Abstract

Each person is perceived by others and by herself as an individual in a very strong sense, namely as a unique individual. Moreover, this supposed uniqueness is commonly thought of as linked with another character that we tend to attribute to persons (as opposed to stones or chairs and even non-human animals): a kind of depth, hidden to sensory perception, yet in some measure accessible to other means of knowledge. I propose a theory of strong or essential individuality. This theory is introduced by way of a critical discussion of Van Inwagen’s and Baker’s ontologies of persons. Composition Theory and Constitution Theory are shown to be complementary, in their opposite strong and weak points. I argue that both theories have unsatisfactory consequences concerning personal identity, a problem which the proposed theory seems to solve more faithfully both to folk intuitions and the phenomenology of personal life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

“Love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds...” W. Shakespeare, Sonnet 116Footnote 1

Mind, brain and persons

According to the hypothesis underlying this research, many questions discussed in the philosophy of mind would require a revision of the current (more or less tacitly presupposed) ontology. Such questions concern the subject of properties or states commonly attributed to mind by philosophers. According to our pre-philosophical intuitions, “The thinker – the thing that thinks, that has an inner life – is neither an immaterial mind nor a material brain: it is the person” (Baker, 2000, 6).

This remark made by Lynne Baker can be argued for on the basis of actual phenomenological evidence. A person is required to prove theorems, play tennis, create artefacts, study philosophy, or to respond to somebody’s hate or love. The right subjects of attributed thoughts and desires, choices and attitudes, behaviours and actions, are undoubtedly persons. We attribute such things to somebody. Languages provide us with personal pronouns in these cases. In a way, this hypothesis suggests that we should take the references of (interrogative, relative, undetermined) personal pronouns very seriously. It is a sketch for ontology of personal pronouns. It suggests that current ontology has no adequate place for their references. That a reform of the ontology (and of the epistemology) of the individual is needed to give an adequate interpretation to the thesis that persons do exist.

Ignoring the ontology of persons – or of “individuals” in a stronger sense than the one customarily acknowledged in philosophical terminology – has momentous consequences. A highly questionable picture of our being has ensued. According to our hypothesis, whenever we come across a being within a being, a man within a man, a soul within a body, a mind bearing a very puzzling relation to a brain, an interiority which is not properly the inside of any thing; whenever we try to escape dualism by even more unsatisfactory solutions; whenever we are in trouble with the very question of our identity as persons; whenever we look for our place in a “nature” which does not seem to allow for any “spirits;” whenever we try to think about our “inner life” and are left with a ghost; whenever we translate the content of moral and religious experience into bad, though still current, dualistic metaphysical language, there we just fail to provide an adequate conception of our being. And the reason why we fail is that we have not worked out the nature of individuality.

In this paper we shall only deal with that part of the hypothesis according to which an inadequate ontology is responsible for most unsatisfactory solutions to the personal identity problem.

In a sense, we move in a direction which is quite the opposite of the one taken by defenders of the Extended and Distributed Mind Theory. Due perhaps to some common phenomenological background, we share with some of them the first move, consisting in “embodying mind.” That is, in recognising the fact that a cognitive system such as that of the animal species does not seem to be so indifferent to the stuff realizing it as were most classical computational models. But this is after all an empirical matter, a matter where a philosopher has nothing to say and everything to learn. On the other hand, and more specifically, we agree with the theorists of the embodied mind concerning the role which the sensible and ‘lived’ body plays in organizing our mental life – and particularly our cognition of the environment and other people. We are ready to “embody” and “situate” mind, but persuaded that doing so is not yet identifying the right subject of such predicates as the ones we attribute to somebody.

Our hypothesis, then, does not share the further move which is often made in this spirit, namely that of “distributing” mind onto external supports of cognitive work, such as language, pen and paper, print, computers and so on. Far from opposing preceding models of mind, the distributed mind model accentuates, if anything, their tendency to conjecture a totally impersonal reality “behind” our appearance of persons. These new theories substitute the mind – software analogy of the classical computational models and the reduction of mind to brain activity of the neurobiological models with the idea of an external scaffolding of mind (language, writing, culture). But in so doing, they end up welding together the most popular philosophy of nature (materialism) and the most popular philosophy of culture (hermeneutic post-modernism). According to which a chair is but a chance to sit down, and a person is but a knot of relations, or the holder of a role, in any case a function of a community. This new, pragmatically oriented, model of cognitive science, then, takes one more step in the direction of a deconstruction of the apparent person, that is, of the rational and moral agent, endowed with an individual physiognomy, free agency, and of a personal perspective on reality and on values.

Our hypothesis goes in the opposite direction.

Essential individuality

What is individuality? The intuition I shall defend is that some objects are individuals in a stronger sense than others, which are usually classified as individuals too by the standard logical and ontological terminology. For example: a person is an individual in a stronger sense than a chair or a stone; a work of art, a poem or a novel, a picture or a sonata, have a stronger individuality than, say, washing machines or refrigerators. This stronger individuality will be called essential individuality.

Persons are not, according to this theory, the only case of individuals in an essential sense; yet they are the paradigmatic case of such individuality. Now this connection to persons is what makes the study of essential individuality deeply interesting – and necessary. Even more so, since the strong sense of « individual » is practically the only one people bear in mind when using common language, and to some extent, common sense.

Each person is perceived by others and by herself as an individual in a very strong sense, namely as a unique individual. Moreover, this supposed uniqueness is commonly thought of as linked with another character that we tend to attribute to persons (as opposed, say, to stones or chairs): a kind of depth, hidden to sensory perception, yet in some measure accessible to other means of personal knowledge. Uniqueness and Depth are the main features of the notion of Strong or Essential Individuality, which is the subject of this paper. It is a notion – admittedly a quite implicit one – we make use of in a massive way when dealing with people (marrying a person, for instance, or falling in love with her/him, or being in mourning for somebody), but also when thinking of people (writing a biography, studying a historical character) or addressing to them (writing a letter, entertaining a conversation).

