Abstract

Some commentators claim that white Americans put prejudice behind them when evaluating presidential candidates in 2008. Previous research examining whether white racism hurts black candidates has yielded mixed results. Fortunately, the presidential candidacy of Barack Obama provides an opportunity to examine more rigorously whether prejudice disadvantages black candidates. I also make use of an innovation in the measurement of racial stereotypes in the 2008 American National Election Studies survey, which yields higher levels of reporting of racial stereotypes among white respondents. I find that negative stereotypes about blacks significantly eroded white support for Barack Obama. Further, racial stereotypes do not predict support for previous Democratic presidential candidates or current prominent Democrats, indicating that white voters punished Obama for his race rather than his party affiliation. Finally, prejudice had a particularly large impact on the voting decisions of Independents and a substantial impact on Democrats but very little influence on Republicans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Political scientist Abigail Thernstrom argues that Barack Obama’s election to the office of the presidency “will allow black parents to tell their children, it really is true: the color of your skin will not matter” (2008). Thernstrom’s interpretation is consistent with many accounts of the election in the popular media, which argue that the color of Barack Obama’s skin did not matter to white voters (Curry 2008; Schneider 2008; Steele 2008).

To be sure, pundits disagree about the reasons that Obama escaped the ill effects of prejudice; some argue that Obama “seduced whites,” capitalizing on their longing “to escape the stigma of racism” (Steele 2008), while others hold that Obama attracted white voters by presenting himself as centrist and “post-racial” (Thernstrom 2008). Still others claim that the poor state of the economy (Curry 2008) or other crises (Gibbs 2008) caused Americans to realize that they could not afford to evaluate the candidates on the basis of race. Regardless of these differences, many agree that white Americans put racial prejudice behind them when voting in the presidential election.

However, it is possible that Obama won the presidential election without neutralizing the effect of prejudice among whites. As Ansolabehere and Stewart (2009) report, exit polls show that Obama did not win the popular vote among whites.Footnote 1 Rather, strong support among blacks (95%) and Latinos (67%) propelled Obama to victory, despite the fact that he only obtained the support of a minority of whites (43%).Footnote 2

An analysis of the impact of prejudice on Obama’s bid for the presidency has the potential to address the larger question of whether white voters discriminate against black candidates. Previous work on this question has yielded contradictory findings, but my approach overcomes some of the limitations of that research. In particular, data from the American National Election Studies (ANES) time series surveys allow me to analyze a nationally representative sample of white Americans. I also exploit a methodological innovation in the 2008 ANES, designed to mitigate social desirability problems, that leads to greater reporting of negative racial stereotypes among white Americans. I find that racial prejudice significantly eroded white support for Barack Obama. Further, since racial prejudice may exert a powerful force in electoral politics even when both candidates are white, I compare its role in white voters’ evaluations of Obama to its role in white voters’ evaluations of both past Democratic presidential candidates and current prominent Democrats. These comparisons indicate that prejudice hurt Obama because of his race rather than his party or policy platform. Finally, I dig deeper than most previous research on the question of white racial prejudice and black candidates by examining how the effect of prejudice varies by partisanship.

Has White Prejudice Hurt Black Candidates?

Scholars attempting to determine whether white voters discriminate against black candidates have used a variety of approaches, including experimental designs, surveys, and ecological inference techniques. The results have been mixed. Some studies find that white voters discriminate against black candidates (Moskowitz and Stroh 1994; Reeves 1997; Terkildsen 1993), but others find that white voters do not (Citrin et al. 1990; Highton 2004; Sigelman et al. 1995; Voss and Lublin 2001).

The limitations of previous research designs may be driving the contradictory findings. Some studies ask respondents to evaluate fictitious candidates (Moskowitz and Stroh 1994; Reeves 1997; Sigelman et al. 1995; Terkildsen 1993), a strategy that allows tight control over candidate characteristics but may lead to results that do not generalize to the real world. Others do not measure racial attitudes (Highton 2004; Voss and Lublin 2001), making it impossible to tie prejudice directly to vote choice. Those studies that do measure racial attitudes often ask respondents to report those attitudes to an interviewer (Citrin et al. 1990; Highton 2004; Terkildsen 1993), despite the fact that racial prejudice is often underreported due to social desirability pressures (Huddy and Feldman 2009). Finally, almost no studies analyze a national sample of white Americans (but see Highton 2004).

The historic presidential candidacy of Barack Obama provides an opportunity to build on previous work. To do so, I use the 2008 American National Election Studies (ANES) time series survey. The ANES measures vote choice and racial attitudes among a nationally representative sample of adults. Particularly useful for my purposes is a methodological innovation introduced in 2008. Survey respondents were asked to enter their answers to racial stereotype questions directly into a computer, out of sight of the interviewer, in an attempt to reduce social desirability pressures. The present study overcomes many of the limitations of previous research by analyzing the vote choices of a nationally representative sample of white Americans who evaluated real-life candidates and making use of a self-administered measure of racial stereotypes.

Measuring Racial Prejudice

Why focus on stereotypes rather than some other measure of racial prejudice? After all, many social scientists argue that it has become socially unacceptable in most circles to express negative generalizations about racial groups. Consequently, explicit measures will result in an underestimate of contemporary racial prejudice. Such scholars often focus instead on symbolic racism (Sears and Kinder 1971; Sears 1988), also called racial resentment (Kinder and Sanders 1996) or modern racism (McConahay 1983). Defined as the conjunction of anti-black affect and traditional values related to the Protestant ethic, this form of racism is expressed not in the belief that blacks are innately inferior but in resentment toward blacks based on the perception that they get special, undeserved treatment from government (Bobo et al. 1997; Henry and Sears 2002; McConahay and Hough 1976; Sears et al. 2000). Other scholars argue that even this more subtle measure does not capture the extent of racism, since there is evidence that racism operates at an unconscious level through automatic psychological processes (Devine 1989; Baron and Banaji 2006). Accordingly, psychologists have developed measures of “implicit” racism (Greenwald et al. 1998; Payne et al. 2005).

