Abstract

Background

Economic evaluation is crucial for healthcare decision-makers to select effective interventions. An updated systematic review of the economic evaluation of pharmacy services is required in the current healthcare environment.

Aim

To conduct a systematic review of literature on economic evaluation of pharmacy services.

Method

Literature (2016–2020) was searched on PubMed, Web of Sciences, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and SpringerLink. An additional search was conducted in five health economic-related journals. The studies performed an economic analysis describing pharmacy services and settings. The reviewing checklist for economic evaluation was used for quality assessment. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio and willingness-to-pay threshold were the main measures for cost-effective analysis (CEA) and cost-utility analysis (CUA), while cost-saving, cost–benefit-ratio (CBR), and net benefit were used for cost-minimization analysis (CMA) and cost–benefit analysis (CBA).

Results

Forty-three articles were reviewed. The major practice settings were in the USA (n = 6), the UK (n = 6), Canada (n = 6), and the Netherlands (n = 6). Twelve studies had good quality according to the reviewing checklist. CUA was used most frequently (n = 15), followed by CBA (n = 12). Some inconsistent findings (n = 14) existed among the included studies. Most agreed (n = 29) that pharmacy services economically impact the healthcare system: hospital-based (n = 13), community pharmacy (n = 13), and primary care (n = 3). Pharmacy services were found to be cost-effectiveness or cost-saving among both developed (n = 32) and in developing countries (n = 11).

Conclusion

The increased use of economic evaluation of pharmacy services confirms the worth of pharmacy services in improving patients’ health outcomes in all settings. Therefore, economic evaluation should be incorporated into developing innovative pharmacy services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact statements

-

Pharmacy services contribute clinical benefits, save costs, and are cost-effective. They should be acknowledged as a part of healthcare services while developing new programmes and interventions.

-

An increased trend in the economic evaluation of pharmacy service underlines its importance for policy decision-making. Thus, it should be incorporated into developing future innovative pharmacy services globally.

-

Economic evaluation of pharmacy services in primary care settings remains limited. Therefore, further studies are needed to confirm the benefit in such areas.

Introduction

An economic evaluation of healthcare compares alternative options in terms of costs and consequences [1]. This assessment has become increasingly used by policymakers as it helps to decide on interventions or technology to be included in health benefit schemes. Alternative options refer to new ways to increase population health outcomes [2]. Four economic evaluation methods currently being used include cost-minimisation analysis (CMA), cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), cost–benefit analysis (CBA), and cost-utility analysis (CUA). Each method is used for a different purpose. The CMA is appropriate when the equivalence of healthcare alternatives has already been proven. The CBA uses a welfarist approach which is concerned with an individual’s judgement on how a particular consequence affects individual wellbeing [3]. The outcome of CBA has to be transformed into monetary units. CEA is frequently considered when comparing effectiveness using the clinical outcomes of interventions. CUA is commonly used for policy decision-making and considers the health-related quality of life (quality-adjusted life-year; QALY) as a measure of effectiveness [4].

A systematic review of the literature on the economic evaluation of pharmacy services between 2010 and 2015 revealed that pharmacy services tend to be cost-effective in improving medication-related outcomes and quality of life [5]. After 2015, two similar systematic reviews were published that only focused on community pharmacy. One reported the benefit of the community pharmacist in improving clinical outcomes of patients with chronic diseases [6]. However, these findings contradict the European-based review indicating insufficient evidence to prove the cost-effectiveness for community settings [7].

This study explores global literature on economic evaluation for pharmacy services and their economic impacts. This is to provide a wider perspective by covering pharmacy service in all settings and to update findings from a previous systematic review [5].

Aim

To conduct a systematic review of literature on economic evaluation of pharmacy services.

Method

A standard approach for conducting systematic reviews, PRISMA, was employed [8].

