Abstract

In this paper, after clarifying certain features of Gideon Rosen’s Modal Fictionalism, I raise two problems for that view and argue that these problems strongly suggest that advocates of a “Deflationist Strategy” ought not to endorse, or adopt Rosen-style Modal Fictionalism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many philosophers are uncomfortable with the very notion, let alone accepting the existence, of possible worlds. At the same time, however, they recognize the benefits of the possible-worlds analysis of modal discourse.Footnote 1 In particular, they appreciate the rigor and clarity that this analysis brings to an otherwise complicated and unclear way of talking. While the concreteness or “worldliness” of so-called possible worlds is a matter of debate, it is widely accepted that the quantification over possible worlds that this analysis of modal discourse involves brings with it an ontological commitment to some kind of entity, picked out with the expression ‘possible worlds’. While David Lewis has argued mightily for what he (1986) calls modal realism—the view that possible worlds should be understood as separate, individual, concrete universes that are as fully genuine and realized as the cosmos we inhabit—many find this view of possible worlds (as opposed to the view that the things modal discourse involves quantifying over are abstract, complex properties or “world-natures”, only one of which, that of the actual world, is instantiated) to be especially worrisome, ontologically speaking.Footnote 2 Many, however, maintain that Lewis has made the case that modal realism wins the contest with what Lewis calls “modal ersatzism” (and others call “abstractionism” or, sometimes, “actualism”).

In developing his modal fictionalism, Rosen (1990) begins with the supposition that, in the debate over the nature of possible worlds, Lewisian modal realism wins the argument. Thus, if one wants to reap the benefits of the possible-worlds analysis of modal discourse, Rosen is assuming that, prima facie, one must take on an ontological commitment to a plurality of concrete cosmoi over which we quantify, when we engage in modal discourse. What Rosen aims to investigate, then, is the extent to which one can preserve the advantages of the possible-worlds analysis without incurring the ontological costs that appear to come from accepting that analysis. He (Ibid., p. 330) calls any approach that attempts to attain this sort of benefit-without-the-costs status a deflationist strategy (henceforth, DS). Rosen (Ibid.) notes that, according to a DS regarding possible-worlds-talk,

[Y]ou can have all the benefits of talking about possible worlds without the ontological costs. You can legitimately say in one breath (perhaps in the course of explaining what you mean by some modal claim) ‘there is a world where blue swans exist’ and in the next breath; ‘but really, I don’t believe in possible worlds’.

Let us say that an advocate of DS regarding possible-worlds-talk is one who seeks a means for assertorically uttering modal claims understood according to the possible-words analysis, without being ontologically committed to possible worlds. Rosen’s modal fictionalism (henceforth, ‘MFR’) is put forward as a proposed DS, viz., as a means for allowing speakers to engage in—that is, to employ—possible-worlds-talk without the apparent ontological costs of doing so.Footnote 3 In what follows, after clarifying certain aspects of MFR, I pose two problems for that view. If these problems compel, then advocates of DS ought not to endorse, or adopt, MFR.Footnote 4

1 Rosen’s assumption of a Lewis-style philosophy of fiction

For an advocate of MFR (henceforth, an ‘MFRist’), a modal sentence like

- (0)

There might have been blue swans.

should be analyzed (initially) in terms of a sentence that quantifies over possible worlds, specifically,

- (1)

There is a (non-actual) possible world, w, such that, in w, there are blue swans.Footnote 5

Rosen’s DS proposal begins with the claim that (1) should be understood by analogy with how.

- (2)

There is a brilliant detective at 221b Baker St.

is understood. That is, according to MFR, the instances of possible-world-talk should be understood by analogy with how certain overtly fictional sentences are understood.

As Rosen notes (Ibid., p. 331), taken at face value, (2) is straightforwardly false and “anyone who asserts it with the intention that it be so understood speaks falsely.” However, he (Ibid.) claims that when participants are mutually aware that the topic is a certain body of fiction, assertoric utterances of (2) will be read as an elliptical rendering of something like

- (3)

According to the Holmes stories, there is a brilliant detective at 221b Baker Street.

For those who are aware that the Holmes stories are just that—stories—an assertoric utterance of (2) is not taken at face value. This has an important consequence for, as I will show, if (2) is taken to be an elliptical rendering of (3), then we have some reason for thinking that (2) is about the Holmes stories and that it is not about a brilliant detective (or 221b Baker Street). In what follows, I motivate this claim about what (3) [and, thus, (2), if it is taken to be an elliptical rendering of (3)] is, and is not, about.

Before providing some reasons for thinking that (3) is about the Holmes stories and that it is not about a brilliant detective (or a place, 221b Baker Street), it is important to note that I am not taking a stand as to whether works of fiction, generally, are about the things that they purport to be about. I have no stake in the debate as to whether if (2) is not an elliptical rendering of (3), it ends up being about a brilliant detective (or a place, 221b Baker Street). What I will show is that there is good reason for taking a face-value reading of a sentence like (3)—viz., one that does not involve a de re reading of that sentence—not to be about such things. But—and this is important—I am not taking a stand on whether (2) is, or should be viewed as, an elliptical rendering of (3). Hence, I am not taking a stand on what non-story-prefix-involving sentences of fictional discourse are about. This is not because I am not interested in the topic. It is because it is orthogonal to what my paper is concerned with, viz., whether we should or should not endorse MFR.

In order to motivate the claim that (3) is about the Holmes stories and is not about a brilliant detective (etc.), let us consider a sentence that does not involve fictional discourse at all, e.g.,

- (3*)

According to Becher’s theory, phlogiston is released during combustion,

where (3*) does not involve a de re reading of that sentence, and ask what that sentence, or an assertoric utterance of that sentence, is about. It seems unequivocal that a face-value (thus, non- de re) reading of (3*) is about Becher’s theory to the effect that, according to it, to the theory, phlogiston is released during combustion. Thus, I do not think that anyone will disagree with the claim that (3*) is about Becher’s theory. (Analogously, I do not think that anyone will disagree with the claim that (3) is about the Holmes stories.) But, although it seems clear that (3*) is about Becher’s theory, it may still seem that something is about phlogiston (and, perhaps, combustion). Should we therefore say that, while (3*) is about Becher’s theory, it is also about phlogiston (and, perhaps, combustion)? I think not.

