Abstract

Though most scholars of race and politics agree that old-fashioned racism largely gave way to a new symbolic form of racism over the course of the last half century, there is still disagreement about how to best empirically capture this new form of racism. Racial resentment, perhaps the most popular operationalization of symbolic racism, has been criticized for its overlap with liberal-conservative ideology. Critics argue that racially prejudiced responses to the items that compose the racial resentment scale are observationally equivalent to the responses that conservatives would provide. In this manuscript, I examine the racial resentment scale for differential item functioning (DIF) by level of adherence to ideological principles using the 1992, 2004, and 2016 American National Election Studies. I find that responses to some of the racial resentment items are, indeed, affected by ideology. However, the problem is largely confined to 2016 and more egregious with respect to ideological self-identifications than adherence to ideological principles. Moreover, even after correcting for DIF, the racial resentment scale serves as a strong predictor of attitudes about racial issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The measurement of racial prejudice, and the substantive inferences about the impact of racial prejudice that follow from those measurement strategies, has been the subject of scholarly debate since the “symbolic racism,” or “new racism,” construct was first developed by social scientists. Racial resentment, one operationalization of the symbolic racism construct, is ground zero for most of the controversy, with proponents of the measurement strategy demonstrating its comprehensive explanatory power, and skeptics challenging its validity. However, to diminish the perspectives that scholars have taken on racial resentment to two opposite sides would be an egregious oversimplification of the robust debate over the measurement strategy developed by Kinder and Sanders (1996). For instance, many scholars occupy a middle position, challenging particular aspects of the racial resentment items, and sometimes even offering adjustments or alternatives (e.g., Neblo 2009b; Wilson and Davis 2011).

In this manuscript, I address one of the lingering critiques of the racial resentment scale: that responses to the items that compose the scale are caused by adherence to (conservative) ideological principles, in addition to, or rather than, racial prejudice. On its face, this perspective seems at least plausible. Affirming the role of hard work and denying special government handouts is to support the core values of individualism and limited government that lie at the center of conservatism. Though detractors have provided evidence supporting this thesis (e.g., Sniderman and Carmines 1997; Sniderman and Piazza 1993; Sniderman and Tetlock 1986), I contend that this work has overlooked a central component of the main argument. Namely, the principled facet of the “principled conservatism” thesis has remained untested, in favor of a consideration of the relationship between liberal-conservative self-identifications and racial resentment.

Rather than focus on the differences between liberal and conservative identities, I center my empirical scrutiny of the principled conservatism thesis on individual-level variation in the level of adherence to liberal-conservative ideological principles. Of course, some are more principled than others, as Ellis and Stimson (2012) demonstrate through their exploration of the incongruence between “symbolic” and “operational” ideological orientations. I use a host of survey items on the 1992, 2004, and 2016 American National Election Studies (ANES) to capture individual adherence to conservative ideological principles and to examine whether the racial resentment items exhibit significant differential item functioning (DIF)—a scenario when responses to survey items differentially tap the latent construct of interest (racial resentment) because of some confounding factor (ideology).Footnote 1 I find very weak evidence of DIF in 1992 and 2004 with respect to only ideological self-identifications. Evidence is more mixed in 2016, though DIF remains more prevalent when it comes to self-identifications than adherence to ideological principles. Regardless of the extent of DIF, the racial resentment scale remains correlated with important political predispositions and continues to display a great deal of explanatory power in models of specific issue attitudes even after correcting for DIF.

Though the principled conservatism thesis is partially supported by empirical evidence from 2016, the “contamination” of the racial resentment items by conservative principles is not sufficiently problematic to substantively alter any of the major inferences that have been made using the racial resentment scale. Even corrected for the DIF-associated influence of adherence to conservative principles, racial resentment serves as a substantively strong predictor of attitudes about issues like governmental aid to minorities and preferential hiring for blacks, after appropriately controlling for other variables such as egalitarianism, moral traditionalism, and partisanship. Thus, it seems, given the evidence presented below, that the relationship between ideological identities and racial resentment observed by others has little to do with adherence to ideological principles.

More than providing disconfirmatory evidence for the principled conservatism thesis, these findings have a number of important substantive implications. That ideological principles are not seemingly causing the observed relationship between racial resentment and ideological self-identifications prompts the question of what does. Perhaps conservative self-identification, as a social identity (Malka and Lelkes 2010), has an inherent racial component to it—it comes with a particular orientation toward blacks and other racial groups. The connection between conservative identity and racial resentment could be the product of myriad value orientations, social factors, or psychological mechanisms that have little to do with political ideology. Alternatively, political communications from conservative leaders may guide, or even manufacture, this orientation, consistent with the “top-down” model of public opinion. The literature on the use of racial “code words” or “dog whistles” in American electoral politics and policy framing provide support for precisely this proposition (e.g., Gilens 1999; Mendelberg 2001). Regardless, the findings presented below suggest that the basic nature of the causal relationship between ideological self-identification and racial resentment is still not well-understood, though it is surely important to a complete account of the role of racial orientations in American politics.

Background

As the effects of the Civil Rights movement spread throughout American culture, so too did a new form of racism against blacks. This new form of racism, sometimes referred to as “symbolic” or “modern” racism, is distinct from old-fashioned, traditional forms of racism in at least two key ways. First, pre-Civil Rights era racism was based heavily on the idea that blacks were biologically inferior to whites. In particular, blacks were thought to be biologically predisposed to be intellectually inferior to, and more violent than, whites. Second, old-fashioned racism was expressed more explicitly than newer forms of racism (Tesler 2013), which rely more heavily on implicit cues, “code words,” and “dog whistles” (Mendelberg 2001). These explicit expressions came in the form of racially-charged language (e.g., the “n-word”) and behaviors designed to overtly punish or oppress blacks (e.g., refusing to hire blacks).

The symbolic racism construct does not deny that biological racism still exists for some individuals. Rather, it posits that racial prejudice towards blacks has largely shifted away from biological critiques to moral ones, whereby blacks are seen as violating the American ideals of individualism and hard work (Henry and Sears 2002; Kinder and Mendelberg 2000; Sears and Henry 2005). Symbolic racism is expressed through coded language—such as “welfare,” “inner cities,” and “thug”—that has become imbued with racial content and is used to cue racial prejudice toward blacks. Racial resentment is, perhaps, the most widely employed operationalization of symbolic racism. Kinder and Sanders (1996) describe racial resentment as “the conjunction of whites’ feelings toward blacks and their support for American values, especially secularized versions of the Protestant ethic” (p. 293). Racial resentment is measured via Likert-type responses to the following four statements:

-

1.

Irish, Italians, Jewish, and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors. (Favors)

-

2.

Over the past few years blacks have gotten less than they deserve. (Deserve)

-

3.

It’s really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites. (Try Hard)

-

4.

Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class. (Conditions)

Typically, the agree-disagree responses to these items are recoded so that larger numerical values denote more prejudiced attitudes. The responses are then summed or averaged to create a scale. The scale is highly reliable across samples and time, with reported Cronbach’s alpha reliability estimates typically exceeding 0.70 (e.g., Feldman and Huddy 2005; Kinder and Sanders 1996; Knuckey and Kim 2015). The racial resentment scale is also highly correlated with a host of attitudes, predispositions, and behaviors, including: partisanship (Sides et al. 2016; Tesler 2013), ideology (Rabinowitz et al. 2009; Neblo 2009b), authoritarianism (Hetherington and Weiler 2009), vote choice (Enders and Scott 2019), and attitudes about public policy issues (Tesler 2012). Kinder and Sanders (Kinder and Sanders 1996) use the substantively large relative effect of racial resentment on attitudes about racial issues as supporting evidence for the conclusion that racism is “the most important” consideration in the minds of white Americans when forming such attitudes about racial issues (p. 124).

Debate Over Racial Resentment

Though relatively few scholars have taken issue with the theoretical concept of racial resentment, many have voiced concerns regarding the strategy for measuring racial resentment, particularly the survey items constructed by Kinder and Sanders (1996). One such critique holds that the racial resentment items are merely placeholders for questions about racial policy attitudes. Schuman (2000) theorizes, with respect to the connection between the racial resentment items and racial policy attitudes, that the “strong association between them might be thought of as indicating somewhat different aspects of the same general construct, negative attitudes toward the need to help blacks, rather than as distinguishing cause from effect” (p. 307). In other words, perhaps the racial resentment items and racial policy attitudes serve as indicators of the same substantive dimension, rather than distinct, albeit related, dimensions of public opinion (Carmines et al. 2011).

Along similar lines, the most persistent and vocal criticism has questioned whether the racial resentment items tap a distinctly racial construct, or a more general, ideological one. I refer to this perspective, as others before me have (DeSante 2013; Feldman and Huddy 2005; Neblo 2009a; Wallsten et al. 2017), as the “principled conservatism thesis.” This perspective, developed most fully by Sniderman and colleagues (e.g., Sniderman and Carmines 1997; Sniderman and Piazza 1993; Sniderman and Tetlock 1986), asserts that adherence to conservative ideological principles causes what are interpreting as more resentful responses to the individual racial resentment items, especially those that deal with subjects like hard work and struggle. In other words, the basic sentiments of racial resentment, and even other measures of symbolic racism, can be viewed “as the clash of competing conceptions of the proper responsibilities of government and the appropriate obligations of citizens” (Sniderman et al. 2000, p. 238), rather than racism.

In some sense, proponents of symbolic racism seem to agree. Kinder and Sanders (1996), for instance, admit the connection between racial resentment and individualism—it is precisely their theory that racial prejudice has become intertwined with individualism. Kinder and Mendelberg (2000) attempt to demonstrate the nuance of the relationship between racial resentment and individualism by presenting the differential effects of the two constructs on racial and non-racial (at least, explicitly) issue attitudes. Where racial resentment predicts (lack of) support for racial issues like affirmative action, a non-racial, more general measure of individualism is more predictive of non-racial issues like a government-supported standard of living. Similarly, Sears et al. (1997) show that racial resentment is a powerful predictor of attitudes about racial issues in the face of controls for individualism and more abstract attitudes about social welfare.

Most recently, Wallsten et al. (2017) use a non-political test to demonstrate the strong racial prejudice element of racial resentment. Where attitudes about racial or non-racial political issues could plausibly have psychological foundations in both racial prejudice and ideological principles, attitudes about paying college athletes—the issue Wallsten et al. (2017) focus on—should have little to do with core beliefs about the role and size of government, or other ideological principles. Kam and Burge (2018) have also recently shed light on what precisely the racial resentment items capture by simply asking survey respondents for their (open-ended) reactions to the items. They find that negative attitudes toward blacks and denial of discrimination are both significant components of racial resentment among whites, as originally theorized by Kinder and Sanders (1996).

Principled or Conflicted Conservatism?

Regardless of the empirical evidence in support of racial resentment, the “principled conservatism” thesis, on its face, seems reasonable. Truly principled conservatives—those who steadfastly adhere to the core tenets of conservatism—likely would provide responses to most of the racial resentment items that could also be interpreted as more prejudiced. Of course, it is also a well known challenge of practitioners of survey research to construct items that serve as valid indicators of latent constructs, especially when the latent construct of interest is particularly sensitive or susceptible to social judgement, as racial prejudice is. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to consider whether the racial resentment items serve as valid indicators of a new form of racial prejudice.

In light of these concerns, many studies have considered the relationship between ideology and racial resentment (e.g., Feldman and Huddy 2005; Neblo 2009a; Valentino and Sears 2005). Liberal-conservative ideological self-identifications are unequivocally correlated—and usually quite highly so—with racial resentment (Enders and Scott 2019; Valentino and Sears 2005). In defense of the principled conservatism thesis, Sniderman et al. (2000) demonstrate that the effect of racial resentment on various issue attitudes is conditional on liberal-conservative self-identification, with the effect of racial resentment being static for conservatives. Feldman and Huddy (2005) arrive at a similar conclusion, finding that the effects of racial resentment on attitudes about racial programs were largely confined to self-identified liberals. More recently, DeSante (2013), utilizing an experimental research design, found that the most racially resentful whites, as opposed to less racially resentful whites, were more likely to allocate funds to offset the state budget deficit than allocated such funds to a black welfare applicant. This demonstrates a racial component of racial resentment, even accounting for principled conservatism. Thus, previous studies attempting to tease out the differences between racial resentment and conservative ideology have produced mixed conclusions.

I suspect that one potential reason for such varied inferences is construct operationalization. Where a wealth of studies have explored alternate operationalizations of symbolic racism (e.g., Tarman and Sears 2005; Wilson and Davis 2011) in an effort to circumvent the principled conservatism controversy, none have seriously considered that the operationalization of ideology is A) theoretically inconsistent with the claims central to the principled conservatism thesis or B) driving the “contamination” effects frequently observed in tests of the relationship between racial resentment and ideology. Indeed, nearly all studies of the relationship between ideology and racial resentment, save for some experimental approaches (e.g., DeSante 2013; Wallsten et al. 2017), operationalize ideology via the common self-identification item. Though the symbolic predispositions captured by such an item are an indisputably important ingredient of public opinion and political behavior, there is fairly weak evidence that they adequately operationalize adherence, or are analytically identical, to ideological principles. Indeed, this is a classic finding in public opinion research—the mass public is not highly constrained by ideological principles (Converse 1964).

Ellis and Stimson (2012) make the incongruence between self-identifications and adherence to ideological principles even plainer. Building on earlier work by Free and Cantril (1967), they distinguish between symbolic and operational ideological predispositions. The symbolic element of ideological self-identification captures the social identity aspect of ideology. The operational component captures “principle”—the extent to which individuals actually hold the policy views implied by the core tenets of American liberalism and conservatism. Ellis and Stimson (2012) demonstrate a wide gulf between symbolic and operational ideological orientations, especially when it comes to conservatives. Indeed, more than 30% of self-identified conservatives are found to be “conflicted”—they symbolically identify as conservatives, but hold liberal policy views.

