics) was associated with a lower relative risk of separation. In contrast, being born outside of the United States (for whites), graduating from high school (for the full sample and for whites), having a parent who attended college (for the full sample), and having parents who were married at the respondent’s birth (for the full sample) were associated with a greater relative risk of separation. The relative risk of ending the relationship was lower cohabiting couples who had a birth in the 1980s and higher for those who had a birth in the 2000s, relative to cohabiting women who had a birth in the 1990s.

Discussion

In this paper, we used data from the 2002 NSFG to examine union transitions among women who have a birth in a cohabiting union, focusing specifically on the role that family complexity and characteristics of the union and birth play in the transition to marriage and to dissolution. We additionally examined whether these associations differed significantly across the major race and ethnic groups in the U.S.

We found that for the first year after the birth cohabiting unions were fairly stable; only 11 % of cohabiting couples dissolved their union, while 15 % transitioned to marriage. However, by 5 years after the birth, one-third of cohabiting couples had ended their relationship and more than 40 % of the cohabiting couples had married. Relationship dissolution was especially prevalent among black cohabiting mothers, while Hispanic cohabiting mothers were about twice as likely to remain in a stable cohabiting union as whites or blacks and less likely to dissolve a union.

We should note that although our full sample estimates of marriage after 1 year are very similar to estimates by Osborne (2005) and Carlson et al. (2004) using Fragile Families data, our estimates of dissolution after 1 year (11 %) are lower than estimates in these two studies (roughly 25 %). Some of the difference may have to do with differences in survey design; the sample in Fragile Families is a prospective study of urban parents, while the NSFG, although nationally-representative, gathers data retrospectively. The retrospective nature of reports may cause women to under report cohabiting unions, particularly if they dissolve soon after the birth. However, our estimates of dissolution are also somewhat lower than estimates in Manning et al. (2004) who, using the 1995 NSFG, found that 15 % of cohabiting unions with a birth had dissolved after 1 year. It is worth noting, however, that the sample in Manning et al. (2004) was restricted to cohabiting mothers who had never been married and were under 30.

Family Complexity

Many of the cohabiting mothers in our sample had complex family histories, or partners with complex family histories, at the time of the birth. Our findings highlight the importance of these histories in later union transitions. Cohabiting mothers with a previous marriage had a reduced relative risk of separating, and, among Hispanics, cohabiting mothers whose partner has a previous marriage had an increased relative risk of marriage. These findings may reflect, in part, more positive attitudes about marriage and/or greater “marriageability” among men and women with a previous marriage, which may increase their likelihood of union stability or transitioning to marriage. Conversely, previous cohabitations are associated with an increased relative risk of separating among Hispanic mothers. This suggests that a history of unstable less formal unions may serve as a marker for unmeasured characteristics—be they economic or behavioral—that make unions harder to maintain (Lichter et al. 2006; Manning et al. 2004; Upchurch et al. 2001).

Although prior childbearing generally serves as a deterrent to marriage among cohabiting couples (Bramlett and Mosher 2002; Manning 2004; Steele et al. 2005), this is not always the case among cohabiting mothers. In our sample, having a previous marital birth was associated with an increased relative risk of marrying. This may, again, reflect a more positive orientation to marriage more generally. However, for Hispanic mothers, having a previous nonmarital birth outside of the current cohabiting union was associated with a reduced relative risk of marriage. Similarly, having a partner with a previous birth was also associated with an increased relative risk of separating among the full sample and for whites. This is consistent with some prior research using Fragile Families data and suggests that multiple-partner fertility is often associated with relationship instability, perhaps because of the economic and time constraints it introduces into the current relationship (Carlson et al. 2004; McClain 2011; Reichman et al. 2004).

Characteristics of the Cohabiting Union and Birth

Characteristics of the union and the birth were also linked to union transitions. For example, having an older partner was associated with a reduced relative risk of marriage among white mothers, but was also associated with a reduced risk of separating among the full sample and among black and Hispanic mothers. Prior research has found that married couples are more homogamous across a range of factors, including age, than are cohabiting couples (Schoen and Weinick 1993; Smock 2000). There may be barriers in resources or ideology that make non-homogamous cohabiting couples less likely to marry. At the same time, the increased maturity of older partners may contribute to the reduced likelihood of dissolving a cohabiting union (Lichter et al. 2006).