I shall start with a short discussion of two works which I regard as deeply innovatory in the fields of ontology and the theory of persons, namely Material Beings by Peter Van Inwagen and Persons and Bodies by Lynne Rudder Baker.Footnote 2 I shall concentrate on just one point for each book, one which seems to me to represent the main intuition of its author. Let us term them, respectively, Unity and Subjectivity. Putting one against the other, so to speak, we shall better see what each of these notions can contribute to an ontology of (human) persons, and what is the fault of each one from the other’s viewpoint. Finally, I shall work out that very idea which seems to spring out of the friction of these two notions, namely that of Essential Individuality.

Peter Van Inwagen and Lynne Rudder Baker confronted

Let me first say why I think that these two works, in spite of the divergent philosophical theses they support, have brought contemporary debates on naturalisation of mind and/or person on a new and far more advanced level with respect to what we might call “the classical phase” of those debates.

I would roughly identify this “classical phase” with

-

A dominance of the classic computational cognitive model of mind;

-

A dominance of an ontological framework almost exclusively shaped by the body–mind problem, with its almost inescapable alternative between a physicalism and a dualism (with a whole series of in-between positions).

Against this background, our two mentioned works are deeply innovatory in that they do not presuppose a given ontology (quite typically a physicalistic one) as a starting point for question of reducibility or non-reducibility of “mind” (to this given ontology). They rather try to innovate ontology to give account of human and personal reality. More specifically, such a common feature may be articulated in at least four points:

-

1.

Concerning human persons, they share a (local) materialism, compatible with molecular biology and evolutionary theory (but not necessarily reducible to physicalism);

-

2.

They oppose both dualism and reductive or non reductive monism, and that on behalf of some idea of integrity or unity of human persons and /or animals, which is presented as a feature that any ontology of the living being should give account of. Such a feature is quite differently interpreted by our authors, respectively in terms of composition and of constitution.

-

3.

Both oppose traditional (extensional) mereology with its reductive consequences (for example incapacity to give account of emergent properties, as opposed to resultant ones)

-

4.

Both make an essential use of some sort of a “Cartesian” argument and/or a “Cartesian” notion (in what they say, respectively, on the unity of thinking and of the first person perspective).

Now let’s go over to what is more specific of each one of these authors. I shall present each one’s characteristic notion on the background of the celebrated Boethian definition of a person: Naturae rationabilis individua substantia. That is, a person is the individual substance of a reasonable nature. In order to understand this formula, and the usage we are going to do of it as a framework for van Inwagen’s and Baker’s views, one should think that «a reasonable nature» refers to a property which (in Boethius’view) can be instantiated by human as well as by non human persons, such as angels or God. Hence we must think of it as a condition which should be described in neutral terms relatively to the instantiating substance (bodily or not). What is really important is the restriction upon substances conveyed by the qualification, “individual.”

We may take this definition, or its parts, as a set of adequacy conditions for a theory of persons, namely of conditions any adequate theory should satisfy (I shall not argue for this point here, but of course, the point of taking Boethius’definition as a standard is that nobody seems to have objections to it: neither traditional dualists, nor traditional materialists. In fact, this formula seems to be, if anything, too obvious to be worth criticism. A view that I don’t share, by the way).

In this perspective, Van Inwagen theory of material beings would give a condition of substantiality, whereas Baker’s theory of persons would give a condition for reasonable nature. Let’s call these conditions, respectively, Unity and Subjectivity. Let’s briefly comment upon both of them.

A quotation from Leibniz, recalling Leibniz theory of material beings or composed entities, will best introduce those who haven’t read Van Inwagen’s book to its main intuition, and recall it to the minds of those who know it. It draws on a relevant part of Leibniz’ ontology, which actually is a “henology”, a theory of unity: “Ce qui n’est pas véritablement un être n’est pas non plus véritablement un être.”Footnote 3 No entity without unity: this might be the Leibnizian-Van Inwagean tenet for an ontology of composed entities (such as the beings we are). Van Inwagen actually rejects a whole series of tentative solutions of what he terms the Special Composition Question, which is about “the conditions a plurality (or array, group, collection, or multiplicity) of objects must satisfy if they are to compose or add up to something” (Van Inwagen, 1995, 22).

The spirit of this rejection, which is formally too refined to be reproduced here, might be compared to Leibniz’ point in denying substantial unity to most sorts of arrays or aggregates of simples (mereological simples: we need not think of Leibniz monads, we may be happy with whatever could be assessed to be the ultimate constituents of matter). An army, a storm, a heap of stones, but also a single stone, or an artefact, shortly whatever has no inner principle of unity of its ultimate constituents is just arena sine calce, sand without lime. And as soon as we look for the positive nature of a principle of unity, we come across an idea which does not seem very far from Van Inwagen’s solution to the Special Composition Question. Here is Leibniz’ proposal: “The organisation or composition without a subsisting principle of life ...would not be sufficient to grant that the same individual stays idem numero” (Leibniz, 1990, 71: L’organisation ou configuration sans la subsistance d’un principe de vie...ne serait pas suffisante à faire permaner idem numero le même individu).

And here is Van Inwagen solution (we reproduce without further explanation Van Inwagen’s easily understandable conventions on plural variables):

(LIFE). Ey (the xs compose y) iff (the activity of the xs constitutes a life) (1990, 90).