However, symbolic racism and implicit racism theories have faced numerous criticisms. Some scholars have argued that measures of symbolic racism are confounded with conservative ideology (Feldman and Huddy 2005; Sniderman and Carmines 1997; Sniderman and Tetlock 1986), and others have taken issue with implicit racism research on a number of grounds, ranging from the argument that conscious intent is required for prejudice to exist (Arkes and Tetlock 2004) to concerns about variability and stability in the IAT, the most common measure of implicit racism (Blanton and Jaccard 2008). One virtue of using racial stereotypes as the measure of prejudice in this study, therefore, is that social scientists who disagree about the nature of contemporary racial prejudice may still agree that negative stereotypes constitute a form of prejudice.Footnote 3 However, using negative stereotypes runs the risk of underestimating the impact of racial prejudice, given that measures of symbolic racism are more strongly associated with opposition to racial policies than are more explicit measures (Bobo 2000; Sniderman and Piazza 1993). This study’s estimate of the effect of racial prejudice in the 2008 election may therefore be biased toward zero.

An additional benefit of using an explicit measure such as negative stereotypes is its focus on an understudied aspect of contemporary racism. As a result of increased attention to more subtle forms of racism, some have argued that the role of explicit prejudice in American politics “has been prematurely dismissed” (Huddy and Feldman 2009). Indeed, although explicit prejudice has declined over the past several decades, substantial proportions of white Americans still hold negative stereotypes about blacks (Peffley and Shields 1996; Sniderman and Piazza 1993). Furthermore, recent studies have found that explicit prejudice is linked with opposition to black candidates, housing integration policies, and government assistance to blacks, as well as support for punitive criminal justice policies and miscegenation laws (Feldman et al. 2009; Kinder and McConnaughy 2006; Hurwitz and Peffley 2005). In short, although researchers more commonly focus on symbolic racism or implicit prejudice, we have reason to believe that explicit prejudice is still a powerful force in American politics.

A “Post-Racial” Candidate?

Although previous work has shown that anti-black stereotypes are prevalent and strongly associated with public opinion about a wide range of policies, this does not necessarily mean that white voters will apply their racial stereotypes to a given black candidate. Rather, the candidate could be viewed as an exception to the rule. Kinder and McConnaughy 2006 find, for example, that negative stereotypes predict white opposition to former presidential candidate Jesse Jackson but not Colin Powell. Noting that Colin Powell differs from the prevailing image of blacks in many ways, such as his light skin, his Jamaican heritage, his membership in the Republican Party, and his status as a victorious military general, Kinder and McConnaughy suggest that Powell is immune to racial stereotyping “because he deviates so markedly from the prototype.” Other research also indicates that stereotypes are less likely to influence evaluations for individuals who violate stereotypic expectations (Golebiowska 1996). In fact, under some circumstances those who violate the stereotype in positive ways might be rewarded.

If deviation from a stereotype is a sufficient condition to avoid the consequences of prejudice, Barack Obama may be well-positioned. Obama is light-skinned, his mother is white, and his father is from Kenya. Moreover, during his presidential campaign Obama seldom referred to himself as black and indeed rarely mentioned race at all. He frequently deployed white surrogates to vouch for him to white audiences, and his management team consisted primarily of white veteran Democratic Party insiders. At several points, media pundits actually debated whether Obama was “black enough” for black voters to support him (Fraser 2009).

On the other hand, Obama’s efforts may have failed to neutralize the prejudice of a substantial proportion of whites. Moskowitz and Stroh (1994) found that switching the race of a hypothetical candidate from white to black caused white respondents to attribute to the candidate both unfavorable personality traits and policy positions with which the respondent disagreed, suggesting that Obama’s attempts to portray himself as “post-racial” may have faced an uphill battle. One study suggests that the information-rich environment of a presidential election might make voters more likely to rely on stereotypes to save themselves the cognitive effort of making a comprehensive judgment (Riggle et al. 1992), although other work suggests that stereotypes might have more of an impact in elections in which little information is available (Banducci et al. 2008).

In sum, it is not clear from previous research whether we should expect to find that white voters applied stereotypes about blacks as a group to Obama as an individual. However, given the extent to which Obama may deviate from whites’ prevailing images of blacks, if I still find that prejudice led to a significant loss of support from white voters, it will be hard to imagine that many other black candidates will escape its effects.

Method and Results

To determine whether explicit prejudice influenced white voters in the 2008 election, I use survey data from the May 2009 release of the American National Election Studies (ANES) 2008 time series survey. The response rate of the ANES is high, and the interviews are conducted face-to-face in order to produce high-quality data. Further, the core time series element of the ANES, in which identical questions are asked over the course of many presidential elections, makes it possible to analyze past ANES surveys to compare the effect of prejudice in 2008 to its effect (if any) in previous elections.

I examine the attitudes and vote choice of 1,110 non-Hispanic white respondentsFootnote 4 interviewed through the 2008 ANES. Consistent with other ANES studies conducted during years of presidential elections, interviews were conducted in two waves. The pre-election wave was conducted during the two months preceding the November election, and the post-election wave was conducted during the two months following the election. Among non-Hispanic whites, only 95 of the 1,110 (8.6%) interviewed in the pre-election wave dropped out before the post election wave.