Such a finding can have at least two implications for the principled conservatism thesis. First, the small proportion of principled conservatives in the mass public (15%) hints that the effect of adherence to conservative ideological principles on the relationship between racial resentment and issue attitudes is likely quite small. Even if the racial resentment items are “contaminated” by conservative beliefs to some extent, that this could be the case for such a small portion of the American mass public suggests that the problem at the center of the principled conservatism thesis is likely not particularly widespread or analytically troublesome. Second, the fact that symbolic and operational ideological orientations operate somewhat distinctly presents an opportunity for these components of ideology to relate to racial resentment in unique ways. Though “balanced” liberal-conservative ideological self-identification is highly correlated with racial resentment, perhaps level of adherence to conservative ideological principles is not so neatly (i.e., strongly, linearly) connected to racial resentment—the scale or responses to individual items. It is an investigation of precisely these possibilities to which I turn next.

Data & Analytical Strategy

In order to more comprehensively test the principled conservatism thesis, I require the Kinder and Sanders (1996) racial resentment items and indicators of adherence to conservative principles beyond basic liberal-conservative self-identification. Many of the American National Election Study (ANES) surveys contain both of such items, in addition to a host of useful control variables. I employ ANES data from 1992, 2004, and 2016.Footnote 2 Data from the 1990s and early 2000s are useful because this is precisely when much of the debate about racial resentment was taking place. Data from 2016, on the other hand, provides the strictest test of the principled conservatism thesis. Ideological self-identifications and racial resentment are more highly correlated today that they have been at any other point in modern American history (Enders and Scott 2019). If I find that principled conservatism does not account for a majority of the variance in the racial resentment scale under these conditions, then I will have reasonably robust evidence against the principled conservatism thesis. There is, then, a potential for the dynamic between racial resentment and ideology—especially of the symbolic sort—to have changed over time.

I operationalize adherence to conservative principles two different ways. Though being “principled” seems like a dichotomous concept in an ideal world, precisely who is and who is not principled simply cannot be cleanly empirically discerned. Therefore, I take a very conservative approach to defining and estimating principle, resulting in statistical estimates that provide a upper bound of the effect of principled conservatism on racial resentment. The first method I take to measuring principled conservatism involves constructing an additive scale of responses to a majority of the government spending questions found on the ANES. These questions ask respondents, “Should federal spending on _______ be increased, decreased, or kept the same?” The blank space is filled with objects—policy areas—such as public schools, welfare programs, child care, aid to the poor, and programs to protect the environment.Footnote 3 The “increased” option, which is the least principled (or wholly unprincipled) stance a conservative could take, is scored 0, “kept the same” is scored 1, and “decreased” is scored 2. Following Jacoby (2000), I then sum responses to these items, resulting in an operationalization of principled conservatism that is similar to the measure of operational ideology employed by Chen and Goren (2016) and Ellis and Stimson (2012). Not only is scoring principled conservatism along a continuum generous in its own right, but scoring the “kept the same” option as larger (i.e., more conservative), numerically, than the “increased” option allows for additional flexibility in defining adherence to core conservative beliefs.

The second operationalization of principled conservatism involves scaling individuals along a latent continuum of more abstract beliefs about the size and scope of government. The ANES asks three questions that serve as observable indicators of these beliefs. The base question asks, “Which of the two statements comes closer to your view?”:

-

1.

“Government has become bigger because the problems we face have become bigger” (0) OR “The main reason government has become bigger over the years is because it has gotten involved in things that people should do for themselves” (1)

-

2.

“We need a strong government to handle today’s complex economic problems” (0) OR “The free market can handle these problems without government being involved” (1)

-

3.

“There are more things the government should be doing” (0) OR “The less government, the better” (1)

Responses are coded as indicated above in parentheses. An additive index of the items ranges from 0 to 3, with 3 denoting the most conservative position. This scale, while being more specific in its content than the ideological self-identification item, is comprised of more abstract sentiments than the spending items detailed above. This allows a more complete and nuanced test of the principled conservatism thesis—the degree of precision and consistency in ideological orientations may affect the degree of empirical support for the theory.

Racial resentment is measured via the standard four items provided in the previous section. Respondents were able to answer from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” with a neutral midpoint, “neither agree, nor disagree.” Response options for two items are reflected so that all items are coded such that larger numerical values denote more racially resentful responses. Response options are coded 0–4 and summed to created an additive index ranging from 0 (low racial resentment) to 16 (high racial resentment). The distributions of the racial resentment scale and ideology measures appear in the Supplemental Appendix.

In the next section, I turn toward a detailed examination of the relationship between principled conservatism and racial resentment. The analysis is conducted in three steps. First, I consider the differential relationships between the three operationalizations of ideology and racial resentment. Next, I utilize a combination of item response theory and ordinal logistic regression to guide an analysis of the effect of principled conservatism on the individual items that compose the racial resentment scale. More specifically, I examine the items for differential item functioning according to adherence to conservative principles. This method is particularly well-suited for testing the principled conservatism thesis, as it asks whether the responses to survey items are being affected by something other than the latent construct of interest, racial prejudice. Finally, I compare the effects of the racial resentment scale that has been corrected for differential item functioning—or, freed from the contamination effects of principled conservatism—with those of the uncorrected scale when it comes to a host of attitudes about racial and recently racialized public policies.

Empirical Analysis

I begin my empirical analysis of the relationship between conservative ideological principles and racial resentment by first considering the extent to which the two measures of adherence to ideological principle relate to symbolic ideological self-identifications. Not only does evidence support the idea that symbolic and operational ideological orientations might be out of step (Ellis and Stimson 2012), but that relationship may have also changed over time. Strong correlations between the two types of ideology would obviate the necessity for this analysis—plenty of scholars have dissected the relationship between self-identifications and racial resentment.

Figure 1 includes correlations between self-identifications and both measures of ideological principle by year. The first feature to note is the increasing strength of the correlations over time. In 1992, the correlations between self-identifications and operational ideology are in the 0.20–0.30 range. As such, self-identifications are a far cry from accurate placeholders for adherence to ideological principles. These correlations increase to the 0.40–0.50 range by 2004, and then to the 0.50–0.60 range by 2016. This increasing congruence between symbolic and operational ideology may be due to several factors, including increasingly polarized cues from political elites (Druckman et al. 2013; Levendusky 2010) and a simplification of American political conflict along a unidimensional ideological space (McCarty et al. 2006).

