Abstract

This paper examines the impact of maternity leave legislation on first birth timing in Great Britain. When maternity leave was introduced in Great Britain in 1976, the eligibility requirement for full-time employees was to have been working for the same employer for at least 2 years. Using data from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), this paper examines whether women postponed first birth in accordance with tenure requirements for maternity leave. Higher transition rates to first birth are found for those who had acquired enough employer tenure to qualify for maternity leave than for those who did not yet qualify. However, the causal role of maternity leave legislation for first birth timing is uncertain, since transition rates to first birth began to diverge by employer tenure even before 1976.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Family policies occasionally have impacts on processes of family formation, whether intended or unintended. When statutory maternity leave and pay were introduced in Great Britain in 1976, the eligibility requirement for full-time employees was to have been working for the same employer for at least 2 years. This paper examines whether this special eligibility requirement caused a postponement of first births. While maternity leave and pay were available earlier on a contractual basis to a subgroup of employees, this paper examines whether the extension to all employees and particularly the strict eligibility requirements impacted first birth timing. If eligibility regulations for maternity rights influence decisions about when to have a first child, this would indicate a high level of importance of these rights to employed women. From the perspective of theories of individual-level decision making, an effect on fertility timing would give evidence that people take macro-level policy changes into consideration when making life-course decisions. The regulations for maternity rights may also have been one factor contributing to the rise in age at first birth in Great Britain.

The first section of this paper gives an account of the development of maternity rights regulations in Great Britain. This will be followed by a review of previous studies on the relationship between maternity leave policy, employment, and fertility. The main hypothesis is then developed from the preceding discussion. Subsequently, the data that was used and the applied method of analysis will be discussed. Next, results of the empirical analyses are presented. The conclusion then draws together the main findings.

The Development of Maternity Leave and Pay Regulations in Great Britain

Maternity allowance, which became available in 1948 with the passing of the 1946 National Insurance Act, was the first form of financial support for mothers during employment interruptions covered by statutory regulations in Great Britain (Table 1). However, women only qualified for maternity allowance if they paid their own insurance contributions. Until the passing of the 1975 Social Security Pensions Act, married women had the option to opt out of insurance payments, and instead to be insured on the basis of their husbands’ contributions. In the period up to the mid-1970s, since there were important financial incentives to do so, it is likely that many mothers had opted out of paying their own insurance contributions, and were thus not eligible for maternity allowance. Those who did have their own insurance had to have paid contributions for at least 26 weeks within the year preceding the 13th week before the baby was due, and have paid, or if they were unemployed or ill have credited to them, an additional 24 weeks of contributions. While maternity allowance provided some financial support during employment breaks, it was not accompanied by a right for mothers to return to their former job.Footnote 1 (Reid 1976a; The Institute for Fiscal Studies 2008; Coote and Gill 1974; National Audit Office 2005; Medical Care Research and Review 1946; Upex and Morris 1981).

Statutory maternity leave (in other words, the right of reinstatement into the previous job) was introduced in 1976. This right was conditional on having worked full-time (16 or more hours a week) for 2 years for the same employer by the 11th week before the expected week of childbirth, or 5 years if working for 8–15 hours a week. Employees who fulfilled these conditions had the right to return to work at any time until 29 weeks after childbirth. Maternity pay, as an actual form of income replacement, became available starting in 1977 at a level of 90% of previous earnings for a duration of 6 weeks. From this, the current level of maternity allowance was subtracted, whether a woman actually received maternity allowance or not (McRae 1991; Freedland 1976; Reid 1976b; Dex et al. 1996; Daniel 1980).

In 1987, a flat-rate statutory maternity pay to be administered by employers was introduced. The eligibility requirement was to have been employed with the same employer for 26 weeks into the 15th week before the baby was due. However, mothers’ right to retain their jobs as well as the 6 weeks of maternity pay at 90% of previous earnings still depended on longer employer tenure. Now, the requirement was to have been employed with the same employer for 2 years (or 5 years for part-time employees) into the 15th week before childbirth (Gregg et al. 2003; Conaghan 1987; McRae 1991).

Starting in 1994, there no longer were any differences in maternity leave regulations by hours of work. Furthermore, part of maternity leave became unconditional. All women now had a right to 14 weeks of leave. Continuous employment with the same employer for two years gave the right to return to work at any time until 29 weeks after childbirth. The condition for 6 weeks of maternity pay at 90% of previous income was now to have had 26 weeks of insured employment with the same employer into the 15th week before the expected week of childbirth (Gregg et al. 2003; Lourie 1999).

Unconditional leave was extended to 18 weeks in 2000, and women who had been continuously employed with the same employer for 1 year had the right to return at any time until 29 weeks after childbirth. The regulations for maternity pay remained unchanged (Gregg et al. 2003; European Commission 2002a; Lourie 1999).

The present study period only runs to the end of 2000. Therefore, changes in maternity leave and pay regulations after the year 2000 will not be relevant for the empirical analyses. None-the-less, recent changes in maternity leave and pay will be briefly presented in the following in order to give an overview of current developments and in order to put the findings into context.

In 2003, for children born after 5 April 2003, more extensive leave regulations were introduced. Maternity leave was extended to 26 weeks unconditional and 26 weeks additional leave. The latter depended on having been continuously employed with the same employer for 26 weeks by the beginning of the 14th week before the expected week of childbirth (Department of Trade and Industry 2003a; Gregg et al. 2003).

