Abstract

This paper argues that the semantic facts about ‘because’ are best explained via a metaphorical treatment of metaphysical explanation that treats causal explanation as explanation par excellence. Along the way, it defends a commitment to a unified causal sense of ‘because’ and offers a proprietary explanation of grounding skepticism. With the causal metaphor account of metaphysical explanation on the table, an extended discussion of the relationship between conceptual structure and metaphysics ends with a suggestion that the semantic facts about ‘because’ tell against grounding-causation unity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Our standard explanatory vocabulary (‘because’, ‘explains’, etc.) can express metaphysical explanations involving grounding relations, the kinds of relations expressed by ‘in virtue of’ and similar phrases.Footnote 1 I argue in Shaheen (forthcoming) that the sense of ‘because’ used to express metaphysical explanations is distinct from the sense of ‘because’ used to express causal explanations, and I claimed that the former sense was metaphorical. In this paper, I elaborate what I call the causal metaphor account of metaphysical explanation. There are four basic pieces of the account. (i) The words of our explanatory vocabulary (‘why’, ‘because’, ‘explains’, etc.) have multiple senses. (ii) The words of our explanatory vocabulary have unified causal senses. (iii) The words of our explanatory vocabulary have distinct metaphorical senses, derived from the unified causal senses. (iv) The metaphorical senses of the words of our explanatory vocabulary are used when we express metaphysical explanations.

Given an identification of word-senses with concepts, it follows that sentences expressing metaphysical explanations exploit different concepts than causal explanations. But this does not mean that our causal concepts are of no help in illuminating metaphysical explanation. Rather, (iii) and (iv) give causal concepts a central role in accounting for our understanding of metaphysical explanations. In particular, while our explanatory concepts are not fully general, they are unified by a common structure, paradigmatically exemplified by causal explanatory relations.

Making clear the paradigmatic status of causal explanation for explanation in general is a major benefit of the causal metaphor account of metaphysical explanation. But what we want ultimately to know is what relations correspond to our explanatory concepts. So we need an account of how conceptual structure constrains metaphysical theorizing. Now, philosophers often argue from metaphysical difference to conceptual distinctness. In the course of establishing (ii), that the causal senses of our explanatory words are unified, this paper argues that this is but a common misconception: some differences just aren’t marked in our language or thought. But it also assays a route in the other direction, from conceptual distinctness to metaphysical difference. This paper argues that the causal metaphor account of metaphysical explanation puts defeasible constraints on our metaphysical theory vis-a-vis grounding–causation unity: if grounding were causal, we shouldn’t have needed to resort to metaphor.Footnote 2

This paper is structured in the following way: Sect. 1 introduces the polysemy of ‘because’ and reviews the relationship between metaphor and polysemy in natural languages. Since the polysemy account of ‘because’ requires treating the causal sense of ‘because’ as relatively unified, Sect. 2 justifies that treatment in light of the causal pluralism literature via a much-needed distinction between precisification and disambiguation. Since the polysemy account of ‘because’ requires understanding the sense of ‘because’ that is used to express metaphysical explanations as derivative from the causal sense, Sect. 3 exploits recent work by others to describe the metaphor linking metaphysical explanation with causal explanation. The main innovation here is to notice that extant accounts of the similarities between causal explanations and metaphysical explanations fit into the framework of metaphor-generated polysemy. The section ends with a proprietary explanation of the persistence of grounding skepticism, and a brief discussion of the extent to which the causal metaphor account of metaphysical explanation supports or undermines grounding skeptical arguments. Section 4 discusses the relationship between conceptual structure and metaphysical theory, and argues that the semantic facts about ‘because’ give us a reason to prefer metaphysical theories that neither treat grounding as a kind of causation nor treat both as a determinate of some common determinable. Section 5 extracts a familiar lesson from a new perspective: a focus on metaphysical explanation sentences helps us see again that causal explanation is explanation par excellence.

1 Metaphor and polysemy

Some comments on polysemy and the status of metaphorical senses are in order. Polysemy is to be distinguished from univocality or—to introduce my preferred terminology—monosemy, on the one hand, and homonymy, on the other. Monosemes have only one meaning, while polysemes have more than one meaning. Homonyms have unrelated meanings—cases of homonymy are really cases of distinct words that happen to be articulated by the same syntactic strings and phonetic sequences—while the meanings of polysemes are related to one another. A standard way of thinking about the relatedness criterion is in terms of priority relations between the senses.Footnote 3 On this standard view, one sense is basic, and the others are somehow derived from it; the basic sense is prior to the other senses, which are posterior to the basic sense.Footnote 4 To settle terminology, I use ‘ambiguity’ and related terms for a general category that includes both polysemy and homonymy.

I argue in Shaheen (forthcoming) that ‘because’ is polysemous. To say that ‘because’ is polysemous is to say that it has multiple related meanings, and the meanings I distinguish in Shaheen (forthcoming) are a causal sense and a metaphorical sense. The causal sense of ‘because’ is quite natural, in several respects. It is etymologically natural: ‘because’ derives from the phrase ‘by cause’. It is psychologically natural: we represent events to ourselves with causal structure.Footnote 5 It is semantically natural: the world plausibly contains objective causal structure that is the most magnetic of possible referents.Footnote 6 The metaphorical sense of ‘because’, however, seems to be psychologically, semantically, and even metaphysically gerrymandered. It certainly cannot be read off of the etymology of ‘because’. Consider the broad range of non-causal relations implicated in the metaphysical explanations expressed by (1)–(11).

-

(1)

The pious is pious because it is loved by the gods.Footnote 7

-

(2)

There’s a table in the room because there are simples arranged tablewise here.

-

(3)

It was a foul because the referee called it.

-

(4)

Michigan beat Kansas because the final score was 87-85 in Michigan’s favor.

-

(5)

Ajax won because they finished with a better goal differential than PSV Eindhoven.

-

(6)

‘Dog’ means dog because dog \(\rightarrow\) animal is valid.Footnote 8

-

(7)

That paper has a polysemous title because its title contains a polysemous term.

-

(8)

This is square because it’s a regular quadrilateral.

-

(9)

This is red because it’s crimson.

-

(10)

Holes in blocks of cheese exist because blocks of cheese exist.

-

(11)

The singleton of Zutty exists because Zutty exists.

The explanantia named in these sentences variously make their explananda the case (1); materially constitute their explananda (2); provide necessary (3) or sufficient (4) or INUS (5) conditions for their explananda; are that partially (6) or fully (7) in virtue of which their explananda are true; are genus/differentia characterizations of the species named in the explanandum (8); are determinates of the determinable named in the explanandum (9); and are that on which their explananda are feature (10) or constituent (11) dependent.Footnote 9 What unifies this broad range of non-causal dependence relations into a single sense of ‘because’, this paper argues, is that causation provides a model via the same metaphor for each of these dependence relations.Footnote 10

Metaphor is but one of a variety of mechanisms linguists posit for the derivation of additional senses.Footnote 11 The idea that metaphor can be the basis for conventionalized meaning has long been familiar to philosophers of language.Footnote 12 A metaphor gives way to literal meaning as the metaphor dies.Footnote 13 To see how metaphor gives rise to distinct conventionalized meanings, consider ‘leg’. Its basic sense, let us suppose, is anatomical. Parts of tables are not in the intension of that anatomical sense, so ‘leg’ in the anatomical sense cannot be used literally to refer to parts of tables. It is somehow too specific to apply literally to table legs. Nevertheless, someone who is familiar only with the anatomical sense of ‘leg’ could nevertheless be expected to make sense of talk about table legs. In order to do so, she would retain as much of the anatomical sense of ‘leg’ as is consistent with its application to tables.Footnote 14 Thus, while anatomical legs are what support and move the bodies of animals equipped with them, she would take table legs to be the parts of tables that support them. (Features of a basic sense abstracted away in order to interpret a metaphorical use can still exert their force, long after a metaphor dies. Imagine an animation of a table that can move. Of course you imagine it walking on its legs.) Moreover, if our speaker found herself in a community of speakers that habitually used ‘leg’ to refer to table legs, she’d soon hear a furniture-related sense of ‘leg’. That is, ‘leg’ for her would take on a second literal meaning. Thus metaphorical sense extension generates polysemy when a word becomes conventionally applied to referents that its literal sense does not cover.

