Abstract

Background Currently, there is no literature describing what a quality level of practice entails in Polish neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), nor are there any means of currently measuring the quality of pharmaceutical care provided to NICU patients. Objective To identify a set of essential pharmacist roles and pharmacy-relevant key performance indicators (KPI’s) suitable for Polish neonatal intensive units (NICUs). Setting Polish hospital pharmacies and NICUs. Method Using a modified Delphi technique, potential KPI’s structured along Donabedian’s domains as well as pharmacy services were presented to an expert panel of stakeholders. Two online, consecutive Delphi rounds, were completed by panellists between August and September 2017. Main outcome measure To identify the minimum level of pharmacy services that should be consistently provided to NICU patients. Results A total of 16 panellists contributed to the expert panel. Overall, consensus of 75% was reached for 23 indicators and for 28 roles. When considering pharmacy services for the NICU, the experts were found to highly value traditional pharmacy roles, such as dispensing and extemporaneous compounding, however, they were still eager for roles in the other domains, such as educational and clinical services, to be listed as essential for NICU practice. Panellists were found to positively value the list of indicators presented, and excluded only 9 out of the total list. Conclusion There is a need for future research to establish a minimum standard of practice for Polish pharmacists to encourage the progression and standardisation of hospital pharmacy services to meet the level of practice seen in NICUs worldwide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impacts on practice

-

The integration of the clinical pharmacist into NICU settings in Poland must be considered.

-

Quality pharmacy practice resources in Poland should be further developed for hospital pharmacy practice. These resources are important for quality improvement activities, as well as enhancing transparency about hospital pharmacy service quality, which are important for the progression of hospital pharmacy practice.

Introduction

Despite its widespread adoption and implementation in the US, UK, Australia and Canada, clinical pharmacy practice within hospital settings in Poland is still in its infancy [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Indeed, hospital pharmacy practice as a whole is predominantly limited to dispensary-based activities focussed on the safety and effectiveness of medicines rather than patient-centred care. Pawlowska et al. [7] highlighted that only 7% of hospital pharmacists surveyed had contact with patients, and that their roles in the hospital were mainly associated with the provision of medicines. Piecuch [8] further indicated that pharmacists are not involved in the provision of direct, individualised care to patients and as such often have little to no input in the pharmacotherapy decision-making process. Whilst pharmacists have the ability to acquire post-graduate specialisations in clinical and hospital pharmacy, their skills in these fields are unable to manifest on hospital wards due to several barriers. These include: lack of appropriate legislation specifically outlining the authority of the pharmacist in this setting, insufficient staffing of hospital pharmacies, lack of financing for additional pharmaceutical care services as well as a limited awareness of other members of the healthcare team towards the possible benefits of pharmacist involvement in the hospital structure [9].

Studies worldwide indicate that pharmacists are an integral component of patient care, and demonstrate their impact upon optimising patient outcomes, improving the rational use of resources and decreasing medication error rates [2, 10,11,12]. This is of particular importance to high-risk hospitalised patient groups, especially infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). These children have a high level of exposure to medications throughout their admission, and due to their unique pharmacokinetic and physical characteristics, are prone to medication misadventure which may have significant impact upon their development [13]. Studies show that pharmacists in the NICU: have prevented significant errors from occurring, including 10–100 fold overdoses; can optimise pharmacotherapy, such as total parenteral nutrition regimens (TPN); and are highly valued by doctors and nurses on the ward [13,14,15,16,17,18].

However, clinical pharmacy services are relatively absent in the Polish hospital setting, in comparison to other countries. This raises questions relating to the quality pharmaceutical care being provided to NICU patients, and whether the services being provided are achieving the best possible patient outcomes. Healthcare service quality is most commonly measured via key performance indicators (KPIs) or other quality indicators that assess practice performance, helping to identify where improvements are needed to minimise service gaps [19]. These indicators are formulated using nationally or internationally agreed clinical practice guidelines based on meaningful, reliable evidence [20]. Currently, there is no literature describing what a quality level of practice entails in Polish NICUs, nor are there any means of currently measuring the quality of pharmaceutical care provided to NICU patients.