For mothers of babies born after 31 March 2007, all 52 weeks of maternity leave have been made unconditional of employment duration. The length of maternity pay has been extended to 39 weeks. However, to receive 90% income replacement for the first 6 weeks and an employer-administered flat-rate for the remaining period, women have to already have been employed with the same employer before the beginning of pregnancy. Women who do not fulfill this condition are eligible for maternity allowance for 39 weeks (Department of Trade and Industry 2006c).

Between 1980 and 2006, women working in firms with fewer than 6 employees could not be sure their right of reinstatement applied. In this period, small firms with less than 6 employees were not obliged to reemploy women after maternity leave if they could prove that it was not reasonably practicable. In addition, it appears that women in small firms had greater difficulties claiming their right to maternity pay than women working in larger firms (Smith 1985; Ellis 1986; Daniel 1980; The Maternity and Parental Leave etc. and the Paternity and Adoption Leave (Amendment) Regulations 2006).

While this paper focuses on maternity leave and pay and their potential impact on fertility timing, statutory maternity rights in Great Britain actually encompass four separate categories of rights: the right to time off for ante-natal care, the right to maternity leave and reinstatement into the former job, the right to maternity pay, and the right to protection against unfair dismissal because of pregnancy (Upex and Morris 1981; Department of Trade and Industry 2003a). The right to protection against unfair dismissal because of pregnancy was introduced with the passing of the 1975 Employment Protection Act (Baker 1976; Daniel 1980). Just as in the case of maternity leave, this right was conditional on the length of employment with the current employer. Initially, the necessary employment duration was 6 months, and was then increased to a year in 1979, and to 2 years in 1985 (P.L.D. 1979; R.W.B 1985). In 1993, dismissal because of pregnancy was ruled ‘automatically unfair’. It was thus set apart from other ‘ordinary unfair’ reasons for dismissal in that no particular length of service was required to appeal against dismissal on these grounds (Clarke 1995). Next to the tenure requirements for maternity leave then, the tenure requirements for the right to protection against unfair dismissal because of pregnancy could have provided an additional incentive to postpone motherhood. This may have particularly been the case in the period 1985–1993, when 2 years of tenure were necessary to qualify for this right.

In recent years, leave rights have not only become more extensive for mothers, but for fathers as well. Since 2003, fathers can now take two weeks paid paternity leave. The condition is that they need to have worked for their employer for 26 weeks the 15th week before childbirth (Department of Trade and Industry 2006b).

In addition to maternity leave and paternity leave, parental leave was introduced in December 1999. The difference to maternity and paternity leave is that parental leave can be taken at any time up to the child’s 5th birthday. Parental leave involves the right to 13 weeks unpaid leave per parent. Parents have to have been employed with the same employer for 1 year continuously (European Commission 2002b; European Commission 2002a; Department of Trade and Industry 2002; Department of Trade and Industry 2006a; Department of Trade and Industry 2003b).

A provision that is likely to be useful to many returning from leave was introduced in 2003. This is the right to apply for a flexible work schedule. Parents of children aged under 6 have the right to make a formal request for a work schedule that differs from the organization’s regular work schedule. This could, for example, be part-time work or irregular shift work. The employer must seriously consider the request and can decline it for business reasons only. The employee then has the right to appeal against a refusal of the request to work flexibly (Department for Business, Enterprise, and Regulatory Reform 2008).

Maternity Leave Regulations, Employment, and Fertility

The aim of this paper is to determine whether women in Great Britain postponed first birth until they had acquired enough employer tenure to meet maternity rights requirements. The reasoning here is that maternity leave can strongly influence mothers’ employment trajectories by guaranteeing job retention and thus enabling a smooth return to employment. Therefore, employees should have had a strong incentive to postpone first birth until they were eligible for maternity leave. Qualification for maternity pay, available at a level close to former earnings, should also have provided an important incentive to postpone first birth after starting a new job.

This section sets out by reviewing some important studies on the influence of maternity leave on returns to employment in Great Britain, as well as on the levels of receipt of maternity pay by qualifying mothers. Only given that access to maternity leave is indeed important for employment outcomes and that formal eligibility for maternity pay actually leads to higher rates of receipt is it reasonable to expect that women drew their eligibility for these maternity rights into consideration when making fertility decisions. The second part of this section summarizes findings on fertility effects of maternity leave regulations in Sweden and discusses implications for the British context. This is because very little research on Britain has dealt with implications of changes in maternity leave for levels of fertility. For Sweden by contrast, the connection between maternity leave regulations and fertility has been very closely examined.

Research on Maternity Leave and Returns to Employment in Great Britain

The present study examines whether the eligibility requirements for maternity leave and pay led to a postponement of first birth. The background assumption for this research question is that eligibility for maternity rights provided benefits for mothers. It is much more likely for women to have aspired eligibility for maternity leave if maternity leave was indeed beneficial to mothers’ employment careers. As discussed below, empirical findings on the effect of eligibility for maternity leave on job retention are mixed. Fulfilling the formal requirements for maternity rights did on the other hand clearly raise the probability of receiving maternity pay.

Daniel (1980), studying mothers of children born at the beginning of 1979, does not find any association between qualifying for maternity leave and returning to the same employer by shortly after the end of the statutory leave period of 29 weeks. However, mothers who had the necessary amount of working hours and employer tenure to qualify for maternity rights were largely able to claim maternity pay. Of mothers who met the formal conditions to qualify for statutory maternity pay, 88% actually received maternity pay, compared to only 10% of those who did not formally qualify.