To see how metaphorical sense extension applies to our case, we have to see (i) what the basic sense is and (ii) how it applies to the new area. Dealing with (i) will occupy us in the next section, and then we will be able to turn to (ii) by indicating the similarities exploited by the metaphor in Sect. 3.

2 How not to be a causal ambiguist

I take there to be a unified causal sense of ‘because’. But it is not obvious that all causal explanations have much in common. In fact, Weber et al. (2005) advance a pluralism for causal explanation, according to which there are multiple different forms of causal explanation, each relating to a different kind of “underlying causal structure” backing the explanation.Footnote 15 An argument from this difference in forms of causal explanation to distinct causal senses of ‘because’ would not be entirely novel. It would rather recall the causal pluralism debate, where causal pluralists have characterized multiple distinct causal concepts, which are then (sometimes) taken as grounds for believing that ‘cause’ is ambiguous. In “How to Be a Causal Pluralist,” for example, Christopher Hitchcock goes so far as to take “the central tenet of causal pluralism to be the claim that ‘cause’ and its cognates have multiple senses.”Footnote 16 To be a causal pluralist, on Hitchcock’s view, is to be a causal ambiguist. One might further worry that the existence of multiple distinct causal senses of ‘because’ would follow from the ambiguity of ‘cause’. I’m not sure the worry is well-placed—why isn’t it just a root fallacy?—but I’m happy to grant the entailment to my opponent. It’s safe for me to do so because, despite what some causal pluralists might have you believe, ‘cause’ isn’t ambiguous.Footnote 17

This is not to say that causal pluralism, taken as the thesis that causal relations are not metaphysically uniform and therefore require multiple distinct analyses, is false. Indeed I take it that causal pluralists have in at least some cases correctly distinguished different causal notions. But ‘cause’ doesn’t denote any particular one of those notions to the exclusion of the others.Footnote 18 Our ability to make conceptual distinctions in general does not require our words to pick out more specific concepts to the exclusion of less specific concepts. In the context of the present investigation, it is essential to distinguish precisification from disambiguation, and to see that the causal pluralism literature is concerned only with the former task. In general, theoretically precisified concepts are only in special cases the meanings of the words of natural languages.Footnote 19 Proper attention to our use of ‘cause’ shows that none of the precise concepts of cause on offer in the causal pluralism literature qualifies as one of its disambiguations in the sense relevant to semantics of ‘cause’. All of them are rather more precise than what is expressed by ‘cause’: they are all precisifications of that concept.Footnote 20 Proper attention thus vindicates monosemy accounts.Footnote 21 After I make this argument, I will present a parallel argument that pluralism about causal explanation provides us with no reason to think there are multiple causal senses of ‘because’, either.

Causal pluralists make a variety of distinctions between kinds of causation.Footnote 22 For the moment I propose to take Hall (2004) as my representative causal pluralist, since the relevant issues can be made quite clear in discussing his view.Footnote 23 According to Hall, we do not have a “univocal concept” of causation; rather, there are distinct concepts of production and counterfactual dependence. The production concept is (non-exhaustively) characterized by a number of intuitive theses about causation.

-

(12)

Transitivity: If event c is a cause of d, and d is a cause of e, then c is a cause of e.

-

(13)

Locality: Causes are connected to their effects via spatiotemporally continuous sequences of causal intermediates.

-

(14)

Intrinsicness: The causal structure of a process is determined by its intrinsic, non-causal character (together with the laws).Footnote 24

The counterfactual dependence concept is simple counterfactual dependence: c causes e just in case, had c not occurred, e would not have occurred.Footnote 25 Hall argues that counterfactual dependence comes into conflict with Transitivity, Locality, and Intrinsicness, the theses that characterize production, concluding that counterfactual dependence and production are simply different causal concepts.

Hall seems to accept that his claim about the existence of two causal concepts would entail that ‘cause’ is ambiguous.Footnote 26 He directly commits himself to there being a counterfactual dependence sense of ‘because’.Footnote 27 It is unclear, though, what the claimed possibility of distinguishing different kinds of causation has to do with the semantics of ‘cause’ or related terms. Our ability to distinguish different breeds of dogs does not establish that ‘dog’ is ambiguous. The fact that we can kick with our left and right feet does not mean ‘kick’ is ambiguous between a sense for right-footed kickings and a sense for left-footed kickings. Rather, when we call something a dog or say somebody kicked something, we are not making maximally specific statements. We can convey more information about what exactly is the case by saying something more precise, by calling the dog a miniature dachshund or saying the person kicked a soccer ball with her left foot. But to say something less than maximally precise is not to say something ambiguous. To return to Hall’s causal pluralism, the counterfactual dependence “sense” of ‘because’ is at best a precisification of a broad causal sense, as are the counterfactual dependence and production “senses” of ‘cause’.Footnote 28

If Hall’s production and counterfactual dependence are two concepts of causation, the broad causal sense is a third. But this third, I claim, is the concept expressed by the unambiguous English word ‘cause’. That none of the precise concepts described in the causal pluralism literature is a genuine sense of ‘cause’ can be seen from our linguistic practice. I will mention two features of our linguistic practice that support the monosemy of the English noun ‘cause’ here, though the stock of evidence to follow can be reproduced for the English verb ‘cause’, and could easily be enlarged for both the noun and the verb.Footnote 29 First, an ambiguity hypothesis along the lines of Hall’s distinction makes predictions about truth-conditions that are not borne out by the facts. To see this, consider first the truth-conditional behavior of a genuinely ambiguous term. Following Godfrey-Smith (2009), I’ll use ‘mad’. Imagine (15) and (16), said of an insane philosopher who is happily laughing.

-

(15)

That gleeful philosopher is mad.

-

(16)

That gleeful philosopher is mad, but he’s not insane.

(15) has a reading on which it’s false, since angry people aren’t gleeful. It also has a reading on which it’s true, since, as we are imagining, the philosopher in question is insane. On the angry reading of ‘mad’, (16) is again false—angry people still aren’t gleeful. But on the insane reading of ‘mad’, it’s straightforwardly self-contradictory. Now consider a case of production without counterfactual dependence, say, where Billy throws a rock that shatters a vase, though Suzy also threw a rock that would have shattered the vase had Billy not thrown his rock.

-

(17)

Billy’s throwing of the rock was the cause of the shattering of the vase.

-

(18)

Billy’s throwing of the rock was the cause of shattering of the vase, but it would’ve been shattered even if he hadn’t thrown it.Footnote 30

If there were a specific counterfactual dependence sense of ‘cause’, there would be a reading of (17) on which it’s false, and a reading of (18) on which it’s contradictory. But there are no such readings, precisely because there is no specific counterfactual dependence sense of ‘cause’.

Second, we do not need to disambiguate causal claims before we understand them. We might attempt to precisify a causal claim, even (colloquially) asking what our interlocutor means by her causal claim.Footnote 31 But when we do so, we are typically seeking the facts behind her claim rather than trying to disambiguate it. At best, Hall has isolated, in his notions of production and counterfactual dependence, ways of making causal claims true.Footnote 32 It may be relevant to our dialogue whether the cause she cites produced the effect in question or is merely something on which it depends. But finding out what makes it the case that the cause cited is a cause is not the same thing as finding out that it is a cause in one sense or another. Of course, there may be natural language expressions corresponding to the production or counterfactual dependence concepts, and if there aren’t, nothing would prevent us from coining terms for the concepts. But ‘cause’ expresses a more general concept that counts among its paradigm cases not one or the other of paradigm cases of production and paradigm cases of counterfactual dependence, but both.