The European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and Healthcare (EDQM) has co-ordinated the development of generally applicable indicators for the implementation of pharmaceutical care in Europe [21]. However, these indicators have been designed for use both in community and hospital settings, and are not specific to sub-speciality patient groups, such as neonates. As such, apart from the pharmaceutical law regulating which activities should be provided by hospital pharmacies to all inpatients, there are no guidance documents to support hospitals pharmacists in meeting the needs of the neonatal patient population and they are unable to measure their performance to benchmark against other settings nationally. Scobie et al. [22] state that the measurement of safety and quality is fundamental to health delivery.

Aim of the study

The aim of this Delphi study was to identify essential pharmacist roles and KPIs that reflect quality pharmaceutical care in a Polish NICU setting. Specific objectives were to:

-

Identify a set of pharmacy-based key performance indicators in Donabedian’s domains of process, structure and outcome that can be used to benchmark the quality of pharmaceutical care provided to patients in Polish NICU settings.

-

Identify the minimum level of pharmacy services that should be consistently provided to NICU patients.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the respective ethics committees at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS), Australia (UTS HREC REF NO. ETH17-1584) and the Medical University of Gdansk (GUMed), Poland (GUMed HREC REF NO. NKBBN/424-184/2017). Panellists were assured of confidentiality and were informed that their responses would be de-identified.

Method

Panel selection

Experts were recruited using a combined purposive and criterion sampling approach [23]. Potential panellists were identified from neonatal organisations as well as data papers and articles publicly available registers in Poland including the Polish Register of Facilities delivering Medical Activities (Rejestr Podmiotow Wykonujacych Dzialalnosc Lecznicza—RPWDL) to identify hospitals with neonatal intensive care units.

The expert panel was made up of key stakeholders involved in NICU care, and were defined as: (1) hospital pharmacists, or pharmacists based in academia, as well as leading medical doctors and nurses, (2) people who had experience with hospital based clinical pharmacy services, and where possible, (3) people with experience in the NICU.

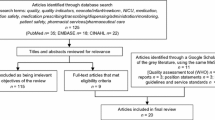

Collating pharmacy-sensitive indicators

To find quality and pharmacist-specific key performance indicators used in neonatal and paediatric care settings, a review of the literature was undertaken [24]. Due to the nature of hospital pharmacy practice in Poland (i.e., less well established level of pharmaceutical care and clinical practice; focused mainly on dispensary-based activities), the proposed indicators were carefully considered for relevance to the Polish system. Two of the researchers (NK, IP) consulted a small group of Polish health professionals to assess the applicability of indicators to current Polish pharmacy practice and canvas whether the indicators would be understood by panellists in this country. Only those indicators that pharmacists would reasonably be expected to understand in the context of current Polish pharmacy practice were included. This was based on a recent study conducted by Krzyzaniak et al. who highlighted that pharmaceutical care services delivered to NICUs in Poland were mostly dispensary based, i.e., compounding, with little to no involvement in clinical, ward-based roles [25]. Therefore, many concepts and terms such as medication reconciliation, medication action plans are foreign to Polish pharmacists. In order to minimise the incidence of misunderstanding as well as any social desirability bias, indicators that contained concepts and terms that were abstract to the Polish pharmacy practice setting were excluded. Overall, a modified list of 32 indicators, categorized according to Donabedian’s domains of structure, process and outcome, was provided to Polish panellists.

Data collection

The surveys used in the Delphi rounds were structured on the basis of two previous studies by Fernandes et al. and Wilson et al. who published a set of pharmacy and nursing indicators respectively for hospital practice [23, 26].