By the end of the 1980s, an association between qualifying for maternity leave and returning to the same employer seems to have emerged, at least as indicated by descriptive results. McRae (1991) shows that for mothers of babies born in December 1987 and January 1988, of those who qualified for maternity leave 39%, and of those who did not qualify only 21% had returned to the same employer by shortly after the end of the statutory leave period of 29 weeks. Multivariate analyses also initially showed a significant positive effect of eligibility for maternity leave on the odds of returning to employment. However, after the introduction of a variable for maternity pay, eligibility for maternity leave loses significance at the 5% level (McRae 1991, 1993). Partly, this might have to do with some overlap between the maternity pay and maternity leave variables, since the eligibility condition at least for higher-level maternity pay was the same as for maternity leave.

Just like the findings by Daniel (1980) for 1979, the findings by McRae (1991) for 1988 also indicate a strong association between formal eligibility and actual receipt of statutory maternity pay. Of women who qualified for flat-rate statutory maternity pay, 86% actually received this benefit, compared to 24% of those who did not appear to qualify. Of those who seemed to qualify for higher-rate statutory maternity pay, 73% actually received it, compared to 12% of those who did not appear to formally qualify. While for the purpose of the present study, this shows that there is a clear association between qualification for and receipt of maternity pay, the findings by Daniel (1980) and McRae (1991) do however also generally show that there were substantial problems gaining access to maternity pay among many who were eligible.

Waldfogel et al. (1999), studying 1958 cohort members, also initially find positive effects of eligibility for maternity leave on job retention at 12 months after birth, which at the time was about half a year after the end of maternity leave. However, in subsequent models, the authors find that the effect of maternity leave on employment reentry disappears when controlling for employment experience. The problem here though is that effects of employment experience and maternity leave are extremely difficult to separate, since employer tenure is the condition for eligibility for maternity leave.

In descriptive analyses for the years 2000–2001, Geisler (2006) finds that higher levels of education are associated with higher rates of return to employment at points in time when supplementary leave periods typically end. This results in altogether higher probabilities of having returned by the end of the observation period at around 9 months after birth. Given that higher educated women’s greater propensity to return when supplementary leave periods typically end is at least to some extent due to their greater eligibility for supplementary maternity leave and not only to greater work orientation, this would indicate that maternity leave is indeed important to mothers’ employment continuity.

Gregg et al. (2003) also find indications that the introduction of maternity leave may have helped mothers to return to employment more quickly. Across the years 1974–2001, they find increases in mothers’ employment especially at short durations after birth, when children are less than 1 year old. It appears that the introduction and expansion of the right to maternity leave has increasingly enabled mothers to return to employment while their child was still very young.

The studies reviewed so far focused on the impact of maternity leave on employment in the medium-term. Dex et al. (1998) by contrast investigate long-term effects. The authors find a positive effect of having interrupted employment for no longer than 8 months around the birth of the first child on employment in any given subsequent month up until age 33. The authors assume that those women who interrupted employment for no longer than 8 months were on maternity leave. Their findings indicate that quick returns to employment, presumably enabled by maternity leave, have positive long-term employment effects.

The research reviewed above has analyzed the effect of maternity leave on mothers’ returns to employment. Very little research for Great Britain has been done on effects of maternity leave on fertility. One study that does look into potential effects on fertility is a cross-country macro-level time series analysis by Gauthier and Hatzius (1997). The authors use time series data from 22 countries for the years 1970–1990. Neither in a model including all countries, nor in models for country sub-groups do the authors find any significant effect of the length of maternity leave or the height of maternity pay on the total fertility rate. Possibly, though, this may have to do with difficulties in identifying individual-level causal effects on the macro-level. In the next section, studies using micro-level models that have found effects of maternity pay policy on fertility for Sweden will be reviewed.

This section has reviewed studies on Britain that have mostly focused on impacts of maternity leave on mothers’ return patterns to employment. It appears that in the early period just after the introduction of maternity rights legislation, qualification for maternity leave did not yet have any effect on job retention. Some later studies have found positive effects of taking maternity leave on probabilities of returning to employment, so long as employment experience and maternity pay were not controlled for. Because employer tenure was the eligibility criterion for maternity leave, and eligibility criteria for maternity pay and maternity leave partially coincided, effects of maternity leave, maternity pay, and employment experience are very difficult to separate. It is unclear whether it was the formal qualification for maternity leave, or greater attachment to an employer among those with longer tenure that led to higher reemployment rates. Even when they did not make use of it though, women may still have valued the option to return to employment, as pointed out by Daniel (1980).

Apart from qualification for maternity leave, qualification for higher-level maternity pay provided a further incentive to postpone first birth across the first years of employment. Higher-level maternity pay was set at 90% of previous earnings for a duration of 6 weeks. For most full-time employees, this will have amounted to substantially more than flat-rate maternity pay or allowance.

Thus, eligibility for higher-level statutory maternity pay certainly provided an incentive to postpone fertility. Eligibility for maternity leave potentially provided an additional incentive. Therefore, the hypothesis that will be tested in the “Empirical Results” section is that women postponed first birth until they had acquired enough employer tenure to qualify for maternity rights.

Because little research has been done on fertility effects of maternity leave policy in Britain, the next section will review studies on Sweden, where this relationship has been examined quite closely.

