Abstract

Aims

Although water conservation in rice production has become increasingly important, the effects of water management on the allocation and dynamics of carbon (C) within the rice-soil system remain unknown.

Methods

We compared the allocation and dynamics of C assimilated by rice under continuously flooded, non-flooded and alternate water regimes. Rice (Oryza sative L. cv. Luliangyou 996) was labeled with 14CO2 and harvested 7 times within 45 days.

Results

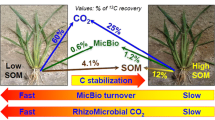

More 14C was released from roots into the soil in non-flooded and alternate water regimes treatments. Microbial 14C decreased with time after the labeling and was lowest under flooded condition. Roots and rhizomicrobial respiration followed the order of non-flooded > alternate water regimes > flooded treatment. Water management affected 14C distribution in aggregates with more 14C in macroaggregates in the non-flooded treatment. Estimated amounts of C transferred remaining belowground by rice 45 days after labeling were 1,986, 2,827 and 2,472 kg C ha−1, of which rhizodeposition accounted for about 41 %, 16 % and 30 % of C transferred belowground under non-flooded, flooded and alternate water regimes, respectively.

Conclusions

Water management affected the allocation and dynamics of recently assimilated C within the rice-soil system and also changed the relative contribution of rhizodeposition to C transferred belowground. This study suggests the differences in the driving mechanisms of C sequestration under flooded vs. non-flooded and alternate water regimes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rice is the major staple food crop in Asia, and it consumes about 90 % of total irrigation water (Bhuiyan 1992). However, freshwater for irrigation is becoming scarce due to increasing competition from industrial and urban demand (Bouman and Tuong 2001), Further, seasonal drought during the rice-growing season exacerbates the effects of water shortage on rice production in some typical regions (Guo et al. 2007). These have threatened the sustainability of irrigated rice systems and, therefore, water conservation methods in rice production were introduced and developed.

These water conservation techniques included non-flooded mulching cultivation (Fan et al. 2005), alternate wetting and drying irrigation (Bouman and Tuong 2001; Belder et al. 2004), continuous soil saturation (Borrell et al. 1997), internal drainage (Ramasamy et al. 1997), and aerobic rice systems (Bouman et al. 2006). This has been accompanied by documenting the effects of these water managements on rice yield (Bouman and Toung 2001), water use efficiency (Belder et al. 2004), methane emission (Minamikawa and Sakai 2005) and plant physiological responses (Yang et al. 2002).

Recent attention has focused on soil organic carbon (SOC) storage in rice-based systems under different water managements, in particular because of concerns over atmospheric CO2 levels and global warming (Hu et al. 1997). Paddy soils play an important role in mitigating global warming because these soils represent a large portion of global cropland. Most C addition to soil originates from plants through deposition of leaf and root litter as well as rhizodeposition (Rees et al. 2005; Kuzyakov and Domanski 2000). About 50 % of the C fixed by net photosynthesis is transferred belowground, and 5–10 % of photosynthetically fixed C can be recovered in soil during the vegetation season (Kuzyakov and Domanski 2000; Nguyen 2003). Water conservation techniques applied in rice systems shift the original balance between anaerobic and aerobic factors (water and redox conditions) and thus affect the turnover and dynamics of SOC. For example, compared with continuously flooded system, non-flooded rice systems can lead to a short-term decrease (Li et al. 2007) or maintain (Fan et al. 2005, 2012) of the total SOC and soil total nitrogen (TN). This calls for evaluating the fate and dynamics of assimilated C within the rice-soil system in relation to water management. Only a few studies have evaluated the distribution of photosynthesized C within the rice-soil system under flooded condition using isotopic techniques (Watanabe et al. 2004; Lu et al. 2002a, b, 2004). Therefore, little information is available on the effects of water management regimes on the partitioning and translocation of plant-assimilated C within the rice-soil system.

Soil moisture being one of the important abiotic factors for rice growth can affect rice physiology. Thakur et al. (2011) reported that controlled water irrigation improved rice plants’ morphology and physiology compared with continuously flooded condition. Rice under alternate wetting and drying or non-flooded conditions can enhance roots activity and develop more fine roots (Mishra and Salokhe 2011). These may change the partitioning of photosynthesized carbon and affect rhizodeposition.

Labile SOC pools such as dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and microbial biomass carbon (MBC) can be strongly affected by water conservation management. A considerable part of DOC in the soil originates from rhizodeposition (reviewed by van Hees et al. 2005), while microbial biomass plays a crucial role in transforming rhizodeposited C and is always highly labeled by the newly assimilated C (Kaštovská and Šantrůčková 2007). Lu et al. (2002a) found that 0.15–0.94 % of photosysthesized 13C was incorporated into MBC immediately after pulse labeling of flooded rice, and 0.18–0.75 % still remained at the end of the growing season. Changing the rice growing environment from continuously flooded to aerobic or alternate anaerobic/aerobic would affect the dynamics of microorganisms and DOC. For example, microbial biomass decreased under the non-flooded vs. continuously flooded treatment (Li et al. 2006). Soil redox condition can enhance or stabilize DOC through Fe oxyhydroxides (reviewed by Kögel-Knabner et al. 2010). DOC is a primary energy source for microorganisms and can affect microorganism activity and abundance in the soil (Blagodatskaya et al. 2009); however, the effects of rhizodeposition and especially the quantity and quality of labile DOC fraction on microbial biomass as related to water management in paddy soil remain to be determined.