A literature search was performed through PubMed, Web of Sciences, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Springerlink. Five health economic-related journals were searched: Health Policy, Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, Journal of Health Economics, Pharmacoeconomics, and The European Journal of Health Economics. Moreover, PlosOne, PlosMedicine, and Nature databases were searched. For the health economic-related journals, the only keyword used was ‘pharmacy service’. A manual search of the references for the included articles was also performed. The search was limited to literature written in the English language. The search was limited from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2020. The following search terms were used: “health economics” and “evaluation” “assessment” or “appraisal,” “methods,” “hospital” or “community” or “residential care,” “pharmacy” or “pharmacy services” and “cost-minimization analysis” or “cost-utility analysis” or “cost-effectiveness analysis” or “cost–benefit analysis” (Supplementary material 1). The systematic review web application (rayyan.qcri.org) was used to screen and select the recruited articles [9]. This review obtained the PROSPERO registration number CRD42021266620 before conducting the study.

Selection of studies

Identified studies were selected based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria: (1) economic analysis undertaken using a modelling approach or along with experimental studies such as randomised controlled trials, non-randomised controlled trials, cross-sectional studies, and retrospective studies; (2) Studies must describe the details of pharmacy services, and the setting of services must be specified. Exclusion criteria: Review articles, case reports, news reports, editorials, commentaries, and opinions were excluded. The PICO elements that framed the selection criteria are listed in Table 1.

Article selection and data extraction

Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts according to the inclusion criteria. Conflicts were resolved by a senior author. The full texts of the selected articles were reviewed by two researchers. Eligible articles were then evaluated and extracted using the following items: authorship, year of publication, location/region of study, economic evaluation method, study design, study perspective, time horizon, discounting, clinical outcomes and economic outcomes. A third opinion was sought if disagreements arose between the two researchers.

Study quality assessment

The quality assessment of individual studies was performed using a tool-‘Reviewing economic evaluations: a checklist’-which contains fifteen review questions with thorough descriptions for assessment [10]. All studies were first evaluated by KS, then a random sample of 9 manuscripts (~ 20%) was re-evaluated by PS to confirm and validate the assessment’s results [11]. We used 80% of the total items [12] (‘yes’ given to at least 12 items) to primarily indicate ‘good quality’ for individual studies.

Analysis of included studies

The results from the base-case analysis were primarily drawn and considered to indicate the value for money. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was used for CEA and CUA. Pharmacy interventions that demonstrated ‘lower cost-better effects’ for economic outcomes were considered cost-effective. Conversely, the intervention was not cost-effective if it demonstrated a poorer health outcome. The willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold indicated cost-effective intervention for CEA and CUA results that fell within the costlier and more effective range; thus, the WTP threshold value must be specified. The intervention was considered cost-effective when the ICER was below the threshold. The study was indicated as CEA; however, QALY was an outcome. Hence this study should be regarded as a CUA analysis. The measures used for CMA and CBA were cost-saving, cost-benefit ratio (CBR), and net benefit. The results were interpreted as cost-saving or cost-beneficial, whichever was appropriate. When the above information was not specified, the interpretation was deemed unclear. The included studies were grouped using a set of pharmacy services and settings for delivery to summarise their economic impacts. The findings are described by a narrative synthesis approach.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

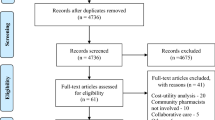

The search identified 2261 potential articles. Two hundred and seventy-eight articles were excluded as they were duplicate articles. All titles and abstracts were screened, and another 1,837 articles were excluded for the following reasons: the study was not an economic evaluation (n = 970), not pharmacy-related (n = 674), not a research article (n = 120), was a background article (n = 71), and the publication date was not within 2016–2020 (n = 2). Finally, 146 articles were screened. Ultimately, 43 full-text articles were included in the study (Fig. 1).