Effects of Maternity Pay Policy on Fertility in Sweden

Several studies for Sweden have found effects of changes in maternity pay policy on the timing of fertility. In Sweden, the level of income compensation during parental leave is linked to the length of the birth interval. This has been found to influence the timing of higher order childbearing (Hoem 1993; Andersson 2004). The findings for Sweden show that family policies can influence peoples’ decisions about when to have children. Against this background, the hypothesis will later be tested that women in Great Britain postponed first birth until they had acquired enough employer tenure to qualify for maternity leave.

In Sweden, the height of income replacement during parental leave depends on parents’ previous level of income. In the 1970s, a policy reform was introduced to the effect that parents can keep the level of income compensation they previously received during parental leave after having a child even after having further children, as long as the children’s birth dates are spaced closely enough. Thus, if a parent initially works full-time before having children, but then switches to part-time or does not return to work at all after having a child and then has a further child, income replacement is still based on their level of income before the first birth, if the next child is born in close sequence. The maximum length of the birth interval that allowed continued eligibility for the previous level of compensation was 12 months in 1974 (or up to 15 months including sick leave and vacation), and was extended to 15 months in 1979, 24 months in 1980, and 30 months in 1986 (Hoem 1990).

Hoem (1993) finds that higher order birth rates increased at all ages of the youngest child after 1978. However, the increase here is especially strong for women whose youngest child is only 1 year old. This is the only group to benefit from the extension of income replacement. After 1985, when the eligibility interval was extended to 30 months, there is a much stronger increase in 2nd and 3rd birth rates for mothers of 2-year-olds than for mothers of 2½ year-olds. It is likely that the former are responding to their new eligibility for continued income replacement after having a further child.

To further verify whether the shortening of birth intervals in Sweden in the 1980s was really related to the reform of maternity pay policy, and not just a result of women’s generally increasing attachment to the labor market, Andersson (2002) compares the development of fertility timing patterns in Sweden to those in neighboring Norway. Between the years 1980 and 1990, 2nd birth rates by the age of the first child did not change in Norway, although they increased at short birth intervals in Sweden. Also, while 3rd birth rates increased in both countries, they did so much more strongly at short birth intervals in Sweden than in Norway. In a further comparison, Andersson (2004) finds that in Denmark, in contrast to Sweden, only the level of 2nd birth rates increased, while the pattern of 2nd birth rates by age of the first child remained the same. These comparisons give further evidence that it was the maternity pay reform that was responsible for the shortening of the birth intervals in Sweden.

Research Question

The studies reviewed in the previous section provide evidence of family policy effects on fertility in Sweden. The empirical analyses that will be presented in the following aim to investigate whether the special requirements for maternity leave and pay similarly affected first birth timing in Great Britain. In Great Britain between 1976 and 1994, women working full-time had to have been employed with the same employer for 2 years in order to qualify for these maternity rights. The research question to be investigated here is whether women in Great Britain postponed childbearing until they had acquired 2 years of employer tenure. In contrast to the maternity pay policy in Sweden, that constituted a ‘speed premium’, as it is popularly referred to (Andersson et al. 2006), the maternity rights regulations in Great Britain can be expected to have caused a postponement of births. The policies in the two countries have in common that the group of people to whom they apply is very closely defined. Therefore, possible effects should be easily identifiable in terms of differences in fertility patterns between the group to whom the regulation applies and those to whom it does not apply.

The maternity pay reforms in Sweden had the potential to affect higher order birth timing. Maternity rights policy in Great Britain, on the other hand, could in principle have affected birth timing at all birth orders. However, only full-time employees were eligible for maternity leave and pay after 2 years of employment, the requirement for part-time employees being 5 years of tenure. Most women without dependent children in Great Britain are employed full-time (Twomey 2002).Footnote 2 This applies especially before the birth of their first child. However, many return to part-time employment after their children are born (Twomey 2002; Hillmert 2001; Fagan and Rubery 1996). It does not seem plausible that mothers of a first or second child working part-time would postpone their next birth for as long as 5 years in order to qualify for maternity leave. A postponement of 2 years for full-time employees seems more realistic. Full-time employed mothers are likely to be a very select, particularly work-oriented group though. For the empirical analyses below, it might therefore be problematic to include mothers in models testing the effect of full-time employees’ maternity leave eligibility on birth timing. While full-time employment is standard for childless women, this is not the case for mothers.Footnote 3 In addition, determinants of higher order births differ strongly from determinants of the transition from childlessness to first birth. For instance, effects of education generally run in opposite directions for first births as compared to higher order births (Kreyenfeld 2002; Kravdal 2001) and for higher order births, controls for age of the youngest child would be necessary. This would further complicate including higher order births in the model. For these reasons, the models estimated below are for the transition from childlessness to first birth only.

In view of these considerations, the hypothesis that will be tested below is that full-time employed women in Great Britain postponed first birth until they had acquired enough employer tenure to qualify for maternity leave and pay, once it was introduced in 1976. This type of a pattern is not expected for the time period before 1976, because there was not yet any incentive to postpone first birth at that time. After 1994, tenure effects on first birth timing are expected to have become weaker, since maternity pay at 90% of previous earnings as well as 14 weeks of leave were now available without having to have had any duration of employer tenure before the beginning of pregnancy.