The dynamics of soil aggregates have gained increasing attention because of their role in C sequestration and in maintaining SOC level. This makes it necessary to have more information on how the partitioning and stabilization of recently assimilated C is affected by changes of aggregate size fractions as related to water management in paddy soil. Reducing conditions and associated physicochemical changes may lead to soil disaggregation (De-Campos et al. 2009). Despite obvious effects of soil moisture on aggregation, no studies have investigated the effects of water management on the allocation of roots-derived C in aggregate fractions.

In the current study, we studied the effects of water management on the allocation and dynamics of assimilates by labeling rice with 14CO2 at young stage under controlled laboratory condition. The objectives of this study were to (1) determine the allocation and dynamics of new assimilates among pools within the rice-soil systems, and (2) evaluate amounts of C transferred by rice belowground and rhizodeposition under various water management regimes.

Materials and methods

Experimental set-up

The soil samples (Anthrosols) were collected from the plough layer (0–20 cm) of a rice field at Dong Kou city, Hunan province, China (110° 62′N and 27°12′E). The samples had the following characteristics: 1.9 % SOC content; 0.24 % TN content; soil pH (H2O) 5.49; available K 92.9 mg kg−1.

The soil was first sieved (<5 mm), then 360 g soil were filled into each plastic pot (height: 12 cm; inner diameter: 8 cm) and rewetted to 85 % of the water holding capacity (WHC). The pots used for CO2 trapping (see below) had one vent in the lid and another one in the bottom. Sixty-three pots were used in this experiment.

The rice seeds (Oryza sative L. cv. Luliangyou 996) were germinated on wet filter paper for 3 days. Depended on seedlings numbers transplanted per ha on-farm locally, we estimated numbers in seedling transplanted in each pot in this study. Thus, three healthy germinated rice seedlings were transplanted to each pot. Fertilizers consisting of CO (NH2)2 and KH2PO4 at the rate of 100 mg N and 12.5 mg K per kg soil was used in this experiment. 30 % N was basal fertilizer, 30 % N and 40 % N was top dressing on day 15 and 28. All the K was basal fertilizer. Additionally, 3.5 g L−1 KH2PO4 was directly added to the leaves 11 days after planting. The total N rate was calculated depended on rate of 150 kg N ha−1 in line with recommended practices locally.

Three soil water regimes were established, consisting of (1) continuously flooded (F), pots were flooded with distilled water to a level of 4–5 cm above soil surface, (2) non-flooded (NF), pots were maintained at 85–90 % of the WHC, (3) alternate wetting and drying (AWD), pots were flooded as described above for F, then dried for 3–4 days until the soil water content reached 70–75 % of the WHC, then flooded again; this kept the soil under alternate flooded and dried conditions. These three water regimes started after the development of three leaves per plant. The plants were grown for 14 h per day at a light density of 400 umol m−2 s−1 and a temperature of 27 ± 1 °C and 22 ± 1 °C (day: night).

14C pulse labeling

The labeling took place on day 35 after transplanting. The labeling apparatus, previously described by Kuzyakov et al. (2001), consists of a two-compartment Plexiglas chamber. The day before labeling, we covered the pots with black plastic sheets to avoid algal photosynthesis and direct diffusion of the tracer into the soil. The hole around the stem in the lid of the pots for soil CO2 trapping was sealed with silicon paste (NG 3170, Thauer & Co., Dresden, Germany) and tested for air leaks. Briefly, 18 pots with 54 plants were placed into one chamber. The chamber was connected by tubing with a flask containing Na 142 CO3 (ARC Inc., USA) solution with a 14C activity of 444 KBq per plant. 14CO2 was released into the chamber by adding 10 ml of 5 M H2SO4 to the labeling solution. The plants were labeled during 5 h in the 14CO2 atmosphere. Before opening the labeling chamber, the air was pumped for 1 h through 15 ml of 1 M NaOH solution to remove unassimilated 14CO2. Immediately after the labeling, we started soil CO2 trapping by pumping in a closed circle through 15 ml of 1 M NaOH. Water traps, consisting of 20-cm-long glass tubes (inner diameter 3 cm), were placed in front of NaOH vessels to avoid water flyover.

Harvesting procedure and soil sampling

Plant and soil samples were taken at 6 h, 2 d, 6 d, 14 d, 33 d, 37 d and 45 d after labeling, with three replicates for each sampling day and treatment. The pots used for CO2 trapping were harvested on day 45. At harvest, shoots were cut at the base and soil was taken out of pot. The roots were separated from soil by handpicking and washed with 100 ml deionized water to remove the soil adhering to the roots. Shoots and roots were dried at 60 °C. Soil samples were divided into several parts: one part of fresh soil was used to analyze MBC and DOC. Another part of the soil was oven-dried at 105 °C to determine the water content. Furthermore, fresh soil samples were stored at 4 °C in airtight polypropylene bags for aggregate fractionation.