In fact, we can motivate the claim that a face-value reading of (3*) is about Becher’s theory, rather than being about what his theory is about, by noting the following distinction [and mutatis mutandis for the thought that a face-value reading of (3) is about the Holmes stories, rather than being about a brilliant detective (or 221b Baker St.)].Footnote 6 The distinction is between what a theory is about (or, in any case, purports to be about) from what a statement of a theory is about. A statement made from within Becher’s theory may be about (or, in any case, may purport to be about) phlogiston (or, again, combustion). For a statement made from within a theory is about what the theory is about. But a statement like (3*) is not made from within Becher’s theory; it is made from outside of that theory and is a statement regarding that theory. And it seems clear that a statement regarding a theory that is made from outside of a theory is about that theory, and that it is not about what that theory is about.

There is a further consideration that is relevant, once we have distinguished statements made from within a theory from statements made about that theory. The consideration involves the theory-prefix operator, which is modeled on Lewis’s story-prefix operator. Lewis’s story-prefix operator provides a means whereby an assertoric utterance of (3) can be true without committing its assertoric utterer to the existence of fictional characters. This latter feature is possible because the sentential operator, ‘According to the fiction F, …’, is non-factive, meaning that ‘According to the fiction F, φ’, does not entail ‘φ’.Footnote 7 This has an important consequence, owing to the fact that this is an intensional operator. The upshot of such an operator is that, from an assertoric utterance of (3*), one cannot infer that there is any phlogiston (or that there is combustion). Thus, when we assertorically utter such a sentence, we do not commit ourselves to those things. The intensionality of that operator further ensures that an assertoric utterance of (3*) can be true, even though there is no phlogiston. By contrast, when we assertorically utter (3*), we do commit ourselves to Becher’s theory and, what’s more, it is clear that if there was no such theory as “Becher’s theory”, then an assertoric utterance of (3*) could not be true. These considerations further support the claim that (3*) is about Becher’s theory and that it is not about phlogiston.

Although I believe that the considerations presented above adequately support the claim that (3*) is about Becher’s theory, rather than being about what that theory is, or purports to be, about, I think that we can go further. If we let Becher’s theory be a set of sentences,Footnote 8 then, given the points made above, we can say that (3*) is about those sentences. Thus, when we add the theory-prefix operator to ‘Phlogiston is released during combustion’, we get a sort of semantic ascent, making the resulting sentence about the sentences that comprise the theory, rather than about what the original, non-theory-prefix operator involving sentence is, or purports to be, about.Footnote 9

I would say something similar about (3). On a face-value reading of (3), it is about the Holmes stories and is not about what the stories purport to be about—to wit, a brilliant detective (or 221b Baker Street). And if the Holmes stories, like Becker's theory, can be construed as a set of sentences, then adding the story-prefix operator to (2) [to yield (3)] results in a sort of semantic ascent, so that (3) is about the sentences that comprise the Holmes stories, rather than what at least some of those sentences purport to be about. Thus, reading (2) as (3) shifts, or changes, the topic of the sentence so that, rather than being about brilliant detectives or a place, the sentence is about the Holmes stories, since that is what (3) is about. In short, understanding (2) in terms of (3) involves redirecting the content of (2), so that the sentence is about the content of the Holmes stories.Footnote 10 Thus, on this sort of “prefix” analysis of discourse about fiction, it follows that, when one assertorically utters (3), one says something about the Holmes stories. This is a virtue of the resultant semantic redirection that results from reading (2) as (3).

Rosen’s proposal for MFR is to model an account of possible-worlds-talk on such a Lewis-style philosophy of fiction, in an attempt to garner benefits similar to those that Lewis’s “prefix” analysis of discourse about fiction attains.Footnote 11 In order to provide such an account, viz., of how the possible-worlds analysis of modal claims should be understood, Rosen (1990, 1995) returns to modal realism, as developed by Lewis (1986). On the Lewisian sort of modal realism with which the developers of MFR are concerned [and here I mean, in particular, Rosen (1990, 1995), Liggins (2008), and Woodward (2008, 2010)], a modal sentence like (0) is meaning equivalent to a possible-worlds sentence like (1). As a result, the acceptance of (0) will carry with it a commitment to possible worlds, just as an acceptance of (1) does.

Lewis (Ibid.) put forward his theory of possible worlds as the literal truth. But, for an anti-realist about possible worlds, Lewis’s theory is simply false. Rosen’s proposed DS, MFR, is to treat a slightly modified version of Lewis’s theory of possible worlds as the fiction that underwrites modal discourse. This new theory, which Rosen (Ibid., p. 335) dubs ‘PW’, consists of

- (i)

a set of Lewis’s postulates, which “are meant to capture … the ontological core of Lewis’s modal realism”,Footnote 12 and

- (ii)

an encyclopedia, which is a list of the non-modal truths about the intrinsic character of the universe.Footnote 13

So understood, PW is MFRist’s fiction.

In order to illustrate MFR, consider a modal claim like (0), which a modal realist will take to be equivalent to (1). Now, while an advocate of MFR will not accept a reading of (0) on which it means the same thing as (1), according to Rosen, she will accept a reading of (0) on which it means something like

- (4)

According to PW, there is a world, w, such that, in w, there are blue swans.

Rosen’s proposal for MFR is that (0) should be understood as an elliptical rendering of (4), thereby redirecting the content of (0) so that it is now about the theory, PW. Thus, on analogy with a Lewis-style fictionalist treatment of (2), an MFRist will paraphrase uncontroversial true (false) modal statements with similarly uncontroversial true (false) statements about the content and consequences of the theory PW. By trading on the benefits of Lewis’s fictionalist account of overt fiction, the MFRist aims to retain the benefit of engaging in modal talk without the otherwise worrisome ontological commitments. And she aims to do this by proposing a reading of modal claims that renders them true (or false), though, again, without any ontological commitments to possible worlds.