Of course, the particular reason for this trend is not under consideration. Rather, I am interested in understanding how well operational and symbolic ideological orientations mimic each other, and how that changes over time. In 1992 there is only a very weak relationship between adherence to ideological principles and ideological self-identification. While the strength of the linear relationship between the two types of ideology does double by 2004, and increase a bit still through 2016, the magnitude of the correlations are far from impressive. That the operational ideology measures are correlated with self-identifications at 0.55 at the very best suggests that ideological identities are far from interchangeable with adherence to ideological principles. This allows for at least the possibility for self-identifications and adherence to ideological principles to relate to racial resentment in different ways.

Next, I consider the relationships between racial resentment and each of the three measures of ideology over time. The principled conservatism thesis predicts that those who more steadfastly adhere to conservative ideological principles should be more likely to provide seemingly more resentful responses, though such individuals are actually just expressing conservatism in a principled manner. The empirical manifestation of this claim would include, but not necessarily be limited to, larger correlations between operational ideological orientations and racial resentment than between ideological self-identifications and racial resentment. This should especially be the case in the 1992 data since American politics was less polarized and the mass public was less sorted at that time (Levendusky 2009).

Figure 2 depicts correlations between racial resentment and each measure of ideology by year. Like the correlations between ideological self-identifications and ideological principles, the correlations between racial resentment and all measures of ideology have increased over time. However, for each year, I observe a statistically and substantively stronger correlation between ideological self-identification and racial resentment than between either measure of adherence to ideological principles and racial resentment. This is precisely the opposite of what the principled conservatism thesis predicts. Not only is principle less related to racial resentment than is identity, but in 1992 these relationships are extremely weak. The correlation between abstract beliefs about the size and scope of government and racial resentment is not statistically distinguishable from 0, and that with spending preferences is a very weak 0.13. Even in a time of less polarization (e.g., McCarty et al. 2006) and less crystalized ideological identities (Kinder and Kalmoe 2017), ideological self-identifications are more correlated—by more than a factor of two—with racial resentment than is adherence to conservative ideological principles.

To sum up the results thus far, racial resentment is substantially more strongly related to ideological self-identifications than it is to either measure of adherence to ideological principles. Furthermore, we know from the analyses presented in Figure 1, and previous studies, that symbolic ideological predispositions do not completely square with operational ones (e.g., Claassen et al. 2015; Ellis and Stimson 2012). This suggests a potential problem for the principled conservatism thesis, and exemplifies why previous studies relying on ideological self-identifications may not have adequately captured the operational ideological principles at the center of this theory. Though many studies—indeed, a whole literature—has focused on the measure of racial resentment as a source of construct conflation when it comes to the relationship between modern forms of racial prejudice and ideology, no study has considered that the measure of ideology being employed is equally, if not more, problematic. Even the simple correlational analyses presented above suggest that this may be the case. I now turn toward an investigation of differential item functioning of the racial resentment indicators by ideological self-identification and level of adherence to ideological principles.

Differential Item Functioning Analysis

Differential item functioning (DIF) arises when observable indicators of a latent variable are systematically measuring the latent of variable of interest in different ways, or perhaps even measuring different latent variables. One might think of a confounding factor—an orientation, predisposition, or characteristic of respondents—that influences the structural relationship between an observable item and the latent variable it is supposed to measure. This confounding factor effectively produces a “nuisance dimension” (Ackerman 1992), violating the assumed unidimensionality of the latent variable of interest and complicating inferences based on statistical analyses using estimates of this latent variable.Footnote 4 Applying the idea to the present study, DIF would manifest as the observed responses to the individual racial resentment items being affected by something other than latent racial prejudice, such as adherence (or lack thereof) to ideological principles. Should this be the case, the racial resentment scale could be capturing two different latent variables (e.g., racial prejudice and ideology) depending on membership in the confounding group (e.g., conservative vs. liberal), or otherwise distorting the true characteristics of latent racial prejudice. This framework is particularly useful for investigating the principled conservatism thesis because it takes seriously the relationship between latent variables and observed indicators, effectively mimicking in both theoretical and analytical structure the argument of those critical of racial resentment.

There are several ways to investigate DIF, including item response theory (IRT), logistic regression analysis, multiple group confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and multiple indicators multiple causes (MIMIC) models. All of these methods are perfectly legitimate, albeit born of different disciplinary and methodological traditions (Stark et al. 2006). The approach I employ, developed by Crane et al. (2006) and Choi et al. (2011), and originally based on work by Swaminathan and Rogers (1990), combines the IRT and logistic regression approaches. One important advantage this approach has over the more traditional multiple groups CFA methodFootnote 5 is the ability to test for non-uniform DIF—a case where the effect of the confounding factor is nonlinear across levels of the latent variable. This is a particularly important consideration in the case of racial resentment given the focus of previous work on the interactive and nonlinear effects of racial resentment on other attitudes across levels of ideological self-identification (e.g., Feldman and Huddy 2005; Sniderman et al. 2000). Although MIMIC models can be used to test both uniform and non-uniform DIF, the procedures for doing so in a way that does not overestimate Type I error rates are still being fine-tuned (Chun et al. 2016; Wang and Shih 2010).Footnote 6 The iterative procedure employed here, however, helps guard against Type I and Type II errors (Choi et al. 2011). Moreover, neither the MIMIC nor multiple group CFA method—both of which come from the structural equation modeling tradition—are particularly concerned with DIF corrections to estimated latent variables. Scholars working in the IRT tradition, however, are particularly interested in generating scales, or “tests,” that are free of DIF, in addition to standard empirical considerations (i.e., reliability, validity). That said, I do present the results of MIMIC-based DIF analyses—which closely comport in substantive nature with those presented below—in the Supplemental Appendix.

The IRT-regression approach I employ begins with an estimation of an ordinal IRT model on the racial resentment items (the graded response model for ordinal variables, to be preciseFootnote 7). Next, I estimate ordinal logistic regression models of the following form, substituting the dependent variable, “Try Hard,” for each of the remaining three items that compose the racial resentment scale, and “Conservative” for each of the other two operationalizations of adherence to ideological principles:

In total, the analysis involves estimating 36 models for each of the three years under consideration (1992, 2004, 2016): 4 racial resentment items × 3 operationalizations of ideology × 3 models of the above form for estimating DIF. In the model in Eq. (1), the responses to the individual racial resentment items are regressed on only the racial resentment IRT “true score.” The model in Eq. (2) adds a dummy variable indicating whether the respondent is conservative or liberal (adheres to conservative principles or liberal ones). Finally, the model in Eq. (3) adds an interaction term between the estimate of racial resentment and the ideology indicator variable.

Two forms of DIF can be assessed using the estimates from the models above: uniform and non-uniform DIF. Uniform DIF is assessed by comparing -2 log likelihood of the estimated models from Eqs. (1) and (2). This type of DIF suggests that something (ideology) other than the latent variable of interest (racial resentment) systematically affects responses to individual scale items. Non-uniform DIF is assessed by comparing -2 log likelihood of the estimated models from Eqs. (2) and (3). A statistically significant (\(p < 0.05\)) likelihood ratio test indicates that the effect of latent racial resentment on the individual item response is conditional on ideological self-identification or level of adherence to conservative ideological principles. A negative coefficient on the interaction term in equation (3) would provide evidence in support of the principled conservatism thesis—the connection between latent racial resentment and responses to an individual racial resentment item is different between liberals/unprincipled conservatives and principled conservatives. Additional details about the procedure I follow, as well as explication of statistical packages for automatically carrying out the procedure, is outlined by Crane et al. (2006) and Choi et al. (2011).

