Abstract

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak following initiation of Dopamine agonist therapy for macroprolactinomas, although uncommon, has been described previously in the literature. Traditional management includes primary repair of the defect using either fat or fascia lata in conjunction with lumbar drain insertion. In this case series we outline two cases of CSF leak secondary to invasive pituitary tumour that were repaired successfully using a nasoseptal flap. We believe that this form of repair is effective and associated with minimal morbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak is most commonly seen after trauma (80–90%). However, other rarer causes include post trans-sphenoidal surgery (TSS) (3.7–8.42%) [1], intracranial tumours, inflammation, or spontaneous leak (3–4%) [2, 3]. CSF leaks are associated with an approximately 10% risk of developing meningitis per year [4].

CSF leak following initiation of Dopamine agonist therapy for macroprolactinomas, although uncommon, has been described previously in the literature [5, 6]. Traditional management of CSF leaks in this setting include primary repair of the defect using either fat or fascia lata in conjunction with lumbar drain insertion. The primary difficulty in dealing with tumours presenting in this way, is that the leak can often occur at multiple discrete sites following bony erosion of the sella.

Hadad and Bassagasteguy originally described the nasoseptal flap in 2006 as a method of reconstructing defects after extended endonasal skull base surgery [7]. It consists of a mucosal flap pedicled on the septal branch of the sphenopalatine artery. As far as we are aware, this method has not previously been described in the literature for repair of CSF leak secondary to invasive pituitary tumours. In this case series we outline two such cases, which were managed surgically with a nasoseptal flap.

Case reports

Case 1

A 68 year old male with a large prolactinoma presented with visual disturbance. Brain imaging (Fig. 1) demonstrated a pituitary tumour with invasion of the sella turcica. His prolactin levels were 7,469, and IGF-1 was 932. With an initial diagnosis of mixed somatomammotroph adenoma, the patient was commenced on cabergoline. His visual impairment rapidly improved but he developed CSF rhinorrhoea, which was confirmed by β2 transferrin levels. On stopping his cabergoline the CSF leak resolved but led to a return of visual compromise. He was therefore restarted on cabergoline with recurrence of rhinorrhoea. Given the need to maintain his vision, it was felt that the optimal treatment would be to debulk the tumour and formally repair the sellar defects to allow continuation of cabergoline therapy.

Case 2

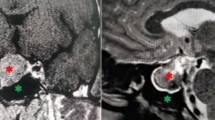

A 36 year old male originally presented with signs of acromegaly secondary to a pituitary macroadenoma. His growth hormone levels were 104 mU/l with no evidence of suppression on a glucose tolerance test and his IGF-1 level was >1,000. CT and MRI scans (Fig. 2) showed a macroadenoma based predominantly in the sphenoid sinus with parasellar extension. He was initially managed with combination therapy in the form of lanreotide, trans-sphenoidal surgery and radiotherapy. Continued use of lanreotide produced further tumour shrinkage with subsequent CSF leak. The patient initially wished to be managed conservatively but following recurrent episodes of meningitis, he consented to further surgery to repair the skull base defects using a nasoseptal flap.

Surgical procedure

Both patients underwent a similar procedure. Under general anaesthesia a lumbar drain was inserted and intrathecal fluorescein (0.125 mg mixed with 10 ml CSF) injected. The patient was then turned supine and underwent an endoscopic transnasal trans-sphenoidal approach. A right sided nasoseptal flap was harvested and pedicled on the septal branch of the sphenopalatine artery (Fig. 3a and b). The early harvesting of the flap prevents injury to the vascular pedicle during the remainder of the procedure. Bilateral anterior sphenoidotomies and a posterior septectomy were then performed to produce a large single cavity allowing identification of the sella, clivus and carotid arteries. The sites of CSF leak in the sellar region and lateral sphenoid were readily identified by fluorescein staining (Fig. 4). The tumour was then debulked and the leaks repaired by rotating the pedicled naso-septal flap over the skull base defects. The flaps were secured in position using DuraSeal™.

