Abstract

How does it happen that our beliefs about what we ought to do cause us to intend to do what we believe we ought to do? This is what John Broome calls the “motivation question.” Broome’s answer to the motivation question is that we can bring ourselves, by our own efforts, to intend to do what we believe we ought to do by exercising a special agential capacity: the capacity to engage in what he calls “enkratic reasoning.” My aim is to evaluate this answer. In doing so, I shall focus on three core aspects of Broome’s overall account: his account of ought, his account of enkratic rationality, and his account of enkratic reasoning in particular. In each case I suggest there are problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

John Broome’s stated aim in Rationality Through Reasoning (Broome 2013: henceforth RTR) is to answer what he calls “the motivation question.” The motivation question is: How does it happen, as it surely often does, that “[w]hen you believe you ought to do something, your belief … causes you to intend to do what you believe you ought to do”? (RTR, p. 1).Footnote 1

One kind of answer to the motivation question that Broome mentions in order to set aside is that we are simply disposed—more or less automatically—to intend to do what we believe we ought to do. Broome is not satisfied with this answer. He takes it to be crucially incomplete. What is lacking is the special way in which we manifest our agency in bringing it about that we intend to do what we believe we ought to do. He writes, “We should expect that people by their own efforts can actually bring themselves to intend to do what they believe they ought to do” (RTR, p. 2: italics added).

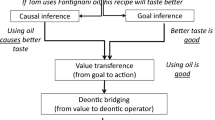

Broome therefore offers a different answer to the motivation question. There is a requirement of rationality—what he calls “Enkrasia”—which holds, very roughly, that “Rationality requires of you that, if you believe you ought to F, then you intend to F” (RTR, p. 22). While, to be sure, we may and often do come to satisfy requirements of rationality more or less automatically, we also have a special way of doing so that engages our agency, namely reasoning. Moreover, one kind of correct reasoning—enkratic reasoning—involves precisely reasoning from beliefs about what we ought to do to intentions to do the thing we believe we ought to do. So Broome’s answer to the motivation question is this: We can bring ourselves, by our own efforts, to intend to do what we believe we ought to do by exercising a special agential capacity: the capacity to engage in enkratic reasoning.

My aim in what follows is to evaluate Broome’s answer to the motivation question. In doing so I shall focus on three core aspects of Broome’s overall account: his account of ought (Sect. 2), his account of enkratic rationality (Sect. 3), and his account of enkratic reasoning (Sect. 4). This is obviously not the place to undertake anything like a comprehensive evaluation of these accounts as such. Rather, my concern is principally with their adequacy as constituents of Broome’s answer to the motivation question. In each case I shall suggest that there are non-trivial difficulties to be overcome.

2 Ought

Let’s start with Broome’s account of ought. Broome recognizes that, in order to offer a satisfactory answer to the motivation question, he needs to say something about the meaning of the “ought” that figures in it. That’s because only a certain class of oughts is such that our beliefs involving oughts within that class raise the motivation question.Footnote 2 The members of this class involve what Broome calls “the central ought.” He does not try to define the meaning of the central ought. But he does give us a “test” or “criterion” for identifying it: it is “the ought that Enkrasia applies to” (RTR, p. 24).Footnote 3 For any putative ought, we may ask whether the agent would necessarily be irrational—in particular, whether she would necessarily be akratic—if she were to believe that she ought (in that sense) to do something and yet fail to intend to do it. The ought in question is the central ought (if and) only if the answer is yes. If the answer is no—if an agent wouldn’t necessarily be irrational if she were to believe that she ought (in that sense) to do something and yet fail to intend to do it—then it follows that the ought in question is not the central ought.

Let’s not quibble about whether the class of oughts that is picked out by Broome’s test is the central (or perhaps a central) ought. It is clearly important.Footnote 4 The more pertinent question for our purposes is whether Broome’s test constitutes a plausible test for identifying the class of oughts that is at issue in the motivation question. In certain respects it fares impeccably. For one, it implies that the only oughts that are at issue in the motivation question are “normative,” rather than “non-normative” (RTR, pp. 9–12). Take the predictive ought. Clearly, Enkrasia does not apply to the predictive ought. For example, there need be nothing irrational about my believing that I ought in the predictive sense to be finished reading my student’s paper by 2 o’clock and yet not intending to do so. So Broome’s test implies that the motivation question does not encompass the predictive ought. This is clearly the right result. For another, Broome’s test implies that the only oughts that are at issue in the motivation question are oughts that are “owned” by the agent (RTF, pp. 12–25). Enkrasia does not apply to the “unowned” ought, or to oughts that are “owned” by some other agent. For example, there need be nothing irrational about my believing that John ought that I eat a mangosteen without my intending to eat a mangosteen. Broome’s test implies that the motivation question does not encompass such oughts. Again, this is clearly the right result.

But Broome’s test has other implications that, to my mind, are less appealing. The problem that I shall focus on here is that it is too restrictive. The class of oughts picked out by Broome’s test is unduly narrow. It excludes certain normative beliefs that seem to raise the motivation question (or at least something sufficiently like it that it would seem reasonable to want an answer to the motivation question to have application to these other ought beliefs too). I shall focus on moral beliefs in particular.

Broome takes moral beliefs to be an example of beliefs involving what he calls “qualified” as opposed to “unqualified” (or all-things-considered) oughts. It is possible to believe that one morally ought to do something without believing that one ought unqualifiedly to do it: say, because one believes that there are non-moral considerations that outweigh the moral considerations; or because one simply doesn’t have any belief one way or the other about what one ought unqualifiedly to do. To be sure, this is not an uncontroversial view of morality. Many philosophers influenced by Kant hold instead that the moral ought is (or entails) the unqualified ought (see Stroud 1998). But I shall suppose that Broome is right and those who insist that the moral ought entails the unqualified ought are wrong.