Both mother and (respondent reported) partner fertility intentions were associated with union transitions. Only one-third of the sample of cohabiting mothers reported that both parents intended the child at conception, reflecting the unplanned nature of pregnancies to cohabiting couples (Finer and Henshaw 2006). Couples in which neither partner intended pregnancy (one-third of the sample) had a lower relative risk of marriage for whites and a higher risk of separating for the full sample and for Hispanics, consistent with expectations that unintended births are linked to instability. Additionally, couples in which only one parent did not intend pregnancy had a greater risk of separating and in some cases, a lower relative risk of marriage, possibly reflecting conflict and stress within relationships that may limit union stability (Gipson et al. 2008; Scott et al. 2010).

For the almost one-third of mothers in our sample who began cohabiting after pregnancy but before the birth, cohabitation may be seen as one stage in the transition to marriage. “Shot-gun cohabitations” (Kefalas, M., Furstenberg, F. F., & Napolitano, L. (Unpublished Work). Marriage is more than being together: The meaning of marriage among young adults in the United States. The Network on Transition to Adulthood. Working Paper, September 2005), or cohabitations that occur in response to a pregnancy, were linked to an increased risk of marriage and likely reflect the joint decision-making process in family formation—where decisions about childbearing, cohabitation, and marriage occur simultaneously—seen among some groups of women (Wu and Musick 2008). However, the longer the pre-birth cohabitation, the lower the relative risk of transitioning to marriage for Hispanic mothers, suggesting that long-term cohabitations may be a more permanent state for this group. Notably, almost one-third of Hispanic cohabiting mothers in our sample remained in stable unions 5 years after their child’s birth.

Finally, 28 % of our sample had another birth within the current cohabiting relationship, and this is associated with an increased relative risk of marriage for whites in particular, supporting research showing that subsequent children may solidify a relationship and provide impetus to marriage (Bramlett and Mosher 2002).

Racial and Ethnic Variation

The race and ethnic variations seen in the link between family complexity and characteristics of the union and birth with transitions among cohabiting mothers are consistent with prior research suggesting that cohabitation may serve as a stepping stone to marriage for white women, but be seen more as an alternative to marriage among Hispanic women, and perhaps to a lesser extent, black women (Edin et al. 2004; Landale and Fennelly 1992; Landale and Oropesa 2007; Wildsmith and Raley 2006). Specifically, the association between a post-conception cohabitation and a greater relative risk of transitioning to marriage was significant only for whites, as was the association of subsequent births within a cohabiting union and a greater risk of marriage, indicating that cohabitation may be seen as a transition stage to marriage for whites but not for blacks or Hispanics. In contrast, the high percentage of long-term cohabiting couples with multiple shared births among Hispanics suggest that these unions may serve as more as a substitute for marriage, rather than a preliminary stage to marriage.

Additionally, for Hispanics, family complexity appears to be particularly critical in decisions about marriage. This may reflect a cultural orientation among Hispanics, particularly the foreign-born, that places a strong emphasis on how family-related factors uniquely shape life transitions (Vega 1990). Alternatively, it could be that, for this group in particular, cohabitation and marriage are markers for other unmeasured socio-economic or behavioral characteristics that shape marriage and childbearing. It is worth noting, however, that the role of cohabitation is constantly evolving; while cultural and structural factors no doubt play a role in family transitions, the interplay of these explanations for family change is exceedingly complex, and incompletely understood (Landale and Oropesa 2007).

Limitations

This study has several limitations to note. First, this study relies on retrospective cohabitation, birth, and marital histories. Women are less likely to accurately identify the starting and ending dates of cohabiting relationships than of marriages. In an attempt to minimize this concern, during interviews, the NSFG provides a life history calendar to encourage more accurate recall of events such as contraceptive use, conception, and changes in living arrangements (Groves et al. 2005). Second, because of the retrospective nature of the data, we do not have employment and income information about couples, which we know is linked to union formation (Lichter et al. 2006; Osborne 2005). Third, we do not control for the potential endogeneity of previous fertility and relationship decisions and current relationship trajectories for cohabiting parents. Thus, our findings are descriptive and we do not make causal assumptions. Finally, we rely on mother reports of father fertility intentions, and some research suggests that mothers often under-estimate the extent to which fathers did not intend the current pregnancy (Guzman et al. 2008). However, our analyses suggest that father intentions, even when reported by the mother, are important for union transitions.