A thesis which actually implies a second characteristic thesis of Van Inwagen’s, called the Denial:

(DENIAL) There are no other material beings than the mereological simples and the living beings.

Life is described as a self-maintaining event, and explained in a “narrow biological sense”, actually making an essential use of the notion of homeostatic activity (that incessant activity by which a living being reconstitutes itself) and its modern explanation in terms of an incessant actualization by every cell of the instructions contained in the individual’s genome.

As we may see even from such a reduced summary of this wonderful book, Unity is the central category of this ontology of material (or composed) beings. Yet one might suspect that the gap between life and consciousness is still unabridged in such an ontology: for nothing of what Van Inwagen says about humans in this book seems to imply that consciousness should be regarded as a necessary condition for a living being to be a human person. In fact, here as much as elsewhere, Van Inwagen seems to embrace Animalism (i.e. the thesis that a human person is identical to an animal of the species Homo Sapiens). But is Animalism an adequate description of our nature?

Some of these worries will be appeased when learning that consciousness has an essential role in the ontology of the human person; not an ontological role though, but an epistemological, so to speak. More exactly, a role in the argument for the existence of at least one being, or the proof that the condition for something composed to exist is actually satisfied. Such an argument is very Cartesian in style: something exists, because I, for one thing, do exist. How do I know? Well, because I think, of course. Therefore I exist. How do I know that I am no so illusory a being as a chair or a star? Because thinking, as opposed to the job done by what we call chairs, or even to that done by what we call stars, is not (cannot be) a cooperative activity in disguise. Chairs and stars do not meet the condition for unity, hence they are no real beings. Consequently, the functions or activities they seem to perform are well explicable in terms of “cooperative activities” of their parts. But the same, argues Van Inwagen, is not true of thinking. One needs to be one in order to think. (“Thinking,” in this context, seems to be used in as tolerant a way as “cogitare” in Descartes Meditations, so that this capability seems to extend itself to anything capable of consciousness, even in a very large sense).

Here one can see a stronger unity than the biological one common to animals and trees, or, for that matter, organisms generally. One can see the unity of a “being” which should be thought of as an act more than as a thing: in Aquinas’ language, esse ut actus...

Capability of thinking qualifies human persons, but not essentially. Actually, according to Van Inwagen, it is not a necessary property of them. A person in a deep coma is still a person. By the same argument, a person is not essentially different from a non human animal. Hence, a part of our possible worries about the specific nature of persons stays unappeased.

Let’s switch to the important point from Lynne Baker’s Persons and Bodies. Current literature deals more frequently with Baker’s constitution theory, according to which, as a particular case, a human person is constituted by a human body (or an animal of the species Homo Sapiens) without being reducible to or identical with a human body. Persons have ontological significance as such, they are new sorts of things, with new kinds of causal powers, no more reducible to their biological reality than a statue is reducible to the piece of marble which constitutes it. As we can see, this theory contradicts one major point in Van Inwagen ontology of the human person, namely, Animalism. As its rival, this theory is passionately against dualism, even of a disguised, functionalistic kind. Or, for that matter, against spiritualism (both theories are at least “locally,” i.e. concerning humans, “materialist”). Constitution is a fundamental relation, analogous to Van Inwagen composition at least in its capability to conceptualize some sort of integrity or unity we feel as characterising human persons (for Van Inwagen, living beings too, and nothing else; for Baker[2000, 20], artefacts too, and a lot of other things. It is “a pervasive relation, found wherever one turns”). But constitution, though being “a unity relation, and not mere spatial coincidence” (46), falls short of identity.

Important as it surely is as a conceptual means to describe the nature of human persons, the notion of constitution is definitely not the one which captures the specific nature of persons as such. The one which is designed to do so is the notion of Subjectivity, i.e. capability of regarding oneself as a subject. Or, in Baker’s terms, First-Person Perspective in a strong sense. “A person has a capacity for a first-person perspective essentially; her constituting body has it contingently” (2000, 59). First-person perspective in a strong sense is an ability to think of oneself as oneself: “An ability not only to make a first-person reference, but also to attribute to oneself a first-person reference” (66).

Subjectivity, as Baker defines it, implies conceptual abilities and reflection. According to her theory, it is the very feature which is responsible for us being rational and moral agents, as well as bearers of normativity. And, as she quite nicely adds, as ontological contributors: beings capable to give birth to new kinds of things – such as artefacts, institutions, goods.

On the other hand, Baker’s view seems to exclude infants and human beings in a state of deep coma from the status of persons, unless “capability” is meant in a very wide sense. (This is one reason to suggest that Subjectivity should not be regarded as a necessary, but only as a sufficient condition for Personality, as we shall see).

We may now re-arrange our discussion of these two competing categories to think of our nature, Unity and Subjectivity, against the background of Boethius’ definition. Actually, Baker’s First Person Perspective (or Subjectivity) is so defined that it would satisfy Boethius’ condition on the property of having a reasonable nature, namely, being able to be instantiated by substances which would not be human animals: for example, bodies made of some non-organic stuff, gradually substituted for the old flesh-and-bones bodies). On the other hand, Van Inwagen’s Unity, as only provided by that kind of composition named Life, does not make use of or presuppose the concept of body: on the contrary, it only gives content to the very idea of (composed) substance.Both theories would be “adequate” by the Boethian standard, for according to both of them a person would be the individual substance (instantiation) of a reasonable nature. The difference being in the part of the definition which would express the essential feature of a human person: Subjectivity (First Person Perspective) for Baker, real Unity for Van Inwagen.