Our moral beliefs (no less than our beliefs about what we unqualifiedly ought to do) often cause us to form corresponding intentions. Doubtless this is sometimes because our moral beliefs cause us to form beliefs about what we unqualifiedly ought to do, which then in turn cause us to intend to do what we believe we ought unqualifiedly to do. But in other cases I take it that our moral beliefs cause us to intend to do what we believe we morally ought to do without this intermediate step. Suppose that I see that a fellow surfer has been knocked unconscious in heavy swell and form the belief that I morally ought to save her. Suppose, moreover, that while I have beliefs whose truth entails that I ought unqualifiedly to save her, I do not, as a matter of fact, form any belief about what I ought unqualifiedly to do. Such a belief might very well cause me to intend to save her.

It seems to me that we have reason to want an answer to the motivation question to be able to explain how such moral beliefs that are not accompanied by beliefs about what we ought unqualifiedly to do cause us to intend to do what we believe we morally ought to do. To put it another way, there must be such an explanation; and it would be very surprising if the explanation were markedly different from the explanation of how beliefs about what ought unqualifiedly to do cause us to intend to do what we believe we unqualifiedly ought to do. The problem is that Broome’s test implies that moral beliefs that are not accompanied by beliefs about what we ought unqualifiedly to do are straightforwardly excluded. That’s because, as Broome persuasively argues, Enkrasia does not apply to qualified oughts. I needn’t be irrational—or at least I needn’t be akratic—in believing that I morally ought to save the drowning surfer without intending to save her—insofar as I don’t believe that I unqualifiedly ought to save her.

What might Broome say in response? He might insist that (a) even if moral beliefs that are unaccompanied by beliefs about what we unqualifiedly ought to do sometimes cause us to intend to do what we believe we morally ought to do, this will inevitably involve irrationality and that (b) he is only interested in a certain kind of answer to the motivation question: one that appeals to mental processes that do not require us to be irrational.

Is it true that the relevant processes by which moral beliefs that are unaccompanied by beliefs about what we unqualifiedly ought cause us to form corresponding intentions necessarily involve irrationality? They would seem to do so only insofar as they involve violating what Broome calls a “basing prohibition of rationality” (RTR, p. 141, 186–191). Basing prohibitions require us not to base some attitude(s) on some (other) attitude(s). The basing prohibition that Broome needs, roughly stated, would be as follows:

Moral Belief Prohibition: Rationality requires of N that N does not intend to F on the basis of believing that she morally ought to F, where it is not the case that N believes that she ought (unqualifiedly) to F.

I see no reason to think that there is any such valid basing prohibition. To be sure, there are some situations where it seems rationally impermissible to intend to do something on the basis of believing that one morally ought to do it. Perhaps the clearest cases are situations where one believes that it is not the case that one ought unqualifiedly to do it. This suggests the following basing prohibition:

Moral Belief Prohibition*: Rationality requires of N that N does not intend to F on the basis of believing that she morally ought to F, where N believes that it is not the case that she ought (unqualifiedly) to F.

Another class of situations where we might think that it is rationally impermissible to intend to do something on the basis of believing that one morally ought to do it are situations where one lacks beliefs whose truth entails that one ought unqualifiedly to do it. This suggests another basing prohibition:

Moral Belief Prohibition**: Rationality requires of N that N does not intend to F on the basis of believing that she morally ought to F, where N lacks beliefs whose truth entails that she ought (unqualifiedly) to F.

Let’s assume that Moral Belief Prohibition* and Moral Belief Prohibition** are valid. The problem, of course, is that one needn’t violate Moral Belief Prohibition* or Moral Belief Prohibition** in forming intentions on the basis of moral beliefs. Consider again the case where I form the intention to save the fellow surfer on the basis of believing that I morally ought to save her, but where (a) I simply lack a belief about what I ought unqualifiedly to do and (b) I have other beliefs whose truth entails that I ought unqualifiedly to save her. In this case, I do not violate Moral Belief Prohibition* or Moral Belief Prohibition**. Of course, I do violate Moral Belief Prohibition. But, as I have said, I see no reason to accept Moral Belief Prohibition. If Moral Belief Prohibition strikes you as initially plausible, I submit that this is because you are confusing it with Moral Belief Prohibition* or Moral Belief Prohibition**.

3 Enkratic rationality

Next, let us turn to Broome’s account of enkratic rationality. I shall focus here, in particular, on the principle that Broome calls “Enkratic Permission.” This holds that

Enkratic Permission: Rationality permits N that

N believes at some time that she herself ought that p, and

N believes at some time that it is up to her herself whether or not p, and

N intends at some time that p, and

N’s intention that p is based on N’s belief that she herself ought that p and belief that it is up to herself whether or not p (TRT, p. 290).

Enkratic Permission is an example of what Broome calls a “basing permission” of rationality. Basing permissions permit us to form some attitude(s) on the basis of some (other) attitude(s) (RTF, p. 190). Enkratic Permission plays a crucial role in Broome’s answer to the motivation question. Broome is looking for a rationally permissible way in which our normative beliefs cause us to intend to do what we believe we ought to do. Enkratic Permission is supposed to explain why this is rationally permissible. Moreover, Broome is trying to show how our normative beliefs cause us to intend to do what we believe we ought to do by way of correct reasoning. According to Broome, “a correct rule [of reasoning] is one that corresponds to a [valid] basing permission of rationality” (RTR, p. 255). Enkratic Permission is supposed to explain why (and when) reasoning from a normative belief to an intention is correct reasoning.Footnote 5

I see two main problems with Enkratic Permission. The first problem is that it means that Broome’s answer to the motivation question is inappropriately and unnecessarily restrictive. I shall focus in particular on the “up to me myself” clauses. The presence of the clauses makes Broome’s answer to the motivation question inappropriately restrictive inasmuch as the motivation question often seems to arise in cases where these clauses are not satisfied. It makes Broome’s answer to the motivation question unnecessarily restrictive inasmuch as less restrictive principles that lack the clauses still appear to be valid.