Measuring Racial Stereotypes

There are two racial stereotype questions on the ANES. The first asks the respondent to rate the extent to which blacks are lazy rather than hardworking on a seven-point scale.Footnote 5 The second question asks the respondent to rate the extent to which blacks are unintelligent rather than intelligent on an identical scale. Respondents are also asked to evaluate whitesFootnote 6 along these two dimensions, and the order in which the racial groups are presented to the respondent is randomized.

I construct a difference measure for both the “lazy” question and the “unintelligent” question by subtracting the score the respondent gave blacks from the score for whites. I do so in order to account for respondent characteristics. That is, if a respondent codes blacks as a “5” on a 1 to 7 scale from hardworking to lazy, this coding may be a reflection of her pessimistic view of people in general—as will be evident if she codes whites as a “5” as well. The difference measure therefore allows me to examine how a given respondent views blacks relative to whites, following McCauley et al. (1980) and Kinder and Mendelberg (1995).Footnote 7

The 2008 ANES contains a useful methodological innovation. The racial stereotype questions described above were administered in both the pre- and post-election waves, and the form of the questions was identical across waves in all respects except one. In the pre-election wave, the questions were administered by Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing (ACASI). That is, although the rest of the interview was conducted in a face-to-face context, for questions about stereotypes (and other sensitive subjects such as religious beliefs and sexual orientation), respondents entered their responses directly into the computer, out of the view of the interviewer. ACASI has been shown to reduce social desirability bias in a number of settings (Ghanem et al. 2005; Villarroel et al. 2006). Since the same respondents (minus attritionFootnote 8) answered the questions through ACASI in the pre-election wave and then reported answers to the exact same questions to the interviewer in the post-election wave, I can assess whether social desirability pressures decreased reporting of racial prejudice. If so, I can conclude that the ACASI measure is better suited than previous measures to capture the effects of prejudice in the 2008 election. I compare the two difference measures in Fig. 1a, b.

Figure 1a, b show that racial stereotypes remain alive and well among substantial portions of the white public. Regardless of measure used, at least 45% of the nationally representative sample of white respondents rate blacks as lazier than they rate whites, and at least 39% rate blacks as less intelligent than they rate whites. Additionally, given that social desirability bias has been shown to lead to the underreporting of racial prejudice and of opposition to racial policies and black candidates (Gilens et al. 1998; Kuklinski et al. 1997), we might expect that the ACASI measure will reveal greater levels of prejudice than could be detected using the interviewer measure. The results presented in Fig. 1a, b are in line with this expectation. The percentage of white respondents who rate blacks as lazier than they rate whites is 50% for the ACASI measure compared with 45% for the interviewer measure, a difference of 5% points. Further, the percentage of white respondents who rate blacks as less intelligent than they rate whites is 44% for the ACASI measure compared with 39% for the interviewer measure, also a difference of 5% points. Both differences are statistically significant at the p < .02 level (one-tailed). Negative stereotypes about blacks are more prevalent than is suggested by measures failing to account for social desirability.

To be sure, an alternative interpretation exists for the drop in negative stereotypes between the self-administered and interviewer measures. That is, since the self-administered measure was implemented in the pre-election wave, and the interviewer measure was used in the post-election wave, the election of Obama, which occurred between the two waves, might have caused a decrease in explicit prejudice. However, such an interpretation is inconsistent with other evidence. First, I compare levels of other racial attitudes between ANES surveys in 2000 and 2004 to levels of these same attitudes measured in the 2008 ANES wave after Obama’s election. For all of the five measures I analyze, the feeling thermometer for blacks and each of four questions that comprise the racial resentment index (Kinder and Sanders 1996), I find no change in racial attitudes between the years preceding Obama’s election and the two months following his election. Obama’s election therefore does not appear to have changed racial attitudes among whites, at least in the short term. Second, I regress the interviewer measure of racial stereotypes on race of interviewer, and find that those white respondents with a non-white interviewer scored 3% points lower on the stereotype index than white respondents with a white interviewer.Footnote 9 This effect is statistically significant at the p < .01 level (one-tailed). Social desirability pressures appear to have depressed reporting of racial prejudice when respondents interacted with an interviewer.

Since the ACASI measure mitigates social desirability problems, I use this measure in most of the analyses of the 2008 election that follow. In cases where I compare 2008 to previous years, however, I use the interviewer measure to facilitate an apples-to-apples comparison, since the ACASI measure was not used before 2008.

Comparing the Effect of Prejudice Across Presidential Elections

Recall that the primary goal of this project is to establish whether white voters punished Barack Obama for his race. Given that the Democratic Party routinely obtains the support of a vast majority of blacks and pursues a policy platform that is more liberal on racial issues, we might expect that prejudice affects vote choice even if both candidates are white. How, then, can we assess whether prejudice decreased support for Obama as a result of his race rather than his party or policy platform? The ideal comparison would be between the support Obama received from whites and the support he would have received had he been white. As an approximation to such a comparison, I assess the effect of prejudice in 2008, and compare that to the effect of prejudice in past elections. Previous white Democratic presidential candidates stand in for a counterfactual Barack Obama. I conduct this analysis using ANES time series data from previous years.Footnote 10