2 MFR—revolutionary or hermenuetic?

The central feature of MFR is that sentences that appear to be about possible worlds should be read as elliptical renderings of sentences that are not about possible worlds at all. There are various senses in which the relevant rendering of an explicitly modal sentence can be said not to be about possible worlds. For example, Rosen (1990) maintains that, for an MFRist, a sentence like (4) should provide the truth conditions for (0), and should be a paraphrase of (0). By contrast, Liggins (2008) states that while, for the modal realist, a sentence like (0) means (1) (that is, it means what (1) means), for an MFRist, a sentence like (0) means (4). And Woodward (2008, p. 277) contends that “the core of modal fictionalism is a claim regarding which propositions are expressed by modal sentences.” He (ibid.) continues: “the [MFRist] holds that sentences [like (0)] that apparently quantify over possible worlds express true propositions regarding the content of [PW].”

Now, before turning to worries about this view, there is one wrong that needs to be righted. Like Rosen, Liggins and Woodward take themselves to be extending and defending, though in neither case explicitly endorsing, their favored version of MFR. But, in fact, there is an important difference between what Rosen officially proclaims and what Liggins and Woodward do. The issue turns on whether the trio sees MFR as revolutionary or hermeneutic. For our purposes, the difference between these two species of the genus, philosophical fictionalism, is this.Footnote 14

Revolutionary fictionalism is a prescriptive enterprise. It tells us how some putatively problematic discourse should be understood and how it will be understood, come the revolution, e.g., when people come to realize that there are no possible worlds and that the modal sentences they go about uttering don’t have to be ontologically committing in the way that they appear to be on our best analysis of them. Accordingly, while revolutionary fictionalists maintains that some discourse really is problematic, they also claim that it does not have to be problematic and maintain further that it can be made unproblematic, provided its aim is changed.

By contrast, hermeneutic fictionalism is a descriptive enterprise. It tells us how some discourse, as uttered or accepted by ordinary speakers, actually is to be understood. Accordingly, hermeneutic fictionalists take apparently problematic discourse to be unproblematic on grounds that it never had a problematic aim.

For our purposes, if treated as revolutionary, MFR dictates that, although modal discourse actually is problematic, in that modal sentences are uniformly false (their negations, thus, true), it does not have to be problematic, and will not be problematic, come the revolution, given how the discourse should be understood. By contrast, a hermeneutic reading of MFR will read fictionalism into our actual use of modal discourse. According to them, standard uses of modal discourse already are fiction-involving and, thus, do not commit its assertoric utterers to possible worlds.

Although neither Liggins nor Woodward make explicit whether they see MFR as hermeneutic or revolutionary, what they say, about the sort of MFR that they describe, seems to commit them to a hermeneutic reading. Here’s why.

As noted, above, Liggins (Ibid.) claims that an advocate of MFR will take (0) to mean what (4) means. And Woodward contends that such an advocate takes a sentence like (0) to express a true proposition regarding the content of PW.Footnote 15 Now, since any MFRist thinks that her view is correct, on Liggins’s and Woodward’s views, about how we ought to understand MFR, MFRists are not merely claiming that (0) (or modal claims, more generally) should, in the future, be understood to mean what (4) means (or, in Woodward’s case, should, in the future, be understood as expressing the proposition that (4) expresses); rather, they are claiming that it already does mean what (4) means (or already does express the proposition that (4) expresses). It is for this reason that I take Liggins and Woodward to be committed to the view that MFR is hermeneutic, rather than revolutionary.

What is puzzling about this is that for Rosen the central claim of MFR is not about how modal claims are understood; it is about how modal claims should be understood. This is clear, for example, when he (Ibid., p. 332) says that when MFRists assertorically utter something like (0), what they really mean to assert is (something like) (4). But this is not how (0) is currently construed; it is how it should be construed and, presumably, how it will be construed, come the revolution. Accordingly, contrary to what Liggins and Woodward imply, Rosen’s brand of modal fictionalism is best construed as revolutionary, for, or by, those who would deny the existence of possible worlds without giving up the benefits of the possible-worlds analysis of modal discourse.

I think that while Liggins and Woodward would admit that, given what they have said, they are treating MFR as hermeneutic, rather than as revolutionary, they would probably add that this was not really their intention, since MFR, understood as Rosen does, is clearly revolutionary and is not hermeneutic. They then might go on to claim that, since their intention was to defend MFR, in retrospect, what they really intended was to provide a variant of Rosen-style modal fictionalism, which is revolutionary, not hermeneutic.Footnote 16

Whether that is correct or not, in what follows I will read MFR as Rosen does, viz., as revolutionary, rather than hermeneutic. On Rosen’s view, although the truth conditions for (0) are those provided by (1), thereby rendering (0) (and, indeed, all such modal sentences) false, which is in line with revolutionary fictionalism, as traditionally understood, come the revolution, (0) will have, because it should have, (4) as providing its content. In that case if, as Rosen (Ibid.) contends, (4) is straightforwardly true, then (0) will, likewise, be straightforwardly true.

3 A problem with the MFR equivalence claim

My first problem for MFR regards one of its most central features. To see the problem, consider

- (5)

There might have been flying pigs,

which, come the revolution, will be read as

- (6)

According to PW, there is a world, w, in which there are flying pigs.

Now, like (0), we are assuming that, however, ultimately, (5) should be read, pre-theoretically speaking, advocates of DS will accept that modal claim. Accordingly, insofar as MFR dictates that (5) should be read as (6), they will only accept MFR if their acceptances are preserved, which is to say: They will only accept MFR if they will accept the proposed reading of (5), viz., what is expressed by (6). If they accept (5) but will not accept (6), then they will deny that (5) should be read as (6), in which case they will not accept MFR. The question that presses is whether advocates of DS will, or should accept (6), given their acceptance of (5).Footnote 17

Rosen (1990, p. 336) contends that they will. According to him, it should be utterly uncontroversial that a sentence like (6) is true; indeed, he (Ibid.) claims that “no one should doubt that [(6)] is true.” Rosen’s confidence in the truth and acceptability of (6) notwithstanding, as I will show, there is good reason for thinking that we should not accept (6). This is not to say that we should reject (6). But, as I will show, we do not have to provide reasons for rejecting (6), in order to establish that we ought not to accept it, and, thereby, that we would not (or should not) endorse MFR.