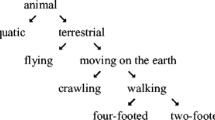

We may therefore insert each philosopher’s Essential Feature of Persons below the corresponding Boethian category. Baker’s contribution, accordingly, is on the left hand side of the table; Van Inwagen’s on the right hand side:

NATURAE RATIONABILIS | INDIVIDUA | SUBSTANTIA |

Subjectivity | Unity |

This schema should be understood as follows: Baker would (if required) accept the Boethian formula while spelling out the condition of a “reasonable nature” in terms of Subjectivity (the qualifying part of the definition); whereas Van Inwagen would (if required) accept the same formula while giving real Unity (of Life) as condition of substantiality.

Let’s now look at the two theories in the light of each other, so to speak. In this light, they both show the faults of their virtues: on Baker’s side, we may notice that the very strong (and very specific) reading of “reasonable nature” in terms of First Person Perspective – a very valuable contribution in my sight – does not go without problems as far as the unity of a human person is concerned (this is the main fault of Constitution Theory according to Baker’s critics). On Van Inwagen’s side, we have to stress that, while the unity of the human person is granted by his theory, the degree of subjectivity (or self-consciousness) required to make a human is really low-virtually equal to zero.

NATURAE RATIONABILIS | INDIVIDUA | SUBSTANTIA |

Weak Unity | ? | Strong Unity |

Strong Subjectivity | Weak Subjectivity |

Actually, from Van Inwagen’s point of view, you can hardly predicate Unity of the composed entity human person, if a human person is constituted by a human animal without being a human animal. But from Baker’s point of view, contingent Subjectivity (thinking as non-necessary property of human animals) is hardly a predicate of persons as such.

We seem to have come to an impasse. Which theory should we choose, and on which basis?

Maybe we may advance a little bit. From a phenomenological point of view, Subjectivity, defined as Baker defines it, is at most a sufficient, not a necessary condition for Personality. And Unity – characterised as Van Iwagen characterizes it – is a necessary, by no means a sufficient condition for it. But why?

Because, on one hand, whereas self-consciousness may or may not subsist, it is never comprehensive of all that a person is. A conscious self and a self are never coincident, no more than are a mountain and one of its side views, or the look of a person and the whole of her. Any well-founded phenomenon (and self-consciousness is a phenomenon, i.e. the appearance of a person to the person herself) is transcended by the reality it is founded on.

We call “Depth” personal being in so far as it is not conscious. Subjectivity cannot be there without Depth, but Depth can be there without Subjectivity. Yet Depth is not thought of as the grounding condition of Subjectivity in Baker’s theory. Subjectivity is left ungrounded, floating – so to speak. Insofar, Van Inwagen has a good point against Baker.

On the other hand, Unity is no sufficient condition of Personality: Uniqueness is needed. We cannot avoid recognising two discernible persons even in two monozygotic twins, or in any thinkable perfect clone of a human animal. A person is phenomenologically discernible from any other person. The very concept of first-personal perspective on the world (necessarily a different one for each embodied person) allows for this uniqueness. So far, Baker has a good point against Van Inwagen.

Uniqueness and Depth: here are the distinctive features of the very idea of Essential Individuality. Now, what about Individuality in the preceding schemes? Its case is left empty. Not surprisingly so. If meant in a weak or non-essential sense, this condition is obviously satisfied by both competing theories. Every human persons, either because she is one animal, or because she is constituted by one animal, is an individual in a weak sense.

Yet Individuality is not, according to Boethius’ definition, a condition obviously satisfied by any thinkable substance of a reasonable nature, otherwise it would not be necessary to mention it. Boethius mentions it, rightly so in my opinion.

We may see why by following the rest of the argument, according to which both competing theories lead to a somehow unsatisfactory theory of personal identity. The reason is that both make use of a concept of (weak) individuality which is inadequate for the ontology of the human person. Here is how things look:

NATURAE RATIONABILIS | INDIVIDUA | SUBSTANTIA |

Weak Unity | ? | Strong Unity |

Strong Subjectivity | Weak Subjectivity | |

Without Depth | ? | Without Uniqueness |

——— > | Personal Identity Without Personality | <——— |

And here is the hope behind the argument: that a theory making use of a stronger concept of Individuality might rescue and integrate, without any contradiction, the best features of both theories.

Essential individuality as a missed condition for a theory of persons

From a phenomenological point of view strong individuality is more than an implicit commonsensical notion about persons: it is a basic phenomenon, a way in which our being manifests itself quite apparently, or an ontologically well founded appearance. Each person shows a physiognomy, a visage and a dynamic style of her own, a global way of being there which is usually perceived as « just announcing » a personality. Physiognomy is usually felt to be the visible part of a whole that is not yet perceived. Not that it could be completely, not at least in the same way in which any object in space offers itself to further perception, namely, depending on our successive changes of point of view on it. Personality, or the reality of a person, is not accessible by further sensory perception, though it partially is by other ways of acquaintance, such as conversation or, more generally, communication, patient observation, psychological insight and so on. In short, the phenomenology of strong individuality is as well assessed in our everyday lives, as its notion is in our everyday thought.

But if this is the case, and if the notion of individuality is – in ordinary speech – commonly although implicitly linked to that of personality, it is surprising that contemporary philosophers have not philosophically or conceptually analysed such a strong notion in its peculiar strength, which implies much more than the weak notion of individuality that is current in philosophy, as we shall see. Such a silence is even more surprising within contemporary philosophy of mind, where it is the rule – with the relevant exception of some biologists or biologically minded philosophers.

Strangely enough, subjectivity seems to be the only notion taken into account by both “naturalizers” and their opponents, whereas strong individuality is no less essential to the ordinary notion of a person, as opposed to that of a “thing.” My hypothesis is that (Strong) Individuality is in a way the founding layer of personal reality, Subjectivity being one of its appearances. On this basis, all the features by which people differ from other things – but most strikingly from inanimate material objects, such as chairs and computers – lead back to this one: people are individual in an essential sense, chairs and computers are not.