Aggregate fractionation

Soil sampled 6 h, 2 d, 14 d, 33 d, 37 d and 45 d after the labeling was prepared for aggregate fractionation. Aggregates were isolated according to Kristiansen et al. (2006). The samples were spread out thinly on aluminum foil and dried to optimal moisture at 40 °C for 10–15 min. Soil was gently, manually crumbled to ca. 5 mm pieces, and 100 g was transferred to two sieves (2 and 0.25 mm) and shaken for 2 min. Thereafter, the remaining aggregates on top of the sieves were collected. Large macroaggregates (2–5 mm) were collected from the 2 mm sieve and small macroaggregates (2–0.25 mm) were collected from the 0.25 mm sieve. The remaining material was passed through the 0.25 mm sieve and classified as microaggregates (<0.25 mm). Preliminary tests showed that the sieving duration was sufficient to quantitatively separate the various aggregate size-classes while minimizing aggregate abrasion during the sieving (Dorodnikov et al. 2009).

Sample analysis

The total C content in trapped CO2 was determined by titration of 1 ml of the NaOH solution with 0.1 M HCl against phenolphthalein after adding 1 ml of 0.5 M BaCl2 solution (Zibilske 1994). The 14C activity of CO2 trapped in NaOH solution was measured in 1 ml aliquots added to 6 ml Rothiscint scintillation cocktail (Roth Company, Germany) after the decay of chemiluminescence by a Liquid Scintillation Counter (LS 6500 Multi-Purpose Scintillation Counter, 217 Beckman, USA). The 14C counting efficiency was about 92 % and the 14C activity measurement error did not exceed 2 %.

Dry samples of shoots, bulk soil, soil aggregate fractions and roots were pulverized in a ball mill prior to analysis for radioactivity and for total C and N determination. Radioactivity of samples was measured after combustion of 50 mg of plant sample or 500 mg of soil sample within an oxidizer unit (Feststoffmodul 1300, AnalytikJena, Germany) with Liquid Scintillation Counter as described above. Additionally, 3–40 mg of milled shoots, roots and soil samples were weighed in tin capsules to determine the C contents by an element analyzer (Vario EL III, Elementar, Hanau, Germany).

Soil microbial biomass carbon was determined by chloroform fumigation extraction (Wu et al. 1996). Briefly, 10 g fresh soil were shaken with 40 ml of 0.05 M K2SO4 for 1 h at 200 rev min−1, centrifuged at 3000 rev min−1 for 10 min, and filtrated. Another 10 g fresh soil were fumigated with chloroform for 24 h and extracted in the same way. Total C concentrations were measured with a TOC/TIC analyzer (Dimatec, Essen, Germany). MBC was calculated as the difference between the C content of the fumigated and the non-fumigated extracts and divided by a KEC factor of 0.45 (Wu et al. 1996). We assume that the C concentration in the K2SO4 extraction of non-fumigated soil corresponds to the DOC fraction. The 14C activity of MBC and DOC solution was measured in 3 ml aliquots added to 6 ml Rothiscint scintillation cocktail (Roth Company, Germany) after the decay of chemiluminescence using the above Liquid Scintillation Counter (for counting efficiency and measurement see above).

Calculations and statistical analysis

The C amount (kg C ha−1) was calculated by using the following equation according to Kuzyakov et al. (2001):

where Ci is the C amount in the investigated pool (kg C ha−1), Cshoots is the C amount in the shoots (kg C ha−1), 14Ci is the 14C activity transferred to the individual pool (KBq) and 14Cshoots is the 14C activity in the shoots (KBq). This method of calculation allows a rough estimation of C transferred belowground as the parameters of Eq. 1 were not constant during plant development. This estimation approach was used to recalculate the relative results of 14C tracer distribution after the pulse labeling for absolute amounts of C allocation. It can be used only for periods of linear plant growth and was used after 14C distribution in the plant and the achievement of the stage near equilibrium. The 14C activity and the amount of C in shoots were chosen as reference because these can be measured more accurately in shoots compared with other compartments (roots, CO2, soil). The mass of the shoots for ha were calculated using the surface area of the experiment pot.

The 14C activity in individual pools was expressed as the percentage of 14C recovery at each sampling day. The total 14C recovery after sampling was the sum of the 14C activity in shoots, roots, soil and CO2.

The significant differences between treatments on each sampling day were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with SPSS (Version 11.0, 2002, SPSS Inc., USA).

Results

Shoots and roots biomass

Shoots and roots biomass increased after the labeling for all treatments (Table 1). The highest shoots and roots biomass were observed under flooded condition, while the non-flooded treatment had the lowest shoots and roots biomass.

Allocation of rice-assimilated 14C in shoots

The highest 14C recovery in the shoots was detected directly after labeling for all treatments, and there were no differences between the treatments (Fig. 1). The 14C recovery in shoots followed a power function decrease with time for all treatments. 14C losses from the shoots in the flooded treatment were always slower than in the non-flooded and the alternate water regime treatments. The 14C recovery in the shoots at the end of the experiment was significantly larger for the flooded vs. alternate water regime treatment.

14C dynamics in shoots over 45 days after the pulse labeling. Data points are means and error bars represent standard error (n = 3). Means followed by different letters are significantly (p < 0.05) different between treatments on each sampling day (NF: non-flooded; F: continuously flooded; AWD: alternate wetting and drying). Curves are fitted using a one-phase power function model according to individual dates (solid line for NF, long dash line for F and dotted line for AWD)

Belowground 14C allocation after pulse-labeling

Contrary to the shoots, the 14C recovery in roots of all treatments followed a power function increase with time (Fig. 2a). Despite the absence of significant differences of the 14C recovery in roots between water treatments at the beginning, the non-flooded treatment showed a significantly lower 14C recovery starting from day 2 to day 45.