Data and Method

The data used for this study is from the British Household Panel SurveyFootnote 4 (BHPS). The advantage of BHPS data is that it includes complete retrospective employer and fertility histories. These give exact lengths of employer tenure at any point in time as well as the dates of birth of each child, information that is necessary to test the hypothesis developed above. The BHPS began in 1991 and respondents are surveyed once a year. At each interview, monthly employment information is collected for the past year. The retrospective employment histories additionally give information on all employment spells that took place before the start of the panel. For the following analyses, retrospective parts of the BHPS were combined with panel data. The study period refers to the years 1955–2001.

There is a problem with the retrospective employer data used here that had to be dealt with. It is not possible to distinguish whether those who are not employed are unemployed or have returned to education after having left education for the first time. Up to about 22 years of age, many of those who are not employed are in education. After that age, the proportion of the not employed who are in education is much lower. Because fertility is very strongly determined by participation in education (Rindfuss et al. 1988; Blossfeld and Huinink 1991), but it is not possible to identify those who are in education in the data, the analyses were restricted to women over 22 years of age. This leaves a sample size of 2560. During the study period, 1615 first children were born.

As mentioned in the section on the development of maternity leave and pay between 1980 and 2006, women working in firms with fewer than 6 employees could not be sure their right of reinstatement would apply, and had greater difficulties claiming maternity pay. Therefore, strictly speaking, effects of employer tenure on fertility timing should be expected to be stronger for women working in firms with 6 or more employees. However, in the data, it was not possible to distinguish employees by firm size.

In order to be able to take into account effects of time-varying variables such as employment status and employer tenure, the method of analysis that was chosen is event history analysis. The formula for the model that was estimated is the following:

The dependent variable is the log risk of first conception ln h i (t). The date of first birth was backdated by 9 months. This was done in order to study the decision to have a first child. Women’s employment status often changes between the beginning of pregnancy and the date of birth. Therefore, in order to obtain the correct causal order of events, it is important to take into account the employment characteristics at the time the decision to have a first child was made. This also calls for a reformulation of the tenure requirements for maternity rights as they would apply to the beginning of pregnancy. As described above, the requirement for maternity leave and pay was that a woman had to have been employed for 2 years with her employer by the 11th week before the expected week of childbirth. That translates into 18 months of employer tenure at the beginning of pregnancy.Footnote 5

The baseline duration used for the model is age (t). Accordingly, y(t) is the log baseline risk of first conception. Independent variables, given by w ik (t), are educational attainment as well as an interaction between time period, employment status,Footnote 6 and employer tenure. The measure of employer tenure used here refers to the duration of employment with the same employer, not total employment experience. This is because only employment duration with the same employer is relevant for eligibility to maternity leave. The categories used for educational attainment are no school degree or CSE 2-5, GCSE D-G, or O-level D-E (‘no/low education’), CSE 1, GCSE A-C, O-level before 1975, or O-level A-C (‘medium education’), higher school certificate or A-level (‘high education’). Many respondents with A-level school degrees also have post-secondary degrees. Unfortunately though, it was not possible to further differentiate by level of post-secondary education. This is because the date they attained their post-secondary degree was not available for the majority of respondents. A table with occurrences and exposures for the independent variables is included in the appendix.

Empirical Results

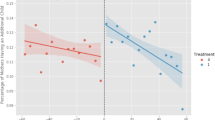

The empirical investigations presented in this section aim to determine whether an effect of employer tenure on risks of transition to first pregnancy set in as soon as statutory maternity rights were introduced in 1976, as hypothesized above. Table 2 shows the results of the model estimated for the risk of transition to first pregnancy. Figure 1 illustrates the effects of time period and employer tenure for women who were employed full-time. Before maternity leave and pay were introduced, in the first time period between 1955 and 1965, there is hardly any difference in risks of first pregnancy before and after 18 months of employer tenure. This is in line with the expectations. Since statutory maternity leave and pay had not yet been introduced there is not yet any incentive to postpone first pregnancy until after 18 months of employer tenure. In the next time period, however, between 1965 and 1976, an effect of employer tenure sets in, although still there was not yet any statutory maternity leave or pay. It is not immediately clear what could have caused this effect in this time period. The effect of employer tenure is then upheld across the whole period from 1976 to 1994. During this time period, in which the special eligibility requirements for maternity rights applied, an effect of employer tenure was indeed expected. Table 2 shows that risks of first pregnancy were 20% lower before compared to after 18 months of employer tenure in the time period 1976–1987 (0.74/0.93 − 1 = −0.20), and 30% lower in the time period 1987−1994 (0.68/0.97 − 1 = −0.30). After 1994, then, a large part of maternity leave became available without any tenure requirements, and no amount of tenure before the beginning of pregnancy was necessary any longer to qualify for maternity pay at 90% of previous earnings. This should have strongly decreased the incentive to postpone first birth. Accordingly, Table 2 and Fig. 1 show that after 1994, employer tenure no longer had any influence on risks of first pregnancy.

Relative risk of first pregnancy for full-time employees by time period and tenure (plot of estimates shown in Table 2)

The pattern for the risk of transition to first pregnancy found for the time period 1976–1994 does seem to fit the hypothesis very well that there was an effect of employer tenure during the years in which the eligibility restrictions for maternity leave and pay applied. The effect is even a bit stronger in the period 1987–1994 than in the period 1976–1987. It could be speculated that the stronger effect in the later time period is related to the eligibility conditions for protection against unfair dismissal due to pregnancy that applied then. Between 1985 and 1993, as described in the section on the development of maternity leave and pay, 2 years of tenure were necessary to qualify not only for maternity leave and pay, but for this right as well. However, the increase in the effect after 1987 is quite small and should probably not be over-interpreted.