Results

Post-operatively the general principles were applied for managing CSF fistulae (including stool softeners, avoidance of nose blowing and sneezing with an open mouth) in order to protect the repair and aid healing [8, 9]. Additionally, the lumbar drain was left in situ draining 10–15 ml per hour for 5 days. Neither patient had any evidence of CSF leak during this period or any surgical complications. 1 year post-surgery neither patient has had any evidence of further CSF leak or any further episodes of meningitis.

Discussion

CSF rhinorrhoea in patients with invasive pituitary tumours, secondary to tumour shrinkage after initiation of medical management, is a rare presentation [5, 6]. The surgical management can be difficult, mainly because there are often multiple defects from which CSF leaks. Whilst the cause of CSF leak in these cases is different to the usual post-operative CSF leak, the aims and principles of repair remain the same—to form a watertight dural seal and establish a barrier between the sterile cranial cavity and the contaminated sino-nasal tract, thus decreasing the risk of ascending bacterial meningitis. This normally involves multi-layering of tissue, but recent work by Carvallo et al. [10] suggests that such repair can best be accomplished using a single extradural overlay/onlay technique.

The main area of discussion in repairing these defects remains the choice of material used to accomplish the repair. Classically, surgeons have used muscle, fat or fascia lata with support for the graft from nasal bone/nasal cartilage [11]. Whilst these grafts have been successful, problems arise due to the requirement of an additional surgical incision (thereby increasing the rate of local complication at that site) and post-operative CSF leak despite grafting. The development of a variety of substitute tissue has led more recently to heterologous grafting [10, 12–17]. There are various advantages and disadvantages described for these materials, including the adjunctive cost, lack of material pliability and imaging artefact.

In our two patients we utilised naso-septal mucosal flaps based on the septal artery, a branch of the sphenopalatine artery. We were able to successfully repair spontaneous CSF leaks occurring secondary to pituitary tumours using this technique, an application not previously described in the literature.

Several benefits can be seen using this technique:

-

The flap allows blanket coverage of a large area, where CSF is leaking at multiple sites. This is obviously an advantage in these cases over techniques such as primary dural suturing described recently by Nishioka [18] where there would be much more difficulty in repairing multiple areas.

-

The vascularity provided by the preserved pedicle allows rapid and effective integration with the surrounding tissue. The prolonged time required for tissue integration and risks of tissue resorption when using non-vascularised flaps can lead to a delayed post-operative CSF leak.

-

The lack of expense and relative simplicity of the technique are also clear advantages. In cases where the Hadad-Bassagasteguy Flap cannot be utilised, the posterior pedicle inferior turbinate flap (PPITF) described by Fortes et al., may provide similar advantages [19].

Although groups with a significant experience of endoscopic skull base surgery or otorhinolaryngology may be well aware of this technique, it will not be familiar to most pituitary surgeons. With the increasing trend of endoscopic surgery, pituitary surgeons are using a more direct route to the sphenoid sinus thus preserving the septal mucosa. We believe that raising a pedicled vascular nasoseptal flap is a relatively straightforward procedure that surgeons new to endoscopic surgery can perform. The successful use in these two complex cases highlights the advantage of using a pedicled flap over traditional free grafts.

Lumbar drains are often used as an adjunct to traditional methods of repair. However, the risks associated with their use include CSF infection, epidural abscess, haematoma and pneumocephalus from overdrainage. Even without complications, the overall length of stay is usually increased. In our experience patients with a post-operative CSF leak managed with a fat/fascia lata graft and lumbar drainage had an average post-operative length of stay of 11.8 days (range 7–30 days) compared with 5.54 days (range 2–22 days) in those managed with a nasoseptal flap. With our increasing experience using the nasoseptal flap for all cases complicated by CSF leak, we no longer find the need to use lumbar drains, with a subsequent decrease in both morbidity and length of stay.

Conclusion

We believe that endonasal endoscopic repair of CSF leaks secondary to invasive pituitary tumours using a pedicled nasoseptal flap is a simple and effective method and is associated with minimal morbidity.