Metaphysical heterogeneity does not in general underwrite ambiguity. We can distinguish four categories of words with respect to the metaphysical heterogeneity of their referents and ambiguity. Some words are polysemous (or homonymous), having distinct senses that denote metaphysically different kinds of things.Footnote 33 ‘Book’ falls in this category. It is polysemous between concrete object and abstract text senses. The different senses track metaphysically different kinds of things. Other words are monosemous, having a single sense that denotes just one kind of thing. ‘Electron’ falls in this category. It univocally denotes electrons. Yet other words are monosemous but disjunctive, having a single sense that denotes metaphysically different kinds of things. ‘Jade’, as philosophers commonly think of it, falls in this category. To be jade is to be jadeite or nephrite, but ‘jade’ requires no disambiguation. Its single sense is just disjunctive.Footnote 34 This third category of words is enough to give the lie to any form of causal pluralism that infers ambiguity from metaphysical difference. But still further words are monosemous and have a metaphysically heterogeneous intension but a non-disjunctive sense. ‘Jade’ in an imagined pre-discovery history where nobody knew jadeite and nephrite were different substances falls in this category.Footnote 35 So, I claim, does ‘cause’.

‘Cause’ does not fit neatly into any of the first three categories described above. As Hall and other causal pluralists have argued, ‘cause’ can denote different kinds of things, like ‘book’ and ‘jade’, but unlike ‘electron’. It is nevertheless monosemous, like ‘electron’ and ‘jade’, but unlike ‘book’. But ‘cause’ is not just disjunctive in the way that we might think ‘jade’ is. A case described by Hall suggests that ‘cause’ is not restricted to denoting relations of either production or simple counterfactual dependence. In the case, one of two fighter planes escorting a successful bombing mission shoot down an enemy fighter. Had the enemy fighter not been shot down, the bombing mission would not have succeeded. We judge that the escort plane’s shooting down of the enemy fighter is among the causes of the mission’s success. The escort plane’s shooting down of the enemy fighter does not, however, produce the success of the mission: it is too far away from the site of the bombing to do that (recall Locality). Further, the description of the case goes on to specify that, had the escort plane not shot down the enemy fighter, the other escort plane would have. So the success of the mission does not counterfactually depend on the escort plane’s shooting down of the enemy fighter. To sum up, the escort plane’s shooting down of the enemy fighter is a cause of the success of the mission without producing it and without the success of the mission counterfactually depending on it. So ‘cause’ cannot just denote the relation that holds whenever there is production or counterfactual dependence. (Any such account of ‘cause’ would be intensionally, even extensionally, inadequate.) So ‘cause’ is not just disjunctive like ‘jade’, at least not along the joint mapped by Hall’s distinction between production and counterfactual dependence.

The stronger claim that ‘cause’ is not disjunctive like ‘jade’ along any such joint may also be defended. I take it that the meaning of ‘jade’ is really the disjunction jadeite or nephrite. Competent speakers of English may not know that there are two kinds of jade, just as many of them do not know exactly what it takes for something to be an elm tree. Semantic externalism comes into play here for ‘jade’ as it does for ‘elm’.Footnote 36 But semantic externalism does not seem to justify the identification of some disjunction as the meaning of ‘cause’. Speakers do not become more competent with ‘cause’ through acquaintance with the causal pluralism literature in the way that speakers gain real mastery of ‘elm’ or ‘jade’ through acquaintance with the relevant botanical or mineralogical facts. (Metaphysicians do not, in virtue of anything in the causal pluralism literature, get to correct native speakers on when to use ‘cause’.) Further, it is unclear what would privilege any particular disjunction identified through the causal pluralism literature to be the disjunctive meaning of ‘cause’. Nothing said in that literature obviously makes production or counterfactual dependence a better candidate disjunctive meaning of ‘cause’ than type causation or token causation. It seems that any such disjunction will get the meaning of ‘cause’ right only intensionally. In at least this respect, then, ‘cause’ is more like ‘electron’ or like ‘jade’ during the imagined pre-discovery period than like ‘jade’ now: it just means cause.

I suspect what is really going on with ‘cause’ as a monoseme with a metaphysically heterogeneous intension is that it has a collection of metaphysically heterogeneous paradigm or prototype cases. This collection includes, presumably, productive causes, causes on which their effects counterfactually depend, type causes, token causes, and all the rest of the kinds of causes distinguished in the causal pluralism literature. (Actually, given that production and counterfactual dependence often go together, the collection need not include a different paradigm case for each of Hall’s precisifications.) What makes the action of the escort plane in Hall’s example count as causal is that it is close enough to paradigm cases of causation. For one thing, it bears a close resemblance to causes on which their effects counterfactually depend, since the success of the mission does counterfactually depend on the enemy fighter being shot down somehow or other, and the escort plane’s action is one way for the enemy fighter’s being shot down to happen. For another, the escort plane produces an omission on which the success of the mission counterfactually depends. Ideally, the class of constellations of prototype causes with which competent speakers of English are familiar would be specifiable in a way that explains not only the metaphysically heterogeneity of the intension of ‘cause’ already noted, but also the host of normative and other considerations that many psychologists think influence our causal judgments: that agents are magnets for causal attribution, that temporal order of events matters to causal attribution, and that various normative considerations play a role in causal attribution might all be explained this way.Footnote 37

To return to the dialectic, we have seen with ‘cause’ that monosemy is no bar to metaphysical heterogeneity in kinds of causes, as precisification is not disambiguation. It is now time to apply this lesson to pluralism about causal explanation. I make the point with respect to two notions of causal explanation, which I will call (i) etiological explanation and (ii) evolutionary explanation.Footnote 38 Etiological explanations say how some state of affairs came about. Evolutionary explanations say why a system evolves to a state. The precise definition of each kind of explanation is not of any particular importance for present purposes, so many details will be glossed over in what follows. In particular, I rely on an intuitive grasp of notions of causal interactions, interference, and triggering. Particular spellings out of these notions may have consequences for the exhaustiveness of the classification of causal explanations considered here.Footnote 39 But I hope that the discussion here will have already provided the blueprint to deal with any remaining cases.

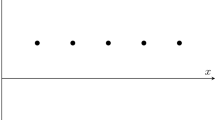

Etiological explanations, then, explain an object x’s having a property P at a time t by adducing a causal interaction at an earlier time \(t'\) in which x took on the property P and noting that no causal interactions interfere with x’s having P between \(t'\) and t.Footnote 40

-

(19)

The window is broken now because a baseball crashed through it earlier.

The sentence in (19) communicates an etiological explanation. The window’s being broken now is explained by the causal interaction during which it was broken. The window’s not having been fixed in the interim is not mentioned in (19), as it is characteristic of ‘because’ sentences that they do not need to mention the omission of interference to be true.Footnote 41

Evolutionary explanations explain an object x’s having a property P at time t by adducing a causal interaction at an earlier time \(t'\) in which x took on a suite of properties \(Q_1,\ldots ,Q_n\) which jointly triggered an evolution resulting in x having property P at time t.Footnote 42

-

(20)

The vessel contains a homogeneous mixture of fluid A and fluid B now because heated fluid B was added to the vessel earlier.

The sentence in (20) communicates an evolutionary explanation. The vessel’s containing a homogeneous mixture now is explained by its having had a heated (relative to fluid A) fluid B added to the vessel earlier. It is worth spelling out how the sentence in (20) qualifies as providing an evolutionary explanation. The suite of properties \(Q_1,\ldots ,Q_n\) taken on by the vessel when the fluid was added includes the property of containing liquid with a particular temperature gradient. The liquid with that temperature gradient then evolved into a homogeneous mixture. (20) can only be understood to be true by someone who is aware of the connection between combining liquids of different temperatures at one time and homogeneity of the mixture at a later time.

For a slightly more complicated example, consider how to explain price changes in markets. Typically an event occurs that results in a mismatch between the current price and the equilibrium price. We can think of such an event as a causal interaction in which the market takes on a suite of properties. Such events include changes in production costs and all of the other typical causes of changes in supply or demand curves listed in introductory economics textbooks. The suite of properties taken on includes, most importantly, a difference in the levels of supply and demand at the current price. This sets in motion an almost arbitrarily complex process that issues in the establishment of a new price: sales and warehouse inventories are tracked, meetings are held, decisions are made.Footnote 43 Again, ‘because’ sentences expressing this kind of evolutionary explanation typically adduce the causal interaction responsible for the initial suite of properties, but not the causal pathways of the subsequent evolution.