14C recovery in roots (a), soil (b) and accumulated respiration (c) over 45 days after the pulse labeling. Data points are means and error bars represent standard error (n = 3). Means followed by different letters are significantly (p < 0.05) different between treatments on each sampling day (NF: non-flooded; F: continuously flooded; AWD: alternate wetting and drying). Curves are fitted using a one-phase power function model according to individual dates (solid line for NF, long dash line for F and dotted line for AWD)

The 14C recovery in the soil was significantly lower in the flooded treatment compared to non-flooded and the alternate water regime treatments during the experiment, except for day 0 (Fig. 2b). For the non-flooded treatment, 14C recovery in soil increased from 7.2% on day 0 to 10.4 % on day 2, and remained at that level for the rest of the experiment. In contrast, the recovery in soil showed the highest values directly after labeling for the flooded and the alternate water regime treatments, and then decreased significantly during the first 2 days.

Compared to the non-flooded and the alternate water regime treatments, the cumulative 14C of roots and rhizomicrobial respiration for flooded treatment was always significantly lower and gradually increased from 5.8 % to 14.4 % during the experiment (Fig. 2c). 14C respiration in the alternate water regime treatment was between that of the flooded and the non-flooded treatments, and the cumulative roots and rhizomicrobial respiration increased from 8.0 % to 22.1 % of recovered 14C during the experiment.

Total MBC and DOC content did not vary significantly during the experiment (data not shown). The former (averaged across 5 sampling days) was about 351–370 mg C kg−1 for three treatments, and no significant differences were detected between treatments. The average total DOC content was 32.9, 42.1 and 30.9 mg C kg−1 for non-flooded, flooded and alternate water regime, respectively. The average DOC content was significantly higher in flooded treatment than in the non-flooded and alternate water regimes.

The 14C recovery in MBC was highest 6 h after labeling for all treatments, and it significantly decreased during the first 2 days (Fig. 3a). Compared to the flooded treatment, the percentage of 14C recovery in MBC was significantly higher in the non-flooded and alternate water regimes treatments.

14C dynamics in microbial biomass C (a) and dissolved organic C (b) over 45 days after the pulse labeling. Data points are means and error bars represent standard error (n = 3). Means followed by different letters are significantly (p < 0.05) different between treatments on each sampling day (NF: non-flooded; F: continuously flooded; AWD: alternate wetting and drying). Curves are fitted using a one-phase power function model according to individual dates (solid line for NF, long dash line for F and dotted line for AWD)

The 14C recovery in DOC was also highest 6 h after the labeling for all treatments (Fig. 3b). There was a fast 14C decline in DOC during the first 2 days for all treatments, followed by a slower decline thereafter. The recovery in DOC did not differ significantly between the treatments.

The sieving procedure fractionated the bulk soil into aggregate size classes with large macroaggregates (>2.00 mm), small macroaggregates (0.25–2.00 mm), and microaggregates (<0.25 mm) representing on average 46 %, 38 % and 16 % of the bulk soil mass, respectively (Fig. 4a). Water management affected the aggregates size distribution. Compared to the flooded and the non-flooded treatments, the alternate water regimes treatment significantly decreased large macroaggregates and increased microaggregates. The SOC content in each aggregate class was similar to the content in the bulk soil (data not shown).

Aggregate-size distribution averaged for 5 sampling days (a), and specific 14C activity in aggregate-size fractions of non-flooded (b), continuously flooded (c) and alternate wetting and drying (d). Data points are means and error bars represent standard error (n = 3). Curves are fitted using a one-phase power function model according to individual dates (solid line for >2 mm aggregate, long dash line for 2–0.25 mm aggregate and dotted line for <0.25 mm aggregate)

Specific 14C activity of aggregate size fractions changed with water management and time (Fig. 4b, c and d). More 14C was incorporated into macroaggregates in non-flooded treatment, while the activity in all aggregate fractions did not change significantly during 45 days (Fig. 4b). However, the highest activity of all aggregate size fractions was detected 6 h after labeling, both in flooded and alternate water regimes treatments (Fig. 4c and d). The 14C distribution among aggregates fractions did not differ significantly either in flooded or alternate water regimes treatments.

C transferred by rice belowground

By using the 14C content in the soil with roots on day 45 as 14Ci (%), we calculated (Eq. 1) that C amounts transferred remaining belowground were 1,986, 2,827, 2,472 kg C ha−1 in the non-flooded, flooded and alternate water regime treatments, respectively. Significant differences were detected between flooded and non-flooded treatments, but not between flooded and alternate water regimes treatments.

The input of C from living roots system into the soil has been termed rhizodeposition, which composing of exudation, secretion, sloughing and lysis of cells and root tissue senescence (Rees et al. 2005). Rhizodeposition estimated based on the 14C content remaining only in the soil on day 45 as 14Ci (%), was 822, 460, 640 kg C ha−1, which accounted for about 41 %, 16 % and 30 % of new transferred C remaining belowground for the non-flooded, flooded and alternate water regimes, respectively. Significantly less rhizodeposition was found under flooded condition.