The study comprised two Delphi rounds, structured as two consecutive surveys delivered between August and September 2017 via the online software program Survey Monkey™. Mullen highlights that when a sample size is small, often no more than one round is needed to obtain consensus [27]. However, in order to allow feedback and ‘revision of responses’, a minimum of two rounds are recommended [27]. As the target group of individuals for this study practice within a sub-specialty of care, there are a subsequent limited number of possible participants. Therefore, a two-round Delphi survey was considered upfront as the most appropriate to ensure maximum response rate as well as to minimise the possibility of participant fatigue [28, 29]. Each Delphi round comprised three parts. These included: panellist demographics (Part A), essential pharmacist roles in the NICU (Part B) and a baseline set of key performance indicators (Part C). Panellists were asked to rate each item on a 5 point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5) against pre-set criteria (Fig. 1).

At the end of Round 1, panellists were invited to suggest additional indicators/roles and to provide any comments. These suggestions were used to rephrase questions and refine the list of indicators/roles for inclusion in the next round of surveys. In Round 2, the modified set of KPIs/roles were rated again using the same selection criteria.

Each Delphi round was open for 2 weeks, and reminders were emailed at the beginning and at the end of each 2-week period. Each survey took approximately 15 min to complete. The non-completion of the previous round did not rule out panellists from contributing to the following round. Round 1 was piloted by a small number of pharmacists.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (percentages, frequencies) were used to analyse the quantitative data, via the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 22™. All Likert scale scores listed as 1 and 2 were combined as agree, and all scores listed as 4 and 5 were combined as disagree. Scores of 3 (unsure) were excluded. Consensus was considered to have been reached when 75% or more of panellists rated ‘agreed’ for an indicator. If an indicator did not reach this consensus, it was not included in the subsequent round. All items with ≥ 75% agreement were included in the final set. According to Keeney et al. a consensus level of 75% is considered to be the minimum in ensuring accuracy and confidence in the consensus achieved by participants [30].

Results

Overall, of the 29 panellists who agreed to participate in this research, only 16 became expert panellists and participated in at least one Delphi round (response rate = 55.2%). The remaining individuals did not respond. Seven experts completed both Delphi rounds. Approximately half of panellists in each round were pharmacists or directors of pharmacy, and the remaining panellists comprised neonatologists, nurses, midwives and academic pharmacists (Table 1).

Round 1

A total of 13 panellists completed round 1.

Pharmacist roles

A list of 30 pharmacist roles was presented to panellists. Overall, respondents strongly agreed to the majority of the proposed roles. Polish experts achieved consensus for 28 roles; two services pertaining to evaluating laboratory tests (69.2%) and immunisations (46.2%) were excluded (Table 2). Using the 5-point Likert scale, the range of median scores was from 1.00 (IQR = 0) for extemporaneous compounding to 3.00 (IQR = 2) for involvement in immunisations. A new role was proposed for inclusion in the next round, that being the preparation of individual, unit dose parenteral and oral dose forms for neonatal patients.

Pharmacy-based key performance indicators for quality pharmaceutical care in the NICU

Polish experts were presented with 10 structure, 11 process and 11 outcome indicators (total = 32). A consensus of > 75% was achieved for 25 items (Table 3). Therefore, 7 items were excluded from subsequent analysis. These items included: dedicated area/station on the ward for the pharmacist (69.2%), number of education/training sessions provided by pharmacists relating to pharmacotherapy in the NICU for other health professionals (69.2%), proportion of pharmacists involved in NICU related clinical research (61.5%), monthly audit of episodes of ineffective empiric antibiotic therapy (organism/antibiotic mismatch) (69.2%), proportion of infants receiving appropriate dosing and timing of perioperative prophylaxis (69.2%), proportion of patients families that have had a face-to-face discussion about medicines related information (53.8%) and incidence of neonatal sepsis (61.5%).

Panellists did not recommend any new indicators for inclusion in round 2. Median scores for panellists ranged from 1.00 (IQR = 0) to 2.00 (IQR = 2).