According to Rosen (ibid., p. 335), something like (6) will be true because, given what is stated in the encyclopedia, together with recombination, the theory, PW, will generate a world in which there are flying pigs. But it is not entirely clear how the theory will do this. The principle of recombination allows that any two (or more) things that exist in the actual world can be patched together in a single world in any arrangement that shape and size permits. In the simplest case, we generate a world in which there are horned horses, by recombining a horn and a horse. This can be done because the encyclopedia will report the existence of horses and horns and thus recombination will allow us to infer a possible world in which there are horned horses. But that some animals fly and that there are pigs does not, through recombination, imply the existence of a world with a flying pig (anymore than patching together some fish and the legs of some humans will inevitably result in walking fish). This is not to say that (6) will be false; it is merely to note that we will have to look elsewhere, if our goal is to generate a world in which there are flying pigs.

Just patching together wings and pigs does not imply the existence of a world in which there are flying pigs. Fortunately, there seems to be a more promising means for achieving this goal. Rather than applying recombination at the macroscopic level, patching together macroscopic objects (like wings and pigs, or fish and people legs), recombination will (or, perhaps, should) take place at the microscopic level—at the genetic, or the atomic, level, perhaps regarding the altering of the DNA sequences of pigs and (or) the recombination of fundamental particles.

The idea might be something like this. We know enough geometry to know that the motion of a flying pig can be described using a Cartesian coordinate system and a finite number n of arbitrarily small pieces of matter. Suppose then that for the n pieces of a pig in the actual world, duplicates are then recombined and assigning to the appropriate coordinates, resulting in flying pigs. That is, we bring together duplicates of very small things, in order to form what would be a flying pig.

The thought, then, is that PW would entail a given sentence about these small objects in the appropriate coordinates. Call the sentence ‘FP1’. Although it’s not obvious that PW would entail such a sentence (because the relevant postulate fails to say that duplicates can be patched together in arbitrary spatial arrangements), let’s leave that worry aside. The challenge, for the MFRist, is to ensure that PW tells us that whenever a world contains certain recombinations of stuff of the afore noted sort, it contains a flying pig. My claim is that this challenge will not be met. Even if, through recombination, we get that there is a world at which a microphysical sentence like FP1 is true, that alone is not sufficient to ensure that there are flying pigs at that world. We will also have to build into PW that whenever FP1 is true, there are flying pigs. But it’s not clear how to build these things, these laws. Such “micro–macro connection laws”—laws that connect the micro with the macro realms—are prima facie metaphysically necessary, so we do not get them in via the encyclopedia. Moreover, since neither Rosen nor anyone else knows exactly what these laws will be, they cannot be built into PW explicitly. Now, these last considerations might suggest that Rosen will have to accept that it is not true in PW that there is a world with flying pigs, which would render MF materially inadequate. But I do not want to make such a strong claim. Rather, my claim is that, in light of the above considerations, even if we were to grant that there is a world at which FP1 is true, according to PW, we would still not know whether PW generates a world in which there are flying pigs. That is, we (and, thus, advocates of DS) do not know how (or: whether), given the resources available to Rosen, PW will generate a world in which there are flying pigs. So, advocates of DS would not (and should not) believe, or accept, that, according to PW, there is such a world. Again, this is not to say that they should reject the claim that there is such a world (according to PW). Rather, the proper stance to take seems to be something like agnosticism, since they do not know how or, indeed, whether, PW generates such a world. Thus, they would not (or, again, should not) accept (6).Footnote 18 But it seems that they do accept (5).Footnote 19 Thus, advocates of DS will not (or should not) want (5) to be read as (6).Footnote 20

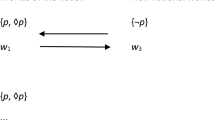

According to MFR, where P is an arbitrary modal claim and P* is the modal realist’s non-modal paraphrase of P in the language of possible worlds, while MFRists will neither accept nor assert instances of the schema,

(ES) P iff P*,

according to Rosen (1990, p. 332), they will accept and assert instances of the schema,

(ES*) P iff According to PW, P*,

for pretty much every P that the modal realist will accept. But now we have a problem.

Advocates of DS will accept, and will want to be entitled to assertorically utter, a modal claim like (5). MFRists propose that (5) is to be read as (6). As we have seen, advocates of DS would not (or, at least, should not) accept (6) and, thus, would not (or should not) accept the relevant instance of (ES*). But the situation with respect to (6) is not novel (Indeed, the same worry appears to arise for (4).Footnote 21). Hence, we are entitled to conclude that advocates of DS would not (or, again, should not) accept the instances of (ES*). Insofar as that is a central feature of MFR, it follows that they will not (or should not) adopt, or endorse, MFR.

4 MFR and the Aboutness Problem

The second problem for MFR is what I call the “Aboutness Problem”. In order to get to the problem, let us return to Lewis’s treatment of overt fiction.

One of the reasons for thinking that an overtly fictional sentence like (2) should be taken to be an elliptical rendering of (3) is that it gets the “aboutness” of the sentence right as well as, perhaps more importantly, getting our use of that sentence right.Footnote 22 When one is fully aware of the fact that a sentence like (2) is overtly fictional—that is, that it pertains to the Holmes stories—then, when she assertorically utters (2), her aim is to say, or convey, something about the Holmes stories. Her aim it is not—or, at least, certainly need not be—to say, or convey, something about brilliant detectives or a place, 221b Baker Street. And if we apply the (intensional) story-prefix operator to (2), thereby reading it as something like (3), the result is that the sentence is about the Holmes stories. Hence, reading (2) as (3) appears to deliver the right results.Footnote 23