I conduct a series of multivariate logistic regression analysesFootnote 11 of presidential elections from 2008 dating back to 1992, the first year in which stereotype questions were included in the ANES. The dependent variable, vote choice, is coded 1 if the respondent reported voting for the Democratic candidate in that year and 0 if the respondent voted for any other candidate. The independent variable of interest is an index consisting of the summation of the difference measure for the “lazy” question and the “unintelligent” question, standardized from 0 to 1. A score of 1 on the index indicates that the respondent rated blacks as both lazy and unintelligent (scores of 7 on each seven-point scale) and rated whites as both hardworking and intelligent (scores of 1 on each scale), while a score of 0 on the index indicates the inverse. I use an index for a few reasons: (1) the variables are conceptually related as measurements of common negative stereotypes about blacks (Devine 1989), (2) the two stereotype questions are highly correlated,Footnote 12 and (3) for ease of exposition. Since the index is the independent variable of interest, it is important to note that breaking the index into its components reveals that each stereotype question makes an independent contribution to the results that follow.Footnote 13

The model for all years from 1992 to 2008 includes several categories of controls. All control variables are included because we have reason to believe they might be both correlated with prejudice and associated with vote choice for reasons other than prejudice: (1) Demographics: party identification,Footnote 14 age, education, gender, region, income, employment status, and marital status; (2) Views of the current state of affairs in the country: evaluations of the economy over the past year and presidential approval; (3) Values: egalitarianism, big government, and moral traditionalism; (4) Policy Attitudes: aid to the poor, welfare, and defense spending; and (5) Affect toward social groups: “big business” and “gay men and lesbians.” I compare the coefficients on the stereotype index for presidential elections from 1992 to 2008 in Fig. 2. The full set of coefficients for all variables in all years is presented in the first five (numerical) columns of Table 1.

The effect of prejudice on vote choice, by election year. Notes: Separate logistic regressions for each year. The dependent variables are vote choice for the Democratic candidate in a given year. Full results reported in Table 1

Figure 2 presents striking results. For those elections with no black candidate, dating from 1992 to 2004, the coefficient on the stereotype index is statistically equivalent to zero.Footnote 15 However, in the 2008 election—the only one with a black candidate—the coefficient on the stereotype index is negative and statistically significant. Further, it is of substantial magnitude, even larger than the coefficient on party identification. Barack Obama, unlike his past Democratic counterparts, was disadvantaged by racial prejudice.

A Superior Measure of Prejudice

I now turn to the ACASI (self-administered) measure of racial stereotypes, which mitigates some of the social desirability concerns, as was shown in Fig. 1. Recall that I only departed from this measure in the previous analysis to facilitate a comparison of the effects of prejudice in elections from 1992 to 2008. In this section I analyze a model identical to those used previously except that the independent variable of interest is the ACASI measure of stereotypes rather than the interviewer measure. Results from this model are presented in the last column of Table 1.

The ACASI measure of stereotypes also reveals a strong relationship between prejudice and vote choice. The coefficient on the ACASI measure is marginally (about 6%) smaller than the coefficient on the interviewer measure, but the decrease in the coefficient’s standard error is substantial (about 24%). Both measures, in sum, indicate that racial prejudice depressed white voting for Obama.Footnote 16

To illustrate the impact of prejudice on the 2008 election I present Fig. 3, a predicted probability plot based on the model in the last column of Table 1. The figure shows that those whites who expressed no prejudice against blacks, represented by a score of 0.5 on the stereotype index, have a predicted probability of 43% of voting for Obama. Since just over half the sample of whites scores greater than 0.5 but less than or equal to 0.75 on the stereotype index, let us consider the effects of movement between those two points. Such movement is associated with a 21% point decrease in the predicted probability of voting for Obama, from 43 to 22%.Footnote 17,Footnote 18, Footnote 19 Further, separate regressions by region (not shown) indicate that the magnitude of the effect of prejudice was similar inside and outside the political South. Racial prejudice significantly eroded the white vote for Obama throughout the nation.

The predicted probability of voting for Obama, by prejudice. Notes: Predicted probabilities generated from the model in the last column of Table 1. Explanatory variables are set to the mean with the exception of indicator variables, which are set to the mode. Confidence intervals generated using Clarify

But how can we be sure that analyses using the ACASI measure capture prejudice’s influence on vote choice as a result of Obama’s race rather than his party? The ACASI measure was only incorporated into the ANES in 2008, precluding a comparison to white Democratic presidential candidates in previous years. However, the ANES does ask respondents to report their affect toward both Barack Obama and prominent white Democrats through a series of feeling thermometers, in which respondents rate how warm or cold they feel toward a political figure on a 0 to 100 scale.

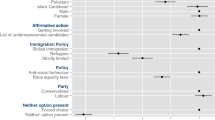

In order to compare the effect of prejudice toward evaluations of Barack Obama to its effect on evaluations of other prominent white Democrats in 2008, I conduct a series of ordinary least squares regression analyses, using the same control variables as in previous models. The dependent variables are feeling thermometer scores, ranging from 0 to 100, for Joseph Biden, Hillary Clinton, Democrats in general, and Barack Obama. If Obama was punished by voters for his race rather than his party, the coefficient on the stereotype index should be negative, while the coefficients on the stereotype index for the other Democrats should be statistically indistinguishable from zero. Figure 4 presents the coefficients, including 95% confidence intervals. The full set of results is presented in Table 2 in the Appendix.