Round 2

A total of 12 panellists completed round 2.

Pharmacist roles

Consensus was reached for 28 roles (Table 2). Overall, panellists responded strongly to the proposed pharmacist roles, with the majority responding ‘strongly agree’. Polish experts most strongly responded to pharmacist roles in the provision domain, including: extemporaneous compounding (100%, Median = 1.00), stocking the ward with medication (100%, Median = 1.00) and the newly added role, preparing unit doses for parenteral and oral medicines (100%, Median = 1.00). Counselling of the families of NICU patients did not reach consensus by Polish panellists (58.3%); median scores achieved by Polish experts ranged from 1.00 (IQR = 0) − 2.00 (IQR = 2) (Tables 4 and 5).

Pharmacy-based key performance indicators for quality pharmaceutical care in the NICU

A total of 25 indicators were rated by panellists, and were split across Donabedian’s domains, with 9 structure, 9 process and 7 outcome indicators. Consensus was reached for 23 indicators. Median scores were similar to the previous round for most indicators and ranged from 1.00 (IQR = 0) to 2.00 (IQR = 2). Polish panellists responded strongly throughout each of the structure, process and outcome domains, with consensus higher than 90% for the majority of indicators. Two indicators in the outcomes domain did not achieve consensus: percentage of patients who received at least 1 pain management intervention during heel sticks, PIV insertions, venipunctures, umbilical arterial catheterizations, nasogastric tube placements and EET suctioning (66.7%) and proportion of prescriptions for restricted antibiotics that are concordant with hospital approved criteria (66.7%).

Discussion

This is the first study in Poland to identify a set of pharmacist roles and KPIs that may be useful in structuring and guiding future practice in the NICU. Furthermore, this research is the first of its kind to combine the concept of clinical pharmacy practice and a sub-specialty of pharmacy, such as the NICU setting, in Poland.

In considering pharmacy services, experts highly valued traditional pharmacy roles, such as dispensing and extemporaneous compounding, but were still highly supportive of roles in the other domains, such as educational and clinical services, to be included as essential for NICU practice. These traditional perceptions may stem from ingrained practice cultures in Poland, whereby pharmacists are predominantly perceived to be based in the dispensary [7]. However, it is extremely encouraging that, despite these attitudes, medical and pharmacy staff alike are open to the pharmacists providing ward-based services to the NICU and being involved in the pharmacotherapy decision-making process. Similarly, experts expressed strong levels of support for the key performance indicators. This is of particular significance, as currently Poland does not have any national initiatives for quality assurance for hospital pharmacy practice. As such, it is encouraging that despite having little to no experience with clinical pharmacy KPIs, the experts were extremely enthusiastic towards selecting indicators, with high levels of agreement for those remaining in the final list.

These findings demonstrate that there is a need to determine a minimum standard of practice for Polish pharmacists to encourage the progression and standardisation of hospital pharmacy services to meet the level of practice seen worldwide. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the concept of health equity is a priority for healthcare systems worldwide, and it is a fundamental right of each human being to receive the highest standard of health care [31, 32]. The literature highlights that Polish pharmacists are aware of the differences in practice evident between Poland and other industrialised countries, such as Australia and the UK [8, 9, 33]. However, Urbanczyk highlights that the clinical pharmacist is simply not viewed by policy-makers or other healthcare professionals as a medicines expert, and does not hold the relevant position or authority to be able to directly influence pharmacotherapy [9]. This is a point of concern, as the studies demonstrate the positive contributions of pharmacist involvement in pharmacotherapy-related decision making and in reducing medication errors in the NICU [14, 17, 34]. Neonatal patients are a priority for each healthcare profession, and the key to stepping forward in the Polish setting is to accept the pharmacist as an essential member of the interdisciplinary therapeutic team and then develop strategies to embed pharmacists into this setting. The International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) endorses the development of standardised national pharmacy guidelines and services to identify good practices and adopt coherent policies to promote practice consistency [35]. The findings presented here may be useful for the future development of quality pharmacy practice resources in Poland. These resources are important for quality improvement activities, such as benchmarking to demonstrate differences between settings on a national scale, pharmacy practice accreditation, as well as enhancing transparency about hospital pharmacy service quality, which are important for the progression of hospital pharmacy practice in Poland [36]. The findings of this research may be transposable to practice in other countries, particularly those in Eastern Europe, as the healthcare system issues faced in Poland are similar to those experienced in these countries. This may be attributed to the impact of historical events upon the political, economic and societal climate.