Discussion

Effect of water management on allocation of assimilates in shoots

The 14C recovery in shoots decreased with time for all treatments (Fig. 1). This was due to shoots respiration and belowground allocation of assimilates and their use for respiration (Swinnen et al. 1994; Domanski et al. 2001). Newly fixed C is preferentially respired by plants (Staddon et al. 2003) and, in grasses, between 30 % and 90 % of total fixed C can be lost by respiration (Kaštovská and Šantrůčková 2007). Belowground translocation is another mechanism that decreases the labeled C in shoots (Kuzyakov and Domanski 2000). In this study, the 14C recovery in shoots was higher for the flooded treatment compared to non-flooded and alternate water regimes treatments (Fig. 1). This may be connected with lower shoots respiration and/or to lower 14C release from roots into the soil (Fig. 2b) and used for roots and rhizomicrobial respiration (Fig. 2c).

Effect of water management on allocation of assimilates in belowground pools

14C recovery in the roots was higher under flooding vs. non-flooded and alternate water regimes (Fig. 2a). We explain this first with less exudation from flooded roots. Reid (1974) examined the effect of water level on exudation by roots and reported that exudation decreased when water potential increased from −200 kpa to 0. Similarly, fewer assimilates were released by roots when plants were grown in open pots that were regularly leached with distilled water (Martin 1975; Barber and Martin 1976). Higher 14C recovery in flooded roots is also connected with lower roots and rhizomicrobial respiration in flooded soil (Fig. 2c). Similar to our observations, lengthier anaerobiosis (48 h) can decrease 14C in CO2 efflux from soil under perennial ryegrass compared to the aerobic control (Meharg and Killham 1990). Roots under anaerobic condition may produce substances such as ethanol and lactate, which are toxic to plant roots and microorganisms, thus decreasing roots and rhizomicrobial 14CO2. Conversely, rice grown under controlled irrigation and alternate water regimes usually has higher activity and more fine roots (Mishra and Salokhe 2011; Thakur et al. 2011).

The 14C recovery in soil was about 10.8 %, 5.3 % and 7.9 % on day 45 for the non-flooded, flooded and alternate water regimes treatment, respectively (Fig. 2b). Similar to our study, Watanabe et al. (2004) showed 4.3 % of the recovered C was transferred to flooded soil 14 days after labeling, during the maximum-tiller-number stage of the rice. The lower 14C recovery in flooded soil further coincides with results of more 14C remaining in roots in the flooded condition (Fig. 2a), showing lower 14C exudation from roots into soil under flooded condition.

The total MBC content did not vary significantly within or between treatments. This finding was contrary to previous study which has shown a decrease in microbial biomass after exposure to drying-rewetting events (Schimel et al. 2007). This may be ascribed to relative short duration or intensity of drying-rewetting cycles (Borken and Matzner 2009). Similarly, Fierer and Schimel (2002) found evident effects of drying-rewetting on MBC dynamics until 6 weeks later. Total DOC concentration was significantly higher in the flooded vs. non-flooded and alternate water regimes. Soil redox conditions can enhance or stabilize DOC through Fe oxyhydroxides in paddy soil (reviewed by Kögel-Knabner et al. 2010). The anaerobic condition may decrease DOC adsorption and increase the DOC concentration in flooded soil.

The 14C recovery in MBC was significantly lower in the flooded vs. non-flooded and alternate water regime (Fig. 3a). This may be caused partly by fewer rhizodeposits in the flooded soil (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, we found that the flooded treatment also showed a significantly lower proportion of 14C in DOC as MBC, as compared to the other two treatments (data not shown). This indicates that lower DOC availability may be another factor explaining the lower 14C in microbial biomass under flooding. Although DOC is the primary energy source for microorganisms and can affect their activity and abundance in the soil (Blagodatskaya et al. 2009), the effects also strongly depend on the quality of DOC (Amon et al. 2001). It has been documented that lignin-derived compounds might make up a larger portion of DOM in continuously flooded paddy soil as result of the hampered degradation of phenolic compounds under anoxic conditions (Kirk 2004; Kögel-Knabner et al. 2010). Thus there could have been more complex compounds which are relatively stable against microbial decay in flooded condition.

14C recovery in the MBC and DOC decreased with time for all treatments (Fig. 3a). The highest 14C recovery in MBC was detected directly after labeling for all treatments, confirming a very rapid incorporation of newly assimilated C into microorganisms (Kuzyakov and Gavrichkova 2010). Maximum incorporation into microbial biomass usually was detected within 24 h of pulse labeling (Kaštovská and Šantrůčková 2007; Butler et al. 2004; Domanski et al. 2001). The rapid incorporation of 14C into MBC is also shown by the lower 14C of DOC pools after labeling (Fig. 3b). This agrees with Fischer et al. (2010), who demonstrated that microorganisms can quickly take up labeled low-molecular-weight organic substance exudates. However, compared to other studies, the amount of 14C recovered in MBC in this study was higher directly after labeling. This might reflect partial co-extraction of labeled substances allocated in roots hairs and fine roots by the fumigation-extraction approach.

Effect of water management on allocation of assimilates in aggregates

The aggregate size fractionation method used here was chosen because it is gentler than conventional wet and dry sieving methods (Kristiansen et al. 2006). Wet-sieving method releases water soluble organic matter and may loss some 14C or cause redistribution of 14C assimilates among aggregates fractions. In turn, prolonged sieving of air-dry soil tends to increase abrasion rather than fragmentation due to the greater tensile strength of dry aggregates (Dorodnikov et al. 2009). However, compared with wet and dry sieving methods, we can not isolate silt and clay fraction (<53 μm) because of the moisture optimal used here.