A PRISMA flow diagram describing the study selection process [13]. Reasons to exclude 1837 records were: the study was not an economic evaluation (n = 970); not pharmacy-related (n = 674); not a research article (n = 120); was a background article (n = 71); was published before 2016 or after 2020 (n = 2)

The number of publications by year was plotted to reveal the growth of economic evaluation studies. Eight to ten studies were published annually between 2016 and 2020 (Fig. 2). Based on the review of 43 publications, the economic evaluation of pharmacy services was predominantly based in the US (n = 6) [14,15,16,17,18,19], the UK (n = 6) [20,21,22,23,24,25], Canada (n = 6) [26,27,28,29,30,31], and the Netherlands (n = 6) [32,33,34,35,36,37]. Pharmacy services in the studies were delivered via three settings: hospital (n = 20, Table 2) [14, 16, 17, 24, 25, 32, 34, 35, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49], community pharmacy (n = 20, Table 3) [18,19,20,21,22,23, 26,27,28,29,30,31, 33, 36, 37, 50,51,52,53,54], and primary care (n = 3, Table 4) [15, 55, 56]. Various perspectives were focused on, and the healthcare provider’s or hospital’s perspective was mostly taken (n = 22) [14, 16,17,18,19, 21, 24, 27, 29, 30, 35, 39, 42,43,44,45, 49, 51, 53, 55, 56]. In contrast, four studies did not specify this [32, 38, 47, 48]. The time horizon varied from the shortest (24 h after discharge) [32] to the longest being lifetime [15, 22, 23, 29, 31, 44, 54] or 100 years [20]. Thirteen studies applied discounting to the analysis: both costs and outcomes (n = 9) [15, 17, 22, 23, 26, 29, 31, 54, 56], and only cost (n = 4) [19, 20, 27, 41] with the discounting value ranging from 1–5%. The national consumer price index was used in five studies [27, 33, 49, 53, 55], whereas one study used price discounts and inflation rates [39].

Number of publications by year 2010–2015 data drawn from the previous work by Gammie et al. [5]

Quality of included studies

Twelve studies adhered strictly to the reviewing checklist [10], they followed to at least 12 assessment questions [15, 17, 20, 22, 23, 27, 29, 31, 33, 41, 54, 56]. The time horizon was vaguely stated in seven studies [18, 21, 28, 34, 38, 48, 49], but one did not specify this. Only four studies accounted for equity consideration by conducting a subgroup analysis [22, 29, 33, 54]. Four studies did not apply discounting in their analyses despite the time horizon being over one year [25, 40, 44, 55]. Seven studies lacked performing the sensitivity analysis [18, 19, 36, 38, 39, 42, 46] (Supplementary material 2).

Methods used for the economic evaluation of pharmacy services

Cost utility analysis (CUA)

CUA was used in fifteen studies to evaluate the cost-utility of a range of pharmacy services: pharmaceutical care [15, 25, 41, 46, 47], health screening or diagnostic testing [20, 31, 54], medicines use review [53], medication therapy management [17, 29], new medicine service [22, 23], prescribing [26], and minor ailments [50]. All these studies presented QALY as the main outcome. Model-based analysis was conducted to predict cost-effectiveness for a longer time horizon [15, 17, 20, 22, 26, 31, 41, 54], while a trial-based was often used when the time horizon was less than a year [25, 46, 47, 50, 53].

Cost effectiveness analysis (CEA)

CEA was used in nine studies to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of pharmaceutical care [18, 55, 56], health screening or diagnostic screening [27], medication use review [37, 43], medication therapy management [14], prescribing [44], and smoking cessation [21]. Six studies performed economic evaluation alongside randomised trials [14, 18, 37, 43], quasi-experiments [55], or retrospective observations [21]. Six studies observed the economic outcomes for at least one year [14, 37, 56] or up to a lifetime [44]. Modelling was used in only three studies [27, 44, 56]. The outcome was mainly the number of patients who achieved the clinical goal, such as patient’s blood pressure controlled in the year [55], a person achieved good refill adherence [18], and others.

Cost utility analysis (CUA) and cost effectiveness analysis (CEA)

Five studies performed using both CEA and CUA. These studies included cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of pharmaceutical care [33], medication management therapy [19, 36], and prescribing in community pharmacies. Only one study evaluated hospital-based pharmaceutical care [34]. Four studies collected costs and outcomes alongside the randomised trial [33, 34] and quasi-experiment [19, 36], while one study was model-based [30]. Three studies reported an incremental analysis, stating incremental cost per unit of achieving clinical outcomes and per QALY gained [19, 33, 34].