Broome does consider a less restrictive alternative to Enkratic Permission that lacks the “up to me myself” clauses. Let’s call it Enkratic Permission*:

Enkratic Permission*: Rationality permits N that

N believes at some time that she herself ought that p, and

N intends at some time that p, and

N’s intention that p is based on N’s belief that she herself ought that p (TRT, p. 290).

Broome offers an argument against Enkratic Permission*. Enkratic Permission* is

not a genuine permission. Suppose, say, that you believe you ought to know the President’s name. But suppose you believe it is not up to you (in the [relevant] sense…) whether or not you know the President’s name because you already know it. Intending to know it will make no difference one way or the other. Then you could not rationally base an intention to know the President’s name on your belief that you ought to know it (RTR, p. 290).

Let’s concede that this argument succeeds in refuting Enkratic Permission*. This does not mean, however, that some other principle that is less restrictive than Enkratic Permission (but more restrictive than Enkratic Permission*) couldn’t be correct. Here is one candidate:

Enkratic Permission**: So long as N believes that it is up to her herself whether or not p, rationality permits N that

N believes at some time that she herself ought that p, and

N intends at some time that p, and

N’s intention that p is based on N’s belief that she herself ought that p (TRT, p. 290).

Enkratic Permission** is like Enkratic Permission (and unlike Enkratic Permission*) in the sense that having a belief that it is up to one oneself whether p is necessary in order to be rationally permitted to base an intention on a normative belief. The difference between Enkratic Permission** and Enkratic Permission is that the belief that it is up to the agent herself whether or not p is, as it were, a background condition for the rational permissibility of forming intentions on the basis of normative beliefs, rather than part of the basis itself. Suppose that (a) I believe that I ought to buy a nice anniversary present for Marie-Charlotte (my wife), (b) I believe that it is up to me myself whether or not I buy a nice anniversary present for her, (c) I form the intention to buy Marie-Charlotte a nice anniversary present, (d) my intention to buy Marie-Charlotte a nice anniversary present is based on my belief that I ought to buy her a nice anniversary present, but (e) my intention it is not based on my belief that it is up to me myself whether or not I buy a nice anniversary present for her. Broome does not provide any argument for why this is irrational.

I am inclined to think that Enkratic Permission** is still too restrictive. Suppose that (a) I believe that I ought to buy a nice anniversary present for Marie-Charlotte, (b) I intend to do so, (c) my intention is based on my normative belief, but that (d) I simply lack one or other of the counterfactual beliefs required in order to believe that it is up to me myself whether or not I do so. Thus, either I lack the belief that if I myself were to intend to buy a nice anniversary present for Marie-Charlotte, because of that, I would buy a nice anniversary present for Marie-Charlotte. Or I lack the belief that if I myself were not to intend to buy a nice anniversary present for Marie-Charlotte, then because of that, it would not be the case that I will buy a nice anniversary present for Marie-Charlotte. Or both. While I do not satisfy Enkratic Permission**, here is a less restrictive permission that I do satisfy:

Enkratic Permission***: So long as N does not believe that it is not up to her herself whether or not p, rationality permits N that

N believes at some time that she herself ought that p, and

N intends at some time that p, and

N’s intention that p is based on N’s belief that she herself ought that p (TRT, p. 290).

Again, so far as I can tell, Broome does not offer any argument against Enkratic Permission***. His argument against Enkratic Permission* involved an agent who believes that it is not up to her herself whether p. But Enkratic Permission*** makes it a condition for the rational permissibility of forming intentions on the basis of normative beliefs that it is not the case that the agent believes that it is not up to her herself whether p.

I have been arguing that Enkratic Permission is unduly restrictive and suggested some friendly amendments.Footnote 6 I shall now present a second objection that, unfortunately, cuts more deeply. This holds that we have reason to reject any enkratic basing permission. Before doing so, however, I need to say something about when basing is rationally permissible. Here is what I take to be a plausible necessary condition for when some attitude(s) A is rationally based on some attitude(s) B: it would be apt for the agent to adduce the (marked) content of attitudes B to answer a certain kind of “why question” concerning (the (marked) content of) attitudes A (cf Anscombe 1957; Hieronymi 2009). Aptness is not a matter of correctness. An apt answer to a why question might involve an error: say, because the content of attitudes B is incorrect. Rather, I take it that aptness is a matter of whether the content of attitudes B, if correct, bears positively on the correctness of attitudes A.

Suppose that my false belief that the liquid in the glass that I am about to drink is H3O is based on my belief that the liquid in the glass is water and my belief that water is H3O. This seems to pass our test. It would seem apt, in response to the question, “But why do you think that the liquid in your glass H3O?”, to answer, “Because the liquid in the glass is water and water is H3O.” While the answer involves an error, it seems apt. That’s because assuming that it is correct that the liquid in the glass is water and water is H3O, then these considerations do indeed seem to bear positively on the correctness of my belief that the liquid in the glass being H3O.

Or suppose that my intention to travel to Ecuador is based on my intention to travel to Caracas and my false belief that I can only travel to Caracas if I travel to Ecuador (because I mistakenly believe Caracas to be in Ecuador). Again, this seems to pass our test. For it would seem apt to answer the question, “Why are you travelling to Ecuador?” by responding, “Because I’m travelling to Caracas and I can only travel to Caracas if I travel to Ecuador.” My answer involves an error. But it nonetheless seems apt, since, assuming that it is correct that I’m travelling to Caracas and can only travel to Caracas if I travel to Ecuador, these considerations do indeed seem to bear positively on the correctness of my intention to travel to Ecuador.

Now consider Enkratic Permission. Suppose that I intend to send a paper to Analysis and my intention is based on my belief that I ought to send it to Analysis and my belief that it is up to me myself whether or not I do so. Does this pass our test? Suppose that in response to the question, “Why are you going to send your paper to Analysis?” I respond, “Because I ought to send my paper to Analysis and it is up to me myself whether I do so?” This does not seem apt. The reason why it does not seem apt is that even if it is true that I ought to send my paper to Analysis and that it is up to me myself whether or not I do so, these considerations do not seem to bear positively on the correctness of my intention to send my paper to Analysis. Rather, the sorts of considerations that would seem to be relevant are the considerations that would, if true, help to explain why I ought to send my paper to Analysis: that it’s a good journal; that the paper engages with another paper published there; and so on. So, Enkratic Permission permits basing that fails our test. Moreover, it seems to me that any kind of enkratic basing permission will also permit basing that fails our test. If it is a good test, then this means that no enkratic basing permission is valid.