As noted previously (Sect. 1), Rosen assumes that (0) is meaning equivalent to (1) and, thus, that when ordinary speakers assertorically utter (0), they say something about (and, for so doing, are committed to) possible worlds. But it does not follow from this that when ordinary speakers assertorically utter (0), what they aim to convey is something about possible worlds.Footnote 24 An advocate of DS, for example, while she does not accept possible worlds, might nevertheless feel compelled to assertorically utter something like (0) because of something else that it enables her to convey. So, it might end up that in order to convey something about, for example, swans or a swan property (or, perhaps more broadly, reality), our advocate needs to use vocabulary that commits her to possible worlds. But her reason for assertorically uttering what she does need not be to say, or convey, something about possible worlds. Rather, it is because of the other things that a modal sentence like (0) is about that our advocate has an interest in assertorically uttering that sentence in the first place. Indeed, if (0) were not (at least) about swans or a swan property (or reality), it would be an utter mystery as to why an advocate of DS would wish to assertorically utter, much less accept, that sentence. Since such advocates do wish to assertorically utter (0), but they do not accept possible worlds, it seems that their reason for assertorically uttering (0) must be to say, or convey, something about swans or a swan property (or, again, reality). But now we get a problem.

If (0) is read as (4), it is about PW. But this is not what advocates of DS want. While they do not want to be committed to possible worlds, as we have seen, they do want to be able to say something about swans or a swan property (or reality). However, if (0) is read as (4), this seems to be something that they cannot do. Since advocates of DS who accept, and wish to assertorically utter, (0) aim to say, or convey, something about swans or swan properties (or reality), if (0) is read as (4), their aims will be thwarted. In fact, from the perspective of an advocate of DS, the impetus for assertorically uttering (0) will be lost, for a face-value reading of (4) is no more about swans or a swan property (or reality) than a face-value reading of (3) is about brilliant detectives (or 221b Baker Street).Footnote 25 Hence, advocates of DS will not want to read (0) as (4) and, for so doing, will not want to embrace, or adopt, MFR.

The revolutionary aspect of MFR proposes a semantic redirection for modal discourse. Rather than being about possible worlds, the proposal is that modal sentences be about the theory, PW. The proposed solution to the problem that modal discourse presents appears to fulfill one of Rosen’s chief aims, as it appears to preserve the truth (falsity) of modal sentences that we take to be true (false) without thereby committing those who assertorically utter such sentences to an ontology of possible worlds. But the proposed redirection cordons off too much. Adopting MFR therefore appears to undermine one of the primary reasons for looking to MFR (or some other fictionalist account) in the first place. Rosen presented MFR as a way of implementing the deflationist strategy. What we have found is that this way of implementing that strategy fails. Thus, MFR appears to be plagued by the Aboutness Problem.

4.1 First response to the Aboutness Problem

One possible response to the Aboutness Problem takes off from Lewis’s (1986) response to an objection by Kripke (1980), as against counterpart theory, and Rosen’s (1990) related response to the “problem of concern”. Here is the response.

To be sure, for an advocate of DS, the impetus for assertorically uttering (0) is to say, or convey, something about swans or a swan property (or reality), and she has no particular interest in conveying something about PW. But if she accepts MFR then perhaps she will come to realize that part of what she aims to convey, when she assertorically utters (0), is about PW. That is, she will come to accept that a revision is required and, as a result, she may come to believe that she now wants to convey something that is about PW.

This may well be true, as a matter of psychological fact. That is, our advocate may recognize that it is in her interest for (0) to be read as (4) and, thus, may come to believe, or accept, that when she assertorically utters (0), she does aim to convey something about PW. But this will not solve the present problem for, while she might come to want to say something about PW, she will still want to say something about swans or a swan property (or reality) and, given a face-value reading of (4), if (0) is read as (4), this is something that she cannot do.

Lewis’s (1986) response to Kripke’s (1980) argument is that once one takes counterpart theory to heart, one might find that she develops a concern for distant strangers. And, as Rosen (1990) employs the response, with respect to the argument from concern, the thought is that once one accepts MFR, one might, or will, come to think that truth in the fiction, PW, is important. In both of these cases, the idea is that once one embraces the relevant position, one might then change her views about what matters, in which case the problems with the respective positions will appear to dissolve. The going thought seems to be that, having embraced Lewisian Modal Realism or MFR, one can, or will, develop a new attitude.

Again, this may be so. But it does not address the current point. After all, even if an advocate of DS comes to believe that she wants to convey something about PW, that alone does not keep her from also wanting to convey something about swans or a swan property (or reality). Hence, while Lewis’s response might adequately resolve Kripke’s worry, and Rosen’s (1990) response to the “argument from concern” might adequately resolve that worry, the same sort of consideration does not undermine the Aboutness Problem, for, in both cases, Lewis’s and Rosen’s, the going response involves developing a new attitude; it does not involve shedding a former one.

4.2 Second response to the Aboutness Problem

When presented with the Aboutness Problem, one tempting solution, advocated by Rosen (personal communication), is to propose a de re reading of the MFRist’s restatement of (0) (and, indeed, modal claims more generally), thereby ensuring that the sentence is about what, intuitively, it appears to be about. This is a reasonable response and, if it could be made to work, it might well recover the aboutness of (0), in which case it might resolve the Aboutness Problem.Footnote 26 But can this solution be made to work? As I will argue, below, although the solution can be made to work, it raises further problems for MFR.

In order for this proposal to work, an MFRist must find an acceptable candidate re that renders her reading of (0) true, while also ensuring that when the resultant sentence is translated back into modal discourse, it more or less says what (0) says (or will be read as (0) is read). As we shall now see, it is very difficult to see how, or if, this can be done.

A first thought is that we read (0) as

- (7)

There is at least one actual swan and, according to PW, there is a w in which its counterpart is blue.

There are two problems with this proposal. First, (7) does not preserve the content of (0). It is not an exact—or even a particularly good—translation back into modal discourse, for it yields

- (8)

At least one of the actual swans might have been blue.

But (8) says something very different from what (0) does, which suggests that one would not want to read (0) as (7).

This might not be a terribly worrisome objection, but there is a more serious reason for resisting this proposal. The problem is that, unlike (7), the truth or falsity of a modal claim like (0) should not require that there actually be any swans. But the truth of (7) requires that there actually be any swans. Hence, (7) is not an adequate reading of (0).