The results of these analyses appear in Table 1. Considering first data from 1992 and 2004, only two racial resentment items—“deserve” (1992) and “favors” (2004)—revealed statistically significant DIF, both with respect to ideological self-identification. This point is worth underscoring: DIF is observed in only two cases out of a total 48 possibilities to find either uniform or non-uniform DIF across items, operationalizations of ideology, and years. In other words, liberal and conservative self-identifiers, principled liberals and principled conservatives are, on the whole, using the racial resentment items in statistically indistinguishable ways. Said another way, those who are not principled conservatives do not appear to interact with the racial resentment items in a different way than principled conservatives.

The 2016 data reveals more DIF. In this case, I observe statistically significant differential item functioning on a minimum of 2 out of 4 racial resentment items for each operationalization of ideology. Congruent with the 1992 and 2004 data, DIF is most widespread when it comes to ideological self-identification, manifesting in both the uniform and non-uniform variants for the “deserve” and “favors” items, and the uniform sort for the “conditions” item. Non-uniform DIF is observed by adherence to ideological preferences as operationalized by government spending preferences for all but the “conditions” item. Finally, I observe non-uniform DIF for the “conditions” and “favors” items with respect to beliefs about the proper size and scope of government.

No item is immune from DIF across all operationalizations of adherence to ideological principles. This provides some supportive evidence for principled conservatism thesis. Variations in ideological identity and adherence to ideological principles appear to significantly affect observed responses to the individual racial resentment items by conditioning the effect of latent racial prejudice on these item responses, especially in 2016. The most consistently DIF-afflicted items appear to be the “deserve” and “favors” items. Characteristics of these items vary most by ideological self-identification, but in only three total instances when it comes to spending preferences or beliefs about the size and scope of the federal government. Across years, items, and operationalizations of adherence to ideological principle, I find little evidence for the principled conservatism thesis. Rather, ideological identities appear to be the cause of the majority of observed differential item functioning.

The “try hard” and “conditions” items fare best across operationalizations of ideology, exhibiting significant DIF in only three total instances. This is substantively interesting. The “try hard” item is most frequently held up as an example of problematic language by critics of racial resentment because it most cleanly invokes conservative principles of individualism and hard work (e.g., Carmines et al. 2011; Huddy and Feldman 2009; Schuman 2000). Nevertheless, I observe neither non-uniform nor uniform DIF for this item by ideological self-identification or beliefs about the size and scope of government in 2016, nor any DIF whatsoever in 1992 or 2004.

Assessing the Substantive Effect of DIF

The analyses presented above reveal mixed evidence of DIF in the racial resentment items. Even though most DIF is confined to one of three datasets and one of three operationalizations of ideology, results are not sufficiently consistent to make a conclusion regarding the veracity of the principled conservatism thesis. Thus, I provide a final empirical test of whether the observed DIF is sufficiently problematic to alter the explanatory power of the racial resentment scale. I restrict these analyses to the 2016 ANES data because this is where nearly all observed DIF manifests.Footnote 8 The procedure, at its core, is quite simple: correct the racial resentment scale for DIF, and then compare the effects of the DIF-corrected and DIF-afflicted scales on attitudinal outcomes that previous literature has identified. If there is little or no difference in the effects of the DIF-corrected and DIF-afflicted scales across a series of models, then it would logically follow that the magnitude of DIF, where it is even observed, is not sufficiently problematic to affect the operation or predictive characteristics of the racial resentment scale in a meaningful way. In other words, such a scenario would mean that level of adherence to ideological principles or ideological self-identification do not substantively affect responses to the racial resentment items or the operation of the scale.

While there are variations in methods for correcting scales composed of items that exhibit differential item functioning, the heart of most procedures involves estimating separate item parameters for members of DIF-associated groups (in this case, liberals versus conservatives, and those adhere to conservative ideological principles versus those who do not). Take the “deserve” item with respect to ideological self-identifications (see the first and second column, and first row, of Table 1), for example. This item exhibits statistically significant DIF by identification with an ideological group—liberal or conservative. To reduce the effects of DIF associated with this item on the complete racial resentment scale, I first create two new variables: one that takes on the values of the “deserve” item for individuals who identify as a conservative—I will call this deserve_conserv—and one that takes on the values of the “deserve” item for individuals who identify as a liberal, which I will call deserve_liberal. For self-identified liberals, the deserve_conserv variable is coded as missing, and for self-identified conservatives, deserve_liberal is coded as missing. This operation is repeated for all pairs of item/ideology measure pairs.Footnote 9 Finally, the racial resentment IRT model is re-estimated using the dummied versions of the individual indicator items, allowing for discrimination and difficulty parameters—the model parameters that relate items to the latent variable and subsequently help orient individuals along the latent continuum—to vary by ideological self-identification or adherence to ideological principles.Footnote 10 This procedure results in three new estimates of racial resentment: one corrected for DIF related to ideological self-identification, one corrected for DIF related to government spending preferences, and one corrected for DIF related to beliefs about the proper size and scope of government.

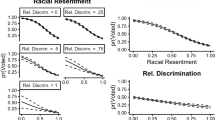

Full parameter estimates from these DIF-corrected IRT models can be found in the Supplemental Appendix. Figure 3 depicts differences in the discrimination (loading) and difficulty (threshold) parameters between ideological groups (e.g., liberal vs. conservative identity, principled vs. non-principled) across the three models estimated, one for each operationalization of ideology. The larger the pairwise discrepancies in item parameters across ideological groups, the larger the potential effect of DIF. With both discrimination and difficulty parameters, the modal difference, per Table 1, is 0. In both cases, a large majority of differences in item parameters is 0.50 or less, hinting that the cumulative effect of DIF on the racial resentment scale is likely small. It is also worth noting that the differences are almost all positive. Since the parameters from the principled conservatives were subtracted from those associated with liberals or the ideologically unprincipled, this means that the items have more discriminatory power (i.e. “load” more strongly) for liberals or the ideologically unprincipled. This also means that the average responses to the items are more “resentful” for (principled) conservatives. This finding is congruent with what the principled conservatism thesis would hold: the more principled appear to be more prejudiced.