The effect of prejudice on affect toward 2008 Democrats. Notes: Separate ordinary least squares regressions. The dependent variables are feeling thermometer scores, coded from 0 to 100. Full results reported in Table 2 in the Appendix

As Fig. 4 shows, prejudice is associated with affect toward Barack Obama and Barack Obama alone. Prejudiced white Americans were no less likely than the unprejudiced to give high ratings to Joseph Biden, Hillary Clinton, or Democrats in general.Footnote 20 Indeed, for the feeling thermometers for Biden and Clinton, the coefficients on the stereotype index are actually slightly positive, while the coefficient on the stereotype index for Democrats in general is barely below zero. For Obama, however, the coefficient on the stereotype is negative and statistically distinct from zero. Further, the effect of prejudice is large: movement from the lowest score to the highest on the stereotype index is associated with a decrease in over 31 points on the feeling thermometer.

Prejudice Matters—but for Whom?

The preceding analyses established that racial prejudice played a substantial role in the 2008 election on average. Such an approach is in keeping with much of the political science literature, which focuses on the prevalence and impact of racial attitudes for whites as a group without delving into how racial attitudes might function differently in subpopulations of whites (but see Kinder and Mendelberg 1995).

One exception is the work of Sniderman and Carmines (1997). The authors argue that the impact of white racial attitudes on public opinion about policies designed to alleviate racial inequality is, perhaps counterintuitively, greater for Democrats than Republicans. They illustrate this reasoning through an example. White Republicans should oppose a job training program for blacks regardless of whether their feelings toward blacks are negative or positive. This is because Republicans are more likely to believe, on a principled basis, that government programs cause more problems than they solve—so even those Republicans who have positive feelings toward blacks will oppose the job training program on the grounds that it may actually worsen conditions for blacks. Democrats, on the other hand, will support the program if they have positive feelings toward blacks but will be less likely to do so if they have negative feelings toward blacks, since their belief that government should help the disadvantaged will conflict with their prejudice. Indeed, Sniderman and Carmines find that while white Republican support for a variety of policies meant to decrease racial inequality is low regardless of prejudice, support for these policies among Democrats declines markedly as prejudice increases.Footnote 21

However, there is also reason to suspect that Sniderman and Carmines’ findings might not apply to the 2008 election. First, their findings are based on surveys that were conducted in the early 1990s. Recent scholarship suggests that racial attitudes drove partisan sorting after that time (Valentino and Sears 2005). It could be, therefore, that racial prejudice no longer leads to a substantial cleavage among Democrats, since those Democrats who were conflicted as a result of racial prejudice have moved to the Republican Party.Footnote 22 Further, Sniderman and Carmines analyze public opinion about racial policies rather than evaluations of black candidates, although it is plausible that their logic could be extended to vote choice.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of racial prejudice among Democrats, Republicans, and Independents (including leaners). While the distribution is nearly identical for Democrats and Independents, Republicans report higher levels of prejudice. As can be seen in Fig. 5, a smaller proportion of Republicans than Democrats and Independents score at exactly 0.5 on the index, which represents the prejudice-neutral midpoint. A larger proportion of Republicans, 67%, score greater than this midpoint, indicating some level of racial prejudice, compared to 55% of Independents and 54% of Democrats. The difference between Republicans and each of the other two groups is significant at the p < .001 level (two-tailed). Still, the distribution is approximately normal for all three partisan groups, suggesting that any partisan differences in the effects of prejudice will probably not be the result of limited variance within some partisan group.

Extending the logic of Sniderman and Carmines, I expect that the effect of racial attitudes on vote choice in the 2008 presidential election will be greater among white Democrats than among white Republicans. Both low- and high-prejudiced Republicans will oppose Barack Obama, because they oppose his policies, while high-prejudiced Democrats will face the cross-cutting pressures of Obama’s platform and his race. Figure 6 shows the results of separate logistic regressions for Democrats, Independents, and Republicans, using models that are otherwise identical to the model in the last column of Table 1.Footnote 23

The effect of prejudice on the probability of voting for Obama, by party. Notes: Separate regressions for each party. Model based on the last column in Table 1. Explanatory variables are set to the mean with the exception of indicator variables, which are set to the mode

Consistent with my expectations, prejudice is associated with vote choice for Democrats, but not Republicans, in the 2008 presidential election. To give a sense of the magnitude of the effect, I again trace the stereotype index from the prejudice-neutral midpoint of 0.5 to 0.75, since about half the white sample lies between these two points. The predicted probability of voting for Obama among Democrats drops 10% points from 89 to 79%. Among Independents, the predicted probability drops from 54 to 32%. This decline of 22% points is over twice as great as the decline among Democrats. Finally, among Republicans the decline is miniscule, from 3 to 1%, although the slope of the line is statistically significant. A floor effect appears to be driving this result. Even among those Republicans who do not express racial prejudice, support for Obama is so low that there is no room for it to decline further.

These findings build on previous research in a few ways. First, among white Americans, prejudice continues to present more of a cleavage for Democrats than Republicans, despite continued partisan sorting since the early 1990s. However, the effect of racial prejudice may be greatest among Independents. Second, the disproportionate influence of prejudice among white Democrats as compared to Republicans is not limited to opinion about policies designed to mitigate racial inequality but also extends to vote choice for African-American candidates of the Democratic Party.

Conclusion

I conduct a test of racial discrimination among white voters in the 2008 election, using a measure of prejudice that many social scientists believe does not capture the full extent of racism, explicit negative stereotypes about blacks. Further, in order to ensure that any relationship between prejudice and vote choice resulted from Obama’s race rather than from his affiliation with the Democratic Party, I compare the effect of prejudice on vote choice for Barack Obama to its effect on vote choice for previous white Democratic presidential candidates and find that prejudice hurt Obama but not previous Democrats. I also find that the self-administered stereotype measure, which yields higher reporting of negative stereotypes about blacks, is associated with vote choice for Obama but not with affect toward prominent white Democrats. In sum, racial stereotypes were not associated with either votes for or affect toward any prominent Democrats, past or present, save one: Barack Obama.