Does this mean that no basing permission involving normative beliefs is valid? Not necessarily. First, consider basing permissions involving moral beliefs. Here is an example of such a basing permission:

Moral Belief Permission: So long as a) it is not the case that N believes that it is not the case that she herself ought (unqualifiedly) that p and b) N has beliefs whose truth entails that N ought unqualifiedly that p, rationality permits N that

N believes at some time that she herself morally ought that p, and

N believes at some time that it is up to her herself whether or not p, and

N intends at some time that p, and

N’s intention that p is based on N’s belief that she herself morally ought that p and belief that it is up to herself whether or not p.

Interestingly, Moral Belief Permission appears to pass our test. Suppose that I intend to save the drowning surfer on the basis of believing that I am morally required to save her and believing that it is up to me myself whether or not I save her. Suppose that someone asks me, “Why are you going to save her?” It would seem perfectly apt to respond, “Because I am morally required to do so.” To be sure, it would also be apt to respond by citing the kinds of considerations that might potentially ground the moral requirement: “Because otherwise she will die.” “Because her children will be grief-stricken beyond belief if I don’t save her.” And so on. But this does not mean that it would be inapt to cite the moral requirement itself.Footnote 7 Moral requirements and unqualified oughts seem different in this respect: Whereas it seems a mistake to adduce an unqualified ought as bearing positively on the correctness of an intention to act, it does not seem to be a mistake to adduce a moral requirement.

Second, consider a non-enkratic basing permission in which a normative belief is figuring in the background. Here is an example:

Non-Enkratic Permission: So long as a) N believes that she herself ought that p, b) N believes that it is up to her herself whether p, and c) N believes that because of q then she herself ought that p, rationality permits N that

N believes at some time that q, and

N intends that p, and

N’s intention that p is based on N’s belief that q.

Again, Non-Enkratic Permission appears to pass our test. Suppose that while I do indeed believe that I ought to send my paper to Analysis, that it is up to me myself whether I do so, and that I ought to send it to Analysis because the paper is well-suited to Analysis, I intend to send my paper to Analysis simply on the basis of believing that the paper is well-suited to Analysis. Suppose that someone asks me, “Why are you going to send your paper to Analysis?” It would seem perfectly apt to respond, “Because the paper is well-suited to Analysis.” So Non-Enkratic Permission, unlike Enkratic Permission, passes our test.

4 Enkratic reasoning

Let us now turn directly to Broome’s account of enkratic reasoning. We have already been engaging with Broome’s account of enkratic reasoning indirectly. In particular, if the argument of the preceding section was correct, then it follows that enkratic reasoning is not correct reasoning. That’s because reasoning is correct only if it corresponds to a valid basing permission of rationality, and I argued that the basing permission that Broome adduces to validate the correctness of enkratic reasoning—Enkratic Permission—is invalid. Since Broome’s answer to the motivation question is supposed to explain how our normative beliefs cause us to intend to do what we believe we ought to do by our engaging in correct reasoning, it follows that his answer to the motivation question is unsuccessful in its own terms. I shall now raise two further objections to Broome’s account of enkratic reasoning.

The first objection concerns whether, in fact, Broome succeeds in explaining the special agency-involving way in which our normative beliefs are supposed to cause us to intend to do what we believe we ought to do. Broome holds that reasoning involves an agent following a certain kind of rule that enjoins the agent to derive the marked content of an attitude from the marked contents of some other attitudes.Footnote 8 According to Broome, this is enough to explain why reasoning our way to an attitude involves our agency. Here is Broome’s explanation:

When you reason your way to a new [attitude], your reasoning is an act. Since the reasoning is an act, and is the forming of a[n attitude], the forming of the [attitude] in this way is an act. … Reasoning is an act because in reasoning you follow a rule. The rule does not merely cause you to behave in a certain way, as a program does to a computer. The rule guides and you actively follow it (RTR, pp. 236, 237).

In the case of enkratic reasoning, we follow the following rule:

Enkratic Rule: From

<I ought that p; belief> and

<It is up to me whether or not p; belief>

derive

<p; intention> (RTR, p. 290).

So, Enkratic reasoning satisfies Broome’s sufficient condition for reasoning. So, enkratically reasoning our way to an intention also involves us exercising our agency.

The problem is that there seem to be ways of satisfying Broome’s sufficient condition for enkratic reasoning that do not involve manifesting our agency in the right way. Consider a peculiar game that one might play. The game involves (a) opening at random a page from a book that lists all the things that, or so one believes, one ought to do and are such that it is up to one oneself whether or not one does them, (b) identifying the first normative claim that catches one’s eye, and then (c) forming an intention by following the enkratic rule. Suppose, then, that I open the book and the first normative claim that catches my eye is the claim that I ought to spend next weekend finishing the manuscript of my book. I then successfully follow the enkratic rule, coming to form an intention to spend next weekend finishing the manuscript of my book on the basis of believing that I ought to and believing that it is up to me myself whether I do so.