Conclusion

Prior research, drawing from theories surrounding union transitions among men and women more generally, has highlighted the importance that socioeconomic characteristics, relationship quality, and attitudes play in the transition to marriage or dissolution among cohabiting parents (Carlson et al. 2004; Osborne 2005; Manning et al. 2004). We find that identifying both the family complexity of men and women as well as the characteristics of the union and birth adds to our general understanding of what shapes union transitions among cohabiting couples with children. This is perhaps not surprising since the child, and the dynamics around the child and how resources are distributed, becomes an important factor in the decision-making process surrounding union formation or dissolution.

These findings have implications for programs that seek to improve child well-being by increasing family stability (through stable cohabiting unions or transition to marriage with a cohabiting partner). For example, these programs must recognize the unique difficulties for men who have children from previous relationships. Indeed, limited economic opportunities in combination with financial obligations to previous children are cited as barriers to marriage promotion among unmarried fathers (Gibson-Davis et al. 2005; Ooms and Wilson 2004).

Notes

A small percentage of respondents in our sample (less than 5%) were missing on this and the other two partner measures, as well as on measures of birth intentions and some family background measures (nativity, parent’s education, and parent’s marital status at the respondent’s birth). In the multivariate analyses, we substituted missing data on these measures with the sample mode or mean.

The respondent-level sample characteristics are almost identical to characteristics at the risk-spell level because there are 1105 respondents and only 1205 risk spells.

References

Amato, P. R., Meyers, C., & Emery, R. E. (2009). Changes in nonresident father–child contact from 1976 to 2002. Family Relations, 58(1), 41–53.

Argys, L., Peters, H. E., Cook, S., Garasky, S., Nepomnyaschy, L., & Sorensen, E. (2007). Measuring contact between children and nonresident fathers. In S. L. Hofferth & L. M. Casper (Eds.), Handbook of measurement issues in family research (pp. 375–398). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Bramlett, M. D., & Mosher, W. D. (2002). Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Vital Health Statistics, 23(22), 1–93.

Brown, S. L. (2010). Marriage and child well-being: Research and policy perspectives. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 1059–1077.

Carlson, M., McLanahan, S., & England, P. (2004). Union formation in fragile families. Demography, 41(2), 237–261.

Darroch, J. E., Landry, D. J., & Oslak, S. (1999). Age differences between sexual partners in the United States. Family Planning Perspectives, 31(4), 160–167.

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2005). Promises i can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Edin, K., Kefalas, M., & Reed, J. (2004). A peek inside the black box: What marriage means for poor unmarried parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(4), 1007–1014.

England, P., & Edin, K. (2007). Unmarried couples with children: Hoping for love and the white picket fence. In P. England & K. Edin (Eds.), Unmarried couples with children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Finer, L. B., & Henshaw, S. K. (2006). Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38(2), 90–96.

Gibson-Davis, C. M., Edin, K., & McLanahan, S. (2005). High hopes but even higher expectations: The retreat from marriage among low-income couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(5), 1301–1312.

Gipson, J., Koenig, M., & Hindin, M. (2008). The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: A review of the literature. Studies in Family Planning, 39(1), 18–38.

Goldscheider, F. K., & Sassler, S. (2006). Creating stepfamilies: Integrating children into the study of union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 275–291.

Groves, R. M., Benson, G., & Mosher, W. D. (2005). Plan and operation of cycle 6 of the National Survey of Family Growth. Washington: National Center for Health Statistics.

Guzman, L., Manlove, J., Franzetta, K., & Schelar, E. (2008). Father’s childbearing intentions: Comparing mother-proxy and father self-reports. Paper presented at the 2008 Population Association of America Annual Meeting, New Orleans.

Hohmann-Marriott, B., & Amato, P. (2008). Relationship quality in interethnic marriages and cohabitations. Social Forces, 87(2), 825–855.

Kalmijn, M., Loeve, A., & Manting, D. (2007). Income dynamics in couples and the dissolution of marriage and cohabitation. Demography, 44(1), 159–179.

Kennedy, S., & Bumpass, L. (2008). Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research, 19(47), 1663–1692.

Landale, N., & Fennelly, K. (1992). Informal unions among mainland Puerto Ricans: Cohabitation or an alternative to legal marriage? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54(2), 269–280.

Landale, N. S., & Oropesa, R. S. (2007). Hispanic families: Stability and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 381–405.

Lichter, D. T., Qian, Z., & Mellott, L. M. (2006). Marriage or dissolution?: Union transitions among poor cohabiting women. Demography, 43(2), 223–240.

Logan, C., Holcombe, E., Manlove, J., & Ryan, S. (2007). The consequences of unintended childbearing: a white paper. Washington: Child Trends and The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy.