This finding contributes to a debate in political science over whether white voters discriminate against black candidates in the voting booth. Previous work yielded mixed results but suffered from a number of limitations, relying on evaluations of hypothetical candidates, using samples from a limited geographic area, failing to measure racial attitudes, and/or measuring racial attitudes without accounting for social desirability bias. I analyze racial attitudes of a real-life candidate using a national sample, and I take advantage of a methodological innovation in the measurement of stereotypes that mitigates social desirability problems. These favorable properties of my analysis strengthen my contention that in at least one case, perhaps the most important case to date, many white Americans discriminated against a black candidate in the voting booth.

My approach also adds nuance to the long-standing debate over white discrimination and black candidates. I ask not just whether racial prejudice hurts black candidates but also among which whites prejudice influences the voting decision. I find that in the 2008 election the political impact of prejudice was greatest among Independents, substantial among Democrats, and practically nonexistent among Republicans.

Finally, my findings contribute to our understanding of the nature of contemporary American racial prejudice. Social scientists have by and large turned their attention to symbolic racism or implicit prejudice, and for good reason—measures of explicit prejudice may lead to underestimates of the extent of racial prejudice and therefore of its effects. However, a new self-administered measure introduced in the 2008 ANES, which mitigated social desirability effects, enabled me to detect higher levels of explicit prejudice than respondents were willing to express to an interviewer. This innovation, together with my analysis of the 2008 election, indicates that explicit prejudice is both widespread and influential and therefore may merit increased attention.

Notes

To be sure, it would have been no small feat to obtain the support of a majority of white voters, given that no Democrat has done so since Lyndon B. Johnson. Still, as Lewis-Beck et al. (Lewis-Beck 2009) argue, Obama enjoyed some advantages that his recent Democratic predecessors did not, such as George W. Bush’s record-setting low approval ratings, the economic recession, and the financial meltdown in the months prior to before the election. Indeed, numerous forecasting models overestimated the support Obama would receive (Abramowitz 2008; Holbrooke 2008; Lewis-Beck and Tien 2008; Lockerbie 2008), leading some to suspect prejudice was the cause (e.g., Lewis-Beck and Tien 2009).

If the American National Election Studies 2008 time series survey is used, estimates of Obama’s support among blacks and Latinos are even higher (98 and 75%, respectively).

I do not expect, however, that all scholars will agree that negative stereotypes constitute a measure of racial prejudice. After all, Allport’s (1954/1988) classic definition of prejudice as “an antipathy based on a faulty and inflexible generalization” sets a high bar. Negative generalizations about social groups need not be accompanied by hostility (Jackman 1994). Further, some defend statistical generalizations about social groups, particularly if these generalizations are based on experience (see Pager and Karafin 2009). Finally, the limitations of cross-sectional survey data will certainly not allow me to assess the “flexibility” of generalizations about racial groups. I therefore adopt an etymological perspective. An assessment that one racial group possesses a negative attribute relative to another racial group is a “pre-judgment”; it precedes, but may or may not influence, the evaluation of an individual member of that group, such as Barack Obama.

I exclude those respondents who, though listing their primary racial group as white, also either identified themselves as belonging to the ethnic group of Hispanic/Latino (n = 61) or identified themselves as being of Hispanic descent (n = 14). Results are robust to including either or both of these groups.

Question wording can be found online at www.electionstudies.org.

Respondents are also asked to evaluate Asians and Hispanic-Americans.

The difference measure is potentially subject to the criticism that it also captures the effects of esteem toward blacks (Sniderman and Stiglitz 2008). However, excluding those respondents who rated whites more negatively than blacks on the stereotype scales yields substantively equivalent results.

When examining the ACASI measure of stereotypes, I exclude those respondents who did not participate in the post-election wave in order to ensure comparability.

A couple of caveats are in order. First, interviewers were not randomly assigned to respondents, and I make no attempt to account for that here. Second, race of interviewer was only measured in the pre-election wave, although ANES staff have informed me that respondents almost always had the same interviewer for both waves.

The stereotype index (interviewer measure) shows a high degree of stability dating back to 1992, the first year in which the stereotype questions were asked, and also reveals perhaps a slight decline of about 5% points in negative stereotypes about blacks over that time period.

All regressions in the paper are weighted in order to approximate national representativeness, though unweighted regressions do not substantively change the results.

Pearson’s r = .61 for the ACASI measure and .52 for the interviewer measure.

More precisely, the “lazy” question has a somewhat stronger effect on vote choice than the “intelligent” question. The ratio of the coefficients is about 5:4.

Using the seven-category interval variable for party identification is suboptimal, as it assumes that the effect of moving from any one category to the category next to it is equivalent to any other such effect. The interval variable is easier to present, however, and the substantive results of interest are similar for either form of the variable.

Further, explicit prejudice was not associated with 2008 white respondents’ self-reports of whether they voted for John Kerry rather than another candidate in 2004.

My claim that prejudiced white voters punished Obama for his race does not hinge on the use of stereotypes as the measure of prejudice. The results presented in Table 2 are robust to changing the independent variable of interest from the stereotype index to the symbolic racism index. Further, there is a possibility that positive racial affect caused some whites to vote for Barack Obama. In an alternate model, a variable measuring admiration for blacks was substituted for the stereotype index. The coefficient on this variable was in the expected direction and of moderate size but fell short of conventional standards of statistical significance (one-tailed p < .07). The coefficient decreases to almost zero when the stereotype index is included in the model.