Cost benefit analysis (CBA)

Twelve studies used CBA. These studies evaluated the cost–benefit of pharmaceutical care [38, 40, 42, 48], health screening or diagnostic testing [51], medicine use review [45, 52], medication reconciliation [16, 24, 32], antibiotic stewardship [39], and home medicine use review [49]. CBA was frequently used for evaluating hospital-based pharmacy services [16, 24, 32, 38,39,40, 42, 45, 48, 49], but only in two studies were conducted in community pharmacy setting [51, 52]. Five studies observed outcomes retrospectively. The other studies collected data alongside the randomised trial [49, 52], quasi-experiment [32, 39], cross-sectional study [51], and prospective cohort [40], whereas one study was done through the model-based [16]. All studies reported clinical and economic outcomes with appropriate CBA measures: net benefit or CBR. Nevertheless, none of these studies focused on patients or societal perspectives.

Cost minimisation analysis (CMA)

CMA was used in two studies: one hospital-based parenteral injection preparation [35] and one strep-throat test in a community pharmacy [28]. Both studies used a model approach for analysis from the payer’s [28] and provider’s perspectives [35]. Neither of them provided evidence of effectiveness equivalence between the comparators and alternatives.

Economic impacts of pharmacy services

Pharmacy services contributed to economic benefit for the healthcare system. The studies based in developed countries (n = 32) mainly evaluated hospital-based and community pharmacy services. The rest from developing countries (n = 11) predominantly examined hospital-based and primary primary-care pharmacy services.

Hospital-based pharmacy services

Hospital-based pharmaceutical care was the major service provided [25, 38, 40, 41, 47, 48], followed by medication reconciliation [16, 24, 32]. Most of these services provided good value for money. Among 20 hospital-based studies, 13 demonstrated that hospital-based pharmacy services were cost-effective. Pharmaceutical care provided to outpatients in the UK [25] and patients using warfarin in Taiwan [41] was cost-effective, reporting the incremental cost per QALY being under the national WTP threshold.

Pharmaceutical care in Taiwan [42], South Korea [48], and China [38] also reported a net benefit for patients with haematologic diseases, those undergoing liver transplants, and those in outpatient clinics. Medicine use reviews for chemotherapy prescriptions in South Korea were also beneficial [45]. Medication management provided for the elderly with acute coronary syndrome [17] was cost-effective. Medication reconciliation delivered for cardiovascular disease [16], intensive care [32], and internal medicine [24] was a cost-saving alternative compared to the usual care. Antibiotic stewardship [39], home medicine use review [49], and injection preparation [35] were also cost-saving. Nonetheless, several studies reported contradicting results (Table 2).

Community pharmacy service

Health screening or diagnostic testing was the service frequently explored in economic evaluation [20, 27, 28, 31, 51, 54], followed by medicine use review [37, 52, 53], and medication therapy management [19, 29, 36]. Community pharmacist delivered screening for diabetes in Japan [54] and testing for hepatitis C virus in the UK [20], both were found to be cost-effective.

A rapid diagnostic test performed by community pharmacists to identify malaria and strep throat also contributed a net benefit in Nigeria [51] and Canada [28]. Medicine use review for Italian asthmatic [53] and Spanish polypharmacy [52] was cost-effective. Medication management therapy in the US for HIV [19] and in Canada for cardiovascular disease [29] was cost-effective. The UK-based studies examined the new medication service for chronic disease and minor ailments and were also cost-effective [22, 23]. Canadian pharmacy prescribing [26], Australian minor ailment service [50], and UK smoking cessation [21] were also cost-effective. However, few other studies revealed inconsistent findings (Table 3).

Primary care pharmacy service

One study was performed using CUA [15], and two employed CEA [55, 56] for pharmacy services in primary care. Several studies reported that pharmaceutical care was cost-effective for chronic diseases. This was observed in Jordan [56], the US [15], and Brazil [55] (Table 4).