Manlove, J., Ryan, S., Wildsmith, E., & Franzetta, K. (2010). The relationship context of nonmarital childbearing in the U.S. Demographic Research, 23(22), 615–654.

Manning, W. D. (2004). Children and the stability of cohabiting couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(3), 674–689.

Manning, W. D., Smock, P. J., & Majudmar, D. (2004). The relative stability of cohabiting and marital unions for children. Population Research and Policy Review, 23(2), 135–159.

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Ventura, S. J., Osterman, M. J. K., Kirmeyer, S., Mathews, T. J., et al. (2011). Births: Final data for 2009. National Vital Statistics Reports 60(1). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Mcclain, L. R. (2011). Better parents, more stable partners: Union transitions among cohabiting parents. Journal of Marriage & Family, 73(5), 889–901.

McLanahan, S. (2011). Family instability and complexity after a nonmarital birth: Outcomes for children in fragile families. In M. J. Carlson & P. England (Eds.), Social class and changing families in an unequal America. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Musick, K. (2007). Cohabitation, nonmarital childbearing, and the marriage process. Demographic Research, 16(9), 249–286.

Ooms, T., & Wilson, P. (2004). The challenges of offering relationship and marriage education to low-income populations. Family Relations, 53, 440–447.

Osborne, C. (2005). Marriage following the birth of a child among cohabiting and visiting parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(1), 14–26.

Osborne, C., Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. (2007). Married and cohabiting parents’ relationship stability: A focus on race and ethnicity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(5), 1345–1366.

Reed, J. (2006). Not crossing the “extra line”: How cohabitors with children view their unions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(5), 1117–1131.

Reed, J. (2007). Anatomy of the break-up: how and why do unmarried couples with children break-up? In P. England & K. Edin (Eds.), Unmarried couples with children. New York City: Russell Sage Foundation.

Reichman, N., Corman, H., & Noonan, K. (2004). Effects of child health on parents’ relationship status. Demography, 41(3), 569–584.

Santelli, J. S., Rochat, R., Hatfield-Timajchy, K., Gilbert, B., Curtis, K., Cabral, R., et al. (2003). The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35(2), 94–101.

Schoen, R., & Weinick, R. M. (1993). Partner choice in marriages and cohabitations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 55, 408–414.

Scott, M. E., Steward, N. R., & Schelar, E. (2010). Couple-level pregnancy intentions and subsequent relationship formation and dissolution. Paper presented at the 2010 Population Association of American Annual Meeting, Dallas, Texas.

Shoen, R. (2003). Union disruption in the United States. Demography, 32(4), 36–50.

Smock, P. (2000). Cohabitation in the United States: An appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 1–20.

Smock, P. J., Casper, L. M., & Wyse, J. (2008). Nonmarital cohabitation: Current knowledge and future directions for research: Population Studies Center Research Report 08-648.

Smock, P. J., & Greenland, F. R. (2010). Diversity in pathways to parenthood: Patterns, implications, and emerging research directions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 576–593.

Steele, F., Kallis, C., Goldstein, H., & Joshi, H. (2005). The relationship between childbearing and transitions from marriage and cohabitation in Britain. Demography, 42(4), 647–673.

Upchurch, D. M., Lillard, L. A., & Panis, C. W. A. (2001). The impact of nonmarital childbearing on subsequent marital formation and dissolution. In L. L. Wu & B. Wolfe (Eds.), Out of wedlock: Causes and consequences of nonmarital fertility (pp. 344–380). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Vega, W. A. (1990). Hispanic families in the 1980s: A decade of research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52(4), 1015–1024.

Waller, M., & McLanahan, S. (2005). “His” and “Her” marriage expectations: Determinants and consequences. Journal of Marriage & Family, 67, 53–67.

Wildsmith, E., & Raley, R. K. (2006). Race-ethnic differences in nonmarital fertility: A focus on Mexican American women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 491–508.

Wu, Z., & Hart, R. (2003). Union disruption in Canada. International Journal of Sociology, 32(4), 51–75.

Wu, L. L., & Musick, K. (2008). Stability of marital and cohabiting unions following a first birth. Population Research and Policy Review, 27(6), 713–727.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge research support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through grant R01 HD044761-04 and the Department of Health and Human Services, through grant 1 PO1 HD04561-01A1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Manlove, J., Wildsmith, E., Ikramullah, E. et al. Union Transitions Following the Birth of a Child to Cohabiting Parents. Popul Res Policy Rev 31, 361–386 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-012-9231-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-012-9231-z