The interviewer measure yields similar results. Although the ACASI measure results in greater reporting of prejudice, a comparison of columns in Table 1 shows that the coefficient on this measure is slightly smaller. These two countervailing factors lead to nearly identical results for the two measures.

A more fine-grained description of the effects of prejudice is as follows. Of those white respondents expressing prejudice against blacks, about one-half scored greater than 0.5 but less than 0.6 on the stereotype index, and their predicted probability of voting for Obama ranged from about 35 to 43%. Another quarter scored greater than or equal to 0.6 but less than 0.7, and their predicted probability of voting for Obama ranged from 28 to 35%. The final quarter scored greater than or equal to 0.7 and less than or equal to 1, and their predicted probability of voting for Obama ranged from 11 to 28%.

Another method of assessing the impact of prejudice is to estimate its total contribution by comparing the mean predicted probability of voting for Obama using the independent variables’ actual values to the mean predicted probability of voting for Obama after setting the stereotype index to its midpoint, at which no prejudice is expressed. I use this method to compare the effect of prejudice when the interviewer measure is used to its effect when the ACASI measure is used. Using the interviewer measure, I estimate that the total contribution of explicit prejudice was to depress the white vote for Obama by 2.81% points. The ACASI measure yields a similar estimate of a decrease of 2.66% points.

Prejudice was also not associated with feeling thermometer scores for John McCain or Sarah Palin.

Sniderman and Carmines make their argument primarily using self-identified ideology rather than partisanship, although they state that “the basic logic remains the same” for partisanship. I examine partisanship because about one-third of ANES respondents refuse to place themselves in an ideological category, consistent with the findings of Converse (1964). My findings are substantively equivalent, however, when ideology is used instead of partisanship.

Sniderman and Carmines do not present the correlation between partisanship and negative stereotypes in the three surveys they analyze from the early 1990s, but they do present the correlation between ideology and their measure of prejudice. This correlation ranges from .09 to .14, close to the correlation between self-identified ideology and the stereotype index in the 2008 ANES, which is .15.

The employment variable was dropped for the regression for Democrats due to multicollinearity resulting from the fact that only a small proportion of the sample was unemployed.

References

Abramowitz, A. (2008). Forecasting the 2008 presidential election with the time-for-change model. PS: Political Science and Politics, 26, 691–696.

Allport, G. W. (1954/1988). The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books Publishers.

Ansolabehere, S., Stewart, C. III. (2009, January/February.). Amazing race: How post-racial was Obama’s victory? Boston Review.

Arkes, H. A., & Tetlock, P. E. (2004). Attributions of implicit prejudice, or “Would Jesse Jackson Fail the Implicit Association Test?”. Psychological Inquiry, 15(4), 257–278.

Banducci, S. A., Karp, J. A., Thrasher, M., & Rallings, C. (2008). Ballot photographs as cues in low-information elections. Political Psychology, 29(6), 903–917.

Baron, A. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2006). The development of implicit attitudes: Evidence of race evaluations from ages 6 to 10 and adulthood. Psychological Science, 17(1), 53–58.

Blanton, H., & Jaccard, J. (2008). Unconscious racism: A concept in pursuit of a measure. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 277–297.

Bobo, L. D. (2000) Race and beliefs about affirmative action: Assessing the effects of interests, group threat, ideology, and racism. In Sears, D. O., Sidanius, J., & Bobo, L. D. (2000). Racialized politics: The debate about racism in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bobo, L. D., Kluegel, J. R., & Smith, R. A. (1997). Laissez-faire racism: The crystallization of “Kinder, Gentler” anti-black ideology. In S. A. Tuch & J. K. Martin (Eds.), Racial attitudes in the 1990s: Continuity and change. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Citrin, J., Green, D. P., & Sears, D. O. (1990). White reactions to black candidates: When does race matter? Public Opinion Quarterly, 54(1), 74–96.

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and discontent. New York: The Free Press.

Curry, T. (2008). How Obama Won the White House. Msnbc.com. Nov. 5, 2008.

Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5–18.

Feldman, S., & Huddy, L. (2005). Racial resentment and white opposition to race-conscious programs: Principles or prejudice? American Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 168–183.

Feldman, S., Huddy, L., & Perkins D. (2009). Explicit racism and white opposition to residential integration. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Association, Chicago, IL: April 2–5.

Fraser, C. (2009). Race, post-black politics, and the democratic presidential candidacy of Barack Obama. Souls, 11(1), 17–40.

Ghanem, K. G., Hutton, H. E., Zenilman, J. M., Zimba, R., & Erbelding, E. J. (2005). Audio computer assisted self interview and face to face interview modes in assessing response bias among STD clinic patients. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 81, 421–425.

Gibbs, N. (2008, November, 5). How Obama rewrote the book. Time Magazine.

Gilens, M., Sniderman, P. M., & Kuklinski, J. H. (1998). Affirmative action and the politics of realignment. British Journal of Political Science, 28, 159–183.

Golebiowska, E. A. (1996). The ‘Pictures in Our Heads’ and individual-targeted tolerance. Journal of Politics, 58(4), 1010–1034.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480.

Henry, P. J., & Sears, D. O. (2002). The symbolic racism 2000 scale. Political Psychology, 23(2), 253–283.

Highton, B. (2004). White voters and african american candidates for congress. Political Behavior, 26(1), 1–25.

Holbrooke, T. M. (2008). Incumbency, national conditions, and the 2008 presidential election. PS: Political Science and Politics, 26, 709–713.

Huddy, L., & Feldman, S. (2009). On assessing the political effects of racial prejudice. Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 423–447.