To see the problem, consider

- (9)

There might have been ferocious unicorns,

which, for Lewis (though not Kripke 1980), would come out true. But if the present proposal is accepted then (9) does not come out as true, for it would be read as something like

- (10)

There is at least one actual unicorn and, according to PW, there is a world, w, in which its counterpart is ferocious.

Since a Lewisian modal realist will take (9) to be true but (10) does not come out as true, an MFRist will not want to read modal sentences on the model of (7) or (10). How, then, should such sentences be understood, if the MFRist is to avoid the Aboutness Problem? (More directly, what should the relevant re be?)

An MFRist might steal a page from Lewis (1986) and take a re to be a Lewisian Property. For Lewis (1983, 1986), an X property (viz., that of being an X) is the set (or class) of all actual and possible Xs. Hence, for a reading of (0), an MFRist might propose something like

- (11)

The set of actual and possible swans is such that, according to PW, there is a world, w, in which members of that set are blue.

This is a coherent rendering of (0), to be sure, but, as should also be clear, it is not something that an MFRist can endorse, since to accept (11) is to be committed to possibilia, which no MFRist would accept. Hence, MFRists will not propose that (0) be read as (11).

Perhaps an MFRist can preserve at least some of Lewis’s ontology without taking onboard an unwanted commitment to possibilia, e.g., by taking the re to be properties, understood in Lewis’s sense, without granting the existence of merely possible objects. One might, in other words, take the swan property to be the set of all actual swans. Since, according to PW, everything is world bound, an MFRist will have to be careful about how the replacement proposal for (0) is going to go. One option might be something like

- (12)

The swan property is such that, according to PW, there is a world, w, in which counterparts of its members are blue,

where ‘the swan property’ denotes the set of actual swans.

This reading of (0) would avoid the problem of possibilia. But the second problem with the first proposal reemerges, since the truth of the sentence still depends on the existence of actual swans, which would thereby render an analogous reading of (9) untrue (i.e., either false or without a truth value). What this strongly suggests is that if MFRists propose to resolve the Aboutness Problem, by providing a de re reading of the replacement sentence for (0) (and for modal claims more generally), they would be advised to look elsewhere for an account of properties.

Sticking with Lewisian properties bears no fruit. Hence, we might consider an alternative view of properties—properties as universals, where particulars instantiate universals. Thus, the MFRist might propose that (0) be read as something like

- (13)

Swanness is such that, according to PW, there is a world, w, in which what instantiates it is blue.Footnote 27

As we will see, below, there is an immediate problem with (13). But, for now, let’s leave that aside and just try to get clear on this proposed reading of (0).

As is familiar, there are two views of universals, Platonic (ante-rem) universals and Aristotelian (in re) universals. The difference between the two views (or conceptions) turns on whether a universal has a spatio-temporal location.Footnote 28 Broadly put, Platonic views of universals deny that universals have spatio-temporal locations and treat them as abstract, sui generis entities. The Platonic conception of universals also allows for uninstantiated universals.

By contrast to the Platonic view of universals, the Aristotelian view does not allow for uninstantiated universals. Armstrong (1978), who argues for the latter conception, takes universals to be repeatable entities that are wholly present whenever particulars instantiate them. On this view, a universal is a constituent part of each particular that has it.Footnote 29 And what is central to this view of universals is a principle of instantiation according to which a universal depends for its existence upon having an instance. Hence, under the Aristotelian conception, there are no—indeed, there cannot be any—uninstantiated universals.

The difference between these two conceptions, whether allowing, or disallowing, uninstantiated universals, is critical for an MFRist’s proposed reading of modal sentences, if it is going to avoid the Aboutness Problem. An MFRist’s proposed reading of (9) must have the same truth-value as the sentence would have if interpreted by Lewisian Modal Realism. Since (9) is true according to Lewis, the proposed reading of that sentence by MFRists must be true, as well. But if an MFRist adopts an Aristotelian conception of properties, her proposed reading of (9) ends up as untrue. This is thus a reason for not proposing that (9) be read in this way. It follows that in order to avoid the Aboutness Problem, by providing a de re reading of modal claims, MFRists will have to endorse a Platonic view of universals, one that allows for uninstantiated universals.

Although adopting such a view of properties might solve the Aboutness Problem, because it is a substantial cost, it will hardly give advocates of MFR solace. In addition to the fact that few philosophers endorse an ontology of ante rem universals, there are also a number of familiar problems with that view (Cf. Armstrong (1978), Benacerraf (1965), and Field (1989), for a few of the problems). Perhaps the most pressing problem is what’s known as the access problem. The access problem is usually presented for a Platonic view of numbers according to which numbers are abstract objects.Footnote 30 But we can present a variant of the access problem in the key of properties, instead of numbers.

To see the access problem for properties as ante rem universals, notice that, while it seems that we have knowledge of, or about, some properties, it does not seem that we can have knowledge of, or about, any abstract objects. But if properties are abstract objects, as the ante rem view of universals holds, then it follows that we do not have knowledge of, or about, any properties. Thus, the ante rem view of universals appears to conflict with our epistemics for properties.

Now, whatever we want to say, ultimately, about the access problem for properties as ante rem universals, notice that if MFRists accept the present solution to the Aboutness Problem, they take on the access problem as a new problem.Footnote 31 Thus, if advocates of DS adopt MFR and propose to resolve the Aboutness Problem in the way that Rosen proposed (again, in personal communication) then, in addition to becoming ontologically committed to ante rem universals, they also take on board a host of new problems. And, ironically, these problems with abstract objects have been some of the primary motivations for adopting other fictionalist accounts.Footnote 32

In short, MFRists are faced with a dilemma. Either they do not propose a de re reading of modal sentences, generally, in which case they are stuck with the Aboutness Problem, or they do propose such a reading, as a means for resolving the Aboutness Problem, in which case, as we have seen, they will be committed to anti rem universals. The former is intolerable and the latter, in addition to carrying a large cost, metaphysically speaking, saddles the MFRist with a host of seemingly unsolvable problems. For these reasons, and on balance, advocates of DS ought not to be MFRists.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, after clarifying certain features of MFR, I have raised two problems for it and have argued that these problems strongly suggest that advocates of DS ought not to endorse or adopt that position, MFR. MFR dictates how the discourse should be understood by, or for, advocates of DS. I have provided arguments for why, for advocates of DS, the discourse should not be understood in the way. Accordingly, if these arguments compel—and I hope to have shown that they do—then they constitute reasons for rejecting MFR, Rosen’s brand of Modal Fictionalism.