Discussion

Statement of key findings

This systematic review demonstrated that the number of published studies on the economic evaluation of pharmacy services noticeably increased between 2010 and 2020 compared to previous years [5]. Some studies reported diverse findings (14 out of 43); however, most studies in this review (29 out of 43) agreed that pharmacy services would result in improving health outcomes and they are ‘value for money’. The results in this review are consistent with those of previous reviews of pharmacy interventions. [57,58,59]

Uaviseswong et al. reported that pharmacist interventions provided economic benefits and saved the cost of preventable adverse drug events [57]. This was due to a reduction in medication errors. In China, antimicrobial management, chronic disease management, and multidimensional clinical pharmaceutical services were associated with cost-saving and improved patient outcomes [58]. US-based clinical pharmacy services, including pharmacotherapy, disease management, ambulatory care, and those provided in community pharmacies are more effective at a lower cost [59].

Evidence is also well established that optimal hospital pharmacy is cost-saving and community pharmacy services are cost-effective. Hospital pharmacy services are often related to providing pharmaceutical care [25, 38, 41, 42, 48] and medication reconciliation [16, 24, 32]. This is also evident from a Jordanian home medication use review, showing that hospital pharmacy services could result in cost-saving [49]. This also indicates the possibility of hospital pharmacist’s involvement in primary care.

Community pharmacies are involved in improving medication use, such as medicine use review [52, 53], medication therapy management [19, 29], and new medication service [22, 23]. They also screen for issues, such as health-related risks of chronic [54] and infectious diseases [20, 28, 51]. These findings reiterate that pharmacy service is increasingly acknowledged as an important part of health service system.

In many countries, such as the UK [60], Canada [61], Europe and others [62], some pharmacy services are part of the national health benefit package, which means they are remunerated by the public payer [63]. The number of studies from the developed countries was about three times higher than that from the developing ones. However, they have similar findings showing cost-effectiveness or cost-saving of pharmacy services across the board.

Regarding the use of the economic evaluation method, Costa et al. reported that CEA is the most common type of economic analysis used, followed by CUA [63]. However, CUA is the most commonly used approach in the community pharmacy setting. This approach typically uses QALY as an outcome, making the cost-effectiveness results comparable to other interventions for any disease.

Cost-benefit analysis is often used to evaluate hospital-based pharmacy services using monetary outcomes such as cost avoided from adverse events [48] and cost of inappropriate prescription [38].

Several tools/checklists are available for assessing the quality of economic evaluation for example the Drummond checklist, BMJ checklist (15.8%), and CHEERS statement [12]. We used the one proposed by the Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence, Australia because of its thorough definition of assessment [10]. Nonetheless, the items in those tools/checklists are very similar. Only about one-third (12 out of 43) of the included studies were of good quality.

The previous reviews have also shown that challenges emerged in evaluating pharmacy services due to methodological complexities [63, 64]. All studies in this review fulfilled three criteria: (1) a well-defined objective; (2) the target group clearly stated; (3) the relevant costs and outcomes were identified. Transferability was found to be difficult to judge since the pharmacy intervention is specific to each country, and the resource inputs vary from one setting to another.

Strengths and weaknesses

This review synthesised global literature regarding the use of economic evaluation methods and covers pharmacy service in broader settings, distinguished from the previous ones which focused on one particular aspect: the cost-effectiveness of pharmacy service in the community setting [7] and clinical pharmacy service [58], while two other reviews focused on economic evaluation methodologies [63, 64].

This review has the strength that it gathered a large number of economic evaluation studies. The review does not include unpublished studies. Various databases and specific journals were searched; however, a few other databases were not included (e.g. NHS EED, CRD, EBSCO). This may lead to a few missing articles.

Interpretation and future research

There is an increasing trend to use economic evaluation for pharmacy services globally, this underlines its importance for policy-making decision. This also implies that it should be incorporated into developing future innovative pharmacy service models. However, performing economic evaluation is challenging due to its methodological complexities and lack of workforce in this area. Additionally, performing economic evaluation is specific to the context of each country. Similar interventions are used; nonetheless, the evaluation results may differ between countries.