Water management strongly influenced the distribution of new assimilates between the aggregate fractions. More new 14C assimilates were incorporated into macroaggregates under non-flooded condition (Fig. 4b). This reflected that roots-derived C is initially incorporated between and within large macroaggregates (Jastrow 1996). There were no obvious differences in 14C distribution among aggregate fractions under flooded and alternate water regime (Fig. 4c and d). Water pretreatment can strongly influence the distribution of roots-derived 14C in aggregate fractions; stable macroaggregates in soil, which can survive slaking, show higher concentrations of new roots-derived C than less stable macroaggregates (Gale et al. 2000; Gale and Cambardella 2000). Flooded and alternate water regimes treatments increase the portion of unstable macroaggregates and also increase the incorporation of 14C assimilates in microaggregates.

14C dynamics in aggregates depended on the water regimes. 14C in macro- and microaggregates tended to increase with time under the non-flooded treatment. The large variability, however, yielded a low R2 value of the fitted power function (Fig. 4b). This trend contrasts previous incubation experiments (Gale et al. 2000a; Angers et al. 1997), in which the labeled substances decreased in macroaggregates but increased in microoaggregates with time. Comparing these experiments with our study showed that the shorter time (45 d) in our study may explain the differences to previous investigations.

C transferred belowground by rice

C transferred by rice remaining belowground 45 days after pulse labeling was 1,986, 2,827, 2,472 kg C ha−1 in the non-flooded, flooded and alternate water regimes treatment, respectively. Rhizodeposition was lowest in flooding condition. As discussed above, this was due to less 14C assimilates released from roots and also less was used for roots and rhizomicrobial respiration. The estimation of C transferred remaining belowground and rhizodeposition for flooded rice in the current study are higher than was reported previously, Lu et al. (2002b) reported that C transferred remaining belowground and rhizodeposition were 1,065 kg C ha−1 and 200 kg C ha−1 for flooded rice, respectively. This is due to higher shoots or roots biomass C (4,560 kg C ha−1 for shoots and 1,703 kg C ha−1 for roots 45 days after labeling for flooded treatment) in our study than that of previous study (roots biomass C, 894 kg C ha−1). Compared with flooded treatment, the non-flooded and alternate water regimes treatments increased not only the amount of rhizodeposition, but also the proportion of C transferred remaining belowground as rhizodeposition (41 %, 30 % vs. 16 %). Amos and Walters (2006) once reported net rhizodeposition contributes 5–62 % of C transferred remaining belowground by summarizing 12 maize studies. Rhizodeposition of roots exudates can lead to C accumulation or C consumption due to influence on microorganisms (Kuzyakov et al. 2001). In the current study, increase the amount and relative proportion of rhizodeposition are consistent with the higher roots and rhizomicrobial respiration under the non-flooded and alternate water regimes treatments (Fig. 2c). It is possible that the non-flooded and alternate water regimes treatments would lead to higher priming effects and loss in native soil carbon. Thus, the non-flooded and alternate water regimes for rice may lead to tradeoffs between water conservation and less soil C sequestration. This may support observations from the existed field experiments that non-flooded rice system with plastic film mulching saved irrigation water by more than 60 %, but with lower or similar SOC concentration compared with continuously flooded system (Fan et al. 2005, 2012; Li et al. 2007). However, the impacts of rhizodeposition on soil organic matter (SOM) turnover also depend on the source or form of the rhizodeposits. When labile rhizodeposits preferentially assumed by microbes, rhizodeposition may retard decomposition of more recalcitrant plant residues and native SOM (Johnson et al. 2006). Under flooded treatment, the low proportion of new transferred C remaining belowground as rhizodeposition 45 days after labeling suggests that roots are the most sink of new C belowground. This indicates that C sequestration in traditionally flooded paddy soil is mainly driven by roots and not of rhizodeposition.

Conclusions

Our results showed that water management regimes affected the allocation and dynamics of recently assimilated C within the rice-soil system. More assimilated C remained in shoots and roots under continuously flooded treatment. Higher assimilates were released from roots into the soil and for roots and rhizomicrobial respiration under non-flooded and alternate water regimes. The non-flooded and alternate water regimes treatments increased both the amount and proportion of C transferred remaining belowground as rhizodeposition. This may suggest the differences in the driving mechanisms of C sequestration under flooded vs. non-flooded and alternate wetting and drying treatments. It should be noted that we conducted this study under controlled laboratory condition and limited this study to young rice stage. It remains necessary to quantify C flow within the rice-soil system under different water managements at different growth stages in field condition, especially at grain stage. Additionally, the studies of rhizodeposition effects on priming effects in soil under different water management are also necessary to help us to understand how the increase of rhizodeposition under non-flooded and alternate water regimes changes C cycling of paddy soil.