To understand the effect of these relatively few observed differences in item parameter estimates on the complete racial resentment scale, I simply generated an estimate of the latent racial resentment variable using the model estimates. Although significant DIF was observed for at least two items with respect to each of the ideology measures in 2016, correction for DIF does not appear to make a substantive difference when it comes to placing individuals along the latent racial resentment continuum. Consider the correlations between the individual scores on the DIF-afflicted racial resentment and the individual scores along the DIF-corrected racial resentment scales that appear in Table 2. The smallest correlation between the original, uncorrected scale and any one of the corrected scales is 0.981. Thus, the effect of ideology on the observed responses to the individual racial resentment items does not appear to be of substantive consequence, despite the statistical significance of the problem.

Finally, I turn to a more robust test of the effect of differential item functioning caused by adherence to ideological principles. Following much of the literature speaking to the debate about the validity of the racial resentment scale, I examine the predictive power of the DIF-corrected and DIF-afflicted scales when it comes to a host of racial issue attitudes (e.g., Kinder and Sanders 1996; Kinder and Mendelberg 2000; Sniderman et al. 2000). I regress attitudes about two explicitly racial political issues—aid to minorities and preferential hiring for blacks—and one recently “racialized” issue (Tesler 2012)—health insurance – on racial resentment and a host of control variables. Each of these dependent variables was coded so that larger numerical values denote more conservative responses. In each model, I control for partisan self-identification, egalitarianism, moral traditionalism, interest in politics, retrospective economic evaluations, education, income, age, gender, and residence in the political South.Footnote 11 In order to provide the most conservative test of the effects of the DIF-corrected and DIF-uncorrected racial resentment scales, I also control for the measures of ideology that are not involved in the correction (Zigerell 2015). For instance, in any model comparing the effect of the uncorrected racial resentment scale with the racial resentment scale corrected for DIF by government spending preferences, I also control for ideological self-identification and beliefs about the proper size and scope of the government. All interval and ordinal level variables, including the the dependent variables, have been rescaled to range from 0 to 1. Thus, the effects of independent variables can be compared within and between models, since all models are identical save for the dependent variable. All controls were included in each model; however, I only present effects of variables of interest—in Figs. 4, 5 and 6—to save space. Estimates for control variables across all 18 models can be found in the Supplemental Appendix.

Each of the figures includes comparisons of the original, uncorrected scale and the scale corrected for DIF induced by the variable appearing in the tan-colored panel header. Circular plotting symbols represent the OLS estimates from models with the uncorrected version of racial resentment, and triangular plotting symbols represent estimates from models with the DIF-corrected scales. The comparison I am most interested in making is between the estimates associated with the corrected and uncorrected racial resentment scales in each panel, and with respect to each dependent variable. Thus, even though I do not observe a statistically significant effect of the racial resentment scale DIF-corrected for self-identifications in the first panel of Fig. 6, that such is the case for the DIF-uncorrected scale as well should be interpreted as a lack of an effect of DIF corrections.Footnote 12 In no case do I observe a statistically significant difference in the effect of the corrected and uncorrected scale, regardless of which operationalization of ideology the DIF was corrected for or what the dependent variable is.

In sum, though I observe a statistically significant effect of ideology on the observed responses to the individual items that compose the racial resentment scale in 2016 (but not 1992 or 2004, for the most part), the substantive effect of the differential item functioning caused by this relationship is simply negligible. After adjusting for DIF, the corrected versions of the racial resentment scale—regardless of the operationalization of ideology used to correct the DIF—remained highly correlated with the original, DIF-afflicted scale. Furthermore, the effects of the uncorrected and corrected racial resentment scales on a host of policy attitudes frequently employed in the literature are statistically and substantively identical. This result reinforces the weak effect that ideological concerns—whether in the form of symbolic self-identification, or adherence to ideological principles—has on the racial resentment items and resultant scale.

Conclusion

It is noteworthy that the racial resentment items do not exhibit differential item functioning by level of adherence to conservative ideological principles significant enough—where present at all—to substantively alter any of the structural relationships between the racial resentment scale and specific issue attitudes. Though ideological self-identifications have long been known to correlate with racial resentment, the reason for such a correlation was in dispute. The analyses presented above suggest that ideological principles have little to do with this correlation, especially when the debate over the racial resentment measurement strategy was in full force (e.g., the 1992 and 2004 ANES analyses).

These findings do not preclude the possibility that explicitly and implicitly racial issue attitudes are not merely indicators of the same latent construct that the racial resentment items tap, as Schuman (2000) has argued. However, the findings do allow for a reasonably confident conclusion that subscribing to the basic tenets of conservatism—in the American context, at least—has little to do with the structural relationship between racial resentment and racial policy attitudes. The remaining question, then, is: what does this say about racial policy views in America? If attitudes about such issues really do occupy a dimension shared with racial resentment rather than other non-racial issues, then it seems that racial policy attitudes are, indeed, strongly related to racial resentment. Why else would attitudes about racial issues be distinct from attitudes about other policy areas, if not for the looming presence and substantive impact of racial prejudice?

Most self-identified conservatives, as Ellis and Stimson (2012) demonstrate, do not hold particularly conservative policy preferences. Furthermore, the correlation between racial resentment and symbolic ideological predispositions is much stronger than the correlations between either measure of adherence to conservative ideological principles and racial resentment. This is especially the case in the pre-2016 data. Such findings reinforce the idea that symbolic ideology is qualitatively different than operational ideology. This puts the literature about the relationship between racial resentment and ideology in a quandary. Symbolic self-identifications with ideological labels seem to be much more strongly related to racial resentment than do measures of adherence to liberal-conservative ideological principles. It is worth emphasizing, too, that the latter measures are inherently more reliable—because they are multiple-item scales designed to reduce measurement error (Ansolabehere et al. 2008)—and valid indicators of ideological principle than self-identifications. Thus, while ideology, in some form, does appear to be related to racial resentment, it is not the form that proponents of the principled conservatism thesis assert.

Instead, symbolic attachments to ideological labels are more strongly related to racial resentment (in terms of raw correlation and magnitude of bias due to DIF). But what could be driving this association, if not adherence to ideological principles? One potential explanation is elite partisan cueing. There exists strong evidence for partisan sorting—the increasing congruence between partisan and ideological identities—among the mass public over time (e.g., Levendusky 2009; Mason 2015). If self-identified conservatives are increasingly identifying as Republicans, they are also likely being exposed to Republican messaging (to which they are more receptive) more frequently. Plenty of scholarship has documented the implicit racial cues communicated in Republican “dog whistles” or “code words” about welfare, inner cities, the poor, etc. (e.g., Gilens 2001; Mendelberg 2001). Perhaps, then, Republican elite cueing is driving the relationship between conservative identity and racial resentment, congruent with the “top-down” model of public opinion formation. This possibility is particularly appealing given the temporal dynamics—little DIF in 1992 and 2004, more in 2016—revealed by the analyses presented above. There should be more DIF in 2016 than previous years when sorting was lower (Levendusky 2009), and the cumulative impact of racial code words was smaller (Enders and Scott 2019). These possibilities should be examined further.