It would seem to be the case that I satisfy Broome’s sufficient conditions for enkratic reasoning. But I do not manifest agency in the right way. The special way in which we manifest agency in forming intentions is in the service of responding to specific choice situations. Receiving an overture from an estranged brother, one faces the choice of whether to accept the overture and responds by making a decision one way or the other: to accept or not to accept the overture. Having forgotten to buy basil from the supermarket before closing time, one faces the choice of whether to use arugula instead in one’s Caprese and responds by making a decision: to use arugula or not to use arugula. We manifest our agency in this special way by forming intentions in response to such specific choice situations. But this is not what happens in our peculiar game. There is no specific choice situation—say, whether to spend the weekend finishing my manuscript, or how to spend the weekend—to which my intention to spend the weekend working on my manuscript is a response. To be sure, there are various choice situations that I face: whether to play the enkratic game; whether to perform whichever act (or form whichever intention) happens to correspond to the normative claim that first catches my eye; whether to follow the enkratic rule. And, plausibly there are various intentions that I form in response to these various choice situations. So, plausibly I do manifest the right kind of agency at various points. But I don’t manifest the right kind of agency in forming the intention to spend the weekend working on my manuscript.

So, the conditions that Broome takes to be sufficient for enkratic reasoning are not sufficient for vindicating the special agency-involving way in which our normative beliefs are supposed to cause us to intend to do what we believe we ought to do.Footnote 9 That said, it also seems to me that there is a relatively easy fix. This is to add an extra necessary condition: either a necessary condition for reasoning as such (in which case the conditions that Broome takes to be sufficient for reasoning are not sufficient); or a necessary condition for a special kind of reasoning (in which case we needn’t deny that the conditions that Broome takes to be sufficient for reasoning as such are sufficient). The necessary condition I have in mind involves a special aim. According to Broome, the only aim we need to postulate is the aim of forming relevant attitudes by following relevant rules. By contrast, I suggest that there must be some further aim, and that we follow relevant rules in pursuit of this further aim.

What is this further aim? The view that I like holds that the aim of (the special kind of) reasoning is to settle some relatively specific question (Hieronymi 2009; Southwood 2016, forthcoming). The aim of (the special kind of) theoretical reasoning is to settle the question of whether p (for some specific p). The aim of (the special kind of) practical reasoning is to settle the question of whether to F (for some specific F). Notice that an account of this kind is not vulnerable to our objection involving the enkratic game. For although I form the intention to spend the weekend working on my manuscript by following the enkratic rule, I do not form the intention in pursuit of the aim of settling the question of whether to perform some act: say, whether to spend the weekend working on my manuscript. So, it follows that I am not engaged in (the special kind of) practical reasoning. Moreover, suppose that I am engaged in (the special kind of) practical reasoning. For example, suppose that I am trying to settle the question of whether to spend the weekend finishing my manuscript and I engage in some enkratic reasoning that results in my forming the intention to spend the weekend finishing my manuscript by following the enkratic rule. This does appear to involve manifesting my agency in the right way.

Let me turn to a second objection. This concerns the prevalence of enkratic reasoning. It is clearly important for Broome that enkratic reasoning is prevalent among ordinary agents. That’s because he is assuming the prevalence of the phenomenon whereby the normative beliefs of ordinary subjects cause them to intend to do what they believe they ought to do. I shall now argue that there is reason to be skeptical about the prevalence of enkratic reasoning. Given a certain plausible necessary condition for reasoning, enkratic reasoning is, at best, rare and atypical.

What is this necessary condition? Many philosophers hold that reasoning requires treating certain considerations as reasons for a relevant response (cf Korsgaard 2009; Scanlon 2007). Thus, for example, modus ponens reasoning involves treating the (marked) contents of one’s belief that p and one’s belief that if p then q as reasons for believing that q. Broome rejects such accounts (see RTR, esp. ch. 12). I think he is right to do so. While such accounts have some plausibility in the case of theoretical reasoning (such as modus ponens reasoning), they have little plausibility whatsoever in the case of practical reasoning. Take instrumental reasoning. Instrumental reasoning seems to be genuine reasoning. For example, it seems possible for me to engage in genuine reasoning from the marked contents of an intention to murder a rival for a job and a belief that I can only murder her if I put arsenic in her coffee to an intention to put arsenic in her coffee. The view that reasoning requires treating certain considerations as reasons for a relevant response implies that instrumental reasoning of this kind involves a serious error. That’s because it implies that I am thereby treating as reasons considerations that clearly are not reasons for me to intend to put arsenic in her coffee. To insist otherwise would be to invite the charge of objectionable bootstrapping (see RTR, p. 82; Kolodny 2005). It is hard to see how I could make such an elementary error. Or, at least, it seems hard to see how I could continue to make the error once I have seen it for what it is. Yet I do, in effect, continue to engage in instrumental reasoning.

Nonetheless, I do believe that something in the ballpark of the reasons account must be right. While reasoning needn’t involve treating certain considerations as reasons for a relevant response, I take it to be an important feature of reasoning that we thereby treat certain considerations as bearing positively on relevant responses. For example, modus ponens reasoning involves treating the (marked) contents of one’s belief that p and one’s belief that if p then q as bearing positively on the question of whether q. Instrumental reasoning involves treating the (marked) contents of one’s intention to F and one’s belief that one can only F by Ging as bearing positively on the question of whether to G. I won’t try to say what it means to treat a consideration as bearing positively on a response, but here is a rough test: The agent will typically be disposed, under suitably favorable conditions, to adduce the consideration in response to a certain kind of “why question?” For example, in response to the question, “Why do you think that the liquid in the glass is H3O?”, an agent who treats the (marked) contents of her belief that the liquid in the glass is water and her belief that if the liquid in the glass is water then the liquid in the glass is H3O as bearing positively on the question of whether the liquid in the glass is H3O will typically be disposed to respond, “Because the liquid in the glass is water and water is H3O.” Again, in response to the question, “Why are you travelling to Ecuador?”, an agent who treats the (marked) contents of her intention to travel to Ecuador and her belief that she can only travel to Caracas if she travels to Ecuador as bearing positively on the question of whether to travel to Ecuador will typically be disposed respond, “Because I’m travelling to Caracas and I can only travel to Caracas if I travel to Ecuador.”Footnote 10