Notes

By modal discourse I mean sentences that contain the central modal idioms—expressions like ‘possibly’, ‘necessarily’, and ‘could have’, ‘might’, ‘must’, etc.

This is not to say that an advocate of DS ought not to endorse any version of modal fictionalism, for there may be other versions of modal fictionalism [indeed, there is at least one, as presented in Yablo (1996)] to which the particular arguments developed here do not apply.

Rosen appears to assume that (0) is meaning equivalent to (1), but whether this actually is his view, or whether he or anyone who favors the possible-worlds analysis of modal discourse endorses some weaker thesis, to the effect that (1) provides a reductive analysis of (0), or that (1) specifies the truth-conditions for (0), or is just logically equivalent to (0), is not crucial to my critique of modal fictionalism as a DS regarding modal discourse.

Of course, there are ways of reading something like (3*) so that it becomes about phlogiston (or combustion), but that is different from claiming that (3*) is about such “things”. One standard way of ensuring that a sentence like (3*) is about what Becher’s theory is about is by providing a de re reading. Please note that in Sect. 4.2, I consider some de re readings of story (or, more accurately, theory) prefix-involving modal sentences.

An operator, O, is non-factive just in case the form of inference, from ‘O(p)’ to ‘p’, is invalid.

This should not be taken to imply that I accept a syntactic understanding of theories, as opposed to a semantic one of the sort that is proposed in van Fraassen (1980). I take no official stand on this issue. Thanks to James Woodbridge, for pointing this out.

Many thanks to an anonymous referee, for pressing me to say more in support of the claim that (3) is not about a brilliant detective (or 221b Baker Street). Thanks, as well, to Jody Azzouni, for helpful discussion on this point.

Like Lewis’s (1978) fictionalist account of overt fiction, what is central to all fictionalist accounts is what I have called semantic redirection, so that, rather than being about a brilliant detective, a sentence like (2) ends up being about something else—in this case, about the Holmes stories. For more on this, see Armour-Garb and Woodbridge (forthcoming).

For the sake of completeness, I note Rosen’s (1990, p. 333) proposed postulates:

-

(1)

Reality consists in a plurality of universes or “worlds”.

-

(2)

One of these universes is what we ordinarily call the universe: the largest connected spatiotemporal system of which we are parts.

-

(3)

The others are things of roughly the same kind: systems of objects, many of them concrete, connected by a network of external relations like the spatiotemporal distances that connect objects in the universe.

-

(4)

Each universe is isolated from the others; that is, particulars in distinct universes are not spatiotemporally related (thus, no particular inhabits two universes).

-

(5)

The totality of universes is closed under a principle of recombination. Roughly: for any collection of objects from any number of universes, there is a single universe containing any number of duplicates of each, provided there is a spacetime large enough to hold them.

-

(6)

There are no arbitrary limits on the plenitude of the universe. (7) Our universe is not special. That is, there is nothing remarkable about it from the point of view of the system of universes.

-

(1)

According to Rosen (1990, p. 335, fn. 16), a sentence, S, is a non-modal intrinsic truth about our universe if it contains no modal vocabulary and entails neither the existence, nor the non-existence, of anything outside of that universe. Moreover, all quantifiers and names in such sentences are restricted to the inhabitants of this universe.

In previous work (forthcoming), I have distinguished philosophical fictionalism from the philosophy of fiction. The former involves the application of fiction in order to resolve certain philosophical problems, which arise for some putatively problematic discourse [e.g., Yablo’s (2005) proposal for how we might resolve certain (ontological) problems, which arise given how mathematical-talk is standardly construed, viz., as involving a commitment to numbers as objects]. By contrast, the latter aims to answer certain questions about features, or elements, of overt fiction (e.g., regarding the ontological status of fictional characters). The distinction, between philosophical fictionalism and the philosophy of fiction, is meant to parallel that between philosophical logic and the philosophy of logic, as those distinct activities are standardly understood. For a nice discussion of the difference between philosophical logic and the philosophy of logic, see Goble (2001).

According to Woodward (2008, p. 277), “the core of modal fictionalism is a claim regarding which propositions are expressed by modal sentences ….” As he (Ibid.) notes, a modal sentence like (0) will express a true proposition regarding the content of the hypothesis of the plurality of possible worlds. Note that Liggins (2008) claims that, rather than holding that (0) means what (1) means, as modal realists contend, the modal fictionalists will claim that (0) means what (4) means.

Although I have provided some reasons for thinking that the ways in which Liggins and Woodward describe MFR, they seem to be committed to hermeneutic readings of that view, I should make clear that neither theorist explicitly espouses such a hermeneutic view and, in fact, in personal communications, both have made clear that they did not intend the versions of MFR that they aimed to defend to be read in a hermeneutic light. This is a good thing—at least for them—because it seems clear that there is no prospect for a hermeneutic version of MFR, understood as the view that a modal sentence like (e.g.) (0) actually is an elliptical rendering of (4).

For one thing, since people were assertorically uttering modal sentences long before Lewis’s modal realism was introduced, it seems that a hermeneutic version of MFR would have to maintain that the meanings of modal sentences changed with the introduction of Lewis’s modal realism. This seems wildly implausible, as an empirical claim about the content of modal claims. But if it is not granted by one who endorses a hermeneutic reading of MFR (if such there be), then it would be an utter mystery how a sentence like (0) would be an elliptical rendering of (4).