Limitations

There are several limitations to consider. First, the expert panels comprised only a small number of panellists. This may be attributed to the very specific nature of this research, which may have deterred potential respondents from contributing their expertise. Therefore, this may affect the generalisability of the results and they should be interpreted with caution.

Despite the small size of the panel, care was taken to ensure that the experts who responded to the surveys reflected a range of expertise and contributed a diverse range of neonatal and pharmacy experiences. However, this panel cannot be said to be representative of each profession in Poland.

The study was undertaken in the context of the Polish healthcare system. As such, the results may not be generalizable or applicable to countries with different healthcare systems.

Furthermore, the key performance indicators are not a comprehensive set of indicators for the assessment of hospital pharmacy practice in a Polish context. They simply represent consensus amongst experts in defining a preliminary quality level of pharmacy practice in the NICU.

Conclusion

The baseline quality indicators and pharmacy services identified, give insight into what experts deem to be essential aspects of quality pharmaceutical care in Polish NICU settings. These findings are the first to consider the integration of the clinical pharmacist into NICU settings in Poland. The practical considerations of applying these indicators will need careful consideration before they can be seen as valid performance measurement tools. There are several barriers in the current healthcare system limiting pharmacy services on the NICU, which require attention. Further research is needed to established the validity, acceptability and feasibility of the proposed indicators to practice on a national level, as well as to develop strategies to further integrate the pharmacist into the NICU therapeutic team.

References

Dooley MJ, Allen KM, Doecke CJ, Galbraith KJ, Taylor GR, Bright J, et al. A prospective multicentre study of pharmacist initiated changes to drug therapy and patient management in acute care government funded hospitals. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57(4):513–21.

Gilbar P, Stefaniuk K. The role of the pharmacist in palliative care: results of a survey conducted in Australia and Canada. J Palliat Care. 2002;18(4):287–92.

Bond CA, Raehl CL. Clinical pharmacy services, pharmacy staffing, and hospital mortality rates. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Therapy. 2007;27(4):481–93.

Cotter S, Barber N, McKee M. Survey of clinical pharmacy services in United Kingdom National Health Service hospitals. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1994;51(21):2676–84.

Fertleman M, Barnett N, Patel T. Improving medication management for patients: the effect of a pharmacist on post-admission ward rounds. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(3):207–11.

Łasocha P, Merks P, Olszewska A. Farmacja szpitalna i kliniczna w Wielkiej Brytanii (Hospital and Clinical Pharmacy in the United Kingdom). Farmacja Polska. 2013;69(9):527–30.

Pawłowska I, Pawłowski L, Kocić I, Krzyżaniak N. Clinical and conventional pharmacy services in Polish hospitals: a national survey. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(2):271–9.

Piecuch A, Kozłowska-Wojciechowska M, Jaszewska E, Makarewicz-Wujec M. Farmaceuta kliniczny—odpowiedź na zmieniające się potrzeby społeczne (The Clinical Pharmacist—response to societal needs). Farm Pol. 2014;70(7):395–9.