References

Tamasauskas A, Sinkūnas K, Draf W, Deltuva V, Matukevicius A, Rastenyte D, Vaitkus S (2008) Management of cerebrospinal fluid leak after surgical removal of pituitary adenomas. Medicina (Kaunas) 44(4):302–307

Abuabara A (2007) Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea: diagnosis, management. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 12(5):E397–E400

Honegger JB, Psaras T, Petrick M, Beuschlein F, Reincke M (2006) Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea in untreated macroprolactinoma–an indication for primary surgical therapy. Zentralbl Neurochir 67(3):149–154

Jones NS, Becker DG (2001) Advances in the management of CSF leaks. BMJ 322:122–123

Baskin DS, Wilson CB (1982) CSF rhinorrhea after bromocriptine for prolactinoma. N Engl J Med 306(3):178

Cappabianca P, Lodrini S, Felisati G, Peca C, Cozzi R, Di SA et al (2001) Cabergoline-induced CSF rhinorrhea in patients with macroprolactinoma. Report of three cases. J Endocrinol Invest 24(3):183–187

Hadad G, Bassagasteguy L, Carrau RL, Mataza JC, Kassam A, Snyderman CH, Mintz A (2006) A novel reconstructive technique after endoscopic expanded endonasal approaches: vascular pedicle nasoseptal flap. Laryngoscope 116(10):1882–1886

Zweig JL, Carrau RL, Celin SE, Schaitkin BM, Pollice PA, Snyderman CH, Kassam A, Hegazy H (2000) Endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid leaks to the sinonasal tract: predictors of success. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 123(3):195–201

Hegazy HM, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, Kassam A, Zweig J (2000) Transnasal endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: a meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 110(7):1166–1172

Cavallo LM, Messina A, Esposito F, de Divitiis O, Dal Fabbro M, de Divitiis E, Cappabianca P (2007) Skull base reconstruction in the extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for suprasellar lesions. Neurosurg 107(4):713–720

Hardy J (1971) Transsphenoidal hypophysectomy. J Neurosurg 34(4):582–594

Sherman JH, Pouratian N, Okonkwo DO, Jane JA Jr, Laws ER (2008) Reconstruction of the sellar dura in transsphenoidal surgery using an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene dural substitute. Surg Neurol 69(1):73–76, discussion 76

Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM, Esposito F, Valente V, De Divitiis E (2002) Sellar repair in endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery: results of 170 cases. Neurosurgery 51(6):1365–1371

Esposito F, Dusick JR, Fatemi N, Kelly DF (2007) Graded repair of cranial base defects and cerebrospinal fluid leaks in transsphenoidal surgery. Neurosurgery 60(4 Suppl 2):295–303; discussion 303–4

Kelly DF, Oskouian RJ, Fineman I (2001) Collagen sponge repair of small cerebrospinal fluid leaks obviates tissue grafts and cerebrospinal fluid diversion after pituitary surgery. Neurosurgery 49(4):885–889

Nishioka H, Haraoka J, Ikeda Y (2005) Risk factors of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea following transsphenoidal surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 147(11):1163–1166

Seiler RW, Mariani L (2000) Sellar reconstruction with resorbable vicryl patches, gelatin foam, and fibrin glue in transsphenoidal surgery: a 10-year experience with 376 patients. J Neurosurg 93(5):762–765

Nishioka H, Izawa H, Ikeda Y, Namatame H, Fukami S, Haraoka J (2009) Dural suturing for repair of cerebrospinal fluid leak in transnasal transsphenoidal surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 151(11):1427–1430

Fortes FS, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, Prevedello D, Vescan A, Mintz A, Gardner P, Kassam AB (2007) The posterior pedicle inferior turbinate flap: a new vascularized flap for skull base reconstruction. Laryngoscope 117(8):1329–1332

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thakur, B., Jesurasa, A.R., Ross, R. et al. Transnasal trans-sphenoidal endoscopic repair of CSF leak secondary to invasive pituitary tumours using a nasoseptal flap. Pituitary 14, 163–167 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-010-0274-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-010-0274-z