Abbreviations

- SOC:

-

Soil organic carbon

- SOM:

-

Soil organic matter

- TN:

-

Soil total nitrogen

- DOC:

-

Dissolved organic carbon

- MBC:

-

Microbial biomass carbon

- WHC:

-

Water holding capacity

- F:

-

Continuously flooded

- NF:

-

Non-flooded

- AWD:

-

Alternate wetting and drying

- C- carbon:

-

CO2- carbon dioxide

References

Amon RMW, Fitznar HP, Benner R (2001) Linkages among the bioreactivity, chemical composition, and diagenetic state of marine dissolved organic matter. Limnol Oceanogr 46:287–297

Amos B, Walters DT (2006) Maize root biomass and net rhizodeposited carbon: an analysis of the literature. Soil Sci Soc Am J 70:1489–1503

Angers DA, Recous S, Aita C (1997) Fate of carbon and nitrogen in water-stable aggregates during decomposition of 13C15N-labelled wheat straw in situ. Eur J Soil Sci 48:295–300

Barber DA, Martin JK (1976) The release of organic substances by cereal roots into soil. New Phytol 76:69–80

Belder P, Bouman BAM, Cabangon R, Lu G, Quilang EJP, Li YH, Spiertz JHJ, Tuong TP (2004) Effect of water-saving irrigation on rice yield and water use in typical lowland conditions in Asia. Agr Water Manage 65:193–210

Bhuiyan SL (1992) Water management in relation to crop production: case study on rice. Outlook Agr 21:293–299

Blagodatskaya ЕV, Blagodatsky SА, Anderson TH, Kuzyakov Y (2009) Contrasting effects of glucose, living roots and maize straw on microbial growth kinetics and substrate availability in soil. Eur J Soil Sci 60:186–197

Borken W, Matzner E (2009) Reappraisal of drying and wetting effects on C and N mineralization and fluxes in soils. Global Change Biol 15:808–824

Borrell A, Garside A, Fukai S (1997) Improving efficiency of water use for irrigated rice in a semi-arid tropical environment. Field Crop Res 52:231–248

Bouman BAM, Tuong TP (2001) Field water management to save water and increase its productivity in irrigated lowland rice. Agr Water Manage 49:11–30

Bouman BAM, Yang XG, Wang HQ, Wang ZM, Zhao JF, Chen B (2006) Performance of aerobic rice varieties under irrigated conditions in North China. Field Crop Res 97:53–65

Butler JL, Bottomley PJ, Griffith SM, Myrold DD (2004) Distribution and turnover of recently fixed photosynthate in ryegrass rhizospheres. Soil Biol Biochem 36:371–382

De-Campos AB, Mamedov AI, Huang CH (2009) Short-Term reducing conditions decrease soil aggregation. Soil Sci Soc Am J 73:550–559

Domanski G, Kuzyakov Y, Siniakina SV, Stahr K (2001) Carbon flows in the rhizosphere of ryegrass (Lolium perenne). J Plant Nutr Soil Sc 164:381–387

Dorodnikov M, Blagodatskaya E, Blagodatsky S, Marhan S, Fangmeier A, Kuzyakov Y (2009) Stimulation of microbial extracellular enzyme activities by elevated CO2 depends on soil aggregate size. Global Change Biol 15:1603–1614

Fan MS, Liu XJ, Jiang RF, Zhang FS, Lu SH, Zeng XZ, Christie P (2005) Crop yields, internal nutrient use efficiency, and changes in soil properties in rice-wheat rotations under non-flooded mulching cultivation. Plant Soil 277:265–276

Fan MS, Lu SH, Jiang RF, Six J, Zhang FS (2012) Long-term non-flooded mulching cultivation influences rice productivity and soil organic carbon. Soil Use Manage (Accepted).

Fierer N, Schimel JP (2002) Effects of drying-rewetting frequency on soil carbon and nitrogen transformations. Soil Biol Biochem 34:777–787

Fischer H, Ingwersen J, Kuzyakov Y (2010) Microbial uptake of low-molecular-weight organic substances out-competes sorption in soil. Eur J Soil Sci 61:504–513

Gale WJ, Cambardella CA (2000) Carbon dynamics of surface residue- and root-derived organic matter under simulated no-till. Soil Sci Soc Am J 64:190–195

Gale WJ, Cambardella CA, Bailey TB (2000) Root-derived carbon and the formation and stabilization of aggregates. Soil Sci Soc Am J 64:201–207

Guo SW, Wu LH, Shen QR, Zhang FS (2007) Theory and practice of non-flooded mulching rice cultivation in China. China Agricultural University Press, Beijing (in Chinese)

Hu S, Coleman DC, Carroll CR, Hendrix PF, Beare MH (1997) Labile soil carbon pools in subtropical forest and agricultural ecosystems as influenced by management practices and vegetation types. Agr Ecosyst Environ 65:69–78

Jastrow JD (1996) Soil aggregate formation and the accrual of particulate and mineral-associated organic matter. Soil Biol Biochem 28:665–676

Johnson JM-F, Allmaras RR, Reicosky DC (2006) Estimating source carbon from crop residues, roots and rhizodeposits using the national grain-yield database. Agron J 98:622–636

Kaštovská E, Šantrůčková H (2007) Fate and dynamics of recently fixed C in pasture plant–soil system under field conditions. Plant Soil 300:61–69

Kirk G (2004) The biogeochemistry of submerged soils. Wiley, Chichester

Kögel-Knabner I, Amelung W, Cao ZH, Fiedler S, Frenzel P, Jahn R, Kalbitz K, Kölbl A, Schloter M (2010) Biogeochemistry of paddy soils. Geoderma 157:1–14

Kristiansen SM, Schjønning P, Thomsen IK, Olesen JE, Kristensen K, Christensen BT (2006) Similarity of differently sized macro-aggregates in arable soils of different texture. Geoderma 137:147–154

Kuzyakov Y, Domanski G (2000) Carbon input by plants into the soil (Review). J Plant Nutr Soil Sc 163:421–431