Urbańczyk K. Czym właściwie jest Farmacja kliniczna? [What is clinical pharmacy?] Opieka Farmaceutyczna. 2017. http://opieka.farm/doniesienia/czym-wlasciwie-jest-farmacja-kliniczna/. Accessed 28 Oct 2017.

da Silva NMM. The impact of pharmacist participation in a multidisciplinary team on an oncology ward compared with a ward clinical pharmacy service. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract. 2012;19(2):259–60.

Koshman SL, Charrois TL, Simpson SH, McAlister FA, Tsuyuki RT. Pharmacist care of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(7):687–94.

Viktil KK, Blix HS. The impact of clinical pharmacists on drug-related problems and clinical outcomes. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102(3):275–80.

Krzyzaniak N, Bajorek B. Medication safety in neonatal care: a review of medication errors among neonates. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2016;7(3):102–19.

Dice J, Burckart G, Woo J, Helms R. Standardized versus pharmacist-monitored individualized parenteral nutrition in low-birth-weight infants. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1981;38(10):1487–9.

Dunkley M. Neonatal intensive care–an Australian survey of the pharmacist’s role. Aust J Hosp Pharm. 1991;21:104–8.

Gray JE, Goldmann DA. Medication errors in the neonatal intensive care unit: special patients, unique issues. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89(6):F472–3.

Simpson J, Lynch R, Grant J, Alroomi L. Reducing medication errors in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89(6):F480–2.

Stavroudis TA, Miller MR, Lehmann CU. Medication errors in neonates. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35(1):141–61.

Kruk ME, Kelley E, Syed SB, Tarp F, Addison T, Akachi Y. Measuring quality of health-care services: what is known and where are the gaps? WHO: Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95:389–389A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.195099.

Banks M, Board N, Curtis I, Davis E, Dunbar N, Jorm C. Developing a safety and quality framework for Australia. Darlinghurst: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2017.

European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and HealthCare (EDQM). Pharmaceutical Care—policies and practices for a safer, more responsible and cost-effective health system. Strasbourg: Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and HealthCare of the Council of Europe, 2012.

Scobie S, Thomson R, McNeil JJ, Phillips PA. Measurement of the safety and quality of health care. Med J Aust. 2006;184(10):S51.

Wilson S, Hauck Y, Bremner A, Finn J. Quality nursing care in Australian paediatric hospitals: a Delphi approach to identifying indicators. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(11–12):1594–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04004.x.

Krzyzaniak N, Bajorek B. Quality use of medicines in neonatal care: a review of measures of quality used to evaluate the appropriateness and rational use of medication within the NICU. Drugs Therapy Perspect. 2016;32(9):392–402.

Krzyżaniak N, Pawłowska I, Bajorek B. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the NICU: a cross-sectional survey of Australian and Polish pharmacy practice. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2018:ejhpharm-2017-001432.

Fernandes O, Gorman SK, Slavik RS, Semchuk WM, Shalansky S, Bussieres JF, et al. Development of clinical pharmacy key performance indicators for hospital pharmacists using a modified Delphi approach. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(6):656–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028015577445.

Mullen PM. Delphi: myths and reality. J Health Organ Manag. 2003;17(1):37–52.

Christie CA, Barela E. The Delphi technique as a method for increasing inclusion in the evaluation process. Can J Program Eval. 2005;20(1):105–22.

Giannarou L, Zervas E. Using Delphi technique to build consensus in practice. Int J Bus Sci Appl Manag. 2014;9(2):66–82.

Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(1):205–12.

Krzyzaniak N, Bajorek B. A global perspective of the roles of the pharmacist in the NICU. Int J Pharm Pract. 2017;25(2):107–20.

World Health Organization. Health Systems—Equity. 2017. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/equity/en/. Accessed 02 Oct 2017.

Smoliński D. Farmacja szpitalna wychodzi z jaskini. RynekAptek. 2016. http://www.rynekaptek.pl/wywiad/farmacja-szpitalna-wychodzi-z-jaskini,16169_2.html. Accessed 02 Oct 2017.