And yet a category of (Strong) Individuality, and more generally an accurate analysis of the different ways of being a particular (as a shadow, as an event, as a chair, as a tree, as a dog, as a person), is not easy to find within contemporary debates on mind, persons, personal identity. I just pointed out some good reasons to put an end to this state of affairs.

The dominant model of individuality (DMI)

My next step is to argue that a very weak conception of Individuality has been the dominant one throughout our tradition, since Aristotle and up to now. By “a weak conception,” I mean one which does not give account of the current (implicit) notion of strong Individuality, or does not allow to discriminate between two sorts of individual things or “particulars.”

Let’s quote some passages from the most recent part of this tradition. Peter Strawson (1963, 2):

For instance, in mine, as in most familiar philosophical uses, historical occurrences, material objects, people and their shadows are all particulars; whereas qualities and properties, number and species are not.

One will grant that a concept of individuality on which basis one cannot distinguish the individuality of a person from that of a person’s shadow is a very general concept indeed.

In the same spirit of tolerance, Nelson Goodman (1977) denies that any of the ontological criteria of individuality proposed by the classics, medieval or modern, is in fact a necessary condition:

An individual may be divisible into any number of parts: for individuality does not depend on indivisibility. Nor does it depend on homogeneity, continuity, compactness, or regularity.

More recently, J.J. Gracia has revived the whole topics.Footnote 4 After close scrutiny of five traditional criteria of individuality (Indivisibility, Numerical Distinction, Capacity to divide the species, Identity over time, Non-predicability) Gracia comes to the conclusion that none of them can be a necessary and sufficient condition of individuality, except for a special reading of ‘Indivisibility,’ which makes the term synonymous of ‘Incommunicability’ in the sense in which Aquinas and Suarez use it, namely, non-instanciability (i.e. not being a Universal, a Species or a Type). This criterion allows for a notion as weak (and extensionally wide) as Strawson’s or Goodman’s. In fact, it confirms the plain empiricist equivalence between individuality and existence, which can be found at the very root of both Strawson’s and Goodman’s accounts of individuality.

An empiricist theory of individuality is in fact a version of a model which I shall refer to as the Dominant Model (DMI), and which is actually the most popular of two opposed models of individuality. It can be shown to be the one adopted not only by most contemporary philosophers in the analytic tradition, but even by most (or the most influential) thinkers in ancient and medieval times. An influential instance of this model is the theory of individuation by matter, attributed to Aristotle and more or less supported by his corpus; another is its cunning refinement by Thomas of Aquinas’ theory of materia signata. Footnote 5

Let’s try to describe the core-intuition on which all versions of the DMI are based. A thing’s individuality has nothing to do with the thing’s nature or essence, no matter whether one thinks that individual things do have a nature (like Aristotle or Aquinas), or that they do not (like Ochkam and most Empiricists): for in any case what is meant by “nature” (or essence) is thought of as something common (a “universal”), referred to (or even replaced by) a general or “sortal” concept. Individuality is a matter of contingency, closely bound to a thing’s existence; more exactly, to the circumstances of its existence, such as the time, the places, the portion of matter that are taken up by its existence. So for example, Socrates is a man, and he necessarily enjoys all properties characteristic of that nature, or implied by that concept. But this represents exactly what Socrates shares with others men, as opposed to the set of his accidental properties – in the Aristotelian general sense of belonging to other categories than substance–which distinguish him from other individuals of the human kind: and particularly the “matter” in which the human form is actualised, the places and the times of this actualisation, from birth to death. If we try to extract the very core of this intuition, we come across the old saying: individuum ineffabile. I.e., an individual is a tode-ti, a this one here, that is anything wich can only be pointed at or anyway referred to by an indexical expression, such as “the note sounding now.” This is an epistemological (or quoad nos) rather than an ontological criterion: yet it is founded in the intuition of existing as instantiating (from “instans”) whatever is signified by a verbal or conceptual description, which is thereby common to many things. According to this intuition, individuality is actually characterised as non-instanciability, or non “communicability,” also in the sense of ineffability. Individuals are beyond thought and language: not because of a transcendence of some sort, but just in that they are given to the senses.Footnote 6 They are only “knowable” by sensible knowledge, which is in fact no knowledge by classic or modern standards, but at most “evidence” for empirical knowledge. For from Aristotle to Strawson, Goodman, Wiggins or Gracia, there is no science of the individual. Let’s mention the missing link between medieval and contemporary analytic philosophers: Okham and the British Empiricist Tradition. Here are some famous passages from Locke, Berkley, Hume:

All things, that exist, being Particulars [...] (Locke, 1975, III, 27.3, p. 409).

But it is an universally received maxim, that every thing which exist, is particular (Berkeley, 1948, 2: 192).

’tis a principle generally receiv’d in philosophy, that every thing in nature is individual (Hume (1958), I.I.VII, p. 19).

Locke is even more explicit on what he means by “individuation.” Here is a quotation from Leibniz’ Nouveaux Essays. Philalète (Locke) is speaking:

What is called the principle of individuation in the Schools, where people struggle so much to know what it is, amounts to existence itself, which bounds each being to a particular time and a place incommunicable to two beings of the same sort (Ce qu’on nomme principe d’individuation dans les Ecoles, où l’on se tourmente si fort pour savoir ce que c’est, consiste dans l’existence même, qui fixe chaque être à un temps particulier et à un lieu incommunicable à deux êtres de la même espèce ; Leibniz (1990) II, XXVII, section 3)

Individuality is no longer a problem according to this tradition, because it is just a primitive notion, and one which is thought to be equivalent to that of existence. Existence, in its turn, is only known through sensory experience.