-

(21)

The stock price is $50 now because the earnings report was good.

The event responsible for the initial causal interaction that produced the difference in supply and demand is cited in (21). Earnings reports move stock prices, we may suppose, by moving the supply and demand curves for stocks. But the causal details of the process by which the stock price moves to $50 are not mentioned in (21), even though the process might unfold in an incredible variety of ways. This is a general feature of evolutionary explanation, then, and not one confined to evolutionary explanations with relatively predictable paths of evolution like the one communicated by (20). It can suffice to cite events that set a process in motion in order to explain a later state of the process.Footnote 44

The foregoing comments suffice to draw a distinction between etiological and evolutionary explanation. No careful analysis of the two notions has been attempted here, but it should now be possible to see that ‘because’ is not ambiguous between them. Consider first the truth-conditional behavior of ‘because’. Holding fixed the facts that make at least one reading of (19) true, there’s no alternative ‘disambiguation’ of (19). The same holds of (20) and (21). If, moreover, ‘because’ had a specific etiological explanation sense, there would be a reading of (20) on which the vessel takes on the property of containing a homogeneous mixture of fluid A and fluid B when the heated fluid B is added to the vessel. Given that reading of (20), there should be a contradictory reading of (22).

-

(22)

The vessel contains a homogeneous mixture of fluid A and fluid B now because heated fluid B was added to the vessel earlier, but the vessel did not take on the property of being a homogeneous mixture when the heated fluid B was added.

But of course there is not a contradictory reading of (22). Further, cross-linguistic evidence does not support an ambiguity claim for ‘because’ along the lines of the etiological explanation/evolutionary explanation distinction.Footnote 45 As with ‘cause’, we find here a unified causal sense of ‘because’.Footnote 46

The dialectical purpose of the extended discussion of pluralism, the relationship between metaphysical heterogeneity and ambiguity, and the difference between precisification and disambiguation in this section was to establish that there’s a unified causal explanatory sense of ‘because’ to serve as the basis for the causal metaphor that gives rise to the polysemy of ‘because’ by extending its meaning to cover metaphysical explanations. We are now ready for the metaphor.

3 The causal metaphor

What it takes to describe the metaphor depends in part on the theory of metaphor adopted.Footnote 47 But on standard views of metaphor there must be some substantial similarity between what is denoted by a basic sense and the phenomena to be comprehended under a metaphorical sense. What I want to do in this section is to exhibit that there is enough similarity between the senses for metaphor to be a plausible explanation of the extension of ‘because’ to the sense that covers metaphysical explanation, on standard views of metaphor. The important point will be that the similarities described here suffice to illuminate how the sense of ‘because’ covering metaphysical explanation fits the story according to which metaphor gives rise to polysemy.

To begin with, it’s worth noting that we deploy terminology from our causal discourse in our discourse about metaphysical dependence. Consider the range of causal idioms, in addition to ‘because’, that we use to talk about metaphysical dependence and metaphysical explanation.

-

(23)

The pious being loved by the gods makes it the case that it is pious.

-

(24)

Zutty’s existence explains the existence of the singleton containing him.

-

(25)

That this is square follows from its being a regular quadrilateral.

-

(26)

This is red by virtue of being crimson.

The italicized locutions in (23)–(26) qualify as causal idioms in that they can and often are used in expressing claims about causes and their effects: causes explain the effects they make; effects follow from their causes, we sometimes say, by virtue of some relevant power. Nevertheless, the causal idioms, as deployed in (23)–(26), express metaphysical explanations rather than causal ones.

As Lakoff and Johnson (1980) would put it, grounding is causation is a structural metaphor. A cognitive linguist confronted with (23)–(26) might say that causation structures our understanding of metaphysical dependence. On Lakoff and Johnson’s view, our thought processes themselves are “largely metaphorical” (6). If they were to accept the view of this paper, as I think they would, then they would claim that we think about grounding in part by means of the causal metaphor. They would also hold that causation “provides us with a partial understanding” of what grounding is (12). Nevertheless, the metaphor grounding is causation does not support an identification of grounding with causation, by their lights, because there are some features of causation that grounding does not have (e.g., diachronicity).Footnote 48

Thus not every facet of causation applies to metaphysical dependence, and it is not even necessary to use causal idioms to talk about metaphysical dependence.

-

(27)

There being simples arranged tablewise here is just what it is for there to be a table here.Footnote 49

-

(28)

Bill’s pain is nothing over and above his C-fiber sensitization.Footnote 50

-

(29)

That paper has a polysemous title in virtue of its title’s containing a polysemous term.

The occurrence of a cause is not what it is for an effect to occur, and an effect is something over and above its cause. Further, while ‘by virtue of’ is a common causal idiom, ‘in virtue of’ is something of a philosopher’s locution.Footnote 51 Still, the patterns of usage here suggest that there is at least a partial overlap in how we think about metaphysical explanation with how we think about causal explanation.

Recent entrants in the literature show that we can do better than this mere suggestion. We can elaborate in some technical detail a host of properties that causation and grounding, the relations respectively backing causal and metaphysical explanation, have in common.Footnote 52 Both relations are structurally similar: both are (claimed to be) partial orders to which we can apply the sophisticated formalism of structural equations models. Both relations have metaphysical bite: they back explanations, support counterfactuals, and frighten logical positivists.Footnote 53 Both relations inspire the same kinds of suggestive description: they are ‘generative’, ‘productive’, ‘building’ relations.Footnote 54 Some even entertain the possibility that grounding and causation are subsumable in a metaphysically important sense under some more general category.Footnote 55

Causal explanation and metaphysical explanation also permit similar partial explanantia in ‘because’ sentences. Just as we can sometimes say that the match lit because there was oxygen in the room, we can sometimes say that Ajax won Eredivisie because the season ended. Just as the presence of oxygen is a background condition that makes it possible for striking the match to cause it to light, the season ending is a background condition that makes it possible for a goal differential to ground a league championship. In both cases, the relevant ‘because’ sentences can felicitously communicate the background conditions to an inquirer who lacks only the knowledge that they obtained.

None of the foregoing similarities, however, could suffice to establish the metaphysical unity of metaphysical explanation and causal explanation in the face of the causal metaphor account of metaphysical explanation. Recall how metaphor gives rise to polysemy. When a word or a phrase is used metaphorically in a sentence, its conventional, literal meaning is somehow too specific to apply. But, as long as there are enough similarities between the literal intension of the word or phrase and what the word or phrase is being used to characterize, speakers are able to make sense of the resulting metaphor. With long enough exposure to such uses, the metaphorical use may become conventionalized. But the important thing for present purposes is that the metaphorical use is based on some discernible similarity between what is literally denoted by the word or phrase and what is being characterized metaphorically, while also presupposing that there are differences between them. If it weren’t for the differences, there would be no need for a metaphor. In our case of interest, I show in Shaheen (forthcoming) that the causal sense of ‘because’ is not operative in metaphysical explanatory uses. The host of shared properties mentioned above is nevertheless basis enough for a metaphorical extension of the causal meaning of ‘because’, allowing us to make sense of ‘because’ sentences like (1)–(11).

The metaphorical status of the sense of ‘because’ that covers metaphysical explanation can help explain grounding skepticism while providing ammunition for grounding skeptics. Schaffer (2016) provides paradigm cases of grounding, various suggestive analogies, and a formalism for handling grounding claims, and then challenges the skeptic to “say what more is needed” to clarify the notion.Footnote 56 But if our only way of understanding the paradigm cases is via suggestive analogies and the formal similarities between grounding and causation, then grounding itself is understood only via a causal metaphor.Footnote 57 Metaphor, of course, is just the sort of thing that eludes precise characterization—recall the Davidsonian deflation of the semantic content of metaphors. What more is needed may just be the one thing we can’t have: a real definition.Footnote 58

Let me expand briefly on the relationship between the causal metaphor account of metaphysical explanation and grounding skepticism.Footnote 59 Some skeptics are motivated by the feeling that grounding talk is unintelligible. Daly (2012) makes that charge directly, and Hofweber (2009) before him alleged that grounding theorists were engaged in ‘esoteric metaphysics’, a kind of philosophical project that addresses questions that cannot be posed in everyday language. J. Wilson (2014) and Koslicki (2015), on the other hand, argue that there is no utility gained by positing a unified grounding relation, since all of the important metaphysical work is done, in one way or another, by what Wilson calls ‘small-g grounding relations’.Footnote 60 I think that the causal metaphor account of metaphysical explanation explains but undermines the unintelligibility and esotericism charges, while it coheres with the utility-based skepticism of Wilson and Koslicki.