Conclusion

The increased use of economic evaluation of pharmacy services confirms that pharmacy services can contribute economic impacts and improve patients’ health outcomes in all settings: hospitals, community pharmacies, and primary care. Cost utility and cost-benefit analyses were found to be the common approaches used to assess pharmacy services. Economic evaluation underlines its importance for policy-making decisions and thus should be incorporated into developing innovative pharmacy services.

References

Turner HC, Archer RA, Downey LE, et al. An introduction to the main types of economic evaluations used for informing priority setting and resource allocation in healthcare: key features, uses, and limitations. Front Public Health. 2021;9:772977.

Drummond MF, Sculphaer MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 4th ed. London: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Culyer AJ, Chalkidou K. Economic evaluation for health investments en route to universal health coverage: cost-benefit analysis or cost-effectiveness analysis? Value Health. 2019;22:99–103.

Arnold RJG. Pharmacoeconomics from theory to practice. New York: CRC Press; 2021. p. 4561.

Gammie T, Vogler S, Babar ZD. Economic evaluation of hospital and community pharmacy services: a review of the literature (2010–2015). Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51:54–65.

Newman TV, San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Parekh N, et al. Impact of community pharmacist-led interventions in chronic disease management on clinical, utilization, and economic outcomes: an umbrella review. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;16:1155–65.

Perraudin C, Bugnon O, Pelletier-Fleury N. Expanding professional pharmacy services in European community setting: is it cost-effective? A systematic review for health policy considerations. Health Policy. 2016;120:1350–62.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021:n71.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210.

Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence. Reviewing economic evaluations: a checklist. Sydney: New Sounth Wales Ministry of Health; 2021.

Foot H, Scott I, Sturman N, et al. Impact of pharmacist and physician collaborations in primary care on reducing readmission to hospital: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2022;18:2922–43.

Min C, Xue M, Haotian F, et al. An overview of the characteristics and quality assessment criteria in systematic review of pharmacoeconomics. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:1–13.

Haddaway NR, Page MJ, Pritchard CC, et al. PRISMA2020: an R package and shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev. 2022;18:e1230.

Dehmer SP, Maciosek MV, Trower NK, et al. Economic evaluation of the home blood pressure telemonitoring and pharmacist case management to control hypertension (Hyperlink) trial. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2018;1:21–30.

Kulchaitanaroaj P, Brooks JM, Chaiyakunapruk N, et al. Cost-utility analysis of physician-pharmacist collaborative intervention for treating hypertension compared with usual care. J Hypertens. 2017;35:178–87.

Najafzadeh M, Schnipper JL, Shrank WH, et al. Economic value of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation for reducing medication errors after hospital discharge. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22:654–61.

Okere AN, Ezendu K, Berthe A, et al. An evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of comprehensive MTM integrated with point-of-care phenotypic and genetic testing for U.S. elderly patients after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24:142–52.

Shireman TI, Svarstad BL. Cost-effectiveness of Wisconsin TEAM model for improving adherence and hypertension control in black patients. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2016;56:389–96.

Shrestha RK, Schommer JC, Taitel MS, et al. Costs and cost-effectiveness of the patient-centered HIV care model: a collaboration between community-based pharmacists and primary medical providers. Prev Res. 2020;85:e48-54.

Buchanan R, Cooper K, Grellier L, et al. The testing of people with any risk factor for hepatitis C in community pharmacies is cost-effective. J Viral Hepat. 2019;00:1–9.

Csikar JI, Douglas GV, Pavitt S, et al. The cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation services provided by general dental practice, general medical practice, pharmacy and NHS stop smoking services in the North of England. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44:119–27.

Elliott RA, Tanajewski L, Gkountouras G, et al. Cost effectiveness of support for people starting a new medication for a long-term condition through community pharmacies: an economic evaluation of the new medicine service (NMS) compared with normal practice. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35:1237–55.