Folli HL, Poole RL, Benitz WE, Russo JC. Medication error prevention by clinical pharmacists in two children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 1987;79(5):718–22.

Joint FIP/WHO guidelines on good pharmacy practice: standards for quality of pharmacy service. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011 Contract No.: 961.

Engels Y, Campbell S, Dautzenberg M, van den Hombergh P, Brinkmann H, Szécsényi J, et al. Developing a framework of, and quality indicators for, general practice management in Europe. Fam Pract. 2005;22(2):215–22.

Department of Health and Human Services, Defining Levels of Care for Victorian Newborn Services, Melbourne; Victorian Government; 2015. Available from: www.health.vic.gov.au/maternitycare. Accessed 20 Nov 2017.

NICE. Specialist neonatal care quality standard. skilled and multidisciplinary staff. Manchester: NICE; 2010.

BAPM. Service standards for hospitals providing neonatal care. Pharmacy. London: BAPM; 2010.

Roughead L, Semple S, Rosenfeld E. Literature review: medication safety in Australia. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2013.

Medication Safety in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Position Statement#3060 National Association of Neonatal Nurses, Chicago. 2014. http://nann.org/uploads/About/PositionPDFS/1.4.7_Medication Safety in the NICU.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2016.

Mikeal RL, Brown TR, Lazarus HL, Vinson MC. Quality of pharmaceutical care in hospitals. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1975;32(6):567–74.

WHO. Making pregnancy safer; assessment tool for the quality of hospital care for mothers and newborn babies. Advanced newborn care (for intensive care units). Copenhagen: WHO; 2009.

Clinical Pharmacist Intensive Care (PCICU, PICU, ED and NICU)—Pharmacy. Sidra Medical and Research Center. 2015. http://www.bayt.com/en/job/clinical-pharmacist-intensive-care-pcicu-picu-ed-and-nicu-pharmacy-in-qatar-50043520/. Accessed 04 Mar 2015.

Lucas AJ. Improving medication safety in a neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(1):33–7.

Simons SL. Designing medication safety in the NICU. Neonatal Netw. 2007;26(6):407–8.

Position Description: NICU Clinical Pharmacist Specialist. University of Kentucky Hospital 2009. http://www.hosp.uky.edu/pharmacy/departpolicy/PH14-45.pdf. 04 Mar 2007.

Cousins D KN, Walser S,. Pharmaceutical care: policies and practices for a safer, more responsible and cost effective health system. Strasbourg: Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare of the Council of Europe, 2012.

Kunac DL, Reith DM. Identification of priorities for medication safety in neonatal intensive care. Drug Saf. 2005;28(3):251–61.

Chedoe I, Molendijk HA, Dittrich ST, Jansman FG, Harting JW, Brouwers JR, et al. Incidence and nature of medication errors in neonatal intensive care with strategies to improve safety. Drug Saf. 2007;30(6):503–13.

Ng J, Harrison J. Key performance indicators for clinical pharmacy services in New Zealand public hospitals: stakeholder perspectives. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2010;1(2):75–84.

Patel SJ, Saiman L. Principles and strategies of antimicrobial stewardship in the neonatal intensive care unit. Sem Perinatol. 2012;36(6):431–6.

Sharek PJ, Powers R, Koehn A, Anand KJ. Evaluation and development of potentially better practices to improve pain management of neonates. Pediatrics. 2006;118(Supplement 2):S78–86.

Chawla D, Suresh GK. Quality improvement in neonatal care—a new paradigm for developing countries. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81(12):1367–72.

Elverson CA, Samra HA. Overview of structure, process, and outcome indicators of quality in neonatal care. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2012;12(3):154–61.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all of the experts in Poland who participated in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

None

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krzyżaniak, N., Pawłowska, I. & Bajorek, B. Quality pharmacy services and key performance indicators in Polish NICUs: a Delphi approach. Int J Clin Pharm 40, 533–542 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0623-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0623-y