Kuzyakov Y, Gavrichkova O (2010) Time lag between photosynthesis and carbon dioxide efflux from soil: a review of mechanisms and controls. Global Change Biol 16:3386–3406

Kuzyakov Y, Ehrensberger H, Stahr K (2001) Carbon partitioning and below-ground translocation by Lolium perenne. Soil Biol Biochem 33:61–74

Li YS, Wu LH, Lu XH, Zhao LM, Fan QL, Zhang FS (2006) Soil microbial biomass as affected by non-flooded plastic mulching cultivation in rice. Biol Fert Soils 43:107–111

Li YS, Wu LH, Zhao LM, Lu XH, Fan QL, Zhang FS (2007) Influence of continuous plastic film mulching on yield, water use efficiency and soil properties of rice fields under non-flooding condition. Soil Till Res 93:370–378

Lu YH, Watanabe A, Kimura M (2002a) Contribution of plant-derived carbon to soil microbial biomass dynamics in a paddy rice microcosm. Biol Fert Soils 36:136–142

Lu YH, Watanabe A, Kimura M (2002b) Input and distribution of photosynthesized carbon in a flooded rice soil. Global Biogeochem Cy 16(4):1085. doi:10.1029/2002GB001864

Lu YH, Watanabe A, Kimura M (2004) Contribution of plant photosynthates to dissolved organic carbon in a flooded rice soil. Biogeochemistry 71:1–15

Martin JK (1975) 14C-labelled material leached from the rhizosphere of plants supplied continuously with 14CO2. Soil Biol Biochem 7:395–399

Meharg AA, Killham K (1990) Carbon distribution within the plant and rhizosphere for Lolium perenne subjected to anaerobic soil conditions. Soil Biol Biochem 22:643–647

Minamikawa K, Sakai N (2005) The effect of water management based on soil redox potential on methane emission from two kinds of paddy soils in Japan. Agr Ecosyst Environ 107:397–407

Mishra A, Salokhe VM (2011) Rice root growth and physiological responses to SRI water management and implications for crop productivity. Paddy Water Environ 9:41–52

Nguyen C (2003) Rhizodeposition of organic C by plants: mechanisms and controls. Agronomie 23:375–396

Ramasamy S, tenBerge HFM, Purushothaman S (1997) Yield formation in rice in response to drainage and nitrogen application. Field Crops Res 51:65–82

Rees RM, Bingham IJ, Baddeley JA, Watson CA (2005) The role of plants and land management in sequestering soil carbon in temperate arable and grassland ecosystems. Geoderma 128:130–154

Reid CPP (1974) Assimilation, distribution, and root exudation of 14C by ponderosa pine seedlings under induced water stress. Plant Physiol 54:44–49

Schimel J, Balser TC, Wallenstein M (2007) Microbial stress-response physiology and its implications for ecosystem function. Ecology 88:1386–1394

Staddon PL, Ostle N, Dawson LA, Fitter AH (2003) The speed of soil carbon throughput in an upland grassland is increased by liming. J Exp Bot 54:1461–1469

Swinnen J, Van Veen JA, Merckx R (1994) 14C pulse-labelling of field-grown spring wheat: An evaluation of its use in rhizosphere carbon budget estimations. Soil Biol Biochem 26:161–170

Thakur AK, Rath S, Patil DU, Kumar A (2011) Effects on rice plant morphology and physiology of water and associated management practices of the system of rice intensification and their implications for crop performance. Paddy Water Environ 9:13–24

van Hees PAW, Jones DL, Finlay R, Godbold DL, Lundström US (2005) The carbon we do not see- the impact of low molecular weight compounds on carbon dynamics and respiration in forest soils: a review. Soil Biol Biochem 37:1–13

Watanabe A, Machida N, Takahashi K, Kitamura S, Kimura M (2004) Flow of photosynthesized carbon from rice plants into the paddy soil ecosystem at different stages of rice growth. Plant Soil 258:151–160

Wu J, Brookes PC, Jenkinson DS (1996) Evidence for the use of a control in the fumigation-incubation method for measuring microbial biomass carbon in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 28:511–518

Yang JC, Zhang JH, Wang ZQ, Zhu QS, Liu LJ (2002) Abscisic acid and cytokinins in the root exudates and leaves and their relationship to senescence and remobilization of carbon reserves in rice subjected to water stress during grain filling. Planta 215:645–652

Zibilske LM (1994) Carbon mineralization. In: Weaver RW, Angle S, Bottomley P, Bezdicek D, Smith S, Tabatabai A, Wollum A (eds) Methods of soil analyses, Part 2 microbiological and biochemical properties, soil science society of America book series, vol 5. Soil Science Society America Inc., Madison, pp 835–864

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. JC Yang for his kind help about suggestion during growing the rice. We also thank the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments that helped us to greatly improve the manuscript. We thank the Major State Basic Research Development Programmer of the People’s Republic of China (Grant No. 2011CB100505), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41171195), the Innovative Group Grant of the National Science of Foundation of China (Grant No. 311210620) for generous financial support. The authors also thank China Scholarship Council for providing fund to Jing Tian to pursue her study in Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Angela Hodge.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, J., Pausch, J., Fan, M. et al. Allocation and dynamics of assimilated carbon in rice-soil system depending on water management. Plant Soil 363, 273–285 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1327-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1327-z