Elliott RA, Boyd MJ, Tanajewski L, et al. “New medicine service”: supporting adherence in people starting a new medication for a long-term condition: 26-week follow-up of a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:286–95.

Onatade R, Quaye S. Economic value of pharmacy-led medicines reconciliation at admission to hospital: an observational UK-based study. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2018;25:26–31.

Twigg MJ, Wright D, Barton G, et al. The pharmacy care plan service: Evaluation and estimate of cost-effectiveness. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15:84–92.

Al Hamarneh YN, Johnston K, Marra CA, et al. Pharmacist prescribing and care improves cardiovascular risk, but is it cost-effective? A cost-effectiveness analysis of the RxEACH study. Can Pharm J. 2019;152:257–66.

Coronado AC, Zaric GS, Martin J, et al. Diabetic retinopathy screening with pharmacy-based teleophthalmology in a semiurban setting: a cost-effectiveness analysis. C Open. 2016;4:E95–102.

Lathia N, Sullivan K, Tam K, et al. Cost-minimization analysis of community pharmacy-based point-of-care testing for strep throat in 5 Canadian provinces. Can Pharm J. 2018;151:322–31.

Tam-Tham H, Clement F, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. A Cost analysis and cost-utility analysis of a community pharmacist–led intervention on reducing cardiovascular risk: the Alberta vascular risk reduction community pharmacy project (RxEACH). Value Health. 2019;22:1128–36.

Sanyal C, Husereau DR, Beahm NP, et al. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact of the management of uncomplicated urinary tract infection by community pharmacists. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–13.

Tarride J-E, Dolovich L, Blackhouse G, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation in Canadian pharmacies: an economic evaluation. C Open Joule Inc. 2017;5:653–61.

Bosma LBE, Hunfeld NGM, Quax RAM, et al. The effect of a medication reconciliation program in two intensive care units in the Netherlands: a prospective intervention study with a before and after design. Ann Intensiv Care. 2018;8:1–13.

Bosmans JE, Van Der Laan DM, Yang Y, et al. The cost-effectiveness of an intervention program to enhance adherence to antihypertensive medication in comparison with usual care in community pharmacies. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1–10.

Karapinar-Çarkit F, Van Der Knaap R, Bouhannouch F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a transitional pharmaceutical care program for patients discharged from the hospital. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:1–20.

Larmené-Beld KHM, Spronk JT, Luttjeboer J, et al. A Cost minimization analysis of ready-to-administer prefilled sterilized syringes in a Dutch hospital. Clin Ther. 2019;41:1139–50.

Van Boven JFM, Stuurman-Bieze AGG, Hiddink EG, et al. Effects of targeting disease and medication management interventions towards patients with COPD. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:229–39.

van der Heijden AAWA, de Bruijne MC, Nijpels G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a clinical medication review in vulnerable older patients at hospital discharge, a randomized controlled trial. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41:963–71.

Bao Z, Ji C, Hu J, et al. Clinical and economic impact of pharmacist interventions on sampled outpatient prescriptions in a Chinese teaching hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:1–9.

Borde JP, Nussbaum S, Hauser S, et al. Implementing an intensified antibiotic stewardship programme targeting daptomycin use in orthopaedic surgery: a cost–benefit analysis from the hospital perspective. Infection. 2016;44:301–7.

de Cazarim MS, Rodrigues JPV, Calcini PS, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of pharmacist interventions over 36 months in a university hospital. Rev Saude Publica. 2020;54:1–13.

Chang J-Y, Wang C, Kang H-C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the pharmacist-assisted warfarin monitoring program at a medical center in Taiwan. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2017;29:817–25.

Chen PZ, Wu CC, Huang CF. Clinical and economic impact of clinical pharmacist intervention in a hematology unit. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020;26:866–72.

Gallagher J, O’Sullivan D, McCarthy S, et al. Structured pharmacist review of medication in older hospitalised patients: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Drugs Aging. 2016;33:285–94.