Is this view compatible with Broome’s account of reasoning? I’m not sure. It turns on what it takes to “derive” the marked contents of attitude(s) A from the marked contents of attitude(s) B. One possibility is that it is possible to derive the marked contents of A from the marked contents of B without treating the marked contents of A as bearing positively in favor of B. In that case, I suggest that Broome has not given us sufficient conditions for reasoning. The more interesting possibility is that deriving the marked contents of A from the marked contents of B does imply treating the marked contents of A as bearing positively in favor of B. In that case, enkratic reasoning would satisfy our necessary condition. The problem is that it is hard to see how we ever engage in it. For it would be quite bizarre to treat the marked contents of the belief that I ought to perform some act and the belief that it is up to me myself whether I perform the act as bearing positively on the question of whether to perform the act. Suppose that someone asks me, “Why are you going to send your paper to Analysis?” And suppose I respond, “Because I ought to send it to Analysis and it is up to me myself whether I send it to Analysis.” Not only would such a response seem to involve an error (see above, Sect. 3). We often make errors in reasoning. For example, we often commit quantification errors. We often reason using questionable rules of instrumental reasoning: say, rules that enjoin us to derive the marked content of an intention to G from an intention to F and a belief that I can F by Ging. But the error that I would commit in engaging in enkratic reasoning is of a some different kind: it is blatant and bizarre—to the point where it is hard to imagine my responding that way. Perhaps I do, as a matter of fact, believe that I ought to send my paper to Analysis. Even if I do, we would expect me to respond by, say, adducing considerations that I take to ground the claim that I ought to send my paper to Analysis. Thus, I might respond by saying, “Because the paper is very short,” or “Because Analysis has published other papers on the topic,” or whatever. But it seems highly doubtful that I would be disposed to respond by citing the (marked) content of my normative belief.

What is the upshot? Some philosophers, influenced by Hume, have suggested that enkratic reasoning is impossible (see e.g. Williams 1981). I haven’t argued that. Nor can I see any good argument for it. But I do claim that enkratic reasoning is going to be rare and atypical. This is bad news for Broome’s answer to the motivation question. For it is not supposed to be rare and atypical that we bring ourselves by reasoning to intend to do what we believe we ought to do.

Could there be some non-enkratic mode of practical reasoning by which we bring ourselves to intend to do what we believe we ought to do? Our earlier discussion suggests two possibilities. The first involves deriving the marked content of an intention from the marked content of some non-normative beliefs while holding in mindFootnote 11 the marked content of certain beliefs) in the background. The relevant rule might look something like this:

Non-Enkratic Rule: Given that

<I ought that p; belief>

<It is up to me whether or not p; belief>

<because of q then I ought that p; belief>

from

<q; belief>

derive

<p; intention>.

Notice that, unlike enkratic reasoning, reasoning that involves following the Non-Enkratic Rule does not seem to involve any blatant error. For example, there would be nothing remotely bizarre about treating the marked content of a belief that my paper is well-suited to Analysis as bearing positively on the question of whether to send it to Analysis.

Next, is reasoning by following the Non-Enkratic Rule correct reasoning? According to Broome, it will be correct just in case there is a corresponding valid basing permission of rationality, namely

Non-Enkratic Permission: So long as a) N believes that she herself ought that p, b) N believes that it is up to her herself whether p, and c) N believes that because of q then she herself ought that p, rationality permits N that

N believes at some time that q, and

N intends that p, and

N’s intention that p is based on N’s belief that q.

We encountered Non-Enkratic Permission above. We saw that Non-Enkratic Permission satisfies our test for rational basing. To be sure, this does not necessarily mean that Non-Enkratic Permission is valid. Nonetheless, I suspect that it is valid. If I’m right, then it follows that reasoning by following the Non-Enkratic Rule is correct reasoning.

This suggests an interesting alternative to Broome’s answer to the motivation question that is nonetheless in the spirit of Broome’s answer. According to the alternative answer, we are indeed able to bring ourselves to intend to do what we believe we ought to do by reasoning. But the kind of reasoning in question is non-enkratic reasoning. Our normative beliefs cause us to intend to do what we believe we ought to do, not by figuring in the foreground, but by figuring in the background. Moreover, it suggests that a certain kind of anxiety that Broome expresses about the possibility of enkratic reasoning is quite misplaced. Broome writes:

If enkratic reasoning is impossible, it seems unlikely that Enkrasia could be a genuine requirement of rationality. We could not come to satisfy Enkrasia by reasoning; we would have to rely on automatic processes (RTR, p. 291).

But non-enkratic reasoning of the kind we have been discussing points to a different way in which we could come to satisfy Enkrasia. Even if Broome’s implicit assumption that we must be able to come to satisfy genuine requirements of rationality by reasoning is right, the impossibility (or atypicality) of enkratic reasoning should do nothing whatsoever to undermine the claim that Enkrasia is a genuine requirement of rationality.

The second possibility is reasoning to intentions from beliefs involving moral oughts. Here is an example of a rule that one might follow:

Moral Belief Rule: From

<I morally ought that p; belief>

<It is up to me whether or not p; belief>

derive

<p; intention>.

Again, unlike enkratic reasoning, reasoning that involves following the Moral Belief Rule does not seem to involve any blatant error. For example, there would be nothing remotely bizarre about my treating the marked content of a belief that I morally ought to save a drowning surfer and the marked content of a belief that it is up to me myself whether or not I save her as bearing positively on the question of whether to save her.

Is it correct reasoning? Here we face a problem. According to Broome, it will be correct just in case there is a corresponding valid basing permission of rationality, namely

Moral Belief Permission*: Rationality permits N that

N believes at some time that she herself morally ought that p, and

N believes at some time that it is up to her herself whether or not p, and

N intends at some time that p, and

N’s intention that p is based on N’s belief that she herself morally ought that p and belief that it is up to herself whether or not p.