To explain, the causal metaphor account of metaphysical explanation tells us how we understand grounding claims. So it should not be invoked as part of a defense of the unintelligibility of grounding talk, except by those who are also willing to defend views of metaphor (like the Davidsonian one) on which metaphors fail to fix any non-literal content. Far from being willing to defend such views, I do not even accept them, and so I regard my account as undermining unintelligibility claims. But the causal metaphor account can provide the semantic backstory to the unification-in-name of the various small-g grounding relations. What each such relation has in common is its analogy with causation, its suitability for the causal metaphor. So my account coheres with the skeptical story that Wilson and Koslicki want to tell. But I don’t think the account can settle the question of grounding skepticism by itself; whether there is grounding depends on how the world is.Footnote 61

4 From semantics to metaphysics

We have now seen the basis for the claim that the sense of ‘because’ that covers metaphysical explanation is metaphorical. That linguistic claim explains the polysemy observed in Shaheen (forthcoming). Further, if the polysemy claim and its explanation are right, it will be of special interest to the philosopher if it tells us something about the relationship between causal and metaphysical explanation. Insofar as words express concepts, we can take the linguistic difference between senses of ‘because’ to reveal an underlying conceptual distinction between causal explanatory concepts and metaphysical explanatory concepts. That conceptual distinction might be reflected by some metaphysical difference between causal explanation and metaphysical explanation, but it might equally be a distinction without a difference. For it to bear on metaphysical questions requires an account of the relationship between our conceptual structure and the world. The argument of Sect. 2 was that metaphysical differences between distinct precisifications of our concepts did not guarantee semantic ambiguity. We now need to see how semantic ambiguity can give us reason to believe in metaphysical differences.

It will help to see how the relationship between semantics and metaphysics works in some more ordinary cases. In some cases, we have distinct words for what are essentially the same kinds of things. Thus ‘astronaut’ and ‘cosmonaut’, at least as they were used during the Cold War, differ in extension. Their meanings incorporate intentional gerrymandering: astronauts were American, cosmonauts were Soviet. The distinction hung on through the end of the Cold War, with ‘cosmonaut’ being reserved for Russians (and other Roscosmos space-travelling personnel, like Latvian-born cosmonaut Aleksandr Kaleri). As other nations developed space programs, the gerrymandering exerted its force. Thus we now have ‘taikonaut’, ‘spationaut’, and ‘vyomanaut’. The terms ‘ruby’ and ‘sapphire’ mark similarly gerrymandered distinctions within the natural kind corundum: rubies are the red ones, while a piece of corundum of any other color is a sapphire. In neither case does metaphysically deep unity override patterns of use that follow metaphysically shallow joints. In other cases, we insist on semantic unity in the face of deep metaphysical difference. Consider again our example ‘jade’ (as it is used now, not as it was used in an imagined pre-discovery past). The chemical differences between jadeite and nephrite must be reflected by differences between their metaphysical grounds, so ‘jade’ indeed covers very different sorts of things. Semantics is misleading as a guide to metaphysics in all of the cases so far: we make distinctions without a deep difference when it comes to space travelers and corundum, but elide real differences in our talk about jade.

A more interesting kind of case involves metaphysical unity exerting its force to determine word meaning. Thus despite the fact that people might have used ‘mammal’ or ‘ape’ in a way they thought excluded whales and people, respectively, from their intensions, biological facts overrode those patterns of use. It took no change in the meaning of ‘mammal’ or ‘ape’ for us to recognize that whales are mammals and that people are apes, but only the discovery of certain scientific facts.Footnote 62 Legal cases also exhibit the resistance of word-meanings to gerrymandering. Justice Alito, for example, recently wrote that the admission that non-profit corporations can count as ‘persons’ suffices to require that the meaning that covers non-profit corporations also cover for-profit corporations:

This concession effectively dispatches any argument that the term “person” as used in RFRA does not reach the closely held corporations involved in these cases. No known understanding of the term “person” includes some but not all corporations. The term “person” sometimes encompasses artificial persons (as the Dictionary Act instructs), and it sometimes is limited to natural persons. But no conceivable definition of the term includes natural persons and nonprofit corporations, but not for-profit corporations. (To give th[e] same words a different meaning for each category would be to invent a statute rather than interpret one).Footnote 63

Justice Alito here notes a pressure not to interpret words as having gerrymandered meanings. But the legal meaning of ‘person’ according to which both ‘natural persons’ and corporations are persons is itself extremely gerrymandered. This gerrymandering is allowed only because it is made explicit in the law.

Under the Dictionary Act, “the wor[d] ‘person’...include[s] corporations, companies, associations, firms, partnerships, societies, and joint stock companies, as well as individuals.” (“We have no doubt that person, in a legal setting, often refers to artificial entities. The Dictionary Act makes that clear”). Thus, unless there is something about the RFRA context that “indicates otherwise,” the Dictionary Act provides a quick, clear, and affirmative answer to the question whether the companies involved in these cases may be heard.Footnote 64

This shows that any gerrymandering made sufficiently explicit in a linguistic intention can take hold.Footnote 65 Doubtless there are groups of speakers of English who insist on using ‘ape’ in a way that would make ‘men are apes’ false in their dialect if they could isolate themselves well enough. Doubtless Ishmael spurns Linnaeus and invokes Jonah sincerely enough that ‘whales are fish’ expresses a true proposition in his idiolect.Footnote 66 There is probably a possible world where Dupré succeeds in his campaign to revise our use of ‘fish’ so that it makes sense to call whales ‘mammalian fish’. But in the more usual case, where people use ‘ape’, ‘fish’, and ‘person’ in order to pick out biologically or legally natural kinds, considerations of naturalness are overriding.Footnote 67

What we’d really like, though, is an argument from semantic distinctness to metaphysical distinctness. It would be nice to have an argument that polysemy only occurs in cases of difference. After all, if a single meaning were adequate to the uses to which a word is put, polysemy should not arise. There are a few different classes of polysemes against which to test this idea. The different senses of synaesthetic adjectives, which apply across multiple sense modalities—think here of ‘bright’ and ‘hot’—denote distinct properties. Our best explanations of at least some synaesthetic adjectives do find an underlying neurophysical similarity responsible for their multi-modal uses. The culinary use of ‘hot’, for example, may well be grounded in the fact that capsaicin, the chemical responsible for sensations of spicy tastes, activates a receptor that is also activated by painful heat.Footnote 68 But nevertheless capsaicin and high kinetic energy are quite different sorts of things. The different senses of double-function adjectives, which have both physical and psychological meanings—think here of ‘soft’, ‘sweet’, and ‘bitter’—also denote distinct properties.Footnote 69 Polysemous nouns like ‘book’, which has abstract and concrete senses, and ‘chicken’, which has animal- and meat-specific senses, again denote distinct kinds of things. The pattern holds for words that get used metonymically despite the fact that their metonymic uses are not encoded in the lexicon: here I am thinking of ‘the ham sandwich’, used to refer to the person who ordered the ham sandwich, and the like. In all of these cases, polysemy reflects an actual metaphysical difference.

So the fact of polysemy (at least typically) suggests underlying difference. We might even say that mastery of a polysemous word requires distinguishing between what is denoted by its distinct meanings. A speaker really has not mastered our use of the word ‘hot’ if she doesn’t realize that ‘this chili is hot’ is ambiguous. The world could nevertheless fail to cooperate with such distinctions: what is required by semantic competence is not guaranteed to track truth.Footnote 70 It could happen that an extremely natural, joint-cutting kind of relation, or even an extremely natural, joint-cutting particular relation, turns out to back both metaphysical explanations and causal explanations. In that case, we should think that metaphysical explanation is a kind of causal explanation (or vice versa), that grounding and causation are species of the same genus, or even that we should identify metaphysical explanation with causal explanation, identify grounding with causation. But our default position should be to recognize the distinction encoded in the polysemy of our explanatory language.