It is difficult to understand why an effect of employer tenure set in earlier than 1976, before statutory maternity leave had been introduced. One explanation may be found by looking into contractual leave schemes that were in use even before statutory leave was introduced in 1976.Footnote 7 Coote and Gill (1974), referring to the period a few years before statutory leave was introduced, report that, while very uncommon in the private sector, maternity leave was to some extent available to public sector employees. Where it was available, though, it was often restricted to white-collar employees. They report maternity leave conditions in the public sector considered best practice by the Women’s Advisory Committee of the Trades Union Congress. Regulations considered best practice generally encompassed 18 weeks of leave, of which 4 weeks were fully paid, less maternity allowance, and the remaining 14 weeks paid at half the usual salary. The best practice for eligibility requirements were 12 months continuous service by 3 months before the expected date of birth. This might have given some incentive to postpone first pregnancy. Given these conditions, women would be eligible for maternity leave if they had acquired 6 months of employer tenure by the beginning of pregnancy. This is a shorter time period than the 18 months needed for the statutory leave and pay introduced in 1976. Therefore, when comparing risks of first pregnancy at more and less than 18 months of employer tenure, the expectation would be to find a smaller effect before than after 1976. The fact that maternity leave was only available at all to a subgroup of employees also leads to the expectation of a smaller average effect. However, there is not much difference in the size of the effect found for 1965–1976 as compared to 1976–1987 (Table 2). Thus, although the availability of maternity leave to some public sector employees before 1976 might partly explain the effect in 1965–1976, there must be other causes as well.

An additional explanation might be provided by findings by Daniel (1980). Daniel (1980) shows for 1979 (3 years after the introduction of statutory maternity rights) that over half of those public sector employees who lacked the length of employer tenure or working hours to be formally eligible for statutory maternity leave none-the-less reported that they qualified for the right of reinstatement, as compared to less than a third of not formally qualifying private sector employees. Similarly about a fourth of employees in the public sector received maternity pay although they did not fulfill the formal eligibility requirements, while among non-eligible employees in the private sector, this was the case for only 6% in large and 3% in small firms. Thus, more generous maternity leave and pay practices available in the public sector before 1976 may have partially continued to exist even after 1976. This may have prevented greater increases in the effect of employer tenure after 1976.

A further provision that was available before 1976 is maternity allowance, as described in the section on the development of maternity leave and pay. It is unlikely though that eligibility conditions for maternity allowance had much effect on fertility timing. Strictly speaking, only 26 weeks of employment in the year preceding the 13th week before the expected week of childbirth were necessary to qualify, which does not imply any amount of employment duration before pregnancy. However, women had to have paid while employed or, if they were receiving sickness or unemployment benefit, have credited to them an additional 24 weeks of insurance contributions in that year. Not everyone will have been eligible to have insurance contributions credited to them when not working. In that case, almost 6 months of employment before the beginning of pregnancy were necessary to qualify for maternity allowance. Since it was only paid as a flat-rate though, the incentive to postpone first birth in order to qualify for maternity allowance is not likely to have been very high. Especially though, it is likely that a large proportion of women did not qualify for maternity allowance at all. Before 1976, married women could opt out of paying their own insurance contributions and were then insured via their husbands. In that case, they were not eligible for maternity allowance.

Another explanation for the emergence of a tenure effect on first birth risks before 1976 could be that, in the course of their growing attachment to the labor market, women were increasingly postponing childbearing across the first years of employment. Even independent of eligibility for maternity leave and pay, women planning to return to employment may have felt that it was beneficial to become established in their careers before deciding to have a first child. For the period 1976–1994 as well then, it may not have actually been the maternity leave and pay regulations that caused the postponement of first births.Footnote 8

A further point that might be important to note is that the interpretation of a postponement of first birth may not be quite accurate. The expectation had been that with the introduction of maternity rights and the requirement to have been employed for 18 months, women would postpone first birth for that duration in order to qualify for maternity leave. However, the empirical results in Table 2 show that although first birth risks for women with less than 18 months of tenure were lower than for those with more than 18 months of tenure in the time period 1965–1994, they did not actually decrease for those with shorter tenure compared to earlier time periods, as would be implied by a postponement effect. Instead, first birth risks actually increased for those with more than 18 months of tenure, that is, for those who were eligible for maternity leave as of 1976. Moreover, this occurred at a time when there was a strong decrease in first birth risks for women who were not employed full-time. If the possibility to take advantage of maternity leave had any part in the emergence of a tenure effect on first birth risks, then it seems that it had the effect of raising first birth risks for those who were eligible, rather than depressing them for those who were not. After 1994, then, first births risks again dropped for women who were not employed full-time and for full-time employees with more than 18 months of tenure. For those who were newly eligible for maternity leave, those with less than 18 months of tenure, there was by contrast no decline in first birth risks. Thus, their new eligibility for maternity leave might have prevented the decline in first birth risks that occurred for all other groups.