But Moral Belief Permission* is invalid. It would imply that I am rationally permitted to base an intention to save a drowning surfer on a moral belief when I believe that it is not the case that I ought unqualifiedly to save her. But this is not rationally permissible. And it would imply that I am rationally permitted to base an intention to save a drowning surfer on a moral belief when I lack beliefs whose truth entails that I ought unqualifiedly to save her. This is at least not obviously rationally permissible. Rather, the basing permission that I suggested above is

Moral Belief Permission: So long as a) it is not the case that N believes that it is not the case that she herself ought (unqualifiedly) that p and b) N has beliefs whose truth entails that N ought unqualifiedly that p, rationality permits N that

N believes at some time that she herself morally ought that p, and

N believes at some time that it is up to her herself whether or not p, and

N intends at some time that p, and

N’s intention that p is based on N’s belief that she herself morally ought that p and belief that it is up to herself whether or not p.

Yet it is impossible to formulate a rule of reasoning that corresponds to Moral Belief Permission, given Broome’s assumption that we cannot reason with the marked content of the absence of an attitude (RTR, 278–281). This assumption seems to me to be correct.

Does this mean that reasoning with Moral Belief Rule is not correct reasoning? Not necessarily. So long as (a) it is not the case that you believe that you ought unqualifiedly that p and (b) you have other beliefs whose truth entails that you ought unqualifiedly that p, then if you reason to an intention by following the Moral Belief Rule, you will comply with Moral Belief Permission (and not merely Moral Belief Permission*.) To my mind, this is enough for your reasoning to count as correct.

5 Conclusion

There is an amusing—hopefully true, but, if apocryphal, nonetheless instructive—story about Samuel Beckett, who was reportedly once asked by a rather earnest literary critic who Godot was supposed to be (presumably not for the first time). Beckett’s answer was rather striking: He (Beckett) had been watching a particular “stage” in the Tour de France. All the cyclists had apparently passed, but a contingent of spectators remained. Eventually curiosity compelled him to ask the spectators, “Vous attendez qui?” (“Whom are you waiting for?”) “Nous attendons Godot,” they replied. (“We are waiting for Godot.”) Literary sleuths determined that there was indeed a cyclist called Godot in the Tour that year, and that he indeed clocked a particularly unenviable time.

Does this mean that we have the answer to one of the most enduring puzzles in modern literature: that Godot is nothing more than a cyclist in the Tour de France? No. Rather, it is an important reminder that we should sometimes respectfully disregard what artists tell us about their own work.

I think the same is sometimes true of philosophers. Broome tells us that his book is about answering the motivation question. It seems to me that we should respectfully disregard what Broome says about his own book. Rather, his book is about three interestingly distinct yet related phenomena: normativity, rationality and reasoning. Most of the objections I have raised are not primarily objections to Broome’s account of normativity, rationality, and reasoning as such. Rather, they are primarily objections to these accounts as constituents of Broome’s answer to the motivation question. Broome has numerous fascinating and insightful things to say about the nature of normativity, the nature of rationality, and the nature of reasoning. It would justifiably be regarded as a major achievement to write a book that advances our thinking about any one of these fundamental topics. Rationality Through Reasoning substantially advances our thinking about all three.

Notes

Broome does not discuss the alternative idea that there is some kind of conceptual or constitutive connection between normative beliefs of a certain kind and intentions such that if we believe we ought to do something we will thereby (defeasibly) intend to do it (insofar as we are rational). See e.g. Smith (1994, esp. chs. 3, 5).

There are many things that we mean by “ought” such that our beliefs involving them do not raise, and hence cannot plausibly be at issue in, the motivation question. Take the so-called predictive ought, as when I say to a student: “I’m reading your paper now, and I ought to be finished by 2 o’clock.” Beliefs involving the predictive ought do not raise the motivation question. That’s because, in the typical case, believing that I ought in this merely predictive sense to be finished by 2 o’clock will not cause me now to intend to be finished by 2 o’clock; and insofar as my belief does not cause a corresponding intention, the motivation question simply does not arise. If, for some reason, my belief does happen now to cause me to form the corresponding intention, the explanation will presumably involve some psychological quirk that is relatively devoid of philosophical interest. (Indeed, in the typical case, the role of such a belief might even be said to be, in part, to foreclose the need to form an intention to be finished by 2 o’clock. The point is that I am sufficiently confident that I will be finished by 2 o’clock without having now to form an intention to be finished by 2 o’clock.)

For the purposes of evaluating Broome’s test it will be enough to deal with the rough formulation of Enkrasia given above. I feel at liberty to do so given that Broome also employs this formulation of Enkrasia in explicating the central ought. For Broome’s final and most precise formulation of Enkrasia, see RTR, p. 170.

Broome’s argument for its centrality rests on the idea that Enkrasia “constitutes one of the main bridges between theoretical and practical rationality” and that our beliefs involving the ought to which Enkrasia applies are special in that “they engage with practical rationality” (RTR, pp. 23–24).

It might be wondered why I don’t focus on Enkrasia proper. Broome’s elaboration and defense of Enkrasia is compelling and ingenious. But, so far as I can tell, Enkrasia plays no significant role in Broome’s answer to the motivation question beyond allegedly (though, to my mind, mistakenly) explaining the class of oughts that are at play in the motivation question.

Is this really true? First, it might be thought that Enkratic Permission is somehow validated or vindicated by Enkrasia, or vice versa. As a matter of fact, I believe that Enkratic Permission is not valid; I shall say why shortly. But even if it were valid, I see no reason to suppose that its validity is explained by the validity of Enkrasia, or vice versa. Unless I have misunderstood something in Broome’s account, nothing seems to rule out the possibility that Enkratic Permission could be true even though Enkrasia is false, or that Enkrasia could be true and yet Enkratic Permission false. That’s because Enkratic Permission is in one sense weaker and in another sense stronger than Enkrasia. It’s weaker than Enkrasia in the sense that whereas Enkrasia is a requirement, Enkratic Permission is a permission. So it seems at least possible that a skeptic about Enkrasia might allow that an agent is rationally permitted to form attitudes in accordance with Enkratic Permission while insisting that she would not necessarily exhibit any irrationality in violating Enkrasia. Enkratic Permission is stronger than Enkrasia in the sense that it involves the basing relation. So, again, it seems possible that a skeptic about Enkratic Permission might allow that an agent is necessarily irrational in violating Enkrasia while insisting that she is not rationally entitled to base an intention to act on a belief that she ought to perform that act.