It is time to step back and take stock. The causal metaphorist, who thinks that causal explanation provides the basis for a metaphor used to talk about metaphysical explanation, and the unificationist, who thinks that metaphysical explanation just is a species of causal explanation (perhaps because grounding just is a species of causation) can agree that causation and grounding, the relations backing these kinds of explanation, are similar in lots of ways. Pointing to any particular similarity bolsters both cases equally. It adds to the stock of similarities the causal metaphorist can invoke. It also adds to the evidence of underlying sameness the unificationist can invoke. But to bolster both cases equally is to bolster neither at all as against the other. Further, insofar as the causal metaphorist can point to polysemy in our explanatory terminology of the kind I argue it exhibits in Shaheen (forthcoming), it looks like the unificationist is out of luck. Unless, that is, the unificationist can point to overriding metaphysical considerations, of the sort operative with ‘mammal’, ‘ape’, and ‘person’.

The reason metaphysical considerations were overriding in those cases is that the terms ‘mammal’, ‘ape’, and ‘person’ are used with an intention to refer to a relatively natural kind. The same applies, presumably, to ‘because’, ‘cause’, and ‘grounding’.Footnote 71 But it should now be clear that the unificationist bears the burden of showing that metaphysical considerations force us to unify causal explanation and metaphysical explanation. The linguistic facts make the alternative position—the position that distinguishes them and treats causation and causal explanation merely as the basis for (conventionalized) metaphorical talk of grounding and metaphysical explanation—the view to hold in the absence of countervailing evidence.

This is a burden-shifting argument. We should be clear about why the unificationist properly bears the burden. The case cannot merely rest on differences between the restrictions imposed on relata of the relations.Footnote 72 The fact, if it is one, that grounding is a synchronic relation while causation is a diachronic relation does not establish that they are more than nominally distinct. After all, if there were just one relation—call it ‘generation’—we might just call generation ‘grounding’ when it relates entities at the same time and ‘causation’ when it relates entities at different times.Footnote 73 There is, in general, no reason to think differences in relata reflect metaphysically significant differences in relations. The best case against grounding-causation unity, as I see it, is that it would commit us to implausible semantic equivalences. It is relevant here that we do not say that grounds cause what they ground. Nevertheless, if we use ‘causes’ and ‘grounds’ with the linguistic intention of picking out maximally natural relations, it could turn out that ‘p causes q’ and ‘p grounds q’ mean the same thing. But since intuitively they do not, we have reason to prefer a theory that distinguishes them.Footnote 74

5 Causal explanation in proper perspective

The last point I want to make concerns the relationship between causal explanation and metaphysical explanation. If the causal metaphor account of metaphysical explanations is correct, then causal explanation really is explanation par excellence. Causal explanations are the models for non-causal, metaphysical explanations, and provide the basis on which we understand them. Their centrality to explanation, then, is not just a matter of their importance to science, but of their importance to our explanatory practices as a whole. The semantic investigation of ‘because’ thus brings into focus, in a new way, the conceptual centrality of causal explanation.

Notes

I immediately flout two controversies. First, for ease of exposition, I here follow Rodriguez-Pereyra (2005) and Schaffer (2009) in taking the relation view of grounding—see Trogdon (2013), §3—though in the end nothing turns on it. Second, I ignore, for the time being, questions about the intelligibility and utility of our grounding talk and concepts raised by Hofweber (2009), Daly (2012), and Wilson (2014). A proprietary explanation of their concerns is advanced at the end of Sect. 3.

The paper thus flirts with what Jackson (1998, 42–44) calls “immodest” conceptual analysis. But it only flirts: in particular, I do not appeal to Moorean facts to argue that some metaphysical view is false. I claim merely that annihilating distinctions we actually make is a cost of a theory that does so.

Some theorists (Apresjan 1974; Pustejovsky 1998) understand the relatedness criterion rather in terms of definitional similarities, though this approach has no way of accounting for polysemy in cases where one of a polyseme’s meanings is semantically primitive [see Fodor and Lepore (2002) and the discussion in Rakova (2003, §9.4)].

Rakova (2003, ch. 1) surveys the appearance of this idea in major theories of metaphor since the 1930s. The standard view is not without its critics—including Rakova (2003)—but pursuing the debate would take us too far afield. Suffice it here to say that the arguments Rakova (2003) presents in favor of her “no-polysemy view” for polysemous adjectives do not transfer over to the case of ‘because’.

Derived from Plato, Euthyphro 10a.

The antecedent of a conditional at Fodor and Lepore (2002, 90).

The semantic fact that a single sense of ‘because’ is operative in all of these cases is consistent with Wilson (2014)’s insistence that grounding relations are “united only in name.” See the closing paragraphs of Sect. 3 for the causal metaphor account’s proprietary explanation of grounding skepticism.

See Traugott (1989) for historically documented cases of semantic change that seem best explained by the conventionalization of conversational implicatures rather than by metaphorical processes; Dirven (1985) and Bartsch (2002) for discussions of metaphor and metonymy as productive of polysemy; Fauconnier and Turner (2003) for conceptual blending; and Aitchison and Lewis (2003) for bleaching.

Nerlich (2003) documents this idea—and its widespread acceptance—in early modern figures including Locke and Leibniz.

See Goodman (1968, II.5) and Traugott (1985). Even Davidson, who was famously skeptical about assigning semantic content to metaphors, recognized that dead metaphors yielded ambiguity: see Davidson (1984, 252–253). (Davidson argues that, in dying, the metaphor loses its force. Thus it can fail to occur to us, for example, that ‘table legs’ might once have been evocatively metaphorical.) According to Lakoff and Johnson (1980), who argue that the vast majority of our concepts are metaphorically derived from a sharply limited stock of experiential concepts, conventionalization of a metaphorically extended sense is consistent with the metaphor continuing to live.

Op. Cit., 438.

Hitchcock (2007, 201).

This might sound contentious to readers of the semantics literature for another reason. Lakoff (1970), one of the first presentations of the method employed in Shaheen (forthcoming) to show that ‘because’ is polysemous, applied that method to argue for the recognition of distinct intentional and non-intentional senses of various verb phrases. Mel’čuk (2012, ch. 5) explicitly claims that ‘cause’ is ambiguous between agential and non-agential meanings. But the tests simply don’t support the ambiguity claim.

Cf. Tarski (1944, §14), where it is presupposed that concepts have clear, sharp boundaries despite the vagueness and ambiguity of natural language. Concepts, I think, can be just as indeterminate as the words that express them.

The conceptual waters are muddied here by what are, by my lights, category errors. Hall (2004) borrows the Scholastic and Deleuzian phrase ‘univocal concept’, whereas it is linguistic items (e.g., words) that can be the bearers of univocality and related properties. The category error breeds confusion, as the following list of examples amply demonstrates: Longworth (2006, §4.4) reads Hall (2004) as committed to polysemy; Hitchcock (2007) provides a taxonomy of positions in the causal pluralism debate while taking “the central tenet of causal pluralism to be the claim that ‘cause’ and its cognates have multiple senses” (201); and Godfrey-Smith (2009, §3) criticizes Hall’s two concept view by contrasting our use of ‘cause’ with our use of the polysemes ‘mad’ and ‘funny’.

The causal pluralism literature itself suggests multiple kinds of monosemy accounts, including the ‘amiable jumble’ account of Skyrms (1984) [see also Healey (1994, section VIII)], the thin concept account of Cartwright (1999, 2004) [building on Anscombe (1971)], the epistemic account of Williamson (2006), and the ‘essentially contested concept’ account of Godfrey-Smith (2009). The disjunctive account of Longworth (2010) would seem to qualify as well, though Longworth seems to endorse the inference from plurality of precisfications to ambiguity [see the denial of the ambiguity suggested by Hitchcock (2001) at Longworth (2006), 90 and the assertion that Hall (2004) should be thought of as a polysemy account at Longworth (2006), 93].