For another thing, it sure seems that ordinary people who are not familiar with Lewisian modal realism at least sometimes understand sentences of modal discourse. But if (e.g.) (0) is actually an elliptical rendering of (4), then they do not really understand such discourse. Now, perhaps one who endorses a hermeneutic reading of MFR would contend that, in fact, people do not understand modal discourse, since they are not familiar with Lewisian modal realism, in spite of the fact that they go about assertorically uttering such sentences. But that is a desperate (and, I would say, indefensible) move. These are just some of the problems that a modal fictionalist would face, were she to insist on a hermeneutic reading of MFR. Thanks to an anonymous referee, for suggesting that I elaborate these points.

There is nothing special about (6). The points that I make here are intended to generalize.

Of course, one might accept (6) on the basis of testimony. But that is irrelevant, for present purposes, since the details whereby recombination would yield a flying pig are heretofore unknown.

There is an interesting question about why we accept (5), viz., about what grounds our modal beliefs. Is it based on conceivability or does it arise from something else? For an interesting discussion of these issues, see Evnine (2008).

Thanks to Wayne Davis and Richard Woodward, for helpful discussion on these points.

Sider (2002) makes a related point but, importantly, he puts it to very different use.

I am assuming that, in general, when we assertorically utter a sentence, there is some thing about which we want to say something and that (again: in general) our desire is achieved when what we have assertorically uttered is (at least partially) about that thing. Of course, there need not be just one thing about which we wish to say and, analogously, there need not be just one thing that our sentence is about.

More specifically, when the intensional operator in (3) has widest scope, the sentence is about, and is only about, the Holmes stories.

In fact, since ordinary speakers do not generally even know about a proposed (or supposed) ontology of possible worlds, it is highly likely that that is not something they aim to convey, when they assertorically utter modal sentences. This is not to say that when they assertorically utter modal claims they are not committed to possible worlds. The point is just that the aim of their assertoric utterances need not be to say something about possible worlds.

Of course, there are ways of reading (3) such that it ends up being about brilliant detectives, etc. I consider some of these ways, with a direct application to (0) (and kin), in the next section. The important point, for our purposes, is that, on a face-value reading of (0) as (4), it is only about PW, just as, on a face-value reading of (2) as (3), it is only about the Holmes stories.

Thanks to Gideon Rosen, for suggesting this sort of response to the Aboutness Problem.

One might worry that where the re is a universal, a reading of (0) as (13) will run into problems, given Lewis’s principle that nothing is wholly present as part of 2 different worlds. (Cf. Lewis (1968, p. 114).) Although this worry is legitimate, it bears noting that Lewis’s theory is intended to apply to particulars. As Lewis notes (1983, p. 345, fn. 5), if he were to countenance universals, since they must be capable of repeated occurrence in multiple worlds, he would have to take them to be an exception to the afore noted principle.

Having a spatiotemporal location is different from being a spatiotemporal part of (say) a particular. While those who endorse the Aristotelian conception of universals (e.g., Armstrong) contend that universals are wholly present whenever particulars instantiate them, they do not claim that they are a spatiotemporal part of particulars that have them.

Cf. Lewis (1983, p. 344).

Of course, the access problem only gets going if we deny that we have knowledge of, or about, abstract objects. If we are prepared to grant that we have such knowledge, the access problem dissipates. Thanks to Wayne Davis for pointing that out.

Since Lewis does not accept ante rem universals, there are also questions about whether PW will generate the right sorts of worlds in order for (e.g.) (14) to be true. But since the problem with such universals remains, even if these questions can be answered, we need not take them up here.

References

Armour-Garb, B., & Woodbridge, J. (2012). The story about propositions. Noûs, 46(4), 635–674.

Armour-Garb, B., & Woodbridge, J. (forthcoming). Pretense and pathology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Armstrong, D. M. (1978). Universals and scientific realism, vols. I and II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Balaguer, M. (1998). Platonism and anti-platonism in mathematics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Benacerraf, P. (1965). What numbers could not be. Philosophical Review 74, 47–73.

Evnine, S. (2008). Modal epistemology: Our knowledge of necessity and possibility. Philosophy Compass, 3(4), 664–684.

Field, H. (1980). Science without numbers: A defence of nominalism. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Field, H. (1989). Realism, mathematics & modality. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Forrest, P. (1986). Ways worlds could be. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 64(1), 15–24.

Goble, L. (2001). The Blackwell guide to philosophical logic. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kripke, S. (1980). Naming and Necessity Cambridge. MA: Harvard University Press.

Lewis, D. (1968). Counterpart theory and quantified modal logic. The Journal of Philosophy, 65(5), 113–126.

Lewis, D. (1978). Truth in fiction. American Philosophical Quarterly, 15(1), 37–46.

Lewis, D. (1983). Philosophical papers (Vol. I). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1986). On the plurality of worlds. Oxford: Blackwell.

Liggins, D. (2008). Modal fictionalism and possible-worlds discourse. Philosophical Studies, 138(2), 151–160.

Rosen, G. (1990). Modal fictionalism. Mind, 99(395), 327–354.

Rosen, G. (1995). Modal fictionalism fixed. Analysis, 55(2), 67–73.

Sider, T. (2002). The ersatz pluriverse. Journal of Philosophy, 99, 279–315.

Stalnaker, R. (1976). Possible worlds. Noûs, 10(1), 65–75.

van Fraassen, B. (1980). The scientific image. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woodward, R. (2008). Why modal fictionalism is not self defeating. Philosophical Studies, 139(2), 273–288.

Woodward, R. (2010). Fictionalism and inferential safety. Analysis, 70(3), 409–417.

Yablo, S. (1996). How in the world? Philosophical Topics, 24(1), 255–286.

Yablo, S. (2005). The myth of the seven. In M. E. Kalderon (Ed.), Fictionalism in metaphysics (pp. 88–115). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Jody Azzouni, Robert Howell, David Liggins, Gideon Rosen, Richard Woodward and an anonymous referee for the Journal, for helpful comments and/or suggestions. Especial thanks are due to Wayne Davis and James Woodbridge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Armour-Garb, B. New problems for modal fictionalism. Philos Stud 172, 1201–1219 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-014-0344-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-014-0344-6