What is wrong with DMI?

To sum up: according to all versions of this Model, Individuality is but having distinctive circumstances of existence. My claim is that this is responsible for most unsatisfactory theories of personal identity. To see that let’s take a fresh start. Let’s forget about Locke. Personal identity is a serious question even outside philosophy. We often struggle to get more knowledge about the identity of a person. The normal question is then: “Who is he?” But the phrase is ambiguous.

First, imagine being a detective confronted by a series of photos of criminals. You are looking for the identity of Jack the Ripper. You ask yourself: “Who is he?” Here you mean:

-

1.

Which one of these persons is Jack the Ripper?

You are then looking indeed for those distinctive features of Jack the Ripper which a normal Identity Card would provide you with: visible physiognomy, date and place of birth, parents...

Now imagine yourself as Juliet thinking of Romeo, whom she has just met, and wondering in a dreaming mood: “who is he?” What you mean here is:

-

2.

What personality will Romeo reveal?

Your question is about the positive, intrinsic features of his nature, his character, his sensibility, his preferences, his values....

In both contexts you are wondering about the personal identity of somebody. Yet personal identity may be meant as either passport identity or as personality. That we think of the two as ontologically, even if not logically nor epistemologically linked, is clear: just imagine being the detective in a good thriller. In order to identify Jack in the first sense, you might have to go through a series of questions of the second kind.

Take sense 1 of a personal identity question: the features it asks for are exactly the features making up individuality according to DMI, namely, the information concerning distinctive circumstances of existence. But of course, these features make up personal identity just as passport identity, not as personality. They are sufficient to distinguish one person from another one extrinsically; they don’t give any information on his/her positive individual nature.

Now the DMI gives an account of individuality just in the sense required by sense 1 of the question on personal identity. Take Socrates: the DMI would grant that Socrates has distinctive circumstances of existence, but it would completely ignore “Socraticity,” what makes of Socrates the very person he is. And this is the reason why, since Locke, we have got used to thinking of “personality” as something separated from its apparent (bodily) circumstantial existence. Of course, what constitutes individuality according to DMI does not coincide with what constitutes personality. An individualizer, so to speak, is different from a personalizer. The circumstances of existence, for instance, keep changing (the famous puzzle of Theseus’ Ship is part of this problem), whereas personality stays very much the same, and so on.

Hence, we may adopt or not Locke’s theory of personal identity as psychological continuity, indifferent to its conditions of embodiment. But if we are not satisfied with it, we shall not go very far in case we keep a theory of individuality of the kind of DMI. There still is a gap between an Individualizer and a Personaliser: for Lynne Baker, for example, the first one is assured by the body which constitutes a human person, and the second one by “the same first personal perspective”(Baker, 2000, 132ff).

But it seems to me that one cannot avoid, by this solution, a very Lockean indifference to bodily physiognomy and related things. I would not recognise as the same person (e.g., Lynne) a person who would have, say, the same personal perspective of Lynne in the body of Peter (as a consequence of a perfect brain transplant). In this respect it seems to me that Van Inwagen has many good points in criticising both Locke’s and Baker’s theories of personal identity (see Van Inwagen, 1980, 2001, 144–161). As for the positive theory of personal identity of Van Inwagen, it seems to me that it very much reproduces the identity condition established by Locke for organisms generally: same life (1990, 143). But then, of course, Locke’s and others’ objections to the reduction of personality to its biological basis seem still to hold.

The common ground of these unsatisfactory theories seems to be their acceptance of the DMI.

The essential individuality model (EIM)

Strange as it may appear, a really coherent alternative model of individuality is not easily available throughout the history of philosophy. Yet there are at least three (and quite probably more than three) major exceptions, namely, Duns Scotus, Leibniz and, in more recent times, the “realist” phenomenologists of Munich and Goettingen, in particular Jean HeringFootnote 7. Our work owes much to the pioneering work of these thinkers of strong individuality, and to their passionate struggle to lay the foundations of what I shall baptise the Essential Individuality Model.

The core intuition that this model tries to capture is about the two phenomenological features characterising persons in our common perception of them: uniqueness and depth. According to ordinary thinking and acting, both features are somehow grounded on personality. How can we conceptualize these intuitions correctly? The critical idea underlying our model is that personality must not be thought of as a being separate or separable from whatever appearance it has – bodily appearance and its circumstances in the case of human persons. As, more generally, essence and its appearance cannot be separated according to phenomenology, in spite of the fact that essence does never manifest itself completely in real things. So far, ordinary perception and phenomenology converge – in the very notion of physiognomy. We should not divide what appears one in those individuals which appear provided with a hidden depth. “Socraticity” and the visible part of Socrates – his face, his nose, his way of walking about in town – seem to me to belong to one and the same reality. His visible and his invisible part (which keeps revealing itself in different aspects) appear as indivisible parts of a whole. Being faithful to this intuition means conceiving of a person’s depth as the way of being real, or appearance – transcendent, of those individuals which apparently have a depth. Interiority must be thought of as “furtherness;” soul or personality must not be thought as entities, nor even as separable (multi-realizable) functions, but as the sort of individuality characteristic of a special class of individuals. This is why an ontology of the individual, giving account of Strong or Essential Individuality, is the foundation of a theory of persons and personality.

As we saw, information about passport identity and about personality are apparently logically and epistemologically independent. I might have got to know something of your personality though ignoring all the personal data filling your identity card, or vice versa. Actually, much less of a knowledge of personality, or of those features of it which would constitute a self persistent over time, is needed to provide people with identity cards!