To provide some examples not discussed in the text, Sober (1984) and Eells (1991) distinguish (probabilistic) type causation from (probabilistic) token causation. Hitchcock (2001) distinguishes having ‘component’ effects from having ‘net’ effects and claims that causal claims are ambiguous between the two.

These theses are given at Hall (2004, 225).

Counterfactual dependence was thought, from the time of Lewis (1973), to be the heart of an analysis of causation. But simple counterfactual dependence is not, by itself, adequate to the analysis, as cases of overdetermination and preemption show. In fact, preemption also turns out to undermine any hope that distinguishing between production and simple counterfactual dependence yields an exhaustive, if disjunctive, treatment of event causation, as Hall himself recognizes in connection with the escort plane case discussed below.

See op. cit., 255–256, where Hall acknowledges a connection between multiplicity of concepts and ambiguity. He introduces Tim Maudlin’s example of various kinds of biological and adoptive mothers which can be conceptually distinguished despite the apparent univocality of ‘mother’. But rather than taking the opportunity to foreswear any ambiguity claim about ‘cause’ or get clearer about the relationship between conceptual distinctions and ambiguity, he excuses himself from adjudicating the issue.

Op. cit., 269: “Even when you choose to avoid a certain course of action because it would result in your having helped produce the evil deed, the sense of ‘because’ is clearly that of dependence.”

Hall’s conflation of precisifications with senses is not limited to his paper’s main causal plurality claim. Early on, he assumes “that there is a clear and central sense of ‘cause’...in which causes and effects are always events” (op. cit., 227). But this too is a mere precisification of a sense: see Jenkins (2008) on the semantic generality of ‘cause’ with respect to ontological category.

I do not discuss translational evidence because, to my knowledge, none of the distinctions described by causal pluralists have been explored cross-linguistically, though I’d be more than a bit surprised to learn that different languages had different words for, e.g., production and counterfactual dependence. [Kripke (1977) counts that hypothetical surprise as evidence of monosemy, though I would be equally surprised if anyone were bowled over by this kind of evidence.] I also do not discuss reduced conjunctions here, but any reader not convinced by the indicators discussed here may see Shaheen (forthcoming) for a blueprint that could be followed to test ‘cause’.

This example is inspired by the discussion of disambiguation through cooccurring material in Sadock (1972).

Hall himself is open to this possibility (recall fn. 25). Strevens (2013) takes Hall’s invitation to reformulate his view as distinguishing between kinds of causation instead of concepts of causation, and adopts talk of kinds of causation as ways our causal assertions are ‘made true’. See also Leitgeb (2013, §5) for a discussion of explication that treats it as an obviously revisionary project.

Strictly speaking, I should deny that some words are homonymous; only (non-single-membered) pluralities of words can be homonymous. I’ll stick to polysemes in the body for ease of exposition.

For confirmation that disjunctive senses are compatible with monosemy, see Roberts (1984). Roberts argues that the difference between ambiguity and monosemy is the scope of a disjunction.

Philosophers sometimes talk as though people at some point didn’t know—or still don’t know—that ‘jade’ applies to two different substances: see, e.g., Putnam (1975, 160). This is implausible, since jadeite and nephrite are different colors, are found in different places, have different hardnesses, etc.: see LaPorte (2004, 94-100), Hacking (2007), and Oderberg (2007, 164-165).

See Putnam (1975).

The classic social psychology works for the sliver of the causal attribution literature relevant here are Heider (1958) and Kelley (1967). On agents as magnets for causal attribution, see Hart and Honoré (1959) (an entry from the philosophy literature) and Brickman et al. (1975). On temporal order, see Brickman et al. (1975). On the role of normativity, see for example Hilton and Slugoski (1986), Alicke (1992), Knobe and Fraser (2008), Alicke et al. (2011), and Sripada (2012). Note, however, that some philosophers think that at least some of these effects are just performance errors: see Pinillos et al. (2011) and Dunaway et al. (2013).

The terminology (viz., ‘etiological’ and ‘evolutionary’) is due to Weber et al. (2005). Note that what I am calling ‘etiological explanation’ differs from what Salmon (1989, §3.8) calls ‘etiological explanation’. ‘Evolutionary’, for its part, is intended in the sense in which state spaces evolve rather than as a reference to the explanations of evolutionary biology.

The proper definition of ‘causal interaction’, for example, has been subject to much debate. See, e.g., the debate carried across Salmon (1984, 1994, 1997) and Dowe (1992, 1995). Weber et al. (2005), for their part, adopt a definition of causal interaction which has, as a consequence, the ruling out of beliefs as playing an etiological explanatory role for actions, which then requires them to treat such explanations under the heading ‘causal explanations without descriptions of causal interactions’. But, for present purposes, any plausible precisification of ‘causal interaction’ may be employed.

This is a simplification of a definition at Weber et al. (2005, §2.2.4), though my talk of ‘interference’ replaces Weber et al.’s talk of ‘spontaneous preservation’, of which they give a formal definition at §2.2.3.

This is a simplified and generalized version of a definition at Weber et al. (2005, §3.2) of what they call ‘spontaneous evolution explanations’. I drop the spontaneity condition, which would rule out the stock market example I discuss below, as irrelevant for present purposes.

See Strevens (2008, §7.41).

I discuss what cross-linguistic evidence there is for ‘because’ in Shaheen (2014).

Astute readers will have noticed I have avoided the controversial class of equilibrium explanations. The following example, inspired by Sober (1983), is representative of the class.

-

(i)

The sex ratio in many species at reproductive age is 1:1 because any departure from that ratio would induce reproductive advantages for the minority sex.

Unlike the evolutionary explanations discussed in this section, (i) does not proceed by citing an event that set a process in motion. It explains the obtaining of an equilibrium condition by appeal only to laws governing the dynamics of the system in equilibrium. So not only are the causal details of the process leading from some initial conditions to an equilibrium state neglected by such explanations, but even the initial conditions from which the system evolved are neglected by these explanations. Whether such explanations are causal explanations is controversial [Sober (1983) says no; Strevens (2008, §7.41) offers a rebuttal—see Weatherson (2012) for a critical appraisal of its success], but clearly they are only acceptable as answers to indicative ‘why’-questions (as opposed to ‘why should’-questions) if the explanandum actually came about through causal influences connected to the putative explanans. If in the actual world the sex ratio in many species if 1:1 because an omnipotent God made it that way and is keeping it that way, then (i) is false, even if it’s true that, should God stop keeping it that way, forces of natural selection would.

This is something like an argument that equilibrium explanations are causal, although I am uncertain whether it is the causal sense of ‘because’ that covers equilibrium explanations. The judgments that have to be made using my preferred strategies for individuating senses are elusive. For example, since there is no time attached to the explanans phrase, the strategy of checking whether something analogous to (22) is self-contradictory is not open to us. However, if there were a sense of ‘because’ that required any kind of citation of initial conditions or causes, there would be a reading on which (i) is not true even on the condition that the equilibrium explanation is true. I certainly don’t detect such a reading. The question is actually of some independent interest, since what it takes for an explanation to count as a causal explanation is itself a matter of some controversy: compare the comments about trivializing the notion of causal explanation at Sober (1983, 202–203) with Skow (2013). It would not be entirely unwelcome to have a demonstration that the ‘because’ of (i) is not the causal ‘because’ of (19), (20), and (21). But the uncertainty here does not affect anything substantive in this paper. It’s possible for polysemes to have more than two senses, and it’s also possible that the metaphorical sense of ‘because’ that covers metaphysical explanations will turn out to cover equilibrium explanations (as well as, it may turn out, other explanations of or by laws).

-

(i)

Even the possibility of giving any precise specification of the metaphorical content is controversial: Davidson (1984) famously argued that the literal meaning of a metaphor is the literal meaning of the words contained in it, and that any apparent metaphorical content is merely a matter of thoughts provoked in us by the metaphor.