Second, some of Broome’s remarks might be thought to suggest that he takes the fact that we are disposed to comply with Enkrasia to provide an answer to the motivation question—just not the right kind of agency-manifesting answer. For example, he writes: “We can call in rationality to help answer the motivation question. We can say that rationality requires people to intend to do what they believe they ought to do, and that it requires them to be disposed to do so—to have the enkratic disposition.” (RTR, p. 2). But, as Broome would readily concede, unlike the disposition to form intentions in accordance with Enkratic Permission, the disposition to comply with Enkrasia is simply the wrong kind of disposition for the purposes of answering the motivation question. It can explain why there is often a match between our intentions and our normative beliefs. But, of course, there are a number of different ways in which we might achieve such a match without our beliefs about what we ought to do causing us to intend to do what we believe we ought to do. First, it might be that where we believe we ought to X and yet don’t yet intend to X, our enkratic disposition means that we lose the belief that we ought to X. (Suppose that it causes us to revisit the issue of whether we ought to X and to interrogate relentlessly our reasons for believing that we ought to X—to the point where we lose the belief that we ought to X.) Second, it might be that where we believe we ought to X, our enkratic disposition means that we intend to X, but not because of our belief that we ought to X, but because of something else: say, a belief that our Xing has some non-normative property F (in virtue of which we take it to be the case that we ought to X). Third, it might be that where we believe we ought to X, our enkratic disposition means that we intend to X, that this is because of our belief that we ought to X, but that the “because” is a constitutive rather than a causal because. (One might think this if one thinks that intentions (or at least certain kinds of intentions) just are (special kinds of) beliefs about what we ought to do (see Schroeder 2009, p. 237; cf Scanlon 2007).

The amendments are friendly in two ways. First, the ensuing principle—Enkratic Permission***—represents an improvement on Enkratic Permission. It suggests a less restrictive answer to the motivation question; it can readily accommodates cases like the case where I intend to buy an anniversary present for Marie-Charlotte on the basis of believing that I ought to. Second, Enkratic Permission*** remains the right kind of principle for the purposes of offering the kind of answer to the motivation question that Broome is looking for: one that involves our bringing ourselves to intend to do what we believe we ought to do by engaging in correct reasoning.

One might deny this if one holds that moral requirements are “verdictive” (see Dancy 2000).

A marked content is a proposition with a “marker” to indicate the kind of attitude you have towards the proposition. For example, a very simple kind of modus ponens rule tells you to derive the marked content <q; belief> from the marked contents <p; belief> and <if p then q; belief>. Consider one of Broome’s examples. Suppose that you wake up and hear that it is raining, so you form the belief that it is raining. Suppose, moreover, that you also believe that if it is raining, the snow will melt. And suppose that you derive <the snow will melt; belief> from <it is raining; belief> and <if it is raining, then the snow will melt; belief> by correctly following the aforementioned modus ponens rule.

Full disclosure: This makes me skeptical that Broome has succeeded in identifying sufficient conditions for reasoning. But I won’t insist on that point here. My interest is primarily in evaluating Broome’s answer to the motivation question. What I do want to insist upon, then, is simply that the conditions that Broome takes to be sufficient for reasoning are not sufficient to explain how we might come to form certain intentions on the basis of our normative beliefs in the special agency-involving way that Broome takes it to be incumbent on any satisfactory answer to the motivation question to explain.

This reasoning test is clearly related to but also distinct from the rational basing test we offered above. The most important difference is that the reasoning test involves considering whether, in fact, the agent is disposed to adduce certain considerations in response to a “why?” question, not whether it is apt to do so.

I take the idea of “holding the contents of an attitude in mind” from Broome (RTR, p. 231). However, unlike Broome, I am assuming that reasoning can involve holding the contents of your attitudes in mind without operating on those particular contents. You are holding them in mind in the background while operating on the contents of other attitudes.

References

Anscombe, E. (1957). Intention. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Broome, J. (2013). Rationality through reasoning. Oxford: Wiley.

Dancy, J. (2000). “Should we pass the buck?” In A. O’Hear (Ed.), Philosophy, the good, the true, and the beautiful (pp. 159–174). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hieronymi, P. (2009). The will as reason. Philosophical Perspectives, 23, 201–220.

Kolodny, N. (2005). Why be rational? Mind, 114, 509–563.

Korsgaard, C. (2009). The activity of reason. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Association, 83, 23–43.

Scanlon, T. M. (2007). Structural Irrationality. In G. Brennan, R. E. Goodin, F. Jackson, & M. Smith (Eds.), Common minds: Themes from the philosophy of Philip Pettit (pp. 84–103). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schroeder, M. (2009). Means-ends coherence, stringency, and subjective reasons. Philosophical Studies, 143, 223–248.

Smith, M. (1994). The moral problem. Oxford: Blackwell.

Southwood, N. (2016). The thing to do’ implies ‘can.’ Noûs, 50, 61–72.

Southwood, N. (forthcoming). Constructivism about reasons. In D. Star (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of reasons and normativity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stroud, S. (1998). Moral overridingness and moral theory. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 79, 179–189.

Williams, B. (1981). Internal and external reasons. In B. Williams (Ed.), Moral luck (pp. 101–113). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article was presented at a workshop on Rationality Through Reasoning at the Australian National University in May 2015. I am grateful to Geoff Brennan, John Broome, Rachael Briggs, Garrett Cullity, R. J. Leland, Philip Pettit, and Kai Spiekermann for helpful feedback. I am especially grateful to John Broome, not only for his typically insightful remarks on that occasion, but for numerous highly profitable and enjoyable conversations about normativity, rationality and reasoning over the past 8 years. Research for the article was supported by DP120101507 and DP140102468.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Southwood, N. The motivation question. Philos Stud 173, 3413–3430 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0719-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0719-y