Yet splitting apart extrinsic (“passport”) identity and personality is one of the ways to produce dualism, and hence to misinterpret the phenomenon of Essential Individuality. It follows, as a first requirement to be fulfilled by our Essential Individuality Model, that registry identity and personality, that is Circumstantial Accidents and Essence, must be thought of as ontologically non-independent, even if logically and epistemologically independent.

But there is more to say. The DMI harbours a truth which we could not miss without serious consequences. This truth is the inescapable link between individuality and contingency. This link is not all the story, but surely part of it. Socrates’ personality is not really separable from Socrates’ life, the circumstances of his birth or of his death, the time and place of his life – although it is not reducible to all that. Individual nature cannot be denied in favour of pure contingency of existence, as the DMI would do, but contingency of existence cannot be dismissed from a correct concept of individuality either.

Here too, the conclusion is that extrinsic and intrinsic properties must somehow belong to one and the same individual essentially. Taking only the first ones as “individualizers” would amount to miss depth, i.e. the “soul” or “interiority” or “hidden reality” of a person; but taking just “intrinsic” properties as essential to the person would amount to miss his or her uniqueness in principle. For there is absolutely nothing which could prevent us from thinking “the same personality” (the same soul, the same interiority, the same hidden reality) as instantiated in different individuals, i.e. as existentially replicable, unless contingency and circumstances of existence are thought of as equally essential to the personality of a person, i. e. to his/her way to be an individual.

True enough, common sense and common language do not allow us to decide whether the uniqueness they acknowledge to persons should be conceived of as a contingent or as a necessary property of persons. Yet we claim that it should be thought of as necessary, and this is our theory’s progress, so to speak, on the mere phenomenological description of the apparent features of a person.

Here is the most “Leibnizian” part of our theory. In fact, I shall present the EIM by giving two criteria of Essential Individuality: an ontological and an epistemological one.

Two criteria for essential individuality

The first one is a gift from Leibniz.

-

(1)

Ontological Criterion of EI. Something has EI iff it satisfies Leibniz’ Principle of the indiscernibles, namely “It is not true that two substances may be exactly alike and differ only numerically.”

Or again: essential Individuality is there if and only if numerical identity necessarily implies uniqueness or being non-replicable.

A commentary. First, can we buy this principle without being committed to the whole of Leibniz’ metaphysics? Yes we can. For we do not take it as a definition of what really exists, of substance. We admit of “individuals” in a weaker sense, contrary to Leibniz’ opinion. Let’s call them “particulars.” In fact, there are plenty of things which do not satisfy Leibniz’ Principle. Electrons. Atoms of the same kind. Molecules of the same stuff. Machine-made bricks. Copies of the same book. Even if these last kinds of middle size dry goods should not be perfectly alike, it is conceivable that they are such, and this is enough.

Second question: what does the criterion impose on individuals in order that they be essentially such? As we can see, it imposes Uniqueness or Non-Replicability. Anything satisfying the criterion is such that, if it is one, it is unique. And necessarily so.

Third question: are there any “Leibnizian individuals?” We, persons, seem to be of that sort. For suppose a clone perfectly identical to me was suddenly created here and now. If this individual belongs to the same actual world I belong to, then she will occupy a different point of view, or a different first-personal perspective at t. But “having some point of view at t” is an intrinsic property of a person. Therefore my clone and I would differ intrinsically or essentially. Notice that this argument depends on the actual world being roughly as it is. If it were like a chessboard, then uniqueness would not be granted. I and my clone could occupy two symmetric cases of the chessboard, and our points of view would be indiscernible. This is a very striking example of a necessary property depending on a contingent one. A person has uniqueness necessarily, provided the world she is in has certain contingent features. Leibniz has a word for this kind of necessity: it is not logical or absolute necessity, but “hypothetical” or “conditional” necessity. Necessity of Uniqueness should not be conceived as absolute, but as conditional upon certain features of the actual world. And this is a very welcome restriction imposed by our model, for two reasons.

The first one is that it makes it compatible with emergentist naturalism. Given that the actual world is in some relevant features as it is – at its non personal level of reality – then personality, or essential individuality is possible; and whenever persons exist, they are necessarily unique. Admitting of a factual condition for a necessary property amounts to asserting that persons do not exist in all possible worlds, even though they are not necessarily restricted to the actual world. Maybe they did not exist in the past, maybe they could exist on different biological or even physical basis than ours own.

The second reason is that this restriction saves a precious feature of the DMI, namely the inescapable link between Individuality and Contingency. For if you cannot really think of Socrates without “Socraticity,” you cannot think of “Socraticity” without the look and postural attitudes of Socrates, without the age and world where he was born, without his parental or social history either...

As we know: information about passport identity and information about personality are not logically or epistemologically, but ontologically linked according to the EIM. Leibniz would have expressed this point in saying that each individual tota entitate individuatur, is individuated by all his properties, necessary and contingent alike (De Monticelli, 2004). And this gives us a nice picture of a person, namely that of a being capable of transforming contingency into individual essence – to internalize contingency, so to speak. The idea of such a being introduces contingency at the very root of essential individuality, thereby safeguarding the precious core – intuition of the DMI, and going beyond the limits of this model.

A model of essential individuality which would meet these requirements would present us with a theory of persons as producers of essence out of circumstances; and hence producers of novelty, because of the uniqueness of each internalized existence, and producers of destinies – for the same reason.

And this theory would allow us to answer the question: is the concept of a person reducible to that of the biological species Homo Sapiens, and if not, why?