The relationship between ideological identity and racial resentment also calls into question whether racial resentment actually underlies liberal-conservative self-identification, rather than being a product, or psychologically equal source, of public opinion as ideological self-identification. This idea certainly seems reasonable given the strong connection between symbolic ideological attachments and so-called “cultural issues,” of which racial policies are the quintessential example (Ellis and Stimson 2012). Furthermore, many things go into ideological self-identification beyond abstract principles and values, including basic group orientations and perceptions of who liberals and conservatives really are (Conover and Feldman 1981; Malka and Lelkes 2010). The cultural connotations of the actual “liberal” and “conservative” labels may even be an important aspect of self-identification—one that drives the correlation between ideological identity and racial resentment. I encourage researchers to more carefully consider the direction of the causal relationship between racial resentment and ideological self-identifications, and delve deeper into the dimensions of ideological self-identification that are driving the correlation with racial resentment.

Notes

I suppose that one could, alternatively, consider whether responses to questions about ideological self-identifications and policy preferences exhibit differential item functioning by level of racial resentment. However, the survey items assessing those predispositions and attitudes have been more successfully (i.e., less controversially) validated over the course of time, and the question at hand regards the viability of racial resentment as a measure of racial prejudice rather than ideological beliefs, more specifically.

Data and replication files can be found on the Political Behavior Harvard Dataverse page here.

The particular policy areas queried are not consistent across ANES surveys. After removing references to non-domestic policies (e.g., “aid to former Soviet Union countries” and “foreign aid,” more generally) and blacks, specifically (e.g., “assist blacks,” in 1992), there are 8 items in the 2004 and 2016 scales, and 14 in the 1992 scale. Since the spending items focused on welfare and aid to the poor have a racial dimension to them (e.g., Gilens 2001), I replicated all analyses below with a version of the spending scale omitting these items. These analyses revealed even less differential item functioning in the racial resentment items than did the analyses using the complete scale. In other words, the principled conservatism thesis finds even less support when I measure spending preferences in this alternative way.

The structural equation modeling approach that employs multiple group CFA usually refers to DIF as “measurement invariance.” When one conducts a factor analysis, for example, one implicitly assumes that the coefficients relating the individual indicator variables to the latent factors are statistically identical across groups. If this is not the case, the data/model combination violate the principle of measurement invariance, potentially biasing inferences made using analytical results obtained with the model (e.g., predicted factor scores). This is simply a different way—one born of scholars working in the factor analysis and structural equation modeling traditions, specifically—of talking about the same problem.

Note that although the exact procedure for carrying out a DIF analysis in the MIMIC approach is still being investigated, at its core the MIMIC approach is identical to the IRT-logistic regression approach I employ. A one-factor categorical CFA—which is at the heart of the MIMIC approach when ordinal variables are involved—is identical to an ordinal IRT model, assuming a constraint on the variance of the latent variable to identify the model Takane and de Leeuw (1987). In the IRT-logistic regression approach, the latent variable from the IRT model is estimated and then used in the three equations presented below to detect uniform and non-uniform DIF. In the MIMIC approach, the exact same equations are estimated, but they are estimated simultaneously with the measurement model in the fashion of structural equation models with latent variables.

This model takes the following form: \(Pr(Y_{ij} \le k|\theta _i) = \frac{\text {exp}\{\alpha _{j}(\theta _i - b_{jk})\}}{1 + \text {exp}\{\alpha _{j}(\theta _i - b_{jk})\}} \quad \theta _i \sim N(0, 1)\). Estimates from this uncorrected (i.e., DIF-afflicted) racial resentment IRT models for each year are presented in the Supplemental Appendix. The correlations between the estimated latent trait scores from the IRT model and the additive index operationalization of racial resentment range from 0.95 (1992) to 0.99 (2016) across years. This reflects the fact that the discrimination parameters from IRT model—those coefficients which relate the individual items to the latent trait—are nearly identical across items. Regardless of the similarity of the DIF-afflicted latent trait scores at this point in the analysis, the IRT framework will make for easier and more robust corrections to DIF in the next section of the manuscript.

Correcting the single racial resentment item for self-identification-based DIF in 1992 and 2004 does not result in substantive differences in the respective racial resentment scales.

Using multiple category distinctions between “levels” of adherence to ideological principles or altering the (already generous) threshold between principled and unprincipled for the non-symbolic measures of ideology does not alter substantive inferences.

This procedure, like most DIF-correction procedures, assumes that at least one item does not exhibit significant DIF. This is necessary so that the DIF-afflicted items can be “anchored” to the appropriately-functioning item. With each measure of ideology, there is at least one item that does not exhibit significant uniform or non-uniform DIF, providing the opportunity to safely make corrections.

Question wording and variable coding can be found in the Supplemental Appendix.

This finding is at odds with recent work by Tesler (2012) about the spillover racialization of healthcare attitudes. However, I provide rather extensive controls for ideological principles in the models. If I remove the controls for spending preferences and beliefs about the size and scope of government, effects of both the DIF-corrected and -uncorrected racial resentment scale become statistically significant. Again, though, I wish to emphasize that the test of my theory rests on an examination of differences in the estimates associated with the corrected and uncorrected scale, not the statistical significance of any given estimate.

References

Ackerman, T. A. (1992). A didactic explanation of item bias, item impact, and item validity from a multidimensional perspective. Journal of Educational Measurement, 29(1), 67–91.

Ansolabehere, S., Rodden, J., & Snyder, J. M. (2008). The strength of issues: Using multiple measures to gauge preference stability, ideological constraint, and issue voting. American Political Science Review, 102(2), 215–232.

Carmines, E. G., Sniderman, P. M., & Easter, B. C. (2011). On the meaning, measurement, and implications of racial resentment. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 634(1), 98–116.

Chen, P. G., & Goren, P. N. (2016). Operational ideology and party identification: A dynamic model of individual-level change in partisan and ideological predispositions. Political Research Quarterly, 69(4), 703–715.

Choi, S. W., Gibbons, L. E., & Crane, P. K. (2011). lordif: An R package for detecting differential item functioning using iterative hybrid ordinal logistic regression/item response theory and Monte Carlo simulations. Journal of Statistical Software, 38(8), 1–30.

Chun, S., Stark, S., Kim, E. S., & Chernyshenko, O. S. (2016). MIMIC methods for detecting DIF among multiple groups: Exploring a new sequential-free baseline procedure. Applied Psychological Measurement, 40(7), 486–499.

Claassen, C., Tucker, P., & Smith, S. S. (2015). Ideological labels in America. Political Behavior, 37(2), 253–278.

Conover, P. J., & Feldman, S. (1981). The origins and meaning of liberal/conservative self-identifications. American Journal of Political Science, 25, 617–645.

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. E. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and discontent. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Crane, P. K., Gibbons, L. E., Jolley, L., & van Belle, G. (2006). Differential item functioning analysis with ordinal logistic regression techniques. Medical Care, 44(11), S115–S123.

DeSante, C. D. (2013). Working twice as hard to get half as far: Race, work ethic, and America’s deserving poor. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 342–356.

Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E., & Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American Political Science Review, 107, 57–79.

Ellis, C., & Stimson, J. (2012). Ideology in America. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Enders, A. M., & Scott, J. S. (2019). The increasing racialization of American electoral politics, 1988–2016. American Politics Research, 47(2), 275–303.

Feldman, S., & Huddy, L. (2005). Racial resentment and white opposition to race-conscious programs: Principles or prejudice? American Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 168–183.

Free, L. A., & Cantril, H. (1967). The political beliefs of Americans. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Gilens, M. (1999). Why Americans hate welfare: Race, media, and the politics of antipoverty policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gilens, M. (2001). Political ignorance and collective policy preferences. American Political Science Review, 95(2), 379–396.

Hare, C., Armstrong, D. A., Bakker, R., Carroll, R., & Poole, K. T. (2015). Using Bayesian Aldrich–McKelvey scaling to study citizens’ ideological preferences and perceptions. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 759–774.

Henry, P. J., & Sears, D. O. (2002). The symbolic racism 2000 scale. Political Psychology, 23, 253–283.

Hetherington, M. J., & Weiler, J. (2009). Authoritarianism and polarization in American politics. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Huddy, L., & Feldman, S. (2009). The structure of racial attitudes among whites. Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 423–447.

Jacoby, W. G. (2000). Issue framing and public opinion on government spending. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 750–767.

Kam, C. D., & Burge, C. D. (2018). Uncovering reactions to the racial resentment scale across the racial divide. Journal of Politics, 80(1), 314–320.

Kinder, D. R., & Sanders, L. M. (1996). Divided by color: Racial politics and democratic ideals. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Kalmoe, N. P. (2017). Neither liberal nor conservative: Ideological innocence in the American public. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Mendelberg, T. (2000). Individualism reconsidered: Principles and prejudice in contemporary American opinion. In D. R. Kinder & T. Mendelberg (Eds.), Racialized politics: The debate about racism in America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Knuckey, J., & Kim, M. (2015). Racial resentment, old-fashioned racism, and the vote choice of southern and nonsouthern whites in the 2012 US presidential election. Social Science Quarterly, 96(4), 905–922.

Levendusky, M. S. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberals became democrats and conservatives became republicans. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. S. (2010). Clearer cues, more consistent voters: A benefit of elite polarization. Political Behavior, 32, 111–131.

Malka, A., & Lelkes, Y. (2010). More than ideology: Conservative-liberal identity and receptivity to political cues. Social Justice Research, 23, 156–188.

Mason, L. (2015). I disrespectfully agree’: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59, 128–145.

McCarty, N., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2006). Polarized America: The dance of ideology and unequal riches. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mendelberg, T. (2001). The race card: Campaign strategy, implicit messages, and the norm of equality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Neblo, M. A. (2009a). Meaning and measurement: Reorienting the race politics debate. Political Research Quarterly, 62(3), 474–484.

Neblo, M. A. (2009b). Three-fifths a racist: A typology for analyzing public opinion about race. Political Behavior, 31(1), 31–51.

Pérez, E. O., & Hetherington, M. J. (2014). Authoritarianism in black and white: Testing the cross-racial validity of the child rearing scale. Political Analysis, 22, 398–412.

Pietryka, M. T., & MacIntosh, R. C. (2013). An analysis of ANES items and their use in the construction of political knowledge scales. Political Analysis, 21, 407–429.

Rabinowitz, J. L., Sears, D. O., Sidanius, J., & Krosnick, J. A. (2009). Why do White Americans oppose race-targeted policies? Clarifying the impact of symbolic racism. Political Psychology, 30(5), 805–828.

Schuman, H. (2000). The perils of correlation, the lure of labels, and the beauty of negative results. In D. O. Sears, J. Sidanius, & L. Bobo (Eds.), Racialized politics: The debate about racism in America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sears, D. O., Van Laar, C., Carrillo, M., & Kosterman, R. (1997). Is it really racism?: The origins of White Americans’ opposition to race-targeted policies. Public Opinion Quarterly, 61(1), 16–53.

Sears, D. O., & Henry, P. J. (2005). Over thirty years later: A contemporary look at symbolic racism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 37, 95–150.

Sides, J., Tesler, M., & Vavreck, L. (2016). The electoral landscape of 2016. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667(1), 50–71.

Sniderman, P. M., & Carmines, E. G. (1997). Reaching beyond race. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sniderman, P. M., Crosby, G. C., & Howell, W. G. (2000). The politics of race. In D. O. Sears, J. Sidanius, & L. Bobo (Eds.), Racialized politics: The debate about racism in American. Princeton, NJ: University of Chicago Press.

Sniderman, P. M., & Tetlock, P. E. (1986). Symbolic racism: Problems of motive attribution in political analysis. Journal of Social Issues, 42(2), 129–150.

Sniderman, P. M., & Piazza, T. (1993). The scar of race. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Stark, S., Chernyshenko, O., & Drasgow, F. (2006). Detecting differential item functioning with confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory: Toward a unified strategy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1292–1306.

Swaminathan, H., & Jane Rogers, H. (1990). Detecting differential item functioning using logistic regression procedures. Journal of Educational Measurement, 27(4), 361–370.

Takane, Y., & de Leeuw, J. (1987). On the relationship between item response theory and factor analysis of discretized variables. Psychometrika, 52(3), 393–408.

Tarman, C., & Sears, D. O. (2005). The conceptualization and measurement of symbolic racism. Journal of Politics, 67(3), 731–761.

Tesler, M. (2012). The spillover of racialization into health care: How president Obama polarized public opinion by racial attitudes and race. American Journal of Political Science, 56(3), 690–704.

Tesler, Michael. (2013). The return of old fashioned racism to White Americans’ partisan preferences in the early Obama era. Journal of Politics, 75(1), 110–123.

Valentino, N. A., & Sears, D. O. (2005). Old times are not forgotten: Race and partisan realignment in the contemporary south. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 672–688.

Wallsten, K., Nteta, T. M., McCarthy, L. A., & Tarsi, M. R. (2017). Prejudice or principled conservatism? Racial resentment and white opinion toward paying college athletes. Political Research Quarterly, 70(1), 209–222.

Wang, W.-C., & Shih, C.-L. (2010). MIMIC methods for assessing differential item functioning in polytomous items. Applied Psychological Measurement, 34(3), 166–180.

Wilson, D. C., & Davis, D. W. (2011). Reexamining racial resentment: Conceptualization and content. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 634(1), 117–133.

Zigerell, L. J. (2015). Distinguishing racism from ideology: A methodological inquiry. Political Research Quarterly, 68(3), 521–536.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Miles Armaly, Jamil Scott, Paul Sniderman, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments, critiques, and suggestions. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Enders, A.M. A Matter of Principle? On the Relationship Between Racial Resentment and Ideology. Polit Behav 43, 561–584 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09561-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09561-w