Conclusion

This paper has investigated whether women in Great Britain postponed first birth until they met the tenure requirements necessary to qualify for statutory maternity leave and pay once they were introduced in 1976. Above, evidence was presented that rates of transition to first birth were higher for women who had acquired a sufficient amount of tenure to qualify for these maternity rights than for those who had not. In principle, this would support the hypothesis that first birth timing was adjusted to meet the tenure requirements for maternity leave and pay. However, the tenure effect on rates of transition to first birth set in even before these maternity rights were introduced in 1976. Partly, this effect may be related to contractual maternity leave and pay schemes that already existed for some groups of public sector employees before 1976. A further possible explanation is that women planning to return to employment felt that it was beneficial to become established in their careers before deciding to have a first child, even independent of maternity leave. In sum, it is not altogether certain whether the observed timing pattern for first birth was actually caused by the maternity leave and pay requirements that were in effect between 1976 and 1994. Although for the period 1976–1994 the pattern observed fits the maternity leave and pay requirements very well, it appears that other causes at least contributed to the tenure effect on first birth rates as well.

Notes

At the outset in 1948, maternity allowance was paid at a standard rate of £1.80 a week. The current standard rate of maternity allowance is £117.18. Between its introduction in 1948 and the present, there were numerous changes concerning supplements for dependents, earnings-related elements, differences in rates by employment status 3 months before childbirth, as well as earnings thresholds. Since the year 2000, maternity allowance is paid either at the standard rate or at 90% of average previous earnings, whichever is less.

Of all employed women aged 16–59 without dependent children, 68–70% were employed full-time in the years 1991–2001 (Twomey 2002). However, many of the women in the sample are likely to be mothers of adult children who have left the household. These women may have previously experienced work interruptions and have switched to part-time employment while their children were young. Even after their children have left home, their labor market status is still likely to differ considerably from that of childless women. The level of full-time employment can thus be expected to be higher for truly childless women. This is reflected in the percentage of exposure time accounted for by full-time employment in the present study. The exposure time used for the present study of transitions to first birth refers only to women who were as of yet childless. Here, full-time employment accounts for 88% of all exposure time in employment and part-time employment only accounts for 7%, as can be seen in the appendix.

Of all employed women aged 16–59 with a youngest child aged 0–4, 65–67% were employed part-time in the years 1991–2001 (Twomey 2002).

The BHPS data used in this study were made available through the ESRC Data Archive. The data were originally collected by the ESRC Research Centre on Micro-social Change at the University of Essex (now incorporated in the Institute for Social and Economic Research). Neither the original collectors of the data nor the Archive bear any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

Between 1987 and 1994, actually 19 instead of 18 months of tenure were necessary at the beginning of pregnancy, since now the requirement was to have had 2 years of tenure the 15th week before childbirth. However, even if 19 months of tenure were required to be eligible for maternity leave after 1987, this still implied that women had to postpone the decision to have a child for over 18 months.

The definition of full-time employment in the data, based on respondents’ self-appraisal, is unlikely to coincide with the definition of full-time employment relevant for maternity leave eligibility of 16 or more hours a week. However, even according to the respondents’ own presumably stricter definition of full-time employment, the great majority in the sample is employed full-time, as can be seen in the appendix. Those classified as full-time employees in the sample will almost certainly qualify as full-time employees in terms of the eligibility requirements for maternity leave. Some respondents classified as part-time employees in the sample might however actually qualify as full-time employees in terms of the eligibility requirements for maternity leave. Since, even according to the definition used in the data, the fraction of part-time employees is very small though, the overall extent of misclassification can be assumed to be minimal.

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for calling attention to these points.

Ibid.

References

Andersson, G. (2002). Fertility developments in Norway and Sweden since the early 1960s. Demographic Research, 6(4), 67–86.

Andersson, G. (2004). Childbearing developments in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden from the 1970s to the 1990s: A comparison. Demographic Research. Special Collections, 3, 154–176.

Andersson, G., Hoem, J. M., & Duvander, A.-Z. E. (2006). Social differentials in speed-premium effects in childbearing in Sweden. Demographic Research, 14(4), 51–70.

Baker, C. D. (1976). Employment protection: Individual rights. Industrial Law Journal, 5, 65–79. doi:10.1093/ilj/5.1.65.

Blossfeld, H.-P., & Huinink, J. (1991). Human capital investments or norms of role transitions? How women’s schooling and career affect the process of family formation. American Journal of Sociology, 97(1), 143–168. doi:10.1086/229743.

Clarke, L. (1995). Pregnancy and dismissal: The interaction of statutory and contractual rights. Industrial Law Journal, 24(2), 170–176. doi:10.1093/ilj/24.2.170.

Conaghan, J. (1987). Statutory maternity pay under the Social Security Act 1986. Industrial Law Journal, 16, 125–129. doi:10.1093/ilj/16.1.125.

Coote, A., & Gill, T. (1974). Women’s rights: A practical guide. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Daniel, W. W. (1980). Maternity rights. The experience of women. London.

Department for Business, Enterprise, and Regulatory Reform. (2008). Flexible working: The right to request and the duty to consider. http://www.dti.gov.uk/employment/employment-legislation/employment-guidance/page35663.html.

Department of Trade and Industry. (2002). Parental leave. Summary guidance. http://www.dti.gov.uk/er/intguid1.htm.

Department of Trade and Industry. (2003a). Maternity rights. A guide for employers and employees. Babies due on or after April 6 2003. PL 958 (Rev 9).

Department of Trade and Industry. (2003b). Parental leave (PL510 Rev 1). A short guide for employers and employees. http://www.dti.gov.uk/er/parental.htm.

Department of Trade and Industry. (2006a). Parental leave. A short guide for employers and employees URN No: 06/566. http://www.dti.gov.uk/employment/employment-legislation/employment-guidance/page18480.html.