See op. cit., ch. 11. A cognitive linguist might also identify additional metaphors at work in our grounding talk: op. cit., ch. 4 discusses a collection of so-called orientational metaphors (things like happy is up; sad is down), and one might do well to consider the juxtaposition causation is back (as in backwards in time); grounding is down (as in towards the fundamental).

Here see Audi (2012, §VI) for dissent about whether this sentence can express a grounding claim.

Garner’s Modern American Usage even deems ‘in virtue of’ archaic: see Garner (2009, 845). I think its use is limited to legal, philosophical, and theological contexts.

Again, I have in mind Bennett, Schaffer, and A. Wilson.

Op. cit., 51.

The friend of precise meanings will object: but the formalism gives precise content to grounding claims! But on my view the collection of paradigm cases gives the content, and those who do not cotton on are being given a causal metaphor as an aid to their understanding.

Of course, if grounding is really a primitive, no real definition will be forthcoming. But then grounding skepticism should be no surprise, given the plausibility of our being able to interpret it only via a metaphor.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for Philosophical Studies for encouraging me to consider more fully the material of the next two paragraphs.

For Wilson, the small-g grounding relations (parthood, the determinate-determinable relation, etc.) are metaphysical dependence relations, while for Koslicki they merely induce metaphysical dependence relations.

In separate works-in-progress, I argue for all of these claims, as well as two others that I can only briefly mention without explanation here. The first is that the polysemy I establish in Shaheen (forthcoming) sets things up very nicely for the partisan of Hofweberian egalitarian metaphysics to give an egalitarian treatment of grounding, according to which there are no metaphysical explanations. (This is not the approach taken by Hofweber (2009), but I argue that it should have been.) The second is that the causal metaphor account of metaphysical explanation leads to a novel argument for grounding skepticism, which builds on Trout (2002, 2007) to cast doubt on the trustworthiness of the sense of understanding appealed to, in one way or another, by grounding theorists.

See Kripke (1980, 138). Dupré (1993, 2006) and LaPorte (2004, 2010) claim that meanings do change in cases like this. According to LaPorte, for example, what Putnam, Kripke, and others would consider discoveries are in fact merely occasions for scientists to make decisions about how to stipulate meanings. This strikes me as neglecting the role of semantic intentions: if what we are trying to pick out with our use of a word is something scientifically natural, then indeed we can discover its intension to be something other than what we might originally have taken it to be. See here Putnam (1975) and Burge (1979). But LaPorte does seem to have a point with respect to certain identity statements, like ‘water = \(\hbox {H}_2\hbox {O}\)’: whether or not we count heavy water (\(\hbox {D}_2\hbox {O}\)) as water is plausibly a matter of deference to stipulation by experts. The same goes for what we count as a planet.

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S._(2014), at 20. Internal citation omitted.

Ibid., at 19. Internal citation omitted.

See Moby Dick, Ch. 32 for the spurning and invoking, and Hirsch (2005, 94–95) for discussion. Thanks to Gordon Belot for pressing me on the relationship between my claims about ‘because’ and how we learn about fish, with apologies for the possibility that the approach may have turned out to be just what he feared.

Manley (2014) puts this point in terms of more or less provisional referential intentions.

It seems implausible that some underlying neurobiological similarity will unify the physical and psychological senses of these words, though Rakova (2003, Chs. 5–6 and pp. 148–149) takes an opposing view. But note that the distinctness of physical sweetness and psychological sweetness would withstand the discovery of such a similarity.

Perhaps only in virtue of our tacit quintessentialism, our implicit belief in the existence of objective joints of nature, which can be (and often are) directly reflected in our thought and talk: see Leslie (2013).

We might also call identity ‘numerical identity’ when it relates numbers and ‘botanical identity’ when it relates plants, but nothing follows about the primitives to which our metaphysical theory should be committed.

Wilson (2013), the prime example of a unificationist, argues that accepting the identity ‘grounding = metaphysical causation’ has simplicity on its side. The adherent of Wilson’s view needs fewer primitive notions than the metaphysician who would introduce separate primitive notions to account for grounding. Whether the simplicity achieved by accepting the identity outweighs the cost of its semantic violence is, in my view, an open question.

References

Aitchison, J., & Lewis, D. M. (2003). Polysemy and bleaching. In B. Nerlich, Z. Todd, V. Herman, & D. D. Clarke (Eds.), Polysemy: Flexible patterns of meaning in mind and language (pp. 254–265). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Alicke, M. D. (1992). Culpable causation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 368–378.

Alicke, M. D., Rose, D., & Bloom, D. (2011). Causation, norm violation, and culpable control. Journal of Philosophy, 108(12), 670–696.

Anscombe, G. E. M. (1971). Causality and determination: An inaugural lecture. London: Cambridge University Press.

Apresjan, J. D. (1974). Regular polysemy. Linguistics, 12(142), 5–32.

Audi, P. (2012). Grounding: Toward a theory of the in-virtue-of relation. The Journal of Philosophy, CIX(12), 685–711.

Ayer, A. J. (1940). The foundations of empirical knowledge. New York: Macmillan.

Bartsch, R. (2002). Generating polysemy: Metaphor and metonymy. In R. Dirven & R. Pörings (Eds.), Metaphor and metonymy in comparison and contrast (pp. 49–74). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bennett, K. (2011). Construction area (no hard hat required). Philosophical Studies, 154, 79–104.

Bennett, K. (Forthcoming). Making things up. Oxford University Press.

Brickman, P., Ryan, K., & Wortman, C. B. (1975). Causal chains: Attribution of responsibility as a function of immediate and prior causes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32(6), 1060–1067.

Burge, T. (1979). Individualism and the mental. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 4(1), 73–121.

Carnap, R. (1931). Überwindung der Metaphysik durch logische Analyse der Sprache. Erkenntnis, 2(1), 219–241.

Cartwright, N. (1999). The dappled world: A study of the boundaries of science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cartwright, N. (2004). Causation: One word, many things. Philosophy of Science, 71(5), 805–819.

Caterina, M. J., Schumacher, M. A., Tominaga, M., Rosen, T. A., Levine, J. D., & Julius, D. (1997). The capsaicin receptor: A heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature, 389, 816–824.

Clapham, D. E. (1997). Some like it hot: Spicing up ion channels. Nature, 389, 783–784.

Cohen, L. J. (1993). The semantics of metaphor (chap. 4) in Ortony, A. Metaphysics and thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Daly, C. (2012). Scepticism about grounding (chap. 2) in Correia, F., & Schnieder, B. Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality (pp. 81–100). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davidson, D. (1984). What metaphors mean (pp. 245–264) in Davidson, D. Inquiries into truth and interpretation. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Dirven, R. (1985). Metaphor as a basic means for extending the lexicon (pp. 85–119) in Paprotté, W., & Dirven, R. The ubiquity of metaphor: Metaphor in language and thought. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Dowe, P. (1992). Wesley Salmon’s Process theory of causality and the conserved quantity theory. Philosophy of Science, 59(2), 195–216.

Dowe, P. (1995). Causality and conserved quantities: A reply to Salmon. Philosophy of Science, 62(2), 321–333.

Dunaway, B., Edmonds, A., & Manley, D. (2013). The folk probably do think what you think they think. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 91(3), 421–441.

Dupré, J. (1993). The disorder of things: Metaphysical foundations of the disunity of science. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dupré, J. (2006). Humans and other animals. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Eells, E. (1991). Probabilistic causality. Cambridge studies in probability, induction, and decision theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eklund, M. (2002). Inconsistent languages. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, LXIV(2), 251–275.

Eklund, M. (2005). What vagueness consists in. Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition, 125(1), 27–60.

Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. (2003). Polysemy and conceptual blending. In B. Nerlich, Z. Todd, V. Herman, & D. D. Clarke (Eds.), Polysemy: Flexible patterns of meaning in mind and language (pp. 79–94). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Fodor, J. A. & Lepore, E. (2002). The emptiness of the lexicon: Reflections on Pustejovsky (chap. 5) in Fodor, J. A., & Lepore, E. The compositionality papers pp. 89–119. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garner, B. A. (2009). Garner’s modern American usage (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.