Hurwitz, J., & Peffley, M. (2005). Explaining the great racial divide. Journal of Politics, 67(3), 762–783.

Jackman, M. (1994). The velvet glove. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kinder, D. R., & McConnaughy, C. M. (2006) Military triumph, racial transcendence, and Colin Powell. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70(2), 139–165.

Kinder, D. R., & Mendelberg, T. (1995). Cracks in American Apartheid: The political impact of prejudice among desegregated whites. Journal of Politics, 57(2), 402–424.

Kinder, D. R., & Sanders, L. M. (1996). Divided by color: Racial politics and democratic ideals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kuklinski, J. H., Cobb, M. D., & Gilens, M. (1997). Racial attitudes and the ‘New South’. Journal of Politics, 59, 323–349.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Tien C., & Nadeau R. (2009, January 7–11). Obama’s missed landslide: A racial cost? Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Southern Political Science Association.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Tien, C. (2008). The job of the president and the jobs model forecast: Obama for’08. PS: Political Science and Politics, 26, 687–690.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Tien, C. (2009). Race blunts the economic effect? The 2008 Obama forecast. PS: Political Science and Politics, 27, 21–22.

Lockerbie, B. (2008). Election forecasting: The future of the Presidency and the House. PS: Political Science and Politics, 26, 713–716.

McCauley, C., Stitt, C. L., & Segal, M. (1980). Stereotyping: From prejudice to prediction. Psychological Bulletin, 80(1), 195–208.

McConahay, J. B. (1983). Modern racism and modern discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9(4), 551–558.

McConahay, J. B., & Hough, J. C., Jr. (1976). Symbolic racism. Journal of Social Issues, 32(2), 23–45.

Moskowitz, D., & Stroh, P. (1994). Psychological sources of electoral racism. Political Psychology, 15(2), 307–329.

Pager, D., & Karafin, D. (2009). Bayesian bigot? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621(1), 70–93.

Payne, B. K., Cheng, C. M., Govorun, O., & Stewart, B. D. (2005). An inkblot for attitudes: Affect misattribution as implicit measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(3), 277–293.

Peffley, M., & Shields, T. (1996). Whites’ stereotypes of African Americans and their impact on contemporary political attitudes. In M. X. Delli-Carpini, L. Huddy, & R. Shapiro (Eds.), Research in micropolitics. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Reeves, K. (1997). Voting hopes or fears? white voters, black candidates, and racial politics in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Riggle, E. D., Ottati, V. C., Wyer, R. S., Kuklinski, J., & Schwarz, N. (1992). Bases of political judgments: The role of stereotypic and nonstereotypic information. Political Behavior, 14(1), 67–87.

Schneider, W. (2008, November, 8) What racial divide? National Journal Magazine.

Sears, D. O. (1988). Symbolic racism. In P. A. Katz & D. A. Taylor (Eds.), Eliminating racism: Profiles in controversy. New York: Plenum.

Sears, D. O., & Kinder, D. R. (1971). Racial tensions and voting in Los Angeles. In W. Z. Hirsch (Ed.), Los Angeles. New York: Praeger.

Sears, D. O., Sidanius, J., & Bobo, L. D. (2000). Racialized politics: The debate about racism in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sigelman, C. K., Sigelman, L., Walkosz, B. J., & Nitz, M. (1995). Black candidates, white voters. American Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 243–265.

Sniderman, P. M., & Carmines, E. G. (1997). Reaching beyond race. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sniderman, P. M., & Piazza, T. (1993). The scar of race. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sniderman, P. M., & Stiglitz, E. H. (2008). Race and the moral character of the modern American experience. The Berkeley Electronic Press, 6(4), Article 1.

Sniderman, P. M., & Tetlock, P. E. (1986). Symbolic racism: Problems of motive attribution in political analysis. Journal of Social Issues, 42(2), 129–150.

Steele, S. (2008, November, 5). Obama’s post-racial promise. The Los Angeles Times.

Terkildsen, N. (1993). When white voters evaluate black candidates: The processing implications of candidate skin color, prejudice, and self-monitoring. American Journal of Political Science, 37(4), 1032–1053.

Thernstrom, A. (2008, November, 6). Great black hope? The reality of President-Elect Obama. National Review Online.

Valentino, N. A., & Sears, D. O. (2005). Old times there are not forgotten: Race and partisan realignment in the contemporary south. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 672–688.

Villarroel, M. A., Turner, C. F., Eggleston, E., Al-Tayyib, A., Rogers, S. M., Roman, A. M., et al. (2006). Same-gender sex in the United States. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70(2), 166–196.

Voss, D. S., & Lublin, D. (2001). Black incumbents, white districts. American Politics Research, 29, 141–182.

Acknowledgements

I thank Arthur Lupia, Vincent L. Hutchings, and Adam Seth Levine for invaluable guidance throughout the course of the project. I am also grateful for comments from Inger Bergom, Ted Brader, Nancy Burns, John E. Jackson, Nathan Kalmoe, Yanna Krupnikov, Nadav Tanners, and several anonymous reviewers. Finally, I thank participants in Arthur Lupia’s graduate course on the 2008 American National Election Studies: L.S. Casey, Abraham Gong, Sourav Guha, Ashley Jardina, Kristyn L. Miller, and Timothy J. Ryan, and attendees at the University of Michigan’s Election 2008 Conference, especially Rosario Aguilar-Pariente, Allison Dale, and Nicholas A. Valentino.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piston, S. How Explicit Racial Prejudice Hurt Obama in the 2008 Election. Polit Behav 32, 431–451 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9108-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9108-y