Hale A, Merlo G, Nissen L, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of doctor-pharmacist collaborative prescribing for venous thromboembolism in high risk surgical patients 11 medical and health sciences 1117 public health and health services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:1–6.

Han J-M, Ah Y-M, Suh SY, et al. Clinical and economic impact of pharmacists’ intervention in a large volume chemotherapy preparation unit. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:1124–32.

Mateti UV, Nagappa AN, Attur RP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pharmaceutical care on patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis–a multicenter randomized controlled study. Postgrad Med. 2018;130:621–6.

Tanaka K, Tachi T, Hori A, et al. Cost utility analysis of pharmacist counseling care for breast cancer chemotherapy outpatients. Pharmazie. 2019;74:439–42.

Ah YM, Lee JY, Moon MR, et al. Clinical and economic evaluation of pharmacists’ contribution to patient care on a multi-disciplinary liver transplant team. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;54:102–9.

Al-Qudah RA, Al-Badriyeh D, Al-Ali FM, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of clinical pharmacist intervention in preventing adverse drug events in the general chronic diseases outpatients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26:115–24.

Dineen-Griffin S, Vargas C, Williams KA, et al. Cost utility of a pharmacist-led minor ailment service compared with usual pharmacist care. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2020;18:1–13.

Ezennia IJ, Nduka SO, Ekwunife OI. Cost benefit analysis of malaria rapid diagnostic test: the perspective of Nigerian community pharmacists. Malar J. 2017;16:1–10.

Malet-Larrea A, Goyenechea E, Gastelurrutia MA, et al. Cost analysis and cost-benefit analysis of a medication review with follow-up service in aged polypharmacy patients. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18:1069–78.

Manfrin A, Tinelli M, Thomas T, et al. A cluster randomised control trial to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Italian medicines use review (I-MUR) for asthma patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:1–13.

Shono A, Kondo M, Hoshi S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a new opportunistic screening strategy for walk-in fingertip HbA1c testing at community pharmacies in Japan. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1218–26.

de Cazarim MS, Pereira LRL. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pharmaceutical care for hypertensive patients from the perspective of the public health system in Brazil. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–16.

Mousa R, Hammad E. Cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-led care versus usual care in type 2 diabetic Jordanians: a Markov modeling of cardiovascular diseases prevention. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;21:1069–79.

Uaviseswong T, Chaikledkaew U, Tragulpiankit P. Systematic review of economic evaluation of pharmacist intervention related to adverse drug event prevention among patients with hospitalization. Mahidol Univ J Pharm Sci. 2012;39:38–43.

Mi X, Su X, Jin Z, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services in China: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2020;10:1–13.

Talon B, Perez A, Yan C, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services in the United States: 2011–2017. JACCP J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3:793–806.

Social Care. PSNC Briefing 026/21: community pharmacy funding in 2022/22 [Internet]. Funding Stat. 2021. Available from: https://psnc.org.uk/our-news/community-pharmacy-funding-in-2021-22/. Accessed 13 April 2022.

Canadian Pharmacist Association. Canadian pharmacy services framework [Internet]. 2011. Available from: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/CanadianPharmacyServicesFramework. Accessed 13 April 2022.

Bates I, Bader LR, Galbraith K. A global survey on trends in advanced practice and specialisation in the pharmacy workforce. Int J Pharm Pract. 2020;28:173–81.

Costa S, Cary M, Helling DK, et al. An overview of systematic reviews of economic evaluations of pharmacy-based public health interventions: addressing methodological challenges. Syst Rev. 2019;8:1–20.

Elliott RA, Putman K, Davies J, et al. A review of the methodological challenges in assessing the cost effectiveness of pharmacist interventions. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:1185–99.

Acknowledgements

We thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This research project was financially supported by the Mahasarakham University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Phimarn, W., Saramunee, K., Leelathanalerk, A. et al. Economic evaluation of pharmacy services: a systematic review of the literature (2016–2020). Int J Clin Pharm 45, 1326–1348 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01590-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01590-0