Department of Trade and Industry. (2006b). Paternity – leave and pay: A basic summary URN No: 06/547. http://www.dti.gov.uk/employment/employment-legislation/employment-guidance/page17139.html.

Department of Trade and Industry. (2006c). Pregnancy and work. What you need to know as an employee. Babies due on or after 1 April 2007. http://www.dti.gov.uk/employment/workandfamilies/maternity-leave-pay/guidance/page21116.html.

Dex, S., Joshi, H., & Macran, S. (1996). A widening gulf among Britain’s mothers. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 12(1), 65–75. doi:10.1093/oxrep/12.1.65.

Dex, S., Joshi, H., Macran, S., & McCulloch, A. (1998). Women’s employment transitions around child bearing. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 60(1), 79–98. doi:10.1111/1468-0084.00087.

Ellis, E. (1986). Parents and employment: An opportunity for progress. Industrial Law Journal, 15, 97–109. doi:10.1093/ilj/15.1.97.

European Commission. (2002a). Family benefits and family policies in Europe. MISSOC-INFO 01/2002.

European Commission. (2002b). MISSOC comparative tables on social protection in the member states. Maternity. http://europa.eu.int/comm/employment_social/missoc/2002/uk_part4_en.htm.

Fagan, C., & Rubery, J. (1996). The salience of the part-time divide in the European Union. European Sociological Review, 12(3), 227–250.

Freedland, M. R. (1976). The Employment Protection Act 1975. Individual aspects. The Modern Law Review, 39(5), 561–574.

Gauthier, A. H., & Hatzius, J. (1997). Family benefits and fertility: An econometric analysis. Population Studies, 51(3), 295–306. doi:10.1080/0032472031000150066.

Geisler, E. (2006). Women’s (re)-entry into the labour market after childbirth in the United Kingdom. M.A. Thesis, University of York, York.

Great Britain − Social Insurance Bill Passed in Commons (1946). Medical Care Research and Review, 3(3), 50–51.

Gregg, P., Gutiérrez-Domenech, M., & Waldfogel, J. (2003). The employment of married mothers in Great Britain: 1974–2000. Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Hillmert, S. (2001). Deregulierung des Arbeitsmarktes und relative Beschäftigungschancen: Das Beispiel Großbritannien. In P. A. Berger & D. Konietzka (Eds.), Die Erwerbsgesellschaft. Neue Ungleichheiten und Unsicherheiten (pp. 185–212). Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Hoem, J. M. (1990). Social policy and recent fertility change in Sweden. Population and Development Review, 16(4), 735–748. doi:10.2307/1972965.

Hoem, J. M. (1993). Public policy as the fuel of fertility: Effects of a policy reform on the pace of childbearing in Sweden in the 1980s. Acta Sociologica, 36, 19–31. doi:10.1177/000169939303600102.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). (2008). Fiscal facts. Benefit tables. Maternity allowance. http://www.ifs.org.uk/ff/indexben.php.

Kravdal, Ø. (2001). The high fertility of college educated women in Norway: An artefact of the separate modelling of each parity transition. Demographic Research, 5(6), 187–216.

Kreyenfeld, M. (2002). Time-squeeze, partner effect or self-selection? An investigation into the positive effect of women’s education on second birth risks in West Germany. Demographic Research, 7(2), 13–48.

Lourie, J. (1999). Family leave. House of Commons Library Research Paper 99/89.

The Maternity and Parental Leave etc. and the Paternity and Adoption Leave (Amendment) Regulations 2006.

McRae, S. (1991). Maternity rights in Britain. London: Policy Studies Institute.

McRae, S. (1993). Returning to work after childbirth: Opportunities and inequalities. European Sociological Review, 9(2), 125–137.

National Audit Office. (2005). Dealing with the complexity of the benefits system. London: National Audit Office.

P. L. D. (1979). Employment protection. Industrial Law Journal, 8, 173.

Reid, J. (1976a). New social security legislation. Industrial Law Journal, 5, 54–61. doi:10.1093/ilj/5.1.54.

Reid, J. (1976b). Women in employment. The New Legislation. The Modern Law Review, 39(4), 432–451.

R. W. B. (1985). Longer qualifying periods for unfair dismissal. Industrial Law Journal, 14, 144.

Rindfuss, R. R., Philip Morgan, S., & Gray Swicegood, C. (1988). First births in America. Changes in the timing of parenthood. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Smith, I. T. (1985). Employment laws and the small firm. Industrial Law Journal, 14, 18–32. doi:10.1093/ilj/14.1.18.

Twomey, B. (2002, March). Women in the labour market: Results from the Spring 2001 LFS. Labour Market Trends, pp. 109–127.

Upex, R., & Morris, A. (1981). Maternity Rights – Illusion or Reality? Industrial Law Journal, 10, 218–238. doi:10.1093/ilj/10.1.218.

Waldfogel, J., Higuchi, Y., & Abe, M. (1999). Family leave policies and women’s retention after childbirth: evidence from the United States, Britain, and Japan. Journal of Population Economics, 12, 523–545. doi:10.1007/s001480050112.

Acknowlegement

I would like to thank Michaela Kreyenfeld, Gerda Neyer, Gunnar Andersson, the two anonymous reviewers, as well as all the members of the team on Institutional and Political Approaches to Family and Fertility Dynamics for valuable comments and advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zabel, C. Eligibility for Maternity Leave and First Birth Timing in Great Britain. Popul Res Policy Rev 28, 251–270 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-008-9098-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-008-9098-1