Our answer is indeed that it is not. Why not? Because it is not as an exemplar of a biological species that an individual could be unique in principle, or necessarily unique. It seems to me that on the basis of a biological, hence of an empirical concept, one can at most affirm uniqueness as a factual property of the individuals belonging to a given species, hence as a contingent, not as a necessary or ontological property. Hence if we affirm that uniqueness is a necessary or ontological property of persons, then we must admit that persons cannot be reduced to their actual biological reality.

This answer qualifies our rejection of dualism, rejection common to reductive theories. Our theory aims indeed to give a rigorous content to the folk intuition of ourselves as a “something more” than the biological layer of our reality. “Something more,” though, in the sense of an actual supplement of reality relative to the biological layer. A supplement of reality – personality – which must not be divorced from the grounding layers of reality we certainly happen to share with other creatures (including inanimate things): or else we would fall in the dualistic or spiritualistic sin. On the other hand, this “something more” cannot be deflated to culture, or a set of representations, or of social habits and conventions, without ceasing to be a supplement of reality. This deflationary attitude, frequent in twentieth-century continental philosophy, would amount to reducing the notion of a person to a socially useful fiction, a kind of status designator corresponding to rights and duties one takes on when entering a human community.

Finally, we have

-

(2)

Epistemological Criterion of EI: x has EI iff x’s identity eludes sensory perception, as well as related (extrinsic) ways of identification (space-temporal location, indexicality, tagging, asking for identity card).

It is clear that this criterion just makes the phenomenon of personal depth explicit. It must be right, otherwise a detective or a customs officer would know of any given person exactly as much as his wife, or his future biographer. Encountering a new person would be no cognitive adventure. Knowing him or her would not take a lifetime – but just a few minutes, as learning to distinguish him or her from any other.

But this would open the chapter of a theory of personal knowledge. And this is a topic for another paper (see De Monticelli 1998).

Notes

Thanks to Peter Van Inwagen, who quoted this beautiful verse on occasion of a nice discussion, and even provided the reference!

A first version of this paper was presented in Geneva on occasion of the concluding Philosophical Workshop of the DEA “La personne: Philosophie, Epistémologie, Ethique,” June 2004. I wish to express my gratitude to P. V. Inwagen and L. Baker, who were present as invited speakers, for their illuminating remarks.

Leibniz (1988), p.165. : “What is not really one being is not even really a being ,” Leibniz’ emphasis.

Hering (1921). The idea of individual essences was in fact circulating among phenomenologists of the first generation, in particular those among them who worked at the foundations of a personology—and of the regional ontology appropriated to it. We find relevant insights on the ontology, as well as on the epistemology of essential individuality in Max Scheler’s and Edith Stein’s works. See De Monticelli (2000)

In so far as nineteenth century continental philosophy depends on Kant, it is no exception to the dominance of the DMI. Singularity is not thought otherwise as through an epistemological criterion of a Kantian kind (the “multiplicity of empirical intuition”). This is particularly evident in Hegel’s Phenomenolologie des Geistes, see the Section Bewusstsein, the dialectics of Sensible Certainty.

Hering (1921). The idea of individual essences was in fact circulating among phenomenologists of the first generation, in particular those among them who worked at the foundations of a personology—and of the regional ontology appropriated to it. We find relevant insights on the ontology, as well as on the epistemology of essential individuality in Max Scheler’s and Edith Stein’s works. See De Monticelli (2000)

References

Baker, L. (2000). Persons and bodies: A constitution view. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berkeley, G. (1948). Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous. In A. Luce & T. E. Jessop (Eds), The works of George Berkeley. London: Nelson.

De Monticelli, R. (1998). La conoscenza personale. Introduzione alla fenomenologia, Guerini e associati, Milano.

De Monticelli, R. (2000). Individuality and mind. In Proceedings of the International Conference, The Emergence of the Mind. Milano: Fondazione Carlo Erba.

De Monticelli, R. (2004). Leibniz on Essental Individuality. In G. Tomasi, (Ed.), Proceedings of International Symposium on Leibniz, Studia Leibnitiana

Goodman, N. (1977). The structure of appearance. Dordrecht: Reidel

Gracia, J. J. (1983). Individual as instances. «The review of metaphysics». Sept., XXXVII, 1, 145.

Gracia, J. J. (1988). Individuality: An essay on the foundations of metaphysics. Albany, N.Y.: State University of N.Y. Press.

Hering, J. (1921). Bemerkungen über das Wesen, die Wesenheit und die Idee. In Jahrbuch für philosophie und phaenomenologische Forschung. IV, Halle.

Hume, D. (1958). A treatise of human nature. In L. A. Selby-Bigge (Ed.), London: Oxford University Press.

Leibniz, G. W. (1988). Discours de métaphysique et correspondence avec Arnauld. 30/4/1687, Paris: Vrin.

Leibniz, G. W. (1990). Nouveaux essais sur l’entendement humain. éd. par J. Brunschwig. Paris: Flammarion.

Locke, J. (1975). An essay concerning human understanding. P. H. Nidditch (Ed.), Oxford: Clarendon.

Strawson, P. F. (1963). Individuals. An essay in descriptive metaphysics. Garden City, N.J.: Anchor.

Van Inwagen, P. (1980). Philosophers and the words «human body». In P. van Inwagen (Ed.), Time and cause: Essays presented to Richard Taylor. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Van Inwagen, P. (1995). Material beings. Ithaca N.Y. [etc.]: Cornell University Press.

Van Inwagen, P. (2001). Materialism and the psychological continuity account of personal identity. In Ontology, Identity and Modality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Monticelli, R. Subjectivity and essential individuality: A dialogue with Peter Van Inwagen and Lynne Baker. Phenom Cogn Sci 7, 225–242 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-007-9047-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-007-9047-1